Abstract

This narrative review examines the changes required in dietary behaviours to address the current global burden of disease resulting from diet-associated cardiometabolic dysfunction. Beginning with known relationships between nutritional factors and health outcomes, the review identifies a number of problems with current dietary behaviours, using examples from the Australian context. Implications for practice are then discussed drawing on insights from research in dietary trials. From a concerted research effort across the globe, the effects of foods, food components and dietary patterns on cardiometabolic parameters have been reasonably well exposed. The evidence base for these effects underpins dietary guidelines, which aim to meet nutritional requirements and protect against cardiometabolic disease. Thus foods recommended in dietary guidelines tend to be consistent with research that identifies foods that appear protective and those that appear detrimental to health. The need for dietary behaviour change is apparent through analyses that have exposed increasing consumption of detrimental foods, despite the availability of healthy foods. However, behaviour change is a complex area, and where weight loss is also required, there is high level evidence that interdisciplinary efforts combining diet, physical activity and psychological support are warranted. Insights from dietary trials and research indicate that focussing on foods and dietary patterns is integral to the specific dietary change required for health outcomes, but social and behavioural factors will influence the achievement of these changes.

Keywords: Diet, Nutritional quality, Lifestyle-related disease

Introduction

Dietary guidelines refer to food choices and dietary patterns that meet requirements for essential nutrients and protect against the development of chronic lifestyle-related disease.1 With the current prevalence of global obesity,2 dietary guidance must also consider energy levels that support achievement or maintenance of a healthy body weight. This means that foods in the diet must have a high nutrient density in order to deliver required nutrients without excess energy. In the case of some nutrients, such as sodium and saturated fatty acids, excessive consumption may also need to be curtailed due to associations with hypertension and cholesterol levels respectively.1 This narrative review examines the changes required in dietary behaviours to address the current global burdens of disease resulting from diet-associated cardiometabolic dysfunction. It examines the known relationships between nutritional quality and health outcomes, outlines current problems with dietary behaviours, referencing Australian data for an example, and discusses implications for practice drawing on insights from experiences with dietary trials.

Nutritional quality and health outcomes

Promoting dietary behaviour change first requires a sound evidence base for the relationship between dietary factors and disease. This evidence base exposes both beneficial and detrimental factors. When people consume food, multiple chemical compounds are delivered to the body and interact with various physiological and metabolic processes.3 A substantial amount of research has been conducted on the way in which foods and food components influence pathways and mechanisms of action related to cardiovascular and metabolic health. A recent review on dietary and policy priorities for cardiovascular disease, diabetes and obesity noted that to date a number of dietary factors are known to influence health.4 These included 11 different foods which appeared to have a positive impact (fruit, vegetables, nuts, wholegrains, legumes, fish, shellfish, yoghurt, cheese, milk, vegetable oils) and a couple of others which may be detrimental (refined grains, processed meats). Food components and beverages which would be beneficial (such as phytochemicals and coffee) or detrimental (such as excess sodium and sugary beverages) were also identified. Overall, however, the impact of food preparation, food processing and dietary patterns needed to be considered. The pathways and mechanisms by which these dietary factors exerted their influence included glucose-insulin homeostasis, blood lipids, blood pressure, and the functions of the endothelial, cardiac and adipocyte systems, the gut microbiome, systemic inflammation and hunger and satiety.4

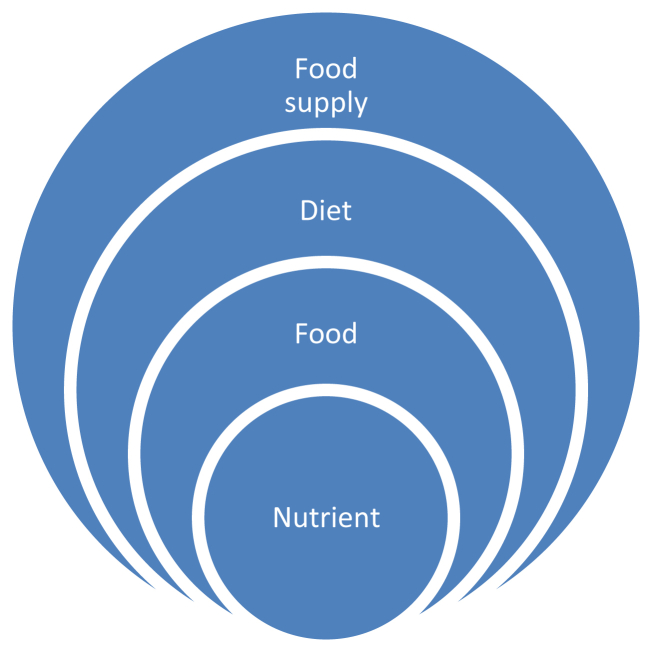

Some of these dietary factors are whole foods, some are food components and others are dietary patterns. They are studied through laboratory experiments, observational research on population eating patterns, and clinical trials. The dietary variable may be defined at the food, dietary pattern or nutrient level, but in reality, they are all inter-related (Fig. 1). A low fat diet, for example, may appear as a dietary pattern, but it achieves its characteristics profile by virtue of its nutrient (fat content). Likewise, this nutrient content is achievable because of a set of food choices, in this case with a focus on low fat foods. Appreciating the connection between nutrients, foods and whole diets is a critical component of the development of dietary guidelines.1

Fig. 1.

Inter-relationship between nutrients, foods, diet and the food supply.

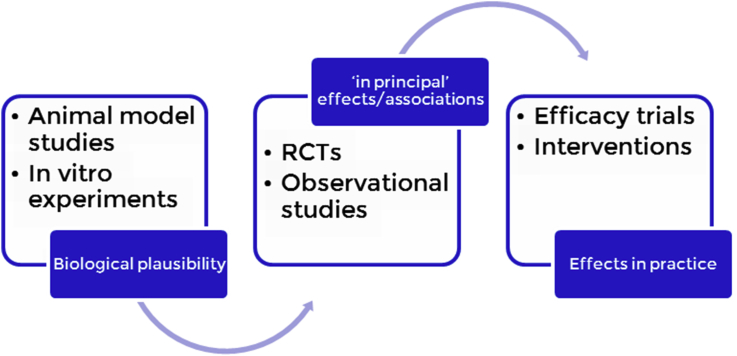

Research on the effect of dietary components on health outcomes can vary in nature. In establishing the evidence for health claims on foods, for example, randomised controlled trials provide direct evidence of effects, observational studies indicate associations and mechanistic research confirms the plausibility of the diet-disease relationship.5 Research from randomised controlled trials and observational studies provides “in principle” evidence of the diet-disease relationship. To translate this to practice, efficacy trials are required to test adherence and achievement of health outcomes under conditions of usual care (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Value chain for research on dietary factors and health [Adapted from Ref. 1]. RCT: randomized controlled trial.

Dietary behaviour change

There is evidence across the globe that dietary behaviours need to change to reduce the risk of cardiometabolic disorders.6 Using a wide range of data sources including nationally representative dietary surveys adjusted for total energy intake, this analysis identified 10 healthy items, as foods (wholegrains, fruits, vegetables, fish, nuts and seeds, beans and legumes, and milk), and nutrients (dietary fibre, total polyunsaturated fatty acids, and plant omega-3 fatty acids) in contrast to 7 unhealthy items, also identified as foods (sugary beverages, unprocessed red meats and processed meats) and nutrients (saturated fatty acids, trans fatty acids, cholesterol, sodium). Overall, the analysis showed that the consumption of unhealthy food items has increased across the globe, at the same time as healthy items, and with some variation. Using three different models for dietary patterns based on (a) high consumption of healthy items, (b) low consumption of unhealthy items and (c) a combined model of all items, the analysis was able to display a distribution of diet quality scores across the globe. The first two analyses allowed for separate observations of trends in healthy vs. unhealthy food choices, which if just considered together may mask deleterious trends in diet quality. For example, the diet quality analysis based on fewer unhealthy items shows Australia as being amongst the worst in the world, while not showing a substantial decline in overall diet quality.

The categories of foods used in these analyses align with categories of advice in the Australian Dietary Guidelines (ADG),7 which state to enjoy nutritious foods [vegetables, legumes, beans, fruit, cereals (mostly wholegrain/high fibre), lean meat/poultry/fish/eggs/tofu/nuts/seeds/legumes/beans, and milk/yoghurt/cheese/alternatives] and limit foods and beverages with high amounts of saturated fat, salt and added sugar, as well as alcohol consumption. The nutritious (nutrient rich, healthy) foods formed the basis for the dietary modelling underpinning the dietary guidelines, and translated into the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating (AGHE) which provided further guidance on relative amounts and types of foods to consume.8 Dietary modelling referred to Foundation diets, which were designed to ensure adequate intakes of essential nutrients within energy constraints for any given age and size.9 The foods included in the dietary modelling were relatively unprocessed with minimal amounts of added salt and sugar. Amounts of foods containing high levels of saturated fat were constrained. This distinction between foods explains the use of the terms “core” foods (healthy, nutrient dense foods used in dietary modelling for dietary guidance) and “discretionary” foods (unhealthy foods, nutrient poor and/or with high levels of added salt and sugar). Examples of discretionary foods are given in the ADG as cakes, pastries, processed meats, confectionary, many commercial fried foods, and sugar sweetened beverages.

The extent to which dietary change is now required by the Australian population is reflected in analyses of the recent Australian Health Survey which suggests that 35% of energy consumed comes from discretionary food categories.10 The nature of the problem and challenges for dietary behaviour change are also exposed. Despite advice to consume wholegrain cereals and vegetables, the major sources of discretionary foods are based on processed foods such as cereal foods and cereal food products, and vegetable products and dishes. This means that the nutritional quality of healthy foods is being compromised by food preparation and processing factors. In this case it is not enough to suggest that people consume more vegetables and grains, there is a need to move closer to cuisine elements in the diet and preparation methods for healthy foods. This was demonstrated in the PREDIMED trial,11 which tested the impact of a culturally recognised Mediterranean diet on cardiovascular disease risk reduction in regions across Spain.

In other settings the significance of consuming individual foods in relation to health outcomes has been identified within populations. For example, weight gain over a 4 year period was positively associated with intake of potato chips (1.69 lb), potatoes (1.28 lb), sugar sweetened beverages (1.00 lb), unprocessed red meat (0.95 lb) and processed red meats (0.93 lb) in an analysis involving data on 120,877 U.S. healthy non-obese adults (from the Nurse Health and Health Professional Studies). On the other hand, weight gain was inversely associated with consumption of vegetables (−0.22 lb), wholegrains (−0.37 lb), fruits (−0.49 lb), nuts (−0.57 lb) and yoghurt (−0.82 lb) (P < 0.005 for each comparison).12 This suggests attention to individual foods is warranted.

At the population level this means developing educational materials with a shift in focus to healthy dietary patterns and working with industry to ensure pre-prepared foods retain the nutritional quality of core foods. At the individual level, encouraging dietary behaviour change, however, requires more than advice on healthy foods, as psychological factors will influence food choice regardless of knowledge about food. In addition, information alone does not bring about change. New approaches, such as the use of healthy conversation skills in community nutrition education have shown to be of benefit.13

Implications for practice

In the practice context, health outcomes are achieved when the healthcare team works together to support behaviour change. For example, in the case of obesity management in clinical practice, there is high level evidence that a combination of diet, physical activity and behavioural support will produce greater weight loss than single lifestyle interventions alone.14 In our dietary trials we have found that personal goals of participants do not always align with clinical outcomes, whereas external influences, such as family issues, having an impact on personal goals.15 This means that translating dietary messages needs to take into account the circumstances of a person's life. Supporting dietary change requires help to identify issues with food choices and may benefit from approaches such as healthy conversation techniques.13

Making successful dietary changes can also be associated with achievement of outcomes. In another study, we found that early weight loss and age predict retention in weight loss trials.16 We found that those that lost less than 2% of body weight after 1 month were 4 times more likely to drop out, and those less than 50-year age were twice as likely to drop out. In the longer term, being older and having a lower BMI to start with meant a person was more likely to have rapid and continuing weight loss over 1 year.17 Thus, individual and social circumstances, the extent of the health problem and evidence of progress all appear important in establishing change.

Behaviour change can result in improved dietary patterns that lead to better health outcomes and the best results may be seen in those starting with the worst eating habits. Using cluster analysis to identify healthy and unhealthy dietary patterns at baseline in two weight loss trials, we found that people who entered the study making unhealthy food choices (Cluster 2) did better than those who were already choosing primarily healthy foods (Cluster 1). After 3 months of intervention, Cluster 2 reported consuming less energy (−5317 kJ; P < 0.01) and achieved a greater weight loss (−5.6 kg; P < 0.05) than Cluster 1.18 In this case, removing unhealthy food items from usual eating patterns appeared to enable greater weight loss, than simply eating less healthy food. This means that in practice, both the amount and type of food consumed are important considerations for dietary change.

The significance of consuming individual foods and dietary patterns for better health outcomes has been identified within populations, but the relationships are also relevant to clinical cohorts. A meta-analysis of studies on dietary patterns and systolic blood pressure found overall protective effects [−4.06 mmHg (−5.29, −2.83)] from healthy dietary patterns across the globe, represented by the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet, Mediterranean diet, Nordic diet and Tibetan diet.19 This suggests dietary patterns also play an important role. The foods identified in these studies and dietary patterns remained consistent in a study of a clinical cohort (n = 328) attending a lifestyle intervention trial.20 In this study, dietary intakes reported at baseline were analyzed using Principle Component Analysis (PCA) and this produced 6 dietary patterns, but only the one characterised by nuts, seeds, fruit and fish was associated with lower systolic blood pressure (R2 = 0.234; P < 0.0005), diastolic blood pressure (R2 = 0.259; P < 0.0005), and urinary sodium:potassium ratio (R2 = 0.100; P < 0.0005).21 From these 3 studies alone, fruit, nuts, and fish stand out. These and other core foods are recommended in dietary guidelines.

Conclusion

There are many layers that need to be considered in creating dietary behaviour change to improve nutritional quality and health outcomes. The first is the evidence of the relationship between dietary factors and health outcomes (both beneficial and deleterious) and an understanding of food sources of nutrients (supporting nutritional quality). This sets the standard for the required nature and extent of change in food consumption patterns. This standard needs to be adequately resourced with high quality informative research and health practitioners with defined competencies. The second is the behaviour change itself. Once it is clear “what” needs to be done, the issue of “how” change may occur is another matter. At the population level, among many things, it relates to food security and the quality of the food supply, and at the clinical level it is at least an interdisciplinary exercise supporting individuals in making appropriate changes within their complex life circumstances.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Tapsell reports grants from California Walnut Commission (No. 6393) and International Tree Nut Council (No. 2016-R02) outside the submitted work.

Edited by Pei-fang Wei

Footnotes

This paper was presented at the 2016 International Conference on Weight Management, Lifestyle and Cardio-Metabolic disease. November 5–6, 2016, Shanghai, China.

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Medical Association.

References

- 1.Tapsell L.C., Neale E.P., Satija A., Hu F.B. Foods, nutrients, and dietary patterns: interconnections and implications for dietary guidelines. Adv Nutr. 2016;7:445–454. doi: 10.3945/an.115.011718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ng M., Fleming T., Robinson M. Global, regional and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:766–781. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trujillo E., Davis C., Milner J. Nutrigenomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and the practice of dietetics. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:403–413. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mozaffarian D. Dietary and policy priorities for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity: a comprehensive review. Circulation. 2016;133:187–225. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Food and Drug Administration . January 2009. Guidance for Industry: Evidence Based Review System for the Scientific Evaluation of Health Claims – Final.https://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceRegulation/GuidanceDocumentsRegulatoryInformation/ucm073332.htm#system Accessed March 21, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imamura F., Micha R., Khatibzadeh S. Dietary quality among men and women in 187 countries in 1990 and 2010: a systematic assessment. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:e132–e142. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70381-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian Dietary Guidelines. https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/. Accessed March 23, 2017.

- 8.Australian Government. National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian Guide to Healthy Eating. https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/guidelines/australian-guide-healthy-eating. Accessed March 23, 2017.

- 9.Dietitians Association of Australia. A Modelling System to Inform the Revision of the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelines-publications/n55. Accessed March 23, 2017.

- 10.Australian Health Survey Nutrition First Results, 2011–12. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4364.0.55.007main+features12011-12. Accessed March 21, 2017.

- 11.Estruch R., Ros E., Salas-Salvadó J. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1279–1290. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mozaffarian D., Hao T., Rimm E.B., Willett W.C., Hu F.B. Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2392–2404. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Black C., Lawrence W., Cradock S. Healthy conversation skills: increasing competence and confidence in front-line staff. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17:700–707. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012004089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Health and Medical Research Council . National Health and Medical Research Council; Melbourne: 2013. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Overweight and Obesity in Adults, Adolescents and Children in Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McMahon A.T., O'Shea J., Tapsell L., Williams P. What do the terms wellness and wellbeing mean in dietary practice: an exploratory qualitative study examining women's perceptions. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2014;27:401–410. doi: 10.1111/jhn.12165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Batterham M.J., Tapsell L.C., Charlton K.E. Predicting dropout in dietary weight loss trials using demographic and early weight change characteristics: implications for trial design. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2016;10:189–196. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Batterham M., Tapsell L.C., Charlton K.E. Baseline characteristics associated with different BMI trajectories in weight loss trials: a case for better targeting of interventions. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70:207–211. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2015.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grafenauer S.J., Tapsell L.C., Beck E.J., Batterham M.J. Baseline dietary patterns are a significant consideration in correcting dietary exposure for weight loss. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67:330–336. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2013.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ndanuko R.N., Tapsell L.C., Charlton K.E., Neale E.P., Batterham M.J. Dietary patterns and blood pressure in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Adv Nutr. 2016;7:76–89. doi: 10.3945/an.115.009753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tapsell L.C., Lonergan M., Martin A., Batterham M.J., Neale E.P. Interdisciplinary lifestyle intervention for weight management in a community population (HealthTrack study): study design and baseline sample characteristics. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;45:394–403. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ndanuko R.N., Tapsell L.C., Charlton K.E., Neale E.P., Batterham M.J. Associations between dietary patterns and blood pressure in a clinical sample of overweight adults. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117:228–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2016.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]