Summary

Photosynthesis evolved in eukaryotes by the endosymbiosis of a cyanobacterium, the future plastid, within a heterotrophic host. This primary endosymbiosis occurred in the ancestor of Archaeplastida, a eukaryotic supergroup that includes glaucophytes, red algae, green algae and land plants [1–4]. However, while the endosymbiotic origin of plastids from a single cyanobacterial ancestor is firmly established, the nature of that ancestor remains controversial: plastids have been proposed to derive from either early- or late-branching cyanobacterial lineages [5–11]. To solve this issue, we carried out phylogenomic and super-network analyses of the most comprehensive dataset analyzed so far including plastid-encoded proteins and nucleus-encoded proteins of plastid origin resulting from endosymbiotic gene transfer (EGT) of primary photosynthetic eukaryotes, as well as wide-ranging genome data from cyanobacteria, including novel lineages. Our analyses strongly support that plastids evolved from deep-branching cyanobacteria and that the present-day closest cultured relative of primary plastids is Gloeomargarita lithophora. This species belongs to a recently discovered cyanobacterial lineage widespread in freshwater microbialites and microbial mats [12, 13]. The ecological distribution of this lineage sheds new light on the environmental conditions where the emergence of photosynthetic eukaryotes occurred, most likely in a terrestrial-freshwater setting. The fact that glaucophytes, the first archaeplastid lineage to diverge, are exclusively found in freshwater ecosystems reinforces this hypothesis. Therefore, plastids not only emerged early within cyanobacteria, but the first photosynthetic eukaryotes likely evolved in terrestrial-freshwater settings, not in oceans as commonly thought.

Results and Discussion

Phylogenomic Evidence for the Early Origin of Plastids Among Cyanobacteria

To address the question of whether plastids derive from an early- or late-branching cyanobacterium, we have carried out phylogenomic analyses upon a comprehensive dataset of conserved plastid-encoded proteins and the richest sampling of cyanobacterial genome sequences used to date. Plastids have highly reduced genomes (they encode only between 80 and 230 proteins) compared with free-living cyanobacterial genomes, which encode between 1,800 and 12,000 proteins [10]. Most genes remaining in these organelle’s genomes encode essential plastid functions (e.g., protein translation, photosystem structure) and their sequences are highly conserved. Therefore, despite plastid-encoded proteins are relatively few, they are good phylogenetic markers because they i) are direct remnants of the cyanobacterial endosymbiont and ii) exhibit remarkable sequence and functional conservation.

To have a broad and balanced representation of primary plastids and cyanobacterial groups in our analyses, we mined a large sequence database containing all ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs) and proteins encoded in 19 plastids of Archaeplastida (1 glaucophyte, 8 green algae/plants, and 9 red algae) and 122 cyanobacterial genomes, including recently sequenced members [7, 10, 14] and the genome of Gloeomargarita lithophora, sequenced for this work (see Experimental Procedures). Sequence similarity searches in this genome dataset allowed the identification of 97 widespread conserved proteins, after exclusion of those only present in a restricted number of plastids and/or cyanobacteria and those showing evidence of horizontal gene transfer (HGT) among cyanobacterial species (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures and supplemental dataset for more information). Preliminary phylogenetic analysis of the dataset of 97 conserved proteins by a supermatrix approach (21,942 concatenated amino acid sites) using probabilistic phylogenetic methods with a site-heterogeneous substitution model (CAT-GTR) retrieved a tree with a deep-branching position of the plastid sequences (Figure S1A). It was also noticeable in this tree the very long branch of the Synechococcus-Prochlorococcus (SynPro) cyanobacterial clade, which reflected its very high evolutionary rate. Since the SynPro cyanobacteria have never been found to be related to plastids, as confirmed by our own analysis, we decided to exclude them from subsequent analyses because of their accelerated evolutionary rate and because their sequences have a strong compositional bias known to induce errors in phylogenomic studies [8].

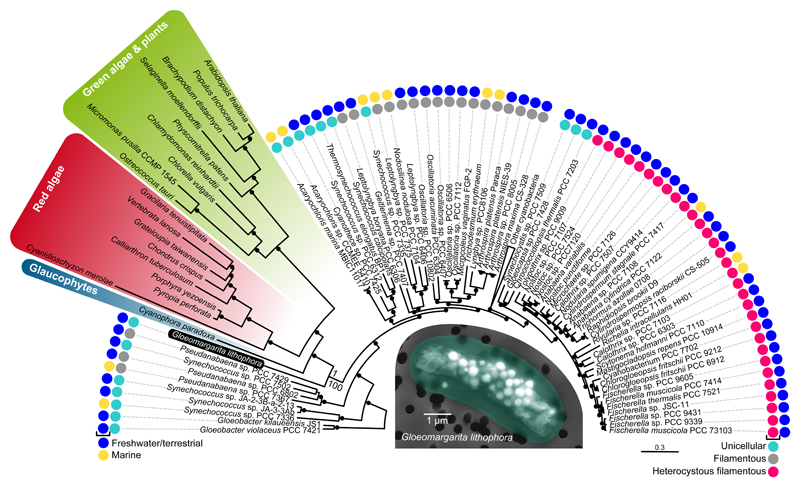

After removing the fast-evolving SynPro clade, we analyzed the dataset of 97 proteins as well as an rRNA dataset containing plastid and cyanobacterial 16S+23S rRNA concatenated sequences using maximum likelihood and Bayesian phylogenetic inference. Phylogenetic trees reconstructed for both datasets provide full support for the early divergence of plastids among the cyanobacterial species (Figures 1 and S1B, respectively). Moreover, our trees show that the closest present-day relative of plastids is the recently described deep-branching cyanobacterium Gloeomargarita lithophora [12, 13]. This biofilm-forming benthic cyanobacterium has attracted attention by its unusual capacity to accumulate intracellular amorphous calcium-magnesium-strontium-barium carbonates. Phylogenetic analysis based on environmental 16S rRNA sequences has shown that G. lithophora belongs to a diverse early-branching cyanobacterial lineage, the Gloeomargaritales [13], for which it is the only species isolated so far. Although initially found in an alkaline crater lake in Mexico, environmental studies have revealed that G. lithophora and related species have a widespread terrestrial distribution ranging from freshwater alkaline lakes to thermophilic microbial mats [13]. Interestingly, it has never been observed in marine samples [13].

Figure 1. The Position of Plastids in the Cyanobacterial Phylogeny.

This Bayesian phylogenetic tree is based on the concatenation of 97 plastid-encoded proteins and their cyanobacterial homologues. Branches supported by posterior probability 1 are labeled with black circles. Maximum likelihood bootstrap value is also indicated for the branch uniting plastids with the cyanobacterium Gloeomargarita lithophora. A false-colored scanning electron microscopy image of this cyanobacterium is shown in the center of the tree. Information about the habitat and morphology of the cyanobacterial species is provided. For the complete tree, see Figure S1.

During the long endosymbiotic history of plastids, many genes necessary for plastid function were transferred from the cyanobacterial endosymbiont into the host nuclear genome (endosymbiotic gene transfer: EGT [15]). In a previous work, we carried out an exhaustive search of EGT-derived proteins in Archaeplastida genomes with two strict criteria: 1- the proteins had to be present in more than one group of Archaeplastida, and 2- they had to be widespread in cyanobacteria and with no evidence of HGT among cyanobacterial lineages [16]. We have updated our EGT dataset with the new genome sequences available and retained 72 highly conserved proteins (see supplemental dataset) that we analyzed applying similar approaches to those used for the plastid-encoded proteins. Maximum likelihood and Bayesian inference phylogenetic analyses of the resulting 28,102 aa-long concatenation of these EGT proteins yield similar phylogenetic trees to those based on the plastid-encoded proteins: G. lithophora always branches as sister-group of the archaeplastid sequences with maximal statistical support (Figure S1C). Therefore, three different datasets (plastid encoded proteins, plastid rRNA genes, and EGT proteins encoded in the nucleus) converge to support the same result.

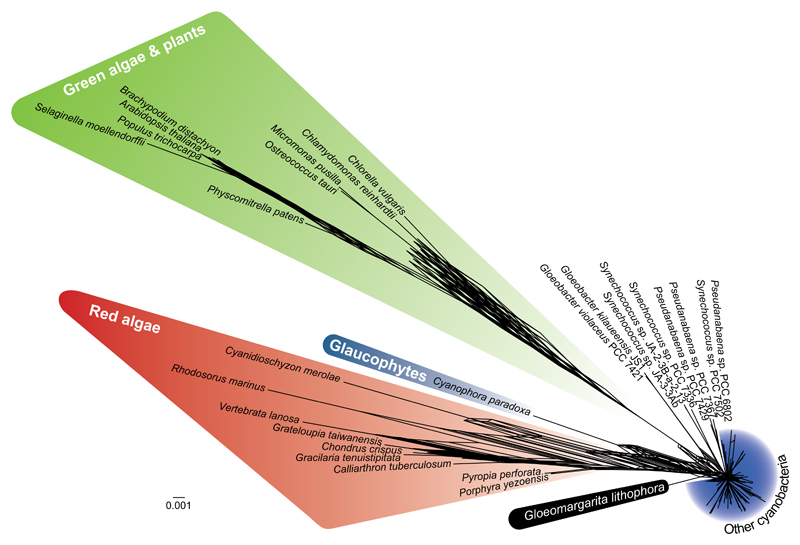

Robustness of the Evolutionary Relationship Between Gloeomargarita and Plastids

To test the robustness of the phylogenetic relation between Gloeomargarita and plastids, we investigated possible biases that might lead to an artefactual placement of plastids in our trees. We specifically focused on the dataset of plastid-encoded proteins, as these proteins are better conserved than the EGT proteins. Changes induced by the adaptation of endosymbiotically transferred genes to the new genetic environment (the eukaryotic nuclear genome) likely impacted the evolutionary rate of EGT proteins (notice the much longer distance between Gloeomargarita and archaeplastid sequences for the EGT protein dataset than for the plastid-encoded protein dataset, 20% longer in average, see Figures S1C and S1E). We first recoded the amino acid sequences by grouping amino acids of similar physicochemical characteristics into four families, a procedure which is known to alleviate possible compositional biases [17]. Phylogenetic trees based on the recoded alignment still retrieve the Gloeomargarita-plastids sister relation (Figure S1D). It has been shown that fast-evolving sites in plastids have a very poor fit to evolutionary models [18]. Therefore, we tested whether the Gloeomargarita-plastids relation could be due to the accumulation of fast-evolving sites leading to sequence evolution model violation and long-branch attraction (LBA) artefacts. For that, we calculated the evolutionary rate for each of the 21,942 sites of the 97-protein concatenation and divided them into 10 categories, from the slowest- to the fastest-evolving ones. We then reconstructed phylogenetic trees with a progressive inclusion of fast-evolving sites (the so-called Slow-Fast method, aimed at increasing the signal/noise ratio of sequence datasets [19]). All the trees show the Gloeomargarita-plastids sister relation with full statistical support (Figures S1E-S1M). Interestingly, the trees based on the slowest-evolving positions exhibit a remarkable reduction of the branch length of the plastid sequences (especially those of green algae and land plants; Figures S1K-S1M), which become increasingly longer with the addition of fast-evolving positions. This reflects the well-known acceleration of evolutionary rate that plastids have experienced, in particular in Viridiplantae [16]. These results argue against the possibility that the Gloeomargarita-plastids relation arises from an LBA artefact due to the accumulation of noise in fast-evolving sites. Finally, we tested if the supermatrix approach might have generated artefactual results due to the concatenation of markers with potentially incompatible evolutionary histories (because of HGT, hidden paralogy, etc.) that might have escaped our attention. We addressed this issue through the application of a phylogenetic network approach, which can cope with those contradictory histories [20], to analyze the set of 97 phylogenetic trees reconstructed with the individual proteins. The supernetwork based on those trees confirms again G. lithophora as the closest cyanobacterial relative of plastids (Figure 2), in agreement with the phylogenomic results (Figure 1).

Figure 2. Supernetwork Analysis of Plastid-Encoded Proteins and Cyanobacterial Homologues.

This phylogenetic supernetwork is based on the individual maximum likelihood trees of 97 plastid-encoded proteins. For a distance-based analysis of these individual proteins, see Figure S2.

A deep origin of plastids within the cyanobacterial phylogeny was inferred in past studies based on 16S rRNA gene sequences, plastid proteins, and nucleus-encoded proteins of plastid origin [5–8]. However, those studies did not retrieve any close relationship between plastids and any extant cyanobacterial lineage, a result that could be attributed either to lack of phylogenetic resolution or to incomplete taxonomic sampling [6]. Our results, after inclusion of the new species G. lithophora, clearly advocate for the latter and stress the importance of exploration of undersampled environments such as many freshwater and terrestrial ones. Nevertheless, some studies have alternatively proposed that plastids emerged from the apical part of the cyanobacterial tree, being closely related to late-branching filamentous (Nostocales and Stigonomatales) [9–11] or unicellular (Chroococcales) [21] N2-fixing cyanobacteria. However, in agreement with our results, it has been shown that those phylogenetic results can be explained by similarities in G+C content due to convergent nucleotide composition between plastids and late-branching cyanobacteria and that the use of codon recoding techniques suppresses the compositional bias and recovers a deep origin of plastids [8].

Studies supporting a late plastid origin did not rely on phylogenomic analyses only but also used other methods, such as quantifying the number and sequence similarity of proteins shared between Archaeplastida and different cyanobacterial species. They showed that the heterocyst-forming filamentous cyanobacterial genera Nostoc and Anabaena appear to possess the largest and most similar set of proteins possibly present in the plastid ancestor [9, 10]. However, these approaches have two important limitations: 1) the number of proteins is highly dependent on the genome size of the different cyanobacteria, which can vary by more than one order of magnitude [7]; and 2) it is well known that sequence similarity is a poor proxy for evolutionary relationships [22]. Indeed, if we apply a similar procedure on our set of sequences but include several plastid representatives in addition to cyanobacteria, we observe that individual plastids can have sequences apparently more similar to certain cyanobacterial homologues than to those of other plastids (Figure S2). If sequence similarity was a good indicator of evolutionary relationship, it would be difficult to deduce from those data that plastids are monophyletic as they do not always resemble other plastids more than cyanobacteria. Actually, plastid proteins, especially those that have been transferred to the nucleus [16], have evolved much faster than their cyanobacterial counterparts, such that sequences of one particular primary photosynthetic eukaryote can be more similar to short-branching cyanobacterial ones than to those of other distantly-related long-branching photosynthetic eukaryotes. Thus, similarity-based approaches have clear limitations and can lead to artefactual results. Phylogenomic analysis is therefore more suitable than crude sequence similarity or than single-gene phylogenies to study the cyanobacterial origin of plastids.

Metabolic Interactions and the Environmental Setting at the Origin of Plastids

Proponents of the recent origin of primary plastids from N2-fixing filamentous cyanobacteria suggest that the dearth of biologically available nitrogen during most of the Proterozoic and the ability of these organisms to fix nitrogen played a key role in the early establishment of the endosymbiosis [9, 10]. However, there is no trace of such past ability to fix nitrogen in modern plastids. Furthermore, this metabolic ability is also widespread in many cyanobacterial lineages, including basal-branching clades, which has led to propose that the cyanobacterial ancestor was able to fix nitrogen [23]. Therefore, if N2 fixation did actually play a role in the establishment of the plastid, it cannot discriminate in favor of a late- versus early-branching cyanobacterial endosymbiont. The closest modern relative of plastids, G. lithophora, lacks the genes necessary for N2 fixation, which further argues against the implication of this metabolism in the origin of plastids. N2 fixation is also absent in the cyanobacterial endosymbiont of Paulinella chromatophora, which is considered to be a recent second, independent case of primary plastid acquisition in eukaryotes [3, 4, 24]. Other hypotheses have proposed a symbiotic interaction between the cyanobacterial ancestor of plastids and its eukaryotic host based on the metabolism of storage polysaccharides. In that scenario, the cyanobacterium would have exported ADP-glucose in exchange for the import of reduced nitrogen from the host [25].

Although the nature of the metabolic exchanges between the two partners at the origin of primary photosynthetic eukaryotes remains to be elucidated, the exclusive distribution of the Gloeomargarita lineage in freshwater and terrestrial habitats [13] provides important clues about the type of ecosystem where the endosymbiosis of a Gloeomargarita-like cyanobacterium within a heterotrophic host took place. Like G. lithophora, and similar to most basal-branching cyanobacterial lineages, the first cyanobacteria most likely thrived in terrestrial/freshwater habitats [26, 27]. Consistent with this observation, the colonization of open oceans and the diversification of marine planktonic cyanobacteria, including the SynPro clade, occurred later on in evolutionary history, mainly during the Neoproterozoic (1000-541 Mya), with consequential effects on ocean and atmosphere oxygenation [27]. Notwithstanding their large error intervals, molecular clock analyses infer the origin of Archaeplastida during the mid-Proterozoic [28, 29], well before the estimated Neoproterozoic cyanobacterial colonization of oceans. Interestingly, Glaucophyta, the first lineage to diverge within the Archaeplastida (Figures 1 and S1) has been exclusively found in freshwater habitats [30], which is also the case for the most basal clade of red algae, the Cyanidiales, commonly associated to terrestrial thermophilic mats [31]. In contrast with the classical idea of a marine origin of eukaryotic alga, these data strongly support that plastids, and hence the first photosynthetic eukaryotes, arose in a freshwater/terrestrial environment [32]. This happened most likely on a Proterozoic Earth endowed with low atmospheric and oceanic oxygen concentrations [33].

Conclusions

We provide strong phylogenomic evidence from plastid and nucleus-encoded genes of cyanobacterial ancestry for a deep origin of plastids within the phylogenetic tree of Cyanobacteria, and find that the Gloeomargarita lineage represents the closest extant relative of the plastid ancestor. The ecological distribution of both, this cyanobacterial lineage and extant early-branching eukaryotic algae, suggests that the first photosynthetic eukaryotes evolved in a terrestrial environment, probably in freshwater biofilms or microbial mats. Microbial mats are complex communities where metabolic symbioses between different microbial types, including cyanobacteria and heterotrophic eukaryotes, are common. They imply physical and genetic interactions between mutualistic partners that may have well facilitated the plastid endosymbiosis. In that sense, it will be of especial interest to study the interactions that the cyanobacterial species of the Gloeomargarita lineage establish with other microorganisms looking for potential symbioses with heterotrophic protists. Our work highlights the importance of environmental exploration to characterize new organisms that can, in turn, be crucial to resolve unsettled evolutionary questions.

Experimental Procedures

Selection of Phylogenetic Markers

We created a local genome database with 692 completely sequenced prokaryotic and eukaryotic genomes, complemented with Expressed Sequenced Tags (EST) from 8 photosynthetic eukaryotes, all downloaded from GenBank. In particular, the database included 122 cyanobacteria and 20 plastids of primary photosynthetic eukaryotes (primary plastids, found in Archaeplastida). Among the cyanobacteria, we added the genome sequence of Gloeomargarita lithophora strain CCAP 1437/1 (accession number NZ_CP017675; see Supplemental Experimental Procedures). To retrieve plastid-encoded proteins and their cyanobacterial orthologues, we used the 149 proteins encoded in the gene-rich plastid of the glaucophyte Cyanophora paradoxa as queries in BLASTP [34] searches against this local database. Plastid and cyanobacterial protein sequences recovered among the top 300 hits with a cut off E-value < 10-10 were retrieved and aligned to reconstruct preliminary maximum-likelihood (ML) single-protein phylogenetic trees (details can be found in Supplemental Experimental Procedures). These trees were visually inspected to identify potentially paralogous proteins or HGT among cyanobacteria (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures). The problematic proteins detected were discarded. Among the remained proteins, we selected those present in at least two of the three Archaeplastida lineages (glaucophytes, red algae, and green algae and plants; if absent in one lineage they were replaced by missing data). Thereby, our final dataset comprised 97 plastid-encoded proteins (see supplemental dataset). In addition, we updated the dataset of EGT proteins previously published by Deschamps and Moreira [16], including sequences from new available genomes. As in the previous case, ML single-protein phylogenetic trees were reconstructed and inspected to discard proteins with paralogs and HGT cases. All datasets are available at http://www.ese.u-psud.fr/article909.html?lang=en.

Phylogenetic Analyses

Maximum Likelihood trees of individual markers were reconstructed using PhyML [35] with the GTR model for rRNA gene sequences and the LG model for protein sequences, in both cases with a 4 substitution rate categories gamma distribution and estimation of invariable sites from the alignments. Branch lengths, tree topology and substitution rate parameters were optimized by PhyML. Bootstrap values were calculated with 100 pseudoreplicates. Individual ML trees were used to reconstruct a supernetwork [20] with the program Splitstree [36] with default parameters.

Tree reconstruction of concatenated protein datasets under Bayesian inference was carried out using two independent chains in PhyloBayes-MPI [37] with the CAT-GTR model and a 4 categories gamma distribution. Sequences were also recoded into four amino acid families [17] using a Python script and analyzed with PhyloBayes-MPI in the same way. Chain convergence was monitored by the maxdiff parameter (chains were run until maxdiff<0.1).

The Slow-Fast method was applied using the program SlowFaster [38] to produce 10 alignments with an increasing proportion of fast-evolving sites included. These alignments were used for phylogenetic reconstruction using PhyloBayes-MPI as with the complete concatenation.

Estimation of Protein Sequence Distances and Heatmap Construction

Distances among protein sequences were calculated using two different approaches: 1- Measuring patristic distances between taxa in phylogenetic trees, and 2- from pairwise comparisons of aligned protein sequences. Patristic distances are the sum of the lengths of the branches that connect two taxa in a phylogenetic tree and can account for multiple substitutions events to a certain level. We used the glaucophyte C. paradoxa as reference as it has the shortest branch among the plastid sequences and measured the patristic distances between this taxon and the other taxa (cyanobacterial species and plastids of red algae and Viridiplantae) on the ML trees of the 97 individual plastid-encoded proteins reconstructed as previously described. Protdist [39] was used to estimate pairwise distances between the plastid proteins of C. paradoxa and the proteins of the rest of taxa. Patristic distances and sequence similarities were displayed as heatmaps using the library Matplotlib [40].

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Information includes Supplemental Experimental Procedures, two figures, and one supplemental dataset and can be found with this article online at http://xxxxxx.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by European Research Council grants ProtistWorld (P.L.-G., Grant Agreement no. 322669) and CALCYAN (K.B., Grant Agreement no. 307110) under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Program and the RTP CNRS Génomique Environnementale project MetaStrom (D.M.).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

D.M., P.L.-G. and K.B. characterized Gloeomargarita lithophora. K.B. performed electron microscopy. Y.Z. carried out genome annotation. R.P.T, P.D. and D.M. performed phylogenetic analyses. R.P.T, D.M, P.D. and P.L.-G. wrote the manuscript with input from all co-authors.

References

- 1.Moreira D, Le Guyader H, Philippe H. The origin of red algae and the evolution of chloroplasts. Nature. 2000;405:69–72. doi: 10.1038/35011054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodríguez-Ezpeleta N, Brinkmann H, Burey SC, Roure B, Burger G, Loffelhardt W, Bohnert HJ, Philippe H, Lang BF. Monophyly of primary photosynthetic eukaryotes: green plants, red algae, and glaucophytes. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1325–1330. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Archibald JM. The puzzle of plastid evolution. Curr Biol. 2009;19:R81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.11.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keeling PJ. The number, speed, and impact of plastid endosymbioses in eukaryotic evolution. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2013;64:583–607. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050312-120144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turner S, Pryer KM, Miao VP, Palmer JD. Investigating deep phylogenetic relationships among cyanobacteria and plastids by small subunit rRNA sequence analysis. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1999;46:327–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1999.tb04612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Criscuolo A, Gribaldo S. Large-scale phylogenomic analyses indicate a deep origin of primary plastids within cyanobacteria. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:3019–3032. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shih PM, Wu D, Latifi A, Axen SD, Fewer DP, Talla E, Calteau A, Cai F, Tandeau de Marsac N, Rippka R, et al. Improving the coverage of the cyanobacterial phylum using diversity-driven genome sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:1053–1058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217107110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li B, Lopes JS, Foster PG, Embley TM, Cox CJ. Compositional biases among synonymous substitutions cause conflict between gene and protein trees for plastid origins. Mol Biol Evol. 2014;31:1697–1709. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deusch O, Landan G, Roettger M, Gruenheit N, Kowallik KV, Allen JF, Martin W, Dagan T. Genes of cyanobacterial origin in plant nuclear genomes point to a heterocyst-forming plastid ancestor. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25:748–761. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dagan T, Roettger M, Stucken K, Landan G, Koch R, Major P, Gould SB, Goremykin VV, Rippka R, Tandeau de Marsac N, et al. Genomes of Stigonematalean cyanobacteria (subsection V) and the evolution of oxygenic photosynthesis from prokaryotes to plastids. Genome Biol Evol. 2013;5:31–44. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evs117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ochoa de Alda JA, Esteban R, Diago ML, Houmard J. The plastid ancestor originated among one of the major cyanobacterial lineages. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4937. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Couradeau E, Benzerara K, Gerard E, Moreira D, Bernard S, Brown GE, Jr, Lopez-Garcia P. An early-branching microbialite cyanobacterium forms intracellular carbonates. Science. 2012;336:459–462. doi: 10.1126/science.1216171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ragon M, Benzerara K, Moreira D, Tavera R, López-García P. 16S rDNA-based analysis reveals cosmopolitan occurrence but limited diversity of two cyanobacterial lineages with contrasted patterns of intracellular carbonate mineralization. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:331. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benzerara K, Skouri-Panet F, Li J, Ferard C, Gugger M, Laurent T, Couradeau E, Ragon M, Cosmidis J, Menguy N, et al. Intracellular Ca-carbonate biomineralization is widespread in cyanobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:10933–10938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403510111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin W, Stoebe B, Goremykin V, Hapsmann S, Hasegawa M, Kowallik KV. Gene transfer to the nucleus and the evolution of chloroplasts. Nature. 1998;393:162–165. doi: 10.1038/30234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deschamps P, Moreira D. Signal conflicts in the phylogeny of the primary photosynthetic eukaryotes. Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26:2745–2753. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodríguez-Ezpeleta N, Brinkmann H, Roure B, Lartillot N, Lang BF, Philippe H. Detecting and overcoming systematic errors in genome-scale phylogenies. Syst Biol. 2007;56:389–399. doi: 10.1080/10635150701397643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun L, Fang L, Zhang Z, Chang X, Penny D, Zhong B. Chloroplast phylogenomic inference of green algae relationships. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20528. doi: 10.1038/srep20528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Philippe H, Lopez P, Brinkmann H, Budin K, Germot A, Laurent J, Moreira D, Muller M, Le Guyader H. Early-branching or fast-evolving eukaryotes? An answer based on slowly evolving positions. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2000;267:1213–1221. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huson DH, Bryant D. Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:254–267. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Falcon LI, Magallon S, Castillo A. Dating the cyanobacterial ancestor of the chloroplast. Isme J. 2010;4:777–783. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koski LB, Golding GB. The closest BLAST hit is often not the nearest neighbor. J Mol Evol. 2001;52:540–542. doi: 10.1007/s002390010184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Latysheva N, Junker VL, Palmer WJ, Codd GA, Barker D. The evolution of nitrogen fixation in cyanobacteria. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:603–606. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nowack EC, Melkonian M, Glockner G. Chromatophore genome sequence of Paulinella sheds light on acquisition of photosynthesis by eukaryotes. Curr Biol. 2008;18:410–418. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deschamps P, Colleoni C, Nakamura Y, Suzuki E, Putaux JL, Buleon A, Haebel S, Ritte G, Steup M, Falcon LI, et al. Metabolic symbiosis and the birth of the plant kingdom. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25:536–548. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Battistuzzi FU, Hedges SB. A major clade of prokaryotes with ancient adaptations to life on land. Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26:335–343. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanchez-Baracaldo P. Origin of marine planktonic cyanobacteria. Sci Rep. 2015;5 doi: 10.1038/srep17418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parfrey LW, Lahr DJ, Knoll AH, Katz LA. Estimating the timing of early eukaryotic diversification with multigene molecular clocks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:13624–13629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110633108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eme L, Sharpe SC, Brown MW, Roger AJ. On the age of eukaryotes: evaluating evidence from fossils and molecular clocks. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;6:8. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kies L, Kremer BP. Phylum Glaucocystophyta. In: Margulis L, Corliss JO, Melkonian M, Chapman DJ, editors. Handbook of protoctista. Boston, MA: Jones and Barlett; 1990. pp. 152–166. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoon HS, Müller KM, Sheath RG, Ott FD, Bhattacharya D. Defining the major lineages of red algae (Rhodophyta) J Phycol. 2006;42:482–492. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blank CE. Origin and early evolution of photosynthetic eukaryotes in freshwater environments: reinterpreting proterozoic paleobiology and biogeochemical processes in light of trait evolution. J Phycol. 2013;49:1040–1455. doi: 10.1111/jpy.12111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lyons TW, Reinhard CT, Planavsky NJ. The rise of oxygen in Earth's early ocean and atmosphere. Nature. 2014;506:307–315. doi: 10.1038/nature13068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guindon S, Gascuel O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol. 2003;52:696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huson DH. SplitsTree: analyzing and visualizing evolutionary data. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:68–73. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lartillot N, Rodrigue N, Stubbs D, Richer J. PhyloBayes MPI: phylogenetic reconstruction with infinite mixtures of profiles in a parallel environment. Syst Biol. 2013;62:611–615. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syt022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kostka M, Uzlikova M, Cepicka I, Flegr J. SlowFaster, a user-friendly program for slow-fast analysis and its application on phylogeny of Blastocystis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:341. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP - Phylogeny Inference Package. 3.6 Edition. Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hunter J. Matplotlib: A 2d graphics environment. Computing Science & Engineer. 2007;9:90–95. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.