Abstract

Many working women will experience sexual harassment at some point in their careers. While some report this harassment, many leave their jobs to escape the harassing environment. This mixed-methods study examines whether sexual harassment and subsequent career disruption affect women’s careers. Using in-depth interviews and longitudinal survey data from the Youth Development Study, we examine the effect of sexual harassment for women in the early career. We find that sexual harassment increases financial stress, largely by precipitating job change, and can significantly alter women’s career attainment.

Keywords: sexual harassment, gender, work, young adulthood, attainment

Feminist scholars argue that sexual harassment causes considerable harm to women as a group (MacKinnon 1979). Harassment undermines women’s workplace authority, reduces them to sexual objects, and reinforces sexist stereotypes about appropriate gender behavior (McLaughlin, Uggen, and Blackstone 2012; Quinn 2002). At the individual level, however, targets who pursue legal action must demonstrate that employers or harassers caused measurable harm. Previous studies document the psychological harm of sexual harassment (Fitzgerald et al. 1997; Gruber and Fineran 2008; Houle et al. 2011), yet little research documents the tangible economic costs for working women. Because many targets quit their jobs rather than continue working in a harassing work environment, sexual harassment may have long-term consequences for women’s careers. Throughout their twenties, young adults experience frequent job change as they find their footing on the “long and twisting path to adulthood” (Settersten and Ray 2010, 19). As a result, measuring the direct and indirect effects of sexual harassment for women’s careers is difficult. Quantitative studies, though predominantly cross-sectional, establish significant associations between harassment and several work outcomes, such as job satisfaction and turnover. Careers are often messy, however, with workers holding multiple jobs simultaneously or experiencing rapid job turnover on a monthly or weekly basis. While quantitative methods can help identify the effect of harassment on women’s career trajectories, qualitative analyses are needed to show precisely how and why sexual harassment affects women’s unfolding career stories.

In this mixed-methods study, we examine the relationship between sexual harassment and women’s career attainment. Although harassment occurs in a variety of institutional contexts, including housing (Tester 2008) and educational settings (Hand and Sanchez 2000; Kalof et al. 2001), this paper focuses exclusively on workplace sexual harassment. Using survey data from the Youth Development Study (YDS), we examine whether sexual harassment is associated with immediate financial stress and longer-term economic attainment through the mid- to late thirties. Then, we analyze interviews conducted with a subset of YDS respondents to identify how harassment influences women’s long-term career trajectories.

THE COSTS OF SEXUAL HARASSMENT

Sexual harassment can have deleterious consequences for mental and physical health (McDonald 2012; Willness, Steel, and Lee 2007). Houle and colleagues (2011), for example, point to the longevity of these effects, as targets of harassment continue to report depressive symptoms nearly a decade later. The same study links sexual harassment to other aspects of mental health, including anger and self-doubt, which likely influence targets’ future employment experiences. Given these serious health effects, it is not surprising that sexual harassment affects immediate work outcomes, such as reduced job satisfaction (Chan et al. 2008; Fitzgerald et al. 1997; Laband and Lentz 1998), increased absenteeism and work withdrawal (Merkin 2008; U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board 1988), and deteriorating relationships with co-workers (Gruber and Bjorn 1982; Loy and Stewart 1984). Organizational commitment may also wane if employers fail to adequately address harassers or protect targets (Willness et al. 2007). In light of evidence that sexual harassment is often an ongoing occurrence (Uggen and Blackstone 2004), occurring alongside other forms of workplace abuse (Lim and Cortina 2005), targets may hold employers responsible for enabling a toxic organizational culture. When employers fail to take action, or when targets are labeled “troublemakers” who harm productivity or the organization’s reputation, loyalty and trust may also be jeopardized.

Beyond these work outcomes, sexual harassment costs the federal government millions. Costs between 1985 and 1987 were estimated at $267 million before litigation and settlement fees (U.S. Merit Board Systems Protection 1988), over $200 million of which was due to reduced productivity. In 2015, sexual harassment charges filed with the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (2015) cost organizations and harassers $46 million, excluding monetary damages awarded through litigation. Such estimates dramatically understate the total costs to employers, as most harassment goes unreported. Despite these attempts to monetize the organizational costs of harassment, few researchers have attempted to estimate the economic and career costs for individual targets.

GENDER, EARLY CAREER INTERRUPTIONS, AND LONG-TERM ATTAINMENT

The gender gap in earnings has remained unchanged for over a decade, with women’s 2012 median earnings equaling roughly 81 percent that of men’s (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2013). Occupational segregation, the concentration of men and women into different types of jobs, is a strong contributor to this earnings inequality (Gauchat, Kelly, and Wallace 2012; Ranson and Reeves 1996). Despite gains in educational attainment, women remain overrepresented in “pink-collar” occupations (e.g., retail, food services, and care work) that are typically characterized by low prestige and menial pay. Some women prefer such work. Others are pushed out of masculine fields by discriminatory policies and practices that disadvantage women (Ecklund, Lincoln, and Tansey 2012; Prokos and Padavic 2005). Indeed, Rosenberg and colleagues’ (1993) study of women lawyers describes discrimination and harassment as tactics that subvert women’s professional standing. Cha and Weeden (2014) similarly point to gendered patterns of “overwork,” particularly in professional and managerial occupations, to explain the gender wage gap. Such gendered norms and practices are embedded within institutions, reifying existing status hierarchies (Acker 1990; Lopez, Hodson, and Roscigno 2009; Roscigno 2011).

Sexual harassment is well-documented across many fields but women who work in men-dominated occupations and industries experience higher rates (Fitzgerald et al. 1997; Gruber 1998; McLaughlin et al. 2012). The likelihood of harassment also increases with exposure to a wider range of employees (Chamberlain et al. 2008; De Coster, Estes, and Mueller 1999), and is higher among single women (De Coster et al. 1999; Rosenberg et al. 1993), highly educated women (De Coster et al. 1999), and women in positions of authority (Chamberlain et al. 2008; McLaughlin et al. 2012). Because sexual harassment forces some women out of jobs, it likely influences their career attainment (Blackstone, Uggen, and McLaughlin 2009; Lopez et al. 2009). Numerous studies link voluntary and involuntary career interruptions to significant earnings losses (Brand 2015; Couch and Placzek 2010; Theunissen et al. 2011). Hijzen and colleagues (2010) estimate income losses in the United Kingdom ranging from 18 to 35 percent following job displacement associated with firm closure, and losses of 14 to 25 percent among those who suffer mass layoff. Brand and Thomas (2015, 986) argue that “job displacement is a precipitating life event that entails a sequence of stressful experiences,” from unemployment, to job search, retraining, and reemployment, “often in a job of inferior quality and lower earnings relative to the job lost.” Previous research on gender, work, and job disruption has yet to considered sexual harassment, which may be a major scarring event that disrupts “the usual trajectory of steady jobs with career ladders that normally propels wage growth” (Western 2006, 109).

By severing ties with employers, workers also relinquish firm-specific human capital, which is closely linked to earnings (Kletzer 1998). Further, harassment targets may have trouble obtaining references from managers and co-workers. Those who find a new job may discover lack of seniority limits earnings growth and increases vulnerability to layoffs and career instability. Career interruption may be especially costly in the early career. Most young adults settle into work and family roles in their thirties (Arnett 2004). While sexual banter, crude jokes, and flirting are commonplace in adolescent jobs, they become more disruptive as workers gain experience (Blackstone, Houle, and Uggen 2014). By their early thirties, many who once viewed sexualized workplace interactions as acceptable or even pleasurable expect to be treated professionally, and are more likely to view harassment as a serious workplace problem (Blackstone et al. 2014). If sexual harassment forces women to leave their jobs, it may derail their long-term career opportunities. We thus hypothesize that sexual harassment increases subjective financial stress (Ullah 2001) and has consequences for women’s career trajectories. We expect that job disruption accounts for a significant portion of these effects.

METHODS

We analyze survey and interview data from the Youth Development Study (YDS), a prospective, longitudinal cohort study that began in 1988, when participants were 9th graders in the St. Paul, Minnesota public school system. A total of 1,139 parents and children consented to take part in the study, and 1,105 responded to in-school surveys during the first year. The initial panel was representative of the total population of St. Paul ninth graders who attended public schools (Mortimer 2003). Participants were surveyed in schools for the first four years (1988–1992), and by mail 15 more times through 2011.

Because women are more likely than men to be targeted (Uggen and Blackstone 2004; Welsh 1999), to perceive sexualized behaviors as offensive (Padavic and Orcutt 1997; Quinn 2002), and to label their experiences as sexual harassment (Marshall 2005; McLaughlin et al. 2012), we limit our analyses to employed women who were potential harassment targets in 2003 (n=364). The response rate for women in the YDS panel was 74 percent in 2005, when we measure the effects of harassment on financial stress. We find no evidence of differential attrition between women who experienced sexual harassment and those who did not. The detailed information on sexual harassment and comprehensive longitudinal data on women’s careers allows for unique analyses that would not be possible using other datasets; however, the sample is relatively small, and data is collected from a single cohort originating from a single U.S. community. Thus, we urge caution in generalizing to other cohorts of women in other contexts.

To understand the context of harassment in their careers, we interviewed 33 YDS respondents (14 men, 19 women) who reported harassing behavior “at any job held during high school” or “since high school” on their 1999 survey, the first year harassment questions were included in the YDS. Our analysis here includes data from the 19 interviews with women. We mailed letters to 86 women who reported harassment in their surveys, inviting them for a face-to-face interview about “experiences with problems in the workplace, including sexual harassment,” noting they would be “asked questions about how people may have made you feel uncomfortable at work by joking about you, staring at you, touching you, or anything else that may have made you uncomfortable.”

Of those invited, 30 women expressed interest by sharing their telephone number via return postcard. We called all 30 for interviews. Some did not respond, others declined to participate, some provided non-working numbers, and others did not show up for interviews. There were no other significant differences between interview participants and those who were invited but did not participate, except that interviewees were somewhat more likely to be exposed to offensive materials at work.

We asked participants questions about their careers, including relationships with co-workers, explanations for career transitions, and harassing experiences. They were paid $40 to do a 60–90 minute interview at a location of their choosing (usually their home). Given the sensitive nature of our questions, we shared a list of local and national sexual violence resources during the informed consent process at the outset of each interview. We also reminded participants that they could skip any question they preferred not to answer or end the interview at any time. Interviews were conducted in 2002–2003, when participants were 28 to 30 years old. All 19 women interviewed identified as straight, and all but two identified as white.

Quantitative Measures

Our dependent variable is financial stress, which measures stress in “meeting your financial obligations” in the past year. This outcome was self-reported in 2005, with response options ranging from 1 (“not at all stressful”) to 7 (“extremely stressful”). In 2003, YDS respondents reported whether they had experienced workplace sexual harassment during the past year. Modeled after the Inventory of Sexual Harassment (Gruber 1992) and Sexual Experiences Questionnaire (Fitzgerald et al. 1988), items included (1) unwanted touching; (2) offensive jokes, remarks, or gossip directed at you; (3) offensive jokes, remarks, or gossip about others; (4) direct questioning about your private life; (5) staring or invasion of your personal space; (6) staring or leering at you in a way that made you uncomfortable; and, (7) pictures, posters, or other materials that you found offensive.1

Although experiencing any of these behaviors could have serious effects, we operationalize severe sexual harassment as unwanted touching and/or experiencing four or more different harassing behaviors in the past year. With this definition, we can be reasonably confident that behaviors meet legal definitions of hostile work environment sexual harassment and that financial stress can be tied to specific work experiences. Using these criteria, 11 percent of working women were harassed in 2003.

Exiting a harassing work environment may be costly for women’s long-term careers if they sacrifice firm-specific tenure and human capital, lose access to social networks, experience gaps in employment, or cannot find comparable work. Job change is coded as “1” if respondents reported a new job in 2004 or 2005. We lag this measure to ensure that sexual harassment occurs prior to starting a new job. As shown in Table 1, 56 percent of women began a new job in the two years after reporting on harassment.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Women in the Youth Development Study

| Description | Coding | Mean or Proportion | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial Stress (2005) | Stress felt in meeting financial obligations in past year | 1=not at all 7=extremely |

4.341 | 1.784 |

| Sexual Harassment (2003) | Unwanted touching or at least 4 other behaviors in past year | 0=No, 1=Yes | .107 | |

| Job Change (2004–2005) | Started new job in 2004–2005 | 0=No, 1=Yes | .563 | |

| Primary Job Characteristics (2003) | ||||

| Supervisory Authority | Supervise others on job | 0=No, 1=Yes | .274 | |

| Work Hours | Hours in past week | 36.575 | 9.928 | |

| Logged Employees | Logged number employees | 4.312 | 1.817 | |

| Industry Percent Women | Percent women in industry | 56.779 | 20.748 | |

| Temporary Job | Job through temp agency, seasonal, or limited-term | 0=No, 1=Yes | .123 | |

| Long-Term Career Job | Job will probably continue as long-term career | 0=No, 1=Yes | .483 | |

| Individual Characteristics (2003) | ||||

| White | Self-reported race | 0=Non-white, 1=White | .788 | |

| Years Education | Years completed | 14.500 | 1.770 | |

| Married/Cohabiting | Relationship status | 0=No, 1=Yes | .698 | |

| Mother | At least one child | 0=No, 1=Yes | .610 | |

| Recent Birth 2003–2005 |

birth, adopted, stepchild, or other child born 2003–2005 | 0=No, 1=Yes | .262 | |

| Negative Life Event 2003–2005 |

Experienced (1) serious injury/illness; (2) breakup of serious romantic relationship; (3) jail; (4) assault, battery, robbery, or rape; and/or (5) death of spouse/partner | 0=No, 1=Yes | .451 | |

Note: Descriptive statistics reported for analytic sample (the 364 women who responded to workplace sexual harassment questions in 2003). Due to missing data, sample attrition, and women leaving the labor force, sample size varies across measures (min=234, max=364).

We control for six additional job characteristics linked to earnings and harassment. Supervisory authority is a dichotomous measure of whether participants supervise others (27 percent). Work hours reflects the hours worked in the past week for respondents’ primary job (mean=37). Logged number of employees is reported for the primary job’s worksite (mean=4.3 or 73 employees). We derived the percentage of women in respondents’ primary job industry from U.S. Census estimates (U.S. Department of Labor 2003). On average, women worked in gender-balanced industries (57 percent women), though industry composition ranged from 9 to 96 percent women. Twelve percent of women were temporary workers, whose positions were contracted through a temporary agency, seasonal, or limited by term or contract. Because workers whose jobs do not align with their long-term career goals may quit for reasons unrelated to the harassment, our models adjust for whether women expected their primary job to continue as a long-term career (48 percent).

We also consider individual and family characteristics affecting financial stress and earnings. Race is an important control in this analysis, as it is associated with both sexual harassment (Texeira 2002; Welsh et al. 2006) and earnings inequality (Greenman and Xie 2008; Xu and Leffler 1992). Race is measured dichotomously, as whites comprise 79 percent of our analytic sample.2 Although variations in employment conditions and harassment experiences among women of color are important empirical questions, our data do not permit these analyses. Years of education ranges from 10 to 20 (mean=14.5 years). We also adjust for whether women are married or cohabiting (yes coded as 1) and whether they are mothers (yes coded as 1) in 2003, at age 29–30. In 2003, 70 percent of the working women were married or cohabiting and 61 percent had children. The recent birth of a child can lead to job exit, financial stress, and reduced attainment (Even 1987). Thus, we control for having a new child (including birth, adopted, stepchildren, and other children) born 2003–2005, in addition to having a child prior to 2003. Experiencing incarceration, divorce, and other negative life events3 may also increase financial stress. Twenty-six percent of women had a child born 2003–2005 and 45 percent of women reported at least one negative life event during this period.

Method of Analysis

We first use OLS regression to model financial stress. We include four-step formal mediation analyses (Baron and Kenny 1986) to test whether job change mediates the relationship between sexual harassment and financial stress. This process (1) establishes that harassment affects job change (path a); (2) establishes a direct effect of harassment on economic attainment (path c); (3) verifies that job change influences economic attainment, net of harassment (path b); and finally, (4) calculates the reduction of the effect of harassment on the attainment outcome, net of job change (path ć).

We next present qualitative findings from our interviews with 19 women participants. We used NVivo software to organize, manage, interpret, and analyze the interview transcripts, which ranged from 20 to 60 pages. Our qualitative analysis proceeded in several stages. We first identified passages that helped contextualize our quantitative findings. We then re-examined each transcript to code for tangible and intangible outcomes associated with harassing experiences. In addition, we coded all passages referring to earnings, economic concerns, and finances more generally (e.g., bills and expenditures). To ensure that findings resembled patterns we would find using inductive techniques, we brought in the third author, who had not participated in the first rounds of coding. In this phase, every quote addressing outcomes of harassment was coded. This process yielded patterns similar to those we had identified in our initial rounds of coding. Many interviewees described harassing experiences and job transitions that had occurred several years prior. To validate retrospective accounts, we verified the timing of job transitions and wages using employment history calendars in our survey data. These additional details are integrated throughout discussion of the qualitative data. Taken together, this mixed-methods approach helps identify how sexual harassment influences women’s attainment. To protect confidentiality, we use pseudonyms for individuals and employers.

SEXUAL HARASSMENT, JOB CHANGE, AND FINANCIAL STRESS

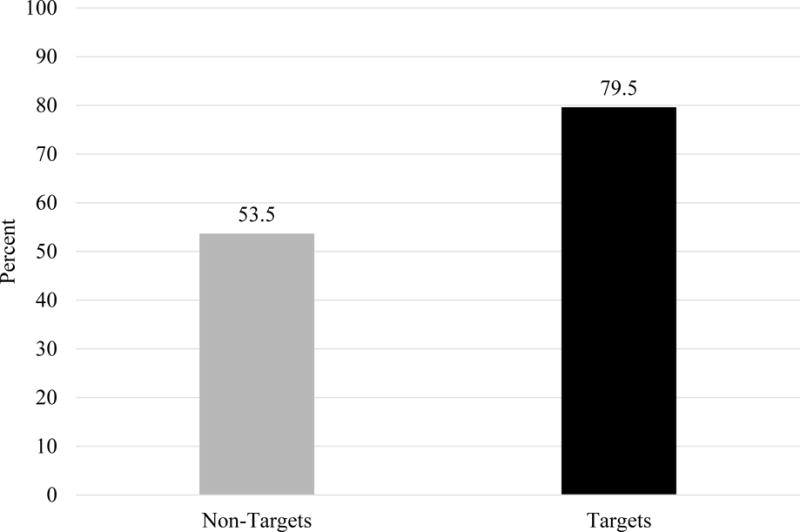

In bivariate analyses, women who experienced unwanted touching or multiple harassing behaviors in 2003 reported significantly greater financial stress in 2005 (t=−2.664, p≤.01). Some of this strain may be due to career disruption, as harassment targets were especially likely to change jobs. As shown in Figure 1, 79 percent of targets as compared to 54 percent of other working women started a new primary job in either 2004 or 2005 (X2=9.53, p≤.01). We next estimate multivariate models to learn whether these patterns may be attributed to differences in work, individual, or family characteristics.

FIGURE 1.

Percentage of Working Women Reporting Job Change (2003–2005)

In Model 1 of Table 2, harassment targets reported significantly greater financial stress. This effect is comparable to experiencing other negative life events—serious injury or illness, incarceration, assault—suggesting that sexual harassment may have analogous “scarring” effects (Western 2006). Although other job characteristics were less predictive, several individual and family characteristics were associated with financial stress. Married/cohabiting women felt less stress than single/non-cohabiting women in meeting financial obligations; mothers reported greater financial stress than childless women. As the analyses are limited to working women, such aggregate differences are likely linked to the greater earnings and financial stability afforded to dual-earner families (89 percent of romantic partners worked at least part-time). The effect of recent births is nonsignificant, though some new mothers likely left the labor force completely.

TABLE 2.

Ordinary Least Squares Estimates of Financial Stress (2005)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Sexual Harassment (2003) | .720* | .511 |

| (.320) | (.324) | |

| Job Change (2004–2005) | .582** | |

| (.200) | ||

| Work Characteristics | ||

| Supervisory Authority | −.299 | −.315 |

| (.220) | (.218) | |

| Work Hours | .001 | .004 |

| (.010) | (.010) | |

| Logged Employees | −.046 | −.038 |

| (.055) | (.054) | |

| Industry Percent Women | .001 | .001 |

| (.005) | (.005) | |

| Temporary Job | −.258 | −.332 |

| (.303) | (.300) | |

| Long-Term Career Job | −.311 | −.283 |

| (.201) | (.199) | |

| Individual & Family Characteristics | ||

| White | .059 | .096 |

| (.246) | (.243) | |

| Years Education | −.067 | −.073 |

| (.062) | (.061) | |

| Married/Cohabiting | −.654** | −.665** |

| (.238) | (.234) | |

| Mother | 1.066*** | 1.069*** |

| (.223) | (.220) | |

| Recent Birth (2003–2005) | −.013 | .049 |

| (.248) | (.245) | |

| Negative Life Event (2003–2005) | .685*** | .658*** |

| (.205) | (.203) | |

| Constant | 4.995*** | 4.604*** |

| (1.093) | (1.087) | |

| Observations | 286 | 286 |

| Adjusted R-squared | .149 | .172 |

Note: Unstandardized coefficients; standard errors in parentheses.

p≤0.05,

p≤0.01,

p≤0.001, two-tailed test.

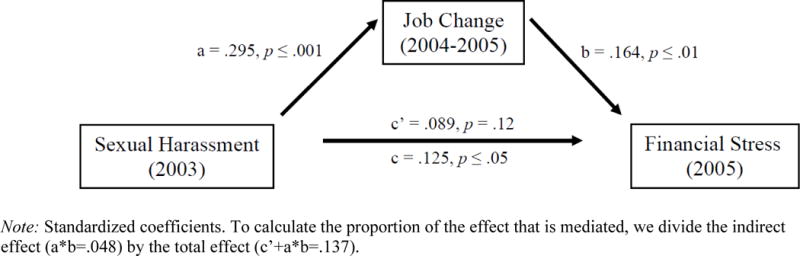

In Model 2 of Table 2, we test whether the increased financial stress reported by harassment targets can be attributed to their greater likelihood of changing jobs. Analyzing consecutive waves of YDS data, we can establish clear temporal order between sexual harassment (2003), job change (2004–2005), and financial stress (2005). In addition to having a strong direct effect on financial stress (β=.582, p≤.01), job change reduces the effect of harassment below standard significance levels. Following Baron and Kenny (1986), we calculate that 35 percent of the total effect of sexual harassment on financial stress is mediated through job change (dividing the indirect effect (a*b=.048) by the total effect (c’+a*b=.137)). Targets of sexual harassment were 6.5 times as likely as non-targets to change jobs in 2004–2005, net of the other variables in our model (unstandardized β=1.878; standardized regression coefficients are shown in Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. Mediational Model of Sexual Harassment, Job Change, and Financial Stress.

Note: Standardized coefficients. To calculate the proportion of the effect that is mediated, we divide the indirect effect (a*b=.048) by the total effect (c’+a*b=.137).

Sensitivity Analyses

In our previous analyses, we chose a high threshold to assess sexual harassment – unwanted touching or at least four different harassing behaviors – in an effort to address the effects of severe and pervasive workplace harassment. We therefore replicated Table 2 using more inclusive measures, thus increasing the size of the “harassed” group. Specifically, we examine: (1) an additive index of the number of harassing behaviors, ranging from 0 to 7 (mean = 1.2); (2) unwanted touching or at least three different harassing behaviors, a slightly lower threshold of severe harassment (reported by 19 percent); and (3) subjectively labeling harassing experiences as sexual harassment (12 percent). Findings for the lower threshold harassment measure and additive index were robust to our primary analyses; however, subjective sexual harassment did not predict financial stress (not shown, available by request).

Additionally, our quantitative analyses identify whether harassment occurred in 2003, yet we do not know if those labeled “non-targets” experienced workplace harassment in the following year. Although the specific items differ slightly from those asked in 2003, some sexual harassment items were also available in 2004, at age 30 or 31. To test the robustness of our earlier findings, we examined whether harassment in 2004 or across either year influenced 2005 financial stress. Results for 2004 sexual harassment were comparable to the models presented above. Moreover, the coefficient for severe harassment grew in both size and magnitude when 2003 and 2004 measures were combined.

We also looked at men’s experiences. When men are included in our models, our main findings are largely robust but coefficients are weaker in magnitude. When models are separated by gender, however, sexual harassment in 2003 does not predict men’s financial stress. This finding is consistent with research showing that men are likely to obtain relatively high paying jobs even when their school or work trajectory is disrupted (Dwyer, Hodson, and McCloud 2012).

Together, these analyses suggest that sexual harassment in the early thirties can have consequences for women’s attainment. Next, we draw on our qualitative data to better understand this relationship. Because interviews were conducted in 2003 and encompassed participants’ entire work history, these findings also shed light on whether and how harassment experienced in the early to mid-twenties similarly impacts women’s careers.

MECHANISMS LINKING SEXUAL HARASSMENT AND ECONOMIC ATTAINMENT

“I had one month off. I quit, and I didn’t have a job. That’s it, I’m outta here. I’ll eat rice and live in the dark if I have to.” – Lisa

Exiting a harassing work environment is one option along a continuum of mobilization responses (Blackstone et al. 2009). But, as Lisa, a project manager at an advertising agency, suggests, many women preferred this response. Megan, a waitress, believed that targets do not report harassers except as a last resort when “they can’t financially afford to quit their job.” Two of her co-workers filed a sexual harassment claim after facing inappropriate comments and touching from two line cooks. Megan says her co-workers feared their harassers, if confronted, would sabotage customers’ orders and the tips that made up a large proportion of their earnings.

Rachel quit her fast food job after a co-worker grabbed her from behind and “rubbed up against her.” Rachel’s attorney advised that she did not have a strong case unless it occurred again and her employer failed to take action, a risk Rachel was unwilling to take. Troubled by the harassing experience, Rachel was equally disappointed by her employer’s response, who did not fire the harasser until after she consulted an attorney: “This man had already done it to [my co-worker], but then I go and take it to a lawyer and then they do something…After that happened, I was just totally disgusted and I quit.”

Exiting a harassing environment can lead to significant losses. As Lisa’s opening quote reveals, she was willing to sacrifice basic necessities, including electricity and a balanced diet, to escape an intolerable work environment. Even when targets are able to find work right away, harassment contributed to financial strain for several interview participants, consistent with our quantitative findings. Interviewees attributed this to unemployment and career uncertainty, diminished hours or pay, and the anxiety associated with starting over in a new position.

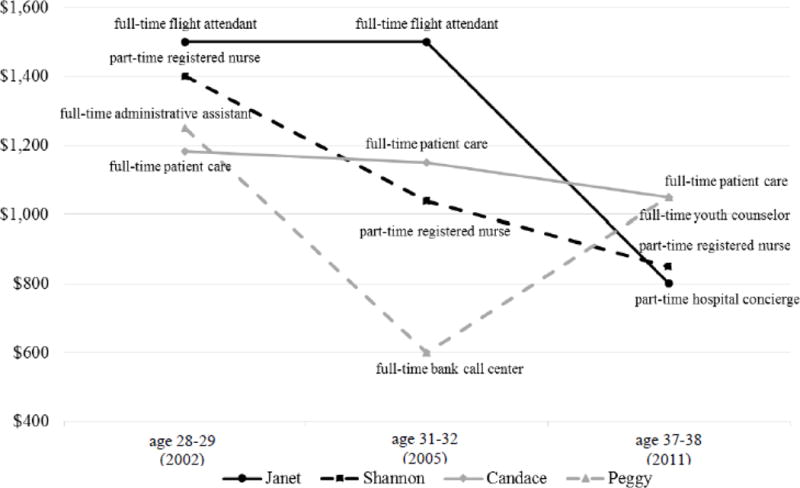

While interviewees described the immediate effects of job exit on earnings and financial stress, we were also interested in how women’s careers may have shifted after experiencing sexual harassment. Using the longitudinal survey data to analyze targets’ complex work histories, we found that job change, industry change, and reduced work hours were common. Although some found an equivalent or higher-paying position, some women’s earnings fell precipitously in subsequent years. To illustrate these patterns, Figure 3 shows earnings trajectories for four YDS participants who experienced harassment in 2003.

FIGURE 3.

Illustrative Work Trajectories of Sexual Harassment Targets

While working as a flight attendant in 2003, Janet reported offensive jokes, questions about her private life, and unwanted touching. Although her earnings remained stable during her 8-years with the airline, they declined precipitously in 2006 when she began work as a hospital concierge. Shannon, a registered nurse, cut her weekly hours from 28 to 12 in early 2005, and then to less than 8 hours later that year. In contrast to Janet and Shannon, Candace worked full-time, in the same career, throughout young adulthood. Although she also reported multiple harassing behaviors—including offensive jokes, questioning about her private life, and uncomfortable staring—she did not define her experiences as sexual harassment. Still, she reported them to her supervisor and changed employers in 2004, reporting a 10 percent reduction in hourly pay. It took Candace until 2009 to match her pre-harassment (2002) hourly wage.

Lastly, Peggy reported a significant detour on her path to steady, long-term work. Combining two low wage jobs, she worked 60 hours per week in 2002. She was sexually harassed while working full-time as a family support specialist at a community center in 2003. Peggy left this position after 13 months, briefly working at a bank call center in 2005, before returning to her previous industry for the remainder of the study period. While most women’s earnings increased throughout young adulthood, the stalled or declining earnings these and many other harassment targets experienced may be due to leaving a bad situation or reduced human and firm-specific capital.4

Sexual Harassment and the Reduction of Human Capital

“I didn’t want to work for Venture Module. I had no interest in computer hardware whatsoever. And I took the position there because I felt like I had to. I went to a position where I am pretty much solitary. I work by myself. Which is the way that I want it.” – Pam

In her early twenties, Pam worked as a part-time filing clerk at a bank. There for four years, she was promoted several times, eventually earning almost $9 per hour as a full-time accountant. The following exchange with her co-worker, Paul, occurred shortly before she left the company:

[Paul] goes, “Pam, do you ever wonder why Bill uses the photocopier over here when he has one right in front of his desk?” And I said, “No. Why?” I didn’t know. He goes, “Oh you’re kidding me.” And I go, “What are you talking about?” I had no idea what he was talking about. And he says, he just started talking about things. He goes, “You’ve never noticed this? You’ve never noticed he stares at you?”… he would like put his hand out like this [mimics cupping buttocks] after I’d walk by.… there was stuff I didn’t, it was worse, I didn’t even know about. He had drawn pictures of me on the computer and had showed people.

Bill was reprimanded after Pam learned his behavior, but like Rachel, Pam was disappointed that her employer “never said, ‘We’ve handled it.’ They never said, ‘We’ll put aside your fears’ or you know, ‘Do you feel comfortable?’ They never did any of that.” As a result, Pam took a part-time job and reduced her hours at the bank. Her survey responses confirm that she worked 20 hours per week at a bakery for $6.50 per hour, eventually working with a temp agency while seeking a permanent job.

The experience scarred Pam, leaving her distrusting of others. She received support from her co-workers after the harassment was exposed, yet none of the colleagues who corroborated the harassment confronted Bill as his behavior worsened. Pam saw this as a betrayal and said the experience and another incident at a subsequent job, “marred me because I don’t trust people that I work with.” Despite her lack of interest in computers, Pam “wanted to find a position where I wasn’t out in the public eye.” Her preferred isolation limited Pam’s career options and earning potential. Her career trajectory, as described in her surveys, changed dramatically after leaving her position at the bank. After working there from 1992 to 1996, she bounced between nine different employers over four years in a series of short-term jobs paying between $20,000 and $30,000 per year.

Hannah’s experience shows how misogynistic work environments influence attainment. Her coworkers at an internet advertising agency were a “litany of frat boys” who would tell homophobic jokes and send office-wide emails that included “horrible diatribes, like literally shocking, shocking, shocking emails.” Although she worked hard, Hannah’s career stalled because she refused to participate in the crude and derogatory workplace culture: “In the end it was really a bad move for me because I didn’t get promoted, I got passed over all the time because I was seen as like not a team player, because I disengaged.” Like many women, Hannah found herself between a rock and a hard place – either participate in the misogynistic culture at work (only to be cast aside or ignored because of her gender) or speak up and resist, leaving no chance for moving up in the company.

Although Hannah was never personally targeted, she devoted two years to a company where she was an outsider. Unlike the cases above, she could not attribute her lack of advancement to severing ties with the company. Instead, her employers were unwilling to invest in her future. Lisa, too, saw her responsibilities wane after she exposed a hostile work environment. Her relationships with supervisors and co-workers weakened, she felt heavily surveilled, and her duties were reduced because, “I’m sure some of it was, ‘We just can’t trust her.’” As long as Lisa remained complicit in the offensive workplace culture, her position was secure. After challenging the harassment, Lisa recalled, “I would never become friends with these people, my boss would never be a mentor, I would never, you know, have any relationship with these people. So that was rough and finally I just quit.” Lisa was ostracized by co-workers who, consistent with past research, viewed harassing behaviors as trivial and failed to support targets (Loy and Stewart 1984; Quinn 2002). Though hired by a competitor company after one month unemployed, she lost earnings because the original firm “compensated its employees monetarily spectacularly.” After these jobs, her earnings dropped precipitously, working as a waitress and a personal shopper.

As individual employees, Hannah and Lisa were limited in their ability to transform their workplace cultures. No longer willing to tolerate a harassing work environment, Hannah thought “it wouldn’t be worth me trying to spend all my energy to change that culture, when it would be so much easier for me to find a better place where I fit in.” Like Pam, Hannah’s experience at the internet advertising agency changed her outlook. Instead of preferring isolation, however, she simply avoided “toxic” work environments. In workplaces like Hannah’s and Lisa’s, sexual harassment is one of several practices that limit women’s advancement and cast them as outsiders (Acker 1990; Denissen and Saguy 2014; Reskin and McBrier 2000). Jordan, a police officer, told us of women officers who quit the force when sexually harassed. One woman “pulled over a stolen vehicle and nobody came” although other officers were “eating breakfast literally like six blocks from where she was.” This practice of ignoring calls for backup echoes Texeira’s (2002) study of sexual harassment among African American women police officers defined as “troublemakers.”

While Jordan’s colleague was abandoned in the line of duty, Angela was berated by five salesmen at a car dealership, forfeiting her commission, and leaving the room in tears:

It was like $200, you know, it was a big deal, but it was not worth the emotional distress …He did take the commission, but they kept me in the room for another fifteen minutes… physically blocked the door, and they just kind of lectured at me…I held it together for as long as I could…once they had seen the tears, they had gotten the reaction out of me that they wanted and at that point they kind of disbanded and let me out.

After four months at the dealership, Angela took a pay cut to work as a teacher’s assistant, earning $8 per hour. Although sexual harassment is conceptually isolable from gender discrimination and workplace bullying, these behaviors often overlap in practice. Many interviewees described toxic work environments where harassment combined with other practices to legitimate organizational hierarchies and exclude women. These stories illustrate why Hannah, and other women, opt to switch careers over “bargaining with patriarchy” (Kandiyoti 1988). Indeed, sexual harassment and mistreatment of women in masculine workplaces contributes to gender segregation and gender gaps in attainment.

Erin’s case shows another way harassment impacts earnings. After working as a full-time custodian for 18 months, she was sexually harassed by a recent hire who “had a problem with always wanting to hug on me and touch me and say things he shouldn’t have been saying.” She described leering, unwelcome touching, requests to hang photos of her in his locker, and his remark that, “he’d been looking in the Victoria’s Secret catalogue and was wondering what I’d look like in a pair of thong underwear.” Twice, “he actually unsnapped my bra…He would laugh about it and say, ‘Ha ha, lookit. I can unsnap your bra with one finger.’” Ignoring her demands that he stop, Erin’s harasser attempted to “throw me in the swimming pool … and he’d wrap his arms around me and try to hug me.” Erin stopped working after her harasser injured her back. She explained, “He picked me up, he bounced me, and he popped something in my lower back…They told me it was [a strained lumbar], but it feels like there’s something actually pinched in there.” At the time of her interview, several months after the harassment began, Erin was receiving workers’ compensation which provided only two-thirds of her wages. She was angry about her losses, explaining that “I only make enough to cover exactly what everything is here. And I have no money left over… I’m probably gonna have to rob Peter to pay Paul.” Erin hoped to return to work, but her injury could have long-term consequences. If she could not meet the physical demands of her position, or similar jobs, the experience and skills she accumulated would not transfer elsewhere. In the years following her harassment, Erin reported declining wages, earning 24 percent less in 2003 despite reporting no job change. Her earnings rose slightly in 2005 after she took a maintenance position for a new employer, but her $12.50 hourly wage was still 20 percent lower than the pay she received before her harassment.

CONCLUSION

In her pioneering work, MacKinnon (1979, 216) argued that sexual harassment “undercuts women’s autonomy outside the home” and reinforces economic dependence on men. This article empirically documents the early career effects of sexual harassment on attainment. Harassment at age 29–30 increases financial stress in the early thirties. Roughly 35 percent of this effect can be attributed to targets’ job change, a common response to severe sexual harassment. As our qualitative data suggest, some women quit work to avoid harassers. Others quit because of dissatisfaction or frustration with their employer’s response. In both cases, harassment targets often reported that leaving their positions felt like the only way to escape the toxic workplace climate.

These findings have important theoretical implications for understanding the role of toxic workplace cultures in stifling women’s career advancement. When gender appears “as a cloudburst, or as an isolated cold front” that travels through the workspace, “women workers tend not to see gender inequality as due to an oppressively chilly climate” (Britton 2017, 23). While women are often able to ignore or minimize gender inequality in such workplaces, largely explaining how it is reproduced, this was not the case for the harassing work environments described by many of our interviewees. In contrast, women in our study were not able to thrive as employees but were instead viewed as outsiders or sex objects in a workplace climate that, as Hannah put it, “wouldn’t be worth me trying to spend all my energy to change.” Employer-led efforts to improve organizational culture, which extends beyond sexual harassment, would likely help retain these employees and reduce turnover costs.

This study also advances theoretical and empirical knowledge on gender and work by showing the short-term, tangible costs to women of sexual harassment and toxic work environments. When men experience disruptions to their school or work trajectory, they remain likely to obtain relatively high paying jobs (Dwyer et al. 2012). We found that the same is not true for women. Further, a voluminous literature documents the long-term effects of job disruption on financial stress and earnings (Brand 2015; Couch and Placzek 2010), but it has not yet addressed sexual harassment. We here conceptualize job transition following harassment as a less-than-voluntary job loss, with resulting short- and long-term effects on employment trajectories. As Brand (2015, 371) explains, “job displacement is an involuntary and often unforeseen disruptive life event that induces abrupt changes in workers’ trajectories.”

The mixed methods nature of this study was vital to understanding this relationship, resulting in “complementary strengths and nonoverlapping weaknesses” (Johnson and Onwuegbuzie 2004, 18). In particular, the quantitative analyses revealed a basic statistical relationship between harassment and financial stress that operates through job change. Our qualitative analyses provided much more detailed and proximal insights into how harassment redirected women’s lives and careers. Our interview data point to several specific ways harassment derails women’s careers beyond this initial job change. Pam’s harassment left her distrusting and reclusive while Hannah, Lisa, and Angela were pushed toward less lucrative careers where they believed sexual harassment and sexist practices would be less likely to occur. These and other women find themselves in the untenable position of having to choose between participating in misogynistic cultures at work, which does not serve them as women, or resisting these cultures, leaving little chance for growth in their companies. In this mixed methods study, the key finding is thus corroborated across the two approaches, providing greater confidence in conclusions about how and why harassment disrupts careers.

Sexual harassment, which is largely overlooked in attainment research, played a prominent role in shaping early career trajectories. Our quantitative and qualitative results indicate that harassment experienced in women’s twenties and early thirties knocks many off-course during this formative career stage. Even more, though most harassment research focuses on direct targets, our study shows that challenging toxic work environments has consequences even for those who are not targeted directly. Lisa, Hannah, and other women in similar environments were ostracized by co-workers for challenging misogyny in the workplace even though they were not direct targets of harassment themselves. Further, most quantitative studies of sexual harassment have focused disproportionately on white-collar jobs. Extending previous research, we find that women in pink- and blue-collar occupations are affected by sexual harassment in the same way as women in white-collar careers. Future research could examine questions at other life stages, such as whether sexual harassment may operate as a push factor for women on the verge of retirement. Such analyses could push gender theorizing on the intersections of gender and age.

Our findings may also help to assess damages in sexual harassment claims, as the long-term economic costs may be more substantial than previously assumed. Injury is difficult to monetize (Sunstein and Shih 2004), and high turnover rates in a target’s profession may lower awards meant to compensate for future lost wages. Adjusting monetary awards based on the average length of employment among workers in similar positions assumes that larger patterns of employee turnover and sexual harassment vary independently. Our findings, however, expose endogeneity issues with this logic, as harassment and gender discrimination are reflective of the culture of a workplace or industry. Although workers must be targeted directly to have legal standing in a court of law, our findings support Resnik’s (2004, 257) conclusion that cultures of harassment inflict “collective and diffuse harms” by depriving workers of a diverse and harassment-free workplace.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jeylan Mortimer for providing the data and support for this research, Lesley Schneider for research assistance, and Sharon Bird and the editors and anonymous reviewers at Gender & Society for their helpful comments on this paper. The Youth Development Study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD44138) and the National Institute of Mental Health (MH42843). The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the author and does not represent the official views of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Respondents were also asked whether they had been physically assaulted by a co-worker, boss, or supervisor, which may indicate sexual assaults that are closely related to harassment (Gibson et al. 2016). We exclude this item due to concerns that the ambiguous wording may lead respondents to include things like pushing, punching, and other forms of physical violence that are unrelated to sexual harassment. When we include the 3 women who report physical assault in our harassment measure, our main findings are identical.

Our sample is 8 percent black, 6 percent Asian, 3 percent mixed race, and 4 percent American Indian, Pacific Islander, or some other race. Over half of Asian women (n=13) identify as Hmong.

This measure combines five negative life events: (1) serious personal injury/illness; (2) breakup of serious romantic relationship; (3) jail; (4) assault, battery, robbery, or rape; and/or, (5) death of spouse/partner. Between 16 and 25 percent of women experienced a negative life event each year.

These patterns are echoed in the larger sample as well. Prior to their 2003 sexual harassment, the biweekly earnings of harassment targets had been $134 higher than the earnings of other working women in the sample. By 2011, however, the mean earnings among sexual harassment targets were $14 lower than their counterparts who had not experienced harassment in 2003.

Heather McLaughlin is an assistant professor in Sociology at Oklahoma State University. Her research examines how gender norms are constructed and policed within various institutional contexts, including work, sport, and law, with a particular emphasis on adolescence and young adulthood.

Christopher Uggen is Regents Professor and Martindale chair in Sociology and Law at the University of Minnesota. He studies crime, law, and social inequality, firm in the belief that good science can light the way to a more just and peaceful world.

Amy Blackstone is a professor in Sociology and the Margaret Chase Smith Policy Center at the University of Maine. She studies childlessness and the childfree choice, workplace harassment, and civic engagement.

Contributor Information

HEATHER MCLAUGHLIN, Oklahoma State University, USA.

CHRISTOPHER UGGEN, University of Minnesota, USA.

AMY BLACKSTONE, University of Maine, USA.

References

- Acker Joan. Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: A theory of gendered organizations. Gender & Society. 1990;4:139–58. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett Jeffrey Jenson. Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Baron Reuben M, David A Kenny. Moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–82. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackstone Amy, Christopher Uggen, McLaughlin Heather. Legal consciousness and responses to sexual harassment. Law & Society Review. 2009;43:631–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5893.2009.00384.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackstone Amy, Jason Houle and Christopher Uggen. “I didn’t recognize it as a bad experience until I was much older”: Age, experience, and workers’ perceptions of sexual harassment. Sociological Spectrum. 2014;34:314–37. [Google Scholar]

- Brand Jennie E. The far-reaching impact of job loss and unemployment. Annual Review of Sociology. 2015;41:359–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-071913-043237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand Jennie E, Juli Simon Thomas. Job displacement among single mothers: Effects on children’s outcomes in young adulthood. American Journal of Sociology. 2014;119:955–1001. doi: 10.1086/675409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton Dana M. Beyond the chilly climate: The salience of gender in women’s academic careers. Gender & Society. 2017;13:5–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. Women’s earnings, 1979–2012. Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor; 2013. http://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2013/ted_20131104.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Cha Youngjoo, Kim A Weeden. Overwork and the slow convergence in the gender gap in wages. American Sociological Review. 2014;79:457–84. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain Lindsey Joyce, Martha Crowley Daniel Tope, Randy Hodson. Sexual harassment in organizational context. Work and Occupations. 2008;35:262–95. [Google Scholar]

- Chan Darius K-S, Chun Bun Lam, Suk Yee Chow, Shu Fai Cheung. Examining the job-related, psychological, and physical outcomes of workplace sexual harassment: A meta-analytic review. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2008;32:362–76. [Google Scholar]

- Couch Kenneth A, Dana W Placzek. Earnings losses of displaced workers revisited. The American Economic Review. 2010;100:572–89. [Google Scholar]

- De Coster Stacy, Sarah Beth Estes, Mueller Charles W. Routine activities and sexual harassment in the workplace. Work and Occupations. 1999;26:21–49. [Google Scholar]

- Denissen Amy M, Saguy Abigail C. Gendered homophobia and the contradictions of workplace discrimination for women in the building trades. Gender & Society. 2014;28:381–403. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer Rachel E, Randy Hodson, McCloud Laura. Gender, debt, and dropping out of college. Gender & Society. 2012;27:30–55. doi: 10.1177/0891243212464906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ecklund Elaine Howard, Lincoln Anne E, Cassandra Tansey. Gender segregation in elite academic science. Gender & Society. 2012;26:693–717. [Google Scholar]

- Even William E. Career interruptions following childbirth. Journal of Labor Economics. 1987;5:255–77. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald Louise F, Drasgow Fritz, Hulin Charles L, Gefland Michele J, Magley Vicki J. Antecedents and consequences of sexual harassment in organizations: A test of an integrated model. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1997;82:578–89. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.82.4.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald Louise F, Shullman Sandra L, Bailey Nancy, Margaret Richards, Janice Swecker, Gold Yael, Ormerod Mimi, Weitzman Lauren. The incidence and dimensions of sexual harassment in academia and the workplace. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 1988;32:152–75. [Google Scholar]

- Gauchat Gordon, Kelly Maura, Wallace Michael. Occupational gender segregation, globalization, and gender earnings inequality in U.S. metropolitan areas. Gender & Society. 2012;26:718–47. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson Carolyn J, Gray Kristen E, Katon Jodie G, Simpson Tracy L, Lehavot Keren. Sexual assault, sexual harassment, and physical victimization during military service across age cohorts of women veterans. Women’s Health Issues. 2016;26:225–31. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenman Emily, Yu Xie. Double jeopardy? The interaction of gender and race on earnings in the United States. Social Forces. 2008;86:1217–44. doi: 10.1353/sof.0.0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber James E. A typology of personal and environmental sexual harassment: Research and policy implications for the 1990s. Sex Roles. 1992;26:447–64. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber James E. The impact of male work environments and organizational policies on women’s experiences of sexual harassment. Gender & Society. 1998;12:301–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber James E, Lars Bjorn. Blue-collar blues: The sexual harassment of women autoworkers. Work and Occupations. 1982;9:271–98. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber James E, Susan Fineran. Comparing the impact of bullying and sexual harassment victimization on the mental and physical health of adolescents. Sex Roles. 2008;59:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hand Jeanne Z, Laura Sanchez. Badgering or bantering? Gender differences in experiences of, and reactions to, sexual harassment among U.S. high school students. Gender & Society. 2000;14:718–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hijzen Alexander, Upward Richard, Wright Peter W. The income losses of displaced workers. Journal of Human Resources. 2010;45:243–69. [Google Scholar]

- Hodson Randy. Some considerations concerning the functional form of earnings. Social Science Research. 1985;14:374–94. [Google Scholar]

- Houle Jason N, Staff Jeremy, Mortimer Jeylan T, Uggen Christopher, Blackstone Amy. The impact of sexual harassment on depressive symptoms during the early occupational career. Society and Mental Health. 2011;1:89–105. doi: 10.1177/2156869311416827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R Burke, Anthony J Onwuegbuzie. Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher. 2004;33:14–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kalof Linda, Eby Kimberly K, Matheson Jennifer L, Rob J Kroska. The influence of race and gender on student self-reports of sexual harassment by college professors. Gender & Society. 2001;15:282–302. [Google Scholar]

- Kandiyoti Deniz. Bargaining with patriarchy. Gender & Society. 1988;2:274–90. [Google Scholar]

- Kletzer Lori G. Job displacement. The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 1998;12:115–36. [Google Scholar]

- Laband David N, Bernard F Lentz. The effects of sexual harassment on job satisfaction, earnings, and turnover among female lawyers. Industrial and Labor Relations Review. 1998;51:594–607. [Google Scholar]

- Lim Sandy, Lilia M Cortina. Interpersonal mistreatment in the workplace: The interface and impact of general incivility and sexual harassment. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2005;9:483–96. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.90.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez Steven H, Hodson Randy, Roscigno Vincent J. Power, status, and abuse at work: General and sexual harassment compared. The Sociological Quarterly. 2009;50:3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Loy Pamela Hewitt, Stewart Lea P. The extent and effects of the sexual harassment of working women. Sociological Focus. 1984;17:31–43. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon Catharine A. Sexual harassment of working women. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall Anna-Maria. Idle rights: Employees’ rights consciousness and the construction of sexual harassment policies. Law and Society Review. 2005;39:83–124. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald Paula. Workplace sexual harassment 30 years on: A review of the literature. International Journal of Management Reviews. 2012;14:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin Heather, Uggen Christopher, Blackstone Amy. Sexual harassment, workplace authority, and the paradox of power. American Sociological Review. 2012;77:625–47. doi: 10.1177/0003122412451728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkin Rebecca S. The impact of sexual harassment on turnover intentions, absenteeism, and job satisfaction: Findings from Argentina, Brazil, and Chile. Journal of International Women’s Studies. 2008;10:73–91. [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer Jeylan T. Working and growing up in America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Padavic Irene, James D Orcutt. Perceptions of sexual harassment in the Florida legal system: A comparison of dominance and spillover explanations. Gender & Society. 1997;11:682–98. [Google Scholar]

- Prokos Anastasia, Irene Padavic. An examination of competing explanations for the pay gap among scientists and engineers. Gender & Society. 2005;19:523–43. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn Beth A. Sexual harassment and masculinity: The power and meaning of “girl watching”. Gender & Society. 2002;16:386–402. [Google Scholar]

- Ranson Gillian, William Joseph Reeves. Gender, earnings, and proportions of women: Lessons from a high-tech occupation. Gender & Society. 1996;10:168–84. [Google Scholar]

- Reskin Barbara F, Debra Branch McBrier. Why not ascription? Organizations’ employment of male and female managers. American Sociological Review. 2000;65:210–33. [Google Scholar]

- Resnik Judith. The rights of remedies: Collective accountings for and insuring against the harms of sexual harassment. In: MacKinnon Catharine A, Siegel Reva B., editors. Directions in sexual harassment law. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Roscigno Vincent J. Power, revisited. Social Forces. 2011;90:349–74. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg Janet, Perlstadt Harry, Phillips William RF. Now that we are here: Discrimination, disparagement, and harassment at work and the experiences of women lawyers. Gender & Society. 1993;7:415–33. [Google Scholar]

- Settersten Richard A, Jr, Barbara Ray. What’s going on with young people today? The long and twisting path to adulthood. The Future of Children. 2010;20:19–41. doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunstein Cass R, Shih Judy M. Damages in sexual harassment cases. In: MacKinnon Catharine A, Siegel Reva B., editors. Directions in sexual harassment law. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tester Griff. An intersectional analysis of sexual harassment in housing. Gender & Society. 2008;22:349–66. [Google Scholar]

- Texeira Mary Thierry. “Who protects and serves me?”: A case study of sexual harassment of African American women in one U.S. law enforcement agency. Gender & Society. 2002;16:524–45. [Google Scholar]

- Theunissen Gert, Verbruggen Marijke, Forrier Anneleen, Luc Sels. Career sidestep, wage setback? The impact of different types of employment interruptions on wages. Gender, Work and Organization. 2011;18:110–31. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Labor. Table 18. Employed persons by detailed industry, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity. US Department of Labor, Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2003 Retrieved November 18, 2015 ( http://www.bls.gov/cps/aa2003/cpsaat18.pdf)

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Charges alleging sexual harassment FY 2010 – FY 2015. 2015 Retrieved March 18, 2016 ( http://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/enforcement/sexual_harassment_new.cfm)

- U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board. Sexual harassment in the federal government: An update. Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Uggen Christopher, Blackstone Amy. Sexual harassment as a gendered expression of power. American Sociological Review. 2004;69:64–92. doi: 10.1177/0003122412451728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullah Philip. The association between income, financial strain and psychological well-being among unemployed youths. Journal of Occupational Psychology. 2011;63:317–30. [Google Scholar]

- Welsh Sandy. Gender and sexual harassment. Annual Review of Sociology. 1999;25:169–90. [Google Scholar]

- Welsh Sandy, Jacquie Carr Barbara MacQuarrie, Audrey Huntley. “I’m not thinking of it as sexual harassment”: Understanding harassment across race and citizenship. Gender & Society. 2006;20:87–107. [Google Scholar]

- Western Bruce. Punishment and inequality in America. New York: Russell Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Willness Chelsea R, Steel Piers, Kibeom Lee. A meta-analysis of the antecedents and consequences of workplace sexual harassment. Personnel Psychology. 2007;60:127–62. [Google Scholar]

- Xu Wu, Ann Leffler. Gender and race effects on occupational prestige, segregation, and earnings. Gender & Society. 1992;6:376–92. [Google Scholar]