Abstract

Objective

To investigate which variables present prior and early after stroke may have an impact on the level of physical activity (PA) 1 year poststroke.

Design

Prospective longitudinal cohort and logistic regression analysis.

Setting

Stroke Unit at Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden.

Participants

117 individuals as part of the Stroke Arm Longitudinal Study (SALGOT) admitted to the stroke unit during a period of 18 months were consecutively recruited. The inclusion criteria were: first-time stroke, impaired upper extremity function, admitted to the stroke unit within 3 days since onset, local residency and ≥18 years old. The exclusion criteria were: upper extremity condition or severe multi-impairment prior to stroke, short life expectancy and non-Swedish speaking. 77 participants followed up at 1 year poststroke were included in the analysis.

Primary outcome

PA level 1 year after stroke was assessed using a 6-level Saltin-Grimby Scale, which was first dichotomised into mostly inactive or mostly active and second into low or moderate/high level of PA.

Results

Being mostly inactive 1 year after stroke could be predicted by age at stroke onset (OR 1.07, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.13, p=0.041), functional dependency at discharge (OR 7.01, 95% CI 1.73 to 28.43, p=0.006) and prestroke PA (OR 7.46, 95% CI 1.51 to 36.82, p=0.014). Having a low level of PA 1 year after stroke could be predicted by age at stroke onset (OR 1.13, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.21, p<0.001) and functional dependency at discharge (OR 3.62, 95% CI 1.09 to 12.04, p=0.036).

Conclusions

Previous low level of PA, older age and functional dependency all provided value in predicting low PA 1 year after stroke. These results indicate that age and simple clinical evaluations early after stroke may be useful to help clinicians identify persons at risk of being insufficiently active after stroke. Further research is needed to clarify if these findings may apply to the large population of stroke survivors.

Trial registration number

ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01115348).

Keywords: stroke, physical activity, motor activity, prognosis, outcome assessment

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Clinically important parameters prior to and early after stroke were included.

Longitudinal consecutively recruited cohort study with 1-year follow-up time.

Clinically relevant dichotomisation of physical activity levels produced interpretable data.

Despite relatively large cohort, the number of included predictors was limited due to small number of cases for some variables.

Persons with minor stroke showing no upper extremity impairment early after stroke were not included.

Introduction

Low physical activity (PA) has shown to be an independent risk factor for stroke,1–3 and PA is a part of primary1 as well as secondary prevention in most of the stroke guidelines.4 The WHO has identified physical inactivity to be the fourth leading risk factor for overall global mortality.5 The definition of PA according to WHO is ‘any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure including activities undertaken while working, playing, carrying out household chores, travelling and engaging in recreational pursuits’.6 Higher PA level prestroke may predict a less severe stroke,7 8 decrease the overall risk for death from first time stroke9 and is associated with a better functional status poststroke.7 10 11

It is a complex question to answer why some people are physically active after having a stroke and others are not. PA in healthy populations has shown to be influenced by factors such as age, gender, motivation, previous PA, self-efficacy and health status.12 13 Being physically active poststroke is associated with a better quality of life and has a positive correlation to functional ability.14 The PA level among stroke survivors has been shown to be significantly lower than in a healthy reference population15–19 and correlates with walking ability, balance and physical fitness,15 but cannot be explained by motor disability alone.16 20 Barriers to PA reported by stroke survivors include lack of motivation, fear of falling, inaccessibility to training centres and physical impairments.21 22 It is, however, not clear to what extent factors connected to the prestroke lifestyle and medical status may be associated with the PA level among stroke survivors. Identifying persons at risk of being inadequately active poststroke may help to target specific interventions for this group at an early stage. The purpose of this study was to investigate which possible prestroke and early predictor variables may impact the level of PA 1 year after the first-time stroke.

Materials and methods

Population and data collection

This longitudinal study is a part of the Stroke Arm Longitudinal (SALGOT) Study at the University of Gothenburg,23 with the original purpose to describe upper extremity functioning after stroke. Over a period of 18 months, in 2009–2010, consecutively, every person who met the criteria was included to the SALGOT Study from one of the largest out of three comprehensive Stroke Units at the Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg. The following inclusion criteria were used: (1) first-time stroke according to International Classification of Diseases codes I61 intracerebral haemorrhage or I63 ischaemic stroke; (2) impaired upper extremity function, defined as not achieving the maximal points at the Action Research Arm Test (ARAT)243 days poststroke; (3) admitted to the Stroke unit within 3 days since stroke onset; (4) residency in the Gothenburg urban area, within 35 km from the hospital and (5) ≥18 years of age. The exclusion criteria were: (1) an upper extremity injury/condition prior to stroke; (2) severe multi-impairments or diminished physical condition prior to stroke; (3) short life expectancy and (4) non-Swedish speaking. Three experienced physiotherapists performed all clinical assessments according to a standardised protocol.23

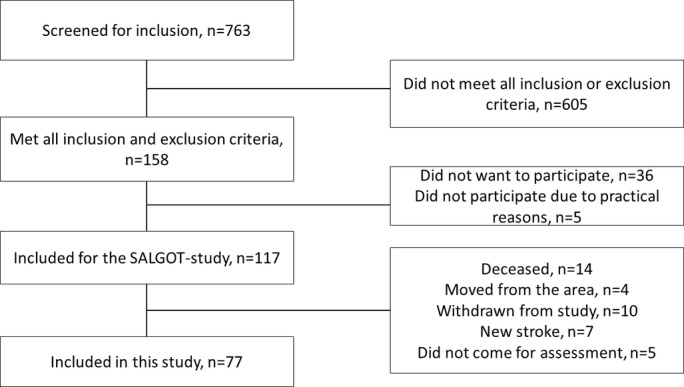

In SALGOT, the patients were assessed at admission and discharge as well as at 3 and 10 days; at 3, 4 and 6 weeks; and at 3, 6 and 12 months poststroke. In the current study, data from admission, discharge, 3 days and 12 months were used. Most assessments were performed at the hospital and only at persons’ home or nursing home when the participant was unable to travel. Prior power analysis for SALGOT to determine a minimum of 6 points change on ARAT (statistical power of 0.8, α=0.05) and considering a 30% dropout rate indicated that a sample size of 114 was needed. From a total cohort of 763 persons, 117 were included in the SALGOT study and 77 still remained in the study at 1 year poststroke (figure 1). The main reason for not being assessed at 1 year was death (n=14) (figure 1). The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Gothenburg (225-08). All participants or their next of kin gave written informed consent. The STROBE (Strengthening The Reporting of OBservational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines for reporting observational data were followed.25

Figure 1.

Flowchart for inclusion of the study participants.

Potential predictor variables

Potential predictors prior and close to the stroke onset, theorised to have impact on PA, were considered for model building.12 13 15 Prior stroke predictor variables included in the analyses were: smoking, living alone, transient ischaemic attack (TIA), diabetes, atrial fibrillation, treatment for high blood pressure and PA level. Other predictors included were: age, gender, type of stroke, stroke severity, upper extremity functioning 3 days poststroke and functional dependency at discharge (Modified Rankin Scale (mRS)), shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics, clinical characteristics and considered predictor variables

| Demographic and clinical characteristics (N=77) | |

| Age at stroke onset, years, mean (SD) | 67.2 (11.9) |

| Men, n (%) | 46 (59.7) |

| Haemorrhagic stroke,* n (%) | 11 (14.3) |

| Smoking,*† n (%), n=76 | 18 (23.7) |

| Living alone,* n (%) | 31 (40.3) |

| TIA/amaurosis fugax,*† n (%), n=76 | 4 (5.3) |

| Diabetes,*† n (%) | 10 (13) |

| Atrial fibrillation,*† n (%), n=76 | 11 (14.5) |

| Treatment for high blood pressure,* n (%), n=76 | 26 (34.2) |

| NIHSS at admission, median (q1–q3) | 7 (3–12.5) |

| ARAT at 3 days, median (q1–q3), n=74 | 7 (0–47) |

| mRS at discharge from stroke unit, n (%) | |

| Independent walkers (grade 0–3) | 37 (48.1) |

| Unable to walk independently (grade 4–5) | 40 (51.9) |

| Prestroke PA, n (%), n=73 | |

| Mostly inactive (grade 1–2) | 19 (26.0) |

| Low (grade 1–3) | 43 (58.9) |

| Acute hospital stay, days, mean (SD) | 12.6 (7.1) |

| Discharge to postacute hospital stay, days, n (%) | |

| Ordinary home | 27 (35) |

| In-hospital rehabilitation unit | 46 (60) |

| Nursing home | 4 (5) |

*Prior to stroke, †Not included in the prediction models due to too few observations.

ARAT, Action Research Arm Test; mRS, Modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS, National Institute of Stroke Scale; PA, physical activity; q1–q3, first to third quartile; TIA, transient ischaemic attack; y/n,yes/no.

Information of history of smoking, whether the participant shared livings with another adult and medical history prior to stroke were acquired by the national Swedish Stroke Register26 or medical charts. The stroke severity at admission to the hospital was assessed using the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS).27 The upper extremity functioning was assessed using the ARAT, which includes 19 items scored on a four-grade ordinal scale, with a total score varying from 0 to 57 points, where a higher score indicates less limitation.24 The functional dependency at discharge from the stroke unit (mean time 13 days, SD 7,4 range 1–42) was assessed using the mRS.28 The mRS is an ordinal scale ranging from 0 to 6 where lower numbers indicate less dependency.28 The mRS was dichotomised between the grade 3 and 4 creating one group that contained persons able to walk without assistance (no/slight/moderate disability, grades 1–3) and one group who could not (moderately severe to severe disability, grades 4–5). The self-reported PA level was recorded using a 6-level scale for classification of PA level (including leisure time, occupational and household activities) (online supplementary appendix A), originally developed from the four- graded Saltin-Grimby Scale.29 30 The participants’ PA level was scored through an interview within 3 days and at 1 year poststroke considering the PA level during the previous 6 months. In the statistical analyses, the PA was dichotomised in two different ways. First, to mostly inactive (grade 1–2) or mostly active (grade 3–5) and; second, to low (grade 1–3) or moderate/high activity level (4–5). The first dichotomisation was selected to match the original four-level scale based on prevention of cardiovascular disease.31 The second dichotomisation was selected to match the level of PA (of 30 min of activity, 5 days per week) recommended by the WHO in order to prevent morbidity.6 Within each prediction model, the same dichotomisation of PA level was used for outcome and for predictor variable.

bmjopen-2017-016369supp001.pdf (282.9KB, pdf)

Statistics

Differences between groups were investigated with Fisher's exact test, Mann-Whitney U test or t-test depending on data level. Demographic data were presented with medians and percentiles or means and SD. The statistically significant level was set to p<0.05 unless stated otherwise. A multivariate logistic regression was used to investigate which predictor variables may impact on the PA level 1 year after stroke. Two separate models were built, one for each dichotomisation of the outcome variable. As first step in selection of potential predictor variables for the regression models, the cross tabulation was used to identify and exclude predictor variables with less than five observations in any subgroup. Collinearity between predictor variables was checked for using Spearman's rank correlation test for ordinal variables or likelihood ratio test (LRT) for binary variables. Variables with correlation above 0.7 were considered for collinearity. Second step was a series of univariate logistic regression analysis performed on all variables not excluded by the cross tabulation in order to identify significant variables for further analyses (significance level p<0.25, tested with Wald's test). Third, the variables that were significant in the univariate step was put in multivariate models, built on the enter method in which all predictor variables not reaching the significance level of 0.05 were ruled out. Individuals with missing data on any of the variables included in the final multivariate models were excluded for analysis (table 1). Fourth, all of the previously ruled out variables were then reinserted in the final model one by one to check for possible significant effect in the model (p<0.05, LRT). Finally, the models were analysed with the LRT, percent of correct classification, Nagelkerke R2 and the Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness of fit test. Results are presented as OR with 95% CI. Data were analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software.

Results

Clinical characteristics

The group of non-participants not assessed at 1 year from the SALGOT cohort (n=40) was older (mean difference 6.23 years, p=0.01), had a higher incidence of atrial fibrillation (p=0.04) and were less active prior to their stroke (p=0.03). No other statistical significant differences were found between the groups. Demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in table 1. Prior to stroke, 74% (n=54) of the participants were considered to be mostly active, in contrast to 61% (n=47) at 1 year poststroke. Similarly, 41% (n=30) of the participants had a moderate to high activity level prior to stroke in contrast to 34% (n=26) 1 year later.

Selection of predictor variables

The type of stroke along with smoking, TIA, diabetes and atrial fibrillation prior to stroke contained too few individuals in subgroups and were, therefore, not included into further analysis. Strong significant collinearity was found between the predictor variables: mRS and ARAT (−0.74). These two variables were, therefore, entered into separate models and their impact to respective model compared. Thus, seven possible predictor variables were considered to be entered in the multivariate models in this second step. LRT showed a significant correlation between gender and prestroke PA (LRT=5.910, p=0.02 and between treatment for high blood pressure prior to stroke and prestroke PA (LRT=10.358, p=0.01). The results from the univariate analysis are presented in an online supplementary appendix B. None of the variables that were reinserted in the final step for the multivariate analysis were significant (p>0.05).

Predicting being mostly inactive

The final model for predicting being mostly inactive poststroke included three significant predictor variables: age, functional dependency (mRS) and prestroke PA (table 2a).

Table 2.

Logistic regression models for predicting PA level 1 year poststroke

| Coefficient | B | SE | Wald's test | df | p | OR (95% CI) |

| (a) Dependent variable of mostly inactive (n=73) | ||||||

| Constant | −6.52 | 2.15 | 9.17 | 1 | 0.002 | 0.001 |

| Age | 0.06 | 0.03 | 4.18 | 1 | 0.041 | 1.07 (1.00 to 1.13) |

| mRS at discharge | 1.95 | 0.71 | 7.43 | 1 | 0.006 | 7.01 (1.73 to 28.43) |

| Prestroke PA (mostly inactive) | 2.01 | 0.81 | 6.10 | 1 | 0.014 | 7.46 (1.51 to 36.82) |

| Test | Χ2 | df | p | |||

| Likelihood ratio test | 32.59 | 3 | <0.001 | |||

| Hosmer and Lemeshow | 9.66 | 8 | 0.290 | |||

| (b) Dependent variable of low level of PA (n=77) | ||||||

| Constant | −8.12 | 2.25 | 13.03 | 1 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Age | 0.13 | 0.03 | 13.52 | 1 | <0.001 | 1.13 (1.06 to 1.21) |

| mRS at discharge | 1.29 | 0.61 | 4.41 | 1 | 0.036 | 3.62 (1.09 to 12.04) |

| Test | Χ2 | df | p | |||

| Likelihood ratio test | 30.47 | 2 | <0.001 | |||

| Hosmer and Lemeshow | 3.28 | 7 | 0.858 | |||

Dependent variable coded as (a) mostly active=0, mostly inactive=1; (b) moderate/high PA=0, low PA=1; Cox and Snell R2(a)=0.360; (b)=0.327 Nagelkerke R2(a)=0.489; (b)=0.453.

PA, physical activity; mRS, Modified Rankin Scale.

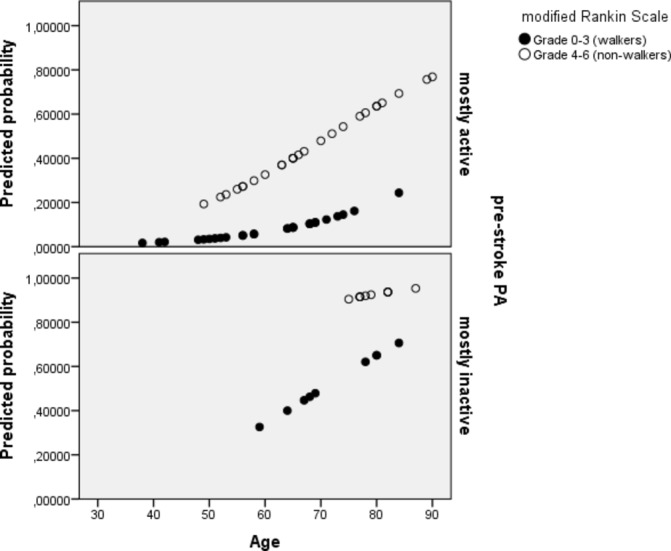

The percentage of total correctly classified for the model was 78.1 with sensitivity 75.0% and specificity of 79.5%. The odds for being mostly inactive 1 year after stroke, increased by 7% for every year of increasing age. The odds for being inactive also increased by 6 times if the participant was not able to walk independently at discharge and by 6.5 times if the participant was already mostly inactive prestroke. Predicted probabilities for this model are presented in figure 2. As seen in figure 2, there were no observations on mostly inactive non-walkers below age 70 years, which means that the predicted probabilities are extrapolated below this age. A separate model including the three significant predictor variables, age, ARAT (instead of mRS) and prestroke PA demonstrated comparable level of correct classification (78.6%).

Figure 2.

Predicted probabilities of being mostly inactive 1 year after stroke. The predicted probability increases with higher age, higher degree of functional dependency and being physically inactive prestroke.

Predicting low PA

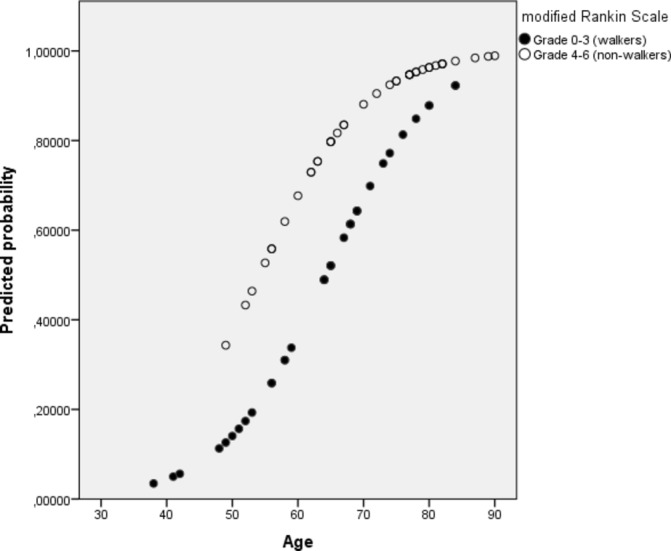

The final model for predicting low PA level included two significant predictor variables: age and functional dependency (mRS) at discharge from stroke unit (table 2b).

The percentage of total correctly classified for the model was 74.0 with sensitivity 77.2% and specificity of 65.0%. The odds of having a low PA level 1 year after stroke increased with 13% for every year of increasing age. The odds of having a low PA level also increased, by 2.6 times if the participant was not able to walk independently at discharge. Predicted probabilities for this model are presented in figure 3. A separate model including the two significant predictor variables, age and ARAT (instead of mRS) demonstrated comparable level of correct classification (75.7%).

Figure 3.

Predicted probability for having low PA 1 year after stroke. The predicted probability increases with higher age and higher degree of functional dependency.

Discussion

Higher age, functional dependency at discharge from stroke unit and being physically inactive prior to stroke all contributed to increase the probability of being physically inactive 1 year after stroke. The probability of having a low PA level after stroke increased with older age and functional dependency at discharge from stroke unit. Findings from this study provide new insights on what factors obtained early after stroke may impact on the PA level at later stages among stroke survivors. This knowledge could be used to identify patients at risk for inactivity or low PA level early after stroke, so that targeted intervention could be offered as part of secondary prevention.

When comparing levels of PA, two different dichotomisations of data (two models) based on different recommendations on PA was used.6 29 The first model aimed to address inactivity as important cut-off for prevention of cardiovascular disease31 and the second to address PA at lower than the recommended level required for prevention of morbidity.6 Age was found to be a significant predictor in both models, but it had a greater impact on the model for identifying those with low PA level. This finding is in concurrence with an earlier study in older adults, where the age was inversely correlated with the amount of moderate-intensity PA, but not with the amount of low-intensity PA.32 Functional dependency, including ability to walk independently or not, was also found as a significant predictor for PA after stroke in both models, which is in concurrence with previous studies.15 21 These findings suggest that, similarly to older adults, age may have an impact on the intensity of PA after stroke but also that the disability level expressed as dependence in walking and daily activities influence the PA level at later stages poststroke. The upper extremity functioning (ARAT) early after stroke was found to have similar effect on the later poststroke PA, as the functional dependency (mRS) at discharge. Functional dependency at discharge and limitation in the upper extremity use early after stroke may both be associated with the stroke severity, but these factors may also mean that the limited function itself after stroke may impact the PA level negatively.15–19 Being mostly inactive prestroke had a significant effect when predicting inactivity at later stage poststroke. However, the level of PA prestroke, low or moderate/high, did not have a significant effect in the model predicting poststroke PA level, which indicates that the level of PA poststroke may to larger degree be affected by other factors, such as the disability level, age and comorbidities.

There has been little interest in investigating which early predictors might influence PA among stroke survivors and most studies on PA look at cross-sectional correlations. A previous longitudinal study,33 investigating physical inactivity after stroke, found significant correlation between time spent upright and degree of independence in activities of daily living and walking at the first weeks after stroke, as well as at 1, 2 and 3 years poststroke. Although these findings reflect merely cross-sectional correlations, they indicate that independence in daily activities and ambulation are important for PA among stroke survivors. In a review comprising people after stroke with ability to walk,15 walking ability, balance and physical fitness were positively associated with PA level. Walking ability in the form of walking speed has further been found to explain some of the variation of PA level among stroke survivors.16 Studies on what stroke survivors experience as barriers to PA have identified physical impairment as one of the main barriers to PA,21 22 yet motor impairment has been found to correlate mainly with walking capacity and energy cost for walking and not with PA level.17 In another study physical capacity, measured by a test for fitness, was found to have a moderate correlation to self-assessed PA.34 In our study, the mRS addressing disability rather than impairment was used28 and although functional disability and motor impairment are correlated, impairment does not fully explain disability among people with stroke.20 Previous studies have not shown significant correlation between age and PA after stroke.15 33 Age has, however, been found to be inversely correlated to PA in healthy populations,12 35 although not as a clear determinant compared with health status or previous PA habits.12 The decline in PA with increasing age does not seem to be linear but exponential in older adults35 and functional outcome has been found to drop steeply in the older ages among people who has had stroke,36 yet most work on PA among stroke survivors have been made in persons aged 65–75 years.15 The present study had no upper limit of age, yet the participants in the study were somewhat younger than the average stroke population in Sweden;26 therefore, the effect of age on PA level in stroke survivors might be slightly underestimated.

Prestroke PA has been found to have a significant impact on functional outcome at acute phase,11 3 months10 19 1 year11 and 2 years after stroke.7 A longitudinal study11 showed that the main differences for functional outcome were found when comparing a subgroup with relatively low PA level, measured as people who walked less than 30 min per day with groups walking for more than 30 min a day. The group with low amount of walking time was more dependent as measured by the mRS and the Barthel Index and had a slower walking speed. These differences were not seen when comparing one group that walked for 30–60 min per day with another group who walked for more than 60 min per day.11 These results are in line with the findings in our study showing that being mostly active, as analysed in the first model, was important for staying active, whereas a higher PA level made no further contribution in predicting a higher PA level poststroke. Prestroke habits of PA may also possibly mean having some knowledge about PA and its beneficial health effects, whereas lack of knowledge and disbeliefs related to PA have been reported as barriers to PA by stroke survivors21 22 and could be a part of the explanation of our finding that prestroke PA level is important for being active after stroke.

The strength of this study was that many clinically important parameters that can be obtained early poststroke were considered as potential predictors for long-term outcome of PA level. It is of clinical importance to identify persons at risk of becoming inactive at an early stage, since PA after stroke may help in preventing secondary complications.4 Furthermore, the dichotomisations for PA level used in the study are clinically relevant and concurrent with recommendations for prevention of morbidity. There are, however, several limitations to this study, including a low number of cases in some subgroups that did not allow inclusion of all potential predictor variables into the regression models. The main outcome variable for PA was an interview based questionnaire.29 30 This type of scale presents with some problems including being at an ordinal level of data and the risk for recall bias.37 There is only a limited number of studies investigating validity of the six-graded scale used in this study.38 The dichotomisation used in the first model between grades 2 and 3 may, however, be directly translated into the original four-grade Saltin-Grimby Scale,29 30 which has been widely used and shown to have a good concurrent validity.38 Self-assessed PA has also been shown to have good predictor value for cardiovascular risk profiles39 as well as for functional outcome after stroke.19 The alternative option for reporting PA is direct measurement, for example, through using accelerometers.37 This option would not have been possible for establishing PA level prior to stroke, but could have been for outcome.

There are several other variables, such as mood, balance scales,40 fear of falling,20 lack of motivation and environmental factors21 that may influence PA after stroke that were not taken into account in the current study. Furthermore, our study based on the SALGOT cohort included only persons with an impaired upper extremity function 3 days poststroke, and the results apply only to those who were followed up at 1 year. Persons without impaired upper extremity might experience other obstacles for being physically active than people with upper limb impairment. Thus, the results from the current study can only be applied to persons showing at least some impairment of the upper extremity early after stroke and other studies are needed to see if the findings in our study may also apply to persons without upper extremity impairment early after stroke.

The present study aimed to identify persons that have a higher risk in becoming inactive after their stroke. The problem of inactivity among people with stroke is well established and recent recommendations have highlighted the challenges in increasing the PA among this group.4 By identifying which individuals who have an increased risk of becoming inactive after their stroke, allows clinicians to identify these persons earlier and so that targeted intervention could be offered as part of secondary prevention.4

Conclusion

Physical inactivity among stroke survivors is a major clinical problem. The present study indicates that persons with a higher age, higher degree of functional dependency early after stroke and a history of inactivity prior to stroke may have an increased risk of being insufficiently active at 1 year poststroke. These results may help to guide clinicians in identifying individuals in need of targeted interventions for reaching an adequate amount of PA; however, these findings need to be validated by other studies to show if the results may be applicable for other groups of stroke survivors. The list of predictor variables identified in this study contribute, but cannot explain all of the variation of PA level among stroke survivors and other predictors need to be further explored.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: OAO, HCP, MAM and KSS contributed to the design of the study concept, in analysis and interpretation of results and in drafting/revising the manuscript for content. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. In addition to this, HCP and MAM performed the acquisition of data. HCP, MAM and KSS obtained funding, OAO performed the statistical analysis and KSS supervised the SALGOT study.

Funding: This study was funded in parts by the Swedish Research Council (VR 20123 70X32212230133), the Norrbacka-Eugenia Foundation, the Foundation of the Swedish National Stroke Association, Promobila, the Swedish Brain Foundation and the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Gothenburg (225-08).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Interested researchers may submit requests for data to the authors (contact ks.sunnerhagen@neuro.gu.se). According to the Swedish regulation (http://www.epn.se/en/start/regulations/), the permission to use data is only for what has been applied for and then approved by the ethical board.

References

- 1. O'Donnell MJ, Xavier D, Liu L, et al. . Risk factors for ischaemic and intracerebral haemorrhagic stroke in 22 countries (the INTERSTROKE study): a case-control study. Lancet 2010;376:112–23. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60834-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lee CD, Folsom AR, Blair SN. Physical activity and stroke risk: a meta-analysis. Stroke 2003;34:2475–81. 10.1161/01.STR.0000091843.02517.9D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wendel-Vos GC, Schuit AJ, Feskens EJ, et al. . Physical activity and stroke. A meta-analysis of observational data. Int J Epidemiol 2004;33:787–98. 10.1093/ije/dyh168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Billinger SA, Arena R, Bernhardt J, et al. . Physical activity and exercise recommendations for stroke survivors: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2014;45:2532–53. 10.1161/STR.0000000000000022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization. Global health risks: mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. Geneva 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6. WHO. Global recommandations on physical activity for health. 2010. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44399/1/9789241599979_eng.pdf (accessed 19 Aug 2015).

- 7. Krarup LH, Truelsen T, Gluud C, et al. . Prestroke physical activity is associated with severity and long-term outcome from first-ever stroke. Neurology 2008;71:1313–8. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000327667.48013.9f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Deplanque D, Masse I, Libersa C, et al. . Previous leisure-time physical activity dose dependently decreases ischemic stroke severity. Stroke Res Treat 2012;2012:1–6. 10.1155/2012/614925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hållmarker U, Åsberg S, Michaëlsson K, et al. . Risk of recurrent stroke and death after first stroke in long-distance Ski race participants. J Am Heart Assoc 2015;4:e002469 10.1161/JAHA.115.002469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stroud N, Mazwi TM, Case LD, et al. . Prestroke physical activity and early functional status after stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2009;80:1019–22. 10.1136/jnnp.2008.170027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ursin MH, Ihle-Hansen H, Fure B, et al. . Effects of premorbid physical activity on stroke severity and post-stroke functioning. J Rehabil Med 2015;47:612–7. 10.2340/16501977-1972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bauman AE, Reis RS, Sallis JF, et al. . Correlates of physical activity: why are some people physically active and others not? Lancet 2012;380:258–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60735-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Trost SG, Owen N, Bauman AE, et al. . Correlates of adults' participation in physical activity: review and update. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2002;34:1996–2001. 10.1097/00005768-200212000-00020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rand D, Eng JJ, Tang PF, et al. . Daily physical activity and its contribution to the health-related quality of life of ambulatory individuals with chronic stroke. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010;8:80 10.1186/1477-7525-8-80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. English C, Manns PJ, Tucak C, et al. . Physical activity and sedentary behaviors in people with stroke living in the community: a systematic review. Phys Ther 2014;94:185–96. 10.2522/ptj.20130175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Danielsson A, Meirelles C, Willen C, et al. . Physical activity in community-dwelling stroke survivors and a healthy population is not explained by motor function only. Pm R 2014;6:139–45. 10.1016/j.pmrj.2013.08.593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Danielsson A, Willén C, Sunnerhagen KS. Physical activity, ambulation, and motor impairment late after stroke. Stroke Res Treat 2012;2012:1–5. 10.1155/2012/818513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rand D, Eng JJ, Tang PF, et al. . How active are people with stroke?: use of accelerometers to assess physical activity. Stroke 2009;40:163–8. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.523621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. López-Cancio E, Ricciardi AC, Sobrino T, et al. . Reported prestroke physical activity is associated with vascular endothelial growth factor expression and good outcomes after stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2017;26:425–30. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Roth EJ, Heinemann AW, Lovell LL, et al. . Impairment and disability: their relation during stroke rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998;79:329–35. 10.1016/S0003-9993(98)90015-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nicholson S, Sniehotta FF, van Wijck F, et al. . A systematic review of perceived barriers and motivators to physical activity after stroke. Int J Stroke 2013;8:357–64. 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2012.00880.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jackson S, Mercer C, Singer BJ. An exploration of factors influencing physical activity levels amongst a cohort of people living in the community after stroke in the south of England. Disabil Rehabil 2016:1–11. 10.1080/09638288.2016.1258437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Alt Murphy M, Persson HC, Danielsson A, et al. . SALGOT--Stroke arm longitudinal study at the University of Gothenburg, prospective cohort study protocol. BMC Neurol 2011;11:56 10.1186/1471-2377-11-56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lyle RC. A performance test for assessment of upper limb function in physical rehabilitation treatment and research. Int J Rehabil Res 1981;4:483–92. 10.1097/00004356-198112000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. . The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007;370:1453–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Asplund K, Hulter Åsberg K, Appelros P, et al. . The Riks-Stroke story: building a sustainable national register for quality assessment of stroke care. Int J Stroke 2011;6:99–108. 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2010.00557.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brott T, Adams HP, Olinger CP, et al. . Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: a clinical examination scale. Stroke 1989;20:864–70. 10.1161/01.STR.20.7.864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. van Swieten JC, Koudstaal PJ, Visser MC, et al. . Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke 1988;19:604–7. 10.1161/01.STR.19.5.604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Grimby G. Physical activity and muscle training in the elderly. Acta Med Scand Suppl 1986;711:233–7. 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1986.tb08956.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mattiasson-Nilo I, Sonn U, Johannesson K, et al. . Domestic activities and walking in the elderly: evaluation from a 30-hour heart rate recording. Aging 1990;2:191–8. 10.1007/BF03323916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ladenvall P, Persson CU, Mandalenakis Z, et al. . Low aerobic capacity in middle-aged men associated with increased mortality rates during 45 years of follow-up. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2016;23:1557–64. 10.1177/2047487316655466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Takagi D, Nishida Y, Fujita D. Age-associated changes in the level of physical activity in elderly adults. J Phys Ther Sci 2015;27:3685–7. 10.1589/jpts.27.3685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kunkel D, Fitton C, Burnett M, et al. . Physical inactivity post-stroke: a 3-year longitudinal study. Disabil Rehabil 2015;37:304–10. 10.3109/09638288.2014.918190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lindahl M, Hansen L, Pedersen A, et al. . Self-reported physical activity after ischemic stroke correlates with physical capacity. Adv Physiother 2008;10:188–94. 10.1080/14038190802490025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Buchman AS, Wilson RS, Yu L, et al. . Total daily activity declines more rapidly with increasing age in older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2014;58:74–9. 10.1016/j.archger.2013.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Knoflach M, Matosevic B, Rücker M, et al. . Functional recovery after ischemic stroke--a matter of age: data from the Austrian Stroke Unit Registry. Neurology 2012;78:279–85. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31824367ab [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hagströmer M, Oja P, Sjöström M. Physical activity and inactivity in an adult population assessed by accelerometry. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2007;39:1502–8. 10.1249/mss.0b013e3180a76de5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Grimby G, Börjesson M, Jonsdottir IH, et al. . The "Saltin-Grimby Physical Activity Level Scale" and its application to health research. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2015;25(Suppl 4):119–25. 10.1111/sms.12611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Thune I, Njølstad I, Løchen ML, et al. . Physical activity improves the metabolic risk profiles in men and women: the Tromsø Study. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:1633–40. 10.1001/archinte.158.15.1633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Alzahrani MA, Dean CM, Ada L, et al. . Mood and balance are associated with free-living physical activity of people after stroke residing in the community. Stroke Res Treat 2012;2012:1–8. 10.1155/2012/470648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-016369supp001.pdf (282.9KB, pdf)