Abstract

Objective

Our aim is to review, and qualitatively evaluate, the aims and measures of social referral programmes. Our first objective is to identify the aims of social referral initiatives. Our second objective is to identify the measures used to evaluate whether the aims of social referral were met.

Design

Literature review.

Background

Social referral programmes, also called social prescribing and emergency case referral, link primary and secondary healthcare with community services, often under the guise of decreasing health system costs.

Method

Following the PRISMA guidelines, we undertook a literature review to address that aim. We searched in five academic online databases and in one online non-academic search engine, including both academic and grey literature, for articles referring to ‘social prescribing’ or ‘community referral’.

Results

We identified 41 relevant articles and reports. After extracting the aims, measures and type of study, we found that most social referral programmes aimed to address a wide variety of system and individual health problems. This included cost savings, resource reallocation and improved mental, physical and social well-being. Across the 41 studies and reports, there were 154 different kinds of measures or methods of evaluation identified. Of these, the most commonly used individual measure was the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale, used in nine studies and reports.

Conclusions

These inconsistencies in aims and measures used pose serious problems when social prescribing and other referral programmes are often advertised as a solution to health services-budgeting constraints, as well as a range of chronic mental and physical health conditions. We recommend researchers and local community organisers alike to critically evaluate for whom, where and why their social referral programmes ‘work’.

Keywords: Social Prescribing, Social Referral, Literature Review, Social Medicine, Health Services Research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A strength of this study was the inclusion of both grey and academic literature to ensure a broad representation of social referral programmes.

A strength of this study is in the review of aims and measures of social referral programmes, rather than outcomes.

A limitation of this study was that there is no guarantee of an entirely comprehensive inclusion of all relevant articles; for example, we only accessed articles and reports available online or through the British Library.

A limitation of this study was the use of the search term ‘social prescribing’ as this is a generalised UK region-specific term; however, this is the term used colloquially to describe social referral programmes.

Introduction

“The tonic effect of fun and play has long been recognized as an antidote to the stresses, worries, labors, and responsibilities of our workaday life…we must diagnose and prepare the prescription.”1 In 1958, Walt Disney wrote this commentary on film and American life for the 75th anniversary of the Journal of the American Medical Association. Although few would argue that Disney was a great early adopter of the social determinants of health model, this demonstrates a timely understanding of the impact of social activities on well-being. Academic research demonstrates that social well-being is closely tied to physical health, a well-known example being the impact of socioeconomic positioning on mortality as demonstrated in the Whitehall Studies, as well as other more recent work by Michael Marmot.2 3 Though this common understanding has not fully translated into clinical practice and public health. Particularly in the context of publicly funded medical systems like the UK’s National Health Service (NHS), resource limitations and unclear evidence on the causal mechanisms between social activities and improved health make it challenging to incorporate social well-being in treatment models.4

Over the past decade, one proposed method of addressing this linking up of health and care services is referral out of primary care health systems and in to the community.5 6 This ‘emerging model of care’ was alluded to in the NHS 5 Year Forward View7 in the context of healthcare needing to move to a partnership rather than discrete episodes of treatment. More substantially, social prescribing was recommended as a key resource for primary care, noting that ‘non-medical interventions such as social prescribing can contribute to primary care teams meeting the physical, psychological and social care needs of an individual in the round’8 (p7). Sometimes with alternative descriptors such as ‘community referral’, ‘community links’, and ‘arts on prescription’, these programmes link healthcare to opportunities and events provided by third-sector organisations. A rapid evidence review by the University of York defined ‘(social) prescribing (as) a way of linking up patients in primary care with sources of support in the community’; however, the authors highlight that there is no agreed definition.9 Kimberlee10 suggests that social prescribing consists of a range of different services, from more traditional smoking cessation programmes, and describes social prescribing as ‘a route to reducing social exclusion, both for disadvantaged, isolated and vulnerable populations in general, and for people with enduring mental health problems’. (p105).

Although social prescribing is a commonly used term, we use ‘social referral’ to be as inclusive as possible in describing links between healthcare and third-sector organisations. In cases where a study specifically uses terms like arts on prescription or ‘social prescribing’, we refer to it as such. We also do not specify primary care as the only source of social referral; we include referrals by other healthcare workers.

Evidence for the effectiveness of social referral services has been characterised as inconclusive.9 Although there is significant, if piecemeal, investment in social referral programmes, many advocates of their value7 10 who attempt to summarise the current evidence, and thus address these criticisms, have similarly been inconclusive in evidencing the health, social, or service-related benefits of social referral.11–15 Mossabir et al13 conducted a scoping review of seven studies on social prescribing and found that although potentially beneficial for psychosocial health, there had been too few empirical studies to draw clear conclusions. The University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination9 goes as far as to argue ‘there is little in the way of supporting evidence of effect to inform the commissioning of a social prescribing programme’ (p4).

The first step in evaluating any programme is determining what it aims ‘to do’ and deciding on the measures that will be used to ascertain effectiveness. There has thus far been little reflection on the intended aims of social referral and the measures used to judge whether the aims have been met. Accordingly, our purpose is to summarise the aims and measures of social referral through a review of the literature. Our first objective is to identify the aims of social referral initiatives. Our second objective is to identify the measures used to evaluate whether the aims of social referral were met. This creates a foundation to inform further programme development and evaluation and for theorising the various mechanisms that may, in specified contexts, be responsible for changes in particular outcomes. We can thus better understand what is meant by ‘social prescription’ with a view to informing evaluations to consider the contexts in which social referral works, for whom and through which mechanisms.16

Literature search methodology

As part of the ‘Collaborating to Deliver Social Prescribing in Bath and North East Somerset’ project, we conducted a review of empirical and grey literature related to ‘social prescribing’. We identified PubMed suggested terms associated with social prescribing, as this is the most commonly used term to identify these kinds of community-linking programmes. The final terms were ’social prescribing', ‘social prescribing services’, ’social prescription', ‘social prescriptions’, ’community referrals', ‘community referred’, ‘community-referred patients’, ‘community refers’ or ‘community-referring physicians’. We used exactly these terms to search each of the following databases: Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, National Institute for Health and Care Institute (NICE) Evidence Guidelines database and PsycNET for academic peer-reviewed articles. See online supplementary file 1 for a full example search strategy. The term social referral was not included as we defined this term post hoc, to subsume programmes that did not label themselves as social prescribing as well as those that did. Finally, we examined the first five pages of results identified by internet search engine Google to identify grey literature reports related to social prescribing. After the online database search, academic and non-academic literature reference lists were handsearched. Only the academic literature’s citations were searched as several of the non-academic reports were not held on an academic database; therefore, citation searches could not be conducted. The initial search, including citations and reference searching, took place in February 2016 and an updated search was conducted in November 2016 to include recent articles and reports. There were no date restrictions applied in either of these searches.

bmjopen-2017-017734supp001.pdf (172.4KB, pdf)

Identified articles were deemed relevant for inclusion if they reported the assessment of a referral programme of patients from a health context to a social context. A health context was considered any form of health or mental care, for example, emergency departments, primary care, and mental health professionals. A social context was considered any form of community programme including cultural programmes, arts classes, or community groups. This excluded programmes evaluating a single programme, for example, a diabetes health management course. We excluded these ‘single intervention’ studies as by definition social referral programmes are premised on referring an individual to a range of interventions. After searching using these broad criteria, additional inclusion criteria were added due to the unexpected range of study methodologies, including many interview studies focused on clinical or provider perspectives. These criteria included the use of empirical methodology (qualitative, mixed methods or quantitative), assessment of a patient sample, and the production of a final article or report. This therefore excluded empirical articles that were evaluating the service provider’s views of a social referral programme. Reports or articles that were not in their final version (eg, commissioner or funding interim reports) were excluded as were conference reports and book chapters. No language or region restrictions were applied. After identification of relevant articles and reports, we extracted the study type, stated aim(s) and measures of each social referral programme. We categorised each study’s aim(s) as mental, health, social, service use, service cost, and/or other and also extracted number of aims and whether a study aimed to address both individual-level and system-level aims. We did not assess study quality as we were not concerned with the results of social referral only the stated aims and measures. We also extracted the social referral programme name, study design, referral criteria, programme location, programme type, number of programme participants, and number of study participants.

ESR screened all initial articles for title and abstract relevancy, and ENW then read these articles, identified by ESR, for verification that they met inclusion criteria. The first coder, ESR, developed the coding framework and the second coder, ENW, separately coded all articles to this framework. Any differences between the coding of aims or measures, or the inclusion of articles, were subsequently discussed and agreed on. Due to the qualitative nature of the review, we did not calculate percentage agreement.

Results

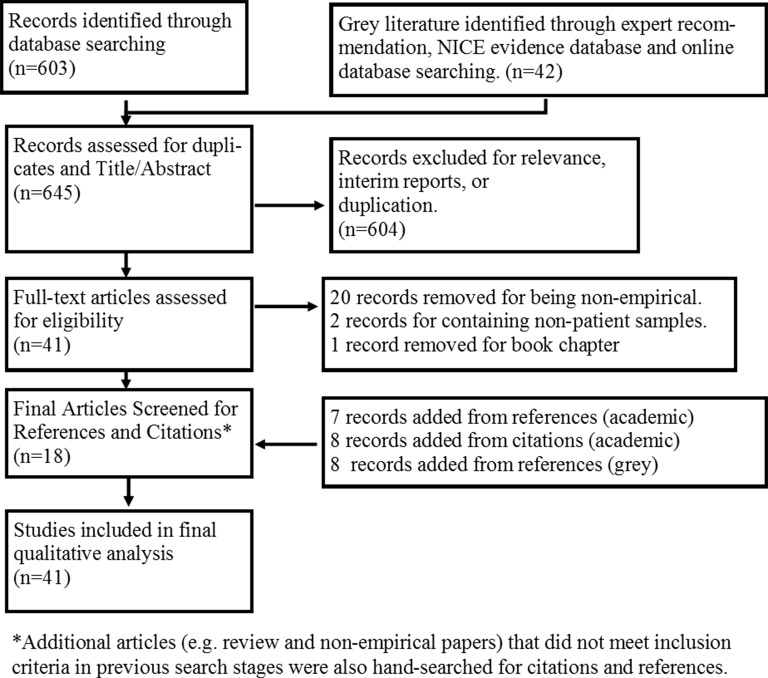

The initial database search resulted in 645 articles or reports. After duplicate removal, title and abstracts were reviewed according to inclusion and exclusion criteria, 41 articles were identified. On assessment of these full-text articles, 20 were removed for being non-empirical (eg, discussion or review articles that did not evaluate a specific social referral programme but rather provided a general discussion on social referral), two were removed for containing non-patient samples and one was removed as it was a book chapter. After a forwards and backwards citation search, a further 23 articles were identified as relevant. At the initial February 2016 search, six review articles or articles with non-patient samples were also handsearched for references and citations. Three non-academic articles referenced in grey literature reports that may have been relevant could not be found as copies of these reports were not held online, were not available through interlibrary loans and were not held at the British Library. Furthermore after contacting the citing author and place of publication, these articles could still not be found. In total, 41 texts were analysed. See figure 1 for a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)diagram of the search strategy and results.

Figure 1.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram for the literature search strategy for social referral programmes. The main criterion for inclusion was an empirical assessment of a programme that contained a patient referral out of the healthcare system and into the community or voluntary system. Six hundred and forty-five articles and reports were initially identified and assessed for duplication and relevance. Forty-one articles and reports were then assessed for full-text eligibility. Eighteen articles or reports were identified. The citations and reference lists for the academic articles were searched for additional literature, alongside other non-eligible review papers, as well as the reference lists of the non-academic reports. This resulted in 23 articles further identified as relevant. Finally, 41 studies were included in the qualitative synthesis. NICE refers to the National Institue for Health and Care Excellence.

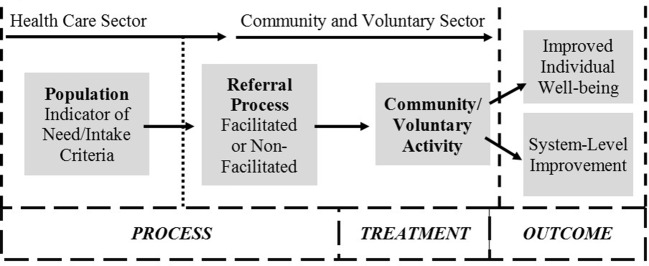

Of the 41 empirical studies, seven were qualitative, 16 were quantitative and 18 employed mixed methodologies. Figure 2 outlines the process of social referral programmes described in these studies. The broad nature of the search led to a broad range of programmes but all followed the basic outline seen in figure 2. There was considerable variation in indicators of need, referral process, and types of activities undertaken. For example, emergency case management as described by Lee and Davenport17 specifies the population as those who have three or more emergency department visits per month, as well as a list of specific health concerns. Their referral process is nurse-led case management, where they refer to community services as well as other health services. The activities varied including both community as well as more traditional health referrals. In contrast, Stickley and Hui18 describe a prescriptive arts programme. They do not specify a population, only the referral mechanism. The referral was from a primary or secondary mental health worker. The activity was a 10-week arts programme and the anticipated outcome was personal health improvement. Online supplementary appendix 1 outlines the various types of programmes and study designs. Of the 41 studies, there were 38 unique social referral projects. There were two repeated programmes (Arts on Prescription and the BRIGHT trial); however, the four studies were all individual evaluations of these services. As well, the Health Trainer and Social Prescribing Service19 was based on a previous pilot of the CHAT programme.12 The majority of these texts described either a social prescription programme or an emergency department case management programme. All of the social prescribing programmes were set in the UK. The emergency department case management programmes were located in the USA, UK, Canada, and Taiwan. All studies included only adult populations with study size ranging from 4 to 784. Patient samples varied greatly, from kidney patients to elderly adults. Programme size also greatly varied from 12 to 1848 referrals. See online supplementary appendix 1 and 2 for more details.

Figure 2.

A summary of the social referral process identified in the literature search. All programmes’ participants were identified by various indicators of need, for example, low-level mental health conditions within the healthcare sector. The participants were then provided with either a facilitated or non-facilitated referral to a community or voluntary activity. Patient identification and referral represent the ‘process’ while the activity represents the ‘treatment’ of social referral programmes. Finally, the proposed outcomes included either improved individual well-being, for example, mental well-being, and/or system-level improvement, for example, reallocated healthcare resources.

bmjopen-2017-017734supp002.pdf (154.3KB, pdf)

Table 1 outlines the aims of the programmes described in the empirical studies. The stated aims were those listed in the individual studies, while the core aims were derived by grouping together similar aims across programmes. The core aims were then grouped in relation to the level at which the intervention was aimed: individual or system. The core individual aims identified included improved mental well-being, improved physical well-being, and improved social well-being. The core system-level aims included optimised health service use and decreased health service cost. Only nine studies stated a single aim. The majority of studies thus stated multiple aims: 16 stated two, 10 stated three, four stated four and one study stated five aims. Nineteen studies focused on both individual-level and system-level outcomes (see online supplementary appendix 2 for full details). Improved mental well-being was the most common core aim, with 25 of 41 studies. Physical well-being, social well-being, and optimised service use were also frequently cited with 16, 21 and 23 studies, respectively. Six studies addressed the least common core aim of cost savings.

Table 1.

Summary of aims of social referral programmes (n=41)

| Aim level | Core aim | Stated aim | Number of references |

| Individual-level aim | Improved mental well-being | To enhance skills/behaviours that improve mental well-being.29 | |

| To help individuals retain/recover functional capacity to study or work.30 | |||

| To improve/address psychosocial health.31–35 | 25 | ||

| To improve mental health and well-being.5 18 20 23 29 36–46 | |||

| To improve patient quality of life.46 47 | |||

| To improve resilience, confidence, and self-esteem.44 48 | |||

| To improve spiritual well-being.5 | |||

| To support emotional needs.49 | |||

| Improved physical well-being | To empower and support individuals to choose a healthier lifestyle.46 | ||

| To improve physical health and well-being.5 17 20 23 31 37 38 40 42 50–53 | 16 | ||

| To improve self-assessed health status.54 | |||

| To support the self-management of long-term health conditions.38 50 55 | |||

| Improved social well-being | To increase connection to community-based support.29 37 | 21 | |

| To improve/address psychosocial health.31–35 | |||

| To improve resilience, confidence, and self-esteem.48 | |||

| To improve social inclusion/engagement.20 23 30 32 38 41 | |||

| To improve social well-being40 42 52 | |||

| To support social needs/outcomes.19 36 49 53 56 | |||

| Other | To address practical needs, for example, employment.49 | 2 | |

| To improve connection to nature.23 | |||

| System-level aim | Optimised health service use | To broaden health service provision in the community.12 | 23 |

| To improve service use.32 | |||

| To increase take-up of community activities.29 38 44 | |||

| To optimise healthcare coordination.57 | |||

| To provide appropriate arts course recommendations.44 | |||

| To provide better management of psychosocial problems in primary care.47 | |||

| To reduce emergency department use/acute hospital care.17 35 37 51 58 59 | |||

| To reduce health service use.21 39 42 53 54 57 | |||

| To reduce hospital care use.22 38 59 | |||

| To reduce primary care service use.18 34 37 38 | |||

| To support the self-management of long-term physical or mental health conditions.44 50 55 | |||

| Decreased health service cost | To reduce cost associated with long-term health conditions.50 | 6 | |

| To reduce health services costs.5 21 35 42 53 | |||

| Other | To reduce environmental cost (carbon footprint).21 | 1 |

Aims of social referral programmes, not study aims.

bmjopen-2017-017734supp003.pdf (199.2KB, pdf)

The mental well-being core aim was generally characterised by mental health or general well-being. Improved psychosocial state was considered to be both related to social and mental well-being. Physical well-being included both general health and the improvement of long-term health conditions, like kidney disease. Social well-being included improvements in social and community engagement and quality of life. Health service use and cost aims included reductions in emergency department use, general practitioner (GP) use, hospital stay length and other forms of primary care costs. The service use aim also included instances where researchers were aiming to increase the uptake of community services. See online supplementary appendix 2 for more detail on aims.

Table 2 outlines the measures and methods used to evaluate the social referral projects by frequency. Across all aims, these included administrative data/analysis, physical health questionnaires, mental health diagnostic measures, qualitative assessments and social/behavioural questionnaires. Across the 41 studies and reports, 154 different kinds of measures or methods of evaluation were identified (see online supplementary appendix 2). Twenty-one measures or methods were used more than once; however, many of these were forms of administrative data counts. The most commonly used scale was the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale, used in nine studies.

Table 2.

Measures and methods used in studies/reports of social referral by frequency (n=41)

| Measure/method | No of studies/reports using measure/method | Examples of programme aims addressed* |

| Semistructured interviews to explore patient experience | 14 | NA† |

| Warwick Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (14 or 7 item) | 9 | Improved mental well-being Improved physical well-being Improved social well-being |

| Number of GP appointments (administrative) | 6 | Optimised health service use Reduced health service cost Improved physical well-being |

| Short case description of participant experience | 6 | Improved physical well-being Improved social well-being Optimised health service use |

| Emergency department admissions/Hospital Episode Statistics (administrative) | 6 | Optimised health service use |

| Demographic questions | 5 | Improved mental well-being |

| Cost analysis | 5 | Reduced health service cost Optimised health service use |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale | 5 | Improved mental well-being Improved physical well-being |

| Focus group with patients to explore patient outcomes | 4 | NA‡ |

| General Health Questionnaire-12 | 3 | Improved mental well-being Improved physical well-being |

| No. of secondary referrals (administrative) | 3 | Optimised health service use Reduced health service cost |

| Geriatric Depression Scale | 2 | Improved mental well-being |

| Focus group with family members who engaged with the service to explore service experience | 2 | NA‡ |

| Hospital admissions length (administrative) | 2 | Optimised health service use |

| Reason for referral | 2 | Improved mental well-being Optimised health service use |

| Referral records (eg, what activities were referred to) | 2 | Improved social well-being |

| Social Return on Investment Analysis | 2 | Reduced health service cost Improved mental well-being |

| Work and Social Adjustment Scale | 2 | Improved social well-being |

| No. of Hospital Admissions (administrative) | 2 | Optimised health service use |

| No. of prescriptions for psychosocial reasons (administrative) | 2 | Optimised health service use Improved mental well-being |

Where the measure or method was used in n>1 report or study.

*These are only example aims because it was not always clear how each aim and measure matched up.

†Not applicable as the qualitative semistructured interviews and focus groups were exploratory and did not have a specific programme aim to measure.

Discussion

Examination of the aims of studies seeking to evaluate social referral initiatives and the measures used to evaluate their outcome has revealed extensive heterogeneity. This is unsurprising considering the variability in populations and types of programmes and is not problematic per se. We will discuss the various aims of social referral and the implications of the variety of measures used before considering what this variability means for the future of social referral programmes. In doing so, it is important to reiterate the hugely varied nature of the events and opportunities to which people are being referred, as well as the substantial variety of recipients of this referral. While we expect variation in programme aims and measures, these varied programmes were included because they all aimed to link individuals with community and healthcare services. It is therefore reasonable to assume that there would be some kind of consistency in the measures used to address particular aims.

Aims of social referral

The vast majority of studies, 32 out of the total 41, included multiple aims. Nineteen of these were concerned with both individual-level and system-level outcomes (see table 1 and online supplementary appendix 2), for example, mental well-being and health service costs. While a single study containing aims at individual and system levels is not problematic as such, what is problematic is the lack of articulation of the presumed causal pathways from the treatment programme to improved individual health and to better healthcare resource allocation. As a thought experiment, an individual who is a frequent health service user and has poor control over their diabetic care could, in theory, be empowered by a social referral service and continue high levels of primary care access as they take greater ownership of their health. Indeed a few studies have found an uptake in medical service use post-social referral.20–22 It is also important to note that when reviewing the grey literature, and indeed some of the academic literature as well, the aims of the programme were not always clearly stated. It is reasonable for programmes to try to address multiple aims; however, it is not acceptable for these programmes not to theorise, test, and critically evaluate the relationship between them.

Measures of social referral

Measuring what ‘works’ is inherently linked to defining what these programmes intend to do and requires meaningful, specific, and comparable indices. The diversity of measures evident in social referral initiatives, often associated with a series of vaguely similar aims, suggests that what programmes are aiming to do is often different despite having notionally similar programme structures. Additionally of course it is important to take into account the role of population type and activity type in how aims are translated in to measures. However, as seen in table 2, measures used in social referral initiatives are considerably more plentiful than their aims. For example, Bragg et al23 used 12 different tools in their evaluation of an ecotherapy programme. The multiple measures both within and between studies render comparability between studies, even those addressing the same or similar aims, impossible. Similarly, we could not meaningfully narrow them to provide recommendations on preferred measures. Where there were multiple aims, papers rarely stated which measure was meant to address which aim. While we might infer that administrative counts of GP visits would measure GP use, the assumed relationship between number of GP visits and physical well-being is less clear. Clarity of reporting in the hypothesised relationship between aims and outcome measures is vital in understanding the causal mechanisms that link a programme with its outcomes. From one perspective, measuring the same outcome in several ways could lead to a more robust proof of effect. In theory, this could lead to a stronger evidence base about the effect of social referral on individual-level and system-level outcomes. A less generous explanation behind the proliferation of measures is that researchers and evaluators do not have a definitive understanding of how exactly the aim of their social referral service can translate in to measures. Where the aims are not clearly set out, it may be that they are not being communicated well but the possible explanation that the aims are unknown or unclear cannot be ruled out. It certainly suggests that one of the essential building blocks for an evaluation of a complex health system,24 that is, establishing the current evidence base, has not been undertaken and/or understood. Establishing the evidence base constitutes a crucial springboard for developing hypotheses as to the mechanisms through which social prescribing programmes might improve social well-being and, ultimately, physical and health outcomes. Identification with the group, for example, rather than simply engaging in group activities may be one such mechanism.25

In the final analysis, while there is a notable policy push for the implementation of social referral programmes, definitive and systematic evaluations of social referral programmes are not possible while aims and measures are so inconsistent. As a caveat, one can expect that where populations and activities vary one can expect different measures. However, where social referral programmes aim to do similar things, measures that are similar should follow, for example, the Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale is not population, nor activity specific. We hope that this review provides a first step towards categorising the aims of social referral programmes, that is, to improve physical, mental and social health, as well as reducing costs and improving healthcare resource allocation. Although these aims are broad, they provide a framework for highlighting what these programmes intend to do, and not do, and identifying which measures might best be used to assess different types of aims. This would be a start in applying a more consistent methodology.

The solution to the issue of aim and measurement variability in programmes is not to give up on social referral in general. Certainly, the incorporation of social and mental well-being within traditional biomedical health systems seems an essential step in tackling relatively recent problems in healthcare, for example, services for ageing populations, and may create new opportunities for people who are stagnated in their ability to access services that improve their health. However, at this time, despite policy claims of value and claims of the effectiveness of individual programmes, reviews of these programmes are clear that we do not have evidence that this is the case.9 12–15 26–28 We would argue that while aims and measures remain diffuse and the links between them undertheorised and underspecified that we actually cannot know that this is the case. We call on researchers and evaluators alike to consider the active ingredients of their programmes and in doing so echo a similar call made by the University of York asking, simply, for whom, in what context, how, and why do they intend to prescribe social activities9? And while these can be challenging to answer, if we do not know the answers to these simple questions, how can we possibly prepare a prescription?

Strengths and weaknesses

Although this review has been systematically conducted providing a transparent account of the process, we cannot guarantee this has included all relevant social referral programmes. Social prescribing is a generalised UK region-specific term for medical-based referral to non-medical services. There are likely social referral-like programmes in other countries that are not easily identified. Every effort was made to be as inclusive as possible in phrasing but there will inevitably be some studies missed. Conversely, the strength of our analysis is our inclusion of both grey and academic literature. By including non-academic reports, we analysed valuable literature that would normally not be included in reviews. As well, this review is a first step in creating consistency and justification for the inclusion of social referral programmes in broader nationwide initiatives to address the social ills of health. The contribution of our approach to reviewing social referral is valuable due to its focus on aims and measures rather than, as is the case in other reviews, the outcomes of programmes.

Conclusion

This review aimed to analyse and summarise the aims and measures used in the evaluation of social referral programmes. Social referral is variously described as social prescribing, community referral, and emergency case management among other terms. We found great variation in the aims of these projects including aims to improve mental well-being, physical health, social well-being, and costs savings. We further found that measures used to analyse these aims were highly varied. We would suggest that a next step to addressing the social determinants of health in primary and secondary care is to derive more differentiated and concrete definitions of social referral that more specifically reflect what practitioners and commissioners intend for programmes to achieve and thus to dispense with a general notion of social referral often uncritically considered as the ‘golden child’ of cost savings and improved mental health. However, by setting clear aims and using appropriate measures, social referral can move beyond pilot studies and in to general practice. To that end, we must endeavour to respond to Walt Disney’s call to ‘diagnose and prepare the prescription’.1

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the ‘Collaborating to Deliver Social Prescribing in Bath and North East Somerset’ Project Team, in particular Developing Health & Independence, the Wellbeing College, Second Step, Bath & North East Somerset Council, led by Digital Algorithms Ltd.

Footnotes

Contributors: ESR, JB and HD designed the study protocol. ESR conducted the database searching, while ESR and ENW conducted the data extraction. The report was written by ESR and JB. All authors edited the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by Innovate UK, project code: 102412-399209.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Full coding guidelines and summaries for all articles included can be found in the supplementary appendices 1 and 2.

References

- 1.Disney W. Film entertainment and community life. J Am Med Assoc 1958;167:1342–5. 10.1001/jama.1958.02990280028008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marmot M. UCL Institute of Health Equity. Review of social determinants and the health divide in the WHO European Region: final report. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marmot MG, Stansfeld S, Patel C, et al. Health inequalities among British civil servants: the Whitehall II study. The Lancet 1991;337:1387–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marshall M. A precious jewel--the role of general practice in the English NHS. N Engl J Med 2015;372:893–7. 10.1056/NEJMp1411429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kimberlee R, Ward R, Jones M, et al. Proving our value: Measuring the economic impact of Wellspring Health Living Centre’s social prescribing Wellbeing Programme for low level mental health issues encountered by GP services. Bristol: University of the West of England, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kimberlee R. Developing a Social Prescribing approach for Bristol. University of the West of England, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7.NHS. NHS Five Year Forward View. England: National Health Institute, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dyson B. Improving general practice: A call to action – phase one report. London, UK: NHS England, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.The University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Evidence to inform the commissioning of social prescribing. York: University of York, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kimberlee R. What is social prescribing? ASSRJ 2015;2:102–10. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bungay H, Clift S. Arts on prescription: a review of practice in the U.K. Perspect Public Health 2010;130:277–81. 10.1177/1757913910384050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.South J, Higgins TJ, Woodall J, et al. Can social prescribing provide the missing link? Prim Health Care Res Dev 2008;9:310. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mossabir R, Morris R, Kennedy A, et al. A scoping review to understand the effectiveness of linking schemes from healthcare providers to community resources to improve the health and well-being of people with long-term conditions. Health Soc Care Community 2015;23:467–84. 10.1111/hsc.12176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar GS, Klein R. Effectiveness of case management strategies in reducing emergency department visits in frequent user patient populations: a systematic review. J Emerg Med 2013;44:717–29. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.08.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soril LJ, Leggett LE, Lorenzetti DL, et al. Reducing frequent visits to the emergency department: a systematic review of interventions. PLoS One 2015;10:e0123660 10.1371/journal.pone.0123660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pawson R, Tilley N. Realistic evaluation. London: SAGE; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee KH, Davenport L. Can case management interventions reduce the number of emergency department visits by frequent users? Health Care Manag 2006;25:155–9. 10.1097/00126450-200604000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stickley T, Hui A. Social prescribing through arts on prescription in a U.K. city: participants' perspectives (part 1). Public Health 2012;126:574–9. 10.1016/j.puhe.2012.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White J, Kinsella K, South J. An evaluation of social prescribing health trainers in South and West Bradford. Leeds: Leeds Metropolitan University, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen GD, Perlstein S, Chapline J, et al. The impact of professionally conducted cultural programs on the physical health, mental health, and social functioning of older adults. Gerontologist 2006;46:726–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maughan DL, Patel A, Parveen T, et al. Primary-care-based social prescribing for mental health: an analysis of financial and environmental sustainability. Prim Health Care Res Dev 2016;17:114–21. 10.1017/S1463423615000328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta K, Coupland L. Fottrell E. A two-year review of an ’open access' multidisciplinary community psychiatric service for the elderly. J Geriatr Psychiatry 1996;11:795–9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bragg R, Wood C, Barton J. Ecominds effects on mental wellbeing: an evaluation for mind. Essex: University of Essex, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lamont T, Barber N, de Pury J, et al. New approaches to evaluating complex health and care systems. BMJ 2016;352:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sani F, Madhok V, Norbury M, et al. Greater number of group identifications is associated with healthier behaviour: Evidence from a Scottish community sample. Br J Health Psychol 2015;20:466–81. 10.1111/bjhp.12119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomson LJ, Camic PM, Chatterjee HJ. Social prescribing: A review of community referral schemes. London: University College London, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kinsella S. Social prescribing: A review of the evidence. Wirral: Wirral Council Business & Public Health Intelligence Team, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bickerdike L, Booth A, Wilson PM, et al. Social prescribing: less rhetoric and more reality. A systematic review of the evidence. BMJ Open 2017;7:e013384 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Friedli L, Themessl-Huber M, Butchart M. Evaluation of Dundee Equally Well Sources of Support: Social prescribing in Maryfield Evaluation report four. Dundee: Equally Well Dundee, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garety PA, Craig TK, Dunn G, et al. Specialised care for early psychosis: symptoms, social functioning and patient satisfaction: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2006;188:37–45. 10.1192/bjp.bp.104.007286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greaves CJ, Farbus L. Effects of creative and social activity on the health and well-being of socially isolated older people: outcomes from a multi-method observational study. J R Soc Promot Health 2006;126:134–42. 10.1177/1466424006064303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crawford M, Rutter D, Price K, et al. Learning the lessons: a multi-method evaluation of dedicated community-based services for people with personality disorder: National Co-ordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation R&D (NCCSDO), 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Faulkner M. Supporting the psychosocial needs of patients in general practice: the role of a voluntary referral service. Patient Educ Couns 2004;52:41–6. 10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00247-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grayer J, Cape J, Orpwood L, et al. Facilitating access to voluntary and community services for patients with psychosocial problems: a before-after evaluation. BMC Fam Pract 2008;9:27 10.1186/1471-2296-9-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okin RL, Boccellari A, Azocar F, et al. The effects of clinical case management on hospital service use among ED frequent users. Am J Emerg Med 2000;18:603–8. 10.1053/ajem.2000.9292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stickley T, Eades M. Arts on prescription: a qualitative outcomes study. Public Health 2013;127:727–34. 10.1016/j.puhe.2013.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Innovation Unit. Wigan community link worker service evaluation. London: Innovation Unit, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 38.City and Hackney Clinical Commissioning Group, University of East London. Shine 2014 final report social prescribing: Integrating GP and community assets for health. London: University of East London, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Newcastle West Clinical Commissioning Group. Social prescribing for mental health: an integrated approach project report. Newcastle: Newcastle West Clinical Commissioning Group, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones M, Kimberlee R, Deave T, et al. The role of community centre-based arts, leisure and social activities in promoting adult well-being and healthy lifestyles. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2013;10:1948–62. 10.3390/ijerph10051948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baker K, Irving A. Co-producing approaches to the management of Dementia through social prescribing. Soc Policy Adm 2016;50:379–97. [Google Scholar]

- 42.ERS Research and Consultancy. Newcastle social prescribing project: final report. Newcastle upon Tyne: ERS Research and Consultancy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morton L, Ferguson M, Baty F. Improving wellbeing and self-efficacy by social prescription. Public Health 2015;129:286–9. 10.1016/j.puhe.2014.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huxley P. Arts on prescription: an evaluation. UK: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 45.The Care Forum. New routes: end of project report. Bristol, UK: The Care Forum, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kilroy A, Garner C, Parkinson C, et al. Towards Transformation: exploring the impact of culture, creativity and the arts on health and wellbeing: a consultation report for the critical friends event. Manchester, UK: Arts for Health, Manchester Metropolitan University, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grant C, Goodenough T, Harvey I, et al. A randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation of a referrals facilitator between primary care and the voluntary sector. BMJ 2000;320:419–23. 10.1136/bmj.320.7232.419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.White M, Salamon E. An interim evaluation of the ‘Arts For Well-being’ social prescribing scheme in County Durham. Durham: Centre for Medical Humanities, Durham University, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramsbottom H, Volpe J, Pantelic V. Social prescribing: a model for partnership working between primary care and the voluntary sector. London: Age UK, n.d. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blakeman T, Blickem C, Kennedy A, et al. Effect of information and telephone-guided access to community support for people with chronic kidney disease: randomised controlled trial. PLoS One 2014;9:e109135 10.1371/journal.pone.0109135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liao M-C, Chen L-K, Chou M-Y, et al. Effectiveness of Comprehensive Geriatric assessment-based intervention to reduce Frequent Emergency Department visits: a report of four cases. Int J Gerontol 2012;6:131–3. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vogelpoel N, Jarrold K. Social prescription and the role of participatory arts programmes for older people with sensory impairments. J Integr Care 2014;22:39–50. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dayson C, Bashir N. The social and economic impact of the Rotherham Social Prescribing Pilot: Summary evaluation report. Sheffield: Sheffield Hallam University, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reinius P, Johansson M, Fjellner A, et al. A telephone-based case-management intervention reduces healthcare utilization for frequent emergency department visitors. Eur J Emerg Med 2013;20:327–34. 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e328358bf5a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blickem C, Kennedy A, Jariwala P, et al. Aligning everyday life priorities with people’s self-management support networks: An exploration of the work and implementation of a needs-led telephone-based support systen. BMC Health Services Res 2014;14:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goodhart C, Layzell S, Cook A, et al. Family support in general practice. J R Soc Med 1999;92:525–8. 10.1177/014107689909201009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hudon C, Chouinard MC, Diadiou F, et al. Case management in primary care for frequent users of health care services with chronic diseases: a Qualitative Study of Patient and Family Experience. Ann Fam Med 2015;13:523–8. 10.1370/afm.1867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Skinner J, Carter L, Haxton C. Case management of patients who frequently present to a Scottish emergency department. Emerg Med J 2009;26:103–5. 10.1136/emj.2008.063081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tadros AS, Castillo EM, Chan TC, et al. Effects of an emergency medical services-based resource access program on frequent users of health services. Prehosp Emerg Care 2012;16:541–7. 10.3109/10903127.2012.689927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-017734supp001.pdf (172.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-017734supp002.pdf (154.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-017734supp003.pdf (199.2KB, pdf)