Abstract

Considerable research efforts have been dedicated to understanding ovarian and breast cancer mechanisms, but there has been little progress translating the research into effective clinical applications. Hence, personalized/precision medicine has emerged because of its potential to improve the accuracy of tumor targeting and minimize toxicity to normal tissue. Targeted therapy in both breast and ovarian cancer has focused on antibodies, antibody drug conjugates (ADCs), and very recently the introduction of human antibody fusion proteins. Small molecule inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are used in conjunction with chemotherapeutic drugs as a form of treatment but problems arise from a board expression of the target antigen in healthy tissues. Also, insufficient tumor penetration due to tight binding affinity and macromolecular size of mAbs compromise the efficacy of these ADCs. A more targeted approach is thus needed, and ADCs were designed to meet this need. However, in ADCs the method of conjugation of drug to antibody is >1, altering the structure of the drug which leads to off-target effects. Random conjugation also causes the drug to affect the pharmokinetics and biodistribution of the antibody and may cause nonspecific binding and internalization. Recombinant therapeutic proteins achieve controlled conjugation reactions and combine cytotoxicity and targeting in one molecule. They can also be engineered to extend half-life, stability and mechanism of action, and offer novel delivery routes. SNAP-tag fusion proteins are an example of a theranostic recombinant protein as they provide a unique antibody format to conjugate a variety of benzyl guanine modified labels, e.g. fluorophores and photosensitizers in a 1:1 stoichiometry. On the one hand, SNAP tag fusions can be used to optically image tumors when conjugated to a fluorophore, and on the other hand the recombinant proteins can induce necrosis/apoptosis in the tumor when conjugated to a photosensitizer upon exposure to a changeable wavelength of light. The dual nature of SNAP-tag fusions as both a diagnostic and therapeutic tool reinforces its significant role in cancer treatment in an era of precision medicine.

Keywords: SNAP-tag, Photosensitizers, Single chain variable fragment, scFv, Photoimmunotherapy, Organic fluorophores, Near infra-red

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer type among women, and ovarian cancer is the sixth most commonly diagnosed cancer in the world [1,2]. Both types of cancers are strongly associated with mutations in the tumor suppressor genes BCRA1 and BCRA2 [3] and the HER2/neu proto-oncogene [1,4] and are linked to mutations in genes associated with other inherited autosomal disorders such as Li-Fraumeni (TP53), Peutz-Jeghers (STK11/LKB1) and Cowden syndrome (PTEN) [5]. Breast cancer can be sub-classified according to the expression of estrogen (ER) and progesterone (PR) receptor as well as the epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) [6]. The molecular basis of breast cancer is well understood, and five molecular subtypes are recognized: luminal A and B, HER2+, basal-like, and normal breast-like [7]. The most aggressive form of breast cancer that does not express HER2, ER, or PR is termed triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) [8]. Ovarian cancer comprises of epithelial ovarian tumors which are the most common type, ovarian germ cell tumors, and ovarian stromal tumors [9,10,11]. Recently, the cancer-testis antigen NY-ESO-1 was discovered to be one of the few tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) that have restricted expression in normal tissue but was aberrantly expressed in epithelial ovarian cancers [12]. More than 90% of tumor samples expressed very high levels of CA125, FOLR1, EPCAM, and MUC-1 on both primary and established ovarian cancer cell lines [13]. By screening for these TAAs in cancerous cell lines or tissues and targeting them with SNAP fusions, the appropriate treatment modality can be employed. This article will provide a review on SNAP-tag applications in photoimmunotheranostics and optical imaging which are two treatment modalities of cancer.

Small Molecule Inhibitors and Monoclonal Antibodies in Breast and Ovarian Cancer

Examples of chemotherapeutic drugs available for treatment of breast cancer include cisplatin, doxorubicin, paclitaxel, and topoisomerase inhibitors [14]. Most breast cancers are resistant to these drugs, and such that the past two decades has seen the development of several monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and small-molecule inhibitors. Trastuzumab was the first mAb targeted against the extracellular domain of HER2, and it was shown to block intracellular signaling both in vitro and in vivo [14,15]. To enable trastuzumab to cross the blood-brain barrier, the antibody was combined with small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) [16]. Dual inhibitors for breast cancer include lapatinib, cetuximab, pertuzumab, canertinib, and neratinib [16,17]. Bevacizumab was another mAb directed against the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) which regulates angiogenesis and tumor survival [18]. Immune checkpoint inhibitors have also been currently evaluated for the treatment of TNBC. These include programmed death 1 (PD-1), programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1), and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) inhibitors [19]. A new, targeted therapy for breast and ovarian cancer is the PARP (poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase) inhibitor. Olaparib has been recently approved for ovarian cancer while niraparib, talazoparib, and rucaparib are being studied for various indications, including BRCA-mutated breast cancer [20,21,22]. However, mAbs have a relatively limited distribution, owing to their size, charge, and tight binding affinity. They exhibit non-specific binding owing to the constant region (Fc) of the mAb [23]. Moreover, the tight binding affinities of mAbs can further decrease the penetration of tumors [24,25]. Whereas one might presume that tighter binding is always better, several studies have shown that very high affinities can be suboptimal for therapeutic antibodies that target solid tumors [26,27]. A major determinant of speed of diffusion through tumors is molecular size. The rate of diffusion is approximately inversely proportional to the cube root of molecular weight [24,28]. Consequently, large macromolecules such as mAbs diffuse poorly explaining why larger tumor masses may be more difficult to treat by mAb therapy [24]. To overcome these challenges, targeted therapeutic agents in the form of antibody drug conjugates (ADCs) and fusion proteins have emerged.

Antibody-Drug Conjugates and Fusion Proteins in Breast and Ovarian Cancer

The main difference between ADCs and fusion proteins is attributed to the fact how they are generated. In ADCs, non-cleavable linkers or chemically labile linkers, including acid-cleavable linkers and reducible linkers, help conjugate antibody to drug [29,30,31]. Due to the chemical method of conjugation, most of these ADCs exist as heterogeneous mixtures, which can result in a narrow therapeutic window and have major pharmacokinetic implications [32]. Fusion proteins are made from a fusion gene which is created by joining parts of two different genes together; as a result there is no chemical conjugation necessary, and the constructs are homogeneous [33]. Both these therapeutic agents harness the specific nature of the mAb as an effective means of targeting the diseased cell. In ADCs, the goal is for the antibody to bind to the antigen on the cancer cell, become internalized, and then release the toxic payload to the cancer cell. Linkers are designed to break inside the cancer cells when exposed to a specific pH or a proteasome [34,35]. In fusion proteins, the goal is to guide the ligand specifically to tumor sites using the mAb linked to a protein moiety [29]. The variable regions (Fv) of antibodies or single-chain variable fragments (scFvs) are generally genetically fused to the protein moiety. scFvs are composed of variable heavy-chain (VH) and variable light-chain (VL) domains connected via a glycine, serine, or threonine linker to either the N-terminus of the VH on the C-terminus of the VL [36,37]. Numerous research groups have constructed recombinant antibody-cytokine fusion proteins composed of the ligands IL-2, IL-12, IL-21, TNF-α, and IFN-α, IFN-β, and IFN-γ which have shown anti-tumor activity [29,38,39,40,41,42]. Aflibercept (VEGF-Trap) is a fusion protein which combines ligand-binding elements taken from the extracellular components of the VEGF receptor 1 (VEGFR-1) and VEGFR-2 fused to the Fc portion of IgG [43,44]. A recent study revealed a greater efficacy for aflibercept than nesvacumab (an anti-Ang2 antibody) in neoadjuvant/adjuvant chemotherapy for TNBC [45].

The TRAIL-based fusion protein Meso-T3 was found to selectively accumulate on MUC16-expressing cancer targets and increase cytotoxic activity both in vitro and in vivo [46]. Compared to non-targeted TR3, Meso-TR3 displayed a much reduced killing potency on cells that lacked MUC16 [47]. The human HIV-1 TAT interactive protein 2 (HTATIP2/TIP30) is an evolutionarily conserved gene that is found to be associated with some gynecological cancers [46]. To improve targeting of the TAT protein, TAT-OSBP1-1-MKK6(E) was designed. This novel fusion protein was composed of three functional domains i) the protein transduction domain of TAT, ii) the human ovarian cancer HO8910 cell-specific binding peptide (OSBP-1) and iii) the potential anti-tumor effector domain of MKK6(E) [48]. TAT-OSBP1-1-MKK6(E) selectively targeted HO8910 cells in vitro and in vivo, leading to growth inhibition and apoptosis of tumor cells and presents a potential approach for ovarian cancer target therapy [48].

At least 2 ADCs for breast cancer are in advanced stages of development: sacituzumab govitecan and glembatumumab vedotin. Sacituzumab govitecan is a conjugate of the humanized anti-Trop-2 monoclonal antibody linked with SN-38, the active metabolite of the chemotherapeutic agent irinotecan [49,50]. SN-38 is too toxic to administer directly to patients, but linkage to an antibody allows the drug to specifically target cells containing Trop-2 [49,50]. The fully human IgG2 monoclonal antibody glembatumumab is linked to the microtubule inhibitor called monomethyl auristatin E and targets cancer cells expressing the transmembrane glycoprotein NMB. When patients with metastatic breast cancer were randomly assigned to glembatumumab vedotin, survival rates for metastatic breast cancer patients were significantly better with glembatumumab vedotin treatment than with standard treatment [51]. One ADC that has already received FDA approval is ado-trastuzumab-emtansine (T-DM1; Kadcyla®) which consists of the monoclonal antibody trastuzumab linked to the cytotoxic agent emtansin [52]. The phase III TH3RESA study revealed that physicians' choice of this ADC improved overall survival in patients with previously treated HER2+ metastatic breast cancer [52].

In platinum-resistant epithelial ovarian cancer, the ADC called mirvetuximab soravtansine (IMGN853) is being investigated and consists of a monoclonal antibody that binds to the folate receptor-alpha and is linked to a tubulin-disrupting maytansinoid DM4 chemotherapeutic agent [53]. TIM-1 expression is also upregulated in ovarian carcinomas. An ADC was produced with the anti-TIM-1 antibody covalently linked to monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE) and designated CDX-014 [54]. Other ADCs include PF-06647020 which consists of a humanized monoclonal antibody against the PTK7 antigen linked to the microtubule inhibitor auristatin. DMOT4039A, a humanized anti-mesothelin mAb conjugated to the antimitotic agent MMAE, was found to have a tolerable safety profile and antitumor activity in both pancreatic and ovarian cancer [55,56]. In 2016, a potent ADC called XMT-1536 was discovered. It consists of XMT-1535, a novel humanized anti-NaPi2b antibody conjugated to 15 MMAE molecules. In an ovarian cancer xenograft model, a single dose (5 mg/kg) of XMT-1536 induced complete tumor regression [57].

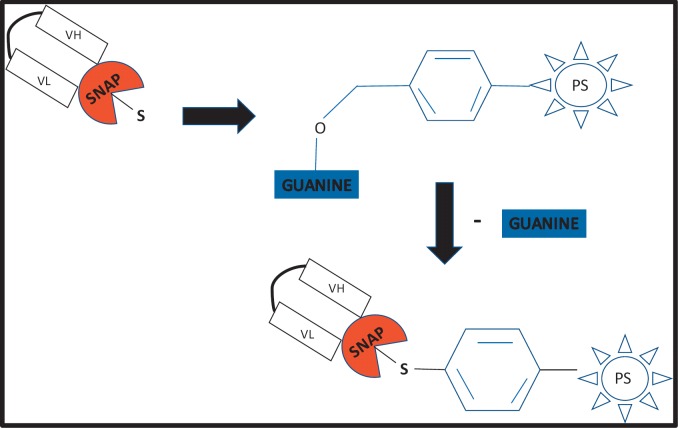

Despite significant advances in the field of ADCs, lack of specificity to the target antigen still remains a problem due to the method of drug to antibody conjugation. A drug can bind to multiple side chains on the antibody such that not only does the configuration of each conjugate differ, but so does the number of drug molecules attached to each [58]. As a result, the pharmacokinetic properties and efficacy of each ADC differs [59,60]. Despite the more controlled conjugation strategy afforded by recombinant fusion proteins, the intrinsic challenges that need to be overcome include immunogenicity that may occur due to the formation of novel epitopes at the junction between the fusion partners even if fully human proteins are connected [61]. SNAP-tag, when genetically fused to scFvs, creates a single conjugation site on the antibody fragment for the site-specific binding of variety of molecules. The SNAP-tag was pioneered by Kai Johnsson, and is derived from the human DNA repair enzyme O(6)-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase [62,63]. It reacts with para-substituted O6-benzylguanine (BG) derivatives by transferring the substituted benzyl group to its active site through a nucleophilic substitution reaction while releasing free guanine [64]. Figure 1 shows a photosensitizer conjugated to SNAP.

Fig. 1.

A schematic illustrating scFv-SNAP fusion protein conjugated to a BG modified photosensitizer through a nucleophilic substitution reaction and loss of free guanine.

This achieves efficient covalent conjugation to any BG-modified substrate under physiological conditions with a 1:1 stoichiometry, generating a homogeneous immunotherapeutic agent [64,65]. A SNAP-tag fusion protein is composed of the SNAP protein co-expressed with a tumor-specific antibody fragment. The expressed fusion protein is highly selective, site-specific, and versatile due to its high affinity for an array of BG substrates, e.g. toxins, fluorophores or photosensitizers [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66]. The conjugation of photosensitizers to SNAP-tag has made it an indispensable tool in photoimmunotherapy.

Photoimmunotherapy

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) has long been the gold standard of treatment for cancer and uses a drug called a photosensitizer followed by local illumination with visible light of specific wavelength(s) to induce apoptosis or necrosis in a tumor [67]. One of the greatest challenges in PDT is the lack of specificity. To overcome this challenge, photoimmunoconjugates have been designed that deliver the photosensitizer directly to the tumor site [68]. These conjugates consist of photosensitizers linked to tumor-specific mAbs or scFvs in an approach known as photoimmunotherapy (PIT) [68]. This treatment modality is enhanced by imaging in the near infrared (NIR) spectral region. Owing to reduced photon scattering, light absorption and auto-fluorescence as well as increased light penetration into tissue, NIR-PIT is a newly developed cell-selective cancer therapy [69]. Recently, IRDye®700DX N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (IR700) has shown to be a promising photosensitizer because of its high purity and photostability. The dye has a strong absorption peak close to 700 nm allowing light to penetrate deep into the tissue [70,71]. Moreover, IR700 does not develop off-target effects since they cannot be taken up by cells and cannot exert cytotoxicity even after illumination [72,73].

To date, a range of research studies have investigated the use of IR700 in PIT. The antibody fragment (scFv-425) that binds to EGFR was used as a model to investigate the use of SNAP-tag fusions as an improved conjugation strategy targeting skin, breast, pancreatic and ovarian cancer cells. The scFv-425-SNAP-fusion protein was conjugated to a range of BG-modified probes: a microtubule inhibitor auristatin F (AURIF) [74], a chlorin e6 photosensitizer in PDT [75], and the IR700 fluorophore in PIT [76,77]. All these probes were specifically targeted to the tumor and induced cytotoxicity. For example, in the case of cancerous ovarian cells, the SNAP fusion protein was able to eliminate EGFR+ cells with IC50 values of 45–66 nmol/l and 40–90 nmol/l [77]. In the case of breast cancer cells, the recombinant fusion proteins were stable in human serum, were internalized rapidly, and demonstrated potent inhibitory and pro-apoptotic effects in vitro at 3–21 nmol/l [74].

In another study, mAbs targeting EGFR were conjugated to IR700 and irradiated with NIR light, and in vivo tumor shrinkage was observed [73]. The choice of the mAb in photosensitizer conjugates may also influence the effectiveness of PIT. IR700 was conjugated to either cetuximab (cet-IR700) or panitumumab (pan-IR700), and their efficacies were evaluated in EGFR spheroids [78]. Although cet-IR700 and pan-IR700 showed identical in vitro characteristics, pan-IR700 showed better therapeutic tumor responses than cet-IR700 in in vivo mice models due to the prolonged retention of the conjugate in circulation. This also suggests that retention in the circulation is advantageous for tumor responses to PIT [78]. Recently, a promising ADC for the treatment of mesothelin-expressing tumors was discovered. It is composed of a humanized mesothelin antibody, known as hYP218, conjugated to IR700 [79]. The hYP218-IR700 showed specific binding to mesothelin-expressing cells, and cell-specific killing was observed in vitro [79]. After irradiation with NIR light, the hYP218-IR700 demonstrated high tumor accumulation-to-background ratio and significantly inhibited tumor growth and prolonged survival compared to the control groups [79]. The first step and most common form of treatment for breast and ovarian cancer is surgery, but the heterogeneous nature of the tumors result in poor tissue demarcation and destruction of normal cells. These challenges in surgery have been improved by NIR fluorescence image-guided surgery which has the potential to improve patient outcome and increase the completeness of surgery by decreasing the morbidity associated with damage to normal structures [80].

Optical Imaging in Guided Surgery

Types of breast cancer surgery include lumpectomy (removal of only the tumor) and mastectomy (removal of all the breast tissue) [81]. In advanced ovarian cancer, cytoreductive surgery is the accepted form of management even though the 5-year survival rate remains at about 40% [82]. The goal of cytoreductive surgery or debulking is to remove all visible tumors. This surgery is limited considering side effects generated by multivisceral resections, i.e. of the colon, spleen and/or the gallbladder as well as of parts of the stomach, liver, and/or pancreas, and some patients die within 30 days of surgery [83,84]. Thus, both breast and ovarian cancer surgery is harboring a good chance not to adequately discriminate healthy from cancerous tissue leading to irradical resections of the tumor. In view of this, imaging modalities, e.g. magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), CT scanning and ultrasound techniques, have played a significant role in the field of surgical image guidance, especially during endoscopy [85,86].

Improvements in preoperative imaging techniques have made a meaningful impact on cancer patient care [80]. Specialized intraoperative imaging systems for open surgery [87,88,89], laparoscopy [90,91], and robotic surgery [92,93] have emerged. Using these systems, NIR fluorescent contrast agents can be visualized with acquisition times in the millisecond range, enabling real-time guidance during surgery [79]. Development of novel NIR fluorescent contrast agents is dependent on the availability of clinically compatible fluorophores [80]. To date only two fluorophores have been reported to be in the process of clinical translation: IRDye 800CW (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA) and ZW800-1 (The FLARE Foundation, Wayland, MA, USA) [80,94]. Both compounds are small molecules, characterized as non-toxic, and an can be conjugated to targeting moieties. They are characterized by having renal and hepatic clearance, enabling these agents to be used for imaging of ureters and bile ducts [80,95].

Additionally, organic fluorophores can be conjugated to SNAP-tag fusion proteins to generate imaging probes for in vitro and in vivo diagnostics [96,97]. SNAP-tag imaging probes have advantages over autofluorescent protein-antibody probes. These advantages include improved brightness and increased photostability, no chromophore maturation or impact on the labeled proteins function, and shorter half-life with increased retention time of the probe [98,99,100,101]. The tumor retention of a probe for successful imaging is dependent on its binding affinity and internalization, whilst for novel antibody fragments, this binding affinity varies when forming part of fusion proteins [102]. It is thus essential that the above-mentioned parameters are continuously optimized. To this extent, Niesen et al. [103] recently developed a convenient, SNAP-tag-specific SPR spectroscopy assay to measure the binding affinity and functionality of novel scFv-SNAP-tag fusion proteins for use in future immunotherapeutic production.

The size of the probe also affects both its ability to penetrate tissue and the rate at which it is cleared from circulation [104]. Because deletions in the SNAP-tag gene sequence have reduced its size to 20 kDa compared to that of the wild-type AGT protein or endogenous fluorescent proteins, SNAP-tag has a much higher penetrability than its larger counterparts. It is in fact virtually unrestricted in its ability to access any cellular compartment [99]. The intermediate size of the scFv/SNAP construct (∼48 kDa) facilitates rapid accumulation and efficacious tumor binding soon after injection together with rapid renal clearance, while still producing a high tumor-to-background ratio with high tumor visualization and low nonspecific background signal [104]. This is ideal for receptor expression monitoring when imaging is done within a short period and further enhances the tumor signal as excess probe is rapidly cleared from the bloodstream, minimizing background interference. [98,104,105,106].

In a study by Gong et al. [106], the NIR fluorescent SNAP-tag substrate BG-800 was synthesized by conjugating an IRDye 800CW to the benzyl-guanine amino group (BG-NH2) of the protein tag. Because BG-800 was cell impermeable, the SNAPf-ADRβ2 fusion protein was used in such a way that ADRβ2 directed the localization of SNAPf fusion protein to the cell membrane. BG-800 reacted with SNAPf-ADRβ2 in both cell lysate and live cell culture [106]. The tumors expressing SNAPf-ADRβ2 was then visualized using BG-800 conjugated to the IRDye 800CW. In another study, rapid optical imaging of EGF receptor expression was monitored with an EGFR-specific 425 (scFv) SNAP fusion protein labeled with the NIR dye BG-747 [104]. The 425 (scFv) SNAP fusion protein accumulated rapidly and specifically at the tumor site. Its small size allowed efficient renal clearance and a high tumor-to-background ratio [104].

Nanobodies and affibodies have recently become tumor imaging agents through conjugation to the IRDye 800CW. Affibodies are derived from the staphylococcal protein A and are attractive for imaging purposes due to their small size and low immunogenicity [107,108]. Simlarly, nanobodies are single-domain antibodies derived from the heavy chain of the camelidae family [109]. Unlike mAbs, these fragments do not need to undergo partial unfolding as their hydrophobic patches are adequately exposed to facilitate binding to receptors [110]. An anti-EGFR nanobody 7D12 and cetuximab were conjugated to IRDye800CW to visualize tumors. 7D12 allowed the visualization of tumors as early as 30 min post injection in comparison to cetuximab [111]. In another similar study, the EGFR-specific affibody (Aff800), panitumumab (Pan800), and EGF (EGF800) were labeled with the IRDye 800CW. Highest binding affinities were noticed for Pan800 and aff800, and the EGFR tumors generated the highest signals for Pan800 and aff800 [112]. These studies prove that nanobodies and affibodies can similarly be co-expressed with SNAP-tag and conjugated to organic fluorophores for imaging of tumors in ovarian or breast cancer, and research in this area is ongoing.

Fluorescence optical imaging also has the advantage of multiple channels which can be employed to image two or more targets simultaneously. The clinical antibodies, cetuximab and trastuzumab were labeled with Cy5.5 and Cy7, respectively [113]. When mice were injected with a cocktail of cetuximab-Cy5.5 and trastuzumab-Cy7, A431 and 3T3/HER2+ tumors could be detected distinctly based on the Cy5.5 and Cy7 spectral images [113]. In a subsequent study three antibodies (cetuximab, trastuzumab and daclizumab) were labeled with three different fluorophores (Cy5, Cy7 and AlexaFluor700). Spectrally resolved fluorescence imaging showed that these probes clearly distinguished their respective targeting tumors (A431, 3T3/HER2+ and SP2-Tac) based on their distinct optical spectra [114]. These studies complement recent research into dual-color single molecule imaging of SNAP-tag fusion proteins using an optimal dye pair [101]. The labeling was performed on SNAP-EGFR with BG-Dy549 (green) and BG-CF633 (red) [101]. This study demonstrated how a single SNAP-tag fusion protein can be labeled with a selection of differently colored fluorophores without the need to separately clone each and opens the way for a potentially powerful method of visualizing different antigens on one tumor without worrying about tumor heterogeneity.

Conclusion

Efforts in the treatment of breast and ovarian cancer will continue to focus on personalizing treatment to the patient and the tumor. Immunotherapy achieves this goal as it blocks the growth of cancer cells by interfering with specific targeted molecules needed for carcinogenesis and tumor growth, and ADCs and fusion proteins are types of immunotherapeutic agents. A plethora of ADCs currently exist to treat ovarian and breast cancer with a few being approved and others still in clinical trials. The only ADC that has currently been approved for metastatic breast cancer is Kadcyla. Human antibody fusion proteins are now emerging therapeutic tools due to their homogeneity in combining functionality in one single construct by the fusing of protein and antibody domains. The optimal stoichiometric drug-to-antibody ratio afforded by the SNAP-tag fusion protein which enhances its specificity along with its applications in imaging and PIT only serve to exemplify the attractive diagnostic and therapeutic potential of fusion proteins in targeted cancer treatment.

Disclosure Statement

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Çelik A, Acar M, Erkul CM, Gunduz E, Gunduz M. Relationship of breast cancer with ovarian cancer. In: Gunduz M, editor. A Concise Review of Molecular Pathology of Breast Cancer. Rijeka: InTech; 2015. www.intechopen.com/books/a-concise-review-of-molecular-pathology-of-breast-cancer/relationship-of-breast-cancer-with-ovarian-cancer (last accessed August 22, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Permuth-Wey J, Sellers TA. Epidemiology of ovarian cancer. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;472:413–437. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-492-0_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Leon MP. in Familial and Hereditary Tumors. Heidelberg: Springer; 1994. Oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes; pp. 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slamon DJ, Godolphin W, Jones LA, Holt JA, Wong SG. Studies of the HER-2/neu proto-oncogene in human breast and ovarian cancer. Science. 1989;244:707. doi: 10.1126/science.2470152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Groep P, van der Wall E, van Diest PJ. Pathology of hereditary breast cancer. Cell Oncol. 2011;34:71–88. doi: 10.1007/s13402-011-0010-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parise CA, Caggiano V. Breast cancer survival defined by the ER/PR/HER2 subtypes and a surrogate classification according to tumor grade and immunohistochemical biomarkers. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2014;2014:469251. doi: 10.1155/2014/469251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green A, Powe D, Rakha E, Soria D, Lemetre C, Nolan C, Barros F, Macmillan R, Garibaldi J, Ball G. Identification of key clinical phenotypes of breast cancer using a reduced panel of protein biomarkers. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:1886–1894. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wahba HA, El-Hadaad HA. Current approaches in treatment of triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Biol Med. 2015;12:106–116. doi: 10.7497/j.issn.2095-3941.2015.0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurman RJ, Shih I-M. The Origin and pathogenesis of epithelial ovarian cancer-a proposed unifying theory. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:433–443. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181cf3d79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nogales FF, Dulcey I, Preda O. Germ cell tumors of the ovary: an update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138:351–362. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2012-0547-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haroon S, Zia A, Idrees R, Memon A, Fatima S, Kayani N. Clinicopathological spectrum of ovarian sex cord-stromal tumors; 20 years' retrospective study in a developing country. J Ovarian Res. 2013;6:87. doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-6-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szender JB, Papanicolau-Sengos A, Eng KH, Miliotto AJ, Lugade AA, Gnjatic S, Matsuzaki J, Morrison CD, Odunsi K. NY-ESO-1 expression predicts an aggressive phenotype of ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;145:420–425. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.03.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kloudová K, Hromádková H, Partlová S, Brtnický T, Rob L, Bartůňková J, Hensler M, Halaška MJ, Špíšek R, Fialová A. Expression of tumor antigens on primary ovarian cancer cells compared to established ovarian cancer cell lines. Oncotarget. 2016;7:46120. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Munagala R, Aqil F, Gupta RC. Promising molecular targeted therapies in breast cancer. Indian J Pharmacol. 2011;43:236. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.81497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fiszman GL, Jasnis MA. Molecular mechanisms of trastuzumab resistance in HER2 overexpressing breast cancer. Int J Breast Cancer. 2011;2011:352182. doi: 10.4061/2011/352182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spector N, Xia W, El-Hariry I, Yarden Y, Bacus S. HER2 therapy. Small molecule HER-2 tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:205. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alvarez RH, Valero V, Hortobagyi GN. Emerging targeted therapies for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3366–3379. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferrara N. Vascular endothelial growth factor as a target for anticancer therapy. Oncologist. 2004;9((suppl 1)):2–10. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-suppl_1-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buchbinder EI, Desai A. CTLA-4 and PD-1 pathways: similarities, differences, and implications of their inhibition. Am J Clin Oncol. 2016;39:98–106. doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meehan RS, Chen AP. New treatment option for ovarian cancer: PARP inhibitors. Gynecol Oncol Res Pract. 2016;3:3. doi: 10.1186/s40661-016-0024-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papa A, Caruso D, Strudel M, Tomao S, Tomao F. Update on Poly-ADP-ribose polymerase inhibition for ovarian cancer treatment. J Translat Med. 2016;14:267. doi: 10.1186/s12967-016-1027-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Konecny G, Kristeleit R. PARP inhibitors for BRCA1/2-mutated and sporadic ovarian cancer: current practice and future directions. Br J Cancer. 2016;115:1157–1173. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao L, Ren T-H, Wang DD. Clinical pharmacology considerations in biologics development. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2012;33:1339–1347. doi: 10.1038/aps.2012.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chames P, Van Regenmortel M, Weiss E, Baty D. Therapeutic antibodies: successes, limitations and hopes for the future. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157:220–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujimori K, Covell DG, Fletcher JE, Weinstein JN. A modeling analysis of monoclonal antibody percolation through tumors: a binding-site barrier. J Nucl Med. 1990;31:1191–1198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strome SE, Sausville EA, Mann D. A mechanistic perspective of monoclonal antibodies in cancer therapy beyond target-related effects. Oncologist. 2007;12:1084–1095. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-9-1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adams GP, Schier R, McCall AM, Simmons HH, Horak EM, Alpaugh RK, Marks JD, Weiner LM. High affinity restricts the localization and tumor penetration of single-chain fv antibody molecules. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4750–4755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beckman RA, Weiner LM, Davis HM. Antibody constructs in cancer therapy. Cancer. 2007;109:170–179. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Young PA, Morrison SL, Timmerman JM. Antibody-cytokine fusion proteins for treatment of cancer: engineering cytokines for improved efficacy and safety. Semin Oncol. 2014;41:623–636. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diamantis N, Banerji U. Antibody-drug conjugates - an emerging class of cancer treatment. B J Cancer. 2016;114:362–367. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu J, Jiang F, Lu A, Zhang G. Linkers having a crucial role in antibody-drug conjugates. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:561. doi: 10.3390/ijms17040561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chudasama V, Maruani A, Caddick S. Recent advances in the construction of antibody-drug conjugates. Nat Chem. 2016;8:114. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen X, Zaro JL, Shen W-C. Fusion protein linkers: property, design and functionality. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65:1357–1369. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sievers EL, Senter PD. Antibody-drug conjugates in cancer therapy. Annu Rev Med. 2013;64:15–29. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-050311-201823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deng S, Lin Z, Li W. Recent advances in antibody-drug conjugates for breast cancer treatment. Curr Med Chem. 2017 doi: 10.2174/0929867324666170530092350. doi: 10.2174/0929867324666170530092350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weidle UH, Schneider B, Georges G, Brinkmann U. Genetically engineered fusion proteins for treatment of cancer. Cancer Genomics-Proteomics. 2012;9:357–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huston JS, Levinson D, Mudgett-Hunter M, Tai M-S, Novotný J, Margolies MN, Ridge RJ, Bruccoleri RE, Haber E, Crea R. Protein engineering of antibody binding sites: recovery of specific activity in an anti-digoxin single-chain Fv analogue produced in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:5879–5883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.16.5879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Becker JC, Pancook JD, Gillies SD, Mendelsohn J, Reisfeld RA. Eradication of human hepatic and pulmonary melanoma metastases in SCID mice by antibody-interleukin 2 fusion proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:2702–2707. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gillies SD, Lan Y, Williams S, Carr F, Forman S, Raubitschek A, Lo K-M. An anti-CD20-IL-2 immunocytokine is highly efficacious in a SCID mouse model of established human B lymphoma. Blood. 2005;105:3972–3978. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schliemann C, Palumbo A, Zuberbühler K, Villa A, Kaspar M, Trachsel E, Klapper W, Menssen HD, Neri D. Complete eradication of human B-cell lymphoma xenografts using rituximab in combination with the immunocytokine L19-IL2. Blood. 2009;113:2275–2283. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-160747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spitaleri G, Berardi R, Pierantoni C, De Pas T, Noberasco C, Libbra C, González-Iglesias R, Giovannoni L, Tasciotti A, Neri D. Phase I/II study of the tumour-targeting human monoclonal antibody-cytokine fusion protein L19-TNF in patients with advanced solid tumours. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2013;139:447–455. doi: 10.1007/s00432-012-1327-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoo E, Vasuthasawat A, Tran D, Lichtenstein A, Morrison S. Anti-CD138-targeted interferon is a potent therapeutic against multiple myeloma. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2015;35:281–291. doi: 10.1089/jir.2014.0125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sarwar S, Bakbak B, Sadiq MA, Sepah YJ, Shah SM, Ibrahim M, Do DV, Nguyen QD. Fusion Proteins: Aflibercept (VEGF Trap-Eye) Dev Ophthalmol. 2016;55:282–294. doi: 10.1159/000439008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stewart MW. Aflibercept (VEGF-TRAP): the next anti-VEGF drug. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2011;10:497–508. doi: 10.2174/187152811798104872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu FT, Paez-Ribes M, Xu P, Man S, Bogdanovic E, Thurston G, Kerbel RS. Aflibercept and Ang1 supplementation improve neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy in a preclinical model of resectable breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2016;6:36694. doi: 10.1038/srep36694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kumtepe Y, Halici Z, Sengul O, Kunak CS, Bayir Y, Kilic N, Cadirci E, Pulur A, Bayraktutan Z. High serum HTATIP2/TIP30 level in serous ovarian cancer as prognostic or diagnostic marker. Eur J Med Res. 2013;18:18. doi: 10.1186/2047-783X-18-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garg G, Gibbs J, Belt B, Powell MA, Mutch DG, Goedegebuure P, Collins L, Piwnica-Worms D, Hawkins WG, Spitzer D. Novel treatment option for MUC16-positive malignancies with the targeted TRAIL-based fusion protein Meso-TR3. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhong J, Kang J, Wang X, Jiang W, Liao H, Yuan J. TAT-OSBP-1-MKK6 (E), a novel TAT-fusion protein with high selectivity for human ovarian cancer, exhibits anti-tumor activity. Med Oncol. 2015;32:118. doi: 10.1007/s12032-015-0495-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Faltas B, Goldenberg DM, Ocean AJ, Govindan SV, Wilhelm F, Sharkey RM, Hajdenberg J, Hodes G, Nanus DM, Tagawa ST. Sacituzumab govitecan, a novel antibody-drug conjugate, in patients with metastatic platinum-resistant urothelial carcinoma. Clin Genitourinary Cancer. 2016;14:e75–e79. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cardillo TM, Govindan SV, Sharkey RM, Trisal P, Arrojo R, Liu D, Rossi EA, Chang C-H, Goldenberg DM. Sacituzumab govitecan (Immu-132), an anti-Trop-2/Sn-38 antibody-drug conjugate: characterization and efficacy in pancreatic, gastric, and other cancers. Bioconjug Chem. 2015;26:919–931. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yardley DA, Weaver R, Melisko ME, Saleh MN, Arena FP, Forero A, Cigler T, Stopeck A, Citrin D, Oliff I. EMERGE: a randomized phase II study of the antibody-drug conjugate glembatumumab vedotin in advanced glycoprotein NMB-expressing breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1609–1619. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.2959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krop IE, Kim SB, González-Martín A, LoRusso PM, Ferrero JM, Smitt M, Yu R, Leung AC, Wildiers H, TH3RESA study collaborators Trastuzumab emtansine versus treatment of physicianʼs choice for pretreated HER2-positive advanced breast cancer (TH3RESA): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:689–699. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70178-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moore KN, Martin LP, O'Malley DM, Matulonis UA, Konner JA, Perez RP, Bauer TM, Ruiz-Soto R, Birrer MJ. Safety and activity of mirvetuximab soravtansine (IMGN853), a folate receptor alpha-targeting antibody-drug conjugate, in platinum-resistant ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer: a phase I expansion study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;35:1112–1118. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.9538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thomas LJ, Vitale L, O'Neill T, Dolnick RY, Wallace PK, Minderman H, Gergel LE, Forsberg EM, Boyer JM, Storey JR. Development of a novel antibody-drug conjugate for the potential treatment of ovarian, lung, and renal cell carcinoma expressing TIM-1. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016;15:2946–2954. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sachdev J, Maitland M, Sharma M, Moreno V, Boni V, Kummar S, Gibson B, Xuan D, Joh T, Powell E. A phase 1 study of PF-06647020, an antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) targeting protein tyrosine kinase 7 (PTK7), in patients with advanced solid tumors including platinum resistant ovarian cancer (OVCA) Ann Oncol. 2016;27((suppl 6)):LBA35. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weekes CD, Lamberts LE, Borad MJ, Voortman J, McWilliams RR, Diamond JR, De Vries EG, Verheul HM, Lieu CH, Kim GP. Phase I study of DMOT4039A, an antibody-drug conjugate targeting mesothelin, in patients with unresectable pancreatic or platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016;15:439–447. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bodyak N, Yurkovetskiy A, Yin M, Gumerov D, Bollu R, Conlon P, Gurijala VR, McGillicuddy D, Stevenson C, Ter-Ovanesyan E. Discovery and preclinical development of a highly potent NaPi2b-targeted antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) with significant activity in patient-derived non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) xenograft models. Cancer Res. 2016;76((14 suppl)) abstract 1194. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hussain AF, Krüger HR, Kampmeier F, Weissbach T, Licha K, Kratz F, Haag R, Calderón M, Barth S. Targeted delivery of dendritic polyglycerol-doxorubicin conjugates by scFv-SNAP fusion protein suppresses EGFR+ cancer cell growth. Biomacromolecules. 2013;14:2510–2520. doi: 10.1021/bm400410e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Perez HL, Cardarelli PM, Deshpande S, Gangwar S, Schroeder GM, Vite GD, Borzilleri RM. Antibody-drug conjugates: current status and future directions. Drug Discov Today. 2014;19:869–881. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Axup JY, Bajjuri KM, Ritland M, Hutchins BM, Kim CH, Kazane SA, Halder R, Forsyth JS, Santidrian AF, Stafin K. Synthesis of site-specific antibody-drug conjugates using unnatural amino acids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:16101–16106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211023109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schmidt SR. Fusion Protein Technologies for Biopharmaceuticals: Applications and Challenges. Hoboken: Wiley & Sons; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Keppler A, Gendreizig S, Gronemeyer T, Pick H, Vogel H, Johnsson K. A general method for the covalent labeling of fusion proteins with small molecules in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:86–89. doi: 10.1038/nbt765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Juillerat A, Gronemeyer T, Keppler A, Gendreizig S, Pick H, Vogel H, Johnsson K. Directed evolution of O 6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase for efficient labeling of fusion proteins with small molecules in vivo. Chem Biol. 2003;10:313–317. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(03)00068-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cole NB. Site-specific protein labeling with SNAP-tags. Curr Protoc Protein Sci. 2013;73 doi: 10.1002/0471140864.ps3001s73. Unit 30.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gautier A, Juillerat A, Heinis C, Corrêa IR, JR, Kindermann M, Beaufils F, Johnsson K. An engineered protein tag for multiprotein labeling in living cells. Chem Biol. 2008;15:128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sumzin N, Moroz M, Ponomarev V. A New approach to SNAP-tag technology as a possible imaging tool for translational research. FASEB J. 2015;29((1 suppl)):577. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Huang Z, Xu H, Meyers AD, Musani AI, Wang L, Tagg R, Barqawi AB, Chen YK. Photodynamic therapy for treatment of solid tumors - potential and technical challenges. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2008;7:309–320. doi: 10.1177/153303460800700405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Van Dongen G, Visser G, Vrouenraets M. Photosensitizer-antibody conjugates for detection and therapy of cancer. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2004;56:31–52. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hong G, Antaris AL, Dai H. Near-infrared fluorophores for biomedical imaging. Nat Biomed Engin. 2017;1:0010. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mitsunaga M, Nakajima T, Sano K, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. Near-infrared theranostic photoimmunotherapy (PIT): repeated exposure of light enhances the effect of immunoconjugate. Bioconjug Chem. 2012;23:604–609. doi: 10.1021/bc200648m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ogata F, Nagaya T, Nakamura Y, Sato K, Okuyama S, Maruoka Y, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. Near-infrared photoimmunotherapy: a comparison of light dosing schedules. Oncotarget. 2017;8:35069. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mallidi S, Anbil S, Bulin A-L, Obaid G, Ichikawa M, Hasan T. Beyond the barriers of light penetration: strategies, perspectives and possibilities for photodynamic therapy. Theranostics. 2016;6:2458–2487. doi: 10.7150/thno.16183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mitsunaga M, Ogawa M, Kosaka N, Rosenblum LT, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. Cancer cell-selective in vivo near infrared photoimmunotherapy targeting specific membrane molecules. Nat Med. 2011;17:1685–1691. doi: 10.1038/nm.2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Woitok M, Klose D, Niesen J, Richter W, Abbas M, Stein C, Fendel R, Bialon M, Püttmann C, Fischer R. The efficient elimination of solid tumor cells by EGFR-specific and HER2-specific scFv-SNAP fusion proteins conjugated to benzylguanine-modified auristatin F. Cancer Lett. 2016;381:323–330. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hussain AF, Kampmeier F, von Felbert V, Merk H-F, Tur MK, Barth S. SNAP-tag technology mediates site specific conjugation of antibody fragments with a photosensitizer and improves target specific phototoxicity in tumor cells. Bioconjug Chem. 2011;22:2487–2495. doi: 10.1021/bc200304k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.von Felbert V, Bauerschlag D, Maass N, Bräutigam K, Meinhold-Heerlein I, Woitok M, Barth S, Hussain AF. A specific photoimmunotheranostics agent to detect and eliminate skin cancer cells expressing EGFR. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2016;142:1003–1011. doi: 10.1007/s00432-016-2122-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bauerschlag D, Meinhold-Heerlein I, Maass N, Bleilevens A, Bräutigam K, Al Rawashdeh We, Di Fiore S, Haugg AM, Gremse F, Steitz J. Detection and specific elimination of EGFR+ ovarian cancer cells using a near infrared photoimmunotheranostic approach. Pharm Res. 2017;34:696–703. doi: 10.1007/s11095-017-2096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sato K, Watanabe R, Hanaoka H, Harada T, Nakajima T, Kim I, Paik CH, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. Photoimmunotherapy: comparative effectiveness of two monoclonal antibodies targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor. Mol Oncol. 2014;8:620–632. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nagaya T, Nakamura Y, Sato K, Zhang Y-F, Ni M, Choyke PL, Ho M, Kobayashi H. Near infrared photoimmunotherapy with an anti-mesothelin antibody. Oncotarget. 2016;7:23361. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vahrmeijer AL, Hutteman M, Van Der Vorst JR, Van De Velde CJ, Frangioni JV. Image-guided cancer surgery using near-infrared fluorescence. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10:507–518. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Veronesi U, Volterrani F, Luini A, Saccozzi R, Del Vecchio M, Zucali R, Galimberti V, Rasponi A, Di Re E, Squicciarini P. Quadrantectomy versus lumpectomy for small size breast cancer. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1990;26:671–673. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(90)90114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Martinek IE, Kehoe S. When should surgical cytoreduction in advanced ovarian cancer take place? J Oncol. 2010;2010:852028. doi: 10.1155/2010/852028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.McCreath WA, Chi DS. Surgical cytoreduction in ovarian cancer. Oncology (Williston Park) 2004;18:645–664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chi D, Eisenhauer E, Lang J, Huh J, Haddad L, Abu-Rustum N, Sonoda Y, Levine D, Hensley M, Barakat R. What is the optimal goal of primary cytoreductive surgery for bulky stage IIIC epithelial ovarian carcinoma (EOC)? Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103:559–564. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kubben PL, ter Meulen KJ, Schijns OE, ter Laak-Poort MP, van Overbeeke JJ, van Santbrink H. Intraoperative MRI-guided resection of glioblastoma multiforme: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:1062–1070. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ueland FR. A perspective on ovarian cancer biomarkers: past, present and yet-to-come. Diagnostics. 2017;7:14. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics7010014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gotoh K, Yamada T, Ishikawa O, Takahashi H, Eguchi H, Yano M, Ohigashi H, Tomita Y, Miyamoto Y, Imaoka S. A novel image‐guided surgery of hepatocellular carcinoma by indocyanine green fluorescence imaging navigation. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100:75–79. doi: 10.1002/jso.21272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Troyan SL, Kianzad V, Gibbs-Strauss SL, Gioux S, Matsui A, Oketokoun R, Ngo L, Khamene A, Azar F, Frangioni JV. The FLARE™ intraoperative near-infrared fluorescence imaging system: a first-in-human clinical trial in breast cancer sentinel lymph node mapping. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:2943–2952. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0594-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mieog JSD, Troyan SL, Hutteman M, Donohoe KJ, van der Vorst JR, Stockdale A, Liefers G-J, Choi HS, Gibbs-Strauss SL, Putter H. Toward optimization of imaging system and lymphatic tracer for near-infrared fluorescent sentinel lymph node mapping in breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:2483–2491. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1566-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cahill RA, Anderson M, Wang LM, Lindsey I, Cunningham C, Mortensen NJ. Near-infrared (NIR) laparoscopy for intraoperative lymphatic road-mapping and sentinel node identification during definitive surgical resection of early-stage colorectal neoplasia. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:197–204. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1854-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.van der Poel HG, Buckle T, Brouwer OR, Olmos RAV, van Leeuwen FW. Intraoperative laparoscopic fluorescence guidance to the sentinel lymph node in prostate cancer patients: clinical proof of concept of an integrated functional imaging approach using a multimodal tracer. Eur Urol. 2011;60:826–833. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Borofsky MS, Gill IS, Hemal AK, Marien TP, Jayaratna I, Krane LS, Stifelman MD. Near‐infrared fluorescence imaging to facilitate super‐selective arterial clamping during zero‐ischaemia robotic partial nephrectomy. BJU Int. 2013;111((4)):604–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Spinoglio G, Priora F, Bianchi PP, Lucido FS, Licciardello A, Maglione V, Grosso F, Quarati R, Ravazzoni F, Lenti LM. Real-time near-infrared (NIR) fluorescent cholangiography in single-site robotic cholecystectomy (SSRC): a single-institutional prospective study. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:2156–2162. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2733-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Oliveira S. Considerations on the advantages of small tracers for optical molecular imaging. J Mol Biol. 2015;2:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 95.van den Vorst JR. Near-Infrared Fluorescence-Guided Surgery: Pre-Clinical Validation and Clinical Translation. Department Surgery, Faculty of Medicine/Leiden University Medical Center (LUMC), Leiden University; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kampmeier F, Ribbert M, Nachreiner T, Dembski S, Beaufils F, Brecht A, Barth S. Site-specific, covalent labeling of recombinant antibody fragments via fusion to an engineered version of 6-O-alkylguanine DNA alkyltransferase. Bioconjug Chem. 2009;20:1010–1015. doi: 10.1021/bc9000257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Amoury M, Blume T, Brehm H, Niesen J, Tenhaef N, Barth S, Gattenlohner S, Helfrich W, Fitting J, Nachreiner T. SNAP-tag based agents for preclinical in vitro imaging in malignant diseases. Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19:5429–5436. doi: 10.2174/13816128113199990405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pardo A, Stöcker M, Kampmeier F, Melmer G, Fischer R, Thepen T, Barth S. In vivo imaging of immunotoxin treatment using Katushka-transfected A-431 cells in a murine xenograft tumour model. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2012;61:1617–1626. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1219-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Keppler A, Kindermann M, Gendreizig S, Pick H, Vogel H, Johnsson K. Labeling of fusion proteins of O 6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase with small molecules in vivo and in vitro. Methods. 2004;32:437–444. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Klose D, Saunders U, Barth S, Fischer R, Jacobi AM, Nachreiner T. Novel fusion proteins for the antigen-specific staining and elimination of B cell receptor-positive cell populations demonstrated by a tetanus toxoid fragment C (TTC) model antigen. BMC Biotechnol. 2016;16:18. doi: 10.1186/s12896-016-0249-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bosch PJ, Corrêa IR, Sonntag MH, Ibach J, Brunsveld L, Kanger JS, Subramaniam V. Evaluation of fluorophores to label SNAP-tag fused proteins for multicolor single-molecule tracking microscopy in live cells. Biophys J. 2014;107:803–814. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Choudhary S, Barth S, Verma R. SNAP-Tag technology: a promising tool for ex vivo immunophenotyping. Mol Diagnosis Ther. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s40291-017-0263-2. DOI: 10.1007/s40291-017-0263-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Niesen J, Sack M, Seidel M, Fendel R, Barth S, Fischer R, Stein C. SNAP-tag technology: a useful tool to determine affinity constants and other functional parameters of novel antibody fragments. Bioconjug Chem. 2016;27:1931–1941. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.6b00315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kampmeier F, Niesen J, Koers A, Ribbert M, Brecht A, Fischer R, Kießling F, Barth S, Thepen T. Rapid optical imaging of EGF receptor expression with a single-chain antibody SNAP-tag fusion protein. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:1926–1934. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1482-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bojkowska K, de Sio FS, Barde I, Offner S, Verp S, Heinis C, Johnsson K, Trono D. Measuring in vivo protein half-life. Chem Biol. 2011;18:805–815. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gong H, Kovar JL, Baker B, Zhang A, Cheung L, Draney DR, Corrêa IR, Jr, Xu M-Q, Olive DM. Near-infrared fluorescence imaging of mammalian cells and xenograft tumors with SNAP-tag. PloS One. 2012;7:e34003. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Eklund M, Axelsson L, Uhlén M, Nygren PÅ. Anti‐idiotypic protein domains selected from protein A‐based affibody libraries. Proteins. 2002;48:454–462. doi: 10.1002/prot.10169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gao J, Chen K, Miao Z, Ren G, Chen X, Gambhir SS, Cheng Z. Affibody-based nanoprobes for HER2-expressing cell and tumor imaging. Biomaterials. 2011;32:2141–2148. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.11.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Oliveira S, Schiffelers RM, van der Veeken J, van der Meel R, Vongpromek R, en Henegouwen PMvB, Storm G, Roovers RC. Downregulation of EGFR by a novel multivalent nanobody-liposome platform. J Control Release. 2010;145:165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ding L, Tian C, Feng S, Fida G, Zhang C, Ma Y, Ai G, Achilefu S, Gu Y. Small sized EGFR1 and HER2 specific bifunctional antibody for targeted cancer therapy. Theranostics. 2015;5:378–398. doi: 10.7150/thno.10084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Oliveira S, Van Dongen GA, Walsum MS-v, Roovers RC, Stam JC, Mali W, Van Diest PJ, van Bergen en Henegouwen PM. Rapid visualization of human tumor xenografts through optical imaging with a near-infrared fluorescent anti-epidermal growth factor receptor nanobody. Mol Imaging. 2012;11:33–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gong H, Kovar JL, Cheung L, Rosenthal EL, Olive DM. A comparative study of affibody, panitumumab, and EGF for near-infrared fluorescence imaging of EGFR-and EGFRvIII-expressing tumors. Cancer Biol Ther. 2014;15:185–193. doi: 10.4161/cbt.26719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Barrett T, Koyama Y, Hama Y, Ravizzini G, Shin IS, Jang B-S, Paik CH, Urano Y, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. In vivo diagnosis of epidermal growth factor receptor expression using molecular imaging with a cocktail of optically labeled monoclonal antibodies. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:6639–6648. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Koyama Y, Barrett T, Hama Y, Ravizzini G, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. In vivo molecular imaging to diagnose and subtype tumors through receptor-targeted optically labeled monoclonal antibodies. Neoplasia. 2007;9:1021–1029. doi: 10.1593/neo.07787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]