Abstract

An association between periodontitis and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has been reported by experimental animal and epidemiologic studies. This study investigated whether circulating levels of serum C-reactive protein (CRP) and a weighted genetic CRP score representing markers of inflammatory burden modify the association between periodontitis and NAFLD. Data came from 2,481 participants of the Study of Health in Pomerania who attended baseline examination that occurred between 1997 and 2001. Periodontitis was defined as the percentage of sites (0%, <30%, ≥30%) with probing pocket depth (PD) ≥4 mm, and NAFLD status was determined using liver ultrasound assessment. Serum CRP levels were assayed at a central laboratory, and single-nucleotide polymorphisms previously identified through genome-wide association studies as robustly associated with serum CRP were combined into a weighted genetic CRP score (wGSCRP). Logistic regression models estimated the association between periodontitis and NAFLD within strata of serum CRP and separately within strata of the wGSCRP. The prevalence of NAFLD was 26.4% (95% confidence interval [CI], 24.6, 28.1) while 17.8% (95% CI, 16.0–19.6) had ≥30% of sites with PD ≥4 mm. Whereas the wGSCRP was not a modifier (Pinteraction = 0.8) on the multiplicative scale, serum CRP modified the relationship between periodontitis and NAFLD (Pinteraction = 0.01). The covariate-adjusted prevalence odds ratio of NAFLD comparing participants with ≥30% of sites with PD ≥4 mm to those with no site affected was 2.39 (95% CI, 1.32–4.31) among participants with serum CRP <1 mg/L. The corresponding estimate was 0.97 (95% CI, 0.57–1.66) for participants with serum CRP levels of 1 to 3 mg/L and 1.12 (95% CI, 0.65–1.93) for participants with serum CRP >3 mg/L. Periodontitis was positively associated with higher prevalence odds of NAFLD, and this relationship was modified by serum CRP levels.

Keywords: periodontal disease, epidemiology, genetic score, C-reactive protein, inflammatory mediator, hepatic steatosis

Introduction

In response to an injury or infection, inflammation occurs as a complex series of short-term adaptive responses accompanied by local tissue damage with manifestations that gradually resolves as inflammation abates, leaving little to no permanent damage (Kumar et al. 2014). Inflammation is regulated primarily by the innate immune system (Takashiba and Naruishi 2006; Kumar et al. 2014), and it involves a coordinated cascade of biological events regulated by specific cells and molecular signals (Naitza et al. 2012).

An excessive inflammatory response that occurs upon stimulation of the innate immune system has been described as a hyperresponsive trait (Shaddox et al. 2010) that presents systemically as a heightened expression of systemic markers of inflammation (Southerland et al. 2006). Population-based genetic studies suggest that natural selection has shaped the evolution of the innate immunity with specific focus on inflammatory genes that are pivotal in host-pathogen interactions (Barreiro and Quintana-Murci 2010). Inflammatory biomarkers are reported to be highly heritable, with studies among ethnically homogeneous groups and twins indicating that about half of interindividual variability in markers of inflammation is genetically determined (Pankow et al. 2001; Dupuis et al. 2005). For instance, the Framingham Heart Study reported age- and sex-adjusted heritability of 25.3%, 25.4%, and 45.2% for C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin 6 (IL-6), and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1), respectively (Dupuis et al. 2005), while the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Family Heart Study reported heritability ranging from 35% to 40% for CRP, white blood cells, and albumin (Pankow et al. 2001; Dupuis et al. 2005).

Findings among humans and from mice models (Yoneda et al. 2012) suggest a relationship between periodontitis and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), both of which are chronic health conditions characterized by a heightened inflammatory burden (Day and James 1998; Haukeland et al. 2006; Targher 2006; Tilg and Moschen 2010; Schenkein and Loos 2013; Gocke et al. 2014). Indeed, individuals with periodontitis present with frequent bacteremia (Schenkein and Loos 2013) that promotes a proinflammatory state, while obesity, a precursor for NAFLD, is characterized by a state of chronic low-grade systemic inflammation (Shoelson et al. 2006; Ouchi et al. 2011).

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified 19 independent loci that are robustly associated with CRP levels (Dehghan et al. 2011; Naitza et al. 2012), an acute phase reactant, and a marker of systemic inflammation (Pearson et al. 2003; Raman et al. 2013). Because genetic determinants of inflammatory biomarkers can more accurately indicate lifelong inflammatory status (Raman et al. 2013) compared to biomarker concentrations obtained at a given point in time, polymorphisms in genes regulating inflammatory processes may influence the expression of periodontitis and NAFLD, as well as modify the relationship between these 2 conditions.

The purpose of this investigation was to determine whether CRP-associated genetic loci and serum CRP levels modify the association between periodontitis and NAFLD.

Methods

Data Source

The Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP) is a population-based cohort sampled from the Western Pomeranian region of northeastern Germany (John et al. 2001; Volzke et al. 2011). The SHIP was designed to provide prevalence estimates for various diseases and disease risk factors, incidence of common risk factors, subclinical disorders, and clinical diseases and to evaluate associations among these factors. From eligible inhabitants of West Pomerania in 1996, 6,265 adults aged 20 to 79 y were invited to participate. A total of 4,308 participated in the baseline examination conducted between 1997 and 2001. Study participants underwent rigorous examinations, and interviewer-administered questionnaires were used to collect information on relevant covariates. Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the institutional review board of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and this study conformed to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for reporting observational studies.

Exposure Assessment and Definition

Dental examiners performed periodontal examination on study participants with no medical contraindication. Measurements of probing pocket depth (PD) and clinical attachment level (CAL) were obtained on 4 sites per tooth: distobuccal, mesiobuccal, midbuccal, and midlingual or midpalatal (except the third molars) on 2 quadrants (quadrants 1 and 4 or quadrants 2 and 3). For this investigation, periodontitis was defined as the proportion of periodontal sites with PD ≥4 mm categorized as none (0%), moderate (<30%), and extensive (≥30%). In a secondary analysis, periodontitis was investigated as the proportion of sites with CAL ≥3 mm (none, moderate, and extensive) and according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention–American Association for Periodontology (CDC-AAP) criteria that define severe periodontitis as ≥2 interproximal sites with CAL of ≥6 mm (not on the same tooth) and ≥1 interproximal sites with PD of ≥5 mm, and moderate periodontitis as ≥2 interproximal sites (not on the same tooth) with CAL of ≥4 mm or ≥2 interproximal sites (not on the same tooth) with PD of ≥5 mm (Page and Eke 2007). Individuals with moderate or severe periodontitis were categorized as having periodontitis, while participants not meeting these criteria were categorized as healthy/mild.

Outcome Assessment and Definition

Trained physicians performed liver ultrasound on study participants using a 7.5-MHz transducer (John et al. 2001; Volzke et al. 2011). A positive finding on ultrasound was defined as a significant increase in liver echogenicity (brightness) relative to the kidneys, with the diaphragm indistinct or the echogenic walls of the portal veins invisible (Baumeister et al. 2008; Williams et al. 2011).

Covariates

Covariates identified as confounders were determined after analyzing a directed acyclic graph (Greenland et al. 1999) and included age modeled with a quadratic term, sex, alcohol consumption in the past 30 days, and waist circumference, dichotomized at ≥88 cm for women and ≥102 cm for men and is indicative of abdominal obesity (Grundy et al. 2005). Diabetes was based on self-reported physician’s diagnosis or study’s measurement of hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) ≥6.5%. Self-reported smoking status was categorized as never, former, and current. Physical activity was based on self-report of the number of hours per week of moderate physical activity.

Laboratory Measurements

Nonfasting blood samples were drawn from the cubital vein in the supine position. HbA1c was measured by high-performance liquid chromatography (ClinRep HbA1C, Recipe Chemicals Instruments GmbH), while serum levels of high-sensitivity CRP (hs-CRP) were estimated with the Behring Nephelometer II (Dade Behring) (Gocke et al. 2014).

Genotyping

Genomic DNA from blood samples was collected using standardized procedures. Blood aliquots were immediately placed on ice after collection and stored at −80°C in a biobank (John et al. 2001). A total of 4,096 samples were genotyped using the Human SNP 6.0 Array (Affymetrix) with overall genotyping efficiency of 98.6% and imputed to the 1000 Genomes v3 reference panel released March 2012 (ALL ancestries panel, build 37) (Volzke et al. 2011; Teumer et al. 2013).

A total of 19 CRP single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from 19 loci, 1 IL-6 SNP, 2 MCP-1 SNPs, and 2 erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) SNPs were identified as genetic markers of inflammation for this investigation. After quality control analysis, genotype data were available for 4,070 participants. None of the SNPs deviated significantly from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P > 0.003), and call rates were >95% for all SNPs.

CRP-Specific Weighted Genetic Score

To study the cumulative effect of multiple gene loci, a weighted genetic score for CRP was computed for each study participant. A risk allele was defined as the allele associated with a unit increase in log-transformed serum CRP level. The corresponding effect sizes from previous GWAS of inflammatory mediators (Naitza et al. 2012) and a meta-analysis of GWAS of CRP levels (Dehghan et al. 2011) were used to weigh the contribution of each risk allele within the weighted genetic CRP score (wGSCRP) as previously described (Pharoah et al. 2008) and implemented (Thanassoulis et al. 2012; Xiao et al. 2015). The lead SNP in each identified locus were used in creating the weighted genetic score. The list of SNPs and effect sizes (β estimates) are presented in Appendix Table 1. The weighted genetic score for CRP was calculated as follows:

where αk is the per-allele β estimate associated with the risk allele for CRP SNP k, and Xk is the number of risk alleles for the same SNP, and n is total number of SNPs used in creating the genetic score. In addition to CRP, weighted genetic scores were also created for IL-6, MCP-1, and ESR.

Exclusions

From 4,308 eligible participants at baseline, participants with no genotype data (n = 238) were excluded. Also excluded were participants who reported excessive alcohol consumption, defined as 70 g of ethanol/wk (equivalent to 1 standard drink/day) for women and 140 g of ethanol/wk (equivalent to 2 standard drinks/day) for men (n = 970). Participants with no liver ultrasound reading (n = 48), as well as those with no periodontal examination (n = 14) or edentulous (n = 563), were also excluded. Also excluded were participants with chronic or autoimmune viral hepatitis as well as those who self-reported use of the following steatosis-promoting medications: tamoxifene, methotrexate, and amiodarone. The resulting analytic sample size was 2,481, noting that some participants were ineligible for multiple reasons.

Statistical Analysis

The respective genetic scores, including the wGSCRP and log-transformed serum CRP levels, were modeled as continuous traits in separate linear regression models investigating whether these traits were associated with periodontitis and NAFLD.

Logistic regression models stratified according to the median value for the wGSCRP (<1.98 vs. ≥1.98) assessed the relationship between periodontitis and NAFLD. In separate stratified analyses, a similar association was investigated within strata of low (<1 mg/L), intermediate (1 to 3 mg/L), and high (>3 mg/L) (Pearson et al. 2003) serum CRP levels. Statistical tests were 2-sided, and the test for statistical significant interaction was set a priori at P < 0.1. Data analysis was conducted in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

The prevalence of NAFLD was 26.4% (95% confidence interval [CI], 24.6%–28.1%), and 52.7% (95% CI, 50.5%–54.8%) had <30% of sites with PD ≥4 mm while 17.8% (95% CI, 16.0%–19.6%) of the SHIP examinees had ≥30% of sites with PD ≥4 mm. Participants with periodontitis (PD ≥4 mm) and those with NAFLD had higher serum CRP levels compared to their counterparts with a healthy periodontium and without NAFLD. The median serum CRPs were 1.48 mg/L (interquartile range [IQR], 0.68–3.01) and 1.82 mg/L (IQR, 0.82–3.90) for participants with <30% and ≥30% of sites with PD ≥4 mm, respectively, and 1.11 mg/L (IQR, 0.51–2.95) for participants with no site with PD ≥4 mm (Table 1). Participants with NAFLD were less likely to report physical activity (33% vs. 49%), equally as likely to consume alcohol, and more likely to be men (58% vs. 41%) than participants without NAFLD (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of Baseline Factors According to the Proportion of Sites with PD ≥4 mm and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Status among Participants of the Study of Health in Pomerania, 1997 to 2001.

| Proportion of Sites with PD ≥4 mm |

NAFLD |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 2,481) | None (0%) (n = 733) | Moderate (<30%) (n = 1,307) | Extensive (≥30%) (n = 441) | No (n = 1,827) | Yes (n = 654) | |

| CRP, mg/L | 1.42 (0.64, 3.01) | 1.11 (0.51, 2.95) | 1.48 (0.68, 3.01) | 1.82 (0.82, 3.90) | 1.20 (0.55, 2.95) | 2.16 (0.99, 4.41) |

| Age, y | 47.0 (34.0, 60.0) | 36.0 (27.0, 56.0) | 47.0 (35.0, 60.0) | 55.0 (46.0, 65.0) | 42.0 (31.0, 57.0) | 56.0 (46.0, 65.0) |

| Waist circumference, cm | 88.0 (77.2, 98.1) | 83.0 (73.0, 94.0) | 89.0 (78.0, 98.0) | 94.0 (84.5, 103) | 84.0 (74.3, 93.8) | 98.5 (90.8, 106) |

| Alcohola | 4.10 (1.31, 6.86) | 4.56 (1.39, 6.71) | 4.09 (1.31, 7.17) | 3.92 (0.65, 6.41) | 4.08 (1.31, 6.86) | 4.28 (0.83, 6.86) |

| Abdominal obesityb | 747 (30.1) | 170 (23.2) | 389 (29.8) | 188 (42.6) | 383 (21.0) | 364 (55.7) |

| Physical activity | 1,099 (44.5) | 388 (53.0) | 586 (45.0) | 125 (28.5) | 881 (48.5) | 218 (33.3) |

| Men | 1,116 (45.0) | 281 (38.3) | 592 (45.3) | 243 (55.1) | 740 (40.5) | 376 (57.5) |

| Smoking | ||||||

| Never | 966 (39.1) | 323 (44.1) | 515 (39.6) | 128 (29.2) | 717 (39.4) | 249 (38.1) |

| Former | 780 (31.6) | 203 (27.7) | 434 (33.4) | 143 (32.7) | 527 (29.0) | 253 (38.7) |

| Current | 726 (29.4) | 207 (28.2) | 352 (27.1) | 167 (38.1) | 574 (31.6) | 152 (23.2) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 465 (18.7) | 98 (13.4) | 248 (19.0) | 119 (27.0) | 226 (12.4) | 239 (36.5) |

| NAFLD | 654 (26.4) | 133 (18.1) | 348 (26.6) | 173 (39.2) | — | — |

Data are presented as No. (%) or median (lower quartile, upper quartile).

CDC-AAP, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention–American Academy of Periodontology; CRP, C-reactive protein; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; PD, pocket depth.

Average number of standard drinks in the past 30 days.

Sex-specific weight circumference defined as ≥88 cm for women and ≥102 cm for men (Grundy et al. 2005).

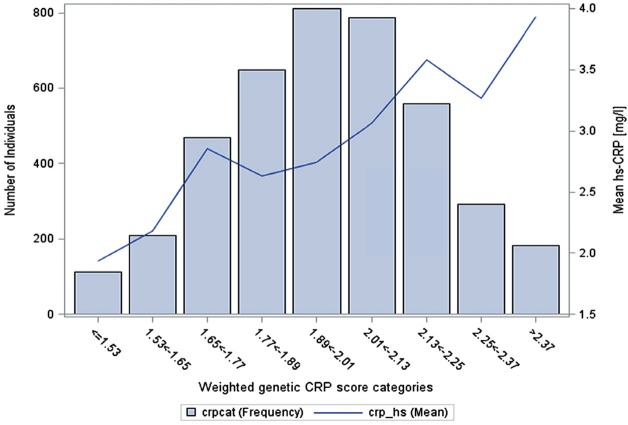

Appendix Table 1 shows the full list of SNPs with the corresponding effect sizes used in creating the respective weighted genetic scores. Most of the CRP SNPs were positively associated with serum CRP levels in this study population (Appendix Fig. 1), and the wGSCRP aligns well with serum CRP levels such that participants with a low genetic CRP score had lower mean serum CRP levels compared to participants with a high genetic CRP score (Fig. 1). The median value for the wGSCRP was 1.98 (IQR, 1.82–2.14). Participants with wGSCRP above the median had a mean (standard deviation [SD]) serum CRP of 3.24 (4.72) mg/L, while participants with wGSCRP at or below the median had a mean (SD) serum CRP of 2.65 (6.62) mg/L.

Figure 1.

Mean serum C-reactive protein (CPR) levels (right vertical axis) shown as solid black line for categories of the weighted genetic CRP score. The shaded bars show the distribution of the weighted CRP score in the study population (left vertical axis). hs, high sensitivity.

As expected, serum CRP was associated with periodontitis. Specifically, each unit increase in log-transformed serum CRP was associated with a 23% increase in adjusted prevalence odds of having ≥30% sites with PD ≥4 mm, prevalence odds ratio [POR] = 1.23 (95% CI, 1.09–1.39), while the corresponding estimate for having <30% of sites with PD ≥4 mm was POR = 1.16 (95% CI, 1.06–1.26) (Table 2). There was no meaningful association between individual CRP SNPs and periodontitis (Appendix Figs. 2–4). Even after combining into a score, the wGSCRP was not associated with the prevalence odds of having <30% sites or ≥30% sites with PD ≥4 mm, POR = 1.02 (95% CI, 0.69–1.51) and 1.01 (95% CI, 0.61–1.69), respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association between Serum CRP and Genetic Determinants of Inflammatory Mediators with Proportion of Sites with PD ≥4 mm and NAFLD in the Study of Health in Pomerania, 1997 to 2001.

| Prevalence Odds Ratio (95% CI) for the Proportion of Sites with PD ≥4 mm (Reference = 0%) |

Prevalence Odds Ratio (95% CI) for NAFLD |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD ≥4 mm | Crude | Adjusteda | Crude | Adjusteda |

| Serum CRPb | ||||

| <30% | 1.19 (1.10–1.29) | 1.16 (1.06–1.26) | 1.49 (1.37–1.61) | 1.26 (1.14–1.39) |

| ≥30% | 1.40 (1.26–1.56) | 1.23 (1.09–1.39) | ||

| Genetic scoresb | ||||

| wGSCRP | ||||

| <30% | 1.02 (0.69–1.51) | 1.21 (0.82–1.78) | ||

| ≥30% | 1.01 (0.61–1.69) | |||

| wGSIL-6 | ||||

| <30% | 0.83 (0.49–1.40) | 0.54 (0.32–0.90) | ||

| ≥30% | 0.60 (0.31–1.19) | |||

| wGSESR | ||||

| <30% | 1.24 (0.53–2.91) | 1.61 (0.69–3.76) | ||

| ≥30% | 0.99 (0.33–3.04) | |||

| wGSMCP | ||||

| <30% | 0.88 (0.60 1.29) | 1.07 (0.73–1.57) | ||

| ≥30% | 1.09 (0.66–1.80) | |||

CI, confidence interval; CRP, C-reactive protein; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; PD, pocket depth; wGSCRP, weighted genetic CRP score; wGSESR, weighted genetic erythrocyte sedimentation rate score; wGSIL-6, weighted genetic interleukin 6 score; wGSMCP, weighted genetic monocyte chemoattractant protein score.

Adjusted for age, sex, waist circumference, smoking, physical activity, alcohol consumption, and diabetes.

Estimate is for each unit increase in the respective genetic scores or log-transformed CRP.

As was observed for periodontitis, each unit increase in log-transformed serum CRP was associated with a higher prevalence odds of NAFLD, with adjusted POR = 1.26 (95% CI, 1.14–1.39) (Table 2). Likewise, most of the individual CRP SNPs had no meaningful effect on the prevalence odds of NAFLD (Appendix Fig. 5), while each unit increase in the wGSCRP was associated with a 21% increase in the prevalence odds of NAFLD; POR = 1.21 (95% CI, 0.82–1.78) (Table 2).

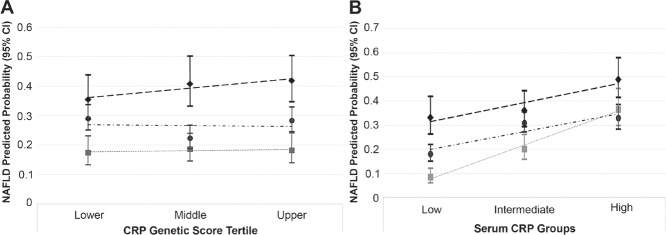

Although participants with periodontitis had a higher predicted probability of NAFLD compared to participants with a healthy periodontium, there was no significant statistical interaction (i.e., effect measure modification on the multiplicative scale) according to tertile of the wGSCRP (Pinteraction = 0.8) (Fig. 2A). Despite this, estimates stratified at the median value for wGSCRP are presented in Table 3. Participants in the stratum of wGSCRP at or below the median had slightly lower unadjusted and covariate-adjusted prevalence odd ratios for the relationship between periodontitis (PD ≥4 mm) and NAFLD compared to participants in the wGSCRP stratum above the median (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Predicted probability of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) according to tertile of the weighted genetic C-reactive protein (CRP) score (A) and categories of serum CRP (B) for study participants with no site (square), <30% of sites (circle), and ≥30% of sites (diamond) with pocket depth ≥4 mm.

Table 3.

Stratified Analysis for the Association between the Proportion of Periodontal Sites with Pocket Depth ≥4 mm (0%, <30%, ≥30%) and NAFLD According to Categories of the Weighted Genetic CRP Score and Serum CRP Levels, in the Study of Health in Pomerania, 1997 to 2001.

| NAFLD, n |

Prevalence Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Noncases | Crude | Adjusteda | |

| wGSCRP ≤1.98 (n = 1,222) | ||||

| No site (0%) | 65 | 292 | Reference | Reference |

| Moderate (<30%) | 166 | 479 | 1.56 (1.13–2.15) | 1.08 (0.75–1.57) |

| Extensive (≥30%) | 81 | 139 | 2.62 (1.78–3.84) | 1.14 (0.72–1.80) |

| wGSCRP >1.98 (n = 1,259) | ||||

| No site (0%) | 68 | 308 | Reference | Reference |

| Moderate (<30%) | 182 | 480 | 1.72 (1.26–2.35) | 1.33 (0.94–1.89) |

| Extensive (≥30%) | 92 | 129 | 3.23 (2.22–4.70) | 1.65 (1.07–2.55) |

| Serum CRP <1 mg/L (n = 972) | ||||

| No site (0%) | 29 | 313 | Reference | Reference |

| Moderate (<30%) | 89 | 402 | 2.40 (1.53–3.73) | 1.62 (1.00–2.61) |

| Extensive (≥30%) | 46 | 93 | 5.34 (3.18–8.97) | 2.39 (1.32–4.31) |

| Serum CRP 1 to 3 mg/L (n = 887) | ||||

| No site (0%) | 48 | 190 | Reference | Reference |

| Moderate (<30%) | 151 | 337 | 1.77 (1.23–2.57) | 1.37 (0.90–2.08) |

| Extensive (≥30%) | 58 | 103 | 2.23 (1.42–3.50) | 0.97 (0.57–1.66) |

| Serum CRP >3 mg/L (n = 622) | ||||

| No site (0%) | 56 | 97 | Reference | Reference |

| Moderate (<30%) | 108 | 220 | 0.85 (0.57–1.27) | 0.70 (0.45–1.10) |

| Extensive (≥30%) | 69 | 72 | 1.66 (1.04–2.65) | 1.12 (0.65–1.93) |

Interaction P value for the genetic CRP score = 0.6. Interaction P value for serum CRP levels = 0.01. CI, confidence interval; CRP, C-reactive protein; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; wGSCRP, weighted genetic score for CRP.

Adjusted for age, sex, waist circumference, smoking, physical activity, alcohol consumption, and diabetes.

In contrast, the higher predicted probability of NAFLD for participants with periodontitis (PD ≥4 mm) differed according to serum CRP levels (Pinteraction = 0.01) (Fig. 2B). And in contrast to the wGSCRP, stratified analyses show a magnitude of unadjusted and covariate-adjusted prevalence odds of NAFLD comparing participants with periodontitis to those without to be highest in the low serum CRP (CRP <1 mg/L) stratum. For instance, the unadjusted and covariate-adjusted NAFLD prevalence odds ratio comparing participants with ≥30% sites with PD ≥4 mm to those with no sites affected in the low-serum CRP (<1 mg/L) stratum were 5.34 (95% CI, 3.18–8.97) and 2.39 (95% CI, 1.32–4.31), respectively, while the corresponding estimates for participants in the high-serum CRP (>3 mg/L) stratum were 1.66 (95% CI, 1.04–2.65) and 1.12 (95% CI, 0.65–1.93), respectively (Table 3).

Contrary to the finding of a significant statistical interaction between serum CRP and PD ≥4 mm, there was no significant interaction with CAL ≥3 mm (Pinteraction = 0.2). This suggests that the significant interaction observed with the CDC-AAP periodontitis classification (Pinteraction = 0.014) appeared to have been driven mostly by PD instead of CAL. Stratified estimates for periodontitis defined as the proportion of sites with CAL ≥3 mm and based on the CDC-AAP criteria are presented in Appendix Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Discussion

Findings from this investigation aimed at assessing whether inflammatory burden of which CRP was used as a marker modified the relationship between periodontitis and NAFLD, were consistent with a positive association between serum CRP and NAFLD as well as serum CRP and periodontitis. Under the premise that genetic determinants of inflammatory markers are better able to indicate lifelong inflammatory status, genetic variants robustly associated with CRP levels were combined into a genetic score that was substituted for serum CRP in this study. Contrary to the findings for serum CRP, the wGSCRP predicted NAFLD to a greater extent than it did for periodontitis. And while serum CRP was a significant modifier, the wGSCRP was not a modifier of the association between periodontitis and NAFLD.

NAFLD has a multifactorial etiology with conditions like insulin resistance and obesity identified as risk factors (Farrell and Larter 2006; Angulo 2007). Increased levels of inflammatory mediators have also been reported in individuals with NAFLD (Haukeland et al. 2006; Targher 2006). While a formal mediation analysis was beyond the scope of this study because of its cross-sectional nature, investigating the periodontitis-NAFLD association conditioning on or stratifying by markers of inflammatory burden while adjusting for confounders and NAFLD risk factors offers insights into the potential role of other factors besides inflammation in NAFLD etiology.

Despite the high CRP heritability (Pankow et al. 2001; Dupuis et al. 2005), currently identified genetic loci explain ~5% of the variation in serum CRP levels (Dehghan et al. 2011). Thus, currently identified loci may not be sufficiently robust to characterize associations or detect gene-environment interactions, even after combining the lead SNPs into a score as was done in this study. This may in part explain why no significant effect measure modification within strata of the genetic CRP score was detected.

Serum CRP represents a systemic marker of an inflammatory response and can be instrumental in detecting effect measure modification. The associations between periodontitis and NAFLD within levels of serum CRP were contrary to expectation. Indeed, the greater magnitude of association in the stratum of serum CRP <1 mg/L suggests a contribution of periodontitis to NAFLD burden independent of chronic low-grade systemic inflammation. This association may have been induced via pathways involving an alteration in the gut microbial composition by swallowed periodontal pathogens (Arimatsu et al. 2014). Furthermore, participants with serum CRP <1 mg/L were less likely to have established NAFLD risk factors like abdominal obesity and diabetes (Appendix Table 4), consistent with an association of periodontitis with NAFLD independent of these factors.

While periodontitis may also contribute to NAFLD burden in the intermediate- and high-serum CRP strata, these associations in opposite of expectation suggest that the effects of periodontitis on NAFLD may be conditioned by a systemic inflammatory response of which CRP is a marker. Alternatively, the higher levels of serum CRP may indicate the presence to a larger extent of competing risk factors for NAFLD (Appendix Table 4), whose effects likely overshadowed those of periodontitis. Last, it is also possible that the high CRP levels may have been generated in response to hepatic injury as a result of NAFLD.

In theory, polymorphisms robustly associated with serum CRP levels are expected to predict an increase in the risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) and other cardiovascular disease–related events. However, these polymorphisms are not associated with an increased risk of CHD (Zacho et al. 2008; Elliott et al. 2009; Dehghan et al. 2011; Wensley et al. 2011), while serum CRP levels have been reported in several longitudinal studies to be associated with increased risk of CHD and myocardial infarction (Danesh et al. 2004; Lange et al. 2006). The SNPs used in creating the genetic CRP score in this study were robustly associated with CRP levels (Appendix Fig. 1), but these SNPs did not independently predict periodontitis or NAFLD risk (Appendix Figs. 2–5). While the findings for the genetic CRP score are not entirely surprising, it is also likely that the inability to detect effect measure modification by the genetic CRP score was also due to the relatively small effect of the individual SNPs even after combining them into a score.

Strengths and Limitations

Given the modest size, this study may be insufficiently powered to detect effect measure modification, especially for the genetic CRP score. In addition, the cross-sectional design makes it difficult to infer how the modification by serum CRP levels might affect the periodontitis-NAFLD association over time. Last, due to the mostly homogeneous study population, findings may not generalize to other racial/ethnic groups especially given that the genetic architecture of CRP differs by ethnicity (Carlson et al. 2005). Study strengths include a good characterization of the cohort that enabled the implementation of relevant exclusions of factors like alcohol consumption that might bias findings if not accounted for. Also, the availability of genotype and phenotype data for CRP allowed an investigation of this factor as a potential effect measure modifier.

Conclusion

Serum CRP was a significant modifier of the relationship between periodontitis and NAFLD, and there was a discordance of effect measure modification of this association by serum CRP and the weighted CRP genetic score. Given that only a fraction of the variability in CRP is explained by currently identified genetic loci, more research may be needed to identify missing CRP heritability that could provide a more robust picture of genetic loci predictive of CRP levels and inflammatory markers in general.

Author Contributions

A.A. Akinkugbe, contributed to conception, design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, drafted and critically revised the manuscript; C.L. Avery, A.S. Barritt, G.D. Slade, T. Kocher, B. Holtfreter, contributed to data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; S.R. Cole, contributed to data analysis, critically revised the manuscript; M. Lerch, J. Mayerle, S. Offenbacher, A. Petersmann, M. Nauck, H. Völzke, contributed to data acquisition, critically revised the manuscript; G. Heiss, contributed to conception, design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants of the Study of Health in Pomerania.

Footnotes

A supplemental appendix to this article is available online.

The Study of Health in Pomerania is part of the Community Medicine Research network of the University of Greifswald, Germany, and funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (grants 01ZZ9603, 01ZZ0103, and 01ZZ0403), the Ministry of Cultural Affairs, and the Social Ministry of the Federal State of Mecklenburg–West Pomerania. Genome-wide data were supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (grant 03ZIK012) and a joint grant from Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany, and the Federal State of Mecklenburg, West Pomerania. The University of Greifswald is a member of the Center of Knowledge Interchange program of the Siemens AG and the Caché Campus program of the InterSystems GmbH. Support for this work was provided by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (grant R03DE025652-01A1).

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Angulo P. 2007. Gi epidemiology: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 25(8):883–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arimatsu K, Yamada H, Miyazawa H, Minagawa T, Nakajima M, Ryder MI, Gotoh K, Motooka D, Nakamura S, Iida T, et al. 2014. Oral pathobiont induces systemic inflammation and metabolic changes associated with alteration of gut microbiota. Sci Rep. 4:4828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreiro LB, Quintana-Murci L. 2010. From evolutionary genetics to human immunology: how selection shapes host defence genes. Nat Rev Genet. 11(1):17–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister SE, Volzke H, Marschall P, John U, Schmidt CO, Flessa S, Alte D. 2008. Impact of fatty liver disease on health care utilization and costs in a general population: a 5-year observation. Gastroenterology. 134(1):85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson CS, Aldred SF, Lee PK, Tracy RP, Schwartz SM, Rieder M, Liu K, Williams OD, Iribarren C, Lewis EC, et al. 2005. Polymorphisms within the C-reactive protein (CRP) promoter region are associated with plasma CRP levels. Am J Hum Genet. 77(1):64–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danesh J, Wheeler JG, Hirschfield GM, Eda S, Eiriksdottir G, Rumley A, Lowe GD, Pepys MB, Gudnason V. 2004. C-reactive protein and other circulating markers of inflammation in the prediction of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 350(14):1387–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day CP, James OF. 1998. Steatohepatitis: a tale of two “hits”? Gastroenterology. 114(4):842–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehghan A, Dupuis J, Barbalic M, Bis JC, Eiriksdottir G, Lu C, Pellikka N, Wallaschofski H, Kettunen J, Henneman P, et al. 2011. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies in >80 000 subjects identifies multiple loci for C-reactive protein levels. Circulation. 123(7):731–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis J, Larson MG, Vasan RS, Massaro JM, Wilson PW, Lipinska I, Corey D, Vita JA, Keaney JF, Jr, Benjamin EJ. 2005. Genome scan of systemic biomarkers of vascular inflammation in the Framingham Heart Study: evidence for susceptibility loci on 1q. Atherosclerosis. 182(2):307–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott P, Chambers JC, Zhang W, Clarke R, Hopewell JC, Peden JF, Erdmann J, Braund P, Engert JC, Bennett D, et al. 2009. Genetic loci associated with C-reactive protein levels and risk of coronary heart disease. JAMA. 302(1):37–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell GC, Larter CZ. 2006. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: from steatosis to cirrhosis. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md). 43(2 Suppl 1):S99–S112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gocke C, Holtfreter B, Meisel P, Grotevendt A, Jablonowski L, Nauck M, Markus MR, Kocher T. 2014. Abdominal obesity modifies long-term associations between periodontitis and markers of systemic inflammation. Atherosclerosis. 235(2):351–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenland S, Pearl J, Robins JM. 1999. Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology. 10(1):37–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, Gordon DJ, Krauss RM, Savage PJ, Smith SC, Jr, et al. 2005. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute scientific statement. Circulation. 112(17):2735–2752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haukeland JW, Damås JK, Konopski Z, Løberg EM, Haaland T, Goverud I, Torjesen PA, Birkeland K, Bjøro K, Aukrust P. 2006. Systemic inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is characterized by elevated levels of Ccl2. J Hepatol. 44(6):1167–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John U, Greiner B, Hensel E, Ludemann J, Piek M, Sauer S, Adam C, Born G, Alte D, Greiser E, et al. 2001. Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP): a health examination survey in an east German region: objectives and design. Soz Praventivmed. 46(3):186–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster JC. 2014. Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease, professional edition: expert consult-online. Philadelphia (PA): Saunders Elsevier Health Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Lange LA, Carlson CS, Hindorff LA, Lange EM, Walston J, Durda JP, Cushman M, Bis JC, Zeng D, Lin D, et al. 2006. Association of polymorphisms in the CRP gene with circulating C-reactive protein levels and cardiovascular events. JAMA. 296(22):2703–2711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naitza S, Porcu E, Steri M, Taub DD, Mulas A, Xiao X, Strait J, Dei M, Lai S, Busonero F, et al. 2012. A genome-wide association scan on the levels of markers of inflammation in Sardinians reveals associations that underpin its complex regulation. Plos Genet. 8(1):e1002480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouchi N, Parker JL, Lugus JJ, Walsh K. 2011. Adipokines in inflammation and metabolic disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 11(2):85–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page RC, Eke PI. 2007. Case definitions for use in population-based surveillance of periodontitis. J Periodontol. 78(7 Suppl):1387–1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankow JS, Folsom AR, Cushman M, Borecki IB, Hopkins PN, Eckfeldt JH, Tracy RP. 2001. Familial and genetic determinants of systemic markers of inflammation: the NHLBI family heart study. Atherosclerosis. 154(3):681–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson TA, Mensah GA, Alexander RW, Anderson JL, Cannon RO, III, Criqui M, Fadl YY, Fortmann SP, Hong Y, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; American Heart Association. 2003. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: application to clinical and public health practice: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 107(3):499–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pharoah PD, Antoniou AC, Easton DF, Ponder BA. 2008. Polygenes, risk prediction, and targeted prevention of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 358(26):2796–2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman K, Chong M, Akhtar-Danesh GG, D’Mello M, Hasso R, Ross S, Xu F, Pare G. 2013. Genetic markers of inflammation and their role in cardiovascular disease. Can J Cardiol. 29(1):67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkein HA, Loos BG. 2013. Inflammatory mechanisms linking periodontal diseases to cardiovascular diseases. J Periodontol. 84(4 Suppl):S51–S69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaddox L, Wiedey J, Bimstein E, Magnuson I, Clare-Salzler M, Aukhil I, Wallet SM. 2010. Hyper-responsive phenotype in localized aggressive periodontitis. J Dent Res. 89(2):143–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoelson SE, Lee J, Goldfine AB. 2006. Inflammation and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 116(7):1793–1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southerland JH, Taylor GW, Moss K, Beck JD, Offenbacher S. 2006. Commonality in chronic inflammatory diseases: periodontitis, diabetes, and coronary artery disease. Periodontol 2000. 40:130–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takashiba S, Naruishi K. 2006. Gene polymorphisms in periodontal health and disease. Periodontol 2000. 40:94–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Targher G. 2006. Relationship between high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels and liver histology in subjects with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 45(6):879–881; author reply 881–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teumer A, Holtfreter B, Volker U, Petersmann A, Nauck M, Biffar R, Volzke H, Kroemer HK, Meisel P, Homuth G, et al. 2013. Genome-wide association study of chronic periodontitis in a general German population. J Clin Periodontol. 40(11):977–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanassoulis G, Peloso GM, Pencina MJ, Hoffmann U, Fox CS, Cupples LA, Levy D, D’Agostino RB, Hwang SJ, O’Donnell CJ. 2012. A genetic risk score is associated with incident cardiovascular disease and coronary artery calcium: the Framingham Heart Study. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 5(1):113–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilg H, Moschen AR. 2010. Evolution of inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: the multiple parallel hits hypothesis. Hepatology. 52(5):1836–1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volzke H, Alte D, Schmidt CO, Radke D, Lorbeer R, Friedrich N, Aumann N, Lau K, Piontek M, Born G, et al. 2011. Cohort profile: the Study of Health in Pomerania. Int J Epidemiol. 40(2):294–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wensley F, Gao P, Burgess S, Kaptoge S, Di Angelantonio E, Shah T, Engert JC, Clarke R, Davey-Smith G, Nordestgaard BG, et al. ; C Reactive Protein Coronary Heart Disease Genetics Collaboration (CCGC). 2011. Association between c reactive protein and coronary heart disease: Mendelian randomisation analysis based on individual participant data. BMJ. 342:d548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams CD, Stengel J, Asike MI, Torres DM, Shaw J, Contreras M, Landt CL, Harrison SA. 2011. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis among a largely middle-aged population utilizing ultrasound and liver biopsy: a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 140(1):124–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Q, Liu ZJ, Tao S, Sun YM, Jiang D, Li HL, Chen H, Liu X, Lapin B, Wang CH, et al. 2015. Risk prediction for sporadic Alzheimer’s disease using genetic risk score in the Han Chinese population. Oncotarget. 6(35):36955–36964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneda M, Naka S, Nakano K, Wada K, Endo H, Mawatari H, Imajo K, Nomura R, Hokamura K, Ono M, et al. 2012. Involvement of a periodontal pathogen, porphyromonas gingivalis on the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 12:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacho J, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Jensen JS, Grande P, Sillesen H, Nordestgaard BG. 2008. Genetically elevated C-reactive protein and ischemic vascular disease. N Engl J Med. 359(18):1897–1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.