Abstract

Background

The best treatment options for binge-eating disorder are unclear.

Purpose

To summarize evidence about the benefits and harms of psychological and pharmacologic therapies for adults with binge-eating disorder.

Data Sources

English-language publications in EMBASE, the Cochrane Library, Academic OneFile, CINAHL, and ClinicalTrials.gov through 18 November 2015, and in MEDLINE through 12 May 2016.

Study Selection

9 waitlist-controlled psychological trials and 25 placebo-controlled trials that evaluated pharmacologic (n = 19) or combination (n = 6) treatment. All were randomized trials with low or medium risk of bias.

Data Extraction

2 reviewers independently extracted trial data, assessed risk of bias, and graded strength of evidence.

Data Synthesis

Therapist-led cognitive behavioral therapy, lisdexamfetamine, and second-generation antidepressants (SGAs) decreased binge-eating frequency and increased binge-eating abstinence (relative risk, 4.95 [95% CI, 3.06 to 8.00], 2.61 [CI, 2.04 to 3.33], and 1.67 [CI, 1.24 to 2.26], respectively). Lisdexamfetamine (mean difference [MD], −6.50 [CI, −8.82 to −4.18]) and SGAs (MD, −3.84 [CI, −6.55 to −1.13]) reduced binge-eating–related obsessions and compulsions, and SGAs reduced symptoms of depression (MD, −1.97 [CI, −3.67 to −0.28]). Headache, gastrointestinal upset, sleep disturbance, and sympathetic nervous system arousal occurred more frequently with lisdexamfetamine than placebo (relative risk range, 1.63 to 4.28). Other forms of cognitive behavioral therapy and topiramate also increased abstinence and reduced binge-eating frequency and related psychopathology. Topiramate reduced weight and increased sympathetic nervous system arousal, and lisdexamfetamine reduced weight and appetite.

Limitations

Most study participants were overweight or obese white women aged 20 to 40 years. Many treatments were examined only in single studies. Outcomes were measured inconsistently across trials and rarely assessed beyond end of treatment.

Conclusion

Cognitive behavioral therapy, lisdexamfetamine, SGAs, and topiramate reduced binge eating and related psychopathology, and lisdexamfetamine and topiramate reduced weight in adults with binge-eating disorder.

Primary Funding Source

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Binge-eating disorder (BED), the most common eating disorder, affects approximately 3% of U.S. adults in their lifetime (1–3). It is characterized by recurrent (≥1 per week for 3 months), brief (≤2 hours), psychologically distressing binge-eating episodes during which patients sense a lack of control and consume larger amounts of food than most people would under similar circumstances. Full diagnostic criteria are available in Appendix Table 1 (available at www.annals.org). Binge-eating disorder is more common in women (3.5%) than men (2.0%) and in obese individuals (5% to 30%) (4, 5), especially those who are severely obese and those seeking obesity treatment (3, 6). It typically emerges in early adulthood (1, 7) but may surface in adolescence (8) and persist well beyond midlife (9). In May 2013, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) officially recognized BED as a distinct eating disorder with a lower diagnostic threshold (in terms of frequency and duration of symptoms) than formerly accepted (10). The numbers of persons presenting for evaluation, receiving a BED diagnosis, and requiring treatment are expected to increase (11, 12).

Appendix Table 1.

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Binge-Eating Disorder

| Definition, by Criteria Set |

|---|

| Criterion 1 |

Recurrent episodes of binge eating characterized by both of the following:

|

| Criterion 2 |

Binge-eating episodes are associated with 3 (or more) of the following:

|

| Criterion 3 |

| Marked distress regarding binge eating is present. |

| Criterion 4 |

| Binge eating occurs, on average, at least 1 d/wk for 3 mo |

| Criterion 5 |

| Binge eating is not associated with regular use of inappropriate compensatory behavior (e.g., purging, fasting, excessive exercise) and does not occur exclusively during the course of anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa. |

| Severity grading, episodes/wk |

| Mild: 1–3 |

| Moderate: 4–7 |

| Severe: 8–13 |

| Extreme: ≥14 |

DSM-5 = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (10).

BED is associated with poorer psychological and physical well-being, including major depressive and other psychiatric disorders (13, 14), relationship distress and impaired social role functioning (14–16), chronic pain (13, 14), obesity (13, 14, 17), and diabetes (18–21). Binge eating and BED predispose individuals to metabolic syndrome independent of weight gain (17), type 2 diabetes (22), earlier-onset diabetes (20), and worse diabetes-related complications and outcomes owing to nonadherence to recommended dietary modifications (23–25). Similarly, binge eating is implicated as a treatment-limiting factor in patients undergoing bariatric surgery, approximately 25% of whom experience “loss-of-control” eating (26) that interferes with adherence to postsurgical nutritional recommendations and may impede weight loss and reduce quality of life (27, 28).

Treatment aims to reduce binge-eating frequency and disordered eating–related cognitions, improve metabolic health and weight (in patients who are obese, diabetic, or both), and regulate mood (in patients with coexisting depression or anxiety). Treatment approaches include psychological and behavioral treatments (hereafter “psychological”), pharmacologic treatments, and combinations of the 2 approaches. Table 1 describes common treatments for BED.

Table 1.

Interventions Commonly Used in Treating Patients With Binge-Eating Disorder

| Treatment | Description |

|---|---|

| Psychological, behavioral, or both | |

| CBT | Focuses on identifying relationships among thoughts, feelings, and behaviors; aims to reduce negative emotions and undesirable behavior patterns by changing negative thoughts about oneself and the world. CBT may be delivered in various forms according to the level of therapist involvement—e.g., from therapist engaged in all aspects of treatment (therapist-led CBT) to no therapist engagement (self-help CBT). In self-help CBT, the patient follows a treatment manual or book, either with the help of a facilitator (e.g., guided or structured self-help) or alone. CBT may be tailored to the patient by focusing on problematic eating-related cognitions and behaviors. |

| Dialectical behavior therapy | Focuses on increasing mindfulness and developing skills to improve emotion regulation, distress tolerance, and interpersonal relationships to help patients respond to stress and negative affect more effectively. |

| Interpersonal psychotherapy | Focuses on identifying and changing the role of interpersonal functioning in causing and maintaining negative mood, psychological distress, and unhealthy behaviors. |

| Behavioral weight loss | Incorporates various behavioral strategies to promote weight loss, such as restricting caloric intake and increasing physical activity. |

| Pharmacologic | |

| Antidepressants | Selectively inhibit reuptake of neurotransmitters involved in regulating mood and appetite (i.e., dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin). Common examples include bupropion, citalopram, desipramine, duloxetine, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, and sertraline, which are indicated for treating patients with depression. |

| Anticonvulsants | Indicated for treating patients with epilepsy, bipolar disorder, major depression, and migraines. Topiramate, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, is the most commonly used. |

| Antiobesity agents | Used to treat obesity. For example, orlistat inhibits pancreatic lipase and thus decreases fat absorption in the gut. |

| Central nervous system stimulants | Generally used to enhance or accelerate mental and physical processes; specifically used to treat attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder and certain sleep problems. Lisdexamfetamine, the only U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved medication for binge-eating disorder, belongs to this class. |

CBT = cognitive behavioral therapy.

Current guidelines from the APA (29, 30) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (31) support the use of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, but they differ in content and timing. The APA recommends a team approach (including psychiatrists, psychologists, dietitians, and social workers) with CBT as the cornerstone and medication as adjunctive therapy. In contrast, NICE recommends a CBT-based self-help approach but also endorses medication monotherapy as sufficient treatment for some patients. Best practices for weight management are unclear, in part because of different perspectives on dieting-based approaches (32, 33) and bariatric surgery (34–37) in obese individuals with BED. Moreover, little is known about the effect of patient-, provider-, and setting-level factors on treatment outcomes.

Our group at the RTI International–University of North Carolina Evidence-Based Practice Center conducted a systematic review for the Agency for Health-care Research and Quality (AHRQ) (38) that updates and extends the scope of our 2006 AHRQ review on eating disorders (39, 40) by including studies of loss-of-control eating, examining nearly twice as many randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) of BED therapies, and applying meta-analytic techniques to measure BED treatment effectiveness.

Methods

Our methods, complete search strategies, and detailed evidence tables are available in the full systematic review (38). Our protocol (41) was guided by key questions reflecting previously identified evidence gaps, input from key informants and a technical expert panel, and analytic frameworks depicting treatment effectiveness and harms (Appendix Figure 1, available at www.annals.org). Key questions focused on the effectiveness of psychological treatments compared with waitlist, pharmacologic treatments compared with placebo, and combination treatments compared with placebo or waitlist. Primary outcomes were behavioral (reducing binge-eating frequency and increasing abstinence from binge eating), psychological (improving levels of eating-related and general psychological outcomes), and physical (reducing weight and improving other markers of health where relevant), and also included harms from treatment.

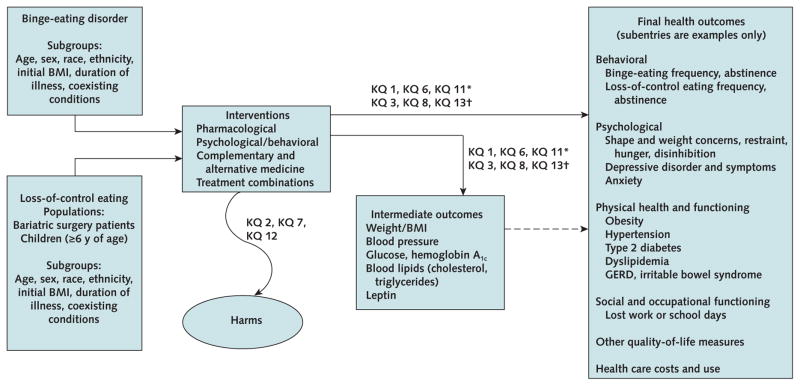

Appendix Figure 1.

Analytic framework for treatment effectiveness and harms.

BMI = body mass index; GERD = gastroesophageal reflux disease; KQ = key question.

* Effectiveness of treatment.

† Differences between subgroups.

Data Sources and Searches

We searched EMBASE, the Cochrane Library, Academic OneFile, CINAHL, and ClinicalTrials.gov from inception to 18 November 2015, and MEDLINE from inception to 12 May 2016 (Supplement, available at www.annals.org). We hand-searched reference lists and relevant systematic reviews.

Study Selection

We used a PICOTS (populations, interventions, comparators, outcomes, timing, settings, and study designs) approach to identify studies that met our inclusion and exclusion criteria. The population of interest was adults with a diagnosis of BED based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth or Fifth Edition. Interventions included pharmacologic, psychological, and behavioral treatments, as well as complementary and alternative medicine. We limited inclusion to RCTs that measured outcomes at the end of treatment or later in 10 or more randomly assigned patients; included active intervention, placebo, or waitlist control groups as comparators; were conducted in outpatient, inpatient, or home-based settings (such as self-help); and were published in English. We included trials conducted in any country. We selected abstracts for full-text review of articles if they met predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria (Appendix Table 2, available at www.annals.org). Two reviewers independently evaluated the full texts of selected articles to determine whether they should be included; disagreements were resolved by consensus discussion or with help from a third senior reviewer.

Appendix Table 2.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria*

| Category | Criteria

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Inclusion | Exclusion | |

| Population | Individuals of all races, ethnicities, and cultural groups who met DSM-IV or DSM-5 criteria for BED | Co-occurring anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa RCTs with fewer than 10 participants and nonrandomized studies with fewer than 50 participants |

| Interventions | Psychological, behavioral, pharmacological, or CAM treatments or combinations of treatments | Pharmacologic interventions not approved for marketing in the United States |

| Comparators | Any active intervention described in the PICOTS criteria, placebo, or usual care | Pharmacologic interventions not approved for marketing in the United States |

| Study duration | No limit | None |

| Settings | No limit; studies include inpatient, outpatient, or home-based settings for treatments such as self-help | None |

| Outcomes | Intermediate and final health outcomes, and treatment harms. Intermediate health outcomes including biomarkers that can be linked directly to final physical health outcomes, such that an accumulation or worsening over time in that biomarker would result in the final health outcome | Studies that did not include at least 1 of the outcomes |

| Timing of outcome measurement | End of treatment or later | Outcome measurement before study completion only |

BED = binge-eating disorder; CAM = complementary and alternative medicine; DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (10); DSM-5 = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition; PICOTS = populations, interventions, comparators, outcomes, timing, and setting; RCT = randomized, controlled trial.

These criteria are a subset of those used in the full report (38), which included populations of individuals with loss-of-control eating and outcomes reflecting the course of illness.

Data Abstraction and Risk-of-Bias Assessment

One reviewer abstracted details regarding study design, patient population, interventions and comparators, outcomes, duration of treatment and follow-up, settings, and results. A second reviewer checked the abstracted data for accuracy. For each study, 2 independent reviewers rated the risks of selection, performance, attrition, detection, and outcome reporting bias; they summarized their assessment overall as low, medium, or high risk of bias.

Statistical Analysis

For our investigation of treatments, we omitted studies with high risk of bias, except for harms and sensitivity analyses of meta-analyses. We graded the strength of evidence (SOE) for each major outcome with guidance from the Evidence-Based Practice Center regarding study limitations, consistency, precision, directness of the evidence, and risk of reporting bias (42, 43). The SOE grades are high, moderate, low, or insufficient, reflecting levels of confidence that the evidence represents the true effect. A grade of insufficient means that evidence either was unavailable or did not permit estimation of the effect. In this review, we report results with SOE grades of low, moderate, or high; see the technical report for more detailed results, including those with insufficient SOE (38).

For available trials using comparable treatment methods, durations, and outcomes, we performed an unadjusted random-effects meta-analysis using restricted maximum likelihood models (OpenMeta[Analyst] [Brown University Center for Evidence-Based Medicine]). Across studies, the percentage of patients achieving abstinence for each trial uses the number of all randomly assigned patients as the denominator to reflect a true intention-to-treat analysis (that is, to correct variations in results of modified intention-to-treat analyses from individual trials). We derived risk ratios (RRs) for abstinence (defined as 0 binge episodes recorded in the most recent assessment period, usually the past month) and mean differences (MDs) for binge episodes per week, binge days per week, eating-related obsessions and compulsions, body mass index (BMI), weight, and depression scores. We assessed statistical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic. In considering psychological studies for pooled analyses, we did not combine data from studies using different modes of delivery (for example, individual and group therapy) for the same treatment. If relevant, we conducted sensitivity analyses to measure the effect on pooled results of including studies rated high risk of bias. We also conducted qualitative syntheses of trials with interventions or outcomes that we judged insufficiently similar for meta-analysis.

Role of the Funding Source

This research was funded by AHRQ. Agency staff participated in developing the scope of the work, refining the analytic framework and key questions, resolving issues regarding the project scope, reviewing the draft report, and distributing it for peer review. AHRQ did not engage in selecting studies, assessing risk of bias, or synthesizing or interpreting data. The authors are solely responsible for the content and the decision to submit this manuscript for publication.

Results

Overview of Trials

We identified 34 trials with low or medium risk of bias (Appendix Figure 2 and Appendix Table 3, available at www.annals.org). Of these, 9 were waitlist-controlled psychological trials and 25 were placebo-controlled trials in which the active comparator was medication only (n = 19) or a combination treatment (n = 6). The psychological trials examined various forms of BED-focused CBT including self-help, psychodynamic interpersonal psychotherapy, dialectical behavior therapy, and behavioral weight loss treatment. The medication-only trials included anticonvulsants (topiramate and lamotrigine), antiobesity agents (orlistat), central nervous system stimulants (lisdexamfetamine), a dietary supplement (chromium picolinate), various second-generation antidepressants (SGAs; for example, citalopram, fluoxetine, and sertraline), and other medications (including acamprosate and armodafinil). Each of the 6 combination trials used a different behavioral plus medication approach.

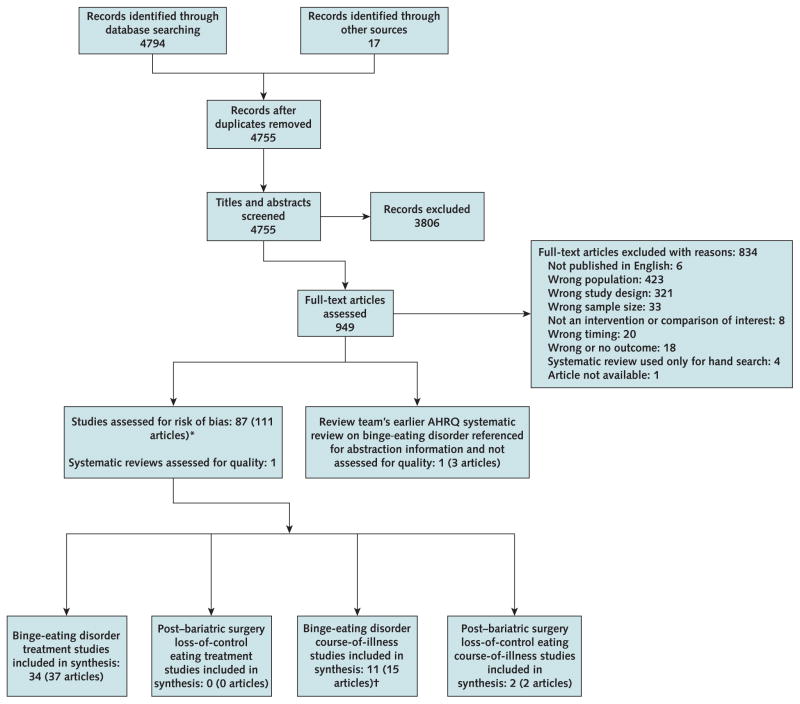

Appendix Figure 2.

Flow diagram.

AHRQ = Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

* The figure was adapted from a larger report. Not all studies assessed for risk of bias are accounted for at the bottom of the figure because some populations are not included in the analysis in this article.

† Three studies (3 articles) also are included for binge-eating disorder treatment (key questions 1, 2, and 3) synthesis.

Appendix Table 3.

Baseline Characteristics of the Included BED Treatment Effectiveness Trials (n = 34)

| Study, Year (Reference); Country | Intervention and Comparators; Randomly Assigned Participants, n | Treatment Duration | Mean Age (SD), y | Mean BMI (SD), kg/m2 | Female, % | Nonwhite, % | Current Axis I Diagnosis, % | Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trials contributing to the meta-analyses (n = 16) | ||||||||

| Psychological interventions (n = 5) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Dingemans et al., 2007 (45); Netherlands | G1: CBT-TL*; 30 G2: Waitlist; 22 |

20 weeks | 38.8 (10.4) 36.4 (11.3) |

NR | 94.23 | NR | Mood disorder: 16 Anxiety: 17 |

Medium |

|

| ||||||||

| Eldredge et al., 1997 (46); United States | G1: CBT-TL†; 36 G2: Waitlist; 10 |

12 weeks | 45.2 | 38.4 | 96 | NR | NR | Medium |

|

| ||||||||

| Peterson et al., 1998 (47); United States | G1: CBT-TL‡; 16 G2: CBT-PTL§; 19 G3: CBTssh ||; 15 G4: Waitlist; 11 |

8 weeks | 42.4 | 34.7 | 100 | 4 | NR | Medium |

|

| ||||||||

| Peterson et al., 2009 (48); United States | G1: CBT-TL‡; 60 G2: CBT-PTL§; 63 G3: CBTssh ||; 67 G4: Waitlist; 69 |

20 weeks | 47.1 | 39 | 88 | 4 | NR | Medium |

|

| ||||||||

| Tasca et al., 2006 (44); Canada | G1: PIPT-TL¶; 48 G2: CBT-TL**; 47 G3: Waitlist; 40 |

16 weeks | 42.8 | 41.1 | 91 | 2 | Mood disorder: 64.7 | Medium |

|

| ||||||||

| Pharmacologic interventions (n = 11) | ||||||||

| Arnold et al., 2002 (53); United States | G1: Fluoxetine, 80 mg/day; 30 G2: Placebo; 30 |

6 weeks | 41.9 (9.7) 40.8 (9.0) |

39.6 (7.0) 36.7 (6.8) |

93 93 |

10 13 |

MDD: 25 | Medium |

|

| ||||||||

| Grilo et al., 2005 (54); United States | G1: Fluoxetine, 60 mg/day; 27 G2: Placebo; 27 G3: CBT + fluoxetine††; 26 G4: CBT + placebo††; 28 |

16 weeks | 44 | 36.3 | 78 | 11 | NR | Low |

|

| ||||||||

| Guerdjikova et al., 2008 (58); 2008 (58); United States | G1: Escitalopram, 30 mg/day; 21 G2: Placebo; 23 |

12 weeks | 39 | 40.2 | 96 | 27 | NR | Low |

|

| ||||||||

| Guerdjikova et al., 2012 (57); United States | G1: Duloxetine, flexible dose to max 120 mg/day; 20 G2: Placebo; 20 |

12 week | 40.1 | 40.6 | 88 | 17 | Low | |

|

| ||||||||

| Hudson et al., 1998 (59); United States | G1: Fluvoxamine, 300 mg/day; 42 G2: Placebo; 43 |

9 weeks | 42 | 35.5 | 91 | 4 | NR | Medium |

|

| ||||||||

| McElroy et al., 2000 (60); United States | G1: Sertraline, 50 to 200 mg/day; 18 G2: Placebo; 16 |

6 weeks | 42 | 36.1 | 94 | NR | NR | Medium |

|

| ||||||||

| McElroy et al., 2003 (56); United States | G1: Citalopram, 60 mg/day; 19 G2: Placebo; 19 |

6 weeks | 40.6 | 37.8 | 95 | 13 | Depression: 32 | Low |

|

| ||||||||

| McElroy et al., 2015 (49); United States | G1: Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate, 30 mg/day; 66 G2: Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate, 50 mg/day; 65 G3: Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate, 70 mg/day; 65 G4: Placebo; 64 |

11 weeks | 39 | 34.9 | 82 | 22 | NR | Medium |

|

| ||||||||

| ClinicalTrials.gov, 2014 (50) and McElroy et al., 2016 (study 1) (52); United States, Germany, Sweden, and Spain | G1: Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate, 50 or 70 mg/day as tolerated to optimal clinical dose; 192 G2: Placebo; 191 |

12 weeks | 38 | 33 | 87 | 22 | NR | Low |

|

| ||||||||

| ClinicalTrials.gov, 2015 (51) and McElroy et al., 2016 (study 2) (52); United States and Germany | G1: Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate, 50 or 70 mg/day as tolerated to optimal clinical dose; 195 G2: Placebo; 195 |

12 weeks | 38 | 34 | 85 | 27 | NR | Low |

|

| ||||||||

| White and Grilo, 2013 (55); United States | G1: Bupropion, 300 mg/day; 31 G2: Placebo; 30 |

8 weeks | 44.1 | 35.8 | 100 | 16 | NR | Low |

|

| ||||||||

| Trials not contributing to the (n = 20) | ||||||||

| Psychological interventions (n = 6) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Carrard et al., 2011 (61); Switzerland | G1: CBTgsh‡‡; 37 G2: Waitlist; 37 |

6 months | 36 | 28.8 | 100 | NR | NR | Medium |

|

| ||||||||

| Carter and Fairburn, 1998 (62); United Kingdom | G1: CBTpsh§§; 24 G2: CBTgsh || ||; 24 G3: Waitlist; 24 |

12 weeks | 39.7 | 31.6 | 100 | 3 | NR | Medium |

|

| ||||||||

| Tasca et al., 2012 (94) (follow-up to Tasca et al., 2006, [44]); Canada | G1: PIPT-TL¶; 48 G2: CBT-TL**; 47 G3: Waitlist; 40 |

16 weeks | 42.8 | 41.1 | 91 | 2 | Mood disorder: 64.7 | Medium |

|

| ||||||||

| Peterson et al., 2001 (95) (follow-up to Peterson et al., 1998 [47]); United States | G1: CBT-TL‡; 60 G2: CBT-PTL§; 63 G3: CBTssh ||; 67 G4: Waitlist; 69 |

20 weeks | 47.1 | 39 | 88 | 4 | NR | Medium |

|

| ||||||||

| Grilo et al., 2013 (96); United States | G1: CBTpsh + usual care¶¶; 24 G2: Usual care; 24 |

16 weeks | 45.8 | 37.6 | 79.2 | 54.2 | NR | Low |

|

| ||||||||

| Masson et al., 2013 (97); Canada | G1: DBTgsh; 30 G2: Waitlist; 30 |

13 weeks | 42.8 (10.5) | 37.9 | 88.3 | 8.4 | NR | Medium |

| Pharmacologic interventions (n = 8) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Brownley et al., 2013 (98); United States | G1: Chromium, 1,000 μg/day; 8 G2: Chromium, 600 μg/day; 9 G3: Placebo; 7 |

6 months | 36.6 | 34.2 | 83 | 12 | NR | Medium |

|

| ||||||||

| Guerdjikova et al., 2009 (99); United States | G1: Lamotrigine, mean dose 236 mg/day; 26 G2: Placebo; 25 |

16 weeks | 44.5 | 40.1 | 76.5 | 80 | Depressive disorders: 37.2 | Medium |

|

| ||||||||

| McElroy et al., 2011 (100); United States | G1: Acamprosate, 666 mg/day; 20 G2: Placebo; 20 |

10 weeks | 46 | 39.5 | 85 | 12.5 | NR | Medium |

|

| ||||||||

| McElroy et al., 2013 (101); United States | G1: ALKS-33, 10 mg/day as tolerated; 32 G2: Placebo; 37 |

6 weeks | 45.2 | 39 | 90 | 19 | NR | Medium |

|

| ||||||||

| McElroy et al., 2015 (102), USA | G1: Armodafinil, mean dose 216.7 mg/day; 30 G2: Placebo, mean dose 208.9 mg/day; 30 |

10 weeks | 41.3 | 40.1 | 85 | 23 | NR | Medium |

|

| ||||||||

| McElroy et al., 2007 (103); United States | G1: Atomoxetine, mean dose 106 mg/day; 20 G2: Placebo; 20 |

10 weeks | 41.1 | 39.3 | 82.5 | 15 | Depressive disorders: 15 | Medium |

|

| ||||||||

| McElroy et al., 2003 (64); United States | G1: Topiramate, median dose 212 mg/day; 30 G2: Placebo, median dose 362 mg/day; 31 |

14 weeks | 40.8 | NR | 87 | NR | Mood disorder: 15 | Medium |

|

| ||||||||

| McElroy et al., 2007 (63); United States | G1: Topiramate, median dose 300 mg/day; 195 G2: Placebo, median dose 400 mg/day; 199 |

16 weeks | 44.5 | 38.5 | 84.2 | 21.5 | NR | Medium |

| Combination interventions (n = 6) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Claudino et al., 2007 (104); Brazil | G1: CBT + topiramate, maximum dose 300 mg/day; 37 G2: CBT + placebo; 36 |

21 weeks | 38.3 | 37.4 | 96 | 43 | NR | Medium |

|

| ||||||||

| Devlin et al., 2005 (105); United States | G1: BWL + CBT + fluoxetine, 60 mg/day; 28 G2: BWL + CBT + placebo; 25 G3: BWL + fluoxetine; 32 G4: BWL + placebo; 31 |

5 months | 43 | 40.9 | 78 | 23 | Major depression: 10.3 | Medium |

|

| ||||||||

| Golay et al., 2005 (106); Switzerland | G1: HC diet + orlistat, 120 mg 3 times/day; 44 G2: HC diet + placebo; 45 |

24 weeks | 41 | 36.5 | 91 | NR | NR | Low |

|

| ||||||||

| Grilo, et al., 2005 (107); United States | G1: CBTgsh + orlistat, 120 mg 3 times/day; 25 G2: CBTgsh + placebo; 25 |

12 weeks | 47 | 36 | 88 | 12 | NR | Low |

|

| ||||||||

| Grilo and White, 2013 (108); United States | G1: BWL + orlistat, 120 mg 3 times/day; 20 G2: BWL + placebo; 20 |

4 months | 45.8 | 38.1 | 78 | NR | NR | Low |

|

| ||||||||

| Laederach-Hofmann et al., 1999 (109); Switzerland | G1: Individual diet counseling + group psychological support + imipramine: 25 mg 3 times/day; 15 G2: Individual diet counseling + group psychological support + placebo: same dosing as active treatment; 16 |

8 weeks | 38.1 | 39.8 | 87 | NR | NR | Medium |

BED = binge-eating disorder; BMI = body mass index; BWL = behavioral weight loss; CBT = cognitive behavioral therapy; CBTgsh = cognitive behavioral therapy, guided self-help; CBTpsh = cognitive behavioral therapy, pure self-help; CBT-PTL = cognitive behavioral therapy, partially therapist-led; CBTssh = cognitive behavioral therapy, structured self-help; CBT-TL = cognitive behavioral therapy, therapist-led; DBTgsh = dialectical behavior therapy, guided self-help; G = group; HC = hypocaloric; MDD = major depressive disorder; NR = not reported; PIPT-TL = psychodynamic interpersonal psychotherapy, therapist-led.

Fifteen 2-h manualized (93) group sessions in Dutch.

Twelve 90-min manualized (110) group sessions.

Fourteen 60-min manualized (111) group sessions with 30-min therapist-led manualized psychoeducation and 30-min therapist-led discussion.

Fourteen 60-min manualized (111) group sessions with 30-min manualized psychoeducation through videotape and 30-min therapist-led discussion.

Fourteen 60-min manualized (111) group sessions with 30 min manualized psychoeducation through videotape and 30-min led by a group member assigned to facilitate group discussion.

Sixteen 90-min manualized (Tasca GA, Mikail S, Hewitt P. Group psychodynamic interpersonal psychotherapy: a manual for time limited treatment of binge eating disorder. Unpublished manuscript.) weekly group sessions.

Sixteen 90-min manualized (Wilfley DE, Stein RI, Friedman MA, Beren SA, Wiseman CV. Group cognitive-behavioral therapy for binge eating disorder. Unpublished manuscript.) weekly group sessions.

Sixteen weeks of individual, 60-min sessions using method of Fairburn et al. (112) plus 60 mg/day fluoxetine or placebo; CBT + fluoxetine gruop included in assessment of combination treatments.

Internet-guided; 11 sequential CBT modules + weekly e-mail contact with a coach; conducted in French; to be completed within 6 mo.

Individual provided with manual (113) and told to follow its self-help program independently.

Individual provided with manual (113) plus support from nonspecialist therapists in six to eight 25-min sessions.

Participants were instructed to follow the advice and treatment recommendations of their primary care physician but received no specific intervention for BED.

Most trials (26 of 34) were conducted in the United States; the mean age ranged from 36 to 47 years, and most participants were female (≥77%), white, and overweight or obese (mean BMI, 28.8 to 41.1 kg/m2). Trial sizes ranged from 24 to 394 randomly assigned participants, and treatment lasted 6 weeks to 6 months. Post-treatment follow-up assessments of the randomly assigned sample occurred in only 5 trials. Most studies excluded individuals receiving psychotropic medications; participants generally reported low to moderate levels of depression symptoms at baseline.

Sixteen trials contributed to the meta-analyses of key outcomes: 5 evaluated therapist-led CBT (44–48), 3 studied lisdexamfetamine (49–52), and 8 examined SGAs (fluoxetine, 60 mg/d [53] or 80 mg/d [54]; bupropion [55]; citalopram [56]; duloxetine [57]; escitalopram [58]; fluvoxamine [59]; and sertraline [60]). In these trials, 342 participants were randomly assigned to therapistled CBT or a waitlist, 416 to an antidepressant or placebo, and 983 to lisdexamfetamine or placebo. Of 583 patients randomly assigned to the lisdexamfetamine groups, our analysis included 517 who received at least 50 mg/d, because this is the minimum dosage approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for BED treatment. We qualitatively synthesized data for additional outcomes from these as well as the remaining 18 trials.

Outcomes

For each outcome, we first present the meta-analytic results in the text and supporting figures, then present the results of trials not included in the meta-analysis. Table 2 summarizes the qualitative findings for each trial, including the SOE grade for differences (or no differences) between interventions and comparators, which was low or moderate for all findings except one: weight reduction with lisdexamfetamine. Outcomes with insufficient SOE are not mentioned but may be found in the main report (38).

Table 2.

Treatment Effectiveness for Binge-Eating Disorder: Qualitative Synthesis Results

| Intervention and Outcome | Reference | Trials, n | Participants, n | Summary of Findings Measured at the End of Treatment | Strength of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abstinence from binge eating | |||||

|

| |||||

| CBT-PTL | 47, 48 | 2 | 162 | Greater percentage achieved abstinence with CBT-PTL vs. waitlist: 68.8% vs. 12.5% (47)†; 33% vs. 10% (48)† | Low for benefit |

|

| |||||

| CBTgsh | 61, 62 | 2 | 122 | Greater percentage achieved abstinence with CBTgsh vs. waitlist: 35.1% vs. 8.1% (61)†; 50% vs. 8% (62)† | Low for benefit |

|

| |||||

| Topiramate | 63, 64 | 2 | 468 | Greater percentage achieved abstinence with topiramate vs. placebo: 58% vs. 29% (63)†; 64% vs. 30% (64)† | Moderate for benefit |

|

| |||||

| Binge-eating frequency | |||||

| CBT-TL | 45, 47, 48 | 3 | 208 | Greater change in episodes/wk with CBT-TL vs. waitlist: −9.3 vs. −1.6 (45); −2.7 vs. +1.2 (47)†; −18.3 vs. −5.5 (48)† | Moderate for benefit |

|

| |||||

| CBT-PTL | 47, 48 | 2 | 162 | Greater reduction in episodes/wk with CBT-PTL vs. waitlist: −4.2 vs. +1.2 (47)†; −12.2 vs. −5.5 (48)† | Low for benefit |

|

| |||||

| CBTssh | 47, 48 | 2 | 162 | Greater reduction in episodes/wk with CBTssh vs. waitlist: −2.7 vs. +1.2 (47)†; −10.5 vs. −5.5 (48)† | Low for benefit |

|

| |||||

| CBTgsh | 61, 62 | 2 | 122 | Greater reduction in episodes/wk with CBTgsh vs. waitlist: −11.9 vs. −5.7 (61)†; −13.5 vs. −8.1 (62)† | Low for benefit |

|

| |||||

| Topiramate | 63, 64 | 2 | 468 | Greater reduction in episodes/wk with topiramate vs. placebo: −5.0 vs. −3.4 (63); −5.0 vs. −2.9 (64)† | Moderate for benefit |

| Eating-related psychopathology | |||||

|

| |||||

| CBT-TL | 44–48 | Greater improvement with CBT-TL vs. waitlist based on consistent changes across key measures of eating-related psychopathology | Moderate for benefit | ||

| 2 | 181 | Decrease in EDE global score: −1.1 vs. 0 (45)†; −0.7 vs. −0.3 (48) | |||

| 3 | 263 | Decrease in TFEQ hunger: −1.50 vs. −0.30 (48); −2.29 vs. +0.13 (46); −2.59 vs. −0.41 (44).† A fourth study (47) reported a statistically significant difference but no data. | |||

| 2 | 175 | Decrease in TFEQ disinhibition: −2.40 vs. −0.20 (48)†; −2.96 vs. −1.00 (46).† A third study (47) reported a statistically significant difference but no data. | |||

| 3 | 263 | Increase in TFEQ cognitive restraint: 1.83 vs. −1.67 (44)†; 1.90 vs. 0.10 (48); 2.74 vs. 2.50 (46). A fourth study (47) reported a statistically nonsignificant difference but no data. | |||

|

| |||||

| CBTgsh | 61, 62 | 2 | 122 | Greater decrease in EDE-Q global score with CBTgsh vs. waitlist: −1.1 vs. −0.4 (61)†; −1.5 vs. −0.1 (62)† | Low for benefit |

|

| |||||

| Topiramate | 63, 64 | 2 | 468 | Greater decrease in YBOCS-BE total score with topiramate vs. placebo: −14.3 vs. −7.9 (63)†; authors reported greater rate of reduction (P < 0.001) (64) | Moderate for benefit |

|

| |||||

| Symptoms of depression and other psychological and psychosocial outcomes | |||||

| CBT-TL | 44–48 | CBT-TL not superior to waitlist for reducing depression symptoms based on the following differences (4 of 5 differences were statistically nonsignificant) | Low for no difference | ||

| 2 | 98 | BDI: −4.5 vs. −6.5 (46); −7.8 vs. −0.3 (45)† | |||

| 1 | 27 | HDRS: −5.0 vs. NR (authors reported no difference; P = 0.58) (47) | |||

| 1 | 129 | IDS-SR: −4.4 vs. −3.1 (48) | |||

| 1 | 88 | CESD: −6.16 vs. −0.54 (44) | |||

|

| |||||

| CBT-PTL | 47, 48 | CBT-PTL not superior to waitlist for reducing depression symptoms based on the following statistically nonsignificant differences | Low for no difference | ||

| 1 | 30 | HDRS: −5.5 vs. NR (authors reported no difference; P = 0.58) (47) | |||

| 1 | 132 | IDS-SR: −2.7 vs. −3.1 (48) | |||

|

| |||||

| CBTssh | 47, 48 | CBTssh not superior to waitlist for reducing depression symptoms based on the following statistically nonsignificant differences | Low for no difference | ||

| 1 | 26 | HDRS: −4.5 vs. NR (authors reported no difference; P = 0.58) (47) | |||

| 1 | 136 | IDS-SR: −3.3 vs. −3.1 (48) | |||

| Weight and weight-related outcomes | |||||

|

| |||||

| CBT-TL | 44–48 | 5 | 342 | CBT-TL (range, −0.1 to +1.6) not statistically significantly different than waitlist (range, −0.95 to +0.20) for reducing BMI | Moderate for no difference |

|

| |||||

| CBT-PTL | 47, 48 | 2 | 162 | CBT-PTL not statistically significantly different than waitlist for reducing BMI: +0.4 vs. NR (authors reported no difference; P = 0.127) (47); −0.1 vs. +0.2 (48) | Low for no difference |

|

| |||||

| CBTssh | 47, 48 | 2 | 162 | CBTssh not statistically significantly different than waitlist for reducing BMI: −4.5 vs. NR (authors reported no difference; P = 0.127) (47); −3.3 vs. −3.1 (48) | Low for no difference |

|

| |||||

| Lisdexamfetamine* | 49, 52 | 3 | 966 | Greater percentage weight loss with 50 or 70 mg/d lisdexamfetamine than with placebo. Study 1 (49): −5.2%†; study 2 (52): −6.35%†; study 3 (52): −5.41%† | High for benefit |

| 2 | 724 | Greater reduction in triglycerides with 50 or 70 mg/d lisdexamfetamine vs. placebo. Study 2 (52): −0.199 mmol/L (95% CI, −0.310 to −0.088 mmol/L)†; study 3 (52): −0.196 mmol/L (CI, −0.321 to −0.0070 mmol/L)† | Moderate for benefit | ||

|

| |||||

| Topiramate* | 63, 64 | 2 | 468 | Greater weight loss with topiramate vs. placebo: −4.5 vs. +0.2 kg (63)†; −5.9 vs. −1.2 kg (64)† | Moderate for benefit |

BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; BMI = body mass index; CBTgsh = cognitive behavioral therapy, guided self-help; CBT-PTL = cognitive behavioral therapy, partially therapist-led; CBTssh = cognitive behavioral therapy, structured self-help; CBT-TL = cognitive behavioral therapy, therapist-led; CESD = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (65); EDE = Eating Disorder Examination (66); EDE-Q = Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (67); HDRS = Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (68); IDS-SR = Inventory of Depressive Symptoms Self-Report (69, 70); NR = not reported; TFEQ = Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (71); YBOCS-BE = Yale–Brown Obsessions and Compulsions Scale, adapted for binge eating (72, 73).

To convert triglyceride levels to mg/dL, divide by 0.0113.

Treatment difference was reported by the study authors to be statistically significant.

Binge-Eating Outcomes

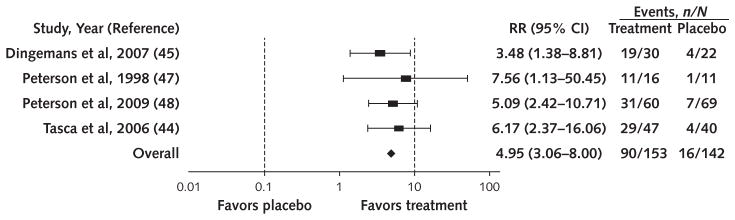

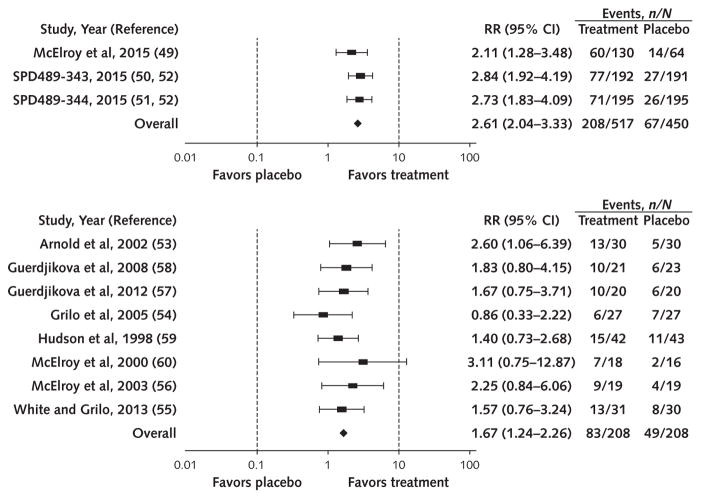

More participants achieved abstinence from binge eating with therapist-led CBT versus waitlist (58.8% vs. 11.2%; RR, 4.95 [95% CI, 3.06 to 8.00]; I2 = 0%; moderate SOE) (Figure 1), with lisdexamfetamine versus placebo (40.2% vs. 14.9%; RR, 2.61 [CI, 2.04 to 3.33]; I2 = 0%; high SOE) (Figure 2, top), and with SGAs versus placebo (39.9% vs. 23.6%; RR, 1.67 [CI, 1.24 to 2.26]; I2 = 0%; moderate SOE) (Figure 2, bottom). In addition, binge-eating frequency decreased with lisdexamfetamine (3 trials; MD in days/week −1.35 [CI, −1.77 to −0.93]; I2 = 99.68; high SOE) and SGAs (7 trials; MD in episodes/week, −0.67 [CI, −1.26 to −0.09]; moderate SOE; I2 = 0%; 3 trials; MD in days/week, −0.90 [CI, −1.48 to −0.32]; I2 = 0%; low SOE). On the basis of qualitative syntheses, partially therapist-led CBT, guided self-help CBT, and topiramate increased binge-eating abstinence and reduced binge-eating frequency, and therapist-led CBT and structured self-help CBT reduced binge-eating frequency (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Effect of therapist-led cognitive behavioral therapy on abstinence from binge eating.

RR = risk ratio.

Figure 2.

Effect of lisdexamfetamine, 50 or 70 mg/d (top), and second-generation antidepressants (bottom) on abstinence from binge eating.

RR = risk ratio.

Eating-Related Psychological Outcomes

Lisdexamfetamine (3 trials; MD, −6.50 [CI, −8.82 to −4.18]; I2 = 99.86; moderate SOE) and SGAs (3 trials; MD, −3.84 [CI, −6.55 to −1.13]; I2 = 44.11%; low SOE) reduced eating-related obsessions and compulsions. On the basis of qualitative analyses, topiramate decreased eating-related obsessions and compulsions and therapist-led CBT and guided self-help CBT consistently improved eating-related psychopathology, as reflected in participants’ susceptibility to hunger; cognitive control over eating; and overall concerns about eating, shape, and weight (Table 2).

Symptoms of Depression and Other Psychological and Psychosocial Outcomes

SGAs significantly reduced scores on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) (3 trials; MD, −1.97 [CI, −3.67 to −0.28]; I2 = 48.62%; low SOE). Although individual pretreatment HAM-D scores ranged from 0 to 52, mean levels ranged from 2.6 to 5.7, leaving little room for clinically meaningful improvement. CBT (whether delivered in therapist-led, partially therapist-led, or structured self-help format) did not statistically significantly reduce depression symptoms (Table 2).

Weight-Related Outcomes

Trials varied in reporting weight and BMI as outcomes. SGAs did not significantly reduce either BMI (6 trials; MD, −1.02 [CI, −2.62 to 0.59]; I2 = 0%) or weight (4 trials; MD in kilograms, −3.92 [CI, −10.16 to 2.33]; I2 = 0%) (low SOE for no difference for both outcomes). On the basis of qualitative syntheses, reductions in BMI did not differ significantly between patients on waitlist and those receiving therapist-led, partially therapist-led, or structured self-help CBT (Table 2). In contrast, compared with placebo, lisdexamfetamine and topiramate resulted in greater weight reductions (Table 2). Several trials reported on weight-related metabolic variables; however, evidence was sufficient only for lisdexamfetamine reducing triglyceride levels compared with placebo (Table 2).

Harms Associated With Treatment

No psychological treatment studies reported harms. Of the 25 placebo-controlled medication-only or medication-plus-psychological intervention trials reviewed here, 20 reported on harms. Most involved medication side effects widely documented in non-BED populations. Four serious adverse events occurred in the 3 lisdexamfetamine trials.

In pooled analyses of 3 trials, lisdexamfetamine led to more insomnia (RR, 2.80 [CI, 1.74 to 4.51]; I2 = 0%) and general sleep disturbances (RR, 2.19 [CI, 1.36 to 3.54]; I2 = 31.65%) (both high SOE), as well as more headaches (RR, 1.63 [CI, 1.13 to 2.36]; I2 = 0%), gastrointestinal upset (RR, 2.71 [CI, 1.14 to 6.44]; I2 = 69.37%), and sympathetic nervous system (SNS) arousal (RR, 4.28 [CI, 2.67 to 6.87]; I2 = 62.93%) (all moderate SOE). Qualitatively, the incidence of decreased appetite with lisdexamfetamine, SNS arousal with topiramate and flvoxamine, and gastrointestinal upset and sleep disturbance with fluvoxamine was greater than that observed with placebo (Appendix Table 4, available at www.annals.org).

Appendix Table 4.

Harms Associated With Treatments for Binge-Eating Disorder: Qualitative Synthesis Results*

| Harm and Intervention (Reference) | Trials, n | Participants, n | Events, n | Evidence and Events, n | Strength of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Headache | |||||

|

| |||||

| amine (59) | 1 | 85 | 70 | Drug: 42 Placebo: 28 |

Insufficient for no difference |

|

| |||||

| Topiramate (63, 64) | 2 | 468 | 73 | Drug: 37 Placebo: 36 |

Moderate for no difference |

| Sleep disturbance* | |||||

|

| |||||

| Fluvoxamine (59, 114) | 2 | 105 | 57 | Drug: 42 Placebo: 15 |

Low for harm |

|

| |||||

| Topiramate (63, 64) | 2 | 468 | 89 | Drug: 48 Placebo: 41 |

Moderate for no difference |

| Gastrointestinal upset | |||||

|

| |||||

| Fluvoxamine (59, 114) | 2 | 105 | 24 | Drug: 18 Placebo: 6 |

Low for harm |

|

| |||||

| Topiramate (63, 64) | 2 | 468 | 94 | Drug: 52 Placebo: 42 |

Moderate for no difference |

| Sympathetic nervous system arousal† | |||||

|

| |||||

| Fluvoxamine (59, 114) | 2 | 105 | 22 | Drug: 15 Placebo: 7 |

Low for harm |

|

| |||||

| Topiramate (63, 64) | 2 | 468 | 243 | Drug: 181 Placebo: 62 |

Moderate for harm |

| Decreased appetite | |||||

|

| |||||

| Lisdexamfetamine‡ (49, 52) | 3 | 938 | 66 | Drug: 53 Placebo: 13 |

Moderate for harm |

Insomnia plus other sleep disturbances (i.e., abnormal dreams, fatigue, sedation, somnolence, yawning).

Includes anxiousness, dry mouth, feeling jittery, increased blood pressure, increased heart rate, palpitations.

Among participants randomly assigned to 50 or 70 mg/d.

Treatment was discontinued infrequently, but approximately twice as often among patients assigned to medication alone or to a combined intervention (n = 98; 13 of whom had a serious adverse event) than in the placebo group (n = 43; 7 of whom had a serious adverse event). Participants dropped out of psychological trials most often because of dissatisfaction.

Discussion

This review contributes new knowledge from an expanded treatment evidence base that permitted estimates of treatment effect sizes and harms from pooled analyses of therapist-led CBT, lisdexamfetamine, and SGAs not provided in our 2006 AHRQ report (39) or in other recent reviews published before May 2016 (74–82). Our review included 15 new RCTs (4 with CBT, 11 with medication) but excluded trials of sibutramine (which no longer is available in the United States), as well as studies of zonisamide, atomoxetine, and fluvoxamine that we rated as high risk of bias. Our findings provide strong support for therapist-led CBT, lisdexamfetamine, and SGAs (as a group) in helping patients with BED reduce binge-eating frequency and achieve abstinence; with less confidence, they suggest similar benefits from topiramate and other forms of CBT. Effect estimates varied in magnitude and cannot be compared easily across treatments because we could not do pooled analyses on any single SGA and because the comparators for CBT and lisdexamfetamine differed (waitlist and placebo, respectively).

Patients seeking treatment for BED have various degrees of distress associated with binge eating–related obsessive thoughts and compulsions, worries about their shape and weight, and negative mood symptoms. With varying levels of certainty, our findings indicate that CBT in several formats, lisdexamfetamine, SGAs, and topiramate reduce these problems. The evidence from nearly 1000 patients was especially strong for lisdexamfetamine in reducing obsessions, compulsions, and weight. In overweight and obese individuals without BED, topiramate tends to induce weight loss (83), whereas SGAs tend to be weight-neutral (84), although individual responses to different SGAs may vary considerably. What remains unknown is whether reduced binge eating mediates weight loss in patients with BED treated with topiramate.

Despite the high levels of co-occurrence of BED with depression and other psychiatric conditions (85), we found no clear benefit of various forms of CBT in reducing symptoms of depression; limited evidence indicated a slight benefit with SGAs. This result may reflect 2 factors: Included trials generally comprised participants with low levels of negative mood symptoms at baseline (and not necessarily a clinical diagnosis of depression), and CBT was tailored to address problematic eating-related cognitions and behaviors unique to BED rather than global depressive cognitions and behaviors.

Although the number of serious treatment harms was extremely low, harms of any type, discontinuation of treatment attributed to harms, and the number of serious adverse events were approximately 2-fold greater among those receiving an active medication than among those receiving a placebo. Based on meta-analytic and qualitative results, harms occurred more frequently in patients treated with lisdexamfetamine, topiramate, or fluvoxamine than in those receiving a placebo. The most commonly reported harm in all trials, SNS arousal, occurred more than 4 times as frequently with lisdexamfetamine than placebo.

Clinicians should be aware of the potential for lisdexamfetamine to decrease appetite. Depending on a patient’s treatment goals and propensity toward food restriction, this side effect may be helpful or harmful and should be monitored closely. Cycling between dietary restraint and binge eating is common among individuals with BED (86–88); many restrict food intake during the day and binge eat in the evening. In addition, many individuals with BED experience deficits in appetite awareness (89, 90). Theoretically, the potential for harm may be greater among these groups.

In January 2015, lisdexamfetamine became the first (and only) drug approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treating patients with BED. A central nervous system stimulant and dextroamphetamine pro-drug, lisdexamfetamine is recognized widely as an effective treatment for reducing symptoms of impulsivity, inattention, and hyperactivity in children and adults with attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder, in whom it is well-tolerated with generally manageable side effects, such as dry mouth, restlessness, insomnia, and gastrointestinal upset (91). Our meta-analyses show tolerability and efficacy of lisdexamfetamine in BED, including clinically meaningful short-term reductions in binge-eating frequency and in obsessive thoughts and compulsions regarding binge eating. Because the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration classifies lisdexamfetamine as a Schedule II drug, individuals with a history of stimulant or other substance use disorder, suicide attempt, mania, or cardiac disease or abnormality were excluded from the trials; therefore, the results may not generalize to these BED populations.

In the United States, clinical practice guidelines tend to favor therapist-led CBT augmented with psychotropic medication (typically an antidepressant) as needed (29, 30). Many patients, however, have only limited access to BED-focused CBT with a BED-trained psychotherapist within a multidisciplinary team including a psychiatrist. The self-help approach recommended by NICE may be advantageous for overcoming this barrier to treatment access and increasing treatment dissemination. However, given the low SOE derived from our qualitative findings, recommending self-help CBT as first-line treatment would be premature. Our report cannot resolve the apparent discrepancy between the APA and NICE recommendations regarding when and how to integrate psychological, behavioral, and pharmacologic treatments for BED. Adequately powered head-to-head comparative effectiveness trials are needed to determine equivalence or noninferiority of self-help compared with therapist-led CBT.

Several limitations of the evidence base and review exist. The efficacy evidence base comprised only small samples or methodologically disparate single studies for nearly all medications, many psychological treatments, and all combination treatments. As a result, the evidence was insufficient to generate pooled estimates for self-help CBT or to evaluate the efficacy of specific antidepressants, promising interventions (such as interpersonal psychotherapy) (92, 93), complementary and alternative medicine or nutraceutical approaches, combination treatments (74, 82), or stepped-care strategies. Some trials had methodological limitations, including unclear randomization and allocation concealment, unmasked outcome assessors, and differential attrition between treatment groups. The instruments used to assess psychological outcomes, as well as how investigators reported outcomes, varied considerably. Moderate to high heterogeneity characterized the pooled estimates of some outcomes for some treatments, in several cases leading us to downgrade the SOE to moderate (for example, the effect of lisdexamfetamine on psychopathology and SNS arousal) or low (for example, the effect of SGAs on psychopathology). Studies did not report adverse events and discontinuations uniformly. Other limitations included trial setting (mainly supervised outpatient settings in U.S. academic research and medical centers) and population (mostly overweight or obese, 20- to 40-year-old white women with low levels of depression and anxiety), preventing us from assessing the effect of important patient characteristics, such as race, body weight, or presence of psychological or medical comorbidity, on treatment efficacy. Although publication bias and selective reporting were possible, many statistically nonsignificant results were reported in the trials, and a review of a sample of non-English abstracts (n = 358) and articles (n = 9) did not suggest a language bias or that any important psychological and medication trials were missing. Lastly, as no pharmacologic studies had long-term follow-up, persistence of efficacy benefits beyond active treatment could not be evaluated.

Among adults with BED, strong evidence indicates that therapist-led CBT, lisdexamfetamine, and SGAs as a general class (mainly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) reduce the frequency of binge eating, increase the likelihood of achieving abstinence from binge eating, and improve other eating-related psychological outcomes. Similar but less compelling evidence shows a benefit from other forms of CBT and topiramate. Harms associated with lisdexamfetamine, SGAs, and topiramate rarely limited treatment. It is unclear whether these findings generalize to patients with BED beyond those included in these trials (chiefly, overweight or obese 20- to 40-year-old white women without psychological or medical comorbidity). Adequately powered trials are needed to evaluate the comparative long-term benefits of psychological and pharmacologic treatments. Given the high levels of association among BED, obesity, and depression, future studies should determine whether certain treatments are better suited for particular subsets of patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lauren Breithaupt and Margaret Sala for their assistance with abstract reviews. They acknowledge Isabelle Lanser, Michela Quaranta, Loraine Monroe, Laura Morgan, and Morgan Walker for their assistance with table development and manuscript preparation for this review. For their assistance with the report from which this manuscript was based, the authors also thank Meera Viswanathan, PhD; Ina F. Wallace, PhD; and Lynn Whitener, DrPH, MSLS.

Grant Support: By contract 290-2012-00008-U from AHRQ (all authors) and VR Dnr 538-2013-8864 from the Swedish Research Council (Dr. Bulik).

Footnotes

Reproducible Research Statement: Study protocol: Available at www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/search-for-guides-reviews-and-reports/?pageaction=displayproduct&productID=1942. Statistical code and data set: In Methods and Results sections, respectively; full report is available at www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/search-for-guides-reviews-and-reports/?pageaction=displayproduct&productID=2157.

Current author addresses and author contributions are available at www.annals.org.

Author Contributions: Conception and design: N.D. Berkman, C.M. Peat, K.E. Cullen, C.M. Bulik.

Analysis and interpretation of the data: K.A. Brownley, N.D. Berkman, C.M. Peat, K.N. Lohr, C.M. Bann, C.M. Bulik.

Drafting of the article: K.A. Brownley, N.D. Berkman, C.M. Peat, K.N. Lohr, K.E. Cullen, C.M. Bann.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: K.A. Brownley, N.D. Berkman, C.M. Peat, K.N. Lohr, C.M. Bulik.

Final approval of the article: K.A. Brownley, N.D. Berkman, C.M. Peat, K.N. Lohr, K.E. Cullen, C.M. Bann, C.M. Bulik.

Statistical expertise: C.M. Bann.

Obtaining of funding: K.A. Brownley, N.D. Berkman, C.M. Peat, K.N. Lohr, C.M. Bulik.

Administrative, technical, or logistic support: N.D. Berkman, K.N. Lohr, K.E. Cullen.

Collection and assembly of data: K.A. Brownley, N.D. Berkman, C.M. Peat, K.E. Cullen, C.M. Bulik.

Disclosures: Dr. Brownley reports grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality during the conduct of the study, and personal fees from Shire and Sunovion Pharmaceuticals outside the submitted work. Dr. Lohr was an employee of RTI International–University of North Carolina Evidence-Based Practice Center during the conduct of the study; received consulting fees from ECRI Institute outside the submitted work; and is vice president (unpaid) for PROMIS (Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System), a 501(c)(3) foundation to support development and dissemination of patient-reported outcomes measurement systems. Dr. Bulik reports grants from Shire, personal fees from Ironshore, and textbook royalties from Pearson, outside the submitted work. Dr. Peat reports grants from Shire and membership on the BED advisory board of Sunovion Pharmaceuticals. Authors not named here have disclosed no conflicts of interest. Disclosures can be viewed at www.acponline.org/authors/icmje/ConflictOfInterestForms.do?msNum=M15-2455.

References

- 1.Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Jr, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:348–58. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alegria M, Woo M, Cao Z, Torres M, Meng XL, Striegel-Moore R. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in Latinos in the United States. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40(Suppl):S15–21. doi: 10.1002/eat.20406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicdao EG, Hong S, Takeuchi DT. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders among Asian Americans: results from the National Latino and Asian American Study. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40(Suppl):S22–6. doi: 10.1002/eat.20450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruce B, Wilfley D. Binge eating among the overweight population: a serious and prevalent problem. J Am Diet Assoc. 1996;96:58–61. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(96)00016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spitzer RL, Yanovski S, Wadden T, Wing R, Marcus MD, Stunkard A, et al. Binge eating disorder: its further validation in a multisite study. Int J Eat Disord. 1993;13:137–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grucza RA, Przybeck TR, Cloninger CR. Prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder in a community sample. Compr Psychiatry. 2007;48:124–31. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stice E, Marti CN, Rohde P. Prevalence, incidence, impairment, and course of the proposed DSM-5 eating disorder diagnoses in an 8-year prospective community study of young women. J Abnorm Psychol. 2013;122:445–57. doi: 10.1037/a0030679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swanson SA, Crow SJ, Le Grange D, Swendsen J, Merikangas KR. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in adolescents. Results from the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:714–23. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guerdjikova AI, O’Melia AM, Mori N, McCoy J, McElroy SL. Binge eating disorder in elderly individuals. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45:905–8. doi: 10.1002/eat.22028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Pub; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marek RJ, Ben-Porath YS, Ashton K, Heinberg LJ. Impact of using DSM-5 criteria for diagnosing binge eating disorder in bariatric surgery candidates: change in prevalence rate, demographic characteristics, and scores on the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory—2 restructured form (MMPI-2-RF) Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47:553–7. doi: 10.1002/eat.22268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trace SE, Thornton LM, Root TL, Mazzeo SE, Lichtenstein P, Pedersen NL, et al. Effects of reducing the frequency and duration criteria for binge eating on lifetime prevalence of bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder: implications for DSM-5. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45:531–6. doi: 10.1002/eat.20955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Javaras KN, Pope HG, Lalonde JK, Roberts JL, Nillni YI, Laird NM, et al. Co-occurrence of binge eating disorder with psychiatric and medical disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:266–73. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Chiu WT, Deitz AC, Hudson JI, Shahly V, et al. The prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73:904–14. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kessler RC, Shahly V, Hudson JI, Supina D, Berglund PA, Chiu WT, et al. A comparative analysis of role attainment and impairment in binge-eating disorder and bulimia nervosa: results from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2014;23:27–41. doi: 10.1017/S2045796013000516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whisman MA, Dementyeva A, Baucom DH, Bulik CM. Marital functioning and binge eating disorder in married women. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45:385–9. doi: 10.1002/eat.20935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hudson JI, Lalonde JK, Coit CE, Tsuang MT, McElroy SL, Crow SJ, et al. Longitudinal study of the diagnosis of components of the metabolic syndrome in individuals with binge-eating disorder. Am J ClinNutr. 2010;91:1568–73. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herpertz S, Albus C, Wagener R, Kocnar M, Wagner R, Henning A, et al. Comorbidity of diabetes and eating disorders. Does diabetes control reflect disturbed eating behavior? Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1110–6. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.7.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meneghini LF, Spadola J, Florez H. Prevalence and associations of binge eating disorder in a multiethnic population with type 2 diabetes [Letter] Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2760. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kenardy J, Mensch M, Bowen K, Green B, Walton J, Dalton M. Disordered eating behaviours in women with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eat Behav. 2001;2:183–92. doi: 10.1016/s1471-0153(01)00028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Jonge P, Alonso J, Stein DJ, Kiejna A, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Viana MC, et al. Associations between DSM-IV mental disorders and diabetes mellitus: a role for impulse control disorders and depression. Diabetologia. 2014;57:699–709. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-3157-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raevuori A, Suokas J, Haukka J, Gissler M, Linna M, Grainger M, et al. Highly increased risk of type 2 diabetes in patients with binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48:555–62. doi: 10.1002/eat.22334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davidson KM. Eating disorders and diabetes: current perspectives. Can J Diabetes. 2003;27:62–73. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gagnon C, Aimé A, Bélanger C, Markowitz JT. Comorbid diabetes and eating disorders in adult patients: assessment and considerations for treatment. Diabetes Educ. 2012;38:537–42. doi: 10.1177/0145721712446203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rotella F, Cresci B, Monami M, Aletti V, Andreoli V, Ambrosio ML, et al. Are psychopathological features relevant predictors of glucose control in patients with type 2 diabetes? A prospective study. Acta Diabetol. 2012;49(Suppl 1):S179–84. doi: 10.1007/s00592-012-0403-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Colles SL, Dixon JB, O’Brien PE. Loss of control is central to psychological disturbance associated with binge eating disorder. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:608–14. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Zwaan M, Hilbert A, Swan-Kremeier L, Simonich H, Lancaster K, Howell LM, et al. Comprehensive interview assessment of eating behavior 18–35 months after gastric bypass surgery for morbid obesity. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.White MA, Kalarchian MA, Masheb RM, Marcus MD, Grilo CM. Loss of control over eating predicts outcomes in bariatric surgery patients: a prospective, 24-month follow-up study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:175–84. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04328blu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yager J, Devlin MJ, Halmi KA, Herzog DB, Mitchell JE, Powers P, et al. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Eating Disorders. 3. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Assoc; 2006. pp. 1–128. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yager J, Devlin M, Halmi K, Herzog D, Mitchell J, Powers P, et al. Guideline Watch (August 2012): Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Eating Disorders. 3. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Assoc; 2012. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Eating disorders in over 8s: management. [on 18 November 2014];Guidance. Accessed at http://publications.nice.org.uk/eating-disorders-cg9/guidance#atypical-eating-disorders-including-binge-eating-disorder.

- 32.National Task Force on the Prevention and Treatment of Obesity. Dieting and the development of eating disorders in overweight and obese adults. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2581–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.17.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bacon L. Health at Every Size: The Surprising Truth About Your Weight. 2. Dallas, TX: BenBella Books; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34.North Carolina Division of Health and Human Services Division of Medical Assistance. Surgery for clinically severe or morbid obesity. [on 7 June 2016];Medicaid and Health Choice clinical coverage policy no: 1A-15. Amended date: October 1, 2015. Accessed at https://ncdma.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/documents/files/1a15.pdf.

- 35.Emblem Health. [on 15 September 2015];Bariatric surgery. Accessed at www.emblemhealth.com/~/media/Files/PDF/_med_guidelines/MG_Bariatric_SX_c.pdf.

- 36.BlueCross BlueShield of Vermont. [on 5 September 2015];Bariatric surgery for morbid obesity: corporate medical policy. Accessed at www.bcbsvt.com/wps/wcm/connect/127c1a42-c47d-43ac-82b8-2723ea0bc498/med-policy-bariatric-surgery-2013.pdf?MOD=AJPERES.

- 37.Aetna. [on 5 September 2015];Obesity surgery. Accessed at www.aetna.com/cpb/medical/data/100_199/0157.html.

- 38.RTI International–University of North Carolina Evidence-Based Practice Center. Management and Outcomes of Binge-Eating Disorder. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2015. Comparative Effectiveness Review no. 160. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berkman ND, Bulik CM, Brownley KA, Lohr KN, Sedway JA, Rooks A, et al. Management of eating disorders. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) 2006:1–166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brownley KA, Berkman ND, Sedway JA, Lohr KN, Bulik CM. Binge eating disorder treatment: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:337–48. doi: 10.1002/eat.20370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berkman ND, Brownley KA, Peat CM, Cullen KE. Evidence-based practice center systematic review protocol. [on 5 September 2015];Project title: Management and outcomes of binge eating disorder (BED) Accessed at www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/563/1942/binge-eating-protocol-140721.pdf.

- 42.Berkman ND, Lohr KN, Ansari MT, Balk EM, Kane R, McDonagh M, et al. Grading the strength of a body of evidence when assessing health care interventions: an EPC update. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68:1312–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berkman ND, Lohr KN, Ansari M, McDonagh M, Balk E, Whitlock E, et al. Methods Guide for Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2013. Grading the Strength of a Body of Evidence When Assessing Health Care Interventions for the Effective Health Care Program of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: An Update. (Prepared by the RTI–UNC Evidence-Based Practice Center under contract no. 290-2007-10056-I) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tasca G, Ritchie K, Conrad G, Balfour L, Gayton J, Lybanon V, et al. Attachment scales predict outcome in a randomized controlled trial of two group therapies for binge eating disorder: an aptitude by treatment interaction. Psychother Res. 2006;16:106–21. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dingemans AE, Spinhoven P, van Furth EF. Predictors and mediators of treatment outcome in patients with binge eating disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:2551–62. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eldredge KL, Stewart Agras W, Arnow B, Telch CF, Bell S, Castonguay L, et al. The effects of extending cognitive-behavioral therapy for binge eating disorder among initial treatment nonresponders. Int J Eat Disord. 1997;21:347–52. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(1997)21:4<347::aid-eat7>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peterson CB, Mitchell JE, Engbloom S, Nugent S, Mussell MP, Miller JP. Group cognitive-behavioral treatment of binge eating disorder: a comparison of therapist-led versus self-help formats. Int J Eat Disord. 1998;24:125–36. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199809)24:2<125::aid-eat2>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peterson CB, Mitchell JE, Crow SJ, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA. The efficacy of self-help group treatment and therapist-led group treatment for binge eating disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:1347–54. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09030345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McElroy SL, Hudson JI, Mitchell JE, Wilfley D, Ferreira-Cornwell MC, Gao J, et al. Efficacy and safety of lisdexamfetamine for treatment of adults with moderate to severe binge-eating disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:235–46. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. [on 15 April 2015];Forced-Dose Titration of SPD489 in Adults With Binge Eating Disorder (BED) [clinical trial] Accessed at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01291173.

- 51. [on 15 April 2015];SPD489 in Adults Aged 18–55 Years With Moderate to Severe Binge Eating Disorder [clinical trial] Accessed at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01718483.

- 52.McElroy SL, Hudson J, Ferreira-Cornwell MC, Radewonuk J, Whitaker T, Gasior M. Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate for adults with moderate to severe binge eating disorder: results of two pivotal phase 3 randomized controlled trials. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41:1251–60. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arnold LM, McElroy SL, Hudson JI, Welge JA, Bennett AJ, Keck PE. A placebo-controlled, randomized trial of fluoxetine in the treatment of binge-eating disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:1028–33. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy and fluoxetine for the treatment of binge eating disorder: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled comparison. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:301–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.White MA, Grilo CM. Bupropion for overweight women with binge-eating disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74:400–6. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m08071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McElroy SL, Hudson JI, Malhotra S, Welge JA, Nelson EB, Keck PE., Jr Citalopram in the treatment of binge-eating disorder: a placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:807–13. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guerdjikova AI, McElroy SL, Winstanley EL, Nelson EB, Mori N, McCoy J, et al. Duloxetine in the treatment of binge eating disorder with depressive disorders: a placebo-controlled trial. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45:281–9. doi: 10.1002/eat.20946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guerdjikova AI, McElroy SL, Kotwal R, Welge JA, Nelson E, Lake K, et al. High-dose escitalopram in the treatment of binge-eating disorder with obesity: a placebo-controlled monotherapy trial. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2008;23:1–11. doi: 10.1002/hup.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hudson JI, McElroy SL, Raymond NC, Crow S, Keck PE, Jr, Carter WP, et al. Fluvoxamine in the treatment of binge-eating disorder: a multicenter placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1756–62. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.12.1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McElroy SL, Casuto LS, Nelson EB, Lake KA, Soutullo CA, Keck PE, Jr, et al. Placebo-controlled trial of sertraline in the treatment of binge eating disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1004–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carrard I, Crépin C, Rouget P, Lam T, Golay A, Van der Linden M. Randomised controlled trial of a guided self-help treatment on the Internet for binge eating disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49:482–91. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carter JC, Fairburn CG. Cognitive-behavioral self-help for binge eating disorder: a controlled effectiveness study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:616–23. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McElroy SL, Hudson JI, Capece JA, Beyers K, Fisher AC, Rosenthal NR Topiramate Binge Eating Disorder Research Group. Topiramate for the treatment of binge eating disorder associated with obesity: a placebo-controlled study. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:1039–48. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McElroy SL, Arnold LM, Shapira NA, Keck PE, Jr, Rosenthal NR, Karim MR, et al. Topiramate in the treatment of binge eating disorder associated with obesity: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:255–61. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cooper Z, Cooper PJ, Fairburn CG. The validity of the eating disorder examination and its subscales. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:807–12. doi: 10.1192/bjp.154.6.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Assessment of eating disorders: interview or self-report questionnaire? Int J Eat Disord. 1994;16:363–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Ibrahim HM, Carmody TJ, Biggs MM, Suppes T, et al. The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (IDS-C) and Self-Report (IDS-SR), and the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (QIDS-C) and Self-Report (QIDS-SR) in public sector patients with mood disorders: a psychometric evaluation. Psychol Med. 2004;34:73–82. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rush AJ, Giles DE, Schlesser MA, Fulton CL, Weissenburger J, Burns C. The Inventory for Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): preliminary findings. Psychiatry Res. 1986;18:65–87. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(86)90060-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stunkard AJ, Messick S. The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. J Psychosom Res. 1985;29:71–83. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(85)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Fleischmann RL, Hill CL, et al. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. I. Development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:1006–11. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110048007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Delgado P, Heninger GR, et al. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. II. Validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:1012–6. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110054008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Reas DL, Grilo CM. Review and meta-analysis of pharmacotherapy for binge-eating disorder. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:2024–38. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hay PP, Bacaltchuk J, Stefano S, Kashyap P. Psychological treatments for bulimia nervosa and binging. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD000562. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000562.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vocks S, Tuschen-Caffier B, Pietrowsky R, Rustenbach SJ, Kersting A, Herpertz S. Meta-analysis of the effectiveness of psychological and pharmacological treatments for binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2010;43:205–17. doi: 10.1002/eat.20696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stefano SC, Bacaltchuk J, Blay SL, Appolinário JC. Antidepres-sants in short-term treatment of binge eating disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eat Behav. 2008;9:129–36. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Perkins SJ, Murphy R, Schmidt U, Williams C. Self-help and guided self-help for eating disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD004191. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004191.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.McElroy SL, Guerdjikova AI, Mori N, Munoz MR, Keck PE. Overview of the treatment of binge eating disorder. CNS Spectr. 2015;20:546–56. doi: 10.1017/S1092852915000759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Amianto F, Ottone L, Abbate Daga G, Fassino S. Binge-eating disorder diagnosis and treatment: a recap in front of DSM-5. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:70. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0445-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Goracci A, di Volo S, Casamassima F, Bolognesi S, Benbow J, Fagiolini A. Pharmacotherapy of binge-eating disorder: a review. J Addict Med. 2015;9:1–19. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Grilo CM, Reas DL, Mitchell JE. Combining pharmacological and psychological treatments for binge eating disorder: current status, limitations, and future directions. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18:55. doi: 10.1007/s11920-016-0696-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kramer CK, Leitão CB, Pinto LC, Canani LH, Azevedo MJ, Gross JL. Efficacy and safety of topiramate on weight loss: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev. 2011;12:e338–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]