Abstract

Introduction

Physical activity (PA) is important in promoting health, as well as in the treatment and prevention of diseases. However, insufficient PA is still a global health problem and it is also a problem in medical schools. PA training in medical curricula is still sparse or non-existent. There is a need for a comprehensive understanding of the extent of PA in medical schools through several indicators, including people, places and policies. This study includes a survey of the PA prevalence in a medical school and development of a tool, the Medical School Physical Activity Report Card (MSPARC), which will contain concise and understandable infographics and information for exploring, monitoring and reporting information relating to PA prevalence.

Methods and analysis

This mixed methods study will run from January to September 2017. We will involve the School of Medicine, Walailak University, Thailand, and its medical students (n=285). Data collection will consist of both primary and secondary data, divided into four parts: general information, people, places and policies. We will investigate the PA metrics about (1) people: the prevalence of PA and sedentary behaviours; (2) place: the quality and accessibility of walkable neighbourhoods, bicycle facilities and recreational areas; and (3) policy: PA promotion programmes for medical students, education metrics and investments related to PA. The MSPARC will be developed using simple symbols, infographics and short texts to evaluate the PA metrics of the medical school.

Ethics and dissemination

This study has been approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Walailak University (protocol number: WUEC-16-005-01). Findings will be published in peer-reviewed journals and presented at national or international conferences. The MSPARC and full report will be disseminated to relevant stakeholders, policymakers, staff and clients.

Keywords: Medical school, medical students, physical activity, policy, report card

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The mixed methods design of the study will include comprehensive metrics about physical activity (PA) in a medical school.

The data analysed from this study will be presented as an innovative tool, the Medical School Physical Activity Report Card (MSPARC), for exploring, monitoring and reporting on PA prevalence.

The MSPARC will provide concise and understandable infographics and information on PA at the medical school. Users can read the results at a glance.

The study is limited by its cross-sectional design presenting data from only one medical school. However, the methodology can be adopted for subsequent surveys and for other medical schools. The data collection can be adjusted for the conditions present at each medical school.

Introduction

Physical inactivity is a global health challenge. The estimated prevalence of physical inactivity is 23.3% among adults, 76.3% in adolescents, 78.4% for boys and 84.4% for girls.1 The pandemic of physical inactivity leads to increased mortality and morbidity, as well as increased economic costs.2 Globally, physical inactivity leads to about 1.6 million deaths a year, 15% of the burden of disease from colorectal cancer, 11% of ischaemic stroke, 9% of ischaemic heart disease and 7% of diabetes mellitus.3 The economic cost of physical inactivity was estimated to be $53.8 billion in 2013.2 The WHO set a goal of reducing physical inactivity by 10% by 2025.4 In response to this, global recommendations on physical activity (PA) for health were launched in 2010.5 Reducing physical inactivity or increasing PA requires understanding of multiple factors, including individual characteristics, environmental resources and public policies.6 7 It also entails a multisector, multidisciplinary public health response.8

In Thailand, about 30% of adults are physically inactive, and this leads to about 5.1% of the mortality nationally.9 Reducing the high rates of physical inactivity in the adult population will be a challenging task. In 2015 and 2016, the first national conference on health and PA, as well as an international conference, were held in Thailand. The slogan at the national conference was ‘Active Living for All’ and was adopted to encourage active people, places and policies.10 11 Subsequently, PA campaigns have been widely promoted. A nationwide PA campaign was announced by the Prime Minister, and all government agencies were to arrange exercise sessions every Wednesday afternoon from 15:00 to 16:30.12 Regular monitoring and reporting on the progress being made to increase PA were instituted as a sustainable development goal.13

Thus, a national policy for promoting PA and reducing physical inactivity emerged from these efforts, with a focus on the healthcare system and medical schools. Nevertheless, physical inactivity still occurs commonly among medical students, with about half (50.5%) of them in Southern Thailand not being physically active.14 This is problematic because the evidence shows a strong association between the personal PA behaviours of medical students and their PA counselling attitudes and practices.15 16 However, the education provided in medical schools to promote PA is either sparse or non-existent.17 18 This issue is an individual concern as well as a substantial issue for provision of an appropriate medical curriculum, given the ongoing gap in the understanding of the role of PA in health maintenance and its determinants in medical schools.

The approaches that have been used to increase PA in different populations include comprehensive exploration and monitoring. The Global Observatory for Physical Activity launched PA report cards (‘country cards’) as a single slide infographic tool for presenting the information on country-specific PA profiles for surveillance of PA prevalence and relevant metrics.19–21 The Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth, PA surveillance among children, has been released annually since 2005 to assess PA.22 23 The evidence suggests that PA report cards can ‘get people moving’.23 This approach might be beneficial for medical schools. Therefore, a specific PA report card designed for medical students might be an effective tool for exploring, monitoring and reporting the prevalence of PA in a particular cohort at one or more medical schools.

We still do not have a study protocol to explore the PA prevalence in medical schools. Therefore, our research team will focus on exploring relevant metrics for PA, including (1) the extent of PA and sedentary behaviours, (2) the quality and accessibility of PA-related environments, (3) any policies relating to PA in medical schools, and (4) developing a tool for exploring, monitoring and reporting the information relating to PA prevalence. This paper describes the study design and the development of the Medical School Physical Activity Report Card (MSPARC).

Aims and objectives

Primary aims:

explore the PA metrics of a medical school, including people, places and policies

develop the MSPARC for monitoring and reporting PA prevalence to clients (medical students), staff, policymakers and stakeholders.

The secondary aim was to develop the MSPARC protocol for further surveillance and for additional medical school settings.

Methods and analysis

Study design

A mixed methods study will be conducted, and will consist of both quantitative and qualitative approaches. Quantitatively, a cross-sectional observational study will be implemented to survey the relevant outcomes, including the prevalence of PA, the prevalence of sedentary behaviours, and the quality and accessibility of active environments. Qualitatively, a case study will focus on an in-depth description to develop a detailed analysis of the medical school policies.24 The study will be carried out over a 9-month period (from January to September 2017).

Setting and participants

The study will involve the medical students at three campuses of the School of Medicine, Walailak University, Thailand (in Nakhon Si Thammarat main campus, Trang Hospital and Vachira Phuket Hospital). All students are enrolled in preclinical years (years 1–3) study at the main campus. The rest of the medical students (clinical years, years 4–6) receive clinical training and hospital attachments at Trang Hospital and Vachira Phuket Hospital. The total number of medical students is 285, with 46–48 students in each class.

Data collection

Data collection will consist of both primary and secondary data, divided into four parts: general information, people, places and policies.

General information

The information will include the land area of the medical school (for the main campus), number of students and annual tuition fees. All this information will be collected from recent university and/or faculty documents.

People

The secondary data on the participation of medical students in PA, using the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ)—including activity that occurs during work, travel and recreation25—will be derived from the previous survey in 2016.14 PA in this context is sufficient behaviours or the WHO recommended levels, which include any activity that equals (1) 150 min of moderate-intensity exercise throughout the week, (2) 75 min of vigorous-intensity exercise throughout the week or (3) an equivalent combination of moderate-intensity and vigorous-intensity PA.5 We will focus on the PA prevalence of the entire student population and the prevalence by sex and seniority level (preclinical and clinical levels).

Sedentary time, collected by using the GPAQ, refers to time spent sitting during waking hours.25 We define sedentary behaviour using the cut-off of ≥8 hours per day of sedentary time.26 27

Place

We will assess the places related to active transportation and recreational PA in the main campus. Active transportation refers to ‘walking and cycling for transportation’, ‘non-motorised transport’ and ‘human powered transport’.28 Recreational PA means a PA that people engage in during their free time, that people enjoy and that people recognise as having socially redeeming value.29 Both active transportation and recreational activities are associated with natural and built environments.28 30–32

The data on PA-related places, including walkable neighbourhoods, bicycle facilities and recreational environments, will be collected from the preclinical students (n=144) by using a self-administered questionnaire developed by the research team. Box 1 shows the questions to survey places for PA.

Box 1. Questions to survey places for physical activity.

1. Usage: Do you use walkable neighbourhoods* (or bicycle facilities or recreational areas)?

□ Yes (go to item 1.1)

□ No (go to item 1.2)

1.1 How often do you use walkable neighbourhoods* (or bicycle facilities or recreational areas)?

□ Sometimes (1–2 days/week)

□ Often (3–4 days/week)

□ Always (5–7 days/week)

1.2 Why do you not use walkable neighbourhoods* (or bicycle facilities or recreational areas)?

□ Not interested/dissatisfied

□ Unavailable/inconvenient

□ Other reason (please specify)

2. Quality: How do you rate the quality of walkable neighbourhoods* (or bicycle facilities or recreational areas)?

An 11-point scale, with end-points at 0 (least) and 10 (most) will be provided.

3. Accessibility: How do you rate the accessibility of walkable neighbourhoods* (or bicycle facilities or recreational areas)?

An 11-point scale, with end-points at 0 (least) and 10 (most) will be provided.

*Walkable neighbourhoods or bicycle facilities or recreational areas.

Policy

We will collect the data on PA promotion programmes for medical students from the School of Medicine annual plans and reports. The data will include the number and name of programmes or projects related to PA promotion for medical students. The investment related to PA (amount of expense) will be collected.

As part of the Thai national medical competencies issued by the Medical Council of Thailand, medical students have to learn about approaches to health promotion, including exercise.33 The competencies do not specify particular aspects of PA education and training. The school curriculum will be reviewed to determine metrics regarding the following topics: (1) basic knowledge of PA—basic science of PA; (2) PA and public health—PA guidelines and PA promotion in public health; and (3) PA counselling—tailored PA counselling for healthy people and patients.

Data analysis

People

We will reanalyse the data from the previous survey.14 The prevalence of PA will be calculated by dividing the number of participants who met the recommended PA levels by the total number of participants. For each sex, the prevalence will be calculated by dividing the number of a particular sex who met the recommended PA levels with the total number of the same sex. The prevalence of PA for preclinical and clinical students will be classified.

The prevalence of sedentary behaviours will be calculated by dividing the number of participants who engage in ≥8 hours/day of sedentary time with the total number of participants. The prevalence of sedentary behaviours for each sex, and the prevalence of sedentary behaviours for preclinical and clinical students will be calculated.

Place

We will use descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages, describing the usage of walkable neighbourhoods, bicycle facilities and recreational areas. The quality and accessibility of walkable neighbourhoods, bicycle facilities and recreational areas will be calculated from the self-rating scales as mean scores to generate the fundamental and comparable data among each place.

Policy

Two investigators will independently review the relevant documents to identify PA promotion programmes for medical students. Two investigators will analyse the education metrics from the school curriculum for lectures, active learning sessions or clinical teaching topics about basic knowledge of PA, the relationship of PA and public health, and PA counselling. Any differences in the analyses will be resolved through consensus. The analysis will be confirmed by the research team members.

For the investment related to PA, we will calculate (1) the annual investment in PA programmes, (2) per capita investment (dividing the annual investment with the total number of medical students) and (3) ratio of per capita investment to annual tuition fee (dividing the per capita investment by the annual tuition fee).

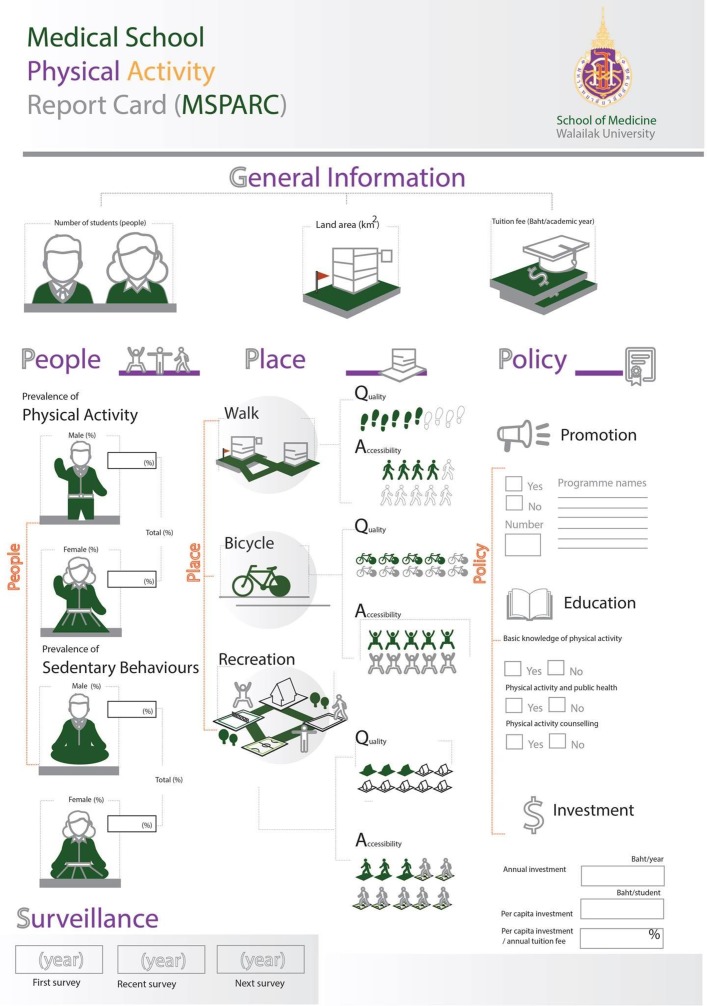

Development of the MSPARC

The indicators of the MSPARC will consist of five parts: general information, people, places, policies and surveillance (table 1). We will design simple and concise report cards (figure 1) in both Thai and English versions using uncomplicated symbols, infographics and short texts.

Table 1.

Data indicators of the Medical School Physical Activity Report Card

| General information | Land area (km2) Number of students Tuition fee (Baht/academic year) |

| People | Prevalence of physical activity

|

| Place | Walkable neighbourhoods

|

| Policy | Physical activity promotion programmes for medical students

|

| Surveillance | First survey (year) Recent survey (year) Next survey (year) |

Figure 1.

Example of the Medical School Physical Activity Report Card.

Ethics and dissemination

This study has been approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Walailak University (protocol number: WUEC-16-005-01) and the study will comply with the Declaration of Helsinki. Participation will be entirely voluntary, and medical students are free to refuse to become subjects in the study. This will not result in any penalty. Information about the research will be provided and the informed consent will be taken by asking the participants to indicate their agreement to participate by written informed consent forms. The participants’ information and responses will be strictly confidential and we will protect the participants’ anonymity.

The MSPARC will be presented to the faculty committee via a staff meeting. We will provide the visualised report card at the main office of School of Medicine. Medical students will be informed via the faculty website and social media. The final report and results will be forwarded to the grant funder (Walailak University), key stakeholders and policymakers of the university. The findings and tool (MSPARC) of the study will be disseminated to scholars and researchers through peer-reviewed journals as well as national and international conferences.

Discussion

This study will analyse the prevalence of regular PA in students at a Thai medical school. The results will be presented via the MSPARC, which provides concise data. It may help to communicate scientific and public health data at a glance. Information on the prevalence of PA and sedentary behaviours will be the initial information for defining future goals to improve student health. The quality and accessibility of walkable neighbourhoods, bicycle facilities and recreational areas will help the medical school administration understand the underlying limitations of PA-related environments. This will lead to the in-depth exploration of a particular problem. According to the policy, the data about PA promotion programmes will show the current activities and concerns about medical students’ health. Education metrics will reflect the comprehensiveness of the school curriculum regarding knowledge and practice, as well as the need for additional teaching. The information on investment related to PA will indicate the adequacy of the budget for PA promotion. Lastly, the surveillance information will collect the first, recent and future surveys in the medical school. These could be the milestones for evaluating and monitoring PA prevalence in the medical school.

A key limitation is that this cross-sectional study will be initially conducted in only one medical school. However, this protocol and the MSPARC can be adopted for future surveys and extended to other medical schools. For example, other medical schools can objectively measure PA and sedentary behaviours using pedometers or accelerometers instead of using the GPAQ. The MSPARC, which is based on the PA metrics, will enable comparison and evaluation among medical schools. Nevertheless, there is a need to evaluate the effectiveness and feasibility of the MSPARC. An implementation study will be necessary prior to future surveys. On a larger scale, regional or national concerns can help develop a strategy to strengthen collaboration among medical schools or promote PA in their own settings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Steve Melville for English language editing.

Footnotes

Contributors: AW and ST initiated the idea for the project and developed the study design. SV, US and WA provided advice for the study design. PP was responsible for supervision of project. AW wrote early drafts of the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by Walailak University grant number WUDPL60001.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Human Research Ethics Committee Walailak University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Sallis JF, Bull F, Guthold R, et al. Progress in physical activity over the Olympic quadrennium. Lancet 2016;388:1325–36. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30581-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ding D, Lawson KD, Kolbe-Alexander TL, et al. The economic burden of physical inactivity: a global analysis of major non-communicable diseases. Lancet 2016;388:1311–24. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30383-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. GBD. Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016;388:1659–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization. Physical activity: World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs385/en/ (accessed 25 Jan 2017).

- 5. World Health Organization. Global recommendations on physical activity for health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bauman AE, Reis RS, Sallis JF, et al. Correlates of physical activity: why are some people physically active and others not? Lancet 2012;380:258–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60735-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, et al. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q 1988;15:351–77. 10.1177/109019818801500401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reis RS, Salvo D, Ogilvie D, et al. Scaling up physical activity interventions worldwide: stepping up to larger and smarter approaches to get people moving. Lancet 2016;388:1337–48. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30728-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Global Observatory for Physical Activity. Physical activity country card. Thailand: Global Observatory for Physical Activity; http://www.globalphysicalactivityobservatory.com/card/?country=TH (accessed 25 Jan 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thai Health Promotion Foundation. Abstract book 1st National Conference on Physical Activity. Bangkok, Thailand: Thai Health Promotion Foundation, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11. International Society for Physical Activity and Health. The 6th ISPAH Congress: International Society for Physical Activity and Health. http://www.ispah.org/congress/ (accessed 25 Jan 2017).

- 12. Bangkok Post. Civil servants to exercise every Wednesday: Bangkok Post. http://m.bangkokpost.com/news/general/1141689/civil-servants-to-exercise-every-wednesday (accessed 25 Jan 2017).

- 13. International Society for Physical Activity and Health. The Bangkok Declaration on Physical Activity for Global Health and Sustainable development: International Society for Physical Activity and Health. http://www.ispah.org/resources (accessed 25 Jan 2017).

- 14. Wattanapisit A, Fungthongcharoen K, Saengow U, et al. Physical activity among medical students in Southern Thailand: a mixed methods study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e013479 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lobelo F, Duperly J, Frank E. Physical activity habits of doctors and medical students influence their counselling practices. Br J Sports Med 2009;43:89–92. 10.1136/bjsm.2008.055426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stanford FC, Durkin MW, Stallworth JR, et al. Factors that influence physicians’ and medical students’ confidence in counseling patients about physical activity. J Prim Prev 2014;35:193–201. 10.1007/s10935-014-0345-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stoutenberg M, Stasi S, Stamatakis E, et al. Physical activity training in US medical schools: Preparing future physicians to engage in primary prevention. Phys Sportsmed 2015;43:388–94. 10.1080/00913847.2015.1084868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Weiler R, Chew S, Coombs N, et al. Physical activity education in the undergraduate curricula of all UK medical schools: are tomorrow’s doctors equipped to follow clinical guidelines? Br J Sports Med 2012;46:1024–6. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Global Observatory for Physical Activity. Project mission and methods: Global Observatory for Physical Activity. http://www.globalphysicalactivityobservatory.com/project-description/ (accessed 30 Jan 2017).

- 20. Hallal P, Ramirez A. The Lancet Physical Activity Observatory: monitoring a 21st century pandemic. Res Exerc Epidemiol 2015;17:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tremblay MS, Gonzalez SA, Katzmarzyk PT, et al. Physical activity report cards: Active Healthy Kids Global Alliance and The Lancet Physical Activity Observatory. J Phys Act Health 2015;12:297–8. 10.1123/jpah.2015-0184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Barnes JD, Cameron C, Carson V, et al. Results From Canada’s 2016 ParticipACTION Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth. J Phys Act Health 2016;13:S110–16. 10.1123/jpah.2016-0300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tremblay MS, Barnes JD, Cowie Bonne J. Impact of the Active Healthy Kids Canada report card: a 10-year analysis. J Phys Act Health 2014;11 Suppl 1:S3–20. 10.1123/jpah.2014-0167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. 3 ed. Los Angeles, United States of America: SAGE, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25. World Health Organization. Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ). Analysis Guide: World Health Organization; http://www.who.int/chp/steps/resources/GPAQ_Analysis_Guide.pdf (accessed 30 Jan 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 26. van der Ploeg HP, Chey T, Korda RJ, et al. Sitting time and all-cause mortality risk in 222 497 Australian adults. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:494–500. 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.2174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Win AM, Yen LW, Tan KH, et al. Patterns of physical activity and sedentary behavior in a representative sample of a multi-ethnic South-East Asian population: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2015;15:318 10.1186/s12889-015-1668-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sallis JF, Frank LD, Saelens BE, et al. Active transportation and physical activity: opportunities for collaboration on transportation and public health research. Transp Res Part A: Policy Pract 2004;38:249–68. 10.1016/j.tra.2003.11.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hurd AR, Anderson DM. The park and recreation professional’s handbook. Illinois, United States of Ametica: Human Kinetics, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sundquist K, Eriksson U, Kawakami N, et al. Neighborhood walkability, physical activity, and walking behavior: the Swedish Neighborhood and Physical Activity (SNAP) study. Soc Sci Med 2011;72:1266–73. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wei Y, Xiao W, Wen M, et al. Walkability, Land Use and Physical Activity. Sustainability 2016;8:65 10.3390/su8010065 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. White MP, Elliott LR, Taylor T, et al. Recreational physical activity in natural environments and implications for health: A population based cross-sectional study in England. Prev Med 2016;91:383–8. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Medical Council of Thailand. Medical Competency Assessment Criteria for National License 2012. Bangkok, Thailand: Medical Council of Thailand, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.