Abstract

Background

More than 15 years ago, we started a program of uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopies (VATS) lung metastasectomy in non-intubated local anesthesia. Hereby we present the short and long-term results of this combined surgical-anesthesiological technique.

Methods

Between 2005 and 2015, 71 patients (37 men and 34 women) with pulmonary oligometastases, at the first episode, underwent uniportal VATS metastasectomy under non-intubated anesthesia.

Results

Four patients (5.6%) required intubation for intolerance. Mean number of lesions resected per patient was 1.51. There was no mortality. The study group demonstrated a significant reduction of operative time from the beginning of the experience (P=0.001), good level of consciousness at Richmond scale and quality of recovery after both 24 and 48 hours. Median hospital stay was 3 days and major morbidity rate was 5.5%. Both disease-free survival and overall survival were similar to those achieved with intubated surgery.

Conclusions

VATS lung metastasectomy in non-intubated local anesthesia was safely performed in selected patients with oligometastases with significant advantages in overall operative time, hospital stay and economical costs. Long-term results were similar.

Keywords: Lung metastases, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS), uniportal VATS, non-intubated anesthesia

Introduction

The surgical resection of lung metastases is still considered a reliable therapeutic option in patients with pulmonary oligometastases (1). These lesions are mostly peripherally located and seem to be ideal target for a video-assisted thoracoscopy (VATS) (2,3) despite the impossibility of manual palpation (4,5). More recently, the introduction of new devices and instruments has made possible to accomplish the operation through a unique portal access thus significantly reducing morbidity, postoperative pain and hospital stay (6).

More than 15 years ago we started a program of VATS under thoracic epidural anesthesia in awake patients (7) and this—to our knowledge—is the oldest surgical program specifically created for this purpose. We employed this approach for many pathologies including lung metastasectomy (8). As further evolution with the better knowledge of physiopathology, the introduction of novel drugs and the increased confidence with a “breathing” operative field, we now perform many thoracic procedures including lung metastasectomies using only local anesthesia, in awake and collaborative patients.

The combination uniportal VATS and non-intubated anesthesia couples the advantages of minimal surgical invasiveness with the lesser anesthesiological impact thus achieving better results in both short and long-terms compared to classic techniques. In this study, we described technical aspects and investigated the feasibility, safety, and efficacy of uniportal non-intubated VATS lung metastasectomy.

Methods

Between 2005 and 2015, 71 patients (37 men and 34 women) with lung oligometastases at the first episode successfully underwent uniportal VATS metastasectomy under non-intubated anesthesia. This observational and retrospective study was approved by the ethics committee of our university (No. 016B/17). All patients released their fully-informed written consent once they were informed about the difference with standard surgical approaches, and the possibility of switching to general anesthesia with one-lung ventilation during the procedure.

Indications

Indications for uniportal non-intubated VATS lung metastasectomy must satisfy four levels of requirements. First, all patients must meet the classic prerequisites for lung metastasectomy: complete control of the primary tumor, absence of extrapulmonary metastases, enough residual respiratory capacity and good performance status (9). Second, patients must fit the criteria for VATS operations: anamnestic or imaging absence of pleural adhesion, normal coagulation tests and absence of other bleeding disorders, non-obese patients (mass body index <30 kg/m2). Third, lesions amenable for VATS lung metastasectomy should match the following features: oligometastases with possible long disease-free interval from primary onset, peripheral location easily findable with instrumental or monodigital palpation, small size entailing no more than 3 cm at computed tomography (CT), lesions anyway removable with a wedge resection and imaging absence of enlarged and/or metastatic lymph nodes. Finally, supplementary requisites deal with the feasibility of the operation under non-intubated anesthesia. These rules entail the easy accessibility to the airways, as well as stable and cooperative psychological profile. This status was always preoperatively assessed by a specialist with dedicated tests and with an interview (10,11). At this point, we quite found useful a preconditioning cycle of physiotherapy in order to ameliorate respiratory fatigue and anaerobic threshold.

Lung metastases were always diagnosed with CT imaging during the oncological follow-up. Afterwards, all patients underwent positron emission tomography (PET) to exclude primary recurrence or extrapulmonary relapse. Patients scheduled for operation always underwent spirometry and arterial blood gases for the evaluation of postoperative pulmonary function. Bilateral lesions are always approached in two separated sessions in different days or through a subxiphoid one-stage procedure (n=4).

Anesthesia

Before starting the operation, all patients are warned about the discomfort due to the open pneumothorax, during which they have to maintain a normal breath rate. During the surgical procedure both the surgeon and the anesthesiologist usually talk to the patient to control the level of anesthesia and to update him/her about the progress of the procedure. Low-volume classic music is diffused in the operating room: perception of a calm and professional environment may have a very high impact on patients’ acceptance of the non-intubated procedure.

Anesthesiologist should stay close to the patient having optimal control of the airways. Set for rapid double lumen intubation and bronchoscope should be kept readily available. Adequate patient monitoring is essential for approaching a non-intubated operation: electrocardiogram, pulse oxymeter, systemic and central venous blood pressure, body temperature, arterial line, and end-tidal CO2 by insertion of one detector into a nostril. Objective intraoperative monitoring of the effect of sedative drugs on neurological function was carried out with the bispectral index (12). Timed control of blood gases at the various phases of the operation is mandatory especially in the case of procedures prolonging over 30 minutes.

In order to avoid cough reflex, just before surgery an aerosolized 5 mL solution of 2% lidocaine was administered. Intercostal bloc at the site chosen for uniportal incision was provided by separate local injections of lidocaine 2% (4 mg/kg) and ropivacaine 7.5% (2 mg/kg), the former infiltrating cutis and parietal pleura and the latter mainly delivered around the intercostal nerve of the rib super standing the space chosen for the incision. Operative maneuvers are usually well tolerated with intravenous administration of benzodiazepine (midazolam, 0.03–0.1 mg/kg) and opioids [remifentanil, 15 µg/(kg·min)]. In the case of perioperative onset of anxiety or panic, level of sedation is a little increased by the continuous infusion of propofol (0.5 mg/kg). The patient intraoperatively breathed oxygen through a ventimask in order to keep oxygen saturation greater than 90%.

Surgical technique

Equipment

We usually employ a 10 mm, 30° angled high-definition video-thoracoscope. Dedicated curved instruments with double articulation make the procedure considerably easier. Nevertheless, the basic traditional instruments should be available like curved ring-forceps for lung palpation-manipulation and curved endoscopic vascular clamps for encompassing the lesion and demarking the route for the suture line. Energy delivering systems such as harmonic (Ultracision®) or radiofrequency (Ligasure®) scalpels are useful especially in dividing small pleuro-pulmonary adhesions and controlling moderate parietal and parenchymal hemorrhages. All these actions must be rapid, precise and effective especially in awake patients. Resection is performed with multifire linear articulating stapling device with a tristapling line (2.5–3.5 mm agraphes) for parenchyma with a 45- or 60-mm bites according to the circumstances. Furthermore, chest drainage is kept on the operatory table connected with a water seal system, thus ready to be inserted into the chest whenever the discomfort from a prolonged open pneumothorax increases too much.

Position

The operation is performed with the patient lying in lateral decubitus position with both arms moderately elevated and frontally abducted. Adequate lateral curving of the patient is of a paramount importance in order to avoid the hinder represented by a too protruding hip and shoulder. The surgeon usually stays in front of the patient with the assistant aside him/her whereas scrub nurse is located on the opposite side. Monitor and video equipments are always located at the head of the patient but slightly backward thus avoiding contrast with patient airways and anesthesiologist activity that are of vital importance in non-intubated surgery.

Incision

A single small 30–50 mm uniport skin incision usually sited between fourth and sixth intercostal space depending on the position of the targeted metastasis (Figure 1). The incision is made approximately two fingerbreadths in front of the anterior margin of the latissimus dorsi, thus avoiding the lesion of this muscle. After having coagulated and open the aponeurosis, the serratus anterior is generally bluntly divided along the fibers sense by conventional scissors. Once the chest wall plane is reached, the superior edge of rib limiting the chosen space is coagulated and pleural space entered with the diathermy having care of not damaging the underlying lung. Thoracotomy is usually widened with one finger introduction after having reassured the patient about potential discomfort. Rib spreading retractor is always avoided, whereas only Alexis (Alexis®, Applied Medical, USA) wound protector and muscle retractor is allowed. This unique port must permit the introduction of all required instruments. To avoid crowding and knitting, the thoracoscope is always sited at the posterior end of the port. In the majority of the cases, all these maneuvers are well tolerated in the awake patients and do not require a supplementary infiltration of local anesthetic.

Figure 1.

Non-intubated left lung metastasectomy (13). Available online: http://www.asvide.com/articles/1678

In the case of a subxiphoid incision this is made one fingerbreadth below the costal arc. It has an arciform shape and a long of at least 5 cm, thus allowing the access to both pleural cavities. Rectum abdominis is longitudinally divided along the median line and then the pleural space entered just above the diaphragmatic insertion. The incision is then protected with an Alexis retractor.

Palpation

Initially, pleural cavity is explored and incidental adhesions freed. Then the lesion targeted for resection must be individuated by palpation. This action may often provoke cough with sudden lung movements and complete obliteration of the operative space. In these cases, we found quite useful intraoperative infiltration along the phrenic nerve of 1–2 mL of long action local anesthetic. Even though lesions suitable for non-intubated resection should be peripherally located and thus easily palpable, sometime the research of the lesion may be tedious and this step might become the most time-consuming of the whole procedure. To avoid this inconvenience, several methods have been proposed using intraoperative echographic detection (14,15), dye tracers (16), or wires preoperatively positioned under imaging guide (17). Nevertheless, we still consider enough efficient the combination of digital and instrumental palpation.

At this point, we would suggest some simple guidelines. First, one has always to take into mind the radiological position of the lesion, especially using sagittal and coronal projections. It would be also helpful to calculate the distance between the lesions and the nearest fissure. Due to the persistence of lung ventilation, these relationships do not change very much. Second, a metastatic lesion is rarely visible at the sole optic exploration, thus you need to systematically palpate with the tip of the finger the targeted area. This step is favored by the open pneumothorax, which reduces lung tissue density and facilitates the identification of even smaller nodules. Although consistence and shape of the lesion may largely vary, they remain distinguishable at digital palpation in nearly all cases. Third, instrumental palpation is sometimes necessary because it can reach regions not accessible to finger. It is usually done with a ring-forceps that can appreciate the lesion with both sliding and clamping actions. Unfortunately, instrumental palpation provides less information than the digital one and needs a rigid counterpart like the chest wall to be more effective. In these cases, it would be useful to combine the palpation by approximating the parenchyma to the finger or pushing the lung from the opposite surface either fissure or basal or mediastinal according to the lesion site. Finally, no frustration or insistence if you do not find the expected metastasis, even lesion apparently easy to detect may be missed at first palpation. In these cases, you should not hesitate to enlarge the incision thus allowing the introduction of two or more fingers. Alexis retractor is removed and after supplementary infiltration of lidocaine, the incision extended with accurate hemostasis and a larger Alexis is then positioned. The enlargement of the incision should be preferentially accomplished prolonging the anterior extremity of the wound where the intercostal space is wider. All these maneuvers are well tolerated in a perfectly sedated patient and may significantly contribute to a reduction of the operative time, which is of paramount importance in non-intubated surgery.

Resection

This specific part of the operation requires the most profound anesthesiologic level (with propofol or remifentanyl) in order to avoid improvise and violent reflexes during parenchyma manipulation that may result in pulmonary tears or hemorrhages. After the certain individuation, the lesion is then encompassed with curved endoscopic vascular clamps. This maneuver is helpful for reducing the thickness of the tissue to be included within the stapler bites demarking the route for the suture line. As abovementioned, the resection is performed with multifire linear articulating stapling device for parenchyma with a 45- or 60-mm bites according to the circumstances. At the meantime, lesion is suspended with a ring-forceps thus stimulating the patient’s cough reflex. It is not always easy to insert the stapler in appropriate manner. At this point, we found useful the insertion of a crossed conventional stitch for pulling out the lesion. With this method and especially during the final bites it is possible exteriorizing the lesion thus making further easier the positioning of the stapler (Film). At this point, the removed specimen is examined to ascertain the presence of the lesion, evaluate its nature and control the safety of resection margins.

Closure

Finally, one 28 Ch chest tube is positioned at the posterior end of the surgical incision. No trans-intercostal suture is usually required unless for larger incision or in the case of emphysematous parenchyma potential source of subcutaneous air collection. Muscle sutures are tightened, to obtain maximal lung re-expansion, when asking the patient to breathe deeply or to cough; otherwise, this process can be accelerated with air suction inside the pleural cavity. Conversely to the other surgical step, at this level it is mandatory, for the optimal result of the operation, that the patient must have quite a normal status of consciousness and be almost totally capable of executing verbal orders. The anesthesiologist should be aware of this and regulating the pharmacologic regimen and timing according to this attainment.

Postoperative care

The last phases of the procedure are usually performed with the patient actively collaborating. Soon after the skin closure, the state of consciousness is always measured by the anesthesiologists with the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (18) that differentiates ten levels, from a score of +4 (combative) to −5 (unarousable). One hour after surgery, the patient himself is able to evaluate the postoperative recovery by the Quality of Recovery (QoR-40), which is a 40-item self-administered questionnaire (19). Each item is linked to a 5-point Likert scale [1–5] with a minimum cumulative score of 40 (global maximal impairment) and maximum of 200 (no impairment).

Similarly, intra and postoperative pain was assessed using a visual analogue scale (VAS) that graded from 0 (no pain) to 10 (most severe imaginable pain). Patients were asked to grade perceived pain on a graded ruler (20). After an observation period of 1–2 h in the recovery room, the patient is allowed by the same anesthesiologist to return to the ward. Drinking, eating and walking are restored as soon as possible. Complete lung re-expansion is controlled by chest X-ray. Chest tube is removed in the presence of no more than 100 mL/day and no air leak. In the case of prolonged air leak, discharge is allowed with Heimlich valve.

Results

Patients demographic and clinical data about these patients are summarized in Table 1. Four patients required the conversion to general anesthesia for intolerance to sustain prolonged pneumothorax thus representing a failure rate of 5.6%.

Table 1. Demographic variables and histologic findings of the study population.

| Variables | Value (n=71*) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 66 [46–74] |

| Sex (M:F) | 37:34 |

| Histology (carcinoma:sarcoma) | 53:18 |

| Previous chemotherapy (yes:no) | 41:26 |

| Disease-free interval | |

| <1 year | 25 |

| >3 years | 20 |

| Resected lesions | 101 |

| Number per patient (mean) | 1.51 (101/67) |

| Volume (cm3) | 4.10 [3.90–4.30] |

| Bilateral | 6 |

| Metastases | 81 |

| CT occult metastases | 7 |

| Benign | 20 |

Data are expressed as median and interquartile range within the square brackets. *, 4 excluded because converted. M, man; F, female.

Perioperative and postoperative results are illustrated in Table 2. Our operative times presented a constant reduction with the significant (from 102 to 39 min, P=0.001) progression of the learning curve (Table 2). Similarly, we documented a significant reduction in global in-operating room time, compared to the intubated group (134 vs. 57 min, P=0.003). No patient manifested a clear complain against the non-intubated procedure and many expressed the desire to be operated in future using the same anesthesia.

Table 2. Perioperative and postoperative results of the study population.

| Variables | Value (n=67*) |

|---|---|

| Operative time (min) | 45 [30–57] |

| Operative time for the first 2 years (min) | 102 [45–156] |

| Operative time after 2 years (min) | 39 [30–49] |

| Global in-operating room time (min) | 66 [51–78] |

| Global in-operating room time for the first 2 years (min) | 134 [77–149] |

| Global in-operating room time after 2 years (min) | 57 [41–69] |

| Level of consciouness (RASS) | +3 [1–4] |

| 24-hour postoperative QoR-40 [40–200] | 135 [96–166] |

| 48-hour postoperative QoR-40 [40–200] | 161 [130–194] |

| Drainage removal (hours) | 14 [10–31] |

| Postoperative pain at 1 hour (VAS 1–10) | 5 [2–6] |

| Postoperative pain at 24 hours (VAS 1–10) | 3 [1–4] |

| Hospital stay (days) | 3 [2–4] |

| Major morbidity rate | 5.6% (4/67) |

| 30-day mortality rate | 0 |

| Estimated costs (euro)** | 3,300 [2,600–3,500] |

Data are expressed as median and interquartile range within the square brackets. *, 4 excluded because converted; **, excluding hospital stay. VAS, visual analogue scale; QoR, Quality of Recovery; RASS, Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale.

A total of 101 nodules were palpated and resected (27 patients had resection of more than one nodule), of which 94 of which had been predicted by CT scan. Mean number of lesions resected per patient were 1.51 (Table 1). Eight-one of the resected nodules were defined metastatic at histologic examination. The median volume of the lesions was 4.10 [3.90–4.30] m3 (Table 1). Non-neoplastic nodules were 20 (19.9%): anthracotic lymph node (n=9), granuloma (n=6) and hamartoma (n=5).

There was no mortality. Major morbidity was documented in 4 patients (5.5%), with 2 patients with persistent air leak, 1 pneumonia and 1 persistent arrhythmia. Drainage was removed after a median period of 14 [10–31] hours. Median total length of hospital stay was 3 [2–4] days.

Thirty-nine patients recurred within a median time of 15 months: ipsilateral lung metastases developed in 13 patients and contralateral in 26. Procedures were accomplished again through VATS in the majority of the patients, even on the same side of previous surgery.

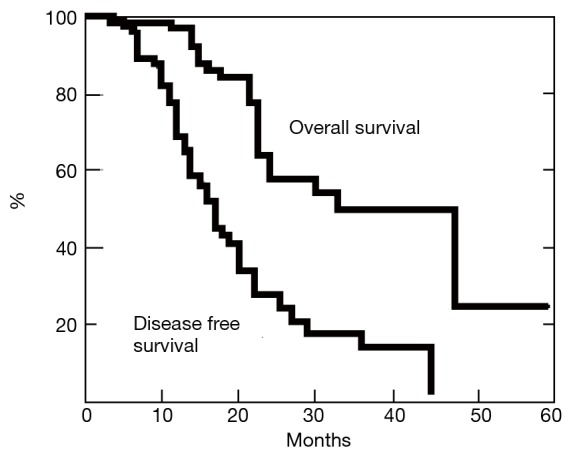

Twenty-nine patients died of recurrence, whereas 38 are still alive, 10 of whom clinically tumor free. Post-operative disease-free survival and overall survival curves rates estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method at 3 years from the operation were 17% and 49%, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Survival analysis for disease-free and overall survival in patients undergoing non-intubated metastasectomy.

Discussion

Lung is the second common site of metastases and metastasectomy is among the most frequent surgical operation involving the lung (1). The role of lung metastasectomy has been widely investigated and the treatment was accomplished in different and progressively safer modality (8,21-24). Thus, the number of pulmonary metastasectomy had significantly increased over the years. Surgery of lung metastases is a topic that has variously stimulated our interest since 1985 when we reported our experience, based on a series collected in our previous institution, about median sternotomy in one-stage resection of bilateral lung metastases (21). Starting from that time we firstly faced the problem of the best way to resect lung investigating time-by-time laser resections (22,23) or the extent of resection in function of the survival (24). The introduction of VATS operation and the obstacle represented by the impossibility of palpating the lesion, thus favoring the probability of imaging-occult persistent metastases, stimulated us to ideate the transxiphoid access. In 1999, we firstly described this approach that allowed the solution of an old problem with apparent paradox conjugating minimal invasiveness with maximal radicality (4). We widely tested this operation appreciating its merits in comparison with available imaging (25), with open access (26) and with long-term survival (27). At the same time, we have also investigated problems related to the biology of lung metastasectomy as regards to the role of inflammation (28), the value of reoperations (29) and their effects on long-term survival (30). Finally, we experienced the advantages of the non-intubated surgery both in terms of anti-infection response (31) and anti-neoplastic effect (32).

More than 15 years ago, the introduction of single-trocar VATS in a second time defined as uniportal VATS (6) has considerably changed and evolved the background. The reduction of the surgical accesses now possible through the development of high definition camera, energy devices, multi-articulated endoscopic stapler, represents an indubitable advantage in patients under non-intubated anesthesia. We have recently published the results of this mixed surgical/anesthesiologic approach demonstrating better early and similar long-term outcomes when compared with traditional intubated multiport-VATS metastasectomy (33).

In the present paper, we provided a detailed description of the surgical steps illustrated some tricks derived from our personal experience, which dates now more than 12 years. This procedure proved safe, as confirmed by the low morbidity rate. The reduction of the surgical and anesthetic trauma has enlarged the number of subjects amenable of lung metastasectomy, thus permitting surgery even in high-risk patients such as elderly and those with poor pulmonary function. This allowed an immediate resumption of many daily activities and a faster recovery and shorter hospitalization. Apart from economical impact of the prolonged hospital stay, the reduced overall time spent in the operating room and the cutback on anesthesiological devices, led to minor costs for the institution.

We anticipated in this paper another new and potentially fruitful frontier represented by the uniportal subxiphoid approach. This route is not new for us because in 1999 we proposed a transxiphoid approach in general anesthesia for lung metastasectomy (4). Our group has employed this approach in non-intubated anesthesiology for one-stage bilateral lung metastasectomy. This approach disclosed unequivocal virtues such as very minimal pain and good cosmesis as well. The development of new dedicated instruments and the increment of surgical skill in subxiphoid uniportal VATS will disclose further intriguing perspectives. Collection of more data and increment of the experience will allow a better evaluation about this forthcoming surgical possibility.

Unquestionably, we have to signal some limitations for uniportal non-intubated VATS lung metastasectomy. First, only a selected number of patients and metastasectomies are amenable of this approach. Thus, in order to reduce conversions rate or long-term failures, we recommend the observance of very strict indications as described in the above dedicated paragraph. Second, we must acknowledge that these operations are not immediately accessible to all surgeons. Before starting a similar program, one must gain an adequate skill in operating through uniportal access regardless of breathing motion. These proficiencies can be gradually acquired after having done a number of non-intubated multiport VATS as well as intubated uniportal VATS operations. Thirdly, less accurate palpation due to the uniportal VATS approach under non-intubated modality is usually considered inadequate with respect to open or hand-assisted approaches (5). However, the refinement of CT scan technology and the accurate selection of the patients with oligometastases might have reduced the risk of undetected lesions, which have been considerably low in our series. As a matter of fact, survival was not affected by the theoretical limitations of the procedure and after a correct patient selection uniportal wedge resection may be considered enough adequate.

We conclude that uniportal VATS lung metastasectomy in non-intubated anesthesia can be easily and safely performed in selected patients with oligometastases without affecting long-term results. The advantages were significant in overall operative time and hospital stay thus resulting in a better patient satisfaction and low economical costs.

Acknowledgements

We are deeply in debt to Dr. Gabriele Mazzitelli for his constant, prompt and competent assistance in editing the paper.

This research was supported by the Italian Health Ministry (title of the project: ‘Profilo genetico associato al fenotipo metastatico e alla prognosi nei tumori polmonari’) issued to Multidisciplinary Lung Metastases Group Tor Vergata University, Rome, Italy.

Ethical Statement: This observational and retrospective study was approved by the ethics committee of our university (No. 016B/17). All patients released their fully-informed written consent once they were informed about the difference with standard surgical approaches, and the possibility of switching to general anesthesia with one-lung ventilation during the procedure.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Treasure T, Milošević M, Fiorentino F, et al. Pulmonary metastasectomy: what is the practice and where is the evidence for effectiveness? Thorax 2014;69:946-9. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-204528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perentes JY, Krueger T, Lovis A, et al. Thoracoscopic resection of pulmonary metastasis: current practice and results. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2015;95:105-13. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdelnour-Berchtold E, Perentes JY, Ris HB, et al. Survival and Local Recurrence After Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Lung Metastasectomy. World J Surg 2016;40:373-9. 10.1007/s00268-015-3254-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mineo TC, Pompeo E, Ambrogi V, et al. Video-assisted approach for transxiphoid bilateral lung metastasectomy. Ann Thorac Surg 1999;67:1808-10. 10.1016/S0003-4975(99)00350-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCormack PM, Bains MS, Begg CB, et al. Role of video-assisted thoracic surgery in the treatment of pulmonary metastases: results of a prospective trial. Ann Thorac Surg 1996;62:213-6; discussion 216-7. 10.1016/0003-4975(96)00253-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Migliore M, Deodato G. A single-trocar technique for minimally-invasive surgery of the chest. Surg Endosc 2001;15:899-901. 10.1007/s004640090033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mineo TC. Epidural anesthesia in awake thoracic surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2007;32:13-9. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mineo TC, Ambrogi V. Lung metastasectomy: an experience-based therapeutic option. Ann Transl Med 2015;3:194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ehrenhaft JL, Lawrence MS, Sensenig DM. Pulmonary resections for metastatic lesions. AMA Arch Surg 1958;77:606-12. 10.1001/archsurg.1958.04370010138013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McNair DM, Lorr M, Droppleman LF. Manual for the Profile of Mood States. San Diego, CA: Educational and Industrial Testing Services, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marks IM, Mathews AM. Brief standard self-rating for phobic patients. Behav Res Ther 1979;17:263-7. 10.1016/0005-7967(79)90041-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kissin I. Depth of anesthesia and bispectral index monitoring. Anesth Analg 2000;90:1114-7. 10.1097/00000539-200005000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mineo TC, Sellitri F, Fabbi E, et al. Non-intubated left lung metastasectomy. Asvide 2017;4:364. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/articles/1678

- 14.Matsumoto S, Hirata T, Ogawa E, et al. Ultrasonographic evaluation of small nodules in the peripheral lung during video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS). Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2004;26:469-73. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin MW, Chen JS. Image-guided techniques for localizing pulmonary nodules in thoracoscopic surgery. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:S749-S755. 10.21037/jtd.2016.09.71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang SM, Ko WC, Lin MW, et al. Image-guided thoracoscopic surgery with dye localization in a hybrid operating room. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:S681-9. 10.21037/jtd.2016.09.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eichfeld U, Dietrich A, Ott R, et al. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for pulmonary nodules after computed tomography-guided marking with a spiral wire. Ann Thorac Surg 2005;79:313-6; discussion 316-7. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.10.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sessler CN, Gosnell MS, Grap MJ, et al. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:1338-44. 10.1164/rccm.2107138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Myles PS, Weitkamp B, Jones K, et al. Validity and reliability of a postoperative quality of recovery score: the QoR-40. Br J Anaesth 2000;84:11-5. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bja.a013366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Price DD, McGrath PA, Rafii A, et al. The validation of visual analogue scales as ratio scale measures for chronic and experimental pain. Pain 1983;17:45-56. 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90126-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rendina EA, Mineo TC, Facciolo F, et al. Median sternotomy for resection of lung metastases. Ital J Surg Sci 1985;15:375-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mineo TC, Cristino B, Ambrogi V, et al. Usefulness of the Nd:YAG laser in parenchyma-sparing resection of pulmonary nodular lesions. Tumori 1994;80:365-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mineo TC, Ambrogi V, Pompeo E, et al. The value of the Nd:YAG laser for the surgery of lung metastases in a randomized trial. Chest 1998;113:1402-7. 10.1378/chest.113.5.1402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mineo TC, Ambrogi V, Tonini G, et al. Pulmonary metastasectomy: might the type of resection affect survival? J Surg Oncol 2001;76:47-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ambrogi V, Paci M, Pompeo E, et al. Transxiphoid video-assisted pulmonary metastasectomy: relevance of helical computed tomography occult lesions. Ann Thorac Surg 2000;70:1847-52. 10.1016/S0003-4975(00)01806-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mineo TC, Ambrogi V, Paci M, et al. Transxiphoid bilateral palpation in video-assisted thoracoscopic lung metastasectomy. Arch Surg 2001;136:783-8. 10.1001/archsurg.136.7.783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mineo TC, Ambrogi V, Mineo D, et al. Transxiphoid hand-assisted videothoracoscopic surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2007;83:1978-84. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mineo TC, Tacconi F. Role of systemic inflammation scores in pulmonary metastasectomy for colorectal cancer. Thorac Cancer 2014;5:431-7. 10.1111/1759-7714.12114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mineo TC, Ambrogi V, Tacconi F, et al. Multi-reoperations for lung metastases. Future Oncol 2015;11:37-41. 10.2217/fon.14.282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Treasure T, Mineo T, Ambrogi V, et al. Survival is higher after repeat lung metastasectomy than after a first metastasectomy: Too good to be true? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2015;149:1249-52. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.01.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vanni G, Tacconi F, Sellitri F, et al. Impact of awake videothoracoscopic surgery on postoperative lymphocyte responses. Ann Thorac Surg 2010;90:973-8. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.04.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mineo TC, Ambrogi V. Efficacy of awake thoracic surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;143:249-50; author reply 250-1. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.08.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ambrogi V, Sellitri F, Perroni G, et al. Uniportal video-assisted thoracic surgery colorectal lung metastasectomy in non-intubated anesthesia. J Thorac Dis 2017;9:254-61. 10.21037/jtd.2017.02.40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]