Abstract

Progressive realisation is invoked as the guiding principle for countries on their own path to universal health coverage (UHC). It refers to the governmental obligations to immediately and progressively move towards the full realisation of UHC. This paper provides procedural guidance for countries, that is, how they can best organise their processes and evidence collection to make decisions on what services to provide first under progressive realisation. We thereby use ‘evidence-informed deliberative processes’, a generic value assessment framework to guide decision making on the choice of health services. We apply this to the concept of progressive realisation of UHC.

We reason that countries face two important choices to achieve UHC. First, they need to define which services they consider as high priority, on the basis of their social values, including cost-effectiveness, priority to the worse off and financial risk protection. Second, they need to make tough choices whether they should first include more priority services, first expand coverage of existing priority services or first reduce co-payments of existing priority services. Evidence informed deliberative processes can facilitate these choices for UHC, and are also essential to the progressive realisation of the right to health. The framework informs health authorities on how they can best organise their processes in terms of composition of an appraisal committee including stakeholders, of decision-making criteria, collection of evidence and development of recommendations, including their communication. In conclusion, this paper fills in an important gap in the literature by providing procedural guidance for countries to progressively realise UHC.

Keywords: health economics, health policy, health systems

Key questions.

What is already known about this topic?

Countries are recommended to progressively realise universal health coverage, and to make explicit choices regarding the expansion of priority services, the inclusion of more people and reduction of out-of-pocket payments.

Countries should use fair processes to be accountable to their populations.

What are the new findings?

This paper provides practical procedural guidance to countries on how they can best organise their decision-making process to make these choices in a well reasoned and publicly accountable manner.

Recommendations for policy

Countries are recommended to establish evidence-informed deliberative processes.

The use of these processes has consequences for the composition of an appraisal committee including stakeholders, choice of decision-making criteria, collection of evidence and development of recommendations, including their communication and options for appeal.

Introduction

Sustainable development goal (SDG) 3.8 seeks to achieve universal health coverage (UHC), including financial risk protection, access to quality essential healthcare services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all.1 Progressive realisation is invoked as the guiding principle for countries on their own path to UHC and achievement of the SDG health targets. It refers to the governmental obligations to immediately and progressively move towards the full realisation of UHC, recognising the constraints imposed by limited available resources.2 3

The WHO report ‘Making fair choices on the path to universal health coverage’ provides strategic advice to countries committed to achieving UHC.2 This paper follows up on the report, and provides procedural guidance to countries, that is, on how they can best organise their decision-making process to make well reasoned and publicly accountable choices on their path to UHC. It thereby fills an important gap in the literature. The paper is especially relevant for governmental health authorities, at national or subnational levels, in charge of overseeing and guiding the progress towards UHC.

To achieve UHC, countries must make important choices at two levels. First, they need to classify their services in priority classes. Prioritising services is not straightforward, and often involves difficult trade-offs between various values that a country finds important. Countries may, for example, attach extra value to services that are cost-effective, target severe diseases or disadvantaged populations, and provide financial risk protection from the impoverishing impact of ill-health.2 Countries need to establish such a list of high priority services, and periodically update it, for example, every 4 years. Many countries may already have established their priority services in the context of their essential package of health services, as part of their strategy to achieve UHC. Examples are Chile, Ghana, Mexico, Nigeria, Rwanda, Thailand and Vietnam.4

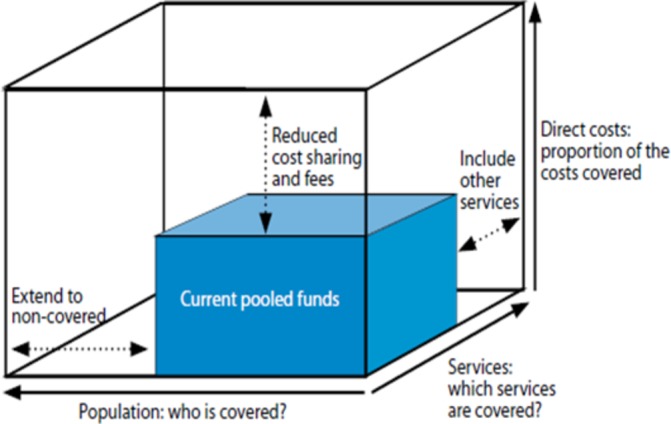

Second, countries need to make difficult choices regarding the implementation of high priority services, in terms on what they do first (and next) on their path to UHC. Progressive realisation of UHC is specifically related to these types of incremental decisions. Countries can advance in at least three dimensions: include more priority services in the essential package, expand coverage of existing priority services to non-covered populations or reduce out-of-pocket payments for existing priority services (figure 1).2 We call these implementation options. For example, implementation options may be to increase the coverage of skilled birth attendance by making it available to all rural populations, or to reduce co-payments for antibiotic treatment of children with pneumonia. Which implementation option they choose to do first may have far-reaching consequences for the level and distribution of health in the country, and of financial risk protection. Countries should therefore recognise that these choices should preferably be made among implementation options on all three dimensions simultaneously. We consider this interpretation of progressive realisation, in terms of making choices among a set of implementation options, as a further operationalisation of the mentioned WHO report.2 Countries should make these choices on a recurrent, ongoing basis, always within the envelope of available resources in current and future fiscal years.

Figure 1.

Three dimensions to consider when moving to universal health coverage.

This paper is organised as follows. The next section spells out the core principles of public accountability, and required processes for progressive realisation of UHC. Following sections provide guidance on the classification of services in priority classes, and on how to choose between implementation options in terms of what to do first. The final section puts these issues in a broader perspective.

Public accountability

In making choices between services and implementation options on the path to UHC, health authorities should be accountable to the populations they serve. Information about their decisions and actions should be transparently available in accessible formats, which requires freedom of information laws; authorities should be required to justify their criteria and decisions when questioned; and remedies should be available when agreed-upon services are not available in practice, or when such decisions have been shown to be arbitrary or discriminatory. The public’s role is to actively hold the health authorities accountable, but institutions such as Ombuds offices, courts and other independent review mechanisms are required to ensure effective enjoyment of health rights in practice.5

Meaningful public accountability can facilitate progressive realisation of UHC in various ways. It forces decision makers to be more systematic, explicit and transparent, by making decisions sensitive to a wider range of needs and values, and by promoting consistency across decisions. It can also make the implementation of decisions more efficient by addressing disagreement at an earlier stage and by facilitating ownership, by discouraging fraud and waste, and by promoting collaboration within the community. Accountability is central to health systems and health reforms, including the post-2015 development agenda.2

‘Evidence-informed deliberative processes’ is a value assessment framework that explicitly addresses this issue of public accountability, and builds on existing tools for health technology assessment such as ‘Accountability for Reasonableness’6 and ‘Multi-criteria decision analysis’.7 The framework spells out how policy makers can best organise their processes.8 9 On the one hand, it is based on early, continued stakeholder deliberation to identify relevant values and to foster a shared understanding among stakeholders of these values. Stakeholders may be members of the public, but may also involve actors such as patient groups, health workers, hospitals, insurers or manufacturers, at the national or international level. These stakeholders each bring in important interests, values and considerations, and the framework aims to balance these interests, and foster decisions that are justifiable and considered reasonable by all involved stakeholders. On the other hand, evidence-informed deliberative processes are based on reasoned decision making—through evaluation of the identified values.

Health authorities in many countries already have a process in place which often involves stakeholders and uses evidence. But the way this is organised is often not ideal in terms of accountability—stakeholder involvement is not meaningful or it comes late, and relevant values are not always identified in time or not at all. Also, the collection of evidence on only a limited set of values is often incomplete. ‘Evidence-informed deliberative processes’ proposes a vision for how health authorities should ideally organise their process. This ideal should not be interpreted as a blueprint for authorities but rather as an aspirational goal; countries are advised to take incremental steps towards this goal.

First choice: The use of evidence-informed deliberative processes to identify high-priority services

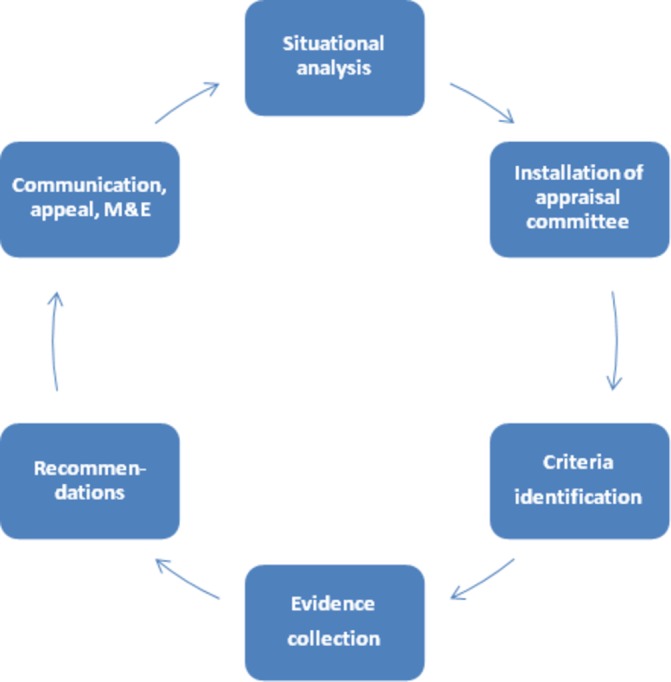

Health authorities first need to classify services in low-priority, medium-priority and high-priority classes, and they should periodically review this, for example, every 4 years. The use of evidence-informed deliberative processes has implications for the organisation of processes to support this (figure 2), and we discuss this for all six steps below.

Figure 2.

The organisation of evidence-informed deliberative processes. M&E, monitoring and evaluation.

Step 1: Situational analysis

The situational analysis serves to map out disease prevalence, severity, level of service coverage and of financial risk protection. The situational analysis should also identify relevant stakeholders.

Step 2: Establishment of an appraisal committee

Authorities are advised to establish an appraisal committee that steers the various activities in the decision-making process, and finally develops recommendations to the health authorities on which services should be classified as high priority. This committee should ideally comprise a variety of stakeholders as their members. Permanent members should be installed to advocate for the broad public interest. Temporary members can be included to represent specific stakeholders including their interests and expertise—making their appointment dependent on the recommendation under scrutiny. Temporary members do not have mandate to develop recommendations.

In certain countries, stakeholder participation in appraisal committees may not be possible. Alternatively, stakeholders can be involved through a citizen council as in the UK, or soliciting input and feedback from patients as in Canada and Scotland. Yet, meaningful stakeholder participation involves interaction and deliberation.9

Step 3: Identification of interventions and criteria

Health authorities, in consultation with stakeholders, are advised to establish a list of services for appraisal. Health authorities are advised to identify explicit decision-making criteria for selecting high-priority services, with criteria referring to the formal operationalisation of stakeholders’ values. The WHO report ‘Fair choices on the path to UHC’ has proposed three such criteria2:

Cost-effectiveness: Priority should be given to the most cost-effective policies. This is typically motivated by the goal of health maximisation, that is, to obtain as much benefit as possible from the available resources.

Priority to the worse off: Priority should be given to the policies benefiting the worse off groups in terms of health and socioeconomic status. As to the latter, many countries face significant coverage gaps, especially among rural populations, the poor and marginalised groups due to gender, race or social status. This implies that an expansion of such services to an underserved poor and rural population should take priority over an expansion to a well off, urban population, at least where other things are roughly equal. Reasons for this can be framed in terms of the importance of health and health services to individuals and society, respect for the right to health and social solidarity relating to equal and affordable access.

Financial risk protection: Out-of-pocket medical payments can lead to impoverishment within households. Protection from financial risks associated with healthcare expenses has emerged as a critical component of national health strategies in many countries.

Other generic criteria (ie, criteria that are relevant across a broad selection of services) include ‘safety’ and ‘effectiveness’ of services. In addition, ‘contextual’ criteria are relevant to further help classify high-priority services. These may relate to various considerations, for example, ‘individual responsibility for health’ for services targeting behaviour-related diseases such as smoking.10

In order not to overlook criteria, health authorities are advised to develop a checklist including their range of generic and contextual criteria. Several classifications of decision criteria can be used as starting points for this.10–12 The specification of criteria in such a checklist is important, as it may have far-reaching consequences for the choice of services—this should take place through a robust public deliberation and participatory procedure.13

Step 4: Collection of evidence

Health authorities are advised to generate an evidence base on criteria. The evidence collection on safety and effectiveness of services is relatively well developed.14 Also, methodological guidance for evidence collection on cost-effectiveness of services,15 16 and databases of evidence are available.17–19 Yet, health authorities may be required to make substantial investments to obtain timely and context-specific data on this. The collection of evidence on the criterion ‘priority to the worse off’ can, for example, be estimated by considering healthy life years lost.2 12 20 Methods for the evidence collection on the criterion ‘financial risk protection’ are now being developed through the growing application of extended cost-effectiveness analysis.21

In the event that the abovementioned refined evidence on criteria cannot be generated, authorities are advised to use aggregated data or expert opinion. In addition, the use of evidence-informed deliberative processes will likely lead to the identification of further criteria, and these may also require further qualitative or quantitative assessment.

Step 5: Development of recommendations

In order to develop recommendations on the ranking of services into priority classes, the appraisal committee should make balanced judgements regarding the ranking of the various criteria, and the performance of services on these criteria. The committee can use different strategies to arrive at these judgements.

One useful strategy is to start with the safety and effectiveness considerations, as they are fundamental to approval of services in any health system, and to consider these as knockout criteria. Next, since health maximisation is a prime objective of many health systems, the committee can choose to initially classify services in priority classes on the basis of their cost-effectiveness (with ‘highly cost-effective’ services classified in the high-priority class, etc). The committee should define cost-effectiveness thresholds regarding these classes.22 23 All other criteria can affect this initial classification. The appraisal committee should make an overview of the performance of the various services on these criteria. Such an overview likely combines evidence of a quantitative or qualitative nature—depending on the nature of the criteria. For every criterion, the appraisal committee should argue whether and how it affects the priority class in which a service was initially classified (on the basis of its cost-effectiveness). Arguments brought to table should be subjected to deliberation, and in the end balanced against each other. The committee will eventually need to come to a final recommendation, thereby providing argumentation on which criteria are considered of overriding importance.9 The importance of deliberation regarding the full range of criteria cannot be underestimated; quantitative decision aids such as weights can never fully replace reasoned judgements.24 The evidence to decision framework provides practical guidance including tools on how to organise this deliberative process.25

Interest groups in reality have different capacities to influence the prioritisation process, for example, in some countries there may be a more effective political lobby promoting cancer services over other services. Moreover, disadvantaged groups in society may face challenges that hinder their effective participation in deliberative processes.26 The challenge for the appraisal committee is to mitigate such differences, if present. Importantly, stakeholder involvement in the appraisal committee does not necessarily need to lead to mutual consensus on a recommendation, or to a joint decision. Thus, any particular stakeholder dominance or pressure from strong interest groups is only relevant to the extent the accountable health authority allows this.9 The final decision, and accountability, rests with the accountable health authority.

Step 6: Communication, appeal, regulation and enforcement, monitoring and evaluation

In a democratic society, policy makers hold the authority to make decisions and are accountable for the decision-making process. It is therefore important that health authorities communicate their decisions, including all reasons that have been put forward by the appraisal committee, to justify these decisions. Doing so in transparent and accessible ways will increase the likelihood that stakeholders including citizens who did not participate—and did not go through a learning process—can understand and accept the reasoning underlying the final decision.6

In addition, societal perceptions of what should count as legitimate arguments for recommendations are subject to change over time or with new evidence becoming available. Health authorities should therefore organise a revision and appeal or review mechanism.6 Additionally, the decisions taken must be implemented effectively through regulation, and be subject to enforcement.

Health authorities need a strong system for monitoring and evaluation, to promote accountability and to effectively pursue UHC in general. Authorities should carefully select a set of indicators tailoring SDG indicators to national priorities, invest in health information systems and properly integrate the information in policy making.2

Second choice: The use of evidence-informed deliberative processes to evaluate high priority service implementation options

Whereas health authorities first need to select high priority services (as discussed above), they subsequently need to decide on what to do first regarding different implementation options to make high priority services available. For these choices, the same kind of evidence-informed deliberative processes including the same appraisal committee can be employed, yet with the following specific characteristics.

First, choices on implementation options need to be made on an ongoing, recurrent basis. Second, the appraisal committee should identify implementation options in terms of including more services in the essential package, expanding the coverage of specific services and/or reducing co-payments for specific services. For example, at a certain point in time, an appraisal committee may define the following implementation options: (1) expanding coverage of measles vaccine to rural populations without co-payments; (2) introducing malaria prophylaxis in urban areas with co-payments; and (3) eliminating co-payments for assisted deliveries at current coverage levels. The appraisal committee may also wish to define disinvestment options, to free up resources for investment in the progressive realisation of UHC. Third, the task of an appraisal committee is not restricted to develop strictly positive or negative recommendations. The above process may also lead to recommendations for price negotiation, or the collection of further evidence. Together with stakeholders, health authorities may also identify alternative ways of implementation of services, which may optimise their value.9

Broader considerations

This paper presents practical guidance for health authorities to make two important choices in the context of progressive realisation of UHC. The first type of choice relates to the classification of services in priority classes. In case where countries lack the analytical capacity to make these choices, they may also base their classification on international recommendations in this context, for example, on the essential services for reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health.27 The second type of choice pertains to what health authorities should do, at a certain point in time, to implement these priorities. It is preferable for health authorities to explicitly define implementation options, defined in terms of a service, its coverage level and related co-payment, and use evidence-informed deliberative process to make these important choices. Health authorities are advised to make institutional arrangements that facilitate processes for making both types of choices.

Many health authorities often already have some sort of evidence-informed deliberative process in place,4 28 and we advise them to incrementally improve on these, according to local needs and affordances. For example, authorities may decide to organise deliberation, or publish their argumentation vis-à-vis their recommendations. Various other proposed approaches to priority setting are based on the same principles of stakeholder deliberation and evidence gathering29 30—these may also provide important lessons for authorities. In general, these approaches comprise the same steps described in this paper.

The guidance provided here is centred around the concept of ‘progressive realization’ and is to be understood in two different ways. First, as the progression towards UHC over time. Second, with ‘progressive’ being interpreted in the social sense as ensuring that equity concerns are fully considered in decision making, such as reducing coverage gaps of essential services for those currently left behind.31

To be truly robust, accountability and participation mechanisms should be institutionalised. Many countries that have succeeded in moving towards UHC—such as Mexico, Rwanda, Thailand, and Turkey—have created innovative institutions that promote accountability and participation.4 These can surely be strengthened. Nevertheless, when robust participation and accountability are included, and protections against legal and de facto discrimination accompany it, such an evidence-informed deliberative process is consistent with priority setting for the progressive realisation of the right to health. The latter is recognised by virtually every country in the world through the international treaties states have ratified, and is increasingly enshrined and enforced in national legal systems.5 32

This paper provides technical guidance to countries on how to make service choices on their path to UHC, and addresses various political aspects, such as stakeholder involvement and development of recommendations in the context of stakeholder dominance. Yet, it does not address broader political issues such as the role of pressure groups on determining the total budget envelop for healthcare and therefore UHC. These issues are nevertheless important for countries to consider in their efforts to achieve UHC, and further integration of political sciences in the development of methods for healthcare priority setting is critical.33

Finally, achieving UHC also requires broad health financing changes, such as increasing mandatory, progressive prepayment with pooling of funds.34

Conclusion

The use of evidence-informed deliberative processes fills in an important gap in the literature on UHC. It responds to key questions that countries have, that is, how they can best organise their processes and evidence collection to make decisions on what services to provide first under progressive realisation. In this way, the framework contributes to the quest of countries to progressively realize UHC as an important SDG.

Box Identifying high priority services in HIV/AIDS control in West Java province, Indonesia.

In Indonesia, West Java is among the provinces with the highest HIV prevalence, and its provincial AIDS commission is responsible for coordination of HIV/AIDS activities. Here we describe the use of an evidence-informed deliberative process to select high-priority services for the 5 years (2014–2018) HIV/AIDS strategic plan of the AIDS commission.

The implementation followed similar steps as described in the main text to identify priority services, and was carried out by the West Java provincial AIDS commission (named health authorities hereafter), supported by Padjadjaran University in Bandung, and Radboud university medical centre in the Netherlands. In step 1, the health authorities analysed the HIV prevalence among key populations, its future spread and coverage of services, and conducted a stakeholder analysis to identify relevant stakeholders in West Java. In step 2, on the basis of this analysis, an appraisal committee was established including government staff from the health office, labour office, education office and the coordinating body for family planning (n=6); staff from community organisations working on family planning and representing people living with HIV/AIDS and high-risk groups (n=4); programme managers from the West Java AIDS commission (n=7); and researchers with backgrounds in economics and epidemiology working on HIV/AIDS at Padjadjaran University (n=6). In step 3, this committee discussed criteria to prioritise services, with, as inputs, the results of a local survey on the importance of criteria for priority setting, WHO treatment guidelines, and implicit criteria used during the development of former National and West Java strategic plans. Each committee member first identified his/her own top five criteria, and these were subsequently discussed together, resulting in the following criteria: ‘impact on the epidemic’, ‘stigma reduction’, ‘cost-effectiveness’ and ‘universal coverage’. In addition, a larger group of 70 stakeholders proposed a total of 50 services for potential prioritisation in the strategic plan. In step 4, the health authorities collected evidence on the performance of these services on all criteria, on the basis of international literature, a locally adapted HIV disease model, and, if necessary, expert opinion. All evidence, including a grading of its quality, was presented as scores in a performance matrix. In step 5, on the basis of this matrix, and in a deliberative process, the appraisal committee agreed on high-priority services. In step 6, the appraisal committee developed an implementation plan, in terms of task division and the identification of funders per service. The results of the priority setting process were included in West Java’s 5-year (2014–2018) strategic document for HIV/AIDS control, which was presented to the governor for approval in 2016.

This example illustrates the use of an evidence-informed deliberative process to select high-priority services (as spelled out in section 3 of the main text), with the exception of organising activities related to communication, appeal, or monitoring and evaluation mechanisms.

Footnotes

Contributors: RB wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MPJ, LB, NT, AEY, OFN contributed towards writing the further versions.

Funding: Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. Goal 3: ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages, 2016. http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/health/.

- 2. WHO Consultative Group on Equity and Universal Health Coverage. making fair choices on the path to UHC. Geneva 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jamison DT, Summers LH, Alleyne G, et al. Global health 2035: a world converging within a generation. Lancet 2013;382:1898–955. (London, England) 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62105-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Glassman A, Chalkidou K. Priority setting in health: building institutions for smarter public spending. Washington: D.C.: center for Global Development, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yamin AE. Taking the Right to Health seriously: implications for Health Systems, Courts, and Achieving Universal Health Coverage. Hum Rights Q 2017;39:341–68. forthcoming 10.1353/hrq.2017.0021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Daniels N. Accountability for reasonableness. BMJ 2000;321:1300–1. 10.1136/bmj.321.7272.1300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Thokala P, Devlin N, Marsh K, et al. Multiple Criteria Decision analysis for Health Care Decision making--an introduction: report 1 of the ISPOR MCDA emerging good Practices Task Force. Value Health 2016;19:1–13. 10.1016/j.jval.2015.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Baltussen R, Jansen MP, Mikkelsen E, et al. Priority setting for Universal Health Coverage: we need Evidence-Informed Deliberative Processes, not just more evidence on Cost-Effectiveness. Int J Health Policy Manag 2016;5:615–8. 10.15171/ijhpm.2016.83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Baltussen R, Paul Maria Jansen M, Bijlmakers L, et al. Value Assessment Frameworks for HTA Agencies: the Organization of Evidence-Informed Deliberative Processes. Value Health 2017;20:256–60. forthcoming 10.1016/j.jval.2016.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Norheim OF, Baltussen R, Johri M, et al. Guidance on priority setting in health care (GPS-Health): the inclusion of equity criteria not captured by cost-effectiveness analysis. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 2014;12:18 10.1186/1478-7547-12-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tromp N, Baltussen R. Mapping of multiple criteria for priority setting of health interventions: an aid for decision makers. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:454 10.1186/1472-6963-12-454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Norheim OF. Ethical priority setting for universal health coverage: challenges in deciding upon fair distribution of health services. BMC Med 2016;14:75 10.1186/s12916-016-0624-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Richardson H. Democratic autonomy. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924–6. 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Drummond MF, O'Brien B, Stoddart GJ, et al. ; Methods for the Economic evaluation of Health Care Programmes. Oxford Universitry Press: Oxford, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tan Torres T, Baltussen R, Adam T. al. e. making choices in Health: who Guide to Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tufts Medical Center. Cost-effectiveness analysis registry Boston, 2017. Available from http://healtheconomics.tuftsmedicalcenter.org/cear4/Home.aspx.

- 18. Disease Control Priorities Network. Disease Control Priorities. third edition, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 19. World Health Organisation. WHO-CHOICE database on cost-effectiveness. http://www.who.int/choice/en/.

- 20. Ottersen T, Førde R, Kakad M, et al. A new proposal for priority setting in Norway: open and fair. Health Policy 2016;120:246–51. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Verguet S, Kim JJ, Jamison DT. Extended Cost-Effectiveness analysis for Health Policy Assessment: a Tutorial. Pharmacoeconomics 2016;34:913–23. 10.1007/s40273-016-0414-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bertram MY, Lauer JA, De Joncheere K, et al. Cost-effectiveness thresholds: pros and cons. Bull World Health Organ 2016;94 (forhcoming) 10.2471/BLT.15.164418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Woods B, Revill P, Sculpher M, et al. Country-Level Cost-Effectiveness Thresholds: initial estimates and the Need for further research. Value Health 2016;19:929–35. 10.1016/j.jval.2016.02.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Baltussen R. Presented at: zorginstituut Nederland, Expert meeting ACP on Multi Criteria Decision analysis, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, et al. GRADE Working Group. GRADE evidence to decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: introduction. BMJ 2016;353:i2016 i2016 10.1136/bmj.i2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rohrer K, Rajan D. Chapter 2. Population consultation on needs and expectations. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 27. The Partnership for Maternal Health NaCHatAKU. Essential Interventions, Commodities and Guidelines for Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn and Child Health. A global review of the key interventions related to reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28. World Bank. Universal Health Coverage Studies Series. http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/health/publication/universal-health-coverage-study-series.

- 29. Glassman A, Giedion U, Sakuma Y, et al. Defining a Health Benefits Package: what are the necessary processes? Health Systems & Reform 2016;2:39–50. 10.1080/23288604.2016.1124171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Terwindt F, Rajan D, Soucat A. Chapter 4. priority setting for national health policies, stratgeies and plans Strategizing national health in the 21st century: a handbook: World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rasanathan K, O'Connell T, Yablonski J, et al. Brief: moving towards universal health coverage to realize the right to healthcare for every child. New York: UNICEF. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rumbold B, Baker R, Ferraz O, et al. ; Universal health coverage, priority setting, and the human right to health Lancet. 2017 forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hauck K, Smith PC. The politics of Priority Setting in Health: a Political Economy Perspective. CGD Working Paper 414. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development 2015. http://www.cgdev.org/publication/politics-priority-setting-health-political-economyperspective-working-paper-414. [Google Scholar]

- 34. World Health Organisation. World Health Report 2010 Health systems financing: the path to universal coverage. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]