Abstract

Cancer stem cells (CSCs), which have the potential for self-renewal, differentiation and de-differentiation, undergo epigenetic, epithelial-mesenchymal, immunological and metabolic reprogramming to adapt to the tumor microenvironment and survive host defense or therapeutic insults. Intra-tumor heterogeneity and cancer-cell plasticity give rise to therapeutic resistance and recurrence through clonal replacement and reactivation of dormant CSCs, respectively. WNT signaling cascades cross-talk with the FGF, Notch, Hedgehog and TGFβ/BMP signaling cascades and regulate expression of functional CSC markers, such as CD44, CD133 (PROM1), EPCAM and LGR5 (GPR49). Aberrant canonical and non-canonical WNT signaling in human malignancies, including breast, colorectal, gastric, lung, ovary, pancreatic, prostate and uterine cancers, leukemia and melanoma, are involved in CSC survival, bulk-tumor expansion and invasion/metastasis. WNT signaling-targeted therapeutics, such as anti-FZD1/2/5/7/8 monoclonal antibody (mAb) (vantictumab), anti-LGR5 antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) (mAb-mc-vc-PAB-MMAE), anti-PTK7 ADC (PF-06647020), anti-ROR1 mAb (cirmtuzumab), anti-RSPO3 mAb (rosmantuzumab), small-molecule porcupine inhibitors (ETC-159, WNT-C59 and WNT974), tankyrase inhibitors (AZ1366, G007-LK, NVP-TNKS656 and XAV939) and β-catenin inhibitors (BC2059, CWP232228, ICG-001 and PRI-724), are in clinical trials or preclinical studies for the treatment of patients with WNT-driven cancers. WNT signaling-targeted therapeutics are applicable for combination therapy with BCR-ABL, EGFR, FLT3, KIT or RET inhibitors to treat a subset of tyrosine kinase-driven cancers because WNT and tyrosine kinase signaling cascades converge to β-catenin for the maintenance and expansion of CSCs. WNT signaling-targeted therapeutics might also be applicable for combination therapy with immune checkpoint blockers, such as atezolizumab, avelumab, durvalumab, ipilimumab, nivolumab and pembrolizumab, to treat cancers with immune evasion, although the context-dependent effects of WNT signaling on immunity should be carefully assessed. Omics monitoring, such as genome sequencing and transcriptome tests, immunohistochemical analyses on PD-L1 (CD274), PD-1 (PDCD1), ROR1 and nuclear β-catenin and organoid-based drug screening, is necessary to determine the appropriate WNT signaling-targeted therapeutics for cancer patients.

Keywords: APC, CTNNB1, FGFR1, FGFR2, PI3K, RNF43, RSPO2, WNT2B, WNT5A, YAP

1. Introduction

Cancer stem cells (CSCs), which show the potential for self-renewal and differentiation, have been identified in a variety of human cancers based on their tumor initiating potential in vivo (1–3). Clonal expansion of a minor CSC population with a drug-resistant mutation causes early recurrence, whereas reactivation of dormant CSCs into cycling CSCs owing to tumor plasticity leads to late relapse (4–6). CSCs or bulk tumor cells undergo epigenetic reprogramming (7), epithelial-mesenchymal reprogramming [epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET)] (8,9), immunological reprogramming (immunoediting) (10,11) and metabolic reprogramming (12) to adapt to the tumor microenvironment, which is collectively defined here as 'omics reprogrammming' (Fig. 1). Since cycling CSCs that depend on aerobic glycolysis converge into quiescent mesenchymal CSCs through omics reprogramming to survive therapeutic insult for later recurrence, CSC targeting is necessary to avoid relapse after cancer therapy and improve the cost-effectiveness ratio of cancer precision medicine.

Figure 1.

Therapeutic resistance owing to evolution and plasticity of cancer stem cells (CSCs). CSCs with self-renewal, differentiation and de-differentiation potentials undergo omics reprogramming, such as epigenetic reprogramming, immunoediting (immunological reprogramming), two-way shifts between epithelial and mesenchymal states (epithelial-mesenchymal reprogramming) and two-way shifts between aerobic glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation in the tricarboxylic acid cycle (metabolic reprogramming). Genetic or epigenetic evolution of CSCs gives rise to a repertoire of drug-resistant CSCs, which cause early recurrence through clonal expansion of drug-resistant CSCs replacing drug-sensitive bulk tumors. By contrast, the plasticity of CSCs with omics reprogramming potential gives rise to dormant CSCs to survive host defense or therapeutic insult, which cause late relapse through reactivation of dormant CSCs into cycling CSCs. CSC-targeted therapeutics are necessary to avoid drug resistance or recurrence after anticancer therapy. MDSC, myeloid-derived suppressor cell; NK, natural killer cell; Treg, regulatory T cell.

CD44, CD133 (PROM1), EPCAM and LGR5 (GPR49) are representative cell-surface markers of CSCs (2,13–16). LGR5, encoding an R-spondin (RSPO) receptor, is a target gene of the canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling cascade in quiescent as well as cycling stem cells, whereas CD44 and CD133 are further upregulated by WNT and RSPO signals in LGR5+ cycling stem/progenitor cells (17–19). EPCAM can potentiate the canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling cascade through intra-membrane proteolysis and subsequent nuclear translocation of its intracellular C-terminal domain (20). WNT signaling cascades cross-talk with the FGF, Notch, Hedgehog and TGFβ/BMP signaling cascades to constitute the stem cell signaling network, which regulates expression of functional CSC markers (21–24).

The WNT family proteins transduce signals through the Frizzled (FZD) and LRP5/6 receptors to the WNT/β-catenin and WNT/STOP (stabilization of proteins) signaling cascades (also known as the canonical WNT signaling cascades) and through the FZD and/or ROR1/ROR2/RYK receptors to the WNT/PCP (planar cell polarity), WNT/RTK (receptor tyrosine kinase) and WNT/Ca2+ signaling cascades (also known as the non-canonical WNT signaling cascades) (21,25–29). The canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling cascade is involved in self-renewal of stem cells and proliferation or differentiation of progenitor cells (30–33), whereas non-canonical WNT signaling cascades are involved in maintenance of stem cells, directional cell movement or inhibition of the canonical WNT signaling cascade (34–37). Both canonical and non-canonical WNT signaling cascades play key roles in the development and evolution of CSCs.

By contrast, tumors consist of heterogeneous populations of cancer cells and non-cancerous stromal/immune cells (38,39). Intra-tumor heterogeneity of cancer cells is caused by the evolution of CSCs based on epigenetic and genetic alterations (40–42), as well as the differentiation of CSCs into bulk tumor cells (1–3), niche-like cancer supporting cells (43), endothelial-like cancer cells (44) and fibroblast-like cancer cells (45). On the other hand, intra-tumor heterogeneity of non-cancerous stromal/immune cells is orchestrated by and reciprocally orchestrates CSCs and their descendants (39,45–47). Interaction and co-evolution of CSCs and niche cells are driving forces of cancer progression. Herein, canonical and non-canonical WNT signaling in CSCs will be described, with a focus on the heterogeneity of cancer and stromal/immune cells in the tumor microenvironment; then, anti-CSC mono- and combination therapies using WNT signaling-targeted therapeutics will be reviewed with emphases on omics reprogramming and tumor plasticity.

2. Canonical WNT signaling in CSCs and their niches

Canonical WNT signaling through the FZD-LRP5/6 receptor complex leads to de-repression of β-catenin as well as STOP-target proteins, such as ATOH1, CCND1 (Cyclin D1), FOXM1, MYC (c-MYC), NRF2 (NFE2L2), PLK1, SMAD1/3/4, SNAI1 (Snail) and YAP/TAZ, from proteasomal degradation induced by GSK-3β-dependent phosphorylation and subsequent ubiquitylation (27–29,48) (Fig. 2). β-catenin stabilization and subsequent nuclear translocation leads to transcriptional activation of β-catenin-TCF/LEF target genes, such as ATOH1, CCND1, CD44, FGF20, JAG1, LGR5, MYC and SNAI1, although transcriptional outputs of the WNT/β-catenin signaling cascade are determined in a cellular context-dependent manner (e.g., epigenetic status of target genes and activities of other transcriptional regulators). ATOH1, CCND1, MYC and SNAI1 are upregulated transcriptionally and post-translationally by the β-catenin and STOP signaling cascades, respectively. Canonical WNT signals control cell fate and function through transcriptional and post-translational regulation of the omics network.

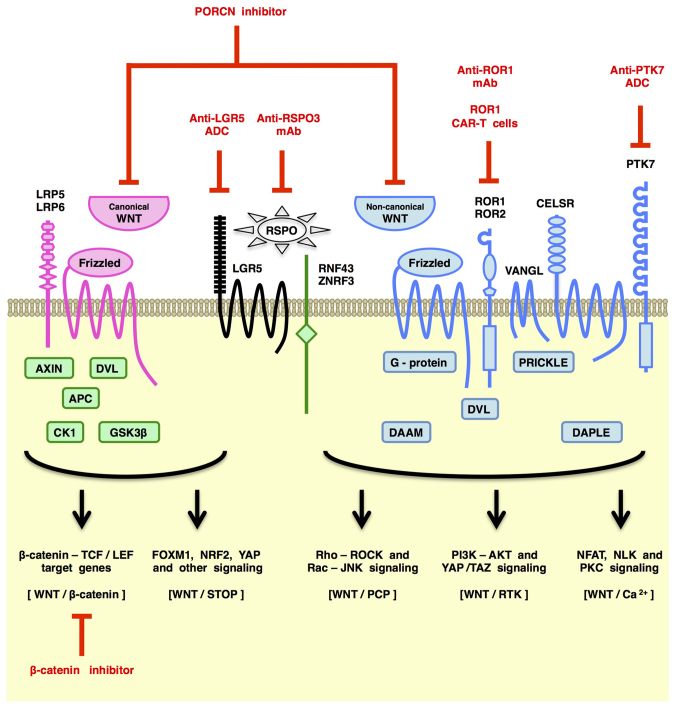

Figure 2.

Overview of WNT signaling cascades and WNT signaling-targeted therapeutics. WNT signals are transduced by multiple downstream signaling cascades in a cell context-dependent manner. Canonical WNT signaling through Frizzled (FZD) and LRP5/6 receptors is transduced by the WNT/β-catenin and WNT/STOP (stabilization of proteins) signaling cascades, whereas non-canonical WNT signaling through FZD and/or ROR1/ROR2/RYK receptors is transduced by the WNT/PCP (planar cell polarity), WNT/RTK (receptor tyrosine kinase) and WNT/Ca2+ signaling cascades. Antibody-based drugs, such as anti-LGR5 antibody-drug conjugate (ADC), anti-RSPO3 monoclonal antibody (mAb), anti-ROR1 mAb and anti-PTK7 ADC, ROR1 chimeric antigen receptor-modified T (CAR-T) cells, porcupine (PORCN) inhibitors and β-catenin inhibitors are representative WNT signaling-targeted therapeutics in clinical trials or preclinical studies for the treatment of cancer patients.

Canonical WNT signaling in CSCs is activated by WNT2B, WNT3 and other canonical WNT ligands derived from cancerous supporting cells or non-cancerous stromal cells (49–52), as well as genetic alterations in the canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling components, such as EIF3E-RSPO2 fusions, PTPRK-RSPO3 fusions, gain-of-function mutations in the CTNNB1 (β-catenin) gene and loss-of-function mutations in the APC, AXIN1, AXIN2, RNF43 and ZNRF3 genes (29,53–55). Canonical WNT signals increase the LGR5 receptor level on CSCs for the maintenance of the canonical WNT responsive state but also upregulate AXIN2, DKK1, NOTUM, RNF43 and ZNRF3 for negative feedback regulation (18–21,29). Loss-of-function mutations in the APC, AXIN2, RNF43 and ZNRF3 genes release CSCs from the constraints of the negative feedback regulation.

Canonical WNT signals can directly promote CSC proliferation through upregulation of CCND1, FOXM1, MYC and YAP/TAZ as described above. By contrast, canonical WNT signaling in CSCs induces expression and secretion of growth factors, such as FGFs, KIT ligand (KITLG or SCF) and VEGF (VEGFA), to fine-tune the tumor microenvironment (18,21,29). For example, MET (HGF receptor) is upregulated in human basal-like breast cancers with TP53 mutations as well as mouse basal-like breast tumors with compound gain-of-function Ctnnb1 mutation and homozygous Tp53 deletion (56), and combined activation of the canonical WNT/β-catenin and HGF/MET signaling cascades induces SHH upregulation in mouse mammary CSCs and subsequent activation of cancer-associate fibroblasts for the synergistic proliferation of CSCs and cancer-associate fibroblasts (57).

Together, these findings indicate that canonical WNT signaling is involved in the maintenance and expansion of CSCs through direct effects on CSCs themselves and indirect effects via CSC-stromal/immune interactions.

3. Non-canonical WNT signaling in CSCs and their niches

Non-canonical WNT signaling through FZD receptors and/or ROR1/ROR2/RYK co-receptors activates the PCP, RTK or Ca2+ signaling cascades (Fig. 2).

Non-canonical WNT/PCP signaling through FZD receptors and Dishevelled (DVL) adaptor proteins regulates the coordinated cellular orientation within an epithelial plane, collective cell movements during gastrulation and neurulation stages of embryogenesis and directional cell movement during invasion and metastasis of cancer cells (58–62). WNT/PCP signals are converted to actin cytoskeletal dynamics via the small G-proteins RAC and RHO (Fig. 2), and then, RAC and RHO activate JNK-dependent transcription and YAP/TAZ-dependent transcription, respectively (63–66). WNT/PCP signaling regulates actin cytoskeletal dynamics, directional cell movement and JNK- or YAP/TAZ-dependent transcription.

Non-canonical WNT signaling through RTKs, such as ROR1, ROR2 and RYK, activates the PI3K-AKT signaling cascade (29,67–69). ROR1 and ROR2, with the extracellular WNT-binding FZD-like domain, are homologous to MUSK, NTRK1, NTRK2, NTRK3, DDR1 and DDR2 in their cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase domain, whereas RYK with an extracellular WNT-binding WIF domain is homologous to AXL, EGFR, ERBB2, ERBB3, ERBB4, MET, MERTK, MST1R and TYRO3 in its cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase domain (39,70–73). ROR1 and ROR2 are atypical RTKs that are defective in intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity for auto-phosphorylation; however, ROR1 and ROR2 can be tyrosine phosphorylated by other tyrosine kinases, such as EGFR, ERBB3, MET and SRC, to activate the PI3K-AKT and YAP signaling cascades (29,74–78) (Fig. 2). WNT/RTK signaling is involved in therapeutic resistance and recurrence of human cancers in part through PI3K-AKT signaling activation.

Non-canonical WNT signals induce cytosolic Ca2+ elevation through Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum or Ca2+ influx from the extracellular space. WNT signaling through Frizzled receptors are involved in Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum via small G-protein- or SEC14L2-mediated activation of phospholipase C (PLC) and subsequent generation of inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) (21,79–81). WNT signaling through Polycystin 1 (PKD1) is proposed to induce Ca2+ influx through a TRPP2 Ca2+ channel (82). Ca2+/Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CAMK2) and Calcineurin are representative downstream effectors of the WNT/Ca2+ signaling cascade (Fig. 2). For example, WNT/Ca2+ signaling-dependent CAMK2 activation leads to phosphorylation and activation of Nemo-like kinase (NLK), which can inhibit canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling in some cells (83). WNT-dependent CamK2 activation in cardiomyocytes gives rise to cardiac hypertrophy through phosphorylation and cytoplasmic tethering of Hdac4 and subsequent de-repression of Mef2 target genes (84). WNT/Ca2+ signaling-dependent Calcineurin activation leads to dephosphorylation and subsequent nuclear translocation of NFAT for the transcriptional activation of NFAT-target genes (85). By contrast, KRAS-dependent FZD8 repression in pancreatic cancer cells leads to potentiation of tumorigenesis through WNT/Ca2+ signaling inhibition (37). WNT/Ca2+ signaling to downstream effectors, such as CAMK2 and Calcineurin, is involved in a variety of cellular processes through transcriptional activation of NFAT-target genes, de-repression of MEF2-target genes and repression WNT/β-catenin-target genes in a cellular context-dependent manner.

Non-canonical WNT signaling in CSCs is activated by WNT5A, WNT11 and other non-canonical WNT ligands (58) that are secreted from cancer cells (86,87) or stromal/immune cells (88,89), as well as genetic alterations that trans-activate non-canonical WNT signaling cascades, such as E2A-PBX1 fusion and MET amplification (74–76). Non-canonical WNT signaling through FZD7 activates the PI3K-AKT signaling cascade as a result of Daple (CCDC88C)-mediated dissociation of Gβγ from Gαi (90), whereas non-canonical WNT signaling through ROR1 activates PI3K-AKT signaling cascade owing to ROR1 trans-phosphorylation by other tyrosine kinases, such as MET and SRC (67,75). ROR1 is involved in HER3-Y1307 trans-phosphorylation and subsequent NSUN6-dependent MST1-K59 methylation, which induces YAP/TAZ-dependent transcriptional activation through LATS1/LATS2 inhibition (78). WNT/PCP signaling can also induce Rho-mediated LATS1/LATS2 inhibition for transcriptional activation of YAP/TAZ-target genes (91,92), whereas non-canonical WNT signaling through FZD10 induces YAP/TAZ activation through Gα13 (93). Non-canonical WNT signaling promotes survival and therapeutic resistance of CSCs through PI3K-AKT signaling activation and YAP/TAZ-mediated transcriptional activation.

By contrast, invasion and metastasis are driven by canonical WNT signaling cascades and non-canonical WNT signaling cascades. For example, canonical WNT/β-catenin and WNT/STOP signaling cascades synergistically upregulate SNAI1 to repress epithelial genes, such as CDH1 (E-cadherin), for the initiation of EMT of CSCs, and non-canonical WNT signals promote invasion, survival and metastasis of CSCs or circulating tumor cells (28,29,35,62,87). Together, these findings clearly indicate that canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling as well as other WNT signaling cascades are critically involved in the malignant features of CSCs.

4. Anti-CSC mono-therapy targeting WNT signaling cascades

WNT signaling cascades are hot and cutting-edge topics in the field of translational oncology and medicinal chemistry (29,94–96). Therapeutics directly targeting WNT signaling cascades are classified into i) ligand/receptor-targeted drugs binding to ligands or transmembrane proteins involved in WNT signaling, ii) porcupine (PORCN) inhibitors abrogating WNT secretion and FZD-dependent signaling, iii) tankyrase (TNKS) inhibitors repressing WNT/β-catenin and WNT-independent signaling cascades and iv) β-catenin inhibitors blocking TCF/LEF-dependent transcription (Table I).

Table I.

WNT signaling inhibitors and anti-CSC effects.

| Category | Drug | Preclinical Anti-CSC TX | (Refs.) | Drug development stage | Details of clinical trials for cancer patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand/receptor- targeted drug | Anti-FZD1/2/5/7/8 mAb (Vantictumab, OMP-18R5) | Breast CSC | (97) | P1 (NCT01345201) | Solid tumors, Mono |

| Panc CSC | P1 (NCT01957007) | Solid tumors. Combo | |||

| P1 (NCT01973309) | Breast, Combo | ||||

| P1 (NCT02005315) | Panc, Combo | ||||

| Anti-FZD5 mAb (IgG-2919) | (52) | Preclinical | |||

| Anti-FZD10 ADC (OTSA101-DTPA-90Y) | (98) | Terminated in P1 | Too slow accrual | ||

| Anti-LGR5 ADC (mAb-mc-vc-PAB-MMAE) | (99) | Preclinical | |||

| Anti-PTK7 ADC (PF-06647020) | Breast CSC | (100) | P1 (NCT02222922) | Solid tumors, Mono | |

| Lung CSC | |||||

| Ovary CSC | |||||

| Anti-ROR1 mAb (Cirmtuzumab, UC-961) | Ovary CSC | (101) | P1 (NCT02222688) | CLL, Mono | |

| P1 (NCT02776917) | Breast, Combo | ||||

| P1/2 (NCT03088878) | CLL/MCL/SLL, Combo | ||||

| Anti-RSPO3 mAb (Rosmantuzumab, OMP-131R10) | Colorectal CSC | (102) | P1 (NCT02482441) | Solid tumors, Combo | |

| ROR1 CAR-T cells | (103) | Preclinical | |||

| WNT-trapping FZD8-Fc (Ipafricept, OMP-54F28) | Panc CSC | (104) | P1 (NCT01608867) | Solid tumors, Mono | |

| P1 (NCT02050178) | Panc. Combo | ||||

| P1 (NCT02069145) | Liver, Combo | ||||

| P1 (NCT02092363) | Ovary, Combo | ||||

| PORCN inhibitor | ETC-159 | (109) | P1 (NCT02521844) | Solid tumors, Mono | |

| IWP-2 | (110) | Preclinical | |||

| WNT-C59 | (111) | Preclinical | |||

| WNT974 (LGK974) | CML CSC | (112) | P1 (NCT01351103) | Solid tumors, Mono | |

| Lung CSC | (43) | P1/2 (NCT02278133) | mCRC, Combo | ||

| TNKS inhibitor | AZ1366 | (117) | Preclinical | ||

| G007-LK | (118) | Preclinical | |||

| JW55 | (119) | Preclinical | |||

| NVP-TNKS656 | (120) | Preclinical | |||

| XAV939 | (121) | Preclinical | |||

| β-catenin inhibitor | BC2059 | AML CSC | (130) | Preclinical | |

| CGP049090 | (131) | Preclinical | |||

| CWP232228 | Liver CSC | (132) | Preclinical | ||

| ICG-001 | Ovary CSC | (133) | Preclinical | ||

| KY-05009 | (128) | Preclinical | |||

| LF3 | (134) | Preclinical | |||

| Mebendazole | (129) | P1 (NCT01729260) | Glioma, Mono | ||

| P1 (NCT02644291) | Glioma, Mono | ||||

| P1/2 (NCT01837862) | Glioma, Combo | ||||

| MSAB | (126) | Preclinical | |||

| PF-794 | (138) | Peclinical | |||

| PKF115-584 | (135) | Preclinical | |||

| PRI-724 | (136) | P1 (NCT01764477) | Panc, Combo | ||

| P1/2 (NCT01606579) | AML/CML, Combo | ||||

| SAH-BCL9 | (137) | Preclinical |

PORCN, porcupine; TNKS, tankyrase; PPI, protein-protein interaction; mAb, monoclonal antibody; bsAb, bispecific antibody; ADC, antibody-drug conjugate; P1, phase I; P2, phase II; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; Breast, breast cancer; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; Liver, hepatocellular carcinoma; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; mCRC, metastatic colorectal cancer; NPC, nasopharyngealcarcinoma; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; Ovary, ovarian cancer; Panc, pancreatic cancer; SLL, small lymphocytic lymphoma; Mono, mono-therapy; Combo, combination therapy.

Human/humanized monoclonal antibody (mAb) drugs, such as anti-FZD1/2/5/7/8 mAb (vantictumab/OMP-18R5) (97), anti-FZD5 mAb (IgG-2919) (52), anti-FZD10 antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) (OTSA101-DTPA-90Y) (98), anti-LGR5 ADC (mAb-mc-vc-PAB-MMAE) (99), anti-PTK7 ADC (PF-06647020) (100), anti-ROR1 mAb (cirmtuzumab/UC-961) (101) and anti-RSPO3 mAb (rosmantuzumab/OMP-131R10) (102) have been developed as large-molecule cancer therapeutics. ROR1 CAR-T cells (103) and WNT-trapping FZD8-Fc chimeric protein (ipafricept/OMP-54F28) (104) are also classified as WNT ligand/receptor-targeted drugs. Among this class of therapeutics, cirmtuzumab, ipafricept, PF-06647020, rosmantuzumab and vantictumab, which showed anti-CSC effects in preclinical model experiments, are in clinical trials to treat cancer patients (Table I).

PORCN inhibitors restrain PORCN-dependent palmitoleoylation of WNT family ligands in the endoplasmic reticulum, which obstructs WNT signaling through blockade of WNT secretion as well as palmitoleoylated WNT-mediated oligomerization of FZD receptors (105–108). ETC-159 (109), IWP-2 (110), WNT-C59 (111) and WNT974 (LGK974) (112) are small-molecule PORCN inhibitors. A preclinical study of IWP-2 on organoids derived from colorectal cancer patients revealed that PORNC inhibitors are applicable for the treatment of cancers with RNF43 mutations but not APC mutations (52). By contrast, preclinical studies of WNT974 indicated that PORNC inhibitors repress the survival and tumor initiating potential of CSCs (43,112). ETC-159 and WNT974 are in clinical trials for the treatment of cancer patients (Table I).

TNKS inhibitors repress TNKS-dependent poly-ADP-ribosylation and subsequent degradation of negative regulators of oncogenic signaling cascades, such as AXIN family proteins, AMOT family proteins, PTEN and TERF1 (TRF1), which results in inhibition of WNT/β-catenin signaling, repression of YAP-dependent transcription, suppression of PI3K signaling and telomere shortening, respectively (113–116). AZ1366 (117), G007-LK (118), JW55 (119), NVP-TNKS656 (120) and XAV939 (121) are representative TNKS inhibitors that abrogate WNT/β-catenin signaling and tumorigenesis in preclinical mouse model experiments. TNKS inhibitors show synergistic antitumor effects with other therapeutics, such as an AKT inhibitor (API2), EGFR inhibitors (gefitinib and erlotinib), a MEK inhibitor (AZD6244), a PI3K inhibitor (BKM120) and irinotecan (117,118,120,122–124). TNKS inhibitors are promising candidates for CSC-targeted therapeutics; however, because of diverse on-target effects, TNKS inhibitors stalled in their preclinical stage.

β-catenin inhibitors block TCF/LEF-dependent transcription through inhibition of protein-protein interactions (PPI) between β-catenin and other transcriptional regulators (29,125), promotion of β-catenin degradation (126) or inhibition of β-catenin kinases, such as TNIK (127–129). BC2059 (130), CGP049090 (131), CWP232228 (132), ICG-001 (133), LF3 (134), PKF115–584 (135), PRI-724 (136) and SAH-BCL9 (137) are small-molecule β-catenin PPI inhibitors. MSAB is a small-molecule compound that binds to β-catenin and promotes proteasomal degradation of β-catenin (126). KY-05009 (128), mebendazole (129) and PF-794 (138) are TNIK inhibitors that repress phosphorylation of TNIK substrates, such as TCF4, FMNL2, PRICKLE1, SMAD1 and SMAD2, which leads to inhibition of β-catenin-TCF/LEF-dependent transcription and a variety of cellular processes. Among the β-catenin inhibitors mentioned above, BC2059, CWP232228 and ICG-001 repress the expansion of CSCs. The β-catenin inhibitors PRI-724 and mebendazole are in phase I/II clinical trials for cancer patients (Table I), whereas other β-catenin inhibitors are still in the preclinical stage of drug development. β-catenin inhibitors are challenging therapeutics for cancer patients.

WNT signaling cascades are the major driver of various types of human cancers (29), but the development of many WNT signaling-targeted therapeutics is stuck in the preclinical stage or phase I/II stages of clinical trials (Table I) because of the complexity of WNT signaling cascades and genetic alterations in non-enzymatic signaling components. MAb-based drugs and PORCN inhibitors with the potential to target CSCs as well as bulk cancer cells are promising therapeutics for the patients with WNT signaling-driven cancers.

5. Anti-CSC combination therapy using WNT signaling-targeted drugs

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors are rational anticancer therapeutics because tyrosine kinases with intrinsic enzyme activities are aberrantly activated in cancer cells owing to genetic alterations. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors have contributed to the improved prognosis of cancer patients and are essential for genome-based precision medicine; however, unavoidable drug resistance or recurrence is a serious issue for cancer patients and health care systems (4).

Activated tyrosine kinases, such as BCR-ABL fusion kinase, EGFR-T790M mutant, FLT3 internal tandem duplication (FLT3-ITD) mutant, KIT-D814V mutant and RET, promote β-catenin phosphorylation at Y654 to release E-cadherin-bound β-catenin from the adherens junction for its stabilization and subsequent nuclear translocation (139–143). By contrast, canonical WNT signals inhibit β-catenin phosphorylation at S33, S37, T41 and S45 to release β-catenin from proteasomal degradation for its stabilization and nuclear translocation (21,25,26,29). Since canonical WNT signals and oncogenic tyrosine kinases converge to β-catenin stabilization for the maintenance and expansion of CSCs, canonical WNT signaling inhibitors can block CSC evasion of tyrosine kinase inhibitors. For example, the porcupine inhibitor WNT974 significantly reduced residual stem/progenitor cells of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) after treatment with the BCR-ABL inhibitor nilotinib via blockade of WNT ligand secretion into the bone marrow microenvironment (112); the β-catenin inhibitors ICG-001 and PRI-724 induced synergistic effects with the BCR-ABL inhibitors imatinib and nilotinib, respectively, on CML stem/progenitor cells (136,144); and the TNKS inhibitor AZ1366 and EGFR inhibitor gefitinib showed synergistic effects on lung cancer cells in vivo (124). These preclinical studies indicate that combination therapies using WNT signaling-targeted therapeutics and tyrosine kinase inhibitors might be applicable for treatment of a subset of patients with tyrosine kinase-driven cancers (Fig. 3).

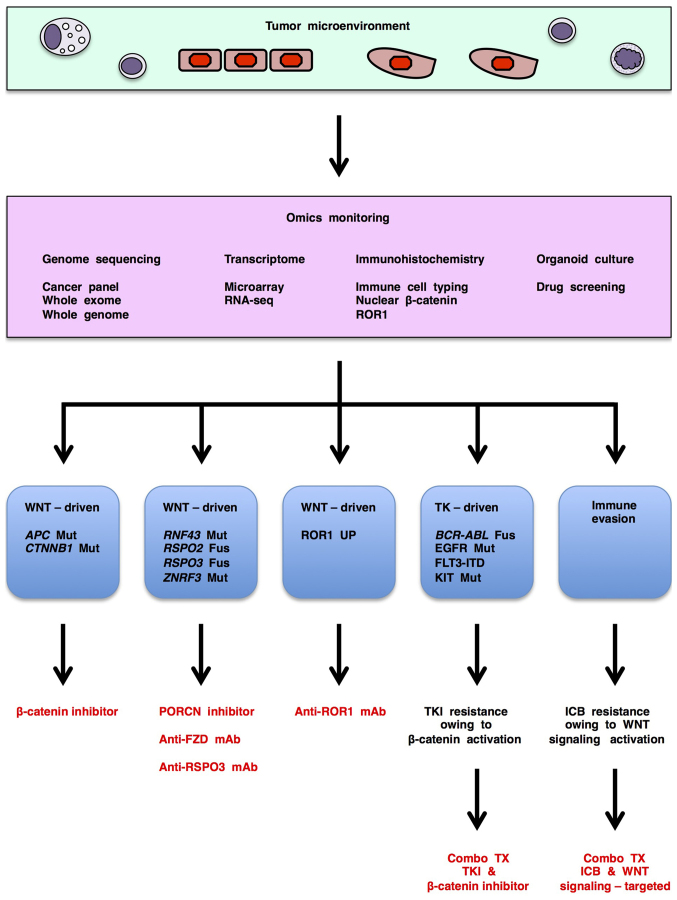

Figure 3.

Investigational WNT signaling-targeted therapeutics for genome-based precision medicine. WNT signaling-targeted therapeutics are applicable for mono-therapy of WNT-related human cancers: β-catenin inhibitors for WNT-driven cancers with APC or CTNNB1 alterations; porcupine (PORCN) inhibitors, anti-FZD or anti-RSPO3 monoclonal antibody (mAb) for WNT-driven cancers with RNF43, RSPO2, RSPO3 or ZNRF3 alterations; and anti-ROR1 mAb for WNT-driven cancers with ROR1 upregulation. By contrast, WNT signaling-targeted therapeutics are applicable for combination therapies with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) to treat a subset of tyrosine kinase (TK)-driven cancers. WNT signaling-targeted therapeutics are also applicable for combination therapies with immune checkpoint blockers (ICB) to treat cancers with immune evasion; however, because WNT signals regulate immune evasion and antitumor immunity in a context-dependent manner, monitoring of WNT signaling and immunity is mandatory to select an appropriate class of WNT signaling-targeted therapeutics for combination immunotherapy. Therefore, omics monitoring, including genome sequencing, transcriptomic, immunohistochemical and organoid-based tests, is necessary before and during selection of WNT signaling-targeted therapeutics for cancer patients. Mut, mutation; Fus, fusion.

Immune checkpoint blockers that abrogate interactions of ligands and inhibitory receptors on CD8+ T cells are promising antitumor drugs in the clinic or clinical trials (145–151). PD-L1 (CD274) is a representative ligand for inhibitory immune signaling, whereas PD-1 (PDCD1) and CTLA4 are representative receptors for inhibitory immune signaling. Anti-PD-L1 mAbs (atezolizumab, avelumab and durvalumab), anti-PD-1 mAbs (nivolumab and pembrolizumab) and an anti-CTLA4 mAb (ipilimumab) are approved for the treatment of patients with melanoma or other types of solid tumors. Immune checkpoint blockers result in significant therapeutic effects in a subset of patients; however, the lack of benefits in other patients owing to primary or acquired resistance to immune checkpoint blockers has resulted in a cost-effectiveness issue (152–156).

Canonical WNT signaling activation in melanoma induces immune evasion through CCL4 repression and immunological reprogramming into non-T cell-infiltrated melanoma (11). Since melanoma-derived WNT5A promotes β-catenin signaling activation and subsequent IDO upregulation in dendritic cells to induce immune evasion through accumulation of regulatory T (Treg) cells, combination immunotherapy using the porcupine inhibitor WNT-C59 and anti-CTLA4 mAb showed synergistic anti-melanoma effects in vivo (157). By contrast, WNT5A and ROR2 are relatively frequently upregulated in pretreatment tumors of melanoma patients that do not respond to PD-1 immune checkpoint blockade (158), which suggests involvement of non-canonical WNT signaling in resistance to immune checkpoint blockers. Since DKK1-dependent canonical WNT signaling inhibition or putative reciprocal non-canonical WNT signaling activation in tumor microenvironment induces immune evasion through accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and depletion of T cells (159), combination therapy using anti-DKK1 mAb (BHQ880 or DKN-01) (160,161) and immune checkpoint blockers might show synergistic antitumor effects in vivo. WNT signaling-targeted therapeutics might be applicable for combination immunotherapy for cancer patients (Fig. 3); however, context-dependent effects of WNT signaling on immunity (4) should be kept in mind.

6. Omics monitoring for WNT signaling-targeted therapy

WNT-related human cancers are classified into three major subtypes based on signaling aberrations associated with therapeutic choices (Fig. 3): APC/CTNNB1-altered cancers with WNT/β-catenin signaling activation that can be treated with β-catenin inhibitors; RNF43/ZNRF3/RSPO2/RSPO3-altered cancers with WNT/β-catenin and other WNT signaling activation that can be treated with PORCN inhibitors, anti-FZD mAb or anti-RSPO3 mAb; and ROR1-upregulated cancers with WNT/PCP and WNT/RTK signaling activation that can be treated with anti-ROR1 mAb, anti-ROR1 × CD3 bispecific antibody and ROR1 chimeric antigen receptor-modified T (CAR-T) cells (29). Genome sequencing, transcriptomic and/or immunohistochemical tests are necessary for the detection and subtyping of WNT signaling-driven cancers and subsequent determination of appropriate WNT signaling-targeted therapeutics (Fig. 3).

WNT signaling-targeted therapeutics are also applicable for combination therapies with tyrosine kinase inhibitors or immune checkpoint blockers as mentioned above (Fig. 3). Since resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors occur owing to multiple mechanisms, such as acquired drug-resistant mutations in targeted tyrosine kinases, EMT, activation of other tyrosine kinase signaling cascades to bypass targeted tyrosine kinases (4,162) and activation of WNT/β-catenin signaling cascade (Fig. 3), genomic, transcriptomic and/or immunohistochemical monitoring during tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment is also necessary to identify a subset of patients for combination therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitor and WNT signaling-targeted therapeutics. By contrast, because WNT signaling in the tumor microenvironment orchestrates antitumor immunity and immune tolerance in a context-dependent manner, immune monitoring is necessary to choose the appropriate WNT signaling-targeted therapeutics for cancer patients with immune evasion (Fig. 3).

Investigational genome medicine platforms based on nucleotide sequencing of transcribed regions are applicable for determination of targeted therapeutics only in 10–24% of cancer patients (163,164). Since alterations in non-transcribed regulatory regions also drive human carcinogenesis, whole-genome sequencing rather than whole- or partial-exome sequencing is preferable to improve the precision of genome-based medicine (4,165). In addition, organoid culture is a cutting-edge technology in the fields of oncology and stem cell biology (166–168), and organoid-based tests are also used for selecting targeted therapeutics (163,166). However, because tumor-stromal/immune interactions are not recapitulated in patient-derived organoid models, immunological monitoring in the tumor microenvironment is also necessary to improve genome-based medicine.

Together, these findings indicate that 'omics monitoring', including genome sequencing, transcriptomic, immunohistochemical and organoid-based tests, before and during treatment is necessary to choose and fine-tune WNT signaling-targeted therapeutics for the treatment of cancer patients (Fig. 3).

7. Conclusion

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are part of the tumor microenvironment and survive host defense or therapeutic insult through omics reprogramming. Aberrant WNT signaling activation in human cancers promotes CSC survival, bulk-tumor expansion and invasion/metastasis. Anti-FZD mAb, anti-ROR1 mAb, anti-RSPO3 mAb, PORCN inhibitors and β-catenin inhibitors are representative WNT signaling-targeted therapeutics in clinical trials or preclinical studies. WNT signaling-targeted therapeutics are applicable for combination therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors or immune checkpoint blockers. Omics monitoring is necessary for therapeutic optimization of WNT signaling-targeted therapy.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported in part by a grant-in-aid for the Knowledgebase Project from M. Katoh's Fund.

References

- 1.Visvader JE, Lindeman GJ. Cancer stem cells in solid tumours: Accumulating evidence and unresolved questions. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:755–768. doi: 10.1038/nrc2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medema JP. Cancer stem cells: The challenges ahead. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:338–344. doi: 10.1038/ncb2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abbaszadegan MR, Bagheri V, Razavi MS, Momtazi AA, Sahebkar A, Gholamin M. Isolation, identification, and characterization of cancer stem cells: A review. J Cell Physiol. 2017;232:2008–2018. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katoh M. Therapeutics targeting FGF signaling network in human diseases. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2016;37:1081–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Sousa e Melo F, Kurtova AV, Harnoss JM, Kljavin N, Hoeck JD, Hung J, Anderson JE, Storm EE, Modrusan Z, Koeppen H, et al. A distinct role for Lgr5(+) stem cells in primary and metastatic colon cancer. Nature. 2017;543:676–680. doi: 10.1038/nature21713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koury J, Zhong L, Hao J. Targeting signaling pathways in cancer stem cells for cancer treatment. Stem Cells Int. 2017;2017:2925869. doi: 10.1155/2017/2925869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McDonald OG, Li X, Saunders T, Tryggvadottir R, Mentch SJ, Warmoes MO, Word AE, Carrer A, Salz TH, Natsume S, et al. Epigenomic reprogramming during pancreatic cancer progression links anabolic glucose metabolism to distant metastasis. Nat Genet. 2017;49:367–376. doi: 10.1038/ng.3753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tam WL, Weinberg RA. The epigenetics of epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity in cancer. Nat Med. 2013;19:1438–1449. doi: 10.1038/nm.3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonzalez DM, Medici D. Signaling mechanisms of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Sci Signal. 2014;7:re8. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schreiber RD, Old LJ, Smyth MJ. Cancer immunoediting: Integrating immunity's roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science. 2011;331:1565–1570. doi: 10.1126/science.1203486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spranger S, Bao R, Gajewski TF. Melanoma-intrinsic β-catenin signalling prevents anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2015;523:231–235. doi: 10.1038/nature14404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cairns RA, Harris IS, Mak TW. Regulation of cancer cell metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:85–95. doi: 10.1038/nrc2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Brien CA, Pollett A, Gallinger S, Dick JE. A human colon cancer cell capable of initiating tumour growth in immunodeficient mice. Nature. 2007;445:106–110. doi: 10.1038/nature05372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamashita T, Ji J, Budhu A, Forgues M, Yang W, Wang HY, Jia H, Ye Q, Qin LX, Wauthier E, et al. EpCAM-positive hepatocellular carcinoma cells are tumor-initiating cells with stem/progenitor cell features. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1012–1024. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Todaro M, Gaggianesi M, Catalano V, Benfante A, Iovino F, Biffoni M, Apuzzo T, Sperduti I, Volpe S, Cocorullo G, et al. CD44v6 is a marker of constitutive and reprogrammed cancer stem cells driving colon cancer metastasis. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:342–356. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirsch D, Barker N, McNeil N, Hu Y, Camps J, McKinnon K, Clevers H, Ried T, Gaiser T. LGR5 positivity defines stem-like cells in colorectal cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35:849–858. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van der Flier LG, Sabates-Bellver J, Oving I, Haegebarth A, De Palo M, Anti M, Van Gijn ME, Suijkerbuijk S, Van de Wetering M, Marra G, et al. The intestinal Wnt/TCF signature. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:628–632. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yan KS, Janda CY, Chang J, Zheng GXY, Larkin KA, Luca VC, Chia LA, Mah AT, Han A, Terry JM, et al. Non-equivalence of Wnt and R-spondin ligands during Lgr5(+) intestinal stem-cell self-renewal. Nature. 2017;545:238–242. doi: 10.1038/nature22313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hilkens J, Timmer NC, Boer M, Ikink GJ, Schewe M, Sacchetti A, Koppens MAJ, Song JY, Bakker ERM. RSPO3 expands intestinal stem cell and niche compartments and drives tumorigenesis. Gut. 2017;66:1095–1105. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mani SK, Zhang H, Diab A, Pascuzzi PE, Lefrançois L, Fares N, Bancel B, Merle P, Andrisani O. EpCAM-regulated intra-membrane proteolysis induces a cancer stem cell-like gene signature in hepatitis B virus-infected hepatocytes. J Hepatol. 2016;65:888–898. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katoh M, Katoh M. WNT signaling pathway and stem cell signaling network. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4042–4045. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ranganathan P, Weaver KL, Capobianco AJ. Notch signalling in solid tumours: A little bit of everything but not all the time. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:338–351. doi: 10.1038/nrc3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katoh M, Nakagama H. FGF receptors: Cancer biology and therapeutics. Med Res Rev. 2014;34:280–300. doi: 10.1002/med.21288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lamb R, Bonuccelli G, Ozsvári B, Peiris-Pagès M, Fiorillo M, Smith DL, Bevilacqua G, Mazzanti CM, McDonnell LA, Naccarato AG, et al. Mitochondrial mass, a new metabolic biomarker for stem-like cancer cells: Understanding WNT/FGF-driven anabolic signaling. Oncotarget. 2015;6:30453–30471. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niehrs C. The complex world of WNT receptor signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:767–779. doi: 10.1038/nrm3470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holland JD, Klaus A, Garratt AN, Birchmeier W. Wnt signaling in stem and cancer stem cells. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2013;25:254–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rada P, Rojo AI, Offergeld A, Feng GJ, Velasco-Martín JP, González-Sancho JM, Valverde ÁM, Dale T, Regadera J, Cuadrado A. WNT-3A regulates an Axin1/NRF2 complex that regulates antioxidant metabolism in hepatocytes. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2015;22:555–571. doi: 10.1089/ars.2014.6040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Acebron SP, Niehrs C. β-catenin-independent roles of Wnt/LRP6 signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26:956–967. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katoh M, Katoh M. Molecular genetics and targeted therapy of WNT-related human diseases (Review) Int J Mol Med. 2017;40:587–606. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lui JH, Hansen DV, Kriegstein AR. Development and evolution of the human neocortex. Cell. 2011;146:18–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barker N. Adult intestinal stem cells: Critical drivers of epithelial homeostasis and regeneration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:19–33. doi: 10.1038/nrm3721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Camp JK, Beckers S, Zegers D, Van Hul W. Wnt signaling and the control of human stem cell fate. Stem Cell Rev. 2014;10:207–229. doi: 10.1007/s12015-013-9486-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang K, Wang X, Zhang H, Wang Z, Nan G, Li Y, Zhang F, Mohammed MK, Haydon RC, Luu HH, et al. The evolving roles of canonical WNT signaling in stem cells and tumorigenesis: Implications in targeted cancer therapies. Lab Invest. 2016;96:116–136. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2015.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qin L, Yin YT, Zheng FJ, Peng LX, Yang CF, Bao YN, Liang YY, Li XJ, Xiang YQ, Sun R, et al. WNT5A promotes stemness characteristics in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells leading to metastasis and tumorigenesis. Oncotarget. 2015;6:10239–10252. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Webster MR, Kugel CH, III, Weeraratna AT. The Wnts of change: How Wnts regulate phenotype switching in melanoma. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1856:244–251. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumawat K, Gosens R. WNT-5A: Signaling and functions in health and disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73:567–587. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-2076-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang MT, Holderfield M, Galeas J, Delrosario R, To MD, Balmain A, McCormick F. K-Ras promotes tumorigenicity through suppression of non-canonical Wnt signaling. Cell. 2015;163:1237–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Plaks V, Kong N, Werb Z. The cancer stem cell niche: How essential is the niche in regulating stemness of tumor cells? Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:225–238. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katoh M. FGFR inhibitors: Effects on cancer cells, tumor microenvironment and whole-body homeostasis (Review) Int J Mol Med. 2016;38:3–15. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2016.2620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bolli N, Avet-Loiseau H, Wedge DC, Van Loo P, Alexandrov LB, Martincorena I, Dawson KJ, Iorio F, Nik-Zainal S, Bignell GR, et al. Heterogeneity of genomic evolution and mutational profiles in multiple myeloma. Nat Commun. 2014;5:2997. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li S, Garrett-Bakelman FE, Chung SS, Sanders MA, Hricik T, Rapaport F, Patel J, Dillon R, Vijay P, Brown AL, et al. Distinct evolution and dynamics of epigenetic and genetic heterogeneity in acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Med. 2016;22:792–799. doi: 10.1038/nm.4125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abbosh C, Birkbak NJ, Wilson GA, Jamal-Hanjani M, Constantin T, Salari R, Le Quesne J, Moore DA, Veeriah S, Rosenthal R, TRACERx consortium et al. PEACE consortium: Phylogenetic ctDNA analysis depicts early-stage lung cancer evolution. Nature. 2017;545:446–451. doi: 10.1038/nature22364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tammela T, Sanchez-Rivera FJ, Cetinbas NM, Wu K, Joshi NS, Helenius K, Park Y, Azimi R, Kerper NR, Wesselhoeft RA, et al. A Wnt-producing niche drives proliferative potential and progression in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2017;545:355–359. doi: 10.1038/nature22334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weis SM, Cheresh DA. Tumor angiogenesis: Molecular pathways and therapeutic targets. Nat Med. 2011;17:1359–1370. doi: 10.1038/nm.2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mao Y, Keller ET, Garfield DH, Shen K, Wang J. Stromal cells in tumor microenvironment and breast cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2013;32:303–315. doi: 10.1007/s10555-012-9415-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Son B, Lee S, Youn H, Kim E, Kim W, Youn B. The role of tumor microenvironment in therapeutic resistance. Oncotarget. 2017;8:3933–3945. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anderson KG, Stromnes IM, Greenberg PD. Obstacles posed by the tumor microenvironment to T cell activity: A case for synergistic therapies. Cancer Cell. 2017;31:311–325. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Z, Liu P, Inuzuka H, Wei W. Roles of F-box proteins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:233–247. doi: 10.1038/nrc3700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Katoh M, Hirai M, Sugimura T, Terada M. Cloning, expression and chromosomal localization of Wnt-13, a novel member of the Wnt gene family. Oncogene. 1996;13:873–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Katoh M, Kirikoshi H, Terasaki H, Shiokawa K. WNT2B2 mRNA, up-regulated in primary gastric cancer, is a positive regulator of the WNT-β-catenin-TCF signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;289:1093–1098. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jiang H, Li F, He C, Wang X, Li Q, Gao H. Expression of Gli1 and Wnt2B correlates with progression and clinical outcome of pancreatic cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:4531–4538. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Steinhart Z, Pavlovic Z, Chandrashekhar M, Hart T, Wang X, Zhang X, Robitaille M, Brown KR, Jaksani S, Overmeer R, et al. Genome-wide CRISPR screens reveal a Wnt-FZD5 signaling circuit as a druggable vulnerability of RNF43-mutant pancreatic tumors. Nat Med. 2017;23:60–68. doi: 10.1038/nm.4219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seshagiri S, Stawiski EW, Durinck S, Modrusan Z, Storm EE, Conboy CB, Chaudhuri S, Guan Y, Janakiraman V, Jaiswal BS, et al. Recurrent R-spondin fusions in colon cancer. Nature. 2012;488:660–664. doi: 10.1038/nature11282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Lessons from hereditary colorectal cancer. Cell. 1996;87:159–170. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mazzoni SM, Fearon ER. AXIN1 and AXIN2 variants in gastrointestinal cancers. Cancer Lett. 2014;355:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chiche A, Moumen M, Romagnoli M, Petit V, Lasla H, Jézéquel P, de la Grange P, Jonkers J, Deugnier MA, Glukhova MA, et al. p53 deficiency induces cancer stem cell pool expansion in a mouse model of triple-negative breast tumors. Oncogene. 2017;36:2355–2365. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Valenti G, Quinn HM, Heynen GJJE, Lan L, Holland JD, Vogel R, Wulf-Goldenberg A, Birchmeier W. Cancer stem cells regulate cancer-associated fibroblasts via activation of Hedgehog signaling in mammary gland tumors. Cancer Res. 2017;77:2134–2147. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-3490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Katoh M. WNT/PCP signaling pathway and human cancer (Review) Oncol Rep. 2005;14:1583–1588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang Y, Mlodzik M. Wnt-Frizzled/planar cell polarity signaling: Cellular orientation by facing the wind (Wnt) Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2015;31:623–646. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100814-125315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Minegishi K, Hashimoto M, Ajima R, Takaoka K, Shinohara K, Ikawa Y, Nishimura H, McMahon AP, Willert K, Okada Y, et al. A Wnt5 activity asymmetry and intercellular signaling via PCP proteins polarize node cells for left-right symmetry breaking. Dev Cell. 2017;40:439–452.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu J, Mlodzik M. Wnt/PCP instructions for cilia in left-right asymmetry. Dev Cell. 2017;40:423–424. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang W, Runkle KB, Terkowski SM, Ekaireb RI, Witze ES. Protein depalmitoylation is induced by Wnt5a and promotes polarized cell behavior. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:15707–15716. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.639609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nishimura T, Honda H, Takeichi M. Planar cell polarity links axes of spatial dynamics in neural-tube closure. Cell. 2012;149:1084–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.De Marco P, Merello E, Piatelli G, Cama A, Kibar Z, Capra V. Planar cell polarity gene mutations contribute to the etiology of human neural tube defects in our population. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2014;100:633–641. doi: 10.1002/bdra.23255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gödde NJ, Pearson HB, Smith LK, Humbert PO. Dissecting the role of polarity regulators in cancer through the use of mouse models. Exp Cell Res. 2014;328:249–257. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Johnson R, Halder G. The two faces of Hippo: Targeting the Hippo pathway for regenerative medicine and cancer treatment. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:63–79. doi: 10.1038/nrd4161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang S, Chen L, Cui B, Chuang HY, Yu J, Wang-Rodriguez J, Tang L, Chen G, Basak GW, Kipps TJ. ROR1 is expressed in human breast cancer and associated with enhanced tumor-cell growth. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31127. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Anastas JN, Kulikauskas RM, Tamir T, Rizos H, Long GV, von Euw EM, Yang PT, Chen HW, Haydu L, Toroni RA, et al. WNT5A enhances resistance of melanoma cells to targeted BRAF inhibitors. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:2877–2890. doi: 10.1172/JCI70156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yu J, Chen L, Cui B, Widhopf GF, II, Shen Z, Wu R, Zhang L, Zhang S, Briggs SP, Kipps TJ. Wnt5a induces ROR1/ROR2 heterooligomerization to enhance leukemia chemotaxis and proliferation. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:585–598. doi: 10.1172/JCI83535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Green JL, Kuntz SG, Sternberg PW. Ror receptor tyrosine kinases: Orphans no more. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:536–544. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lu W, Yamamoto V, Ortega B, Baltimore D. Mammalian Ryk is a Wnt coreceptor required for stimulation of neurite outgrowth. Cell. 2004;119:97–108. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Petrova IM, Malessy MJ, Verhaagen J, Fradkin LG, Noordermeer JN. Wnt signaling through the Ror receptor in the nervous system. Mol Neurobiol. 2014;49:303–315. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8520-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Debebe Z, Rathmell WK. Ror2 as a therapeutic target in cancer. Pharmacol Ther. 2015;150:143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bicocca VT, Chang BH, Masouleh BK, Muschen M, Loriaux MM, Druker BJ, Tyner JW. Crosstalk between ROR1 and the Pre-B cell receptor promotes survival of t(1;19) acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:656–667. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hojjat-Farsangi M, Moshfegh A, Daneshmanesh AH, Khan AS, Mikaelsson E, Osterborg A, Mellstedt H. The receptor tyrosine kinase ROR1 - an oncofetal antigen for targeted cancer therapy. Semin Cancer Biol. 2014;29:21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gentile A, Lazzari L, Benvenuti S, Trusolino L, Comoglio PM. The ROR1 pseudokinase diversifies signaling outputs in MET-addicted cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:2305–2316. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yamaguchi T, Lu C, Ida L, Yanagisawa K, Usukura J, Cheng J, Hotta N, Shimada Y, Isomura H, Suzuki M, et al. ROR1 sustains caveolae and survival signalling as a scaffold of cavin-1 and caveolin-1. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10060. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li C, Wang S, Xing Z, Lin A, Liang K, Song J, Hu Q, Yao J, Chen Z, Park PK, et al. A ROR1-HER3-lncRNA signalling axis modulates the Hippo-YAP pathway to regulate bone metastasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2017;19:106–119. doi: 10.1038/ncb3464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dijksterhuis JP, Petersen J, Schulte G. WNT/Frizzled signalling: receptor-ligand selectivity with focus on FZD-G protein signalling and its physiological relevance: IUPHAR Review 3. Br J Pharmacol. 2014;171:1195–1209. doi: 10.1111/bph.12364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhan T, Rindtorff N, Boutros M. Wnt signaling in cancer. Oncogene. 2017;36:1461–1473. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gong B, Shen W, Xiao W, Meng Y, Meng A, Jia S. The Sec14-like phosphatidylinositol transfer proteins Sec14l3/SEC14L2 act as GTPase proteins to mediate Wnt/Ca(2+) signaling. eLife. 2017;6:e26362. doi: 10.7554/eLife.26362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kim S, Nie H, Nesin V, Tran U, Outeda P, Bai CX, Keeling J, Maskey D, Watnick T, Wessely O, et al. The polycystin complex mediates Wnt/Ca(2+) signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18:752–764. doi: 10.1038/ncb3363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ishitani T, Kishida S, Hyodo-Miura J, Ueno N, Yasuda J, Waterman M, Shibuya H, Moon RT, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Matsumoto K. The TAK1-NLK mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade functions in the Wnt-5a/Ca(2+) pathway to antagonize Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:131–139. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.1.131-139.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhang M, Hagenmueller M, Riffel JH, Kreusser MM, Bernhold E, Fan J, Katus HA, Backs J, Hardt SE. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II couples Wnt signaling with histone deacetylase 4 and mediates dishevelled-induced cardiomyopathy. Hypertension. 2015;65:335–344. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Scholz B, Korn C, Wojtarowicz J, Mogler C, Augustin I, Boutros M, Niehrs C, Augustin HG. Endothelial RSPO3 controls vascular stability and pruning through non-canonical WNT/Ca(2+)/NFAT signaling. Dev Cell. 2016;36:79–93. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang W, Snyder N, Worth AJ, Blair IA, Witze ES. Regulation of lipid synthesis by the RNA helicase Mov10 controls Wnt5a production. Oncogenesis. 2015;4:e154. doi: 10.1038/oncsis.2015.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Miyamoto DT, Zheng Y, Wittner BS, Lee RJ, Zhu H, Broderick KT, Desai R, Fox DB, Brannigan BW, Trautwein J, et al. RNA-Seq of single prostate CTCs implicates noncanonical Wnt signaling in antiandrogen resistance. Science. 2015;349:1351–1356. doi: 10.1126/science.aab0917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Blumenthal A, Ehlers S, Lauber J, Buer J, Lange C, Goldmann T, Heine H, Brandt E, Reiling N. The Wingless homolog WNT5A and its receptor Frizzled-5 regulate inflammatory responses of human mononuclear cells induced by microbial stimulation. Blood. 2006;108:965–973. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-5046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wang L, Steele I, Kumar JD, Dimaline R, Jithesh PV, Tiszlavicz L, Reisz Z, Dockray GJ, Varro A. Distinct miRNA profiles in normal and gastric cancer myofibroblasts and significance in Wnt signaling. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2016;310:G696–G704. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00443.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Aznar N, Midde KK, Dunkel Y, Lopez-Sanchez I, Pavlova Y, Marivin A, Barbazán J, Murray F, Nitsche U, Janssen KP, et al. Daple is a novel non-receptor GEF required for trimeric G protein activation in Wnt signaling. eLife. 2015;4:e07091. doi: 10.7554/eLife.07091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yu FX, Zhao B, Guan KL. Hippo pathway in organ size control, tissue homeostasis, and cancer. Cell. 2015;163:811–828. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hansen CG, Moroishi T, Guan KL. YAP and TAZ: A nexus for Hippo signaling and beyond. Trends Cell Biol. 2015;25:499–513. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hot B, Valnohova J, Arthofer E, Simon K, Shin J, Uhlén M, Kostenis E, Mulder J, Schulte G. FZD10-Gα13 signalling axis points to a role of FZD10 in CNS angiogenesis. Cell Signal. 2017;32:93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2017.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Takebe N, Miele L, Harris PJ, Jeong W, Bando H, Kahn M, Yang SX, Ivy SP. Targeting Notch, Hedgehog, and Wnt pathways in cancer stem cells: Clinical update. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2015;12:445–464. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kahn M. Wnt signaling in stem cells and tumor stem cells. Semin Reprod Med. 2015;33:317–325. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1558404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tai D, Wells K, Arcaroli J, Vanderbilt C, Aisner DL, Messersmith WA, Lieu CH. Targeting the WNT signaling pathway in cancer therapeutics. Oncologist. 2015;20:1189–1198. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gurney A, Axelrod F, Bond CJ, Cain J, Chartier C, Donigan L, Fischer M, Chaudhari A, Ji M, Kapoun AM, et al. Wnt pathway inhibition via the targeting of Frizzled receptors results in decreased growth and tumorigenicity of human tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:11717–11722. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120068109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Nielsen TO, Poulin NM, Ladanyi M. Synovial sarcoma: Recent discoveries as a roadmap to new avenues for therapy. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:124–134. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gong X, Azhdarinia A, Ghosh SC, Xiong W, An Z, Liu Q, Carmon KS. LGR5-targeted antibody-drug conjugate eradicates gastrointestinal tumors and prevents recurrence. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016;15:1580–1590. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Damelin M, Bankovich A, Bernstein J, Lucas J, Chen L, Williams S, Park A, Aguilar J, Ernstoff E, Charati M, et al. A PTK7-targeted antibody-drug conjugate reduces tumorinitiating cells and induces sustained tumor regressions. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aag2611. pii: eaag2611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zhang S, Cui B, Lai H, Liu G, Ghia EM, Widhopf GF, II, Zhang Z, Wu CC, Chen L, Wu R, et al. Ovarian cancer stem cells express ROR1, which can be targeted for anti-cancer-stem-cell therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:17266–17271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419599111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Storm EE, Durinck S, de Sousa e Melo F, Tremayne J, Kljavin N, Tan C, Ye X, Chiu C, Pham T, Hongo JA, et al. Targeting PTPRK-RSPO3 colon tumours promotes differentiation and loss of stem-cell function. Nature. 2016;529:97–100. doi: 10.1038/nature16466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Berger C, Sommermeyer D, Hudecek M, Berger M, Balakrishnan A, Paszkiewicz PJ, Kosasih PL, Rader C, Riddell SR. Safety of targeting ROR1 in primates with chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015;3:206–216. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Le PN, McDermott JD, Jimeno A. Targeting the Wnt pathway in human cancers: Therapeutic targeting with a focus on OMP-54F28. Pharmacol Ther. 2015;146:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cheng Y, Phoon YP, Jin X, Chong SY, Ip JC, Wong BW, Lung ML. Wnt-C59 arrests stemness and suppresses growth of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in mice by inhibiting the Wnt pathway in the tumor microenvironment. Oncotarget. 2015;6:14428–14439. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Poulsen A, Ho SY, Wang W, Alam J, Jeyaraj DA, Ang SH, Tan ES, Lin GR, Cheong VW, Ke Z, et al. Pharmacophore model for Wnt/Porcupine inhibitors and its use in drug design. J Chem Inf Model. 2015;55:1435–1448. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.5b00159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Langton PF, Kakugawa S, Vincent JP. Making, exporting, and modulating Wnts. Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26:756–765. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.DeBruine ZJ, Ke J, Harikumar KG, Gu X, Borowsky P, Williams BO, Xu W, Miller LJ, Xu HE, Melcher K. Wnt5a promotes Frizzled-4 signalosome assembly by stabilizing cysteine-rich domain dimerization. Genes Dev. 2017;31:916–926. doi: 10.1101/gad.298331.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Madan B, Ke Z, Harmston N, Ho SY, Frois AO, Alam J, Jeyaraj DA, Pendharkar V, Ghosh K, Virshup IH, et al. Wnt addiction of genetically defined cancers reversed by PORCN inhibition. Oncogene. 2016;35:2197–2207. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Chen B, Dodge ME, Tang W, Lu J, Ma Z, Fan CW, Wei S, Hao W, Kilgore J, Williams NS, et al. Small molecule-mediated disruption of Wnt-dependent signaling in tissue regeneration and cancer. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:100–107. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Proffitt KD, Madan B, Ke Z, Pendharkar V, Ding L, Lee MA, Hannoush RN, Virshup DM. Pharmacological inhibition of the Wnt acyltransferase PORCN prevents growth of WNT-driven mammary cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73:502–507. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Agarwal P, Zhang B, Ho Y, Cook A, Li L, Mikhail FM, Wang Y, McLaughlin ME, Bhatia R. Enhanced targeting of CML stem and progenitor cells by inhibition of porcupine acyltrans-ferase in combination with TKI. Blood. 2017;129:1008–1020. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-05-714089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Liu C, Yu X. ADP-ribosyltransferases and poly ADP-ribosylation. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2015;16:491–501. doi: 10.2174/1389203716666150504122435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kulak O, Chen H, Holohan B, Wu X, He H, Borek D, Otwinowski Z, Yamaguchi K, Garofalo LA, Ma Z, et al. Disruption of Wnt/β-catenin signaling and telomeric shortening are inextricable consequences of tankyrase inhibition in human cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2015;35:2425–2435. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00392-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wang W, Li N, Li X, Tran MK, Han X, Chen J. Tankyrase inhibitors target YAP by stabilizing Angiomotin family proteins. Cell Rep. 2015;13:524–532. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Nathubhai A, Haikarainen T, Koivunen J, Murthy S, Koumanov F, Lloyd MD, Holman GD, Pihlajaniemi T, Tosh D, Lehtiö L, et al. Highly potent and isoform selective dual site binding Tankyrase/Wnt signaling inhibitors that increase cellular glucose uptake and have antiproliferative activity. J Med Chem. 2017;60:814–820. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Quackenbush KS, Bagby S, Tai WM, Messersmith WA, Schreiber A, Greene J, Kim J, Wang G, Purkey A, Pitts TM, et al. The novel tankyrase inhibitor (AZ1366) enhances irinotecan activity in tumors that exhibit elevated tankyrase and irinotecan resistance. Oncotarget. 2016;7:28273–28285. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lau T, Chan E, Callow M, Waaler J, Boggs J, Blake RA, Magnuson S, Sambrone A, Schutten M, Firestein R, et al. A novel tankyrase small-molecule inhibitor suppresses APC mutation-driven colorectal tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2013;73:3132–3144. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Waaler J, Machon O, Tumova L, Dinh H, Korinek V, Wilson SR, Paulsen JE, Pedersen NM, Eide TJ, Machonova O, et al. A novel tankyrase inhibitor decreases canonical Wnt signaling in colon carcinoma cells and reduces tumor growth in conditional APC mutant mice. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2822–2832. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Arqués O, Chicote I, Puig I, Tenbaum SP, Argilés G, Dienstmann R, Fernández N, Caratù G, Matito J, Silberschmidt D, et al. Tankyrase inhibition blocks Wnt/β-catenin pathway and reverts resistance to PI3K and AKT inhibitors in the treatment of colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:644–656. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-3081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Huang SM, Mishina YM, Liu S, Cheung A, Stegmeier F, Michaud GA, Charlat O, Wiellette E, Zhang Y, Wiessner S, et al. Tankyrase inhibition stabilizes axin and antagonizes Wnt signalling. Nature. 2009;461:614–620. doi: 10.1038/nature08356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Schoumacher M, Hurov KE, Lehár J, Yan-Neale Y, Mishina Y, Sonkin D, Korn JM, Flemming D, Jones MD, Antonakos B, et al. Inhibiting Tankyrases sensitizes KRAS-mutant cancer cells to MEK inhibitors via FGFR2 feedback signaling. Cancer Res. 2014;74:3294–3305. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0138-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Wang H, Lu B, Castillo J, Zhang Y, Yang Z, McAllister G, Lindeman A, Reece-Hoyes J, Tallarico J, Russ C, et al. Tankyrase inhibitor sensitizes lung cancer cells to endothelial growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibition via stabilizing angiomotins and inhibiting YAP signaling. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:15256–15266. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.722967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Scarborough HA, Helfrich BA, Casás-Selves M, Schuller AG, Grosskurth SE, Kim J, Tan AC, Chan DC, Zhang Z, Zaberezhnyy V, et al. AZ1366: An inhibitor of tankyrase and the canonical Wnt pathway that limits the persistence of non-small cell lung cancer cells following EGFR inhibition. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:1531–1541. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Pelay-Gimeno M, Glas A, Koch O, Grossmann TN. Structure-based design of inhibitors of protein-protein interactions: Mimicking peptide binding epitopes. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54:8896–8927. doi: 10.1002/anie.201412070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Hwang SY, Deng X, Byun S, Lee C, Lee SJ, Suh H, Zhang J, Kang Q, Zhang T, Westover KD, et al. Direct targeting of β-catenin by a small molecule stimulates proteasomal degradation and suppresses oncogenic Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Cell Rep. 2016;16:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.05.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Mahmoudi T, Li VS, Ng SS, Taouatas N, Vries RG, Mohammed S, Heck AJ, Clevers H. The kinase TNIK is an essential activator of Wnt target genes. EMBO J. 2009;28:3329–3340. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Lee Y, Jung JI, Park KY, Kim SA, Kim J. Synergistic inhibition effect of TNIK inhibitor KY-05009 and receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor dovitinib on IL-6-induced proliferation and Wnt signaling pathway in human multiple myeloma cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8:41091–41101. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Tan Z, Chen L, Zhang S. Comprehensive modeling and discovery of mebendazole as a novel TRAF2- and NCK-interacting kinase inhibitor. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33534. doi: 10.1038/srep33534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Fiskus W, Sharma S, Saha S, Shah B, Devaraj SG, Sun B, Horrigan S, Leveque C, Zu Y, Iyer S, et al. Pre-clinical efficacy of combined therapy with novel β-catenin antagonist BC2059 and histone deacetylase inhibitor against AML cells. Leukemia. 2015;29:1267–1278. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Trautmann M, Sievers E, Aretz S, Kindler D, Michels S, Friedrichs N, Renner M, Kirfel J, Steiner S, Huss S, et al. SS18-SSX fusion protein-induced Wnt/β-catenin signaling is a therapeutic target in synovial sarcoma. Oncogene. 2014;33:5006–5016. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Kim JY, Lee HY, Park KK, Choi YK, Nam JS, Hong IS. CWP232228 targets liver cancer stem cells through Wnt/β-catenin signaling: A novel therapeutic approach for liver cancer treatment. Oncotarget. 2016;7:20395–20409. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Nagaraj AB, Joseph P, Kovalenko O, Singh S, Armstrong A, Redline R, Resnick K, Zanotti K, Waggoner S, DiFeo A. Critical role of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in driving epithelial ovarian cancer platinum resistance. Oncotarget. 2015;6:23720–23734. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Fang L, Zhu Q, Neuenschwander M, Specker E, Wulf-Goldenberg A, Weis WI, von Kries JP, Birchmeier W. A small-molecule antagonist of the β-catenin/TCF4 interaction blocks the self-renewal of cancer stem cells and suppresses tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2016;76:891–901. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Sukhdeo K, Mani M, Zhang Y, Dutta J, Yasui H, Rooney MD, Carrasco DE, Zheng M, He H, Tai YT, et al. Targeting the β-catenin/TCF transcriptional complex in the treatment of multiple myeloma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7516–7521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610299104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Zhou H, Mak PY, Mu H, Mak DH, Zeng Z, Cortes J, Liu Q, Andreeff M, Carter BZ. Combined inhibition of β-catenin and Bcr-Abl synergistically targets tyrosine kinase inhibitor-resistant blast crisis chronic myeloid leukemia blasts and progenitors in vitro and in vivo. Leukemia. 2017 Apr 18; doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.87. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Takada K, Zhu D, Bird GH, Sukhdeo K, Zhao JJ, Mani M, Lemieux M, Carrasco DE, Ryan J, Horst D, et al. Targeted disruption of the BCL9/β-catenin complex inhibits oncogenic Wnt signaling. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:148ra117. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Wang Q, Amato SP, Rubitski DM, Hayward MM, Kormos BL, Verhoest PR, Xu L, Brandon NJ, Ehlers MD. Identification of phosphorylation consensus sequences and endogenous neuronal substrates of the psychiatric risk kinase TNIK. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;356:410–423. doi: 10.1124/jpet.115.229880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Coluccia AM, Vacca A, Duñach M, Mologni L, Redaelli S, Bustos VH, Benati D, Pinna LA, Gambacorti-Passerini C. Bcr-Abl stabilizes β-catenin in chronic myeloid leukemia through its tyrosine phosphorylation. EMBO J. 2007;26:1456–1466. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Nakayama S, Sng N, Carretero J, Welner R, Hayashi Y, Yamamoto M, Tan AJ, Yamaguchi N, Yasuda H, Li D, et al. β-catenin contributes to lung tumor development induced by EGFR mutations. Cancer Res. 2014;74:5891–5902. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Kajiguchi T, Katsumi A, Tanizaki R, Kiyoi H, Naoe T. Y654 of β-catenin is essential for FLT3/ITD-related tyrosine phosphorylation and nuclear localization of β-catenin. Eur J Haematol. 2012;88:314–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2011.01738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Jin B, Ding K, Pan J. Ponatinib induces apoptosis in imatinib-resistant human mast cells by dephosphorylating mutant D816V KIT and silencing β-catenin signaling. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13:1217–1230. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Fernández-Sánchez ME, Barbier S, Whitehead J, Béalle G, Michel A, Latorre-Ossa H, Rey C, Fouassier L, Claperon A, Brullé L, et al. Mechanical induction of the tumorigenic β-catenin pathway by tumour growth pressure. Nature. 2015;523:92–95. doi: 10.1038/nature14329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Zhao Y, Masiello D, McMillian M, Nguyen C, Wu Y, Melendez E, Smbatyan G, Kida A, He Y, Teo JL, et al. CBP/catenin antagonist safely eliminates drug-resistant leukemiainitiating cells. Oncogene. 2016;35:3705–3717. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Smyth MJ, Ngiow SF, Ribas A, Teng MW. Combination cancer immunotherapies tailored to the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016;13:143–158. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Palucka AK, Coussens LM. The basis of oncoimmunology. Cell. 2016;164:1233–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Zarour HM. Reversing T-cell dysfunction and exhaustion in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:1856–1864. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Chen DS, Mellman I. Elements of cancer immunity and the cancer-immune set point. Nature. 2017;541:321–330. doi: 10.1038/nature21349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Inman BA, Longo TA, Ramalingam S, Harrison MR. Atezolizumab: A PD-L1-blocking antibody for bladder cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:1886–1890. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Kim ES. Avelumab: First global approval. Drugs. 2017;77:929–937. doi: 10.1007/s40265-017-0749-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Syed YY. Durvalumab: First global approval. Drugs. 2017;77:1369–1376. doi: 10.1007/s40265-017-0782-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Zaretsky JM, Garcia-Diaz A, Shin DS, Escuin-Ordinas H, Hugo W, Hu-Lieskovan S, Torrejon DY, Abril-Rodriguez G, Sandoval S, Barthly L, et al. Mutations associated with acquired resistance to PD-1 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:819–829. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1604958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Shin DS, Zaretsky JM, Escuin-Ordinas H, Garcia-Diaz A, Hu-Lieskovan S, Kalbasi A, Grasso CS, Hugo W, Sandoval S, Torrejon DY, et al. Primary resistance to PD-1 blockade mediated by JAK1/2 mutations. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:188–201. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Anagnostou V, Smith KN, Forde PM, Niknafs N, Bhattacharya R, White J, Zhang T, Adleff V, Phallen J, Wali N, et al. Evolution of neoantigen landscape during immune checkpoint blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:264–276. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-0828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Huang AC, Postow MA, Orlowski RJ, Mick R, Bengsch B, Manne S, Xu W, Harmon S, Giles JR, Wenz B, et al. T-cell invigoration to tumour burden ratio associated with anti-PD-1 response. Nature. 2017;545:60–65. doi: 10.1038/nature22079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Manguso RT, Pope HW, Zimmer MD, Brown FD, Yates KB, Miller BC, Collins NB, Bi K, LaFleur MW, Juneja VR, et al. In vivo CRISPR screening identifies Ptpn2 as a cancer immunotherapy target. Nature. 2017;547:413–418. doi: 10.1038/nature23270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Holtzhausen A, Zhao F, Evans KS, Tsutsui M, Orabona C, Tyler DS, Hanks BA. Melanoma-derived Wnt5a promotes local dendritic-cell expression of IDO and immunotolerance: Opportunities for pharmacologic enhancement of immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015;3:1082–1095. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Hugo W, Zaretsky JM, Sun L, Song C, Moreno BH, Hu-Lieskovan S, Berent-Maoz B, Pang J, Chmielowski B, Cherry G, et al. Genomic and transcriptomic features of response to anti-PD-1 therapy in metastatic melanoma. Cell. 2016;165:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.D'Amico L, Mahajan S, Capietto AH, Yang Z, Zamani A, Ricci B, Bumpass DB, Meyer M, Su X, Wang-Gillam A, et al. Dickkopf-related protein 1 (Dkk1) regulates the accumulation and function of myeloid derived suppressor cells in cancer. J Exp Med. 2016;213:827–840. doi: 10.1084/jem.20150950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Fulciniti M, Tassone P, Hideshima T, Vallet S, Nanjappa P, Ettenberg SA, Shen Z, Patel N, Tai YT, Chauhan D, et al. Anti-DKK1 mAb (BHQ880) as a potential therapeutic agent for multiple myeloma. Blood. 2009;114:371–379. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-191577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Bendell JC, Murphy JE, Mahalingam D, Halmos B, Sirard CA, Landau SB, Ryan DP. A Phase 1 study of DKN-01, an anti-DKK1 antibody, in combination with paclitaxel in patients with DKK1 relapsed or refractory esophageal cancer or gastro-esophageal junction tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(Suppl 4):S111. doi: 10.1200/jco.2016.34.4_suppl.111. http://ascopubs.org/doi/abs/10.1200/jco.2016.34.4_suppl.111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]