Abstract

Objective To compare initial brain computed tomography (CT) scans with follow-up CT scans at one year in children with congenital Zika syndrome, focusing on cerebral calcifications.

Design Case series study.

Setting Barão de Lucena Hospital, Pernambuco state, Brazil.

Participants 37 children with probable or confirmed congenital Zika syndrome during the microcephaly outbreak in 2015 who underwent brain CT shortly after birth and at one year follow-up.

Main outcome measure Differences in cerebral calcification patterns between initial and follow-up scans.

Results 37 children were evaluated. All presented cerebral calcifications on the initial scan, predominantly at cortical-white matter junction. At follow-up the calcifications had diminished in number, size, or density, or a combination in 34 of the children (92%, 95% confidence interval 79% to 97%), were no longer visible in one child, and remained unchanged in two children. No child showed an increase in calcifications. The calcifications at the cortical-white matter junction which were no longer visible at follow-up occurred predominately in the parietal and occipital lobes. These imaging changes were not associated with any clear clinical improvements.

Conclusion The detection of cerebral calcifications should not be considered a major criterion for late diagnosis of congenital Zika syndrome, nor should the absence of calcifications be used to exclude the diagnosis.

Introduction

In 2015 an unprecedented outbreak of congenital microcephaly associated with the Zika virus occurred in Brazil. Since then appreciable knowledge has been gained about the epidemiology and physiopathology of the disease.1 2 3 4 The global risk assessment has not changed. Zika virus continues to spread geographically to areas where effective vectors are present. The number of cases of Zika virus infection reported in some countries has declined, but vigilance needs to remain high.5 Healthcare professionals are now faced with a population of children with congenital Zika virus syndrome and a broad spectrum of clinical and radiological presentations with an as yet unknown clinical course.6 7

The main findings on brain computed tomography (CT) scans of newborns with congenital Zika syndrome have been widely reported. These include brain calcifications (mainly at the cortical-white matter junction), decreased brain volume with malformation of cortical development, ventriculomegaly (mostly colpocephaly, defined as disproportionate enlargement of the occipital horns of the lateral ventricles), hypoplasia of the cerebellum, and prominent protuberance of the occipital bone.8 9 10

Several of the children with congenital Zika syndrome we have followed up have developed hydrocephalus, sometimes in the absence of specific symptoms, and some have required ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement. The pathophysiology of hydrocephalus in congenital Zika syndrome is still unknown. Because of the risk of hydrocephalus, many of the children underwent follow-up CT; the recent recommendation is for children with congenital Zika syndrome aged 10-12 months to have at least one brain image.11 As there are currently no published follow-up studies describing the evolution of the neuroimaging abnormalities in such infants, we compared the initial brain scans with follow-up scans of the first 37 children with congenital Zika syndrome referred for CT. Our focus was on cerebral calcifications.

Methods

We carried out a case series study using convenience sampling in 37 children with probable or confirmed congenital Zika syndrome, as defined by the Brazilian Ministry of Health.12 All the children underwent follow-up unenhanced head computed tomography (CT) in Recife, between August 2015 and January 2017.

Re-evaluation of children was indicated when there was clinical suspicion of hydrocephalus owing to non-specific symptoms. The most common signs and symptoms necessitating follow-up CT were: seizures (70%, n=26), intractable seizures (30%, n=11), irritability (27%, n=10), vomiting (22%, n=8), worsening of dysphagia (14%, n=5), previous magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan suggestive of hydrocephalus (11%, n=4), an increase in head circumference (8%, n=3), drowsiness (5%, n=2), worsening of hypertonia (3%, n=1), or recurrent respiratory tract infection (3%, n=1). These symptoms could occur simultaneously. The most common symptoms, present in nine of the children (24%), were vomiting, irritability, and intractable seizures. Despite the harmful effects of ionising radiation, CT was the imaging of choice in the children at 1 year of age because closure of the cranial fontanelles procludes the use of transfontanelle ultrasonography. MRI was not practical in our setting owing to longer procedure time, need for prolonged sedation, and higher cost.

At the start of the Zika virus outbreak, the Brazilian Ministry of Health defined microcephaly as a head circumference of 33 cm or less. The Intergrowth-21st Project of the World Health Organization now defines microcephaly as a head circumference of less than 2 standard deviations from the mean for gestational age and sex and severe microcephaly as a head circumference of less than 3 standard deviations from the mean for gestational age and sex.13

An assistant neuropaediatrician formally requested all follow-up unenhanced CT scans. Most of the children did not require sedation. For the few children who were agitated during the procedure, an experienced anaesthetist administered inhalation sedation according to the child’s weight.

Several inclusion criteria were used for selection of participants: initial CT performed shortly after birth, according to the protocol established to investigate microcephaly during the Brazilian outbreak12; initial scan showed findings suggestive of congenital infection (including cerebral calcifications, ventriculomegaly, malformation of cortical development, hypoplasia of the cerebellum or brainstem, and abnormalities of white matter); and laboratory findings excluded STORCH (syphilis, toxoplasmosis, rubella, cytomegalovirus, and herpesvirus) infections in the mother or baby, or both.

According to the Brazilian Ministry of Health, in probable cases of congenital Zika syndrome the mothers had reported a rash during pregnancy, the neonates had brain imaging suggestive of congenital infection, and the laboratory findings excluded STORCH infections in the mother or baby, or both. Confirmed cases additionally had laboratory confirmation of Zika virus infection in the mother or baby, or both (eg, real time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, Zika virus specific IgM, plaque reduction neutralisation test for the virus in cerebrospinal fluid or serum, or both).12

During the Zika virus related outbreak of microcephaly initial CT was performed in various radiology centres using different equipment (multislice CT varying from 6 to 64 detectors), making it impossible to standardise imaging, but these scanners had similar technical capabilities. A Philips Brilliance six slice scanner was used for all imaging performed at Barão de Lucena Hospital. We used a non-enhanced low dose protocol specific for children, as it involves less ionising radiation than standard imaging. The children were placed in a supine position head first into the gantry, with the head supported by a holder. Table height was defined when the external auditory meatus was at the centre of the gantry. The gantry was not angled. The images were acquired from foramen magnum to the top of calvarium with 300 mAs, 90 kVp, and 3 mm of thickness.

All CT scans were saved as DICOM images on a CD. Trained radiologists analysed and compared the images in a workstation. The initial and follow-up images from each child were analysed side by side after adjustments for CT window, slice thickness, and planes. Despite variations in the images, these were minimal and did not compromise the evaluation of calcifications.

Four experienced clinicians (one neuropaediatrician and three radiologists) analysed the images together in two meetings. At the first meeting images from 20 children were analysed and at the second meetings images from 17 children were analysed. The initial evaluation was to determine the presence of brain calcifications (yes or no); if calcifications were present, they were classified according to shape (punctate, coarse, or both) and location (cerebellum, brainstem, thalamus, basal ganglia, periventricular area, cerebral cortex, or at the cortical-white matter junction). We also evaluated the location of calcifications at the cortico-white matter junction in the frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes. For the follow-up scans we determined if the calcifications had increased, remained unchanged, diminished (decreased in number, size, or density, or a combination), or were no longer visible; in the last instance we registered the previous location that the calcification was visible (cerebellum, brainstem, thalamus, basal ganglia, periventricular, cerebral cortex, or at the cortical-white matter junction ); and the cerebral lobe in which it had occurred (frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital).

Agreement among the reviewers was good. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. The results were recorded on spreadsheets for statistical analysis. Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS version 21.0. We used the McNemar test to compare the findings between the two sets of scans. Fisher’s exact test was used to analyse the association between variables. Additional analyses included a residual analysis, which examines the association between categories of variables in a contingency table. We considered P values less than 0.05 to be significant.

Patient involvement

No patients were involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures, nor were they involved in developing plans for recruitment, design, or implementation of the study. No patients were asked to advise on interpretation or writing up of results. There are no plans to disseminate the results of the research to study participants or the relevant patient community.

Results

Thirty seven children with congenital Zika syndrome were evaluated by CT. Twenty two (59%) were boys. Information on maternal infection was available for 36 of the children. Twenty five mothers (69%) reported a rash between two and six months of gestation, with 18 (50%) experiencing a rash in the first trimester. The gestational age at birth ranged from 31 to 41 weeks (five babies were preterm). Head circumference measurements at birth ranged from 23 cm to 33 cm. Thirty five of the children (95%) had microcephaly, with 26 (70%) of these children classified as having severe microcephaly. Two children (5%) had a normal head circumference at birth but developed postnatal microcephaly. Congenital Zika virus syndrome was confirmed in 29 of the 37 children, the remainder (n=8, 22%) being probable cases. Although the probable cases were typical of congenital Zika syndrome, we were not able to confirm the diagnosis because of delays in submitting serum samples for laboratory testing). Fifteen of the children (41%, 95% confidence interval 26% to 57%) had a diagnosis of hydrocephalus on follow-up CT and indications for ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement.

The children’s age ranged from 1 to 138 days (median 11.5 days) at the time of the initial CT scan and 105 to 509 days (median 415 days) at the follow-up scan.

Twenty eight of the 37 children had follow-up CT at the same hospital and with the same image acquisition parameters for all children. Nine children were scanned on the same equipment for both scans.

Results of initial CT

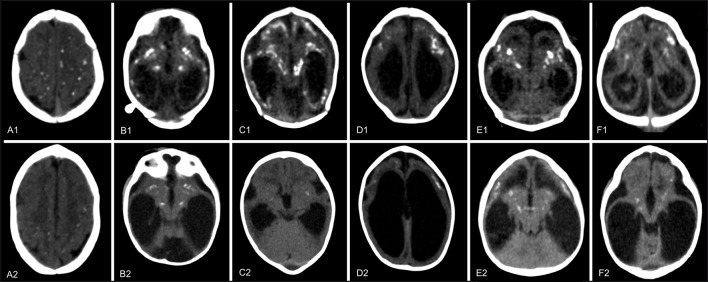

All 37 children had brain calcifications, and each showed punctate calcifications on the initial CT. Nineteen (51%, 95% confidence interval 36% to 67%) also presented coarse calcifications (fig 1).

Fig 1 Initial CT scans of children with congenital Zika syndrome showing (A) punctuate and (B) coarse and punctate patterns of calcifications

The most common location of calcifications was at the cortical-white matter junction (95%, 82% to 98%) followed by basal ganglia (70%, 54% to 82%), thalamus (54%, 38% to 69%), brainstem (14%, 6% to 28%), periventricular area (11%, 4% to 25%), and cerebellum (8%, 3% to 21%). Distribution of cortical-white matter junction calcifications in cerebral lobes predominated in frontal lobes, followed by parietal, temporal and occipital.

Results of follow-up CT

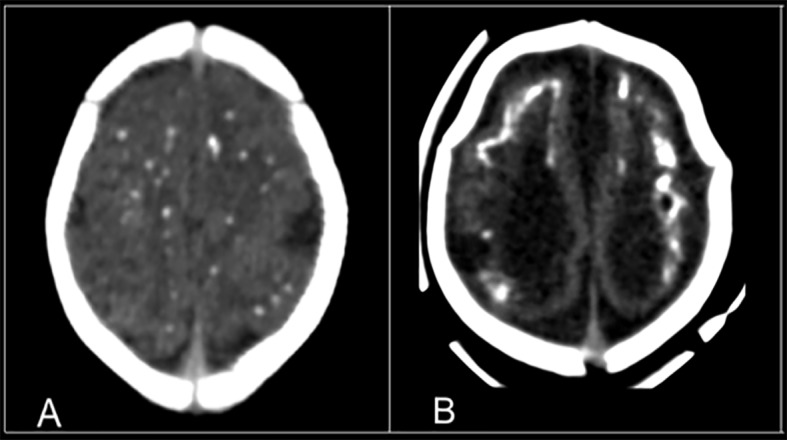

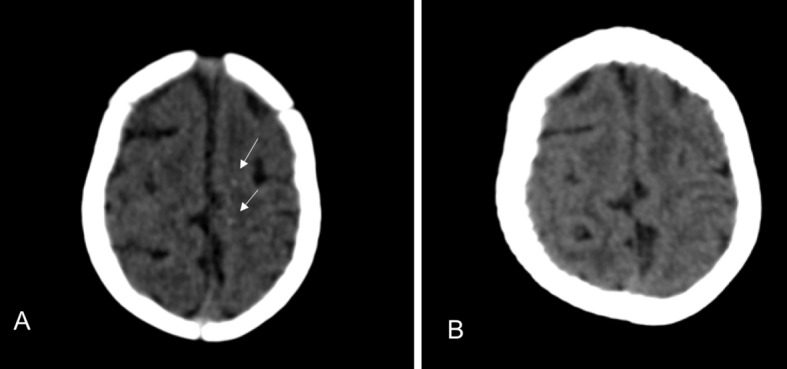

By follow-up the calcifications had diminished in number, size, or density or a combination in 34 children (92%, 95% confidence interval 79% to 97%); (fig 2), were no longer present in one child (fig 3), and remained unchanged in two children (fig 4). No child had an increase in number, size, or density of calcifications.

Fig 2 Representative CT scans from six children (A-F) with congenital Zika syndrome and diminished number, size, or density of calcifications at one year follow-up (A2-F2) compared with initial scans after birth (A1-F1). Punctate calcifications at the cortical-white matter junction white matter in frontal and parietal lobes in child A had diminished at follow-up. Punctate calcifications at the cortical-white matter junction, predominating in temporal lobes, and coarse calcifications in basal ganglia and thalamus in child B had diminished at follow-up. Punctate and coarse calcifications at the cortical-white matter junction in frontal and parietal lobes, basal ganglia, and thalamus in child C had mostly diminished at follow-up, with only a few remaining and tenuous punctate calcifications present in basal ganglia and thalamus. Punctate and coarse calcifications at the cortical-white matter junction in frontal lobes in child D had diminished at follow-up. Punctate and coarse calcifications at the cortical-white matter junction in frontal and temporal lobes, basal ganglia, and thalamus in child E had diminished at follow-up. Punctate and coarse calcifications at the cortical-white matter junction in frontal and temporal lobes, basal ganglia, and thalamus in child F had diminished at follow-up

Fig 3 CT scans of only child with congenital Zika syndrome whose cerebral calcifications were no longer visible. Initial scan (A) shows tenuous punctate calcifications at the cortical-white matter junction in frontal lobes (arrows). (B) Calcifications are no longer visible at one year follow-up

Fig 4 CT scans of child with congenital Zika syndrome. Initial scan (A) shows punctate calcifications at the cortical-white matter junction in the occipital lobe (arrow). (B) Calcifications remained unchanged at one year follow-up

Calcifications were no longer visible at the cortical-white matter junction of all lobes of the cerebral hemispheres (n=1, P=1.00), thalamus (n=2, P=0.50), brainstem (n=2, P=0.50), and periventricular area (n=3, P=0.25). Calcifications in the basal ganglia and cerebellum remained unchanged (P=1.00).

Calcifications at the cortical-white matter junction in 35 of the children had diminished in 32 (91%), were no longer visible in one (3%), and remained unchanged in two (6%). The disappearance of calcifications at the cortical-white matter junction was statistically significant only in the parietal (P=0.004) and occipital lobes (P=0.004) (table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of cortical-white matter junction calcifications in cerebral lobes on initial computed tomography and one year follow-up (n=35). Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Presence of calcifications by lobe in initial CT | Follow-up CT | P value (McNemar test) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| Frontal: | |||

| Yes | 32 (94) | 2 (6) | 0.99 |

| No | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| Parietal: | |||

| Yes | 19 (68) | 9 (32) | 0.004* |

| No | 0 (0) | 7 (100) | |

| Temporal: | |||

| Yes | 20 (95) | 1 (5) | 0.99 |

| No | 1 (7) | 13 (93) | |

| Occipital: | |||

| Yes | 12 (57) | 9 (43) | 0.004* |

| No | 0 (0) | 14 (100) | |

*P<0.05.

Discussion

All 37 children with probable or confirmed congenital Zika syndrome during the 2015 outbreak of Zika virus related microcephaly in Brazil had calcifications on initial brain CT; calcification represents the most obvious imaging finding in children with congenital Zika syndrome. The most common location for calcifications was at the cortical-white matter junction, followed by the basal ganglia, thalamus, brainstem, and cerebellum. These results agree with the existing literature.8 9 10

At one year follow-up the calcifications had diminished in number, size, or density, or a combination, or were no longer visible in most children. They remained unchanged in only two children (5%). No child had an increase in calcifications. The only child in whom the calcifications disappeared had minimal findings on initial CT, with just a few punctate calcifications at the cortical-white matter junction in the frontal lobe.

The diminution in calcifications did not necessarily correlate with clinical improvement. Most of the patients presented with severe neurological impairment, such as epilepsy and feeding problems. It would be helpful to compare our findings with follow-up scans of children who showed clinical improvement, or remained stable, to investigate if calcifications had also diminished.

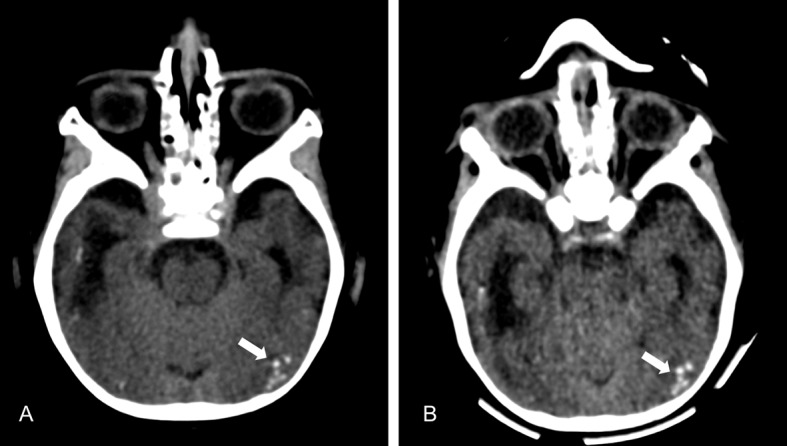

The comprehensive autopsy reports of microcephalic fetuses affected by the Zika virus from Slovenia and the US2 14 describe disorders of neuronal differentiation, astroglia reactivity, and microcalcifications of the parenchyma. The authors did not mention any considerable inflammatory reactions in the central nervous system. The microcalcifications found in these cases were related to cell remnants.

In vitro experimental evidence, using human neuroprogenitor cells,15 16 and in vivo evidence in mouse 17 and primate models,18 19 strongly suggests that the main mechanism in the loss of neural cells in congenital Zika syndrome is the pathologically induced apoptosis of neuroprogenitor cells.20 Early clinical observations correlated with gestational and postnatal brain images and cerebrospinal fluid analysis pointed towards a primary teratogenic mechanism unrelated to necrotic or inflammatory lesions in the central nervous system.21 The lack of inflammation at autopsy, combined with clinical data, suggests that brain malformation may be the result of pathologically induced apoptotic process followed by microglial reaction, and not an exudative mechanism involving recruitment of peripheral inflammatory cells after breakdown of the blood-brain barrier.22 Additional research on this microglial phagocytic response seems warranted.23

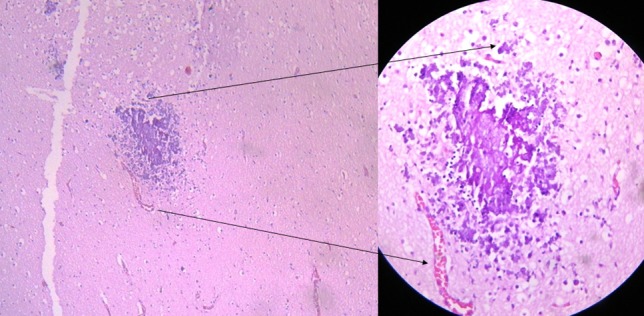

The process of calcium deposition in apoptotic organic matrix is described in the literature.24 25 The punctate calcifications we identified on CT scans might correspond to these microscopy, loose calcium deposits, and the coarse calcifications to larger calcium aggregates (fig 5).26

Fig 5 Brain section of fetus with Zika virus related microcephaly: parenchymal (white matter) microcalcifications on a non-inflammatory background (haematoxylin and eosin×50). (Inset) Arrow shows non-inflamed blood vessel adjacent to microcalcifications (haematoxylin and eosin×100)

It thus seems possible that the progressive clearance of intraparenchymal calcifications could reflect enhanced microglial activity with disaggregation of mineralised microgranules by active phagocytosis and removal through the lymphatic system of the central nervous system.27 28

The distribution of calcifications at the cortical-white matter junction showed a statistically significant diminution of calcification in the parietal (P=0.004) and occipital lobes (P=0.004).

In this study, 40.5% of the children went on to develop hydrocephalus and required ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement. The pathophysiology of hydrocephalus in congenital Zika syndrome is still unknown. Aragao et al7 29 and Soares de Oliveira-Szejnfeld10 have hypothesised that damage to the cerebral vascular system, especially in the venous component, leads to cerebral venous thrombosis and cerebral venous hypertension during intrauterine development, which continues after birth. Chronic venous hypertension could explain the calcifications and progression to hydrocephalus. Future studies with brain MRI and brain magnetic resonance venography (unenhanced) may uncover additional information about the association between thrombosis and congenital Zika syndrome.

Our finding - that brain calcifications in this population of children with confirmed or probable congenital Zika syndrome diminished over time - suggests that the presence of cerebral calcifications should no longer be considered a major criterion for late diagnosis of congenital Zika syndrome. Our findings could, in part, explain the difficulty in diagnosing congenital Zika syndrome in children without microcephaly at initial presentation.6 29

One limitation of our study was our subjective quantification of cerebral calcifications, as we are unaware of any specific software for measurements. However, we tried to minimise the effects of subjective bias by reading the images jointly in a consensus analysis.

Unanswered questions and future research

We have described imaging findings at one year follow-up in a series of infants with congenital Zika syndrome. The clinical course of this syndrome is still to be described. We believe that this study, along with new knowledge about the physiopathology of congenital Zika syndrome and additional radiological data, can contribute to the understanding of this disease.

Conclusion

In this series of children with confirmed or probable congenital Zika syndrome, brain calcifications had diminished in number, size, or density, or a combination at one year follow-up. No child had an increase in number of calcifications. The calcifications at the cortical-white matter junction which were no longer visible at follow-up occurred predominately in the parietal and occipital lobes. In view of the present data, cerebral calcification should not be considered a major criterion for late diagnosis of congenital Zika syndrome, nor should its absence be used to exclude the diagnosis.

What is already known on this topic

Cerebral calcifications at the cortical-white matter junction are the most obvious imaging sign of congenital Zika syndrome

No follow-up studies have been done on calcifications in children with congenital Zika syndrome

What this study adds

Calcifications found on CT scans shortly after birth in children with probable or confirmed congenital Zika syndrome had partially or completely diminished at one year follow-up, although this did not correlate with clinical improvement

Calcification should not be considered a major criterion for late diagnosis of congenital Zika syndrome, nor should its absence be used to exclude the diagnosis

We thank Carla Araújo, director of Barão de Lucena Hospital, and Samara Brelaz for their assistance.

Contributors: All authors contributed to the clinical (VvdL, MdCMBD), radiological (NCdLP, MdFVA, LA, MA, AF, AB-L, PP), and pathological assessment (PJ, RM), according to their own specialty, and to the concept and design (NCdLP, MdFVA, PP) or analysis and interpretation of the data (NCdLP, CS) and to the draft of the final version (NCdLP, MdFVA, AH, MdCMBD). NCdLP is the guarantor.

Funding: No external funding provided.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the research ethics committee from Otávio de Freitas Hospital (Pernambuco State Secretary of Health and the children’s carers gave consent for the publication of the results and images.

Data sharing: Initial and follow-up CT images, clinical data and statistical calculations are available from the corresponding author at natachacalheiros@yahoo.com.br.

Transparency: The lead author (NCdLP) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

References

- 1.Oliveira Melo AS, Malinger G, Ximenes R, Szejnfeld PO, Alves Sampaio S, Bispo de Filippis AM. Zika virus intrauterine infection causes fetal brain abnormality and microcephaly: tip of the iceberg?Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2016;47:6-7. 10.1002/uog.15831 pmid:26731034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mlakar J, Korva M, Tul N, et al. Zika virus associated with microcephaly. Brief report. N Engl J Med 2016;374:951-8.[REMOVED IF= FIELD] 10.1056/NEJMoa1600651 pmid:26862926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martines RB, Bhatnagar J, Keating MK, et al. Notes from the Field: Evidence of Zika Virus Infection in Brain and Placental Tissues from Two Congenitally Infected Newborns and Two Fetal Losses--Brazil, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:159-60. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6506e1 pmid:26890059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calvet G, Aguiar RS, Melo ASO, et al. Detection and sequencing of Zika virus from amniotic fluid of fetuses with microcephaly in Brazil: a case study. Lancet Infect Dis 2016;16:653-60. 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00095-5 pmid:26897108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO. Situation report. Zika virus. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/254507/1/zikasitrep2Feb17-eng.pdf.

- 6.van der Linden V, Pessoa A, Dobyns W, et al. Description of 13 Infants Born During October 2015-January 2016 With Congenital Zika Virus Infection Without Microcephaly at Birth. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:1343-8. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6547e2 pmid:27906905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aragao MFVV, Holanda AC, Brainer-Lima AM, et al. Nonmicrocephalic Infants with Congenital Zika Syndrome Suspected Only after Neuroimaging Evaluation Compared with Those with Microcephaly at Birth and Postnatally: How Large Is the Zika Virus “Iceberg”?AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2017;38:1427-34. 10.3174/ajnr.A5216 pmid:28522665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hazin AN, Poretti A, Di Cavalcanti Souza Cruz D, et al. Microcephaly Epidemic Research Group. Computed Tomographic Findings in Microcephaly Associated with Zika Virus. N Engl J Med 2016;374:2193-5. 10.1056/NEJMc1603617 pmid:27050112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aragao MFV, van der Linden V, Brainer-Lima AM, et al. Clinical features and neuroimaging (CT and MRI) findings in presumed Zika virus related congenital infection and microcephaly: retrospective case series study. BMJ 2016;353:i1901 10.1136/bmj.i1901 pmid:27075009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soares de Oliveira-Szejnfeld P, Levine D, Melo AS de O, et al. Congenital Brain Abnormalities and Zika Virus: What the Radiologist Can Expect to See Prenatally and Postnatally. Radiology 2016;281:203-18. 10.1148/radiol.2016161584 pmid:27552432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Linden V, Filho ELR, van der Linden A. Congenital Zika Syndrome: Clinical Aspects. In: Maria de Fátima VVA, ed. Zika Focus, First.Springer International Publishing, 2017: 33-45. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Microcefalia D. Ou E/ (2016) PROTOCOLO DE VIGILÂNCIA E RESPOSTA À OCORRÊNCIA. http://combateaedes.saude.gov.br/images/sala-de-si

- 13.Villar J, Cheikh Ismail L, Victora CG, et al. International Fetal and Newborn Growth Consortium for the 21st Century (INTERGROWTH-21st). International standards for newborn weight, length, and head circumference by gestational age and sex: the Newborn Cross-Sectional Study of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. Lancet 2014;384:857-68. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60932-6 pmid:25209487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Driggers RW, Ho C-Y, Korhonen EM, et al. Zika Virus Infection with Prolonged Maternal Viremia and Fetal Brain Abnormalities. N Engl J Med 2016;374:2142-51. 10.1056/NEJMoa1601824 pmid:27028667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang H, Hammack C, Ogden SC, et al. Zika Virus Infects Human Cortical Neural Progenitors and Attenuates Their Growth. Cell Stem Cell 2016;18:587-90. 10.1016/j.stem.2016.02.016 pmid:26952870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcez PP, Loiola EC, Madeiro da Costa R, et al. Zika virus impairs growth in human neurospheres and brain organoids. Science 2016;352:816-8. 10.1126/science.aaf6116. pmid:27064148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cugola FR, Fernandes IR, Russo FB, et al. The Brazilian Zika virus strain causes birth defects in experimental models. Nature 2016;534:267-71. 10.1038/nature18296. pmid:27279226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adams Waldorf KM, Stencel-Baerenwald JE, Kapur RP, et al. Fetal brain lesions after subcutaneous inoculation of Zika virus in a pregnant nonhuman primate. Nat Med 2016;22:1256-9. 10.1038/nm.4193 pmid:27618651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dudley DM, Aliota MT, Mohr EL, et al. A rhesus macaque model of Asian-lineage Zika virus infection. Nat Commun 2016;7:12204 10.1038/ncomms12204 pmid:27352279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Russo FB, Jungmann P, Beltrão-Braga PCB. Zika infection and the development of neurological defects. Cell Microbiol 2017;19:12744 10.1111/cmi.12744 pmid:28370966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jungmann P, Pires P, Araujo Júnior E. Early insights into Zika’s microcephaly physiopathology from the epicenter of the outbreak: teratogenic apoptosis in the central nervous system. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2017;96:1039-44. 10.1111/aogs.13184 pmid:28646619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nickerson JP, Richner B, Santy K, et al. Neuroimaging of pediatric intracranial infection--part 2: TORCH, viral, fungal, and parasitic infections. J Neuroimaging 2012;22:e52-63. 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2011.00699.x pmid:22309611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marín-Teva JL, Cuadros MA, Martín-Oliva D, Navascués J. Microglia and neuronal cell death. Neuron Glia Biol 2011;7:25-40. 10.1017/S1740925X12000014 pmid:22377033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim KM. Apoptosis and calcification. Scanning Microsc 1995;9:1137-75, discussion 1175-8.pmid:8819895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujita H, Yamamoto M, Ogino T, et al. Necrotic and apoptotic cells serve as nuclei for calcification on osteoblastic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells in vitro Cell Biochem Funct 2014;32:77-86. 10.1002/cbf.2974 pmid:23657822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holanda ACMR. Histopathological Findings of Congenital Zika Syndrome. In: Aragao MFVV, ed. Zika Focus., First.Springer, 2017: 139-50. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Louveau A, Smirnov I, Keyes TJ, et al. Structural and functional features of central nervous system lymphatic vessels. Nature 2015;523:337-41. 10.1038/nature14432 pmid:26030524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iliff JJ, Wang M, Liao Y, et al. A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid β. Sci Transl Med 2012;4:147ra111 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003748 pmid:22896675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aragao MFVV, Brainer-Lima AM, Holanda AC de LPN. Neuroimaging Findings of Congenital Zika Syndrome. In: Aragao MFVV, ed. Zika Focus. Springer, 2017: 63- 92. [Google Scholar]