SUMMARY

We build on and extend the findings in Case and Deaton (2015) on increases in mortality and morbidity among white non-Hispanic Americans in midlife since the turn of the century. Increases in all-cause mortality continued unabated to 2015, with additional increases in drug overdoses, suicides, and alcohol-related liver mortality, particularly among those with a high-school degree or less. The decline in mortality from heart disease has slowed and, most recently, stopped, and this combined with the three other causes is responsible for the increase in all-cause mortality. Not only are educational differences in mortality among whites increasing, but from 1998 to 2015 mortality rose for those without, and fell for those with, a college degree. This is true for non-Hispanic white men and women in all five year age groups from 35–39 through 55–59. Mortality rates among blacks and Hispanics continued to fall; in 1999, the mortality rate of white non-Hispanics aged 50–54 with only a high-school degree was 30 percent lower than the mortality rate of blacks in the same age group but irrespective of education; by 2015, it was 30 percent higher. There are similar crossovers in all age groups from 25–29 to 60–64.

Mortality rates in comparable rich countries have continued their pre-millennial fall at the rates that used to characterize the US. In contrast to the US, mortality rates in Europe are falling for those with low levels of educational attainment, and have fallen further over this period than mortality rates for those with higher levels of education.

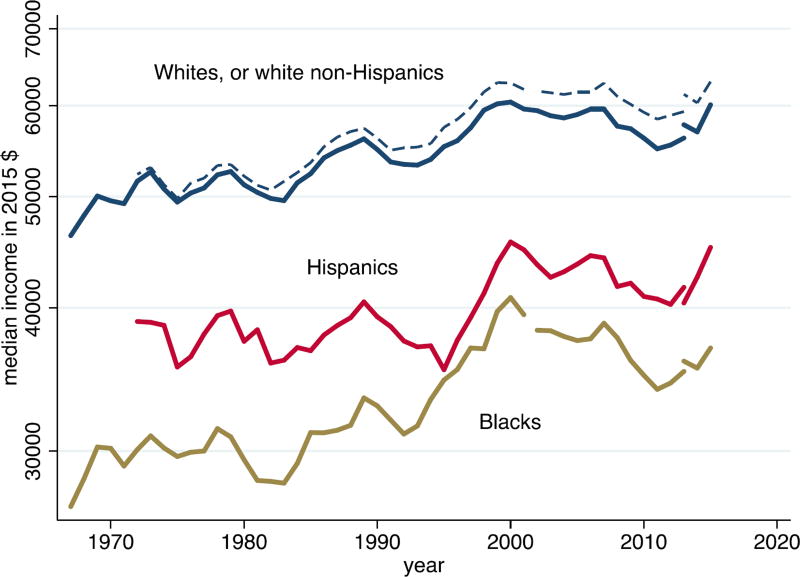

Many commentators have suggested that poor mortality outcomes can be attributed to contemporaneous levels of resources, particularly to slowly growing, stagnant, and even declining incomes; we evaluate this possibility, but find that it cannot provide a comprehensive explanation. In particular, the income profiles for blacks and Hispanics, whose mortality rates have fallen, are no better than those for whites. Nor is there any evidence in the European data that mortality trends match income trends, in spite of sharply different patterns of median income across countries after the Great Recession.

We propose a preliminary but plausible story in which cumulative disadvantage from one birth cohort to the next, in the labor market, in marriage and child outcomes, and in health, is triggered by progressively worsening labor market opportunities at the time of entry for whites with low levels of education. This account, which fits much of the data, has the profoundly negative implication that policies, even ones that successfully improve earnings and jobs, or redistribute income, will take many years to reverse the mortality and morbidity increase, and that those in midlife now are likely to do much worse in old age than those currently older than 65. This is in contrast to an account in which resources affect health contemporaneously, so that those in midlife now can expect to do better in old age as they receive Social Security and Medicare. None of this implies that there are no policy levers to be pulled; preventing the over-prescription of opioids is an obvious target that would clearly be helpful.

Introduction

Around the turn the century, after decades of improvement, all-cause mortality rates among white non-Hispanic men and women in middle age stopped falling in the US, and began to rise (Case and Deaton 2015). While midlife mortality continued to fall in other rich countries, and in other racial and ethnic groups in the US, white non-Hispanic mortality rates for those aged 45–54 increased from 1998 through 2013. Mortality declines from the two biggest killers in middle age—cancer and heart disease—were offset by marked increases in drug overdoses, suicides, and alcohol-related liver mortality in this period. By 2014, rising mortality in midlife, led by these “deaths of despair,” was large enough to offset mortality gains for children and the elderly (Kochanek, Arias, and Bastian 2016), leading to a decline in life expectancy at birth among white non-Hispan-ics between 2013 and 2014 (Arias 2016), and a decline in overall life expectancy at birth in the US between 2014 and 2015 (Xu et al 2016). Mortality increases for whites in mid-life were paralleled by morbidity increases, including deteriorations in self-reported physical and mental health, and rising reports of chronic pain.

Many explanations have been proposed for these increases in mortality and morbidity. Here, we examine economic, cultural and social correlates using current and historical data from the US and Europe. This is a daunting task whose completion will take many years; this current piece is necessarily exploratory, and is mostly concerned with description and interpretation of the relevant data. We begin, in Section I, by updating and expanding our original analysis of morbidity and mortality. Section II discusses the most obvious explanation, in which mortality is linked to resources, especially family incomes. Section III presents a preliminary but plausible account of what is happening; according to this, deaths of despair come from a long-standing process of cumulative disadvantage for those with less than a college degree. The story is rooted in the labor market, but involves many aspects of life, including health in childhood, marriage, child rearing, and religion. Although we do not see the supply of opioids as the fundamental factor, the prescription of opioids for chronic pain added fuel to the flames, making the epidemic much worse than it otherwise would have been. If our overall account is correct, the epidemic will not be easily or quickly reversed by policy, nor can those in mid-life today be expected to do as well after age 65 as do the current elderly. This does not mean that nothing can be done. Controlling opioids is an obvious priority, as is trying to counter the longer term negative effects of a poor labor market on marriage and child rearing, perhaps through a better safety net for mothers with children that would make them less dependent on unstable partnerships in an increasingly difficult labor market.

Preliminaries

A few words about methods. Our original paper simply reported a set of facts—increases in morbidity and mortality—that were both surprising and disturbing. The causes of death underlying the mortality increases were documented, which identified the immediate causes, but did little to explore underlying factors. We are still far from a smoking gun or a fully developed model, though we make a start in Section III. Instead, our method here is to explore and expand the facts in a range of dimensions, by race and ethnicity, by education, by sex, by trends over time, and by comparisons between the US and other rich countries. Descriptive work of this kind raises many new facts that often suggest a differential diagnosis, that some particular explanation cannot be universally correct because it works in one place but not another, either across the US, or between the US and other countries. At the same time, our descriptions uncover new facts that need to be explained and reconciled.

Two measures are commonly used to document current mortality in a population: life expectancy, and age-specific mortality. Although related, and sometimes even confused—many reports of our original paper incorrectly claimed that we had shown that life expectancy had fallen—they are different, and the distinction between them is important. Life expectancy at any given age is an index of mortality rates beyond that age and is perhaps the more commonly used measure (for recent examples, see Chetty et al 2016, Currie and Schwandt 2016, CDC 2015). Life expectancy at age a is a measure of the number of years a hypothetical person could be expected to live beyond a if current age-specific mortality rates continue into the future; it is a function of mortality rates alone, and does not depend on the age structure of the population. Life expectancy without qualification refers to life expectancy at birth (age zero), and is the number most often quoted; however, when mortality rates at different ages move in different directions, life expectancy trends can also differ by age. The calculation of life expectancy attaches to each possible age of death the probability of surviving to that age and then dying, using today’s survival rates. Because early mortality rates enter all future survival probabilities, life expectancy is more sensitive to changes in mortality rates the earlier in life these occur; the oft-used life expectancy at birth is much more sensitive to saving a child than saving someone in midlife or old age, and changes in life expectancy can mask offsetting changes occurring in earlier and later life. In our context, where mortality rates are rising in midlife, but falling among the elderly and among children, life expectancy at birth will respond only slowly—if at all. If middle-aged mortality is regarded as an indicator of some pathology, whether economic or social—the canary in the coalmine—or an indicator of economic success and failure, Sen (1998), life expectancy is likely to be a poor and insensitive indicator. The focus of our analysis is therefore not life expectancy but age-specific mortality, with rates defined as the number of deaths in a population of a given age, per 100,000 people at risk.

Our earlier work reported annual mortality results for white non-Hispanic men and women (together) aged 45 to 54 in the years between 1990 and 2013. In this paper, we present a more complete picture of midlife mortality—by sex and education group, over the full age range of midlife, using shorter age windows, over time, by cause, and by small geographic areas. Dissecting changes over space, and across age, gender and education helps us to match facts against potential explanations for the epidemic. We use data on mortality and morbidity from the US and other OECD countries, as well as data on economic and social outcomes, such as earnings, income, labor force participation, and marital status.

We shall be much concerned with education, and work with three educational groups, those with a high school degree or less, those with some college but no BA, and those with a BA or more. Among white non-Hispanics ages 45–54, the share of each education group in the population has seen little change since the early 1990s, with those with no more than a high school degree comprising approximately 40 percent, some college, 30 percent, and a BA or more, 30 percent. We do not focus on those with less than a high school degree, a group that has grown markedly smaller over time, and is likely to be increasingly negatively selected on health. Whether or how education causes better health is a long-unsettled question on which we take no position, but we show health outcomes by education because they suggest likely explanations. For the midlife group, the unchanging educational composition since the mid-1990s rules out one explanation, that the less educated group is doing worse because of selection, as could be the case if we had worked with high-school dropouts. When we examine other age, ethnic, or racial groups, or midlife white non-Hispanics in periods before the mid-1990s, the underlying educational compositions are not constant, and selection into education must be considered as an explanation for the evidence. More generally, we note the obvious point that people with more or less education differ in many ways, so that there can be no inference from our results that less educated people would have had the same health outcomes as more educated people had they somehow been “dosed” with more years of schooling.

Our data on mortality rates come from the CDC through the CDC-Wonder website; mortality by education requires special calculation, and full details of our sources and procedures are laid out in a Data Appendix.

Early commentary on our work focused on our lack of age adjustment within the age group 45–54 (Gelman and Auerbach 2016). Indeed the average age of white non-Hispanics (WNH) aged 45–54 increased by half a year between 1990 and 2015 so that part of the mortality increase we documented is attributable to this aging. Gelman and Auerbach’s age-adjusted mortality rates for WNHs in the 45–54 year age group show that the increase in all-cause mortality is larger for women, a result we have confirmed on the data to 2015 (36 per 100,000 increase for women, 9 per 100,000 increase for men, between 1998 and 2015, (single-year) age-adjusted using 2010 as the base year, with little variation in the increases when we use different base years). In the current analysis, we work primarily with five-year age groups, and we have checked that age-adjustment makes essentially no difference to our results with these groups; for example, for US WNHs aged 50–54, average age increased by only 0.09 years from 1990 to 2015.

Age-adjustment can be avoided by working with mortality by individual year of age, though the resulting volume of material can make presentation problematic. In the Graphical Appendix, we present selected results by single year of age, which can be compared to results in the main text. We discuss the separate experience of men and women in some detail below; unless there is indication otherwise, results apply to men and women together.

I. Mortality and morbidity in the US and other rich countries

I.A Documenting mortality

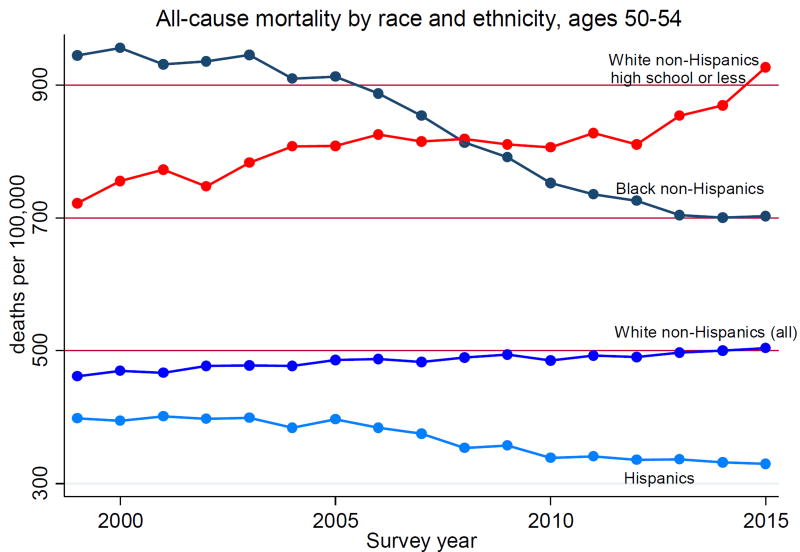

Increasing midlife white mortality rates, particularly for whites with no more than a high school degree, stand in contrast to mortality declines observed for other ethnic and racial groups in the US, and those observed in other wealthy countries. Figure 1.1 shows mortality rates per 100,000 for men and women (combined) aged 50 to 54 from 1999 to 2015. We show separate mortality rates for black non-Hispanics, for Hispanics and for all white non-Hispanics as well as for the subset of white non-Hispanics with no more than a high school degree. The top line shows rapid mortality decline for blacks, while the bottom line shows that Hispanics continue to make progress against mortality at a rate of improvement that, as we shall see, is similar to the rate of mortality decline in other rich countries. In contrast, white non-Hispanics are losing ground. White non-Hispanic men are doing less badly than white non-Hispanic women, a distinction not shown here but examined in detail below, but mortality rates for both were higher in 2015 than in 1998. While we do not have data on white non-Hispanics before 1989, we can track mortality rates for all whites aged 45–54 from 1900; during the 20th century, these mortality rates declined from more than 1,400 per 100,000 to less than 400 per 100,000. After the late 1930s, mortality fell year by year, with the exception of a pause around 1960 (likely attributable to the rapid increase in the prevalence of smoking in the 1930s and 40s) with rapid decline resuming from 1970 with improved treatments for heart disease. In this historical context of almost continuous improvement, the rise in mortality in midlife is an extraordinary and unanticipated event.

Figure 1.1.

All-cause mortality by race and ethnicity, men and women, ages 50–54

Mortality rates of black non-Hispanics aged 50–54 have been and remain higher than those of white non-Hispanics aged 50–54 as a whole, but have fallen rapidly, by around 25 percent from 1999 to 2015; as a result of this, and of the rise in white mortality, the black-white mortality gap in this (and other) age group(s) has been closing, National Center for Health Statistics (2016), Fuchs (2016). In this regard, the top two lines in Figure 1.1 are of interest: mortality rates of non-Hispanic whites with a high school degree or less, which were around 30 percent lower than mortality rates of blacks (irrespective of education) in 1999 (722 vs. 945 per 100,000), by 2015 were 30 percent higher (927 vs. 703 per 100,000). The same mortality crossover between black non-His-panics and the least educated white non-Hispanics can be seen in Table 1 for every 5-year age group from 25–29 to 60–64; we note that for age-groups younger than 45, there has been a decline in the fraction of WNHs with only a high school degree, so that selection may be playing some role for these younger groups.

Table 1.

All-cause mortality rates, White non-Hispanics with high school or less (LEHS), and Black non-Hispanics (All)

| 1999 | 2015 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ages: | Whites- LEHS | Blacks - All | Whites - LEHS | Blacks - All |

| 25–29 | 145.7 | 169.8 | 266.2 | 154.6 |

| 30–34 | 176.8 | 212.0 | 335.5 | 185.5 |

| 35–39 | 228.8 | 301.4 | 362.8 | 233.6 |

| 40–44 | 332.2 | 457.4 | 471.4 | 307.2 |

| 45–49 | 491.2 | 681.6 | 620.1 | 446.6 |

| 50–54 | 722.0 | 945.4 | 927.4 | 703.1 |

| 55–59 | 1087.6 | 1422.8 | 1328.3 | 1078.9 |

| 60–64 | 1558.4 | 1998.3 | 1784.6 | 1571.1 |

Notes. Mortality rates are expressed as deaths per 100,000 people at risk.

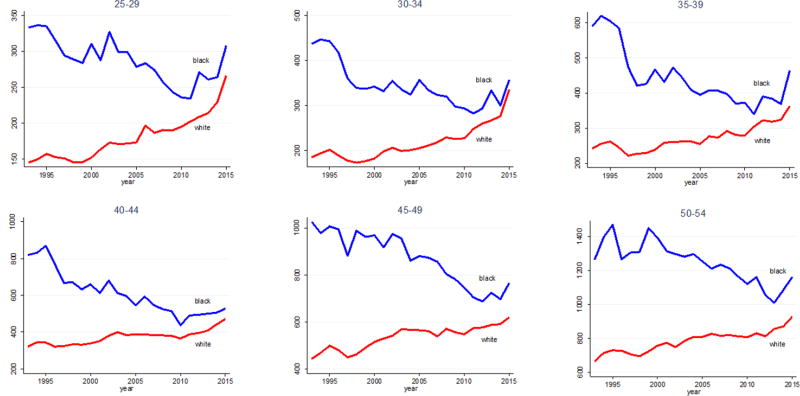

Figure 1.1 presents the comparison of white non-Hispanics with a high school degree or less with all black non-Hispanics—including those with some college or a college degree, who carry a lower risk of mortality. Putting black and white non-Hispanics with a high school degree or less head-to-head, Figure 1.2 shows that the black-white mortality gap has closed for every five-year age cohort between 25–29, and 50–54 year olds— due both to mortality declines for blacks, and mortality increases for whites. The racial gap in mortality among the least educated has all but disappeared. Again, we note the decline in the fraction of those with a high school degree or less education in younger age-cohorts; the declines are similar (20 percentage points) for WNHs and BNHs.

Figure 1.2.

All-cause mortality, black and white non-Hispanics with a high school degree or less education

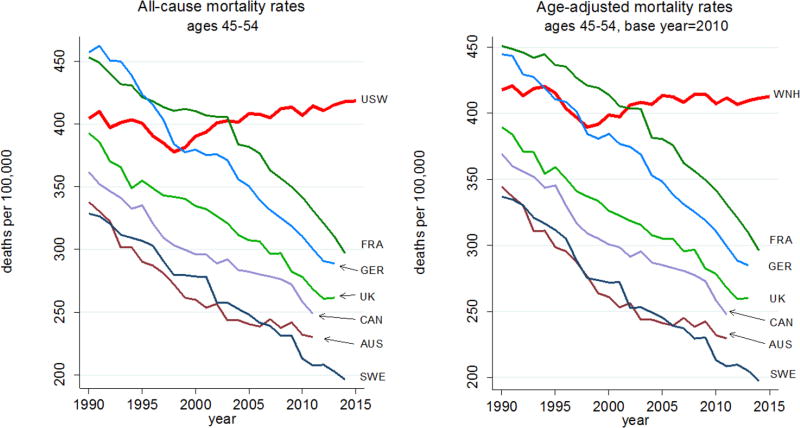

Figure 1.3 shows the comparison of the US with selected other rich countries (France, Germany, UK, Canada, Australia, and Sweden). This updates Figure 1 in Case and Deaton (2015), using the original ten-year age band, 45–54, adding years 2014 and 2015, and compares unadjusted mortality in the left-hand panel with (single year of) age-adjusted mortality in the right-hand panel. The US and comparison countries have been age adjusted within the age band using 2010 as the base year using mortality data for single years of age from the raw data. Age adjustment changes little, but somewhat smooths the rates of decline in comparison countries. Using the age-adjusted rates, every comparison country had an average rate of decline of 2 percent per year between 1990 and 2015. While white non-Hispanics saw that same decline until the late 1990s, it was followed by intermittent and overall mortality increases through 2015. Age-adjusted mortality rates of black non-Hispanics 45–54 fell by 2.7 percent per year from 1999 to 2015, and those of Hispanics by 1.9 percent.

Figure 1.3.

Appendix Figure 1 presents all-cause mortality by selected single year ages for ages 30, 40, 45, 50, 55 and 60. From age 30 through age 55, US mortality was (at best) not falling, and for some ages increased, while rates in other rich countries fell at all ages.

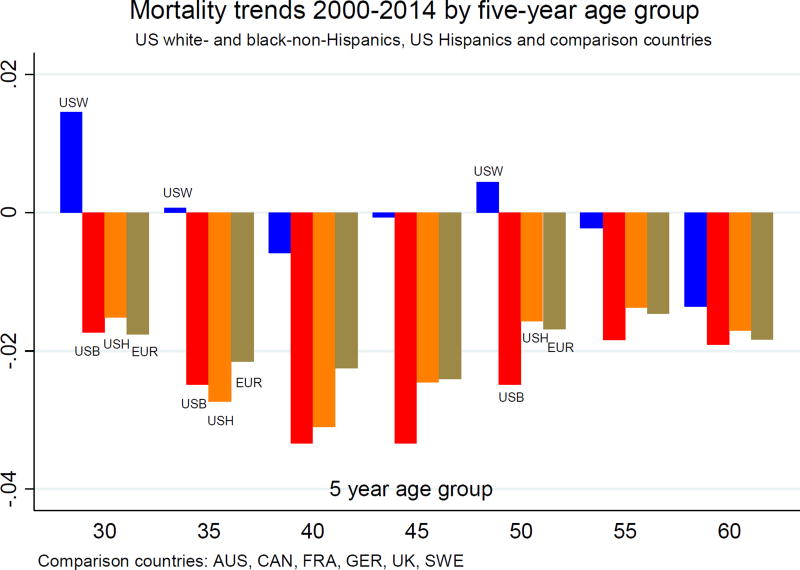

Figure 1.4 presents mortality rate trends for midlife five-year age groups from 2000–2014 for US white non-Hispanics, black non-Hispanics, and Hispanics, and average trends for the six comparison countries used above. (Five of six comparison countries reported deaths through 2013; three of six through 2014. Trends for comparison countries are estimated as the coefficient on the time trends from age-group specific regressions of log mortality on a time trend and on a set of country indicators.) White non-Hispanics aged 30–34 had mortality rate increases of almost 2 percent per year on average over this 15-year period. Changes in direction for mortality rates in young adulthood or early middle age, taken alone, are less uncommon and less surprising: death rates are low at these ages, and shocks can easily lead to a change of direction (for example, HIV in the US in the early 1990s). But the fact that the US has pulled away from comparison countries throughout middle age is cause for concern. Our main focus here is not on whether progress on all-cause mortality has only flat-lined or actually reversed course, although this was what attracted most public response to our original paper. Rather, our main point is that other wealthy countries continued to make progress while the US did not. As we have seen, black non-His-panics have higher mortality rates than whites, but their mortality has fallen even more rapidly than rates in Europe, while Hispanics, who have lower mortality rates than whites, had declines in rates similar to the average in comparison countries in all age groups.

Figure 1.4.

Mortality trends 2000–2014 by five-year age group, US Whites, US Blacks, US Hispanics, and comparison countries

Table 2 presents all-cause mortality trends for the 50–54 age band for US white non-Hispanics, black non-Hispanics and Hispanics and a larger set of comparison countries, now including Ireland, Switzerland, Denmark, the Netherlands, Spain, Italy and Japan. The numbers in the table are the coefficients on time in (country- and cause-specific) regressions of the logarithm of mortality for the cause in each column on a time trend, and the numbers can be interpreted as average annual rates of change. The mortality trend is positive for US whites, and negative for US black non-Hispanics, US His-panics, and for every other country. In this larger set of comparison countries, mortality rates for men and women aged 50–54 declined by 1.9 percent per year on average between 1999 and 2014, while rates for US white non-Hispanics increased by 0.5 percent a year.

Table 2.

Trends in mortality by cause, annual average rate of change 1999–2015, men and women 50–54

| Country or racial/ethnic group |

All-cause | Drugs, Alcohol, Suicide |

Heart dis- ease |

Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| US white non-Hispanics | 0.005 | 0.054 | −0.010 | −0.011 |

| US black non-Hispanics | −0.023 | 0.001 | −0.027 | −0.024 |

| US Hispanics | −0.015 | 0.010 | −0.025 | −0.015 |

| United Kingdom | −0.021 | 0.010 | −0.040 | −0.023 |

| Ireland | −0.026 | 0.030 | −0.051 | −0.023 |

| Canada | −0.011 | 0.025 | −0.030 | −0.018 |

| Australia | −0.010 | 0.025 | −0.028 | −0.018 |

| France | −0.013 | −0.012 | −0.029 | −0.017 |

| Germany | −0.019 | −0.023 | −0.035 | −0.021 |

| Sweden | −0.021 | 0.008 | −0.031 | −0.023 |

| Switzerland | −0.025 | −0.026 | −0.040 | −0.023 |

| Denmark | −0.018 | 0.001 | −0.047 | −0.026 |

| Netherlands | −0.023 | −0.000 | −0.055 | −0.014 |

| Spain | −0.021 | −0.003 | −0.032 | −0.020 |

| Italy | −0.021 | −0.022 | −0.047 | −0.020 |

| Japan | −0.022 | −0.021 | −0.014 | −0.028 |

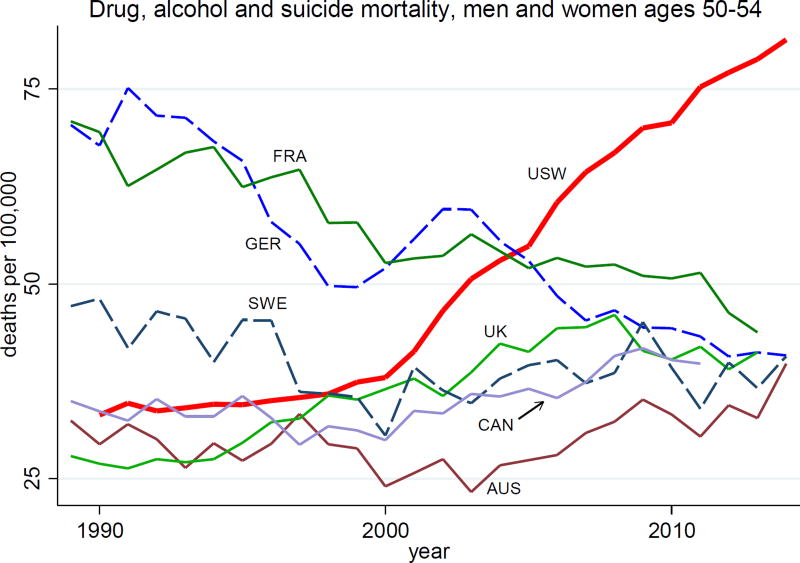

That deaths of despair play a part in the mortality turnaround can be seen in Figure 1.5, which presents mortality rates from alcohol and drug poisoning, suicide, and alcoholic liver disease and cirrhosis for US white non-Hispanic men and women (USW), and those in comparison countries, all aged 50–54. US whites had much lower mortality rates from drugs, alcohol and suicide than France, Germany or Sweden in 1990, but while mortality rates in comparison countries converged to around 40 deaths per 100,000 after 2000, those among US white non-Hispanics doubled, to 80 per 100,000. The average annual rate of change from 1999–2015 of mortality rates from “deaths of despair” are presented in column 2 of Table 2. For US black non-Hispanics, mortality from these causes has been constant at 50 deaths per 100,000 after 2000. The trends in other English speaking countries may provide something of a warning flag: the UK, Ireland, Canada and Australia stand alone among the comparison countries in having substantial positive trends in mortality from drugs, alcohol and suicide over this period. However, their increases are dwarfed by the increase among US whites.

Figure 1.5.

Deaths of despair, men and women, aged 50–54

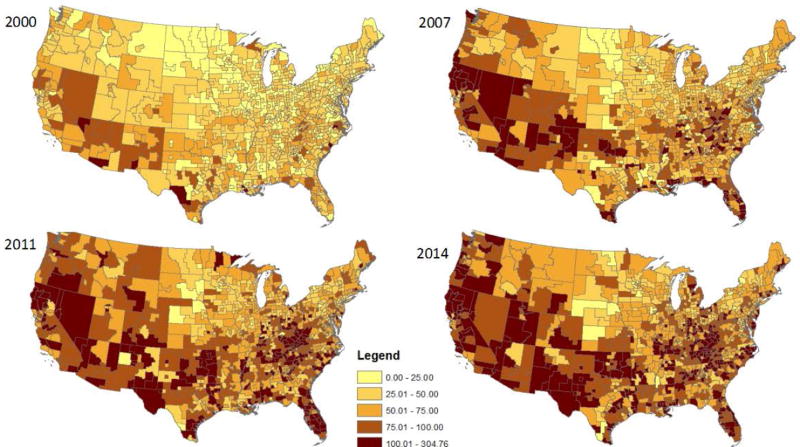

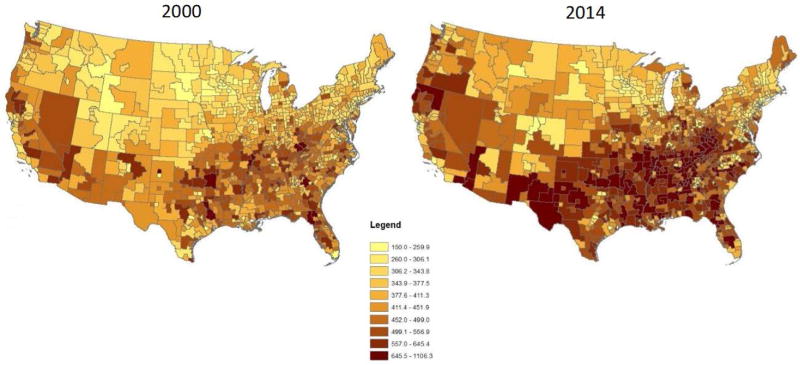

The epidemic spread from the southwest, where it was centered in 2000, first to Appalachia, Florida and the west coast by the mid-2000s, and is now countrywide (Figure 1.6). Rates have been consistently lower in the Large Fringe MSAs, but increases were seen at every level of residential urbanization in the US (Appendix Figure 2); it is neither an urban nor a rural epidemic, rather both.

Figure 1.6.

Drug, alcohol and suicide mortality, white non-Hispanics ages 45–54

The units in Figure 1.6 are small geographic units that we refer to as coumas, a blend of counties and PUMAs (Public Use Microdata Areas). For counties that are larger than PUMAs, the couma is the county and is comprised of PUMAs, while in parts of the country where counties are sparsely populated, one PUMA may contain many counties, and the PUMA becomes the couma. (Details are provided in the Data Appendix.) We have constructed close to 1,000 coumas, which cover the whole of the US, with each containing at least 100,000 people. The geography of mortality will be explored in detail in future work; we note here that some coumas have relatively few deaths in the age group illustrated, so the coloring of the maps has a stochastic component that can be misleading for sparsely populated coumas that cover large geographical areas. That said, the spread from the southwest matches the story in Quinones (2015), who documents the interplay between illegal drugs from Mexico and legal prescription drugs throughout the US. Most recently, with greater attempts to control prescription of opioids, deaths from illegal drugs are becoming relatively more important, Hedegaard et al. (2017).

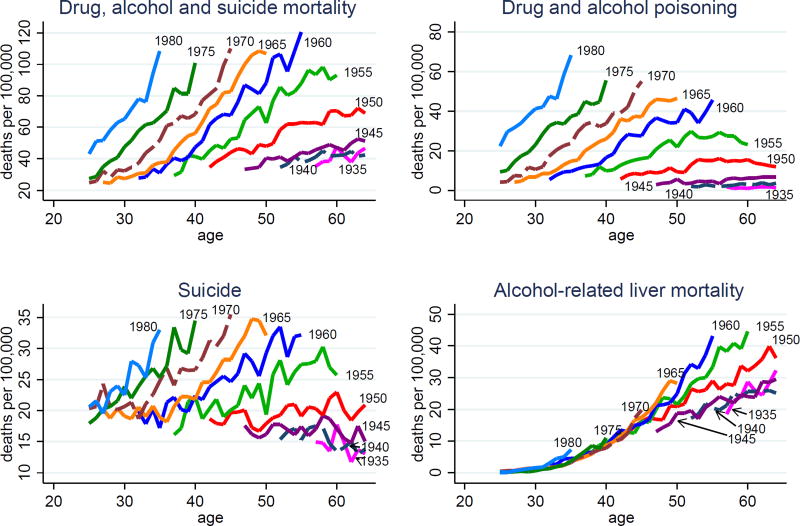

We now turn to birth cohorts, beginning with the cohort born in 1935; this analysis is important for the story that we develop in Section III below. (Note that, over this much longer period, the fraction of each birth cohort with a BA or more education rose. Specifically, in the birth cohorts we analyze in Section III—those born between 1945 and 1980—the fraction of whites with a BA remained constant at 30 percent between 1945 and 1965, increased from 30 percent to 40 percent of the cohorts born between 1965 and 1970, and remained stable at 40 percent for cohorts born between 1970 and 1980.)

Figure 1.7 shows mortality rates for birth cohorts of white non-Hispanics with less than a BA at five year intervals from birth years from 1935 to 1980, from drug overdoses (top right panel), suicide (bottom left), alcohol-related liver deaths (bottom right), and all three together (top left). After the 1945 cohort, mortality rises with age in each birth cohort for all three causes of death; moreover, the rate at which mortality rises with age is higher in every successive birth cohort. The rise in mortality by birth cohort is not simply a level shift but also a steepening of the age-mortality profiles at least until the youngest cohorts. Repeating the figure for all education levels pooled yields qualitatively similar results, but with the upward movement and the steepening slightly muted (Appendix Figure 3); we shall return to the issue of selection into education in Section III below.

Figure 1.7.

Drug, alcohol and suicide mortality by birth cohort, white non-Hispanics, less than BA

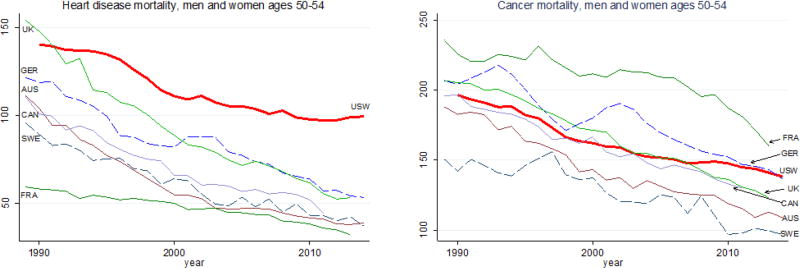

As noted by Meara and Skinner (2015) in their commentary on Case and Deaton (2015), increases in mortality from deaths of despair would not have been large enough to change the direction of all-cause mortality for US whites had this group maintained its progress against other causes of death. For the two major causes of death in midlife, heart disease and cancer, the rate of mortality decline for age groups 45–49 and 50–54 fell from 2 percent per year on average between 1990 and 1999 to 1 percent per year between 2000–2014. The left panel of Figure 1.8 presents heart disease mortality rates for US white non-Hispanics and comparison countries from 1990–2014. US whites began the 1990s with mortality rates from heart disease that were high relative to other wealthy countries and, while rates continued to fall elsewhere, the rate of decline first slowed in the US, and then stopped entirely between 2009 and 2015. With respect to cancer (right panel of Figure 1.8), US whites began the 1990s in the middle of the pack; again, if in less dramatic fashion, progress for US whites slowed after 2000. The last two columns in Table 2 show that, for both heart disease and cancer, US whites ages 50–54 had less than half the rate of decline observed for US blacks and almost all of the comparison countries in the period 1999–2014.

Figure 1.8.

Heart disease and cancer mortality, ages 50–54, US white non-Hispanics and comparison countries

The slowdown in progress on cancer can be partially explained by smoking: the decline in lung cancer mortality slowed for white non-Hispanic men ages 45–49 and 50–54 in 2000–2014, and the mortality rate increased for women 45–49 between 2000 and 2010. (See Appendix Figure 4.) This puts the progress made against lung cancer by US whites toward the bottom of the pack in comparison with US blacks and with other wealthy countries.

Explaining the slowdown in progress in heart disease mortality is not straightforward. Many commentators have long predicted that obesity would eventually have this effect, and see little to explain, e.g. Flegal et al (2005), Olshansky et al (2005), Lloyd-Jones (2016). But the time, sex, and race patterns of obesity do not obviously match the patterns of heart disease. While obesity rates are rising more rapidly among blacks than among whites in the US, blacks made rapid progress against heart disease in the period 1999–2015 (see Table 2 and Appendix Figure 5). Beyond that, if the US is a world leader in obesity, Britain is not far behind, with 25 percent of the adult population obese, compared with 28 percent among US WNH, but Britain shows a continued decline in mortality from heart disease. Stokes and Preston (2017) argue persuasively that deaths attributable to diabetes are understated in the US, perhaps by a factor of four, so that the additional obesity-related deaths from diabetes are not being measured but may be incorrectly being attributed to heart disease. They note that when diabetes and cardiovascular disease are both mentioned on a death certificate, “whether or not diabetes is listed as the underlying cause is highly variable and to some extent arbitrary.” (p. 2/9) If this happens in other countries, it might also explain the slowing of heart disease progress in other rich countries in which obesity rates are rising. Returning to six comparison countries examined earlier (AUS, CAN, FRA, GER, SWE, UK), we find that on average the decline in heart disease slowed from 4.0 percent per year (1990–99) to 3.2 percent (2000–2014), see Figure 1.8. The contribution of obesity and diabetes to the mortality increases documented here clearly merits additional attention.

Mortality rates increased at different rates in different parts of the country in the period 1999–2015. Of the nine census divisions, the hardest hit was East South Central (Alabama, Kentucky, Tennessee and Mississippi), which saw mortality rates rise 1.6 percent per year on average for white non-Hispanics 50–54, increasing from 552 to 720 deaths per 100,000 over this period. Mortality rates fell in the Mid-Atlantic division, held steady in New England and the Pacific division, but grew substantially in all other divisions. A more complete picture of the change in mortality rates can be seen in Figure 1.9, which maps mortality rates for white non-Hispanics, ages 45–54, by the coumas introduced above. The left (right) panel of Figure 1.9 presents mortality rates by couma in 2000 (2014). With the exception of the I-95 corridor, and parts of the upper Midwest, all parts of the US have seen mortality increases since the turn of the century; 70 percent of coumas saw mortality rate increases between 2000 and 2011 (the last year in which the PUMAs drawn for 2000 allow a decade-long alignment of coumas.) Mortality rates for WNHs aged 45–54 trended downward in only three states over the period 1999–2015: California, New Jersey and New York. Although the media often report the mortality turnaround as a rural phenomenon, all-cause mortality of white non-Hispanics aged 50–54 rose on average one percent a year in four of six residential classifications between 1999 and 2015—Medium MSAs, Small MSAs, Micropolitan Areas, and Noncore (non-MSA) areas. Mortality rates were constant in Large Fringe MSAs over this period, and fell weakly (0.3 percent per year on average) in the Large Central MSAs.

Figure 1.9.

All-cause mortality, white non-Hispanics, ages 45–54

By construction, mortality from deaths of despair and all-cause mortality are highly correlated; deaths of despair are a large and growing component of midlife all-cause mortality. But it is important to remember that changes in all-cause mortality are also driven by other causes, particularly heart disease and cancer, and that progress on those varies from state to state. Take, for example, mortality in two states that are often used to show the importance of health behaviors—Nevada and Utah. Two-thirds of Uta-hans are Mormon; LDS adherence requires abstinence from alcohol, coffee, and to-bacco. Two-thirds of Nevadans live in the Las Vegas-Henderson-Paradise MSA. Ranking states by their all-cause mortality rate for WNH aged 45–54, we find that Nevada ranked 9th highest among all states in 2014; Utah ranked 31st. Heart disease mortality was twice as high in Nevada in 2014 as it was in Utah (119 per 100,000 vs 59 per 100,000). However, both Nevada and Utah were among the top-ten states ranked by mortality from drugs, alcohol and suicide in that year. Nevada was 4th highest, with 117 deaths per 100,000, and Utah was 10th, with 99 deaths per 100,000 WNH aged 45–54. The suicide rate doubled in Utah in this population between 1999 and 2014, and the poisoning rate increased 150 percent. Different forces—social and economic, health-behavior and health-care related—may drive changes in some causes of death, but not others, and these forces themselves are likely to change with time.

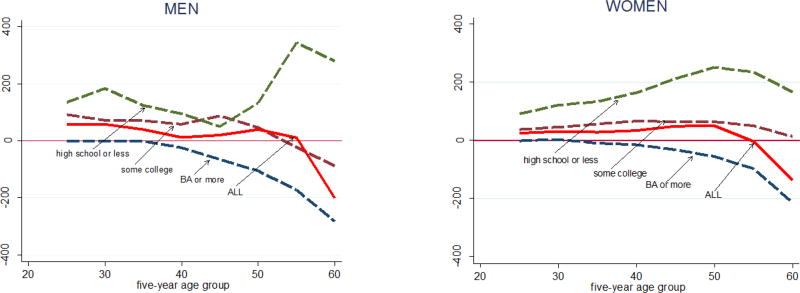

As we saw in Figure 1.1, changes in US mortality rates for WNHs differ starkly by level of education. Figure 1.10 shows this for men and women separately. Changes in mortality rates between 1998 (the year with the lowest mortality rate for those aged 45–54) and 2015 are tracked by five-year age cohort, with men in the left panel, and women in the right. From ages 25–29 to ages 55–59, men and women with less than a four-year college degree saw mortality rates rise between 1998 and 2015, while those with a BA or more education saw mortality rates drop, with larger decreases at higher ages. Overall, this resulted in mortality rate increases for each five-year age group, taking all education groups together, marked by the solid red lines in Figure 1.10. Although there are some differences between men and women, the patterns of changes in mortality rates are broadly similar in each education group.

Figure 1.10.

Change in mortality rates, white non-Hispanics 1998–2015

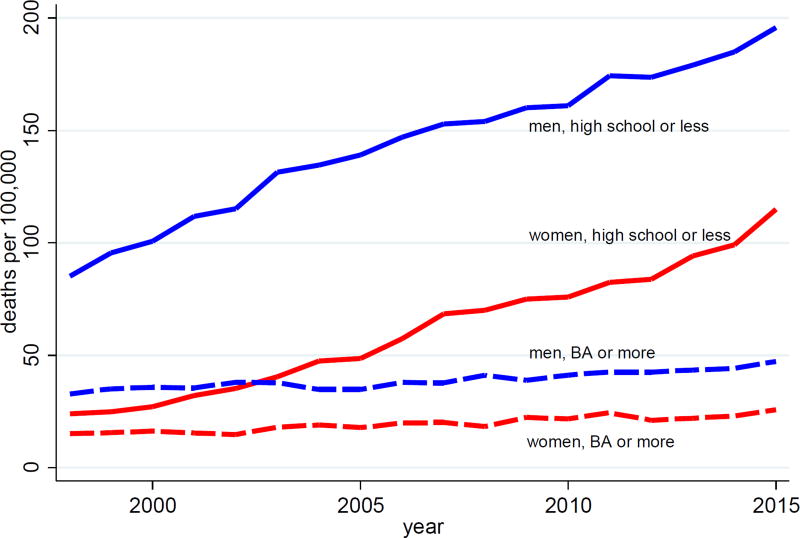

The key story in this Figure is the increase in mortality rates for both men and women without a BA, particularly for those with no more than a high school degree. For WNH aged 50–54, Figure 1.11 compares deaths of despair for men and women with a high school degree or less (approximately 40 percent of this population over the period 1999 to 2015) to those with a BA or more (32–35 percent). For both men and women with less education, deaths of despair are rising in parallel, pushing mortality upwards. However, the net effect on all-cause mortality depends on what is happening to deaths from heart disease and from cancer, including lung cancer, and those other causes have different patterns for men and women. We shall document these findings in more detail in future work.

Figure 1.11.

Drug, Alcohol and Suicide Mortality, white non-Hispanics 50–54

Over this period, the disparity in mortality grew markedly between those with and without a BA. The mortality rate for men with less than a BA aged 50–54, for example, increased from 762 per 100,000 to 867 between 1998 and 2015, while for men with a BA or more education, mortality fell from 349 to 243. Those with less than a BA saw progress stop in mortality from heart disease and cancer, and saw increases in chronic lower respiratory disease and deaths from drugs, alcohol, and suicide (Appendix Figure 6). Moreover, increasing differences between education groups are found for each component of deaths of despair—drug overdoses, suicide, and alcohol-related liver mortality—analyzed separately (Appendix Figure 7).

Our findings on the widening educational gradient in Figure 1.10 are consistent with and extend a long literature, recently reviewed, for example, by Hummer and Hernandez (2016). Kitigawa and Hauser (1973) first identified educational gradients in mortality in the US, and later work, particularly Elo and Preston (1995), found that the differences widened for men between 1970 and 1980. Meara, Richards, and Cutler (2005) show a further widening from 1981 to 2000, including an absolute decline in life expectancy at 25 for low-educated women between 1990 and 2000. They show that there was essentially no gain in adult life expectancy from 1981–2000 for whites with a high school degree or less, and that educational disparities widened, for men and women, and for whites and blacks. A widely reported study by Olshansky et al (2012) found that life expectancy of white men and women without a high school degree decreased from 1990 to 2008. Given that the fraction of population without a high school degree declined rapidly over this period and if, as is almost certain, that fraction was increasingly negatively selected, the comparison involves two very different groups, one that was much sicker than the other when they left school, see Begier et al (2013). Bound et al (2014) address the issue by looking at changes in mortality at different percentiles of the educational distribution and find no change in the survival curves for women at the bottom educational quartile between 1990 and 2010 and an improvement for men.

Our own findings here are more negative than those in the literature. Figure 1.10 shows that mortality rates for those with no more than a high school degree increased from 1998–2015 for white non-Hispanic men and women in all five-year age groups from 25–29 to 60–64. We suspect that these results differ from Meara et al (2005) because of the large differential increase in deaths from suicides, poisonings, and alcoholic liver disease after 1999 among whites with the lowest educational attainment, see again Figure 1.11.

Mortality differentials by education among whites in the US contrast with those in Europe. In a recent study, Mackenbach et al (2016) examine mortality data from eleven European countries (or regions) over the period 1990–2010, and find that, in most cases, mortality rates fell for all education groups, and fell by more among the least educated, so that the (absolute) differences in mortality rates by education have diminished. (Disparities have increased in relative terms because the larger decreases among the less well educated have been less than proportional to their higher baseline mortality rates.)

I.B Documenting morbidity

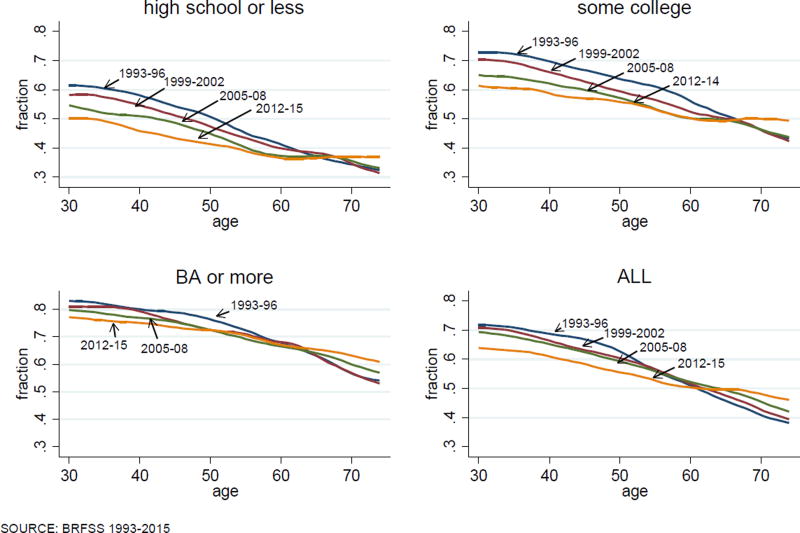

Large and growing education differentials in midlife mortality are paralleled by reported measures of midlife health and mental health. Figure 1.12 presents levels and changes over time (1993–2015) in the fraction of white non-Hispanics at each age between 35 and 74 who report themselves in “excellent” or “very good” health (on a five-point scale that includes “good, fair or poor” as options). That self-assessed health falls with age is a standard (and expected) result, and can be seen in all three panels, each for an education group. In the period 1999–2002, there are marked differences between the education groups in self-assessed health: 72 percent of 50 year olds with a BA or more report themselves in excellent/very good health, true of 59 percent of those with some college education, and only 49 percent of those with a high school degree or less. Over the period 1999–2015, differences between education groups became more pronounced, with fewer adults in lower education categories reporting excellent health at any given age. In 2012–15, at age 50, the fraction of BAs reporting excellent health had not changed, while that fraction fell 4 percentage points for those with some college, and 7 percentage points for those with a high school degree or less. (Beyond retirement age, which saw progress against mortality in the early 2000s, self-assessed health registers improvement as well.)

Figure 1.12.

Fraction white non-Hispanics reporting excellent/very good health

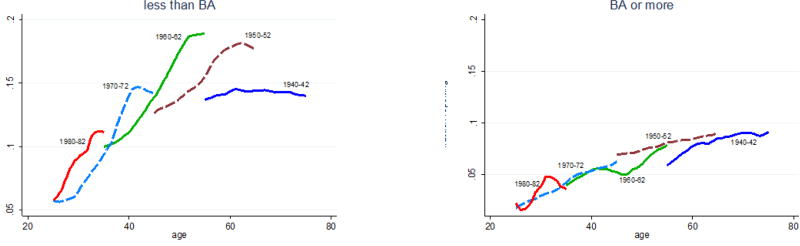

Since the mid-1990s (when questions on pain and mental health began to be asked annually in the National Health Interview Survey), middle-aged whites reports of chronic pain and mental distress have increased, as have their reports of difficulties with activities of daily living (Case and Deaton 2015). Figure 1.13 presents results for white non-Hispanic reports of sciatic pain, for birth cohorts spaced by ten years, separately for those with less than a four-year college degree (left panel), and those with a BA or more education (right panel). Pain is a risk factor for suicide and, as the left panel shows, for those with less than a college degree there has been a marked increase between birth cohorts in reports of sciatic pain. As was the case for mortality, the age-profiles for pain steepen with each successive birth cohort. For those with a BA, successive birth cohorts overlap in their reports of pain at any given age, while for those with less education, an ever-larger share report pain in successive cohorts. Similar results obtain for other morbidities.

Figure 1.13.

Fraction reporting sciatic pain, white non-Hispanics by birth year and education class

II. Mortality and incomes

II.A Introduction

Much of the commentary has linked the deteriorating health of midlife whites to what has happened to their earnings and incomes, and in particular to stagnation in median wages and in median family incomes. Because there has been real growth in per capita GDP and in mean per capita income, the poor performance for middle-class incomes can be mechanically attributed to the rising share of total income captured by the best-off Americans. This suggests an account in which stagnant incomes and deteriorating health become part of the narrative of rising income inequality, see Stiglitz (2015) for one provocative statement. According to this, the rise in suicides, overdoses, and alcohol abuse would not have occurred if economic growth had been more equally shared. Quite apart from the question of whether, if the top had received less, the rest would have received more, we shall see that the economic story can account for part of the increases in mortality and morbidity, but only a part, and that it leaves more unexplained than it explains. Our preliminary conclusion is that, as in previous historical episodes, the changes in mortality and morbidity are only coincidentally correlated with changes in income.

II.B Contemporaneous evidence

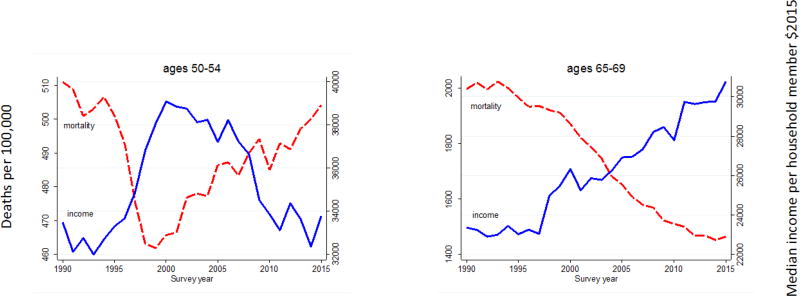

For middle-aged whites, there is a strong correlation between median real household income per person and mortality from 1980 and 2015; an inverse U-shaped pattern of real income, rising through the 1980s and 1990s and falling thereafter, matches the U-shape of mortality, which fell until 1998 and was flat thereafter. After 1990, we can separate out Hispanics and look at white non-Hispanics, for whom the recent mortality experience was worse than for whites as a whole. The left panel of Figure 2.1 shows, for households headed by white non-Hispanics aged 50–54, real median household income per member from March CPS files (presented as solid blue lines), and (unadjusted all-cause) mortality rates for men and women aged 50–54 together (dashed red lines). Mortality and income match closely The right panel shows mortality for the age group 65–69, and median real income per member in households headed by someone in that age band. This older group has done well since 1990 in part because, for those who qualify, initial Social Security payments are indexed to average wages and are subsequently indexed to the CPI; average wages have done better than median wages. Real incomes for those aged 65–69 increased by a third between 1990 and 2015, while incomes for (all) middle-aged groups show an initial increase followed by subsequent decline, though the timing and magnitudes are different across age groups. Appendix Figure 8 shows that while the matching of mortality and household income is strongest for the 50–54 age group, it appears at other ages too, albeit less clearly. This looks like good evidence for the effects of income on mortality, not at an annual frequency, which the graphs clearly show is not the case, but because of the (approximate) matching of the timing of the turnarounds across age groups.

Figure 2.1.

Median household income per member and all-cause mortality, white non-Hispanics by age group

When we disaggregate by educational attainment in Figure 2.2, there is less support for an income-based explanation for mortality. The left-hand panel shows year margins for log median real income per member, for householders aged 30–64, from regressions of log median real income per member on householder age effects and year effects, run separately by education group. The general widening inequality in family incomes in the US does not show up here in any divergence between the median incomes of those with different educational qualifications, and does not match the divergence in mortality between education groups, discussed above and seen in the right-hand panel. The negative correlation between mortality and income could be restored by removing the divergent trends from mortality, yet there seems no principled reason to do so.

Figure 2.2.

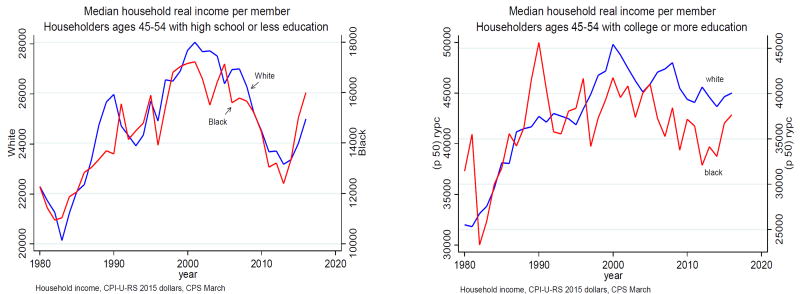

The matching of income and mortality fares poorly both for black non-Hispanics and for Hispanics. Black household incomes rose and fell in line with white household incomes for all age groups between 1990 and 2015 and indeed, after 1999, blacks with a college education experienced even more severe percentage declines in income than did whites in the same education group (Figure 2.3). Yet black mortality rates have fallen steadily, at rates between 2 and 3 percent per year for all age groups 30–34 to 60–64, see Figure 1.4 above. The data on Hispanic household incomes are noisier, but, once again, there is no clear difference between their patterns and those for whites, but their mortality rates have continued to decline at the previously established rate, which is the “standard” European rate of two percent a year, see again Figure 1.4.

Figure 2.3.

Median household income per member, householders aged 45–54

We do not (currently) have data on household median incomes for all of the comparison countries, but EUROSTATs Survey of Income and Living Conditions (SILC) provides data from 1997 for Spain, Germany, France, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, and the UK, and for Denmark from 2003, Sweden from 2004, and for Switzerland from 2007. The European patterns (for all households, the data do not allow age disaggregation) are quite different from those among US households and fall into two classes, depending on the effects of the Great Recession. In Italy, Spain, Ireland, the Netherlands and the UK, median real family incomes rose until the recession, and were either stagnant or declining thereafter. In the other countries, Germany, France, Sweden, and Denmark, there was no slowdown in household incomes after 2007. As we have seen in Figure 1.3 and Table 2, there is no sign of differences between these two groups in the rates of mortality decline, nor of any slowing in mortality decline as income growth stopped or turned negative. If incomes work in Europe as they work in the US, and if the income turnaround is responsible for the mortality turnaround in the US, we would expect to see at least a slowing in mortality decline in Europe, if only among the worst affected countries, but there is none.

II.C Discussion

Taking all of the evidence together, we find it hard to sustain the income-based explanation. For white non-Hispanics, the story can be told, especially for those aged 50–54, and for the difference between this group and the elderly, but we are left with no explanation for why Blacks and Hispanics are doing so well, nor for the divergence in mortality between college and high-school graduates, whose mortality rates are not just diverging, but going in opposite directions. Nor does the European experience provide support, because the mortality trends show no signs of the Great Recession in spite of its marked effects on household median incomes in some countries but not in others.

It is possible that it is not the last 20 years that matters, but rather that the long-run stagnation in wages and in incomes has bred a sense of hopelessness. But Figure 2.4 shows that, even if we go back to the late 1960s, the ethnic and racial patterns of median family incomes are similar for whites, blacks, and Hispanics, and so can provide no basis for their sharply different mortality outcomes after 1998. Even so, in the next section, we develop an account that could implicate the long-term decline in earnings among lower educated whites.

Figure 2.4.

Median incomes by race and ethnicity

There is a microeconomic literature on health determinants that shows that those with higher incomes have lower mortality rates and higher life expectancy, see National Academy of Sciences (2015) and Chetty et al (2016) for a recent large-scale study for the US. Income is correlated with many other relevant outcomes, particularly education, which, like race and ethnicity, is not available to Chetty et al; even so there are careful studies on smaller panels, such as Elo and Preston (1996), that find separately protective effects of income and education, even when both are allowed for together with controls for age, geography, and ethnicity. These studies attempt to control for the obviously important reverse effect of health on income by excluding those who are not in the labor force due to long-term physical or mental illness, or by not using income in the period(s) prior to death. Even so, there are likely also effects that are not eliminated in this way, for example, that operate through insults in childhood that impair both adult earnings and adult health. Nevertheless, it seems likely that income is protective of health, at least to some extent, even if it is overstated in the literature that does not allow for other factors.

There is a somewhat more contested literature on income and mortality at business cycle frequencies. Sullivan and von Wachter (2009) use administrative data to document the mortality effects of unemployment among high seniority males, and Coile, Levine, and McKnight (2014) note the vulnerability to unemployment of older, but pre-retirement workers, who are unlikely to find new jobs and may be forced into early retirement, possibly without health insurance. The mortality effects that they and Sullivan and von Wachter document are not all instantaneous, but are spread over many years and are, in any case, much smaller than the effects that would be required to justify the results in Figure 2.1 for those aged 50–54. At the aggregate level, unemployment cannot explain the mortality turnarounds in the post-2000 period; unemployment had recovered its pre-recession level by the end of the period, and was falling rapidly as mortality rose. It is of course possible that the aggregate is misleading, either because unemployment excludes discouraged workers, or because unemployment has not recovered in the places where unemployment prompted mortality; see Pierce and Schott (2016) and Autor et al (2017) for evidence linking mortality to trade-induced unemployment.

There is, however, evidence against the unemployment story from Spain in Regidor et al (2016) who use individual level data for the complete population of Spain to study mortality in 2004–2007 compared with 2008–2011. In spite of the severity of the Great Recession in Spain, with unemployment rates rising from 8.2 percent in 2007 to 21.4 percent in 2011, mortality was lower in the later period. This was true for most causes of death, including suicide, and for people of high or low wealth, approximately measured by floor space or car ownership in 2001, as well as for age groups 10–24, 25–49, and 50–74 taken separately.

There is a venerable literature arguing that good times are bad for health, at least in the aggregate. As early as Ogburn and Thomas (1922), it was noted that mortality in the US was pro-cyclical, with the apparently paradoxical finding that mortality rates are higher in booms than in slumps. The result has been frequently but not uniformly confirmed in different times and places; perhaps the best-known study in economics is Ruhm (2009) who uses time series of states in the US. Ruhm (2015), who grapples with the same data as here, questions whether it remains true that recessions are good for health. A frequent finding is that traffic fatalities are pro-cyclical, as are the effects of pollution, Cutler et al (2016). Suicides are often found to move in the opposite direction, along with mortality from unemployment, to which they likely contribute. Stevens et al (2016) find that in the US, many of the deaths in “good” times are among elderly women, and implicate the lower staffing levels in care facilities when labor is tight; pro-cyclical deaths from influenza and pneumonia show up in several studies, again suggesting the importance of deaths among the elderly. To the extent that the positive macro relationship between mortality and income is driven by mortality among the elderly, it makes it easier to tell a story of income being protective among the middle-age groups such as those on which we focus here.

Our own interpretation is that there is likely some genuine individual-level positive effect of income on health, but that it is swamped by other macro factors in the aggregate. Of the results here, particularly those shown in Figure 2.1, we suspect that the matching relationships are largely coincidental, as has happened in other historical episodes.

The argument for coincidence is well illustrated by disaggregating the left panel of Figure 2.1 by cause of death. As shown in Section 1, when we look at all-cause mortality, we need to think about “deaths of despair” (suicides, overdoses, and alcoholism) together with heart disease. Deaths of despair have been rising at an accelerating rate since 1990 but, for a decade, were offset by other declining causes of mortality, including heart disease. After 1999, the deaths of despair continued to rise, but were now much larger, while the decline in heart disease slowed and eventually stopped, so that overall mortality started to go up. Both of the components are smooth trends, one rising and accelerating, the other falling but decelerating. Neither one in isolation has any relation to what has been happening to income, but together, they generate a turnaround that, by chance, coincides with the inverse U in family incomes. Spurious common U’s are almost as easy to explain as spurious common trends.

In the long history of the coevolution of health and income, such coincidences are not uncommon. The Industrial and Health Revolutions that began in the 18th century both owe their roots to the Enlightenment and the Scientific Revolution, but neither one drove the other, see Easterlin (1999) for a persuasive account. In developing countries today, health is largely driven by public action that requires money, but the use of that money for action on health is far from automatic and depends on policy, Deaton (2013).

A more recent episode comes after 1970 in the US, when economic growth slowed while the rate of mortality decline accelerated rapidly. Mean real per capita personal disposable income grew at 2.5 percent per annum from 1950 to 1970, slowing to 2.0 percent per annum from 1970 to 1990; meanwhile, for men and women aged 45–54 (for all ethnicity and races), the Human Mortality Database shows that all-cause mortality fell at 0.5 percent per annum from 1950 to 1970, but at 2.3 percent per annum from 1970 to 1990. Although the patterns of mortality vary by sex, the acceleration in mortality decline between 1950–1970 and 1970–1990 characterizes both men and women separately, and all five-year age groups from 35–39 to 55–59. But neither the slowdown in income nor the increase in inequality that accompanied it had anything to do with the acceleration in mortality decline, particularly for heart disease, which was driven by the introduction of antihy-pertensives after 1970, later aided by statins, and by a decline in smoking, particularly for men. These health improvements were common to all rich countries, albeit with some difference in timing, and were essentially independent of patterns of growth and inequality in different countries, Deaton and Paxson (2001, 2004), Cutler et al. (2006). Although we do not consider it explicitly here, the fact that inequality and mortality moved in opposite directions speaks against the hypothesis that relative income—your income rising more rapidly than mine, or the success of the top one percent—drives mortality, see also Deaton (2003).

If we accept these arguments, we are left with no explanation for the mortality turnaround. We suspect that more likely causes are various slowly moving social trends, such as the declining employment to population ratio, or the decline in marriage rates, and it is to these that we turn below. We note that it is difficult to rule out explanations that depend on long-run forces, such as the fact that those aged 50 in 2010, as opposed to those aged 70 in 2010, were much less likely to have been better off than their parents throughout their working life, Chetty et al (2016). Even so, we need to explain why stagnant incomes have this effect on whites but not on blacks. Perhaps the substantial reduction in the black/white wage gap from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s gave an enduring sense of hope to African Americans, though there has been little subsequent reason in income patterns to renew it, Bayer and Charles (2017). Many Hispanics are markedly better off than their parents or grandparents who were born abroad. Yet none of this explains why being better off than one’s parents should protect against income decline, though it is not hard to see why, after a working life at lower incomes than the previous generation, falling incomes around age 50 might be hard to deal with. (This explanation works less well for younger age cohorts, who are also bearing the brunt of this epidemic, but who are not yet old enough to know whether they will be better off than their parents during their working lives.) The historian Carol Anderson argued in an interview in Politico (2016) that for whites “if you’ve always been privileged, equality begins to look like oppression,” and contrasts the pessimism among whites with the “sense of hopefulness, that sense of what America could be, that has been driving black folks for centuries.” That hopefulness is consistent with the much lower suicide rates among blacks, but beyond that, while suggestive, it is hard to confront such accounts with the data.

III. Increasing disadvantage

III.A Background

We have seen that it is difficult to link the increasing distress in midlife to the obvious contemporaneous aggregate factors, such as income or unemployment. But some of the most convincing discussions of what has happened to working class whites emphasize a long-term process of decline, rooted in the steady deterioration in job opportunities for people with low education, see in particular Cherlin (2009, 2014). This process, which began for those leaving high school and entering the labor force after the early 1970s—the peak of working class wages, and the beginning of the end of the “blue collar aristocracy”—worsened over time, and caused, or at least was accompanied by, other changes in society that made life more difficult for less-educated people, not only in their employment opportunities, but in their marriages, and in the lives of and prospects for their children. Traditional structures of social and economic support slowly weakened; no longer was it possible for a man to follow his father and grandfather into a manufacturing job, or to join the union and start on the union ladder of wages. Marriage was no longer the only socially acceptable way to form intimate partnerships, or to rear children. People moved away from the security of legacy religions or the churches of their parents and grandparents, towards churches that emphasized seeking an identity, or replaced membership with the search for connection or economic success, Wuthnow (1990). These changes left people with less structure when they came to choose their careers, their religion, and the nature of their family lives. When such choices succeed, they are liberating; when they fail, the individual can only hold him or herself responsible. In the worst cases of failure, this is a Durkheim-like recipe for suicide. We can see this as a failure to meet early expectations or, more fundamentally, as a loss of the structures that provide a meaning to life.

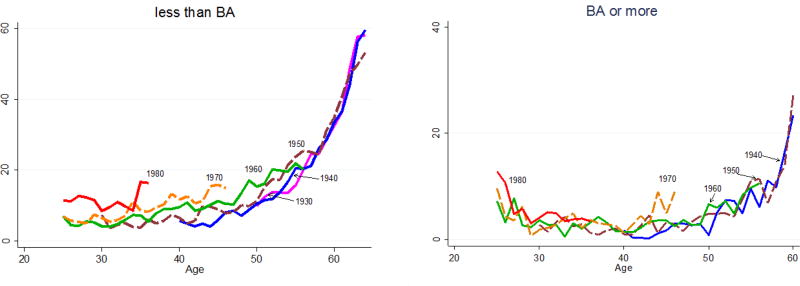

As technical change and globalization reduced the quantity and quality of opportunity in the labor market for those with no more than a high school degree, a number of things happened that have been documented in an extensive literature. Real wages of those with only a high school degree declined, and the college premium increased. More people went to college, a choice that, in practical terms, was not available to those lacking the desire, capability, resources, or an understanding of the expected monetary value of a college degree. Family incomes suffered by less than the decline in wages because women participated in the labor force in greater numbers, at least up to 2000, and worked to shore up family finances; even so, there was a loss of wellbeing at least for some. Chetty et al (2016) estimate that only 60 percent of the cohort born in 1960 was better off in 1990 than had been their parents at age 30. They estimate that, for those born in 1940, 90 percent were better off at 30 than their parents had been at the same age. The data do not permit an analysis, but the deterioration was likely worse for whites than blacks, and for those with no more than a high school degree. As the labor market worsens, some people switch to lower paying jobs—service jobs instead of factory jobs—and some withdraw from the labor market. Figure 3.1 shows that, after the birth cohort of 1940, in each successive birth cohort, men with less than a four-year college degree were less and less likely to participate in the labor force at any given age—a phenomenon that did not occur among men with a BA.

Figure 3.1.

Percent not in the labor force, white non-Hispanic men by birth cohort and education

It is worth noting again that the fractions with and without a BA are constant for the cohorts born between 1945 and 1965, then rise from 30 to 40 percent for cohorts born between 1965 and 1970, beyond which the fraction remains stable at 40 percent. In consequence, some of the deterioration in outcomes for the less-educated cohorts born between 1965 and 1970 may be driven by a decrease in their average positive characteristics; for example, if education is selected on ability, there will be a decrease in average ability in the group without a 4-year degree. Yet this cannot be the whole story. Deterioration started for cohorts born in the 1940s and increased gradually with each birth cohort that followed. Moreover, if lower ability people are transferred from the less to the more educated group, outcomes should also deteriorate for the latter; this is the Will Rogers effect—that moving the most able upwards from the bottom group brings down the averages in both bottom and top groups. Yet the cohort graphs show no evidence of deterioration among those with a BA. Qualitatively, the same picture is seen when the education groups are pooled, providing an attenuated version of the left panel of Figure 3.1 (Appendix Figure 9).

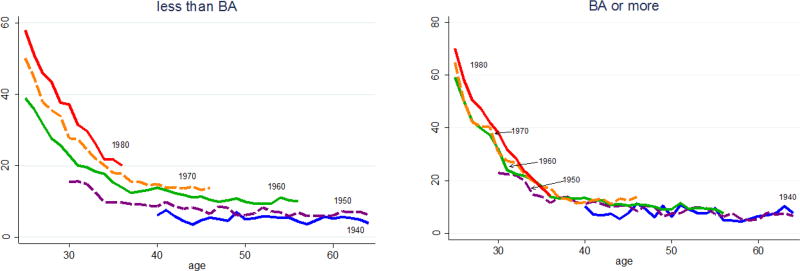

Lower wages not only brought withdrawal from the labor force, but also made men less marriageable; marriage rates declined, and there was a marked rise in cohabitation, which was much less frowned upon than had been the case a generation before. Figure 3.2 shows that, after the cohort of 1945, men and women with less than a BA degree are less likely to have ever been married at any given age. Again, this is not occurring among those with a four-year degree. Unmarried cohabiting partnerships are less stable than marriages. Moreover, among those who do marry, those without a college degree are also much more likely to divorce than are those with a degree. The instability of cohabiting partnerships is indeed their raison d’être, especially for the women, who preserve the option of trading up, see also Autor, Dorn and Hansen (2017)—so that both men and women lose the security of the stable marriages that were the standard among their parents. Childbearing is common in cohabiting unions, and again is less disapproved of than once was the case. But, as a result, more men lose regular contact with their children, which is bad for them, and bad for the children, many of whom live with several men in childhood. Some of a woman’s partners may be unsuitable as fathers, and those who are suitable bring renewed loss to children when it is their turn to depart. Importantly, this behavior is more common among white women than among Hispanics or African Americans; the latter have more out of wedlock children, but have fewer cohabiting partners, see again Cherlin (2009). In Europe, cohabitation is also common, but is much less unstable, and not so different from marriage. Cherlin (2014) notes that it is now unusual for white American mothers without a college degree not to have a child outside of marriage. The repeated re-partnering in the US is often driven by the need for an additional income, something that is less true in Europe with its more extensive safety net, especially of transfer income; Britain, for example, provides unconditional child allowances that are attached to children.

Figure 3.2.

Percent of birth cohorts never married, white non-Hispanic men and women

Social upheaval may have taken different forms, on average, for African Americans. Black kin networks, though often looser, may be more extensive and more protective, as when grandmothers care for children. Black churches provide a traditional and continuing source of support. As has often been noted, blacks are no strangers to labor market deprivations, and may be more inured to the insults of the market.

These accounts share much, though not all, with Murray’s (2012) account of decline among whites in his fictional “Fishtown.” Murray argues that traditional American virtues are being lost among working-class white Americans, especially the virtue of industrious-ness. In this argument, the withdrawal of men from the labor force reflects this loss of in-dustriousness; young men in particular prefer leisure—which is now more valuable because of video games, Aguiar et al (2016)—though much of the withdrawal of young men is for education, Krueger (2016). The loss of virtue is supported and financed by government payments, particularly disability payments, see also Eberstadt (2016). If this malaise is responsible for the mortality and morbidity epidemic, it is unclear why we do not see rising mortality rates for blacks, for Hispanics, for more educated whites, or indeed for Europeans, although the last group has universal health care and a much more generous safety net. Indeed, in some European countries, disability programs are so generous and so widely claimed that average retirement ages are below the minimal legal retirement age, see Gruber and Wise (2007).

According to Krueger, half of the men who are out of the labor force are taking pain medication, and two thirds of those take prescription painkiller, such as opioids. Eberstadt (2017) notes that, in many cases, opioids are paid for by Medicaid, so that “`dependence on government’ has thus come to take on an entirely new meaning.” Yet it is not only the government that is complicit. Doctors bear responsibility for their willingness to (over) prescribe drugs (Quinones (2015), Barnett et al (2017)), especially when they have little idea of how to cure addiction if and when it occurs. There are also reasonable questions about an FDA approval system that licenses a class of drugs that has killed around 200,000 people. We should note that a central beneficiary of the opioids are the pharmaceutical companies who have promoted their sales. According to Ryan, Girion, and Glover (2016), Purdue Pharmaceutical had earned $31 billion from sales of OxyContin as of mid-2016.

In our account here, we emphasize the labor market, globalization and technical change as the fundamental forces, and put less focus on any loss of virtue, though we certainly accept that the latter could be a consequence of the former. Virtue is easier to maintain when it is rewarded. Yet there is surely general agreement on the roles played by changing beliefs and attitudes, particularly the acceptance of cohabitation, and of the rearing of children in unstable cohabiting unions.

These slow-acting social forces seem to us to be plausible candidates to explain rising morbidity and mortality, particularly suicide, and the other deaths of despair, which share much with suicides. As we have emphasized elsewhere, Case and Deaton (2017), purely economic accounts of suicide have rarely been successful in explaining the phenomenon. If they work at all, they work through their effects on family, on spiritual fulfillment, and on how people perceive meaning and satisfaction in their lives in a way that goes beyond material success. At the same time, increasing distress, and the failure of life to turn out as expected is consistent with people compensating through other risky behaviors such as abuse of alcohol and drug use that predispose towards the outcomes we have been discussing.

III.B A framework to interpret the data

A simple way of taking these stories to our data is to suppose that there is a factor that each birth cohort experiences as it enters the labor market. This might be the real wage at the time of entering, but it could be a range of other economic and social factors, including the general health of the birth cohort (Case et al. 2005); we deliberately treat this as a latent variable that we do not specify. This is related to accounts in which workers enter the labor market in a large birth cohort, or in bad times (see Hershbein 2012 and references provided there). However, it is different in that we emphasize the experience of all cohorts who entered the labor market after the early 1970s, and we focus on a secular deterioration in this initial condition.

We label birth cohorts by the year in which they are born, b, say, and assume each experiences Xb as they enter the labor market, which then characterizes their labor market for the rest of their lives. Because of the factors outlined above, we might expect the effects to accumulate over time, but in this initial stage of the research we assume the disadvantage is constant for those in birth cohort b during their adult lives; we measure the factor as a disadvantage, which is natural for mortality, but requires reversing signs when we look at earnings. The driving variable X is itself trending over time, though not necessarily linearly; our measurement will allow for any pattern. In this set up, various measures of deprivation—pain, mental distress, lack of attachment to the labor market, not marrying, suicide, addiction—will together move higher or lower as the initial condition Xb goes up or down for later born cohorts.

Figure 1.7, which inspired this way of thinking about the data, shows how this works for deaths of despair, collectively, and for suicides, poisonings, and alcoholism separately, and Figures 1.12, 1.13, 3.1 and 3.2 show the corresponding graphs for self-reported health, pain, labor force participation and marriage respectively. For morbidity and mortality we see an upward slope with age, which will be captured by a flexible age effect, with the age profile higher for each successive cohort, which we explain as an increase in the starting variable Xb. In this first analysis, we make no attempt to model the rotation of the age profiles that are apparent for some cohorts in several of these figures.

Our model for each outcome is then written as

| (1) |

where i indexes an outcome—suicide, pain, marriage outcomes; b is the birth year, and a is age. Each outcome is a function of age, shared by all birth cohorts for a given outcome, which will be estimated non-parametrically; θi is the parameter that links the unobservable common factor Xb to each outcome i. The unobservable factor itself is common across outcomes. From the data underlying Figure 1.7, 1.12, 1.13, 3.1, and 3.2, as well as for other conditions, we can estimate (1) by regressing each outcome on a complete set of age indicators and a complete set of year-of-birth indicators. We assume that the underlying cause of despair appeared after the 1940 birth cohort entered the market; we take this to be our first cohort, and normalize the driving variable X to zero for that cohort, for all outcomes. The coefficient on the birth cohort indicator for cohort b is an estimate of θXb. Plotting these estimates against b for each condition, we should see the latent cohort factor Xh, and we should see the same pattern, up to scale, for every outcome.

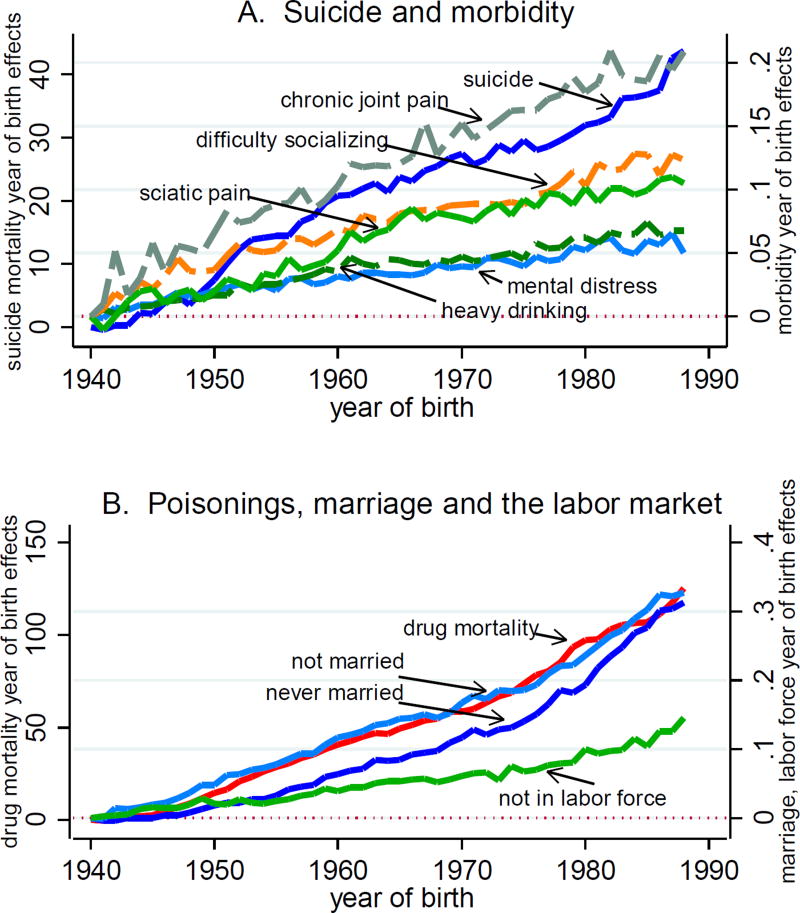

Figure 3.3 shows the results for each birth cohort born between 1940 and 1988, for white non-Hispanics aged 25 to 64, without a BA. The top panel presents estimates θiXb for suicide (marked by the solid blue line), with its scale on the left; the scale for chronic pain, sciatic pain, mental distress, difficulty socializing and heavy drinking is given on the right. (Obesity also shows a linear trend in year of birth effects. However, its scale is much larger, and its inclusion obscures detail of other morbidity measures.)

Figure 3.3.

Mortality, morbidity and labor force participation

The bottom panel of Figure 3.3 presents estimates for drug and alcohol poisoning (marked by the solid red line), marriage (both never married, and not currently married) and, for males, not being in the labor force. We do not include alcoholic liver disease in this part of the analysis; the lag between behavior (heavy drinking) and mortality (cirrhosis, alcoholic-liver disease) does not allow us to see the difference in mortality consequences of heavy drinking between birth cohorts currently under the age of 50.

In the top panel, the slopes formed by plotting θiXb estimates are approximately linear for each outcome, consistent with a model in which the latent variable has increased, and increased linearly between birth cohorts. For these conditions, we see that we can match the data by a common latent factor that increases linearly from one cohort to the next.

In the bottom panel, for drug overdose, marriage, and labor force detachment, we see a somewhat different pattern, in which the common latent variable is “worse” than linear, with a slope that is increasing more rapidly for cohorts born after 1970 than for those born before. This is consistent with either a non-linear effect of disadvantage on these outcomes, or the addition of a second latent factor that makes its appearance for cohorts born around and after 1970, who would have entered the market starting in the early 1990s. As was true for suicide, pain and isolation, each successive cohort is at higher risk of poor outcomes than the cohort it succeeded.

Note that there is nothing in our procedures that ensures that the plots in Figure 3.3 must rise linearly, or even monotonically. That they do so is suggestive of an underlying factor at work, which may drive all of these outcomes.

In a statistically inefficient but straightforward method, we can recover estimates of Xb, by pooling across conditions and regressing the logarithms of the estimated θiXb coefficients on indicators for each cohort and each condition. Results confirm a nearly linear increase in X across birth cohorts for suicide, heavy drinking, pain and isolation and a nonlinear increase for drug overdose, labor market attachment, and marriage.

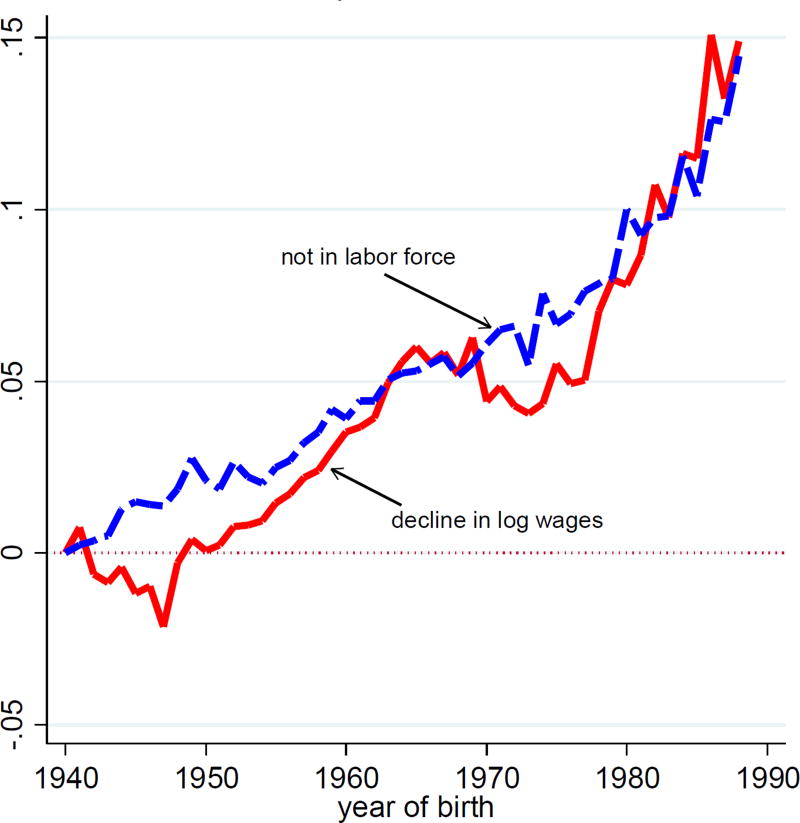

One might reasonably ask what is causing what in our analysis. The use of a latent variable model allows us to avoid taking a position on the question. That said, we turn to the progressive deterioration of real wages as a possible driving variable. Figure 3.4 plots the (negative of) θiXb coefficients from a regression of log real wages for men with less than a four-year college degree against coefficients from a regression of the percent of men, with less than a BA, not in the labor force.

Figure 3.4.

Log wages and labor force participation white non-Hispanic men, less than BA

The cohorts born between 1940 and 1988 show a decline in real wages that has become more pronounced with each successive birth cohort. This temporal decline matches the decline in attachment to the labor force. Here we also emphasize cascading effects on marriage, health, and morbidity and, ultimately, deaths of despair.

Comparison figures for those with a BA are provided in Appendix Figure 10, where figures have been drawn on the same scales used in Figure 3.3. Aside from being at risk for heavy drinking, which shows a pattern similar to those without a BA, those with a BA have seen much more limited changes in health, mental health, and marriage outcomes (with reports of pain, mental distress and difficulty socializing between zero and 2.5 percentage points higher in the birth cohort of 1980 relative to 1940), and flat profiles for labor force participation, suicide and drug mortality. Controlling for age, real wages for those with a BA are on average 10 percent higher for the cohort born in 1980 relative to the cohort of 1940 (results not shown), while wages for those without a BA are 10 percent lower (Figure 3.3B).