Abstract

Herein, we show a direct relationship between the Hantaan virus (HTNV) nucleocapsid (N) protein and the modulation of apoptosis. We observed an increase in caspase-7 and -8, but not -9 in cells expressing HTNV N protein mutants lacking amino acids 270–330. Similar results were observed for the New World hantavirus, Andes virus. Nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) was sequestered in the cytoplasm after tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNF-R) stimulation in cells expressing HTNV N protein. Further, TNF-R stimulated cells expressing HTNV N protein inhibited caspase activation. In contrast, cells expressing N protein truncations lacking the region from amino acids 270–330 were unable to inhibit nuclear import of NF-κB and the mutants also triggered caspase activity. These results suggest that the HTNV circumvents host antiviral signaling and apoptotic response mediated by the TNF-R pathway through host interactions with the N protein.

Introduction

The majority of the members of the Hantavirus genus, family Bunyaviridae, result in serious disease when transmitted by aerosols generated from their rodent reservoirs to humans; Old World hantaviruses can cause hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome, while New World hantaviruses can cause hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (Peters and Khan, 2002; Schmaljohn and Hjelle, 1997; Schmaljohn and Nichol, 2006). Despite differences in clinical manifestations, Old World and New World hantaviruses share highly conserved genomes comprised of three, negative-sensed, single-stranded RNAs. The segments, S, M, and L, encode a nucleocapsid (N) protein, glycoprotein precursor complex (GPC) and L protein, respectively (Schmaljohn and Nichol, 2006). The glycoproteins, Gn and Gc, mediate entry via β-integrin receptors (Gavrilovskaya et al., 1999; Gavrilovskaya et al., 1998), while the L protein plays a dominant role in replication (Flick et al., 2003). The N protein preferentially binds genomic viral RNA to form a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex with each segment (Mir and Panganiban, 2004; Schmaljohn et al., 1983; Severson et al., 1999; Severson, Xu, and Jonsson, 2001).

Virus modulation of apoptosis has been demonstrated for several enveloped RNA viruses such as influenza A, respiratory syncytial, and vesicular stomatitis viruses (Bitko et al., 2007; Gaddy and Lyles, 2007; Mohsin et al., 2002; Sumikoshi et al., 2008; Zamarin et al., 2005) as well as other virus families (Rahman and McFadden, 2006). Apoptosis has been suggested to be induced by Old and New World hantaviruses as well although little is known regarding its role in hantavirus life cycle or the viral protein responsible for the induction. The presence of apoptotic cells has been shown following infection of cells by HTNV, Andes (ANDV), Seoul (SEOV), and Prospect Hill (PHV) viruses (Kang et al., 1999; Li et al., 2004; Markotic et al., 2003). Infection of Vero E6 cells with the Old World viruses, HTNV or Tula virus, shows DNA fragmentation and caspase-8 activation, respectively (Kang et al., 1999; Li et al., 2004). The presence of apoptotic cells has also been observed in one study of Puumala (PUUV) virus-infected patients (Klingstrom et al., 2006) and in the lymphocytes of hamsters infected with ANDV (Wahl-Jensen et al., 2007). The ability of viruses to regulate this host response early in infection may be critical to viral survival. For example, respiratory syncytial virus uses the NS protein to suppress apoptosis early in infection (Bitko et al., 2007). Further, viruses may use apoptosis or cell-death to promote release of virus from cells as noted for numerous non-enveloped viruses (Bauder et al., 2000; Parish et al., 2006; Yun et al., 2005; Zou et al., 2004). Finally, apoptosis may play a role in lung pathogenesis as suggested from limited autopsy specimens from patients who died from infection with the avian influenza A (H5N1) (Uiprasertkul et al., 2007). In general, the ability of a virus to block apoptosis may enhance its ability to replicate and promote pathogenesis. The approach viruses use to block or promote apoptosis varies. For example, some viruses (e.g. hepatitis C, encephalomyocarditis virus) block apoptosis by induction of NF-κB (Marusawa et al., 2001; Romanova et al., 2009; Schwarz et al., 1998). Alternatively, other viruses (e.g. Dengue virus, Sindbis virus) induce NF-κB to promote apoptosis (Lin et al., 1995; Marianneau et al., 1997). NF-κB also plays a major role in generating an immune response to a viral infection (Baeuerle and Henkel, 1994; Barnes and Karin, 1997) as it is activated by cytokines, such as TNF-α, through the TNF receptor family (Kelliher et al., 1998; Lee et al., 2003b). Taylor et al. has recently shown for the HTNV N protein can sequester NF-κB in the cytoplasm, thus inhibiting NF-κB activity (Taylor et al., 2009).

Intriguingly, in studies following our recent hantavirus trafficking experiments (Ramanathan et al., 2007; Ramanathan and Jonsson, 2008), we noted that expression of certain truncations of the N protein caused cell death. We hypothesized that the N protein truncation may be inducing apoptosis, or alternatively, had lost its ability to down-regulate apoptosis. We recognize that signaling pathways for apoptosis in mammalian cells occurs by utilizing intrinsic (e.g. DNA damage, endoplasmic reticulum stress) or extrinsic factors (e.g. binding of cytokines, hormones or viruses to specific membrane receptors). The extrinsic pathway is activated by a superfamily of known death receptors such as Fas receptor, Fas-R (CD95 or APO-1) or tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) (Strasser, O'Connor, and Dixit, 2000), which are known to facilitate the recruitment of procaspase-8 monomers, leading to the dimerization and activation of initiator caspases, such as caspase-8 (Ashkenazi and Dixit, 1998; Boatright et al., 2003; Donepudi et al., 2003). To address this hypothesis, we initially chose to probe caspase activity with a series of N- and C-terminal HTNV N protein deletion constructs. Most of the events that lead to cell death are executed by a group of proteases that are cysteine-dependent aspartate-directed, which cleave a variety of intracellular polypeptides (Earnshaw, Martins, and Kaufmann, 1999). Caspase activation ultimately leads to cell infrastructure damage and cell death. Depending on their function and point of entry into the apoptotic pathway, caspases are classified as initiators or executioners. Elevated caspase-7 activity was observed in Vero E6 cells expressing a C-terminal fragment. Our studies suggest that the N protein suppresses apoptosis through its interaction with NF-κB.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Vero E6 or HeLa cells were purchased from American Tissue Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and were cultured in advanced modified eagles medium (A-MEM, GIBCO™, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 1% L-glutamine.

Construction of plasmids

The plasmid pcHTNS was generated by ligating the coding region of the S-segment from HTNV 76–118 into pcDNA4/TO (Invitrogen™, Carlsbad, CA). The coding region was PCR-amplified from the vector pGEM1-HTNVS (gift of Connie Schmaljohn, Virology Division, USAMRIID, GenBank #M14626) with oligonucleotides synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT, Coralville, Iowa). The forward primer (5'-GCGGAATTCACTATG…3') incorporated an EcoRI site (shown in italics), while the reverse primer (5'-GCGCTCGAGTTAGAGTTTCAAAGGCTCTTGG-3') incorporated an XhoI site (shown in italics). The coding region of the GFP was PCR-amplified with oligonucleotides synthesized by IDT and fused to the EcoRI site located in N-terminus of the HTNV N protein.

To generate various deletions of the N protein, primers were designed to amplify the entire pcHTNS with HiFi Taq DNA polymerase yet delete the region of interest in the HTNV S-segment. N-terminal deletion mutants generated by this approach included NΔ270, NΔ300, NΔ330, and NΔ360, which had N-terminal deletions of 270, 300, 330 and 360 amino acids respectively. Deletions were created in the N-terminus using a universal reverse primer (5'-AAGGAAAAAAGCGGCCGCAGAATTCGAGAGT GATCCCGG-3') and different forward primers that incorporated a NotI site (shown in italics) to facilitate recircularization and the removal of the sequences in the 5' end of the S-segment ORF. The PCR products were recircularized with Quick Ligase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) and transformed into JM109 E. coli competent cells (Promega, Madison, WI). The forward primers used were; NΔ270 (5'-AAGGAAAAAAGCGGCCGCACGATGGTGGCATTAGGCAATATGAG-3'), NΔ300 (5'-AAGGAAAAAAGCGGCCGCAGCATGTCACCATCATCAATATGGG-3'), NΔ330 (5'-AAGGAAAAAAGCGGCCGCACGATGTTTTTTTCCATCCTGCAGGAC-3'), and NΔ360 (5'-AAGGAAAAAAGCGGCCGCACGATGTTTTATCAGTCCTACCTCAGAAG-3').

C-terminal deletions that were constructed in the HTNV N protein included CΔ99, CΔ129, CΔ159, and CΔ189, which represented deletions of 99, 129, 159, and 189 amino acids from the C-terminus, respectively. Deletions were created in the C-terminus using a universal forward primer (5'-AAGGAAAAAAGCGGCCGCACTCGAGTCTAGAGGGCCCG-3'). The reverse primers used were as follows: CΔ99 (5'-AAGGAAAAAAGCGGCCGCTTATGCCCCAAGCTCAGCAATAC-3'), CΔ129 (5'-AAGGAAAAAAGCGGCCGCTTACTCAATATCTTCAATCATGCTAC-3'), CΔ159 (5'-AAGGAAAAAAGCGGCCGCTTATTGCCGCTGCCGTAAGTAG-3'), and CΔ189 (5'-AAGGAAAAAAGCGGCCGCTTATAACCATTGTTCGATACGATCAC-3').

The 271–300 construct with N- and C-terminal deletions was made with NΔ270 plasmid as the target DNA. The gene was amplified with the universal forward primer and the CΔ129 reverse primer. The Myc-tagged HTNV N protein was constructed by PCR amplification of the pcHTNS plasmid using a specific forward primer (5'-GATGGAACAAAAACTCATCTCAGAAAGAGGATCTGATGGCACTATGGAGGAATTACAGAG-3'), that contained the Myc sequence (EQKLISEEDLN) and the reverse primer (5'-CCGGAATTCGGATCCAGCTTAAGTTTAAACGCTAGCCAGCTTGGGTCT-3').

To obtain the ORF from ANDV S-segment, total ANDV RNA was reverse transcribed and amplified using Enhanced Avian RT-PCR kit (Sigma®, St. Louis, MO). The gene specific forward and reverse primers were designed based on Genbank #AF291702.1 sequence with BamHI and XhoI restriction sites (sense, 5′- GCGCGCGGATCCGGGATGGGCACCCTCCAAG-3′, antisense, 5′- GCGCGCCTCGAGTTACAACTTGAGTGGCTC-3′). The PCR products were gel purified using QIAquick Spin Gel Extraction kit (Qiagen, MD), digested with BamHI and XhoI and ligated into pcDNA4/TO (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). To generate the ANDV NA360, the region of interest was PCR amplified with the forward (5′–CGGAATTCACCATGTACCAATCATACCTAAGAAGGAC-3′) and reverse (5′–CGCTCGAGCTACAACTTAAGTGGCTCTTGG-3′) primers with 5′ EcoRI and 3′ XhoI restriction sites, then cloned into pcDNA4/TO. The nucleotide sequences of each construct were confirmed by bidirectional sequencing using the pcDNA4/TO CMV forward (5'-CGCAAATGGGCGGTAGGCGTG-3') and BGH reverse (5′-TAGAAGGCACAGTCGAGG-3′) sites using an ABI automated sequencer.

Transfections

Vero E6 or HeLa cells were seeded in 6-well plates (Nalge Nunc International, Naperville, IL) and transfected with 5 µg of plasmid DNA at 60% confluence using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen™, Carlsbad, CA) or TransIT-LT1 (Mirus, Houston, TX), respectively. For Vero E6 cells, complete A-MEM was added to the wells after 1 h of incubation with DNA and incubated in a CO2 incubator at 37 °C for an additional 23 h. At 24 h post-transfection cells were lysed and harvested.

For IFA analysis, HeLa cells were seeded in Lab-Tek II 4-well slides (Nalge Nunc International, Naperville, IL) and transfected with 0.8 µg of plasmid DNA at 60% confluence using Lipofectamine 2000 or TransIT-LT1, respectively. For Vero E6 cells, complete A-MEM was added to the wells after 1 h of incubation with DNA and incubated in a CO2 incubator at 37°C for an additional 23 h. At 24 h post-transfection, slides were fixed and mounted.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Slides were washed three times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, and permeabilized with cold methanol for 15 min at −20 °C. Slides were blocked with blocking buffer (PBS pH 7.4, 3% BSA, 0.3% Triton-X100) for 30 min. The HTNV N protein and mutants were detected by expression of GFP. NF-κB, FADD, cleaved PARP, caspase-7 and -8, were detected with polyclonal antibodies (Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA) by overnight incubation at 4 °C. Antibodies were diluted in antibody dilution buffer (PBS pH 7.4, 1% BSA, 0.3% Triton-X100) at a dilution of 1:100, 1:150, 1:200, 1:100, and 1:100 for NF-κB, FADD, cleaved PARP, caspase-7 and -8, respectively. Slides were washed three times with PBS and incubated at RT with anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to Alexa 594 (Invitrogen™, Carlsbad, CA) for 30 min with a dilution of 1:450. To visualize the nucleus, the slides were washed three times with PBS and stained with Hoechst DAPI (Invitrogen™, Carlsbad, CA) for 5 min at a dilution of 1:5,000. Slides were mounted with Fluoromount-G (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL) and analyzed using Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope and AxioVison 4.5 system software (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) or by confocal imaging analysis. Confocal microscopy was performed with a Leica DMIRBE inverted epifluorescence microscope outfitted with Leica TCS NT SP1 laser confocal optics at the High Resolution Imaging Facility at the University of Alabama – Birmingham.

Caspase-3/7 Glo activity assay

The activity of caspase-3/7 was measured using the Caspase-Glo 3/7 Assay (Promega, Madison, WI). Vero E6 cells were transfected at 80% confluence with 0.8 µg of plasmid DNA in 24-well plates and grown for 24 h. Samples were read 30 min after exposure to substrate using an Envison 2101 microplate reader (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) at an excitation at 360 nm and emission of 465 nm.

Caspase-3/7, 8, and 9 activity assay

Vero E6 or HeLa cells were transfected with 5 µg of plasmid DNA in 6-well plates. Cells were harvested by trypsin and centrifuged in a 15 ml centrifuge tube (per well) at 150 × g using a Sorvall H1000B rotor for 5 min. The supernatant was removed and the cells were washed in 1 ml of ice cold PBS. The cells were centrifuged and washed two more times. The cells were resuspended in 115 µl per well with 0.2 µm filter sterile caspase extract buffer (10mM HEPES pH 7.5, 2mM EDTA, 0.1% CHAPS, 10mM DTT). Cells extracts were prepared as previously described (Li et al., 2007) with some minor modifications with 50 µM of the caspase substrate. Caspase-3/7, -8, and -9 substrates (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) were fluorogenic tetrapeptides; Ac-DEVD-AMC [acetyl-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-7-(amido-4-methylcoumarin)], Ac-IETD-AMC [acetyl-Ile-Glu-Thr-Asp-7-(amido-4-methylcoumarin)], and Ac-LEHD [acetyl- Leu-Glu-His-Asp-7-(amido-4-trifluoromethylcoumarin)]. Cleavage was followed fluorometrically, with excitation at 360 nm and emission at 465 nm. Reactions were read 45 min after incubation with substrate using the Envison 2101 microplate reader to detect activity as indicated by release of free amino-methyl-coumarin.

Western blot analyses

For western blot analyses, HeLa cells were transfected with 5 µg of plasmid DNA in 6-well plates. Cells were harvested with trypsin and were pelleted in a 15 ml centrifuge tube (per well) using a Sorvall H1000B rotor for 5 min. The supernatant was removed and the cells were washed in 1 ml of ice cold PBS. The cells were re-pelleted and washed two more times. The cells were resuspended in 100 µl per well with 0.2 µm filter sterile extract buffer (10mM HEPES ph 7.5, 0.1% CHAPS, 2mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1% NP40). Cells were mechanically lysed by passing through a 27 gauge needle 15–20 times. The cell lysate was centrifuged at 600 × g for 12 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was analyzed by SD S-PAGE. Proteins were separated on a 4 to 12% gradient SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to nitrocellulose. Blots were blocked with 5% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.5% Tween-20 (TBST) for 1 hr, and probed overnight at 4 °C with antibodies directed against active caspase-3, caspase-7, and caspase-8, TNF-R1, Fas-R, cleaved PARP, NF-κB (Rel-A), p-NF-κB (p-Rel-A), IκB, TRADD, TRAF-2, A20, actin, and histone-3 (Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA) each at a dilution of 1:1000. Blots were washed 3 times with TBST for 5 min and probed with anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 30 min. Blots were developed with SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrates (Pierce, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL).

NF-κB translocation assay

HeLa cells were transfected with 5 µg or 0.8 µg of plasmid DNA in 6-well plates or 4-well slides, respectively, and were incubated in a CO2 incubator at 37°C for 24 hrs. After incubation, cells were mock-treated or treated with 20 ng/ml of TNF-α for 20 min. For the cells in 6-well plates, the cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts were isolated using ProteoExtract™ Subcellular Proteome Extraction Kit (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA). Extracts were analyzed by western blot analysis. For the cells in 4-well slides, slides were prepared and probed for NF-κB as described above then analyzed by confocal microscopy.

Coimmunoprecipitation assays

HeLa cells were transfected with 75 µg of myc-tagged HTNV N protein plasmid DNA in T-150 flask. Cells were harvested by trypsin and pelleted in a 50 ml centrifuge tube at 150 × g using a Sorvall H1000B rotor for 5 min. The supernatant was removed and the cells were washed in 6 ml of ice cold PBS. The cells were re-pelleted and washed two more times. Cells were resuspended in 300 µl of immunoprecipitation buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM Na2EDTA, 1mM EGTA, 1% Triton, 2.5 mM Sodium Pyrophosphate, 1 mM beta-glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 µg/ml Leupeptin). Cells were mechanically lysed by passing through a 27 gauge needle 15–20 times. Extracts were centrifuged at 600 × g for 12 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was precleared with 25 µl of protein A Dynabeads (Invitrogen™, Carlsbad, CA) for 3 hrs. In another tube, protein A Dynabeads were washed with 200 µl of ice-cold wash and bind buffer (0.1 M NaH2PO4, 0.01% Tween-20). Anti-myc antibody was added to the washed Dynabeads and crosslinked with 5mM BS3 for 30 min at room temperature using rotation. The crosslinking was quenched by adding 1M Tris-HCL (ph7.5) for 15 min at room temperature. The Dynabead-antibody complex was washed five times with wash and bind buffer. After removal of wash and bind buffer from Dynabeads, 300 µl of precleared lysate was added and incubated overnight to 24 h with rotation at 4 °C. The immune complex (Dynabeads-antibody-antigen) was carefully washed three times with 200 µl ice-cold PBS, using a new tube for each wash. On the last wash, the sample was mixed end-over-end using rotation at 4 °C for 30 min. The HTNV N protein was eluted from the immune complex by adding 30 µl of SDS buffer. Samples were heated at 70 °C for 10 min and were analyzed by western blot analysis.

Functional assay for HTNV N anti-apoptotic activity

HeLa cells were transfected with 5 µg or 10 µg of the plasmid pcHTNS in 6-well plates or T-25 flasks, respectively, and were incubated for 24 hrs. Cells from 6-well plates were lysed in 115 µl caspase extract buffer for caspase activity as explained above in the methods section on caspase-3/7, 8, and 9 activity assays. Cells from the T-25 flasks were mock-treated or treated with 20 ng/ml of TNF-α for 20 min. The cytoplasmic fraction was isolated using 1.0 ml of ProteoExtract™ Subcellular Proteome Extraction Kit. Half of the cytoplasmic fraction (500 µl) was concentrated to 15 µl using the ProteoExtract™ Protein Precipitation Kit (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA). Using caspase-3/7 substrate, the caspase activity was measured as described above with some minor modifications. Untreated or STR treated cells served as negative and positive controls, respectively. In one sample, the caspase extract of STR treated cells (6-well plate) was supplemented with 15 µl of 100 µM caspase inhibitor Z-D(OMe)E(OMe)VD(OMe)– FMK [Z-Asp(OMe)-Glu(OMe)-Val-Asp(OMe)-FMK] (Imgenex, San Diego, CA) to determine the effect of inhibitors on caspase extract activity. For three other samples, caspase extracts of STR treated cells from 6-well plates were supplemented with 15 µl of concentrated cytoplasmic extract (T-25 flask) from cells mock-transfected or transfected with HTNV S-segment, and untreated or treated with 20 ng/ml of TNF-α. Caspase activity was measured as explained above by the release of free amino-methyl-coumarin.

Results

Construction, localization and discovery of cell death in HTNV N protein deletion mutants

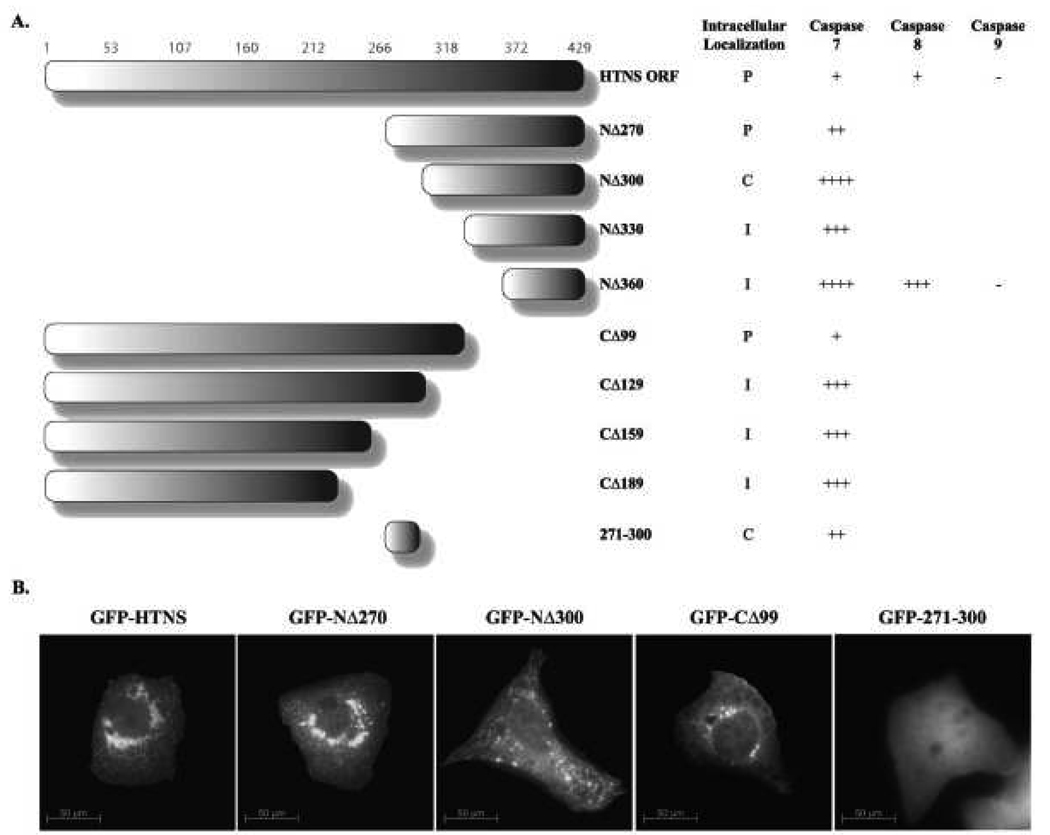

Using amino acid sequence alignments as a guide (Jonsson, 2001; Xu et al., 2002), we cloned a series of plasmid constructs that removed the N- and/or C-terminus of the HTNV N protein (Fig. 1A). N-terminal deletions of the HTNV N protein included NΔ270, NΔ300, NΔ330, and NΔ360, which removed 270, 300, 330 and 360 amino acids from the N-terminus, respectively (Fig. 1). C-terminal deletions of the HTNV N protein included CΔ99, CΔ129, CΔ159, and CΔ189, which removed 99, 129, 159, and 189 amino acids from the C-terminus, respectively (Fig. 1). Deletion construct 271–300 contained both N- and C-terminal deletions, and comprised amino acids 271–300 of the HTNV N protein (Fig. 1). Each construct had an N-terminal GFP tag fusion to facilitate intracellular detection.

FIG. 1.

Illustration of HTNV N protein deletion mutants and summary of their localization and caspase activities. (A) N-terminal deletion mutants of the HTNV N protein included NΔ270, NΔ300, NΔ330, and NΔ360, which were lacking 270, 300, 330 and 360 amino acids from the N-terminus respectively. C-terminally deleted HTNV N protein mutants included CΔ99, CΔ129, CΔ159, and CΔ189, lacking 99, 129, 159, and 189 amino acids from the C-terminus, respectively. Deletion mutant 271–300 contained both N- and C-terminal deletions. Intracellular localization was determined and noted as perinuclear (P), cytoplasmic (C), or indeterminate (I) (see panel B, data not shown for all constructs). We summarize caspase activities for each construct from experiments presented in Figure 3 and Figure 4. Caspase activation was scored with increasing activity correlating with increasing number of plus-signs; ++++ (high) and + (low). Data for these results are shown in subsequent figures. (B) Vero E6 cells were transfected with plasmid DNA expressing the fusion proteins indicated at the top of each panel. After incubation at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 24 h, N protein expression was detected by fluorescence generated by GFP. Slides were acetone fixed and processed, and examined for fluorescence at excitation and emission spectra of 470 and 509 nm, respectively, using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope. Scale bar, 50 µm, with 40X objective at 1.6 optovar/tubelens (Zeiss Axiovert 200).

Plasmids containing full-length or truncated N open reading frames were transfected into Vero E6 cells. Cells expressing the full length N protein (GFP-HTNS) showed punctated perinuclear localization (Fig. 1B), which is characteristic of cells infected with hantaviruses (Hung et al., 1992; Mir et al., 2008; Ramanathan et al., 2007). GFP-NΔ270, which has nearly two-thirds of the N protein removed from the N-terminus, retained perinuclear localization (Fig. 1B). We also observed that Vero E6 cells expressing GFP-CΔ99, which lacked 99 amino acids of the C-terminus, resulted in a perinuclear localization pattern similar to wild type N protein (Fig. 1B). Perinuclear localization was abrogated when 300 amino acids were removed from the N-terminus (Fig. 1B, GFP-NΔ300) or 129 amino acids from the C-terminus (Fig. 1B GFP-CΔ129). This suggested that the region between 271 and 300 may contain a signal for targeting of N protein to the perinuclear region. Surprisingly, however, when the region from 271–300 was expressed, it was uniformly found throughout the cell (Fig. 1B). These data suggest that the region between 270 and 300 is necessary, but not sufficient for perinuclear localization.

Intriguingly, conclusive localization of N protein was difficult in certain experiments with certain constructs. We noted these as indeterminate (I) because visual examination of cells expressing these proteins revealed cell death. This was noted in cells transfected with N protein mutants lacking more than 300 amino acids from the N-terminus or 99 amino acids from the C-terminus (Fig. 1, data not shown). We focused our efforts to probe the nature of these unexpected findings.

Deletion of amino acids 270 to 330 in the HTNV N protein triggers caspase-7 in HeLa cells

We hypothesized that the cell death noted in Vero E6 cells expressing certain N protein truncations were undergoing apoptosis. To address this, we performed a caspase-like activity assay as an intracellular marker of apoptosis following the expression of the various plasmids for 24 h post-transfection. The activity of caspase-3/7 was measured using a caspase substrate (DEVD), which cannot discriminate between caspase-3 and -7.

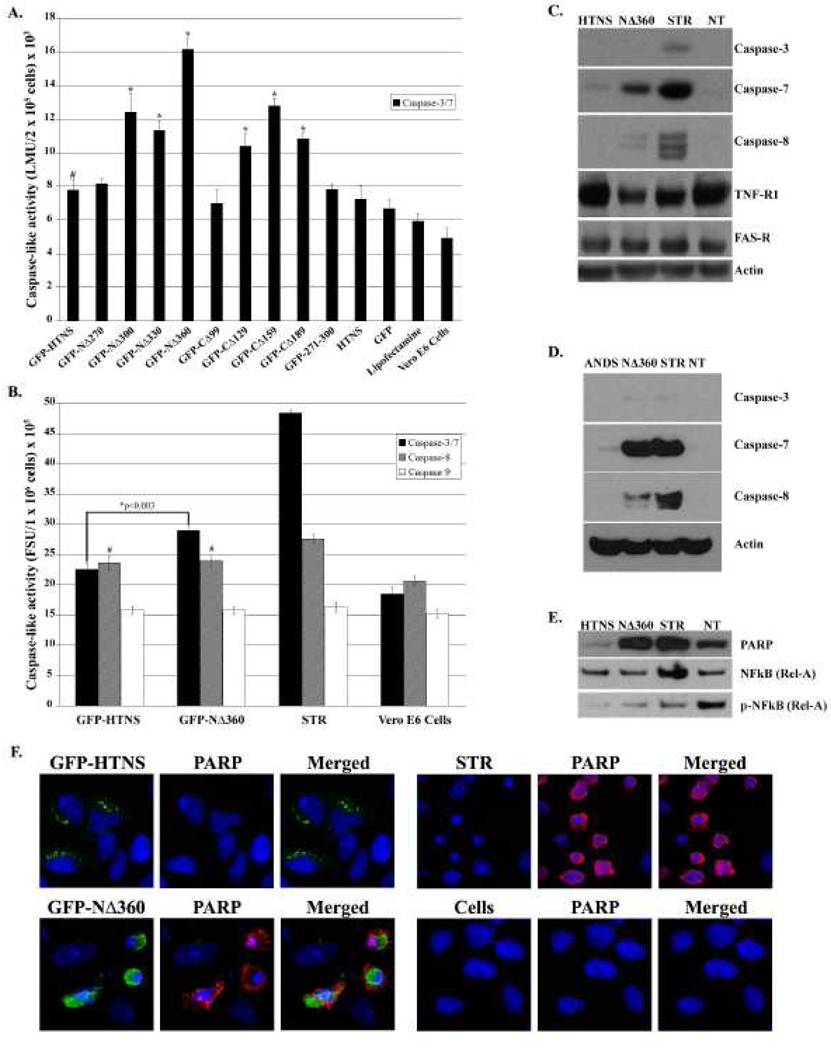

Substantial levels of caspase-3/7 activity were observed with specific N- or C-terminal deletion mutants in Vero E6 cells (Fig. 2A). N-terminal deletions of the N protein elicited a slightly higher caspase-3/7 response than the C-terminal deletions (Fig. 2A). The greatest caspase-3/7 activity was noted in cells expressing GFP-NΔ360, GFP-NΔ300, GFP-CΔ159 and GFP-CΔ189, which were significantly higher than cells expressing GFP-HTNS (Fig. 2A). In comparison, GFP-CΔ99, which comprises amino acids 1–330, and GFP-NΔ270, which comprises amino acids 271–429, showed statistically similar levels (p>0.05) to the full-length N protein (Fig. 2A). The finding that cells expressing GFP-NΔ270 and GFP-CΔ99 have diminished caspase-3/7 activity, while cells expressing GFP-NΔ360 and GFP-CΔ159 had significantly higher caspase-3/7 activity suggested that removal of amino acids 270–330 of the HTNV N protein enhanced the activation of caspase-3/7 (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, although slightly elevated, we observed a significantly higher level (p<0.003) of caspase-3/7 activity in cells expressing GFP-HTNS versus cells treated with lipofectamine alone (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

Deletion of amino acids 270 to 330 results in the activation of caspase-7 and -8, but not of caspase-9 in HeLa cells. (A) Quantification of caspase-3/7-like activity, expressed as luminescence unit (LMU) in 2 × 105 cells, using Caspase-Glo® 3/7 Assay in Vero E6 cells after transfection with 0.8 µg plasmid DNA at 24 h in 24 well plates. *p < 0.002 versus cells expressing GFP-HTNS. #p < 0.003 versus Lipofectamine treated cells. (B) Caspase-3/7, -8, and -9-like activity in Vero E6 cells after transfection with 5 µg plasmid DNA at 24 h in 6 well plates as measured by Ac-DEVD-AMC, Ac-IETD-AMC, or Ac-LEHD-AMC cleavage, respectively, expressed as the fluorescence unit (FSU) in 1 × 106 cells, after transfection with plasmid DNA for 24 h. *p < 0.003 versus cells expressing GFP-HTNS. #p < 0.04 versus mock cells. For A and B, each value is the mean of three different samples, and the vertical bars represent the standard deviation. (C) Examination of caspase-3, -7, and -8, TNRF-1, and Fas-R levels in HTNV N protein or NΔ360 expressing cells. (D) Examination of caspase-3, -7, and -8 levels in ANDV N protein or NΔ360 expressing cells. (E) Examination of cleaved PARP, NF-κB (Rel-A), and p-NF-κB (p-Rel-A) in HTNV N protein or NΔ360 expressing cells. For western blots, HeLa cells were transfected with 5 µg plasmid DNA expressing HTNV or ANDV N protein, HTNV or ANDV NΔ360, or mock, or treated with 1 µM staurosporine (STR). Proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes and probed with antibodies against caspase-3, -7, and -8, cleaved PARP, NF-κB (Rel-A), p-NF-κB (p-Rel-A), or actin (loading control). (F) HeLa cells were transfected with 0.8 µg of plasmid DNA expressing HTNV N protein, NΔ360, or mock, or treated with 1 µM STR for 3 h. Slides were examined by indirect immunofluorescence for N protein or NΔ360 (Green) as GFP expression, or cleaved PARP (Red) with polyclonal antibodies as described in materials and methods with 63× objectives using a Leica confocal microscope.

GFP-NΔ360 increases caspase-3/7 and -8 activity but not caspase-9

Initiator caspases, such as caspase-8 or -10, are directly capable of activating executioner caspases, such as caspase-3 or -7 with sufficient magnitude to indicate direct processing of apoptosis in vivo (Stennicke et al., 1998). Caspases-3 and -7 exist in the cytosol as inactive dimers or pro-caspases and function to initiate the characteristics of apoptosis (Boatright and Salvesen, 2003; Stennicke et al., 1998). To further explore the possible apoptotic pathways elicited, we analyzed the activation of caspase-8 and -9. For these studies, we compared GFP-NΔ360 against the full-length GFP-HTNS since GFP-NΔ360 showed the greatest activation of caspase-3/7.

As predicted from our observations (Fig. 2A), GFP-NΔ360 induced a significantly higher (p<0.003) caspase-3/7 activity than cells expressing GFP-HTNS (Fig. 2B). Although caspase-8 activity was significantly elevated (p<0.03) in cells expressing GFP-HTNS and GFP-NΔ360 compared to cell control, there was no significant difference between the caspase-8 activity induced by GFP-HTNS or GFP-NΔ360 (Fig. 2B, p>0.05). We noted no significant difference in caspase-9 activity among any of the groups (Fig. 2B). Staurosporine (STR), a known activator of caspases, was employed as a positive control (Fig. 2B) (Zhang, Gillespie, and Hersey, 2004). Since caspase-8 is a known activator of effector caspases (Stennicke et al., 1998), these data suggested that activation of caspase-3/7 is mediated by either the Fas-R or TNFR-1 pathways through the activation of caspase-8.

NΔ360 elicits a caspase-7 and -8 response, while HTNV N protein plays apoptotic inhibitory roles in HeLa cells

Since our previous assays were unable to discriminate between caspase-3 and -7, we performed western blots of cell extracts to probe for the presence of active caspase-3, -7 and -8 in HeLa cells (Fig. 2C). We employed HeLa cells for these studies given the lack of antibody reagents available for Vero E6 cells. HeLa cells were transfected with plasmids expressing full-length HTNV N protein, NΔ360, or mock (Fig. 2C). Cells treated with 1 µM STR served as a positive control (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, caspase-3 was not detected in cells expressing N protein or NΔ360 (Fig. 2C). A low level of caspase-3 activity was observed in STR treated cells (Fig. 2C). In contrast, significant levels of caspase-7 were observed in cells transfected with NA360 (Fig. 2C). Minor amounts of caspase-7 activity were observed in cells expressing full-length N protein (Fig. 2C). This experiment suggested that the cell death we observed visually (data not shown) and the caspase activity (Fig. 2A and B) were predominantly through the effects of caspase-7.

Since both the Fas-R and TNFR-1 pathways activate initiator caspases, we asked which pathway was affected. We assayed for Fas-R and TNFR-1 protein levels in cells expressing N protein or NΔ360. We observed no difference in the relative amounts of Fas-R in cells expressing N protein, NΔ360, STR, or mock (Fig. 2C), which suggested no involvement of Fas-R. In contrast, reduced levels of TNFR-1 were observed in NΔ360 and STR treated cells (Fig. 2C). This was a surprising finding, because we expected higher expression levels of TNF-R1 in cells expressing NΔ360, because we expected the cell death observed to be mediated through this receptor since there was no increase in Fas-R in cells expressing NΔ360. Although TNFR-1 signaling plays a role in the activation of caspases, it has additional functions, including the activation of NF-κB.

To validate our findings, we chose a second hantavirus to examine caspase induction with western blot analyses. We generated an identical construct for ANDV based on the HTNV N protein mutant NΔ360. HeLa cells were transfected with plasmids expressing full-length ANDV N protein, NΔ360, or mock (Fig. 2D). STR-treated cells served as a positive control (Fig 2D). Similar to HTNV, the ANDV N protein did not activate a caspase-3 response in HeLa cells expressing full-length ANDV N protein or NΔ360 (Fig. 2D). A significant amount of caspase-7 was observed in cells transfected with NΔ360 as compared to full-length ANDV N protein (Fig. 2D). The levels of caspase-7 in cells expressing NΔ360 were comparable to the levels of STR-treated cells (Fig. 2D). Similar to the previous results for HTNV (Fig. 2C), we observed only a minor amount of caspase-8 in cells expressing ANDV NΔ360 mutant and none in cells expressing full-length ANDV N protein (Fig. 2D). These data suggest that the functionality of the N protein in terms of apoptosis does not differ significantly between Old and New World hantaviruses.

To further substantiate that cell death was occurring in cells expressing HTNV NΔ360, we probed for nuclear enzyme poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) cleavage using western blot using antibodies against cleaved PARP (Fig. 2E) and by IFA (Fig 2F). Caspases-3 and -7 are capable of cleaving at specific tetrapeptide substrates, such as PARP, that contain amino acids DEVD. Although PARP enzyme plays important roles in genomic stability and DNA repair (Ding et al., 1992; Ding and Smulson, 1994), PARP cleavage is a major hallmark of apoptosis (Boulares et al., 1999). HeLa cells were transfected with plasmids expressing GFP-tagged HTNV N protein (GFP-HTNS), GFP-NΔ360, or treated with STR (Fig. 2E). As expected, 3 hrs after STR treatment, cells showed significant signs of PARP cleavage (Fig. 2F). This was further validated by western blots that showed significant levels of cleaved PARP (Fig. 2E). Cells expressing GFP-NΔ360 also showed PARP cleavage (Fig. 2F) and were similar to STR-treated cells when measured by western blot (Fig. 2E). Importantly, cells expressing HTNV N protein had significantly lower levels of cleaved PARP when measured by western blot as compared to untreated cells (Fig. 2E). A small amount of naturally occurring PARP cleavage was observable by IFA and by western blot in cells expressing HTNV N protein or mock cells. In summary, these data suggest that apoptosis occurring in cells expressing GFP-NΔ360 was initiated through caspase-8, which further activates caspase-7, resulting in the cleavage of PARP, and thus apoptosis. An interesting observation is that although there was a slight activation of caspase-7 in cells expressing HTNV N protein (Fig. 2C), there were lower levels of cleaved PARP present as compared to mock cells (Fig. 2E). This suggested that the full-length HTNV N protein may play a role in inhibiting caspase activation in HeLa cells.

Since we observed no involvement of the Fas-R pathway, we wanted to determine if there were possible downstream mediators of the TNF-R1 pathway that may be affected by NΔ360 such as NF-κB. There were no differences in cellular levels of NF-κB in cells expressing HTNV N protein, NΔ360, and mock treated cells (Fig. 2E). However, we noted a significant reduction in levels of phosphorylated NF-κB (p-NF-κB) in cells expressing HTNV N protein as compared to mock cells (Fig. 2E). Since p-NF-κB is predominantly found in the nucleus, this suggested the HTNV N protein may inhibit or delay the nuclear import of NF-κB. The HTNV N protein has been shown to interact with nuclear import proteins, which can inhibit translocation of NF-κB into the nucleus (Taylor et al., 2009). Overall, these data suggested that the full-length HTNV N protein may modulate apoptosis and immune response through the inhibition of nuclear import of NF-κB, respectively.

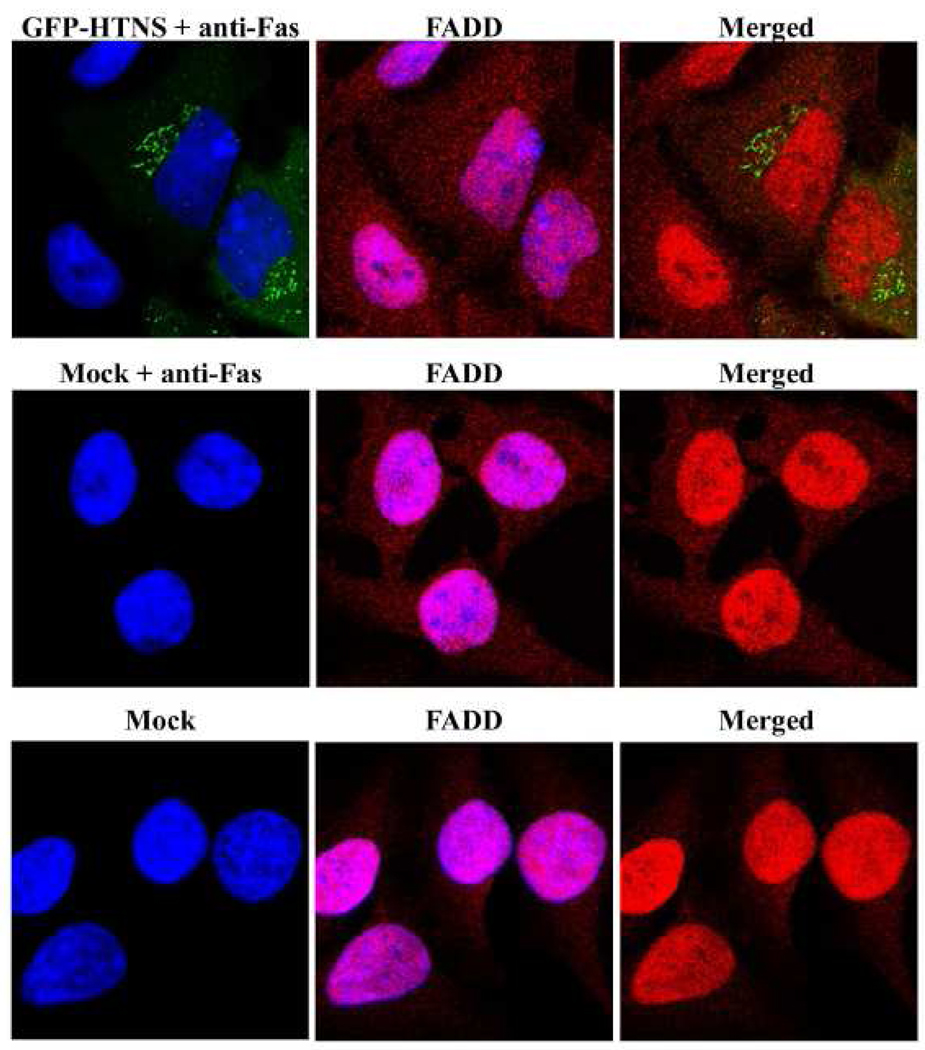

HTNV N protein does not affect downstream mediators of Fas-R signaling

Although we showed no difference in the levels of Fas-R in cells expressing HTNV N protein versus mock cells (Fig. 2C), this did not rule out downstream mediators. Since PUUV N interacts with Daxx, a Fas-associated protein (Li et al., 2002), we focused our efforts on the Fas-R pathway. Using confocal microscopy, we probed for the levels of Fas-associated protein with death domain (FADD), which is an adapter molecule that is the basic bridge or mediator between the Fas-R and caspase-8.

HeLa cells were transfected with the HTNS in the absence or presence of anti-Fas antibodies. FADD was detected with rabbit polyclonal antibody followed by a secondary alexa-594 antibody. FADD was found predominantly in the nucleus in cells that were mock-treated (Fig. 3). To explore this pathway, we used anti-Fas antibodies to induce Fas-R mediated cell death. We observed a larger amount of cytoplasmic FADD following Fas-R stimulation in cells that were mock-transfected or expressing HTNV N protein as compared to unstimulated mock cells (Fig. 3). Since FADD levels were significant in the cytoplasm in the presence of HTNV N protein as compared to mock-treated control cells, this suggested that the N protein does not play an inhibitory role within this pathway. This finding was further validated in experiments in which cells expressing HTNV N protein underwent apoptosis after treatment with anti-Fas antibodies (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Fas-R pathway is not affected by HTNV N protein. HeLa cells were transfected with 0.8 µg of plasmid DNA expressing HTNV N protein, NΔ360, or mock, or treated with 1 µM STR for 3 h. Slides were examined by indirect immunofluorescence for N protein or NΔ360 (Green) as GFP expression, or FADD (Red) with polyclonal antibodies as described in materials and methods with 63× objectives using a Leica confocal microscope

HTNV N protein delays nuclear translocation of NF-κB and promotes the degradation of IκB

We next focused our efforts on the TNF-R1 receptor pathway, since we observed no interaction between Fas-R signaling cascade and inhibition by HTNV N protein. The TNFR-1 pathway is capable of activating downstream mediators such as NF-κB (Kelliher et al., 1998; Lee et al., 2003b; Micheau and Tschopp, 2003), which plays crucial roles in facilitating immune and inflammatory responses through gene regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines within innate and adaptive immunity (Franzoso et al., 1998).

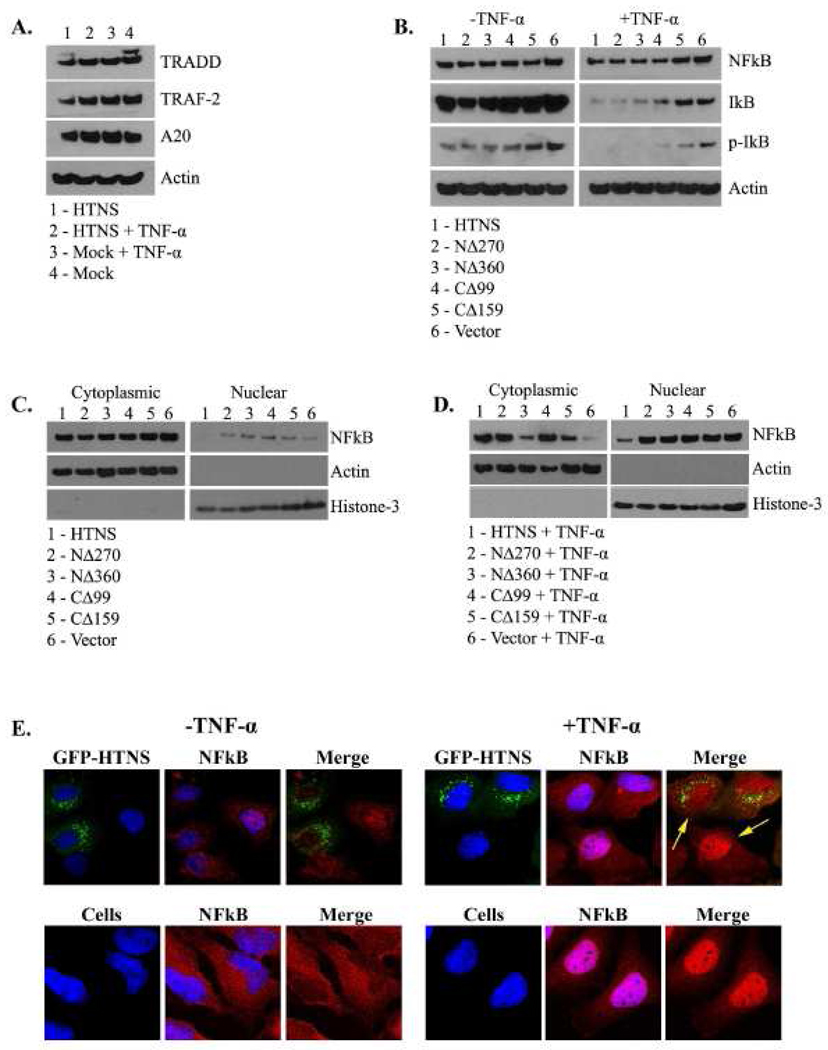

HeLa cells were transfected with HTNS or mock-transfected, and treated with or without TNF-α. Whole cell extracts were made and levels of TNFR-associated via death domain (TRADD), TNFR-associated factor (TRAF)-2, and protein A20 were probed by western blot. We observed no difference in the relative amounts of TRADD or TRAF-2 among cells treated with TNF-α or mock, but did see a minor decrease in cells expressing HTNV N protein alone (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

HTNV N protein affects the TNFR-1 signaling pathway, promotes the degradation of IκB, and inhibits nuclear translocation of NF-κB. Cell lysates were made of HeLa cells and the levels of various cellular proteins were measured. Cells were transfected with 5 µg plasmid DNA expressing HTNV N protein, or mock, untreated or treated with 20 ng/ml of TNF-α for 20 min (A), HTNV N protein, NΔ270, NΔ360, CΔ99, CΔ159, or vector untreated or treated with 20 ng/ml of TNF-α for 20 min (B). Cell lysates were separated into cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of cells treated (C) or untreated with 20 ng/ml of TNF-α for 20 min (D). Proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes and probed with antibodies against TRADD, TRAF-2, protein A20, or actin (A), NF-κB (Rel-A), p-NF-κB (p-Rel-A), IκB, p-κB or actin (B), NF-κB (Rel-A), actin, or histone-3 (C and D). Actin and histone-3 served as loading controls for cytoplasmic or nuclear fractions, respectively. (E) HeLa cells were transfected with 0.8 µg of plasmid DNA expressing GFP-HTNV N protein, or mock for 24 hrs. Cells were then untreated or treated with 20 ng/ml TNF- α for 20 min. Slides were examined by indirect immunofluorescence for N protein (Green) as GFP expression, or NF-κB (Red) with polyclonal antibodies as described in materials and methods with 63X objectives using a Leica confocal microscope.

Protein A20 (TNFAIP3) plays a role in the inhibition of both NF-κB activity and TNF-mediated cell death (Beyaert, Heyninck, and Van Huffel, 2000; Lee et al., 2000). We asked whether elevated levels of protein A20 could be involved in the caspase inhibitory roles that we observed in cells expressing HTNV N protein as reduced levels of cleaved PARP. We observed similar levels of protein A20 in cells expressing HTNV N protein as compared to vector cells in the presence or absence of TNF-α (Fig. 4A). This suggests that the HTNV N protein does not function through protein A20 to block caspase activity, and reduce levels of cleaved PARP (Fig. 2C).

The ability of the HTNV N protein to act on upstream mediators of the TNFR-1 pathway suggested downstream effects. We asked whether the HTNV N protein or mutants were capable of acting on IκB or NF-κB, since we observed an overall decrease in nuclear p-NF-κB in cells expressing full-length HTNV N protein (Fig. 2E) and a decrease in TRADD and TRAF-2 (Fig. 4A). To explore further, we expressed HTNV N protein, NΔ270, NΔ360, CΔ99, CΔ159, or empty vector and co-treated with or without TNF-α (Fig. 4B). Irrespective of whether the cells were expressing full-length HTNV N protein or truncated N proteins, or whether they were treated with or without TNF-α, there were no differences in the levels of cellular NF-κB expression (Fig. 4B). In contrast, we noticed a dramatic decrease in the amount of IκB in cells that were treated with TNF-α as compared to untreated cells (Fig. 4B). Although the levels of IκB in cells expressing NΔ360 or CΔ99 were significantly lower than cells with vector alone, we noted that after treatment with TNF-α the decrease was more profound in cells expressing HTNV N protein or NΔ270 (Fig. 4B). Similar findings were observed in the levels of p-IκB (Fig. 4B). Although we observed reduced levels of TRADD and TRAF-2 in cells expressing HTNV N protein (Fig. 4A), this reduction was not enough to protect IκB from degradation (Fig. 4B). This data suggests that the HTNV N protein facilitates the degradation of IκB, and that it might be directed by a central region within the HTNV N protein since both NΔ270 and CΔ99 were capable of promoting degradation. This region could be within amino acids 270–330, which also falls within the possible localization signal. Although we did observe a decrease in the total levels of IκB in cells that were expressing NΔ360, our data suggest that the decrease we observed could be due to apoptosis rather than IκB inhibition.

Degradation of IκB leads to an assumption that the HTNV N protein could promote the liberation and nuclear import of NF-κB, but our earlier findings would suggest otherwise (Fig. 2E). To probe further, HeLa cells were transfected with full-length HTNS, NΔ270, NΔ360, CΔ99, CΔ159, or empty vector, and treated in the absence (Fig. 4C) or presence (Fig. 4D) of TNF-α followed by separation of the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions. Specifically, we asked whether the reduction in p-NF-κB (Fig. 2E) was due to decreased nuclear import of NF-κB. We observed no difference in NF-κB levels in the cytoplasm in cells expressing the HTNV N protein or mutants (Fig. 4C). This was an expected result, because in whole cell extracts we observed no difference in the levels of NF-κB in unstimulated cells (Fig. 4B). In contrast, we observed a dramatic decrease in the levels of NF-κB in the nucleus in cells that were expressing full-length N protein versus cells expressing mutants or vector alone (Fig. 4C). No difference in nuclear NF-κB was observed between mutants and vector (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, a different cytoplasmic profile of NF-κB was observed in TNF-α treated cells (Fig. 4D). A small amount of NF-κB was present in the cytoplasm in cells transfected with vector alone, however, most was found in the nucleus (Fig. 4D). In contrast, the majority of NF-κB remained in the cytoplasm in cells expressing full-length HTNV N protein (Fig. 4D). There were similar levels of cytoplasmic NF-κB in cells expressing NΔ270 and CΔ99, but high levels of NF-κB were detected in the nucleus (Fig. 4D). Interestingly in cells expressing NΔ360, NF-κB was predominantly detected in the nucleus (Fig. 4D). These data imply that the HTNV N protein effectively inhibited the nuclear import of NF-κB, while NΔ360 lost this function. Although we did find similar levels of cytoplasmic NF-κB in cells transfected with NΔ270 and CΔ99, as compared to cells expressing full-length N protein, no differences in the amount of nuclear NF-κB were observed with vector alone (Fig. 4D). This suggests that the complete abrogation of NF-κB transport into the nucleus may require full-length, or possibly higher-ordered, multimeric forms of HTNV N protein.

We asked whether the inhibition of NF-κB observed could be visually detected by direct microscopy. Hela cells expressing HTNS or vector, were examined with or without TNF-α, and analyzed by confocal microscopy (Fig. 4E). As expected, similar findings were observed between cells expressing GFP-HTNS and vector with no TNF-α treatment (Fig. 4E). Nuclear import of NF-κB was abrogated in cells expressing HTNV N protein after TNF-α treatment (Fig. 4E). Interestingly, a significant difference was observed in the total amount of nuclear NF-κB (as shown by arrows) between cells that are actively expressing HTNV N protein, versus cells that are not (Fig. 4E). This data demonstrates the inhibition of nuclear import of NF-κB by HTNV N protein.

HTNV N protein binds to NF-κB, facilitating its cytoplasmic retention, indirectly regulating caspases

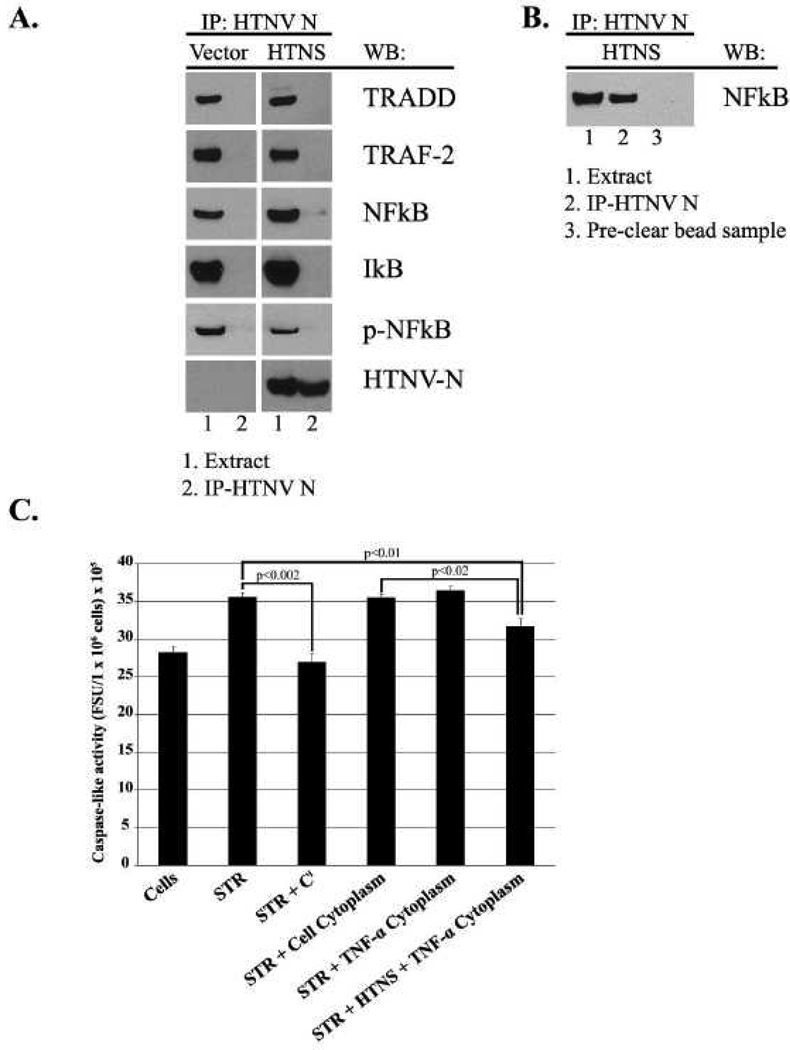

The above data suggested that the HTNV N protein is capable of sequestering NF-κB to the cytoplasm, and is capable of promoting IκB degradation. To examine the possibility that the HTNV N protein directly binds to NF-κB, TRADD or TRAF-2 mediators of the TNFR-1 pathway, we performed co-immunoprecipitation experiments in HeLa cells expressing myc-tagged HTNV N protein. HeLa cells were transfected with myc-tagged HTNS or myc-tag vector and allowed to incubate for 24 hrs. Our results revealed that NF-κB, but not TRADD or TRAF-2 co-immunoprecipitated with HTNV N protein, albeit weakly (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, IκB did not co-immunoprecipitate with HTNV N protein (Fig. 5A). This result was somewhat surprising since our data suggested that the HTNV N protein may facilitate the degradation of IκB. Comparable levels of HTNV N protein were observed between cell extract and immunoprecipitated samples (Fig. 5A). Since we observed a weak interaction between myc-tagged HTNV N protein and NF-κB, we proceeded with a modified protocol with a slightly longer incubation time to optimize immune complex formation (Fig. 5B). This data suggests the N protein is capable of directly interacting with NF-κB, and we hypothesize that this interaction could facilitate liberation and degradation of IκB.

FIG. 5.

Analysis of HTNV N protein interaction with NF-κB, and the examination the cytoplasmic fraction from cells expressing HTNV N protein has on caspase activity. (A) HeLa cells were transfected with 75 µg of plasmid expressing myc-tagged HTNV N protein or empty vector. Immunoprecipitations (IP) were performed with anti-myc antibody bound to magnetic Dynabeads. Immunoprecipitations and whole cell extracts were analyzed by western blot for the levels of HTNV N protein, TRADD, TRAF-2, NF-κB (Rel-A), p-NF-κB (p-Rel-A), or IκB. (B) A modified protocol was used with a longer incubation time of 24 hrs to facilitate immune complex formation. (C) HeLa cells were transfected with 5 µg or 10 µg of plasmid DNA in 6-well plates or T-25 flasks, respectively. Whole cell extracts were made from cells lysed with caspase extract buffer in 6-well plates that were untreated or treated with 5 µM STR and the caspase-3/7 activity was measured. Caspase activity was also measured in the presence of caspase inhibitor (Ci) Z-D(OMe)E(OMe)VD(OMe)–FMK. The cytoplasmic fraction of cells expressing HTNV N protein or mock, untreated or treated with 20 ng/ml of TNF-α for 20 min was extracted and concentrated from cells in T-25 flasks. Caspase activity in cells treated with STR (6-well plates) was measured that were supplemented with 15 µl of cytoplasmic extracts from T-25 flasks. Each value is the mean of three different samples, and the vertical bars represent the standard deviation.

Our analyses showed that HTNV N protein had inhibitory effects on the TNFR-1 pathway, and interacted directly with NF-κB. Based on these observations, we probed how the increased concentrations of cytoplasmic NF-κB effected caspase activity, since NF-κB subunits can serve as a substrate for caspases (Ravi, Bedi, and Fuchs, 1998). HeLa cells were transfected with the HTNS or empty vector and were incubated for 24 hrs. The cells were co-treated with TNF-α or mock-treated for 20 min. The cytoplasmic fractions were harvested and the proteins were concentrated. In a second parallel set of treatments, whole cell extracts were made from cells treated or untreated with STR. The concentrated proteins from the TNF-α or mock-treated lysates were added to the whole cell extracts of STR-treated cells. The activity of caspase-7 was measured using a caspase-3/7 substrate for these various combinations. HeLa cells that were treated with STR had higher caspase-7 activity than that of untreated cells (Fig. 5C). This activity was significantly blocked with the addition of caspase inhibitors (Ci) to the extract (Fig. 5C, STR + Ci, p<0.002). We next wanted to determine if the cytoplasmic fraction of cells expressing HTNV N protein had any effect on caspase-7 activity. The cytosolic extracts of mock-transfected cells or cells not treated with TNF-α had no effect on caspase-7 activity within extracts of STR treated cells (Fig. 5C, STR + Cell Cytoplasm, STR + TNF-α Cytoplasm, p>0.05). Importantly, the extracts of cells that were transfected with HTNS and co-treated with TNF-α caused a significant reduction in caspase-7 activity in the extracts of STR-treated cells (Fig. 5C, STR + HTNS + TNF-α Cytoplasm, p<0.01). A reduction in caspase-7 activity was also observed in cells expressing HTNS and treated with TNF-α when compared to extracts of STR treated cells supplemented with the cytoplasmic extract of mock cells (Fig. 5C, p<0.02). Hence, the retention of cytosolic NF-κB by HTNV N protein correlated with inhibition of caspase-7 activity, and hence, a general reduction of total cleaved PARP in cells expressing N protein versus mock cells (Fig. 2C).

Discussion

Over the past few years, research suggests a multifaceted role for the N protein in trafficking (Ramanathan et al., 2007; Ramanathan and Jonsson, 2008), translation (Mir and Panganiban, 2006) and in modulation of immune signaling (Taylor et al., 2009). Herein, we extend its function to modulation of apoptosis. Taken together, these studies underscore the complexity of the function of the N protein during the life cycle. Several studies suggest that different conformations and specificity of N may modulate the various stages of the life cycle and its interaction with host proteins to achieve these various functions. Structural studies show that the amino-terminal region of N is a dimer (Boudko, Kuhn, and Rossmann, 2007), however, biochemical studies show the N protein can form trimers (Alfadhli et al., 2001; Alfadhli et al., 2002), and in vitro experiments show these trimeric forms preferentially bind the vRNA panhandle (double-stranded vRNA) (Mir and Panganiban, 2004). The binding of the N protein is preferential for the viral RNA, but have the ability to interact with cellular RNA (Severson et al., 1999). Further, the conformation of N protein is altered upon binding (Mir and Panganiban, 2005). Additional interactions with host cellular proteins are apparent in the recent report that suggests modulation of immune signaling by the N protein (Taylor et al., 2009) and the findings of a direct interaction between PUU N protein and Daxx, a Fas-mediated apoptosis enhancer using the yeast two-hybrid approach (Li et al., 2002). Further, the HTNV and SEOV (Lee et al., 2003a; Maeda et al., 2003) and Tula (Kaukinen, Vaheri, and Plyusnin, 2003) N proteins interact with small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO-1) and ubiquitin conjugating enzyme 9 (Ubc9).

Viruses have developed many intriguing strategies and elaborate schemes to evade immune and apoptotic responses. One key player in generating an immune response to a viral infection is NF-κB (Baeuerle and Henkel, 1994; Barnes and Karin, 1997), which is rapidly activated by cytokines, such as TNF-α, through the TNF receptor family (Kelliher et al., 1998; Lee et al., 2003b). Upon its activation, NF-κB translocates to the nucleus utilizing nuclear import molecules, and serves as a transcription factor to trigger both the innate and adaptive immune responses. In normal signaling NF-κB is sequestered in the cytoplasm by IκB by masking a nuclear localization signal that is nested within one of the NF-κB subunits. NF-κB has also been reported as a central player in apoptosis several viruses as discussed in the introduction. As reported by Taylor et al. and in our studies, the HTNV N protein blocks trafficking of NF-κB into the nucleus (Taylor et al., 2009). We also show a direct, albeit weak, interaction between NF-κB and HTNV N protein. Taylor et al. show that the HTNV N protein also manipulates these mechanisms to facilitate its evasion from the hosts cellular and immune responses to enhance propagation (Taylor et al., 2009). We demonstrated that the N protein was capable of promoting the degradation of IκB, which we hypothesize is through the direct inhibition of Ubc9 (Maeda et al., 2003). Our findings support a link between SUMO-1 and Ubc9 interactions and the nuclear import inhibition of NF-κB in HeLa cells. We hypothesize that the retention of NF-κB in the cytoplasm by the N protein facilitates the reduction of caspase activity and apoptosis.

Herein, we addressed the hypothesis that the HTNV N protein can function to regulate apoptosis. Although apoptosis has been observed in HEK293 (embryonic kidney) cells infected with HTNV, SEOV, or ANDV as early as 3–4 days post-infection (Markotic et al., 2003), it was not apparent whether infected cells or bystander cells became apoptotic. Furthermore, no apoptosis or CPE was induced in fully confluent Vero E6 cells inoculated with HTNV, PUUV, Dobrava hantavirus, or Saarema hantavirus up to 12 days post-infection (Hardestam et al., 2005). Interestingly, apoptosis has been observed in lymphocytes (Akhmatova et al., 2003; Wahl-Jensen et al., 2007). Hardestam et al. have effectively argued that hantaviruses are very poor inducers of apoptosis (Hardestam et al., 2005). However, one can also argue conversely that the cell phenotype, and perhaps culture and infection conditions, may influence the ability of various laboratories to observe hantaviral-induced CPE and apoptosis. Indeed, the studies reported to date have focused on the full length N protein and not the truncations we have employed in our studies. Within our studies, we observed significant elevated levels of caspase-7 in cells transfected with certain deletion mutants, such as NΔ360 as compared to cells expressing full-length HTNV N protein. Cells expressing full-length HTNV N protein had slightly elevated caspase-7 and reduced levels of cleaved PARP, which suggests the N protein may suppress caspase activity. Our biochemical analyses support that inhibition of caspase activity by HTNV N protein (Fig. 5B). Finally, we observed nuclear and total cell shrinkage in cells expressing constructs GFP-NΔ360 or GFP-CΔ159, but not in neighboring cells, indicating that there is no bystander effect.

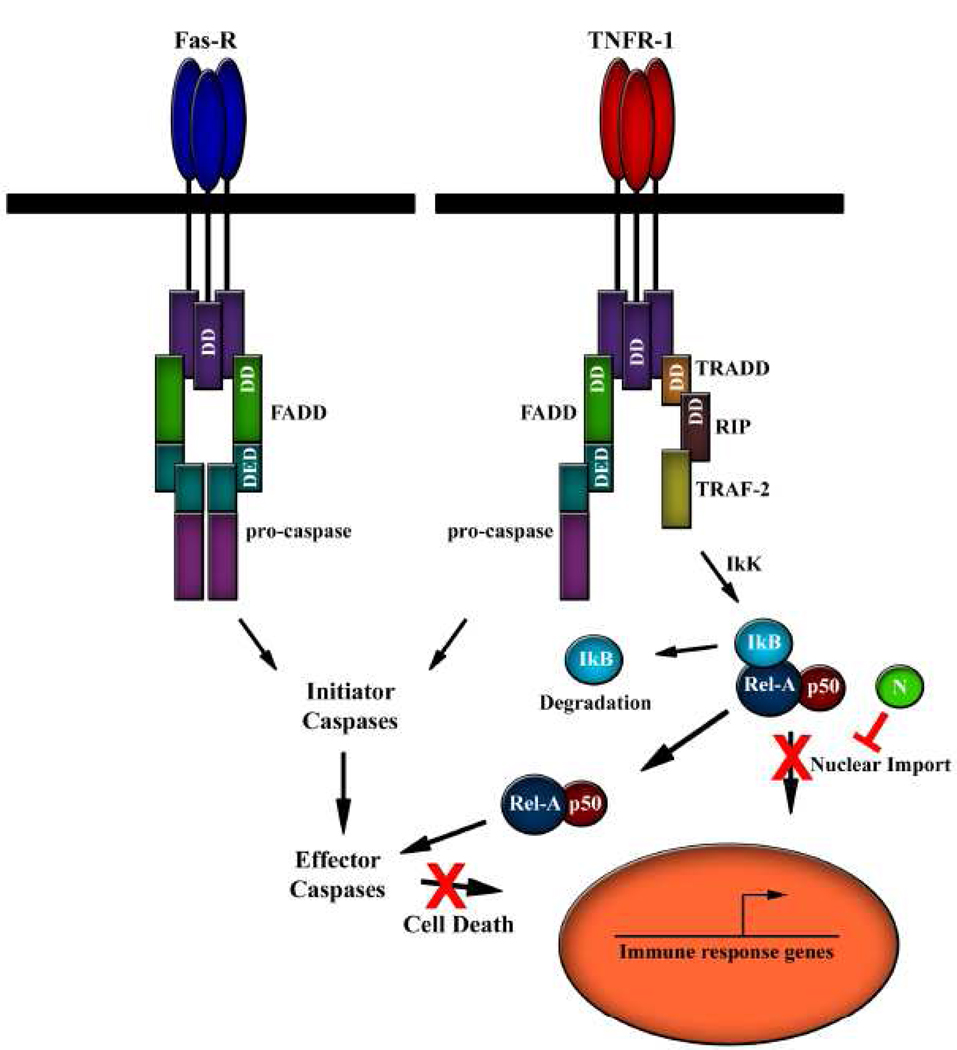

The infection of humans with hantaviruses elicits a strong immune response that has been proposed to be responsible for the observed pathogenesis. Our findings suggest a model in which the HTNV N protein not only sequesters NF-κB to down regulate the immune response (Taylor et al., 2009), but also modulates caspase activity (Fig. 6). As postulated by others, caspases may have a dual role in apoptotic and nonapoptotic functions (Aouad et al., 2004; Kennedy et al., 1999; Lemmers et al., 2007; Los et al., 2001). The interactions of HTNV N protein with NF-κB may liberate NF-κB from IκB or indirectly through Ubc9. Therefore, interactions between HTNV N protein and Ubc9 could help facilitate the degradation of IκB, and thus provide a direct substrate (NF-κB) for caspases (Barkett et al., 2001; Ravi, Bedi, and Fuchs, 1998). Therefore, it seems reasonable to postulate that the virus would also induce the degradation of NF-κB in the cell through the caspase pathway. This response would reduce potential NF-κB and also divert the cell death response. This model is also supported by our observations of a reduction of caspase activity in STR-treated cell extracts that were mixed with the cytoplasmic fraction of cells expressing HTNV N protein and treated with TNF-α. IκB degradation is known to be facilitated by Ubc9, which has been observed to directly interact with HTNV N protein (Maeda et al., 2003). Overexpression of a catalytically inactive Ubc9 delayed both IκB-α degradation and NF-κB activation following TNF-α induction (Tashiro et al., 1997). This latter mechanism may be why we found only a weak interaction of the HTNV N protein with NF-κB. Taylor et al., also did not detect interaction between HTNV N protein and NF-κB (Taylor et al., 2009). Other factors that require examination include caspase-induced truncation of IκBα which can function as a stable inhibitor of NF-κB during apoptosis (Barkett et al., 1997; Reuther and Baldwin, 1999). Caspase-mediated cleavage of IκB occurs immediately 5' of Ser-32 (Barkett et al., 1997). This mechanism is suggested in experiments in which we were unable to detect cellular levels of p-IκB in cells expressing N protein and the possibility of IκB playing partial inhibitory roles of NF-κB. Clearly, more than one mechanism may also be involved to promote virus survival.

FIG. 6.

Model for HTNV N protein in the modulation of immune signaling and inhibition of apoptosis.

The characteristics of hantavirus pathogenesis such as vascular dysfunction and leakage have been characterized primarily in autopsies of human cases (Cosgriff, 1989; Cosgriff and Lewis, 1991; Peters and Khan, 2002; Peters, Simpson, and Levy, 1999), but the underlying mechanisms of HFRS and HPS remain largely uncharacterized. Immunopathogenesis has been regarded as a major contributor of hantavirus pathogenesis. Capillary leakage has been accredited to endothelial cell lysis by armed cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) (Terajima et al., 2007). CTLs isolated from patients infected with SNV recognized a specific epitope of the N protein (Ennis et al., 1997). Furthermore, CTLs increased permeability and caused cell lysis of endothelial cell monolayers infected with SNV (Terajima et al., 2007). Apoptosis of epithelial cells due to the loss of membrane integrity was observed in PUUV-infected patients (Klingstrom et al., 2006). It is therefore tempting to hypothesize that the HTNV N protein plays roles in pathogenesis in the regulation of apoptosis through the interactions with NF-κB. Activation of cellular caspases is evident in cells expressing HTNV N protein, but the N protein clearly functions to circumvent these actions of the host cell. Although our studies clearly show a direct relationship between the HTNV N protein and apoptosis through NF-κB, direct caspase inhibition by HTNV N protein cannot be completely ruled out. The pathways that result in the activation or deactivation of the immune system or caspases are so vast, it is possible that many components within these pathways may contribute. Certainly, defining the functions of the N protein in the context of its structure, conformations and functions during the hantavirus life cycle poses a compelling biological problem that remains to be solved.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by funding support from Southern Research Institute and grants from the National Institutes of Health (5 R21 AI06699-0) and the Department of Defense (W81XWH-04-C-0055) to C.B.J.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akhmatova NK, Yusupova RS, Khaiboullina SF, Sibiryak SV. Lymphocyte Apoptosis during Hemorragic Fever with Renal Syndrome. Russ J Immunol. 2003;8:37–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfadhli A, Love Z, Arvidson B, Seeds J, Willey J, Barklis E. Hantavirus nucleocapsid protein oligomerization. J Virol. 2001;75:2019–2023. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.4.2019-2023.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfadhli A, Steel E, Finlay L, Bachinger HP, Barklis E. Hantavirus nucleocapsid protein coiled-coil domains. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27103–27108. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203395200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aouad SM, Cohen LY, Sharif-Askari E, Haddad EK, Alam A, Sekaly RP. Caspase-3 is a component of Fas death-inducing signaling complex in lipid rafts and its activity is required for complete caspase-8 activation during Fas-mediated cell death. J Immunol. 2004;172:2316–2323. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.4.2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkenazi A, Dixit VM. Death receptors: signaling and modulation. Science. 1998;281:1305–1308. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeuerle PA, Henkel T. Function and activation of NF-kappa B in the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:141–179. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.001041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkett M, Dooher JE, Lemonnier L, Simmons L, Scarpati JN, Wang Y, Gilmore TD. Three mutations in v-Rel render it resistant to cleavage by cell-death protease caspase-3. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1526:25–36. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(01)00092-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkett M, Xue D, Horvitz HR, Gilmore TD. Phosphorylation of IkappaB-alpha inhibits its cleavage by caspase CPP32 in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:29419–29422. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.47.29419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PJ, Karin M. Nuclear factor-kappaB: a pivotal transcription factor in chronic inflammatory diseases. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1066–1071. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704103361506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauder B, Suchy A, Gabler C, Weissenbock H. Apoptosis in feline panleukopenia and canine parvovirus enteritis. J Vet Med B Infect Dis Vet Public Health. 2000;47:775–784. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0450.2000.00411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyaert R, Heyninck K, Van Huffel S. A20 and A20-binding proteins as cellular inhibitors of nuclear factor-kappa B-dependent gene expression and apoptosis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;60:1143–1151. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00404-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitko V, Shulyayeva O, Mazumder B, Musiyenko A, Ramaswamy M, Look DC, Barik S. Nonstructural proteins of respiratory syncytial virus suppress premature apoptosis by an NF-kappaB-dependent, interferon-independent mechanism and facilitate virus growth. J Virol. 2007;81:1786–1795. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01420-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boatright KM, Renatus M, Scott FL, Sperandio S, Shin H, Pedersen IM, Ricci JE, Edris WA, Sutherlin DP, Green DR, Salvesen GS. A unified model for apical caspase activation. Mol Cell. 2003;11:529–541. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boatright KM, Salvesen GS. Mechanisms of caspase activation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:725–731. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudko SP, Kuhn RJ, Rossmann MG. The coiled-coil domain structure of the Sin Nombre virus nucleocapsid protein. J Mol Biol. 2007;366:1538–1544. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.12.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulares AH, Yakovlev AG, Ivanova V, Stoica BA, Wang G, Iyer S, Smulson M. Role of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) cleavage in apoptosis. Caspase 3-resistant PARP mutant increases rates of apoptosis in transfected cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22932–22940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.22932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgriff TM. Hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome: four decades of research. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:313–316. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-110-4-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgriff TM, Lewis RM. Mechanisms of disease in hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome. Kidney Int Suppl. 1991;35:S72–S79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding R, Pommier Y, Kang VH, Smulson M. Depletion of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase by antisense RNA expression results in a delay in DNA strand break rejoining. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:12804–12812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding R, Smulson M. Depletion of nuclear poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase by antisense RNA expression: influences on genomic stability, chromatin organization, and carcinogen cytotoxicity. Cancer Res. 1994;54:4627–4634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donepudi M, Mac Sweeney A, Briand C, Grutter MG. Insights into the regulatory mechanism for caspase-8 activation. Mol Cell. 2003;11:543–549. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw WC, Martins LM, Kaufmann SH. Mammalian caspases: structure, activation, substrates, and functions during apoptosis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:383–424. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis FA, Cruz J, Spiropoulou CF, Waite D, Peters CJ, Nichol ST, Kariwa H, Koster FT. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome: CD8+ and CD4+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes to epitopes on Sin Nombre virus nucleocapsid protein isolated during acute illness. Virology. 1997;238:380–390. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flick K, Hooper JW, Schmaljohn CS, Pettersson RF, Feldmann H, Flick R. Rescue of Hantaan virus minigenomes. Virology. 2003;306:219–224. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(02)00070-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzoso G, Carlson L, Poljak L, Shores EW, Epstein S, Leonardi A, Grinberg A, Tran T, Scharton-Kersten T, Anver M, Love P, Brown K, Siebenlist U. Mice deficient in nuclear factor (NF)-kappa B/p52 present with defects in humoral responses, germinal center reactions, and splenic microarchitecture. J Exp Med. 1998;187:147–159. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.2.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaddy DF, Lyles DS. Oncolytic vesicular stomatitis virus induces apoptosis via signaling through PKR, Fas, and Daxx. J Virol. 2007;81:2792–2804. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01760-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavrilovskaya IN, Brown EJ, Ginsberg MH, Mackow ER. Cellular entry of hantaviruses which cause hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome is mediated by beta3 integrins. J Virol. 1999;73:3951–3959. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3951-3959.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavrilovskaya IN, Shepley M, Shaw R, Ginsberg MH, Mackow ER. beta3 Integrins mediate the cellular entry of hantaviruses that cause respiratory failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:7074–7079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardestam J, Klingstrom J, Mattsson K, Lundkvist A. HFRS causing hantaviruses do not induce apoptosis in confluent Vero E6 and A-549 cells. J Med Virol. 2005;76:234–240. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung T, Zhou JY, Tang YM, Zhao TX, Baek LJ, Lee HW. Identification of Hantaan virus-related structures in kidneys of cadavers with haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome. Arch Virol. 1992;122:187–199. doi: 10.1007/BF01321127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson CaSCS. Replication of Hantaviruses. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2001;256:15–32. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-56753-7_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JI, Park SH, Lee PW, Ahn BY. Apoptosis is induced by hantaviruses in cultured cells. Virology. 1999;264:99–105. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaukinen P, Vaheri A, Plyusnin A. Non-covalent interaction between nucleocapsid protein of Tula hantavirus and small ubiquitin-related modifier-1, SUMO-1. Virus Res. 2003;92:37–45. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(02)00312-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelliher MA, Grimm S, Ishida Y, Kuo F, Stanger BZ, Leder P. The death domain kinase RIP mediates the TNF-induced NF-kappaB signal. Immunity. 1998;8:297–303. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80535-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy NJ, Kataoka T, Tschopp J, Budd RC. Caspase activation is required for T cell proliferation. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1891–1896. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.12.1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingstrom J, Hardestam J, Stoltz M, Zuber B, Lundkvist A, Linder S, Ahlm C. Loss of cell membrane integrity in puumala hantavirus-infected patients correlates with levels of epithelial cell apoptosis and perforin. J Virol. 2006;80:8279–8282. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00742-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BH, Yoshimatsu K, Maeda A, Ochiai K, Morimatsu M, Araki K, Ogino M, Morikawa S, Arikawa J. Association of the nucleocapsid protein of the Seoul and Hantaan hantaviruses with small ubiquitin-like modifier-1-related molecules. Virus Res. 2003a;98:83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EG, Boone DL, Chai S, Libby SL, Chien M, Lodolce JP, Ma A. Failure to regulate TNF-induced NF-kappaB and cell death responses in A20-deficient mice. Science. 2000;289:2350–2354. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5488.2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TH, Huang Q, Oikemus S, Shank J, Ventura JJ, Cusson N, Vaillancourt RR, Su B, Davis RJ, Kelliher MA. The death domain kinase RIP1 is essential for tumor necrosis factor alpha signaling to p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 2003b;23:8377–8385. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.22.8377-8385.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmers B, Salmena L, Bidere N, Su H, Matysiak-Zablocki E, Murakami K, Ohashi PS, Jurisicova A, Lenardo M, Hakem R, Hakem A. Essential role for caspase-8 in Toll-like receptors and NFkappaB signaling. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:7416–7423. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606721200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Li H, Blitvich BJ, Zhang J. The Aedes albopictus inhibitor of apoptosis 1 gene protects vertebrate cells from bluetongue virus-induced apoptosis. Insect Mol Biol. 2007;16:93–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2007.00705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XD, Kukkonen S, Vapalahti O, Plyusnin A, Lankinen H, Vaheri A. Tula hantavirus infection of Vero E6 cells induces apoptosis involving caspase 8 activation. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:3261–3268. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XD, Makela TP, Guo D, Soliymani R, Koistinen V, Vapalahti O, Vaheri A, Lankinen H. Hantavirus nucleocapsid protein interacts with the Fas-mediated apoptosis enhancer Daxx. J Gen Virol. 2002;83:759–766. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-4-759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin KI, Lee SH, Narayanan R, Baraban JM, Hardwick JM, Ratan RR. Thiol agents and Bcl-2 identify an alphavirus-induced apoptotic pathway that requires activation of the transcription factor NF-kappa B. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:1149–1161. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.5.1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Los M, Stroh C, Janicke RU, Engels IH, Schulze-Osthoff K. Caspases: more than just killers? Trends Immunol. 2001;22:31–34. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(00)01814-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda A, Lee BH, Yoshimatsu K, Saijo M, Kurane I, Arikawa J, Morikawa S. The intracellular association of the nucleocapsid protein (NP) of hantaan virus (HTNV) with small ubiquitin-like modifier-1 (SUMO-1) conjugating enzyme 9 (Ubc9) Virology. 2003;305:288–297. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marianneau P, Cardona A, Edelman L, Deubel V, Despres P. Dengue virus replication in human hepatoma cells activates NF-kappaB which in turn induces apoptotic cell death. J Virol. 1997;71:3244–3249. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.3244-3249.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markotic A, Hensley L, Geisbert T, Spik K, Schmaljohn C. Hantaviruses induce cytopathic effects and apoptosis in continuous human embryonic kidney cells. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:2197–2202. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marusawa H, Hijikata M, Watashi K, Chiba T, Shimotohno K. Regulation of Fas-mediated apoptosis by NF-kappaB activity in human hepatocyte derived cell lines. Microbiol Immunol. 2001;45:483–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2001.tb02648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micheau O, Tschopp J. Induction of TNF receptor I-mediated apoptosis via two sequential signaling complexes. Cell. 2003;114:181–190. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00521-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mir MA, Duran WA, Hjelle BL, Ye C, Panganiban AT. Storage of cellular 5' mRNA caps in P bodies for viral cap-snatching. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19294–19299. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807211105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mir MA, Panganiban AT. Trimeric hantavirus nucleocapsid protein binds specifically to the viral RNA panhandle. J Virol. 2004;78:8281–8288. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.15.8281-8288.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mir MA, Panganiban AT. The hantavirus nucleocapsid protein recognizes specific features of the viral RNA panhandle and is altered in conformation upon RNA binding. J Virol. 2005;79:1824–1835. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1824-1835.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mir MA, Panganiban AT. The bunyavirus nucleocapsid protein is an RNA chaperone: possible roles in viral RNA panhandle formation and genome replication. Rna. 2006;12:272–282. doi: 10.1261/rna.2101906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohsin MA, Morris SJ, Smith H, Sweet C. Correlation between levels of apoptosis, levels of infection and haemagglutinin receptor binding interaction of various subtypes of influenza virus: does the viral neuraminidase have a role in these associations. Virus Res. 2002;85:123–131. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(02)00008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parish JL, Kowalczyk A, Chen HT, Roeder GE, Sessions R, Buckle M, Gaston K. E2 proteins from high- and low-risk human papillomavirus types differ in their ability to bind p53 and induce apoptotic cell death. J Virol. 2006;80:4580–4590. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.9.4580-4590.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters CJ, Khan AS. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome: the new American hemorrhagic fever. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1224–1231. doi: 10.1086/339864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters CJ, Simpson GL, Levy H. Spectrum of hantavirus infection: hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome and hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Annu Rev Med. 1999;50:531–545. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.50.1.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman MM, McFadden G. Modulation of tumor necrosis factor by microbial pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:4. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanathan HN, Chung DH, Plane SJ, Sztul E, Chu YK, Guttieri MC, McDowell M, Ali G, Jonsson CB. Dynein-dependent transport of the hantaan virus nucleocapsid protein to the endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi intermediate compartment. J Virol. 2007;81:8634–8647. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00418-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanathan HN, Jonsson CB. New and Old World hantaviruses differentially utilize host cytoskeletal components during their life cycles. Virology. 2008;374:138–150. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravi R, Bedi A, Fuchs EJ. CD95 (Fas)-induced caspase-mediated proteolysis of NF-kappaB. Cancer Res. 1998;58:882–886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuther JY, Baldwin AS., Jr Apoptosis promotes a caspase-induced amino-terminal truncation of IkappaBalpha that functions as a stable inhibitor of NF-kappaB. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:20664–20670. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanova LI, Lidsky PV, Kolesnikova MS, Fominykh KV, Gmyl AP, Sheval EV, Hato SV, van Kuppeveld FJ, Agol VI. Antiapoptotic activity of the cardiovirus leader protein, a viral "security" protein. J Virol. 2009;83:7273–7284. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00467-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmaljohn C, Hjelle B. Hantaviruses: a global disease problem. Emerg Infect Dis. 1997;3:95–104. doi: 10.3201/eid0302.970202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmaljohn CS, Hasty SE, Harrison SA, Dalrymple JM. Characterization of Hantaan virions, the prototype virus of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome. J Infect Dis. 1983;148:1005–1012. doi: 10.1093/infdis/148.6.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmaljohn CS, Nichol ST. In: Bunyaviridae In "Virology". Knipe D, editor. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 2006. pp. 1741–1789. 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz EM, Badorff C, Hiura TS, Wessely R, Badorff A, Verma IM, Knowlton KU. NF-kappaB-mediated inhibition of apoptosis is required for encephalomyocarditis virus virulence: a mechanism of resistance in p50 knockout mice. J Virol. 1998;72:5654–5660. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5654-5660.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severson W, Partin L, Schmaljohn CS, Jonsson CB. Characterization of the Hantaan nucleocapsid protein-ribonucleic acid interaction. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33732–33739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.47.33732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severson WE, Xu X, Jonsson CB. cis-Acting signals in encapsidation of Hantaan virus S-segment viral genomic RNA by its N protein. J Virol. 2001;75:2646–2652. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.6.2646-2652.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stennicke HR, Jurgensmeier JM, Shin H, Deveraux Q, Wolf BB, Yang X, Zhou Q, Ellerby HM, Ellerby LM, Bredesen D, Green DR, Reed JC, Froelich CJ, Salvesen GS. Pro-caspase-3 is a major physiologic target of caspase-8. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:27084–27090. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser A, O’Connor L, Dixit VM. Apoptosis signaling. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:217–245. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]