Abstract

Objectives

Social activities such as ‘eating-with-others’ can positively affect the ageing process. We investigated the gender-specific association between eating arrangements and risk of all-cause mortality among free-living older adults.

Setting

A representative sample from the Elderly Nutrition and Health Survey in Taiwan during 1999–2000.

Participants

Some 1894 participants (955 men and 939 women) who aged ≥65 and completed eating arrangement question as well as confirmed survivorship information.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Eating arrangements, health condition and 24-hour dietary recall information were collected at baseline. We classified eating arrangements as the daily frequency of eating-with-others (0–3). Survivorship was determined by the National Death Registry until the end of 2008. Cox proportional-hazards regression was used to assess the association between eating-with-others and mortality risk.

Results

Overall, 63.1% of men and 56.4% of women ate with others three times a day. Both men and women who ate with others were more likely to have higher meat and vegetable intakes and greater dietary quality than those who ate alone. The HRs (95% CI) for all-cause mortality when eating-with-others two and three times per day were 0.42 (0.28 to 0.61), 0.67 (0.52 to 0.88) in men and 0.68 (0.42 to 1.11), 0.86 (0.64 to 1.16) in women, compared with those who ate alone. Multivariable HRs (95% CI) adjusted for sociodemographic, nutritional and ‘activities of daily living’ covariates were 0.43 (0.25 to 0.73), 0.63 (0.41 to 0.98) in men and 0.68 (0.35 to 1.30), 0.69 (0.39 to 1.21) in women. With further adjustment for financial status, HR was reduced by 54% in men who ate with others two times a day. Pathway analysis shows this to be dependent on improved dietary quality by eating-with-others.

Conclusions

Eating-with-others is an independent survival factor in older men. Providing a social environment which encourages eating-with-others may benefit survival of older people, especially for men.

Keywords: elderly, diet, mortality, social activities

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Use of a representative free-living Taiwanese cohort with 10 years follow-up for survival.

Study design provided an understanding of eating arrangements for older adults in a community setting.

A comprehensive assessment of the gender-specific associations between eating-with-others and mortality for older adults.

The frequency but not duration of time spent eating alone or eating-with-others was considered.

Participants were mainly of Chinese ethnicity from Taiwan so that the generalisability of findings may be limited.

Introduction

Social engagement, such as interpersonal relations (eg, contact and transactions with friends), exchange of information and receiving and providing emotional support, is a key component of healthy ageing, besides avoiding disease and maintaining physical and cognitive functions.1 However, opportunities to interact are frequently reduced after retirement because of factors such as loss of physical capacity, loss of mobility and solitary living.

The word ‘Meal’ means the event of eating and what is eaten. For this reason, social interaction is considered one of the criteria for a meal.2 Numerous countries offer nutritional programmes, such as congregate meals or meals-on-wheels programmes, to encourage eating in a social setting.3 The inverse correlation between eating-with-others and risk of depression has been studied extensively.4–7 Additionally, eating alone can be analysed as a separate risk factor from living alone with regard to depression or depressive symptoms.5 6 Eating-with-others can potentially improve dietary quality, variety and energy intake through social facilitation.8 9 Depression and poor dietary quality increase the risk of chronic disease and mortality in older adults.10 11 Solitary eating has been associated with a higher risk of mortality among small cohorts of elders in Botswana and the USA.12 13 But, it is unclear whether the daily frequency of eating-with-others is associated with survivorship.

Gender is also a factor in the quality of older people’s lives; for example, women frequently exhibit more health-seeking behaviour.14 15 Yet men face higher risks of depression after widowhood than do women.16 Exploring the gender-specific associations between solitary eating and mortality among older adults is potentially of public health value.

Providing simple, achievable steps for healthy ageing can prolong life, maintain quality of life over an extended duration and limit physical deterioration, all of which are beneficial to public health. The purpose of this study was, therefore, to evaluate whether the daily frequency of eating-with-others is associated with all-cause mortality in a representative, free-living, Taiwanese cohort of older men and women.

Subjects and methods

Participants

Participants aged 65 and over were recruited from the elderly Nutrition and Health Survey in Taiwan (NAHSIT Elderly) during 1999–2000. The details of the survey design and sampling method have been published elsewhere.17 In total, 1937 older people completed face-to-face interviews with trained interviewers. We excluded 40 participants with incorrect identification or incorrect identity numbers and those who did not provide relevant or required information. After which 1894 participants (955 men and 939 women) remained in the study. Trained interviewers collected data on sociodemographics, dietary habits and intake, and disease history. All participants signed informed consent forms prior to being interviewed. This project was approved by the ethics committees of the National Health Research Institute and Academia Sinica, Taiwan.

Eating arrangement

Eating arrangements were assessed by asking participants whether they usually ate breakfast, lunch and dinner with others. Their responses were recorded as one of the following four options: eat alone, eat with spouse, eat with children or relative(s) and eat with friend(s) or neighbour(s). We then classified the eating arrangements as eating-with-others 0 (eat alone), 1, 2, 3 times a day.18 Information was also obtained about the person responsible for meal preparation.

Dietary assessment

Information on frequency of dietary intake was collected using a validated Simplified Food Frequency Questionnaire.19 Dietary quality and nutritional intake were measured through 1-day 24-hour dietary recall. The dietary quality was evaluated using the Dietary Diversity Score (DDS), which is based on the consumption of a half serving of the following six food groups daily: grains; meat, fish or eggs; dairy; vegetables; fruits and oil or fat. The DDS ranges from 0 to 6, with a higher score representing higher dietary quality. The method of nutrient intake calculation is described elsewhere.10

Other variables

Participants were also asked how frequently they cooked or aided with cooking (excluding ready-to-eat meals), and their responses were recorded as never, sometimes, often or usually. Participants were then asked how many people they lived with. The response ‘0’ was defined as living alone.

Health-related quality of life was measured by a 36-item Short Form (SF-36) in a validated traditional Chinese version. A total of eight dimensions of health were included, such as physical functioning, role limitations due to physical problems, mental health, role limitations due to emotional problems, social function, bodily pain, vitality and general health. The score was calculated by the norm-based scoring system (μ=50, σ=10) and standardised. Higher scores indicated a better quality of life.20

Disability was evaluated by activities of daily living (ADL) which included nine questions about self-care task difficulty in an older adult’s daily life. We used bioelectrical impedance analysis to measure muscle mass. The Skeletal Muscle Mass Index was used to determine sarcopenia status, calculated with the following equation:21

(0.401×(height2/resistance)+(3.825×gender)–(0.071×age)+5.102)/height2 where height is measured in metres, resistance in Ohms and age in years; men=1 and women=0.

The Charlson Comorbidity Index was used to assess multimorbidity.22 Cognitive function was assessed by a validated Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire in Chinese which included 10 questions about orientation in time and place, personal history, long-term and short-term memory and calculation. More than or equal to three erroneous responses were regarded as cognitive impairment.23

Outcome ascertainment

National Death Registry data were obtained from Taiwan’s Ministry of Health and Welfare. We linked the NAHSIT dataset to the National Death Registry dataset using the participant ID to determine survival rates. Follow-up time was calculated from date of interview to date of death or until 31 December 2008.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables and continuous variables were presented as n (%) or mean±SEs. X2 and analysis of variance were used to determine the association between eating arrangements and baseline characteristics for categorical or continuous variables, respectively. The Cox proportional-hazards regression model was used to evaluate the association between daily frequency eating-with-others and risk of all-cause mortality. Since the interaction between eating arrangements and gender was significant (p=0.0093), we used gender-specific analyses. Additional factors were age, education level, marital status, region, living arrangement, body mass index (BMI), DDS, cooking frequency, appetite status, ADL and self-rate financial status. All data analyses were performed using SAS V.9.2 and SUDAAN V.9.0 to adjust for the design effect of sampling.

To explore the pathways which might connect eating-with-others to survival, we have considered the intermediates of dietary quality (DDS), physical functioning, mental health and general health. The first linkage, using continuous variables, has been assessed by Pearson’s partial correlation coefficients. The second linkage to risk of mortality, as coefficients, has been assessed by the Aalen additive hazards model.24

Results

In total, 63.1% of men and 56.4% of women ate with others three times a day. For both genders, those who ate with others were more likely to be younger, married, better financial status, living with others and less cooking than were those who ate alone. Men who ate alone had significantly higher ADL (p=0.004) and cognitive impairment (p=0.005) than those who ate with others (table 1).

Table 1.

The baseline characteristics by daily frequency for eating-with-others

| Daily frequency for eating-with-others | ||||||||||||

| Variables | Men | Women | ||||||||||

| Total | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | p Value | Total | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | p Value | |

| n | 142 | 57 | 126 | 630 | 174 | 79 | 140 | 546 | ||||

| % | 14.3 | 6.96 | 15.6 | 63.1 | 17.8 | 10.2 | 15.7 | 56.4 | ||||

| Median of follow-up (years) | 8.17 | 8.28 | 8.76 | 8.67 | 8.55 | 8.89 | 8.75 | 8.74 | ||||

| Age at baseline (years) | 72.9±0.33 | 74.9±0.65 | 71.8±0.74 | 72.4±0.73 | 72.7±0.44 | 0.042 | 73.4±0.44 | 75.3±0.76 | 72.9±0.65 | 72.9±0.88 | 73.0±0.39 | 0.020 |

| Education | <0.0001 | 0.963 | ||||||||||

| Illiterate | 18.8 | 24.2 | 16.7 | 8.8 | 20.3 | 56.0 | 57.5 | 55.6 | 52.3 | 56.6 | ||

| Some up to primary school | 46.6 | 52.3 | 43.5 | 48.4 | 45.2 | 32.3 | 32.5 | 32.0 | 33.8 | 31.9 | ||

| High school and above | 34.7 | 23.5 | 39.9 | 42.8 | 34.5 | 11.7 | 10.0 | 12.4 | 13.8 | 11.5 | ||

| Marital status | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||

| Married | 78.6 | 36.1 | 48.2 | 75.0 | 92.5 | 49.48 | 15.5 | 19.6 | 37.8 | 68.8 | ||

| Bereaved | 14.3 | 37.8 | 38.8 | 17.5 | 5.43 | 48.12 | 80.6 | 71.1 | 60.7 | 30.3 | ||

| Others | 7.15 | 26.1 | 13.0 | 7.55 | 2.11 | 2.40 | 3.87 | 9.32 | 1.56 | 0.95 | ||

| Live alone | 13.7 | 60.4 | 0.00 | 9.67 | 1.47 | <0.0001 | 10.3 | 49.4 | 6.43 | 2.91 | 0.42 | <0.0001 |

| Whether enough money | 0.030 | 0.001 | ||||||||||

| More than enough | 78.4 | 71.8 | 79.9 | 85.8 | 77.8 | 75.0 | 64.1 | 63.1 | 78.3 | 79.5 | ||

| Just enough | 19.2 | 21.7 | 20.2 | 13.0 | 20.1 | 21.0 | 28.7 | 28.8 | 21.0 | 17.2 | ||

| Not enough | 2.46 | 6.52 | 0.00 | 1.26 | 2.14 | 4.01 | 7.23 | 8.13 | 0.70 | 3.25 | ||

| Smoker | 65.7 | 70.5 | 82.0 | 63.9 | 63.2 | 0.078 | 4.92 | 2.44 | 2.55 | 5.34 | 6.01 | 0.171 |

| Appetite status | 0.232 | 0.112 | ||||||||||

| Good | 38.5 | 33.0 | 45.0 | 36.6 | 39.4 | 30.4 | 24.9 | 42.9 | 31.7 | 29.5 | ||

| Fair | 55.5 | 62.5 | 41.5 | 59.4 | 54.5 | 59.4 | 57.2 | 48.8 | 61.5 | 61.4 | ||

| Poor | 6.07 | 4.54 | 13.5 | 4.09 | 6.08 | 10.2 | 17.9 | 8.34 | 6.87 | 9.14 | ||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.3±0.15 | 22.9±0.46 | 23.2±0.64 | 23.2±0.33 | 23.3±0.17 | 0.738 | 23.9±0.25 | 23.3±0.56 | 25.1±0.43 | 24.5±0.50 | 23.8±0.28 | 0.0002 |

| <18.5 | 7.07 | 11.2 | 10.4 | 7.53 | 5.66 | 7.01 | 8.07 | 0.00 | 3.83 | 8.72 | ||

| 18.5–23.9 | 52.5 | 54.1 | 53.4 | 50.6 | 52.6 | 44.0 | 51.0 | 39.6 | 40.9 | 43.6 | ||

| 24.0–26.9 | 28.0 | 19.0 | 19.9 | 34.0 | 29.2 | 27.8 | 24.7 | 34.1 | 25.3 | 28.1 | ||

| ≥27.0 | 12.5 | 15.7 | 16.3 | 7.91 | 12.6 | 21.3 | 16.3 | 26.3 | 30.0 | 19.6 | ||

| Physical activity (MET/day) | 0.173 | 0.017 | ||||||||||

| <1.5 | 51.6 | 45.3 | 44.0 | 51.2 | 54.0 | 61.1 | 60.5 | 51.0 | 52.9 | 65.4 | ||

| 1.5–2.9 | 11.3 | 14.3 | 17.9 | 14.2 | 9.17 | 11.8 | 14.3 | 6.16 | 14.0 | 11.4 | ||

| ≥3 | 37.1 | 40.4 | 38.1 | 34.7 | 36.8 | 27.1 | 25.2 | 42.8 | 33.1 | 23.2 | ||

| Shopping | 0.239 | 0.037 | ||||||||||

| <1/week | 43.8 | 34.2 | 44.5 | 45.9 | 45.5 | 54.9 | 65.3 | 46.6 | 50.9 | 54.3 | ||

| 1/week | 12.7 | 13.5 | 15.2 | 13.0 | 12.2 | 13.6 | 10.2 | 14.8 | 18.4 | 13.1 | ||

| 1–2/week | 23.3 | 24.7 | 21.0 | 19.6 | 24.2 | 19.8 | 14.9 | 24.7 | 22.0 | 19.8 | ||

| Everyday | 20.2 | 27.6 | 19.3 | 21.6 | 18.3 | 11.7 | 9.63 | 13.9 | 8.74 | 12.9 | ||

| Current cooking activity | <0.0001 | 0.004 | ||||||||||

| Never | 58.4 | 33.2 | 44.1 | 58.1 | 65.8 | 26.8 | 24.1 | 12.1 | 31.5 | 29.1 | ||

| Sometimes | 20.3 | 13.1 | 19.2 | 24.8 | 20.8 | 13.2 | 5.10 | 9.1 | 16.0 | 15.8 | ||

| Often | 6.83 | 6.63 | 11.4 | 9.63 | 5.66 | 10.5 | 6.94 | 20.0 | 12.6 | 9.23 | ||

| Usually | 14.5 | 47.0 | 25.2 | 7.46 | 7.69 | 49.5 | 63.9 | 58.8 | 39.9 | 45.9 | ||

| Activities of daily living | 0.33±0.05 | 0.52±0.18 | 0.19±0.15 | 0.07±0.05 | 0.36±0.07 | 0.004 | 0.57±0.08 | 1.18±0.34 | 0.27±0.13 | 0.28±0.17 | 0.50±0.10 | 0.088 |

| Skeletal Muscle Mass Index (kg/m2) | 12.3±0.12 | 12.0±0.27 | 12.2±0.29 | 12.0±0.20 | 12.5±0.13 | 0.149 | 9.28±0.12 | 9.14±0.22 | 9.52±0.20 | 9.32±0.17 | 9.29±0.15 | 0.213 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 4.71±0.20 | 5.20±0.48 | 4.22±0.39 | 4.85±0.61 | 4.62±0.20 | 0.365 | 4.77±0.21 | 5.06±0.51 | 4.74±0.59 | 4.21±0.29 | 4.84±0.24 | 0.142 |

| Self-perceived health status | 0.400 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||

| Excellent | 4.55 | 7.12 | 7.46 | 1.23 | 4.47 | 2.58 | 2.88 | 0 | 3.14 | 2.80 | ||

| Very good | 19.9 | 16.5 | 13.8 | 29.9 | 18.9 | 15.7 | 10.7 | 24.3 | 14.1 | 16.0 | ||

| Good | 21.4 | 25.8 | 19.0 | 17.3 | 21.8 | 16.1 | 11.8 | 9.85 | 17.7 | 18.2 | ||

| Fair | 41.1 | 38.2 | 40.3 | 40.7 | 41.9 | 48.3 | 47.9 | 56.7 | 50.4 | 46.2 | ||

| Poor | 13.1 | 12.4 | 19.5 | 10.9 | 13.1 | 17.4 | 26.7 | 9.25 | 14.7 | 16.8 | ||

| Cognitive impairment | 8.81 | 12.6 | 1.82 | 3.10 | 10.2 | 0.005 | 27.4 | 30.9 | 25.9 | 30.4 | 25.8 | 0.751 |

All data weighted for unequal probability of sampling design by SUDAAN. Categorical variables are presented as n (%), and continuous variables are presented as mean±SE.

ANOVA and χ2 were used for continuous and categorical variables to test difference between the groups by gender.

ANOVA, analysis of variance; MET, metabolic equivalent of task.

Table 2 presents the dietary quality and food intakes for daily frequency of eating-with-others by gender. Those who ate alone had a poor dietary quality (DDS ≤3), compared with those who ate with others three times daily. Men who ate alone ate less meat (1.02 vs 1.30 times/day) and vegetables (1.90 vs 2.47 times/day) than did those who ate with others three times a day (p<0.05). Women who ate with others three times a day tended to eat more meat (1.13 vs 0.81 times/day), seafood (0.99 vs 0.70 times/day), eggs (0.38 vs 0.23 times/day) and vegetable intake (2.52 vs 2.09 times/day) than did those who ate alone (p<0.05). Further, women who ate alone had lower fat (24.7 vs 28.9 g/1000 kcal/day) intakes, but higher carbohydrate (155 vs 144 g/1000 kcal/day) intakes compared with those who ate with others (p<0.05). Regarding meals, around 58%–60% of men and 68%–74% of women prepared meals by themselves when eating alone. Men were more likely to eat out when eating-with-others one time a day compared with women.

Table 2.

Food, nutrient intakes and daily frequency of eating-with-others by gender

| Daily frequency for eating-with-others | ||||||||||

| Men | Women | |||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | p Value | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | p Value | |

| Food preparation, % | ||||||||||

| Skipping meals | 11.2 | 16.5 | 5.75 | 2.96 | 0.008 | 6.54 | 8.45 | 4.76 | 4.27 | 0.370 |

| Who prepared breakfast? | <0.0001 | 0.003 | ||||||||

| Self | 57.6 | 45.7 | 37.0 | 12.7 | 74.0 | 76.2 | 61.3 | 57.2 | ||

| Others | 28.6 | 36.4 | 56.1 | 85.8 | 23.9 | 20.7 | 36.1 | 41.5 | ||

| Eating out | 13.8 | 17.9 | 6.96 | 1.52 | 2.14 | 3.12 | 2.62 | 1.35 | ||

| Who prepared lunch? | <0.0001 | 0.0001 | ||||||||

| Self | 59.0 | 40.8 | 11.3 | 9.07 | 68.1 | 74.2 | 48.0 | 53.1 | ||

| Others | 31.3 | 34.9 | 85.0 | 89.0 | 26.3 | 18.1 | 50.0 | 45.2 | ||

| Eating out | 9.72 | 24.3 | 3.66 | 1.90 | 5.59 | 7.73 | 1.96 | 1.63 | ||

| Who prepared dinner? | <0.0001 | 0.009 | ||||||||

| Self | 60.0 | 25.0 | 6.20 | 8.52 | 67.7 | 60.1 | 44.6 | 51.4 | ||

| Others | 32.9 | 74.0 | 92.1 | 90.7 | 30.2 | 39.9 | 55.4 | 48.1 | ||

| Eating out | 7.05 | 1.03 | 1.73 | 0.76 | 2.11 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.51 | ||

| If you need to prepare meals for yourself, who gets the food? | <0.0001 | 0.118 | ||||||||

| Never prepare | 6.21 | 15.8 | 9.38 | 9.32 | 8.37 | 1.67 | 5.24 | 6.60 | ||

| Self | 61.2 | 23.4 | 21.2 | 18.6 | 60.2 | 67.4 | 48.2 | 48.4 | ||

| Others | 32.6 | 60.8 | 69.5 | 72.1 | 31.4 | 31.0 | 46.6 | 45.0 | ||

| Dietary diversity score, mean±SE | 4.27±0.11 | 4.13±0.17 | 4.57±0.11 | 4.61±0.06 | 0.003 | 4.28±0.13 | 4.32±0.14 | 4.69±0.10 | 4.46±0.06 | 0.009 |

| ≤3 (%) | 24.1 | 22.1 | 12.2 | 12.1 | 0.010 | 30.2 | 20.7 | 8.05 | 17.5 | 0.001 |

| 4 (%) | 30.0 | 41.4 | 30.2 | 32.4 | 24.1 | 31.2 | 31.5 | 31.3 | ||

| 5 (%) | 35.4 | 28.4 | 39.6 | 35.8 | 25.1 | 31.7 | 42.8 | 34.8 | ||

| 6 (%) | 10.8 | 8.13 | 18.0 | 19.7 | 20.7 | 16.4 | 17.6 | 16.4 | ||

| Food intake other than cereal (times/day), mean±SE | ||||||||||

| Dairy | 0.57±0.07 | 0.40±0.09 | 0.65±0.08 | 0.62±0.05 | 0.116 | 0.80±0.08 | 0.89±0.14 | 0.74±0.09 | 0.72±0.05 | 0.480 |

| Meat | 1.02±0.09 | 1.98±0.08 | 1.59±0.19 | 1.30±0.07 | 0.001 | 0.81±0.15 | 0.86±0.16 | 1.20±0.16 | 1.13±0.08 | 0.017 |

| Seafood | 0.86±0.18 | 0.93±0.12 | 1.08±0.12 | 0.99±0.08 | 0.524 | 0.70±0.10 | 0.92±0.12 | 0.91±0.09 | 0.99±0.07 | 0.026 |

| Egg | 0.44±0.08 | 0.39±0.05 | 0.46±0.05 | 0.46±0.03 | 0.687 | 0.23±0.03 | 0.36±0.04 | 0.36±0.03 | 0.38±0.03 | 0.003 |

| Soy | 0.48±0.09 | 0.43±0.06 | 0.47±0.06 | 0.45±0.04 | 0.824 | 0.39±0.06 | 0.50±0.10 | 0.61±0.07 | 0.51±0.05 | 0.063 |

| Vegetable | 1.90±0.18 | 1.84±0.13 | 2.57±0.13 | 2.47±0.12 | 0.004 | 2.09±0.14 | 2.28±0.13 | 2.35±0.14 | 2.52±0.14 | 0.011 |

| Fruit | 0.99±0.11 | 0.93±0.13 | 1.21±0.09 | 1.19±0.04 | 0.073 | 0.91±0.10 | 0.90±0.07 | 1.21±0.10 | 1.07±0.06 | 0.058 |

| Total energy intake (kcal), mean±SE | 1833±100 | 1849±123 | 1871±118 | 1815±77.4 | 0.940 | 1327±92.6 | 1518±126 | 1500±58.7 | 1521±84.3 | 0.206 |

| Nutrient density (/1000 kcal), mean±SE | ||||||||||

| Carbohydrate (g) | 132±4.79 | 137±5.21 | 139±2.58 | 139±2.71 | 0.438 | 155±3.55 | 143±5.63 | 144±3.31 | 144±1.82 | 0.028 |

| Dietary fibre (g) | 11.2±0.79 | 11.7±0.87 | 12.4±0.75 | 11.7±0.45 | 0.653 | 15.5±2.05 | 14.1±1.44 | 14.0±1.02 | 12.7±0.57 | 0.416 |

| Fat (g) | 32.1±1.42 | 30.5±2.15 | 30.2±1.28 | 29.5±0.82 | 0.377 | 24.7±1.13 | 29.7±2.30 | 29.2±1.50 | 28.9±0.85 | 0.002 |

| Protein (g) | 41.9±1.80 | 43.3±2.52 | 41.5±1.34 | 43.2±1.16 | 0.690 | 41.6±1.77 | 42.1±2.06 | 42.8±1.32 | 41.8±1.27 | 0.923 |

| Vitamin B1 (mg) | 0.63±0.06 | 0.78±0.07 | 0.69±0.04 | 0.70±0.03 | 0.645 | 0.71±0.08 | 0.69±0.05 | 0.76±0.07 | 0.66±0.03 | 0.449 |

| Vitamin B2 (mg) | 0.84±0.06 | 0.88±0.12 | 0.78±0.06 | 0.81±0.04 | 0.801 | 1.02±0.07 | 1.11±0.14 | 1.05±0.09 | 0.85±0.04 | 0.107 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | 0.73±0.07 | 0.82±0.09 | 0.75±0.05 | 0.72±0.03 | 0.586 | 0.65±0.05 | 0.81±0.08 | 0.73±0.03 | 0.71±0.03 | 0.421 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 92.5±12.2 | 88.4±12.8 | 87.5±8.69 | 90.6±6.18 | 0.984 | 110±9.32 | 103±11.5 | 131±20.0 | 105±7.72 | 0.597 |

| Calcium (mg) | 382±26.2 | 338±41.7 | 336±21.0 | 365±16.3 | 0.353 | 536±43.0 | 455±42.4 | 483±41.7 | 432±19.8 | 0.166 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 139±7.34 | 141±12.1 | 143±6.63 | 145±3.84 | 0.907 | 167±9.06 | 157±7.87 | 159±9.59 | 147±4.55 | 0.142 |

All data weighted for unequal probability of sampling design by SUDAAN.

ANOVA and χ2 were used for continuous and categorical variables to test difference between the groups by gender.

ANOVA, analysis of variance.

Men who ate with others two times per day have significantly high physical functioning compared with other groups (p=0.044). For women, who ate with others one time per day have higher physical functioning (50.7 vs 45.2) and role limitations due to physical problem (51.4 vs 46.1) compared with those who ate alone (table 3).

Table 3.

Health-related quality of life (SF-36) according to daily frequency eating-with-others by gender

| Daily frequency eating-with-others | ||||||||||

| Men | Women | |||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | p Value | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | p Value | |

| General health | 52.8±1.18 | 52.0±1.49 | 52.9±1.10 | 51.5±0.50 | 0.538 | 47.1±0.99 | 48.6±1.23 | 49.7±1.24 | 49.0±0.84 | 0.211 |

| Mental health | 51.4±0.91 | 49.3±1.88 | 52.3±1.13 | 52.5±0.50 | 0.222 | 47.8±1.30 | 47.3±1.45 | 48.8±1.27 | 49.2±1.02 | 0.542 |

| Physical functioning | 51.1±1.16 | 50.4±1.26 | 53.3±0.68 | 51.5±0.65 | 0.044 | 45.2±0.96 | 50.7±0.97 | 48.2±1.03 | 47.0±0.64 | 0.002 |

| Body pain | 51.2±1.20 | 51.5±1.63 | 52.8±1.04 | 51.9±0.68 | 0.529 | 46.5±1.08 | 47.4±1.20 | 49.5±1.00 | 48.0±0.69 | 0.112 |

| Role limitations due to emotional problems | 50.0±1.19 | 47.7±1.69 | 51.5±0.93 | 51.2±0.63 | 0.160 | 47.5±1.16 | 50.8±1.51 | 49.6±1.13 | 49.3±0.86 | 0.354 |

| Role limitations due to physical problems | 50.2±1.36 | 49.5±1.31 | 52.1±1.01 | 51.4±0.67 | 0.254 | 46.1±1.03 | 51.4±1.28 | 48.7±1.55 | 49.7±0.87 | 0.005 |

| Social function | 50.0±1.22 | 49.4±1.71 | 51.9±0.99 | 50.9±0.67 | 0.262 | 48.2±1.17 | 48.6±1.31 | 50.0±1.31 | 49.0±0.71 | 0.698 |

| Vitality | 51.0±1.32 | 49.4±1.76 | 51.7±1.02 | 51.8±0.68 | 0.591 | 47.1±0.95 | 49.2±1.72 | 48.1±1.45 | 48.1±0.75 | 0.553 |

All data weighted for unequal probability of sampling design by SUDAAN.

ANOVA was used for continuous and categorical variables to test difference between the groups by gender.

ANOVA, analysis of variance; SF-36; Short Form 36.

Table 4 presents the association between daily frequency eating-with-others and risk of all-cause mortality by gender. In the crude model, the HRs (95% CI) of risk of all-cause mortality for who ate with others two or three times a day were 0.42 (0.28 to 0.61), 0.67 (0.52 to 0.88) in men and 0.68 (0.42 to 1.11), 0.86 (0.64 to 1.16) in women compared with those who ate alone, respectively. When adjusted for age, education, marital status, region, living arrangement, cooking, appetite status, ADL, DDS and BMI, the HRs (95% CI) were 0.43 (0.25 to 0.73), 0.63 (0.41 to 0.98) for men and 0.68 (0.35 to 1.30), 0.69 (0.39 to 1.21) for women who ate with others two or three times a day. With further adjustment for financial status, the risk of mortality is reduced by 54% (HR 0.46, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.77) and 34% (HR 0.66, 95% CI 0.43 to 1.02) for men who ate with others two or three times a day.

Table 4.

Gender-specific HRs (95% CI) of association between eating-with-others and risk of mortality in older adults

| Daily frequency of eating-with-others | ||||||||

| Men | Women | |||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Deceased/survival, n | 75/67 | 26/31 | 37/89 | 248/382 | 60/114 | 20/59 | 36/104 | 196/350 |

| Crude model | 1.00 | 0.90 (0.60 to 1.35) | 0.42*** (0.28 to 0.61) | 0.67** (0.52 to 0.88) | 1.00 | 0.53 (0.27 to 1.05) | 0.68 (0.42 to 1.11) | 0.86 (0.64 to 1.16) |

| Model 1 | 1.00 | 1.12 (0.71 to 1.78) | 0.48** (0.31 to 0.74) | 0.76 (0.57 to 1.03) | 1.00 | 0.54 (0.24 to 1.23) | 0.89 (0.53 to 1.49) | 1.07 (0.77 to 1.49) |

| Model 2† | 1.00 | 0.76 (0.37 to 1.56) | 0.43** (0.25 to 0.73) | 0.63* (0.41 to 0.98) | 1.00 | 0.56 (0.29 to 1.07) | 0.68 (0.35 to 1.30) | 0.69 (0.39 to 1.21) |

| Model 3† | 1.00 | 0.78 (0.39 to 1.55) | 0.46** (0.28 to 0.77) | 0.66 (0.43 to 1.02) | 1.00 | 0.54 (0.27 to 1.06) | 0.70 (0.36 to 1.36) | 0.72 (0.40 to 1.27) |

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

†Women were not adjusted for activities of daily living in the models since it is highly correlated with cooking frequency.

Data were weighted for unequal probability of sampling design by SUDAAN and estimated HR (95% CI) by using the Cox proportional-hazards model.

Model 1: adjusted for age.

Model 2: adjusted for age, education (illiterate, primary school, high school and above), region (Hakka, mountains, Eastern Taiwan, Penghu, Northern Taiwan 1–3, Central Taiwan 1–3, Southern Taiwan 1–3), live alone (live alone, live with others), cook frequency (never, sometimes, often, frequently), marital status (married, bereaved, other), appetite status (good, fair, poor), Dietary Diversity Score (≤3, 4, 5, 6), activities of daily living and body mass index (<18.5, 18.5–23.9, 24.0–26.9, ≥27 kg/m2).

Model 3: model 2 plus adjusted self-rate financial status (more than enough, just enough, not enough).

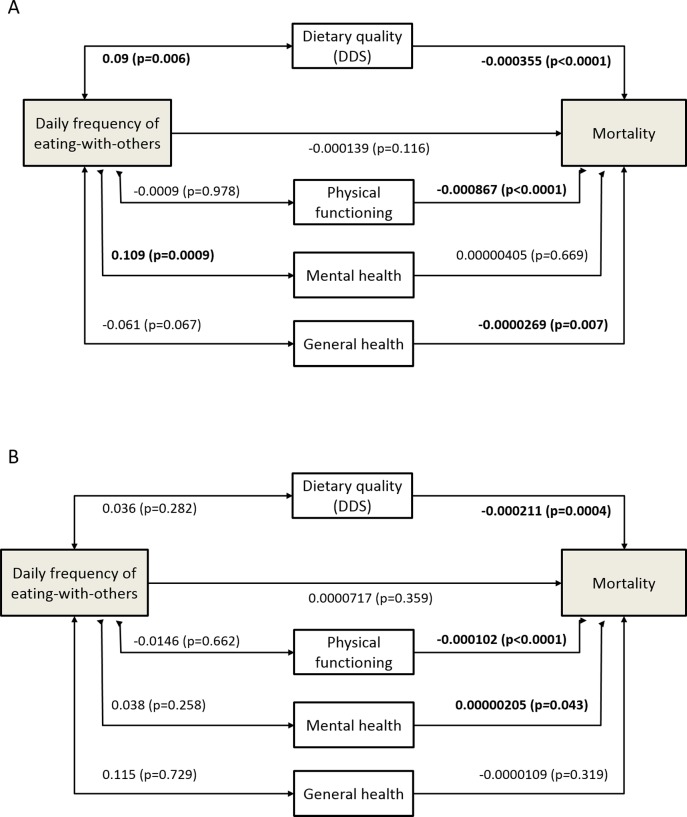

The pathway analyses are shown in figure 1. For men, there are significant positive associations between eating-with-others frequency and dietary quality (DDS) (p=0.006) as well as mental health (p=0.0009). In turn, better dietary quality (p<0.0001) is associated with less mortality risk, as are physical functioning (p<0.0001) and general health (p=0.007). For women, eating-with-others is not associated with any of dietary quality, physical functioning, mental health or general health; however, dietary quality (p=0.0004) and physical functioning (p<0.0001) are inversely associated with mortality risk, while mental health (p=0.043) is positively associated.

Figure 1.

Gender-specific pathway analysis for the associations of eating-with-others and all-cause mortality. All values are presented as β coefficients with their p values (p<0.05 are highlighted in bold). (A) men; (B) women. DDS, Dietary Diversity Score.

Discussion

This study explored the gender-specific associations between eating arrangement and risk of mortality by observing a population-representative older adult cohort with a 10-year follow-up in an Asian country. Eating-with-others was inversely associated with risk of mortality, more evident in men than in women.

Food intake when eating-with-others

Eating-with-others has numerous beneficial effects on health. A randomised controlled trial at a Dutch nursing home found that family-style meals that included the presence of others increased the energy intake and reduced the prevalence of malnutrition. Those who ate with others ate more than those who ate alone. Social eating may stimulate intake through extension of meal duration and improved ambiance.8 The presence of others in the household did not affect energy intake, but the presence of others during mealtime did, with an average of 114 calories more per meal than those who ate alone.25 Eating socially also improved dietary quality and diversity.7 9 However, the present study shows that after control for dietary quality in the model, eating-with-others and mortality remain associated. A possible reason for this is that solitary eating is often associated with depression,4–6 in turn associated with mortality. However, there may be value in solitude itself which would be an alternative interpretation of the difference we have found in mortality risk reduction between eating two times and three times a day with others by men.

Eating-with-others and mortality

Our findings are consistent with several studies from Western countries. The Nutrition Screening Initiative checklist, a tool for malnutrition screening and awareness in older adults in the USA, asks questions regarding solitary eating. A cohort study with 581 community-dwelling older adults, who ate more than 17 meals alone per week, exhibited a 2.07-fold higher risk of mortality (relative risk 2.07, 95% CI 1.49 to 2.86) over an 8- to 12-year period.13 Another study in Botswana found that older adults who ate alone had a higher risk of death (OR 6.7, 95% CI 2.2 to 20.0).12 But, gender effect was unknown in these studies.

Eating alone and gender

In the present study, men who ate with others had a lower risk of mortality than did those who ate alone, for several probable reasons. Men who ate with others had better dietary quality and a higher vegetable intake than those eating alone. We also found that men who ate alone were more likely to eat out, not prepare meals by themselves and frequently skip meals than did women. A Japanese cohort study discovered that men who ate alone were more likely to be underweight and skip meals and less likely to eat fruits and vegetables.9 Underweight older adults with poor dietary quality and low fruit and vegetable intakes have been associated with a higher risk of mortality.10 26 Furthermore, in our study, eating out is often associated with high-fat foods with poor quality. Men who were solitary eaters had low carbohydrate, protein, dietary fibre and other nutrient intakes, but a higher fat intake than those who ate with others, although the differences were non-significant.

Compared with Japan,9 in our study men have a higher rate of solitary eating, but women have a lower rate. Taiwanese men who eat alone are more likely to be unmarried or live separately from their spouse. We found that the eating companionship of men who ate with others was usually their spouse or children rather than friends or neighbours (data not shown). Davis et al found that dietary patterns of older men had stronger associations with living arrangements than did those of older women.27 Cooking itself is a physical activity and a cognitive function,28 and in Taiwanese culture women are more likely to prepare meals. Men eat out or buy ready-to-eat food more than they cook. In this study, men (47.0%) cooked less than did women (63.9%) when eating alone (table 1). Men who ate alone shopped more than did women who ate alone (27.6% vs 9.6%).

It is also possible that what has been observed as a link between eating-with-others by men and survival is part of a bigger picture of the role of marriage and men living with a partner in their health outcomes and survival. It is well documented that men who live with a female partner live longer than those who do not.29 30 This could be for any one or more of several reasons which include having a carer, companionship or sharing of duties. A correlation matrix (online supplementary table 1) shows that the greatest correlations with eating-with-others are for marital status (positive), living alone (negative) and cooking frequency (negative). In all three, the magnitude of the relationships is stronger for men. These covariates are included in our models. We have identified marital status and cooking as potential explanators for the difference in HRs between eating-with-others two times or three times a day by men.

bmjopen-2017-016575supp001.pdf (58.3KB, pdf)

Pathways from eating-with-others to survival

For men but not women, pathway analyses indicate that dietary quality, assessed as dietary diversity, provides a potential connection between the social aspect of eating-with-others and survival (figure 1). This underscores the likely basic importance of nutritional factors in life-long health, but draws attention to the social as well as the biomedical role of food in health. For men, on pathway analysis, eating-with-others is associated with better mental health. Since pathway analysis requires that all independent variables are continuous, this may have resulted in an absence of a significant direct association of eating-with-others with mortality due to its frequency not being linearly related to mortality; this contrasts with the survival analyses by Cox regression (table 4). In addition, by pathway analysis, each of physical functioning and general health are themselves important in the prediction of mortality risk in men. It remains conceivable that the dietary quality that men achieve, irrespective of eating-with-others, plays a role in each of physical functioning and general health, which is evident in this population.10 20

In the case of women, dietary quality directly and favourably predicts survival, but this connection is not found to be dependent on eating-with-others. Perhaps women can achieve the biomedical benefit of survival through diet without the need for its social function. In addition, women have a more favourable survival with better physical functioning. Somewhat surprisingly, better mental health is unfavourably associated with survival, although this is weakly significant. It is possible that confounders that have not been considered in this pathway analysis might account for this mental health association with mortality in older women. For example, in devoting themselves to the care of others or in dealing successfully with a relative socioeconomic disadvantage in widowhood, a sense of well-being may obtain, while health adversity supervenes.

Limitations

There are some limitations to this study. First, since the study participants were elderly, it can be expected that a change in their eating arrangements would take place through time as family and health circumstances change. Given that this is a single point survey (1999–2000), varied follow-up times may alter the findings. However, we have performed analyses with several follow-up times (<2, <4, <6 and ≥6 years) or the exclusion of events in the first and second years (data not shown). For men, the point estimates for HRs eating-with-others two times a day are consistently <1.00. But for women, low HRs of 0.15 are seen for eating-with-others one time a day in the first 2 years of observation, although not beyond. This does not change our conclusions with the 10-year survival analysis. Second, the association may be affected by the duration of time spent eating alone or eating-with-others, which was not considered. Third, in Taiwanese society, older people are more likely to live with and depend on their families, so the culturally specific nature of this study may limit its applicability elsewhere. The study should be considered within a Taiwanese (of perhaps a broader Asian) context. As with cohort studies in general, there may have been confounders not considered which might have explained the associations presented. The study itself, however, has sought to consider the circumstances of eating which are usually neglected in the exploration of food and nutrient health relationships. The pathway analyses are an attempt to encompass more of the explanatory models for these relationships by way of inclusion of physical, mental and general health. The gender differences which are now recognised here and in other reports for the respective health roles of dietary quality on the one hand, and with whom the food is consumed on the other, are a challenge to more gender comprehensive public health policy.

Conclusions

Eating socially may benefit survival in elderly men through the adjunct of dietary quality; it is also positively associated with men’s mental health. For women, dietary quality is associated with survival advantage which is not apparently dependent on eating-with-others. The relative gender advantage in longevity that women have in this population is not adequately explained in the present study, except that they are likely to be the ones who eat with men who benefit from this social role of food. Thus, for men and women, the provision of a healthy social environment which increases social interactions should improve health outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Elderly Nutrition and Health Survey (NAHSIT Elderly) in Taiwan 1997–2002 project was conducted by the Institute of Biomedical Sciences of Academia Sinica and the Research Center for the Humanities and Social Sciences, Center for Survey Research, Academia Sinica, directed by Wen-Harn Pan and Su-Hao Tu, and sponsored by the Taiwan Department of Health. This study is based in part on data from Department of Health and managed by the National Health Research Institutes. The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not represent those of Department of Health or National Health Research Institutes.

Footnotes

Contributors: Y-CH, H-LC, MLW and M-SL designed the study; Y-CH, H-LC and Y-TCL performed statistical analysis; Y-CH, MLW, Y-TCL and M-SL wrote the paper; M-SL had primary responsibility for the final content.

Funding: This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology grant number MOST-103-2320-B-016-015-MY2, MOST105-2320-B-016-008 and International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI) Taiwan.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This project was approved by the ethics committees of the National Health Research Institute and Academia Sinica, Taiwan.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Rowe JW, Kahn RL. Successful aging. Gerontologist 1997;37:433–40. 10.1093/geront/37.4.433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Meiselman HL. Dimensions of the meal. J Foodservice 2008;19:13–21. 10.1111/j.1745-4506.2008.00076.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Administration for Community Living, US Department of Health and Human Services. Nutrition Services (OAA Title IIIC) - Congregate Nutrition Services. Washington, DC: Administration for Community Living, US Department of Health and Human Services, 2016. http://www.aoa.gov/AoA_programs/HPW/Nutrition_Services/index.aspx#congregate (accessed 18 Apr 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kuroda A, Tanaka T, Hirano H, et al. . Eating alone as social disengagement is strongly associated with depressive symptoms in Japanese community-dwelling older adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2015;16:578–85. 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.01.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tani Y, Sasaki Y, Haseda M, et al. . Eating alone and depression in older men and women by cohabitation status: The JAGES longitudinal survey. Age Ageing 2015;44:1019–26. 10.1093/ageing/afv145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang X, Shen W, Wang C, et al. . Association between eating alone and depressive symptom in elders: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr 2016;16:19 10.1186/s12877-016-0197-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kimura Y, Wada T, Okumiya K, et al. . Eating alone among community-dwelling Japanese elderly: association with depression and food diversity. J Nutr Health Aging 2012;16:728–31. 10.1007/s12603-012-0067-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nijs KA, de Graaf C, Siebelink E, et al. . Effect of family-style meals on energy intake and risk of malnutrition in dutch nursing home residents: a randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2006;61:935–42. 10.1093/gerona/61.9.935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tani Y, Kondo N, Takagi D, et al. . Combined effects of eating alone and living alone on unhealthy dietary behaviors, obesity and underweight in older Japanese adults: Results of the JAGES. Appetite 2015;95:1–8. 10.1016/j.appet.2015.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lee MS, Huang YC, Su HH, et al. . A simple food quality index predicts mortality in elderly Taiwanese. J Nutr Health Aging 2011;15:815–21. 10.1007/s12603-011-0081-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schoevers RA, Geerlings MI, Beekman AT, et al. . Association of depression and gender with mortality in old age. Results from the Amsterdam Study of the Elderly (AMSTEL). Br J Psychiatry 2000;177:336–42. 10.1192/bjp.177.4.336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Clausen T, Wilson AO, Molebatsi RM, et al. . Diminished mental- and physical function and lack of social support are associated with shorter survival in community dwelling older persons of Botswana. BMC Public Health 2007;7:144 10.1186/1471-2458-7-144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sahyoun NR, Jacques PF, Dallal GE, et al. . Nutrition Screening Initiative Checklist may be a better awareness/educational tool than a screening one. J Am Diet Assoc 1997;97:760–4. 10.1016/S0002-8223(97)00188-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ek S. Gender differences in health information behaviour: a Finnish population-based survey. Health Promot Int 2015;30:736–45. 10.1093/heapro/dat063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Redondo-Sendino A, Guallar-Castillón P, Banegas JR, et al. . Gender differences in the utilization of health-care services among the older adult population of Spain. BMC Public Health 2006;6:155 10.1186/1471-2458-6-155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Umberson D, Wortman CB, Kessler RC. Widowhood and depression: explaining long-term gender differences in vulnerability. J Health Soc Behav 1992;33:10–24. 10.2307/2136854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wu SJ, Chang YH, Wei IL, et al. . Intake levels and major food sources of energy and nutrients in the Taiwanese elderly. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2005;14:211–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cheng SL. Eating-with-others and the health of older people. School of Public Health. National Defense Medical Center 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Huang YC, Lee MS, Pan WH, et al. . Validation of a simplified food frequency questionnaire as used in the Nutrition and Health Survey in Taiwan (NAHSIT) for the elderly. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2011;20:134–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee M-S, Chen RC-Y, Chang Y-H, et al. . Physical function mitigates the adverse effects of being thin On mortality in a free-living older Taiwanese cohort. J Nutr Health Aging 2012;16:776–83. 10.1007/s12603-012-0379-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chuang S-Y, Chang H-Y, Lee M-S, et al. . Skeletal muscle mass and risk of death in an elderly population. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases 2014;24:784–91. 10.1016/j.numecd.2013.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. . A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen RC, Chang YH, Lee MS, et al. . Dietary quality may enhance survival related to cognitive impairment in Taiwanese elderly. Food Nutr Res 2011;55:7387 10.3402/fnr.v55i0.7387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gamborg M, Jensen GB, Sørensen TI, et al. . Dynamic path analysis in life-course epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol 2011;173:1131–9. 10.1093/aje/kwq502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Locher JL, Robinson CO, Roth DL, et al. . The effect of the presence of others on caloric intake in homebound older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2005;60:1475–8. 10.1093/gerona/60.11.1475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Trichopoulou A, Kouris-Blazos A, Wahlqvist ML, et al. . Diet and overall survival in elderly people. BMJ 1995;311:1457–60. 10.1136/bmj.311.7018.1457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Davis MA, Randall E, Forthofer RN, et al. . Living arrangements and dietary patterns of older adults in the United States. J Gerontol 1985;40:434–42. 10.1093/geronj/40.4.434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen RC, Lee MS, Chang YH, et al. . Cooking frequency may enhance survival in Taiwanese elderly. Public Health Nutr 2012;15:1142–9. 10.1017/S136898001200136X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ng TP, Jin A, Feng L, et al. . Mortality of older persons living alone: Singapore Longitudinal Ageing Studies. BMC Geriatr 2015;15:126 10.1186/s12877-015-0128-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bowling A. Mortality after bereavement: a review of the literature on survival periods and factors affecting survival. Soc Sci Med 1987;24:117–24. 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90244-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-016575supp001.pdf (58.3KB, pdf)