Abstract

Background

Multimorbidity in heart failure (HF), defined as HF of any aetiology and multiple concurrent conditions that require active management, represents an emerging problem within the ageing HF patient population worldwide.

Methods

To inform this position paper, we performed: 1) an initial review of the literature identifying the ten most common conditions, other than hypertension and ischaemic heart disease, complicating the management of HF (anaemia, arrhythmias, cognitive dysfunction, depression, diabetes, musculoskeletal disorders, renal dysfunction, respiratory disease, sleep disorders and thyroid disease) and then 2) a review of the published literature describing the association between HF with each of the ten conditions. From these data we describe a clinical framework, comprising five key steps, to potentially improve historically poor health outcomes in this patient population.

Results

We identified five key steps (ARISE-HF) that could potentially improve clinical outcomes if applied in a systematic manner: 1) Acknowledge multimorbidity as a clinical syndrome that is associated with poor health outcomes, 2) Routinely profile (using a standardised protocol — adapted to the local health care system) all patients hospitalised with HF to determine the extent of concurrent multimorbidity, 3) Identify individualised priorities and person-centred goals based on the extent and nature of multimorbidity, 4) Support individualised, home-based, multidisciplinary, case management to supplement standard HF management, and 5) Evaluate health outcomes well beyond acute hospitalisation and encompass all-cause events and a person-centred perspective in affected individuals.

Conclusions

We propose ARISE-HF as a framework for improving typically poor health outcomes in those affected by multimorbidity in HF.

Keywords: Heart failure, Multimorbidity, Person-centred perspective, Multidisciplinary management

1. Introduction

Those with multimorbidity are an emerging patient population that is challenging health care systems worldwide. For example, almost half of all US adults live with one chronic illness [1] and multimorbidity is increasing as the population ages [2]. Accordingly, recent estimates suggest that two-thirds of US Medicare beneficiaries (close to 21 million patients) have two or more chronic conditions and more than one-third have four or more [3,4]. Similarly, in Australia and Europe, a quarter of the population has multimorbidity, with prevalence and complexity increasing with age: 83%, 58% and 33% of patients aged 75 years or older have at least two, three or four concurrent conditions, respectively, requiring active management [5,6]. Unsurprisingly, multimorbidity is not a benign phenomenon. The risk of hospitalisation, re-hospitalisation, and death rise as the number of chronic conditions increases [7].

Multimorbidity is common in patients with heart failure (HF), increasing their risk for poor health outcomes. Lone HF is rare and is exceedingly rare in the predominant HF patient population aged 75 years and older [8]. In the US, approximately 40% of Medicare beneficiaries with HF have >5 non-cardiac conditions and this group accounts for >80% of the total inpatient HF-related hospital days in the US [9]. Annual total costs for HF are expected to more than double between 2012 and 2030 ($31 billion to $70 billion USD) [10] making HF the foremost contributor to Medicare expenditures [11]. The majority (61%) of hospital readmissions are attributable to multimorbidity [12], and occur within 15-days of discharge [13]. About half of all hospitalisations in HF patients are thought to be preventable [9]. This is particularly problematic in those with HF and preserved ejection fraction, for whom multimorbidity is the major driver of hospitalisations. To date, authors of expert guidelines have struggled to address the issue of multimorbidity in HF and articulate clear pathways to optimise health outcomes. Not surprisingly, however, there has been increasing interest in providing clinicians and health care teams with more guidance to improve the management of HF in the context of multimorbidity [14].

2. Aims

We recognise the complex clinical challenges inherent to managing HF in the setting of multimorbidity and the limitations of practice guidelines in providing a comprehensive overview of the applicability of treatment options. Thus, the specific aims of this position paper (from an international, multidisciplinary panel of health professionals with an ongoing interest and expertise in HF management) are two-fold:

To provide a comprehensive overview of the current literature focussing on the most common conditions requiring concurrent treatment and management in patients with HF.

To articulate a practical framework for establishing a systematic response to this increasingly common clinical phenomenon that has the potential to improve health outcomes.

We explicitly recognise that the practical steps outlined in this document are yet to be proven in terms of improved health outcomes (indeed they form the basis for a proposed, international, multicentre trial). However, we propose that these steps be used (in part or in their entirety) to inform and complement contemporary guidelines to improve health outcomes in those affected by HF and multimorbidity, regardless of the health care system in which they are managed.

3. Literature review

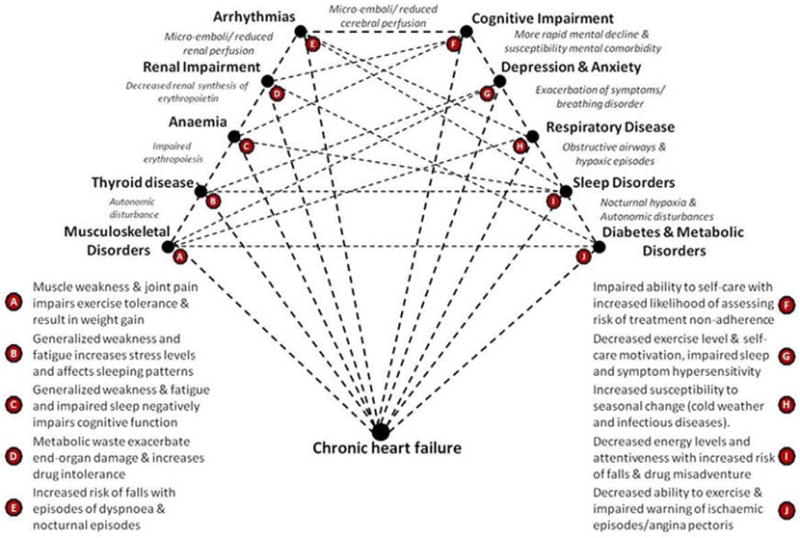

We began by surveying the literature, noting a contemporary study of multimorbidity in the HF patient population [15,16]; we identified the ten most prevalent concurrent conditions in HF (other than hypertension and ischaemic heart disease) requiring concurrent management. The ten most prevalent conditions (other coronary disease and hypertension) identified in the literature were anaemia, sleep disordered breathing, respiratory disease, Type 2 diabetes, depression, renal impairment, cognitive impairment, musculoskeletal disorders, arrhythmias, and thyroid disease. This list was then validated in two large patient cohorts (>1000 patients) in Australia and the USA via purposeful profiling (comprising detailed psychosocial and clinical phenotyping) of typically older patients with HF at the time of hospital discharge. Whilst we acknowledge this may not represent the definitive “top ten” list of concurrent conditions in HF (indeed we considered a number of other potential conditions of interest) in all settings, we largely focus on our validated list. These conditions are often closely linked, occur concomitantly, and represent natural targets for better management from a multimorbidity perspective due to the typical clinical “conundrum” they represent — see Fig. 1: A conundrum of multimorbidity in HF (reproduced with permission) [15]. As depicted in Fig. 1, the patterns of interaction in multimorbidity present an opportunity to prospectively manage predictable gaps in patient care, such as polypharmacy, care coordination, and communication among multidisciplinary providers.

Fig. 1.

A conundrum of multimorbidity in HF (reproduced with permission).

Focussing on these ten pre-specified conditions, we then searched the literature (using the specific search terms outlined in Table 1) to identify publications focused on the management of these conditions in the setting of HF. Specifically, the search was performed using Medline and was limited to reports published during the period 2005 to 2015, in order to capture the most up-to-date literature. Ten individual searches were conducted in which the specific co-morbidity of interest, along with HF, and their combined management or treatment was entered into Medline. This yielded a total of 3573 citations, which were then reviewed for relevancy — see Table 1. The full text articles were reviewed and a tabulated summary of extracted information from 194 papers is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Table 1.

Search terms used to identify published reports focussing on HF and the ten pre-specified concurrent conditions with total citations found.

| Comorbidity | Search terms | Citations |

|---|---|---|

| Anaemia | Anaemia OR anemia AND heart failure AND Management OR treatment |

303 |

| Sleep disordered breathing | Sleep disordered breathing OR obstructive sleep apnoea OR central sleep apnoea AND heart failure AND management OR treatment |

179 |

| Respiratory disease | Respiratory disease OR dyspnoea OR chronic obstructive pulmonary disease AND heart failure AND management OR treatment |

817 |

| Diabetes mellitus | Diabetes mellitus AND heart failure AND management OR treatment |

486 |

| Depression | Depression AND heart failure AND management OR treatment |

387 |

| Renal impairment | Renal impairment OR renal dysfunction AND heart failure AND management OR treatment |

322 |

| Cognitive impairment | Cognitive impairment AND heart failur AND management OR treatment |

74 |

| Musculoskeletal disorders | Musculoskeletal disorders OR osteoporosis OR osteopenia OR osteoarthritis OR rheumatoid arthritis AND heart failure AND management OR treatment |

105 |

| Arrhythmias | Arrhythmias OR atrial fibrillation AND heart failure AND management OR treatment |

814 |

| Thyroid disease | Thyroid disease OR hyperthyroidism OR hypothyroidism AND heart failure AND management OR treatment |

86 |

The literature reviewed using this search strategy and subsequent data extraction (noting the often fragmented approach to examining multimorbid conditions in HF) was contextualised according to the authors’ own experiences in managing large numbers of older patients (i.e. those aged 75 years or more) with HF and multimorbidity. A pragmatic clinical framework, ARISE-HF, (comprising a series of five key steps — see text box below) to frame clinical practice, research, and future health policy was initially drafted by SS and BR and subsequently circulated for review, revision and approval by the group.

| ARISE-HF |

| A = Acknowledge multimorbidity as a clinical syndrome that is associated with poor health outcomes |

| R = Routinely profile (using a standardised protocol - adapted to the local health care system) all patients hospitalised with HF to determine the extent of concurrent multimorbidity |

| I = Identify individualised priorities and person-centred goals based on the extent and nature of multimorbidity |

| S = Support individualised, home-based, multidisciplinary, case management to supplement standard HF management |

| E =Evaluate health outcomes well beyond acute hospitalisation and encompass all-cause events |

The section below expands upon the ARISE-HF framework and how it might be applied on a systematic basis.

4. A step-wise approach to improve health outcomes (ARISE-HF)

4.1. Step 1: Acknowledge multimorbidity as a clinical syndrome associated with poor health outcomes

As previously noted by Tinneti and colleagues [17], multimorbidity in HF has emerged as a clinical syndrome associated with poor health outcomes. Based on our review of the literature (see below), it is reasonable to classify HF with concomitant multimorbidity as a distinct clinical syndrome in order to provoke a more systematic response from the health care system. For example, it is of particular concern that HF patients with a high burden of multimorbidity living in low-income areas are at increased risk for all-cause re-hospitalisation, suggesting that illness burden may influence the association between income and outcomes in these patients [18]. In contrast to an increasing recognition that specific clusters of conditions are associated with extended length of hospital stay, elevated cost, and increased risk of mortality [19], the current literature is largely fragmented, focussing on common clinical dyads (e.g. HF and diabetes) and framing clinical management in isolation from other complicating factors (e.g. renal dysfunction). Supplementary Table 1 summarises key clinical issues for each condition of interest.

4.2. Step 2: Routinely profile (using a standardised protocol) patients with HF to determine the extent of concurrent multimorbidity

A logical extension to recognising multimorbidity in HF as a clinical syndrome requiring a coordinated clinical response is to identify which patients (particularly those at high risk of related poor health outcomes) are affected by what condition. As such, we recommend all older patients admitted to hospital with HF should be systematically profiled for multimorbidity in order to optimise care. At minimum, this would include the ten common conditions identified that complicate HF management (other than routinely diagnosed and managed coronary artery disease and hypertension) with consideration of other potential conditions according to the patients clinical profile. In the presence of multiple admissions/clinical instability, it would be reasonable to review the extent and progression of multimorbidity on a regular basis. Findings should be noted in the clinical records and included as part of any communication with the patient’s wider health care team. Advanced electronic health records (EHR) and informatics would facilitate both the identification and tracking of such individuals. However, EHR capacity is highly variable across different health systems. It is also important to note that any protocol for managing patient’s with HF and multimorbidity will likely rely on a component of “routine” profiling (e.g. review of prior records and standard review of electronic systems) as well as an active component of profiling (e.g., to determine cognitive function). Although profiling focusses on hospitalised individuals, there is a clear need to consider when it is best and most reliable to perform profiling; ideally when the individual is clinically stable and, in some cases, post hospital discharge. The latter in particular requires clear lines of communication with the primary health care team. Table 2 summarises the definitions and methods that might be routinely applied to identify ten common comorbid conditions in HF (i.e. those conditions of particular interest to this position paper).

Table 2.

Suggested framework for documenting and quantifying multimorbidity in HF.

| Co-morbidity | Data source and determination | Definition/deficit threshold |

|---|---|---|

| Anaemia | Full blood examination during hospital admission | Serum Hb level b 130 (women)/b120 g/L (men) [126,127] |

| Atrial and ventricular arrhythmias | Review of medical notes plus review of prescribed pharmacotherapy at discharge If high clinical suspicion of undiagnosed arrhythmia - 12-lead ECG, inpatient telemetry or extended ECG Holter monitoring |

Confirmation of AF, other atrial arrhythmias, 2nd or 3rd degree heart block, VT/VF with prescription of anti-arrhythmic therapy or pacemaker/defibrillator device [128] |

| Cognitive impairment/dementia | Assessed via Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) tool prior to hospital discharge by trained personnel | Documented diagnosis of dementia or MoCA score b 26 out of a maximal possible score of 30 [129] |

| Depression/anxiety | Assessed via PQ-2 [130] questionnaire prior to hospital discharge by trained personnel plus review of medical notes and prescribed pharmacotherapy at discharge. If positive, apply more comprehensive tool (e.g. HADS) [131] | Positive response to depressive symptoms and/or confirmed diagnosis (with active anti-depressant/anxiolytic) of depression or anxiety |

| Diabetes and metabolic disorders | Review of medical notes and prescribed pharmacotherapy at discharge Calculation of body mass index (BMI) If high clinical suspicion of underlying diabetes HbA1c and/or glucose tolerance tests |

Documented diagnosis of Type 2 Diabetes or obesity BMI N 30 kg/m2 plus dyslipidaemia and/or hypertension (metabolic syndrome) |

| Musculoskeletal disorders | Review of medical notes and prescribed pharmacotherapy at discharge Frailty test with hand-grip manometer, gait speed, six-minute walk test, and Short Physical Performance Battery including static balance, gait speed and getting in and out of a chair [101] |

Documented diagnosis of arthritis, osteoporosis, gout or any other musculoskeletal condition requiring active therapy (e.g. anti-inflammatory or analgesia) |

| Renal impairment | Electrolytes and renal function obtained during hospital admission Calculation of body mass index | Estimated glomerular filtration rate b 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 [132] |

| Respiratory disease | Review of medical notes and prescribed pharmacotherapy at discharge If high clinical suspicion of underlying respiratory disease - formal lung function tests |

Lung function confirmation of COPD, asthma and/or other chronic pulmonary condition requiring active treatment [133] |

| Thyroid disease | Review of medical notes and prescribed pharmacotherapy at discharge If high clinical suspicion of, or historical lack of screening, perform thyroid function tests (including thyroid stimulating hormone levels) at hospital admission |

Documented hyper/ hypothyroidism based on according to national standards with associated anti-thyroid or thyroxine replacement therapy [134] |

| Sleep disorders | Review of medical notes and prescribed sleep support device. If high clinical suspicion of sleep disordered breathing perform formal sleep studies Use of a screening questionnaire in hospital to identify those with sleep-disordered breathing (135) |

Documented diagnosis of obstructive or central sleep disordered breathing |

4.3. Step 3: Identify individualised priorities and person-centred goals based on the extent and nature of multimorbidity

As shown in Supplementary Table 1, there are potentially many competing priorities arising from multimorbidity in HF that are not easily addressed in a generic manner — hence the historical difficulty for guideline committees to provide specific recommendations in the setting of marginal benefit-risk ratios. For example, there has been a reluctance to prescribe high doses of neurohormonal/vasodilator therapy in the setting of frailty and high risk of falls and/or evidence of progressive renal dysfunction despite the potential benefits [20,21]. On this basis, we suggest a structured approach that considers the nature and severity of multimorbidity, defines an individualised list of clinical priorities and identifies the need for specialist consultation when appropriate. Critically, as part of a patient-centred approach, patient preferences and goals regarding their own health [22], as well as conflicting and contraindicated treatment options should play a prominent role in the decision points of the algorithm. This requires a truly multidisciplinary, team-based approach to management [23] that provides the patient and their caregivers with the knowledge to foster better care and to provide advice on their options pertaining to their treatment and management. Whilst we have suggested a clear focus on the hospitalised patient (with the opportunity to complete most if not all components of screening for multimorbidity), it is clear that subsequent management will be applied within the community/out-patient setting. A suitably qualified health professional (such as an experienced nurse with relevant qualifications) has the capacity to generate realistic and achievable care/action plans when — a) consulting and assessing patients in their home and then b) consulting with the wider health care team to determine what can be done to meet the patient’s needs [24–26].

4.4. Step 4: Support individualised, home-based, multidisciplinary, case management to supplement standard HF management

As recently articulated in the AHA/ACC/HHS Strategies to Enhance Application of Clinical Practice Guidelines in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease and Comorbid Conditions [27], there is a compelling imperative to adjust management strategies in the setting of multimorbidity, and standard HF management is no exception. Beyond recognising and characterising multimorbidity (see recommendations 1–3), strategic plans that are robust (i.e., can be applied in different health care systems with variable personnel, capacity and resources), flexible, feasible, cost-effective and focused on addressing each problem in the broader context need to be formulated.

4.4.1. Management options

Disease management has demonstrated benefit for improving clinical outcomes. In the last two decades, a variety of robust HF disease management approaches have been developed and tested, aimed at improving HF outcomes and reducing hospitalisations [26,28–31]. Numerous meta-analyses have documented the effectiveness of disease management programmes for HF [32–40]. However, implementation of these programmes in clinical practice is highly variable. This is reflected in a recent study confirming wide variation in the care provided to HF patients after discharge from the hospital [41]. A pooled analysis of ten HF disease management RCTs highlighted that the essential components of these programmes in reducing the number and length of hospital admissions were multidisciplinary, team-based care that included in-person communication between case managers, physicians and patients [42].

It is notable that much of the evidence-base supporting HF disease management programmes, for both historical and practical reasons, has been primarily focused on relatively less complex cases, and thus is less applicable to the population with HF and multimorbidity. Yet, epidemiological data show that patients hospitalised with HF are becoming increasingly older (with associated multimorbidity rising at the same time) [43–45]. Accordingly, more contemporary clinical trials of HF management are dealing with older and more complex cases [46, 47]; particularly when compared to earlier trials focussing on managing HF patients on an outpatient/ambulatory basis (the predominant model of care in many parts of the world [48]. Unfortunately, therefore, the relevance of previously effective management programmes in HF is likely to be eroded by an increasing proportion of patients with HF and multimorbidity with more challenging clinical priorities. Indeed, this may explain the neutral results of trials of more HF-centric interventions such as the COACH Study [49] and those applying remote monitoring techniques [50]. In comparison, positive results of home-based management when compared to clinic-based treatment in the WHICH? Trial [25] suggests a promising approach for those with HF and multimorbidity. To our knowledge, however, there are no definitive approaches to improve typically poor health outcomes that extend beyond standard HF management models of care.

The inherent complexity of managing multiple comorbid conditions is exacerbated by issues such as frailty, social isolation, impaired cognition and limited income that frequently negatively impact on sufferers of HF, who are typically elderly [51–53]. Although practical and disease-related issues are often closely interrelated [16,54–56], complexity is often overlooked, adversely affecting quality of life, hospital admission risk and survival [57–59]. Recent research reveals that it is these very complex, multimorbid or high-risk patients who stand to benefit most from home-based patient-centred management programmes [60]. From a health-cost perspective, the home-based approach to patient-centred management has been shown to be more both clinically beneficial (reduced hospital stay and prolonged survival) and cost-effective when compared to an equivalent specialist HF clinic in the head-to-head WHICH? Trial. Notably this trial specifically targeted older patients with HF and multimorbidity [61]. Taken together, these findings support the need for a paradigm shift — away from disease management, which by definition targets a specific primary disease (e.g. HF), to a more holistic approach, which considers each condition in the broader context of competing morbidities and seeks to design care in a way that optimises patient-centred outcomes (i.e., patient-centred care).

4.4.2. Coordinating care in the setting of multimorbidity in HF

Interventions addressing multimorbidity and clinical complexity in this population have the potential to reduce hospitalisations and prolong survival beyond that achieved by traditional disease management and transitional care programmes. The latter targets poor communication and poorly coordinated transitions at hospital discharge that contribute to negative health outcomes and increases the financial burden on the healthcare system (i.e., adverse events and increased hospitalisations) [62]. Transitional care is effective in older adults with HF who require complex care [63]. However, transitional care typically continues for at most 3-months after hospital discharge, which risks readmission if self-care is not mastered and/or comorbid conditions are not stabilised during that period. Although interventions for specific disease combinations have been tested (e.g., HF and diabetes) [64–67], clinical guidelines integrating the care of multiple conditions are rare. [68]. Other approaches such as interdisciplinary primary care [69] and interdisciplinary teams for nursing home residents [70] are in the early phases of testing. Two promising interventions for multimorbidity are patient-centred medical homes [71] and Guided Care [72–74]; both of which have the potential to overcome the challenge of home-bound individuals accessing community resources [75]. Likewise, the effectiveness of physician house call programmes [76], as well home-support with a more diverse team such as the CAPABLE team (comprising a nurse, an occupational therapist and a handyman) are being evaluated [77,78].

4.4.3. An emphasis on self-care

Self-care important in any health condition, is particularly crucial for patients with complex illnesses and comorbidity. The seminal work in defining self-care in adults with chronic illness has been undertaken by Riegel and colleagues [79–81], who have conducted numerous studies aimed at understanding [82–86] and strengthening the ability of patients to perform self-care activities including adherence to medications and diet, as well as the detection and management of symptoms [87–89]. Encouragingly, a recent pilot study demonstrated that in a predominantly minority HF sample with significant multimorbidity, a tailored home-based intervention using motivational interviewing and skill-based education [87,89] achieved a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in self-care that exceeded that of standard care [90,91]. Furthermore, hospitalisations unrelated to HF were less frequent in the group receiving the intervention [92]. Overall, there is good evidence to suggest that enhanced self-care can decrease symptom severity, improve health related quality of life (HRQoL), delay acute decompensation, and prevent hospitalisation in HF patients [93–95].

4.4.4. A carer-centred approach

Given that self-care may be particularly challenging for those HF patients with comorbid conditions such cognitive impairment [96], it is vital that the role of the family and other caregivers be recognised and supported. A recent systematic narrative review revealed that despite the pivotal role played by caregivers in the care of HF patients, their needs have not been clearly understood [97]. Three major areas of need identified were, 1) psychosocial support to maintain a sense of normalcy, 2) support with daily living, and 3) support navigating the healthcare system. Although health professionals agree that patient and caregiver uncertainty and unmet needs are major problems, they feel lacking in knowledge, opportunities, or have adequate support to improve the situation [98]. In order to improve outcomes for both caregivers and HF patients, it seems clear that an individualised, person and family-centred approach is required and must address issues arising both from HF and from multimorbidity. In addition, it is vital for future research to focus on how to optimally support and assist caregivers.

4.4.5. Applying case management in multimorbidity

Case management is a collaborative process used to assess, plan, implement, coordinate, monitor, and evaluate the services required to meet a patient’s health and human service needs [99]. The case management process is characterised by communication, resource management, and advocacy with a focus on promoting quality and cost-effective care. A key component of case management, as with other successful disease management strategies, is a post-discharge home visit to chronically ill, older adults who have complex social and environmental issues (e.g., social isolation, financial stress) that are rarely recognised and addressed in routine clinical care [57–59]. In addition to shifting the locus of control to the patient and assessing any residual signs of clinical instability, a post-discharge home visit permits a physical walk-through of the home with the patient, noting any environmental issues that would compromise safety, most notably entry sites and steps, bathroom areas and flooring (e.g. loose rugs that may require attention for those with physical frailty). At the same time, this visit allows the case manager to assess and support self-care abilities in a naturalistic environment; permitting them to tailor interventions to address the individual characteristics of the recipient [100], and focussing on skill rather than simply knowledge [87,89]. Additionally, including physiotherapy-based treatments may be beneficial as it has been recently shown that physiotherapy assists in falls prevention and reducing functional deficits in those with cardiovascular disease [101]. Specifically, aerobic or resistance training can assist to improve physical performance and HRQoL, and may increase the probability of older adults remaining independent [101,102], with home-based exercise programmes found to be as effective as supervised exercise programmes [103,104].

The fundamental role of the case manager (typically an experienced nurse with relevant post-graduate qualifications and excellent communication skills), is coordination and navigation, marshalling both personnel and resources needed to carry out required patient care activities [105]; this includes involving families and caregivers. The case manager is responsible for exchanging information among the various providers to help ensure that the patient’s needs and preferences for health services and information are met [106]. Given the complexity and potential for competing priorities in this clinical setting, it is critical that the need for all therapies, especially those with risk for harm, be critically assessed. For example, polypharmacy is ubiquitous in this patient population and a process of “de-prescribing” should be considered. This may include weaning central nervous system-active medicines (benzodiazepines, opioids), corticosteroids, and even cardiovascular drugs (e.g. statins, beta-blockers) over a timeframe of weeks to months [107,108].

4.5. Step 5: Evaluate health outcomes well beyond acute hospitalisation and encompass all-cause events and a person-centred perspective in affected individuals

Despite an understandable focus on immediate and costly rebounds to hospital in the short-term (i.e. within 30-days) [109–112], there is a strong rationale for adopting a longer and more holistic perspective to reflect the entire patient journey. The classical description of the natural history of HF reinforces this point; periods of clinical instability are typically interspersed with periods of relative stability [113]. Clinical studies of disease management programmes often adopt singular endpoints (e.g. risk of re-hospitalisation) over a short period of time and/or confine analyses to those events relating to the syndrome (i.e., HF specific). However, such an approach is limited from both a patient and health service perspective because there is clear potential for longer survival free from all-cause hospitalisation and with improved HRQoL. In simple terms, restricting follow-up to a short-time period (e.g. 30-days to 3-months) belies the complex interplay between short-term and long-term stability with respect to the potential benefit of more intensive management. For example, a “therapeutic” early readmission may result in fewer hospital days and better quality of life over the ensuing 12-month period.

These considerations do not undermine the importance of monitoring short-term outcomes; particularly when one considers that 20–25% of HF patients are readmitted within 30-days of hospital discharge [13]. Due to the costs of hospitalisation [10], scrutiny of readmissions has intensified in many countries. In this regard, multimorbidity has been identified as playing a critical role in driving both early and late readmissions in HF [18]. Indeed, two-thirds of patients readmitted within 30-days are hospitalised for a condition other than HF [13]. On this basis, there is a strong rationale to examine the overall pattern of morbidity and mortality (i.e. on an all-cause basis) over the longer-term; particularly when considering the pattern of multimorbidity present (derived from systematic profiling). Concurrently, the desire to involve patients in setting their own goals provides a strong argument for evaluating the relative success of management from a person-centred perspective, such as patient-reported HRQoL and satisfaction with health service delivery.

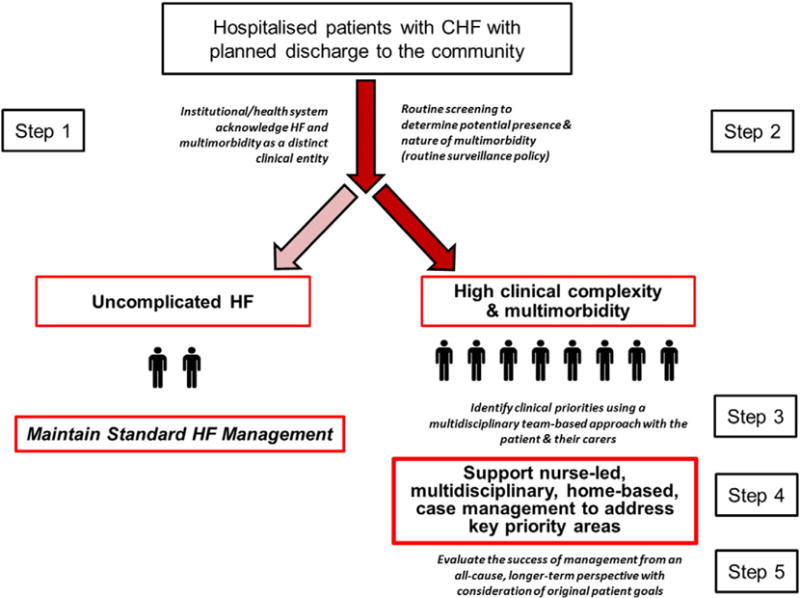

Fig. 2: Pragmatic interpretation of how the 5 key recommendations for improving health outcomes in HF and multimorbidity might be applied on a differential basis, illustrates how the five steps outlined above might be applied to improve health outcomes in this increasingly common patient cohort; as suggested by this figure, patients with HF and multimorbidity now represent the majority of those hospitalised with HF. However, future research is required to determine how to apply these steps in a cost-efficient manner (including the use of information technology to facilitate profiling and communication strategies) and, to determine if the steps do indeed achieve better health outcomes in a range of health care settings.

Fig. 2.

Pragmatic interpretation of 5 key recommendations.

5. Discussion

There is overwhelming evidence that multimorbidity in HF is a growing problem within an ageing population of HF patients. For example, according to U.S. Census Bureau projections, between 2000 and 2030, those 65 years and over are expected to increase from 34.8 million to over 70.3 million. In addition, those aged ≥85 years are the fastest growing age group, and the number of 85+ year olds in the US is expected to increase fivefold by 2050 [114]. Since approximately 75% of older Americans have two or more chronic conditions, the number of patients with HF and multimorbidity will inevitably continue to rise [115]. Not only is multimorbidity becoming more common, it is associated with poor health outcomes that potentially defy disease management strategies developed for younger and less complex cases of HF. As such, without pro-active management strategies to stabilise the clinical status of affected individuals in the longer-term, progression to geriatric syndromes such as falls, worsening renal function, and repetitive hospitalisations that ultimately lead to disability, frailty, loss of independence, and death will continue to occur with accelerating frequency [114,115].

The potential for an increasing pool of patients with HF and multimorbidity to generate an unsustainable wave of patients with complex health care needs that are currently poorly served by existing health systems cannot be over-stated. As previously suggested by our group [15], reducing hospitalisations for any particular problem (e.g. acute decompensated HF) has the potential for avoiding deleterious consequences of hospitalisation itself, including delirium, iatrogenic illness, infections, deconditioning, sarcopenia, and increased falls risk. Recognising and addressing these risks and potential adverse effects is critical for reducing disability and optimising long-term health outcomes. For example, sarcopenia represents an increasingly important health problem in older adults [116]. For the HF patient, an initial hospital admission with associated bed-rest is likely to exacerbate underlying muscle dysfunction and wasting [117]; increasing the risk of recurrent hospitalisation in the absence of proactive mobilisation and occupational therapy [118,119]. Similarly, catastrophic fall risk increases exponentially in the hospital setting; something that is routinely observed in the clinical management of older patients with HF and multimorbidity. Therefore, more pro-active efforts to minimise age-related physical decline and dysfunction are necessary [120].

In writing this position paper, we explicitly acknowledge the inherent limitations of our review of the literature relating to HF and multimorbidity in respect to a predominant focus on co-morbidity as opposed to multimorbid interactions (the latter reflecting the limitations of the literature in this regard). The prevalence and influence of specific conditions (including the ten conditions of specific interest) will undoubtedly vary within different HF populations. We have made no distinction between HF with reduced or preserved ejection fraction. At the same time, we have not focused on the most common antecedents of HF (hypertension and ischaemic heart disease) as we believe these are routinely addressed in the majority of patients with HF. This paper is not a guideline or a systematic review. However, we have intentionally focussed on providing a framework of clinical actions rather than specific recommendations for clinical management; as emphasised repeatedly, management needs to be individualised while considering the type of information provided in Supplementary Table 1.

As emphasised throughout this position paper, any approach to the complex issues engendered by an increasing number of individuals with HF and multimorbidity requires an overarching, strategic approach. Our clinical framework for action, comprising the five key steps of ARISE-HF, can be best viewed through the prism of a previously published policy framework (and overarching goals) for improving health outcomes and HRQoL in individuals with multimorbidity [121–123]:

Foster health care and public health system changes to improve the health of with HF and multimorbidity. This includes developing evidence-supported models to improve care coordination, defining appropriate health care outcomes and providing incentives to make positive changes to the health care system.

Facilitate self-care, wherever possible, with an equal emphasis on facilitating home and community-based services.

Provide better tools, strategies and information to health professionals directly managing individuals with multimorbidity so they can improve the effectiveness of care delivery and subsequent health out-comes.

Undertake health services research to fill critical gaps in our understanding of multimorbidity in HF with an emphasis on clinical, community, and patient-centred studies that seek to develop cost-effective models of care.

In the future, we anticipate a greater focus on managing multimorbidity in HF in clinical practice guidelines but with a far greater emphasis on principles of individualised management rather than specific instructions. We emphasise, therefore, that this clinical framework, generated from a diverse collection of health professionals with practical expertise in the management of patients with multimorbidity, complements existing HF guidelines [124,125]. Our future challenge is to determine how best to incorporate what we have proposed into clinical practice and to demonstrate that it does indeed, as we expect, improve health outcomes in this growing patient population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

SS and MJC are supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (1041796 and 1032934). WSW is supported by an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under grant number U54-GM104941. The authors have stated that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors report no relationships that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.03.001.

References

- 1.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Chronic Care: Making the Case for Ongoing Care. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ward BW, Schiller JS. Prevalence of multiple chronic conditions among US adults: estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 2010. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E65. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Chronic conditions Among Medicare Beneficiaries. Chart Book; Baltimore, MD: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lochner KA, Cox CS. Prevalence of multiple chronic conditions among Medicare beneficiaries, United States, 2010. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E61. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Britt HC, Harrison CM, Miller GC, Knox SA. Prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity in Australia. Med J Aust. 2008;189(2):72–77. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uijen AA, van de Lisdonk EH. Multimorbidity in primary care: prevalence and trend over the last 20 years. Eur J Gen Pract. 2008;14(Suppl. 1):28–32. doi: 10.1080/13814780802436093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Longman JM, Rolfe M, Passey MD, Heathcote KE, Ewald DP, Dunn T, et al. Frequent hospital admission of older people with chronic disease: a cross-sectional survey with telephone follow-up and data linkage. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:373. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salive ME. Multimorbidity in older adults. Epidemiol Rev. 2013;35:75–83. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxs009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braunstein JB, Anderson GF, Gerstenblith G, Weller W, Niefeld M, Herbert R, et al. Noncardiac comorbidity increases preventable hospitalizations and mortality among Medicare beneficiaries with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(7):1226–1233. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00947-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, Bluemke DA, Butler J, Fonarow GC, et al. Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(3):606–619. doi: 10.1161/HHF.0b013e318291329a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Krumholz HM. Strategies to reduce heart failure readmissions. JAMA. 2014;311(11):1160. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, Bueno H, Ross JS, Horwitz LI, et al. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA. 2013;309(4):355–363. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.216476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chong VH, Singh J, Parry H, Saunders J, Chowdhury F, Mancini DM, et al. Management of non-cardiac comorbidities in chronic heart failure. Cardiovasc Ther. 2015;33(5):300–315. doi: 10.1111/1755-5922.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stewart S, Riegel B, Thompson DR. Addressing the conundrum of multimorbidity in heart failure: do we need a more strategic approach to improve health outcomes? Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2016;15(1):4–7. doi: 10.1177/1474515115604794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Triposkiadis FK, Skoularigis J. Prevalence and importance of comorbidities in patients with heart failure. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2012;9(4):354–362. doi: 10.1007/s11897-012-0110-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tinetti ME, Fried TR, Boyd CM. Designing health care for the most common chronic condition — multimorbidity. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2493–2494. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foraker RE, Rose KM, Suchindran CM, Chang PP, McNeill AM, Rosamond WD. Socioeconomic status, Medicaid coverage, clinical comorbidity, and rehospitalization or death after an incident heart failure hospitalization: atherosclerosis risk in communities cohort (1987 to 2004) Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4(3):308–316. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.959031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee CS, Chien CV, Bidwell JT, Gelow JM, Denfeld QE, Creber R Masterson, et al. Comorbidity profiles and inpatient outcomes during hospitalization for heart failure: an analysis of the U.S. Nationwide inpatient sample. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2014;14:73. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-14-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, Auricchio A, Bohm M, Dickstein K, et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(14):1787–1847. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Jr, Drazner MH, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128(16):1810–1852. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whitty JA, Stewart S, Carrington MJ, Calderone A, Marwick T, Horowitz JD, et al. Patient preferences and willingness-to-pay for a home or clinic based program of chronic heart failure management: findings from the Which? trial. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e58347. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Heart Foundation of Australia. Multidisciplinary Care for People with Chronic Heart Failure. Principles and Recommendations for Best Practice. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stewart S, Ball J, Horowitz JD, Marwick TH, Mahadevan G, Wong C, et al. Standard versus atrial fibrillation-specific management strategy (SAFETY) to reduce recurrent admission and prolong survival: pragmatic, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9970):774–784. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61992-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stewart S, Carrington MJ, Marwick TH, Davidson PM, Macdonald P, Horowitz JD, et al. Impact of home versus clinic-based management of chronic heart failure: the WHICH? (Which Heart Failure Intervention Is Most Cost-Effective & Consumer Friendly in Reducing Hospital Care) multicenter, randomized trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(14):1239–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stewart S, Marley JE, Horowitz JD. Effects of a multidisciplinary, home-based intervention on unplanned readmissions and survival among patients with chronic congestive heart failure: a randomised controlled study. Lancet. 1999;354(9184):1077–1083. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)03428-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arnett DK, Goodman RA, Halperin JL, Anderson JL, Parekh AK, Zoghbi WA, AHA/ACC/HHS strategies to enhance application of clinical practice guidelines in patients with cardiovascular disease and comorbid conditions: from the American Heart Association American College of Cardiology, and US Department of Health and Human Services. Circulation. 2014;130(18):1662–1667. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blue L, Lang E, McMurray JJ, Davie AP, McDonagh TA, Murdoch DR, et al. Randomised controlled trial of specialist nurse intervention in heart failure. BMJ. 2001;323(7315):715–718. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7315.715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riegel B, Carlson B, Glaser D, Hoagland P. Which patients with heart failure respond best to multidisciplinary disease management? J Card Fail. 2000;6(4):290–299. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2000.19226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riegel B, Carlson B, Glaser D, Romero T. Randomized controlled trial of telephone case management in Hispanics of Mexican origin with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2006;12(3):211–219. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riegel B, Carlson B, Kopp Z, LePetri B, Glaser D, Unger A. Effect of a standardized nurse case-management telephone intervention on resource use in patients with chronic heart failure(see comment) Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(6):705–712. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.6.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ara S. A literature review of cardiovascular disease management programs in managed care populations. J Manag Care Pharm. 2004;10(4):326–344. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2004.10.4.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gohler A, Januzzi JL, Worrell SS, Osterziel KJ, Gazelle GS, Dietz R, et al. A systematic meta-analysis of the efficacy and heterogeneity of disease management programs in congestive heart failure. J Card Fail. 2006;12(7):554–567. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gonseth J, Guallar-Castillon P, Banegas JR, Rodriguez-Artalejo F. The effectiveness of disease management programmes in reducing hospital re-admission in older patients with heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of published reports. Eur Heart J. 2004;25(18):1570–1595. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leppin AL, Gionfriddo MR, Kessler M, Brito JP, Mair FS, Gallacher K, et al. Preventing 30-day hospital readmissions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1095–1107. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McAlister FA, Lawson FM, Teo KK, Armstrong PW. A systematic review of randomized trials of disease management programs in heart failure. Am J Med. 2001;110(5):378–384. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00743-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ofman JJ, Badamgarav E, Henning JM, Knight K, Gano AD, Jr, Levan RK, et al. Does disease management improve clinical and economic outcomes in patients with chronic diseases? A systematic review. Am J Med. 2004;117(3):182–192. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roccaforte R, Demers C, Baldassarre F, Teo KK, Yusuf S. Effectiveness of comprehensive disease management programmes in improving clinical outcomes in heart failure patients. A meta-analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2005;7(7):1133–1144. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Savard LA, Thompson DR, Clark AM. A meta-review of evidence on heart failure disease management programs: the challenges of describing and synthesizing evidence on complex interventions. Trials. 2011;12:194. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whellan DJ, Hasselblad V, Peterson E, O’Connor CM, Schulman KA. Metaanalysis and review of heart failure disease management randomized controlled clinical trials. Am Heart J. 2005;149(4):722–729. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kociol RD, Liang L, Hernandez AF, Curtis LH, Heidenreich PA, Yancy CW, et al. Are we targeting the right metric for heart failure? Comparison of hospital 30-day readmission rates and total episode of care inpatient days. Am Heart J. 2013;165(6):987–994 (e1). doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sochalski J, Jaarsma T, Krumholz HM, Laramee A, McMurray JJ, Naylor MD, et al. What works in chronic care management: the case of heart failure. Health Aff. 2009;28(1):179–189. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pefoyo AJ, Bronskill SE, Gruneir A, Calzavara A, Thavorn K, Petrosyan Y, et al. The increasing burden and complexity of multimorbidity. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:415. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1733-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schaufelberger M, Swedberg K, Koster M, Rosen M, Rosengren A. Decreasing one-year mortality and hospitalization rates for heart failure in Sweden; data from the Swedish Hospital Discharge Registry 1988 to 2000. Eur Heart J. 2004;25(4):300–307. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stewart S, MacIntyre K, Capewell S, McMurray JJ. Heart failure and the aging population: an increasing burden in the 21st century? Heart. 2003;89(1):49–53. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Driscoll A, Worrall-Carter L, Hare DL, Davidson PM, Riegel B, Tonkin A, et al. Evidence-based chronic heart failure management programs: reality or myth? Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(6):450–455. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2008.028035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McAlister FA, Stewart S, Ferrua S, McMurray JJ. Multidisciplinary strategies for the management of heart failure patients at high risk for admission: a systematic review of randomized trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(4):810–819. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krum H, Driscoll A. Management of heart failure. Med J Aust. 2013;199(5):334–339. doi: 10.5694/mja12.10993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jaarsma T, van der Wal MH, Lesman-Leegte I, Luttik ML, Hogenhuis J, Veeger NJ, et al. Effect of moderate or intensive disease management program on outcome in patients with heart failure: Coordinating Study Evaluating Outcomes of Advising and Counseling in Heart failure (COACH) Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(3):316–324. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chaudhry SI, Mattera JA, Curtis JP, Spertus JA, Herrin J, Lin Z, et al. Telemonitoring in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(24):2301–2309. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Freedland KE, Carney RM. Psychosocial considerations in elderly patients with heart failure. Clin Geriatr Med. 2000;16(3):649–661. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0690(05)70033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kerzner R, Rich MW. Management of heart failure in the elderly. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2003;5(3):223–228. doi: 10.1007/s11886-003-0053-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Norberg EB, Boman K, Lofgren B, Brannstrom M. Occupational performance and strategies for managing daily life among the elderly with heart failure. Scand J Occup Ther. 2014;21(5):392–399. doi: 10.3109/11038128.2014.911955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ather S, Chan W, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, Ramasubbu K, Zachariah AA, et al. Impact of noncardiac comorbidities on morbidity and mortality in a predominantly male population with heart failure and preserved versus reduced ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(11):998–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.11.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lang CC, Mancini DM. Non-cardiac comorbidities in chronic heart failure. Heart. 2007;93(6):665–671. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.068296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Valderas JM, Starfield B, Sibbald B, Salisbury C, Roland M. Defining comorbidity: implications for understanding health and health services. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(4):357–363. doi: 10.1370/afm.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moraska AR, Chamberlain AM, Shah ND, Vickers KS, Rummans TA, Dunlay SM, et al. Depression, healthcare utilization, and death in heart failure: a community study. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(3):387–394. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.000118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Radhakrishnan K, Bowles K, Hanlon A, Topaz M, Chittams J. A retrospective study on patient characteristics and telehealth alerts indicative of key medical events for heart failure patients at a home health agency. Telemed J E Health. 2013;19(9):664–670. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2012.0307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Retrum JH, Boggs J, Hersh A, Wright L, Main DS, Magid DJ, et al. Patient-identified factors related to heart failure readmissions. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(2):171–177. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.967356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stewart S, Wiley J, Chan YK, Ball J, Thompson DR, Carrington MJ. Late-Breaking Clinical Trial Presentation. European Society of Cardiology Scientific Congress; London, UK: 2015. Prolonged event-free survival in more complex cases of heart disease: outcome data from 1,226 patients from 3 randomised trials of nurse-led, multidisciplinary home-based intervention. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stewart S, Carrington MJ, Horowitz JD, Marwick TH, Newton PJ, Davidson PM, et al. Prolonged impact of home versus clinic-based management of chronic heart failure: extended follow-up of a pragmatic, multicentre randomized trial cohort. Int J Cardiol. 2014;174(3):600–610. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.04.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sweeney L, Halpert A, Waranoff J. Patient-centered management of complex patients can reduce costs without shortening life. Am J Manag Care. 2007;13(2):84–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Naylor MD, Brooten DA, Campbell RL, Maislin G, McCauley KM, Schwartz JS. Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(5):675–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dunbar SB, Reilly CM, Gary R, Higgins MK, Culler S, Butts B, et al. Randomized clinical trial of an integrated self-care intervention for persons with heart failure and diabetes: quality of life and physical functioning outcomes. J Card Fail. 2015;21(9):719–729. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Granger BB, Ekman I, Hernandez AF, Sawyer T, Bowers MT, DeWald TA, et al. Results of the chronic heart failure intervention to improve MEdication adherence study: a randomized intervention in high-risk patients. Am Heart J. 2015;169(4):539–548. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Reed SD, Neilson MP, Gardner M, Li Y, Briggs AH, Polsky DE, et al. Tools for economic analysis of patient management interventions in heart failure cost-effectiveness model: a web-based program designed to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of disease management programs in heart failure. Am Heart J. 2015;170(5):951–960. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Reilly CM, Butler J, Culler SD, Gary RA, Higgins M, Schindler P, et al. An economic evaluation of a self-care intervention in persons with heart failure and diabetes. J Card Fail. 2015;21(9):730–737. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2015.06.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pauly MV. Accountable care organizations and kidney disease care: health reform innovation or more same-old, same-old? Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(4):524–529. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Metzelthin SF, van Rossum E, de Witte LP, Ambergen AW, Hobma SO, Sipers W, et al. Effectiveness of interdisciplinary primary care approach to reduce disability in community dwelling frail older people: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2013;347:f5264. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rosenberg T. Acute hospital use, nursing home placement, and mortality in a frail community-dwelling cohort managed with primary integrated interdisciplinary elder care at home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(7):1340–1346. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Page TF, Amofah SA, McCann S, Rivo J, Varghese A, James T, et al. Care Management Medical Home Center model: preliminary results of a patient-centered approach to improving care quality for diabetic patients. Health Promot Pract. 2015;16(4):609–616. doi: 10.1177/1524839914565021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Boult C, Reider L, Leff B, Frick KD, Boyd CM, Wolff JL, et al. The effect of guided care teams on the use of health services: results from a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(5):460–466. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Boyd CM, Boult C, Shadmi E, Leff B, Brager R, Dunbar L, et al. Guided care for multimorbid older adults. Gerontologist. 2007;47(5):697–704. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.5.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Leff B, Reider L, Frick KD, Scharfstein DO, Boyd CM, Frey K, et al. Guided care and the cost of complex healthcare: a preliminary report. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(8):555–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hollingsworth JM, Saint S, Hayward RA, Rogers MA, Zhang L, Miller DC. Specialty care and the patient-centered medical home. Med Care. 2011;49(1):4–9. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181f537b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Services Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. USA: 2014. Independance at Home Demonstration. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Szanton SL, Roth J, Nkimbeng M, Savage J, Klimmek R. Improving unsafe environments to support aging independence with limited resources. Nurs Clin N Am. 2014;49(2):133–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Szanton SL, Wolff JW, Leff B, Thorpe RJ, Tanner EK, Boyd C, et al. CAPABLE trial: a randomized controlled trial of nurse, occupational therapist and handyman to reduce disability among older adults: rationale and design. Contemp Clin Trials. 2014;38(1):102–112. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Riegel B, Dickson VV. A situation-specific theory of heart failure self-care. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008;23(3):190–196. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000305091.35259.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Riegel B, Dickson VV, Faulkner KM. The situation-specific theory of heart failure self-care: revised and updated. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2015 doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000244. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Riegel B, Jaarsma T, Stromberg A. A middle-range theory of self-care of chronic illness, ANS Adv. Nurs Sci. 2012;35(3):194–204. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0b013e318261b1ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dickson VV, Buck H, Riegel B. Multiple comorbid conditions challenge heart failure self-care by decreasing self-efficacy. Nurs Res. 2013;62(1):2–9. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e31827337b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dickson VV, Deatrick JA, Riegel B. A typology of heart failure self-care management in non-elders. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008;7(3):171–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dickson VV, Tkacs N, Riegel B. Cognitive influences on self-care decision making in persons with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2007;154(3):424–431. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.04.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Riegel B, Carlson B. Facilitators and barriers to heart failure self-care. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;46:287–295. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00165-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Riegel B, Lee CS, Albert N, Lennie T, Chung M, Song EK, et al. From novice to expert: confidence and activity status determine heart failure self-care performance. Nurs Res. 2011;60(2):132–138. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e31820978ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dickson VV, Melkus GD, Katz S, Levine-Wong A, Dillworth J, Cleland CM, et al. Building skill in heart failure self-care among community dwelling older adults: results of a pilot study. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;96(2):188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dickson VV, Nocella J, Yoon HW, Hammer M, Melkus GD, Chyun D. Cardiovascular disease self-care interventions. Nurs Res Pract. 2013;2013:407608. doi: 10.1155/2013/407608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dickson VV, Riegel B. Are we teaching what patients need to know? Building skills in heart failure self-care. Heart Lung. 2009;38(3):253–261. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Creber R Masterson, Patey M, Dickson VV, DeCesaris M, Riegel B. Motivational Interviewing Tailored Interventions for Heart Failure (MITI-HF): study design and methods. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;41:62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2014.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Creber R Masterson, Patey M, Lee CS, Kuan A, Riegel B. Motivational Interviewing Tailored Interventions for Heart Failure (MITI-HF): randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.08.031. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Creber R Masterson, Patey M, Lee CS, Kuan A, Jurgens C, Riegel B. Motivational interviewing to improve self-care for patients with chronic heart failure: MITI-HF randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.08.031. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lee CS, Carlson B, Riegel B. Heart failure self-care improves economic outcomes, but only when self-care confidence is high. J Card Fail. 2007;13(6):S75. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lee CS, Moser DK, Lennie TA, Riegel B. Event-free survival in adults with heart failure who engage in self-care management. Heart Lung. 2011;40(1):12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lee CS, Moser DK, Lennie TA, Tkacs NC, Margulies KB, Riegel B. Biomarkers of myocardial stress and systemic inflammation in patients who engage in heart failure self-care management. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011;26(4):321–328. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e31820344be. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dickson VV, Buck H, Riegel B. A qualitative meta-analysis of heart failure self-care practices among individuals with multiple comorbid conditions. J Card Fail. 2011;17(5):413–419. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Doherty LC, Fitzsimons D, McIlfatrick SJ. Carers’ needs in advanced heart failure: a systematic narrative review. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2015 doi: 10.1177/1474515115585237. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Browne S, Macdonald S, May CR, Macleod U, Mair FS. Patient, carer and professional perspectives on barriers and facilitators to quality care in advanced heart failure. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e93288. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Commission for Case Manager Certification. 2014 [September 27, 2014]. Available from: http://ccmcertification.org/

- 100.Beck C, McSweeney JC, Richards KC, Roberson PK, Tsai PF, Souder E. Challenges in tailored intervention research. Nurs Outlook. 2010;58(2):104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gary R. Evaluation of frailty in older adults with cardiovascular disease: incorporating physical performance measures. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2012;27(2):120–131. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e318239f4a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Knocke A. Program description: physical therapy in a heart failure clinic, Cardiopulm. Phys Ther J. 2012;23(3):46–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Taylor RS, Dalal H, Jolly K, Moxham T, Zawada A. Home-based versus centre-based cardiac rehabilitation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;1:CD007130. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007130.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Dalal HM, Zawada A, Jolly K, Moxham T, Taylor RS. Home based versus centre based cardiac rehabilitation: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;340:b5631. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b5631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.McDonald K, Sundaram V, Bravada D, Lewis R, Lin N, Kraft S, et al. In closing the quality gap: a critical analysis of quality improvement strategies technical review 9, 290-02-0017) Prepared by: Stanford-UCSF Evidence-Based Practice Center. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: 2007. Care coordination. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.National Quality Forum (NQF) Preferred Practices and Performance Measures for Measuring and Reporting Care Coordination: A Consensus Report. Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Frank C, Weir E. Deprescribing for older patients. CMAJ. 2014;186(18):1369–1376. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.131873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Reeve E, To J, Hendrix I, Shakib S, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. Patient barriers to and enablers of deprescribing: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(10):793–807. doi: 10.1007/s40266-013-0106-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Allen LA, Tomic KE Smoyer, Smith DM, Wilson KL, Agodoa I. Rates and predictors of 30-day readmission among commercially insured and Medicaid-enrolled patients hospitalized with systolic heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5(6):672–679. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.967356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Bradley EH, Curry L, Horwitz LI, Sipsma H, Wang Y, Walsh MN, et al. Hospital strategies associated with 30-day readmission rates for patients with heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(4):444–450. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.000101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hernandez MB, Schwartz RS, Asher CR, Navas EV, Totfalusi V, Buitrago I, et al. Predictors of 30-day readmission in patients hospitalized with decompensated heart failure. Clin Cardiol. 2013;36(9):542–547. doi: 10.1002/clc.22180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wexler R. Early physician follow-up and 30-day readmission among older patients with heart failure. JAMA. 2010;304(7):743. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1147. (author reply -4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Goodlin SJ. Palliative care in congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(5):386–396. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ironside PM, Tagliareni ME, McLaughlin B, King E, Mengel A. Fostering geriatrics in associate degree nursing education: an assessment of current curricula and clinical experiences. J Nurs Educ. 2010;49(5):246–252. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20100217-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Developing Tools and Data for Research and Policymaking. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wall BT, Dirks ML, van Loon LJ. Skeletal muscle atrophy during short-term disuse: implications for age-related sarcopenia. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12(4):898–906. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Cuthbertson D, Smith K, Babraj J, Leese G, Waddell T, Atherton P, et al. Anabolic signaling deficits underlie amino acid resistance of wasting, aging muscle. FASEB J. 2005;19(3):422–424. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2640fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Needham DM. Mobilizing patients in the intensive care unit: improving neuromuscular weakness and physical function. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1685–1690. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Stall N. Tackling immobility in hospitalized seniors. CMAJ. 2012;184(15):1666–1667. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-4281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Brown-O’Hara T. Geriatric syndromes and their implications for nursing. Nursing. 2013;1–3 doi: 10.1097/01.NURSE.0000423097.95416.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Parekh AK, Goodman RA, Gordon C, Koh HK. The HHS, Interagency workgroup on multiple chronic conditions. managing multiple chronic conditions: a strategic framework for improving health outcomes and quality of life. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(4):460–471. doi: 10.1177/003335491112600403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Parekh AK, Kronick R, Tavenner M. Optimizing health for persons with multiple chronic conditions. JAMA. 2014;312(12):1199–1200. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.10181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.US Department of Health and Human Services. Multiple Chronic Conditions — A Strategic Framework: Optimum Health and Quality of Life for Individuals with Multiple Chronic Conditions. Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 124.McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, Auricchio A, Bohm M, Dickstein K, et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart failure 2012 of the European Society Of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14(8):803–869. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Jr, Drazner MH, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management Of heart failure: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(16):e147–e239. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Pasricha SR, Flecknoe-Brown SC, Allen KJ, Gibson PR, McMahon LP, Olynyk JK, et al. Diagnosis and management of iron deficiency anaemia: a clinical update. Med J Aust. 2010;193(9):525–532. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb04038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Gregoratos G, Cheitlin MD, Conill A, Epstein AE, Fellows C, Ferguson TB, Jr, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for implantation of cardiac pacemakers and antiarrhythmia devices: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines (committee on pacemaker implantation) J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31(5):1175–1209. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Doerflinger DMC. Mental Status Assessment in Older Adults: Montreal Cognitive Assessment: MoCA Version 7.1 (Original Version) Virginia: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Lowe B, Wahl I, Rose M, Spitzer C, Glaesmer H, Wingenfeld K, et al. A 4-item measure of depression and anxiety: validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2010;122(1–2):86–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Rutledge T, Reis VA, Linke SE, Greenberg BH, Mills PJ. Depression in heart failure a meta-analytic review of prevalence, intervention effects, and associations with clinical outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(8):1527–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Zamora E, Lupon J, Vila J, Urrutia A, de Antonio M, Sanz H, et al. Estimated glomerular filtration rate and prognosis in heart failure: value of the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study-4, chronic kidney disease epidemiology collaboration, and cockroftgault formulas. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(19):1709–1715. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Celli BR, MacNee W. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J. 2004;23(6):932–946. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00014304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Gerdes AM, Iervasi G. Thyroid replacement therapy and heart failure. Circulation. 2010;122(4):385–393. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.917922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Sharma S, Mather P, Efird JT, Kahn D, Cheema M, Rubin S, et al. Photoplethysmographic signal to screen sleep-disordered breathing in hospitalized heart failure patients: feasibility of a prospective clinical pathway. JACC Heart Fail. 2015;3(9):725–731. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2015.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.