Abstract

The intracellular fibroblast growth factors (iFGF/FHFs) bind directly to cardiac voltage gated Na+ channels, and modulate their function. Mutations that affect iFGF/FHF-Na+ channel interaction are associated with arrhythmia syndromes. Although suspected to modulate other ionic currents, such as Ca2+ channels based on acute knockdown experiments in isolated cardiomyocytes, the in vivo consequences of iFGF/FHF gene ablation on cardiac electrical activity are still unknown. We generated inducible, cardiomyocyte-restricted Fgf13 knockout mice to determine the resultant effects of Fgf13 gene ablation. Patch clamp recordings from ventricular myocytes isolated from Fgf13 knockout mice showed a ~25% reduction in peak Na+ channel current density and a hyperpolarizing shift in steady-state inactivation. Electrocardiograms on Fgf13 knockout mice showed a prolonged QRS duration. The Na+ channel blocker flecainide further prolonged QRS duration and triggered ventricular tachyarrhythmias only in Fgf13 knockout mice, suggesting that arrhythmia vulnerability resulted, at least in part, from a loss of functioning Na+ channels. Consistent with these effects on Na+ channels, action potentials in Fgf13 knockout mice, compared to Cre control mice, exhibited slower upstrokes and reduced amplitude, but unexpectedly had longer durations. We investigated candidate sources of the prolonged action potential durations in myocytes from Fgf13 knockout mice and found a reduction of the transient outward K+ current (Ito). Fgf13 knockout did not alter whole-cell protein levels of Kv4.2 and Kv4.3, the Ito pore-forming subunits, but did decrease Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 at the sarcolemma. No changes were seen in the sustained outward K+ current or voltage-gated Ca2+ current, other candidate contributors to the increased action potential duration. These results implicate that FGF13 is a critical cardiac Na+ channel modulator and Fgf13 knockout mice have increased arrhythmia susceptibility in the setting of Na+ channel blockade. The unanticipated effect on Ito revealed new FGF13 properties and the unexpected lack of an effect on voltage-gated Ca2+ channels highlight potential compensatory changes in vivo not readily revealed with acute Fgf13 knockdown in cultured cardiomyocytes.

Keywords: Fibroblast growth factor homologous factors, FGF13, Cardiac conditional knockout mice, ventricular tachyarrhythmias, Na+ channel, K+ channel

1. Introduction

The intracellular fibroblast growth factors (iFGFs), also called fibroblast growth factor homologous factors (FHFs), are a subfamily of fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) and comprise four members: FGF11–FGF14, each with alternative splice variants. iFGF/FHFs lack signal sequences, cannot be secreted, do not bind to FGF receptors, and do not function as growth factors[1–4]. Instead, iFGF/FHFs remain intracellular, where they bind and modulate the function and trafficking of voltage-gated Na+ channels in the mammalian brain and heart[5–14]. Disease mutations and knockout animals highlight the physiological roles of iFGF/FHFs. Knockout of the neuronally-restricted Fgf14 and human missense mutations in FGF14 lead to spinocerebellar ataxia and cognitive deficits[15–22]. We showed that a loss-of-function mutation in FGF12 that eliminates Na+ channel modulation is associated with Brugada syndrome, an inherited cardiac arrhythmia[23], and a mutation in the cardiac Na+ channel gene SCN5A that affects FGF12 interaction and NaV1.5 channel function in ventricular myocytes leads to a life-threatening arrhythmia syndrome[24].

In addition to their Na+ channel regulatory roles, we discovered that iFGF/FHFs are capable of modulating voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, both in heart[25] and in brain[26]. Further, analysis of action potential parameters after acute Fgf13 knockdown in murine ventricular cardiomyocytes suggested that cardiac iFGF/FHFs may have even broader effects on electrical activity. The integrated in vivo roles of cardiac iFGF/FHFs, however, have not previously been reported, and whether compensatory changes in vivo after Fgf13 knockout lead to different consequences than FGF13 knockdown in cultured cardiomyocytes is not known. Reports of the contrasting consequences of iFGF/FHFs on specific neuronal Na+ channels in different models systems (e.g., heterologous expression vs. mouse knockout) [7, 27] highlight the necessity of studying iFGF/FHFs in an in vivo model. Therefore, we generated an Fgf13 conditional knockout mouse line and analyzed the consequences on cardiac electrical activity. Our findings provide novel insight into critical roles of iFGF/FHFs in regulating cardiac rhythm and reveal unexpected contributions of iFGF/FHFs in heart.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Animals

Animals were handled according to National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. This study was approved by Hebei Medical University Animal Care and Welfare Committee and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Duke University (protocol #A292-13-11).

2.2 Generation of FGF13-loxP mice and FGF13 cardiac conditional knockout mice

All genetically modified mice were maintained on a C57BL/6 genetic background. Floxed Fgf13 mice (Fgf13fl/fl) were generated in collaboration with Beijing Biocytogen, Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) by flanking exon 3 of the mouse Fgf13 gene with two loxP sites (Fig. 1). One loxP sequence was inserted 322 bp upstream from exon 3, and an FRT-flanked Neo expression cassette containing another loxP site was inserted 226 bp downstream from exon 3 to enable positive selection (Fig. 1A). The resulting targeting vector was transfected into mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells. The ES cell colonies were then selected with G418, and screened via PCR and Southern blot (Fig. 1B). Chimeric mice were generated by microinjecting Fgf13fl-neo/+ ES cells into C57BL/6 blastocysts. The F1 Fgf13fl-neo/+ mice were crossed with Flp mice to remove the Neo cassette in the germ line and Fgf13fl/+ offspring were genotyped via PCR (Fig. 1C). To generate cardiac-specific, inducible knockout mice, Fgf13fl/f mice were crossed with Myh6-MCM (MerCreMer; #005657, Jackson Laboratory) mice, which have an alpha-myosin heavy chain (Myh6) promoter directing expression of a tamoxifen-inducible Cre recombinase. Hemizygous male Fgf13fl/Y; Myh6-MCM+/− were subsequently bred with heterozygous female Fgf13fl/+ mice to generate homozygous female Fgf13fl/fl; Myh6-MCM+/− knockout mice. 6–8 week-old male hemizygous or female homozygous knockout mice (KO), no floxed Myh6-MCM controls (Cre), and wild-type controls (WT) were injected with 30mg/kg tamoxifen (Sigma) intraperitoneally for 3 consecutive days to induce Fgf13 deletion. Mice were examined at least one week after recovery from tamoxifen induction.

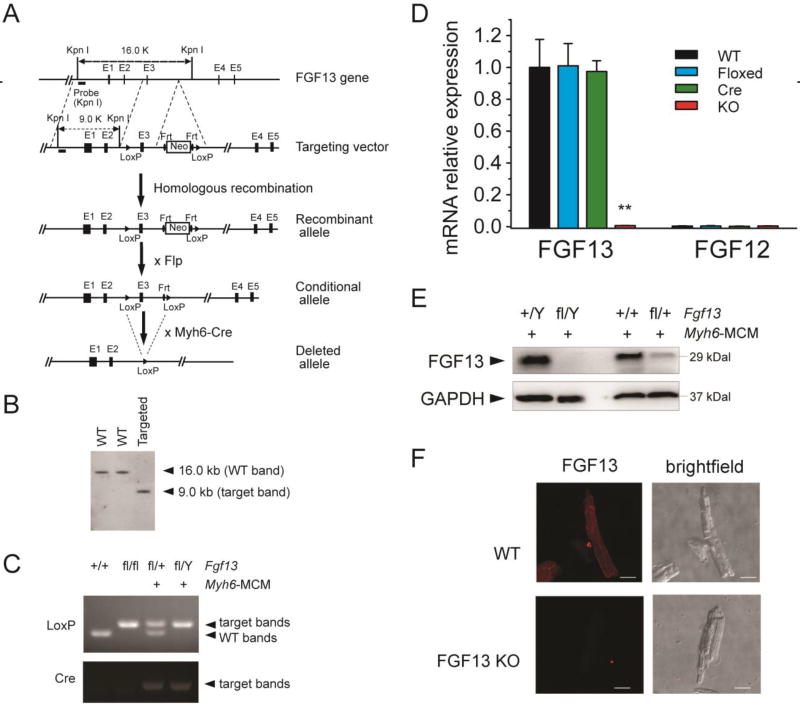

Fig. 1.

Generation of FGF13 cardiac conditional knockout mice using Cre-LoxP system. (A) Structure of the mouse Fgf13 genomic locus (line 1; black boxes represent exons); targeting vector to introduce a neomycin selection cassette and floxed exon 3 (line 2); and the recombined Fgf13 allele (line 3). Crossing with a FLP deleter yields a conditional allele (line 4). Subsequent cross with Myh6-Cre generates a tamoxifen-inducible cardiac-specific KO (line 5). (B) Southern blot of genomic DNA from targeted ES cell clone and two wild-type ES cell clones, hybridized with 5’ genomic probes. (C) PCR genotyping of wild-type (+/+), homozygous flox (fl/fl), heterozygous (fl/+; Myh6-MCM+) and hemizygous (fl/Y; Myh6-MCM+) FGF13 mice using genomic DNA prepared from tail biopsies. (D) RT-qPCR of FGF13 and FGF12B in Fgf13fl/Y; Myh6-MCM+/− (KO) compared to wild type (WT), floxed FGF13 (Floxed), and Myh6-MCM (Cre) showing ~99% reduction of FGF13 mRNA and lack of compensation by FGF12B. The RTqPCR was performed one week after tamoxifen induction. Ct values were corrected with GAPDH and normalized to FGF13 in WT. **indicates p<0.01 compared to WT. n=3. (E) Representative immunoblots of FGF13 protein expression in ventricular myocytes from Myh6-MCM, hemizygous, and heterozygous Fgf13 KO mice. (F) Confocal images of FGF13 immunocytochemistry (left panels) with corresponding bright-field images (right panels) in WT (upper panels) and Fgf13 KO (lower panels) mice. Scale bar, 25 µm.

2.3 Cardiomyocyte isolation

Cardiomyocytes were isolated from wild type or mutant mice as previously described[5]. In brief, cardiomyocytes were isolated from 6- to 8-week-old mice. The hearts were removed and perfused retrogradely on a Langendorff apparatus for approximately 10 minutes with perfusion solution containing Minimal Essential Medium (MEM), Joklik modified (Sigma, M8028) with the following additions (all Sigma, in mmol/L): KHCO3 10, HEPES 10, taurine 30, L-carnitine 2, creatine 2, D-glucose 20 and collagenase type 2 (150 units/ml, Worthington). The heart was removed from perfusion when soft and white. Left and right ventricles were minced into small pieces and then allowed to digest for another 10 minutes in enzyme solution with frequent trituration at 37 °C. The solution was filtered through sterile 210 µm nylon and centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 3 minutes to pellet cells. The cells were resuspended in perfusion solution with bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma) at 5 mg/ml. Calcium tolerance was performed by gradually adding CaCl2 to a final concentration of 1 mM. Rod-shaped, striated cells were used for electrophysiological recording and image collection.

2.4 Electrophysiology

Na+ currents, Ca2+ currents and outward K+ currents were recorded using the whole-cell voltage-clamp technique as previously described[5, 25, 28]. Cardiac action potentials were recorded in current clamp as previously described[23].

Na+ currents (INa) were recorded using the whole-cell voltage-clamp technique as previously described[5]. Cardiac action potentials were recorded in current clamp as previously described. In brief, patch pipettes were fabricated from borosilicate glass (Warner Instrument Co.) by a P-97 Flaming-Brown micropipette puller (Sutter Instruments) and fire polished by using a microforge (MF 830, Narishige, Japan). Pipette resistance was between 1 and 2 MΩ. Voltage-clamp experiments were performed with an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments). All recordings were performed at room temperature (20–22 °C). INa was recorded in bath solution containing (in mM, from Sigma): NaCl 20, MgCl2 1, CaCl2 1, HEPES 20, CsCl 55, CsOH 10, glucose 10, 4-aminopyridine 2, CdCl2 0.5, TEA-Cl 50, pH 7.35 (adjusted with HCl). The pipette solution contained the following (in mM, from Sigma): NaCl 5, CsF 135, EGTA 10, MgATP 5, HEPES 5, TEA-Cl 20, pH 7.35 (adjusted with CsOH). Osmolarity was adjusted to 310 mOsm with sucrose for all solutions. Recordings were filtered at 5 kHz and digitally sampled at 40 kHz. The pulse protocol cycle time was 3 seconds to ensure full Na+ channel recovery. Seal resistances exceeded 8 GΩ. Whole-cell membrane capacitance was calculated by integrating the capacitive transient elicited by a 10 mV voltage step from −120 mV to −130 mV. Junction potential and pipette capacitance were corrected, and whole-cell capacitance and series resistance were ~80% compensated to assure that the command potential was reached within microseconds with a voltage error < 2 mV. The leak current was small, and in most experiments, no leak correction was necessary. To minimize time-dependent drift in gating parameters, all protocols were initiated 2–5 minutes after whole-cell configuration was obtained. Current amplitude data for each cell were normalized to its cell capacitance (current density, pA/pF). To determine the voltage-dependence of steady-state activation, currents were elicited by a 40 ms pulse from a holding potential of −120 mV to test potentials between −100 mV and +60 mV in 5 mV increments. The sodium conductance (G) was calculated by dividing the peak current for each voltage step by the driving force (Vm−Vrev) then normalized to the peak conductance (Gmax). Data were fitted with the Boltzmann relationship, G/Gmax=1/{1+exp[(V1/2−Vm)/k]} in which V1/2 is the voltage at which half of NaV1.5 channels is activated, k is the slope factor and Vm is the membrane potential. Standard two-pulse protocols were used to generate the steady-state inactivation curves: from the holding potential −120 mV, cells were stepped to 500-ms preconditioning potentials varying between −130 mV and −10 mV (prepulse), followed by a 20 ms test pulse to −30 mV. Currents (I) were normalized to Imax and fit to a Boltzmann function of the form I/Imax=1/{1+exp[(Vm−V1/2)/k]} in which V1/2 is the voltage at which half of NaV1.5 channels is inactivated, k is the slope factor and Vm is the membrane potential. Curve fitting and data analysis were performed using Clampfit 10.2 software (Axon Instruments) and Origin 8 (Originlab Corporation).

Ca2+ currents (ICa) were recorded using the whole-cell voltage-clamp technique as previously described[25]. In brief, cells were recorded at 20–22°C using whole-cell patch-clamp from acutely isolated Cre or Fgf13 KO cardiomyocytes. Patch pipettes (1–2 MΩ) contained (in mM, from Sigma): CsOH•H2O 70, aspartic acid 80, CsCl 40, NaCl 10, MgCl2 2, HEPES 10, EGTA 10, MgATP 5,Na2GTP 0.2, Na2-phosphocreatine 4, pH 7.3 adjusted with CsOH. Cells were initially bathed in Tyrode solution containing (in mM, from Sigma): NaCl 140, KCl 5.4, CaCl2 1, MgCl2 1, HEPES 5, glucose 10, pH 7.3 adjusted with NaOH. Once the cell was ruptured, solution was quickly changed to recording solution containing (in mM, from Sigma): Tetraethylammonium chloride 140, HEPES 5, KCl 5.4, CaCl2 1, MgCl2 1, 4-aminopyridine 2, D-glucose 10, adjusted to pH 7.4. To measure current density and voltage-dependence of steady state activation, cells were held from a holding potential of −80 mV and stepped from −60 mV to +40 mV for 300ms in 10 mV increments. Steady state inactivation was performed using a standard two-pulse protocol: from a holding potential of −80mV, Vm was stepped for 1 s to a preconditioning potential (−80 to +30 mV), followed by a 100ms test pulse to 0 mV. Data were sampled at 25 kHz and filtered at 5 kHz.

K+ currents were recorded using the whole-cell voltage-clamp technique as previously described[28]. In brief, cells were held from a holding potential of −50 mV and stepped from −40 mV to +50 mV for 2000ms in 10 mV increments. For recordings of voltage-gated K+ currents, the bath solution contained (in mM, from Sigma): NaCl 136, KCl 4, MgCl2 2, CaCl2 1, HEPES 10 and glucose 10, Tetrodotoxin (TTX) 0.02 and CdCl2 0.5 (pH 7.4; 300 mOsm). Recording pipettes contained (in mM, from Sigma): KCl 135, K2ATP 5, EGTA 10, HEPES 10 and glucose 5 (pH 7.2; 310 mOsm). Peak currents at each test potential were measured as the difference between the maximal outward current amplitudes and the zero current level. The decay phases of the currents evoked during long (2 s) depolarizing voltage steps to test potentials between −40 and +50 mV from a holding potential of −50 mV were fitted by the sum of two exponentials using the following expressions: y(t)= A1*exp(−t/τ1)+A2*exp(−t/τ2) +Asus, where t is time, τ1 and τ2 are the time constants of decay and A1 and A2 are the amplitudes of two inactivating current components: the rapidly inactivating, transient outward K+ current (Ito, fast); and a slowly inactivating, transient outward K+ currents (Ik, slow), respectively. Asus is the amplitude of the steady state, noninactivating component of the total outward K+ current (IKsus). For all fits, time zero was set at the peak of the outward current.

Cardiac action potentials were recorded in current clamp as previously described[23]. In brief, perforated patch with 400 nM amphotericin B (Sigma) was performed using the following internal solution (in mM, from Sigma) KCl 110, NaCl 5, MgATP 5, Na2-phosphocreatine 5, Na2GTP 1, HEPES 10, pH 7.3 and Tyrode extracellular solution. Cells were stimulated with current injections at 1Hz at 1.5× threshold to induce action potentials recorded with 25 kHz sampling frequency.

2.5 Surface and telemetric Electrocardiogram (ECG) recording

Mice were lightly anesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane and maintained on a warm platform. Two-lead surface ECGs were obtained by using limb electrodes. Data were amplified and recorded with BIOPAC amplifier (Model:MP150, ECG100C, Biopac Instrument Inc., Goleta, CA) and AcqKnowledge program (Biopac Instrument Inc., Goleta, CA). Flecainide (20 mg/kg, Sigma) was administered by intraperitoneal injection and the ECG was continuously recorded before and 30 minutes after injection. This flecainide dose has been used previously[29, 30]. Telemetric analysis of ECG was performed on the implantable telemetry system (DSI, St. Paul, MN). P wave duration, PR interval, and QRS duration were measured as previously described[30]. Ten measures of each ECG interval in limb leads were made for each mouse.

2.6 Quantitative real-time RT-PCR, Immunocytochemistry and Western Blotting

Methods for RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, quantitative real-time RT-PCR, immunocytochemistry, and western blotting have been previously described[5]. In brief, total RNA was extracted from adult mouse heart after heart tissue was collected, weighed, and homogenized at 4 °C using RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), following manufacturer's instructions. The concentration of total RNA for each sample was determined by Nanodrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). The integrity of the extracted RNA was confirmed by electrophoresis under denaturing conditions. Reverse transcription (RT) was performed using iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad) for synthesis of single-stranded cDNA library according to manufacturer's protocol. qPCR was performed using the iCycler iQ Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). Each sample was run in triplicates. Three controls aimed at detecting DNA contamination in the RNA samples or during the RT or qPCR reactions were always included: an RT mixture without reverse transcriptase, an RT mixture including the enzyme reverse transcriptase but no RNA, and a water only control (reaction mixture with water instead of the cDNA template). Primer pairs for the amplification of FGF12B and FGF13 were used as previously described[5]. PCR products were visualized on a 1.5% agarose gel. The data were collected and analyzed using iCycler Software (Bio-Rad). GAPDH was used as internal control. Relative quantification was performed using the comparative threshold (CT) method (ΔΔCT) after determining the CT values for the reference (GAPDH) and target genes (FGF12B, FGF13 isoforms) in each sample set.

For immunoblotting, whole cell lysates were prepared by directly extracting cells in a lysis buffer containing 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 1% Triton, 0.5% NP40 and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Following centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 10 minutes, supernatants were collected and protein concentration quantified using a BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo). About 20 µg of protein were dissolved with 4× LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen) and separated on NuPAGE 4–12% Bis–Tris gels (Invitrogen), then electro-transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Thermo Scienitific) for 90 minutes at 100 V. Membrane were blocked with 5% non-fat milk/TBST for 1.5 h at room temperature and incubated with the primary antibody against FGF13 (Yenzym), Kv4.2 (Alomone labs), Kv4.3 (Alomone labs), Transferrin Receptor (Invitrogen) and GAPDH (Proteintech) in 5% non-fat milk/TBST overnight at 4 °C. The blots were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence and images were captured by using Kodak Image Station 4000 R and quantified using Kodak MI SE software. GAPDH was used as internal control.

Cell surface protein quantification was performed with a biotinylation assay in which cell surface protein isolation was performed using the Pierce cell surface protein isolation kit (Thermo Scientific) as in our previous study[5]. Briefly, cardiomyocytes were washed with ice-cold PBS and labeled with EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-SS-Biotin for 30 minutes on rocking platform at 4 °C. The cells were subsequently lysed in buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors for 30 minutes on ice followed by centrifuge at 1000×g at 4 °C for 2 minutes. Biotin-labeled cell surface proteins were collected by NeutrAvidin Agarose in a spin column and eluted with sample buffer containing 62.5 mmol/L Tris-Hcl (pH 6.8), 1% SDS, 10% glycerol and 50 mmol/L dithiothreitol into a collection tube. The eluent was heated for 5 minutes at 95 °C and bromophenol blue was added. The concentration of the isolated plasma membrane protein was determined and protein levels of Kv4.2, Kv4.3 and transferrin receptor were detected by Western blot with transferrin receptor as a control for effective isolation of cell surface proteins.

For immunocytochemistry, cardiomyocytes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 15 minutes at room temperature (RT). Cells were washed 3 times with PBS and then permeabilized with 0.1% triton X-100 for 10 minutes at RT. To block non-specific antibody binding, cells were incubated 10% goat serum in PBS (blocking buffer) for 30–60 minutes at RT. Cells were then incubated overnight with a custom FGF13 antibody (Yenzym) in blocking buffer at 4 °C. After washing three times with blocking buffer, cells were stained with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 hour at RT. As controls for specificity, the primary antibody was co-incubated with the peptide used for immunization or cells were incubated with secondary antibody only. Coverslips were mounted on slides using Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories). All images were collected on a Leica inverted confocal microscope (Model: SP5, Wetzlar, Germany) with a Leica 40× dry objective. Images were imported into Photoshop (Adobe) for processing.

2.7 Statistical analysis

Results are presented as mean ± SE. Statistical significance of differences between groups was assessed using either one-way ANOVA or a two-tailed Student’s t test. * indicates p<0.05, ** indicates p <0.01.

3. Results

3.1 Generation of cardiomyocyte-restricted FGF13 conditional knockout mice

To evaluate the roles of FGF13 on cardiac function in vivo, we generated inducible, cardiac-specific Fgf13 knockout mice. The murine Fgf13 gene is located on the X chromosome, and spans approximately 72.3 kb. The gene has four invariant exons (exons 2–5) preceded by four alternatively spliced exons that generate an isoform-specific exon 1. To generate the conditional FGF13-floxed (Fgf13fl/fl) allele in mice, exon 3 was chosen as the target for conditional deletion by insertion of flanking loxP sites. Cre-mediated excision of exon 3 results in a frameshift within exon 4 and predicted early termination of protein translation (Fig. 1A). The targeting vector was transfected into mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells and ES cell colonies were screened via Southern blot (Fig. 1B). The F1 female Fgf13fl-neo/+ mice were crossed with Flp deleter mice to remove the neomycin cassette in the germ line. Conditional female heterozygous Fgf13fl/+ or male hemizygous Fgf13fl/Y offspring were genotyped by PCR (Fig. 1C) and subsequently intercrossed to generate homozygous Fgf13fl/fl knockout mice. The floxed FGF13 mice were born in the expected Mendelian ratio, appeared normal, and were fertile. FGF13 expression in the floxed mice, analyzed by qRT-PCR, was comparable to levels in wild-type mice (Fig. 1D).

To achieve cardiac-specific FGF13 deletion, mice with floxed Fgf13 alleles were crossed with Myh6-MerCreMer (Myh6-MCM) mice, in which the alpha myosin heavy chain promoter drives expression of tamoxifen-inducible Cre recombinase in cardiac ventricles[31]. Fgf13fl/Y;Myh6-MCM+/− (Fgf13−/Y) and Fgf13fl/fl;Myh6-MCM+/− (Fgf13−/−), which are collectively denoted “knockout” (Fgf13 KO) mice, Myh6-MCM Cre controls (Cre), and wild type (WT) controls were induced with tamoxifen at 6–8 weeks of age. To confirm FGF13 deletion in the heart, qPCR and Western blot analyses were performed on isolated mRNA or cardiac tissue lysates from WT, Cre, and Fgf13 KO mice at least one week after recovery from tamoxifen induction. Fgf13 transcript levels were significantly reduced by ~99% in Fgf13 KO mice compared to WT or Cre controls (Fig. 1D). Importantly, transcript levels of Fgf12 in KO were not affected, confirming the efficacy and specificity of knockout, and also suggesting a lack of FGF12 compensation (Fig. 1D). By Western blot, loss or reduction of the 29 kDa FGF13 signal was observed only in the hearts of Fgf13−/−, Fgf13−/Y, or Fgf13+/− mice (Fig. 1E). Further, immunocytochemistry of acutely isolated cardiomyocytes showed absence of FGF13 staining in Fgf13 KO compared with WT myocytes (Fig. 1F). Taken together, the above data demonstrated efficient, inducible deletion of FGF13 from cardiac myocytes.

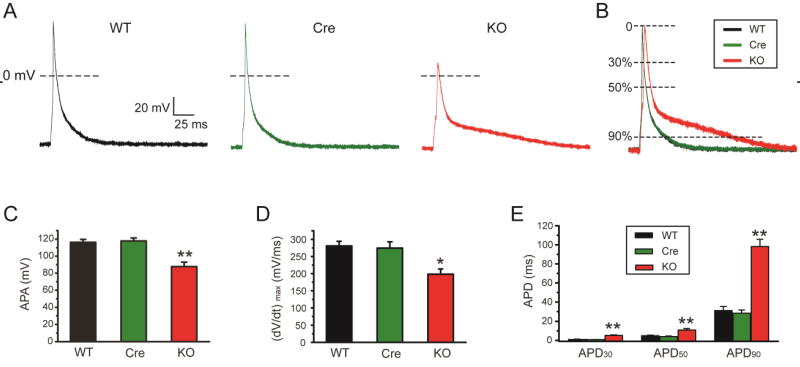

3.2 Deletion of FGF13 affects the ventricular action potential

To determine the functional consequences of FGF13 deletion on cardiac electrical activity at the cellular level, we recorded action potentials in ventricular cardiomyocytes isolated from WT, Cre and Fgf13 KO mice (Fig. 2A and B). Examination of female homozygous KO and male hemizygous KO revealed no differences for the parameters measured in this study, so data for both are combined. Consistent with our observation after FGF13 knockdown in cultured ventricular myocytes[23], resting membrane potential was not different among the groups (−81.6±1.2 mV, −81.3±0.9 mV and −83.1±0. 8 mV, respectively, p>0.05), but the maximal velocity of phase 0 (dV/dtmax) was markedly slowed (280.8±42.7 V/s, 274.7±55.0 V/s and 198.4±48.3 V/s for WT, Cre and Fgf13 KO, respectively, p<0.05) and the action potential amplitude was significantly reduced in the Fgf13 KO (116.3±3.4 mV, 117.8±3.5 mV and 87.7±5.2 mV for WT, Cre and Fgf13 KO, respectively, p<0.05) (Fig.2 C and D). Those data suggested that the Na+ current was altered by knockout of Fgf13. Further, measurement of the action potential duration (APD) showed a marked increase in Fgf13 KO (1.2±0.1 ms, 1.1±0.1 ms and 5.3±0.5 ms for APD30 in WT, Cre and Fgf13 KO, respectively, p<0.05; 4.9±0.6 ms, 4.0±0.6 ms and 10.9±1.6 ms for APD50 in WT, Cre and Fgf13 KO, respectively, p<0.05; 31.1±4.2 ms, 28.3±3.4 ms and 98.2±7.6 ms for APD90 in WT, Cre and Fgf13 KO, respectively, p<0.01) (Fig. 2E), suggesting that some other ion channels might be affected by Fgf13 KO.

Fig. 2.

Action potentials were altered in FGF13 cardiac-specific knockout mice. (A) Representative action potential traces recorded in WT, Myh6-MCM (Cre) and Fgf13 KO (KO) mice. (B) Normalized and superimposed representative action potential traces from A, (C–E) Action potential peak amplitude (APA) (C), maximal velocity of phase 0 (dV/dtmax) (D), and action potential duration (APD) at 30, 50, and 90% repolarization (E) in WT, Cre, and Fgf13 KO mice. *indicates p<0.05 **indicates p<0.01 versus WT, n=8, 8, and 14 cells for WT, Cre and KO mice, respectively (N=3 mice per group).

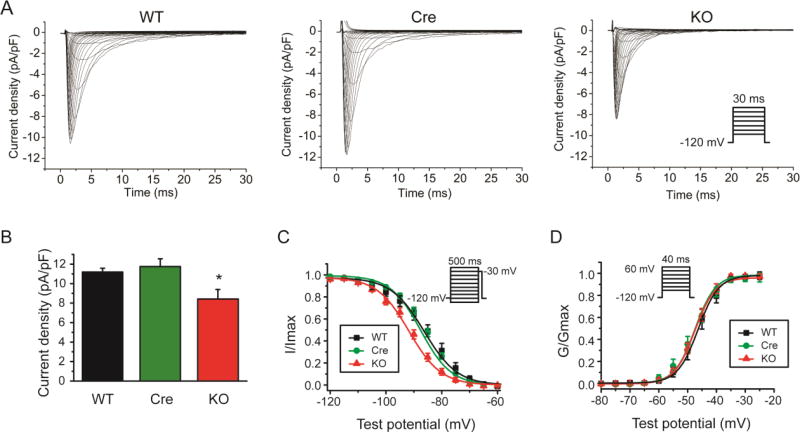

3.3 Deletion of FGF13 affects Na+ channel function

To assess the ionic mechanisms contributing to the observed changes in the action potential, we first tested whether cardiac-specific Fgf13 KO affected Na+ currents in isolated ventricular cardiomyocytes using the patch-clamp technique in whole cell configuration. Cell capacitances were similar among WT, Cre, and Fgf13 KO groups (Table 1). Na+ current density was reduced (by ~25%) in Fgf13 KO mice compared to current density measured in the WT and Cre mice (Fig. 3A and B). The V1/2 of steady-state inactivation, as determined using a standard double-pulse protocol, was hyperpolarized (−86.3±2.2 mV, −87.6±1.1 mV and −91.7±1.6mV for WT, Cre, and Fgf13 KO, respectively; Fig. 3C and Table 1). The V1/2 for activation was unaffected (−46.3±0.8 mV, −47.5±0.5 mV and −47.5±0.7 mV for WT, Cre, and Fgf13 KO, respectively; Fig. 3D and Table 1). We also found that the recovery of Na+ currents from fast inactivation was delayed in Fgf13 KO mice (Supplemental Fig. 1). These findings in Fgf13 KO mice are consistent with a previous report of silencing FGF13 by shRNA in cultured mouse ventricular myocytes[5], and provide a likely mechanism for the reduced Na+ current density and the reduction in action potential amplitude and dV/dtmax.

Table 1.

Summary of INa patch clamp data

| WT | Cre | FGF13 KO | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cm (pF) | 146.8±10.9 (10) | 147.7±9.5(10) | 144.3±8.1(12) |

| Rs (MΩ) | 6.3±0.5(10) | 6.4±0.3(10) | 6.4 ±0.4(12) |

| INa-peakdensity (pA/pF) | 11.2±0.4(10) | 11.8±0.8(10) | 8.4±1.0*(12) |

| V1/2 of activation (mV) | −46.3±0.8(10) | −47.5±0.5(10) | −47.5±0.7(12) |

| k of activation (mV) | 3.6±0.4(10) | 5.5±0.2(10) | 3.5±0.2(12) |

| V1/2 of inactivation (mV) | −86.3±2.2(10) | −87.6±1.1(10) | −91.7±1.6*(12) |

| K of inactivation (mV) | 5.9±0.5(10) | 5.4±0.2(10) | 5.7±0.3*(12) |

The number of cells analyzed for each parameter is provided in parentheses.

indicates p<0.05, compared to WT control.

Fig. 3.

Conditional knockout of FGF13 reduced Na+ currents in ventricular cardiomyocytes. (A) Exemplar Na+ current traces elicited by 30-ms depolarizing pulses to test potentials between −100 mV and 60 mV from a holding potential of −120 mV at 5-mV increments (interpulse interval, 3 seconds). Inset shows schematic of the voltage clamp protocol. (B) Peak Na+ current density measured at −30 mV in WT, Myh6-MCM (Cre), and Fgf13 KO (KO) mice. (C) Voltage dependence of steady-state inactivation in WT, Cre, and Fgf13 KO mice. (D) Voltage dependence of steady-state activation in WT, Cre, and Fgf13 KO mice. *indicates p<0.05 compared to WT; n=10,10,12 cells for WT, Cre, and KO mice, respectively (N=3 mice per group).

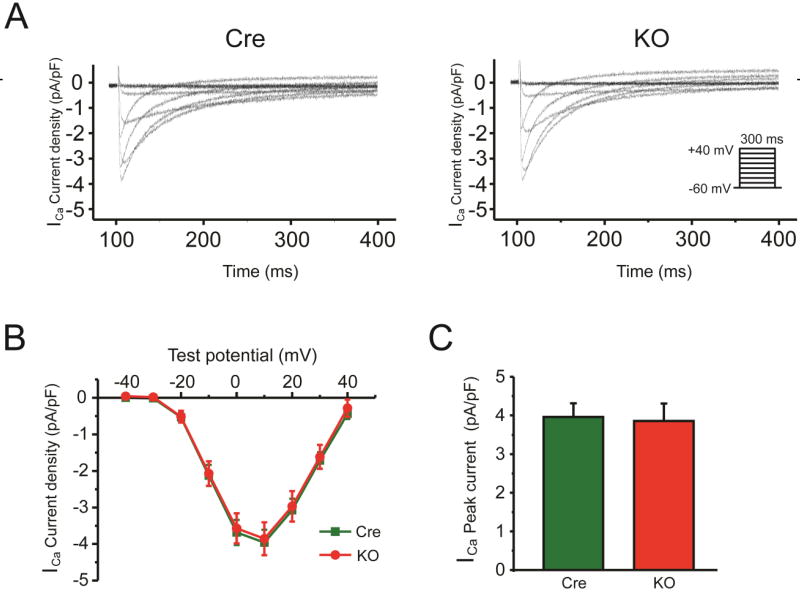

3.4 Deletion of FGF13 reveals new candidate targets of FGF13 modulation

The increase in APD in the Fgf13 KO mice was unexpected, since we previously found a reduction in APD50 after FGF13 knockdown in cultured adult ventricular myocytes. We had attributed the shortened APD to an observed reduction in voltage-gated Ca2+ current density in those cultured ventricular myocytes. We thus investigated effects upon voltage-gated Ca2+ currents in Fgf13 KO cardiomyocytes and observed no difference in current amplitude compared to the Cre control mice (4.0±0.4 pA/pF and 3.9±0.5 pA/pF, respectively, p>0.05) (Fig. 4A, B, C and Table 2). The contrasting effects on Ca2+ currents in FGF13 knockdown vs. Fgf13 KO suggested compensatory changes in vivo that did not manifest in the knockdown setting.

Fig. 4.

Conditional knockout of FGF13 did not affect Ca2+ currents in ventricular cardiomyocytes. (A) Exemplar Ca+ current (ICa) traces elicited by 300-ms depolarizing pulses to test potentials between −60 mV and 40 mV from a holding potential of −80 mV at 10-mV increments. Inset shows schematic of the voltage clamp protocol. (B) Summarized ICa current-voltage relationship for Myh6-MCM (Cre) and Fgf13 KO (KO) mice. (C) Peak ICa densities at +10mV are 4.0±0.4 pA/pF (n=13) for Cre and 3.9±0.5 pA/pF (n=9) for KO, (N=3 mice per group).

Table 2.

Summary of ICa patch clamp data

| Cre | FGF13 KO | |

|---|---|---|

| ICa-peak density (pA/pF) | −4.0 ± 0.4 (13) | −3.9 ± 0.5 (9) |

| V1/2 of activation (mV) | −4.2 ± 1.4 (13) | −3.3 ± 1.6 (8) |

| k of activation (mV) | 6.0± 0.2 (13) | 6.6±0.2 (8) |

| V1/2 of inactivation (mV) | −23.1±1.3 (7) | −24.3±1.3 (8) |

| K of inactivation (mV) | 3.8±0.2 (7) | 3.9±0.2 (8) |

The number of cells analyzed for each parameter is provided in parentheses.

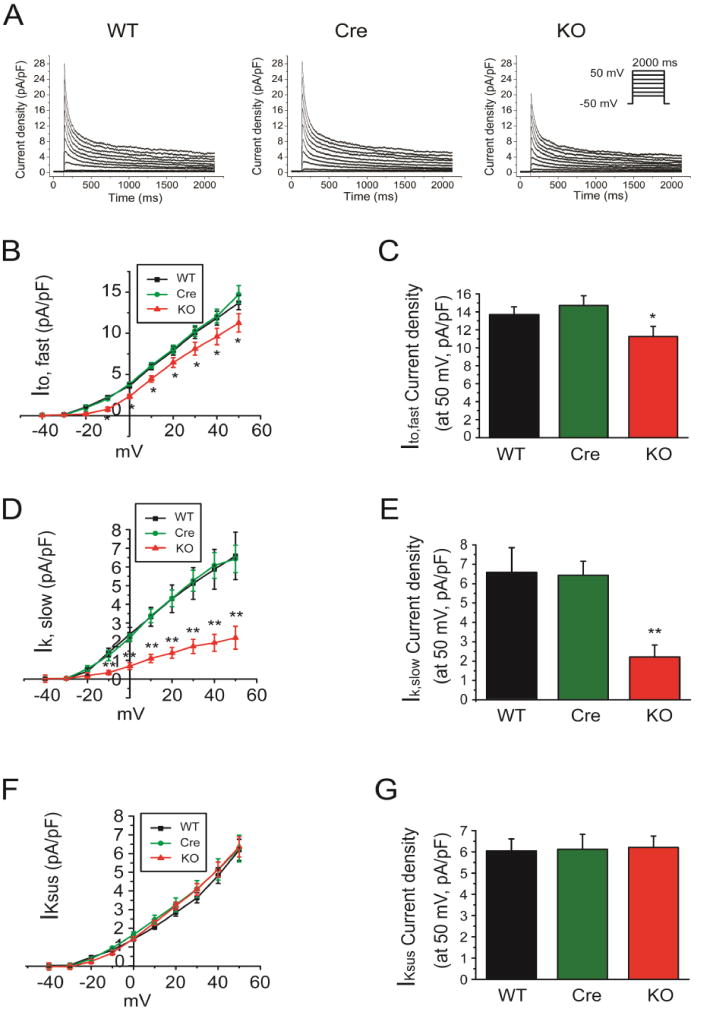

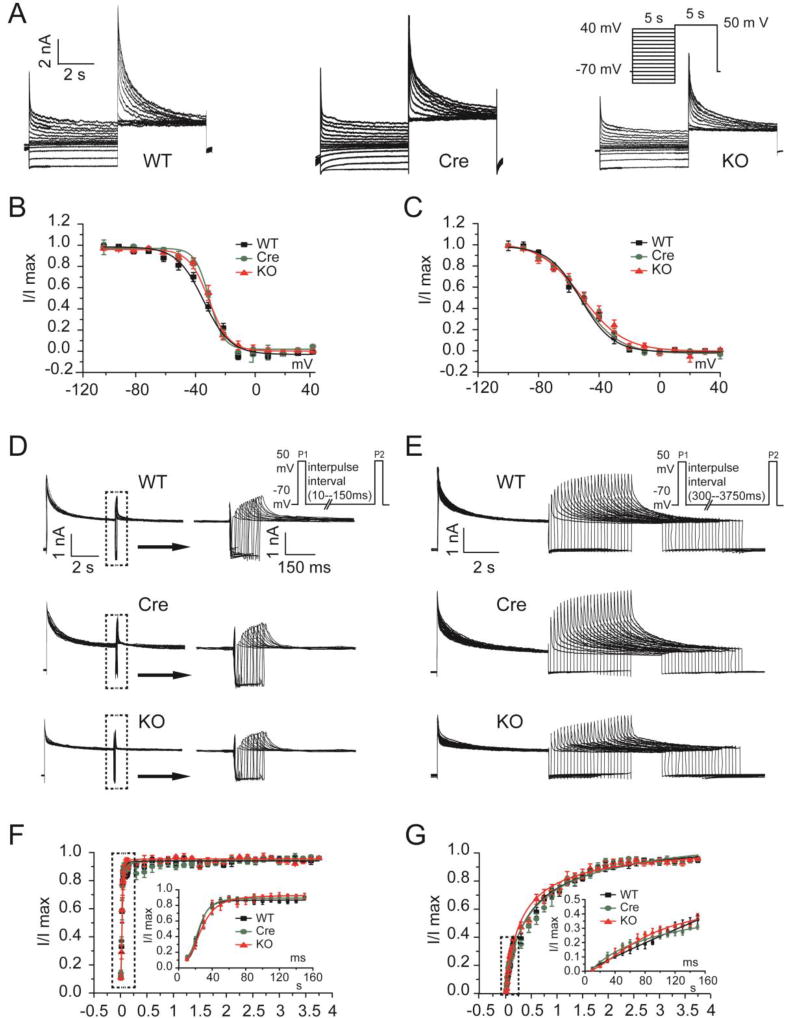

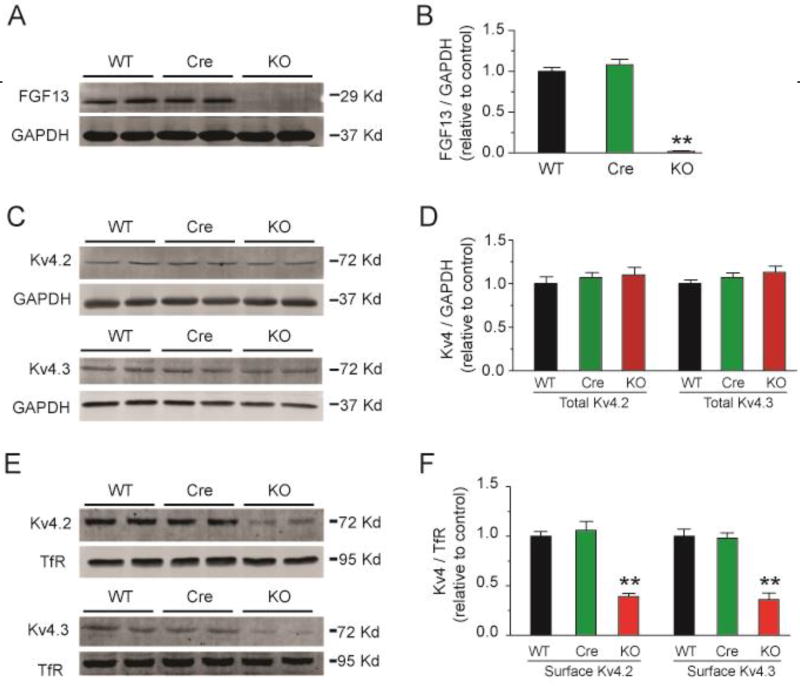

We therefore looked for an alternative explanation for the prolonged APD observed in the Fgf13 KO mice, focusing on a possible reduction in repolarizing K+ currents. We measured the three main components of the outward K+ currents in adult mouse ventricular myocytes: the rapidly inactivating, transient outward K+ current (Ito, fast), a slowly inactivating, transient outward K+ currents (IK, slow), and the sustained outward K+ currents (IKsus). The decay phases of the K+ currents were fitted to the sum of 2 exponentials to provide the amplitudes of Ito,fast, IK,slow, and IKsus[28]. As shown in Fig. 5A–E and Table 3, the current density of Ito,fast and IK,slow were significantly reduced in Fgf13 KO cardiomyocytes (13.7±0.9 pA/pF, 14.7±1.1 pA/pF and 11.3±1.1 pA/pF for Ito, fast in WT, Cre and Fgf13 KO, respectively; 6.6±1.3 pA/pF, 6.4±0.7 pA/pF and 2.2±0.6 pA/pF for IK, slow in WT, Cre and Fgf13 KO recorded at +50 mV, respectively, p<0.05), but IKsus was not affected (6.1±0.6 mV, 6.1±0.7 mV and 6.2±0.5 mV, recorded at +50 mV, respectively, p>0.05) (Fig. 5F,G and Table 3). To further determine the mechanisms for the reduced Ito current density in Fgf13 KO mice, we first examine whether the reduced Ito current density in Fgf13 KO mice might be attributatble to effects on the channel gating kinetics by analyzing Ito,fast and IK,slow inactivation and recovery from inactivation in isolated ventricular myocytes. We found neither parameter was affected in Fgf13 KO mice (Fig. 6 and Table 3). Therefore, we examine total protein levels of Kv4.2 and Kv4.3, the pore-forming subunits for these K+ currents, and the amount of Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 at the cardiomyocyte sarcolemma (by surface biotinylation). In Fgf13 KO animals, the total Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 protein in cardiomyocytes was not different from the controls (Fig. 7A–D). In contrast, we observed a significant reduction in Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 surface protein in cardiomyocytes from Fgf13 KO mice (Fig. 7E, F). Together, these data suggest that the prolongation of the APD in Fgf13 KO mice resulted from a reduction of both Ito,fast and IK,slow currents. To determine if the FGF13-dependent regulation of these K+ current amplitudes resulted from an interaction between FGF13 and the Kv4 subunits, we performed co-immunoprecipitations in cardiomyocytes (Supplemental Fig. 2). Neither Kv4.2 nor Kv4.3 was co-immunoprecipitated with FGF13, suggesting that the mechanism by which FGF13 affects these K+ currents was not due to a direction interaction.

Fig. 5.

Conditional knockout of FGF13 reduced outward K+ currents in ventricular cardiomyocytes. (A) Exemplar outward K+ current traces elicited by 2000-ms depolarizing pulses to test potentials between −40 mV and +50 mV from a holding potential of −50 mV at 5-mV increments. Inset shows schematic of the voltage clamp protocol. (B) Summarized current-voltage relationship of rapidly inactivating, transient outward K+ current (Ito,fast) for WT, Myh6-MCM (Cre) and Fgf13 KO (KO) mice. (C) Peak Ito,fast densities at +50mV are shown (n=9, 12, and 11 for WT, Cre, and KO, respectively, *indicates p<0.05 compared to WT; N=3 mice per group). (D) Summarized current-voltage relationship of slowly inactivating, transient outward K+ currents (IK,slow) for WT, Cre, and KO mice. (E) Peak IK,slow densities at +50mV are shown (n=9, 12, and 11 for WT, Cre, and KO, respectively, **indicates p<0.01 compared to WT; N=3 mice per group).(F) Summarized current-voltage relationship of sustained outward K+ currents (IKsus) for WT, Cre, and KO mice. (G) Peak IKsus densities at +50mV are shown (n=9, 12, and 11 for WT, Cre, and KO, N=3 mice per group).

Table 3.

Summary of outward K+ currents patch clamp data

| WT | Cre | FGF13 KO | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ito, fast-peak density (pA/pF) | 13.7 ± 0.9 (9) | 14.7 ± 1.1 (12) | 11.3 ± 1.1* (11) |

| τfast of inactivation (ms) | 51.2 ± 4.0 (9) | 47.8 ± 2.1 (12) | 38.2 ± 3.7* (11) |

| IK, slow-peak density (pA/pF) | 6.6±1.3 (9) | 6.4 ± 0.7 (12) | 2.2±0.6** (11) |

| τslow of inactivation (ms) | 666.7±61.9 (9) | 655.1 ± 27.9 (12) | 623.6±93.8 (11) |

| IKsus-peak density (pA/pF) | 6.1±0.6 (9) | 6.1 ± 0.7 (12) | 6.2±0.5 (11) |

| V1/2 of Ito, fast inactivation (mV) | −31.6±1.4 (8) | −30.4±2.6 (9) | −29.4±1.6 (10) |

| V1/2 of IK, slow inactivation (mV) | −54.4±2.8 (8) | −52.9±1.9 (9) | −53.15±2.8 (10) |

| τ of Ito, fast recovery (ms) | 22.8±3.3 (7) | 21.1±2.1 (7) | 28.1±6.2 (6) |

| τ of IK, slow recovery (ms) | 730.9±87.9 (7) | 792.1±106.0 (7) | 589.2±68.9 (6) |

The number of cells analyzed for each parameter is provided in parentheses.

indicates p<0.05,

indicates p<0.01, compared to WT control.

Fig. 6.

Inactivation and recovery from inactivation of outward K+ currents were not modified in FGF13 KO mice. (A) Exemplar inactivation of Ito current traces elicited by 5-s conditioning pulses from a holding potential of −70 mV to voltages between −100 mV and +40 mV in 10-mV increments prior to a test potential at +50 mV (inset). Inset shows schematic of the voltage clamp protocol. (B) Summarized Ito, fast inactivation curves for WT, Myh6-MCM (Cre) and Fgf13 KO (KO) mice. (C) Summarized Ik, slow inactivation curves for WT, Cre, and KO mice (n=8, 9, and 10 for WT, Cre, and KO, N=3 mice per group). (D and E) Exemplar recovery from inactivation of Ito current traces determined from a holding potential of −70 mV, using 30-ms pulses separated by a recovery time from 10 to 150 ms at +50 mV (D) or from 300 to 3750 ms at +50 mV (E). Inset shows schematic of the voltage clamp protocol. (F) Normalized Ito, fast recovery vs interpulse interval for WT, Cre, and KO mice. (G) Normalized Ik, slow recovery vs interpulse interval for WT, Cre, and KO mice (n=7, 7, and 6 for WT, Cre, and KO, N=3 mice per group).

Fig. 7.

Conditional knockout of FGF13 decreases cell surface Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 channels in ventricular cardiomyocytes. (A) Representative immunoblot of FGF13 protein expression in ventricular cardiomyocytes from WT, Myh6-MCM (Cre) and Fgf13 KO (KO) mice. GAPDH was used as loading control. (B) Quantitative analysis of FGF13 protein expression from WT, Cre, and KO mice. ** indicates p<0.01 compared to WT; n=3. (C) Representative immunoblot of total Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 protein expression in ventricular cardiomyocytes from WT, Cre, and KO mice. GAPDH was used as loading control. (D) Quantitative analysis of total Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 protein expression from WT, Cre, and KO mice. n=3. (E) Representative cell surface biotinylaton experiment showing biotinylated Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 protein expression in ventricular cardiomyocytes from WT, Cre, and KO mice. Transferrin receptor (TfR) was used as loading control. (F) Quantitative analysis of cell surface Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 protein expression from WT, Cre, and KO mice. ** indicates p<0.01 compared to WT; n=3.

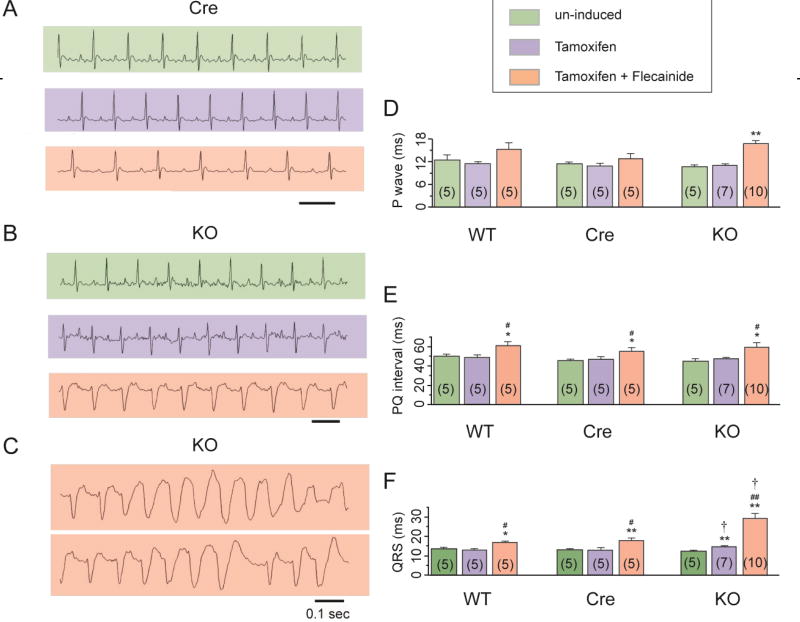

3.5 Fgf13 knockout affects the ECG and results in flecainide-inducible ventricular tachyarrhythmias

We next investigated the in vivo consequences of deleting Fgf13 by analyzing the ECG in lightly anesthetized mice (Fig. 8A, B and C). Tamoxifen treatment induced no changes in the P wave duration, PQ interval, or QRS interval in the WT and the Cre mice (Fig. 8D, E and F). However, knockout of FGF13 significantly prolonged the QRS interval (Fig. 8F); the P wave duration, and PQ interval were not affected (Fig. 8D, E and Table 4). These observations were consistent with the observed reduction in Na+ channel current, as we showed in Fig. 3. No obvious arrhythmias occurred during the 30 min observation window. During a longer observation using a 24-hour implantable telemetry system for ECG, none of the WT, Cre and Fgf13 KO mice studied showed arrhythmias (n=5 for each group, data not shown). Because the prolonged QRS interval on ECG and the reduced Na+ channel current in the Fgf13 KO mice, we tested whether Fgf13 KO mice displayed increased sensitivity to challenge with the Na+ channel blocker flecainide. Flecainide (20 mg/kg, i.p.) was administered and mice were then observed for 30 min. As expected, flecainide treatment significantly increased the PQ and QRS intervals in the WT and the Cre mice (p<0.05, compared to uninduced or tamoxifen treated mice not given flecainide). The increase in QRS duration after flecainide administration was even greater in Fgf13 KO mice (31.4±5.7%, 36.8±8.4% and 99.4±19.6% for WT, Cre and Fgf13 KO, respectively, p<0.05 by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test). Moreover, in 6 of 7 Fgf13 KO mice, flecainide administration induced non-sustained ventricular tachycardia, which was never observed in WT or Cre mice (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

FGF13 cardiac-specific knockout mice showed abnormal ECG phenotype and drug inducible ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Example ECG traces from Myh6-MCM (Cre) (A) and Fgf13 KO (KO) (B) mice un-induced, tamoxifen induced without flecainide challenge, or tamoxifen-induced with flecainide challenge. (C) Ventricular tachycardia was observed after flecainide challenge only in tamoxifen induced Fgf13 KO mice. Summarized data for P wave(D), PQ interval(E), and QRS interval(F) in WT, Cre, and Fgf13 KO mice. *indicates p<0.05, **indicates p<0.01 versus un-induced, #indicates p<0.05, ##indicates p<0.01 versus Tamoxifen, †indicates p<0.05, versus WT at the respective condition. The numbers of mice used are indicated within each bar plot.

Table 4.

Summary of ECG Data

| WT | Cre | FGF13 KO | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P wave | un-induced | 12.5±1.0(5) | 11.6±0.4(5)△ | 10.8±0.4(5)△ |

| Tamoxifen | 11.5±0.4(5) | 10.8±0.8(5)△ | 10.9±0.4(7)△ | |

| Tamoxifen+Flecainide | 15.5±1.2(5) | 12.8±1.4(5)△ | 16.8±0.8(10)△** | |

| PQ interval | un-induced | 50.5±1.3(5) | 46.0±1.3(5)△ | 45.3±2.1(5)△ |

| Tamoxifen | 49.0±1.9(5) | 47.2±2.6(5)△ | 47.4±1.4(7)△ | |

| Tamoxifen+Flecainide | 61.5±2.8(5)*# | 55.6±3.8(5)△*# | 59.4±4.9(10)△*# | |

| QRS interval | un-induced | 13.5± 0.7(5) | 13.2±0.5(5)△ | 12.5±0.5(5)△ |

| Tamoxifen | 13.0±0.4(5) | 13.2± 1.0(5)△ | 14.9±0.4(7)†** | |

| Tamoxifen+Flecainide | 17.0± 0.4(5)*# | 18.0±1.3(5)△**# | 29.4±2.7(10)†**## |

The number of mice used is indicated in parentheses.

indicates p>0.05, versus WT at the respective condition,

indicates p<0.05, versus WT at the respective condition,

indicates p<0.05,

indicates p<0.01 versus un-induced,

indicates p<0.05,

indicates p<0.01 versus Tamoxifen.

4. Discussion

iFGF/FHFs, a subfamily of FGFs, are critical regulators of multiple ion channels in heart and in brain[1, 5, 25, 26, 32–35], yet their entire portfolio of modulatory effects is not yet known. Defining this portfolio has been a particular challenge in the heart in comparison to the brain, since the availability of an Fgf14 knockout animal revealed definitive information about the role of that neuronal iFGF/FHF but a mouse model in which the major cardiac iFGF/FHF, Fgf13, was deleted has not been reported. Exploiting an inducible, cardiac-specific Fgf13 KO mouse, we have now defined for the first time the in vivo role of FGF13. We confirmed certain observations previously obtained with shRNA knockdown approaches. Most notably, we saw that Fgf13 is directly responsible for regulation of Na+ channels, as Na+ channel current density was markedly reduced in the Fgf13 KO model. The abnormal ECG parameters and increased susceptibility to flecainide provided additional indicators. These results also confirm and extend our previous finding that a mutation in the major human cardiac iFGF/FHF (FGF12) that reduces interaction with Na+ channels and leads to a diminution of Na+ currents, is associated with Brugada syndrome.[23] Further, these findings provide additional support for our recent identification of the mechanism for an arrhythmogenic SCN5A Na+ channel mutation is that the mutation affects interaction with FGF12[24].

However, echoing how analyses of a Fgf14 knockout model revealed new details about the function of this neuronally-restricted iFGF/FHF in the brain, results here with a cardiac-specific Fgf13 KO uncovered previously unknown roles of iFGF/FHF in heart and revealed compensatory changes in vivo that were not heretofore appreciated. Most notably, we found a novel role for FGF13 regulation of Ito. As this is the major repolarizing K+ current in murine ventricular myocytes[36], the reduced Ito current in the Fgf13 KO animals provided a clear rationale for the prolonged cardiac action potentials. We also explored the mechanism by which FGF13 affects Ito currents. We found FGF13 KO reduced current density by specifically reducing sarcolemmal Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 without affecting channel translation or channel gating properties. These data are consistent with the finding that the homologous FGF14 affects the neuronal KCNQ2/KCNQ3 K+ channel complex in hippocampal neurons[37]. On the other hand, FGF14 interacts directly with KCNQ2/KCNQ3 channels while we observed no interaction between FGF13 and the relevant K+ channel subunits Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 in this study, suggesting an alternative mechanism.

Further, the unexpectedly prolonged APD50 (experiments in cardiomyocytes in which FGF13 had been knocked down by shRNA showed a shorter APD) revealed compensatory mechanisms (decreased Ito,fast and IK,slow) and thus new roles for FGF13. Previously, a mutation in the main cardiac iFGF/FHF (FGF12) that reduced NaV1.5 interaction was shown to prolong the cardiac action potential[24], similarly to what we observed here. The APD-prolongation in that recent study was attribute to effects on NaV1.5 inactivation kinetics, but the results here highlight additional possibilities for further investigation. Moreover, our analysis showing no change in Ca2+ currents after Fgf13 knockout (after acute knockdown Ca2+ currents were reduced) provides an additional indication of in vivo compensation [25]. In this context, our finding of compensatory changes observed in the context of a knockout but not observed with acute knockdown echo recent findings in other models, such as the unexpected absence of NaV1.5 redistribution after SAP97 knockout [38, 39]. Finally, the multiple effects of FGF13 on cardiac ionic currents imply the possibility of dynamic regulation of the integrated cardiac electrical activity by iFGF/FHFs in vivo, that were not investigated in this study. Whether iFGF/FHFs are dynamically regulated, such as after an insult like ischemia or pressure overload, is not known, but this inducible model system provides an opportunity for future investigations.

In summary, this inducible, cardiac-specific Fgf13 knockout model revealed new information about the regulation of repolarizing K+ currents by FGF13 and demonstrated compensatory mechanisms in vivo, while confirming the iFGF/FHF-dependent regulation of Na+ channels in heart and the consequences of loss-of-function iFGF/FHF mutations in arrhythmias. This model will provide a platform for future investigations of roles for iFGF/FHFs in vivo.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

FGF13 is a critical cardiac Na+ channel modulator and Fgf13 knockout mice have increased arrhythmia susceptibility in the setting of Na+ channel blockade.

Fgf13 knockout mice exhibited slower upstrokes and reduced amplitude, but unexpectedly had longer durations.

A novel role for FGF13 regulation of Ito was revealed.

No change in Ca2+ currents after Fgf13 knockout provides an additional indication of in vivo compensation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31171097), Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province (No. C2014206419), Research Project of Science and Technology of Higher Education of Hebei Province (No. ZD2015007 and No. ZD2016002) to C.W.; American Heart Association Predoctoral Award (13PRE15990006) to E.Q.W.; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), R01HL71665 and R01HL112928 to G.S.P.; National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31371166) to S.W. National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31270882), and the National Basic Research Program of China (2013CB531302) to H.Z. We thank Bingcai Guan for expert technical assistance in patch clamp recording.

Glossary

- iFGFs

Intracellular fibroblast growth factors

- FHF

Fibroblast growth factor homologous factor

- FGF

Fibroblast growth factors

- INa

Na+ currents

- ICa

voltage-gated Ca2+ currents

- Ito

Transient outward K+ current

- IKsus

Sustained outward K+ currents

- ECG

Electrocardiogram

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.Goldfarb M. Fibroblast growth factor homologous factors: evolution, structure, and function. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005 Apr;16(2):215–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smallwood PM, Munoz-Sanjuan I, Tong P, Macke JP, Hendry SH, Gilbert DJ, et al. Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) homologous factors: new members of the FGF family implicated in nervous system development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996 Sep 3;93(18):9850–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Munoz-Sanjuan I, Smallwood PM, Nathans J. Isoform diversity among fibroblast growth factor homologous factors is generated by alternative promoter usage and differential splicing. J Biol Chem. 2000 Jan 28;275(4):2589–97. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gecz J, Baker E, Donnelly A, Ming JE, McDonald-McGinn DM, Spinner NB, et al. Fibroblast growth factor homologous factor 2 (FHF2): gene structure, expression and mapping to the Borjeson-Forssman-Lehmann syndrome region in Xq26 delineated by a duplication breakpoint in a BFLS-like patient. Hum Genet. 1999 Jan;104(1):56–63. doi: 10.1007/s004390050910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang C, Hennessey JA, Kirkton RD, Graham V, Puranam RS, Rosenberg PB, et al. Fibroblast growth factor homologous factor 13 regulates Na+ channels and conduction velocity in murine hearts. Circ Res. 2011 Sep 16;109(7):775–82. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.247957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu C, Dib-Hajj SD, Waxman SG. Fibroblast growth factor homologous factor 1B binds to the C terminus of the tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium channel rNav1.9a (NaN) J Biol Chem. 2001 Jun 1;276(22):18925–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101606200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lou JY, Laezza F, Gerber BR, Xiao M, Yamada KA, Hartmann H, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 14 is an intracellular modulator of voltage-gated sodium channels. J Physiol. 2005 Nov 15;569(Pt 1):179–93. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.097220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang C, Wang C, Hoch EG, Pitt GS. Identification of novel interaction sites that determine specificity between fibroblast growth factor homologous factors and voltage-gated sodium channels. J Biol Chem. 2011 Jul 8;286(27):24253–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.245803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang J, Wang Z, Sinden DS, Wang X, Shan B, Yu X, et al. FGF13 modulates the gating properties of the cardiac sodium channel Nav1.5 in an isoform-specific manner. Channels (Austin) 2016 May;31:1–11. doi: 10.1080/19336950.2016.1190055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pablo JL, Wang C, Presby MM, Pitt GS. Polarized localization of voltage-gated Na+ channels is regulated by concerted FGF13 and FGF14 action. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016 May 10;113(19):E2665–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521194113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan H, Pablo JL, Wang C, Pitt GS. FGF14 modulates resurgent sodium current in mouse cerebellar Purkinje neurons. Elife. 2014;3:e04193. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu WC, Nenov MN, Shavkunov A, Panova N, Zhan M, Laezza F. Identifying a kinase network regulating FGF14:Nav1.6 complex assembly using split-luciferase complementation. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0117246. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ali S, Shavkunov A, Panova N, Stoilova-McPhie S, Laezza F. Modulation of the FGF14:FGF14 homodimer interaction through short peptide fragments. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2015;13(9):1559–70. doi: 10.2174/1871527313666141126103309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laezza F, Lampert A, Kozel MA, Gerber BR, Rush AM, Nerbonne JM, et al. FGF14 N-terminal splice variants differentially modulate Nav1.2 and Nav1.6-encoded sodium channels. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2009 Oct;42(2):90–101. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Swieten JC, Brusse E, de Graaf BM, Krieger E, van de Graaf R, de Koning I, et al. A mutation in the fibroblast growth factor 14 gene is associated with autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia [corrected] Am J Hum Genet. 2003 Jan;72(1):191–9. doi: 10.1086/345488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Q, Bardgett ME, Wong M, Wozniak DF, Lou J, McNeil BD, et al. Ataxia and paroxysmal dyskinesia in mice lacking axonally transported FGF14. Neuron. 2002 Jul 3;35(1):25–38. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00744-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laezza F, Gerber BR, Lou JY, Kozel MA, Hartman H, Craig AM, et al. The FGF14(F145S) mutation disrupts the interaction of FGF14 with voltage-gated Na+ channels and impairs neuronal excitability. J Neurosci. 2007 Oct 31;27(44):12033–44. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2282-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bosch MK, Carrasquillo Y, Ransdell JL, Kanakamedala A, Ornitz DM, Nerbonne JM. Intracellular FGF14 (iFGF14) Is Required for Spontaneous and Evoked Firing in Cerebellar Purkinje Neurons and for Motor Coordination and Balance. J Neurosci. 2015 Apr 29;35(17):6752–69. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2663-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiao M, Bosch MK, Nerbonne JM, Ornitz DM. FGF14 localization and organization of the axon initial segment. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2013 Sep;56:393–403. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Puranam RS, He XP, Yao L, Le T, Jang W, Rehder CW, et al. Disruption of Fgf13 causes synaptic excitatory-inhibitory imbalance and genetic epilepsy and febrile seizures plus. J Neurosci. 2015 Jun 10;35(23):8866–81. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3470-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alshammari TK, Alshammari MA, Nenov MN, Hoxha E, Cambiaghi M, Marcinno A, et al. Genetic deletion of fibroblast growth factor 14 recapitulates phenotypic alterations underlying cognitive impairment associated with schizophrenia. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;6:e806. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tempia F, Hoxha E, Negro G, Alshammari MA, Alshammari TK, Panova-Elektronova N, et al. Parallel fiber to Purkinje cell synaptic impairment in a mouse model of spinocerebellar ataxia type 27. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:205. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hennessey JA, Marcou CA, Wang C, Wei EQ, Tester DJ, Torchio M, et al. FGF12 is a candidate Brugada syndrome locus. Heart Rhythm. 2013 Dec;10(12):1886–94. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.09.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Musa H, Kline CF, Sturm AC, Murphy N, Adelman S, Wang C, et al. SCN5A variant that blocks fibroblast growth factor homologous factor regulation causes human arrhythmia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015 Oct 6;112(40):12528–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1516430112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hennessey JA, Wei EQ, Pitt GS. Fibroblast growth factor homologous factors modulate cardiac calcium channels. Circ Res. 2013 Aug 2;113(4):381–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yan H, Pablo JL, Pitt GS. FGF14 regulates presynaptic Ca2+ channels and synaptic transmission. Cell Rep. 2013 Jul 11;4(1):66–75. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldfarb M, Schoorlemmer J, Williams A, Diwakar S, Wang Q, Huang X, et al. Fibroblast growth factor homologous factors control neuronal excitability through modulation of voltage-gated sodium channels. Neuron. 2007 Aug 2;55(3):449–63. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu H, Guo W, Nerbonne JM. Four kinetically distinct depolarization-activated K+ currents in adult mouse ventricular myocytes. J Gen Physiol. 1999 May;113(5):661–78. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.5.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Remme CA, Verkerk AO, Nuyens D, van Ginneken AC, van Brunschot S, Belterman CN, et al. Overlap syndrome of cardiac sodium channel disease in mice carrying the equivalent mutation of human SCN5A-1795insD. Circulation. 2006 Dec 12;114(24):2584–94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.653949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin CA, Zhang Y, Grace AA, Huang CL. In vivo studies of Scn5a+/− mice modeling Brugada syndrome demonstrate both conduction and repolarization abnormalities. J Electrocardiol. 2010 Sep-Oct;43(5):433–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sohal DS, Nghiem M, Crackower MA, Witt SA, Kimball TR, Tymitz KM, et al. Temporally regulated and tissue-specific gene manipulations in the adult and embryonic heart using a tamoxifen-inducible Cre protein. Circ Res. 2001 Jul 6;89(1):20–5. doi: 10.1161/hh1301.092687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wei EQ, Barnett AS, Pitt GS, Hennessey JA. Fibroblast growth factor homologous factors in the heart: a potential locus for cardiac arrhythmias. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2011 Oct;21(7):199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang X, Bao L, Yang L, Wu Q, Li S. Roles of intracellular fibroblast growth factors in neural development and functions. Sci China Life Sci. 2012 Dec;55(12):1038–44. doi: 10.1007/s11427-012-4412-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shavkunov A, Panova N, Prasai A, Veselenak R, Bourne N, Stoilova-McPhie S, et al. Bioluminescence methodology for the detection of protein-protein interactions within the voltage-gated sodium channel macromolecular complex. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2012 Apr;10(2):148–60. doi: 10.1089/adt.2011.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shavkunov AS, Wildburger NC, Nenov MN, James TF, Buzhdygan TP, Panova-Elektronova NI, et al. The fibroblast growth factor 14.voltage-gated sodium channel complex is a new target of glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) J Biol Chem. 2013 Jul 5;288(27):19370–85. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.445924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boukens BJ, Rivaud MR, Rentschler S, Coronel R. Misinterpretation of the mouse ECG: 'musing the waves of Mus musculus'. J Physiol. 2014 Nov 1;592(Pt 21):4613–26. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.279380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pablo JL, Pitt GS. FGF14 is a regulator of KCNQ2/3 channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Dec 19; doi: 10.1073/pnas.1610158114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petitprez S, Zmoos AF, Ogrodnik J, Balse E, Raad N, El-Haou S, et al. SAP97 and dystrophin macromolecular complexes determine two pools of cardiac sodium channels Nav1.5 in cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2011 Feb 4;108(3):294–304. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.228312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gillet L, Rougier JS, Shy D, Sonntag S, Mougenot N, Essers M, et al. Cardiac-specific ablation of synapse-associated protein SAP97 in mice decreases potassium currents but not sodium current. Heart Rhythm. 2015 Jan;12(1):181–92. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.