Abstract

Background and Purpose

We recently reported a time-sensitive, cooperative, anti-tumor effect elicited by radiation (RT) and intra-tumoral-immunocytokine injection in vivo. We hypothesized that RT triggers transcriptional-mediated changes in tumor expression of immune susceptibility markers at delayed time points, which may explain these previously observed time-dependent effects.

Materials and Methods

We examined the time course of changes in expression of immune susceptibility markers following in vitro or in vivo RT in B78 murine melanoma and A375 human melanoma using flow cytometry, immunoblotting, and qPCR.

Results

Flow cytometry and immunoblot revealed time-dependent increases in expression of death receptors and T cell co-stimulatory/co-inhibitory ligands following RT in murine and human melanoma. Using high-throughput qPCR, we observed comparable time courses of RT-induced transcriptional upregulation for multiple immune susceptibility markers. We confirmed analogous changes in B78 tumors irradiated in vivo. We observed upregulated expression of DNA damage response markers days prior to changes in immune markers, whereas phosphorylation of the STAT1 transcription factor occurred concurrently with changes following RT.

Conclusions

This study highlights time-dependent, transcription-mediated changes in tumor immune susceptibility marker expression following RT. These findings may help in the design of strategies to optimize sequencing of RT and immunotherapy in translational and clinical studies.

Keywords: immunomodulation, radiation, melanoma, immunotherapy

Introduction

Radiation therapy (RT) kills tumor cells through the induction of DNA damage. However, it has long been recognized that tumor sensitivity to RT may be impacted by host immunity, and conversely, RT may affect tumor immune susceptibility [1, 2]. Prior studies have suggested that the mechanisms whereby RT may modulate tumor immune susceptibility include immediate local release of inflammatory cytokines, induction of immunogenic cell death, and temporary local eradication of suppressor (as well as effector) immune lineages [3]. In addition, multiple studies of individual tumor markers have demonstrated that RT may induce phenotypic changes in the plasma membrane expression of specific markers of immune susceptibility on tumor cells that survive RT [4]. Pre-clinical and early-phase clinical data from studies combining RT with immunotherapy suggest that, collectively, these mechanisms may result in enhanced antigen cross-presentation [5] and increased diversity of the anti-tumor T cell response following RT [6].

Prior studies have consistently demonstrated phenotypic upregulation of FAS and MHC-I following of RT [7–9], and recent studies have suggested non-cell autonomous mechanisms whereby RT may influence tumor expression of the checkpoint ligand, PD-L1 [10]. The time course, potentially shared underlying mechanisms, and the possibility of a broader impact of RT on expression of other phenotypic markers of tumor immune susceptibility remain to be clarified. Others and we have demonstrated the cooperative interaction of combination treatment with radiation and immunotherapy in vivo. Many of these studies demonstrate that the timing and sequencing of radiation and immunotherapy may be critical for optimizing cooperative anti-tumor activity [11, 12]. Illustratively, in preclinical studies we recently demonstrated a cooperative interaction between RT and the antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) response to tumor-specific monoclonal antibodies (mAb) in murine melanoma [11]. This effect was enhanced using a combination of RT and immunocytokine, a fusion of the tumor-specific antibody with IL2, resulting in elimination of 5-week established tumors in most mice and a memory T cell response. However, this effect was time-sensitive and observed when immunotherapy was delivered 6–10 days after RT but not with administration on days 1–5 or 11–15 [11]. Therefore, it is valuable to understand not only how RT may affect tumor cell susceptibility to immune response but also to define the time course and mechanism of such effects.

Here, we investigate the effect of RT on the expression of multiple immune susceptibility markers over time, at both transcriptional and post-translational levels. Our results suggest a broad and potentially coordinated pattern of immunomodulation in murine and human melanoma cells following RT and elucidate the time course over which these changes take place.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines

The human melanoma A375 cell line was obtained from ATCC. Cells were grown in DMEM (Mediatech Inc.) and were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1 µg/mL hydrocortisone, and 1% penicillin and streptomycin. The murine melanoma B78-D14 (B78) cell line is derived from B16 melanoma as previously described [13] and was obtained from Ralph Reisfeld (Scripps Research Institute) in 2002. B78 cells were grown in RPMI-1640 w/L-glutamine (Mediatech Inc.) and were supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100ug/mL streptomycin. Cell line authentication was performed per ATCC guidelines using morphology, growth curves, and Mycoplasma testing within 6 months of use. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma. Cell culture media and supplements were obtained from Life Technologies, Inc.

Radiation

All RT (in vitro and in vivo) was delivered in a single fraction. Delivery of radiation in vitro was performed using a 137Cs-irradiator (JL Shepherd & Associates Model 109) or an X-ray biological cabinet irradiator X-RAD 320 (Precision X-Ray, Inc). Delivery of RT in vivo was performed using an X-ray biological cabinet irradiator X-RAD 320 (Precision X-Ray, Inc). The dose rate for RT delivery in all experiments was approximately 2Gy/min. Dosimetric calibration and monthly quality assurance checks were performed on these irradiators by University of Wisconsin Medical Physics Staff. Unless otherwise indicated, the dose of RT delivered to B78 melanoma cells and tumors was 12 Gy and the dose delivered to A375 melanoma cells was 9 Gy. For B78 melanoma, selection of RT dose was based on our prior findings of a time-sensitive in vivo synergy between single fraction 12 Gy and intra-tumor injection of specific immunotherapies [11]; that observation provided initial rationale for this study. For A375, which exhibits a greater intrinsic sensitivity to RT, a comparable biologically effective dose (9 Gy) was chosen, as determined by clonogenic survival assays.

Cell Culture

RT was delivered when cells were approximately 60–70% confluent. Cells were not synchronized prior to RT. Following RT, cell media was exchanged with fresh media every other day but cells were not trypsinized or re-plated. Many cells were observed to die and detach from the plate after RT. This cellular debris was discarded with media changes. Only adherent cells were collected and analyzed for in vitro studies. Consequently, the great majority of cells analyzed at each time point in our in vitro assays were viable and in flow cytometry studies the viability of analyzed cells, as determined by dye exclusion, was comparable between control and radiated samples. In order to ensure enough material for analysis, for later time points (> 3 days following RT) multiple plates were treated with RT and harvested together. Cells harvested from these synchronously treated plates generated clonogenic colonies (typically >50 per plate) and these cells were pooled for analyses. Untreated controls cells were passaged twice weekly to maintain a sub-confluent state during the experiment. In preparation for harvesting at the conclusion of a time course experiment, these cells were seeded at 60% confluence at 2.5 days prior to harvest and harvested at ~ 90% confluence. As an additional control, we also tested the effect of tissue culture conditions on non-radiated cells. For this, we plated ~ 100 A375 or B78 cells per plate and cultured these for up to 19 days like radiated cells by changing media every other day but not splitting or re-plating.

Quantification of mRNA Expression

Relative mRNA levels of all targets were quantified via real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) using a Bio-Rad iQ5 RT-qPCR Detection System and Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Life Technologies). All reactions were performed in technical and biological triplicates. PGK was used as an endogenous control. Fold changes after treatments were normalized to an untreated control sample. RNA isolation and reverse transcription procedures and a list of all targets and detailed primer information for each molecule are provided in the Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Flow Cytometry Analysis

Flow cytometry was performed as previously described [14] using a MacsQuant Analyzer (Miltenyi Biotec). Cells were labeled as indicated using anti-CD80 (EBiosciences, 16-10A1), anti-DR5 (EBiosciences, MDS-1 PE), anti-BrdU (Cell Signaling Technology, Bu20a), or anti-PD-L1 (EBiosciences, MIH5) fluorescent-conjugated monoclonal antibodies and/or DAPI. For all studies, cells were gated using forward- and side-scatter to identify single cells and DAPI or Ghost Red Dye 780 (Tonbo Biosciences) exclusion was used then to identify live cells. Analyses of immune susceptibility markers was performed only on live single cells. FlowJo Software was used for analysis.

Immunoblotting

Protein isolation, quantitation, and immunoblotting were performed as previously described [15]. Anti-DR5, anti-Fas, anti-PD-L1, anti-phospho-STAT1, anti-phospho-STAT3, anti-STAT1, and anti-STAT3 primary antibodies and HRP-linked secondary antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technologies. The anti-alpha-Tubulin primary antibody was obtained from Calbiochem. All other primary antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Technologies.

shRNA Knockdown of STAT1

STAT1 specific short hairpin RNA (shRNA), as well as non-target shRNA, were purchased from Origene and transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (Invitrogen). Knockdown of STAT1 was confirmed by immunoblot. Procedures and constructs are described specifically in the Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Murine Tumor Models

Mice were housed and treated under a protocol approved by the institutional animal care and use committee. Female C57BL/6 mice were purchased at age 6 to 8 weeks from Taconic. B78 tumors were engrafted by subcutaneous flank injection of 2 × 106 tumor cells. Tumor size was determined using calipers and volume approximated as (width2 × length)/2. Mice were randomized immediately before treatment. Treatment began when tumors were well-established (~200 mm3), which occurred approximately 5 weeks after tumor implantation.

Statistical Analysis

Prism 5 (GraphPad Software) was used for all statistical analyses. Two-tailed, unpaired Student’s T tests were used to determine significance of mean differences. For groups that differed in variance, an unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction was used. All gene expression experiments were performed in biological and technical triplicates. All other data presented reflects at least two independent experiments and is reported as mean ± SEM. For all graphs, *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; and ****, P < 0.0001.

Results

Increased protein expression of immune susceptibility markers in murine and human melanoma following RT in vitro

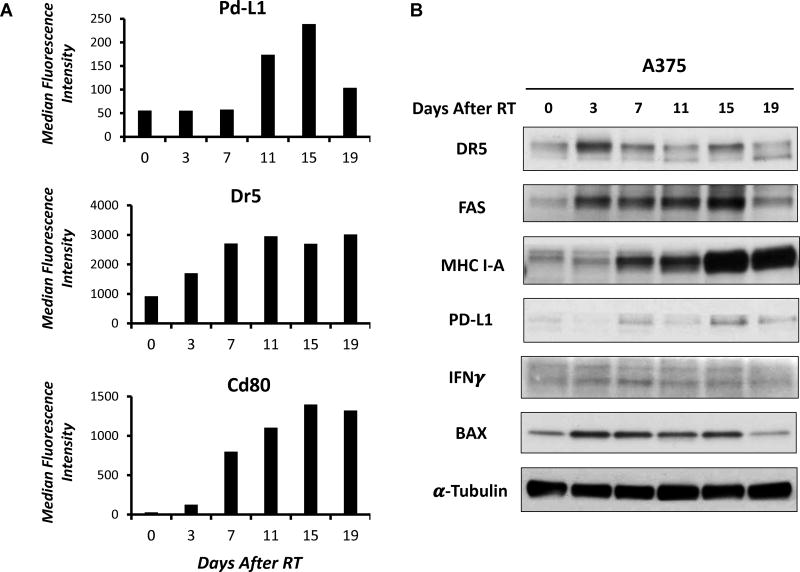

To begin investigating the time course of phenotypic changes in immune susceptibility markers on B78 murine melanoma cells following a single fraction of 12 Gy RT, we measured the effect of radiation on protein expression of the death receptor DR5 and the T cell co-stimulatory/co-inhibitory ligands CD80 and PD-L1. These markers have been reported to be upregulated following RT in other tumor lines; however, the relative time course of these effects has not been clarified [16]. We selected a single fraction 12 Gy dose here based on our prior findings of a time-sensitive cooperative in vivo interaction between this RT regimen and intra-tumor injection of specific immunotherapies [11]. Using flow cytometry gated on live cells only, here we observed a time-dependent increase in the expression of Dr5, Pd-L1, and Cd80 following in vitro delivery of 12 Gy RT (Fig. 1A). Expression of these proteins was observed to increase starting 3–7 days following RT and peak levels were reached 11–15 days after RT. Increased expression of Pd-L1 appeared to be transient, as expression was observed to decrease ~19 days after treatment. Expression of Cd80 and Dr5, on the other hand, remained elevated even 19 days after treatment, suggesting a more durable effect.

Figure 1. RT-induced changes in protein expression of immune susceptibility markers in murine and human melanoma in vitro.

A. Following single fraction 12 Gy RT, plasma membrane expression of Pd-L1, Dr5, and Cd80 were measured via flow cytometry. RT (12 Gy) was delivered to B78 murine melanoma cells in vitro, and samples were collected prior to RT or 3, 7, 11, 15, or 19 days following RT for flow cytometry analysis. Graphs depict median fluorescence intensity levels. B. RT-induced changes in expression of immune- and DNA damage-related proteins was measured via immunoblot. A375 cells irradiated (9 Gy) in vitro were collected prior to RT or 3, 7, 11, 15, or 19 days following RT and protein expression was measured via immunoblot.

In the human melanoma cell line, A375, immunoblotting demonstrated that a similar biologically effective dose of RT (9 Gy, single fraction) delivered in vitro induced a comparable time-dependent increase in the expression of death receptors (DR5, FAS), MHC Class I molecules, type II interferons, T-cell co-inhibitory receptors (PD-L1), and proteins involved in the DNA damage response (BAX) (Fig. 1B). As expected, expression of death receptors (FAS, DR5) and the apoptotic protein, BAX, began to increase shortly after RT (day 3). Expression of interferon gamma (IFNγ), MHC I-A, and PD-L1 increased at later time points, around 7 days after RT, and levels remained elevated until at least day 15. Expression of MHC I-A and PD-L1 increased further at even later time points, reaching peak levels 15 days following RT. In both B78 and A375 cells we have observed induction of gamma-H2AX foci as a marker of RT-induced double-stranded DNA breaks, at 1 hour following single fraction in vitro RT (12 Gy and 9 Gy, respectively) however this appeared to resolve prior to the earliest 2.5 day time point that we have evaluated here (data not shown). We have confirmed that following these single fraction doses of RT there remain a fraction of clonogenic [Supplementary Figure 1A (B78); previously published for A375 (17)] and proliferative cells (Supplementary Figure 1B).

RT increases mRNA transcript levels of immune susceptibility marker genes in murine melanoma in vitro

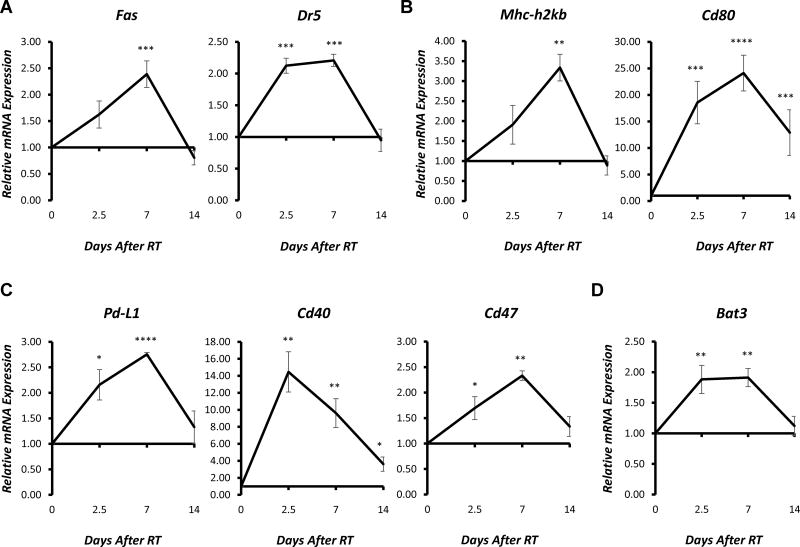

To determine whether the observed changes in expression of immune susceptibility marker proteins result from changes in gene transcription, we measured the effect of RT on the relative mRNA expression of Fas, Dr5, Cd80, Pd-L1, as well as a broader panel of immune susceptibility markers in B78 murine melanoma cells using quantitative PCR. For this, mRNA was extracted from non-radiated control cells or from cells at 2.5, 7, or 14 days after in vitro delivery of a single fraction of 12 Gy. All changes in plasma membrane protein expression observed by flow cytometry (Fig. 1A) were similarly observed at the mRNA level by qPCR (Fig. 2). Furthermore, we observed that RT induced comparable transcriptional effects in multiple other immune-related genes over a similar time course (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 2, 3, 4). For the majority of targets tested, RT-induced gene expression peaked ~7 days after RT, and this appeared to be consistent across a variety of markers involved in both innate and adaptive immunity. Nearly all of the targets with patterns of expression that deviated from this trend (Bax, Puma, Mdm2, and others) were genes involved in the DNA damage response (Supplementary Fig. 4B), which was consistent with expected patterns of rapid transcriptional upregulation of this machinery at 24–72 hours after RT [17–18]. Changes in gene expression for these markers peaked at the earliest measured time point, collected 2.5 days (60 hours) following RT. As an additional control, we plated non-radiated cells at very low concentration (~ 100 cells/plate) and allowed these cells to grow without passage for the duration of a 19-day time course with every other day media changes and no passaging. These non-treated controls cultured in a comparable manner to our radiated cells show no difference relative to or passaged non-treated control cells in the expression of immune susceptibility markers (Supplementary Fig 1C). Together, these results provide evidence that there is a delayed effect of RT on murine melanoma cells, resulting in changes in expression of multiple immune susceptibility markers, which appears, at least in part, to be transcription-mediated.

Figure 2. RT-induced changes in gene expression of immune susceptibility markers in murine melanoma in vitro.

RT (12 Gy, single fraction) was delivered to B78 murine melanoma cells in vitro, and samples were collected prior to RT or 2.5, 7, or 14 days following RT for RNA isolation. Reverse transcription was used to generate cDNA, and gene expression was measured using RT-qPCR analysis. Graphs depict the time course of RT-induced increases in relative mRNA expression (fold change) of selected death receptors (A), immune-related receptors (B), T cell co-stimulatory/co-inhibitory receptors and ligands (C), and NK cell receptors and ligands (D) normalized to untreated controls. Data represent the mean ± SEM of three biological and technical replicates.

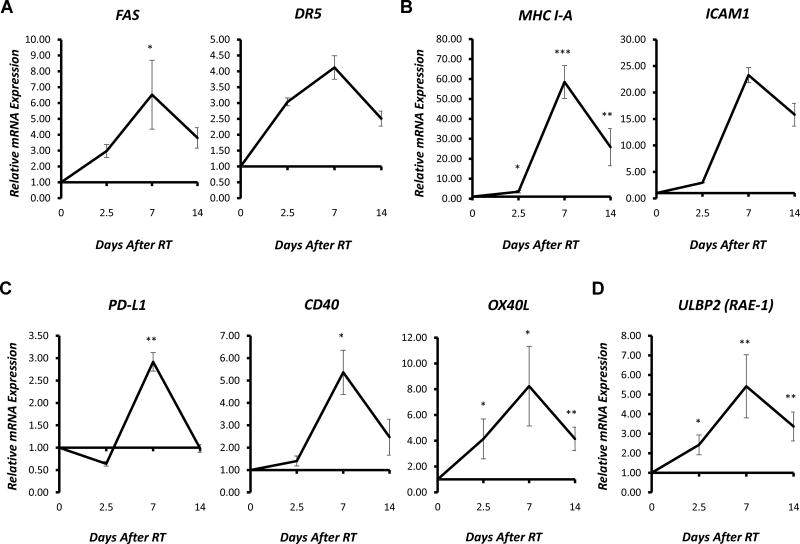

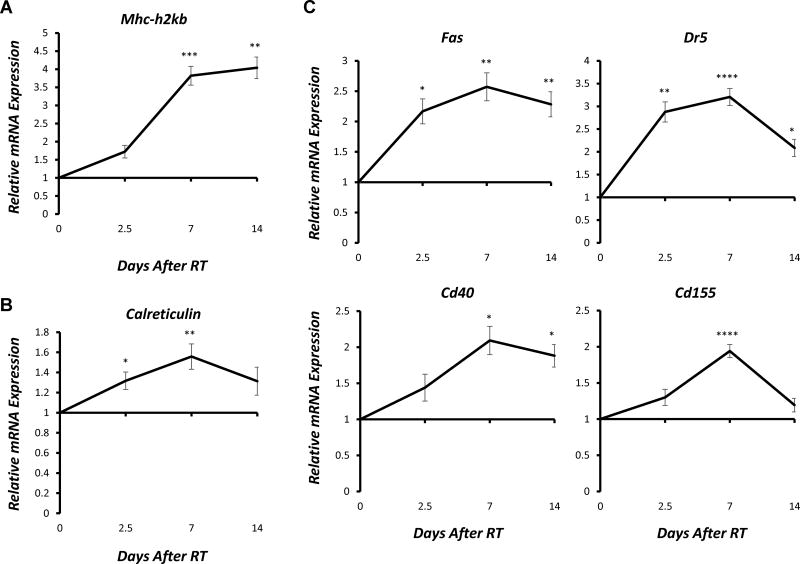

RT increases gene expression of immune susceptibility markers in A375 human melanoma in vitro

We employed high-throughput qPCR to evaluate whether comparable transcription-mediated changes in expression of immune susceptibility marker genes were observed in human melanoma cells following RT. mRNA was isolated from A375 melanoma cells prior to RT or at 2.5, 7, or 14 days following in vitro delivery of a single 9 Gy fraction. qPCR analyses revealed that RT-induced increases in gene expression of MHC I-A, PD-L1, FAS, and DR5 peaked immediately prior to the observed changes in protein expression (Figure 3). These findings further suggest that changes in transcription contribute to the observed changes in protein expression of immune susceptibility markers following RT in melanoma cells.

Figure 3. RT-induced changes in gene expression of immune susceptibility markers in human melanoma in vitro.

RT (9 Gy, single fraction) was delivered to A375 murine melanoma cells in vitro, and samples were collected prior to RT or 2.5, 7, or 14 days following RT for RNA isolation. Reverse transcription was used to generate cDNA, and gene expression was measured using RT-qPCR analysis. Graphs depict the time course of RT-induced increases in relative mRNA expression (fold change) of selected death receptors (A), immune-related receptors (B), T cell co-stimulatory/co-inhibitory receptors and ligands (C), and NK cell receptors and ligands (D) normalized to untreated controls. Data represent the mean ± SEM of three biological and technical replicates.

Across the panel of genes examined, we observed that a wide variety of immune susceptibility markers were affected by RT, and RT induced a similar time course of transcriptional effects in the majority of genes (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. 5, 6). Akin to the results observed in murine melanoma, changes in expression of most immune-related genes peaked approximately 7 days following RT treatment in A375 human melanoma cells. This was true for markers involved in both the adaptive and innate immune response. As expected, RT-induced increased expression of genes involved in the DNA damage response pathway (TP53, p21, MDM2, and BAX) were observed beginning at the earliest 2.5-day time point following RT (Supplementary Fig. 7). Though induction of MDM2 gene expression peaked at this 2.5-day time point, expression of p21, TP53, and BAX peaked 7 days following RT. These markers of DNA damage response were included as positive controls for RT induced expression changes but also provide insight on the relative timing and duration of RT effect on these markers as compared to that on immune susceptibility markers.

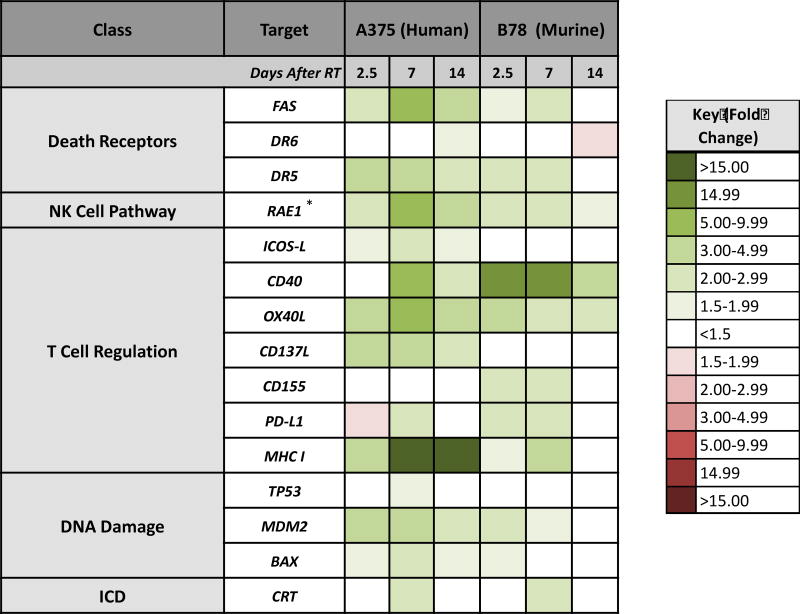

In order to compare results obtained in these murine and human melanoma cell lines, we generated a heat map summarizing the changes in gene expression induced by RT over time. While relative expression, or fold change, values were not identical, the trend and time course of RT-induced changes in gene expression were consistent across species for nearly all tested genes (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Summary of RT-induced changes in gene expression over time.

B78 murine melanoma cells and A375 human melanoma cells were radiated (12 Gy and 9 Gy single fractions, respectively), and samples were collected prior to RT or 2.5, 7, or 14 days following RT for RNA isolation. The heat map illustrates the time course of RT-induced changes in relative mRNA expression (fold change) of different classes of immune susceptibility markers and DNA-damage markers in each species, which were normalized to untreated controls. Data represent the mean of three biological and technical replicates. *, Represents gene expression of ULBP2 (RAE-1) in A375 human melanoma and Rae-1-b in B78 murine melanoma.

Analogous changes in expression of immune susceptibility markers following RT in vivo

Next, we sought to determine whether the changes in gene and protein expression induced by RT in vitro would also be observed in vivo. To do this, we engrafted C57BL/6 mice with syngeneic B78 murine melanoma and allowed tumors to grow for ~5 weeks. Tumors were then treated with a single fraction of 12 Gy or sham RT. Tumors were excised 2.5, 7, or 14 days following RT, along with untreated control tumors. Resected tumors were immediately flash frozen, and mRNA was isolated. qPCR was performed to evaluate expression of select immune susceptibility markers from the panel tested in vitro. We found that the RT-induced changes in gene expression observed in in vivo (Fig. 5, Supplementary Fig. 8) closely mirrored those observed after in vitro RT (Fig. 2).

Figure 5. Time course of RT-induced immunomodulation in murine melanoma in vivo.

Mice bearing syngeneic B78 murine melanoma tumors were treated to the tumor-bearing flank with a single 12 Gy fraction or sham RT in vivo. 2.5, 7, or 14 days following RT, tumors were excised along with untreated control tumors, and total RNA was isolated. Reverse transcription was used to generate cDNA, and gene expression was measured using RT-qPCR analysis. Graphs depict RT-induced changes in relative mRNA expression (fold change) of selected death receptors, NK cell receptors and ligands, T cell co-stimulatory/co-inhibitory receptors and ligands, and other immune-related genes normalized to untreated controls. Data represent the mean ± SEM of five matched pairs of irradiated and non-irradiated tumors. All experiments were performed in technical triplicates.

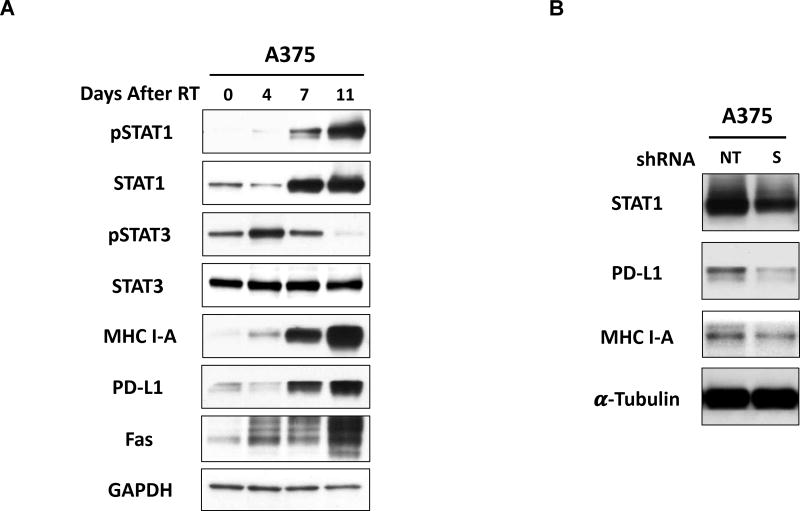

Activation of STAT1 signaling occurs concurrently with RT-induced immunomodulation in vitro

Previous studies have demonstrated that RT induces expression of interferons and activation of IFN-induced signaling in tumors [19–21]. Additional studies have implicated IFN-regulated pathways, including the signal transducer and activator of transcription-1 (STAT-1) signaling pathway, in regulating expression of various immune susceptibility markers in multiple tumor types, including MHC-I, PD-L1, and others [22–24]. To begin exploring potential pathways that may regulate RT-induced immunomodulation in melanoma, we performed immunoblotting to examine changes in expression of proteins from various RT-induced signaling pathways at the same time points where we had detected RT-induced immunomodulation. Interestingly, we observed increased expression and activation (phosphorylation) of STAT1 following RT, and this occurred over an identical time course as changes in expression of immune susceptibility markers, including MHC I, FAS, and PD-L1 (Fig. 6A). Notably, phosphorylation of STAT3 appeared to decrease as expression of STAT1 and immune-stimulatory proteins increased (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6. STAT1 activation occurs concurrently with RT-induced immunomodulation and may regulate the expression of specific immune susceptibility markers in melanoma.

A. RT induced activation (phosphorylation) and increased expression of STAT1 in human melanoma. A375 cells radiated (9 Gy, single fraction) in vitro were collected prior to RT or 4, 7, or 11 days following RT and protein expression was measured via immunoblot. B. Transient knockdown of STAT1, using shRNA transfection, resulted in decreased protein expression of PD-L1 and MHC I-A in human melanoma cells in vitro. A375 cells were transfected with 5ug of STAT1 or non-target shRNA, and protein samples were isolated 72h after transfection for immunoblotting.

Given these findings, we hypothesized that STAT1 may play a role in regulating expression of immune susceptibility markers in melanoma. To test this, we examined the effect of STAT1 shRNA knockdown on expression of selected immune susceptibility markers in A375 human melanoma cells. Cells treated with STAT1 shRNA showed decreased protein expression of PD-L1 and MHC I-A compared to those treated with a negative control shRNA (Fig. 6B).

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate a consistent time course of transcription-mediated phenotypic changes in multiple immune susceptibility markers following in vitro and in vivo RT. These effects are largely conserved between murine and human melanoma lines and include upregulation of death receptors (Fas, DR5), NK cell ligands (Rae-family members), T cell co-signaling molecules (CD40, CD80, CD70, PD-L1), MHC-I, and Calreticulin. The majority of these changes in gene expression peaked ~7 days following RT and manifested as changes in protein expression 7–15 days following RT. We have particularly focused on the time course of changes in the expression of immune susceptibility markers because this timing has not been investigated thoroughly but may be critical to the optimal integration of radiation with immunotherapies. In this initial report, we have focused on the effects of single fraction RT at doses (9–12 Gy) which are feasible to deliver clinically. In follow-up studies, it will be important to consider further the potential impact of RT dose, fractionation, and radio-sensitizers (chemotherapeutics and molecular targeted therapies) on the timing and magnitude of phenotypic changes in tumor cell expression of immune susceptibility markers.

The specific molecular mechanisms that give rise to this broad regulation of immune susceptibility markers following RT remains to be elucidated. Some studies have implicated members of the DNA damage response pathway, including ATM and p53, in regulating expression of specific immune susceptibility markers, such as OX40-L, TAP1, and DR5 [25–26]. We observe maximal expression of selected DNA damage response-related gene transcripts 2.5–7 days after RT. Further studies will be needed to determine whether and how DNA damage response pathways may contribute to the phenotypic changes that we report here for immune susceptibility markers following RT. On the other hand, we observed maximal activation and increased protein expression of STAT1 at a more delayed interval, 7–11 days after RT, and STAT1 knockdown resulted in decreased protein expression of PD-L1 and MHC I-A. At the same time, we observed diminished activation of STAT3, which prior studies have shown to suppress STAT1 activity along with inflammatory immune pathways [27–28]. Although these results do not provide direct evidence that STAT1 mediates the RT-induced immunomodulation observed, they support prior studies that have implicated the STAT1 signaling pathway in regulating expression of MHC-I, PD-L1, and various immune-stimulatory cytokines [29–30]. Given that the STAT signaling pathway is activated directly and indirectly (via IFN signaling) by RT, we hypothesize that STAT1 plays a key role in regulating RT-induced immunomodulation and we are moving ahead with further studies to test this. Importantly, identifying pathways giving rise to RT-induced effects on tumor immune susceptibility markers may provide novel opportunities to further enhance the immunogenicity of RT through combination treatments with molecularly targeted therapeutics. When combined, these therapies may optimally augment response to established and emerging immunotherapies.

Intriguingly, the period during which we have observed maximal induction of immune susceptibility marker expression correlates with a window of maximal sensitivity to the administration of tumor-specific immunocytokine following RT that we have observed for these same B78 melanoma tumors [11]. As established and newly developed immunotherapies are utilized more frequently in combination with RT, it will be of great value to optimize the timing and sequencing of these therapies to take best advantage of synergistic effects. It is possible that the phenotypic changes we identify here will similarly correlate with or even predict windows of maximal tumor susceptibility to immunotherapies following RT; however, this remains to be tested. In addition, among the specific markers of immune susceptibility that we have identified as upregulated following RT are inhibitory proteins that might suppress local immune response. Targeting and antagonizing these markers may offer a unique opportunity to enhance the immunogenicity of RT. On the other hand, it will also be prudent to consider the potential impact of these phenotypic changes on the toxicity of combined treatment with RT and immunotherapy.

Over the past decade, immunotherapy has emerged as a new horizon for cancer treatment. Various immunotherapies are now demonstrating clear benefit for many cancer patients. More recently, a growing number of clinical studies have been undertaken to investigate combinations of immunotherapies with conventional therapies, including radiation [31]. Although the immune-activating effects of radiation have been well characterized in preclinical models, clinical realization of the potential for RT to augment response to immunotherapy will require carefully planned clinical studies. A comprehensive understanding of the extent and time course of RT-induced effects on markers of immune susceptibility in tumor cells and normal tissues, along with greater understanding of the effects of RT on tumor immune infiltrates [32], will be valuable to the rational design of such clinical studies. Importantly, our in vitro findings with flow cytometry come from only living cells, which were resistant to the cytotoxic effects of moderately high dose RT. The observation of potentially heightened immune susceptibility among these RT-resistant cells suggests an important mechanism for synergistic interaction with immunotherapies. In this report, we establish a time course over which these phenotypic changes occur across a diverse panel of immune receptors and ligands in murine and human melanoma.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Department of Human Oncology Head and Neck Cancer Research Fund (PMH) and the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center Core Grant (P30 CA014520).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Stone HB, Peters LJ, Milas L. Effect of host immune capability on radiocurability and subsequent transplantability of a murine fibrosarcoma. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1979;63:1229–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Budach W, Taghian A, Freeman J, Gioioso D, Suit HD. Impact of stromal sensitivity on radiation response of tumors. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1993;85:988–93. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.12.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Demaria S, Bhardwaj N, McBride WH, Formenti SC. Combining radiotherapy and immunotherapy: a revived partnership. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:655–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wattenberg MM, Fahim A, Ahmed MM, Hodge JW. Unlocking the combination: potentiation of radiation-induced antitumor responses with immunotherapy. Radiat Res. 2014;182:126–38. doi: 10.1667/RR13374.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharabi AB, Nirschl CJ, Kochel CM, et al. Stereotactic Radiation Therapy Augments Antigen-Specific PD-1-Mediated Antitumor Immune Responses via Cross-Presentation of Tumor Antigen. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015;3:345–55. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Twyman-Saint Victor C, Rech AJ, Maity A, et al. Radiation and dual checkpoint blockade activate non-redundant immune mechanisms in cancer. Nature. 2015;520:373–7. doi: 10.1038/nature14292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reits EA, Hodge JW, Herberts CA, et al. Radiation modulates the peptide repertoire, enhances MHC class I expression, and induces successful antitumor immunotherapy. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1259–71. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheard MA, Vojtesek B, Janakova L, Kovarik J, Zaloudik J. Up-regulation of Fas (CD95) in human p53wild-type cancer cells treated with ionizing radiation. Int J Cancer. 1997;73:757–62. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19971127)73:5<757::aid-ijc24>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reap EA, Roof K, Maynor K, Borrero M, Booker J, Cohen PL. Radiation and stress-induced apoptosis: a role for Fas/Fas ligand interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:5750–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deng L, Liang H, Burnette B, Weicheslbaum RR, Fu YX. Radiation and anti-PD-L1 antibody combinatorial therapy induces T cell-mediated depletion of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and tumor regression. Oncoimmunology. 2014;3:e28499. doi: 10.4161/onci.28499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris ZS, Guy EI, Francis DM, et al. In Situ Tumor Vaccination by Combining Local Radiation and Tumor-Specific Antibody or Immunocytokine Treatments. Cancer Res. 2016;76:3929–41. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young KH, Baird JR, Savage T, et al. Optimizing Timing of Immunotherapy Improves Control of Tumors by Hypofractionated Radiation Therapy. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haraguchi M, Yamashiro S, Yamamoto A, et al. Isolation of GD3 synthase gene by expression cloning of GM3 alpha-2,8-sialyltransferase cDNA using anti-GD2 monoclonal antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10455–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alderson KL, Luangrath M, Elsenheimer MM, et al. Enhancement of the anti-melanoma response of Hu14.18K322A by alphaCD40 + CpG. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013;62:665–75. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1372-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li C, Huang S, Armstrong EA, et al. Antitumor Effects of MEHD7945A, a Dual-Specific Antibody against EGFR and HER3, in Combination with Radiation in Lung and Head and Neck Cancers. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14:2049–59. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernstein MB, Garnett CT, Zhang H, et al. Radiation-Induced Modulation of Costimulatory and Coinhibitory T-Cell Signaling Molecules on Human Prostate Carcinoma Cells Promotes Productive Antitumor Immune Interactions. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2014;29:153–61. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2013.1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Werner LR, Huang S, Francis DM, et al. Small Molecule Inhibition of MDM2-p53 Interaction Augments Radiation Response in Human Tumors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14:1994–2003. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-1056-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim KH, Yoo HY, Joo KM, et al. Time-course analysis of DNA damage response-related genes after in vitro radiation in H460 and H1299 lung cancer lines. Exp Mol Med. 2011;43:419–26. doi: 10.3858/emm.2011.43.7.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burnette BC, Liang H, Lee Y, et al. The efficacy of radiotherapy relies upon induction of type i interferon-dependent innate and adaptive immunity. Cancer Res. 2011;71:2488–2496. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lugade AA, Sorensen EW, Gerber SA, Moran JP, Frelinger JG, Lord EM. Radiation-induced IFN-g Production within the Tumor Microenvironment Influences Antitumor Immunity. J Immunol. 2008;180:3132–39. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deng L, Liang H, Xu M, et al. STING-Dependent Cytosolic DNA Sensing Promotes Radiation-Induced Type I Interferon-Dependent Antitumor Immunity in Immunogenic Tumors. Immunity. 2014;41:843–52. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wan S, Pestka S, Jubin RG, Lyu YL, Tsai YC, Liu LF. Chemotherapeutics and radiation stimulate MHC class I expression through elevated interferon-beta signaling in breast cancer cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32542. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gonzalez-Navajas JM, Lee J, David M, Raz E. Immunomodulatory functions of type I interferons. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:125–135. doi: 10.1038/nri3133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shin DS, Zaretsky JM, Escuin-Ordinas, et al. Primary Resistance to PD-1 Blockade Mediated by JAK1/2 Mutations. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:188–201. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu K, Wang J, Zhu J, Jiang J, Shou J, Chen X. p53 induces TAP1 and enhances the transport of MHC class I peptides. Oncogene. 1999;18(54):7740–7747. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sheikh MS, Burns TF, Huang Y, et al. p53-dependent and -independent regulation of the death receptor KILLER/DR5 gene expression in response to genotoxic stress and tumor necrosis factor alpha. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1593–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pensa S, Regis G, Boselli D, et al. Madame Curie Bioscience Database [Internet] Austin (TX): Landes Bioscience; 2000–2013. STAT1 and STAT3 in Tumorigenesis: Two Sides of the Same Coin? [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qing Y, Stark GR. Alternative activation of STAT1 and STAT3 in response to interferon-gamma. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:41679–41685. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406413200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meissl K, Macho-Maschler S, Muller M, Strobl B. The good and the bad faces of STAT1 in solid tumours. Cytokine. 2017;89:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Concha-Benavente F, Srivastava RM, Trivedi S, et al. Identification of the Cell-Intrinsic and -Extrinsic Pathways Downstream of EGFR and IFNgamma That Induce PD-L1 Expression in Head and Neck Cancer. Cancer Res. 2016;76:1031–1043. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Filippi AR, Fava P, Badellino S, Astrua C, Ricardi U, Quaglino P. Radiotherapy and immune checkpoints inhibitors for advanced melanoma. Radiother Oncol. 2016;120(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sage EK, Schmid TE, Sedelmayr M, Gehrmann M, Geinitz H, Duma MN, Combs SE, Multhoff G. Comparative analysis of the effects of radiotherapy versus radiotherapy after adjuvant chemotherapy on the composition of lymphocyte subpopulations in breast cancer patients. Radiother Oncol. 2016;118(1):176–80. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2015.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.