Abstract

Parasitic nematodes infect over 1 billion people worldwide and cause some of the most common neglected tropical diseases. Despite their prevalence, our understanding of the biology of parasitic nematodes has been limited by the lack of tools for genetic intervention. In particular, it has not yet been possible to generate targeted gene disruptions and mutant phenotypes in any parasitic nematode. Here, we report the development of a method for introducing CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene disruptions in the human-parasitic threadworm Strongyloides stercoralis. We disrupted the S. stercoralis twitchin gene unc-22, resulting in nematodes with severe motility defects. Ss-unc-22 mutations were resolved by homology-directed repair when a repair template was provided. Omission of a repair template resulted in deletions at the target locus. Ss-unc-22 mutations were heritable; we passed Ss-unc-22 mutants through a host and successfully recovered mutant progeny. Using a similar approach, we also disrupted the unc-22 gene of the rat-parasitic nematode Strongyloides ratti. Our results demonstrate the applicability of CRISPR-Cas9 to parasitic nematodes, and thereby enable future studies of gene function in these medically relevant but previously genetically intractable parasites.

Author summary

Parasitic worms are a widespread public health burden, yet very little is known about the cellular and molecular mechanisms that contribute to their parasitic lifestyle. One of the major barriers to better understanding these mechanisms is that there are currently no available methods for making targeted gene knockouts in any parasitic worm species. Here, we describe the first mutant phenotype in a parasitic worm resulting from a targeted gene disruption. We applied CRISPR-Cas9-mediated mutagenesis to parasitic worms in the genus Strongyloides and developed a method that overcomes many of the challenges that have previously inhibited generating mutant parasitic worms. We characterize heritable mutant phenotypes and outline a toolkit that will be applicable to many other genes with potential roles in parasitism. Importantly, we developed our method for gene knockouts in a human-parasitic worm. By directly investigating the genes and molecular pathways that enable worms to parasitize humans, we may be able to develop novel anthelmintic therapies or other measures for preventing nematode infections.

Introduction

Human-parasitic nematodes cause an annual disease burden of over 5 million disability adjusted life years (DALYs) [1,2]. Current drugs used to treat nematode infections are inadequate to eliminate this disease burden: reinfection rates are high in endemic areas and resistance to the few available anthelmintic drugs is a growing concern [2]. However, the development of new strategies for combating nematode infections has been severely limited by the lack of a method for gene disruption in parasitic nematodes [3]. While gene knockdowns by RNAi have been achieved in a few species, RNAi shows variable efficacy and has been used successfully for only a few genes [3]. Conversely, chemical mutagenesis screens have been used to generate mutant phenotypes but the causative mutations could not be identified [4]. As a result, the molecular mechanisms that drive development, behavior, and infectivity in parasitic nematodes remain poorly understood.

The clustered, regularly interspaced, short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated nuclease Cas9 system [5], which evolved from an immune defense system in bacteria and archaea, has been used for targeted mutagenesis in both model and non-model organisms [6,7]. In this system, Cas9 creates double-strand breaks (DSBs) at the genomic location determined by two small RNAs: a CRISPR RNA (crRNA) complementary to the target site and a trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA). The crRNA and tracrRNA are often synthetically combined into a single guide RNA (sgRNA) [5]. The DSBs are then most commonly repaired through either non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR) pathways, but alternative repair mechanisms have been reported in some cases [8]. Despite its application to a wide range of organisms, the CRISPR-Cas9 system has not been successfully utilized in parasitic nematodes. Reasons for this include the low tolerance of parasitic nematodes for exogenous DNA or protein, the labor-intensiveness and low efficiency of methods for delivering constructs for gene targeting, the need to propagate most parasitic nematodes inside an animal host, and the inaccessibility of host-dwelling life stages to genetic intervention [3].

The human-parasitic threadworm Strongyloides stercoralis is a powerful model system for mechanistic studies of parasitic nematode biology. S. stercoralis is a skin-penetrating intestinal nematode that infects approximately 100 million people worldwide; it can cause chronic gastrointestinal distress in healthy individuals but can be fatal for immunosuppressed individuals [9]. S. stercoralis and closely related species are unique among parasitic nematodes in that they can develop through a single free-living generation outside the host (Fig 1A) [10]. The free-living adults are amenable to transgenesis techniques adapted from the model nematode Caenorhabditis elegans [3,11], suggesting they may also be amenable to CRISPR-Cas9-mediated mutagenesis. Preliminary evidence that CRISPR-Cas9 can be used for gene disruptions in S. stercoralis was reported; however, DNA mutations were detected only at extremely low frequency in pooled populations of worms and individual worms with mutant phenotypes were not observed [11]. Thus, whether CRISPR-Cas9 can be used to study gene function in S. stercoralis was unclear.

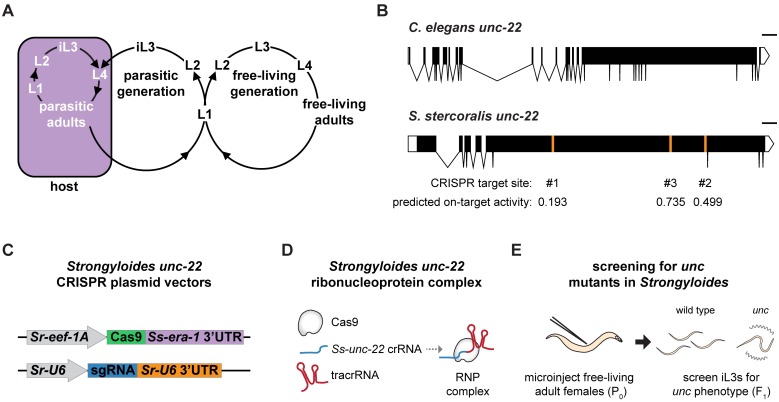

Fig 1. A strategy for targeted mutagenesis in S. stercoralis using CRISPR-Cas9.

(A) The life cycle of S. stercoralis. iL3s enter hosts by skin penetration. The nematodes then develop into parasitic adults, which reside and reproduce in the small intestine. Their progeny exit the host in feces and develop into either iL3s or free-living adults. The free-living adults mate and reproduce in the environment, and all of their progeny develop into iL3s. Thus, S. stercoralis can develop through a single generation outside the host [10]. S. stercoralis can also complete its life cycle within a single host [9]. L1-L4 = 1st-4th larval stages. Adapted from Gang and Hallem, 2016 [10]. (B) The unc-22 genes of C. elegans and S. stercoralis. The Ss-unc-22 gene structure depicted is based on the gene prediction from WormBase ParaSite [24,47]. The CRISPR target sites tested and their predicted on-target activity scores are indicated [50]. Scale bar = 1 kb. (C) Plasmid vectors for the expression of Cas9 and sgRNA in S. stercoralis. (D) RNP complex assembly. Cas9 protein, crRNA targeting Ss-unc-22, and tracrRNA are incubated in vitro to form RNP complexes [20]. (E) Strategy for targeted mutagenesis in S. stercoralis. Plasmid vectors or RNP complexes were introduced into developing eggs by gonadal microinjection of free-living adult females. F1 iL3 progeny were screened for unc phenotypes, putatively resulting from mutation of Ss-unc-22.

Here we report the use of CRISPR-Cas9 to create loss-of-function DNA mutations and mutant phenotypes in S. stercoralis. We targeted the S. stercoralis twitchin gene unc-22, and subsequently isolated mutant nematodes with uncoordinated (unc) phenotypes characterized by decreased motility, sporadic spontaneous twitching, and persistent twitching when exposed to an acetylcholine receptor agonist. We found that CRISPR-Cas9-induced DSBs at Ss-unc-22 are resolved by HDR when an appropriate repair template is provided. In the absence of an HDR template we found no evidence for small insertions or deletions (indels) at the target sites tested, but instead observed putative deletions of >500 base pairs at the target locus. We optimized CRISPR-Cas9 targeting conditions for S. stercoralis, and then demonstrated that Ss-unc-22 mutations are heritable by passing mutant F1 progeny through a host and collecting F2 or F3 nematodes with unc phenotypes. Our results pave the way for mechanistic studies of gene function in parasitic nematodes, which may enable the development of novel targeted therapies to improve human-parasitic nematode control.

Results

CRISPR-Cas9 targeting of Ss-unc-22 causes an uncoordinated phenotype

To assess the functionality of CRISPR-Cas9-mediated mutagenesis in S. stercoralis, we focused on targeting the S. stercoralis ortholog of the C. elegans unc-22 gene. Ce-unc-22 encodes twitchin, a large intracellular muscle protein homologous to mammalian connectin [12,13]. We selected Ss-unc-22 because Ce-unc-22 has been successfully mutagenized by multiple methods, including CRISPR-Cas9 [14–17]. In addition, disruption of Ce-unc-22 results in an easily identifiable unc phenotype in both heterozygotes and homozygotes, with mutant nematodes showing dramatically impaired motility and intermittent body twitching [13]. We reasoned that the dominant phenotype resulting from loss of Ss-unc-22 would enable us to easily identify mutagenized S. stercoralis in the F1 generation even at low mutation frequencies. We introduced Strongyloides-specific CRISPR-Cas9 components targeting Ss-unc-22 into the syncytial gonad of S. stercoralis free-living adult females (Fig 1A) [11,18]. We identified and tested three CRISPR target sites designed to target Cas9 to the largest exon of Ss-unc-22 (Fig 1B). CRISPR-Cas9 constructs were delivered into S. stercoralis adults using two approaches. First, we utilized plasmid vectors to express Strongyloides-codon-optimized Cas9 and an sgRNA targeting Ss-unc-22. Cas9 was expressed under the control of the promoter for the putative Strongyloides elongation factor 1-alpha gene eef-1A. C. elegans eef-1A expresses in the germline, so it was predicted that germline expression would be conserved for Strongyloides eef-1A [19]. Expression of the sgRNA was driven by the putative Strongyloides U6 promoter (Fig 1C). Second, we targeted Ss-unc-22 using a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex consisting of in vitro-assembled recombinant Cas9 protein, crRNA targeting Ss-unc-22, and tracrRNA (Fig 1D) [20]. We delivered CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid vectors or RNP complexes into free-living adult females, mated microinjected females with wild-type free-living males, and screened for unc phenotypes in F1 progeny at the infective third-larval stage (iL3) (Fig 1A and 1E).

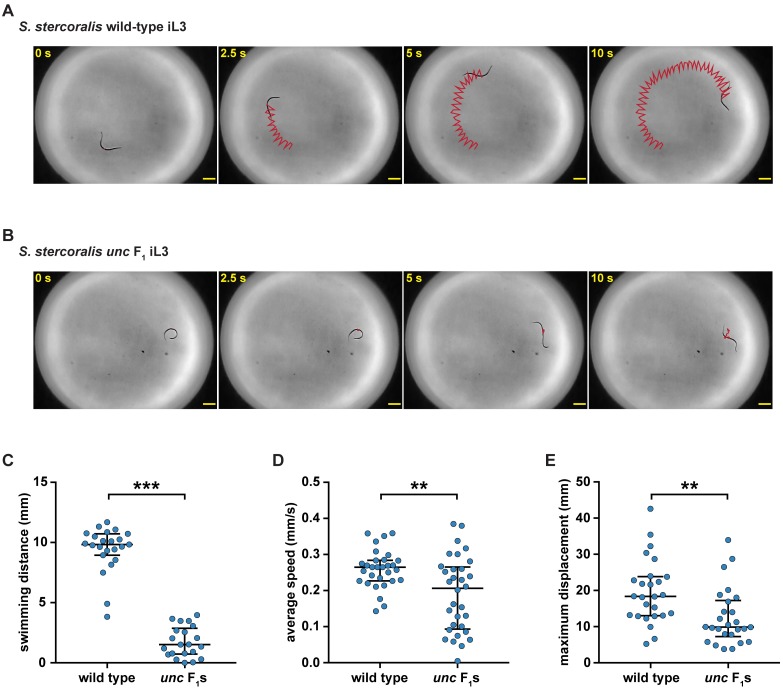

Following injection of Ss-unc-22 CRISPR-Cas9 components into free-living adult females, we collected a distinct population of F1 iL3s with a striking uncoordinated phenotype (hereafter referred to as unc F1 iL3s) that was similar to the phenotype observed in C. elegans unc-22 nematodes. unc F1 iL3s showed impaired swimming behavior when compared to wild-type iL3s collected from non-injected controls (Fig 2A–2C, S1 and S2 Videos). Quantification of iL3 movement using automated tracking software [21] revealed that unc F1 iL3s showed reduced crawling speeds relative to wild-type iL3s (Fig 2D, S3 and S4 Videos). We then tracked the trajectories of wild-type vs. unc F1 iL3s over a 5-minute period and found that unc F1 iL3s traversed significantly less distance than wild-type iL3s (Fig 2E). The swimming and crawling phenotypes of unc F1 iL3s collected from injections were reminiscent of C. elegans unc phenotypes and suggested that we had successfully utilized CRISPR-Cas9 to disrupt Ss-unc-22.

Fig 2. CRISPR-Cas9 targeting of the Ss-unc-22 gene results in iL3s with an uncoordinated phenotype.

(A-B) Time-lapse images of wild-type iL3s (A) vs. unc F1 iL3s (B) swimming in a water droplet. Wild-type iL3s showed continuous rapid movement in water; unc F1 iL3s experienced intermittent bouts of twitching, paralysis, and uncoordinated movement. For A and B, red lines indicate iL3 trajectories. Scale bars = 200 μm. (C) Swimming distance for wild-type iL3s vs. unc F1 iL3s over a 10-s period. unc F1 iL3s swam shorter distances relative to wild-type iL3s. ***P<0.001, Mann-Whitney test. n = 21–23 trials for each population. (D) Average crawling speed for wild-type iL3s vs. unc F1 iL3s over a 20-s period. unc F1 iL3s showed reduced crawling speeds relative to wild-type iL3s. **P<0.01, unpaired t test with Welch’s correction. n = 30–32 trials for each population. (E) Maximum crawling displacement for wild-type iL3s vs. unc F1 iL3s over a 5-min period. unc F1 iL3s traversed less distance than wild-type iL3s. **P<0.01, Mann-Whitney test. n = 26 trials for each population. For C-E, graphs show medians and interquartile ranges. unc F1 iL3 data for B-E were obtained from plasmid vector delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 constructs at Ss-unc-22 site #1.

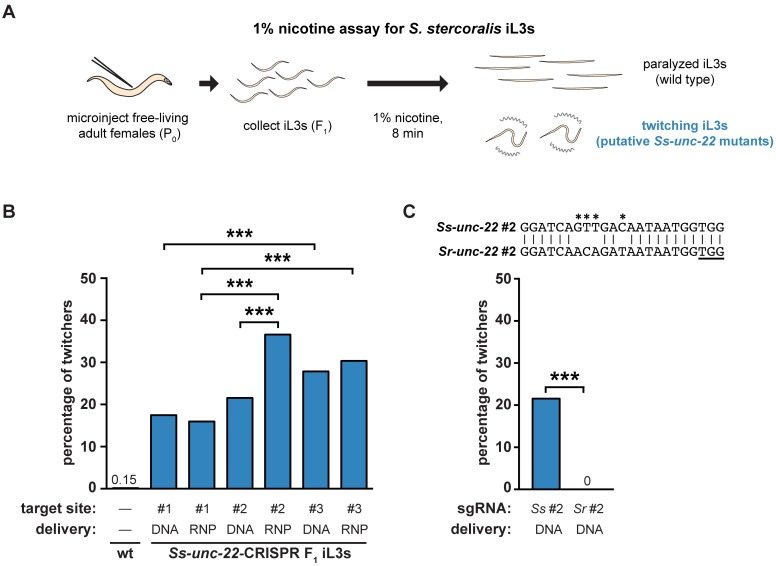

The CRISPR-Cas9-induced unc phenotype is exacerbated by nicotine exposure

In C. elegans, the twitching phenotype of Ce-unc-22 mutants is enhanced by exposure to acetylcholine receptor agonists such as nicotine [13]. We asked if F1 iL3s collected following CRISPR-Cas9 injections showed a similar nicotine-induced twitching phenotype. To test this, we developed a nicotine assay for S. stercoralis iL3s (Fig 3A) and validated it by quantifying twitching behavior in wild-type and unc-22 C. elegans adults and dauers. We examined dauers as well as adults because the C. elegans dauer larval stage is a developmentally arrested life stage that is analogous to the parasitic iL3 [22]. Wild-type C. elegans adults and dauers were completely paralyzed after 8 minutes of nicotine exposure, while Ce-unc-22 mutants showed severe twitching (S1 Fig). We observed a similar effect in S. stercoralis iL3s: nicotine induced paralysis in wild-type iL3s but caused nearly continuous twitching in some F1 iL3s collected from CRISPR-Cas9 injections (S5 and S6 Videos).

Fig 3. Nicotine induces twitching in unc F1 iL3s.

(A) A nicotine assay for S. stercoralis iL3s. Free-living adult females were injected with CRISPR constructs targeting Ss-unc-22. F1 iL3s were collected and exposed to 1% nicotine. Wild-type iL3s gradually paralyzed over the course of 8 min, whereas unc F1 iL3s twitched continuously. Some, but not all, of the F1 iL3s contained putative Ss-unc-22 mutations and twitched in nicotine. (B) Twitching frequency of S. stercoralis wild-type iL3s and the F1 iL3s from microinjected females following nicotine exposure. For each condition, the Ss-unc-22 target site and delivery method of the CRISPR-Cas9 constructs are indicated. DNA = plasmid vector delivery; RNP = ribonucleoprotein complex delivery. The twitching frequency of F1 iL3s for all Ss-unc-22 target sites and delivery methods tested differed from that of wild-type iL3s (P<0.001, chi-square test with Bonferroni correction). Instances where twitching frequency differed between target sites or delivery methods are indicated. ***P<0.001, chi-square test with Bonferroni correction. n = 446–1,314 iL3s per condition. (C) CRISPR-Cas9-mediated mutagenesis of Ss-unc-22 requires a highly specific sgRNA. Plasmid vectors for the expression of Cas9 and a sgRNA targeting S. ratti site #2 were injected into S. stercoralis. The twitching phenotype in S. stercoralis F1 iL3s was not observed when the S. ratti version of site #2 was used. ***P<0.001, Fisher’s exact test. n = 484-677 iL3s for each condition. The alignment of S. stercoralis and S. ratti site #2 is shown with the PAM underlined. Asterisks indicate nucleotide differences between the S. stercoralis and S. ratti targets.

We then used the distinct nicotine-twitching phenotype to assess the efficacy of different Ss-unc-22 target sites and CRISPR-Cas9 delivery methods. We tested three different CRISPR target sites (Fig 1B) using either plasmid vector or RNP complex delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 components (Fig 1C and 1D). We found that all three target sites, and both CRISPR delivery methods, yielded a population of twitching F1 iL3s, and we observed increasing twitching frequency corresponding to increasing predicted on-target activity for each site (Fig 3B, S1 Table). Only site #2 showed a significant difference between plasmid vector and RNP complex delivery, with RNP complex delivery generating a higher frequency of twitching iL3s than plasmid vector delivery (Fig 3B, S1 Table). Overall, we observed a twitching phenotype in ~16–37% of the F1 progeny depending on the target-site/delivery-method combination used (S1 Table). Thus, both plasmid vector and RNP delivery methods can be used for CRISPR-Cas9-mediated targeted mutagenesis in S. stercoralis to similar effect. Importantly, our results show that unc F1 iL3s (resulting from putative Ss-unc-22 mutations) can be generated at high efficiency in S. stercoralis by injecting a moderate number of P0 females (S1 Table). Only one free-living generation is accessible for analysis before host infection is required to continue the life cycle. As a result, high efficiency of CRISPR-Cas9 editing in the F1 is critical for either immediate investigation of first-generation mutants, or collection of sufficient numbers of mutant progeny to passage through a host and successfully generate a stable mutant line.

We also tested CRISPR-Cas9 activity in Strongyloides ratti, a parasite of rats, using the same method outlined for S. stercoralis. Like S. stercoralis, S. ratti can complete a free-living generation outside the host and is amenable to transgenesis [3,11]. We tested two different CRISPR target sites for Sr-unc-22 using plasmid vector delivery and screened F1 iL3s in nicotine (S2A Fig). We found that both target sites yielded a population of twitching F1 iL3s, and the nicotine-twitching frequency increased with predicted on-target activity (S2B Fig, S2 Table). The S. ratti nicotine-twitching phenotype was similar in severity to the phenotype observed in S. stercoralis. However, the twitching frequency was much lower in S. ratti than S. stercoralis, with only ~2–7% of F1 progeny displaying the twitching phenotype when injecting a similar number of P0 females (S2 Table). Our results demonstrate that CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis is applicable in both S. stercoralis and S. ratti, two important laboratory models for skin-penetrating parasitic nematode infections [23].

The genomes of S. stercoralis and S. ratti are very similar; their unc-22 genes share >91% sequence identity [24]. The CRISPR target sequences for Ss-unc-22 site #2 and Sr-unc-22 site #2 differ by only four base pairs (Fig 3C). We asked whether CRISPR-Cas9 targeting was species-specific by injecting the plasmid vectors encoding Cas9 and the sgRNA for S. ratti site #2 into S. stercoralis. We found no evidence for twitching F1 iL3s when the S. ratti version of the sgRNA was used (Fig 3C). Thus, CRISPR-Cas9-mediated mutagenesis of Ss-unc-22 appears to require highly specific sgRNAs.

CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis causes putative deletion of the Ss-unc-22 target locus

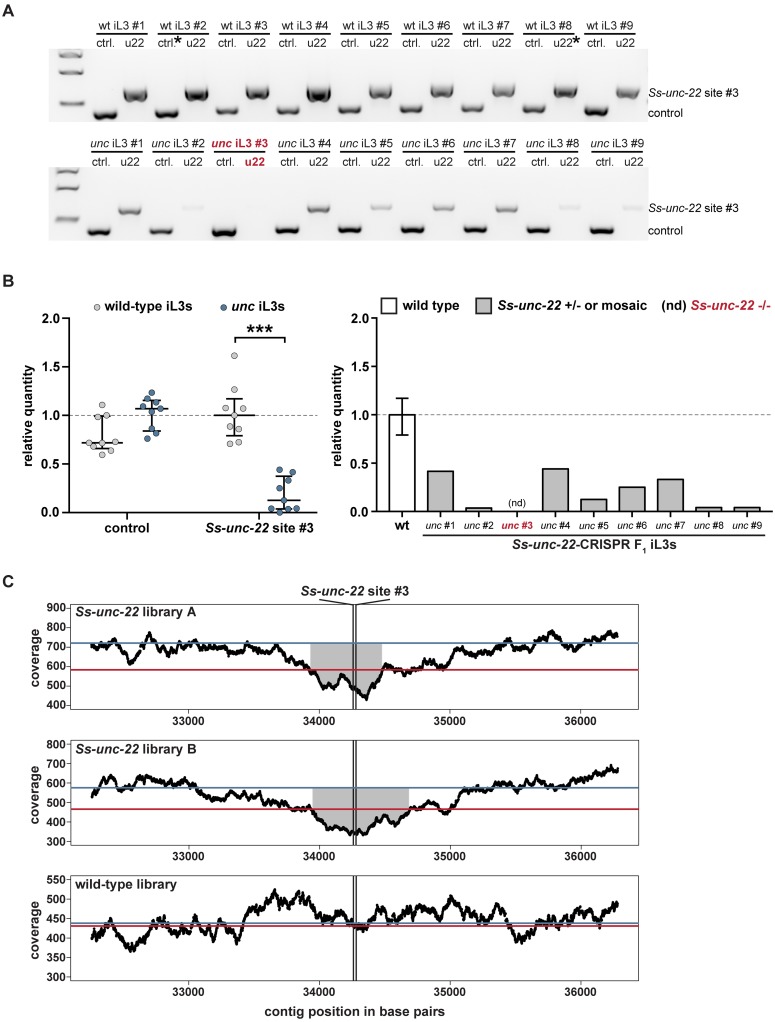

Most eukaryotes efficiently repair CRISPR-Cas9-induced DSBs through the NHEJ pathway [5–7,19,25]. NHEJ repair is error-prone and generally introduces small indels near the CRISPR cut site [5]. We asked if the unc F1 iL3 motility and nicotine-twitching phenotypes observed for S. stercoralis resulted from CRISPR-Cas9-induced indels at Ss-unc-22. For each Ss-unc-22 target site tested, we collected unc F1 iL3s that twitched in nicotine (suggesting mutations to Ss-unc-22), PCR-amplified the region around the target, and genotyped for indels. Surprisingly, we were unable to detect indels at any of the three Ss-unc-22 target sites tested. We attempted to identify indels through Sanger sequencing of the target region, heteroduplexed DNA detection by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) [26], T7E1 endonuclease activity [27], and TIDE (Tracking of Indels by sequence DEcomposition) [28]. For all of the indel detection methods tested, we only observed Ss-unc-22 wild-type sequence. However, when genotyping individual iL3s, we could reproducibly PCR-amplify the Ss-unc-22 target region from wild-type iL3s but noted inconsistency in our ability to amplify the Ss-unc-22 target region from unc F1 iL3s (Fig 4A). Using control primers, we could however successfully amplify another location in the genome from the same unc F1 iL3s where the Ss-unc-22 target region amplified poorly (Fig 4A). Thus, PCR variability was specific to unc F1 iL3s at the Ss-unc-22 target region (Fig 4B). Based on the lack of detectable indels in unc F1 iL3s, we hypothesized that the observed PCR variability at the Ss-unc-22 target region likely resulted from CRISPR-Cas9-induced deletions that eliminated one, or both, of the primer binding sites. Given that the C. elegans unc phenotype is dominant [12,13], unc F1 iL3s where the wild-type band was present are likely heterozygous, or mosaic, deletions of the Ss-unc-22 target region. unc F1 iL3s where the band was absent are putative homozygous deletions of Ss-unc-22 (Fig 4B). We observed putative homozygous deletions for Ss-unc-22 sites #2 and #3, the more efficient targets, but not Ss-unc-22 site #1 (S3 Table).

Fig 4. CRISPR-mediated mutagenesis of Ss-unc-22 results in putative deletion of the target locus.

(A) Representative gel of wild-type iL3s (top) or unc F1 iL3s from RNP injections at site #3 (bottom). Genomic DNA from each iL3 was split into two reactions: ctrl. = control reaction amplifying 416 bp of the first exon of the Ss-act-2 gene to confirm the presence of genomic DNA; u22 = reaction amplifying 660 bp around site #3. Size markers = 1.5 kb, 1 kb, and 500 bp from top to bottom. (B) The Ss-unc-22 region is significantly depleted in unc F1 iL3s. Left: relative quantity analysis of PCR products. All control bands and all u22 bands were quantified relative to their respective reference bands, denoted by asterisks in A. Values >1 indicate more PCR product than the reference while values <1 indicate less product. ***P<0.001, two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post-test. Medians and interquartile ranges shown. Right: relative quantity of the Ss-unc-22 site #3 target region for each unc F1 iL3 tested, and inferred genotypes. nd = PCR product not detected. (C) Whole-genome sequencing coverage plots for populations of Ss-unc-22-targeted F1 iL3s or wild-type iL3s. A 4-kb window centered on the predicted cut site is shown [24,47]. Black lines = average coverage depth by position (reads per base); red lines = average genome-wide coverage; blue lines = average coverage for the Ss-unc-22 gene. Coverage around Ss-unc-22 site #3 is significantly depleted in both Ss-unc-22 libraries relative to the Ss-unc-22 gene average (P<0.05; see Methods). No depletion is observed in the wild-type library (P>0.05; see Methods). Gray shaded regions represent stretches of continuous significant coverage depletion around the cut site (Ss-unc-22 library A = 510 bp, Ss-unc-22 library B = 725 bp).

To test the hypothesis that CRISPR-Cas9-mediated mutagenesis results in deletions at the target region, we performed a large-scale microinjection of free-living adults with the RNP complex targeting Ss-unc-22 site #3. We focused on site #3 since it appeared to produce the most efficient mutagenesis of Ss-unc-22 (Fig 3B). A single-stranded oligodeoxyribonucleotide (ssODN) was also included in the injection mix to further improve targeting efficiency (described below). We collected a mixed population of wild-type and unc F1 iL3s, where ~40% of the iL3s displayed the nicotine-twitching phenotype. From this mixed wild-type and unc F1 population, we prepared two libraries for whole-genome sequencing, as well as a library prepared entirely from wild-type iL3s (S4 Table). We found that the Ss-unc-22 libraries showed significant depletion in read coverage for an extended stretch of >500 base pairs around Ss-unc-22 site #3, while no such depletion was observed in the wild-type library (Fig 4C). When targeting Ss-unc-22 site #3, we found no evidence for read depletion at Ss-unc-22 site #1 or site #2 in either Ss-unc-22 library (S3 Fig). Similarly, we found no evidence for read depletion at an unrelated CRISPR target at a distant genomic location in the Ss-tax-4 gene (see below) (S4 Fig). The observation that read coverage is depleted specifically around site #3 in the Ss-unc-22 libraries, but not in the wild type, is consistent with the hypothesis that CRISPR-Cas9-mediated mutagenesis results in large deletions rather than small indels at the target locus. To further confirm the lack of small indels, we analyzed indel frequency in the deep-sequencing samples using the CRISPRessoWGS and CRISPRessoCompare computational suite [29]. The CRISPRessoWGS program is designed to analyze deep-sequencing reads aligned to a reference genome and quantify CRISPR-Cas9-editing outcomes, such as indels, at defined targets of interest [29]. We again found no evidence for indels at Ss-unc-22 site #3 in either Ss-unc-22 library, suggesting that all of the reads overlapping Ss-unc-22 site #3 were obtained either from wild-type F1 iL3s in the sample or from heterozygous/mosaic unc F1 iL3s where deletion of the target locus was incomplete.

We note that while >500 base pairs around Ss-unc-22 site #3 were found to be significantly depleted by whole-genome sequencing, the size of the deletion in many individual unc iL3s is likely to be substantially larger. There are a number of possible explanations for why a depleted region of only ~500 base pairs was observed in whole-genome sequencing analysis. First, whole-genome sequencing was performed on a mixed population of iL3s that included both wild-type and unc individuals. A mixed population was prepared because, given the labor-intensive nature of the microinjection procedure and screening process for unc iL3s, it was impractical to create an all-unc population of sufficient density for reliable whole-genome sequencing. As a result, many of the reads from the Ss-unc-22 libraries were in fact from wild-type individuals. Second, the vast majority of individuals with the unc phenotype in the Ss-unc-22 libraries were mosaics or heterozygotes, and therefore contained wild-type sequence in addition to edited sequence (Fig 4B). Third, each mutant F1 iL3 in the Ss-unc-22 libraries had a potentially different deletion, since the population was not clonal. For these reasons, it is likely that the only region that showed significant depletion is the deleted region that is shared among all of the unc iL3s. Many unc iL3s may contain larger deletions, as suggested by our PCR results, but these deletions may be positioned asymmetrically around the target site, with the exact breakpoints varying across individuals. The varied nature of these deletions, coupled with the mixture of wild-type and edited DNA sequence, made it impossible to detect larger depletions in the whole-genome sequencing experiments.

Our finding that CRISPR-Cas9-mediated DSBs resulted in deletion of the target locus raised the possibility of unintended disruption of nearby genes. We therefore asked if genomic loci upstream and downstream of Ss-unc-22 site #3 were intact following CRISPR-Cas9-mediated deletions. To test this, we isolated rare unc F1 iL3s with putative homozygous deletions of Ss-unc-22. For each iL3, we then PCR-amplified regions 10-kb upstream and downstream of the target site; the downstream target amplified in the second exon of the closest gene neighboring Ss-unc-22 (S5A Fig). For all of the unc F1 iL3s tested, we successfully amplified the upstream and downstream targets, suggesting that genomic loci near Ss-unc-22 site #3 are intact following CRISPR-Cas9-mediated deletions (S5B Fig).

We attempted to map the precise endpoints of the Ss-unc-22 deletion events in unc iL3s by PCR-amplifying regions of increasing size, up to 20 kilobases, around the CRISPR target site. However, we never observed PCR products smaller than the wild-type product. We always observed either the wild-type product or no product (Fig 4, S5 Fig). This is likely due to the fact that each deletion in an individual iL3 is potentially unique, making it difficult to optimally design primers to robustly PCR-amplify multiple different deletion events. Further complicating this approach, genomic DNA isolated from individual iL3s is low in concentration, and amplicons of >2–3 kb cannot be amplified reliably. Thus, mapping the endpoints of deletion events was not feasible from individual unc iL3s. Additionally, we cannot exclude the possibility that complex chromosomal rearrangements, inversion events, or deletions with inversion events occurred that could not be detected via the methods utilized in this study. Both large deletions and chromosomal rearrangements have been observed in C. elegans in some cases, and this phenomenon may be more common at certain genomic loci than others [30]. Similar chromosomal rearrangements may have precluded our ability to precisely map CRISPR-mediated mutation events at Ss-unc-22 targets.

Taken together, our results suggest that CRISPR-Cas9-induced mutations to Ss-unc-22 are not resolved by small indels near the target, but instead result in deletions around the target site. Importantly, we infer putative homozygous deletions of Ss-unc-22 in ~2–5% of the unc F1 iL3s genotyped by PCR (S3 Table). Given the challenges for targeted mutagenesis in parasitic nematodes, the ability to isolate homozygous deletions in the F1 generation is critical because it allows for mutant analysis without the need for laborious host passage.

Homology-directed repair of CRISPR-Cas9-mediated mutations in S. stercoralis

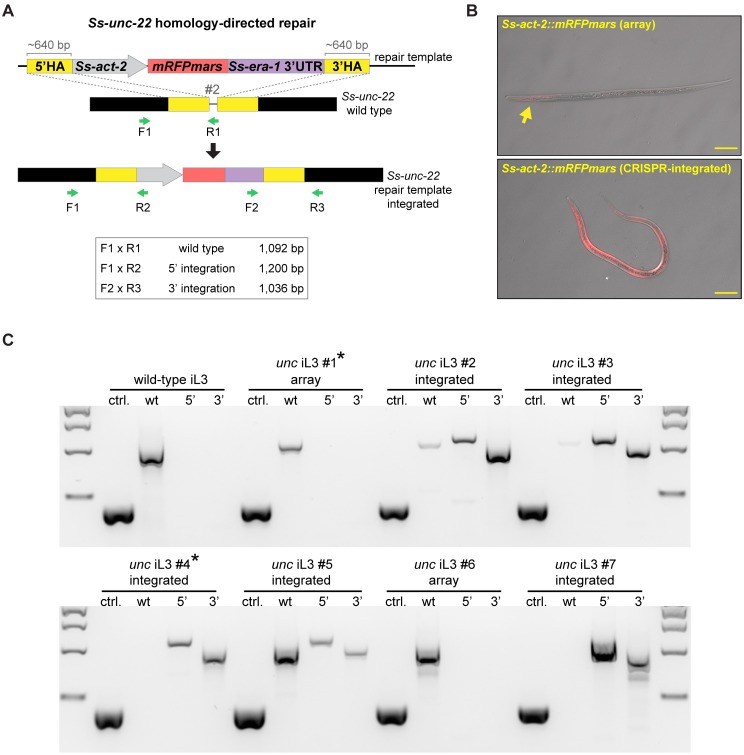

CRISPR-Cas9-induced DSBs can also be resolved by HDR when a repair template is provided [5]. We asked if DSBs at Ss-unc-22 could incorporate a repair template containing a fluorescent reporter by HDR, thereby providing an alternative to deletion of the target locus that would facilitate genotyping as well as identification of mutant nematodes. To address this question, we designed a plasmid containing a repair template for Ss-unc-22 site #2. The repair template consisted of mRFPmars under the control of the promoter for the Strongyloides actin gene Ss-act-2, which expresses in contractile filaments of the nematode body wall [31]; the reporter was flanked by homology arms directly adjacent to the CRISPR-Cas9 cut site (Fig 5A). We injected plasmid vectors for the repair template, Cas9, and the sgRNA for site #2 into S. stercoralis. Interestingly, we found that injections including the repair template increased the percentage of unc F1 iL3s twitching in nicotine when compared to injections without a repair template (S6A Fig, S5 Table). We then isolated unc F1 iL3s that displayed a nicotine-twitching phenotype and screened for mRFPmars expression, predicting that a subset of these iL3s had successfully repaired CRISPR-Cas9-induced DSBs by HDR. We isolated unc F1 iL3s with a range of mRFPmars expression patterns and fluorescence intensities (Fig 5B). unc F1 iL3s that expressed mRFPmars were genotyped for integration of the repair template using primer sets that spanned the 5’ and 3’ boundaries of the inserted cassette (Fig 5A). We found that >50% of the unc F1 iL3s that expressed mRFPmars showed integration of the repair template at Ss-unc-22 (Fig 5C, S6 Table). Importantly, we isolated several integrated iL3s that appeared to be putative homozygous knockouts of Ss-unc-22: these iL3s were found to lack a wild-type PCR product using a reverse primer that binds the target site (Fig 5C, S6 Table). These results demonstrate the feasibility of generating putative homozygous mutant iL3s in the F1 generation using HDR. Sequencing from the 5’ and 3’ boundaries of the repair template confirmed its insertion at the target site (S7 Fig).

Fig 5. CRISPR-mediated homology-directed repair of Ss-unc-22.

(A) Strategy for HDR at Ss-unc-22 target site #2. unc F1 iL3s that displayed both the nicotine-twitching phenotype and red fluorescence were selected as candidates for HDR and were genotyped using the primer sets indicated. 5’ and 3’ integration primer pairs amplify only following successful integration of Ss-act-2::mRFPmars into site #2. HA = homology arm. (B) Representative DIC + epifluorescence overlays of unc F1 iL3s expressing Ss-act-2::mRFPmars. Top, iL3 expressing mRFPmars (sparse expression indicated by the arrow) from an extrachromosomal array. Bottom, iL3 expressing mRFPmars following HDR, showing near-uniform mRFPmars expression in the body wall. For both images, anterior is to the left. Scale bar = 50 μm. (C) Representative genotypes of a wild-type iL3 and unc F1 iL3s expressing mRFPmars. Genomic DNA from individual iL3s was split into four reactions: ctrl. = control reaction amplifying 416 bp of the first exon of the Ss-act-2 gene to confirm the presence of genomic DNA; wt = reaction for the wild-type locus of site #2 where primer R1 overlaps the predicted CRISPR cut site; 5’ = reaction for insertion of the 5’ border of the integrated cassette; 3’ = reaction for insertion of the 3’ border of the integrated cassette. For genotypes: array = red unc F1 iL3s that showed no evidence of integration; integrated = red unc F1 iL3s with successful HDR. Some integrated iL3s had putative homozygous disruptions of Ss-unc-22 site #2 (e.g. iL3s #4 and #7, which lacked the wt band). Asterisks indicate genotypes for iL3s shown in B. Size markers = 2 kb, 1.5 kb, 1 kb, and 500 bp from top to bottom.

In C. elegans, CRISPR-Cas9-induced DSBs can also be resolved by HDR using an ssODN repair template [20,32]. The ssODN repair strategy has the advantage that ssODNs can be commercially synthesized to allow for rapid CRISPR target testing [20,32]. We asked if ssODNs are also suitable repair templates for HDR in S. stercoralis. We designed an ssODN for Ss-unc-22 site #3 (S8A and S8B Fig) and injected it with RNP complexes targeting the same site. Our ssODN was designed in the sense orientation, because sense orientation ssODNs have been shown, in some cases, to be more effective HDR templates in C. elegans [33]. As with the presence of the Ss-act-2::mRFPmars repair template, the presence of the ssODN increased the percentage of unc F1 iL3s twitching in nicotine (S6B Fig, S5 Table). However, we found no evidence for ssODN integration at Ss-unc-22 site #3 (S8C and S8D Fig). To determine if the absence of ssODN integration was due to the target site selected, or delivery method, we also designed an ssODN for Ss-unc-22 site #2 and injected it with plasmid vectors. Similarly, we saw no evidence for ssODN integration when using the same target site and delivery method that was used for Ss-act-2::mRFPmars integration. Our results raise the possibility that incorporation of ssODNs into CRISPR-Cas9-mediated DSBs may not be feasible in S. stercoralis.

To confirm that integration of the Ss-act-2::mRFPmars repair template by HDR was specific to CRISPR-Cas9-induced DSBs at Ss-unc-22, we repeated injections but removed the Cas9 plasmid vector. We did not observe unc F1 iL3s twitching in nicotine when Cas9 was omitted, suggesting that Ss-unc-22 site #2 was not disrupted in the absence of Cas9-induced DSBs (S9A Fig). Similarly, we found no evidence for unc F1 iL3s twitching in nicotine when Cas9 was omitted from RNP complex injections (S9B Fig). Thus, DSBs at Ss-unc-22 appear to be specifically triggered by CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis.

We next asked if CRISPR-Cas9-mutagenesis coupled with HDR of a fluorescent reporter was applicable to other S. stercoralis genes. To further validate our HDR approach, we targeted the S. stercoralis ortholog of the C. elegans tax-4 gene. Ce-tax-4 encodes a subunit of a cyclic nucleotide gated ion channel that is required for many chemosensory-driven responses in sensory neurons [34,35]. We identified a CRISPR target site for Ss-tax-4 and modified the mRFPmars repair template to contain homology arms near the Ss-tax-4 CRISPR-Cas9 cut site (S10A and S10B Fig). Following injection of the repair template, Cas9, and the sgRNA for Ss-tax-4 site #1, we collected F1 iL3s and screened for mRFPmars expression, again predicting that some of these iL3s would show integration events. As with HDR at Ss-unc-22, we isolated mRFPmars-expressing F1 iL3s that showed Ss-tax-4 integration events by PCR (S10C Fig, S6 Table). Sequencing from the 5’ boundary of the repair template confirmed its insertion at the Ss-tax-4 target site (S10D Fig).

Taken together, we conclude that DSBs in S. stercoralis are specifically triggered by CRISPR-Cas9-mediated mutagenesis, and can be precisely resolved by HDR when a plasmid repair construct is provided. Furthermore, as demonstrated with integration of Ss-act-2::mRFPmars, repair constructs containing a fluorescent reporter can be used to efficiently screen for gene disruptions in the F1 generation. This approach will likely be applicable to many genes of interest in the S. stercoralis genome.

Heritable transmission of Ss-unc-22 mutations

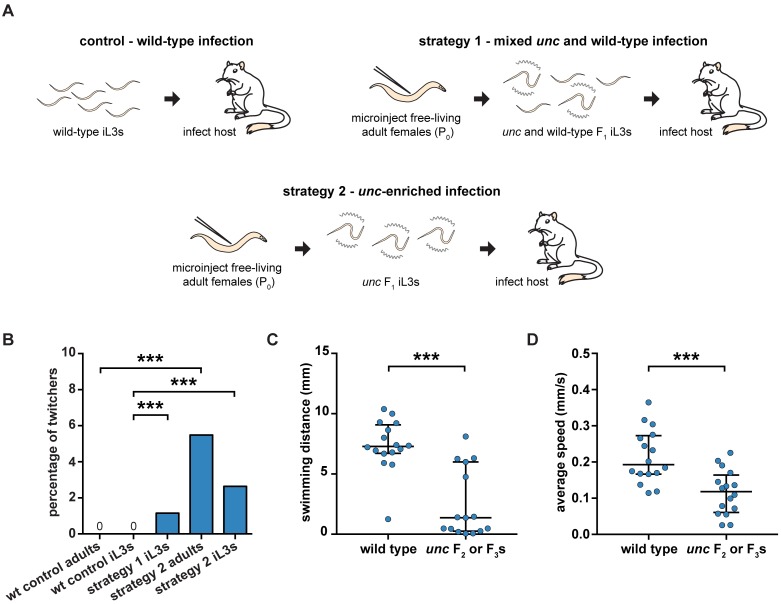

One of the challenges for generating targeted gene disruptions in S. stercoralis is the need to passage F1 progeny through a host to maintain the mutation of interest [3]. We developed two strategies to examine if CRISPR-Cas9-induced Ss-unc-22 mutations are heritable following host passage. First, we injected CRISPR-Cas9 complexes into free-living adult females and collected F1 iL3s where approximately 50% of the F1 population twitched in nicotine. The mixed population of unc F1 iL3s and wild-type iL3s was then used to infect gerbils, which are permissive laboratory hosts for S. stercoralis [36,37]. In a second approach, we injected free-living adult females, collected F1 iL3s, enriched for nicotine-twitching unc iL3s, and infected gerbil hosts. As a control, we also infected gerbils with exclusively wild-type iL3s (Fig 6A, S7 Table).

Fig 6. The unc phenotype is heritable following host passage.

(A) Strategies for heritable transmission of Ss-unc-22 mutations. Gerbil hosts were infected with either all wild-type iL3s, a 50/50 mix of unc and wild-type F1 iL3s, or unc-enriched F1 iL3s. F2 and F3 progeny were collected from host feces and screened for unc phenotypes. Note that iL3s collected from host feces can be the F2 or F3 generation depending on whether they developed into iL3s directly, or after a free-living generation (Fig 1A) [10]. (B) Twitching frequency of wild-type control progeny and F2 or F3 progeny collected from unc infections. The twitching frequency of the F2 or F3 iL3s collected from the mixed unc infection differed from that of wild-type iL3s. ***P<0.001, chi-square test with Bonferroni correction. n = 1,908–3,849 iL3s per condition. The twitching frequency of F2 adults collected from the unc-enriched infection differed from that of wild-type adults. ***P<0.001, chi-square test with Bonferroni correction. n = 164–332 adults per condition. The twitching frequency of F2 or F3 iL3s collected from the unc-enriched infection differed from that of wild-type iL3s. ***P<0.001, chi-square test with Bonferroni correction. n = 2,694–3,849 iL3s per condition. (C) Swimming distance for wild-type iL3s vs. unc F2 or F3 iL3s over a 10-s period. unc iL3s swam shorter distances than wild-type iL3s. ***P<0.001, Mann-Whitney test. n = 15–16 worms for each population. (D) Mean crawling speed for wild-type iL3s vs. unc F2 or F3 iL3s over a 20-s period. unc iL3s showed reduced crawling speeds relative to wild-type iL3s. ***P<0.001, unpaired t test with Welch’s correction. n = 16 worms for each population.

Following host infection, we collected host feces from each germline transmission strategy, reared F2 and F3 progeny, and screened for the nicotine-twitching phenotype as an indicator of successful germline inheritance of Ss-unc-22 mutations. From the mixed unc and wild-type infection strategy, we exclusively screened for the twitching phenotype in F2 or F3 iL3s. We successfully isolated nicotine-twitching unc F2 or F3 iL3s from the mixed infection over multiple fecal collection days but never observed twitching iL3s from the wild-type control (S7 Video). The average nicotine-twitching frequency of iL3s collected from the mixed infection was 1.2% (Fig 6B, S7 Table). From the unc-enriched infection, we screened for the twitching phenotype in both F2 free-living adults and F2 or F3 iL3s. We isolated nicotine-twitching unc F2 free-living adults from the unc-enriched infection but never observed twitching adults from the wild-type control (S8 and S9 Videos). The nicotine-twitching phenotype was observed in ~5% of F2 adults (Fig 6B, S7 Table). When we screened F2 or F3 iL3s from the unc-enriched infection, we observed a nicotine-twitching frequency of 2.6% (Fig 6B, S7 Table). An ~5% twitching frequency in F2 free-living adults and an ~2.5% twitching frequency in their F3 iL3 progeny is consistent with the unc phenotype being dominant, and with unc F3 iL3s resulting from mating events between an unc individual and a wild-type individual.

To further validate germline transmission of Ss-unc-22 mutations, we also characterized the unc motility phenotypes of F2 and F3 iL3s. Twitching F2 or F3 iL3s were recovered from nicotine and their motility was compared to nicotine-recovered wild-type iL3s. unc F2 or F3 iL3s showed impaired swimming behavior when compared to wild-type iL3s (Fig 6C). Similarly, automated tracking revealed that unc F2 or F3 iL3s showed reduced crawling speeds relative to wild-type iL3s (Fig 6D). The unc phenotype observed for F2 or F3 iL3s was similar to that observed for F1 iL3s (Fig 2). Thus, CRISPR-Cas9-mediated mutations are germline-transmissible, and mutant parasites can be propagated by host passage.

Discussion

Here we demonstrate the first targeted gene disruptions in a parasitic nematode resulting in a mutant phenotype. We exploited the complex life cycle of the human-parasitic threadworm S. stercoralis to deliver CRISPR-Cas9 constructs targeting Ss-unc-22 into free-living adults, and characterized Ss-unc-22 mutations in iL3 progeny (Fig 1). Using this strategy, we generated free-living adults and infective larvae with severe motility defects and altered nicotine sensitivity (Figs 2, 3 and 6). Furthermore, we optimized CRISPR-Cas9 targeting and obtained putative homozygous knockouts in the F1 generation, a development that circumvents the necessity for labor-intensive host passage and allows for the immediate interrogation of mutant phenotypes in parasitic worms (Figs 4 and 5). A similar approach is likely to be immediately applicable to other parasitic nematode species, particularly those in the Strongyloides and Parastrongyloides genera, which are well-suited for gonadal microinjection of CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid vectors or RNP complexes [23,38,39]. Importantly, our results demonstrate that the CRISPR-Cas9 system is functional in parasitic nematodes and represents the first realistic opportunity for systematic gene knockout studies. With additional technical development, this approach may be adaptable to other parasitic nematodes with environmental life stages, such as numerous plant-parasitic and entomopathogenic nematode species.

Both S. ratti and S. stercoralis have been proposed as models for targeted mutagenesis in parasitic nematodes [3,11]. S. ratti has the advantage of requiring fewer iL3s to infect a host; only ~10-20 S. ratti iL3s are needed to infect a rat, while >1,000 S. stercoralis iL3s are needed to reliably infect a gerbil. Thus, S. ratti has been considered the more efficient option for generating stable lines [3,37,40]. In contrast, S. stercoralis has been shown to be more tolerant of the gonadal microinjection procedure and F1 nematodes express transgenes more efficiently [3,11,40]. We found that CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis in Strongyloides was strikingly similar to reported transgenesis outcomes; unc-22 mutagenesis was more efficient in S. stercoralis than S. ratti, with 17–28% and 2–7% of F1 iL3s twitching in nicotine, respectively, when using plasmid vector delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 and injecting a similar number of P0 females (Fig 3, S2 Fig, S1 and S2 Tables). The higher mutagenesis efficiency we observed with S. stercoralis may reflect its increased tolerance of the microinjection procedure. However, future work targeting a number of different genes in S. stercoralis and S. ratti will be necessary to determine whether CRISPR-Cas9-mediated mutagenesis is more efficient in S. stercoralis at all target sites, or only in certain cases. Importantly, the rate of CRISPR-Cas9-mediated mutagenesis in S. stercoralis was sufficient for germline-transmission and host propagation, as we collected F2 adults and F2 or F3 iL3s with unc phenotypes after host passage (Fig 6). However, we note that long-term propagation of the Ss-unc-22 mutations was not practical given the low efficiency of F2 and F3 mutant recovery (Fig 6), presumably because the severe motility defects of Ss-unc-22 iL3s reduced their ability to establish an infection in the host.

Based on the CRISPR-mediated disruption of Ss-unc-22 and Sr-unc-22 presented here, future studies pursuing targeted mutagenesis are likely to be feasible in both S. stercoralis and S. ratti, with each system having potential advantages. S. stercoralis, in addition to its direct health relevance as a human parasite, may prove to be a more valuable system for pursuing rapid investigation of homozygous knockouts in the F1 generation. Our results show that F1 mutagenesis was efficient enough to generate putative homozygous knockouts of Ss-unc-22 (Figs 4 and 5). Further adding to the potential utility of S. stercoralis, a recent study demonstrated that heritable transgenesis is also possible by microinjection of plasmid constructs into the testicular syncytium of free-living males [41]. Future CRISPR-Cas9 strategies simultaneously targeting both S. stercoralis free-living males and females may further improve the incidence of F1 homozygous knockouts. In contrast to S. stercoralis, gene disruptions in S. ratti are likely to be easier to maintain through successive rounds of host passage due to a more manageable infective dose. Additionally, given the wealth of information for host-parasite interactions between S. ratti and the rat host, gene knockout studies focused on host immune response, parasite immune manipulation or evasion, and anthelmintic drug administration may be well-suited to this system [42].

Targeted mutagenesis in parasitic nematodes presents a unique challenge in that mutant progeny must be propagated through a host to continue the life cycle. In some cases, knocking out a gene of interest may interfere with the ability of iL3s to infect a host. For example, we recovered only a small percentage of unc progeny in the F2 and F3 generations following host passage (Fig 6, S7 Table). As mentioned above, one hypothesis for the low frequency of unc F2 and F3 progeny is that unc iL3s are disadvantaged relative to wild-type iL3s during host infection. Host infection is a multi-step migratory process; iL3s infect by skin penetration, navigate to the circulatory system, penetrate the lungs, and are then thought to be coughed up and swallowed en route to parasitizing the intestinal tract [9]. We observed severe motility defects in unc F1 iL3s that may handicap their ability to migrate inside the host (Fig 2). Supporting the hypothesis that unc motility defects might impede host infection, we consistently recovered fewer F2 and F3 nematodes from the host feces of unc-enriched infections than wild-type infections, despite infecting gerbil hosts with similar numbers of F1 iL3s (S7 Table). Mutagenesis studies targeting genes that are essential for parasitic nematodes to infect or develop within the host could be difficult to maintain over multiple generations, although it may be possible to maintain recessive mutations in these genes by passaging heterozygous iL3s through hosts. CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis that can efficiently generate homozygous knockouts in a single generation may prove to be the most realistic option for mutant analysis in these cases, and we have demonstrated that this approach is feasible in S. stercoralis. In contrast, target genes that are not required for infectivity or in-host development may be easier to maintain than the Ss-unc-22 mutations generated here.

Our results suggest that S. stercoralis can correct CRISPR-Cas9-induced DSBs by HDR when a plasmid repair template is provided, but not an ssODN (Fig 5, S8 and S10 Figs). In the absence of HDR, we found no evidence for indels at the Ss-unc-22 target sites tested but instead observed putative large deletions of the target locus (Fig 4). Many eukaryotes predominantly use NHEJ as a DSB repair mechanism [5–7,19,25]. However, whether S. stercoralis is capable of NHEJ remains unclear. In C. elegans, DSBs in somatic tissues are repaired by NHEJ, but recent work has demonstrated that germline CRISPR-induced DSBs are repaired by polymerase theta (POLQ)-mediated end joining [43]. Interestingly, CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis in polq-1 deficient C. elegans routinely results in deletions averaging 10–15 kilobases, including at Ce-unc-22 targets [43]. In addition, CRISPR-mediated deletions have also been observed in systems that are capable of NHEJ repair. For example, a recent report of CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis outcomes in mouse embryonic stem cells suggests that ~20% of edited cells resolve mutations by deletions of 250–9500 base pairs [44]. We hypothesize that S. stercoralis may favor deletion-based repair of DSBs over generating small indels near the cut site. While we were unable to map the precise endpoints of putative deletions at Ss-unc-22, our results suggest that the deletions were greater than 500 base pairs in unc F1 iL3s, and that the regions 10 kilobases upstream and downstream of the target were unaltered (Fig 4, S5 Fig). We cannot, however, rule out the possibility of more complex DSB repair outcomes such as chromosomal rearrangements, inversion events, or rare indels not detected with the methods used here. Further work will be needed to characterize the DSB repair mechanism in the S. stercoralis germline in more detail.

In practical terms, HDR using a repair template may be the most straightforward application of CRISPR-Cas9-mediated mutagenesis in Strongyloides given that: 1) adding a repair template increases overall targeting efficiency (S6 Fig), 2) HDR is sufficient to generate putative homozygous knockouts in the F1 generation (Fig 5, S6 Table), 3) HDR results in precise insertion of the construct of interest at the CRISPR target site instead of generating large deletions (Fig 5, S7 and S10 Figs), 4) incorporation of a fluorescent marker, like mRFPmars, simplifies mutant identification and isolation (Fig 5B), and 5) an HDR-based gene disruption strategy is likely to be applicable to many targets in the S. stercoralis genome (S10 Fig).

In-depth molecular studies in parasitic nematodes have not yet been feasible due to the lack of a toolkit for genetic intervention. We have developed the first practical method for targeted gene disruptions in parasitic nematodes using CRISPR-Cas9. Our results provide a foundation for making these previously intractable parasites more accessible to functional molecular analysis, which may accelerate the development of new strategies to prevent human-parasitic nematode infections.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

Gerbils were used to passage S. stercoralis. Rats were used to passage S. ratti. All protocols and procedures used in this study were approved by the UCLA Office of Animal Research Oversight (Protocol No. 2011-060-21A), which adheres to AAALAC standards and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Nematodes and hosts

C. elegans strains were either N2 Bristol (wild type) or CB66 Ce-unc-22(e66) and were obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center. Strongyloides stercoralis were the UPD strain and Strongyloides ratti were the ED321 strain [22]. Male Mongolian gerbils used to maintain S. stercoralis were obtained from Charles River Laboratories. Female Sprague-Dawley rats used to maintain S. ratti were obtained from Envigo Laboratories.

Maintenance of S. stercoralis

S. stercoralis was maintained by serial passage in male Mongolian gerbils as described [36]. S. stercoralis infective third-stage larvae (iL3s) were collected from fecal-charcoal cultures using a Baermann apparatus [36]. iL3s were cleaned of fecal debris by passage through ~0.5% low-gelling-temperature agarose (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. # A0701) and washed 5 times in sterile 1x PBS. Isoflurane-anesthetized gerbils were inoculated by subcutaneous injection of ~2,250 iL3s suspended in 200 μL sterile 1x PBS. Feces infested with S. stercoralis were collected during the patency period of infection, between days 14–45 post-inoculation. Fecal pellets were obtained by placing infected gerbils on wire cage racks overnight with wet cardboard lining the cage bottom; fecal pellets were collected the following morning. Fecal pellets were softened with dH2O, crushed, and mixed in a 1:1 ratio with autoclaved charcoal granules (bone char from Ebonex Corp., Cat # EBO.58BC.04). Fecal-charcoal cultures were stored in Petri dishes (10-cm diameter x 20-mm height) lined with dH2O-saturated filter paper. To collect free-living S. stercoralis adults, fecal-charcoal cultures were stored at 20°C for 48 h and adults were isolated using a Baermann apparatus. To collect iL3s, fecal-charcoal cultures were stored at 23°C for at least 5 days and iL3s were isolated using a Baermann apparatus.

Maintenance of S. ratti

S. ratti was maintained by serial passage in female Sprague-Dawley rats as described [45]. S. ratti iL3s were collected from fecal-charcoal cultures using a Baermann apparatus and washed 5 times in sterile 1x PBS. Rats were inoculated by subcutaneous injection of ~800 iL3s suspended in 300 μL sterile 1x PBS. Feces infested with S. ratti were collected during the patency period of infection, between days 7–23 post-inoculation. Feces from infected rats were collected and made into fecal-charcoal cultures using the same procedure described above. To collect free-living S. ratti adults, fecal-charcoal cultures were stored at 20°C for 48 h and adults were isolated using a Baermann apparatus. To collect iL3s, fecal-charcoal cultures were stored at 23°C for at least 5 days and iL3s were isolated using a Baermann apparatus.

Maintenance of C. elegans

C. elegans N2 and CB66 were cultured at room temperature on 6-cm Nematode Growth Media (NGM) plates with E. coli OP50 bacteria using standard methods [46]. Young adult C. elegans used in nicotine assays were collected directly from NGM plates containing OP50. Dauer larvae used in nicotine assays were collected in dH2O by washing them off of NGM plates where all the OP50 had been consumed. Dauers suspended in dH2O were pelleted at 1,000 rpm for 2 min and the supernatant was removed. Pelleted nematodes were then treated with 5 mL of 1% SDS for 15 min at room temperature. After SDS treatment, the nematodes were washed 3x with dH2O and transferred to a glass dish. Chemically resistant dauer larvae that survived the SDS treatment were selected and tested in nicotine assays.

Selection of CRISPR target sites for Ss-unc-22, Sr-unc-22 and Ss-tax-4

The Ss-unc-22 gene was identified based on sequence homology with C. elegans unc-22. Briefly, the C. elegans UNC-22 (isoform a) amino acid sequence was used as the query in the TBLASTN search tool to search against the S. stercoralis genome in WormBase ParaSite (PRJEB528, version WBPS9) [24,47]. The S. stercoralis gene SSTP_0000031900 was predicted as Ss-unc-22 based on 55.3% pairwise amino acid identity with Ce-unc-22; SSTP_0000031900 was also predicted in WormBase ParaSite as a twitchin and an ortholog of Ce-unc-22 [24,47]. Reciprocal BLAST of SSTP_0000031900 against the C. elegans genome predicted Ce-unc-22 as the best hit. BLAST of SSTP_0000031900 against the S. stercoralis genome revealed no other obvious unc-22 orthologs. We searched for CRISPR target sites in Ss-unc-22 exon 7, the largest exon and the exon with the highest degree of conservation to Ce-unc-22. Potential CRISPR target sites were identified with Geneious 9 software using the Find CRISPR Sites plugin [48]. We restricted our CRISPR target sites to those with guanine residues in the 1st, 19th, and 20th positions in the target sequence (GN(17)GG) and the Cas9 PAM sequence (NGG); these guidelines were established in Farboud et al. 2015 for highly efficient guide RNA design in C. elegans [49]. We selected CRISPR target sites with a range of predicted on-target activity scores based on the algorithm developed in Doench et al. 2014, where scores range from 0 to 1, with higher scores representing higher predicted activity (Fig 1B) [50]. We discarded CRISPR target sites with off-target scores under 80% based on the algorithm developed in Hsu et al. 2013, where potential targets are rated from 0 to 100%, with higher scores indicating less off-target activity [51]. The same approach was taken to identify Sr-unc-22 (SRAE_X000227400) in the S. ratti genome (PRJEB125, version WBPS9 on WormBase ParaSite) [24,47]. S. ratti CRISPR target sites were selected using the same restrictions outlined for S. stercoralis. The Ss-tax-4 gene, SSTP_0000981000, was similarly identified based on sequence homology with C. elegans tax-4, and was also predicted in WormBase ParaSite as an ortholog of Ce-tax-4 [24,47]. The Ss-tax-4 CRISPR target was selected using the same restrictions outlined for Ss-unc-22. Gene structure diagrams for S. stercoralis (Fig 1B and S10A Fig) and S. ratti (S2A Fig) were generated with Exon-Intron Graphic Maker (Version 4, www.wormweb.org).

Plasmid vectors for targeted mutagenesis with CRISPR-Cas9

A summary of all plasmid vectors used in this study can be found in S8 Table. pPV540 expressing Strongyloides-codon-optimized Cas9 under the control of the S. ratti eef-1A promoter (previously called eft-3 in C. elegans [19]) was a gift from Dr. James Lok. pPV540 includes the S. stercoralis era-1 3’UTR; Strongyloides-specific regulatory elements are required for successful expression of transgenes in S. stercoralis and S. ratti [52]. The sgRNA expression vectors for targeting Ss-unc-22, Sr-unc-22, and Ss-tax-4 were synthesized by GENEWIZ in the pUC57-Kan backbone. The S. ratti U6 promoter and 3’ UTR were identified by sequence homology with C. elegans U6 [19]; 500 bp and 277 bp regions of the Sr-U6 promoter and 3’ UTR, respectively, were included in each sgRNA expression vector. For all sgRNA constructs, a non-base-paired guanine was added to the 5’ end (-1 position on the guide) of each sgRNA to improve RNA polymerase III transcription [49]. Target sequences are provided in S9 Table. The repair construct pEY09 was generated by subcloning approximately 640 bp 5’ and 3’ homology arms flanking Ss-unc-22 site #2 into the Strongyloides mRFPmars expression vector pAJ50 (a gift from Dr. James Lok) [31]. Ss-unc-22 site #2 was chosen for HDR based on the observation that it was targeted efficiently using plasmid-based delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 constructs (Fig 3B). The repair construct pMLC39 was generated by subcloning approximately 1-kb 5’ and 3’ homology arms flanking Ss-tax-4 site #1 into pAJ50. Primer sets used to amplify the Ss-unc-22 site #2 and Ss-tax-4 site #1 5’ and 3’ homology arms from S. stercoralis genomic DNA can be found in S13 Table. Injection mixes containing plasmid vectors and concentrations used in this study can be found in S10 Table. Plasmid vector injection mixes were diluted to the desired concentration in ddH2O, centrifuged at 14,800 rpm on a bench-top centrifuge through a 0.22 μm tube filter (Costar Spin-X Cat. # 8106) for 15 min, and stored at room temperature prior to use in microinjection experiments. The total DNA concentration injected into free-living Strongyloides adult females was limited to a maximum of 100 ng/μL, as described in Junio et al. 2008 [31].

Ribonucleoprotein complexes for targeted mutagenesis with CRISPR-Cas9

RNP complexes were assembled in vitro essentially as described [20]. Lyophilized crRNAs targeting Ss-unc-22 were synthesized commercially (Dharmacon Edit-R Synthetic Modified crRNA, 20 nM) and resuspended in nuclease-free dH2O to 4 μg/μL. crRNA sequences are provided in S11 Table. Lyophilized tracrRNA was synthesized commercially (Dharmacon U-002000–20, 20 nM) and resuspended in nuclease-free ddH2O to 4 μg/μL. Lyophilized ssODN for Ss-unc-22 site #3 was synthesized commercially (IDT Ultramer DNA Oligo, 4 nM) and resuspended in nuclease-free ddH2O to 500 ng/μL. crRNA, tracrRNA, and ssODN stocks were stored at -20°C until use and kept on ice during RNP complex preparation. RNP injection mixes were made as shown in S12 Table and added to 10 μg of lyophilized recombinant Cas9 protein from Streptococcus pyogenes (PNA Bio Inc., Cat. #CP01). The solution was centrifuged for 2 min at 13,000 rpm in a bench-top centrifuge and incubated at 37°C for 15 min to assemble RNP complexes. RNP complex solution was stored on ice prior to use in microinjection experiments.

Microinjection of Strongyloides free-living adults

Gonadal microinjection of plasmid vectors or RNP complexes into the syncytial gonad of S. stercoralis or S. ratti free-living adult females was performed as described for S. stercoralis, S. ratti, and C. elegans [18,31,45]. Microinjected females were transferred to 6-cm NGM plates containing OP50 for recovery, and free-living wild-type adult males were added for mating. After a minimum injection recovery time of approximately 30 min, NGM plates were flooded with dH2O and free-living males and females were transferred to 6-cm fecal-charcoal plates using non-stick sterile worm-transferring tips (BloomingBio, Cat. # 10020-200-B). Uninfected gerbil feces were collected as described above and used to make fecal-charcoal cultures for S. stercoralis. Uninfected rat feces were collected as described above and used to make fecal-charcoal cultures for S. ratti. Host feces were used for post-injection incubation based on the observation that the reproductive output of Strongyloides free-living adults is better on feces than with standard C. elegans culturing methods [53]. Fecal-charcoal cultures were maintained at 23°C. After 5–14 days, F1 iL3s were recovered from the fecal-charcoal plates using a Baermann apparatus. The average number of F1 iL3s collected from feces per injected female for S. stercoralis and S. ratti can be found in S14 Table. iL3s were stored in dH2O for 1–2 days at room temperature until behavioral analysis and subsequent genotyping. For each Strongyloides CRISPR-Cas9 target site and delivery method tested in this study, we microinjected P0 adults and screened F1 iL3s in a minimum of two separate experiments per condition.

Swimming assay

F1 iL3s were recovered from fecal-charcoal cultures using a Baermann apparatus and stored in a glass dish in 2–5 mL of dH2O. Individual iL3s were then transferred in 2–3 μL of dH2O to a 10-cm chemotaxis plate [54]. 10-s recordings of the iL3 swimming in the dH2O drop were immediately obtained using an Olympus E-PM1 digital camera attached to a Leica M165 FC microscope. Swimming distances were calculated using the ImageJ Manual Tracking plugin by marking the frame-by-frame position change of the nematode centroid during the 10-s recording and summing the total distance traveled. F2 or F3 wild-type (paralyzed) or unc (twitching) iL3s were recovered from 1% nicotine treatment overnight on chemotaxis plates and tested for swimming behavior the next day.

Automated tracking of iL3 crawling

Automated tracking was performed as described [22]. Briefly, recordings of iL3 movement were obtained with an Olympus E-PM1 digital camera attached to a Leica S6 D microscope. To quantify movement, 3–5 iL3s were placed in the center of a chemotaxis plate in a 5 μL drop of dH2O. Once the drop dried, the iL3s were allowed to acclimate to the plate for 10 min. 20-s recordings were then obtained from each iL3, ensuring that each iL3 was only recorded once. Worm movement was quantified using WormTracker and WormAnalyzer software (Miriam Goodman lab, Stanford University) [21]. The following WormTracker settings were used: minimum single worm area = 20 pixels; maximum size change by worm between successive frames = 250 pixels; shortest valid track = 30 frames; auto-thresholding correction factor = 0.001. F2 or F3 wild-type (paralyzed) or unc (twitching) iL3s were recovered from 1% nicotine treatment overnight on chemotaxis plates and tested for crawling behavior the next day.

iL3 dispersal assay

Recordings of iL3 movement were obtained with a 5-megapixel CMOS camera (Mightex Systems) equipped with a manual zoom lens (Kowa American Corporation) suspended above a 22-cm x 22-cm chemotaxis plate. To quantify unstimulated movement, individuals iL3s were placed in the center of the chemotaxis plate and allowed to acclimate for 10 min. 5-min recordings were then obtained. Images were captured at 1 Hz using Mightex Camera Demo software (V1.2.0) in trigger mode. Custom Matlab code (MathWorks) and a USB DAQ device (LabJack) were used to generate trigger signals. To quantify maximum dispersal distance, the location of individual iL3s during the recording session was manually tracked using the ImageJ Manual Tracking plugin; maximum distance from initial iL3 location was calculated in Microsoft Excel. Researchers were blinded to twitching phenotype during manual tracking; recording sessions were scored in randomized order.

Nicotine assay

For adult C. elegans assays, 5–10 young adults were transferred from NGM plates containing OP50 onto a chemotaxis plate using a worm pick. 20 μL of a 1% nicotine solution diluted in dH2O was pipetted onto the nematodes. After 8 min in nicotine, individual nematode phenotypes were scored under a dissecting microscope. We characterized four distinct phenotypes: paralyzed = wild-type nicotine response [13]; partially paralyzed = instances where paralysis was nearly complete but we observed minor movements; unaffected = rare instances where the nematode appeared unaffected by nicotine treatment; and twitching = continuous twitching (the unc-22 nicotine response [13]). The percentage of twitchers was calculated as: % twitchers = (# twitching nematodes) / (total # of nematodes screened) x 100. C. elegans dauer assays were performed essentially as described above. dH2O drops containing 6–10 SDS-recovered dauers were pipetted onto chemotaxis plates. The drops were allowed to dry and 20 μL of 1% nicotine solution was pipetted onto the dauers. After 8 min, phenotypes were scored and quantified as described above. Strongyloides free-living adults and iL3s were recovered from fecal-charcoal cultures using a Baermann apparatus and stored in a glass dish in 2–5 mL of dH2O. A chemotaxis plate was subdivided into four sections and ~10 μL of dH2O containing nematodes was pipetted into each quadrant (~5–10 free-living adults or 20–50 iL3s per quadrant, 20–40 free-living adults or 80–200 iL3s per chemotaxis plate). The drops were allowed to dry and 40–50 μL of 1% nicotine solution was pipetted onto the worms. After 8 min, phenotypes were scored and quantified as described for C. elegans. For chi-square analysis, paralyzed, partially paralyzed, and unaffected phenotypes were combined into one “non-twitching nematodes” category and compared to “twitching nematodes.”

Strongyloides genomic DNA preparation

To obtain genomic DNA from S. stercoralis individual iL3s or small pools of iL3s, 1–15 iL3s were transferred to PCR tubes containing 5-6 μL of nematode lysis buffer (50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris pH 8, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.45% Nonidet-P40, 0.45% Tween-20, 0.01% gelatin in ddH2O) supplemented with ~0.12 μg/μL Proteinase-K and ~1.7% 2-mercaptoethanol. Tubes were placed at -80°C for at least 20 min, then transferred to a thermocycler for digestion: 65°C (2 h), 95°C (15 min), 10°C (hold). Genomic DNA samples were stored at -20°C until use. For long-term genomic DNA integrity (>1 week), iL3 samples were stored undigested at -80°C; thermocycler digestion was then performed immediately before testing. To obtain genomic DNA from large populations of ~5,000-10,000 S. stercoralis iL3s, we followed the “Mammalian Tissue Preparation” protocol for the GenElute Mammalian Genomic DNA Miniprep Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. # G1N10); genomic DNA was eluted in 100 μL of dH2O and stored at -20°C until use. To obtain genomic DNA from wild-type iL3 populations or unc F1 iL3 populations for deep sequencing (S4 Table), we followed the “Isolation of Genomic DNA from Tissues” protocol for the QIAamp UCP DNA Micro Kit (Qiagen, Cat. # 56204); genomic DNA was eluted in 15 μL of nuclease-free ultrapure ddH2O and stored at -20°C until library preparation.

Genotyping for Ss-unc-22 deletions

Primer sets used to amplify the regions around Ss-unc-22 target sites, and regions 10-kb upstream and downstream of Ss-unc-22 site #3, can be found in S13 Table. All deletion genotyping PCR reactions were performed with GoTaq G2 Flexi DNA Polymerase (Promega, Cat. # M7801) using the following thermocycler conditions: denature 95°C (2 min); PCR 95°C (30 s), 55°C (30 s), 72°C (1 min) x 35 cycles; final extension 72°C (5 min); 10°C (hold). All PCR products were resolved on ~1% agarose gels stained with GelRed (Biotium, Cat. # 41003) using a 1-kb marker (NEB, Cat. # N3232L). Quantification of PCR products shown in Fig 4B was performed with a ChemiDoc MP Imaging System using the Image Lab Version 5.1 Relative Quantity Tool. Individual control and Ss-unc-22 site #3 bands from wild-type iL3s were randomly selected as reference bands. All other control and Ss-unc-22 site #3 reactions were compared to the appropriate reference to determine relative quantity of PCR products. For all samples, 25 μL of PCR product were loaded on the gel and all samples were run on the same gel.

Genotyping for Ss-unc-22 and Ss-tax-4 HDR

Primer sets used to test for HDR at Ss-unc-22 and Ss-tax-4 target sites can be found in S13 Table. PCR reactions for HDR of the repair template pEY09 at Ss-unc-22 site #2 and HDR of the repair template pMLC39 at Ss-tax-4 site #1 were performed with GoTaq G2 Flexi DNA Polymerase using the same thermocycler conditions outlined above, except for Ss-tax-4 genotyping, where the extension time was 2 min. PCR products were resolved on ~1% agarose gels stained with GelRed with a 1-kb marker. 5’ and 3’ integration bands for Ss-unc-22, and 5’ integration bands for Ss-tax-4, were gel-extracted using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Cat. # 28704) and subcloned into pGEM-T Easy (Promega, Cat. # A1360) for sequencing. PCR reactions to test for ssODN incorporation at Ss-unc-22 site #3 were performed with Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase (ThermoFisher Cat. # 10966018) using the same thermocycler conditions described for GoTaq. PCR products were resolved on ~1% agarose gels stained with GelRed using a 100-bp marker.

Restriction enzyme digestion to test for ssODN incorporation

The primer set used to amplify the region around Ss-unc-22 site #3 for ssODN EagI digest can be found in S13 Table. PCR cleanup on wild-type and unc iL3 pools was performed using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Cat. # 28104). For each sample, ~1 μg of template DNA was digested with EagI-HF (NEB, Cat. # R3505S) at 37°C for 1 h. Digested products were resolved on ~1% agarose gels stained with GelRed using 1-kb and 100-bp markers.

Illumina sequencing of S. stercoralis

Genomic DNA from populations of wild-type iL3s or Ss-unc-22-targeted F1 iL3s were collected as described above. 2x 150 paired-end Illumina libraries were prepared from 1 μg genomic DNA using the KAPA Library Preparation Kit with beads for size selection and sample cleanup (Kapa Biosystems, Cat. # KK8232). Libraries were sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq3000 platform using the HiSeq 3000/4000 PE Cluster Kit according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. Paired-end reads were mapped to the S. stercoralis reference genome using HISAT2 with the “—no-spliced-alignment” option [24,55]. To estimate read coverage, we performed a two-step approach. First, we computed per-site coverage using SAMtools for all sites that mapped to the reference. Second, to account for correlation between neighboring sites, we sampled 10,000 random sites to estimate coverage parameters under a negative-binomial distribution using custom Python and R scripts. The negative-binomial distribution is commonly used for modeling the random distribution of count data with an over-dispersion parameter and has been used in many bioinformatics pipelines to model read coverage [56]. We performed this second step to estimate genome-wide coverage parameters as well as parameters restricted to Ss-unc-22 sites. To compute the probability of observing coverage depletion at a given Ss-unc-22 target site by chance, we performed a one-tailed test under the Ss-unc-22-fitted negative binomial. To calculate indel frequency at Ss-unc-22 site #3, we took the mapped reads generated above and ran CRISPRessoWGS and CRISPRessoCompare with default parameters [29].

Fluorescence microscopy

unc F1 iL3s with a nicotine-twitching phenotype were transferred to a chemotaxis plate and screened for mRFPmars expression under a Leica M165 FC microscope. unc F1 iL3s expressing mRFPmars were mounted on a pad consisting of 5% Noble agar dissolved in ddH2O. Epifluorescence images were captured using a Zeiss AxioImager A2 microscope with an attached Zeiss Axiocam camera. Images were processed using Zeiss AxioVision software. After imaging, individual unc F1 iL3s were collected from agar pads and transferred to 5-6 μL of worm lysis buffer for HDR genotyping as described above.

Germline transmission of Ss-unc-22 mutations

A summary of Ss-unc-22 germline transmission strategies can be found in S7 Table. To generate an ~50/50 mix of wild-type and unc F1 iL3s, free-living adult females were injected with RNP complex targeting Ss-unc-22 site #3 with an ssODN. F1 iL3s were collected and a subset of them were screened in 1% nicotine assays to estimate the nicotine-twitching frequency; ~52% of iL3s contained putative Ss-unc-22 mutations based solely on phenotypic observation in nicotine. The remaining F1 population was injected into gerbil hosts. To enrich for unc F1 iL3s, RNP injections targeting site #3 were carried out as described for the 50/50 mixed infection. F1 iL3s were collected and all nematodes were screened in 1% nicotine assays. Nicotine-twitching iL3s were selected, washed in ddH2O, and recovered from nicotine treatment overnight. Paralyzed iL3s were discarded. unc F1 iL3s recovered from nicotine were injected into gerbil hosts. In the control infection, wild-type iL3s were treated with nicotine to induce paralysis, washed in ddH2O, and recovered from nicotine treatment overnight. Recovered wild-type iL3s were injected into gerbil hosts. Feces from all of the host infection strategies were collected as described above. F2 and F3 nematodes were screened for unc phenotypes using the nicotine, swimming, and crawling assays described above.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using standard statistical tests in GraphPad Prism Version 7.0. Deep-sequencing analysis was performed using custom Python and R scripts, and is described in detail above. The standard statistical tests used for all other experiments are described in the figure captions, and are also summarized below. For these experiments, the D’Agostino-Pearson omnibus normality test was first used to determine whether values came from a Gaussian distribution. If data were normally distributed, parametric tests were used; otherwise, non-parametric tests were used. A Mann-Whitney test or unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction was used to compare swimming and crawling behaviors in wild-type iL3s vs. unc iL3s (Figs 2, 6C and 6D). A chi-square test with Bonferroni correction or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare nicotine-induced twitching frequencies across genotypes or conditions (Figs 3 and 6B, S1, S2, S6 and S9 Figs). Depletion of Ss-unc-22 site #3 in unc iL3s was quantified using a two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post-test (Fig 4B).

Supporting information

Twitching frequency of C. elegans wild-type and unc-22 adults and dauers. Twitching frequency differs for C. elegans wild-type and unc-22 adults and dauers. *P<0.05, ***P<0.001, chi-square test with Bonferroni correction. n = 50–51 nematodes for each genotype and life stage.

(PDF)

(A) The unc-22 gene of S. ratti. The Sr-unc-22 gene structure depicted is based on the gene prediction from WormBase ParaSite [24,47]. The locations of the CRISPR target sites tested and predicted on-target activity scores are indicated [50]. Scale bar = 1 kb. (B) Twitching frequency of S. ratti wild-type iL3s and Sr-unc-22-targeted F1 iL3s following 1% nicotine exposure. For each condition, the Sr-unc-22 target site and delivery method of CRISPR constructs are indicated. Twitching frequency of F1 iL3s for each target site differs from wild-type iL3s and from each other. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, chi-square test with Bonferroni correction. n = 267–544 iL3s for each condition.

(PDF)

(A-B) Whole-genome sequencing coverage plots for Ss-unc-22 site #1 (A) or site #2 (B) from populations of either Ss-unc-22-targeted F1 iL3s from P0 females injected with RNP complexes for site #3, or wild-type iL3s. A 4-kb window centered on the predicted cut sites is shown [24,47]. Black lines = average coverage depth by position (reads per base); red lines = average genome-wide coverage; blue lines = average coverage for the Ss-unc-22 gene. Coverage around Ss-unc-22 sites #1 and #2 is not depleted in Ss-unc-22 libraries when Ss-unc-22 site #3 is targeted (P>0.05; see Methods). Similarly, no coverage depletion is observed in the wild-type library (P>0.05; see Methods). For B, the gray shaded region represents significant depletion around Ss-unc-22 site #3, which is only ~2.3 kb upstream of Ss-unc-22 site #2. The arrow indicates that site #3 is upstream of the 4-kb window shown.

(PDF)

Whole-genome sequencing coverage plots for a selected control gene, Ss-tax-4 (SSTP_0000981000) containing an unrelated predicted CRISPR target site. A 4-kb window centered on the predicted cut site is shown [24,47]. Black lines = average coverage depth by position (reads per base); red lines = average genome-wide coverage; blue lines = average coverage for the Ss-tax-4 gene. Coverage around Ss-tax-4 site #1 is not depleted in Ss-unc-22 libraries when Ss-unc-22 site #3 is targeted (P>0.05; see Methods). Similarly, no coverage depletion is observed in the wild-type library (P>0.05; see Methods).

(PDF)