Abstract

Objective

Neurological dysfunction remains a devastating postoperative complication in patients undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), and previous studies have shown that inhalation anaesthesia and total intravenous anaesthesia (TIVA) may produce different degrees of cerebral protection in these patients. Therefore, we conducted a systematic literature review and meta-analysis to compare the neuroprotective effects of inhalation anaesthesia and TIVA.

Design

Searching in PubMed, EMBASE, Science Direct/Elsevier, China National Knowledge Infrastructure and Cochrane Library up to August 2016, we selected related randomised controlled trials for this meta-analysis.

Results

A total of 1485 studies were identified. After eliminating duplicate articles and screening titles and abstracts, 445 studies were potentially eligible. After applying exclusion criteria (full texts reported as abstracts, review article, no control case, lack of outcome data and so on), 13 studies were selected for review. Our results demonstrated that the primary outcome related to S100B level in the inhalation anaesthesia group was significantly lower than in the TIVA group after CPB and 24 hours postoperatively (weighted mean difference (WMD); 95% CI (CI): −0.41(–0.81 to –0.01), −0.32 (−0.59 to −0.05), respectively). Among secondary outcome variables, mini-mental state examination scores of the inhalation anaesthesia group were significantly higher than those of the TIVA group 24 hours after operation (WMD (95% CI): 1.87 (0.82 to 2.92)), but no significant difference was found in arteriovenous oxygen content difference, cerebral oxygen extraction ratio and jugular bulb venous oxygen saturation, which were assessed at cooling and rewarming during CPB.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that anaesthesia with volatile agents appears to provide better cerebral protection than TIVA for patients undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB, suggesting that inhalation anaesthesia may be more suitable for patients undergoing cardiac surgery.

Keywords: anaesthesia, cerebral protection, cardiac surgery, cardiopulmonary bypass.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to compare the neuroprotective effects of inhalation anaesthesia and those of total intravenous anaesthesia (TIVA) in cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass.

This study focused on the overall comparison between inhalation anaesthesia and TIVA, different inhalation and intravenous anaesthetics were investigated in the included studies.

The methodological quality of each study was assessed using the Jadad scale for randomised controlled trials. Meta-analysis, heterogeneity test, bias assessment, sensitivity analysis and subgroup analysis were also conducted.

Because of the shortage of reported clinical trials, limited outcome data could be considered for subgroup analysis. The strength of the conclusion is limited by the quality and number of studies.

Introduction

Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) is a necessary and common procedure to support the patient’s circulation during cardiac surgery. Although previous studies1 2 reported that CPB does not increase the postoperative morbidity and mortality in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery, it was demonstrated that the incidence of some postoperative complications for these patients remains high. Neurological dysfunction is one of the most commonly reported postoperative complications in patients undergoing cardiac surgery.3 4 Several factors including cerebral anoxia, embolism, excessive excitatory neurotransmitter release and systemic inflammatory response have been demonstrated to contribute to postoperative neurological dysfunction.5 However, at present, there is no definitive clinical evidence regarding cerebral protection for patients undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB.6 Previous studies on animals support the hypothesis that anaesthetics can produce cerebral protection.7–9 Many recent studies have found that anaesthetic agents may be neuroprotective and may provide cerebral protection to surgery patients.10 11 However, clinical studies show that the relative effects of inhalation anaesthesia or total intravenous anaesthesia (TIVA) on neuroprotection in cardiac surgery with CPB remain controversial and much debated.12–14 Therefore, which option provides better cerebral protection to patients undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB is unknown. As inhalation anaesthesia and TIVA are the most commonly used strategies for general anaesthesia, it is important to clarify this issue. Moreover, as it is difficult to include patients in neurological dysfunction studies for cardiac surgery with CPB, the sample size of these previous studies was generally small. For these reasons, it is necessary to systematically review the available literature and perform a meta-analysis to compare the neuroprotective effects of inhalation anaesthesia and TIVA.

Materials and methods

The current systematic review and meta-analysis was performed according to the reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses reported guidelines for randomised controlled trials.15

Literature search

This meta-analysis was restricted to published studies that investigated the cerebral protective effects of anaesthetics in patients with CPB. The PubMed database, EMBASE, MEDLINE, Science Direct/Elsevier, Cochrane Library and China National Knowledge Infrastructure were searched by two independent reviewers up to August 2016, without restrictions on language or study type. The search terms combined text words and medical subject headings (MeSH) terms. For example, the search terms for CPB were: ‘cardiopulmonary bypass’ and ‘heart lung bypass’. Those for TIVA were: ‘propofol’, ‘disoprofol’, ‘etomidate’, ‘midazolam’, ‘sodium pentothal’, ‘thiopental’ and ‘ketamine’, while those for inhalation anaesthesia were ‘halothane’, ‘sevoflurane’, ‘isoflurane’, ‘desflurane’, ‘enflurane’ and ‘methoxyflurane’. (The MEDLINE search strategy is provided in the (online supplementary appendix), and the finalised MEDLINE search strategy will be adapted to the syntax and subject headings specifications of the other databases.) All relevant articles and abstracts were retrieved. In addition, references cited within relevant reviews were retrieved manually and only full articles were searched in this case.

bmjopen-2016-014629supp001.pdf (7.5KB, pdf)

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Original articles in which all patients undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB were randomly allocated to receive the inhalation anaesthesia or TIVA. Patients underwent cardiac surgery with no restriction on dose and the administration time of anaesthetics.

Exclusion criteria

Case reports, review articles, duplicate publications and studies without outcome data were excluded. Studies involving patients with cerebrovascular disease, central nervous system disorders, use of psychotropic drugs or a history of alcohol or substance abuse were also excluded.

Outcomes

In the included studies, S100B levels in serum were detected before CPB (pre-CPB), after CPB (post-CPB) and 24 hours postoperatively. And the primary outcomes were protein S100B levels in serum post-CPB and 24 hours postoperatively. The secondary outcomes included mini-mental state examination (MMSE) scores assessed preoperatively and 24 hours postoperatively, the jugular bulb venous oxygen saturation (SjvO2), arteriovenous oxygen content difference (D(a-v)O2) and cerebral oxygen extraction ratio (O2ER) were tested at cooling and rewarming during CPB.

Study selection and validity assessment

Study selection was completed by two independent reviewers by screening abstracts and titles of all included papers from the literature search. All the relevant papers were retrieved according to the inclusion criteria. Then based on the abstracts and titles, the second screening of full texts was performed to check if there was an ambiguous decision. Only randomised controlled trials were included in the analysis. Disagreements were resolved through consensus or by a third reviewer. According to the primary criteria for randomised and controlled trials, quality assessment was performed by two reviewers.

Data extraction and statistical analysis

Three reviewers extracted all data recorded as authors, publication year, number of cases, mean age of participants, anaesthetics, study setting and outcomes. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus. In the study, meta-analysis was performed using Review Manager (RevMan) software (V.5.2, Nordic Cochrane Centre, Cochrane Collaboration, 2012, Copenhagen, Denmark) by two reviewers.

The weighted mean differences (WMD) of outcomes in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and their 95% CI were presented. Heterogeneity across studies was tested by the p value and the I 2 statistic, which is a qkuantitative measure of inconsistency.16 A random-effects model was used to analyse the summary estimate when the p value was <0.1 or the I 2 value was >50%. Otherwise, a fixed-effects model was applied. In the meta-analysis, potential publication bias was detected by Egger test. Publication bias was assumed existed if the p<0.05.

Results

Characteristics of the included studies

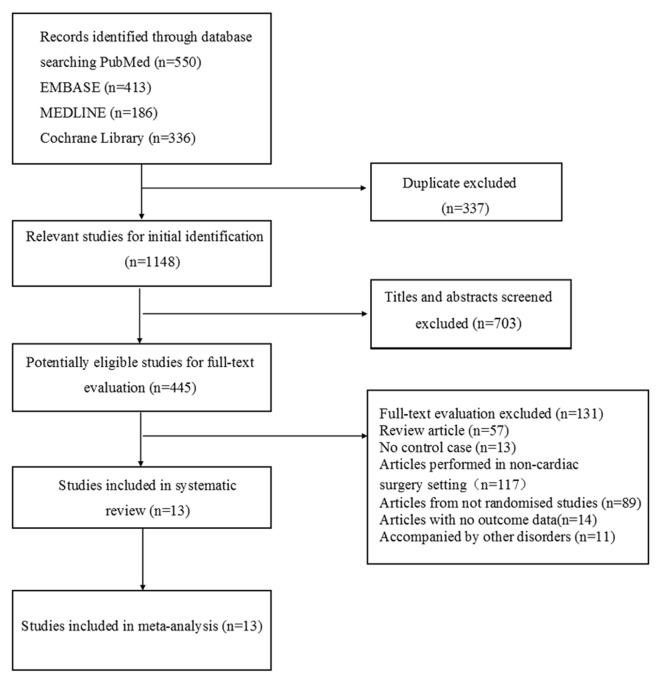

A total of 1485 studies were retrieved. Of these, 1148 remained after duplicate articles were eliminated. After screening titles and abstracts, 445 studies were potentially eligible. Based on the exclusion criteria, 13 studies were ultimately selected (figure 1). All reviewers agreed to include all 13 papers. Although all of these RCTs were considered to have a low risk of bias, nine studies included no details on the method of random sequence generation and allocation.17–25 Only one study provided the details about the blinding of the data collection.26

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for the selection of eligible studies.

‘Inhalation anaesthesia’ was defined as a group receiving a volatile agent like isoflurane, sevoflurane or desflurane. In the included studies, patients in the ‘volatile anaesthesia’ group had not received propofol, thiopental or ketamine during the surgery and CPB. The patients in the ‘TIVA’ group had received only intravenous anaesthetics, but not volatile agents. These studies involved 549 patients, including 272 patients with inhalation anaesthesia and 277 patients with TIVA (table 1). Patients’ age ranges in ‘inhalation anaesthesia’ and ‘TIVA’ groups were 44–75 years and 43–74 years, respectively. The mean age of patients was unavailable for three studies.17–19 All the articles had reported exclusion/inclusion criteria.17–29 Of these, seven studies had used isoflurane versus TIVA,17 19–21 23 24 27 four studies had used sevoflurane versus TIVA18 22 25 26 and two studies had used desflurane versus TIVA28 29 in patients.

Table 1.

Study characteristics of the included studies

| Study | Mean age(no. inhalation/TIVA) | Setting | Case | Volatile agents | Comparator | Outcomes |

| Min and Yanlin 200717 | 36–62 | CPB-cardiac surgery | 15/15 | Isoflurane | Propofol | SjvO2%, CBP time |

| Huaping 201518 | 40–65 | CPB-cardiac valve replacement | 15/15 | Sevoflurane | Propofol | S100B,MMSE |

| Lei et al 201019 | 60–70 | CPB-CABG | 15/15 | Isoflurane | Propofol | S100B |

| Newman et al 1998 20 | 56±12/61±14 | CPB-cardiac valve replacement | 16/15 | Isoflurane | Thiopental | CBF,CMRO2,D*a-v)O2,O2ER%,SjvO2%,CBP time |

| Woodcock et al 198721 | 55.5±9.9/63.1±6.5 | CPB-CABG | 16/21 | Isoflurane | Thiopental | CBF,CMRO2, CBP time |

| Guçlu et al 201422 | 57.37±9.8/57.33±7.2 | CPB-cardiac surgery | 10/10 | Sevoflurane | Midazolam | CBP time |

| Kanbak et al 200427 | 56±7.6/54.5±5.9 | CPB-CABG | 20/20 | Isoflurane | Propofol | S100B, CBP time |

| Baki et al 201328 | 64.57±10.84/66.45±13.04 | CPB-CABG | 60/61 | Desflurane | Propofol | S100B,CBP time |

| Singh et al 201126 | 60.10±7.9/59.54±8.83 | CPB-CABG | 15/15 | Sevoflurane | Midazolam | S100B,CBP time |

| Tingting et al 200723 | 52±5/48±7 | CPB-cardiac valve replacement | 20/20 | Isoflurane | Propofol | S100B,D*a-v)O2,O2ER%,SjvO2%,CBP time |

| Jianrong et al 200924 | 44±8/43±7 | CPB-cardiac valve replacement | 30/30 | Isoflurane | Propofol | S100B,D*a-v)O2,O2ER%,SjvO2%,CBP time |

| Shudong 201525 | 49.5±2.6/49.1±2.4 | CPB-cardiac valve replacement | 15/15 | Sevoflurane | Propofol | S100B,MMSE |

| Jiying et al 201029 | 75±5/74±4 | CPB-CABG | 25/25 | Desflurane | Ketamine | S100B,MMSE |

CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CBF, cerebral blood flow; CMRO2, cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen consumption; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; D(a-v)O2, arteriovenous oxygen content difference; MMSE, mini-mental state examination;O2ER, cerebral oxygen extraction; SjvO2, jugular bulb venous oxygen saturation; TIVA, total intravenous anaesthesia.

Methodology quality of the included trials

Methodology quality of the included studies was assessed using a modified Jadad scale. A score of 4–7 indicated a high-quality study, and a score of 1–3 indicated a low-quality study. Of the 13 included studies, 10 received scores of 1–3 and 3 received scores of 4–7 (table 2).

Table 2.

Methodology quality of the included RCTs

| Study | Jadad score | ||||

| Randomisation | Allocation concealment | Blinding | Attrition | Score | |

| Min and Yanlin 200717 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Huaping 201518 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Lei et al 201019 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Newman et al 199820 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Woodcock et al 198721 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Guçlu et al 201422 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Kanbak et al 200427 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Baki et al 201328 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Singh et al 201126 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| Tingting et al 200723 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Jianrong et al 200924 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Shudong 201525 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Jiying et al 201029 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

RCTs, randomised controlled trials.

Meta-analysis

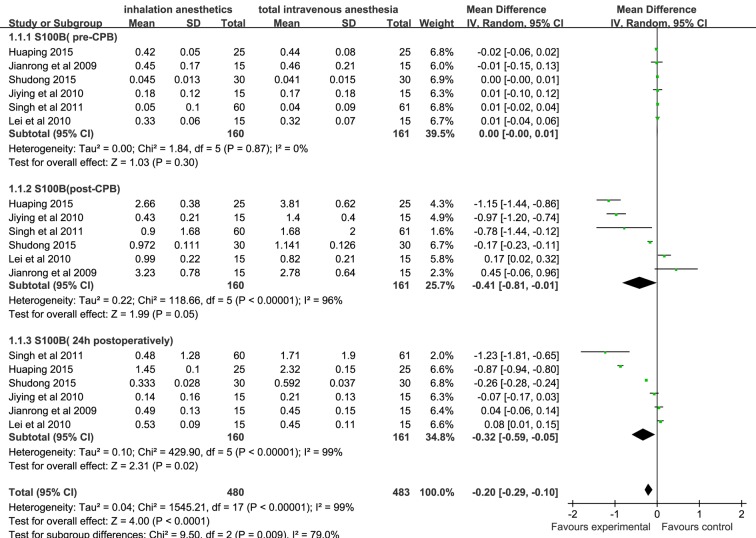

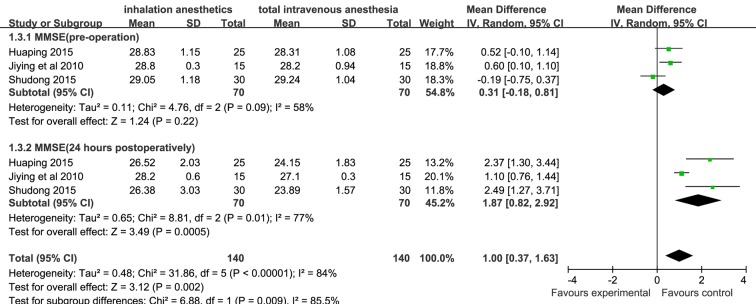

Summary estimate for S100B levels post-CPB and 24 hours postoperatively was analysed in a random-effects model because of the heterogeneity (I 2=96% and I 2=99%, respectively). Based on six studies from 230 patients, S100B levels assessed at the end of CPB and 24 hours postoperatively in the inhalation anaesthesia group were significantly lower than those in the TIVA group (WMD (95% CI): −0.41 (–0.81 to –0.01), −0.32 (−0.59 to −0.05), respectively, figure 2). Based on three studies from 110 patients, postoperative MMSE scores of the inhalation anaesthesia group were significantly higher than those of the TIVA group (WMD (95% CI): 1.87 (0.82 to 2.92)), figure 3]. A significant heterogeneity was detected (I 2=77%), and thus summary estimate was analysed in a random-effects model.

Figure 2.

Forest plot showing the meta-analysis outcomes of the difference in S100B levels of inhalation anaesthesia and TIVA groups. TIVA, total intravenous anaesthesia.

Figure 3.

Forest plot showing the meta-analysis outcomes of the difference in MMSE scores of inhalation anaesthesia and TIVA groups. MMSE, mini-mental state examination; TIVA, total intravenous anaesthesia.

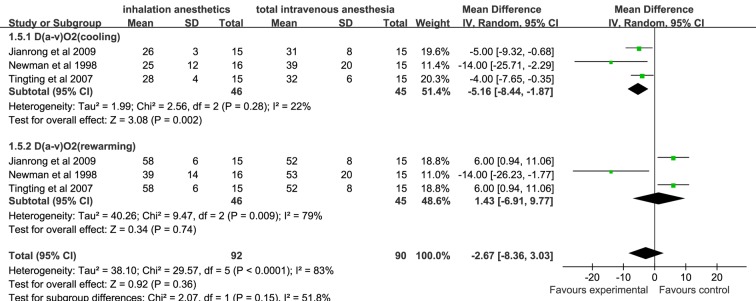

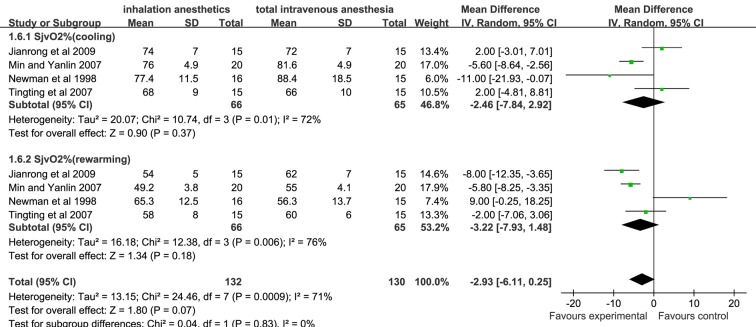

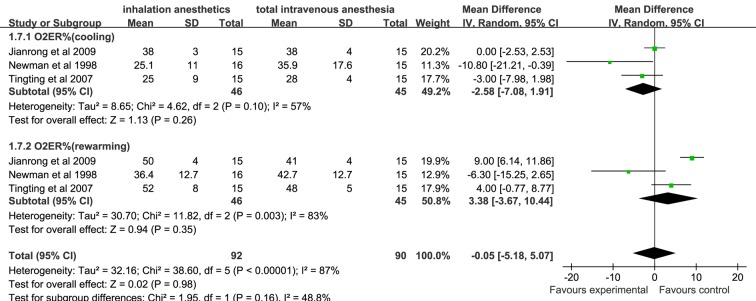

There was no significant difference in D(a-v)O2, O2ER and SjvO2 assessed at cooling and rewarming during CPB between the inhalation anaesthesia group and the TIVA group (figures 4–6).

Figure 4.

Forest plot showing the meta-analysis outcomes of the difference in D(a-v)O2 of inhalation anaesthesia and TIVA groups. D(a-v)O2, arteriovenous oxygen content difference; TIVA, total intravenous anaesthesia.

Figure 5.

Forest plot showing the meta-analysis outcomes of the difference in SjvO2 of inhalation anaesthesia and TIVA groups. SjvO2, jugular bulb venous oxygen saturation, TIVA, total intravenous anaesthesia.

Figure 6.

Forest plot showing the meta-analysis outcomes of the difference in cerebral O2ER of inhalation anaesthesia and TIVA groups. O2ER, oxygen extraction ratio; TIVA, total intravenous anaesthesia.

Egger’s regression test of S100B levels, MMSE scores, D(a-v)O2, O2ER and SjvO2 indicated little evidence of publication bias, respectively (table 3).

Table 3.

Egger test of publication bias

| Std_Eff | Coefficient | SE | t | p>|t| | (95% CI) |

| bias (S100B) | −2.67 | 2.35 | −1.14 | 0.27 | (−7.65 to 2.32) |

| bias (MMSE) | 2.89 | 5.30 | 0.54 | 0.61 | (−10.08 to 15.85) |

| bias(D(a-v)O2) | 186.01 | 99.93 | 1.86 | 0.14 | (−91.44 to 463.46) |

| bias(O2ER%) | 13.87 | 6.58 | 3.63 | 0.12 | (5.59 to 42.14) |

| bias(SjvO2%) | 2.12 | 19.48 | 0.11 | 0.92 | (−45.56 to 49.79) |

D(a-v)O2, arteriovenous oxygen content difference; MMSE, mini-mental state examination; O2ER, cerebral oxygen extraction; SjvO2, jugular bulb venous oxygen saturation.

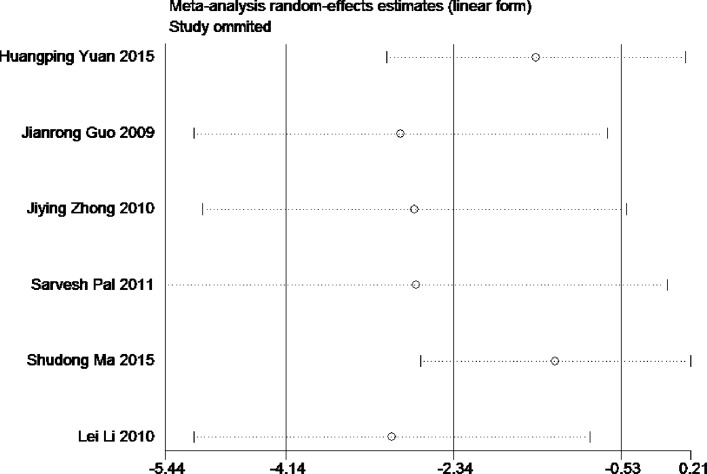

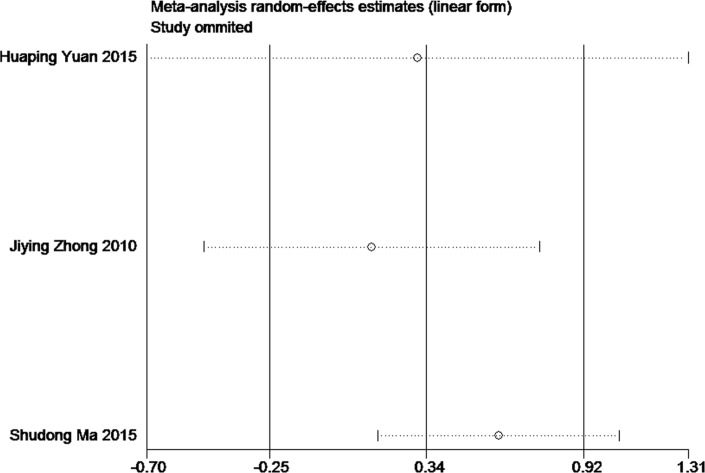

Sensitivity analysis for the current meta-analysis was also performed. We omitted one study in each turn, and calculated the combined WMD for the remaining studies. The results showed that no single study significantly changed the combined results in the overall meta-analysis, indicating that the results were reliable and statistically stable (figures 7 and 8).

Figure 7.

The plot of sensitivity analysis of S100B levels.

Figure 8.

The plot of sensitivity analysis of MMSE scores. MMSE, mini-mental state examination.

Discussion

In our study, 13 published articles were included to determine the difference in the extent of cerebral protection provided by inhalation anaesthesia and TIVA during cardiac surgery with CPB. Eight out of the 13 studies suggested that inhalation anaesthesia might be superior to TIVA in terms of their cerebroprotective effect after CPB.18 20–22 25–27 29 However, the results reported in other five studies were the opposite.17 19 23 24 28 These results underline the existing debate on which anaesthetic approach is better for the patients. However, in the current systematic review and meta-analysis, the results of primary and secondary outcomes showed that inhalation anaesthesia might be superior to TIVA during cardiac surgery with CPB.

S100B is mainly expressed in the astrocytes, and blood S100B level is commonly used as an outcome parameter for evaluating the postoperative neurological dysfunction.30 Its level in the blood has been shown to increase in patients after ischaemic stroke and brain trauma.31 Serum S100B has also been detected after cardiac surgery complicated by neurological injury in adults; thus, it has the potential to serve as an early marker of brain damage.32 33 In this meta-analysis, the serum level of S100B after CPB in the inhalation anaesthesia group was found to be significantly lower than that in the TIVA group (p<0.05),18 25–27 29 suggesting that inhalation anaesthetics provide better cerebral protection than TIVA against brain damage.

As reported by Svenmarker et al,34 it is inevitable that S100B contamination will occur due to the pericardial suction blood, which is often retransfused or processed in the cell saver and then retransfused during CPB. However, a strict control of clinical procedures may decrease its potential effect on the difference of S100B detection between the two groups. In the included studies, the use of retransfusion and cell salvage were not mentioned. Therefore, the possible effect of retransfusion and cell salvage should not be neglected, and this is a potential limitation of the current study.

Among the secondary outcomes, the MMSE is one of the most commonly used parameters for the clinical evaluation of cognitive function. Our results show that postoperative MMSE scores of patients in the inhalation anaesthesia group were significantly higher than those in the TIVA group (p<0.05).18 25 29 These results suggest that inhalation anaesthesia is better than TIVA in terms of protecting the postoperative cognitive function of patients undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB. The meta-analysis also showed that the other outcomes such as D(a-v)O2, O2ER and SjvO2 were not significantly different for TIVA and inhalation anaesthesia groups. However, we found that in some studies, the cerebral oxygen metabolic rate (CMRO2) in patients receiving inhalation anaesthetics assessed at cooling and rewarming during CPB was consistently lower than that in patients receiving TIVA.20 21 Additionally, the intraoperative cerebral blood flow (CBF) assessed at cooling and rewarming during CPB in the inhalation anaesthesia group was significantly higher than that in the TIVA group.20 21 A low ratio of global cerebral oxygen and adequate cerebral blood supply is an important parameter for evaluating cerebral protection.35 Thus, these results based on CMRO2 and CBF can strengthen the finding that inhalation anaesthesia may provide better neuroprotection than TIVA.

Experimental data suggest that inhalation anaesthetics’ positive effects may be caused by preconditioning or postconditioning mechanisms,36 37 which attenuate apoptosis and necrosis of cerebral neurons, thereby reducing neurological dysfunction after ischaemia. Moreover, inhalation agents in preserving satisfactory haemodynamics may contribute to the adequate perfusion and oxygenation of other organ systems,38–41 and thus to improve the patients’ recovery and survival after surgery. Because of the neuroprotection that induced by anaesthetic can be long lasting,42 43 all these effects can be expanded well beyond the immediate perioperative period. Additionally, a recent meta-analysis found that in cardiac surgery,44 as compared with TIVA, inhalation anaesthesia was associated with major benefits in outcome, including reduced mortality, as well as a lower incidence of pulmonary and other complications. Therefore, based on previous findings and the current meta-analysis, it is speculated that inhalation anaesthesia has the potential to serve as a preferential anaesthesia strategy for cardiac patients.

Our study has few limitations. First, the sample size of the included studies was relatively small and the total number of cases is very limited. Second, there was heterogeneity in some of our results. As trials were based in different countries and hospitals, we were unable to avoid the effects of race, age, gender and underlying disease(s) of patients in our study. Therefore, findings of the current study were limited by the overall low quality of evidence and the lack of robust data. Third, our study focused on the overall comparison between inhalation anaesthesia and TIVA, and different inhalation (isoflurane, desflurane or sevoflurane) and intravenous (sodium thiopental, propofol and so on) anaesthetics were investigated in the included studies. Because of the limited number of reported clinical trials, limited outcome data could be considered for subgroup analysis. Therefore, further studies with larger sample sizes are needed to demonstrate which anaesthetics are more beneficial for cardiac patients.

In summary, the results of this meta-analysis indicate that the cerebroprotective effect of inhalation anaesthesia is better than that of TIVA in patients undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB. Further high-quality trials with larger sample sizes are warranted to investigate the effect of anaesthetics on cerebral protection.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: FC, HL and ZZ: conceived and designed the experiments. FC, GD, ZW and ZZ: performed the experiments. FC, GD and ZW: analysed the data. ZZ and HL: contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools. FC, GD, HL, ZZ: wrote the paper. All authors: reviewed the manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81571870) and the NaturalScience Foundation Project of Chongqing (cstc20136jjB10026).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Lamy A, Devereaux PJ, Prabhakaran D, et al. Effects of off-pump and on-pump coronary-artery bypass grafting at 1 year. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1179–88. 10.1056/NEJMoa1301228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lamy A, Devereaux PJ, Prabhakaran D, et al. Five-Year Outcomes after Off-Pump or On-Pump Coronary-Artery Bypass Grafting. N Engl J Med 2016;375:2359–68. 10.1056/NEJMoa1601564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McKhann GM, Grega MA, Borowicz LM, et al. Stroke and encephalopathy after cardiac surgery: an update. Stroke 2006;37:562–71. 10.1161/01.STR.0000199032.78782.6c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hogue CW, Palin CA, Arrowsmith JE. Cardiopulmonary bypass management and neurologic outcomes: an evidence-based appraisal of current practices. Anesth Analg 2006;103:21–37. 10.1213/01.ANE.0000220035.82989.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wimmer-Greinecker G, Matheis G, Brieden M, et al. Neuropsychological changes after cardiopulmonary bypass for coronary artery bypass grafting. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1998;46:207–12. 10.1055/s-2007-1010226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Blumenthal JA, Mahanna EP, Madden DJ, et al. Methodological issues in the assessment of neuropsychologic function after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 1995;59:1345–50. 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00055-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pape M, Engelhard K, Eberspächer E, et al. The long-term effect of sevoflurane on neuronal cell damage and expression of apoptotic factors after cerebral ischemia and reperfusion in rats. Anesth Analg 2006;103:173–9. 10.1213/01.ane.0000222634.51192.a4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sakai H, Sheng H, Yates RB, et al. Isoflurane provides long-term protection against focal cerebral ischemia in the rat. Anesthesiology 2007;106:92–9. 10.1097/00000542-200701000-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Selman WR, Spetzler RF, Roessmann UR, et al. Barbiturate-induced coma therapy for focal cerebral ischemia. Effect after temporary and permanent MCA occlusion. J Neurosurg 1981;55:220–6. 10.3171/jns.1981.55.2.0220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Iwata T, Inoue S, Kawaguchi M, et al. Comparison of the effects of sevoflurane and propofol on cooling and rewarming during deliberate mild hypothermia for neurosurgery. Br J Anaesth 2003;90:32–8. 10.1093/bja/aeg016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dabrowski W, Rzecki Z, Czajkowski M, et al. Volatile anesthetics reduce biochemical markers of brain injury and brain magnesium disorders in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2012;26:395–402. 10.1053/j.jvca.2011.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sagara Y, Hendler S, Khoh-Reiter S, et al. Propofol hemisuccinate protects neuronal cells from oxidative injury. J Neurochem 1999;73:2524–30. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0732524.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang H, Lu S, Yu Q, et al. Sevoflurane preconditioning confers neuroprotection via anti-inflammatory effects. Front Biosci 2011;3:604–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McAuliffe JJ, Loepke AW, Miles L, et al. Desflurane, isoflurane, and sevoflurane provide limited neuroprotection against neonatal hypoxia-ischemia in a delayed preconditioning paradigm. Anesthesiology 2009;111:533–46. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181b060d3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539–58. 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Min J, Yanlin B. Target controlled infusion of propofol in shallow perioperative cardiopulmonary bypass for brain protection. Int J Clin Exp Med 2007;4:120–1. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Huaping Y. Two methods of anesthesia of CPB heart valve replacement patients plasma level and the influence of cognitive function according to beta. Shandong Med 2015;55:71–2. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lei L, Weifu L, Jianchun F, et al. Effects of different anesthesia on cognition function in geriatric patients following off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting. Chin J Geriatr Heart Brain Vessel Dis 2010;12:1002–4. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Newman MF, Croughwell ND, White WD, et al. Pharmacologic electroencephalographic suppression during cardiopulmonary bypass: a comparison of thiopental and isoflurane. Anesth Analg 1998;86:246–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Woodcock TE, Murkin JM, Farrar JK, et al. Pharmacologic EEG suppression during cardiopulmonary bypass: cerebral hemodynamic and metabolic effects of thiopental or isoflurane during hypothermia and normothermia. Anesthesiology 1987;67:218–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Güçlü ÇY, Ünver S, Aydınlı B, et al. The effect of sevoflurane vs. TIVA on cerebral oxygen saturation during cardiopulmonary bypass-randomized trial. Adv Clin Exp Med 2014;23:919–24. 10.17219/acem/37339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tingting C, Gang W, Qi Z, et al. The comparison between isoflurane and propofol with effect on cerebral protection in cardiac valve replacement Surgery. Chin J ECC 2007;5:91-93–117. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jianrong G, Donglin J, Liyuan R, et al. Isoflurane and propofol for extracorporeal circulation open-heart surgery in patients with a comparative study of perioperative cerebral protection. Chin J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2009;14:812–7. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shudong M. Propofol and seven halothane Anesthesia for experacorporeal circulation of brain protection effect comparison. Chin & F Med treatment 2015;12:145–6. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Singh SP, Kapoor PM, Chowdhury U, et al. Comparison of S100β levels, and their correlation with hemodynamic indices in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting with three different anesthetic techniques. Ann Card Anaesth 2011;14:197–202. 10.4103/0971-9784.83998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kanbak M, Saricaoglu F, Avci A, et al. Propofol offers no advantage over isoflurane anesthesia for cerebral protection during cardiopulmonary bypass: a preliminary study of S-100beta protein levels. Can J Anaesth 2004;51:712–7. 10.1007/BF03018431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Baki ED, Aldemir M, Kokulu S, et al. Comparison of the effects of desflurane and propofol anesthesia on the inflammatory response and s100β protein during coronary artery bypass grafting. Inflammation 2013;36:1327–33. 10.1007/s10753-013-9671-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jiying Z, Feng X, Xianjie W, et al. Brain protection of desflurane in old patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. Chin J New Drugs Clin Rem 2010;29:847–9. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang DD, Bordey A. The astrocyte odyssey. Prog Neurobiol 2008;86:342–67. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.09.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. An SA, Kim J, Kim OJ, et al. Limited clinical value of multiple blood markers in the diagnosis of ischemic stroke. Clin Biochem 2013;46:710–5. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2013.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kuzumi E, Vuylsteke A, Guo X, et al. Serum S100 protein as a marker of cerebral damage during cardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth 2000;85:936–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rasmussen LS, Christiansen M, Eliasen K, et al. Biochemical markers for brain damage after cardiac surgery - time profile and correlation with cognitive dysfunction. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2002;46:547–51. 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2002.460512.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Svenmarker S, Engström KG, Karlsson T, et al. Influence of pericardial suction blood retransfusion on memory function and release of protein S100B. Perfusion 2004;19:337–43. 10.1191/0267659104pf768oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Goldman S, Sutter F, Ferdinand F, et al. Optimizing intraoperative cerebral oxygen delivery using noninvasive cerebral oximetry decreases the incidence of stroke for cardiac surgical patients. Heart Surg Forum 2004;7:E376–E381. 10.1532/HSF98.20041062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McMurtrey RJ, Zuo Z. Isoflurane preconditioning and postconditioning in rat hippocampal neurons. Brain Res 2010;1358:184–90. 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lee JJ, Li L, Jung HH, et al. Postconditioning with isoflurane reduced ischemia-induced brain injury in rats. Anesthesiology 2008;108:1055–62. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181730257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Julier K, da Silva R, Garcia C, et al. Preconditioning by sevoflurane decreases biochemical markers for myocardial and renal dysfunction in coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a double-blinded, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. Anesthesiology 2003;98:1315–27. 10.1097/00000542-200306000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kim M, Kim M, Kim N, et al. Isoflurane mediates protection from renal ischemia-reperfusion injury via sphingosine kinase and sphingosine-1-phosphate-dependent pathways. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2007;293:F1827–F1835. 10.1152/ajprenal.00290.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lee HT, Kim M, Kim J, et al. TGF-beta1 release by volatile anesthetics mediates protection against renal proximal tubule cell necrosis. Am J Nephrol 2007;27:416–24. 10.1159/000105124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Beck-Schimmer B, Breitenstein S, Urech S, et al. A randomized controlled trial on pharmacological preconditioning in liver surgery using a volatile anesthetic. Ann Surg 2008;248:909–18. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818f3dda [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Li H, Yin J, Li L, et al. Isoflurane postconditioning reduces ischemia-induced nuclear factor-κB activation and interleukin 1β production to provide neuroprotection in rats and mice. Neurobiol Dis 2013;54 216–24. 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.12.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zuo Z. A novel mechanism for sevoflurane preconditioning-induced neuroprotection. Anesthesiology 2012;117:942–4. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31826cb48c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Uhlig C, Bluth T, Schwarz K, et al. Effects of Volatile Anesthetics on Mortality and Postoperative Pulmonary and Other Complications in Patients Undergoing Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Anesthesiology 2016;124:1230–45. 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-014629supp001.pdf (7.5KB, pdf)