Abstract

Background

Marital status is viewed as an independent prognostic factor for survival in various cancer types. However, its role in primary liver cancer has yet to be thoroughly explored.

Objective

To investigate the impact of marital status on survival outcomes among liver cancer patients.

Results

We finally identified 40,809 eligible liver cancer patients between 2004 and 2012, including 21,939 (53.8%) patients were married at diagnosis and 18,870 (46.2%) were unmarried (including 5,871 divorced/separated, 4,338 widowed and 8,660 single). Married patients enjoyed overall and cause-specific survival outcomes compared with patients who were divorced/separated, widowed, single, respectively. The survival benefit associated with marriage still persisted even after adjusted for known confounders. Widowed individuals were at greater risk of overall and cancer-specific mortality compared to other groups. Similar associations were observed in subgroup analyses according to SEER stage.

Materials and Methods

We used the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database to identify 40,809 patients diagnosed with primary liver cancer between 2004 and 2012. Kaplan-Meier analysis and Cox regression were performed to identify the influence of marital status on overall survival (OS) and liver cancer-specific survival (CSS).

Conclusions

In primary liver cancer patients, married patients enjoyed survival benefits while widowed persons suffered survival disadvantages in both overall survival and cancer-specific survival.

Keywords: primary liver cancer, marital status, surveillance, epidemiology and end results, survival analysis

INTRODUCTION

Primary liver cancer still represents common cancer and a leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide [1, 2]. With the development of newer, advanced treatments such as liver transplantation, hepatic resection, chemotherapy, and radiofrequency ablation, survival outcomes of patients have improved [3]. However, the 5-year survival rate for patients with liver cancer is 18%, which remains lower than many other cancers [4]. Therefore, there is an urgent need for additional methods to improve the prognosis of primary liver cancer.

Marital status has been reported to provide several health benefits for various diseases [5]. Early studies demonstrated that married persons had greater longevity and overall better health compared with the unmarried (including divorced/separated, widowed and single) [6–8]. Studies have already shown that marital status is an independent prognostic factor for better survival in various cancer types, such as gastric, ovarian, colorectal, testicular and pancreatic cancer [9–15]. However, this is not always the case as studies in patients with gastric cancer show [9, 16–18]. Despite the considerable research on cancer prognosis and marital status, to our knowledge, no specific studies have explored the relationship between marital status and prognosis of primary liver cancer so far. As such, it is important to address the impact of marital status on prognosis of liver cancer and potential underlying mechanisms. In this study, we used the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) cancer registry database to assess the risk of overall and cancer-specific mortality associated with marital status

RESULTS

Patient baseline characteristics

The study identified 40,809 eligible primary liver cancer patients were identified from 2004 to 2012, including 30,456 (74.6%) male and 10,353 (25.4%) female patients. 21,939 (53.8%) patients were married at diagnosis and 18,870 (46.2%) were unmarried including 5,871 (14.4%) separated/divorced 4,339 (10.6%) widowed, and 8,660 (21.2%) single. Table 1 summarized the relationship between clinicopathological characteristics and marital status. Among liver cancer patients, there was a male predominance in cancer incidence, which indicates a higher risk of liver carcinoma in men. Compared with unmarried patients, the married individuals had more high/moderate grade tumours at diagnosis and were more likely to undergo surgery or radiotherapy. However, the proportion of married persons in localized disease was similar to divorced/separated groups. Most of widowed persons were female rather than male and older than 60 years. The widowed patients were also less likely to present with the localized stage and received less therapy (surgery or radiotherapy) compared with married patients. Divorced/separated patients were more likely to be White and patients in the single group were the youngest.

Table 1. Baseline clinicopathologic features of liver cancer patients in SEER database.

| Characteristic | Total (%) |

Married (%) |

Divorced/ Separated(%) | Widowed (%) |

Single (%) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40809 (100) | 21939 (53.8) | 5871 (14.4) | 4339 (10.6) | 8660 (21.2) | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 30456 (74.6) | 17474 (79.6) | 4496 (76.6) | 1631 (37.6) | 6855 (79.2) | < 0.001 |

| Female | 10353 (25.4) | 4465 (20.4) | 1375 (23.4) | 2708 (62.4) | 1805 (20.8) | |

| Age | ||||||

| ≤ 60 | 19203 (47.1) | 9704 (44.2) | 3309 (56.4) | 519 (12.0) | 5671 (65.5) | < 0.001 |

| > 60 | 21606 (52.9) | 12235 (55.8) | 2562 (43.6) | 3820 (88.0) | 2989 (34.5) | |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 27753 (68) | 14767 (67.3) | 4282 (72.9) | 3050 (70.3) | 5654 (65.3) | < 0.001 |

| Black | 5323 (13.0) | 1862 (8.5) | 970 (16.5) | 464 (10.7) | 2027 (23.4) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 7093 (17.4) | 5022 (22.9) | 490 (8.3) | 759(17.5) | 822 (9.5) | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native |

479 (1.2) | 202 (0.9) | 105 (1.8) | 49 (1.1) | 123 (1.4) | |

| Unknown | 161 (0.4) | 86 (0.4) | 24 (0.4) | 17 (0.4) | 34 (0.4) | |

| Grade | < 0.001 | |||||

| High/Moderate | 10856 (26.6) | 6320 (28.8) | 1418 (24.2) | 1093(25.2) | 2025 (23.4) | |

| Poor/Undifferentiation | 4080 (10%) | 2392 (10.9) | 537 (9.1) | 442 (10.2) | 709 (8.2) | |

| Unknown | 25873 (63.4) | 13227 (60.3) | 3916 (66.7) | 2804 (64.6) | 5926 (68.4) | |

| Histotype | < 0.001 | |||||

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 36397 (89.2) | 19347 (88.2) | 5403 (92.0) | 3622 (83.5) | 8025 (92.7) | |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 4102 (10.1) | 2403 (11.0) | 428 (7.3) | 688 (15.9) | 583 (6.7) | |

| Combined | 310 (0.8) | 189 (0.9) | 40 (0.7) | 29 (0.7) | 52 (0.6) | |

| SEER stage | < 0.001 | |||||

| Localized | 18618 (45.6) | 10194 (46.5) | 2763 (47.1) | 1910 (44.0) | 3751 (43.3) | |

| Regional | 11908 (29.2) | 6418 (29.3) | 1702 (29.0) | 1160 (26.7) | 2628 (30.3) | |

| Distant | 7083 (17.4) | 3721(17.0) | 974 (16.6) | 757 (17.4) | 1631 (18.8) | |

| Unstaged | 3200 (7.8) | 1606 (7.3) | 432 (7.4) | 512 (11.8) | 650 (7.5) | |

| Therapy | < 0.001 | |||||

| Surgery, radiation or both | 11702 (28.7) | 7278 (33.2) | 1528 (26.0) | 872 (20.1) | 2024 (23.4) | |

| No surgery, radiation | 28422 (69.6) | 14311 (65.2) | 4223 (71.9) | 3384 (78.0) | 6504 (75.1) | |

| Unknown | 685 (1.7) | 350 (1.6) | 120 (2.0) | 83 (12.1) | 132 (1.5) |

Abbreviations

SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results.

Effect of clinicopathologic features on overall and liver cause-specific survival in the SEER database

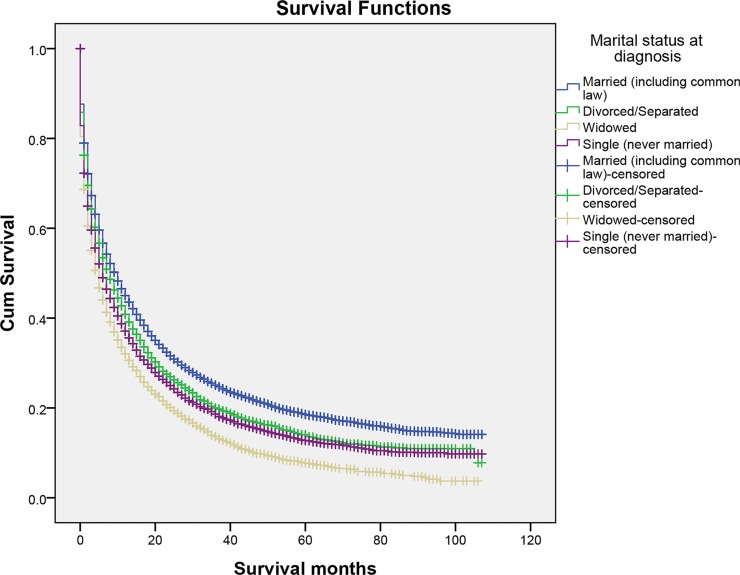

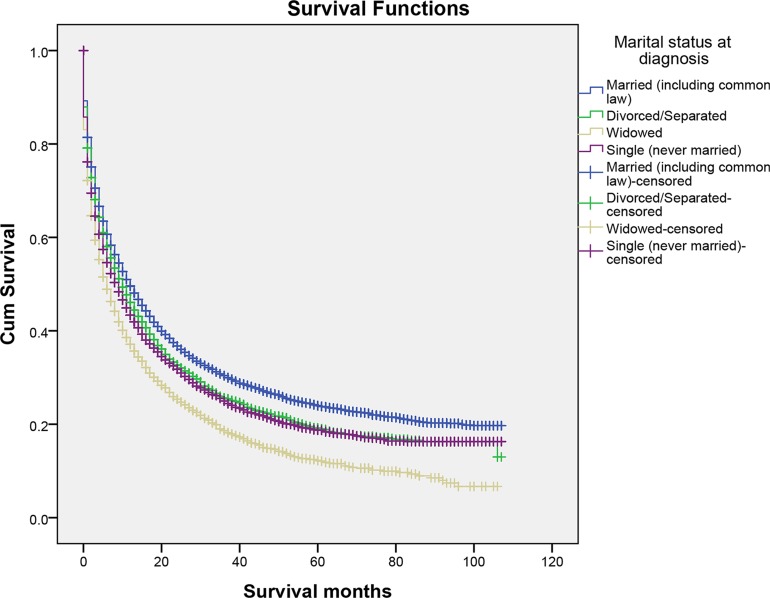

We performed Kaplan–Meier analysis to calculate overall and cause-specific survival time (OS and CSS) of primary liver cancer patients. (Table 2) The median overall survival time of the married group was ten months, while the separated/divorced, the widowed, and the single were eight, five, six months, respectively. The survival difference among different marital status was significant. (Log-rank test P < 0.001) (Figure 1) A similar trend was noted in the median cause-specific survival time. Married patients had the longest median cause-specific survival time. (Log-rank test P < 0.001) (Figure 2) In addition to marital status, other factors such as race, age, grade, histotype, SEER stage, and therapies were proved to be significant risk factors for prognosis by Kaplan–Meier analysis (Table 2). However, gender was associated with overall survival, whereas it was not related to cause-specific survival. Considering gender disparity among primary liver cancer [19], we also included gender into further multivariate survival analysis.

Table 2. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis for primary liver cancer-specific survival in SEER database.

| Characteristic | MST/OS (months) |

Kaplan-Meier | MST/CSS (months) |

Kaplan-Meier | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log Rank χ2 test |

P | Log Rank χ2 test |

P | |||

| Gender | 7.088 | 0.008 | 0.785 | 0.376 | ||

| Male | 8 | 10 | ||||

| Female | 8 | 11 | ||||

| Age | 390.08 | < 0.001 | 387.11 | < 0.001 | ||

| ≤ 60 | 10 | 13 | ||||

| > 60 | 7 | 8 | ||||

| Race | 324.04 | < 0.001 | 269.54 | < 0.001 | ||

| White | 8 | 10 | ||||

| Black | 6 | 8 | ||||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 11 | 15 | ||||

| American Indian /Alaska Native |

8 | 10 | ||||

| Unknown | 19 | 28 | ||||

| Marital Status | 526.86 | < 0.001 | 378.12 | < 0.001 | ||

| Married | 10 | 12 | ||||

| Divorced/Separated | 8 | 10 | ||||

| Widowed | 5 | 6 | ||||

| Single | 6 | 9 | ||||

| Grade | 1668.8 | < 0.001 | 1497.62 | < 0.001 | ||

| High/ Moderate | 17 | 22 | ||||

| Poor/Undifferentiation | 5 | 6 | ||||

| Unknown | 6 | 8 | ||||

| Histotype | 237.032 | < 0.001 | 361.59 | < 0.001 | ||

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 8 | 11 | ||||

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 5 | 6 | ||||

| Combined | 6 | 7 | ||||

| SEER Stage | 7437.67 | < 0.001 | 7738.67 | < 0.001 | ||

| Localized | 19 | 27 | ||||

| Regional | 6 | 7 | ||||

| Distant | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Unknown | 3 | 4 | ||||

| Therapy | 7174.26 | < 0.001 | 6442.10 | < 0.001 | ||

| Surgery, radiation or both | 32 | 44 | ||||

| No surgery, radiation | 4 | 5 | ||||

| Unknown | 9 | 12 | ||||

Abbreviations

MST, median survival time; OS, overall survival; CSS, cause-specific survival; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results.

Figure 1. The overall survival of patients with primary liver cancer according to marital status.

Figure 2. The cancer-caused specific survival of patients with primary liver cancer according to marital status.

Multivariate survival analysis for marital status on overall and cause-specific survival

When we adjusted all variables mentioned above in the multivariate analysis with Cox regression, gender, age, race, marital status grade, histotype, SEER stage, and therapy were identified as independent prognostic factors for overall and cause-specific survival among liver cancer patients. (Table 3) In the context of OS analysis, separated/divorced (HR = 1.08, 95% CI 1.05–1.12, P < 0.001), single (HR = 1.25, 95% CI 1.20–1.30, P < 0.001) or widowed (HR = 1.13, 95% CI 1.10–1.17, P < 0.001) patients had an increased risk of mortality compared with married patients. In term of CSS analysis, marital status was still identified as a protective factor for primary liver cancer prognosis (married, reference; separated/divorced, HR = 1.07, 95% CI 1.03–1.11, P = 0.001; the widowed, HR =1.21, 95% CI 1.16–1.26, P < 0.001 and single, HR = 1.09, 95% CI 1.06–1.13, P < 0.001). Additionally, male, older, black, poor differentiation/undifferentiated and combined histotype, and no surgery and/or radiotherapy were associated with poorer prognosis both in OS and CSS analysis.

Table 3. Multivariate analysis of overall and liver cancer cause specific survival.

| Characteristic | OS HR (95% CI) | P | CSS HR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | Reference | Reference | ||

| Female | 0.90 (0.88–0.93) | < 0.001 | 0.92 (0.89–0.95) | < 0.001 |

| Age | ||||

| ≤ 60 | Reference | Reference | ||

| > 60 | 1.22 (1.19–1.25) | < 0.001 | 1.23 (1.20–1.26) | < 0.001 |

| Race | ||||

| White | Reference | Reference | ||

| Black | 1.10 (1.06–1.14) | < 0.001 | 1.09 (1.05–1.13) | < 0.001 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.84 (0.81–0.87) | < 0.001 | 0.83 (0.80–0.86) | < 0.001 |

| American Indian /Alaska Native |

0.94 (0.84–1.04) | 0.227 | 0.93 (0.83–1.04) | 0.187 |

| Unknown | 0.62 (0.50–0.78) | < 0.001 | 0.59 (0.46–0.76) | < 0.001 |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married | Reference | Reference | ||

| Divorced/Separated | 1.08 (1.05–1.12) | < 0.001 | 1.07 (1.03–1.11) | 0.001 |

| Widowed | 1.25 (1.20–1.30) | < 0.001 | 1.21 (1.16–1.26) | < 0.001 |

| Single | 1.13 (1.10–1.17) | < 0.001 | 1.09 (1.06–1.13) | < 0.001 |

| Grade | ||||

| High/ Moderate | Reference | Reference | ||

| Poor/Undifferentiation | 1.50 (1.44–1.56) | < 0.001 | 1.55 (1.49–1.63) | < 0.001 |

| Unknown | 1.25 (1.21–1.28) | < 0.001 | 1.24 (1.20–1.28) | < 0.001 |

| Histotype | ||||

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | Reference | Reference | ||

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 1.05 (1.01–1.09) | 0.023 | 1.09 (1.05–1.13) | 0.002 |

| Combined | 1.14 (1.00–1.29) | 0.046 | 1.16 (1.02–1.33) | 0.037 |

| SEER Stage | ||||

| Localized | Reference | Reference | ||

| Regional | 1.69 (1.64–1.74) | < 0.001 | 1.82 (1.77–1.88) | < 0.001 |

| Distant | 2.72 (2.63–2.81) | < 0.001 | 3.03 (2.92–3.13) | < 0.001 |

| Unknown | 1.77 (1.69–1.84) | < 0.001 | 1.90 (1.81–1.98) | < 0.001 |

| Therapy | ||||

| Surgery , radiation or both | Reference | Reference | ||

| No surgery, radiation | 2.56 (2.48–2.64) | < 0.001 | 2.65 (2.56–2.74) | < 0.001 |

| Unknown | 1.94 (1.76–2.13) | < 0.001 | 1.95 (1.76–2.16) | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations

OS, Overall survival; CSS, Cause-specific survival; HR, Hazard ratio; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results.

Subgroup analysis for evaluating the effect of marital status on overall and cause-specific survival according to SEER stage

We further explored the difference between marital status and prognosis of primary liver cancer in each stage subgroup according to SEER. Results were summarized in Table 4 and we observed some interesting findings. It was found that the marital status was still an independent prognostic factor for better overall and cause-specific survival in each SEER stage. The widowed patients always displayed higher hazard ratio of mortality compared with other groups. It was noteworthy that widowed patients were at the highest risk of both overall and cause-specific survival in localised stage. In regional stage, the difference between the divorced/separated and married group was not significant in CSS analysis.

Table 4. Multivariate analysis of marital status on liver cancer overall and cause-specific survival according to different SEER stage.

| Characteristic | OS HR (95% CI) | P | CSS HR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Localized | ||||

| Married | Reference | Reference | ||

| Divorced/Separated | 1.11 (1.05–1.17) | < 0.001 | 1.10 (1.03–1.16) | 0.005 |

| Widowed | 1.41 (1.33–1.51) | < 0.001 | 1.36 (1.27–1.46) | < 0.001 |

| Single | 1.28 (1.22–1.34) | < 0.001 | 1.22 (1.16–1.29) | < 0.001 |

| Regional | ||||

| Married | Reference | Reference | ||

| Divorced/Separated | 1.07 (1.01–1.14) | 0.022 | 1.06 (0.99–1.13) | 0.091 |

| Widowed | 1.19 (1.11–1.29) | < 0.001 | 1.16 (1.08–1.26) | 0.001 |

| Single | 1.11 (1.06–1.17) | < 0.001 | 1.09 (1.03–1.15) | 0.002 |

| Distant | ||||

| Married | Reference | Reference | ||

| Divorced/Separated | 1.14 (1.06–1.23) | < 0.001 | 1.14 (1.06–1.24) | 0.001 |

| Widowed | 1.14 (1.04–1.24) | 0.004 | 1.12 (1.02–1.22) | 0.016 |

| Single | 1.10 (1.04–1.18) | 0.002 | 1.07 (1.01–1.15) | 0.034 |

Abbreviations

OS, Overall survival; CSS, Cause-specific survival; HR, Hazard ratio; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

Adjusted covariates for gender, age, race, grade, histotype, and therapy.

DISCUSSION

In the large, population based studies, we firstly explored the influence of marriage on overall and cause-specific mortality in primary liver cancer patients. Our study had found that married groups experienced both better overall and cause-specific survival outcomes than the unmarried groups, including the divorced/separated, the widowed and the single ones. Interestingly, the beneficial effect of being married persisted even after being adjusted for gender, age, race, grade, histotype, SEER stage, and therapies in multivariable analyses. Moreover, the widowed subgroups had a survival disadvantage compared with other groups. Our finding indicated that marital status exerts a protective effect on the survival outcomes of primary liver cancer, which is consistent with previous observations conducted on other types of cancer. [9, 17, 20] In addition, we observed an intriguing finding that primary liver cancer might preferentially occur in males. Additionally, female gender was associated with the better prognosis, which suggests that gender bias exists among patients with liver cancer [21, 22] It has been well documented that the poor prognosis of many cancers was closely associated with delayed diagnosis [23]. In the present study, however, this trend was not so obvious since the percentage of patients in the localized stage was highest in the divorced/separated group (47.1%) compared with 46.5%, 44.0%, and 43.3% in the married, the widowed and the single groups, respectively. Therefore, favorable survival outcomes in the married group were not due to the advantage of early detection. Compared with unmarried ones, the married had a higher percentage of surgery and radiation treatments, which partly attributed to their survival benefits. It also indicated that might be protective for cancer patients. It is plausible that differences in survival in patients with different marital status may at least stem from better access to the medical remedy.

Although survival benefits associated with marriage are supported by a large body of studies, underlying mechanisms behind this correlation are not clearly understood. Several biological, psychological and social theories have been postulated to explain this phenomenon. It is speculated that married people may have better access to healthcare and possess strong financial resources compared with unmarried persons [20, 24], which lead to early detections and treatments. However, this could not substantively explain the phenomenon that poor socioeconomic status still affects survival outcomes adversely among countries with universal access to free healthcare [25–27]. Other crucial factors, such as social and psychological support, might contribute to better prognosis among married patients. It is well known that a diagnosis of cancer is psychologically distressing for most patients [28]. It had been reported that single cancer patients had a higher risk of psychological distress, anxiety and depression compared with married patients, since no spouse could afford sufficient social supports and share emotional burden with them [15, 29]. Accordingly, patients with sufficient emotional supports might be associated with better prognosis, supported by the result that widowed patients displayed the poorest survival outcomes than other marital status [17]. The potential mechanisms underlying this correlation might be associated with health immune and endocrine function [30]. Psychological stress and depression have been reported to result in immune dysfunction and dysregulation of various endocrine hormones, such as catecholamines and cortisol [30, 31]. It was reported that cortisol and catecholamines could accelerate malignancy growth and metastasis via immunosuppressive actions, both in vitro and in vivo [32–34]. Besides, cortisol patterns were also identified as a predictor of better survival among breast and lung cancer [35, 36]. At the same time, married individuals had better adherence with prescribed treatments and promoted healthy lifestyles than unmarried patients [37, 38].

In the light of certain limitations, however, our results of this study must be interpreted with caution. First, the marital status of some patients may change during the follow-up period, which may misestimate the protective effect of marriage. We could not adjust this factor because SEER database only provides marital status at the diagnosis. Secondly, SEER is unable to provide other important confounding factors, such as chemotherapy, other types of therapy, socioeconomic factors, and concurrent hepatitis B infection. These factors might also influence the association between the marriage and the prognosis. Thirdly, the information of marital duration and satisfaction is inaccessible in the SEER database. We could not explore this relationship in depth. Last but not the least, we could not avoid some bias (such as selection bias) inherent in the retrospective study, which might be liable to introduce some bias into conclusions.

Despite these potential limitations, the strength of our studies lies in large and representative population source. In summary, results indicated that married persons enjoyed survival benefits and unmarried patients were at higher risk of overall and cancer-specific mortality. We speculated that psychosocial factors and social support may contribute better survival outcomes among married patients. More social supports and care should be provided for unmarried patients in our clinic practice, especial for the widowed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data source

We obtained data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program, which is sponsored by the National Cancer Institute [20]. The SEER program includes data from 18 population-based cancer registries from 1973 to 2012, which represents approximately 30% of the population in the US [11]. It collects data about cancer incidence, stage, grade, therapy as well as demographic information, such as age, sex, race, and marital status. The current dataset used for this analysis was based on Incidence-SEER 18 Regs Research Data + Hurricane Katrina Impacted Louisiana Cases, Nov 2014 Sub (1973–2012 varying).

Patient selection and data extracted

We searched for patients diagnosed between 2004 and 2012 with primary liver cancer and marital status by the SEER-stat software (SEER*Stat 8.2.1). Patients were included if they met following criteria: (1) patients were aged 18 years or older at diagnosis; (2) primary liver cancer was diagnosed between 2004 and 2012; (3) histological types were limited to NOS, fibrolamellar, scirrhous, spindle cell variant, clear cell type, pleomorphic type hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), cholangiocarcinoma, combined (code, 8170, 8171, 8172, 8173, 8174, 8175, 8160, and 8180). Patients were excluded according to following criteria: (1) age at diagnosis was less than 18 years; (2) incomplete clinical information; (3) unknown marital status, and unknown cause of death or unknown survival months. This study was based on public data from the SEER database, and we obtained permission to access the research data files with the reference number 14673-Nov2014. Gender, age, race, marital status, grade, histotype, SEER stage, therapy, the cause of death and survival time were extracted from the SEER database. Since it did not include interaction with human or personal identifying information, our study did not require informed consent and was approved by the review board of the Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University medical school, Zhejiang, China.

Statistical analysis

We performed descriptive statistics to summary the baseline characteristics of patients with different marital status by χ2 test. Kaplan-Meier analysis and Cox regression models were adopted to identify several risk factors for survival outcomes. The endpoints of this study were overall survival and cause-specific survival. In overall survival analysis, any cause of deaths was treated as events and survivors were treated as censored events. Among cause-specific survival, deaths attributed to liver cancer were considered as events and deaths from other causes or survivors were treated as censored events. All of the statistical analyses were performed by SPSS for Windows, version 20 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). All P values were two-sided and P < 0.05 was considered statistical significance.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms Wenjing Dong for her help in data management.

Abbreviations

- SEER

Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- ICC

intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

- OS

overall survival

- CSS

cause-specific survival

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential competing interests.

Author’s contributors

SLM and HXK contributed to conception and design of the study. HXK and LZH contributed to the data acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data. HXK, LZH, QY, XDH, JPP and SLM contributed to writing and editing the manuscript. All authors commented on drafts of the paper and have approved the final draft of the manuscript.

GRANT SUPPORT

The work was funded by the Zhejiang provincial medical platform 2015 specialists class B (2015 RCB016); Zhejiang province key science and technology innovation team (2013TD13); National Natural Science Foundation of China (81372623, 81302070).

REFERENCES

- 1.Herszenyi L, Tulassay Z. Epidemiology of gastrointestinal and liver tumors. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2010;14:249–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Venook AP, Papandreou C, Furuse J, de Guevara LL. The incidence and epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: a global and regional perspective. Oncologist. 2010;15:5–13. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-S4-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altekruse SF, McGlynn KA, Dickie LA, Kleiner DE. Hepatocellular carcinoma confirmation, treatment, and survival in surveillance, epidemiology, and end results registries, 1992–2008. Hepatology. 2012;55:476–482. doi: 10.1002/hep.24710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uchino BN. Social support and health: a review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. J Behav Med. 2006;29:377–387. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu YR, Goldman N. Mortality differentials by marital status: an international comparison. Demography. 1990;27:233–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaplan RM, Kronick RG. Marital status and longevity in the United States population. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:760–765. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.037606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ikeda A, Iso H, Toyoshima H, Fujino Y, Mizoue T, Yoshimura T, Inaba Y, Tamakoshi A, Group JS. Marital status and mortality among Japanese men and women: the Japan Collaborative Cohort Study. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:73. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang J, Gan L, Wu Z, Yan S, Liu X, Guo W. The influence of marital status on the stage at diagnosis, treatment, and survival of adult patients with gastric cancer: a population-based study. Oncotarget. 2016 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Q, Gan L, Liang L, Li X, Cai S. The influence of marital status on stage at diagnosis and survival of patients with colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:7339–7347. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inverso G, Mahal BA, Aizer AA, Donoff RB, Chau NG, Haddad RI. Marital status and head and neck cancer outcomes. Cancer. 2015;121:1273–1278. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thuret R, Sun M, Budaus L, Abdollah F, Liberman D, Shariat SF, Iborra F, Guiter J, Patard JJ, Perrotte P, Karakiewicz PI. A population-based analysis of the effect of marital status on overall and cancer-specific mortality in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the penis. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24:71–79. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-0091-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahdi H, Kumar S, Munkarah AR, Abdalamir M, Doherty M, Swensen R. Prognostic impact of marital status on survival of women with epithelial ovarian cancer. Psychooncology. 2013;22:83–88. doi: 10.1002/pon.2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abern MR, Dude AM, Coogan CL. Marital status independently predicts testis cancer survival—an analysis of the SEER database. Urol Oncol. 2012;30:487–493. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baine M, Sahak F, Lin C, Chakraborty S, Lyden E, Batra SK. Marital status and survival in pancreatic cancer patients: a SEER based analysis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21052. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qiu M, Yang D, Xu R. Impact of marital status on survival of gastric adenocarcinoma patients: Results from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Database. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21098. doi: 10.1038/srep21098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou R, Yan S, Li J. Influence of marital status on the survival of patients with gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 doi: 10.1111/jgh.13217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ljung R, Drefahl S, Andersson G, Lagergren J. Socio-demographic and geographical factors in esophageal and gastric cancer mortality in Sweden. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62067. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aizer AA, Chen MH, McCarthy EP, Mendu ML, Koo S, Wilhite TJ, Graham PL, Choueiri TK, Hoffman KE, Martin NE, Hu JC, Nguyen PL. Marital status and survival in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3869–3876. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.6489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yeh SH, Chen PJ. Gender disparity of hepatocellular carcinoma: the roles of sex hormones. Oncology. 2010;78:172–179. doi: 10.1159/000315247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hefaiedh R, Ennaifer R, Romdhane H, Ben Nejma H, Arfa N, Belhadj N, Gharbi L, Khalfallah T. Gender difference in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Tunis Med. 2013;91:505–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richards MA. The size of the prize for earlier diagnosis of cancer in England. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:S125–129. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ayanian JZ, Kohler BA, Abe T, Epstein AM. The relation between health insurance coverage and clinical outcomes among women with breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:326–331. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307293290507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arntzen A, Nybo Andersen AM. Social determinants for infant mortality in the Nordic countries, 1980–2001. Scand J Public Health. 2004;32:381–389. doi: 10.1080/14034940410029450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vallgarda S. Addressing individual behaviours and living conditions: four Nordic public health policies. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:6–10. doi: 10.1177/1403494810378922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jakobsen L, Niemann T, Thorsgaard N, Thuesen L, Lassen JF, Jensen LO, Thayssen P, Ravkilde J, Tilsted HH, Mehnert F, Johnsen SP. Dimensions of socioeconomic status and clinical outcome after primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:641–648. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.112.968271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaiser NC, Hartoonian N, Owen JE. Toward a cancer-specific model of psychological distress: population data from the 2003–2005 National Health Interview Surveys. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:291–302. doi: 10.1007/s11764-010-0120-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldzweig G, Andritsch E, Hubert A, Brenner B, Walach N, Perry S, Baider L. Psychological distress among male patients and male spouses: what do oncologists need to know? Ann Oncol. 2010;21:877–883. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garssen B, Goodkin K. On the role of immunological factors as mediators between psychosocial factors and cancer progression. Psychiatry Res. 1999;85:51–61. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(99)00008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moreno-Smith M, Lutgendorf SK, Sood AK. Impact of stress on cancer metastasis. Future Oncol. 2010;6:1863–1881. doi: 10.2217/fon.10.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McEwen BS, Biron CA, Brunson KW, Bulloch K, Chambers WH, Dhabhar FS, Goldfarb RH, Kitson RP, Miller AH, Spencer RL, Weiss JM. The role of adrenocorticoids as modulators of immune function in health and disease: neural, endocrine and immune interactions. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1997;23:79–133. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(96)00012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lointier P, Wildrick DM, Boman BM. The effects of steroid hormones on a human colon cancer cell line in vitro. Anticancer Res. 1992;12:1327–1330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sapolsky RM, Donnelly TM. Vulnerability to stress-induced tumor growth increases with age in rats: role of glucocorticoids. Endocrinology. 1985;117:662–666. doi: 10.1210/endo-117-2-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sephton SE, Sapolsky RM, Kraemer HC, Spiegel D. Diurnal cortisol rhythm as a predictor of breast cancer survival. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:994–1000. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.12.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sephton SE, Lush E, Dedert EA, Floyd AR, Rebholz WN, Dhabhar FS, Spiegel D, Salmon P. Diurnal cortisol rhythm as a predictor of lung cancer survival. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;30:S163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen SD, Sharma T, Acquaviva K, Peterson RA, Patel SS, Kimmel PL. Social support and chronic kidney disease: an update. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2007;14:335–344. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haley WE. Family caregivers of elderly patients with cancer: understanding and minimizing the burden of care. J Support Oncol. 2003;1:25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]