Abstract

The aim of the current study was to create a new measure of parenting practices, constituted by items from already established measures, to advance the measurement of parenting practices in clinical and research settings. Five stages were utilized to select optimal parenting items, establish a factor structure consisting of positive and negative dimensions of parenting, meaningfully consider child developmental stage, and ensure strong psychometric properties (reliability and validity) of the final measure. A total of 1,790 parents (44% fathers) were recruited online through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk for three cohorts: Stages 1 (N = 611), 2 (N = 615), and 3 (N = 564). Each sample was equally divided by child developmental stage: Young childhood (3 to 7 years old), middle childhood (8 to 12 years old), and adolescence (13 to 17 years old). Through the five-stage empirical approach, the Multidimensional Assessment of Parenting Scale (MAPS) was developed, successfully achieving all aims. The MAPS factor structure included both positive and negative dimensions of warmth/hostility and behavioral control that were appropriate for parents of children across the developmental span. The MAPS demonstrated strong reliability and longitudinal analyses provided initial support for the validity of MAPS subscales

Keywords: parenting, assessment

Introduction

One of the most studied and well-established themes of psychological research is the importance of family functioning for children’s cognitive, social, and emotional development (Lovejoy, Weis, O’Hare, & Rubin, 1999). In particular, any theoretical model or empirical research designed to explain the development of child psychosocial adjustment (e.g., child noncompliance, anxiety) must account for the influence of parenting, either directly or indirectly (McKee, Jones, Forehand, & Cuellar, 2013). This assumption has been substantiated by significant empirical support for the reliable and robust associations between parenting practices and child psychopathology (e.g., Chorpita & Barlow, 1998; Hoeve et al., 2009).

Despite the variation in child outcomes in response to the parenting variables examined, researchers studying parenting have focused on remarkably similar parenting dimensions (Darling & Steinberg, 1999; McKee et al., 2013). The most prominent theoretical conceptualization focusing solely on parenting domains was offered by Schaefer (1959) who synthesized early parenting research and formulated a circumplex model of maternal behavior. Schaefer used factor analyses across samples to support a hierarchical model of parenting behavior with two broadband domains of love (warmth) versus hostility and autonomy versus control. Schaefer’s model aimed to create a parsimonious nomological network of parenting such that all narrowband parenting domains could be placed in the model based on the behavior’s degree of warmth/hostility and autonomy/control. Consistent with Schaefer’s (1959) conceptualization, three key dimensions have emerged as the primary elements of parenting: warmth (e.g., affection, involvement, supportiveness, attentiveness, acceptance); hostility (e.g., harshness, irritability, intrusiveness); and behavioral control, ranging from over- (e.g., physical punishment) to under- (e.g., lax control) control. There are numerous empirical investigations linking these specific parenting dimensions to specific child outcomes (see Cummings, Davies, & Campbell, 2000; Holden, 1997; Rapee, 2012, for reviews).

Assessment is a fundamental element in scientific research as the interpretation of parenting studies depends heavily on the assessment methods used and the confidence one can place in these measures (Kazdin, 2003). Despite substantial theory and research related to parenting, there is very little agreement on how best to measure parenting (Locke & Prinz, 2002). Direct observations of parent-child interactions by independent raters are often seen as the “gold standard” for the reliable, objective assessment of parenting (McKee et al., 2013; Taber, 2010). However, observations are time-consuming, costly to collect and code (Lovejoy et al., 1999), and often lack external validity (e.g., collected in a contrived setting such as a university) (Gardner, 2000). Alternatively, questionnaire measurement of parenting behaviors provides a more economical and feasible method for broad use in research and clinical settings (e.g., Ramey, 2012), as well as potentially capturing a broader range of parenting behaviors than might be exhibited during a one-time observation.

Unfortunately, the validity and reliability of questionnaire-reported parenting are not without issue as has been commonly cited over the past three decades (e.g., Morsbach & Prinz, 2006; Parent et al., 2014). Primarily, researchers have consistently pointed to the need for multidimensional, high-utility parenting measures that have strong psychometric properties (i.e., reliability and validity) and are sensitive to changes in parenting across child development (Locke & Prinz, 2002; O’Connor, 2002).

The strength of psychometric properties of questionnaire-reported parenting has been called into question (e.g., Hurley, Huscroft-D’Angelo, Trout, Griffith, & Epstien, 2014; Locke & Prinz, 2002; Morsbach & Prinz, 2006). Hurley et al (2014) described the preponderance of flawed parenting measures, concluding that the current state-of-the-field is “dismal” (p. 820). Issues with reliability are of particular concern given that almost all parenting measures have at least one subscale that has been consistently shown to have an internal consistency coefficient (most often alpha) below .80, the commonly cited minimum value for good reliability (Nunnally, 1978; Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). Further, a review of the last five years of parenting research published in top journals (e.g., Child Development, Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry) found that, even in a limited review of top journals, 84% of studies yielded parenting questionnaire reliability estimates below .80 (Stanger, Parent, & Pomerantz, 2016). Lower reliability may reduce power to detect true differences due to the impact of error variance on effect sizes (Kazdin, 2003) and “there is virtual consensus among researchers that, for a scale to be valid and possess practical utility, it must be reliable” (Peterson, 1994, p. 381).

Few measures tap both the positive and negative dimensions of parenting that might be relevant to the etiology and course of common childhood and adolescent disorders (Darling & Steinberg, 1996). For broad adoption of a parenting measure by both researchers and clinicians, the measure must be relatively brief and assess multiple domains of parenting in a single instrument. For example, the Parenting Scale (Arnold, O’Leary, Wolff, & Acker, 1993) has established strong psychometric properties for two types of dysfunctional disciplinary practices of parents with young children but does not include items assessing positive parenting practices such as warmth. Given that both positive and negative parenting practices are of interest to researchers and clinicians, use of the Parenting Scale would require use of another measure that assesses positive dimensions.

The standard of a high utility measure combined with the requirement for strong psychometric characteristics excludes many of the established parenting measures. For example, the Parenting Practices Questionnaire (Robinson, Mandleco, Olsen, & Hart, 1995) assess both positive and negative parenting practices; however, this measure lacks strong psychometrically defensible scales (e.g., coefficient alpha at or above .80 in each domain) in both the positive and negative domains. This criterion results in most of the commonly used measures being excluded because the use of one of these measures requires the supplemental use of another parenting measure to compensate for issues with the first.

Another issue common in the assessment of parenting is lack of sensitivity to shifts in parenting practices across child development. While some parenting practices remain constant throughout childhood, others change drastically as children develop, some are discontinued altogether, and others are newly introduced in later developmental stages. Given that there is substantial change in the challenges faced by children across development and, in turn, changes in the role and challenges of the caregiver (Cummings et al., 2000), it is universally accepted that parenting changes occur across child development (Locke & Prinz, 2002). However, parenting questionnaires do not reflect this flexibility, as most ignore child developmental stage. Some measures limit the age range, which circumvents this issue, but doing so precludes the examination of change over the course of development, which is the question of foremost interest to child clinical and developmental psychologists (Cummings et al., 2000). Other measures are used for a wide range of ages without established measurement invariance, inappropriately utilizing the same items to assess parenting of a 3- and 16-year-old. No current parenting measure passes all three criterion reviewed (i.e., strong reliability of both positive and negative dimensions with established measurement invariance across child developmental stages).

In the past century, there have been over 30,000 scholarly publications in the broad area of parenting. Despite this history, the field is and will continue to be limited by the lack of a well-established comprehensive multi-dimensional measure of parenting practices that evidences strong psychometric properties. With the continued emphasis on evidence-based treatments for childhood disorders, many of which involve a parenting component, an emphasis also should be placed on evidence-based assessment of parenting. Thus, the field is in need of an empirically-based measure of parenting practices that addresses the above-mentioned issues to advance the measurement of parenting practices in clinical and research settings.

Although no single measure currently suffices for comprehensive multidimensional assessment of parenting, there is substantial utility to items within current parenting practices questionnaires. These items are often theoretically informed and were designed by some of the foremost researchers of the last 50 years of parenting research. Thus, one way to improve parenting practices assessment could be to draw upon the best available parenting questionnaires. By beginning measure development with items from established parenting scales, the resulting measure would include items that already have hundreds of studies supporting their validity. Further, measurement development starting from existing measures developed for use with a range of child developmental stages would be well-suited to establish factor structure with parents of children across several key developmental stages (e.g., young childhood, middle childhood, and adolescence). Such an approach will allow for better developmental mapping of parenting and norms sensitive to child age.

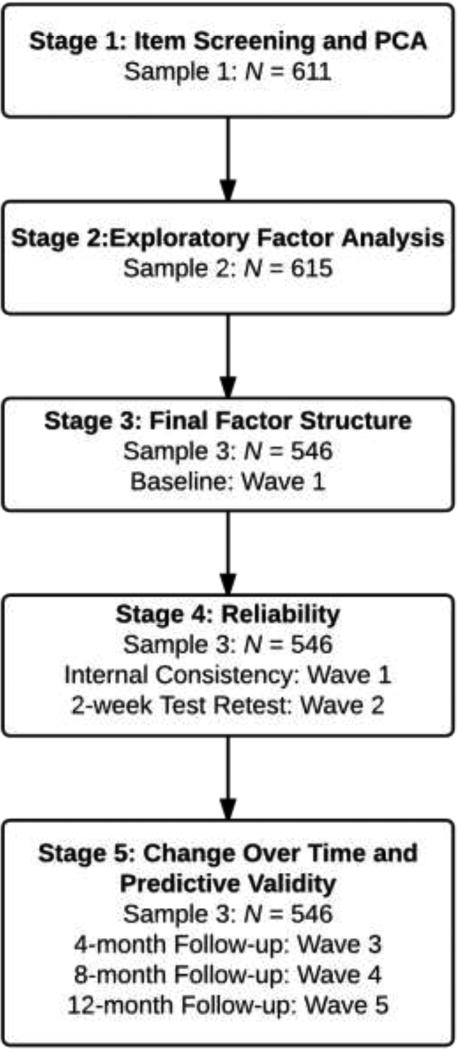

The aim of the current study was to create a new measure of parenting practices, constituted by items from already established measures, to advance the measurement of parenting practices in clinical and research settings. The current study consists of five stages that are delineated in Figure 1. Stage 1 entailed the administration of the initial 179 parenting items from eight established parenting scales to 611 parents of children, ages 3 to 17. The primary goal of Stage 1 was item reduction, whereby the item pool was reduced to a manageable size by eliminating items with limited variability. Stage 2 involved administering the items retained in stage 1 to a second sample of 615 parents. The primary goal of stage 2 was to further distill the number of parenting items to a more meaningful set and explore the underlying factor structure of the data. Stage 3 entailed administration of the items retained in stage 2 to a third separate sample of 564 parents. The primary goal of stage 3 was to construct an explicit model of the factor structure underlying the data and to statistically test fit. Stages 4 and 5 involved short-term longitudinal follow-up of the sample recruited in stage 3. The primary goal of stage 4 was to assess internal and two-week test-retest reliability, and the primary goal of the 5th stage was to provide initial support for validity utilizing data from four assessments across 12 months.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the five stages.

The first three stages of measurement development in the current study borrowed from the Achenbach System of Empirical-Based Assessment (ASEBA) developmental model (Achenbach, 2009) emphasizing empirically-based methods and data to theoretical conceptualizations. Nevertheless, a strong theoretical and conceptual model of parenting was the strong foundation by which the source parenting measures were built on. Recognizing the importance of the relationship between theory and empirical data, the current study started from theoretically-informed items, then used an empirical approach for obtaining the final factor structure, and finally, concludes with a discussion of theoretical implications (i.e. from theory to data and back to theory). Stemming from this approach, one of the primary aims of the current study was to provide conceptual clarity to the measuring of parenting practices and, in turn, provide road maps for new research and theory.

Method

Participants

For the current study, 1,790 parents were recruited online through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) for three cohorts: Stages 1 (N = 611), 2 (N = 615), and 3 (N = 564) (see Figure 1). For each stage parents responded to a study that was listed separately for three age groups to ensure approximately equal sample sizes in each group: young childhood (3 to 7 years old), middle childhood (8 to 12 years old), and adolescence (13 to 17 years old). MTurk is currently the dominant crowdsourcing application in social sciences (Chandler, Mueller, & Paolacci, 2014). Prior research has convincingly demonstrated that data obtained via crowdsourcing methods are as reliable and valid as those obtained via more traditional data collection methods (e.g., Buhrmester, Kwang, & Gosling, 2011; Casler, Bickel, & Hackett, 2013). Recently, research has also demonstrated reliability and validity of crowdsourcing methods for child and family studies (Parent, Forehand, Pomerantz, Peisch, & Seehuus, in press).

Stage 1 participants

Data from 611 parents of children between the ages of 3 and 17 were included in the first stage. Sample demographics by developmental stage (young childhood, middle childhood, and adolescent samples) are presented in the Supplemental Appendix. Overall, parents were an average of 34 years old (SD = 7.66) and were roughly equally represented by mothers and fathers (52.7 % mothers). Participants were predominately White (77.0%), with an additional 7.9% who identified as Black, 8.3% as Latino/Hispanic, 5.8% as Asian, and 1% as American Indian, Alaska Native, or other Pacific Islander. Parents’ education levels included not completing high school or equivalent (0.3%), obtaining a H.S. degree or GED (12.8%), attending some college (32.1%), earning a college degree (39%), and attending at least some graduate school (15.8%). Parents employment included full-time (64%), part-time (21.6%), and unemployed (14.4%). Reported family income ranged included less than $30,000 per year (15.1%), between $30,000 and $40,000 (15.7%), between $40,000 and $60,000 (25.7%), between $60,000 and $100,000 (24.2%), and at least $100,000 (10.1%) per year. Parent marital status included single (not living with a romantic partner) (18.1%), married (66.6%), and cohabiting (i.e., living with a romantic partner but not married) (15.3%). Over half of youth were boys (57%), with 38% being an only child.

Stage 2 participants

Data from 615 parents of children between the ages of 3 and 17 were included in the second stage. Sample demographics by developmental stage are presented in the Supplemental Appendix and mirrored those of stage 1.

Stages 3 – 5 participants

Data from 564 parents of children between the ages of 3 and 17 were included in stages 3–5. Sample demographics by developmental stage are presented in the Supplemental Appendix for participants at the baseline assessment. Overall, demographic characteristics of this sample mirrored those of stages 1 and 2.

Procedure

All study procedures were approved by a university Institutional Review Board (IRB). Parents were consented online before beginning the survey in accordance with the approved IRB procedures. For both the first and second stages, three different studies were listed on MTurk (one for each child age range) and offered $2.00 in compensation. For the third through fifth stages, three different studies were listed on MTurk (one for each child age range) describing a year-long study involving the completion of five surveys (baseline, 2 week, 4 month, 8 month, and 12 month follow-ups) over the course of 12 months. Participants were compensated $4.00, $2.00, $4.00, $4.00, and $8.00 for participating in baseline, two-week, 4-month, 8-month, and 12-month surveys, respectively. For follow-up surveys, participants were contacted using an MTurk ID to complete surveys. One email was sent the day prior to the survey being available, one email was sent the day the survey became available, and two to three emails were sent subsequently if follow-up survey bad not been completed. For families with multiple children in the target age range, one child was randomly selected through a computer algorithm and measures were asked in reference to parenting specific to this child and her/his behavior. Further details about MTurk recruitment is available in the online Supplemental Appendix.

Measures

Overview

In stage 1, parenting items were administered. In stage 2, the parenting items remaining after stage 1 were administered. In stages 3 and 5, the parenting items remaining after stage 2 and the child outcome measures were administered. In stage 4, the parenting items used in stages 3 through 5 were re-administered.

Stage 1 parenting measures

Eight exemplar parenting questionnaires were selected for inclusion in the study. An exhaustive inclusion of all parenting measures was not possible but the choice of these eight scales was guided by five criteria: (1) freely available; (2) commonly used and cited based on PsycINFO searches of research on parenting published in top psychological journals; (3) representation of key parenting constructs within the warmth, behavioral control, and hostile behavior domains (not necessarily all); (4) a format amenable to being merged into a single measure; and (5) having a parent-report version of the scale that is relatively brief (e.g., < 100 items). The eight measures chosen were: The Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (Shelton, Frick, & Wootton, 1996), the Parenting Practices Questionnaire (Robinson et al., 1995); The Parenting Scale (Arnold et al., 1993); the Management of Children’s Behavior Scale (Pereppletchikova & Kazdin, 2004); the Children’s Report of Parenting Behavior Inventory (Shaefer, 1965), the Parent Behavior Inventory (Lovejoy et al., 1999); the Parenting Young Children scale (McEachern et al., 2012); and the Parental Monitoring Scale (Stattin & Kerr, 2000). Further information about these measures and their psychometric properties can be found in the online Supplemental Appendix.

Modifications to parenting questionnaires

All parenting items went through four steps of adaptations. First, items across all eight parenting measures were compiled and converted to a 5-point Likert scale with universal anchors (1 = “Never” to 5 = “Always”). Second, when necessary, item content was adapted to fit the universal Likert scale (e.g., “I am a person who is not very patient with my child” on a 0 “Not like me” to 2 “A lot like me” scale was converted to “I am not very patient with my child” on a 1 “Never” to 5 “Always” scale). Third, some items were modified for clarity by the authors. Lastly, universal instructions were chosen for completing all items and the timeframe for which parenting was reported was set to the past two months. See the online Supplemental Appendix for the final items administered.

Child internalizing and externalizing problems

The parent form of the 19-item Brief Problem Monitor (BPM; Achenbach, McConaughy, Ivanova, & Rescorla, 2011) measured youth internalizing and externalizing problems. The BPM internalizing and externalizing items were selected from the CBCL/6–18 and YSR (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) using item response theory and factor analysis (Chorpita et al., 2010). The internal consistency and test–retest reliability of the BPM are excellent (Achenbach et al., 2011; Chorpita et al., 2010). Reliability coefficient omega for internalizing and externalizing problems ranged from .80 to .85 in the current study. Internalizing and externalizing psychopathology outcomes were assessed in stages 3 and 5 at waves 1 (baseline), 3 (4 months), 4 (8 months), and 5 (12 months).

Data Analysis Plan

Analyses for scale development were performed separately by youth development stage: young childhood, middle childhood, and adolescence. The framework for the methods and statistical procedures are derived from recommendations by Brown (2006) and Matsunaga (2010). These recommendations guided the decision to recruit three separate samples for the first three stages of analysis: stage 1, screening items and principal components analysis (PCA); stage 2, exploratory factor analysis (EFA); and stage 3, exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM). The primary goal of stage 1 was item reduction by use of PCA in order to reduce the item pool to a more manageable size. The primary goal of stage 2 was to explore the underlying factor structure of the data by use of EFA. The primary goal of stage 3 was to construct an explicit model of the factor structure underlying the data and statistically test its fit by the use of ESEM. Finally, the decision to include the 4th (internal and test-retest reliability) and 5th stages (longitudinal analysis of change over time) is based on recommendations of Kazdin (2003) and DeVellis (2012) for developing new measures by establishing reliability and providing initial support for validity.

Results

Stage 1 – Reducing item pool

Overview

For stages 1 and 2, parallel analysis (PA), the most accurate factor retention method (e.g., Henson & Roberts, 2006), was used to determine the number of factors to retain based on recommendations by Matsunaga (2010). The web-based parallel analysis engine by Patil et al (2007) is used in the current study to perform PA analyses.

Initial steps

First, modifications to the 240 items from the eight parenting measures were made as outlined above. Next, by expert consensus, redundant or repetitive items were deleted. This process included identifying potential overlap in item content followed by the review of these items by an expert in parenting. After items of very similar content and wording were finalized, the authors identified the best item within a set of similar items to be retained, or in the case of nearly identical content, an item was chosen at random. This reduced the pool of items and prevented artificial factors emerging in factor analyses due to similarity in item wording and content.

Item reduction

Next, the modified pool of items (179) was administered to the stage 1 sample of 611 parents. All analyses were completed separately by developmental stage. Of the nearly 179 items, the top 100 items with the largest variability within each sample were selected in order to limit potential ceiling and floor effects (e.g., items with a mean score of 4.5 and S.D. of .5 were dropped). Lastly, PCA, using promax rotation (oblique rotation) and PA, was employed to determine which items to eliminate (i.e., items without factor loadings > .40 on any component). Items retained after this process for any of the three stages (104 items in total) were then included in the item pool for the second stage. See the online Supplemental Appendix for a detailed overview of eliminated and retained items.

Stage 2 – Further item trimming and initial factor structure

Overview

Next, the items retained from stage 1 were administered to the stage 2 sample of 615 parents. These items were subjected to EFA separately by developmental stage. Specifically, PA was employed to determine the number of factors, after which items with factor loadings below .50 and/or with cross-loadings above .30 were dropped. These stringent criteria were chosen to trim the number of items to ensure that the final measure was relatively brief given the demand for short but psychometrically strong measures (Ebesutani et al., 2012). EFA analyses were conducted using maximum likelihood estimation with geomin rotation (oblique rotation) in Mplus version 6.1. As recommended by Brown (2006, p. 38), this analysis was an iterative process which was re-run several times with items being dropped each time until all remaining items met the criteria above. Items retained after this process for any of the three samples were then included in the item pool for the third stage for all developmental stages.

Initial factor structure

See the online Supplemental Appendix for the final EFA results for each child developmental stage. The number and composition of the final latent factors were further informed by item-level correlations, also available in the Supplemental Appendix. Based on EFA results and inspection of the item-level correlations across all three child developmental stages, a Broadband Positive Parenting factor emerged constituted by four narrowband subscales: Proactive Parenting (e.g., “I tell my child my expectations regarding behavior before my child engages in an activity”; “I avoid struggles with my child by giving clear choices”); Positive Reinforcement (e.g., “If I give my child a request and she/he carries out the request, I praise her/him for listening and complying”); Warmth (e.g., “I express affection by hugging, kissing, and holding my child”); and Supportiveness (e.g., “I show respect for my child’s opinions by encouraging him/her to express them”). Also consistent across stages and analyses was a Physical Control factor [e.g., “I use physical punishment (for example, spanking) to discipline my child because other things I have tried have not worked”].

Though inconsistent by developmental stage in EFA analyses, inspection of item level correlations across all three stages supported distinct Hostility and Lax Control factors. The Hostility factor included items representing intrusive parenting (e.g., “When I am upset or under stress, I am picky and on my child’s back”), harshness (e.g., “I yell or shout when my child misbehaves”), ineffective discipline (e.g., “I use threats as punishment with little or no justification”), and irritability (e.g., I explode in anger toward my child”). The Lax Control factor included items representing easily coerced behavior (e.g., “If my child whines or complains when I take away a privilege, I will give it back”), permissiveness (e.g., “I am the kind of parent who lets my child do whatever he/she wants”), and inconsistency [e.g., “I let my child out of a punishment early (like lift restrictions earlier than I originally said)”].

At this point, items that did not fit within any of the above factors were eliminated. This included items that were highly correlated with items within different factors (e.g., broad positive parenting items that could have fit in several of the narrowband scales) and four firm control items (e.g., “I believe in having a lot of rules and sticking with them”) that only emerged in the adolescent EFA model as well as being correlated with items within both control factors across developmental stages. Further, the Lax and Physical Control factors each had a large number of items with similar content. Thus, in order to further reduce the total number of items and reduce item redundancy, items within each of these factors were eliminated based on lower correlations with other items within its factor.

Stage 3 – Final factor structure

Overview

Next, the items retained from stage 2 were administered to the stage 3 sample of 564 parents. An ESEM approach was utilized to confirm and test the factor structure derived from stage 2. ESEM is an overarching integration of the best aspects of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), structural equation modeling (SEM), and traditional EFA (see Marsh, Morin, Parker, & Kaur, 2014, for a review). Further, ESEM is preferable over traditional CFA approaches because CFAs typically produce inflated factor correlations compared to ESEMs due to misfit associated with overly restrictive measurement models with no crossloadings (Marsh et al., 2014). ESEM allowed for the estimation of the proposed factor structure in the total sample (N = 564) followed by multiple-groups models testing measurement invariance across stages.

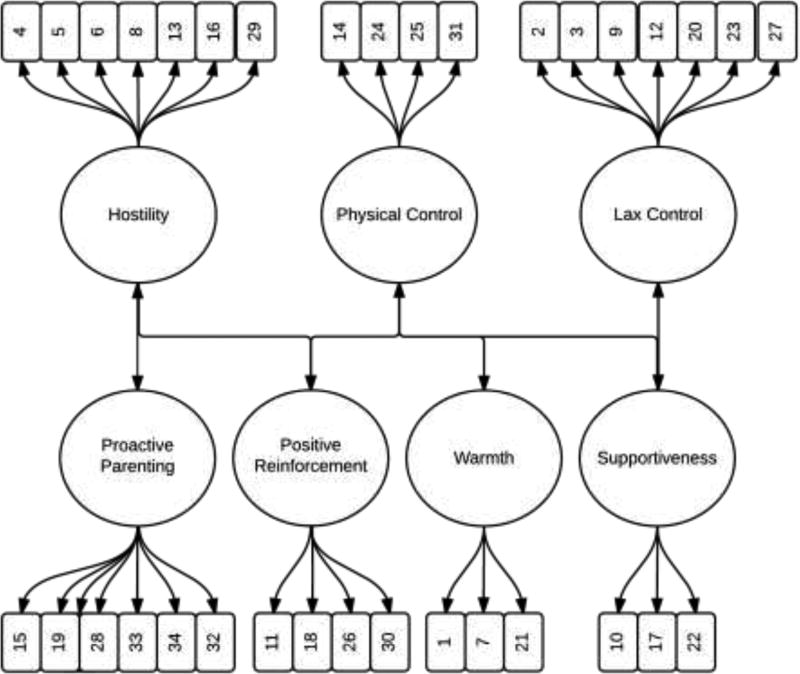

ESEM analyses were conducted using Mplus 7.1 software (Muthen & Muthen, 2012) and maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (MLR) to adequately account for non-normality. The use of the MLR estimator required the use of a scaled chi-square difference test (Satorra, 2000) for making key comparisons among nested models. First a CFA model (see Figure 2) was estimated followed by an ESEM model (similar to Figure 2 but allowing for all cross-loadings). Per recommendations by Marsh et al (2014), the ESEM model used target oblique rotation specifying target loading values near zero for items not within a given subscale. The following fit statistics were employed to evaluate model fit: Chi-square (χ2: p > .05 excellent), Comparative Fit Index (CFI; > .95 excellent), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; < .05 excellent) and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR; < .05 excellent) (Browne & Cudeck, 1993; Hu & Bentler, 1999). Full information maximum likelihood estimation techniques were used for inclusion of all available data.

Figure 2.

CFA factor structure with items as indicators.

Final factor structure

The CFA model depicted in Figure 2 demonstrated acceptable fit, χ2 (506, N = 564) = 1066, p < .01, RMSEA = .044, 95% CI .041 – .048, CFI = .92, SRMR = .06. Full CFA results are available in the online Supplemental Apendix. The ESEM model demonstrated excellent fit, χ2 (344, N = 564) = 523, p < .01, RMSEA = .03, 95% CI .025 – .036, CFI = .97, SRMR = .02. As expected, the improvement in fit from the CFA to ESEM model was significant, Δχ2 (164) = 524, p < .01 (see Table 1 for ESEM model).

Table 1.

Standardized factor loadings for the ESEM model.

| PP | PR | WM | SP | HS | PC | LC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 15: Reasons for requests | .59* | .12 | .03 | −.05 | −.04 | −.08* | .02 |

| Item 19: Warn before activity change | .58* | .14 | −.02 | −.06 | .05 | .01 | −.01 |

| Item 28: Expectations before activity | .61* | .17* | .02 | −.10 | .03 | .02 | .01 |

| Item 33: Clear choices | .50* | −.08 | .02 | .10 | −.17* | −.01 | .01 |

| Item 34: Clear consequences | .65* | −.05 | .03 | .05 | .07 | .08* | −.14* |

| Item 32: Explain discipline | .57* | .03 | .04 | .11 | −.04 | .02 | −.03 |

| Item 11: Praise chore completion | .13 | .40* | .09 | .14 | .02 | −.01 | .03 |

| Item 18: Praise listening | .07 | .67* | −.01 | .14 | −.01 | −.08* | −.01 |

| Item 26: Proud after task | .05 | .86* | .08 | −.12 | −.07 | .02 | .11* |

| Item 30: Praise for helping | .18* | .44* | .01 | .24* | .03 | .01 | −.05 |

| Item 1: Express affection | .01 | .03 | .80* | −.06 | −.01 | .03 | .01 |

| Item 7: Warm and intimate times | .07 | −.08 | .60* | −.11 | −.05 | .01 | .02 |

| Item 21: Hug and/or kiss | −.04 | .03 | .96* | −.02 | .07* | −.01 | −.03 |

| Item 10: Show respect | .06 | .04 | .06 | .52* | −.10* | −.14* | .09* |

| Item 17: Encourage communication | .06 | .23* | .05 | .51* | .05 | −.02 | −.12* |

| Item 22: Listen | −.01 | .03 | .03 | .80* | −.07 | .05 | .04 |

| Item 4: Argue | −.03 | −.04 | .01 | .07 | .68* | −.11* | −.02 |

| Item 5: Threats | −.05 | −.01 | −.02 | −.04 | .35* | .10* | .32* |

| Item 6: Punishment based on mood | .18* | −.19* | .02 | −.12 | .46* | −.01 | .27* |

| Item 8: Yell or shout | −.03 | .09 | .01 | .07 | .77* | .12* | −.13* |

| Item 13: Explode in anger | −.07 | .04 | .01 | −.06 | .72* | .02 | −.03 |

| Item 16: Lose temper | −.07 | .11 | −.04 | −.05 | .79* | .03 | −.08* |

| Item 29: Picky and on child’s back | .08 | −.15* | .02 | −.02 | .62* | −.06 | .12* |

| Item 14: Spank with hand | .01 | −.05 | .03 | .03 | −.05 | .90* | .01 |

| Item 24: Spank when angry | .01 | −.02 | −.01 | −.03 | .13* | .70* | .07 |

| Item 25: Physical punishment | .03 | .02 | .02 | .01 | .01 | .90* | −.06 |

| Item 31: Other ways haven’t worked | −.01 | .02 | .03 | −.02 | −.05 | .86* | .03 |

| Item 2: Gives in | −.07 | .07 | .04 | −.01 | −.07 | .02 | .70* |

| Item 3: Afraid to discipline | .04 | −.03 | −.05 | −.12* | −.11* | .02 | .63* |

| Item 9: Talked out of punishments | .09 | −.04 | −.06 | .11* | .20* | .02 | .68* |

| Item 12: End punishment early | .11 | −.05 | −.04 | .09 | .11* | −.01 | .59* |

| Item 20: Back down and give in | −.15* | .07 | .01 | .06 | .01 | −.04 | .73* |

| Item 23: Not worth the trouble | −.10 | −.02 | −.01 | −.12* | .16* | .04 | .50* |

| Item 27: Give in to commotion | −.10 | .08 | .04 | −.03 | −.02 | .03 | .72* |

Note: PP = Proactive Parenting; PR = Positive Reinforcement; WM = Warmth; SP = Supportiveness; HS = Hostility; PC = Physical Control; LC = Lax Control. Bold = primary subscale items;

p < .05. See MAPS appendix for full item content.

All four positive parenting subscales were significantly and positively correlated with each other (rs ranging from .36 to .59). Hostility was significantly and negatively correlated with all four positive parenting subscales (rs ranging from −. 13 to −.27) and positively correlated with Lax Control (r = .40, p < .05) and Physical Control (r = .36, p < .05). Lax Control was significantly and negatively correlated with all positive parenting subscales (rs ranging from . 16 to .25) except Warmth and had a small positive correlation with Physical Control (r = . 11, p < .05). Lastly, Physical Control was negatively correlated with Supportiveness (r = −.24, p < .05) but none of the other positive parenting subscales.

Measurement invariance across child developmental stages

A multiple-group ESEM was employed to examine and test whether measurement invariance across the three developmental stages was supported. It was hypothesized that the measurement of parenting would not be equivalent across the three developmental stages. Three different forms of measurement invariance were tested: configural (i.e., identical factor structure for each stage), metric (factor loadings are held equal across groups), and scalar (factor loadings and intercepts/thresholds are held equal across groups). Contrary to hypotheses, chi-square difference tests between the configural, metric, and scalar models were all nonsignificant (all ps > .20), supporting strong measurement invariance of parenting across the three development stages.

Broadband factor structure

In order to examine hierarchical factor structure and test if a broadband positive and negative parenting factor structure was supported, ESEM within CFA (EwC) was used. The EwC model with broadband positive and negative factors demonstrated excellent fit, χ2 (546, N = 564) = 547.5, p > . 10, RMSEA = .002, 95% CI .000 - .014, CFI = 1.0, SRMR = .038. Proactive Parenting (.75), Positive Reinforcement (.77), Warmth (.56), and Supportiveness (.69) all had significant factor loadings onto the Broadband Positive Parenting factor. Additionally, partial support emerged for a Broadband Negative Parenting factor with Hostility (.88), Lax Control (.39), and Physical Control (.46) all having significant factor loadings – albeit with Hostility being the primary narrowband factor.

Stage 4 – Internal and test-retest reliability

Internal consistency

Coefficient omega, a preferable index of internal consistency over alpha (see Dunn, Baguley, & Brunsden, 2014, for a review), was calculated for each of the seven subscales and Broadband Positive Parenting at baseline. Coefficient omega was calculated using the MBESS package (Kelley & Lai, 2012) in R and used bootstrapping to obtain 95% confidence intervals for items within each subscale (i.e., akin to CFA results). For comparison purposes, alpha coefficients were also calculated. Reliability was good to excellent for Proactive Parenting (Ω = .81 [.78 to .84], α = .80), Positive Reinforcement (Ω = .83 [.80 to .86], α = .83), Warmth (Ω = .84 [.81 to .86], α = .83), Hostility (Ω = .84 [.82 to .87], α = .85), Lax Control (Ω = .85 [.82 to .88], α = .85), and Physical Control (Ω = .91 [.89 to .93], α = .91) scores. Reliability was marginal for Supportiveness scores, Ω = .77 [.72 to .80], α = .77, but strong for Broadband Positive Parenting, Ω = .90 [.88 to .91], α = .90, and Broadband Negative Parenting, Ω = .88 [.85 to .90], α = .88, scores.

Test-retest reliability

The sample from stage 3 was reassessed two weeks after baseline (80.7% retention) to ascertain test-retest reliability. Longitudinal test-retest ESEM was utilized to examine correlations between narrowband factors across the baseline and two-week time points. Two sets of ESEM factors, one for baseline and one for the two-week follow-up, were delineated allowing for correlated uniqueness between the same items across time-points (e.g., item 22 at baseline with item 22 at the two-week follow-up). The test-retest ESEM demonstrated excellent fit, χ2 (1762, N = 564) = 2437.2, p < .01, RMSEA = .026, 95% CI .024 - .029, CFI = .96, SRMR = .025. Two-week test-retest reliability was strong for all subscale scores as indexed by high between time-point correlations for Proactive Parenting, r = .88, p < .01, Positive Reinforcement, r = .84, p < .01, Warmth, r = .90, p < .01, Supportiveness, r = .81, p < .01, Hostility, r = .91, p < .01, Lax Control, r = .91, p < .01, and Physical Control, r = .91, p < .01.

Stage 5 – Change over time and assessing validity

Overview

Latent curve modeling (LCM) was utilized, as implemented by Mplus, for stage 5 analyses. Specifically, a parallel process LCM (Preacher, Wichman, MacCallum, & Briggs, 2008) was used because it allows for both level (intercept) and change (slope) in one variable (parenting subscale) to be used to predict level and change in other variables (child psychosocial adjustment). Unconditional models for each parenting subscale and each child outcome were examined prior to testing parallel process models.

Unconditional parenting LCMs

See the online Supplemental Appendix for all final unconditional LCM models. The unconditional LCM with linear slope for Positive Reinforcement, Warmth, Hostility, and Lax Control demonstrated excellent fit. As fit with a linear slope was marginal for Proactive Parenting, Supportiveness, and Physical Control, free-loading LCMs were used instead such that the last time-point was freely estimated. In all cases the free-loading model provided superior fit when compared to linear slope models, all Δχ2 ps < .01. Across all parenting subscales the covariance of intercept and slope factors were significant and negative suggesting that parents who have lower scores at baseline tend to increase more rapidly across 12-months for each of the parenting subscales. The variances of intercept and slope factors for all parenting subscales significantly differed from zero, indicating potentially important individual variability in both starting-point and change over time.

Unconditional child behavior LCMs

The unconditional LCM with linear slope for internalizing problems demonstrated excellent fit. Fit for the externalizing problems model with a linear slope was excellent but the correlation between intercept and linear slope was greater than one, causing not positive definite errors; therefore, an intercept-only model was used. The intercept-only model resolved the not positive definite error and provided equivalent fit when compared to the linear slope model, Δχ2 (3) = 2.2, p > .10. The intercept-only externalizing LCM implies between-person variability in overall level of externalizing problems, but externalizing problems does not change with time. The covariance of intercept and slope factors for internalizing problems was not significant. The variance of intercept for internalizing and externalizing problems was significant, indicating potentially important individual variability in the starting point in these factors. The variance of slope for internalizing problems was not significant but the mean linear rate of change was positive and significant.

Parenting-child behavior LCMs

See Table 2 for fit statistics for all models and Table 3 for a summary of the results. Model fit across all models was excellent.

Table 2.

Model fit for parallel process LCMs.

| Internalizing Problems | Externalizing Problems | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| χ2 (df) | RSMEA [95% CI] | CFI | SRMR | χ2 (df) | RSMEA [95% CI] | CFI | SRMR | |

| Proactive Parenting | 51.4 (21) | .051 [.03 – .07] | .99 | .03 | 37.8 (26) | .028 [.00 – .05] | 1.0 | .03 |

| Positive Reinforcement | 45.0 (22) | .043 [.03 – .06] | .99 | .02 | 35.7 (27) | .024 [.00 – .04] | 1.0 | .02 |

| Warmth | 49.3 (22) | .047 [.03 – .07] | .99 | .03 | 42.9 (27) | .032 [.01 – .05] | .99 | .02 |

| Supportiveness | 30.5 (21) | .028 [.00 – .05] | 1.0 | .02 | 25.3 (26) | .00 [.00 – .03] | 1.0 | .02 |

| Hostility | 50.9 (22) | .048 [.03 – .07] | .99 | .03 | 60.6 (27) | .047 [.03 – .06] | .98 | .02 |

| Lax Control | 40.8 (22) | .039 [.02 – .06] | .99 | .03 | 39.8 (27) | .029 [.00 – .05] | .99 | .03 |

| Physical Control | 46.1 (21) | .046 [.03 – .06] | .99 | .02 | 4.3 (26) | .033 [.01 – .05] | .99 | .03 |

Table 3.

Parallel LCM results.

| Internalizing Problems Standardized Coefficient (Standard Error) |

Externalizing Problems Standardized Coefficient (Standard Error) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| Pint ↔ Yint | Pslp ↔ Yslp | Pint → Yslp | Yint → Pslp | Int ↔ Int | Slp ↔ Slp | Pint → Yslp | Yint → Pslp | |

| Proactive Parenting | −.17 (.05)** | −.09 (.12) | .09 (.13) | −.10 (.07) | −.14 (.05)** | -- | -- | −.09 (.06) |

| Positive Reinforcement | −.13 (.05)* | .05 (.17) | .02 (.12) | −.17 (.07)* | −.10 (.05)* | -- | -- | −.23 (.07)** |

| Warmth | −.25 (.05)** | −.17 (.13) | .10 (.12) | −.16 (.07)* | −.22 (.05)** | -- | -- | −.15 (.07)* |

| Supportiveness | −.14 (.05)** | .02 (.11) | .01 (.13) | −.11 (.07)† | −.33 (.05)** | -- | -- | −.01 (.06) |

| Hostility | .45 (.05)** | .40 (.16)* | .01 (.12) | −.08 (.06) | .57 (.03)** | -- | -- | −.03 (.06) |

| Lax Control | .28 (.06)** | .42 (.29) | −.16 (.12) | .03 (.11) | .26 (.06)** | -- | -- | .01 (.12) |

| Physical Control | .04 (.06) | .15 (.15) | .11 (.13) | .02 (.07) | .33 (.05)** | -- | -- | .01 (.07) |

Note: N = 546. Int = intercept; Slp = slope; Yslp = youth problem behavior slope; Pslp = parenting slope; ↔ = covariance; → = regression;

p ≤ . 10

p < .05

p < .01.

For child internalizing problems, correlations between the internalizing intercept and parenting subscale intercepts were all significant except for Physical Control. Thus, at baseline, higher levels of Proactive Parenting, Positive Reinforcement, Warmth, and Supportiveness and lower levels of Hostility and Lax Control were related to lower levels of child internalizing problems. Second, change in Hostility, but not other subscales, was significantly correlated with change in child internalizing problems: As Hostility increased linearly over time, child internalizing problems increased. Third, not surprisingly due to the non-significant variance in child internalizing problems slope, mean levels of parenting at baseline did not predict change in these problems. Lastly, lower levels at baseline of child internalizing problems predicted increases in Positive Reinforcement, Warmth, and Supportiveness over time.

For child externalizing problems, correlations between parenting subscale intercepts and the intercept of this problem behavior were significant for all subscales. Given that the externalizing LCM did not include a slope factor, significant correlations between intercepts can be interpreted as follows: Higher baseline levels of Proactive Parenting, Positive Reinforcement, Warmth, and Supportiveness and lower baseline levels of Hostility, Lax Control, and Physical Control were associated with lower mean levels of externalizing problems at all four assessment points. Lastly, lower mean levels of child externalizing problems predicted increases in three parenting subscales over time: Positive Reinforcement, Warmth, and Supportiveness.

Discussion

The primary aim of the current study was to create a new multidimensional measure of parenting practices, constituted by items from already established measures, that overcomes the issues common among previous measures in order to advance the measurement of parenting practices in clinical and research settings. The current study utilized 1,790 parents across five stages of analysis designed to (a) select optimal parenting items, (b) establish a factor structure consisting of positive and negative dimensions of parenting, (c) meaningfully consider child development stage, and (d) ensure strong psychometric properties (reliability and initial validity). Through this five stage empirical approach, the Multidimensional Assessment of Parenting Scale (MAPS) was developed, successfully achieving all aims. The Supplemental Appendix shows the final MAPS to be used in future research as well as scoring information and a version with original item numbers and final item numbers. Importantly, the average reading U.S. grade level equivalent of the final MAPS items was 6.6 (see the Supplemental Appendix for details).

Stage 1 of the MAPS development achieved the first aim through retaining items with meaningful variability and removing poorly performing items. Stages 2 and 3 of the MAPS development resulted in a factor structure that included both positive and negative dimensions of parenting practices that were appropriate for parents of children across the developmental span. The MAPS final factor structure included seven narrowband domains of parenting practices and two broadband domains. The Broadband Positive Parenting factor includes four narrowband subscales: Proactive Parenting which measures child-centered appropriate responding to anticipated difficulties; Positive Reinforcement which measures contingent responses to positive child behavior with praise, rewards, or displays of approval; Warmth which measures displays of affection; and Supportiveness which measures displayed interest in the child, encouragement of positive communication, and openness to a child’s ideas and opinions. The Broadband Negative Parenting factor included three narrowband subscales: Hostility which includes items representing intrusive parenting which is overcontrolling and parent-centered, harshness which includes coercive processes such as arguing, threats, and yelling, ineffective discipline, and irritability; Physical Control which includes items representing physical discipline both generally and specifically out of anger and frustration; and Lax Control which includes items representing permissiveness or the absence of control, easily coerced control in which the parent backs down from control attempts based on the child’s behavior, and inconsistency which is the failure to follow through with control or inconsistent applying consequences. The Lax Control subscale can be conceptualized as a continuum such that higher levels represent lax control and lower level represents firm control.

Stages 1 through 3 were all conducted separately by child developmental stage (i.e., young childhood, middle childhood, and adolescence) in order to meaningfully consider stage throughout the development of the MAPS. Contrary to hypotheses, full measurement invariance of the final factor structure of the MAPS was supported in ESEM analyses. Although unexpected, this outcome is in hindsight not as perplexing as it initially sounds as well as being advantageous for future research. First, ad hoc examination of the final items reveals wording that captures the specific underlying domain while also being sufficiently broadly worded to apply to children in differing developmental stages. For example, for item 4 (see the online Supplemental Appendix), “I argue with my child” can look very different depending on the age of the child but the simple wording of this item allows it to equally apply to a parent who has frequent arguments with her or his child regardless of that child’s developmental stage. This example is representative of a majority of items. Some items in particular were not expected to be viable across child developmental stages. One such example is “My child and I hug and/or kiss each other” (item 21). Yet, this item and others like it do not include the context in which the behavior is occurring (e.g., at home or in public); thus, parents of both young children and teenagers can endorse this item.

Measurement invariance analyses tested whether the underlying factor structure of parenting is the same for different child developmental stages; a test that has largely been ignored in parenting and clinical research. Without measurement invariance of items, comparisons of parenting domains across developmental stages are potentially invalid (Marsh et al., 2014). Therefore, the finding that the factor structure of the MAPS is supportive of measurement invariance across child developmental stages is advantageous for future research. For example, the MAPS can support efforts at developmental mapping of parenting across child development and meaningfully testing hypotheses of change and continuity in parenting practices as they relate to child outcomes over the course of child development. Additionally, for intervention research, the MAPS can be used to examine if specific parenting domains change as a function of intervention for programs with parents of young children through adolescence or intervention research can include long-term follow-ups and use the same measure of parenting as children move across stages. Indeed, although unexpected, measurement invariance of the MAPS factor structure across child developmental stages is a clear strength of the final measure.

The aim of Stage 4 of the MAPS development was to establish the reliability properties of the measure, which was a particular weakness of previous measures (Morsbach & Prinz, 2006). All but one of the narrowband subscales demonstrated strong internal reliability as evidenced by omega and alpha coefficients of .80 and above. This is particularly impressive given the relatively small number of items per subscale. The only potentially problematic subscale in regard to reliability was the Supportiveness subscale score, which was marginal at .77. It is important to note that with only three items, this is not surprising and still above the often considered minimally acceptable level of reliability (.70). The promising note is that internal consistency of the Broadband Positive Parenting scale was excellent (.90) and it is recommended that the Supportiveness subscale be predominantly used as part of the Broadband scale. Lastly, two-week test-retest reliability for all MAPS domains was strong with all longitudinal ESEM derived correlation coefficients above .80. In sum, internal consistency and test-retest reliability provide strong support for the reliability of the MAPS subscale scores.

Stage 5 of the MAPS development provided initial evidence for the validity of interpretations of the MAPS subscale scores. The intercepts of the MAPS subscales and child problem behaviors were significantly related (except for Physical Control and child internalizing problems). The direction of effects was consistent with a large body of research, using both questionnaires and observations, linking domains of warmth, hostility, and behavioral control to child problem behaviors (see Cummings et al., 2000; Granic & Patterson, 2006; Hoeve et al., 2009; Rapee, 2012, for reviews).

In regard to longitudinal analyses, neither child internalizing nor externalizing problems evidenced meaningful variability in change over the 12 months, substantially limiting, or in the case of externalizing problems precluding, examination of MAPS subscales as predictors of change in child problem behaviors. However, unconditional LCMs of each MAPS subscale showed meaningful variance in both initial mean levels and change over the course of 12 months, allowing tests of child behavior predicting change in parenting. Results from these analyses found that child problem behaviors (internalizing and externalizing) predicted changes in domains of warmth and control of the MAPS such that higher initial levels of these child problem behaviors predicted decreases in Warmth and Positive Reinforcement over time. Although not as well developed as the literature on parent-to-child effects, these findings of child-to-parent effects are consistent with theory (e.g., Patterson, 1982) and empirical evidence (e.g., Belsky & Park, 2000), providing further support for the initial validity of the MAPS.

Initial support for validity of interpretations of the MAPS subscale scores is promising but only the beginning. It is important to note that though tests of validity were limited in the current study, the appeal of using items from already well-established parent scales was in part because the validity of the interpretations of these items was already supported by hundreds of empirical studies including substantial support for content, convergent, and divergent validity (e.g., Locke & Prinz, 2002). Nevertheless, future research will aim to continue to support the validity of the interpretations of MAPS subscale scores by using multiple-informants (i.e., coparent report), developing and using an adolescent report form, and utilizing different methods (i.e., observations) for assessing both parenting and child problem behavior. In addition, examining child behavior among at-risk and clinical populations may result in more meaningful variance in change of problem behaviors change over time. Finally, MAPS subscale change overtime as a function of intervention can and will occur.

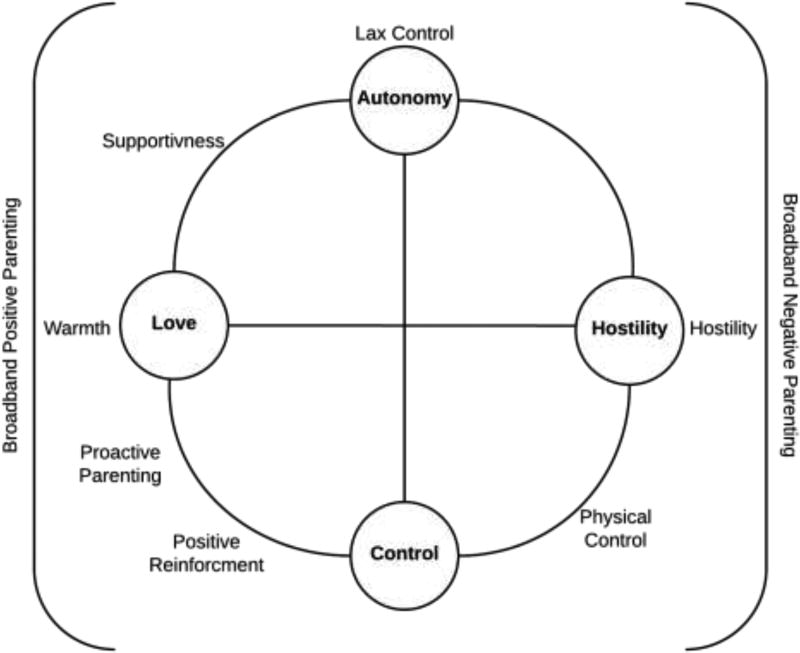

Although the stages of the current study embody an empirical approach to scale development, it also has important theoretical considerations. Many theoretical models include parenting practices as key components hypothesized to either promote or inhibit healthy child psychosocial development (e.g., attachment theory – Bowlby, 1969; ecological systems theory – Bronfenbrenner, 1979; social learning theories – Patterson, 1982) but few have been dedicated solely to parenting dimensionality (for a review, see Holden, 1997). Schaefer’s (1959) circumplex model of parenting is one of the only theoretical conceptualizations that focuses solely on parenting domains without a major emphasis on child outcome. The MAPS narrowband factor structure is supportive of Schaefer’s circumplex model with each of its subscales depicted on the outside of this model in Figure 3. The Warmth and Hostility narrowband MAPS scales are on the circumplex model’s love (warmth) versus hostility axis and Lax Control is on the autonomy versus control axis. The Proactive Parenting and Positive Reinforcement narrowband scales each involve higher levels of both warmth and control as they represent positive behavioral control strategies. The Supportiveness narrowband subscale consists of a combination of warmth and autonomy whereas the Physical Control narrowband subscale consists of both over-controlling and hostile parenting behavior.

Figure 3.

Schaefer’s circumplex model of parenting with MAPS subscales

The MAPS factor structure also differs and advances the original conceptualizations by Schaefer is in two ways. First, the Broadband Positive and Negative Parenting scales are divergent from Schaefer’s theoretical conceptualization but was supported by hierarchical factor analyses. Depicted in Figure 3 on the outside of the model, higher scores on the Broadband Positive Parenting scale would represent high levels of warmth and supportiveness, as well as positive control that is neither over- nor under-controlling. The Broadband Positive Parenting scale is in a way akin to Baumrind’s (1989) authoritative control in that it includes domains of positive and child-centered control (Positive Reinforcement and Proactive Parenting) and domains of warmth (Warmth and Supportiveness). Also depicted in Figure 3 on the outside of the model, higher scores on the Broadband Negative Parenting scale would represent high levels of hostility as well as both over- (Physical Control) and under-control (Lax Control).

Second, two narrowband domains were not represented in the final factor structure that were part of Schaefer’s original model: neglect and psychological control. First, the absence of a neglect narrowband subscale resulted in a final factor structure that does not include a domain high on autonomy and hostility. Second, psychological control (e.g., guilt induction) is considered by many as a key parenting domain (e.g., Barber, 1997) and its absence in the MAPS results in only a physical form of the combination of over-control and hostility. One explanation for the loss of neglect and psychological control items is the limited variability in responding. In essence, parents may be less aware of or inclined to report neglecting behavior or the use of psychological control strategies. Therefore, it may be that these narrowband domains are best assessed by child report, especially given established child-report measures of these domains (e.g., Schaefer, 1965). Future research aimed at improving the MAPS will explore these hypotheses as well as ways to improve parent-reported items assessing these domains.

Although not in Schaefer’s original model, the final factor structure of the MAPS is notably missing a monitoring narrowband subscale. Substantial research and theory has pointed to the important of this construct (Dishion & McMahon, 1998). However, Stattin and Kerr’s (Stattin & Kerr, 2000) seminal work challenged our understanding of parental monitoring by shifting attention to the child as information managers (e.g., deciding when to disclose information). Their work has encouraged researchers to think about the interactional and relational processes that keep, or fail to keep, parents informed rather than focusing solely on this parenting behavior. Given that most of the monitoring items were eliminated at early stages in the development (i.e., stage 1), this further supports the view that measuring child’s disclosure, preferably child-reported, be given strong consideration in addition to traditional parent-direct efforts to monitor and gain knowledge of child behavior.

In addition to the limitations discussed previously, there are two primary limitations of the current study to be addressed in future research on the MAPS. First, the current sample was primarily White (78%), educated, and middle or upper income, leaving open to question the generalizability of the MAPS to more diverse families. A key next step will be to examine the factor structure and psychometric properties with diverse samples. Second, all variables were from a single reporter. This potentially introduces the issue of shared method variance and limits support for validity without cross-informant and method associations. This limitation is partially dampened because all the items were taken from measures with established multi-modal criterion validity (e.g., child report, teacher report, observations). Regardless, another next step in the development of the MAPS will be to validate coparent and adolescent report versions as well as establishing associations between MAPS subscales and both observed parenting practices and child outcomes assessed by multiple informants (e.g., adolescents, teachers).

The current study also had strengths not discussed thus far. First, the MAPS was developed through five rigorous stages using separate samples for each set of factor analyses as advocated by methodologists (e.g., Brown, 2006; Matsunaga, 2010). Second, the current study used advanced statistical methods for determining final factor structure (e.g., exploratory structural equation modeling), establishing reliability (omega coefficient with bootstrapped CI; longitudinal ESEM), and providing initial support for validity (e.g., latent growth curve modeling). Third, all three samples used for the development of the MAPS were constituted by at least 40% father participants, a group which is underrepresented in clinical child and adolescent research (Phares et al., 2005). Previous parenting measures were often exclusively developed with mothers, which makes the current work with the MAPS a particular strength.

In conclusion, the present study developed the MAPS using a multi-stage empirically-based approach. The factor structure of the MAPS was invariant across child developmental stages, included both positive and negative domains, and evidenced strong psychometric properties. Although the current study embodied an empirical approach, the final factor structure is congruent with Schaefer’s circumplex model of parenting, in a way returning to the field’s original roots, and provides a basis for new research and applications. Poor psychometric properties and inconsistent use of multiple conceptualizations and operationalizations has created ambiguity in parenting research. The development of the MAPS represents a first step toward creating a system of evidenced-based parenting assessment that overcomes issues of previous measures. Available in the text and the supplemental appendices are the full MAPS, information on scoring, norms by developmental stage, and a beta excel scoring program for clinical use that provides T-scores, percentiles, validity of reporting, and clinical interpretation (i.e., Normative, Borderline, and Clinical). The use of these T-scores, percentiles, validity of reporting, and clinical interpretations are considered exploratory at this time and future research will be needed to support their use in research and clinical practice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was funded by the Child and Adolescent Psychology Training and Research, Inc (CAPTR). The first author is supported NICHD grant F31HD082858 and the second author is supported by NIMH grant R01MH100377. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent he official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Compliance with Ethical Standards:

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Author Contributions: JP: designed and executed the study, conducted data analyses, and had primary responsibility with writing the manuscript. RF: collaborated and assistant with all aspects of the study as well as with writing the manuscript.

References

- Achenbach TM. Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA): Development, findings, theory, and applications. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach T, McConaughy S, Ivanova MY, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA Brief Problem Monitor (BPM) Burlington, VT: University of Vermont; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla L. ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. Burlington, VT: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold DS, O’Leary SG, Wolff LS, Acker MM. The Parenting Scale: A measure of dysfunctional parenting in discipline situations. Psychological Assessment. 1993;5:137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK. Introduction: Adolescent socialization in context—the role of connection, regulation, and autonomy in the family. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1997;12(1):5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Rearing competent children. In: Damon W, editor. Child development today and tomorrow. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1989. pp. 349–378. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Park S. Exploring reciprocal parent and child effects in the case of child inhibition in US and korean samples. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2000;24(3):338–347. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss, Vol. I: Attachment. New York: Basic Books; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester M, Kwang T, Gosling S. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2011;6:3–5. doi: 10.1177/1745691610393980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Casler K, Bickel L, Hackett E. Separate but equal? A comparison of participants and data gathered via Amazon’s MTurk, social media, and face-to-face behavioral testing. Computers in Human Behavior. 2013;29(6):2156–2160. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler J, Mueller P, Paolacci G. Nonnaïveté among Amazon Mechanical Turk workers: Consequences and solutions for behavioral researchers. Behavior Research Methods. 2014;46(1):112–130. doi: 10.3758/s13428-013-0365-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Barlow DH. The development of anxiety: the role of control in the early environment. Psychological Bulletin. 1998;124(1):3–21. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.124.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Reise S, Weisz JR, Grubbs K, Becker KD, Krull JL. Evaluation of the brief problem checklist: Child and caregiver interviews to measure clinical progress. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78(4):526–536. doi: 10.1037/a0019602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT, Campbell SB. Developmental psychopathology and family process. New York: Guilford; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Darling N, Steinberg L. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113(3):487. [Google Scholar]

- DeVellis RF. Scale development: Theory and applications. Los Angeles, CA: Sage; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, McMahon RJ. Parental monitoring and the prevention of child and adolescent problem behavior: A conceptual and empirical formulation. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 1998;1(1):61–75. doi: 10.1023/a:1021800432380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn TJ, Baguley T, Brunsden V. From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. British Journal of Psychology. 2014;105:399–412. doi: 10.1111/bjop.12046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ. The Alabama parenting questionnaire. Unpublished rating scale 1991 [Google Scholar]

- Gardner F. Methodological issues in the direct observation of parent-child interaction: Do observational findings reflect the natural behavior of participants? Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2000;3(3):185–198. doi: 10.1023/a:1009503409699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granic I, Patterson GR. Toward a comprehensive model of antisocial development: A dynamic systems approach. Psychological Review. 2006;113(1):101. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.113.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henson RK, Roberts JK. Use of exploratory factor analysis in published research: Common errors and some comment on improved practice. Educational and Psychological Measure1ment. 2006;66:393–416. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeve M, Dubas JS, Eichelsheim VI, van dL, Smeenk W, Gerris JRM. The relationship between parenting and delinquency: A meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37(6):749–775. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9310-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden GW. Parents and the dynamics of child rearing. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hurley KD, Huscroft-D’Angelo J, Trout A, Griffith A, Epstein M. Assessing parenting skills and attitudes: A review of the psychometrics of parenting measures. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2014;23(5):812–823. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Research design in clinical psychology. Vol. 3. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley K, Lai K. MBESS: MBESS. R package version 3.3.2 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Locke LM, Prinz RJ. Measurement of parental discipline and nurturance. Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22:895–930. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(02)00133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy MC, Weis R, O’Hare E, Rubin EC. Development and initial validation of the Parent Behavior Inventory. Psychological Assessment. 1999;11(4):534. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Morin AJS, Parker PD, Kaur G. Exploratory structural equation modeling: An integration of the best features of exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2014;10:85–110. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga M. How to factor-analyze your data right: Do’s, don’ts, and how-to’s. International Journal of Psychological Research. 2010;3(1):97–110. [Google Scholar]

- McEachern AD, Dishion TJ, Weaver CM, Shaw DS, Wilson MN, Gardner F. Parenting Young Children (PARYC): Validation of a self-report parenting measure. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2012;21:498–511. doi: 10.1007/s10826-011-9503-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee LG, Jones DJ, Forehand R, Cueller J. Assessment of parenting style, parenting relationships, and other parenting variables. In: Saklofski D, editor. Handbook of psychological assessment of children and adolescents. New York: Oxford University Press; 2013. pp. 788–821. [Google Scholar]

- Morsbach SK, Prinz RJ. Understanding and improving the validity of self-report of parenting. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2006;9(1):1–21. doi: 10.1007/s10567-006-0001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus user’s guide (en7) Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally JC. Psychometric theory. 2. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric theory. 3. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TG. The ‘effects’ of parenting reconsidered: Findings, challenges, and applications. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;43(5):555–572. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent J, Forehand R, Pomerantz H, Peisch V, Seehuus M. Father participation in child psychopathology research. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. doi: 10.1007/s10802-016-0254-5. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent J, Forehand R, Watson KH, Dunbar JP, Seehuus M, Compas BE. Parent and adolescent report of parenting when a parent has a history of depression: Associations with observations of parenting. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2014;42:173–183. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9777-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil VH, Singh SN, Mishra S, Donavan T. Parallel analysis engine to aid determining number of factors to retain [Computer software] 2007 Available from http://smishra.faculty.ku.edu/parallelengine.htm.

- Patterson GR. Coercive family process. Eugene, OR: Castalia; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson RA. A meta-analysis of Cronbach’s coefficient alpha. Journal of Consumer Research. 1994;21(2):381–391. [Google Scholar]

- Perepletchikova F, Kazdin AE. Assessment of parenting practices related to conduct problems: Development and validation of the Management of Children’s Behavior Scale. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2004;13:385–403. [Google Scholar]

- Phares V, Fields S, Kamboukos D, Lopez E. Still looking for poppa. American Psychologist. 2005;60(7):735–736. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.7.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Wichman AL, MacCallum RC, Briggs NE. Latent growth curve modeling. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ramey SL. The science and art of parenting. In: Borkowski JG, Ramey SL, Bristol-Power M, editors. Parenting and the child’s world: Influences on academic, intellectual, and social-emotional development. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; Mahwah, NJ: 2012. pp. 47–74. [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM. Family factors in the development and management of anxiety disorders. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2012;15(1):69–80. doi: 10.1007/s10567-011-0106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson CC, Mandleco B, Olsen SF, Hart CH. Authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting practices: Development of a new measure. Psychological Reports. 1995;77:819–830. [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A. Scaled and adjusted restricted tests in multi-sample analysis of moment structures. Springer; US: 2000. pp. 233–247. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer ES. A circumplex model for maternal behavior. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 1959;59:226–235. doi: 10.1037/h0041114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer ES. Children’s Reports of Parental Behavior: An inventory. Child Development. 1965:413–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton KK, Frick PJ, Wootton J. Assessment of parenting practices in families of elementary school-age children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1996;25(3):317–329. [Google Scholar]

- Stanger S, Pomerantz H, Parent J. Reliability of parent-reported parenting questionnaires: A review; Paper submitted to be presented at the 50th annual meeting of the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies; New York, NY. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stattin H, Kerr M. Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Development. 2000;71:1072–1085. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taber SM. The veridicality of children’s reports of parenting: A review of factors contributing to parent-child discrepancies. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:999–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.