Abstract

Bcl-6 (B cell lymphoma-6) is a transcriptional repressor required for the differentiation of T follicular helper (TFH) cell populations. Currently, the molecular mechanisms underlying the transcriptional regulation of Bcl-6 expression are unclear. Here, we have identified the Ikaros zinc finger (IkZF) transcription factors Aiolos and Ikaros as novel regulators of Bcl-6. We found that increased expression of Bcl-6 in CD4+ T helper cell populations correlated with enhanced enrichment of Aiolos and Ikaros at the Bcl6 promoter. Furthermore, overexpression of Aiolos or Ikaros, but not the related family member Eos, was sufficient to induce Bcl6 promoter activity. Intriguingly, STAT3, a known Bcl-6 transcriptional regulator, physically interacted with Aiolos to form a transcription factor complex capable of inducing the expression of Bcl6 and the TFH-associated cytokine receptor Il6ra. Importantly, in vivo studies revealed that the expression of Aiolos was elevated in antigen-specific TFH cells compared to that observed in non-TFH effector T helper cells generated in response to influenza infection. Collectively, these data describe a novel regulatory mechanism wherein STAT3 and the IkZF transcription factors Aiolos and Ikaros cooperate to regulate Bcl-6 expression.

Introduction

CD4+ T helper cells are responsible for coordinating a wide array of immune responses. Upon activation, naïve CD4+ T cells differentiate into specific T helper cell subtypes that are critical for coordinating individual activities as part of a pathogen-specific immune response. These include T helper 1 (TH1), TH2, TH17, TH9, TH22, and T follicular helper (TFH) cell populations (1-4). The armamentarium provided by these subsets is diverse, ranging from the TH1-mediated secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ to the critical role of TFH cells in promoting the generation of pathogen-neutralizing antibodies by B cells. This level of CD4+ T cell subtype specialization depends upon unique lineage-defining transcription factors that direct T helper cell development by both activating cell-specific gene expression programs and repressing alternative T helper cell fates (5-8).

One such example is the transcriptional repressor B cell lymphoma 6 (Bcl-6). Bcl-6 is a member of the broad-complex, tramtrack and bric-à-brac-zinc finger (BTB-ZF) family of proteins, and has been identified as a lineage-defining transcription factor required for both TFH cell differentiation and the formation of germinal centers (9-13). Additionally, Bcl-6 is important to numerous aspects of B cell development and function, as well as the differentiation of CD4+ and CD8+ memory T cell populations (5, 14-16). A conserved role for Bcl-6 in the generation of these populations is to repress the expression of a second repressor, B lymphocyte-induced maturation protein-1 (Blimp-1), a direct antagonist of both TFH- and memory cell-associated genes (5). Other Bcl-6 target genes include those that encode the TH1 and TH2 cell lineage-defining transcription factors T-bet and Gata3, as well as genes associated with cell cycle and metabolic regulation (10-12, 14, 17). Thus, through its ability to modulate a litany of developmental and regulatory pathways, Bcl-6 has emerged as a key driver of immune cell differentiation and function.

As with other transcriptional regulators, the expression and activity of Bcl-6 is regulated by cell-intrinsic signaling cascades initiated by extracellular cytokine signals. For example, it is recognized that the cytokines IL-6, IL-12, and IL-21 promote Bcl-6 expression in CD4+ T cells (18-24). In contrast, signaling cascades initiated downstream of IL-2 and IL-7 negatively regulate Bcl-6 (25-30). The differential effects of these cytokines are propagated through the activation of specific STAT factors known to associate with regulatory regions within the Bcl6 gene locus. Specifically, STAT1, STAT3, and STAT4 have been shown to positively regulate Bcl-6 expression, while STAT5 is a demonstrated repressor of Bcl-6(21, 31). Beyond STAT factors, additional transcriptional regulators including Batf and Tcf-1 have been shown to induce Bcl-6 expression (32-35). Despite these important insights, many questions remain regarding the identity of the transcriptional network that regulates Bcl-6 expression in CD4+ T cell populations.

Similar to STAT factors, the five members of the Ikaros Zinc Finger (IkZF) family of transcription factors have been implicated in the differentiation of numerous immune cell types, including T helper cell subsets (36-39). In the current study, we found that the expression patterns of two IkZF factors, Aiolos and Ikaros, correlated with the expression of Bcl-6 in both in vitro-generated TFH-like and in vivo-generated TFH cell populations. Mechanistically, we found that Aiolos and Ikaros were enriched at the Bcl6 promoter and that their association was coincident with chromatin remodeling events consistent with gene activation including increased histone acetylation and histone 3 lysine 4 tri-methylation (H3K4Me3). Surprisingly, we found that Aiolos physically interacted with the known Bcl-6 activator STAT3 to form a novel transcription factor complex capable of inducing Bcl-6 expression. Importantly, we found that Aiolos expression was elevated in antigen-specific TFH cells, as compared to non-TFH effector cells, generated in response to influenza infection. Collectively, our findings identify Aiolos as a novel regulator of Bcl-6 expression and uncover an unexpected, cooperative relationship between IkZF and STAT transcription factors that may be an important regulatory feature in the specification of T helper cell differentiation programs.

Materials and Methods

Primary cells, cell culture, and nucleofection

Naïve CD4+ T cells were isolated from the spleens and lymph nodes of 5-8 week old age- and sex-matched C57BL/6 mice using the MagCellect CD4+ T cell isolation kit (R&D Systems) per the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were plated at a density of ∼5.0 × 105 cells/well in complete Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium [“cIMDM”: IMDM (Life Technologies), 10% FBS (26140079, Life Technologies), 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (Life Technologies), 0.05% β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma Aldrich)] and stimulated using plate-bound anti-CD3ε (5 μg/ml, BD Biosciences) and anti-CD28 (10 μg/ml, BD Biosciences) in the presence of TH1-polarizing conditions: 5 ng/ml IL-12 (R&D Systems), 5 μg/ml anti-IL-4 (BioLegend, 11B11), and 20 ng/ml IL-2 (Peprotech). After 72h, cells were removed from stimulation and expanded to plate at 5 × 105 cells/well in TH1-polarizing conditions containing either “high” IL-2 (20 ng/ml) or “low” IL-2 (0.8 ng/ml) for an additional 2 days to generate TH1 or TFH-like cell populations, respectively (Supplemental Fig. 1A) (28, 30). To generate “Awe et al.” TFH-like cells, CD4+ T cells were cultured as previously described (40). Briefly, naïve CD4+ T cells were isolated as described above and stimulated on plate-bound anti-CD3ε (5 μg/ml) and anti-CD28 (10μg/ml) for 72h in cIMDM in the presence of TFH-polarizing conditions: (10μg/ml anti-IFNγ (BioLegend, XMG1.2), 10μg/ml anti-TGFβ (BioXCell, 1D11), 10μg/ml anti-IL-2 (eBioscience, JES-1A12), 10μg/ml anti-IL-4, 100ng/ml rmIL-6 (R&D Systems), and 50ng/ml rmIL-21 (Peprotech). Subsequently, cells were expanded and placed in fresh media containing 0.8ng/ml IL-2, 100ng/mL rmIL-6, and 50ng/ml rmIL-21 for an additional 48h.TH2 cells were generated under the following polarizing conditions (10 ng/ml IL-4, 20 ng/ml IL-2, 10μg/ml α-IFNγ). All studies involving mice were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Virginia Tech and the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

The murine EL4 T cell line (ATCC, TIB-39) was cultured as previously described (28, 41). EL4 cell nucleofection was performed using the Lonza 4D Nucleofection system (Program CM-120; Buffer SF). Overexpression of proteins was confirmed via immunoblot and endogenous gene expression changes in response to overexpressed proteins were assessed using qRT-PCR analysis. Expression vectors were generated by cloning the coding sequence of genes of interest into the pcDNA3.1/V5-His-TOPO® vector (K4800, Life Technologies). Sequences were confirmed by sequencing with T7 and BGH primers, followed by transfer of the coding sequence into the pEF1/V5-His vector (V920, Life Technologies). The constitutively active STAT3 (“STAT3CA”) expression vector was generated using the methods above in conjunction with the Agilent QuikChange kit (200519) as previously described (42). Expression of each protein was confirmed via immunoblot using both V5- and protein-specific antibodies.

RNA purification and qRT-PCR

RNA was isolated using the NucleoSpin RNA kit (Macherey-Nagel) and cDNA was generated using the SuperScript IV First-Strand Synthesis System (Life Technologies), according to the manufacturers' instructions. cDNA was used at a concentration of 20ng per qRT-PCR reaction with gene-specific primers (Rps18 forward: 5′-GGA GAA CTC ACG GAG GAT GAG-3′, Rps18 reverse: 5′-CGC AGC TTG TTG TCT AGA CCG -3′; Bcl6 forward: 5′-CCA ACC TGA AGA CCC ACA CTC-3′, Bcl6 reverse: 5′-GCG CAG ATG GCT CTT CAG AGT C-3′; Ikzf1 forward: 5′-ACG CAC TCC GTT GGT AAG CCT C-3′, Ikzf1 reverse: 5′-TGC ACA GGT CTT CTG CCA TCT CG-3′; Ikzf2 forward: 5′-ACG CTC TCA CAG GAC ACC TCA G-3′, Ikzf2 reverse: 5′-GGC AGC CTC CAT GCT GAC ATT C-3′; Ikzf3 forward: 5′-GCT GCA AGT GTG GAG GCA AGA C-3′, Ikzf3 reverse: 5′-GTT GGC ATC GAA GCA GTG CCG-3′; Ikzf4 forward: 5′-GAC GCA CTC ACT GGC CAC CTC C-3′, Ikzf4 reverse: 5′-GGC ACC TCT CCT TGT GCT CCT CC-3′; Ikzf5 forward: 5′-TCG GTA CTG CAA CTA TGC CAG C-3′, Ikzf5 reverse: 5′-AGG TGG CGC TCG TAA GCA GAT G-3′; Il6ra forward: 5′-CCA CAT AGT GTC ACT GTG CG-3′, Il6ra reverse: 5′-GGT ATC GAA GCT GGA ACT GC-3′; and Il2ra forward: 5′- CCA CAA CAG ACA TGC AGA AGC C -3′, Il2ra reverse: 5′-GCA GGA CCT CTC TGT AGA GCC TTG-3′) and SYBR Select Mastermix for CFX (Life Technologies). All samples were normalized to Rps18 as a control and either represented relative to Rps18 expression or relative to the indicated control sample.

siRNAnucleofection

Day 5 primary murine TFH-like cells were nucleofected with siGENOMESMARTpool siRNA (Dharmacon, D-051247, D-064214) targeting Ikzf1, Ikzf3, or both, using the Lonza 4D nucleofector system and buffer P3 per the manufacturer's instructions. siGENOME non-targeting siRNA was used as a control (Dharmacon, D-001210-01). Following nucleofection, cells recovered in TH1-polarizing conditions containing low IL-2 (TFH-like polarizing conditions) for 48h. RNA was isolated and changes in gene expression were analyzed via qRT-PCR, including Ikzf1 and Ikzf3 to establish knockdown efficiency.

Immunoblot analysis

Immunoblot analysis of endogenous and overexpressed proteins was performed using standard procedures. Briefly, cell pellets were lysed in 1X SDS-PAGE buffer (50mMTris, pH 6.8, 100mM DTT, 2% SDS, 0.1% bromophenol blue, 10% glycerol) and immediately boiled for 15 minutes. Separation of lysates from an equivalent number of cells by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was followed by immunoblot analysis on 0.45μm nitrocellulose membrane, which had been blocked using 2% instant non-fat dry milk in TBS-T (10mMTris pH 8.0, 150mMNaCl, 0.05% Tween-20). Antibodies used to detect proteins of interest were as follows: Aiolos ([1:500] Active Motif, 39657; [1:5,000] Santa Cruz, sc-18683X), Ikaros ([1:5,000] Santa Cruz, sc-13039X), Eos ([1:1,000] Millipore, ABE1331), Bcl-6 ([1:500] BD Pharmingen, 561520), and V5 ([1:20,000] Invitrogen, R960). β-actin ([1:15,000] Genscript, A00730) expression was used as a control to ensure equivalent protein loading.

Promoter-reporter analysis

A Bcl6 promoter-reporter construct (pGL3-Bcl6) was generated by cloning the regulatory region of Bcl6 (positions -1573 to 0, in base pairs) into the pGL3-Basic vector (Promega). EL4 T cells were nucleofected with expression vectors for Ikaros, Aiolos, Eos, or indicated mutants, in conjunction with pGL3-Bcl6 and a SV40-renilla vector as a control for transfection efficiency. Following 20-24 hours of recovery, samples were harvested and luciferase expression was analyzed using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter system according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega). Abundance of overexpressed proteins was assessed via immunoblot.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

ChIP assays were performed as published (28, 30). In brief, chromatin was harvested from TH1 and TFH-like cells and immunoprecipitated with antibodies to Aiolos (Santa Cruz, sc-18683X, 5μg/IP), Ikaros (Santa Cruz, sc-9859X, 5μg/IP), STAT3 (Santa Cruz, sc-482X, 5μg/IP), H3K4Me3 (Active Motif, 39160, 1μl/IP), H4Ac (Active Motif, 39926, 1μl/IP), H3K27Ac (07-360, Millipore, 1μl/IP), H3K9Ac (06-942, Millipore, 1μl/IP), or IgG control (Abcam, ab6709, 5μg/IP). Precipitated DNA was analyzed by qPCR with gene-specific primers (Bcl6 “A” forward: 5′-GTA CTC CAA CAA CAG CAC AGC-3′, and reverse, 5′- GTG GCT CGT TAA ATC ACA GAG G-3′; Bcl6 “B” forward: 5′-CGA CCT TGA AAC GAA CCC AG-3′, and reverse: 5′-GTG TGG GTA CGT GTA ATG TTT GCC-3′; Bcl6 “C” forward: 5′-CGA GTT TAT GGG TAG GAG AGG-3′, and reverse: 5′-GTC TTC GCT GTA GCA AAG CTC G-3′; Bcl6 “D” forward: 5′-GCG GAG CAA TGG TAA AGC CC-3′, and reverse: 5′-CTG GTG TCC GGC CTT TCC TAG-3′; Il2 forward: 5′-CTG CCA CAC AGG TAG ACT C-3′, and reverse: 5′-GGT CAC TGT GAG GAG TGA TTA GC-3′). Samples were normalized to a standardized total input DNA control followed by subtraction of the IgG antibody as a control for the non-specific binding. The final value represents the percent enrichment of Aiolos, Ikaros, STAT3, H3K4Me3, H4Ac, H3K27Ac, and H3K9Ac.

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay

Co-Immunoprecipitation assays were performed as previously described(17, 30). Briefly, lysates from primary murine TFH-like cells or EL4 cells overexpressing the indicated proteins were immunoprecipitated with an experiment-specific antibody or antibody control. Lysates were then incubated at 4°C in the presence of Protein A or Protein G sepharose beads (Millipore, 16157, 16201) for 1-2 hours. Immunoprecipitated proteins were detected by subsequent immunoblot analysis. The following antibodies were used for immunoprecipitation at 5μg/IP, for both overexpression and primary T cell Co-IP analyses: STAT3 (Santa Cruz, sc-482X), Ikaros (Santa Cruz, sc-9859X). Antibodies used to detect immunoprecipitated proteins were as follows: Aiolos (Active Motif, 39293), Aiolos (Santa Cruz, sc-18683X), STAT3 (Santa Cruz, sc-8019), Ikaros (sc-13039X), and V5 (Invitrogen, R960-25).

Influenza virus infections and in vivo analysis

Influenza virus infections were performed intranasally with 6,500 VFU of A/PR8/34 (PR8) in 100 μl of PBS. Cell suspensions from mediastinallymph nodes (mLNs) were prepared by passing tissues through nylon mesh. Cells from mLNs were resuspended in 150 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3 0.1 mM EDTA for 5 min to lyse red cells. Cell suspensions were then filtered through a 70 mm nylon cell strainer (BD Biosciences), washed and resuspended in PBS with 5% donor calf serum and 10 g/ml FcBlock (2.4G2 -BioXCell) for 10 min on ice before staining with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies or tetramer reagents. Fluorochrome-labeled α-Bcl-6 (K112.91, dilution 1:50), α-Cxcr5 (2G-8, dilution 1:50), α-Aiolos (S48-791, dilution 1:50) and α-CD4 (RM4-5, dilution 1:200) were from BD Biosciences. The IAbNP311-325 MHC class II tetramer (dilution 1:100) was obtained from the NIH Tetramer Core Facility. Intracellular staining for Bcl-6 and Aioloswas performed using the mouse regulatory T cell staining kit (eBioscience) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Flow cytometry was performed using an Attune NxT Flow Cytometer (ThermoFischer Scientific) and data were analyzed usingFlowJo software.

Listeria monocytogenes infections and analysis

All studies utilized 6-10 week old, age- and sex-matched C57B6/J mice that were maintained in specific pathogen-free facilities. Listeria monocytogenes(Lm) was obtained from the ATCC (ATCC® BAA-679™) and cultured in Brain Heart Infusion Agar/Broth following product guidelines. Prior to in vivo inoculation, bacteria density was estimated in liquid broth culture by measuring the absorbance at 600 nm (0.4 OD600 = 7.9 × 108 bacteria/ml). Cultures of Lm were pelleted, washed twice in PBS, and re-suspended in PBS. Mice were inoculated via intravenous (i.v.) injection with 5000 CFUs of Lm in 50 μl of PBS. Lm inoculation dosages were confirmed for each experiment by plating an aliquot of homogenized liver from randomly selected mice 24 hours post-inoculation and calculating the resultant CFUs/mg of tissue.

At 6 days post infection (d.p.i) primary CD4+ T cells were isolated from the spleens of Lm-infected mice using the BioLegendMojosort isolation kit (480033) per the manufacturer's instructions. For subsequent flow cytometry analysis, isolated cells were stained with the following fluorochrome-labeled antibodies: α-CD44 (560452, BD Biosciences), α-PD-1 (11-985, eBioscience), α-Cxcr5 (FAB6198P, R&D Systems), α-CD4 (56-0031, eBioscience) and respective isotype controls (R&D). Briefly, harvested cells were pelleted, washed and then stained with the indicated fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies. Following staining, cells were washed three times with FACS buffer and then resuspended for analysis and sorting on a Sony SH800 flow cytometer. All of the obtained data were analyzed using FlowJo software. CD4+CD44+Cxcr5hiPD1+ TFH cell transcript analysis was conducted as described above (see RNA purification and qRT-PCR).

Statistics

All data represent at least three independent experiments. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean or standard deviation as indicated. For statistical analysis, unpaired t tests or one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison tests were performed to assess statistical significance, as appropriate for a given experiment. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Expression of Aiolos and Ikaros correlate with that of Bcl-6

While it was once widely believed that initial commitment to an individual effector T cell subset was a terminal event, a large body of literature has emerged demonstrating that a substantial degree of flexibility exists between effector T helper cell populations (43-47). It has been postulated that this phenomenon, termed T helper cell plasticity, allows T helper cell subsets to respond to the cellular microenvironment in real-time, in order to provide a more efficient and effective immune response. For example, many studies have demonstrated that TH1 cells maintain flexibility with the TFH cell type (19, 30, 48). More recently, there have also been reports of TH1-biased TFH cell populations (49, 50). Corroborating these studies, our laboratory has previously demonstrated that TH1 cells are capable of upregulating a Bcl-6-dependent TFH-like cell state in response to altered IL-2 signaling (28, 30). Mechanistically, in TH1 cells exposed to low IL-2 environments, increased Bcl-6 expression allows for the repression of the TFH antagonist Blimp-1 and the subsequent expression of a TFH-like cell program (Fig. 1A and (28, 30)). As the induction of Bcl-6 expression is a critical step for the transition from the TH1 to the TFH-like state, our current study aimed to identify the IL-2-sensitive transcription factors that are responsible for regulating Bcl-6 expression.

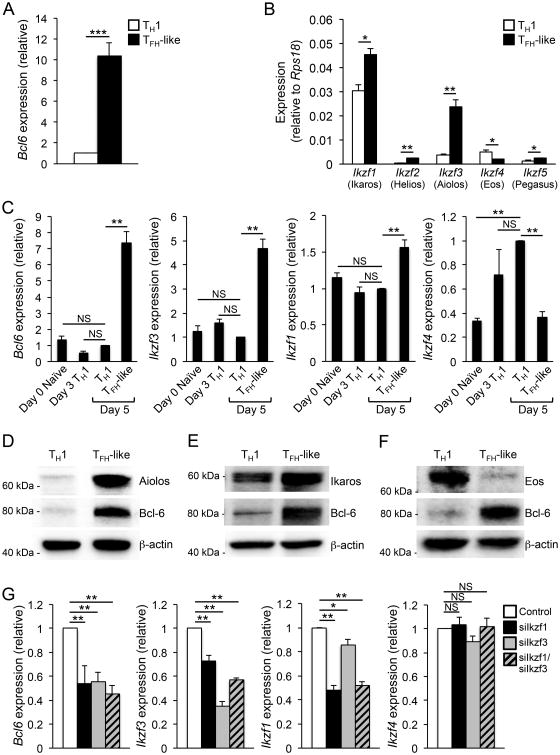

Figure 1.

A positive correlation exists between the expression of Aiolos, Ikaros,and Bcl-6. Primary CD4+ T cells were cultured in TH1 polarizing conditions and exposed to either high (TH1 cells) or low (TFH-like cells) environmental IL-2 (20 ng/ml or 0.8 ng/ml, respectively). (A, B) RNA was isolated from TH1 and TFH-like cells and the expression of the indicated genes was determined by quantitative RT-PCR. Data in ‘A’ are normalized to the Rps18 control and represented as the fold increase relative to the TH1 sample. Data in ‘B’ are normalized and represented relative to the Rps18 control (A, Bmean of n = 4 ± s.e.m.).(C) RNA was isolated from Naïve, Day 3 TH1, and Day 5 TH1 and TFH-like cells and the expression of the indicated genes was determined by quantitative RT-PCR. Data were normalized to Rps18 as a control and the results are represented as fold change in expression relative to the TH1 sample (mean of n = 3 ± s.e.m.). (D-F)An immunoblot analysis was performed to assess changes in protein expression in response to alterations of environmental IL-2. Expression for Bcl-6, Aiolos, Ikaros, and Eos was measured with β-actin serving as a control for equal protein loading. Shown is a representative blot of three independent experiments performed. (G) TFH-like cells were nucleofected with either siRNA specific to Ikaros (siIkzf1), Aiolos (siIkzf3), both (siIkzf1/siIkzf3), or a control siRNA. Following a 48-hour time period, RNA was harvested and expression of the indicated genes was assessed by qRT-PCR. The data were normalized to Rps18 and presented as fold change in expression relative to the control (mean of n = 4 ± s.e.m.).*P< 0.05, **P< 0.01, ***P< 0.001 (A,Bunpaired Student's t-test; C, G one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison test).

Members of the IkZF transcription factor family have previously been implicated in the differentiation of specific effector T helper cell subsets including TH1, TH17, and TREG populations (37, 51-54). As such, we began by assessing whether these factors were differentially expressed in in vitro generated TH1 versus TFH-like cells (Supplemental Fig. 1A). We found that two IkZF factors, Ikaros (Ikzf1) and Aiolos (Ikzf3), were upregulated in TFH-like cells, while a third IkZF family member, Eos (Ikzf4), was more highly expressed in TH1 cells (Fig. 1B). Although two additional IkZF family members, Helios (Ikzf2) and Pegasus (Ikzf5), also displayed altered expression, their overall transcript levels were much lower than those of the other IkZF factors (Fig. 1B). A time-course encompassing the naïve CD4+ T cell transition to differentiated TH1 or TFH-like cell populations further demonstrated that increased Aiolos expression correlated with the highest expression of Bcl-6, while Eos expression was elevated in Day 3 and 5 TH1 cells (Fig. 1C and Supplemental Fig. 1A). Though there was a slight increase in Ikaros expression in TFH-like cells, the expression was relatively abundant across CD4+ T cell populations, perhaps implying a broader role for this factor in T helper cell differentiation (Fig. 1C). In addition to our in vitro-generated TFH-like cells, other laboratories have generated TFH-like cells using alternative in vitro culturing conditions (40, 48). Importantly, analysis of Ikaros and Aiolos expression revealed a similar trend among the TFH-like populations, compared to that observed for in vitro-generated TH1 or TH2 cells (Supplemental Fig. 1B). Furthermore, similar expression patterns were observed in TFH cells generated in vivo in response to Listeria monocytogenes infection (Supplemental Fig. 1C). Collectively, these gene expression analyses indicated that a positive correlation exists between Aiolos (Ikzf3), Ikaros (Ikzf1), and Bcl6 expression.

To determine whether protein expression correlated with the observed changes in transcript, we performed immunoblot analyses of Aiolos, Ikaros, Eos, and Bcl-6 expression in TH1 and TFH-like cells. Indeed, we observed a sharp increase in Aiolos expression that was consistent with increased expression of Bcl-6 in TFH-like cells (Fig. 1D). As with the transcript data, Ikaros expression was moderately elevated in TFH-like cells, while Eos protein expression inversely correlated with that of Bcl-6 and the other two IkZF family members (Figs. 1E and 1F). Given the positive correlation between Aiolos, Ikaros, and Bcl-6, we focused on elucidating possible mechanisms by which these IkZF factors may contribute to the induction of Bcl-6 expression.

Knockdown of Aiolos or Ikaros results in reduced Bcl6 expression

To further assess whether Aiolos or Ikaros may be involved in promoting Bcl-6 expression, we utilized an siRNA knockdown approach to determine whether reduced expression of either factor affected Bcl-6 expression in TFH-like cells. Indeed, upon knockdown of either Aiolos (Ikzf3) or Ikaros (Ikzf1) individually, we observed decreased expression of Bcl6 transcript, while a combined knockdown of Ikzf1 and Ikzf3 resulted in a further reduction of Bcl6 expression (Fig. 1G). Importantly, Eos (Ikzf4) levels remained unchanged, demonstrating the specificity of the Aiolos- and Ikaros-dependent effects upon Bcl-6 expression. These data also demonstrate the specificity of the siRNAs for the intended Ikzf1 and Ikzf3 targets, an important consideration given the high degree of conservation between IkZF family members (36). Collectively, these data support a role for Aiolos and Ikaros in the positive regulation of Bcl-6 expression.

The ZF DNA-binding domains of Aiolos and Ikaros are required to induce Bcl6 promoter activity

To determine whether Aiolos and Ikaros may interact with regulatory regions of the Bcl6 locus, we performed an in silico analysis of the Bcl6 promoter and located several predicted binding sites containing the core IkZF DNA-binding motif, ‘GGGAA’ (Fig. 2A). To test the functionality of these sites, we created a Bcl6 promoter-reporter construct encompassing the predicted sites to examine the effect of Aiolos, Ikaros, or Eos overexpression on Bcl6 promoter activity. Importantly, upon Aiolos or Ikaros overexpression, we observed a significant increase in Bcl6 promoter activity (Fig. 2A). Conversely, as a control, there was no increase in Bcl6 promoter activity in the presence of Eos. These data suggest that Aiolos and Ikaros may induce Bcl-6 expression via effects upon the Bcl6 promoter.

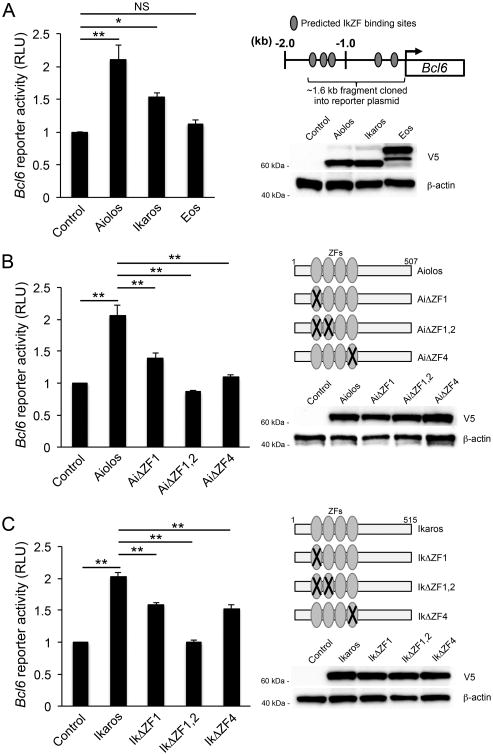

Figure 2.

DNA-binding activity of Aiolos or Ikaros is required to induce Bcl6 promoter activity. (A) EL4 T cells were transfected with the Bcl6 promoter-reporter construct in combination with wild-type Aiolos, Ikaros, or Eos expression vector, or an empty vector control. Luciferase promoter-reporter values were normalized to a renilla control and presented relative to the empty vector control sample for each experiment (mean of n = 3 ± s.e.m.).Aiolos, Ikaros, and Eos protein levels were assessed by immunoblot analysis with an antibody against the V5 epitope tag. Shown is a representative blot of three independent experiments performed. Also shown is a schematic of the Bcl6 promoter with predicted IkZF binding sites depicted as gray ovals. (B, C) EL4 T cells were transfected with the Bcl6 promoter-reporter construct in combination with wild-type (B)Aiolos, or (C) Ikaros expression vectors, the corresponding Aiolos orIkaros ZF mutants (ΔZF), or an empty vector control (mean of n = 3 ± s.e.m.). Luciferase promoter-reporter values were normalized to a renilla control and expressed relative to the empty vector control sample for each experiment. Wild-type and mutant Aiolos or Ikaros protein levels were assessed by immunoblot analysis. Shown is a representative blot of three independent experiments performed. Also shown are schematics depicting wild-type Aiolos or Ikaros and the indicated Aiolos orIkaros zinc finger (ZF) mutants used in the Bcl6 promoter-reporter experiments.*P< 0.05, **P< 0.01, ***P< 0.001 (one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison test).

Aiolos and Ikaros contain N-terminal zinc finger (ZF) domains, which mediate their DNA-binding capabilities. Of the four zinc fingers that comprise the N-terminal domain, zinc fingers 2 and 3 are required for DNA-binding, while zinc fingers 1 and 4 appear to modulate sequence specificity (55, 56). To determine if ZF-mediated DNA binding was required for Aiolos- and Ikaros-dependent Bcl6 promoter activation, we constructed expression vectors with point mutations in select N-terminal ZFs (Aiolos: AiΔZF1, AiΔZF1,2, and AiΔZF4; Ikaros: IkΔZF1, IkΔZF1,2, and IkΔZF4) (Fig. 2B and 2C). We then compared the ability of wild-type Aiolos or Ikaros and their corresponding ZF-mutants to induce Bcl6 promoter activity. As with our previous data, Bcl6 promoter activity was readily induced by wild-type Aiolos or Ikaros (Fig. 2B and 2C). However, we did notobserve increases in Bcl6 promoter activity with either the AiΔZF1,2 or IkΔZF1,2 mutants, suggesting that direct DNA-binding by Aiolos or Ikaros may be required for Bcl-6 induction (Fig. 2B and 2C). Interestingly, overexpression of a subset of the Aiolos and Ikaros mutants with a single ZF mutation in either the first or fourth ZF (AiΔZF1, IkΔZF1, and IkΔZF4) resulted only in a modest increase in Bcl6 promoter activity, suggesting that there may be differential requirements for individual ZFs in mediating promoter activation. Taken together, these results suggest that the N-terminal ZF DNA-binding domain is of functional importance in the Aiolos- and Ikaros-dependent induction of Bcl6 promoter activity.

Aiolos and Ikaros associate with the Bcl6 promoter

As our previous data suggested that Aiolos and Ikaros may induce the activation of Bcl-6 expression and that direct DNA-binding may be required, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays to determine whether either factor directly associates with the endogenous Bcl6 promoter in TFH-like cells (Fig. 3A). Indeed, we observed association of both Aiolos and Ikaros with a region of the Bcl6 promoter proximal to the transcriptional start site (TSS) (Fig. 3B and 3C). Importantly, this association was significantly enriched in TFH-like cells compared to that observed for TH1 cells (Fig. 3B and 3C). Furthermore, the binding observed proximal to the TSS was specific, as enrichment of these factors was markedly reduced at a distal location of the Bcl6 locus. Interestingly, further ChIP analysis for the known Bcl-6 regulator STAT3 revealed a similar enrichment pattern to that observed for Aiolos and Ikaros in TFH-like cells, suggesting the intriguing possibility that these factors may collaboratively regulate Bcl-6 expression (Fig. 3D).

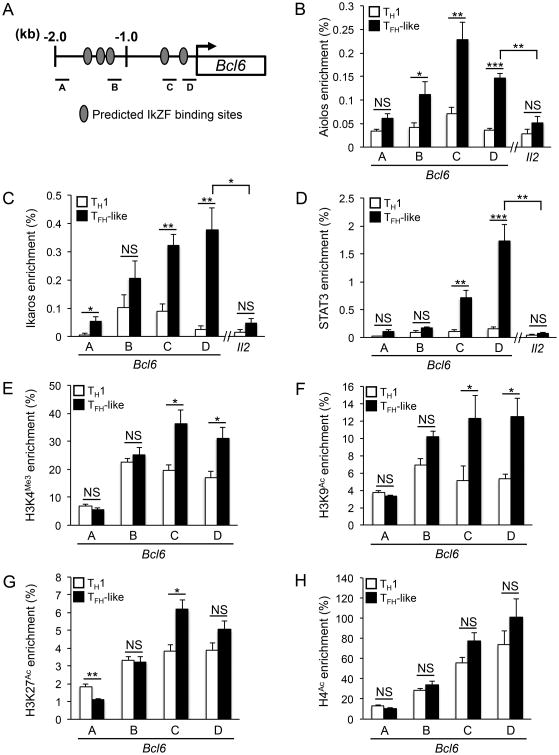

Figure 3.

Aiolos, Ikaros, and STAT3 associate with the Bcl6 promoter in TFH-like cells. (A) A schematic of the Bcl6 locus indicating the location of PCR amplicons used in the chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analyses, indicated as “A”, “B”, “C”, and “D”. (B-D) ChIP assays to assess Aiolos, Ikaros, and STAT3 association with the Bcl6 locus in TH1 or TFH-like cells. Data are represented as percent enrichment relative to a “total” input sample (mean of n = 3 ± s.e.m.). (E-H) ChIP assays to assess alterations to histone modifications within the Bcl6 promoter in TH1 or TFH-like cells. Data are represented as percent enrichment relative to a “total” input sample (mean of n = 4 ± s.e.m.). *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01, ***P< 0.001 (unpaired Student's t-test).

Quintana et al. recently demonstrated that Aiolos directly represses IL-2 production during TH17 cell differentiation (37). As IL-2 signaling negatively regulates Bcl-6 expression, we considered the possibility that Aiolos could contribute to increased levels of Bcl-6 indirectly in a similar, IL-2-dependent fashion. To address this, we examined Aiolos association with the IL-2 (Il2) locus as described in the Quintana study. Interestingly, though there was a slight increase in Aiolos binding at the Il2 locus in TFH-like cells, overall enrichment was much less than that observed at the Bcl6 locus, suggesting that the effect of Aiolos on Bcl6 expression is mediated by a direct mechanism rather than indirectly via an IL-2-dependent effect (Fig. 3B-D). Collectively, these data support a model wherein Aiolos, Ikaros, and STAT3 associate with the Bcl6 promoter to induce Bcl-6 expression in TFH-like cells.

IkZF/STAT factor association correlates with increased histone modification to the Bcl6 promoter

IkZF and STAT factors are known to exert their effects, at least in part, through their association with chromatin remodeling complexes that are capable of directing histone modifications indicative of both gene activation and repression. In order to assess whether Aiolos and Ikaros binding was associated with changes to chromatin structure at the Bcl6 promoter, we performed a ChIP assay to examine alterations in histone acetylation and methylation. Consistent with a role in activating Bcl-6 expression, we observed increased H3K4Me3, H3K9Ac, H3K27Ac, and H4Ac at the Bcl6 promoter in TFH-like cells compared to TH1 cells (Fig. 3E-H). Importantly, significant increases in H3K4Me3, H3K9Ac, and H3K27Ac were detected at regions where Aiolos, Ikaros, and STAT3 were most highly enriched (Fig. 3E-G). Collectively, these data indicate that association of Aiolos, Ikaros, and STAT3 with the Bcl6 promoter correlates with changes in chromatin structure consistent with gene activation.

Aiolos interacts with STAT3 in TFH-like cells

Given the similar enrichment patterns observed for Aiolos, Ikaros, and STAT3 at the Bcl6 promoter, we considered the possibility that they may cooperate to induce Bcl6 expression. To this end, we performed co-immunoprecipitation assays to determine whether these factors interact in TFH-like cells. It is well established that Aiolos and Ikaros form heterodimers via their C-terminal zinc finger domains (36, 56). Indeed, a Co-IP analysis demonstrated that Aiolos and Ikaros form heterodimeric complexes in TFH-like cells (Fig. 4A). Intriguingly, further Co-IP assays revealed the presence of novelAiolos/STAT3 complexes in TFH-like cells (Fig. 4B). Despite the large degree of amino acid conservation between Aiolos and Ikaros, we did not detect the presence of Ikaros/STAT3 complexes in TFH-like cells. Whether this was due to the absence of such complexes, or a limitation of the Co-IP analysis itself, remains unresolved. Still, these findings support the existence of a novel Aiolos/STAT3 protein complex in TFH-like cells.

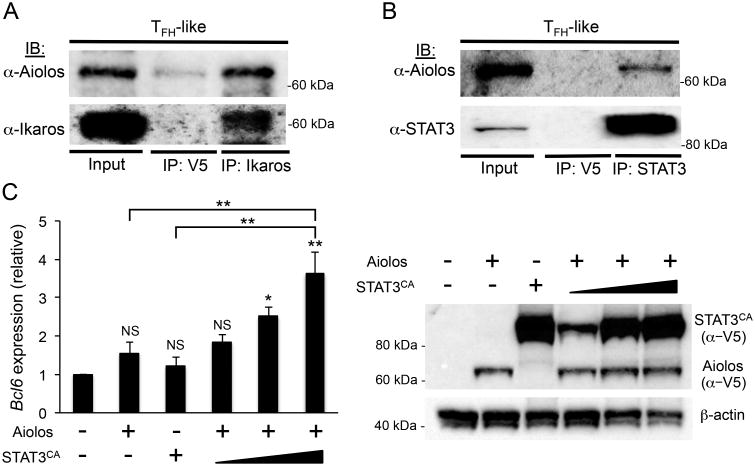

Figure 4.

Aiolos and STAT3 physically interact and regulate Bcl6 expression. (A) Co-immunoprecipiation (Co-IP) of endogenously expressed proteins in TFH-like cells with control antibody (α-V5) or α-Ikaros, followed by immunoblot analysis (IB) with α-Aiolos. Shown is a representative blot of four independent immunoprecipitation experiments performed. (B) Co-IP of endogenously expressed proteins in TFH-like cells with control antibody (α-V5) or α-STAT3, followed by immunoblot analysis (IB) with α-Aiolos. Shown is a representative blot of three independent immunoprecipitation experiments performed. (C) EL4 T cells were transfected with Aiolos alone, STAT3CA alone, Aiolos and STAT3CA (increasing amounts indicated by wedge) in combination, or empty vector control. Immunoblot with anα-V5 antibody was performed to assess relative abundance of overexpressed Aiolos and STAT3CA. Following a 24 hr time period, RNA was isolated and Bcl6 expression was measured by qRT-PCR. Data were normalized to Rps18 as a control and the results are represented as fold change in expression relative to the control (ctrl.) sample (mean of n = 3 ± s.e.m.). *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01 (one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison test).

To examine whether Aiolos and STAT3 may cooperate to induce Bcl-6 expression, we overexpressed a constitutively active form of STAT3 (STAT3CA) alone, Aiolos alone, or Aiolos in combination with increasing amounts of STAT3CA (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, expression of Aiolos or STAT3CA alone resulted in only slight increases in Bcl6 transcript. However, when Aiolos was expressed in combination with increasing amounts of STAT3CA, we observed significant increases in Bcl6 expression compared to the control sample or the samples in which Aiolos or STAT3CA were expressed individually (Fig. 4C).

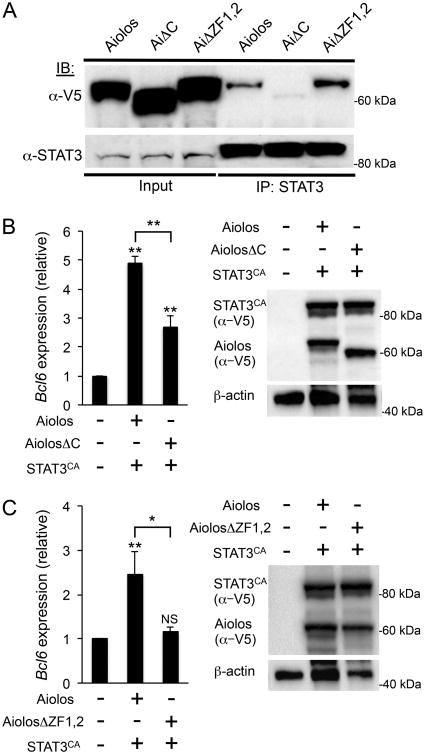

N- and C-terminal ZF domains of Aiolos are required for induction of Bcl-6

In addition to the N-terminal ZF DNA-binding domain discussed previously, members of the IkZF family also contain a C-terminal zinc finger domain that mediates homo- or hetero-dimerization with other IkZFproteins (36, 56). To determine whether either ZF domain may be required for interaction between Aiolos and STAT3, we co-expressed STAT3CA with either wild-type Aiolos or with Aiolos mutants harboring disruptions to either the N- or C-terminal ZF domains and performed Co-IP analysis (Fig. 5A). As with the TFH-like cells, wild-type Aiolos and STAT3 interactions were readily detected. Similarly, we also detected interactions between STAT3 and the AiΔZF1,2 mutant. However, STAT3 was unable to interact with the Aiolos mutant lacking the C-terminal ZF dimerization domain (AiolosΔC), suggesting that this domain is required for the interaction between Aiolos and STAT3 (Fig. 5A). To determine the functional impact of the C-terminal mutation, we overexpressed STAT3CA with either wild-type Aiolos or AiolosΔC and assessed the impact on Bcl6 expression. Indeed, compared to co-expression of wild-type Aiolos with STAT3CA, Bcl6 expression was significantly diminished when STAT3CA was co-expressed with the AiolosΔC mutant (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Functional ZF domains are required for Aiolos-dependent induction of Bcl6 expression. (A) Co-IP of overexpressed wildtype Aiolos or indicated mutants (V5-tagged) and tagless STAT3CA in EL4 cells. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with α-STAT3, followed by immunoblot analysis with α-V5 (for detecting Aiolos proteins). Shown is a representative blot of three independent immunoprecipitation experiments performed. (B) EL4 T cells were transfected with Aiolos and STAT3CA, AiolosαC and STAT3CA, or empty vector control. Immunoblot with an α-V5 antibody was performed to assess relative abundance of overexpressed proteins. Following a 24 hr time period, RNA was isolated and Bcl6 expression was measured by qRT-PCR. Data were normalized to Rps18 as a control and the results are represented as fold change in expression relative to the empty vector control sample (mean of n= 3 ± s.e.m.). (C) EL4 T cells were transfected with Aiolos and STAT3CA, AiolosΔZF1,2 and STAT3CA, or empty vector control. Data were obtained, normalized, and represented as in ‘B’ (mean of n = 6 ± s.e.m.). *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01, ***P< 0.001 (one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison test).

Though the AiΔZF1,2 mutant was able to interact with STAT3, the Bcl6-reporter data suggested that the N-terminal ZF DNA-binding domain was required to induce promoter activity. To determine the functional impact of the N-terminal mutation, we overexpressed STAT3CA with either wild-type Aiolos or AiolosΔZF1,2 and assessed the impact on Bcl6 expression. Indeed, similar to the results observed for the AiolosΔC mutant, the combination of STAT3CA and AiolosΔZF1,2 was unable to induce Bcl-6 expression, suggesting that both the N- and C-terminal ZF domains are required for Aiolos-dependent activation of Bcl-6 expression (Fig. 5C).

Taken together, these data suggest that STAT3 and Aiolos form a transcription factor complex via the Aiolos C-terminal protein-protein interaction domain, and that this novel complex is capable of promoting Bcl-6 expression. It is important to note that while interactions between Ikaros and STAT3 were not detected, our data do not preclude the possibility that such interactions, or interactions between some combination of STAT3, Aiolos, and Ikaros, may play important roles in regulating Bcl-6 expression.

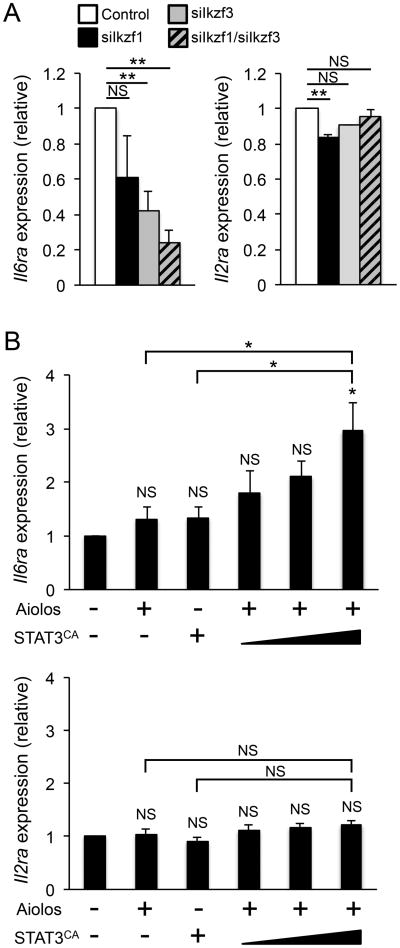

Aiolos and STAT3cooperatively regulate cytokine receptor expression

Our findings suggest that Aiolos and Ikaros are direct regulators of Bcl-6 expression in T helper cells. As discussed previously, signals from environmental cytokines are key determinants of T helper cell differentiation. These include IL-6 and IL-2, which have been shown to positively and negatively influence TFH development, respectively (21, 57, 58). Therefore, we wanted to assess whether Aiolos or Ikaros may play a broader role in promoting TFH cell differentiation by regulating the expression of the receptors for these cytokines. We began by performing Aiolos (Ikzf3) and Ikaros (Ikzf1) siRNA knockdown experiments to assess the effect on Il6ra and Il2ra expression. Indeed, the expression of Il6ra decreased significantly upon Ikzf3 and Ikzf1 knockdown (Fig. 6A). Importantly, this decrease in expression was specific to Il6ra, as the expression of Il2ra was unaffected (Fig. 6A). To determine whether Aiolos and STAT3 may cooperate to induce Il6ra (as with Bcl-6), we overexpressed STAT3CA or Aiolos alone, or Aiolos in combination with increasing amounts of STAT3CA and examined Il6ra expression. Importantly, the co-expression of Aiolos and STAT3CA resulted in a significant increase in Il6ra expression, while the expression of Il2ra was unchanged (Fig. 6B). Collectively, these data suggest that the interplay between Aiolos, Ikaros, and STAT3 may play a broader role in regulating TFH differentiation, perhaps through the induction the cytokine receptor Il6ra.

Figure 6.

STAT3/Aiolos differentially regulate Il6ra and Il2ra expression. (A) TFH-like cells were nucleofected with either siRNA specific to Ikaros (siIkzf1), Aiolos (siIkzf3), both (siIkzf1/siIkzf3), or a control siRNA. Following a 48-hour time period, RNA was harvested and expression of Il6ra or Il2ra was assessed by qRT-PCR. The data are normalized to Rps18 and presented as fold change in expression relative to the control sample (mean of n = 4 ± s.e.m.). (B) EL4 T cells were transfected with Aiolos alone, STAT3CA alone, Aiolos and STAT3CA (increasing amounts indicated by wedge) in combination, or empty vector control. Following a 24 hr time period, RNA was isolated and Il6ra or Il2ra expression was measured by qRT-PCR. Data were normalized to Rps18 as a control and the results are represented as fold change in expression relative to the control sample (mean of n = 3 ± s.e.m.). *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01 (one-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparison test).

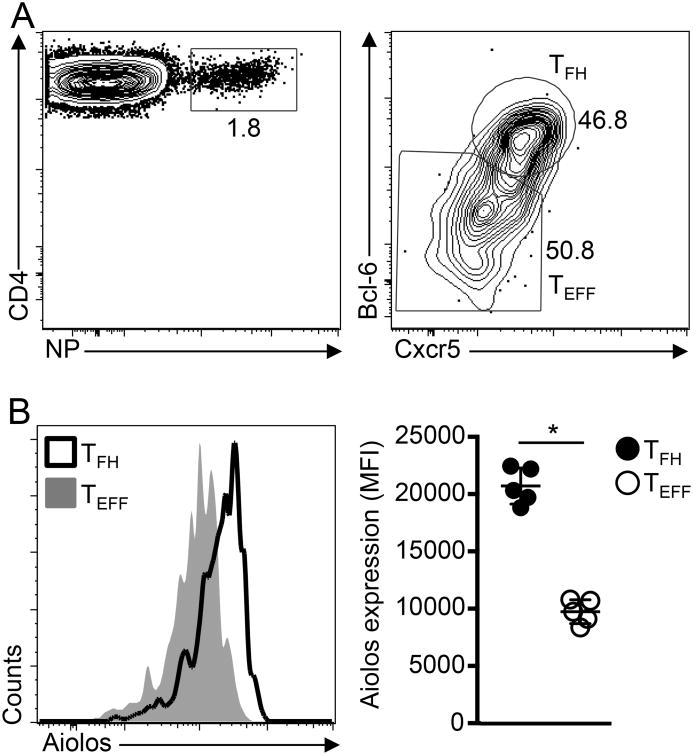

Aiolos expression is increased in antigen-specific TFH cells post-influenza infection

Our mechanistic findings implicate Aiolosin the positive regulation of Bcl-6, and possibly the TFH differentiation program, via a cooperative mechanism with the known TFH regulator STAT3. To extend these findings, we sought to determine whether Aiolos was preferentially expressed inin vivo-generated TFH cells, as opposed to non-TFH effector T helper (TEFF) cells in response to infection. To this end, we infected mice with influenza and assessed Aiolos expression in antigen-specific TFH (Bcl-6hiCxcr5hi) and TEFF (Bcl-6loCxcr5lo) populations (Fig. 7A). Importantly, at the peak of infection (12 days post-infection), nucleoprotein (NP)-specific TFH cells expressed significantly more Aiolos than that observed in the Bcl-6lo TEFF population (Fig. 7B). Collectively, these in vivo data, in combination with our in vitro findings, are supportive of a role for Aiolos in promoting Bcl-6 expression and TFH cell differentiation.

Figure 7.

Aiolos expression is increased in antigen-specific TFH cells post-influenza infection. C57BL/6 mice were infected with influenza(PR8) and NP-specific CD4+CD19-Foxp3- T cells from the mLNs were analyzed on day 12 after infection by flow cytometry. (A) Expression of Bcl-6 and Cxcr5 in NP-specific CD4+CD19-Foxp3- T cells (B) Expression of Aiolos in Bcl6loCXCR5lo (TEFF) andBcl6hiCXCR5hi (TFH)NP-specific CD4+CD19-Foxp3- T cell populations. Histogram overlay and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) in NP-specific TFH and TEFF populations are shown (data are shown as the mean±s.d.(n=5mice/group). *P< 0.05 (P values were determined using a two-tailed Student's t-test).

Discussion

Bcl-6 has well-established roles in the development of a multitude of immune cell types, including TFH cells, memory T cell populations, and B cells. As such, there has been an ongoing interest in identifying the molecular mechanisms involved in the transcriptional regulation of Bcl-6 expression. Here, we describe previously unidentified roles for the IkZF family members Aiolos and Ikaros in the induction of Bcl-6. Perhaps most intriguingly, our data have begun to define a novel, cooperative relationship between STAT3, a known positive regulator of Bcl-6 expression, and the IkZF factor Aiolos.

It is well established that the interplay between opposing STAT factors (e.g. STAT3, STAT5) at the Bcl6 promoter is an important contributor to the regulation of Bcl-6 expression (21, 57, 58). Unexpectedly, our findings demonstrate that STAT3 physically interacts with Aiolos. Thus, our data support the possibility that a primary role for STAT3 may be to recruit Aiolos to the Bcl6 locus. Taken together with the increase in Aiolos expression observed in both in vitro- and in vivo-derived TFH cell populations, these data suggest that this novel IkZF/STAT protein complex may be an important driver of Bcl-6 expression and perhaps TFH cell fate. Indeed, it will be of interest to establish whether the Aiolos/STAT3 complex regulates additional TFH genes beyond Bcl6 and Il6ra. Likewise, given that Aiolos and STAT3 are members of transcription factor families that are both widely expressed and highly conserved, it will be of considerable interest to determine whether STAT and IkZF interactions regulate the differentiation and function of other immune cell populations, including additional T helper cell subsets. For example, Aiolos has been shown to influence TH17 differentiation through the direct repression of IL-2 expression (37). Interestingly, TH17 and TFH cells share a number of regulatory features during their development including sensitivity to the IL-2/STAT5 signaling axis and dependence on STAT3 activity (26, 29, 30, 59, 60). Thus, an intriguing possibility is that the STAT3/Aiolos complex identified here may also play a role in TH17 differentiation.

The precise molecular mechanisms by which STAT3, Aiolos, and Ikaroscooperate to regulate Bcl-6 expression remain unclear. To date, the activity of IkZF factors has been attributed primarily to their association with chromatin modifying enzymes including the switch/sucrose non-fermenting (SWI/SNF) and Mi-2/nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase (Mi-2/NuRD) complexes (56, 61). Indeed, our results demonstrate that the association of Aiolos and Ikaros with the Bcl6 promoter correlates with alterations to the chromatin structure surrounding this region including increased histone acetylation and methylation. These chromatin modifications are indicative of an accessible chromatin structure and consistent with an actively transcribing gene. Our observations are not without precedence, as IkZF factors have been implicated in gene activation prior to the present study (36, 56, 62,63). It is also possible that Aiolos and Ikaros may act to remodel the chromatin structure of regulatory regions located proximal to the Bcl6 promoter. Intriguingly, there are predicted CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) binding sites surrounding this region, suggesting the presence of insulator or silencing elements. Another – non-mutually exclusive – possibility may be that Aiolos and Ikaros association with the Bcl6 promoter near the TSS contributes to the assembly and/or activation of the transcriptional initiation complex. In this regard, Ikaros has been shown to physically interact with, and alter the activity of, the RNA Pol II complex (64). It is also possible that Aiolos and Ikaros may be required to mediate interactions between the Bcl6 promoter and distal enhancers. In support of this possibility, Ikaros has been implicated in promoting long-range chromatin interactions between regulatory elements at other genetic loci (65, 66). Further experimentation will be required to address these possibilities and to understand whether established IkZF remodeling activities are involved, or whether a novel mechanism may be responsible for promoting Bcl-6 expression.

Future studies will also be necessary to comprehensively assess the distinct contributions of Aiolos and Ikaros to the regulation of Bcl-6 expression. Thus far, our data support the existence of STAT3/Aioloscomplexes, but not those comprised of STAT3 and Ikaros, as we could not detect the latter. Still, ChIP analysis of the Bcl6 promoter clearly demonstrates an increase in both Aiolos and Ikaros association at the Bcl6 locus, and we detect the presence of Aiolos/Ikaros complexes in TFH-like cells. Therefore, it is possible that Ikaros and Aiolos could be recruited independently of STAT3 to the Bcl6 locus. However, the signals responsible for Aiolos/Ikarosrecruitment to theBcl6 promoter remain unclear. Based upon our observation that Ikaros is expressed at moderately high levels in naïve and TH1 cells, we propose a model in which a basal level of Ikaros is bound to the Bcl6 locus, perhaps allowing this gene to remain in a poised state during T helper cell differentiation. Indeed, this would be consistent with the established role of Ikaros as a broad regulator of T cell differentiation and our observation that Ikaros is expressed at moderately high levels in naïve and TH1 cells prior to the transition to the TFH-like cell state (36, 61). In our proposed model, we hypothesize that the association of Aiolos/STAT3 complexes with the Bcl6 promoter, in the absence of IL-2/STAT5 signaling, leads to chromatin remodeling activities that result in the activation of Bcl-6 expression. Additionally, as IkZF factors are known to homo- and hetero-dimerize upon binding to DNA, we also propose that IkZF proteins could mediate interactions between distal regulatory elements (65, 66). Further elucidation of the exact contribution of Aiolos and Ikaros to the induction of Bcl-6 will be of interest and may serve to shed light on how STAT3, Aiolos, and Ikaros cooperate to regulate the expression of additional target genes involved in TFH cell differentiation.

The appropriate temporal expression of Bcl-6 is a molecular linchpin that regulates the differentiation and function of many cell types that are critical to the promotion of an effective immune response. The importance of understanding Bcl-6 regulation is further highlighted when considering the numerous human diseases that have been linked to aberrant expression and function of this transcriptional repressor (14, 67). Our findings presented here identify novel regulators and provide insight into the mechanisms by which they promote Bcl-6. Future work will be required to fully elucidate the complex network of signals and factors that regulate Bcl-6 expression. In doing so, we may enhance the potential to design more efficacious vaccines and develop novel immunotherapeutic approaches due to the wide-ranging importance of this transcriptional regulator.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Sheryl Coutermarsh-Ottand Daniel Rothschild for technical assistance with the in vivo studies. The authors would also like to thank Dr. James Smyth and members of the Oestreich lab for insightful discussions.

This work was supported by start-up funds from the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute, a seed grant from the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine (to I.C.A. and K.J.O.), and a Careers in Immunology Fellowship from the American Association of Immunologists (to M.D.P. and K.J.O.). Support for I.C.A. was provided by Virginia Tech and the National Institutes of Health (NIH DK105975).

Support for A.B.T. was provided by the University of Alabama Birmingham (UAB) and National Institutes of Health (NIH R01AI110480).

Abbreviations used in this article

- Bcl-6

B cell lymphoma-6

- Blimp-1

B lymphocyte-induced maturation protein-1

- BTB-ZF

broad-complex, tramtrack and bric-à-brac-zinc finger

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- CTCF

CCCTC-binding factor

- Co-IP

Co-immunoprecipitation

- H3K4Me3

histone 3 lysine 4 tri-methylation

- IkZF

Ikaros zinc finger

- NuRD

nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase

- SWI/SNF

switch/sucrose non-fermenting

- TFH

T follicular helper

- TH1

T helper 1

- TSS

transcriptional start site

- ZF

zinc finger

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.O'Shea JJ, Paul WE. Mechanisms underlying lineage commitment and plasticity of helper CD4+ T cells. Science. 2010;327:1098–102. doi: 10.1126/science.1178334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reiner SL. Development in motion: helper T cells at work. Cell. 2007;129:33–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu J, Paul WE. CD4 T cells: fates, functions, and faults. Blood. 2008;112:1557–69. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-078154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaplan MH, Hufford MM, Olson MR. The development and in vivo function of T helper 9 cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:295–307. doi: 10.1038/nri3824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crotty S, Johnston RJ, Schoenberger SP. Effectors and memories: Bcl-6 and Blimp-1 in T and B lymphocyte differentiation. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:114–20. doi: 10.1038/ni.1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oestreich KJ, Weinmann AS. T-bet employs diverse regulatory mechanisms to repress transcription. Trends Immunol. 2012;33:78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller SA, Weinmann AS. Molecular mechanisms by which T-bet regulates T-helper cell commitment. Immunol Rev. 2010;238:233–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00952.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu J, Yamane H, Paul WE. Differentiation of effector CD4 T cell populations. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:445–89. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beaulieu AM, Sant'Angelo DB. The BTB-ZF family of transcription factors: key regulators of lineage commitment and effector function development in the immune system. J Immunol. 2011;187:2841–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1004006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnston RJ, Poholek AC, DiToro D, Yusuf I, Eto D, Barnett B, Dent AL, Craft J, Crotty S. Bcl6 and Blimp-1 are reciprocal and antagonistic regulators of T follicular helper cell differentiation. Science. 2009;325:1006–10. doi: 10.1126/science.1175870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nurieva RI, Chung Y, Martinez GJ, Yang XO, Tanaka S, Matskevitch TD, Wang YH, Dong C. Bcl6 mediates the development of T follicular helper cells. Science. 2009;325:1001–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1176676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu D, Rao S, Tsai LM, Lee SK, He Y, Sutcliffe EL, Srivastava M, Linterman M, Zheng L, Simpson N, Ellyard JI, Parish IA, Ma CS, Li QJ, Parish CR, Mackay CR, Vinuesa CG. The transcriptional repressor Bcl-6 directs T follicular helper cell lineage commitment. Immunity. 2009;31:457–68. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dent AL, Shaffer AL, Yu X, Allman D, Staudt LM. Control of inflammation, cytokine expression, and germinal center formation by BCL-6. Science. 1997;276:589–92. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5312.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Basso K, Dalla-Favera R. BCL6: master regulator of the germinal center reaction and key oncogene in B cell lymphomagenesis. Adv Immunol. 2010;105:193–210. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(10)05007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ichii H, Sakamoto A, Arima M, Hatano M, Kuroda Y, Tokuhisa T. Bcl6 is essential for the generation of long-term memory CD4+ T cells. Int Immunol. 2007;19:427–33. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxm007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ichii H, Sakamoto A, Hatano M, Okada S, Toyama H, Taki S, Arima M, Kuroda Y, Tokuhisa T. Role for Bcl-6 in the generation and maintenance of memory CD8+ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:558–63. doi: 10.1038/ni802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oestreich KJ, Read KA, Gilbertson SE, Hough KP, McDonald PW, Krishnamoorthy V, Weinmann AS. Bcl-6 directly represses the gene program of the glycolysis pathway. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:957–64. doi: 10.1038/ni.2985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eto D, Lao C, DiToro D, Barnett B, Escobar TC, Kageyama R, Yusuf I, Crotty S. IL-21 and IL-6 are critical for different aspects of B cell immunity and redundantly induce optimal follicular helper CD4 T cell (Tfh) differentiation. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17739. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakayamada S, Kanno Y, Takahashi H, Jankovic D, Lu KT, Johnson TA, Sun HW, Vahedi G, Hakim O, Handon R, Schwartzberg PL, Hager GL, O'Shea JJ. Early Th1 cell differentiation is marked by a Tfh cell-like transition. Immunity. 2011;35:919–31. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nurieva RI, Chung Y, Hwang D, Yang XO, Kang HS, Ma L, Wang YH, Watowich SS, Jetten AM, Tian Q, Dong C. Generation of T follicular helper cells is mediated by interleukin-21 but independent of T helper 1, 2, or 17 cell lineages. Immunity. 2008;29:138–49. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Read KA, Powell MD, Oestreich KJ. T follicular helper cell programming by cytokine-mediated events. Immunology. 2016;149:253–61. doi: 10.1111/imm.12648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmitt N, Bustamante J, Bourdery L, Bentebibel SE, Boisson-Dupuis S, Hamlin F, Tran MV, Blankenship D, Pascual V, Savino DA, Banchereau J, Casanova JL, Ueno H. IL-12 receptor beta1 deficiency alters in vivo T follicular helper cell response in humans. Blood. 2013;121:3375–85. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-08-448902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmitt N, Morita R, Bourdery L, Bentebibel SE, Zurawski SM, Banchereau J, Ueno H. Human dendritic cells induce the differentiation of interleukin-21-producing T follicular helper-like cells through interleukin-12. Immunity. 2009;31:158–69. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vogelzang A, McGuire HM, Yu D, Sprent J, Mackay CR, King C. A fundamental role for interleukin-21 in the generation of T follicular helper cells. Immunity. 2008;29:127–37. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ballesteros-Tato A, Leon B, Graf BA, Moquin A, Adams PS, Lund FE, Randall TD. Interleukin-2 inhibits germinal center formation by limiting T follicular helper cell differentiation. Immunity. 2012;36:847–56. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnston RJ, Choi YS, Diamond JA, Yang JA, Crotty S. STAT5 is a potent negative regulator of TFH cell differentiation. J Exp Med. 2012;209:243–50. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu X, Lu H, Chen T, Nallaparaju KC, Yan X, Tanaka S, Ichiyama K, Zhang X, Zhang L, Wen X, Tian Q, Bian XW, Jin W, Wei L, Dong C. Genome-wide Analysis Identifies Bcl6-Controlled Regulatory Networks during T Follicular Helper Cell Differentiation. Cell Rep. 2016;14:1735–47. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDonald PW, Read KA, Baker CE, Anderson AE, Powell MD, Ballesteros-Tato A, Oestreich KJ. IL-7 signalling represses Bcl-6 and the TFH gene program. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10285. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nurieva RI, Podd A, Chen Y, Alekseev AM, Yu M, Qi X, Huang H, Wen R, Wang J, Li HS, Watowich SS, Qi H, Dong C, Wang D. STAT5 protein negatively regulates T follicular helper (Tfh) cell generation and function. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:11234–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.324046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oestreich KJ, Mohn SE, Weinmann AS. Molecular mechanisms that control the expression and activity of Bcl-6 in TH1 cells to regulate flexibility with a TFH-like gene profile. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:405–11. doi: 10.1038/ni.2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi YS, Yang JA, Crotty S. Dynamic regulation of Bcl6 in follicular helper CD4 T (Tfh) cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2013;25:366–72. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi YS, Gullicksrud JA, Xing S, Zeng Z, Shan Q, Li F, Love PE, Peng W, Xue HH, Crotty S. LEF-1 and TCF-1 orchestrate T(FH) differentiation by regulating differentiation circuits upstream of the transcriptional repressor Bcl6. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:980–90. doi: 10.1038/ni.3226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ise W, Kohyama M, Schraml BU, Zhang T, Schwer B, Basu U, Alt FW, Tang J, Oltz EM, Murphy TL, Murphy KM. The transcription factor BATF controls the global regulators of class-switch recombination in both B cells and T cells. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:536–43. doi: 10.1038/ni.2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu T, Shin HM, Moseman EA, Ji Y, Huang B, Harly C, Sen JM, Berg LJ, Gattinoni L, McGavern DB, Schwartzberg PL. TCF1 Is Required for the T Follicular Helper Cell Response to Viral Infection. Cell Rep. 2015;12:2099–110. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.08.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu L, Cao Y, Xie Z, Huang Q, Bai Q, Yang X, He R, Hao Y, Wang H, Zhao T, Fan Z, Qin A, Ye J, Zhou X, Ye L, Wu Y. The transcription factor TCF-1 initiates the differentiation of T(FH) cells during acute viral infection. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:991–9. doi: 10.1038/ni.3229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.John LB, Ward AC. The Ikaros gene family: transcriptional regulators of hematopoiesis and immunity. Mol Immunol. 2011;48:1272–8. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quintana FJ, Jin H, Burns EJ, Nadeau M, Yeste A, Kumar D, Rangachari M, Zhu C, Xiao S, Seavitt J, Georgopoulos K, Kuchroo VK. Aiolos promotes TH17 differentiation by directly silencing Il2 expression. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:770–7. doi: 10.1038/ni.2363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quirion MR, Gregory GD, Umetsu SE, Winandy S, Brown MA. Cutting edge: Ikaros is a regulator of Th2 cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2009;182:741–5. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.2.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong LY, Hatfield JK, Brown MA. Ikaros sets the potential for Th17 lineage gene expression through effects on chromatin state in early T cell development. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:35170–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.481440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Awe O, Hufford MM, Wu H, Pham D, Chang HC, Jabeen R, Dent AL, Kaplan MH. PU.1 Expression in T Follicular Helper Cells Limits CD40L-Dependent Germinal Center B Cell Development. J Immunol. 2015;195:3705–15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oestreich KJ, Huang AC, Weinmann AS. The lineage-defining factors T-bet and Bcl-6 collaborate to regulate Th1 gene expression patterns. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1001–13. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McLemore ML, Grewal S, Liu F, Archambault A, Poursine-Laurent J, Haug J, Link DC. STAT-3 activation is required for normal G-CSF-dependent proliferation and granulocytic differentiation. Immunity. 2001;14:193–204. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bonelli M, Shih HY, Hirahara K, Singelton K, Laurence A, Poholek A, Hand T, Mikami Y, Vahedi G, Kanno Y, O'Shea JJ. Helper T cell plasticity: impact of extrinsic and intrinsic signals on transcriptomes and epigenomes. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2014;381:279–326. doi: 10.1007/82_2014_371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Geginat J, Paroni M, Maglie S, Alfen JS, Kastirr I, Gruarin P, De Simone M, Pagani M, Abrignani S. Plasticity of human CD4 T cell subsets. Front Immunol. 2014;5:630. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nakayamada S, Takahashi H, Kanno Y, O'Shea JJ. Helper T cell diversity and plasticity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24:297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou L, Chong MM, Littman DR. Plasticity of CD4+ T cell lineage differentiation. Immunity. 2009;30:646–55. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu J, Paul WE. Heterogeneity and plasticity of T helper cells. Cell Res. 2010;20:4–12. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu KT, Kanno Y, Cannons JL, Handon R, Bible P, Elkahloun AG, Anderson SM, Wei L, Sun H, O'Shea JJ, Schwartzberg PL. Functional and epigenetic studies reveal multistep differentiation and plasticity of in vitro-generated and in vivo-derived follicular T helper cells. Immunity. 2011;35:622–32. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Obeng-Adjei N, Portugal S, Tran TM, Yazew TB, Skinner J, Li S, Jain A, Felgner PL, Doumbo OK, Kayentao K, Ongoiba A, Traore B, Crompton PD. Circulating Th1-Cell-type Tfh Cells that Exhibit Impaired B Cell Help Are Preferentially Activated during Acute Malaria in Children. Cell Rep. 2015;13:425–39. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Velu V, Mylvaganam GH, Gangadhara S, Hong JJ, Iyer SS, Gumber S, Ibegbu CC, Villinger F, Amara RR. Induction of Th1-Biased T Follicular Helper (Tfh) Cells in Lymphoid Tissues during Chronic Simian Immunodeficiency Virus Infection Defines Functionally Distinct Germinal Center Tfh Cells. J Immunol. 2016;197:1832–42. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pan F, Yu H, Dang EV, Barbi J, Pan X, Grosso JF, Jinasena D, Sharma SM, McCadden EM, Getnet D, Drake CG, Liu JO, Ostrowski MC, Pardoll DM. Eos mediates Foxp3-dependent gene silencing in CD4+ regulatory T cells. Science. 2009;325:1142–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1176077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rieder SA, Metidji A, Glass DD, Thornton AM, Ikeda T, Morgan BA, Shevach EM. Eos Is Redundant for Regulatory T Cell Function but Plays an Important Role in IL-2 and Th17 Production by CD4+ Conventional T Cells. J Immunol. 2015;195:553–63. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sharma MD, Huang L, Choi JH, Lee EJ, Wilson JM, Lemos H, Pan F, Blazar BR, Pardoll DM, Mellor AL, Shi H, Munn DH. An inherently bifunctional subset of Foxp3+ T helper cells is controlled by the transcription factor eos. Immunity. 2013;38:998–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thornton AM, Korty PE, Tran DQ, Wohlfert EA, Murray PE, Belkaid Y, Shevach EM. Expression of Helios, an Ikaros transcription factor family member, differentiates thymic-derived from peripherally induced Foxp3+ T regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:3433–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schjerven H, McLaughlin J, Arenzana TL, Frietze S, Cheng D, Wadsworth SE, Lawson GW, Bensinger SJ, Farnham PJ, Witte ON, Smale ST. Selective regulation of lymphopoiesis and leukemogenesis by individual zinc fingers of Ikaros. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:1073–83. doi: 10.1038/ni.2707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yoshida T, Georgopoulos K. Ikaros fingers on lymphocyte differentiation. Int J Hematol. 2014;100:220–9. doi: 10.1007/s12185-014-1644-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Crotty S. T follicular helper cell differentiation, function, and roles in disease. Immunity. 2014;41:529–42. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vinuesa CG, Linterman MA, Yu D, MacLennan IC. Follicular Helper T Cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2016;34:335–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-041015-055605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Laurence A, Tato CM, Davidson TS, Kanno Y, Chen Z, Yao Z, Blank RB, Meylan F, Siegel R, Hennighausen L, Shevach EM, O'Shea JJ. Interleukin-2 signaling via STAT5 constrains T helper 17 cell generation. Immunity. 2007;26:371–81. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liao W, Lin JX, Wang L, Li P, Leonard WJ. Modulation of cytokine receptors by IL-2 broadly regulates differentiation into helper T cell lineages. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:551–9. doi: 10.1038/ni.2030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dege C, Hagman J. Mi-2/NuRD chromatin remodeling complexes regulate B and T-lymphocyte development and function. Immunol Rev. 2014;261:126–40. doi: 10.1111/imr.12209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Evans HG, Roostalu U, Walter GJ, Gullick NJ, Frederiksen KS, Roberts CA, Sumner J, Baeten DL, Gerwien JG, Cope AP, Geissmann F, Kirkham BW, Taams LS. TNF-alpha blockade induces IL-10 expression in human CD4+ T cells. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3199. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yap WH, Yeoh E, Tay A, Brenner S, Venkatesh B. STAT4 is a target of the hematopoietic zinc-finger transcription factor Ikaros in T cells. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:4470–8. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bottardi S, Mavoungou L, Milot E. IKAROS: a multifunctional regulator of the polymerase II transcription cycle. Trends Genet. 2015;31:500–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bottardi S, Ross J, Bourgoin V, Fotouhi-Ardakani N, Affar el B, Trudel M, Milot E. Ikaros and GATA-1 combinatorial effect is required for silencing of human gamma-globin genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:1526–37. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01523-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Keys JR, Tallack MR, Zhan Y, Papathanasiou P, Goodnow CC, Gaensler KM, Crossley M, Dekker J, Perkins AC. A mechanism for Ikaros regulation of human globin gene switching. Br J Haematol. 2008;141:398–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tangye SG, Ma CS, Brink R, Deenick EK. The good, the bad and the ugly - TFH cells in human health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:412–26. doi: 10.1038/nri3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.