Abstract

Purpose of the Study

To describe an unusual brown pigmented lesion of the conjunctiva in an anophthalmic socket in a 16-year-old male.

Procedures

A 16-year-old male patient presented with socket irritation whilst wearing an artificial eye due to meibomian gland dysfunction. An area of flat, subepithelial, dark brown pigmentation with irregular and indistinct borders on the bulbar conjunctiva of the anophthalmic socket was seen. The patient believed it had been present for at least 2 years. His past ocular history was of childhood trauma to the right eye at the age of 9 years, and he underwent primary enucleation and hydroxyapatite orbital implant insertion at that time. Unfortunately, the implant extruded and was removed a year later.

Results

An incisional biopsy of the pigmented lesion showed a conjunctival, subepithelial bland spindle cell melanocytic lesion, with uniform-sized and -shaped melanosomes. Immunohistochemistry showed the cells to express Melan A and HMB45 and they were negative for CD68 and pan-cytokeratins. The features were of a common blue naevus.

Conclusion

This is the first documentation of a post-enucleation conjunctival naevus in an anophthalmic socket. We propose a pathogenesis and suggest surveillance as there is a risk of transformation to melanoma.

Keywords: Post-enucleation, Anophthalmic socket, Naevus, Conjunctiva

Introduction

Benign and malignant tumours of the anophthalmic conjunctiva are a very rare occurrence. The literature documents only a handful of cases with squamous cell carcinoma being the commonest tumour [1, 2, 3]. Other documented tumours include invasive sebaceous carcinoma [4] and invasive melanoma [5]. We report on the clinical and histopathological features of a 16 year-old male who developed brown pigmentation beneath the epithelium of the bulbar conjunctiva over a period of 2 years.

Case Report

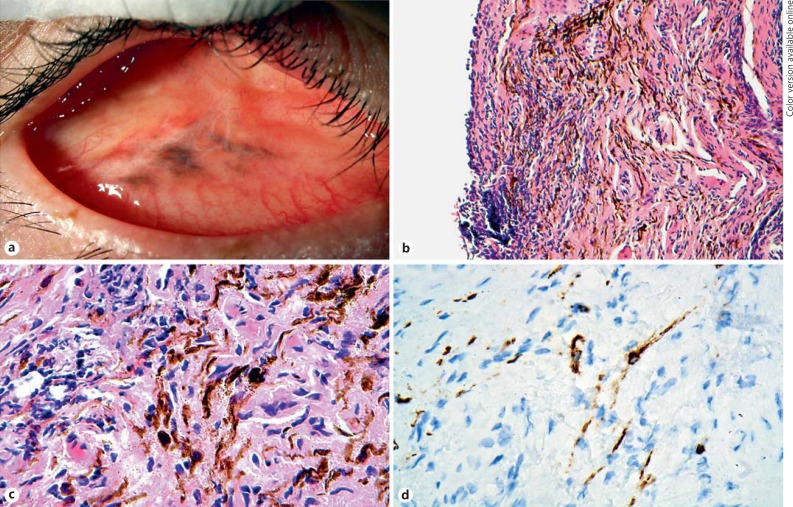

A 16-year-old male patient presented with socket irritation whilst wearing his artificial eye due to meibomian gland dysfunction. On examination, there was an area of flat, subepithelial, dark brown pigmentation with irregular and indistinct borders on the bulbar conjunctiva of the anophthalmic socket (Fig. 1a). The patient believed it had been present for at least 2 years. His past ocular history was of childhood trauma to the right eye at the age of 9 years, and he underwent primary enucleation and hydroxyapatite orbital implant insertion at that time. Unfortunately, the implant extruded and was removed a year later. Otherwise he was fit and well; the patient had no personal or family history of any abnormal pigmentation of the skin, conjunctiva, or episclera, nor of melanoma. Review of systems was noncontributory.

Fig. 1.

a The brown pigmented socket lesion present within the bulbar conjunctiva. b Haematoxylin and eosin (HE)-stained section of the biopsy showing surface epithelium to the left and a brown-pigmented lesion within a cellular substantia propria. c HE (higher power of b) showing the wavy spindled cells containing brown melanosomes and indistinct nuclei, amongst fibroblasts, established stromal fibrosis, and blood vessels. d The spindle cells are positive immunohistochemically for Melan A. The immunohistochemistry was performed on hydrogen peroxide-bleached sections to extinguish all melanosome melanin pigment. The brown colour of the spindle cells represents Melan A chromogenic staining and not melanosome melanin pigment.

The patient underwent incisional biopsy to ascertain the nature of the pigmentation. The biopsy was fixed in standard 10% buffered formalin and submitted to the ophthalmic pathology laboratory. The laboratory received a light brown piece of gelatinous tissue, 3 × 2 × 1 mm. Histology showed conjunctival tissue containing heavily melanised cells, concentrated in the subepithelial zone (Fig. 1b). The cells were spindled and wavy with tightly packed, circular melanosomes of consistent size (Fig. 1c). To reveal the nuclear details, the sections were bleached overnight with 2% hydrogen peroxide and stained with conventional haematoxylin and eosin. The nuclei were oval shaped and with bland chromatin and no pleomorphism. Nucleoli were not readily observed and the cells did not exhibit mitotic activity. The tumour cells were embedded within a fibrotic stroma that showed patchy chronic inflammation. Immunohistochemistry (performed on bleached sections) revealed that the cells were positive for Melan A (Fig. 1d) and HMB45 (not shown) and negative for CD68 and cytokeratin. The Ki67 proliferation fraction was zero. The morphological and immunohistochemical findings were those of a common blue naevus of the conjunctiva.

The clinicopathological differential diagnosis included melanophages, pigmented foreign body material [6], migrating pigment epithelial cells from the uvea or retinal pigment epithelium (given the history of trauma to the eye 7 years previous) [7], oculo(dermal) melanocytosis [8], and blue-naevus-like metastatic melanoma [9]. Melanophages were excluded by negative CD68 immunohistochemistry. Histology did not reveal any foreign material within the biopsy. Uveal pigment epithelial cells/retinal pigment epithelial cells are cytokeratin positive, but in this case, they were clearly negative. Blue-naevus-like metastatic melanoma, which can easily be mistaken for a benign blue naevus on morphology alone, was excluded by performing fluorescence in situ hybridisation using the commercially available Vysis 4-probe melanoma panel [10, 11]. This showed no gains or losses, confirming that the lesion in question was benign. Oculo(dermal) melanocytosis melanocytes can look identical to a blue naevus, but in this case, there were no skin, episcleral, or uveal manifestations of this condition.

Review of the previous enucleation specimen revealed a sutured corneal laceration and an acute, gram-positive cocci acute endophthalmitis. No melanocytic lesions were identified.

Discussion

Blue naevi are neural crest-derived melanocytic lesions most commonly found in the skin of the dorsum of the hands and feet, the scalp, and the sacrococcygeal regions, but may also present less frequently in mucosal membranes, such as the mouth, nose, and uterus [12]. They commonly appear in children and adolescents and represent arrested migration of melanocytes before reaching an epithelium. Various histological subtypes exist, namely “common,” “plaque-type,” “epithelioid,” and “cellular.” The epithelioid variant is associated with the Carney complex [12].

Blue naevi rarely occur in the conjunctiva. Jay [13] originally published a series of 229 naevi of which only 5 (2%) were histologically proven blue naevi. They can be solitary but more commonly present as combined lesions partnering with conventional conjunctival naevi [14]. Most are of “common” type, but “cellular” [15] and “epithelioid” variants [16] have been published, including 1 example that was multifocal [17]. One report documented malignant transformation in a cellular blue naevus that mimicked primary acquired melanosis [18].

In our case, clinically, the lesion was not “blue” but brown. This phenomenon was previously discussed by Eller and Bernardino [19] and is attributable to the thinner conjunctival layers over the blue naevus, which do not scatter light, as well as the thicker dermal collagen of the skin.

Previous cytological studies of the conjunctiva in anophthalmic sockets have shown squamous metaplasia and reduced goblet cell density as well as an increased nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio of the epithelium in response to irritation from implants [20]. There are several case reports of conjunctival tumours arising within the conjunctiva of anophthalmic sockets. These include invasive and in situ squamous cell carcinoma [1, 2, 3], sebaceous carcinoma [4], and invasive melanoma [5]. In the cases of squamous cell carcinoma, it is speculated to be the result of chronic irritation and micro-trauma following many decades of ocular prosthesis use causing squamous metaplasia and ultimately neoplasia [1, 2, 3]. The anophthalmic socket melanoma case was an 8-month-old child who underwent enucleation, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy for ipsilateral retinoblastoma and developed invasive melanoma of the conjunctiva after 3 years, with no recurrence 20 months after the excision [5].

It is interesting to note that the blue naevus occurred after the enucleation with implant placement. It may be that the blue naevus was always present but became pigmented over the last 2 years, especially so as the patient was 16 years old, an age at which naevi can undergo pigmentary changes secondary to sex hormone influences. An alternative interpretation is that the irritation of the socket implant may have led to the development of the blue naevus. There are several case reports that have documented the development of bona fide melanocytic naevi, including so-called “eruptive blue naevi” at sites of sunburn [21], previous trauma [22], and infection [23]. Mechanisms that have been proposed are the release of growth factors from keratinocytes and inflammatory cells triggering melanocyte proliferation [21, 22, 23]. To the best of the authors' knowledge, this is the first report of a conjunctival blue naevus occurring in an anophthalmic socket.

Statement of Ethics

The subject has given informed consent for this case report. The study was performed in accordance to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest and no financial interests.

References

- 1.Nguyen J, Ivan D, Esmaeli B. Conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma in the anophthalmic socket. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;24:98–101. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e31816381fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrett RV, Meyer DR, Carlson JA. Conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma in situ in the anophthalmic socket. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;26:52–53. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181b8e3bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Espana EM, Levine M, Schoenfield L, Singh AD. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia in an anophthalmic socket 60 years after enucleation. Surv Ophthalmol. 2011;56:539–543. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanaka T, Sato H, Tada A, Moriya T, Wada Y, Nishida K. Case of orbital sebaceous carcinoma developing twenty-seven years after enucleation. Jpn J Opthalmol. 2008;52:344–345. doi: 10.1007/s10384-008-0552-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahajan A, Shields CL, Eagle RC, Jr, Mashayekhi A, Freire JE, Shields JA. Conjunctival melanoma 3 years after radiation and chemotherapy for retinoblastoma. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2007;44:300–302. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20070901-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maudgil A, Wagner BE, Rundle P, Rennie IG, Mudhar HS. Ocular surface foreign bodies: novel findings mimicking ocular malignant melanoma. Eye (Lond) 2014;28:1370–1374. doi: 10.1038/eye.2014.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benson MT, Rennie I, Talbot J. External ocular pigmentation secondary to perforating eye injury. Br J Ophthalmol. 1990;74:251–253. doi: 10.1136/bjo.74.4.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fitzpatrick TB, Kitamura H, Kukita A, Zeller R. Ocular and dermal melanocytosis. AMA Arch Ophthalmol. 1956;56:830–832. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1956.00930040838004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Busam KJ. Metastatic melanoma to the skin simulating blue nevus. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:276–282. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199903000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerami P, Jewell SS, Morrison LE, Blondin B, Schulz J, Ruffalo T, Matushek P, 4th, Legator M, Jacobson K, Dalton SR, Charzan S, Kolaitis NA, Guitart J, Lertsbarapa T, Boone S, LeBoit PE, Bastian BC. Fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) as an ancillary diagnostic tool in the diagnosis of melanoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1146–1156. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181a1ef36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Busam KJ, Fang Y, Jhanwar SJ, Pulitzer MP, Marr B, Abramson DH. Distinction of conjunctival melanocytic nevi from melanomas by fluorescence in situ hybridisation. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:196–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2009.01488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zembowicz A, Pushkar AD. Blue nevi and variants: an update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:327–336. doi: 10.5858/2009-0733-RA.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jay B. Naevi and melanomata of the conjunctiva. Br J Ophthalmol. 1965;49:169–204. doi: 10.1136/bjo.49.4.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crawford JB, Howes EL, Jr, Char DH. Combined nevi of the conjunctiva. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:1121–1127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blicker JA, Rootman J, White VA. Cellular blue nevus of the conjunctiva. Ophthalmology. 1992;99:1714–1717. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31742-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jakobiec FA, Zuckerman BD, Berlin AJ, Odell P, MacRae DW, Tuthill RJ. Unusual melanocytic nevi of the conjunctiva. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985;100:100–113. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)74991-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berman EL, Shields CL, Sagoo MS, Eagle RC, Jr, Shields JA. Multifocal blue nevus of the conjunctiva. Surv Ophthalmol. 2008;53:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Demirci H, Shields CL, Shields JA, Eagle RC., Jr Malignant melanoma arising from unusual conjunctival blue nevus. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:1581–1584. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.11.1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eller AW, Bernardino VB., Jr Blue nevi of the conjunctiva. Ophthalmology. 1983;90:1469–1471. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(83)34359-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim JH, Lee MJ, Choung HK, Kim NJ, Hwang SW, Sung MS, Khwarg SI. Conjunctival cytologic features in anophthalmic patients wearing an ocular prosthesis. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;24:290–295. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181788dff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hendricks WM. Eruptive blue nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;4:50–53. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(81)70007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Navarini AA, Kolm I, Calvo X, Kamarashev J, Kerl K, Conrad C, French LE, Braun RP. Trauma as triggering factor for development of melanocytic nevi. Dermatology. 2010;220:291–296. doi: 10.1159/000276983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colson F, Arrese JE, Nikkels AF. Localized eruptive blue nevi after herpes zoster. Case Rep Dermatol. 2016;8:118–123. doi: 10.1159/000446178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]