Abstract

In this study, chemical modification of 2′-deoxyinosine (2′-dI) and D-/L-isothymidine (D-/L-isoT) was performed on AS1411. They could promote the nucleotide-protein interaction by changing the local conformation. Twenty modified sequences were obtained, FCL-I and FCL-II showed the most noticeable activity improvement. They stabilized the G-quadruplex, remained highly resistant to serum degradation and specificity for nucleolin, further inhibited tumor cell growth, exhibited a stronger ability to influence the different phases of the tumor cell cycle, induced S-phase arrest, promoted the inhibition of DNA replication, and suppressed the unwound function of a large T antigen as powerful as AS1411. The microarray analysis and TaqMan PCR results showed that FCL-II can upregulate the expression of four breast-cancer-related, lowly expressed miRNAs and downregulate the expression of three breast-cancer-related, highly expressed miRNAs (>2.5-fold). FCL-II resulted in enhanced treatment effects greater than AS1411 in animal experiments (p < 0.01). The computational results further proved that FCL-II exhibits more structural advantages than AS1411 for binding to the target protein nucleolin, indicating its great potential in antitumor therapy.

Keywords: AS1411, isonucleoside, 2'-deoxyinosine, biological regulation, tumor suppressor

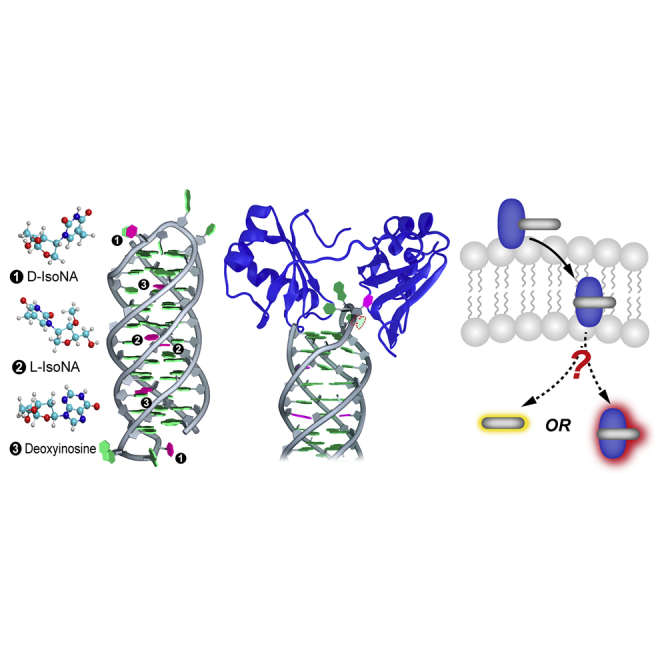

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

G-quadruplexes are nucleic acid secondary structures rich in guanine. Through the systematic search for the existence of potential G-quadruplex-forming sequences in the human genome, over 370,000 putative G-quadruplex have been found.1 G-quadruplexes are significantly associated with the regulation of various physiological and pathological pathways, such as cell differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis, especially in the different key steps of genetic regulation, including DNA replication, genetic transcription, mRNA translation, and epigenetics.2, 3, 4 Since nucleic acids like G-quadruplexes were discovered, they were only considered to be the genetic carrier of living beings; only later did scientists find out that DNA and RNA were widely involved in biological functions. Therefore, scientists began to consider how to imitate gene sequences with biological activity in vivo to build nucleotide sequences in vitro that have the same biological activity. As a result, SELEX (systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment) and aptamers were developed.

Aptamers are short synthetic single-stranded oligonucleotides (oligo) that specifically bind to various molecular targets, such as small molecules, proteins, nucleic acids, and, even, cells or tissues.5, 6, 7 Known as chemical antibodies, aptamers can fold into diversified three-dimensional structures and bind to target molecules and thus could be further developed as novel agents in both molecule sensing8, 9 and targeted cancer imaging and therapy.10 Aptamers are generally selected using SELEX, which was first independently reported by two groups in 1990.11

Natural aptamers screened from SELEX usually have long sequences and poor druggability.12 Thus, the appropriate chemical modification was requisite to improve their chemical and biological properties, which is known as Post-SELEX. Many types of chemical modifications have been developed, including nucleobase,13 sugar ring14 and backbone15, 16 modification, aiming at improving nuclease resistance, pharmacokinetic properties and activity.

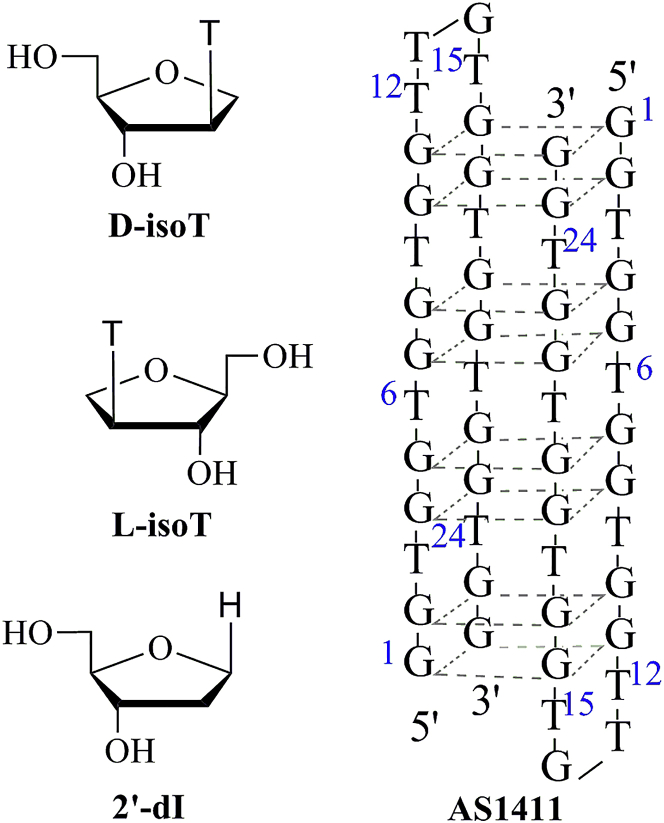

Isonucleosides (IsoNA) (Figure 1) are a novel type of nucleoside analog in which the nucleobase is linked to another position of the ribose other than C-1′, to be precise, C-2′ in our research.17 Previous work has shown that D-/L-isoNA incorporated at the proper sites in oligos can increase the activity of antisense nucleotides, DNAzyme, small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), and aptamers.18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 Furthermore, as a naturally occurring base, 2′-deoxyinosine (2′-dI) (Figure 1) offers a huge advantage in non-immunogenic clinical application.25 With this strategy, the local spatial conformation, especially around the incorporation site, could be properly optimized, resulting in enhanced bioactivity.

Figure 1.

The Structure of D-/L-isoT, 2′-dI, and Quadruplex Structure of AS1411

2′-dI, 2′-deoxyinosine.

AS1411 (Figure 1) is a 26-base G-quadruplex oligo-targeting nucleolin. As many other G-rich oligos, AS1411 is endowed with superior antitumor activity.26, 27 High levels of nucleolin expression are closely related to the rapid proliferation of cancer cells.28 The biological effects of AS1411 include the inhibition of cell proliferation, S-phase cell-cycle arrest, DNA replication block, interference with the molecular interactions and functions of nucleolin, and other unknown effects.29, 30 A phase ІI clinical trial31 of AS1411 was shut down because of bone marrow suppression and low response to treatment. Chemical modification of AS1411 was rarely reported. Incorporation of 5-(N-benzylcarboxyamide)-2-deoxyuridine at T24 could significantly increase the targeting affinity to cancer cells.32 Replacement of G10 by thymidine and the addition of a thymidine at both terminals of AS1411 results in a novel aptamer AT11 and maintains the antitumor activity with a left-handed G-quadruplex, which differs from those well-known aptamers with right-handed G-quadruplexes.33, 34 Based on previous work done by our team, we tried to find a type of modification that could enhance the bioactivity of AS1411 by changing the local space conformation and further reveal the regulatory mechanisms of modified AS1411.

Because of its important biological function, understanding the detailed structure of AS1411 is necessary for further studies. The topology and molecular structure of AS1411 has been characterized by several methods,35 but the G-quadruplex structure has not been successfully solved by X-ray crystallography or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). In our previous studies, simulated complex models have been successfully built to investigate the critical interactions in the binding process.25

In this study, to improve the bioactivity of AS1411, D-/L-isoT, and 2′-dI were incorporated in AS1411 with options. To elucidate the antiproliferative activity of AS1411 and its possible mechanism, a cell growth assay, a DNA synthesis assay, cell-cycle progression, a helicase assay, and a microarray were carried out. In addition, the targeting affinity with nucleolin protein was directly probed using surface plasmon resonance (SPR). Circular dichroism (CD) spectra were collected to determine the effect of D-/L-isoT and 2′-dI substitutions on the structure of the AS1411 variants. A serum degradation assay was conducted to verify the stability of the aptamers, and animal experiments were performed to evaluate their antitumor effects in vivo. To probe the structural characteristics and molecular recognition process, a molecular dynamics (MD) simulation was performed using the complex structure of the modified aptamer and nucleolin RNA binding domain (RBD12).

Results

Single D-/L-isoT Modification Inhibited the Proliferation of MCF-7 Cells

To screen the suitable modification site, all non-guanosine sites were randomly substituted with D-/L-isoT. The sequences are listed in Table 1. To determine the effects of the modifications, cell growth assays were performed, and the CD spectra were taken. We tested the effects of isoT-modified AS1411 on the growth of MCF-7 cells in culture (Figure S1). AS1411-6L and AS1411-12D caused a great reduction in the proliferative rate of the cells compared to AS1411 as a control.

Table 1.

The Sequences of AS1411 and D-/L-isoT (TD/TL) and/or 2′-dI Incorporated AS1411s

| No. | Name | Sequence (5’-3’) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | AS1411 | ggt ggt ggt ggt tgt ggt ggt ggt gg |

| 2 | 3L | ggTL ggt ggt ggt tgt ggt ggt ggt gg |

| 3 | 3D | ggTD ggt ggt ggt tgt ggt ggt ggt gg |

| 4 | 6L | ggt ggTL ggt ggt tgt ggt ggt ggt gg |

| 5 | 6D | ggt ggTD ggt ggt tgt ggt ggt ggt gg |

| 6 | 9L | ggt ggt ggTL ggt tgt ggt ggt ggt gg |

| 7 | 9D | ggt ggt ggTD ggt tgt ggt ggt ggt gg |

| 8 | 12L | ggt ggt ggt ggTL tgt ggt ggt ggt gg |

| 9 | 12D | ggt ggt ggt ggTD tgt ggt ggt ggt gg |

| 10 | 13L | ggt ggt ggt ggt TLgt ggt ggt ggt gg |

| 11 | 13D | ggt ggt ggt ggt TDgt ggt ggt ggt gg |

| 12 | 15L | ggt ggt ggt ggt tgTLggt ggt ggt gg |

| 13 | 15D | ggt ggt ggt ggt tgTDggt ggt ggt gg |

| 14 | 18D | ggt ggt ggt ggt tgt ggTL ggt ggt gg |

| 15 | 18L | ggt ggt ggt ggt tgt ggTD ggt ggt gg |

| 16 | 21D | ggt ggt ggt ggt tgt ggt ggTL ggt gg |

| 17 | 21L | ggt ggt ggt ggt tgt ggt ggTD ggt gg |

| 18 | 24L | ggt ggt ggt ggt tgt ggt ggt ggTL gg |

| 19 | 24D | ggt ggt ggt ggt tgt ggt ggt ggTD gg |

| 20 | FCL-I (6L/12D) | ggt ggTL ggt ggTD tgt ggt ggt ggt gg |

| 21 | FCL-II (6L/12D/24dI) | ggt ggTL ggt ggTD tgt ggt ggt ggdI gg |

Combined Modification of D-/L-isoT and 2′-dI Can Further Enhance the Biological Effects of the Aptamer

Based on our previous experiences, selectively combinations of activity-enhanced sites are more likely to further improve the performance of the aptamer.22, 23, 24 Additionally, 2′-dI offers a huge advantage for diagnostic utility, and when 2′-dI is incorporated at position 24, it can enhance the bioactivity of AS1411. To further optimize AS1411, we incorporate isoT at the 6th and 12th positions simultaneously (FCL-I). We also incorporated 2′-dI at position 24 of FCL-I (FCL-II) in hopes that FCL-II could materialize the advantageous complementarities of 2′-dI and isoT.

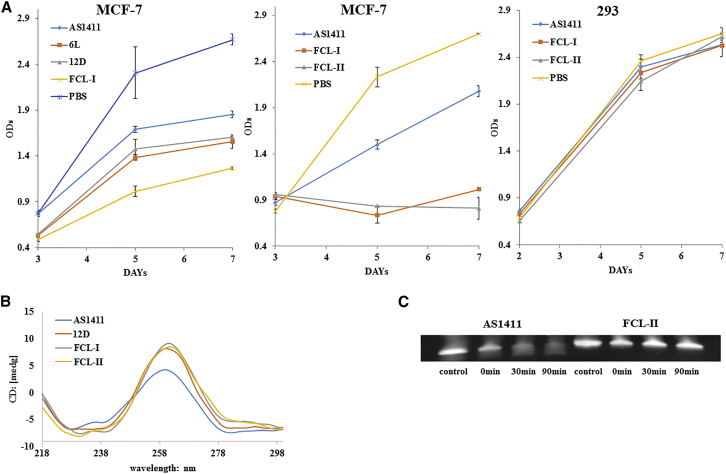

We tested the effects of FCL-I and FCL-II on the growth of MCF-7 and HEK293 cells in culture to directly evaluate their ability to inhibit cellular proliferation. Figure 2A shows the results of the CCK-8 assays. MCF-7 cells with FCL-I had fewer numbers of viable cells than those treated with AS1411-6L or AS1411-12D. This result indicated that FCL-I can suppress human breast cancer cell proliferation in a more potent way. The same experiment at the cellular level was repeated with FCL-II. The CCK-8 assay showed that the anticancer effects of FCL-II on the MCF-7 cells were similar to that of FCL-I during 3 to 5 days after administration, while the effect of FCL-II was slightly greater than FCL-I at 7 days after administration. Both FCL-I and FCL-II had little impact on HEK293 cells.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of Tumor Cell Proliferation, Circular Dichroism, and Serum Stability of Modified Sequences

(A) CCK-8 assays showing the growth of the 2 cell lines treated with 6L, 12D, FCL-I, FCL-II, or PBS as a control. The oligonucleotides (or PBS as control) were directly added to the culture medium to yield a final concentration of 7.5 μM (day 1). On days 2–4, the further addition of the oligonucleotide equivalent to half the initial dose was added. The cells were assayed using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) (Dojindo Laboratorie, Japan) on 3, 5, and 7 days after treatment. The optical density 450 (OD450) nanometer value is proportional to the number of viable cells in the sample. (B) The CD data were obtained for the aptamers at 5 μM in 10 mM PBS at pH 7.0 containing 0.1 M KCl. All aptamers were boiled for 5 min and annealed at 60°C for 50 hr. (C) The degradation of aptamers exposed to 50% fetal bovine serum at 37°C for 90 min and the undegraded, intact aptamers were resolved on 20% polyacrylamide gels and visualized with SYBR staining. The results are shown as a mean of three separate experiments with SD.

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra provide reliable information for identifying DNA structures, including the G-quadruplex structure. AS1411 has a positive ellipticity maximum at 264 nm and a negative ellipticity minimum at 240 nm.36 The CD spectra for AS1411 and modified AS1411 were obtained to investigate the impact of D-/L-isoT on the overall structure of AS1411. The results (Figure 2B) showed that all modified aptamers, AS1411-12D, FCL-I, and FCL-II, had a higher positive ellipticity maximum in their circular dichroism spectra. The intensity of the CD bands was increased, especially the positive band at approximately 264 nm, which suggested that D-/L-isoT could change the local space conformation for the formation of the stable G-quartet.

Nucleolin is an abundant, multifunction 110-kDa phosphorprotein, and it is thought to be located predominantly in the nucleolus of proliferating cells.37 The activity of AS1411 is known to correlate with its ability to bind to nucleolin protein. SPR was used to study the binding of AS1411 with nucleolin. Table 2 shows the dissociation constant values of natural AS1411 and D-/L-isoT-modified AS1411. All D-/L-isoT-modified AS1411 constructs showed a significant improvement in their affinity for nucleolin. FCL-II had the highest dissociation constant values for nucleolin. These results demonstrated that our modification strategy can improve the binding force of AS1411 at the molecular level.

Table 2.

The Binding Parameters for the Affinity of D-/L-isoT and 2′-dI Modified AS1411 for Nucleolin

| Aptamer | KD (nM) |

|---|---|

| AS1411 | 148.0 |

| 12D | 31.9 |

| FCL-I | 9.56 |

| FCL-II | 4.70 |

AS1411 with stable G-quartets was resistant to degradation when placed in serum-containing medium.38 A serum degradation assay was performed to ensure aptamer stability. The results showed that (Figure 2C) FCL-II had much better stability in fetal bovine serum.

FCL-I and FCL-II Had More Remarkable Biological Control on Tumor Cell Cycle and DNA Replication

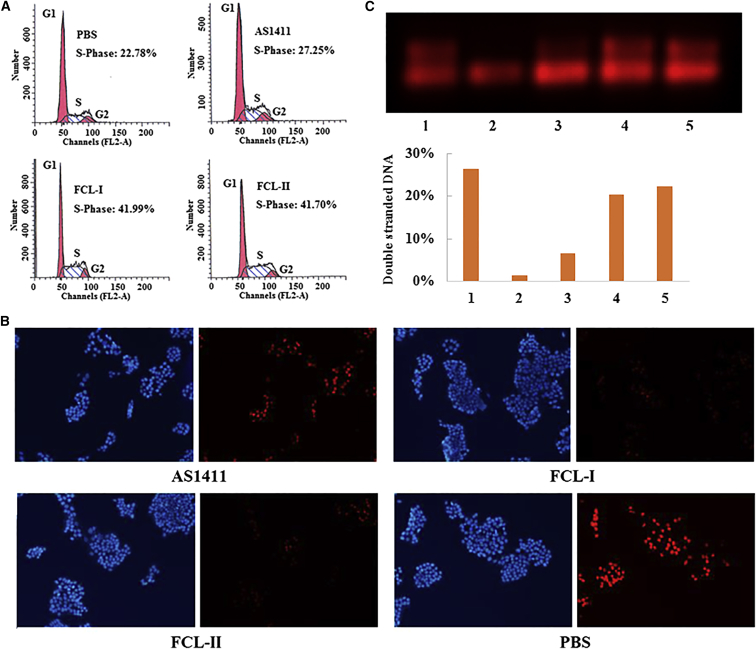

FCL-I and FCL-II had a higher ability to inhibit MCF-7 cellular proliferation. Thus, flow cytometry analysis of propidium iodide-stained nuclei of FCL-I- and FCL-II-treated cells were carried out to confirm whether they were associated with cell-cycle interference. As the experimental results (Figure 3A) suggested, FCL-I and FCL-II significantly changed the cell-cycle distribution and arrested cells in S-phase. Additionally, the change degree was higher than cells treated with natural AS1411. This result concluded that the ability of AS1411 to inhibit cellular proliferation is correlated with their ability to induce S-phase cell-cycle arrest.

Figure 3.

S-phase Cell-Cycle Arrest and Inhibition of DNA Replication by FCL-I and FCL-II

(A) The flow cytometric analysis of the S-phase fractions of the cells following 72 hr of treatment with AS1411, FCL-I, FCL-II, or PBS as a control. The identity of the cell line is indicated above each histogram. The cells were treated by the direct addition of the oligonucleotide to the culture medium at a final concentration of 10 μM. The percentage of cells in S-phase was determined using the Modfit program. (B) Cells were treated with a final concentration of aptamer at 18 μM for 72 hr and then exposed to 50 μM of EdU for 2 hr at 37°C. The DNA was stained with 5 μg/mL of Hoechst 33342 (50 μL per well) for 30 min and imaged under a fluorescent microscope. Blue indicates the whole DNA in cell nucleus, and red indicates that de novo DNA synthesis occurred in these cells visualized by EdU. (C) 55A was annealed (95°C for 5 min followed by slow cooling to room temperature) to Cy5-labeled 55B to form the synthetic replication. SV40 large T antigen (Chimerx, Milwaukee, WI) was used to unwind the substrate in the absence or presence of the aptamer AS1411 or FCL-II. SV40 large T antigen was preincubated for 15 min at 37°C in working buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, 7 mM MgCl2, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 5 mM ATP, and 25 g/mL bovine serum albumin) prior to its addition. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 3 hr at 37°C before being terminated by the addition of stop buffer (200 mM EDTA, 40% glycerol, and 0.6% SDS). The samples were resolved using a 2.0% agarose gel and fluorescently imaged using the Maestro 2 multispectral imaging system (CRi Maestro). 1, double strands as control; 2, single strand as control; 3, double strands + large T antigen; 4, double strands + large T antigen + AS1411, and 5: double strands + large T antigen + FCL-II.

The major event in S-phase is DNA replication. Thus, we analyzed the DNA replication in cells treated with FCL-I and FCL-II. This was achieved by determining the level of incorporation of EdU (5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine). EdU is a nucleoside analog of thymidine that is incorporated into DNA during active DNA synthesis only by proliferating cells. After incorporation, a fluorescent molecule that reacts specifically with EdU was added, making it possible to directly visualize the fluorescence of proliferating cells.39 The DNA synthesis assay (Figure 3B) showed that FCL-I and FCL-II led to a significant reduction in red staining in MCF-7 cells than AS1411. Thus, the weaker staining by EdU indicated that less de novo DNA synthesis was occurring in these cells.

DNA replication begins when helicase unwinds DNA at the replication fork. Previous studies have reported that large T antigen has DNA unwinding activity and can unwind both double-stranded DNA and G-quadruplexes.40 A helicase assay was used to reveal the influence of the presence of AS1411 or FCL-II on unwinding activity. Figure 3C showed that both AS1411 and FCL-II were active in inhibiting unwinding by large T antigen. Large T antigen can reduce the percentage of double stranded DNA from 26% to 7%, while AS1411 and FCL-II can recover its level to 20% and 22%, respectively. The results revealed a good correlation between the inhibition of helicase activity and the inhibition of DNA replication.

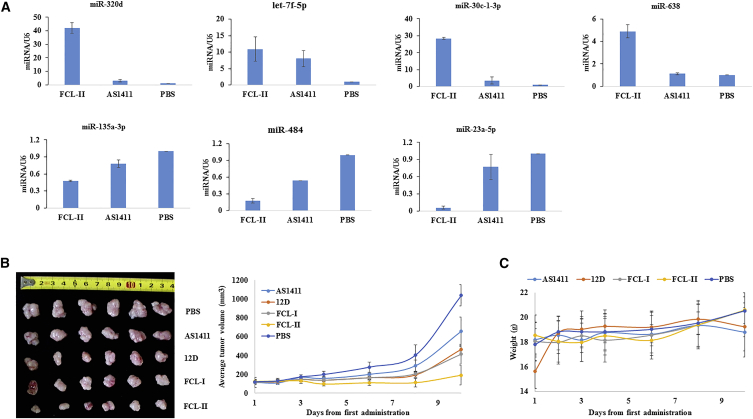

FCL-II Modulated the Expression of 7 Specific MicroRNAs That Are Associated with Breast Cancer

Nucleolin is a major nucleolar protein that post-transcriptionally regulates the expression of a specific set of miRNAs that are causally involved in breast cancer initiation, progression, and drug resistance.41 We combined the results from the microarray analysis and quantitative real-time PCR results (TaqMan PCR) (Figure 4A) to determine the extent that FCL-II modulates miRNA expression. The two approaches showed that a common core of 7 mature miRNAs that were more specifically modulated by FCL-II. FCL-II can further upregulate the expression of four breast-cancer-related lowly expressed miRNAs, including miR-320d, let-7f-5p, miR-30c-1-3p, and miR-638, compared to AS1411.42, 43, 44, 45 Similarly, FCL-II also can further downregulate the expression of three breast-cancer-related highly expressed miRNAs, miR-135a-3p, miR-484, and miR-23a-5p, compared to AS1411 (>2.5-fold).46, 47, 48

Figure 4.

Modulation of MicroRNA Expression by FCL-II and Suppression Effect of FCL-I/II on MCF-7 Xenografts

(A) For TaqMan PCR, the total RNA was isolated using the mirVana miRNA Isolation Kit (Life Technologies Corporation, USA). RT-PCR was performed using the TaqMan MicroRNA Assay (Life Technologies Corporation, USA) and the Mx3005P QPCR System (Agilent Technologies, Inc., CA, USA). U6 gene quantification was used as the control. The results are shown as a mean of three separate experiments with SD. (B) Bilaterally ovariectomized female athymic nude mice (BALB/c/Nu/Nu) were subcutaneously inoculated with MCF-7 cells at the age of 4 weeks. Treatment of mice with established tumors by an intraperitoneal injection of aptamers at doses equivalent to approximately 3 OD/mice/day daily for the first 5 days and an additional treatment at day 7 for a total of 6 injections was performed. The tumor volume was calculated using the formula (1/2 × L × W2). Above, the tumor measurement was made after the mice were sacrificed. The results are shown as a mean of six separate experiments with SD. (C) The body weights of the mice were measured daily, and the results are shown as a mean of six separate experiments with SD.

FCL-II Resulted in a Stronger Growth Suppression Effect on MCF-7 Xenografts Than AS1411

Since our in vitro studies revealed the significant suppression of human breast cancer cell proliferation and viability, we next evaluated the effect in vivo. To this end, FCL-I and FCL-II activity were confirmed in nude mice bearing MCF-7 xenografts. As shown in Figure 4B, the effect of the aptamers on cancer growth was shown by delaying an increase in the volume of the cancers. The average tumor volumes in the FCL-II group were consistently and significantly lower than that in the FCL-I and control groups (p < 0.01 versus AS1411 control). We showed that FCL-II suppressed human breast cancer growth, both in vitro and in vivo, more effectively than natural AS1411. At the same time, the weights of the nude mice were examined to ensure that aptamers had no apparent toxicity (Figure 4C). The aptamers had no in vivo toxicity in the rodents.

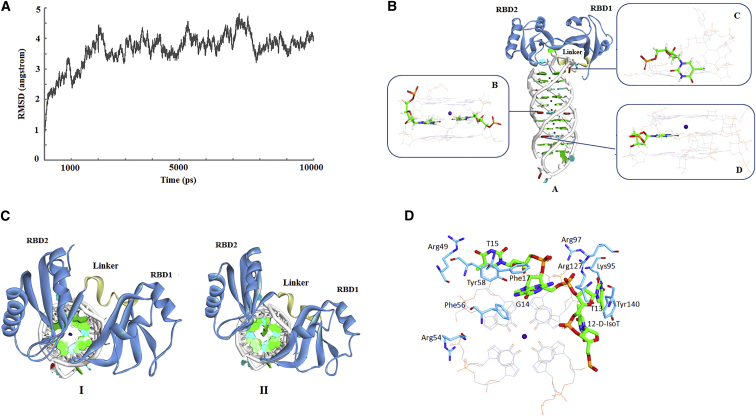

Structure Stability Analysis

To assess the overall structural stability of the modified sequences with RBD12 domain of nucleolin, the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) profiles, with the initial structure as a reference, were analyzed along the trajectories. As shown in Figure 5A, the RMSD for the whole structure slowly increased and then tended to converge, indicating the system was stable. Of note, the RMSD displayed oscillations in some regions during the simulation. The visual inspection of the trajectory clearly showed that the mobility was attributed to the flexibility of the two loop regions of RBD12, which should be connected to the other domain of nucleolin. Actually, we have previously observed similar conformation changes in other simulated complexes.20 However, these fluctuations did not have any significant impact on the binding site.

Figure 5.

Computational Simulation of FCL-II with Nucleolin

(A) The RMSD curve for the whole complex structure of FCL-II and RBD12 during the MD simulation. (B) The average structure of FCL-II and RBD12 from the MD simulation. A: the overall complex structure. The residues at positions 6, 12, and 24 are colored red. B: the partial enlarged drawing of site 12. D-isoT is represented as sticks. C: the partial enlarged drawing of site 6. L-IsoT is represented as sticks. D: the partial enlarged drawing of site 24. 2′-dI is represented as sticks. (C) The top views of the complex structures. I: FCL-II and RBD12. II: Native AS1411 and RBD12. (D) The binding mode analysis of FCL-II and RBD12. Protein residues (blue) and nucleotides (green) making favorable interactions are represented as solid sticks with black labels. Green dashes represent hydrogen bonds.

Overall Structure and Binding Mode Analysis

The computational complex structure represents a paradigm in the understanding of structural variations and how modified aptamers interact with nucleolin. Therefore, the whole averaged structure over the last 2 ns of the MD simulation was extracted (Figure 5BA) for the subsequent analysis. After the simulation, FCL-II had an antiparallel G-quadruplex similar to natural AS1411 and formed a stable complex structure with RBD12. Our aim was to design a type of chemical modification that could enhance aptamer bioactivity by (1) changing the local conformation to enlarge the interface or (2) improving the stability of the G4 structure. As expected, these findings are agreed with our previously described CD results. Moreover, a comparison of AS1411-RBD12 with the modified complexes revealed several interesting structure features. Of note, a noticeable movement of the whole protein structure was observed in all the modified systems. As shown in (Figure 5C), the distance between RBD1 and RBD2 was decreased, and the contacts were increased, giving rise to a more compact and stable complex. Upon binding, FCL-II underwent slight structural rearrangements, particularly in the loop region (nucleotides 12–15 from 5′). However, the manner in which aptamers recognized RBD12 was similar, as they retained the same loop backbones.

Among all three replacing sites, only position 12 was involved in the binding interface, while both positions 6 and 24 are located in the middle of the G4 structure. Indeed, thymidine at positions 6 and 24 form stacking interactions with the adjacent G-quartets, whereas thymine adopts an extended conformation at position 12. Commonly, the extended conformation can lead to a large interface that is favorable for binding. In contrast, D-IsoT at position 12 displayed a partially folded conformation that could facilitate the formation of G4 (Figure 5BB). Furthermore, it should be noted that this modification has changed the other base orientations in the loop region, especially those of T13 and G14. The detailed structure variations will be discussed in the binding mode analysis section. In addition, with respect to the unmodified AS1411, the base orientation of L-IsoT flipped at position 6 and formed new hydrogen bond with the adjacent T (Figure 5BC). For the 2′-dI, the larger aromatic ring at position 24 increased the stacking interactions, and similar results were also obtained when it was incorporated at positions 15 and 24 (Figure 5BD).25 Apparently, modification at positions 6, 12, or 24 did not have direct effects on the binding process, but this is likely to contribute to the stability and changes in the local conformation of the G4 structure to some extent.

In the following study, we analyzed the binding mode of FCL-II taken from the MD trajectory during the last 2 ns. Special attention was devoted to investigating the RBD12-loop (nucleotides 12–15 from 5′) interactions that are decisive for molecular recognition (Figure 5D). As described previously, recognition primarily involves the protein residues Arg97, Arg127, Arg49, Tyr58, Phe56, and Tyr140. However, in natural AS1411, G14 in the anti-conformation has been reported to form π-π stacking interactions with Phe56. In FCL-II, similar interactions between G14 with a syn conformation and Phe17 were observed. Moreover, the gap formed by the anti-syn conversion was occupied by the protein residues from RBD1 and RBD2. In comparison to unmodified AS1411, T13 moved close to the protein, and the π-π stacking interaction with Tyr140 was lost. This led to a tight packing interface. In terms of T15, it preserved those contacts similar to natural AS1411. In addition, Arg54 was initially not in contact with AS1411. However, in FCL-II, a strong ion pair interaction was established with G26. This phenomenon has also been observed in our previous studies when 2′-dI was incorporated at positions 15 and 24.25 Although the binding mode does not cause drastic structural changes upon substitutions, these changes led to new structure features. These additional interactions provide a good explanation for the improved bioactivity of FCL-II.

Discussion

Although researchers have made some progress with aptamers, there have been no aptamers approved for sale after Macugen, the first aptamer compound approved for the treatment of age related macular degeneration in December 2004. It is worth noting that Macugen is chemically modified and contains both 2′-F and 2′-OMe modifications and the attachment of a 40-kDa polyethylene glycol.49 Macugen is also lately explored for its application in diabetic macular edema,50 ischemic diabetic macular edema51 and myopic choroidal neovascularization.52 Recently, a new monoclonal antibody (ranibizumab, Novartis) drug was approved by FDA in 2015 and is now in clinical use to compete with Macugen.53 Since naked nucleic acid drugs are easily degraded by nuclease, unstable in blood and hard to pass the cell membrane, the administration method of the 6 FDA-approved oligo drugs so far were either vitreous injection (Fomivirsen and Macugen), intrathecal injection (Nusinersen), targeting blood component (Defibrotide) to avoid drug delivery process or apply large dose to fulfil therapeutic effect (Mipomersen and Eteplirsen) accompanied by side effect such as liver toxicity. Although aptamers showed advantages over antibody with lower toxicity, smaller size, and less immune reaction, chemical modifications to increase their affinity, specificity, and enzymatic stability must still be explored, together with effective delivery technologies.

Though some chemical modifications for aptamers have been developed, most are for nuclease resistance, chemical dressing, increasing bioavailability or reducing renal clearance, seldom can increase affinity for a target.54 Therefore, it is urgent to develop a universal modification that can increase the functions of aptamers. Based on the data presented herein, the combined use of D-/L-isoT and 2′-dI as a new aptamer modification strategy can strengthen the chemical stability and biological effects of the aptamer by changing the local space conformation. 2′-dI has larger steric structure, while isomeric D-/L-isoNA could change the orientation of the bases. Based on experimental results, D-/L-isoT increased the aptamer activities in a stronger way. We have used D-/L-isoNA to modify more than 5 different aptamers, including TBA,21 AS1411,25 GBI-10,22, 23, 24 BC-15, and DT-2 (unpublished data). Some of these are G-quadruplexes, and some are not. However, all showed stronger activity after modification. In our view, this would be relevant to the unique configuration of the enantiomer D-/L-isoT. Further studies will improve our understanding of the impact of D-/L-isoNA.

According to our systematic investigations, G-quadruplex is a necessary prerequisite for the binding process, and the target protein can induce the formation of the active conformation. Modifications that are disadvantageous for the formation of the G-quadruplex led to decrease in activity. Apparently, the loop region plays a key role in the process of binding with protein, especially for the conformation. If it is modified correctly, the activity increased, such as for FCL-II, but when the loop conformation changes too drastically, the activity decreases. We first revealed the binding mode and interactions between FCL-II and nucleolin using a computer simulation technique. MD simulations clearly demonstrated that FCL-II can form new interactions with nucleolin via adopting different loop conformations. Apart from the loop, other non-quartet thymine residues are not directly involved in the binding interface, but there are some sites that are critical for the folding mechanism and stability, such as sites 6 and 24. It can be inferred that with the same loop conformation, the stability of the G-quadruplex is positively correlated with its activity.

Aptamers play very important roles in physiological and pathological pathways as powerful immune response modulators that bind to co-stimulatory receptors,55 as riboswitches to control transcription,56 and as mimics of proteins that modulate the function of their target proteins.57 As a G-quadruplex aptamer, AS1411 has broad regulation functions.58, 59, 60 Previous research has shown that besides antiproliferative effects, AS1411 has an important function in shutting the PRMT5-nucleolin complex, sequestering the NEMO-nucleolin complex, binding nucleolin to the mRNA of bcl-2, reducing the levels of NCL-dependent miRNAs and their target genes, and stimulating macropinocytosis through a nucleolin-dependent mechanism.61 However, many details of its mechanisms need to be explored, including the different binding modes with nucleolin, the location of its regulation processes, whether AS1411 or a AS1411-nucleolin complex has biological activity, and other unknown regulatory effects. In this study, we focused on the interaction between AS1411 and a key enzyme in DNA replication, DNA helicase. Additionally, we found AS1411 can modulate the levels of breast-cancer-specific miRNAs. Nucleolin is a RNA-binding protein, and its expression affects the biogenesis of a specific cohort of miRNAs.62 Our data suggest the direct involvement of AS1411 in miRNA biogenesis. Deep research of the mechanism will be pursued and such chemically modified aptamers could be used as valuable clinical tools in the identification of cancer at very early stages and in cancer therapy.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Treatment

These studies were supervised by the Peking University biomedical ethics committee. Cells were cultured in a humidified incubator maintained at 37°C in 95% air/5% carbon dioxide. MCF-7 human breast cancer cells were cultured in DMEM (M&C Gene Technology) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Thermo Scientific). HEK293 cells were cultured in DMEM (M&C Gene Technology) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Thermo Scientific). All experiments were performed with cells in the exponential growth phase. The aptamers were dissolved in PBS (M&C Gene Technology, China) before addition to the cell cultures.

Solid-Phase Synthesis of Aptamers

D-/L-isoT phosphoramidite was synthesized by our lab according to the literature,20, 63 and all the modified AS1411s were synthesized using an ABI 394 automated DNA/RNA synthesizer using standard phosphoramidite chemistry. All the modified AS1411s were purified with C18 reverse high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC; X-bridge C18, 4.6 × 50 mm) using a linear gradient of 5%–70% eluent A in 40 min. Solutions of 0.1 M Et3N-CH3COOH in water at pH 7.7 were used as eluent B, and CH3CN was used as eluent A. Then the isolated DMT-on oligos were treated with 80% acetic acid for 10 min at room temperature. After neutralization with Et3N, the oligo solutions were desalted using a Sephadex G25 column. The purity of all oligos was over 90% and confirmed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (MS) (Figures S13–S34; Supplemental Information).

Circular Dichroism Study

The oligos at a final concentration of 5 μM were resuspended in 10 mM PBS (pH 7.0, containing 0.1 M KCl), heated for 5 min, and annealed at 60°C for 50 hr. When protein was added, the oligos (5 μM) and protein (0.5 μM) were dissolved in PBS (M&C Gene Technology) and incubated at 37°C for 0.5 hr. The samples were analyzed on a Jasco J-610 (Japan) spectropolarimeter using 0.5-mL quartz cuvettes with a 2-mm path length.

Cell Growth Assay

The cells were plated at a density of 1.5 × 103 cells/well in the appropriate serum-supplemented medium in a 96-well plate. After 16 hr of incubation to allow the adherence of the cells, the oligos (or PBS as control) were directly added to the culture medium at a final concentration of 7.5 μM (day 1). On days 2–4, the further equivalent of oligo at half the initial dose was added. The cells were assayed using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) (Dojindo Laboratorie, Japan) on several days after plating. The culture medium was not changed throughout the duration of the experiment.

SPR

SPR experiments were performed on a Biacore 3000 (Piscataway, NJ) at 25°C. Nucleolin proteins (Abcam, Hong Kong) were immobilized on CM5 sensor chips using PBS-EP (0.01 M HEPES, 0.15 M NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, and 0.005% Surfactant P20 at pH 7.4), filtered, and degassed before use. The aptamers were injected onto a pre-activated sensorchip surface for 45 s at a flow rate of 30 μL/min. After each run, the surface was regenerated with 5 mM aqueous NaOH for 10 s at 30 μL/min. The binding curves were fitted using a 1:1 Langmuir binding model; if feasible, the equilibrium dissociation constants were calculated using the BIAevaluation software (v.4.0).

Serum Degradation Assay

Serum degradation assays were performed by incubating 1 μL of 20 μM aptamers in 50% fetal bovine serum at 37°C for 90 min. Aliquots of 10 μL were collected after being treated for 30 or 90 min. Then the solution was immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until analyzed. Together with 3 μL of 6× DNA loading buffer, all the samples were resolved on 20% polyacrylamide gels and visualized by SYBR.

Flow Cytometry Analysis of the Cell Cycle

The cells were plated at a density of 105 per well in a 6-well plate. After incubation at 37°C overnight to allow for adherence, the cells were treated by the direct addition of the oligo to the culture medium to yield a final concentration of 10 μM. At 72 hr after treatment started, the cells were harvested by trypsinization, fixed, and stained with propidium iodide (M&C Gene Technology, China). The cells were then analyzed using a BD FACSCalibur cytometer. The percentages of cells in the G1/G0, S, and G2/M phases were determined using the Modfit program.

DNA Synthesis Assay

The cells were plated at a density of 1.5 × 103 cells per well in a 96-well plate. They were incubated overnight and then treated by the direct addition of the oligo to the culture medium at a final concentration of 18 μM (or untreated samples received an equal volume of PBS). 72 hr after treatment started, the cells were assessed using an EdU incorporation assay (Ribobio, Guangzhou, China). The cells were exposed to 50 μM EdU for 2 hr at 37°C, then fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature, and permeabilized in 0.5% Triton X-100 for 10 min. Then they were washed with PBS, and each well was incubated with 100 μL of 1× Apollo reaction cocktail for 30 min. The DNA was then stained with 5 μg/mL of Hoechst 33342 (50 μL per well) for 30 min and imaged using a fluorescent microscope (Olympus IX81, Japan).

Helicase Assay

This assay was carried out according to the method of Choi et al.26 The oligo 55A (5-TGA AGG TTT CGA ATC AGA GGT AGG TGC CCG GCC TCC AAC TTG CCG TAT TCC TGG T) was annealed (95°C for 5 min followed by slow cooling to room temperature) to the Cy5-labeled partially complementary oligo Cy5-labeled 55B (5-ACC AGG AAT ACG GCA AGT TGG AGG CCG GGC TGG ATG GAG ACT AAG CTT TGG AAG T-Cy5) to form the synthetic replication. SV40 large T antigen (Chimerx, Milwaukee, WI) was used to unwind this substrate in the absence or presence of the aptamer AS1411. SV40 large T antigen was preincubated for 15 min at 37°C in working buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, 7.0 mM MgCl2, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 5 mM ATP, and 25 g/mL bovine serum albumin) prior to the addition. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 3 hr at 37°C before being terminated by the addition of stop buffer (200 mM EDTA, 40% glycerol, and 0.6% SDS). The samples were resolved on a 2.0% agarose gel and fluorescently imaged using the Maestro 2 multispectral imaging system (CRi Maestro).

Microarray and TaqMan PCR

MCF-7 cells were plated at a density of 5 × 105 cells/well in the appropriate serum-supplemented medium in a 6-well plate. After 16 hr to allow for the adherence of the cells, oligos (or PBS as control) were directly added to the culture medium at a final concentration of 20 μM. 72 hr after treatment was initiated, the cells in TRIzol were shipped on dry ice to KangChen Bio-Tech (Shanghai, China) for analysis via Agilent Whole-Human Genome Oligo Microarray Platform. RNA preparation and microarray hybridization were performed according to Exiqon’s manual. For TaqMan PCR, the total RNA was isolated using the mirVana miRNA Isolation Kit (Life Technologies Corporation, USA). RT-PCR was performed using the TaqMan MicroRNA Assay (Life Technologies Corporation, USA) and Mx3005P QPCR System (Agilent Technologies, Inc., CA, USA). U6 gene quantification was used as the control.

Animals and Tumor Growth Model

Bilaterally ovariectomized female athymic nude mice (BALB/c/Nu/Nu) were purchased from the Department of Laboratory Animal Science (BJMU, Beijing, China) at 4 weeks of age. The mice were housed in a dedicated nude mouse facility with micro-isolator caging and handled in a unidirectional laminar airflow hood. The xenografts were established via the subcutaneous inoculation of MCF-7 cells at 200 μL (5 × 106 cells/200 μL) per site into the right back of nude mice. 5 days after inoculation, when tumor volume reached approximately 100 mm3, the mice were randomly divided into five groups (n = 6): blank (PBS), control (AS1411), AS1411-12D, 6L/12D (FCL-I), and 6L/12D/24dI (FCL-II). Treatment of the mice with established tumors was through the intraperitoneal injection of aptamers at doses equivalent to approximately 2.5 optical density 260 nm (ODs)/mice/day daily for the first 4 days, as well as additional treatments at day 6 and day 8 for a total of 6 injections. The volume was calculated using the formula (1/2 × L × W2), where length (L) and width (W) were measured with a caliper during the administration of the aptamers. The weights of the nude mice were regularly examined to assess for toxicity.64

Initial Models

To computationally investigate the effects of the modifications on the conformation and dynamics of the complexes, we selected three representative structures (AS1411-12D, FCL-I, and FCL-II) that exhibited the best biological activities with single, double, and three-site modifications, respectively. Since detailed structural information solved by X-ray or NMR is not available in the case of the modified aptamer, as a template, our previous AS1411-RBD12 computational model was modified to produce the starting models for MD simulations.18

According to our previous studies,17, 19 the force-field parameters for D-/L-IsoT and 2′-dI were obtained by quantum chemical methods using the Gaussian 09 program (Gaussian 09, Gaussian, Inc.). At the B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory, we optimized the entire geometry and calculated the HF/6-31G* electrostatic potential. Then RESP strategy was used to obtain the partial atomic charges. Finally, the non-standard residues in the three models were created using the Xleap module (AMBER v.11).

Molecular Dynamics Simulation

The models were explicitly solved in a rectangular box that extended 10 Å away from any solute atom; potassium ions were added to provide electroneutrality. The MD simulations were performed using the AMBER 11 software package utilizing the all-atom force field AMBER 99SB (AMBER v.11). Initially, an energy minimization of 1,000 steps using the steepest descent algorithm was used, followed by a 200-ps position-constrained MD simulation to equilibrate water and ions. After the minimization, the systems were gradually heated in the canonical ensemble from 0 to 300 K in 100 ps using a Langevin thermostat with a coupling coefficient of 1.0 ps and a force constant of 1.0 kcal/mol 3Å on the complex. The system was again equilibrated for 1 ns by removing all restraints. Finally, a MD production run of 10 ns in the Isobaric-Isothermal ensemble was performed. During the simulation, the cut-off distance for the long-range van der Waals (vdW) energy term was set at 10.0 Å. The long-range Coulombic interactions were handled using the particle mesh Ewald (PME) method, and the SHAKE algorithm was applied to all atoms covalently bound to hydrogen atoms. The simulation was carried out with periodic boundary conditions at constant temperature (300 K) and pressure (1 atm), and an integration time step of 2 fs was used.

Statistical Analysis

The data are presented as the mean ± SD. The significance of the difference between groups was evaluated by a one-way ANOVA. All p values are two-sided, and those less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Y.; Design and Rxperimentation, X.F., L.S., K.L., and B.C.; Writing-Original Draft, X.F. and L.S.; Writing-Review & Editing, X.Y., Y. Zhang, Y. Zhu, and Y.M.; Funding Acquisition, Z.G., Y.W., L.Z., and Z.Y.

Conflicts of Interest

We declare no competing financial interests.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2012CB720604) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21572013, 21332010, and 21502104). We thank Li Liu and Guichun Lin for their help in reagent ordering and instrument maintenance. Weiqing Zhang, Jun Li, Bo Xu, Lijun Wang, Xulin Sun, and Changfeng Hu are also thanked for their help with MS, NMR, SPR, and biological experiments.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes thirty-four figures and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtn.2017.09.010.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Todd A.K., Johnston M., Neidle S. Highly prevalent putative quadruplex sequence motifs in human DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:2901–2907. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duquette M.L., Handa P., Vincent J.A., Taylor A.F., Maizels N. Intracellular transcription of G-rich DNAs induces formation of G-loops, novel structures containing G4 DNA. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1618–1629. doi: 10.1101/gad.1200804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Firnberg E., Ostermeier M. The genetic code constrains yet facilitates Darwinian evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:7420–7428. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarkies P., Reams C., Simpson L.J., Sale J.E. Epigenetic instability due to defective replication of structured DNA. Mol. Cell. 2010;40:703–713. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellington A.D., Szostak J.W. In vitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands. Nature. 1990;346:818–822. doi: 10.1038/346818a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prodeus A., Abdul-Wahid A., Fischer N.W., Huang E.H., Cydzik M., Gariepy J. Targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 immune evasion axis with DNA aptamers as a novel therapeutic strategy for the treatment of disseminated cancers. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2015;4:e237. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2015.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lai W.Y., Huang B.T., Wang J.W., Lin P.Y., Yang P.C. A novel PD-L1-targeting antagonistic DNA aptamer with antitumor effects. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2016;5:e397. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2016.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu H., Canoura J., Guntupalli B., Lou X., Xiao Y. A cooperative-binding split aptamer assay for rapid, specific and ultra-sensitive fluorescence detection of cocaine in saliva. Chem. Sci. (Camb.) 2017;8:131–141. doi: 10.1039/c6sc01833e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin X., Ivanov A.P., Edel J.B. Selective single molecule nanopore sensing of proteins using DNA aptamer-functionalised gold nanoparticles. Chem. Sci. (Camb.) 2017;8:3905–3912. doi: 10.1039/c7sc00415j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mosafer J., Abnous K., Tafaghodi M., Mokhtarzadeh A., Ramezani M. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of anti-nucleolin-targeted magnetic PLGA nanoparticles loaded with doxorubicin as a theranostic agent for enhanced targeted cancer imaging and therapy. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2017;113:60–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2016.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tuerk C., Gold L. Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: RNA ligands to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase. Science. 1990;249:505–510. doi: 10.1126/science.2200121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blind M., Blank M. Aptamer selection technology and recent advances. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2015;4:e223. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2014.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Virgilio A., Petraccone L., Vellecco V., Bucci M., Varra M., Irace C., Santamaria R., Pepe A., Mayol L., Esposito V., Galeone A. Site-specific replacement of the thymine methyl group by fluorine in thrombin binding aptamer significantly improves structural stability and anticoagulant activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:10602–10611. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scuotto M., Persico M., Bucci M., Vellecco V., Borbone N., Morelli E., Oliviero G., Novellino E., Piccialli G., Cirino G. Outstanding effects on antithrombin activity of modified TBA diastereomers containing an optically pure acyclic nucleotide analogue. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014;12:5235–5242. doi: 10.1039/c4ob00149d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scuotto M., Rivieccio E., Varone A., Corda D., Bucci M., Vellecco V., Cirino G., Virgilio A., Esposito V., Galeone A. Site specific replacements of a single loop nucleoside with a dibenzyl linker may switch the activity of TBA from anticoagulant to antiproliferative. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:7702–7716. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang X., Zhu Y., Wang C., Guan Z., Zhang L., Yang Z. Alkylation of phosphorothioated thrombin binding aptamers improves the selectivity of inhibition of tumor cell proliferation upon anticoagulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2017;1861:1864–1869. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2017.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu H.W., Zhang L.R., Zhou J.C., Ma L.T., Zhang L.H. Studies on the synthesis and biological activities of 4′-(R)-hydroxy-5′-(S)-hydroxymethyl-tetrahydrofuranyl purines and pyrimidines. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1996;4:609–614. doi: 10.1016/0968-0896(96)00048-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang J., Chen Y., Huang Y., Jin H.W., Qiao R.P., Xing L., Zhang L.R., Yang Z.J., Zhang L.H. Synthesis and properties of novel L-isonucleoside modified oligonucleotides and siRNAs. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012;10:7566–7577. doi: 10.1039/c2ob26219c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang X., Xiao Z., Zhu J., Li Z., He J., Zhang L., Yang Z. Spatial conservation studies of nucleobases in 10-23 DNAzyme by 2′-positioned isonucleotides and enantiomers for increased activity. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016;14:4032–4038. doi: 10.1039/c6ob00390g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang Y., Chen Z., Chen Y., Zhang H., Zhang Y., Zhao Y., Yang Z., Zhang L. Effects of conformational alteration induced by D-/L-isonucleoside incorporation in siRNA on their stability in serum and silencing activity. Bioconjug. Chem. 2013;24:951–959. doi: 10.1021/bc300642u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai B., Yang X., Sun L., Fan X., Li L., Jin H., Wu Y., Guan Z., Zhang L., Zhang L., Yang Z. Stability and bioactivity of thrombin binding aptamers modified with D-/L-isothymidine in the loop regions. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014;12:8866–8876. doi: 10.1039/c4ob01525h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gu M.J., Li K.F., Zhang L.X., Wang H., Liu L.S., Zheng Z.Z. In vitro study of novel gadolinium-loaded liposomes guided by GBI-10 aptamer for promising tumor targeting and tumor diagnosis by magnetic resonance imaging. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015;10:5187–5204. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S84351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang L.X., Li K.F., Wang H., Gu M.J., Liu L.S., Zheng Z.Z. Preparation and in vitro evaluation of a MRI contrast agent based on aptamer-targeted liposomes. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2016;18:1564–1571. doi: 10.1208/s12249-016-0600-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li K.F., Deng J.L., Jin H.W., Yang X.T., Fan X.M., Li L.Y. Chemical modification improves the stability of the DNA aptamer GBI-10 and its affinity towards tenascin-C. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017;15:1174–1182. doi: 10.1039/c6ob02577c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fan X., Sun L., Wu Y., Zhang L., Yang Z. Bioactivity of 2′-deoxyinosine-incorporated aptamer AS1411. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:25799. doi: 10.1038/srep25799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi E.W., Nayak L.V., Bates P.J. Cancer-selective antiproliferative activity is a general property of some G-rich oligodeoxynucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:1623–1635. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Subramanian N., Srimany A., Kanwar J.R., Kanwar R.K., Akilandeswari B., Rishi P., Khetan V., Vasudevan M., Pradeep T., Krishnakumar S. Nucleolin-aptamer therapy in retinoblastoma: molecular changes and mass spectrometry-based imaging. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2016;5:e358. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2016.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Derenzini M., Sirri V., Trerè D., Ochs R.L. The quantity of nucleolar proteins nucleolin and protein B23 is related to cell doubling time in human cancer cells. Lab. Invest. 1995;73:497–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Girvan A.C., Teng Y., Casson L.K., Thomas S.D., Jüliger S., Ball M.W., Klein J.B., Pierce W.M., Jr., Barve S.S., Bates P.J. AGRO100 inhibits activation of nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-kappaB) by forming a complex with NF-kappaB essential modulator (NEMO) and nucleolin. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2006;5:1790–1799. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu X., Hamhouyia F., Thomas S.D., Burke T.J., Girvan A.C., McGregor W.G., Trent J.O., Miller D.M., Bates P.J. Inhibition of DNA replication and induction of S phase cell cycle arrest by G-rich oligonucleotides. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:43221–43230. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104446200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenberg J.E., Bambury R.M., Van Allen E.M., Drabkin H.A., Lara P.N., Jr., Harzstark A.L., Wagle N., Figlin R.A., Smith G.W., Garraway L.A. A phase II trial of AS1411 (a novel nucleolin-targeted DNA aptamer) in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Invest. New Drugs. 2014;32:178–187. doi: 10.1007/s10637-013-0045-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee K.Y., Kang H., Ryu S.H., Lee D.S., Lee J.H., Kim S. Bioimaging of nucleolin aptamer-containing 5-(N-benzylcarboxyamide)-2′-deoxyuridine more capable of specific binding to targets in cancer cells. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010;2010:168306. doi: 10.1155/2010/168306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chung W.J., Heddi B., Schmitt E., Lim K.W., Mechulam Y., Phan A.T. Structure of a left-handed DNA G-quadruplex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:2729–2733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418718112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Do N.Q., Chung W.J., Truong T.H.A., Heddi B., Phan A.T. G-quadruplex structure of an anti-proliferative DNA sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:7487–7493. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bagheri Z., Ranjbar B., Latifi H., Zibaii M.I., Moghadam T.T., Azizi A. Spectral properties and thermal stability of AS1411 G-quadruplex. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015;72:806–811. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Giraldo R., Suzuki M., Chapman L., Rhodes D. Promotion of parallel DNA quadruplexes by a yeast telomere binding protein: a circular dichroism study. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:7658–7662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tuteja R., Tuteja N. Nucleolin: a multifunctional major nucleolar phosphoprotein. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1998;33:407–436. doi: 10.1080/10409239891204260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bates P.J., Laber D.A., Miller D.M., Thomas S.D., Trent J.O. Discovery and development of the G-rich oligonucleotide AS1411 as a novel treatment for cancer. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2009;86:151–164. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang Z., Chen X., Yu B., He J., Chen D. MicroRNA-27a promotes myoblast proliferation by targeting myostatin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012;423:265–269. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.05.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baran N., Pucshansky L., Marco Y., Benjamin S., Manor H. The SV40 large T-antigen helicase can unwind four stranded DNA structures linked by G-quartets. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:297–303. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.2.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pichiorri F., Palmieri D., De Luca L., Consiglio J., You J., Rocci A., Talabere T., Piovan C., Lagana A., Cascione L. In vivo NCL targeting affects breast cancer aggressiveness through miRNA regulation. J. Exp. Med. 2013;210:951–968. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanic M., Yanowsky K., Rodriguez-Antona C., Andrés R., Márquez-Rodas I., Osorio A., Benitez J., Martinez-Delgado B. Deregulated miRNAs in hereditary breast cancer revealed a role for miR-30c in regulating KRAS oncogene. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e38847. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tan X., Peng J., Fu Y., An S., Rezaei K., Tabbara S., Teal C.B., Man Y.G., Brem R.F., Fu S.W. miR-638 mediated regulation of BRCA1 affects DNA repair and sensitivity to UV and cisplatin in triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16:435. doi: 10.1186/s13058-014-0435-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sakurai M., Miki Y., Masuda M., Hata S., Shibahara Y., Hirakawa H., Suzuki T., Sasano H. LIN28: a regulator of tumor-suppressing activity of let-7 microRNA in human breast cancer. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2012;131:101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bronisz A., Godlewski J., Wallace J.A., Merchant A.S., Nowicki M.O., Mathsyaraja H., Srinivasan R., Trimboli A.J., Martin C.K., Li F. Reprogramming of the tumour microenvironment by stromal PTEN-regulated miR-320. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011;14:159–167. doi: 10.1038/ncb2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen Y., Zhang J., Wang H., Zhao J., Xu C., Du Y., Luo X., Zheng F., Liu R., Zhang H., Ma D. miRNA-135a promotes breast cancer cell migration and invasion by targeting HOXA10. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:111. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eissa S., Matboli M., Shehata H.H. Breast tissue-based microRNA panel highlights microRNA-23a and selected target genes as putative biomarkers for breast cancer. Transl. Res. 2015;165:417–427. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zearo S., Kim E., Zhu Y., Zhao J.T., Sidhu S.B., Robinson B.G., Soon P.Sh. MicroRNA-484 is more highly expressed in serum of early breast cancer patients compared to healthy volunteers. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:200. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ng E.W., Shima D.T., Calias P., Cunningham E.T., Jr., Guyer D.R., Adamis A.P. Pegaptanib, a targeted anti-VEGF aptamer for ocular vascular disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006;5:123–132. doi: 10.1038/nrd1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Basile A.S., Hutmacher M.M., Kowalski K.G., Gandelman K.Y., Nickens D.J. Population pharmacokinetics of pegaptanib sodium (Macugen(®)) in patients with diabetic macular edema. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2015;9:323–335. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S74050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kiire C.A., Morjaria R., Rudenko A., Fantato A., Smith L., Smith A., Chong V. Intravitreal pegaptanib for the treatment of ischemic diabetic macular edema. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2015;9:2305–2311. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S90322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rinaldi M., Chiosi F., Dell'Omo R., Romano M.R., Parmeggiani F., Semeraro F., Menzione M., Costagliola C. Intravitreal pegaptanib sodium (Macugen) for treatment of myopic choroidal neovascularization: a morphologic and functional study. Retina. 2013;33:397–402. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318261a73c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yazdi M.H., Faramarzi M.A., Nikfar S., Falavarjani K.G., Abdollahi M. Ranibizumab and aflibercept for the treatment of wet age-related macular degeneration. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2015;15:1349–1358. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2015.1057565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kanwar J.R., Shankaranarayanan J.S., Gurudevan S., Kanwar R.K. Aptamer-based therapeutics of the past, present and future: from the perspective of eye-related diseases. Drug Discov. Today. 2014;19:1309–1321. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pastor F., Soldevilla M.M., Villanueva H., Kolonias D., Inoges S., de Cerio A.L., Kandzia R., Klimyuk V., Gleba Y., Gilboa E., Bendandi M. CD28 aptamers as powerful immune response modulators. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2013;2:e98. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2013.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Montange R.K., Batey R.T. Riboswitches: emerging themes in RNA structure and function. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2008;37:117–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.130000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xu D., Shi H. Composite RNA aptamers as functional mimics of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:e71. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reyes-Reyes E.M., Teng Y., Bates P.J. A new paradigm for aptamer therapeutic AS1411 action: uptake by macropinocytosis and its stimulation by a nucleolin-dependent mechanism. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8617–8629. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kotula J.W., Pratico E.D., Ming X., Nakagawa O., Juliano R.L., Sullenger B.A. Aptamer-mediated delivery of splice-switching oligonucleotides to the nuclei of cancer cells. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2012;22:187–195. doi: 10.1089/nat.2012.0347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dam D.H., Culver K.S., Odom T.W. Grafting aptamers onto gold nanostars increases in vitro efficacy in a wide range of cancer cell types. Mol. Pharm. 2014;11:580–587. doi: 10.1021/mp4005657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Teng Y., Girvan A.C., Casson L.K., Pierce W.M., Jr., Qian M., Thomas S.D., Bates P.J. AS1411 alters the localization of a complex containing protein arginine methyltransferase 5 and nucleolin. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10491–10500. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ginisty H., Amalric F., Bouvet P. Nucleolin functions in the first step of ribosomal RNA processing. EMBO J. 1998;17:1476–1486. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen J., Zhang L.R., Min J.M., Zhang L.H. Studies on the synthesis of a G-rich octaoligoisonucleotide (isoT)2(isoG)4(isoT)2 by the phosphotriester approach and its formation of G-quartet structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:3005–3014. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hoeflich K.P., Herter S., Tien J., Wong L., Berry L., Chan J., O’Brien C., Modrusan Z., Seshagiri S., Lackner M. Antitumor efficacy of the novel RAF inhibitor GDC-0879 is predicted by BRAFV600E mutational status and sustained extracellular signal-regulated kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway suppression. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3042–3051. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.