Abstract

The shape and form of protozoan parasites are inextricably linked to their pathogenicity. The evolutionary pressure associated with establishing and maintaining an infection and transmission to vector or host has shaped parasite morphology. However, there is not a ‘one size fits all’ morphological solution to these different pressures, and parasites exhibit a range of different morphologies, reflecting the diversity of their complex life cycles. In this review, we will focus on the shape and form of Leishmania spp., a group of very successful protozoan parasites that cause a range of diseases from self-healing cutaneous leishmaniasis to visceral leishmaniasis, which is fatal if left untreated.

Keywords: morphology, Leishmania, pathogenicity, parasite

1. Shape and form of Leishmania

Like many protozoan parasites, Leishmania have a digenetic life cycle involving both a mammalian host and an insect vector. Leishmania parasites exhibit a variety of different cell morphologies and a number of cell types (developmental forms) that are adapted to either the host or the vector. As seen with other parasites such as Plasmodium and trypanosomes, some of these developmental forms are proliferative, whereas others are quiescent and pre-adapted for transmission to the next host [1–4]. Much of the interpretation of cellular form and function in Leishmania species is derived from the more studied basic cell biology of trypanosomes. While this is a natural transfer of knowledge, one has to remain vigilant to the fact that unrecognized differences may exist between the two pathogen systems, even in their basic biology.

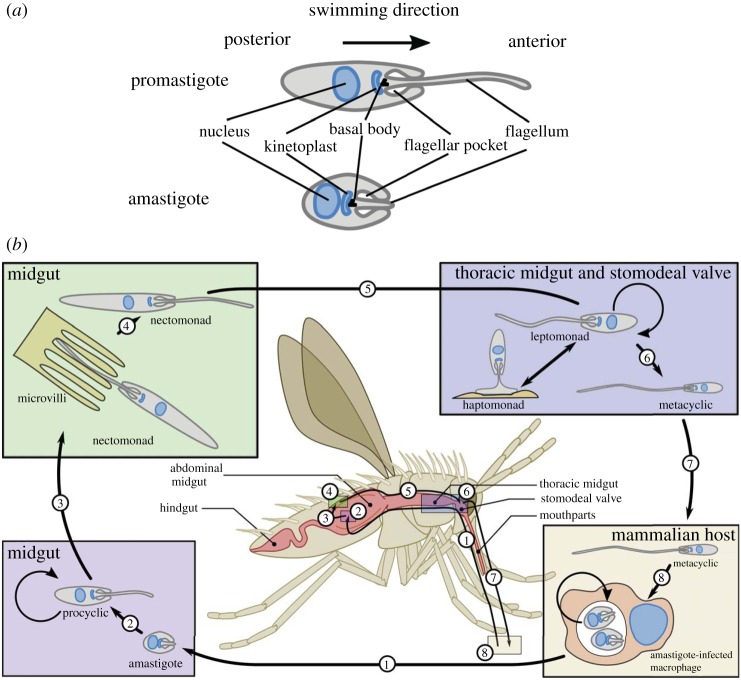

Leishmania have two major different cell morphologies, exemplified by the promastigote morphology in the sand fly and the amastigote morphology in the mammalian host (figure 1a). The basic cellular architecture is however conserved between the two Leishmania cell shapes and is defined by cross-linked sub-pellicular corset microtubules. This array is maintained throughout the cell cycle, so cell division relies on the insertion and elongation of microtubules into the existing array. Housed within the cell are the nucleus and a set of single-copy organelles such as the mitochondrion and the Golgi apparatus. Anterior of the nucleus is the kinetoplast, the mass of concatenated mitochondrial DNA which is directly connected to the basal body from which the flagellum extends [5–8]. At the base of the flagellum is an invagination of the cell membrane forming a vase-like structure called the flagellar pocket, which is important in these parasites as it is the only site of endocytosis and exocytosis and is hence a critical interface between the parasite and its host environment [9].

Figure 1.

Schematic of promastigote and amastigote morphologies and the Leishmania life cycle with the different cell types highlighted. (a) Promastigote and amastigote morphologies aligned along the posterior anterior axis with key structures in the cells indicated. (b) Cartoon of the current understanding of the Leishmania life cycle with critical events and different cell types highlighted. A sand fly takes a blood meal from an infected mammalian host and ingests a macrophage containing Leishmania amastigotes. Once in the sand fly midgut, the amastigotes differentiate into procyclic promastigotes. Next, the procyclic promastigotes become nectomonad promastigotes, which escape the peritrophic matrix and then attach to the microvilli in the midgut before moving to the thoracic midgut and stomodeal valve where they differentiate into leptomonad promastigotes. Here, the leptomonad promastigotes differentiate into either haptomonad promastigotes which attach to the stomodeal valve or metacyclic promastigotes that are the mammalian infective form, which are transmitted when the sand fly next takes a blood meal. Proliferative stages are indicated by a circular arrow.

In essence, the Leishmania cell is constructed from a series of modular units such as the flagellum, basal body–mitochondrial kinetoplast unit and a Golgi–flagellar pocket neck unit [8]. These modular units are then positioned relative to each other to give rise to the different cell morphologies observed [10,11]. The key to defining the dynamic shape and form of this parasite is therefore to understand the morphogenesis of these different individual modular units and their positioning relative to each other.

Cellular morphology of the Leishmania parasites is very precisely defined by cell shape, flagellum length, kinetoplast/nucleus position and ultrastructural features, and therefore has been traditionally used to define the cell forms observed. In some cases, though, these morphological descriptions of cell forms have entered the literature as defining specific cell types in the life cycle. However, there are currently few molecular markers to assist in defining life cycle forms more precisely and there is a need, therefore, for care and caution when defining cell types solely on the basis of cell morphology.

2. Defining diversity: different species, different diseases, different cells in the vector and host

Different species of Leishmania parasite cause disease in humans, with the different species often grouped together depending on whether they emerged in the old world or the new world (table 1) [12] and on the nature of the pathology (cutaneous, mucocutaneous or visceral leishmaniasis) [12,13]. It is important to remember that this is not just a disease of humans and that Leishmania will infect other mammals, creating a zoonotic reservoir that has serious implications for disease control [14]. The sand fly vector adds a further layer of complexity: there are many species capable of carrying the Leishmania parasite; however, there are often specific relationships whereby some sand fly species are capable of transmitting only a single or limited number of Leishmania species (table 1) [15].

Table 1.

The vector, disease and origin of a range of different Leishmania species. Adapted from Bates [12].

| species | sand fly vector | disease | old world or new world |

|---|---|---|---|

| L. major |

Phlebotomus duboscqi Phlebotomus papatasi Phlebotomus salehi |

cutaneous | old world |

| L. mexicana | Lutzomyia olmeca olmeca | cutaneous | new world |

| L. braziliensis |

Lutzomyia wellcomei Lutzomyia complexus Lutzomyia carrerai |

mucocutaneous | new world |

| L. donovani |

Phlebotomus argentipes Phlebotomus orientalis Phlebotomus martini |

visceral | old world |

| L. infantum |

Phlebotomus ariasi Phlebotomus perniciosus Lutzomyia longipalpis |

visceral | new and old world |

Despite all these levels of complexities and differences, the morphology of the different Leishmania species shows remarkable conservation of form as they progress through their life cycle. Cells with an amastigote or promastigote morphology look dramatically different, but they retain the same basic cell layout with the kinetoplast anterior to the nucleus and a flagellum extending from the basal body (figure 1a) [5,6]. An amastigote morphology is typified by a smaller and more spherical cell body with a short immotile flagellum that barely emerges from the flagellar pocket and is potentially more focused on sensory functions [16,17]. Conversely, the promastigote morphology is defined by an elongated ovoid cell body with a long motile flagellum extending out of the flagellar pocket that provides propulsive force likely responsible for facilitating the traverse through the sand fly digestive tract [18].

3. Promastigote to amastigote transition

When a Leishmania-infected sand fly takes a blood meal, metacyclic promastigotes are deposited into the site of the bite (figure 1b). The damage caused by the sand fly results in the recruitment of macrophages to the bite site, and these are the cells which Leishmania infects and resides in allowing them to persist in the host [19–21]; however, there is minimal evidence showing where the interaction between Leishmania and macrophages occurs in the host. Metacyclic promastigotes are highly motile cells, and Leishmania are able to migrate through a collagen matrix [22]. It is therefore possible that phagocytosis of Leishmania may occur at locations far removed from the bite site. Moreover, perhaps the spectrum of disease caused by Leishmania from cutaneous to visceral is reflected in the ability of the parasite to invade the host beyond the bite site either directly or via infected macrophage movement.

There are conflicting reports in the literature over the polarity of the interaction and uptake between Leishmania and the macrophage, with some suggesting it occurs via the flagellum first but others showing that it predominantly occurs via the cell body or from both ends [23–25]. Given the flagellum-first movement exhibited by these metacyclic promastigotes, the tip of the flagellum is likely to be the first part of the cell to interact with the macrophage. In the closely related parasite Trypanosoma brucei, the flagellum tip has a number of proteins including receptors that localize exclusively to this region [26,27]. There is therefore potential for a differentiated membrane domain at the flagellum tip to be primed for the collision with the macrophage, which would initiate a series of signalling events leading to the successful uptake and differentiation of the parasite. However, whichever orientation the Leishmania is engulfed in, the parasite ends up with its flagellum pointing towards the periphery of the macrophage [24,25]. The continued movement of the flagellum within the macrophage results in plasma membrane damage and lack of integrity, which promotes lysosomal exocytosis potentially altering the composition of the parasitophorous vacuole, thereby increasing the chances of the parasite successfully infecting the macrophage [25].

Once inside the macrophage, the promastigote differentiates from a motile promastigote form, which has a long flagellum and an elongated cell shape, to an amastigote form that has a short flagellum with only a small bulbous tip extending beyond a now more spherical cell body. This is a dramatic change in cell shape and results in a minimized cell surface to volume ratio, hence reducing the area over which the cell is exposed to the harsh environment of the parasitophorous vacuole, and also a likely reformatting of flagellum use [28–30].

The most striking difference between the amastigote and promastigote forms is the change in the flagellum from a long motile flagellum with a 9 + 2 axoneme to a short non-motile flagellum with a 9 + 0 (9v) axoneme arrangement [17]. Wheeler et al. [17] have studied this specific aspect of the differentiation process in detail, and have shown that this change in flagellum structure involves either (i) disassembly of the existing long flagellum and removal of its central pair, hence collapsing it down to a short 9v axoneme, or (ii) the assembly of a short new flagellum, lacking a central pair and exhibiting a 9v axoneme. The latter mechanism is interesting as the pro-basal body which assembled that 9v axoneme would have assembled a 9 + 2 axoneme if that cell had remained in promastigote culture, showing the ability of the pro-basal body to switch between constructions of either type of axoneme.

Given that there are examples of organisms that are able to completely lose and reform their flagellum during their life cycle, the continued presence of the flagellum in amastigotes suggests that it has an important function for the parasite within the macrophage [30–32]. The most commonly postulated function for this flagellum is a sensory role because the 9v axonemal architecture is structurally similar to that found in mammalian primary cilia and the tip of the flagellum in the Leishmania amastigote is often found in close contact with the parasitophorous vacuole membrane [16,33]. The Leishmania parasite, via its flagellum, could potentially sense the ‘health’ of its host macrophage by assessing key metabolites such as the adenosine nucleotides, for instance. If the macrophage is ‘healthy’, the parasite may divide, but if the macrophage is ‘unhealthy’, the parasite may decide not to divide as the macrophage may be about to die and lyse, thereby releasing the parasite into a new environment. Specific checkpoints are therefore likely to exist and be applied in the Leishmania cell cycle at the G1 to G0/S boundaries. Moreover, the release of the parasite is unlikely to be a ‘passive’ process but instead be driven by the parasite itself. This is an area of interest and importance where the specific cell biology of a possible parasite cell-cycle-related release has not been addressed.

In addition to the dramatic change in the flagellum structure during differentiation into the amastigote form, there is also a large restructuring of the flagellar pocket and neck region that is associated with changes in the localization of the flagellum attachment zone proteins [7]. A surprising consequence of this rearrangement is the closing of the flagellar pocket neck so that there is no observable gap between the flagellum and flagellar pocket neck membrane [7]. The dogma for the flagellar pocket in this and related parasites is that it is the only site of exocytosis and endocytosis in the cell and hence is a major interface between the parasite and its hosts. However, if the flagellar pocket is closed off at the neck, how will this affect this important interface? Is this closure dynamic and more akin to a valve-like operation? Does the limited access to the flagellar pocket reduce the ability of the parasite to take up macromolecules from its surroundings? The growth rate of axenic amastigotes has been measured by heavy water labelling and was shown to be much slower than that of promastigotes [34], and in addition amastigotes have a much smaller cell volume than promastigotes, resulting in a concomitantly smaller metabolic load. Taken together, the slow growth rate and smaller metabolic load may reflect a reduced rate of macromolecule uptake into the cell. However, the slow growth rate might be the result of an evolutionary pressure not to overwhelm the host's immune system, thereby allowing the host to survive for longer, the parasite to proliferate for longer and so increasing the chance of parasite transmission to a sand fly.

The closing of the flagellar pocket neck is also likely to be a consequence of protecting a potentially vulnerable domain of the cell from the environment within the parasitophorous vacuole, which is acidic and full of proteases [28,29]. The reduced access to the flagellar pocket due to the reduction in the space between the neck and flagellum membranes in the amastigotes is the probable explanation for lytic high-density lipoprotein containing trypanolytic factor being unable to lyse amastigotes in the acidic parasitophorous vacuole, yet being able to kill metacyclic promastigotes, which have a more accessible flagellar pocket [35]. It will be interesting to compare the morphology of the Leishmania amastigote flagellar pocket with that of the intracellular amastigote of the closely related organism Trypanosoma cruzi, as this parasite escapes from the parasitophorous vacuole and proliferates in a completely different environment, the cytoplasm of its host cell [36].

There are two distinct types of parasitophorous vacuoles that develop in the infected macrophages, which correlate with the species of Leishmania. Infection with some species such as L. amazonensis produces large multiple-occupancy parasitophorous vacuoles (type II vacuoles) that contain multiple amastigotes, whereas other species such as Leishmania major produce small, tight-fitting, single-occupancy parasitophorous vacuoles (type I vacuoles) that surround a single amastigote parasite [37,38]. Co-infections with L. amazonensis and L. major in a single macrophage showed that fusion of the two types of parasitophorous vacuole, either large containing L. amazonensis amastigotes or small containing a L. major amastigote, did not occur. This suggests that the parasitophorous vacuole is modified to the specific requirements of each species, precluding successful fusion of the different parasitophorous vacuole types [37].

Interestingly, despite the differences observed in parasitophorous vacuole types, the cellular organization and layout of the amastigotes of different species are well conserved [39]. However, there are some observable differences between amastigotes of different species, with L. mexicana amastigotes being around 50% larger in mean diameter than those of L. braziliensis and L. donovani [40]. This size difference may have implications on the pathology caused by the different Leishmania species, but there is no simple relationship between this or other features to pathology type. Indeed, as another example, ultrastructural studies on the amastigotes of L. tropica and L. donovani have revealed a distinct posterior invagination termed a ‘cup’ or ‘posterior invagination’ [41,42]. The authors suggested that this may be an alternative site of exo/endocytosis in these cells. To the best of our knowledge, this structure has not been found in any other species of Leishmania amastigotes. As L. tropica causes cutaneous leishmaniasis and L. donovani causes visceral leishmaniasis, this morphological adaptation again appears not to be linked to the disease pathology. On balance, therefore, while differences between promastigote and amastigote are likely very significant to the host/vector relationships, the overall similarity in amastigote morphology between the different species suggests that no simple link between morphology and disease pathology exists. Instead, either subtler features or the possession and expression of various potential virulence factors produced by the different species, such as the A2 protein, may have a greater import for the spectrum of disease [43,44].

A distributed skin population of Leishmania-infected macrophages has recently been observed by Doehl et al. [45]. This distributed, circulating population of infected macrophages will help to ensure efficient transmission of Leishmania parasites from the host to the sand fly as a splenic infection is not accessible to sand flies and sand flies are unlikely to bite exclusively at the actual lesion site in a localized cutaneous infection. Moreover, these infected macrophages may contain a potentially different form of Leishmania amastigote that is primed to survive in the sand fly midgut when taken up in the blood meal, mirroring the transmissibility of the metacyclic promastigote cell type in the sand fly or the stumpy form of the African trypanosomes [12,30,46].

4. Amastigote to promastigote transition

After ingestion by the sand fly and release from the macrophage, the amastigote begins to differentiate into a motile promastigote form. The exact cues for differentiation have yet to be established but are likely to be a combination of the change in temperature and pH akin to other parasites and as seen for Leishmania as it differentiates from a promastigote to an amastigote in the parasitophorous vacuole [47]. However, there may also be a requirement for the presence of a specific chemical trigger to ensure that differentiation occurs only in the vector and not in the host; for example, Plasmodium requires xanthurenic acid, a mosquito eye pigment precursor, to differentiate [48]. Temperature alone is unlikely to be the sole trigger for differentiation, as the macrophage will experience a range of temperatures as it circulates through the body, but it may act to sensitize the amastigote to the other differentiation cues as found with T. brucei [49].

The in vitro differentiation of L. amazonensis amastigotes into promastigotes has been studied in detail by microscopy [50]. The first visible step in this process is the elongation of a motile flagellum, which occurs before cell division, and after this first cell division both daughter cells had a motile flagellum [50]. On maturation, the pro-basal body in the parental cell was therefore able to assemble a 9 + 2 motile axoneme, yet if this same cell had remained in the macrophage the same pro-basal body would have assembled a 9v axoneme, again demonstrating the multipotency of the pro-basal body in Leishmania [17]. These results are complementary with those of Wheeler et al. [17] and show that pro-basal bodies are able to assemble either a 9 + 2 or a 9v axoneme independently of whichever axoneme type the mother basal body had produced [17,50].

During differentiation into a promastigote form, the cell shape also begins to change from the spherical amastigote to a more elongated ovoid shape. In concert with the changes that occur to the overall shape of the cell body, the organization of the flagellum attachment zone and flagellar pocket changes. Specifically, the neck region of the flagellar pocket becomes more open, reflecting a reversal of the process that occurred during differentiation into the amastigote form [7]. This opening of the neck may allow easier access to the flagellar pocket, enabling the uptake of large macromolecules and also potentially affecting the motility of the parasite.

5. Roles of the Leishmania flagellum in the sand fly

The flagellum has multiple potential roles in enabling the Leishmania parasites to successfully establish and maintain an infection in the sand fly. There are three potential key functions for the flagellum in the sand fly, which we discuss in the following sections:

(i) motility to escape the peritrophic matrix and migrate to the foregut,

(ii) attachment to the midgut microvilli and stomodeal valve, and

(iii) potential sensory functions.

5.1. Motility

The ingestion of a blood meal by a sand fly causes numerous changes to the sand fly, including the creation of a peritrophic matrix from chitin and glycoproteins that encases the blood meal separating it from the midgut epithelium. After approximately 4 days, the remaining undigested blood meal and surrounding peritrophic matrix are defecated out by the sand fly [51,52]. The Leishmania promastigotes therefore need to escape from the peritrophic matrix before defecation occurs. Moreover, for successful transmission to a mammalian host, the Leishmania parasites need to colonize the stomodeal valve region of the sand fly and so migrate from the midgut towards the mouthparts; active flagellar motility presumably assists in both these processes.

5.2. Attachment

The loss of peritrophic matrix integrity allows the Leishmania parasites to escape the endotrophic space [53]; these cells then attach to the epithelium of the midgut by inserting their flagella between the microvilli, which helps prevent the parasites being expelled from the sand fly during defecation. This attachment is not accompanied by any observable morphological changes to the Leishmania cell [54]. Evidence suggests that attachment is mediated through specific glycoprotein–lectin interactions, providing a potential mechanism by which the vector–parasite specificity is determined. The surface coat component lipophosphoglycan (LPG) was believed to be crucial for this interaction as L. major cells deficient in LPG synthesis were unable to attach to the sand flies Phlebotomus papatasi and P. duboscqi [55,56]. However, recent work has shown that this L. major mutant is able to successfully infect other sand fly species such as P. arabicus, P. argentipes, P. perniciosus and Lutzomyia longipalpis, and moreover a L. mexicana mutant that is unable to synthesize LPG is also able to fully develop within Lutzomyia longipalpis [56–58]. Clearly, LPG is important for interactions between some Leishmania species and sand fly species, but it is not the universal determinant of these interactions.

The second site of Leishmania attachment in the sand fly is at the stomodeal valve, where a specialized cell type called the haptomonad is observed attached to the cuticle lining of the valve by hemidesmosomal structures that are found in the enlarged tip of a relatively short flagellum [54]. These hemidesmosomal structures are reminiscent of those observed for the attached epimastigote forms of trypanosomes, and it is likely that attachment to the insect vector via such structures will be a universal feature of kinetoplastids [59,60]. Currently, the biochemical identity of these structures is cryptic, but given their importance in many kinetoplastid species the discovery of the molecular components will be of great interest [60]. The strong attachment presumably stops the Leishmania haptomonad cell type being passed to the mammalian host when the sand fly feeds and may therefore have a role in maintaining a long-term infection in the sand fly and/or asymmetric divisions [61].

5.3. Sensory

After escaping the peritrophic matrix, the parasites then migrate forward through the sand fly to colonize the thoracic midgut. Successful colonization and transmission of Leishmania are dependent on the sand fly taking a sugar meal after the blood meal, and it is an enticing hypothesis that the Leishmania are able to navigate the sugar gradient along the gut to enable colonization of the sand fly foregut. The molecular components required for chemotaxis are present in Leishmania with carbohydrate receptors found on the cell surface and a flagellum capable of performing different beat structures, which enable the cell to move forward and re-orientate itself. Furthermore, in vitro experiments have shown that Leishmania are able to respond to a change in sugar concentration [62–64].

Table 2 outlines publications in which morphology and/or motility have/has been altered by mutational analysis in Leishmania species [18,65–78]. Clearly, some morphology mutants will have catastrophic effects on cell division and as such are not that useful for assessing links to pathogenicity and development. Comparison with work in T. brucei shows that subtle RNAi knockdowns (available now as a technology in L. braziliensis) can provide dramatic changes in cell architecture [11,79,80]. One lesson from this is that subtle differences in expression rather than absence or presence in genomes might influence virulence or pathology. The current improvements in both reverse and forward genetics in Leishmania will be very helpful in this area [81–84]. We have outlined above three functions of the Leishmania flagellum in the sand fly, but what is the actual evidence that the flagellum is required in sand flies? From table 2, we can see that there are many mutants where the function/length of the Leishmania flagellum has been compromised, such as through the overexpression of KIN13-2 or the loss of PFR2, but very few studies have infected sand flies with these mutants [18,65,72].

Table 2.

Summary of morphological and/or motility mutants in Leishmania.

| protein | gene ID | phenotype | conserved across Leishmania species on TriTrypDBv33 | development in sand flies | pathogenicity in macrophages | pathogenicity in animals | reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFR2 | LmjF.16.1425/1427/1430 | PFR-2 knockout cells had an altered flagellar beat with a reduced swimming velocity | yes | not done | not done | not done | [65] |

| PFR1 | LmjF.29.1750/1760/1770 | both PFR1 knockout cells and PFR1/2 double knockout cells had an altered flagellar beat with a reduced swimming velocity | yes | not done | not done | not done | [66] |

| ARL-3A | LdBPK_290950.1 | cells overexpressing a constitutively ‘active’ form of ARL-3A were immotile with short flagella, and flagellum length was inversely proportional to mutant protein expression | yes | unable to develop in sand flies | no change in macrophage infectivity | not done | [18,67] |

| MKK | LmxM.08_29.2320 | MKK knockout cells had motile flagella, which was dramatically shorter and lacked a paraflagellar rod and also had shorter cell bodies | yes | not done | not done | not done | [68] |

| MPK9 | LmxM.19.0180 | MPK9 knockout cells had longer flagella, whereas overexpression led to a subpopulation with short/no flagella | yes | not done | not done | not done | [69] |

| DHC2.2 | LmxM.27.1750 | DHC2.2 knockout cells were immotile and had a rounded cell body. The flagellum did not extend beyond the cell body and lacked a paraflagellar rod and other axonemal structures | yes | not done | not done | not done | [70] |

| MPK3 | LmxM.10.0490 | MPK3 knockout cells had shorter flagella with stumpy cell bodies | yes | not done | not done | not done | [71] |

| KIN13-2 | LmjF.13.0130 | KIN13-2 knockout cells had longer flagella, whereas overexpression led to shorter flagella | yes | not done | not done | not done | [72] |

| ADF/cofilin | LdBPK_290520.1 | ADF/cofilin (actin-depolymerizing factor) knockout cells were immotile with shorter flagella and a disrupted beat pattern. The cells were also shorter and wider | yes | not done | not done | not done | [73] |

| katanin | LmjF13.0960 | cells overexpressing katanin-like homologue had shorter flagella | yes | not done | not done | not done | [74] |

| SMP1 | LmjF.20.1310 | loss of SMP1 caused a reduction in flagellum length and defects in motility | yes | not done | not done | not done | [75] |

| DC2 | LdBPK_323050.1 | DC2 knockout cells had shorter flagella with a disrupted ultrastructure and reduced motility. Moreover, the cell bodies were shorter and rounder. | yes | not done | slight increase in macrophage infectivity | not done | [76] |

| inhibitor of serine peptidase 1 (ISP1) | LmjF.15.0300 | ISP1/2/3 triple knockout cells had longer flagella and were less motile than ISP2/3 double knockout cells. Moreover, the triple knockout had a greater number of cells with haptomonad, nectomonad and leptomonad morphologies. There was also a change in the shape of the anterior end of these cells | yes | not done | reduced survival in macrophages | not done | [77] |

Overexpression of an LdARL-3A mutant in L. amazonesis resulted in cells that were unable to assemble a full-length flagellum and that had impaired motility [67]. When these cells were used to infect sand flies, these mutants were unable to establish an infection, likely due to their defective motility [18]. Moreover, the length of the flagellum may also be playing a role: a shorter flagellum will be less effective at intercalating between the microvilli in the midgut, giving a smaller surface area with which to interact, reducing the strength of binding and increasing the likelihood of expulsion during defecation. However, recently, a L. braziliensis mutant was isolated from a patient lesion, which was unable to assemble a full-length flagellum when grown under promastigote culture conditions in vitro [85]. The flagellum in the mutant cells only just emerged from the flagellar pocket, and surprisingly these mutants successfully infected sand flies, though the infections were analysed only up to 4 days after feeding, so the ability of this mutant to maintain an infection over the longer term is unknown. The exact role(s) of the Leishmania flagellum within the sand fly has yet to be fully elucidated, and it would therefore be useful to analyse the potential of a range of flagellum mutants of Leishmania to establish and maintain an infection in sand flies.

6. Promastigote transitions

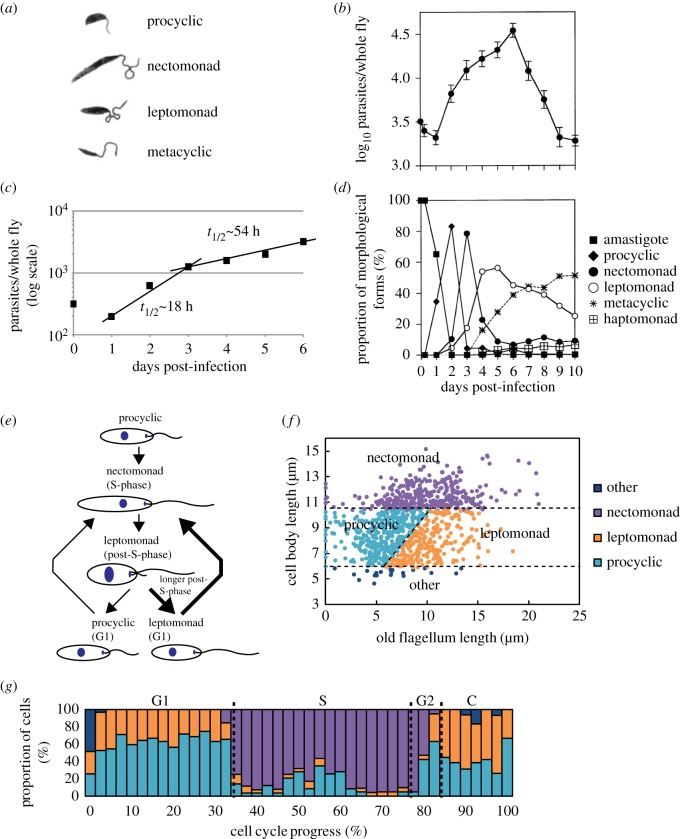

In addition to the overarching promastigote and amastigote morphologies in the sand fly vector and mammalian host, respectively, there are variations of promastigote morphologies found such as the procyclic and metacyclic promastigotes in the sand fly. The reported shape of these different forms can be extreme, and this has led to them being defined as different cell types (developmental forms) rather than just different transition morphologies. Currently, there are four major cell types identified in the sand fly based on the length/width of the cell body and flagellum [86] (figure 2a):

(i) procyclic promastigote: cell body length between 6.5 and 11.5 µm with the flagellum shorter than cell body,

(ii) nectomonad promastigote: cell body longer than 12 µm,

(iii) leptomonad promastigote: cell body length between 6.5 and 11.5 µm with the flagellum longer than cell body, and

(iv) metacyclic promastigote: cell body less than 8 µm long and 1 µm wide with a flagellum longer than the cell body.

Figure 2.

Development of Leishmania in the sand fly digestive tract. (a) Illustrations of the major promastigote morphologies observed in the sand fly during a Leishmania infection. (b) Leishmania cell number per sand fly during a typical sand fly infection over the course of 10 days. (c) Cell density from (b) was re-plotted and the doubling times calculated for the early and late infection stages. (d) Analysis of the proportions of different cell types observed during a sand fly infection. (a), (b) and (d) are reproduced with permission from Rogers et al. [86]. (e) Schematic of Leishmania cell cycle with the corresponding cell types shown above. (f) Correlation of flagellum and cell body length from three independent L. mexicana in vitro cultures analysed at different cell densities. The data were then subsequently classified into the different promastigote morphologies [86]. (g) Proportion of cells with different promastigote morphology by cell cycle progress. The cell cycle progress of the cells used in the analysis for (f) was calculated based on their cell length and DNA content and then combined with the promastigote morphology classification from (f) [87,88]. Dotted lines indicate transitions between cell cycle stages (C, cytokinesis). (e) and (f) are reproduced with permission from Wheeler [89].

These four cell types are thought to represent a developmental sequence with specific precursor–product relationships between them (figure 1b). Briefly, the procyclic promastigote occurs within the blood meal; the nectomonad promastigote is observed as the peritrophic matrix breaks down and moves towards the foregut where it becomes the leptomonad promastigote before differentiating into either an infective metacyclic or a haptomonad promastigote [86,90]. In addition to these four major forms, the attached haptomonad promastigote and the paramastigote are also observed in the sand fly but at a much lower frequency [86]. All these forms have the same basic promastigote cell architecture with the kinetoplast (mitochondrial DNA) anterior to the nucleus and the flagellum extending from the anterior end of the cell with a shallow flagellar pocket, apart from the paramastigote, in which the kinetoplast is positioned next to the nucleus.

The numbers and timings of the various different promastigote cell types in sand flies have been studied by Rogers et al. [86] (figure 2a–d). In their experimental system, they calculated that each sand fly could ingest approximately 3200 amastigotes in a 1.6-µl bloodmeal. After ingestion, there was an initial drop of parasites over the first day to approximately 2500 and then the population grew over the next 5 days and peaked at approximately 35 000 parasites per fly, which means that approximately four doublings of the parasite population occurred (figure 2b). Initially, the growth of the cells was relatively quick with a doubling time of approximately 18 h in the period from 1 to 3 days post-infection. The growth rate then slowed and the doubling time dropped to approximately 54 h from days 3 to 6 (figure 2c). After day 6 there was a rapid decrease in the number of parasites present, with only a few thousand left by day 10. The reasons for the dramatic fall in parasite number are not known, but it may be due to the exhaustion of nutrient supplies or an immune response by the sand fly.

At each day post-infection, Rogers et al. analysed the different promastigote cell types present in the sand fly and showed that the growth and division of Leishmania appears initially relatively synchronous as clear successive peaks of different promastigote cell types are observed (figure 2d) [86]. Over the first 2 days of infection, in addition to a large increase in overall parasite numbers there was a rapid drop in the proportion of amastigotes with a concomitant increase in the proportion of procyclic promastigotes observed. Taken together, this means that the differentiation of amastigote into procyclic promastigote includes both direct cell differentiation and division-directed differentiation matching the in vitro differentiation [50]. After the procyclic promastigote peak, there is a peak of nectomonad promastigotes followed by leptomonad promastigotes, which then drops in proportion as the quiescent metacyclic promastigotes begin to dominate the infection.

The other consistently observed cell types of Leishmania in the sand fly are the attached haptomonad promastigote and the paramastigote. Where these forms have been quantified, the paramastigote was rarely seen and did not account for more than 2% of cells observed [86]. A possibility exists that it could be an aberrant division product, where the kinetoplast has ended up next to the nucleus. The position in the developmental cycle of the attached haptomonad promastigote, which is observed at low numbers and occurs in the later stages of the infection, is unclear, with it potentially deriving from a leptomonad promastigote (figure 1b) [86]. This cell type is rarely seen in division, which suggests that the attachment to the cuticle may be reversible and a cell may stochastically attach and detach or that it divides very slowly.

The synchrony of the appearance of the different promastigote cell types identified by Rogers et al. in the sand fly is intriguing as in vitro synchronized cell cultures rapidly lose their synchronicity, yet here it is retained for approximately four cell doublings (figure 2d). It is possible that the synchrony of cell division is set by the entry into proliferation as the amastigotes begin to differentiate and divide, but perhaps, there are other elements involved such as environmental conditions. The rapid proliferation of Leishmania parasites in the sand fly has a large effect on the nutrient levels. Might the change in nutrients create the synchrony of the different cell types observed? This would be reminiscent of diauxic growth observed in bacteria where if both glucose and galactose are present the bacteria preferentially metabolize the glucose. Once that is exhausted they switch to lactose, but this switch is accompanied by a pause in cell growth as the metabolism of the cell is reprogrammed [91,92]. Recent transcriptomic data from Inbar et al. [93] show that there is a drop in the level of mRNA of glucose-metabolism-related genes with an increase in the level of mRNA of amino acid transporter genes as the parasite switches from a procyclic promastigote to a nectomonad promastigote cell type.

7. Life cycle and cell cycle

An added complication to the analysis of the different promastigote cell types comes from the recent work on the morphological changes observed during the cell cycle of in vitro cultured promastigotes [87,94]. This has demonstrated that as a promastigote proceeds through the cell cycle it undergoes a doubling and then halving of its cell length. In addition, unlike for many other organisms, the two daughter cells produced by Leishmania promastigote cell division are different. One daughter will inherit the old and therefore longer flagellum and the other will inherit the new and therefore shorter flagellum, so promastigote cell division can generate two daughter cells with dramatically different flagellum lengths (figure 2e). If the morphological definition of procyclic, nectomonad and leptomonad promastigote cell types as defined by Rogers et al. is applied to the cells observed in culture, all three cell types are found (figure 2f,g) [86,89].

— A nectomonad promastigote looks similar to a cell in S-phase.

— A procyclic promastigote looks similar to a cell either in G1 or post-S-phase that inherited the new, short flagellum.

— A leptomonad promastigote looks similar to a cell in the same cell cycle stages as a procyclic promastigote but which inherited the old, longer flagellum.

This highlights the problems of using morphological parameters to define cell types as the two daughter cells of an in vitro promastigote division can be differentially classified as either a procyclic or a leptomonad cell type. It therefore also emphasizes the need for independent cell markers for the different life cycle cell types.

It is possible that the proportion of cells produced after division with a morphology that would define them as either a procyclic or a leptomonad cell type is influenced by the time the parental cell spends in G2, as this is the time during which the elongation of both the old and new flagella occurs (figure 2e). For example, if a cell spends sufficiently long in G2, then the subsequent division would generate two leptomonad cell types (figure 2e). Through manipulation of the length of G2, it is therefore conceivable that a growing population of Leishmania promastigotes could become dominated by leptomonad cell types as is seen in the sand fly. Moreover, the nectomonad cell type was defined as a non-dividing stage as it was never observed to have either two kinetoplasts or two nuclei [90]. Interestingly, the promastigote cells observed in culture with a morphology that would define them as a nectomonad promastigote are predominantly in S-phase and so would have only one kinetoplast and nucleus (figure 2g) [89].

Life cycle development is regarded as a one-way street, and so as a parasite goes through each step it commits to differentiating into the next life cycle stage without being able to revert the previous stage. This means that there will be significant differences between parasites at different stages of the life cycle including changes to metabolism, cell-surface protein expression and also cell shape. One has to be careful with the latter, however, as these characteristics are prone to change for other reasons such as cell cycle position and metabolic state. It is therefore best to define whether a parasite has become a different cell type based on molecular markers. The recent transcriptomic analysis of Leishmania cells in the sand fly should help to clarify the current situation [93].

8. Discussion

Protozoan parasites have distinctive phases of population proliferation and differentiation associated with different proliferative cell types and transmission cell types. In turn, these are associated with movement between different ecological niches in the parasite's life cycle. A general feature of transmission stages is that they are no longer proliferative, and are irreversibly differentiated and are able to proliferate again only when they have successfully moved to the next environmental site in their life cycle. For example, in Plasmodium, the merozoite is the proliferative cell type in the erythrocyte and the gametocyte is the cell type that establishes the infection in the mosquito. As the differentiation into a transmission form is irreversible, this process has to be tightly regulated and will therefore be influenced by the parasite's host environment [1]. Hence, parasites need to closely monitor their environment so that they can respond in the most appropriate manner, which could be either continued proliferation or a switch to a differentiation programme to prepare for transmission.

Furthermore, the decision point for differentiation must be integrated into and coordinated with the cell cycle. This implies that there is a cell-cycle-based checkpoint at which a cell must decide either to divide or to differentiate into the next developmental stage, and this decision will be based on the integration of parasite internal and external cues [1]. For Giardia encystation to occur, the cells need to undergo a round of DNA replication before differentiation can occur, suggesting that for this organism the decision point is during G2 [95]. Currently, identifying these development cues is an area of active research as disruption of this process has great therapeutic potential either by causing premature differentiation or by blocking the process entirely [46].

Eukaryotic parasites have evolved a dazzling array of different morphologies that are likely to be adapted to various different ecological niches. The kinetoplastid parasites are an ideal set of organisms to study and hence understand the role of cell shape and form in enabling transmission between host and vector, and also the establishment and maintenance of infection. The closely related parasites Leishmania spp., T. brucei and T. cruzi have each adapted to a different niche within the host and have a different vector and a different set of morphologies into which they differentiate through their life cycles. High-quality genomes are available for all three species, and comparative genomics has identified sets of genes that are unique to each of these organisms or shared between only two of them; these are likely to be involved in certain processes such as adaptations to an intracellular or extracellular lifestyle in the host [96–98].

An interesting observation highlighted by comparing Leishmania with T. brucei is that the different developmental forms of T. brucei observed in the tsetse fly are generated through asymmetrical divisions, which produce two different daughter cells that are dramatically different in size or have a different kinetoplast nucleus arrangement [99,100]. However, during Leishmania development in the sand fly, no asymmetric divisions have been reported. Have these been missed or are the different forms observed in the sand fly potentially generated through a different mechanism? During the cell cycle, a Leishmania cell will undergo a doubling and then halving of its cell length [87], demonstrating that an individual Leishmania cell has a different plasticity in cell shape and form than a trypanosome. Therefore, the different Leishmania forms observed in the sand fly can be generated by the modulation of the shape of an individual cell, whereas the changes that occur in trypanosome cell shape in the tsetse fly may rely on asymmetric division to generate different cell shapes.

The understanding of the biology behind the ability of Leishmania parasites to subvert their hosts is of great interest and a medical imperative. The parasite has specific cell types and morphologies that are clearly linked to pathogen niches, but we need to interpret these in a modern cell biological context. There is now an opportunity to revisit the textbook descriptions of shape, form and cell types using new tools and techniques. At times, we lack stringent evidence to underpin the conclusions that are generally accepted. An absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. Molecular parasitology is moving from a twentieth-century parasitology textbook description of these parasites to a modern twenty-first-century cell biology understanding of the cellular mechanisms that enable them to survive and thrive.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank members of the Gull laboratory both past and present for fruitful discussions. The authors thank Richard Wheeler for help with the cartoons and for critical reading of the manuscript.

Data accessibility

This article has no additional data.

Authors' contributions

J.S. and K.G. conceived the review and wrote the manuscript, and have approved the final version.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Funding

The Wellcome Trust supports work in the Gull laboratory (WT066839MA, 104627/Z/14/Z, 108445/Z/15/Z).

References

- 1.Matthews KR. 2011. Controlling and coordinating development in vector-transmitted parasites. Science 331, 1149–1153. (doi:10.1126/science.1198077) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bates PA. 1994. Complete developmental cycle of Leishmania mexicana in axenic culture. Parasitology 108, 1–9. (doi:10.1017/S0031182000078458) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shapiro SZ, Naessens J, Liesegang B, Moloo SK, Magondu J. 1984. Analysis by flow cytometry of DNA synthesis during the life cycle of African trypanosomes. Acta Trop. 41, 313–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sinden RE, Canning EU, Bray RS, Smalley ME. 1978. Gametocyte and gamete development in Plasmodium falciparum. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 201, 375–399. (doi:10.1098/rspb.1978.0051) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aleman C. 1969. Finestructure of cultured Leishmania brasiliensis. Exp. Parasitol. 24, 259–264. (doi:10.1016/0014-4894(69)90163-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudzinska MA, D'alesandro PA, Trager W. 1964. The fine structure of Leishmania donovani and the role of the kinetoplast in the Leishmania-Leptomonad transformation. J. Protozool. 11, 166–191. (doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.1964.tb01739.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wheeler RJ, Sunter JD, Gull K. 2016. Flagellar pocket restructuring through the Leishmania life cycle involves a discrete flagellum attachment zone. J. Cell Sci. 129, 854–867. (doi:10.1242/jcs.183152) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogbadoyi EO, Robinson DR, Gull K. 2003. A high-order trans-membrane structural linkage is responsible for mitochondrial genome positioning and segregation by flagellar basal bodies in trypanosomes. Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 1769–1779. (doi:10.1091/mbc.E02-08-0525) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lacomble S, Vaughan S, Gadelha C, Morphew MK, Shaw MK, McIntosh JR, Gull K. 2009. Three-dimensional cellular architecture of the flagellar pocket and associated cytoskeleton in trypanosomes revealed by electron microscope tomography. J. Cell Sci. 122, 1081–1090. (doi:10.1242/jcs.045740) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sunter JD, Gull K. 2016. The flagellum attachment zone: ‘the cellular ruler’ of trypanosome morphology. Trends Parasitol. 32, 309–324. (doi:10.1016/j.pt.2015.12.010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayes P, Varga V, Olego-Fernandez S, Sunter J, Ginger ML, Gull K. 2014. Modulation of a cytoskeletal calpain-like protein induces major transitions in trypanosome morphology. J. Cell Biol. 206, 377–384. (doi:10.1083/jcb.201312067) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bates PA. 2007. Transmission of Leishmania metacyclic promastigotes by phlebotomine sand flies. Int. J. Parasitol. 37, 1097–1106. (doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.04.003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herwaldt BL. 1999. Leishmaniasis. Lancet 354, 1191–1199. (doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10178-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McMahon-Pratt D, Alexander J. 2004. Does the Leishmania major paradigm of pathogenesis and protection hold for new world cutaneous leishmaniases or the visceral disease? Immunol. Rev. 201, 206–224. (doi:10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00190.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dostálová A, Volf P. 2012. Leishmania development in sand flies: parasite–vector interactions overview. Parasit. Vectors 5, 276 (doi:10.1186/1756-3305-5-276) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gluenz E, Höög JL, Smith AE, Dawe HR, Shaw MK, Gull K. 2010. Beyond 9 + 0: noncanonical axoneme structures characterize sensory cilia from protists to humans. FASEB J. 24, 3117–3121. (doi:10.1096/fj.09-151381) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wheeler RJ, Gluenz E, Gull K. 2015. Basal body multipotency and axonemal remodelling are two pathways to a 9 + 0 flagellum. Nat. Commun. 6, 8964 (doi:10.1038/ncomms9964) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cuvillier A, Miranda JC, Ambit A, Barral A, Merlin G. 2003. Abortive infection of Lutzomyia longipalpis insect vectors by aflagellated LdARL-3A-Q70 L overexpressing Leishmania amazonensis parasites. Cell. Microbiol. 5, 717–728. (doi:10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00316.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Almeida MC, Vilhena V, Barral A, Barral-Netto M. 2003. Leishmanial infection: analysis of its first steps. A review. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 98, 861–870. (doi:10.1590/S0074-02762003000700001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arango Duque G, Descoteaux A. 2015. Leishmania survival in the macrophage: where the ends justify the means. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 26, 32–40. (doi:10.1016/j.mib.2015.04.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Menezes JP, Saraiva EM, da Rocha-Azevedo B. 2016. The site of the bite: Leishmania interaction with macrophages, neutrophils and the extracellular matrix in the dermis. Parasit. Vectors 9, 264 (doi:10.1186/s13071-016-1540-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petropolis DB, Rodrigues JCF, Viana NB, Pontes B, Pereira CFA, Silva-Filho FC. 2014. Leishmania amazonensis promastigotes in 3D collagen I culture: an in vitro physiological environment for the study of extracellular matrix and host cell interactions. PeerJ 2, e317 (doi:10.7717/peerj.317) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rittig MG, Schröppel K, Seack KH, Sander U, N'Diaye EN, Maridonneau-Parini I, Solbach W, Bogdan C. 1998. Coiling phagocytosis of trypanosomatids and fungal cells. Infect. Immun. 66, 4331–4339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Courret N, Fréhel C, Gouhier N, Pouchelet M, Prina E, Roux P, Antoine J-C. 2002. Biogenesis of Leishmania-harbouring parasitophorous vacuoles following phagocytosis of the metacyclic promastigote or amastigote stages of the parasites. J. Cell Sci. 115, 2303–2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forestier C-L, Machu C, Loussert C, Pescher P, Späth GF. 2011. Imaging host cell–Leishmania interaction dynamics implicates parasite motility, lysosome recruitment, and host cell wounding in the infection process. Cell Host Microbe 9, 319–330. (doi:10.1016/j.chom.2011.03.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saada EA, et al. 2014. Insect stage-specific receptor adenylate cyclases are localized to distinct subdomains of the Trypanosoma brucei flagellar membrane. Eukaryot. Cell 13, 1064–1076. (doi:10.1128/EC.00019-14) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Varga V, Moreira-Leite F, Portman N, Gull K. 2017. Protein diversity in discrete structures at the distal tip of the trypanosome flagellum. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, E6546–E6555. (doi:10.1073/pnas.1703553114) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Antoine JC, Prina E, Jouanne C, Bongrand P. 1990. Parasitophorous vacuoles of Leishmania amazonensis infected macrophages maintain an acidic pH. Infect. Immun. 58, 779–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Antoine JC, Prina E, Lang T, Courret N. 1998. The biogenesis and properties of the parasitophorous vacuoles that harbour Leishmania in murine macrophages. Trends Microbiol. 6, 392–401. (doi:10.1016/S0966-842X(98)01324-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gull K. 2009. The parasite point of view: insights and questions on the cell biology of Trypanosoma and Leishmania parasite–phagocyte interactions. In Phagocyte–pathogen interactions (eds Russell D, Gordon S), pp. 453–462. Washington, DC: ASM Press. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glyn M, Gull K. 1990. Flagellum retraction and axoneme depolymerisation during the transformation of flagellates to amoebae in Physarum. Protoplasma 158, 130–141. (doi:10.1007/BF01323125) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim H-K, Kang J-G, Yumura S, Walsh CJ, Cho JW, Lee J. 2005. De novo formation of basal bodies in Naegleria gruberi: regulation by phosphorylation. J. Cell Biol. 169, 719–724. (doi:10.1083/jcb.200410052) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gluenz E, Ginger ML, McKean PG. 2010. Flagellum assembly and function during the Leishmania life cycle. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 13, 473–479. (doi:10.1016/j.mib.2010.05.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kloehn J, Saunders EC, O'Callaghan S, Dagley MJ, McConville MJ. 2015. Characterization of metabolically quiescent Leishmania parasites in murine lesions using heavy water labeling. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1004683 (doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004683) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Samanovic M, Molina-Portela MP, Chessler A-DC, Burleigh BA, Raper J. 2009. Trypanosome lytic factor, an antimicrobial high-density lipoprotein, ameliorates Leishmania infection. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000276 (doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000276) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caradonna KL, Burleigh BA. 2011. Chapter 2—Mechanisms of host cell invasion by Trypanosoma cruzi. In Advances in parasitology (ed. Weiss LM, Tanowitz HB), pp. 33–61. New York, NY: Academic Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Real F, Mortara RA, Rabinovitch M.. 2010. Fusion between Leishmania amazonensis and Leishmania major parasitophorous vacuoles: live imaging of coinfected macrophages. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 4, e905 (doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000905) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang KP, Dwyer DM. 1978. Leishmania donovani. Hamster macrophage interactions in vitro: cell entry, intracellular survival, and multiplication of amastigotes. J. Exp. Med. 147, 515–530. (doi:10.1084/jem.147.2.515) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Castro R, Scott K, Jordan T, Evans B, Craig J, Peters EL, Swier K. 2006. The ultrastructure of the parasitophorous vacuole formed by Leishmania major. J. Parasitol. 92, 1162–1170. (doi:10.1645/GE-841R.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gardener PJ, Shchory L, Chance ML. 1977. Species differentiation in the genus Leishmania by morphometric studies with the electron microscope. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 71, 147–155. (doi:10.1080/00034983.1977.11687173) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gardener PJ. 1974. Pellicle-associated structures in the amastigote stage of Trypanosoma cruzi and Leishmania species. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 68, 167–176. (doi:10.1080/00034983.1974.11686935) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pham TD, Azar HA, Moscovic EA, Kurban AK. 1970. The ultrastructure of Leishmania tropica in the oriental sore. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 64, 1–4. (doi:10.1080/00034983.1970.11686657) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang W-W, Mendez S, Ghosh A, Myler P, Ivens A, Clos J, Sacks DL, Matlashewski G. 2003. Comparison of the A2 gene locus in Leishmania donovani and Leishmania major and its control over cutaneous infection. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 35 508–35 515. (doi:10.1074/jbc.M305030200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCall L-I, Matlashewski G. 2010. Localization and induction of the A2 virulence factor in Leishmania: evidence that A2 is a stress response protein. Mol. Microbiol. 77, 518–530. (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07229.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Doehl JSP, et al. 2017. Skin parasite landscape determines host infectiousness in visceral leishmaniasis. Nat. Commun. 8, 57 (doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00103-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rico E, Rojas F, Mony BM, Szoor B, Macgregor P, Matthews KR. 2013. Bloodstream form pre-adaptation to the tsetse fly in Trypanosoma brucei. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 3, 78 (doi:10.3389/fcimb.2013.00078) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bee A, Culley FJ, Alkhalife IS, Bodman-Smith KB, Raynes JG, Bates PA. 2001. Transformation of Leishmania mexicana metacyclic promastigotes to amastigote-like forms mediated by binding of human C-reactive protein. Parasitology 122, 521–529. (doi:10.1017/S0031182001007612) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Billker O, Lindo V, Panico M, Etienne AE, Paxton T, Dell A, Rogers M, Sinden RE, Morris HR. 1998. Identification of xanthurenic acid as the putative inducer of malaria development in the mosquito. Nature 392, 289–292. (doi:10.1038/32667) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Engstler M, Boshart M. 2004. Cold shock and regulation of surface protein trafficking convey sensitization to inducers of stage differentiation in Trypanosoma brucei. Genes Dev. 18, 2798–2811. (doi:10.1101/gad.323404) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gadelha APR, Cunha-e-Silva NL, de Souza W. 2013. Assembly of the Leishmania amazonensis flagellum during cell differentiation. J. Struct. Biol. 184, 280–292. (doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2013.09.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lehane MJ. 1997. Peritrophic matrix structure and function. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 42, 525–550. (doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.42.1.525) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gemetchu T. 1974. The morphology and fine structure of the midgut and peritrophic membrane of the adult female, Phlebotomus longipes Parrot and Martin (Diptera: Psychodidae). Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 68, 111–124. (doi:10.1080/00034983.1974.11686930) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Coutinho-Abreu IV, Sharma NK, Robles-Murguia M, Ramalho-Ortigao M. 2010. Targeting the midgut secreted PpChit1 reduces Leishmania major development in its natural vector, the sand fly Phlebotomus papatasi. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 4, e901 (doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000901) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Killick-Kendrick R, Molyneux DH, Ashford RW. 1974. Leishmania in phlebotomid sandflies. I. Modifications of the flagellum associated with attachment to the mid-gut and oesophageal valve of the sandfly. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 187, 409–419. (doi:10.1098/rspb.1974.0085) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sacks DL, Modi G, Rowton E, Späth G, Epstein L, Turco SJ, Beverley SM. 2000. The role of phosphoglycans in Leishmania–sand fly interactions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 406–411. (doi:10.1073/pnas.97.1.406) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Svárovská A, Ant TH, Seblová V, Jecná L, Beverley SM, Volf P. 2010. Leishmania major glycosylation mutants require phosphoglycans (lpg2−) but not lipophosphoglycan (lpg1−) for survival in permissive sand fly vectors. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 4, e580 (doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000580) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Myskova J, Svobodova M, Beverley SM, Volf P. 2007. A lipophosphoglycan-independent development of Leishmania in permissive sand flies. Microbes Infect. 9, 317–324. (doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2006.12.010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rogers ME, Ilg T, Nikolaev AV, Ferguson MAJ, Bates PA. 2004. Transmission of cutaneous leishmaniasis by sand flies is enhanced by regurgitation of fPPG. Nature 430, 463–467. (doi:10.1038/nature02675) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tetley L, Vickerman K. 1985. Differentiation in Trypanosoma brucei: host–parasite cell junctions and their persistence during acquisition of the variable antigen coat. J. Cell Sci. 74, 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Beattie P, Gull K. 1997. Cytoskeletal architecture and components involved in the attachment of Trypanosoma congolense epimastigotes. Parasitology 115, 47–55. (doi:10.1017/S0031182097001042) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hendry KA, Vickerman K. 1988. The requirement for epimastigote attachment during division and metacyclogenesis in Trypanosoma congolense. Parasitol. Res. 74, 403–408. (doi:10.1007/BF00535138) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barros VC, Oliveira JS, Melo MN, Gontijo NF. 2006. Leishmania amazonensis: chemotaxic and osmotaxic responses in promastigotes and their probable role in development in the phlebotomine gut. Exp. Parasitol. 112, 152–157. (doi:10.1016/j.exppara.2005.10.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Leslie G, Barrett M, Burchmore R. 2002. Leishmania mexicana: promastigotes migrate through osmotic gradients. Exp. Parasitol. 102, 117–120. (doi:10.1016/S0014-4894(03)00031-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oliveira JS, Melo MN, Gontijo NF. 2000. A sensitive method for assaying chemotaxic responses of Leishmania promastigotes. Exp. Parasitol. 96, 187–189. (doi:10.1006/expr.2000.4569) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Santrich C, Moore L, Sherwin T, Bastin P, Brokaw C, Gull K, LeBowitz JH. 1997. A motility function for the paraflagellar rod of Leishmania parasites revealed by PFR-2 gene knockouts. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 90, 95–109. (doi:10.1016/S0166-6851(97)00149-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Maga JA, Sherwin T, Francis S, Gull K, LeBowitz JH. 1999. Genetic dissection of the Leishmania paraflagellar rod, a unique flagellar cytoskeleton structure. J. Cell Sci. 112, 2753–2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cuvillier A, Redon F, Antoine JC, Chardin P, DeVos T, Merlin G. 2000. LdARL-3A, a Leishmania promastigote-specific ADP-ribosylation factor-like protein, is essential for flagellum integrity. J. Cell Sci. 113, 2065–2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wiese M, Kuhn D, Grünfelder CG. 2003. Protein kinase involved in flagellar-length control. Eukaryot. Cell 2, 769–777. (doi:10.1128/EC.2.4.769-777.2003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bengs F, Scholz A, Kuhn D, Wiese M. 2005. LmxMPK9, a mitogen-activated protein kinase homologue affects flagellar length in Leishmania mexicana. Mol. Microbiol. 55, 1606–1615. (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04498.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Adhiambo C, Forney JD, Asai DJ, LeBowitz JH. 2005. The two cytoplasmic dynein-2 isoforms in Leishmania mexicana perform separate functions. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 143, 216–225. (doi:10.1016/j.molbiopara.2005.04.017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Erdmann M, Scholz A, Melzer IM, Schmetz C, Wiese M. 2006. Interacting protein kinases involved in the regulation of flagellar length. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 2035–2045. (doi:10.1091/mbc.E05-10-0976) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Blaineau C, Tessier M, Dubessay P, Tasse L, Crobu L, Pagès M, Bastien P. 2007. A novel microtubule-depolymerizing kinesin involved in length control of a eukaryotic flagellum. Curr. Biol. 17, 778–782. (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.03.048) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tammana TVS, Sahasrabuddhe AA, Mitra K, Bajpai VK, Gupta CM. 2008. Actin-depolymerizing factor, ADF/cofilin, is essentially required in assembly of Leishmania flagellum. Mol. Microbiol. 70, 837–852. (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06448.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Casanova M, Crobu L, Blaineau C, Bourgeois N, Bastien P, Pagès M. 2009. Microtubule-severing proteins are involved in flagellar length control and mitosis in Trypanosomatids. Mol. Microbiol. 71, 1353–1370. (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06594.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tull D, Naderer T, Spurck T, Mertens HDT, Heng J, McFadden GI, Gooley PR, McConville MJ. 2010. Membrane protein SMP-1 is required for normal flagellum function in Leishmania. J. Cell Sci. 123, 544–554. (doi:10.1242/jcs.059097) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Harder S, Thiel M, Clos J, Bruchhaus I.. 2010. Characterization of a subunit of the outer dynein arm docking complex necessary for correct flagellar assembly in Leishmania donovani. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 4, e586 (doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000586) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Morrison LS, et al. 2012. Ecotin-like serine peptidase inhibitor ISP1 of Leishmania major plays a role in flagellar pocket dynamics and promastigote differentiation. Cell. Microbiol. 14, 1271–1286. (doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01798.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Aslett M, et al. 2010. TriTrypDB: a functional genomic resource for the Trypanosomatidae. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, D457–D462. (doi:10.1093/nar/gkp851) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sunter JD, Benz C, Andre J, Whipple S, McKean PG, Gull K, Ginger ML, Lukeš J. 2015. Flagellum attachment zone protein modulation and regulation of cell shape in Trypanosoma brucei life cycle transitions. J. Cell Sci. 128, 3117–3130. (doi:10.1242/jcs.171645) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lye L-F, Owens K, Shi H, Murta SMF, Vieira AC, Turco SJ, Tschudi C, Ullu E, Beverley SM. 2010. Retention and loss of RNA interference pathways in Trypanosomatid protozoans. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1001161 (doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001161) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Beneke T, Madden R, Makin L, Valli J, Sunter J, Gluenz E. 2017. A CRISPR Cas9 high-throughput genome editing toolkit for kinetoplastids. R. Soc. open sci. 4, 170095 (doi:10.1098/rsos.170095) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dean S, Sunter J, Wheeler RJ, Hodkinson I, Gluenz E, Gull K. 2015. A toolkit enabling efficient, scalable and reproducible gene tagging in trypanosomatids. Open Biol. 5, 140197 (doi:10.1098/rsob.140197) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sollelis L, et al. 2015. First efficient CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing in Leishmania parasites. Cell. Microbiol. 17, 1405–1412. (doi:10.1111/cmi.12456) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhang W-W, Matlashewski G. 2015. CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing in Leishmania donovani. mBio 6, e00861 (doi:10.1128/mBio.00861-15) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zauli RC, et al. 2012. A dysflagellar mutant of Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis isolated from a cutaneous leishmaniasis patient. Parasit. Vectors 5, 11 (doi:10.1186/1756-3305-5-11) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rogers ME, Chance ML, Bates PA. 2002. The role of promastigote secretory gel in the origin and transmission of the infective stage of Leishmania mexicana by the sandfly Lutzomyia longipalpis. Parasitology 124, 495–507. (doi:10.1017/S0031182002001439) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wheeler RJ, Gluenz E, Gull K. 2011. The cell cycle of Leishmania: morphogenetic events and their implications for parasite biology. Mol. Microbiol. 79, 647–662. (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07479.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wheeler RJ. 2015. Analyzing the dynamics of cell cycle processes from fixed samples through ergodic principles. Mol. Biol. Cell 26, 3898–3903. (doi:10.1091/mbc.E15-03-0151) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wheeler RJ. 2012. Generation, regulation and function of morphology in Leishmania and Trypanosoma. DPhil thesis, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK: See https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid%3Ac44354bc-5a93-4fce-a716-bb0a63131901. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gossage SM, Rogers ME, Bates PA. 2003. Two separate growth phases during the development of Leishmania in sand flies: implications for understanding the life cycle. Int. J. Parasitol. 33, 1027–1034. (doi:10.1016/S0020-7519(03)00142-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Monod J. 1941. Recherches sur la croissance des cultures bactériennes. Paris, France: Hermann. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Epstein W, Naono S, Gros F. 1966. Synthesis of enzymes of the lactose operon during diauxic growth of Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 24, 588–592. (doi:10.1016/0006-291X(66)90362-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Inbar E, Hughitt VK, Dillon LAL, Ghosh K, El-Sayed NM, Sacks DL. 2017. The transcriptome of Leishmania major developmental stages in their natural sand fly vector. mBio 8, e00029-17 (doi:10.1128/mBio.00029-17) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ambit A, Woods KL, Cull B, Coombs GH, Mottram JC. 2011. Morphological events during the cell cycle of Leishmania major. Eukaryot. Cell 10, 1429–1438. (doi:10.1128/EC.05118-11) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Svärd SG, Hagblom P, Palm JED. 2003. Giardia lamblia—a model organism for eukaryotic cell differentiation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 218, 3–7. (doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2003.tb11490.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Berriman M, et al. 2005. The genome of the African trypanosome Trypanosoma brucei. Science 309, 416–422. (doi:10.1126/science.1112642) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.El-Sayed NM, et al. 2005. The genome sequence of Trypanosoma cruzi, etiologic agent of Chagas disease. Science 309, 409–415. (doi:10.1126/science.1112631) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ivens AC, et al. 2005. The genome of the kinetoplastid parasite, Leishmania major. Science 309, 436–442. (doi:10.1126/science.1112680) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rotureau B, Subota I, Buisson J, Bastin P. 2012. A new asymmetric division contributes to the continuous production of infective trypanosomes in the tsetse fly. Dev. Camb. Engl. 139, 1842–1850. (doi:10.1242/dev.072611) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sharma R, Peacock L, Gluenz E, Gull K, Gibson W, Carrington M. 2008. Asymmetric cell division as a route to reduction in cell length and change in cell morphology in trypanosomes. Protist 159, 137–151. (doi:10.1016/j.protis.2007.07.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This article has no additional data.