Abstract

Background

In this paper, we propose a new method, named the intervals’ method, to analyse data from finite element models in a comparative multivariate framework. As a case study, several armadillo mandibles are analysed, showing that the proposed method is useful to distinguish and characterise biomechanical differences related to diet/ecomorphology.

Methods

The intervals’ method consists of generating a set of variables, each one defined by an interval of stress values. Each variable is expressed as a percentage of the area of the mandible occupied by those stress values. Afterwards these newly generated variables can be analysed using multivariate methods.

Results

Applying this novel method to the biological case study of whether armadillo mandibles differ according to dietary groups, we show that the intervals’ method is a powerful tool to characterize biomechanical performance and how this relates to different diets. This allows us to positively discriminate between specialist and generalist species.

Discussion

We show that the proposed approach is a useful methodology not affected by the characteristics of the finite element mesh. Additionally, the positive discriminating results obtained when analysing a difficult case study suggest that the proposed method could be a very useful tool for comparative studies in finite element analysis using multivariate statistical approaches.

Keywords: Biomechanics, Finite element analysis, Cingulata, Armadillos, Chewing mechanics, Multivariate analysis

Introduction

The introduction of virtual models applied to biological structures represents an important advance for comparative biological studies achieved during the last few years (see review in Bright, 2014). In computational biomechanics, FEA has become increasingly popular among researchers due to its ability to show the biomechanical behaviour of anatomical structures, and is especially useful for analysing species where experimental approaches are not suitable (Gunz et al., 2009; Pierce, Angielczyk & Rayfield, 2009; Degrange et al., 2010; Fletcher, Janis & Rayfield, 2010; Fortuny et al., 2011; Fortuny et al., 2015; Fortuny et al., 2016; Attard et al., 2016; Figueirido et al., 2014). FEA is a technique that acts by dividing a structure into a finite number (normally thousands or millions) of discrete elements with well-known mathematical properties (e.g., triangles, tetrahedrons or cubes). If the geometry of an object is simple enough, strain and stress can be solved by applying analytical solutions. However, more complex shapes (such as the ones observed in most biological cases) might be difficult or even impossible to solve using analytical means, especially if the loading scenarios or material properties are complex. Therefore, FEA offers an alternative approach by approximating the solution via the subdivision of complex geometries into multiple finite elements of simpler geometry. After virtually applying forces to the structure under analysis the stress (and strain) produced by those loads is computed in each one of these small elements.

The results obtained using FEA are commonly expressed as colour maps where warmer colours (i.e., orange, red) represent high levels of stress, whilst colder colours (i.e., blue) correspond to lower levels. These FEA-derived colour maps have proven to be very useful in biological contexts, especially when the main aim of a study is to detect which regions of a particular structure are most affected by the applied loads (Rayfield, 2004).

In spite of the usefulness of these colour maps (e.g., it is possible to define the most fragile area of a structure by visual inspection), they do not easily allow a quantitative performance comparison between similar structures. Comparative approaches in functional morphology focus on elucidating the differences between species (or another taxonomic level) for the same anatomical structure (Neenan et al., 2014). Therefore, their main aim is to test which species are better prepared to bear equivalent loads instead of actually knowing the specific amount of stress/strain that would break the structure under analysis (Lautenschlager, 2017). Researchers are usually looking for the connection between the observed amount of stress in the analysed taxa and some ecologically relevant variable.

When the taxonomic level is not very high (e.g., at the genus or family level), the structure (e.g., a specific bone) is usually quite similar, thus making the visual inspection of the colour maps more difficult or even not conclusive at all (Serrano-Fochs et al., 2015). Usually researchers interpret the colour maps visually and translate that qualitatively (species more “bluish” have less stress than those more “reddish”). Although these descriptions might be useful to provide an overall summary of the results, they are highly subjective and imprecise which makes them problematic to report differences (Dumont et al., 2011).

This problem has been tackled by researchers in the last few years by applying different approaches in order to obtain quantitative data that can be later used to compare different species and to test hypotheses in comparative contexts. One possible approach is to compute the mean of the von Mises stress values of different taxa and then compare them (McHenry et al., 2007; Farke, 2008; Aquilina et al., 2013; Figueirido et al., 2014; Neenan et al., 2014; Fish & Stayton, 2014; Lautenschlager, 2017). However, as described in Bright & Rayfield (2011), Tseng & Flynn (2014), Marcé-Nogué et al. (2015b), Marcé-Nogué et al. (2016) this approach has the problem that part of the observed variation can be produced by the differences in the size of the elements of the finite element meshes representing each taxon. Therefore, some correction is required when computing the mean of the von Mises stress values. For instance, Marcé-Nogué et al. (2016) proposed a method that weights the stress values by the size of the element in order to obtain corrected mean values. Another possible approach is to use box-plots or other visual ways of representing distributions (e.g., histograms) to compare in a general manner whether one taxon shows more stress than another one (Farke, 2008; Figueirido et al., 2014; Fortuny, Marcé-Nogué & Konietzko-Meier, 2017). Finally, another proposed solution is to collect von Misses stress values at specific points or slices to compare the biomechanical performance between different species (Piras et al., 2015; Serrano-Fochs et al., 2015; Püschel & Sellers, 2016; Attard et al., 2016).

Despite the usefulness of all the above-mentioned approaches, they are still only gross measurements that do not make the most of the results obtained from FEA. There is still a need for a quantitative meaningful output from FEA that could be used in multivariate statistical analyses, since most applied multivariate approaches (Marcé-Nogué et al., 2015a; Fortuny et al., 2016) only analyse stress values collected from a limited number of points. Therefore, the main aim of this work is to present a new approach, which we have named the interval’s method, which allows the quantitative comparison of FEA results from different specimens in a multivariate statistical framework.

The second objective of this work is to check whether the proposed intervals method is useful when testing biologically meaningful hypotheses using real data. The proposed method was applied to compare the stress results obtained from several planar models of armadillo mandibles to test the hypothesis that there are significant differences in biomechanical performance (measured as stress values) between different dietary categories.

Material and Methods

FEA models

Plane models of 11 mandibles of Cingulata (Table 1), each one corresponding to a different species, were created according to the methodology summarized by Fortuny et al. (2012). The models were created using the ANSYS FEA Package (Ansys Inc.) v.15 for Windows 7 (64-bit system) to obtain the von Mises stress distribution.

Table 1. List of the species analysed in the present study.

The classification of each species was made on the basis of the current knowledge about the ecology of armadillos, mainly based on stomachs contents (Soibelzon et al., 2007; Redford, 1985; Redford & Wetzel, 1985; Sikes, Heidt & Elrod, 1990; Bolkovi, Caziani & Protomastro, 1995; Smith, 2008; Da Silveira Anacleto, 2007; Superina et al., 2009; Abba et al., 2011; Loughry & McDonough, 2013; Borghi et al., 2011; Superina, Pagnutti & Abba, 2014; Dalponte & Tavares-Filho, 2004; Hayssen, 2014; McBee & Baker, 1982). The geometric properties and the applied forces at the Masseter and Temporalis muscles are also provided. Abbreviations preceding the names of institutions are used to identify the location were the specimens are housed. AMNH, American Museum of Natural History, New York, USA; MNCN, Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Madrid, Spain; MNHN, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturalle, Paris, France; ZMB, Zoologisches Museum, Berlin, Germany; MLP, Museo de la Plata, La Plata, Argentina.

| Taxon | Diet | Collection number | Thickness (mm) | Model area (mm2) | Masseter area (mm2) | Temporalis area (mm2) | Masseter force (N) | Temporalis force (N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Priodontes maximus | Specialist insectivore | AMNH 208104 | 6.41 | 2051.70 | 616.02 | 255.06 | 1.29 | 0.53 |

| Cabassous unicinctus | Specialist insectivore | MNHN 1953/457 | 3.51 | 415.75 | 112.08 | 22.91 | 0.37 | 0.08 |

| Tolypeutes matacus | Generalist insectivore | AMNH 246460 | 3.56 | 497.40 | 157.01 | 64116.00 | 0.35 | 0.14 |

| Dasypus kappleri | Generalist insectivore | MNHN 1995/207 | 3.51 | 971.37 | 105.37 | 153.18 | 0.28 | 0.41 |

| Dasypus sabanicola | Generalist insectivore | ZMB_Mam_85899 | 2.78 | 527.86 | 150.66 | 71545.00 | 0.27 | 0.13 |

| Dasypus novemcinctus | Generalist insectivore | AMNH 133338 | 2.94 | 613.54 | 225.77 | 92174.00 | 0.32 | 0.13 |

| Chlamyphorus truncatus | Generalist insectivore- fossorial | ZMB_Mam_321 | 2.00 | 113.19 | 16035.00 | 34006.00 | 0.04 | 0.09 |

| Chaetophractus villosus | Omnivore/ Carnivore | MNCN 2538 | 4.94 | 1038.90 | 300.58 | 156.08 | 0.66 | 0.34 |

| Chaetophractus vellerosus | Omnivore/ Carnivore | MLP 18.XI.99.9 | 3.68 | 538.80 | 145.04 | 117.03 | 0.30 | 0.24 |

| Euphractus sexcinctus | Omnivore/ Carnivore | MNHN 1917/13 | 5.66 | 1019.20 | 331.22 | 190.60 | 0.72 | 0.41 |

| Zaedyus pichiy | Omnivore/ Carnivore | MLP 9.XII.2.10 | 3.51 | 327.35 | 89737.00 | 66091.00 | 0.23 | 0.17 |

Two main masticatory muscles (i.e., temporalis and masseter) were included in the model as a vector between the centroid of the muscular attachment in the mandible and the centroid of the equivalent muscle attachment in the skull following the modelling approach used in Serrano-Fochs et al. (2015). To compare the models, a scaling of the values of the forces was applied according to a quasi-homothetic transformation in the FEA models (Marcé-Nogué et al., 2013) using the plane model of Chaetophractus villosus as a reference. This method corresponds to an adaptation of the scaling methods proposed by Wroe, McHenry & Thomason (2005) and Dumont, Grosse & Slater (2009) for plane models. This procedure was performed to apply the appropriate force in each model, thus allowing the comparison of the stress results when the specimens differ in size.

The information for each analysed species regarding the area of the mandible, insertion areas, forces (musculature applied force per unit area (N/mm2)), thickness and the scale factor in the quasi-homothetic transformation can be found in Table 1.

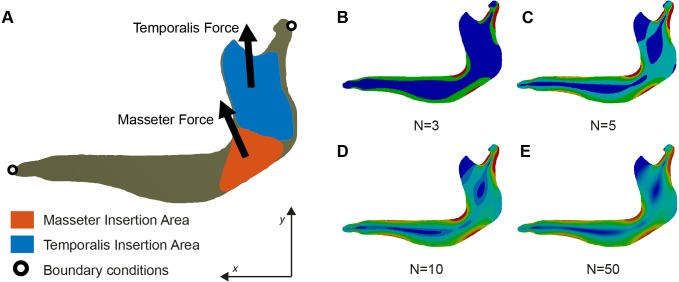

The boundary conditions were defined and placed to represent the loads, displacements, and constraining anchors that the structure (i.e., mandible) experiences during its function. The mandible was constrained in the x and y direction at the most anterior part and fixed in the x and y directions on the condyle at the level of the mandibular notch (Fig. 1) following the procedures described in Serrano-Fochs et al. (2015) and Marcé-Nogué et al. (2016).

Figure 1. (A) Free-Body diagram of the Biomechanical problem and (B–E) representation of von Mises stress distribution in a mandible of Chlamyphorus truncatus with different number of intervals (N) under the same boundary conditions.

Isotropic and linear elastic properties were assumed for the bone. In the absence of data for Cingulata or any other closer relative, as well as lacking data for any mammalian clade with a similarly shaped jaw, we decided to apply the mandibular material properties of Macaca rhesus: E (Elasticity Modulus) = 21,000 MPa and v (Poisson coefficient) = 0.45 (Dechow & Hylander, 2000). We chose the available properties of Macaca rhesus because it has a wide range of habitats and diet which resembles omnivorous or generalist insectivorous armadillos (Richard, Goldstein & Dewar, 1989). In addition, it has been shown that in a comparative analysis these values are not crucial (See Gil, Marcé-Nogué & Sánchez, 2015 for discussion).

As primary data, we obtained the von Mises stress distribution of each one of the analysed species. Von Mises stress is an isotropic criterion used to predict the yielding of ductile materials determining an equivalent state of stress (Reddy, 2008). Considering bone as a ductile material (Dumont, Grosse & Slater, 2009) and according to Doblaré, García & Gómez (2004) when isotropic material properties are defined in cortical bone, the von Mises criterion is the most adequate for comparing stress states.

Quantitative stress data

Von Mises stress values were obtained for all the elements of each finite element model. Values of stress (and strain) can be obtained for each element because FEA mathematically solves stress (and strain) inside each element, while displacements are computed at the nodes (Zienkiewicz, Taylor & Zhu, 2013). ANSYS provides a complete data file with these results that can be easily manipulated in spreadsheets and other software. This means that the number of stress data points for each mandible is the same as the number of elements of the mesh.

The new methodology proposed here divides the values of stress into N equal intervals (Fig. 1). Therefore, each interval will contain all the elements within a certain threshold, each one being defined by a lower threshold Tlower and an upper threshold Tupper. The range of the intervals is constant across the sample, the distance from Tlower to Tupper being the same in all the intervals. For an interval Φi the lower threshold coincides with the upper threshold of the interval Φi−1 and the upper threshold coincides with the lower threshold of the interval Φi+1.

Once all the stress values of a single specimen were obtained they were subdivided into different intervals. When all the elements of this specimen were allocated into an interval, the total number of elements in each interval EΦi (Eq. (1)) was computed and the total area of each interval AΦi (Eq. (2)) was calculated from the individual area of each element. These values must fulfil the Eqs. (1) and (2). Then, the percentage area of each interval was computed in relation with the total area of the model for each specimen, following the Eq. (3).

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

After carrying out this procedure, a new set of variables was generated (AΦ [%]), each one representing a different interval of stress values. Each variable represents the amount of area (as a percentage) of the original model having this range of stress values. If this procedure is performed in several models, these new variables can be used in later analyses comparing the different models.

A Fixed Upper Threshold FTupper has to be defined in the interval ΦN−1 to allow including in the interval ΦN all the highest values of stress. Some of these high values of stress represent artificial noise, which are numerical singularities produced in the results of FEA at the points where the displacement boundary conditions are applied (Marcé-Nogué et al., 2015b). The presence of this artificial noise in a numerical model is due to the mesh, since as the elements get smaller, the artificial high stress values become even higher (Dumont, Grosse & Slater, 2009). To select the FTupper we chose not to consider the maximum value of 2% of the higher values of the model based in the suggestions of Walmsley et al. (2013) and Marcé-Nogué et al. (2016).

Convergence of the data for the case study

To enable the comparison between different species it is necessary to specify the number of intervals that will be applied to the specimens under analysis, since this number will define the number of variables (A[%]). A large number of intervals will generate an excessive number of variables to work with, which can be difficult to interpret in later analyses. On the other hand, a limited number of intervals may yield incorrect results as they could oversimplify the stress pattern. Therefore, we decided to carry out multiple Principal Components Analyses (PCAs) as a guide to choose the minimum number of the intervals.

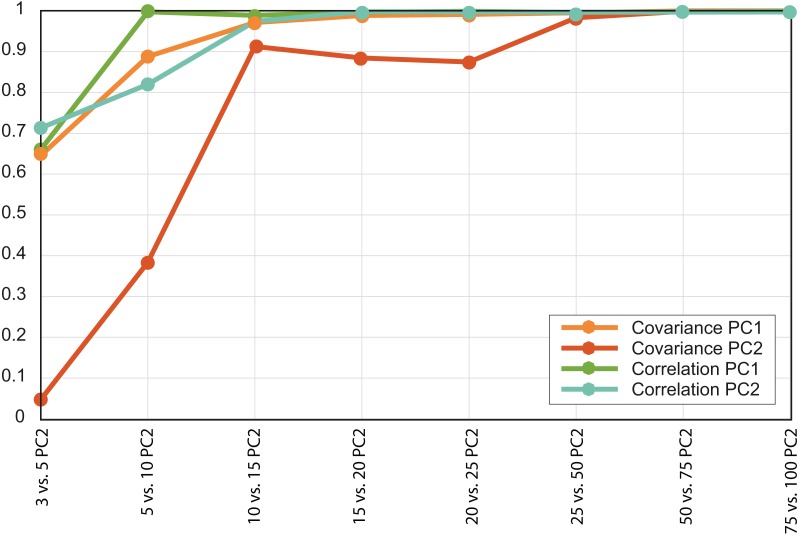

We performed these PCAs based on a different number of intervals to establish the threshold in which the data converged (i.e., when adding more intervals yielded similar patterns in the PCAs). We named this threshold value NPCA.

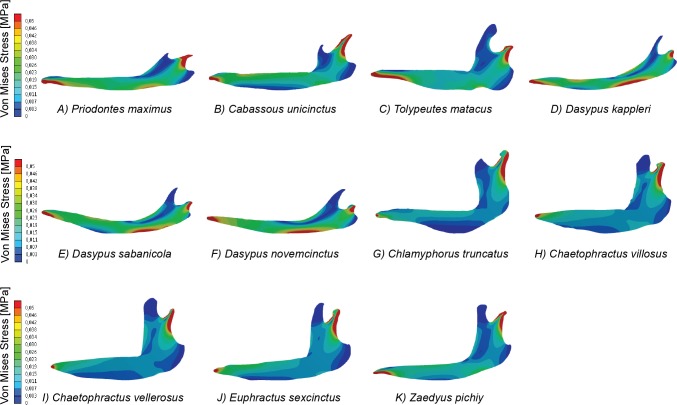

For the 11 mandible models of our case study (Fig. 2), the PCAs were performed using nine different sets of intervals: N = 3, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 50, 75 and 100. In this case the FTupper was fixed to 0.1 MPa, which represents the appropriate value where less than the 2% of the higher values for all the eleven models are in its interval ΦN. Once all the PCAs were carried out we performed Major Axis Linear regressions between equivalent PC scores of one set of intervals and the next one (e.g., regression between the PC1 scores of the PCA of 3 intervals with PC1 scores of the PCA of 5 intervals). The coefficient of determination (R2) was then used to assess the convergence of the obtained results (Document S5). For each PC (1, 2 and 3 only, as they represent more than 80% of the variance for all the cases) we computed the coefficient of determination for successive pairs of PCs. The number of intervals at which R2 reached a plateau (i.e., it does not further increase) was considered the NPCA.

Figure 2. Map of von Mises stress distribution in the eleven FEA models of armadillo mandibles.

When the variables are all in the same units, it is usually preferred to carry out the PCA on the variance–covariance matrix. Since our variables were in the same units, we performed the aforementioned PCAs using the variance–covariance matrix. Nevertheless, if some variables, despite being in the same units, have a noticeably larger variance than others they will have a higher weight on the PCA, which might obscure more subtle relationships between those variables. In these kind of situations PCAs using the correlation matrix are more adequate (i.e., this is equivalent to perform the PCA using standardized variables). In the context of the present study this is relevant, since areas with high stress are usually small in all specimens. This implies that the variance for this specific interval (which represents one of the variables used to perform the PCA) will be small compared to the variance of an interval representing lower stress values, which occupy very large areas. Since the interval representing higher stresses could be still informative in comparative terms between species, it is important to account for this situation. By performing the PCA on the correlation matrix, a variable that has a smaller variance in absolute terms can be informative in relative terms. For this reason, in the case study we carried out PCAs using both kinds of variable matrices (i.e., variance–covariance and correlation).

Results

Validation of the data for statistical analyses

Document S4 show the percentage of area for each interval AΦ[%] using different N intervals, as well as the variance loadings for the PCAs.

Based on the patterns observed in the plots displaying the first two PCs (Fig. 3) for each set of intervals it is clear that the distribution in stress space became more or less the same after N = 50. Additionally, the results of the regressions of the PCs indicate that the scores are almost completely correlated for N = 50 (Fig. 4 and Document S5), therefore we chose to compare the different species with the set of 50 intervals (i.e., NPCA).

Figure 3. Plots displaying the first two PCs of the different PCAs for N = 3, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 50, 75 and 100.

The species are coloured by subfamily: blue: Tolypeutinae, green: Euphractinae, red and pink: Dasyponinae, yellow: Clamyphorinae. The axes of each pair of PCs are in the same scale.

Figure 4. Convergence of the R2 values of the PC scores.

Each value is the R2 for a different pair of PCAs, both the variance-covariance matrix based PCA (orange lines) and the correlation-matrix based PCAs (green lines). Each PC was correlated with the equivalent PC of the PCA developed using a larger number of intervals.

Case study

Using a NPCA = 50, the PCA developed on the covariance matrix showed more than 90% of the variance concentrated in the first PC, while using the correlation matrix the first PC explained only 75.4% of the variance.

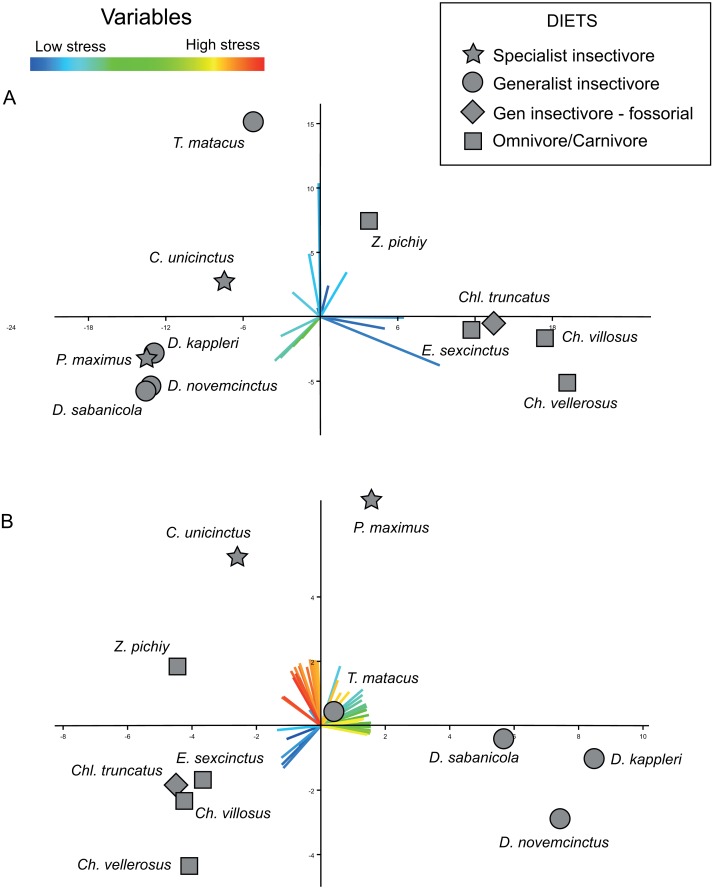

The bi-plot of stress space defined for the first two PCs of the PCA performed on the variance–covariance matrix allow to identify different areas (Fig. 5A). The right side of this bi-plot (Fig. 5A) is occupied by species that can be described as having a very large area of a specific range of values (i.e., low to very low stress), whilst downwards on the left of this stress space are specimens characterized by moderate stress values. Finally, the upper left part of this stress space is exclusively occupied by individuals showing values intermediate between the former ones. Based on the loadings of the variables, is evident that the proportionally larger areas with low stress dominate this PCA (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. Plots displaying the two kinds of PCAs performed.

(A) PCA based on the variance-covariance matrix. (B) PCA based on the correlation matrix. The loadings for each variable are coloured according with the range of stress they represent, with reddish colours for high level of stress, and bluish for low levels. X-axis: PC1. Y-axis: PC2.

The results obtained from this PCA make it possible to establish certain patterns. A proportionally larger area of intermediate stresses characterizes the insectivores, while proportionally larger areas with very low stress values characterize the omnivores (Fig. 5A). However, within this trend two species showed a distinct pattern in PC2: T. matacus and Z. pichiy. Both are located in the upper part of the plot (Fig. 5A), characterized mainly by one specific value of low stress area. Nonetheless, the second PC only explains 16.8% of the variance.

According to a hypothesis suggested in Serrano-Fochs et al. (2015), high levels of stress along the mandible would represent a fragile mandible with a reduced capability to chew or process hard items. Supporting this hypothesis, in the present case the insectivores are in the left part of the stress space, defined by intermediate to low stress levels. This can be expected considering that these species feed mainly on ants without chewing them; thus their mandibles are expected to show a higher stress level. On the other hand, very low stress values would be indicative of mandible with a higher ability to bear higher loads. This would be in agreement with the location of the omnivorous taxa at the right side of the stress space characterized by intermediate stress values (E. sexcintus, Ch. villosus, Ch. vellerosus and Z. pichiy, Fig. 5A).

Nevertheless, this PCA did not detect any difference in the stress pattern between specialist and generalist insectivores. All the loadings for the first two PCs belong to low or intermediate stress values, whilst the loadings of the variables representing intermediate to high stress have almost negligible values. This arises because the percentage of areas with high values is small in all analysed mandibles (the variables representing intermediate and high stresses have very small loadings for PC1 and PC2). Since we carried out the PCA using the variance–covariance matrix, the larger absolute values of the lower stress areas implied larger variance for those variables, thus completely masking the variability that might exists in the variables representing high stress values.

In the case of the PCA using the correlation matrix the distribution of the loadings of the variables (Fig. 5B) is noticeably more homogeneous (more variables have an important contribution to the PCs analysed) without being so strongly influenced by just a few specific variables as was the case of the PCA performed using the variance–covariance matrix (where variables representing low stress values overcome the rest of the variance). The PCA of the correlation matrix successfully distinguishes the main three diets, with omnivore-carnivore species on lower-left area of the plot. PC2 separates specialist insectivores from the rest of species, while Chlamyphorus truncatus (i.e., a generalist insectivorous species exhibiting a very particular diet due to its completely fossorial life style) is located near the omnivore/carnivore species in the negative part of PC1 and PC2.

Within this PCA, omnivore/carnivore species were characterized by very low stress values (lower-left quadrant of the plot), whilst generalist insectivores showed a proportionally larger area of intermediate stress values than the rest of the species. Specialist insectivores have proportionally larger areas of high stress.

As was the case when performing the PCA using the variance–covariance matrix, the fossorial generalist insectivore—Chlamyphorus truncatus was located with the omnivores. In spite of the fact that insects correspond to large part of its diet, this species also feeds on worms, snails, and a small proportion of roots (Borghi et al., 2011). This consumption of relatively harder objects that need more oral processing than just tiny insects, might explain the biomechanical results obtained here.

As similarly found by the variance–covariance PCA, Z. pichiy corresponds to the omnivorous species with proportionally less area of low stress. This species is considered to show a preference for soft-bodied species (e.g., larvae, tarantula spiders, pods) (Redford, 1985), thus being the least carnivorous taxon among all the omnivore/carnivore armadillos (Superina, Pagnutti & Abba, 2014). Indeed, microwear studies classified Z. pichiy together with the insectivorous species (Green, 2009). In concordance with this information, our results show that Z. pichiy is located in the areas of the stress space between carnivore and insectivore species. Finally, it has been suggested that T. matacus has a seasonal diet based on fruits and pods representing more than 50% of its consumed items during the dry season (Bolkovi, Caziani & Protomastro, 1995), being the the generalist insectivores species showing the lowest stress.

Discussion

Influence of the mesh in the results

The methodology presented in this work is based on obtaining the percentage areas containing certain values of stress. To validate the results, the influence of coarse meshes and non-homogeneous meshes on the computed areas was also tested in the Supplementary Information, where methods and results are discussed (Document S1).

According to the results obtained (Figs. S5A and S5B and Tables S1 and S2, our proposed approach is not affected by the size of the elements (i.e., we obtained extremely low values of the relative error ()). In addition, when the homogeneity of the mesh was tested, the absolute error (AErrj) and its variance showed very low values as well Figs. S5C and S5D and Tables S3 and S4, hence confirming that the homogeneity of the mesh is not affecting the newly generated variables.

Overall, this means that under our proposed methodology the size and the homogeneity of the mesh do not affect the obtained results, thus providing a robust method that is effective irrespective of these factors. Therefore, it is not necessary to apply mesh correction techniques such as generating a Quasi-Ideal Mesh (QIM) as proposed by Marcé-Nogué et al. (2016).

Convergence of the data in the case study; which N is adequate?

There were important differences between the PCAs depending on the N value. When this value was low (i.e., N = 3 and 5) the obtained results were noticeably different, whereas from N = 15 and above the PCA results were very similar, as shown by the dispersion plots of the first and second PCs (Fig. 4).

In the case study, the PCA convergence was NPCA = 50. This means that at least for structures such as armadillo jaws, 50 intervals are enough to describe the sample variability in terms of distribution of stress values per area. In fact, for the purpose of this analysis (i.e., to distinguish between dietary groups) around 15 intervals would have been enough to describe at least the main eco-morphological categories.

Whether N = 50 is an adequate number of intervals for other cases is something that needs to be addressed in the future and that might depend on the structure and sample under analysis. It is likely that for more complex geometries or if species from other taxonomic groups are included, the NPCA will differ. Based on our present results, we suggest that the NPCA should be determined on a case-by-case basis.

Comparative biomechanical performance of extant armadillos

Using a NPCA = 50, the PCA of the variance–covariance matrix showed differences between omnivores and both groups of insectivores (Fig. 5A). These observed differences are concordant with previously published results (Serrano-Fochs et al., 2015; Marcé-Nogué et al., 2016), although the present results provide a better distinction of the groups when compared to similar study that only analysed the stress values collected at specific points (Serrano-Fochs et al., 2015) (Fig. 5A). The mandibular ecomorphology of Cingulata has been previously studied using morphometrics, microwear and biomechanics, among other techniques (Fariña, 1985; Fariña, 1988; Vizcaíno & Fariña, 1997; Vizcaíno & Bargo, 1998; Vizcaíno, De Iuliis & Bargo, 1998; De Iuliis, Bargo & Vizcaíno, 2000; Fariña & Vizcaíno, 2001; Vizcaíno et al., 2004; Vizcaíno, 2009; De Esteban-Trivigno, 2011). Nevertheless, the results obtained applying our proposed approach are more accurate when distinguishing between dietary groups. It is noteworthy that none of the previously proposed methods to compare mandibular performance using FEA applied to different species of armadillos (Serrano-Fochs et al., 2015; Marcé-Nogué et al., 2016) were able to effectively distinguish the specialist from the generalist insectivores. Consequently, the approach presented here, especially when using the correlation matrix in the PCA, seems to be able to detect subtler differences, thus representing a useful way to characterize and understand the biomechanical behaviour of the mandibles in relation to diet.

The bi-plot of the first two PCs of the PCA computed using the correlation matrix displayed T. matacus and Z. pichiy in a location that was slightly different than the rest of species of their corresponding dietary group. Classifying diets is always a complicated matter, as it is reducing the existing dietary variability to only a few categories. As explained in the results section, these two species have a diet that differs from the general trend of their groups. In a similar fashion, Chl. truncatus occupies a position along the omnivore/carnivore group instead of showing stress values similar to other insectivores. As previously mentioned, even though this species has been usually grouped with insectivores, Chl. truncatus feeds on worms, snails and roots; all items that need more processing if compared to simply swallowing small insects. It is also relevant that the PCAs of the stress intervals were able to detect these differences in diet, including some subtle differences that have been elusive using other techniques. Even though further studies are required, the proposed procedure seems to be a promising approach to be tested in future ecomorphological studies considering other taxonomic groups.

The PCA computed using the correlation matrix provides information on the variability of all the variables, giving them all the same importance through standardization. This explains why it was possible to distinguish between the two insectivore’s diets even if their differences were rather subtle (Fig. 5B). Nonetheless, interpreting the loadings from the correlation-based PCA can be misleading if it is not properly done. The loadings of the PCA performed using the variance–covariance matrix can be easily interpreted; in the present study, a variable (AΦ[%]) with a higher loading for a given PC represents a larger actual area for that interval of stress values in the mandibles of the specimens located in the direction of that loading. However, in the PCA carried out using the correlation matrix (i.e., where the variables have been standardized), a variable with a higher loading indicates that this variable has a proportionally larger variability in that area of the stress space (but not necessarily in absolute terms). For example, in the Fig. 5B C. unicintus is located in region of the stress space that corresponds to higher loads for high and very high stress variables. This does not mean that the species in question has an area with high stresses larger than its area with small stresses in absolute terms. Rather, it indicates that these high stress variables are proportionally larger as compared with the rest of species. It is important to bear this in mind when using correlation matrix-based PCAs to interpret the results obtained from the intervals method proposed here. As discussed above, overall both PCAs (i.e., using the variance–covariance or correlations matrices) have shown to be very useful for identifying ecomorphological patterns based on stress values obtained from FEA.

We have successfully reduced thousands of data points to just 50 variables that are still biologically meaningful. In addition, we managed to use the output data from FEA, which has a different number of data for each specimen (i.e., due to the differences in the number of elements in each model) and represent it with the same 50 variables in each specimen under analysis making them comparable in a statistical framework. We have shown that at least for our case study this approach works better than previously published examples which are based on either the visual inspection of the stress maps, collecting stress data on specific points, or comparing the complete stress value distributions (Serrano-Fochs et al., 2015; Marcé-Nogué et al., 2016). We consider that for comparative analysis where the main aim is to test the same functional hypothesis under equivalent loads in different species, this method can be generalized to other taxonomic groups and structures. Additionally, it is promising that in addition to the PCAs other techniques might be applied using this newly generated stress variables (intervals) depending on the sample and the biological hypotheses being tested (a matter that should be explored in future studies).

Although the proposed approach implies losing the spatial information of the stress, the case study analysed here strongly supports that the new interval variables are still biologically meaningful and easily interpretable, thus being very useful to describe and analyse the data. Our proposed approach is especially appropriate in cases where the amount of stress might vary but the stress spatial distribution is highly similar. In these situations, it is very difficult to interpret the obtained results, as well as to answer the tested biological hypothesis just by visually inspecting the coloured stress maps. It is not clear yet whether this will work or not in cases where the analysed structures are very different (e.g., when comparing dissimilar morphologies at a higher taxonomic level where usually anatomical differences tend to be prominent). For this reason, we recommend that the newly proposed intervals method be used together with other traditional approaches, such as the visual inspection of the stress and/or deformation maps.

Further research is required to test the advantages and limitations of the intervals method when analysing other anatomical structures and/or taxonomic groups, as well as testing it using three-dimensional models (where the same method can be applied just by simply using volume instead of area in the equations presented here).

Conclusions

The methodology proposed in this work has shown to be applicable independently of the characteristics of the mesh. This is a really useful feature of the method, since most meshes representing biological objects are non-uniform. In addition, the proposed intervals method allows the quantitative comparison of FEA results in a multivariate framework.

Furthermore, when applying this method to our biological case study of armadillo mandibular performance, we have shown that it is a powerful tool to characterize the biomechanical behaviour of the mandibles in relation to different dietary groups, allowing the distinction between different diets, including discrimination between specialist and generalist insectivore species.

This new methodology should be tested in other taxa, as well as at higher taxonomic levels where the stress distribution might be more dissimilar between different taxa. Nonetheless, the positive results obtained when analysing a case study known for its difficulty such as the armadillos suggests that the proposed approach is promising and represents a useful method to be included in the FEA toolkit for comparative analyses.

Supplemental Information

Convergence of the mesh.

Influence of the size of the mesh.

Influence of the homogeneity of the mesh.

Intervals for the armadillos.

Scores of different intervals.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge to Eileen Westwig, Dr. Marcelo Reguero, Dr. Mariano Merino and Dr. Frieder Mayer, who provided S.D.E.T. access to the collections and kindly help with us with the information about specimens. The authors are grateful to Robert Brocklehurst for his comments, corrections and help during the preparation of this manuscript and also want to acknowledge the comments of three anonymous reviewers and the editor Philip Cox that helped to improve the quality of the present manuscript. This research is publication no. 94 of the DFG Research Unit 771 ‘Function and performance enhancement in the mammalian dentition—phylogenetic and ontogenetic impact on the masticatory apparatus’. This research paper is a contribution to the CERCA programme (Generalitat de Catalunya).

Funding Statement

Jordi Marcé-Nogué was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation, KA 1525/9-2). Soledad De Esteban-Trivigno and Josep Fortuny were supported by the Spanish Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad and the European Regional Development Fund of the European Union (MINECO/FEDER EU, project CGL2014-54373-P). Soledad De Esteban-Trivigno was supported by the Catalonian Research Group 2014 SGR 1207, a Synthesys grant (DE-TAF 2273) and Transmitting Science. Josep Fortuny was supported by a postdoc grant “Beatriu de Pinos” 2014–BP-A 00048 from the Generalitat de Catalunya. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Additional Information and Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare there are no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Jordi Marcé-Nogué and Soledad De Esteban-Trivigno conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analysed the data, wrote the paper, reviewed drafts of the paper.

Thomas A. Püschel and Josep Fortuny analysed the data, wrote the paper, reviewed drafts of the paper.

Data Availability

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The raw data has been supplied as a Supplementary File.

References

- Abba et al. (2011).Abba AM, Cassini GH, Cassini MH, Vizcaíno SF. Historia natural del piche llorón Chaetophractus vellerosus (Mammalia: Xenarthra: Dasypodidae) Revista Chilena De Historia Natural. 2011;84:51–64. doi: 10.4067/S0716-078X2011000100004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aquilina et al. (2013).Aquilina P, Chamoli U, Parr WCH, Clausen PD, Wroe S. Finite element analysis of three patterns of internal fixation of fractures of the mandibular condyle. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2013;51:326–331. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attard et al. (2016).Attard MRG, Wilson LAB, Worthy TH, Scofield P, Johnston P, Parr WCH, Wroe S. Moa diet fits the bill: virtual reconstruction incorporating mummified remains and prediction of biomechanical performance in avian giants. Proceedings of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences. 2016;283 doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.2043. Article 20152043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolkovi, Caziani & Protomastro (1995).Bolkovi ML, Caziani SM, Protomastro JJ. Food habits of the three-banded armadillo (Xenarthra: Dasypodidae) in the Dry Chaco, Argentina. Journal of Mammalogy. 1995;76:1199–1204. doi: 10.2307/1382612. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borghi et al. (2011).Borghi CE, Campos CM, Giannoni SM, Campos VE, Sillero-Zubiri C. Updated distribution of the pink fairy armadillo Chlamyphorus truncatus (Xenartra, Dasypodidae), the world’s smallest armadillo. Edentata. 2011;12:14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bright (2014).Bright JA. A review of paleontological finite element models and their validity. Journal of Paleontology. 2014;88:760–769. doi: 10.1666/13-090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bright & Rayfield (2011).Bright JA, Rayfield EJ. The response of cranial biomechanical finite element models to variations in mesh density. Anatomical Record. 2011;294:610–620. doi: 10.1002/ar.21358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Silveira Anacleto (2007).Da Silveira Anacleto TC. Food habits of four armadillo species in the Cerrado area, Mato Grosso, Brazil. Zoological Studies. 2007;46:529–537. doi: 10.3161/1733-5329(2007)9[237:FHOOFP]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dalponte & Tavares-Filho (2004).Dalponte JC, Tavares-Filho JA. Diet of the yellow armadillo, Euphractus sexcinctus, in South-Central Brazil. Edentata. 2004;6:34–41. doi: 10.1896/1413-4411.6.1.37. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dechow & Hylander (2000).Dechow PC, Hylander WL. Elastic properties and masticatory bone stress in the macaque mandible. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 2000;112:553–574. doi: 10.1002/1096-8644(200008)112:4<553::AID-AJPA9>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Esteban-Trivigno (2011).De Esteban-Trivigno S. Ecomorfología de xenartros extintos: análisis de la mandíbula con métodos de morfometría geométrica. Ameghiniana. 2011;48:381–398. doi: 10.5710/AMGH.v481i3(269). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Degrange et al. (2010).Degrange FJ, Tambussi CP, Moreno K, Witmer LM, Wroe S. Mechanical analysis of feeding behavior in the extinct “Terror Bird” Andalgalornis steulleti (Gruiformes: phorusrhacidae) PLOS ONE. 2010;5(8):e11856. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Iuliis, Bargo & Vizcaíno (2000).De Iuliis G, Bargo MS, Vizcaíno SF. Variation in skull morphology and mastication in the fossil giant armadillos Pampatherium spp. and allied genera (Mammalia: Xenarthra: Pampatheriidae), with comments on their systematics and distribution. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 2000;20:743–754. doi: 10.1671/0272-4634(2000)020[0743:VISMAM]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doblaré, García & Gómez (2004).Doblaré M, García JM, Gómez MJ. Modelling bone tissue fracture and healing: a review. Engineering Fracture Mechanics. 2004;71:1809–1840. doi: 10.1016/j.engfracmech.2003.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont et al. (2011).Dumont ER, Davis JL, Grosse IR, Burrows AM. Finite element analysis of performance in the skulls of marmosets and tamarins. Journal of Anatomy. 2011;218:151–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01247.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont, Grosse & Slater (2009).Dumont ER, Grosse IR, Slater GJ. Requirements for comparing the performance of finite element models of biological structures. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 2009;256:96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fariña (1985).Fariña RA. Some functional aspects of mastication in Glyptodontidae (Mammalia) Fortschritte Der Zoologie. 1985;30:277–280. [Google Scholar]

- Fariña (1988).Fariña RA. Observaciones adicionales sobre la biomécanica masticatoria en Glyptodontidae (Mammalia, Edentata) Boletín De La Sociedad Zoológica Del Uruguay. 1988;4:5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Fariña & Vizcaíno (2001).Fariña RA, Vizcaíno SF. Carved teeth and strange jaws: how glyptodonts masticated. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 2001;46:219–234. [Google Scholar]

- Farke (2008).Farke AA. Frontal sinuses and head-butting in goats: a finite element analysis. The Journal of Experimental Biology. 2008;211:3085–3094. doi: 10.1242/jeb.019042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueirido et al. (2014).Figueirido B, Tseng ZJ, Serrano-Alarcón FJ, Martín-Serra A, Pastor JF. Three-dimensional computer simulations of feeding behaviour in red and giant pandas relate skull biomechanics with dietary niche partitioning. Biology Letters. 2014;10 doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2014.0196. Article 20140196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish & Stayton (2014).Fish JF, Stayton CT. Morphological and mechanical changes in juvenile red-eared slider turtle (Trachemys scripta elegans) shells during ontogeny. Journal of Morphology. 2014;275:391–397. doi: 10.1002/jmor.20222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, Janis & Rayfield (2010).Fletcher TM, Janis CM, Rayfield EJ. Finite element analysis of ungulate jaws: can mode of digestive physiology be determined? Palaeontologica Electronia. 2010;13 Article 21A. [Google Scholar]

- Fortuny et al. (2011).Fortuny J, Marcé-Nogué J, De Esteban-Trivigno S, Gil L, Galobart À. Temnospondyli bite club: ecomorphological patterns of the most diverse group of early tetrapods. Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 2011;24:2040–2054. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortuny et al. (2012).Fortuny J, Marcé-Nogué J, Gil L, Galobart À. Skull mechanics and the evolutionary patterns of the otic notch closure in capitosaurs (Amphibia: Temnospondyli) The Anatomical Record: Advances in Integrative Anatomy and Evolutionary Biology. 2012;295:1134–1146. doi: 10.1002/ar.22486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortuny et al. (2015).Fortuny J, Marcé-Nogué J, Heiss E, Sanchez M, Gil L, Galobart À. 3D bite modeling and feeding mechanics of the largest living amphibian, the Chinese giant salamander andrias davidianus (Amphibia:Urodela) PLOS ONE. 2015;10:e0121885. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortuny, Marcé-Nogué & Konietzko-Meier (2017).Fortuny J, Marcé-Nogué J, Konietzko-Meier D. Feeding biomechanics of Late Triassic metoposaurids (Amphibia: Temnospondyli): a 3D finite element analysis approach. Journal of Anatomy. 2017;230(6):752–765. doi: 10.1111/joa.12605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortuny et al. (2016).Fortuny J, Marcé-Nogué J, Steyer J-S, De Esteban-Trivigno S, Mujal E, Gil L. Comparative 3D analyses and palaeoecology of giant early amphibians (Temnospondyli: Stereospondyli) Scientific Reports. 2016;6:30387. doi: 10.1038/srep30387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil, Marcé-Nogué & Sánchez (2015).Gil L, Marcé-Nogué J, Sánchez M. Insights into the controversy over materials data for the comparison of biomechanical performance in vertebrates. Palaeontologia Electronica. 2015;18.1.12A:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Green (2009).Green JL. Dental microwear in the orthodentine of the Xenarthra (Mammalia) and its use in reconstructing the palaeodiet of extinct taxa: the case study of Nothrotheriops shastensis (Xenarthra, Tardigrada, Nothrotheriidae) Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 2009;156:201–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2008.00486.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gunz et al. (2009).Gunz P, Mitteroecker P, Neubauer S, Weber GW, Bookstein FL. Principles for the virtual reconstruction of hominin crania. Journal of Human Evolution. 2009;57:48–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayssen (2014).Hayssen V. Cabassous unicinctus (Cingulata: Dasypodidae) Mammalian Species. 2014;46(907):16–23. doi: 10.1644/907. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lautenschlager (2017).Lautenschlager S. Functional niche partitioning in Therizinosauria provides new insights into the evolution of theropod herbivory. Palaeontology. 2017;60(3):375–387. doi: 10.1111/pala.12289. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loughry & McDonough (2013).Loughry W, McDonough C. The nine-banded armadillo. A natural history. University of Oklahoma Press; Norman: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Marcé-Nogué et al. (2013).Marcé-Nogué J, DeMiguel D, De Esteban-Trivigno S, Fortuny J, Gil L. Quasi-homothetic transformation for comparing the mechanical performance of planar models in biological research. Palaeontologia Electronica. 2013;16 Article 6T. [Google Scholar]

- Marcé-Nogué et al. (2016).Marcé-Nogué J, De Esteban-Trivigno S, Escrig C, Gil L. Accounting for differences in element size and homogeneity when comparing finite element models: armadillos as a case study. Palaeontologia Electronica. 2016;19:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Marcé-Nogué et al. (2015a).Marcé-Nogué J, Fortuny J, De Esteban-Trivigno S, Sánchez M, Gil L, Galobart À. 3D computational mechanics elucidate the evolutionary implications of orbit position and size diversity of early amphibians. PLOS ONE. 2015a;10:e0131320. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcé-Nogué et al. (2015b).Marcé-Nogué J, Fortuny J, Gil L, Sánchez M. Improving mesh generation in finite element analysis for functional morphology approaches. Spanish Journal of Palaeontology. 2015b;31:117–132. [Google Scholar]

- McBee & Baker (1982).McBee K, Baker RJ. Dasypus novemcinctus. Mammalian Species. 1982;162:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- McHenry et al. (2007).McHenry CR, Wroe S, Clausen PD, Moreno K, Cunningham E. Supermodeled sabercat, predatory behavior in Smilodon fatalis revealed by high-resolution 3D computer simulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:16010–16015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706086104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neenan et al. (2014).Neenan JM, Ruta M, Clack JA, Rayfield EJ. Feeding biomechanics in Acanthostega and across the fish-tetrapod transition. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2014;281:20132689–20132689. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.2689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, Angielczyk & Rayfield (2009).Pierce SE, Angielczyk KD, Rayfield EJ. Shape and mechanics in thalattosuchian (Crocodylomorpha) skulls: implications for feeding behaviour and niche partitioning. Journal of Anatomy. 2009;215:555–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2009.01137.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piras et al. (2015).Piras P, Sansalone G, Teresi L, Moscato M, Profico A, Eng R, Cox TC, Loy A, Colangelo P, Kotsakis T. Digging adaptation in insectivorous subterranean eutherians. The enigma of M esoscalops montanensis unveiled by geometric morphometrics and finite element analysis. Journal of Morphology. 2015;276:1157–1171. doi: 10.1002/jmor.20405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Püschel & Sellers (2016).Püschel TA, Sellers WI. Standing on the shoulders of apes: analyzing the form and function of the hominoid scapula using geometric morphometrics and finite element analysis. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 2016;159:325–341. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.22882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayfield (2004).Rayfield EJ. Cranial mechanics and feeding in Tyrannosaurus rex. Proceedings. Biological Sciences/the Royal Society. 2004;271:1451–1459. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy (2008).Reddy J. An introduction to continuum mechanics with applications. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Redford (1985).Redford KH. The evolution and ecology of armadillos, sloths, and vermilinguas. Smithsonian Inst. Press; Washington, D.C.: 1985. Food habits of armadillos (Xenartha: Dasypodidae) pp. 429–437. [Google Scholar]

- Redford & Wetzel (1985).Redford KH, Wetzel RM. Euphractus sexcinctus. Mammalian Species. 1985;252:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, Goldstein & Dewar (1989).Richard AF, Goldstein SJ, Dewar RE. Weed macaques: the evolutionary implications of macaque feeding ecology. International Journal of Primatology. 1989;10:569–594. doi: 10.1007/BF02739365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Fochs et al. (2015).Serrano-Fochs S, De Esteban-Trivigno S, Marcé-Nogué J, Fortuny J, Fariña RA. Finite element analysis of the cingulata jaw: an ecomorphological approach to armadillo’s diets. PLOS ONE. 2015;10:e0120653. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikes, Heidt & Elrod (1990).Sikes RS, Heidt GA, Elrod DA. Seasonal diets of the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus) in a northern part of its range. American Midland Naturalist. 1990;123:383–389. doi: 10.2307/2426566. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith (2008).Smith PM. Lesser hairy armadillo Chaetophractus vellerosus (Gray, 1875) Mammals of Paraguay. 2008;12:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Soibelzon et al. (2007).Soibelzon E, Daniele G, Negrete J, Carlini AA, Plischuk S. Annual diet of the little Hairy Armadillo, Chaetophractus vellerosus (Mammalia, Dasypodidae), in Buenos Aires Province, Argentina. Journal of Mammalogy. 2007;88:1319–1324. doi: 10.1644/06-MAMM-A-335R.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Superina et al. (2009).Superina M, Fernández Campón F, Stevani EL, Carrara R. Summer diet of the pichi Zaedyus pichiy (Xenarthra: Dasypodidae) in Mendoza Province, Argentina. Journal of Arid Environments. 2009;73:683–686. doi: 10.1016/j.jaridenv.2009.01.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Superina, Pagnutti & Abba (2014).Superina M, Pagnutti N, Abba AM. What do we know about armadillos? An analysis of four centuries of knowledge about a group of South American mammals, with emphasis on their conservation. Mammal Review. 2014;44:69–80. doi: 10.1111/mam.12010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng & Flynn (2014).Tseng ZJ, Flynn JJ. Convergence analysis of a finite element skull model of Herpestes javanicus (Carnivora, Mammalia): implications for robust comparative inferences of biomechanical function. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 2014;365:112–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizcaíno (2009).Vizcaíno SF. The teeth of the “toothless”: novelties and key innovations in the evolution of xenarthrans (Mammalia, Xenarthra) Paleobiology. 2009;35:343–366. doi: 10.1666/0094-8373-35.3.343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vizcaíno & Bargo (1998).Vizcaíno SF, Bargo MS. The masticatory apparatus of the armadillo Eutatus (Mammalia, Cingulata) and some allied genera: paleobiology and evolution. Paleobiologia. 1998;24:371–383. [Google Scholar]

- Vizcaíno, De Iuliis & Bargo (1998).Vizcaíno SF, De Iuliis G, Bargo MS. Skull shape, masticatory apparatus, and diet of Vassallia and Holmesina (Mammalia: Xenarthra: Pampatheriidae): when anatomy constrains destiny. Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 1998;5:291–322. doi: 10.1023/A:1020500127041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vizcaíno & Fariña (1997).Vizcaíno SF, Fariña RA. Diet and locomotion of the armadillo Peltephilus: a new view. Lethaia. 1997;30:79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Vizcaíno et al. (2004).Vizcaíno SF, Fariña RA, Bargo MS, De Iuliis G. Functional and phylogenetic assessment of the masticatory adaptations in Cingulata (Mammalia, Xenarthra) Ameghiniana. 2004;41:651–664. [Google Scholar]

- Walmsley et al. (2013).Walmsley CW, Smits PD, Quayle MR, McCurry MR, Richards HS, Oldfield CC, Wroe S, Clausen PD, McHenry CR. Why the long face? The mechanics of mandibular symphysis proportions in crocodiles. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e53873. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wroe, McHenry & Thomason (2005).Wroe S, McHenry CR, Thomason JJ. Bite club: comparative bite force in big biting mammals and the prediction of predatory behaviour in fossil taxa. Proceedings of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences. 2005;272:619–625. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zienkiewicz, Taylor & Zhu (2013).Zienkiewicz O, Taylor Z, Zhu J. The finite element method: its basis and fundamentals. Butterworth-Heinemann; Oxford: 2013. p. 756. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Convergence of the mesh.

Influence of the size of the mesh.

Influence of the homogeneity of the mesh.

Intervals for the armadillos.

Scores of different intervals.

Data Availability Statement

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The raw data has been supplied as a Supplementary File.