Summary

Cell death is a perpetual feature of tissue microenvironments; each day under homeostatic conditions, billions of cells die and must be swiftly cleared by phagocytes. However, cell death is not limited to this natural turnover—apoptotic cell death can be induced by infection, inflammation, or severe tissue injury. Phagocytosis of apoptotic cells is thus coupled to specific functions, from the induction of growth factors that can stimulate the replacement of dead cells to the promotion of tissue repair or tissue remodeling in the affected site. In this review, we outline the mechanisms by which phagocytes sense apoptotic cell death and discuss how phagocytosis is integrated with environmental cues to drive appropriate responses.

Keywords: apoptosis, phagocytosis, macrophages, homeostatic clearance, inflammation, tissue repair

Introduction

Vasamsi jirnani yatha vihaya navani grhnati naro ‘parani

tatha sarirani vihaya jirnany anyani samyati navani dehi

[Just as a person leaves behind worn-out garments and puts on others that are new Similarly, (the embodied) leaves behind withered bodies and takes on others that are new]

Bhagavad Gita 2:22

Death is the terminal event for an individual cell. Notwithstanding, for a multicellular organism, the death of an individual cell can bestow continuity of life. Cell death can reshape an organism during development and differentiation in light of its newer needs and requirements. Numerous cells die to enable the transformation of a voraciously feeding lepidopteran larva into an adult butterfly capable of mating and reproducing. In long-lived multicellular organisms that do not undergo metamorphosis, cell death can be an avenue to remove accumulated, unwanted damages and mutations, and a signal to renew, replace, and replenish. Cell death can also be an essential protective mechanism for the survival of the organism. Some species of sponges form a barrier of dead cells to separate self from non-self tissue (1). In other organisms, it can be an early warning of a noxious environment or a pathogen, and the cue to unleash an orchestrated host defense response comprised of specialized cells. Moreover, not all cell death events are identical. While cells may die passively due to disruption of their membrane integrity, chemical damage, or disrepair, many forms of death, such as apoptosis, necroptosis and pyroptosis, are signaled through defined molecular mechanisms. Modalities of cell death have been extensively reviewed elsewhere (2–4). Below we focus on a particular form of cell death– apoptosis– and how cell death can elicit biological responses beneficial to an organism.

Apoptotic Cell Death- Discovery, Features, and Role in Development

The American developmental biologist J.W. Saunders affirmed in 1966 that “abundant cell death, often cataclysmic in its onslaught, is a part of early development in many animals” (5). The original descriptions of cell death come from more than a century before Saunders’s comments. Carl Vogt first examined cartilaginous and notochordal cell death during development in 1842 (6). Initially termed “chromatolysis” or “necrobiosis,” this cell death was observed in many tissues under basal conditions. However, the morphological features of physiological cell death remained unknown until the late 1960s, with the advent of electron microscopy (7–9).

J.F. Kerr took advantage of a liver damage model (9) to define the different stages of maturation of Councilman bodies — small round masses of acidophilic cytoplasm named after the American pathologist William T. Councilman that were present in a variety of pathological conditions in the liver (10). Under physiological conditions, Councilman bodies were rare"but [could] be found in the section after a careful search (9).” Yet just two days after ligation of the portal vein branches, these forms started to accumulate in the tissue. Councilman bodies displayed a striking reduction in the volume of their cytoplasm, marked nuclear condensation and fragmentation, and the separation of protuberances at the membrane, which collectively characterized a distinct mode of cellular death: “shrinkage necrosis” (9). Kerr and colleagues later reviewed these morphological changes and renamed this process apoptosis, a Greek term meaning “ ‘falling off’ of petals from flowers or leaves from trees” (11).

Following Kerr’s work, numerous studies further defined several hallmarks of apoptosis

Shrinkage of the apoptotic corpses was observed in experimental models in which thymocytes were treated with glucocorticoids. These apoptotic thymocytes rapidly reduced their cell volume by one-third, reflecting their previous designation as cells undergoing “shrinkage necrosis” (9, 12). After incubation with probes against several surface markers, apoptotic cells exhibited reduced fluorescence intensity in comparison to healthy control cells, suggesting the presence of similar binding sites on the cell surface of apoptotic cells, but just at reduced numbers. This indeed was due to a reduction in the total membrane surface area, and thus in the average volume of the apoptotic corpse (13).

Treatment of thymocytes with cyclohexamide and actinomycin D inhibited the morphological changes normally induced by apoptosis, thereby demonstrating an additional characteristic of apoptosis: its dependency on active protein synthesis (14).

Chromatin condensation, with parallel DNA fragmentation, was initially identified as a discontinuous band of material underneath the nuclear membrane in dying cells. Activation of an intracellular endonuclease with a preference for double-strand breaks was found to be associated with the cleavage of nucleosome chains from chromatin (15, 16).

Surface changes that provide recognition signals to phagocytes, the cells responsible for ingesting dying cells and debris, represent another cardinal feature of apoptotic cells. Although many molecules are unchanged between the surface of the apoptotic cells and control cells, binding of apoptotic thymocytes to macrophages was 2–4 times higher than the binding of non-apoptotic thymocytes to macrophages (13). Interestingly, while serum was added to these co-cultures, complement was not responsible for this enhanced interaction, indicating a distinct mode of recognition for apoptotic cells (13).

The extensive membrane blebbing consistently seen during apoptosis likely results from weakened cytoskeletal support, as bundles of actin contract in a myosin-dependent manner, and force the cytosol to push against different parts of the plasma membrane (4). These blebs initiate the formation of apoptotic bodies. Although membrane blebbing has not been observed for all cell types, such as neutrophils and thymocytes, it is thought to be a mechanism for cutting large cells into smaller pieces, which can then be more easily engulfed by phagocytes.

Over the last 25 years, considerable progress has been made in delineating the molecular mechanisms leading to apoptosis. The precise molecular players involved in the two main apoptotic pathways— the extrinsic (or death receptor) pathway and the intrinsic (or mitochondrial) pathway— have been well reviewed elsewhere (3, 4, 17). Though the initiating signals differ, these cascades converge on the same execution mediators, caspases. Caspases (cysteine-dependent aspartate-directed proteases) are a highly conserved family of protease enzymes. Fourteen mammalian caspases have been recognized, which have been divided into different categories according to their overlapping substrate specificity (18). Importantly, caspases are synthesized as inactive zymogens, with conversion to the mature, active form of the enzyme requiring a minimum of two cleavages (19). Caspase activity is critical for the induction of many of the intracellular and morphological changes initially described to occur in all cells undergoing apoptosis by Kerr and colleagues. For example, the exposure of phosphatidylserine (PtdSer) on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane is a classical marker of apoptosis that depends on caspase activity (20). Treatment of murine W3 cells with the death receptor ligand FAS-L resulted in cleavage of ATP11C, a flippase that typically transports PtdSer rapidly and uni-directionally from the outer to the inner leaflet in viable cells. In agreement with this, ATP11C was found to harbor three caspase-recognition sites. By mutating the flippase at these motifs, Segawa and colleagues were able to generate a cell line with a caspase-resistant ATP11C that retained its flippase activity following FAS-L stimulation, and these cells no longer exposed PtdSer (20). Knockout (KO) mice for individual caspases in the apoptotic pathway demonstrate striking phenotypes. For example, most Caspase-3 and Caspase-9 KO mice die perinatally, while those that survive have a reduced life span and significant malformations in their brain tissue from hyperplasia (21–24).

As reflected by the perinatal lethality of mutations in apoptotic pathway components, apoptotic cell death plays an essential role in remodeling of organs and limbs during embryonic development. Neurons are initially produced in excess in the developing central nervous system (CNS), with at least 50% not connecting to downstream targets and undergoing apoptosis (25). Embryos from mice either lacking pro-apoptotic factors, such as Apaf1, or over-expressing anti-apoptotic factors, like Bcl-2, displayed severe hypertrophy of the brain and loss of brain architecture (26–28). Ablation of Apaf1, a component of the apoptosome that helps to activate caspases 9 and 3, was also shown to prevent or delay proper elimination of interdigital webbing (26, 27). Proliferation of undifferentiated cells in the distal mesoderm is followed by directed apoptotic cell death in specific regions, resulting in the formation of defined phalanges in the autopod. Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) have been proposed as conserved initiators of this apoptosis in chicken and mouse limb development (29–31). Conditional deletion of Bmp2 and Bmp4 in the early limb bud led to complete syndactyly in newborn mice (32). Likewise, embryonic administration of human recombinant BMP-4 and FGF-2 coupled to bead carriers was sufficient to drive regression of the interdigital webbing that usually remains in duck appendages (33). In line with these findings, a small group of patients with limb malformations, including syndactyly and polydactyly, have been found to have mutations at the Bmp4 locus (34). Therefore, in these and many other developmental settings, a careful balance between proliferation and apoptosis is paramount for organismal viability and maturation.

Today, techniques directed at identifying apoptotic cells are largely based on the characteristics outlined above, including the detection of caspase activation, intact plasma membrane integrity, DNA fragmentation, or exposure of molecules on the plasma membrane, such as phosphatidylserine (PtdSer). These methods must often be used in combination in order to differentiate apoptosis from other forms of cell death. On account of these strategies, apoptotic cells can now be more easily investigated. While apoptosis is indeed prevalent during and necessary for development, it can also be triggered upon a panoply of stimuli in adulthood. Often apoptosis and consequent removal elicits a non-cell autonomous beneficial response. An active response to cell death, however, requires the recognition of dead cells by other constituent cells of the multicellular organism. This typically involves a sentinel cell that can recognize dead or dying cells and communicate this signal to muster a concerted response involving multiple cell types.

Phagocytosis– A Brief Introduction

Recognition of a dead cell by a sentinel cell is often coupled to its phagocytosis. Phagocytosis is a primitive process wherein particles larger than 0.4 µm in diameter are engulfed by cells (35). Phagocytosis is actin-dependent, and occurs via tight flow-over of the plasma membrane on the particle surface. It is triggered at the site where phagocytic receptors interact with their cognate ligand(s). Phagocytosis is distinct from macropinocytosis, in which the ingested particle is taken up into large vacuolar compartments along with extracellular liquid. Macropinocytosis has also been described as a mechanism of engulfing apoptotic cells. Nonetheless, in macropinocytosis, membrane ruffling is initiated spontaneously or by growth factor stimulation. In the latter case, the site of macropinocytosis is independent of the spatial distribution of the growth factor receptors (36, 37). While both phagocytosis and macropinocytosis require membrane protrusion, this is reversed in endocytosis, which occurs by membrane invagination.

Evolutionarily, phagocytosis has been represented as an adapted cell-adhesion mechanism (38). An interesting postulate is that the last eukaryotic common ancestor (LECA) was capable of forming actin-based protrusions that accidentally and occasionally led to the engulfment of bacteria. One such event eventually resulted in endosymbiosis and the origin of mitochondria, as well as the endomembrane system typical of modern phagocytes (39). Phagocytosis is especially important in immune defense – whether in engulfment of bacterial pathogens by neutrophils and macrophages, or in removal of apoptotic cells. As highlighted throughout this review, the clearance of apoptotic cells by phagocytes has the potential to initiate replenishment of dying populations, to curb inflammation, and to launch tissue repair programs.

Sensing of Apoptotic Cell Death

Apoptotic signaling cascades trigger consistent morphological changes in the dying cell that lead to its controlled demise. A subset of these alterations allow for phagocytes to distinguish dying from living cells, with recognition licensing the phagocyte to rapidly engulf and remove any apoptotic cells. The classical first step in phagocytosis is the recruitment of phagocytes to precise sites of apoptosis by the release of “find-me” signals from the apoptotic cell. Distinct from the signals that engage phagocytosis receptors themselves (designated as “eat-me” signals), “find-me” signals include a range of soluble factors that form a chemoattractive gradient, including more conventional chemokines like fractalkine (40), and less classical chemoattractants like ATP and UTP nucleotides (41). In the following section, we specifically discuss the molecular basis of the second stage in phagocytosis— the direct sensing of apoptotic cell death “eat-me” signals and engagement of phagocytic receptors, a process that has notable evolutionary conservation.

The exposure of PtdSer on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane is one of the primary cell surface alterations during early phases of apoptosis, and occurs even with distinct inducers of apoptotic cell death (42). Fadok and colleagues observed that irradiated or Dexamethasone-treated murine thymocytes were engulfed by thioglycollate-elicited peritoneal macrophages in vitro (43). The addition of liposomes containing PtdSer to the culture blocked uptake of the dying cells; critically, engulfment of apoptotic thymocytes was unaffected by other phospholipids, and macrophages maintained their uptake of opsonized irradiated thymocytes in the presence of liposomes (43). These data provided initial support for a model in which PtdSer serves as an “eat-me” signal, enabling engulfment independent of FcR-mediated phagocytosis. Utilization of Annexin-V staining, which selectively binds PtdSer (42, 44), revealed that PtdSer exposure was a common feature of apoptotic cells in developing Drosophila melanogaster, chicken, and mice (45). More recent studies have found that dying cells in the nematode C. elegans become surface PtdSer+ as well, in a process that is dependent on caspases (ced-3 or ced-4) and the aminophospholipid transporter tat-1, although there is some conflicting data on the nature of the contribution of tat-1 (46, 47). Nonetheless, genetic ablation of tat-1 led to aberrant translocation of PtdSer to the outer leaflet of all germ cells in the gonads, and indiscriminate loss of a range of cell types in the nematode (47). Hence controlled exposure of this surface molecule marks apoptotic cells for engulfment across metazoans.

Other “eat-me” signals induced upon apoptotic cell death include surface-bound thrombospondin, calreticulin, ICAM-3, complement subcomponent C1q, and oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL) (48). For instance, apoptotic cells lacking ICAM-3 were poor cargo, with considerably fewer tethering and engulfment interactions between these apoptotic cells and phagocytic cell lines compared to WT apoptotic cells (49). Interestingly, ICAM-3 expression wanes fairly quickly during the early stages of apoptosis in vitro, and is localized instead to membrane blebs that are eventually released from the dying cell. Torr and colleagues found that in vitro the blebs including ICAM-3 functioned as a chemoattractant for macrophages, such that ICAM-3 may additionally serve as a “find-me” signal once restricted to these microparticles (49). In contrast to this collection of pro-engulfment signals, viable cells also express “don’t-eat-me” molecules that impede phagocyte activity. One example of this is CD47, a surface glycoprotein that interacts with SIRPα on a subset of myeloid cells. As mentioned in more depth later in this review, engagement of SIRPα limits engulfment, potentially through activation of SHP proteins by SIRPα, and prevents premature clearance of erythrocytes (50). This regulatory mechanism is also important to protect cells that transiently expose “eat-me” signals on their surface as a part of normal cellular activation, rather than cell death.

Prior to characterization of the precise molecules identifying apoptotic cells, the vitronectin receptor (integrin αvβ3) was implicated for a supplementary role in the engulfment of aged neutrophils (51). Addition of monoclonal antibodies specific to each of the subunits of αvβ3 or the vitronectin ligand specifically impaired the phagocytic capacity of human monocyte-derived macrophages. An array of phagocytic receptors has now been described to mediate the recognition and internalization of apoptotic cargo, matching the variety of “eat-me” signals discussed above. Table 1 summarizes the phagocytic receptors that are involved in the uptake of apoptotic cells in several model organisms, and their ligands for this purpose. A subset of these receptors requires bridging molecules to recognize the “eat-me” signal and tether the apoptotic cell to the phagocyte. It is important to note that some phagocytic receptors described here are also crucial for the engulfment of pathogens and cells undergoing non-apoptotic cell death, and therefore may recognize additional moieties beyond those acknowledged.

Table 1.

Phagocytic receptors involved in recognition of apoptotic cells across model organisms.

| Model Organism |

Phagocyte Populations | Phagocytic Receptors | Ligand(s) Involved in Apoptotic Cell Uptake |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caenorhabditis elegans |

|

CED-1(171)(homology with CD36, MEGF10) | PtdSer |

| PSR-1(172)(homology with JMJD6) | PtdSer/Annexin-I | ||

| Drosophila melanogaster |

|

Croquemort(173) (homology with CD36) | Not yet defined for apoptotic cells |

| Draper(174, 175)(homology with MEGF10) | Pretaporter | ||

| Mus musculus |

Professional:

|

BAI-1(176) | PtdSer |

| TIM-4(177) | PtdSer | ||

| CD300f (178) | PtdSer | ||

| TREM-2(179) | PtdSer, Anionic Lipids | ||

| STAB-2(180) | PtdSer | ||

| AXL(56, 89) | GAS6 (PtdSer) | ||

| TYRO3(56, 89) | PROS1, GAS6 (PtdSer) | ||

| MERTK(56, 89, 181) | PROS1, GAS6 (PtdSer) | ||

| CD14(182, 183) | ICAM-3 | ||

| RAGE(184) | PtdSer | ||

| MEGF10(185, 186) | C1q (PtdSer) | ||

| JEDI-1(185) | Not yet defined | ||

| Integrins | |||

| αvβ3(51) | TSP-1 MFG-E8 (PtdSer) | ||

| αvβ5(187) | TSP-1 MFG-E8 (PtdSer) | ||

| Scavenger Receptors | |||

| CD91(188) | TSP-1, Calreticulin, C1q | ||

| CD36(189) | TSP-1, oxLDL |

In comparison to mammals, Drosophila and C. elegans have considerably fewer apoptotic cell sensors, particularly for the conserved signal PtdSer; nevertheless, both do express homologues of mammalian receptors, including CD36, a scavenger receptor binding a range of ligands in mammals [see Table 1]. Apoptosis and engulfment in C. elegans are mediated by the ced family of proteins. These proteins have high homology for apoptosis-associated components in mammals like caspases, adaptor proteins, and phagocytic receptors (52). In the same tat-1null model described previously, which generates excess PtdSer+ neurons, additional loss of function mutations in phagocytic receptors (psr-1 or ced-1) rescued tat-1null nematodes from the irregular loss of PLM neurons (47). Therefore psr-1 and ced-1 function similarly to phagocytic receptors in mammals that interpret PtdSer exposure as license to engulf a cell. Below, we discuss in more detail the TAM family of phagocytic receptors, which are not represented in Drosophila or C. elegans, in order to illustrate two key principles: differences in the expression pattern of specific apoptotic cell sensors and their potential “division of labor.” Both of these patterns may contribute to the requirement for numerous phagocytic receptors in more complex organisms.

The TYRO3, AXL, and MERTK (TAM) receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) contribute critically to apoptotic cell clearance, as well as to vascular integrity and the regulation of innate immune responses (53, 54). Structurally, the TAM receptors consist of two N’ terminal Immunoglobulin (Ig)-like domains that serve as points of contact with either of the TAM agonists, PROS1 and GAS6. Following two fibronectin type III domains and a transmembrane region, the TAMs contain a kinase domain with a characteristic KWIAIES sequence. PROS1 and GAS6 recognize PtdSer through a region rich in gamma-carboxylated glutamic acid residues (Gla domain), bridge the TAMs to apoptotic targets, and trigger the activation of these RTKs (55).

Similar to other apoptotic cell sensors, the TAM receptors are expressed predominantly on professional phagocytes, which include macrophages and dendritic cells, as well as dedicated, non-professional phagocytes like Sertoli cells and retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells (detailed in (54)). However, the expression of the individual TAM RTKs across myeloid subsets and during different inflammatory settings is not uniform. Phagocyte populations derived from Mertk−/− or Axl−/− Tyro3−/− mice were compared for their capacity to ingest apoptotic thymocytes (56). While deficiency in any of these receptors significantly impaired phagocytosis in peritoneal macrophages in comparison to WT controls, combinatorial Axl and Tyro3 ablation had a more modest effect than Mertk ablation alone. In contrast, Mertk expression was dispensable for engulfment by bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs), whereas Axl−/− Tyro3−/− BMDCs had significant deficits. These patterns in functional assays match later analysis of TAM receptor expression in these different cell populations by western blot; BMDMs exhibited abundant expression of MERTK and low amounts of AXL and TYRO3, while BMDCs (albeit different subsets) expressed AXL or TYRO3 highly, but lower amounts of MERTK (57, 58). Zagorska and colleagues further described a “division of labor” between MERTK and AXL in BMDMs, with MERTK functioning primarily in homeostatic settings and AXL during inflammation (57). Exposure to either immunosuppressive stimuli, like Dexamethasone, or inflammatory stimuli, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), upregulated the expression of MERTK and AXL respectively in BMDMs. Moreover, Axl−/− BMDMs stimulated with inflammatory reagents poly(I:C) or interferon (IFN)-γ exhibited a severe defect in phagocytic uptake of exogenous apoptotic thymocytes. As expected, Axl−/− BMDMs had comparable engulfment to WT BMDMs under standard culture conditions. Taken together, this indicates that Axl gains a central role in macrophage phagocytosis solely in inflammatory settings. These studies underscore that despite recognizing the same motif on apoptotic cells, these phagocytic receptors may be functioning on distinct cell types and in different contexts to mediate apoptotic cell clearance. It should also be noted that expression of the TAMs is not restricted to professional phagocytes, with NK cells, epithelial cells, and stromal cells highly expressing various TAM RTKs (54). These broader expression patterns may reflect other functions of the TAM receptors, and/or the potential for non-professional phagocytes to engulf neighboring apoptotic cells, as also seen in Drosophila and C. elegans.

Lastly, MERTK has been shown to cooperate with another PtdSer-sensing receptor, TIM-4, to carry out successful phagocytosis in resident peritoneal macrophages in vitro (59, 60). When co-cultured with apoptotic thymocytes, deficiency of Tim4 in macrophages nearly abolished the binding and engulfment of the apoptotic cargo, as well as diminished the phosphorylation of MERTK. Intriguingly, Mertk−/− macrophages were able to bind apoptotic cells at close to WT levels, but could not take them up. These findings suggested a model in which TIM-4 tethers the apoptotic cargo to the macrophage, a necessary step for MERTK to then initiate phagocytic engulfment. Reconstituting this system by transformation of murine Ba/F3 cells, the authors observed robust phagocytosis only with the expression of both receptors. Together with other studies (61), these findings serve as evidence for another type of “division of labor,” with receptors on the same cell functioning at distinct steps in phagocytosis. The overlap or redundancy in the expression of phagocytic receptors in mammals may therefore reflect still undiscovered modes of cooperation.

Apoptosis coupled to replenishment and homeostatic tissue function

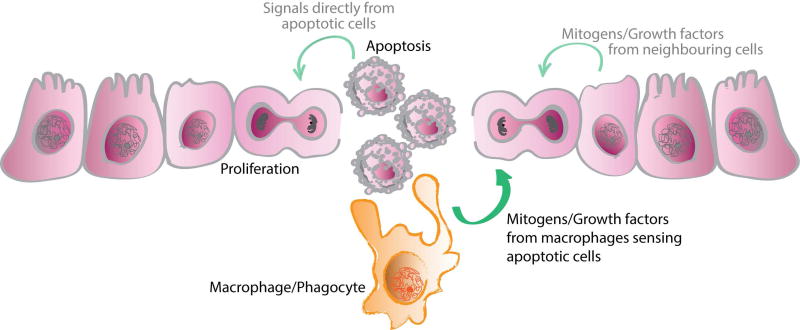

In homeostatic and some developmental settings, many cell populations turn over at a high rate. Subsequent replenishment or replacement of the dying cells is a key step in counteracting the cell loss, sustaining a constant number of cells in each tissue, and preserving overall organ size and structure. This apoptosis-proliferation equilibrium may be maintained directly, with apoptotic cells releasing factors that induce proliferation in surrounding cells, or indirectly, by intermediaries like phagocytes that sense the apoptotic cells (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Apoptotic cell death and subsequent clearance regulates compensatory proliferation during development and homeostasis.

Upon cell death, macrophages or other phagocytic cells sense the apoptotic cell and then release molecules, like mitogens and growth factors, which result in the proliferation or differentiation of cells to replace those that are dying. Factors released from apoptotic cells themselves may directly stimulate proliferation of surrounding cells helping to replenish adjacent populations. Other neighboring cells may likewise serve as mediators.

In Drosophila, compensatory proliferation upon apoptosis has been observed in both developing undifferentiated and differentiated tissues. Cells in the wing imaginal disc proliferate extensively during larval development, but do not differentiate until they reach pupal development (62, 63). Targeted ectopic cell death in this structure resulted in a pattern of proliferating cells adjacent to the apoptotic one, indicative of a compensatory feedback loop (62). Overexpression of the baculovirus p35 caspase inhibitor (64) has been used as an experimental model in which cells acquire the features of apoptotic cells but remain alive (“undead cells”), with p35 blocking caspase activity but not its original activation (65). Initiation of apoptosis was found to activate the JNK pathway in the “undead cells” and to drive their secretion of the mitogens wingless (Wg) and decapentaplegic (Dpp) (66). Activation of the initiator caspase Dronc downstream of the Hid- dependent cell death signaling pathway within these “undead cells” was essential for Wg release and proliferation of adjacent wing imaginal disc cells (67). Wg expression has also been observed in “genuine” dying apoptotic cells, although it should be noted that even higher Wg expression was detected in surrounding proliferating cells (68). However, mutation of Wg and Dpp did not block the compensatory proliferation induced by apoptosis (69), suggesting that mitogen production by apoptotic cells might be just one mechanism for inducing compensatory proliferation in Drosophila. Similar to this proliferating tissue, the activation of the effector caspases drICE and Dcp-1 in photoreceptor neurons prompts Hedgehog-mediated compensatory proliferation of undifferentiated cells in the eye tissue (70). These findings not only revealed a key effect of apoptotic cells on their neighboring healthy cells, but also defined an apoptosis-independent function for initiator and effector caspases directly associated with cell proliferation during development.

Other molecular initiators may also be involved in triggering compensatory proliferation in Drosophila in the case of damage. The polarity complex Cdc42/Par6/Par3/aPKC has been proposed to negatively regulate apoptosis-induced compensatory proliferation. Silencing of Cdc42, as well as of aPKC, accelerated compensatory proliferation responses following irradiation-induced cell damage, although to differing extents. In particular, disruption of this polarity complex led to the activation of JNK-dependent apoptosis in epithelial cells via activation of the Rho1-Rok-myosin pathway, which in turn elicits hyperproliferation through the mechanisms discussed above (71).

Studies in mammals now point to compensatory proliferation as a critical process for the homeostasis of immune cells. The high basal turnover of specific leukocyte populations necessitates persistent control over proliferation. In the thymus, 95% of developing CD4+CD8+ thymocytes die after high affinity TCR recognition of self-peptide-loaded MHC molecules, or conversely following failure to engage their TCR with MHC (72). Response to this apoptotic death in the thymus is associated with retinoid production. Retinaldhyde dehydrogenase (RALDH) expression was found to localize to macrophages within the cortex, the region in which macrophages take up apoptotic thymocytes (73–76). This upregulation of RALDH expression in phagocytic macrophages has been linked to lipid-sensing receptors Liver X Receptor (LXR)-α, LXR-β, peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor (PPAR)-δ, and PPAR-γ (77). The resulting retinoid generation can precisely regulate the fate of other developing thymocytes. On the one hand, retinoids can induce apoptosis in CD4+CD8+ thymocytes (78); yet on the other hand, retinoids induce proliferation of CD4−CD8− thymocytes (79), thus potentially promoting the replacement of the engulfed thymocytes (76).

A vast number of neutrophils also die by apoptosis each day in circulation and must be continuously cleared by macrophages in the spleen, liver, and bone marrow (80). In vitro studies by Furze and colleagues have demonstrated that uptake of apoptotic neutrophils by bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) under basal conditions leads to the secretion of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) (81). This growth factor is essential for granulopoiesis and egress of neutrophils from the bone marrow, and in this way, G-CSF can help preserve the neutrophil count in circulation. Importantly, the increased production of G-CSF was observed only when these phagocytosis experiments were performed in the absence of inflammatory stimuli, like LPS, and when in vitro differentiated macrophages were used as the phagocytic cells (81). These findings illustrate that in vitro phagocytes interpret signals from apoptotic cells differently depending on the surrounding homeostatic or inflammatory microenvironment.

Interestingly, the lack of phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils by phagocytes in vivo has instead been associated with increased serum levels of G-CSF. In order to investigate the factors controlling neutrophil granulopoiesis at homeostasis, Stark and colleagues analyzed mice deficient in Itgb2, the common β2 integrin involved in leukocyte adhesion and extravasation (82). Itgb2−/− mice had neutrophilia in circulation (83), and enhanced secretion of IL-17 by γδ- and unconventional αβ-T-cells compared to wild type (WT) mice. Transfer of WT neutrophils into Itgb2−/− mice was sufficient to reduce IL-23 and IL-17 in the serum to WT levels and to lower circulating neutrophil numbers (82). These results suggest that neutrophil entry into the tissues and subsequent apoptosis may regulate the IL-23/IL-17/G-CSF axis at baseline, helping to maintain the correct number of neutrophils in circulation and in target tissues (82). In line with this latter study, mice lacking multiple macrophage populations exhibited elevated serum levels of G-CSF and high neutrophilia in various tissues, likely due to the impaired uptake of apoptotic neutrophils (84). Altogether, these data indicate that apoptotic cell uptake by various phagocytic populations may modify G-CSF levels and control the replenishment of neutrophils in circulation. The detailed mechanisms of how phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by distinct types of macrophages leads to changes in the amount of G-CSF released in different experimental conditions will require further clarification.

Apoptotic cell death within the hematopoietic compartment has therefore been shown to feedback and regulate cell differentiation and proliferation, with phagocytes at least partially responsible for relaying these signals. While direct experimental evidence of compensatory proliferation has only been provided for limited settings, this process has the potential to function globally, allowing many tissues to maintain their overall size and integrity despite substantial homeostatic cell death. Below we highlight several systems in which high cell turnover is necessary for proper tissue function under physiological conditions. We further emphasize professional or non-professional phagocytes that have been characterized to sense and engulf apoptotic cells in these tissues, and thus are candidates for driving appropriate proliferation responses.

I. Reproductive System

In the adult testis, 75% of germ cells continually undergo apoptosis during differentiation in the seminiferous tubules (85). This extensive cell death together with its appropriate clearance (Figure 2A) is crucial for proper spermatogenesis. Bax-deficient mice showed resistance to cell death in testicular germ cells, with impaired testicular development and spermatogenesis (86). In further support of this, treatment of WT male mice at P7 with testosterone led to lower levels of apoptosis at P28, specifically in germ cells expressing a high level of Bax. When mice reached sexual maturity three weeks later, a significant reduction in the number of spermatozoa was observed (87).

Figure 2. Phagocytic clearance is critical for homeostatic tissue function across various systems.

(A) For proper development of spermatozoa from spermatogonia (right), Sertoli cells must also engulf the many germ cells that undergo apoptosis following defective differentiation. (B) Photoreceptor outer segments are routinely shed following exposure to light and are cleared by retinal pigment epithelial cells. (C) Macrophage engulfment of extruded nuclei from developing erythroblasts is necessary for erythrocyte maturation. (D) The subventricular zone (SVZ) is one site of neurogenesis in the adult brain, with successfully differentiating neurons migrating along the rostral migratory stream (RMS) and reaching the olfactory bulb (OB). Phagocytes, including microglia, are involved in clearing apoptotic neuroblasts, as well as some viable neuroblasts, that result from this neurogenesis.

Despite this high level of cell death, at any one time only a small fraction of the apoptotic cells can be detected due to the phagocytic activity of Sertoli cells. These highly efficient, non-professional phagocytes are dedicated to supporting spermatogenesis and rapidly clearing the population of apoptotic germ cells. The expression of the TAM RTKs by Sertoli cells was found to be required for proper clearance, as young adult mice globally deficient for Tyro3, Axl, and Mertk (TAM TKO) had accumulation of TUNEL+ cells within the seminiferous tubules (88). By 6 months of age, TAM TKO mice displayed prominent defects in their spermatogenesis, with a complete absence of both germ cells and developed spermatozoa. Systematic evaluation of mice lacking individual or combinations of TAM receptors or Gas6, one of their ligands, distinguished Mertk as the primary mediator of this homeostatic clearance, with Mertk−/− mice accruing 20 times the number of cleaved-caspase-3+ cells in the seminiferous tubule as any of the other single receptor KO or WT mice (89). Notably, further loss of Tyro3 and then Axl expression in the absence of Mertk (i.e. Tyro3−/− Mertk−/− or TAM TKO) exacerbated the phenotype. Complementary to this, Elliott and collegues determined that ELMO-1, a cytoplasmic engulfment protein downstream of another phagocytic receptor BAI-1, was essential for the clearance of apoptotic cells in the testis. While Elmo-1 absence is compensated for by expression of Elmo-2 in phagocytic cells from many tissues, Sertoli cells from Elmo-1−/− mice exhibited a decreased capacity to take up apoptotic germ cells. Specific ablation of Elmo-1 in Sertoli cells not only impaired phagocytosis, but also resulted in a substantial reduction in the number of mature sperm, further confirming the fundamental connection between apoptosis and tissue function (90).

Transient physiological conditions, such as pregnancy, can also be accompanied by elevated rates of apoptosis. The presence of apoptotic cells and phagocytic macrophages surrounding the fetus is one histological characteristic of the maternal tissue during pregnancy. Efficient clearance of the apoptotic trophoblast cells prevents an immune response against trophoblast antigens and, by promoting a tolerogenic environment, avoids fetal rejection (91).

II. Visual System

Clearance of retinal debris and renewal of photoreceptor outer segments (POS) is an indispensable component of retinal development and visual function (Figure 2B). Under homeostatic conditions, light exposure triggers the apoptosis and shedding of POS fragments. Studies performed on the rat retina revealed that only 90 minutes of light exposure is sufficient to induce initial signs of apoptosis in POS (92). After two hours of light exposure, the specialized RPE cells employ phagocytic machinery similar to professional phagocytes to begin clearing the POS. Activation of multiple phagocytic receptors, such as MERTK (93–95), CD36 (96), and αvβ5 (97), on the apical surface of RPE cells supports the function and longevity of photoreceptor neurons. Animals lacking expression of αvβ5 were found to accumulate lipofuscin, which is typically characteristic of age-related macular degeneration (97). Analogously, ablation of Mertk function in mice resulted in a retinal dystrophy phenotype similar to that originally described in rats (98). Progressive dysfunction of rod photoreceptors, followed by degeneration of cone photoreceptors and the retinal epithelium, are responsible for the development of retinitis pigmentosa, a heterogeneous group of genetic disorders resulting in the gradual loss of peripheral and eventually central vision. Multiple mutations in the Mertk gene have been identified in patients with severe retinitis pigmentosa, further validating the necessity of PtdSer-mediated phagocytosis for vision (99). In this and many other settings of homeostatic engulfment, the expression of different phagocytic receptors by the same cell population is necessary. It is not fully understood whether the receptors act in parallel, or cooperate by functioning at distinct steps in the engulfment process.

III. Hematopoietic System

Like T-cell development in the thymus, B-cell lymphopoiesis involves checkpoints to eliminate autoreactive clones by apoptosis. Defects in this system can contribute to the development of hematopoietic malignancies (100). More than 85% of newly generated immature B-cells are deleted, with B220+cells negative for surface IgM expression showing the highest incidence of apoptosis (101). B220+ cells expressing the typical markers of apoptosis have been observed in the cytoplasm of bone marrow resident macrophages in vivo (101, 102). Taking advantage of an in vitro co-culture system, multiple phagocytic receptors—CD14, SR-A, and various integrin receptors— were identified to contribute to apoptotic B-cell clearance, albeit with differing efficiency (103). Consequently, sensing of local cell death has the potential to directly regulate immune cell differentiation in the bone marrow.

Phagocytosis by macrophages also mediates two processes necessary for red blood cell (RBC) homeostasis and the maintenance of oxygen levels in an organism: the enucleation of erythroblasts during erythropoiesis (Figure 2C), and erythrocyte clearance at the end of their lifespan. At a late stage in their development, immature erythrocytes extrude their nuclei; given the high rate of production of RBCs, this generates a sizeable population of nuclear corpses with intact cellular membranes. In trying to determine how the nuclei are rapidly cleared, Yoshida and colleagues observed that nuclei expelled from murine splenic erythroblasts exposed PtdSer in culture, as indicated by binding of Annexin-V (104). Embryonic liver macrophages were capable of engulfing the extruded nuclei in vitro. These findings reflect one reason for the close association of developing erythrocytes to resident macrophages in the fetal liver (during late embryonic development) or the bone marrow (after birth) in vivo, which form structures deemed erythroblastic islands with immature RBCs surrounding a “central” macrophage (105). Similar to other systems discussed, this engulfment is enabled by multiple PtdSer-sensing receptors. Addition of MFG-E8 harboring a mutation (D89E) in its arginyl-glycyl-aspartic acid motif, the domain that facilitates its binding to phagocytes, to the co-culture system reduced the average number of nuclei engulfed per macrophage in a dose-dependent manner (104). Furthermore, macrophages from the splenic-derived erythroblastic islands from Mertk−/− mice exhibited diminished engulfment of expelled nuclei in comparison to WT (106). Mertk-transformed 3T3 cells were capable of taking up nuclei in the presence of exogenous PROS1, implicating the MERTK/PROS1 axis in erythroblast maturation in vitro (106). Therefore, although these extruded nuclei are not full cells per se, they undergo at least one change (PtdSer exposure) that mirrors apoptotic cell death and allows for their proper clearance by surrounding phagocytes. Whether distinct phagocytic receptors mediate this process during development or adulthood, and to what degree they can compensate for one another in vivo remains to be fully explored. Additionally, given the other significant interactions between “central” macrophages and erythroblasts [reviewed in (105)], it would be interesting to investigate whether engulfment of expelled nuclei affects the contribution of “central” macrophages to other steps of erythropoiesis in vivo.

After approximately 120 days in circulation, RBCs are removed by spleen and liver macrophages (107). As they age, erythrocytes not only increase their exposure of PtdSer, but also downregulate the “don’t eat me” signal CD47 (108), such that SIRPα-expressing macrophages can engulf the RBCs. This results in erythrocyte clearance from blood circulation (109). Intriguingly, CD47 expression on aged RBCs may also act as an “eat-me” signal. In an in vitro experiment, a CHO cell line transfected with SIRPα was incubated with a peptide derived from Thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1, 4N1K) and either oxidized erythrocytes or oxidized CD47-coated beads— in both cases, binding of the CD47+ cargo to the CHO cells was observed (110). Oxidation of erythrocytes has been shown to cause a conformational change in CD47, which leads to its binding to TSP-1 (110). Accordingly, binding of the CD47+ cargo in this way was detected exclusively when the beads or erythrocytes were oxidized, and then co-cultured with a SIRPα+ cell line in the presence of 4N1K. Therefore, recognition of both traditional and non-traditional “eat-me” signals may contribute to clearance of aged RBCs.

IV. Central Nervous System

Even though the magnitude of homeostatic neuron death in the developed brain is minimal in comparison to the other physiological systems reviewed here, neurogenesis in rodents during adulthood remains an important source of new neurons for memory formation, learning, and olfaction (111). After embryonic development, neurogenesis in rodents is restricted primarily to the subventricular zone (SVZ), from which developing neurons migrate to the olfactory bulb and serve as interneurons. Adult neurogenesis is also detected in the dentate gyrus (DG) in the hippocampus. Although more controversial in humans, a recent study utilizing 14C levels to determine neuron age in postmortem hippocampi revealed that neurogenesis does occur in the human DG, with an average of 700 new hippocampal neurons integrating per day (112, 113).

As in development, neurogenesis in these regions is accompanied by substantial cell death (114–116). Phagocytosis, by microglia as well as non-microglial cells, has been experimentally linked with adult neurogenesis (Figure 2D). Blockade of PtdSer-dependent phagocytosis, either through i.v. administration of Annexin-V or global ablation of Elmo-1, reduced neuronal differentiation in both neurogenic regions (117). The combination of both approaches exacerbated the phenotype, with Annexin-V-treated Elmo-1−/− mice amassing greater numbers of TUNEL+ cells in the hippocampus than their vehicle-treated counterparts. Consequently, neurogenesis during adulthood may require sufficient clearance of PtdSer+ dying neurons, mediated both by BAI-1/ELMO-1 and additional phagocytic pathways. Lu and colleagues also established that clearance of these developing neurons was not solely a feature of glial cells— DCX+ neuronal precursors/neuroblasts themselves were also capable of engulfing PtdSer-containing liposomes or irradiated neuronal precursors/neuroblasts injected directly into the DG or SVZ in vivo (117). Mice lacking other phagocytic receptors, such as TAM TKO mice, also displayed a defect in neurogenesis in the DG, with around 60% fewer BrdU+DCX+ neuronal precursors/neuroblasts than in WT DG (118). However, crossing of Axl−/− Mertk−/− to Interleukin-6−/− mice restored BrdU+DCX+ neuronal precursors/neuroblasts numbers closer to those of the WT, indicating that a constant low level of inflammation in the TAM KO mice may be what is harmful to neuronal differentiation, rather than an impaired phagocytic process. These data suggest that TAM activity prevents the production of pro-inflammatory and neurotoxic mediators like IL-6 in the hippocampus at baseline (118). In contrast, a distinct relationship between the TAM receptor MERTK and adult neurogenesis has been observed in the SVZ. Here, global or microglial-specific deletion of Mertk again resulted in accumulated cleaved-caspase-3+ cells under homeostatic conditions, but the number of BrdU+ labeled neurons in the olfactory bulb was enhanced (119). These results suggest that MERTK-mediated phagocytosis removed viable neuroblasts/immature neurons that retain the capability to form mature neurons. This process, now referred to as phagoptosis (120), may relate to earlier observations that cell survival is enhanced in C. elegans in the absence of components of the engulfment pathway (121, 122).

The precise mechanism(s) by which the aforementioned cell populations are replaced following massive, but scheduled, apoptotic cell death remains a critical gap in our understanding of homeostasis in these systems. The discussed experimental findings raise questions about whether intrinsic factors from apoptotic cells inform phagocytes of their cellular identity in order to permit more targeted proliferation signals. While in some cases in situ proliferation can restore the locally dying cells, in others this demand must be transmitted back to precursor populations, like for the renewal of circulating neutrophils. Further investigation is also needed to understand whether phagocytes are requisite interpreters of this cellular turnover and transducers of replenishment signals under physiological conditions. A significant challenge in addressing this point in vivo is decoupling the effects of diminished apoptotic cell sensing and uptake from the resultant accumulation of un-engulfed dying cells. If the sensing of apoptotic factors is not directly linked to compensatory proliferation, it is interesting to consider other signals that may initiate this regulatory circuit in neighboring cells, such as changes in population density. As mentioned before, loss of polarity or cellular junctions in dying cells can modulate intracellular signaling cascades, like the repression of the Hippo pathway, which then promote mitogen or growth factor release (123).

The immunosuppressive influence of apoptotic cells

Tissue damage during the course of infection or sterile injury is accompanied by a significant increase in cell death overall, including cell death by apoptosis. These include damaged stromal cells, which are the initial target of many insults, and infiltrating and resident immune cells, which undergo cell death after exerting their functions in pathogen clearance and/or tissue healing. The absence of an inflammatory response to damage had long been attributed to the high efficiency of phagocytic cells; by rapidly and dynamically adapting to the new microenvironment, phagocytes efficiently engulf dying cells before they undergo secondary necrosis, preventing the release of their immunogenic content. However, with a deeper understanding of the interaction between phagocytic and apoptotic cells, the uptake of apoptotic cells started to be considered an indispensable mechanism for the active, negative regulation of the inflammatory response (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Unscheduled apoptotic cell death promotes distinct anti-inflammatory and tissue repair programs in macrophages.

(A) Macrophages sense homeostatic turnover of apoptotic neutrophils, remove the corpses to avoid secondary necrosis, and respond by initiating replenishment of these cells. (B) In the context of an infection or injury, pathogen- or damage-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs, DAMPs) induce a pro-inflammatory response by macrophages. Additional recognition of apoptotic cells has an immunosuppressive effect, and contemporaneously promotes an anti-inflammatory program. (C) In contrast, engulfment of apoptotic cells in the presence of IL-4/IL-13 results in a distinct tissue repair response, including the potentiation of Retnla and Chil3 expression.

Meagher and colleagues’ observation in 1992 that the addition of apoptotic neutrophils to human macrophage cultures reduced the release of pro-inflammatory mediators N-acetyl-beta-D-glucosaminidase (NAG) and thromboxane A2 (TXA2) first revealed this additional immunomodulatory role for phagocytosis (124). Interestingly, the inflammatory response was not dampened when macrophages were incubated with either opsonized zymosan or IgG-coated erythrocytes. Subsequent independent studies treating LPS- or zymosan-stimulated macrophages with distinct apoptotic cargo led to enhanced production of anti-inflammatory molecules, like TGF-β1 and PGE-2, coupled with lowered secretion of pro-inflammatory factors, including TNF-α, IL-1β, and GM-CSF (125–127). This altered cytokine expression was conserved in both murine and human phagocytes, and found to be dependent on the phagocytic thrombospondin receptor CD36 in mice (126). Collectively, these initial studies established that the clearance of apoptotic cells actively suppresses the inflammatory response by macrophages.

A more complete picture of how the clearance of apoptotic cells leads to an anti-inflammatory program has been obtained by analyzing the accumulation of apoptotic cell metabolites within the phagocytic macrophages. Buildup of cholesterol is sensed by the LXR signaling pathway, which in turn promotes IL-10 and TGF-β1 secretion, while suppressing pro-inflammatory mediators like IL-1β and MCP-1 (128). Comparing the engulfment of apoptotic cargo with and without intracellular sterols illustrated that LXR activation significantly increases the transcription of Mertk in phagocytes (128). Similarly, uptake of apoptotic cells by macrophages induces the expression PPAR-δ, a nuclear receptor for fatty acids (129). Upon stimulation with LPS and apoptotic cells, WT macrophages, but not their Ppard−/− counterparts, exhibited increased IL-10 secretion and suppressed IL-12p40 and TNF-α release (129). In a PPAR-δ-dependent manner, apoptotic cell uptake also led to augmented expression of components involved in the recognition of apoptotic cells like Mertk and Mfge8 (129). These data and others (130–133) helped to consolidate the idea that the sensing of apoptotic cells by macrophages leads to the suppression of inflammatory cytokine release and a switch towards an anti-inflammatory milieu. Whether this suppressive effect was driven by the engagement of individual phagocytic receptors on the macrophage, or by multiple of these detectors, remains unknown.

That apoptotic cell recognition is part of the regulatory machinery of the inflammatory response suggests that defects in either the uptake of or response to apoptotic cells by phagocytes may contribute to acute and chronic pathologies (127). In chronic granulomatous disease, reduced exposure of PtdSer in apoptotic neutrophils, and the resulting decrease in their recognition and clearance by macrophages, contributes to the exacerbated inflammatory response (134). In the case of systemic lupus erythematous, anti-phospholipid antibodies opsonize apoptotic cells and potentially shift their mode of uptake to Fc-mediated phagocytosis, triggering the release of TNF-α which exacerbates pathology (135).

In addition to directing the inflammatory response by phagocytes, apoptotic cells themselves possess immunomodulatory properties that help maintain an anti-inflammatory milieu. During apoptosis specifically, caspase activation leads to the induction of reactive oxygen species by mitochondria, which oxidize and neutralize the danger signal high-mobility group box-1 protein (HMGB1) (136). Caspase activation also inactivates mitochondrial DNA-induced type I interferon (IFN) secretion, again curtailing the immune response (137). These mechanisms strongly contribute to “disarming” apoptotic cells. Along these lines, apoptotic thymocytes stimulated with anti-FAS or anti-CD3 antibodies have been shown to lose their mitochondrial membrane potential, relocate their TGF-β within the cytosol, and subsequently release it in both the latent and active forms (138). IL-10 is also induced in human apoptotic lymphocytes upon UV-irradiation (139), as well as in mouse splenic lymphocytes and T-cell hybridomas stimulated with FAS ligand (140). Apoptotic tumor cells have similarly been found to shape macrophage function through the release of S1P. Co-culture of human macrophages with an apoptotic human breast carcinoma cell line that produces S1P led to increased production of cytokines such as IL-10 and IL-8 by macrophages and reduced secretion of TNF-α and IL-12p70 (141). These data underscore that apoptotic cells themselves, through release of anti-inflammatory molecules, can also shape the anti-inflammatory response by macrophages and thus contribute to the induction of an immunosuppressive environment.

Integration of apoptotic cell and cytokine sensing: an emerging mechanism for the induction of tissue remodeling

The interaction between apoptotic cells and phagocytes following damage is a critical event for the induction of tissue remodeling. Anti-inflammatory molecules TGF-β1 and IL-10, which as discussed are abundantly released upon apoptotic cell/macrophage interaction, have been extensively reported to drive an anti-inflammatory phenotype in macrophages. Furthermore, production of growth factors like vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) by professional and non-professional murine phagocytes helps facilitate the proliferation of epithelial cells and subsequent restoration of epithelial integrity in tissues like the lung (142, 143). In Hydra, the potential for regeneration following injury is even more striking. Signals propagated from apoptotic regions in Hydra are essential for proliferation and initiation of a regeneration program in the head following bisection (144). Cells undergoing apoptosis were found to express Wnt3, a direct initiator of the regenerative response. Treatment of Hydra with the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK blocked both the amputation induced-apoptosis and the regeneration. In this context, exogenously administrated WNT3 was able to rescue the regeneration process. Interestingly, Z-VAD-FMK treatment also inhibited the formation of a proliferative zone adjacent to the apoptotic area, which in the control counterpart resembled those in the imaginal wing disc of Drosophila (144).

However, apoptosis and efferocytosis also occur continually at homeostasis without the induction of tissue remodeling. In fact, the aberrant production of reparative factors at baseline could be both detrimental and energetically costly. How then does the sensing of apoptotic cells by macrophages trigger maintenance of tissue integrity in physiological settings, and a tissue-remodeling response under pathological conditions? Which signals commit phagocytic macrophages toward a specific expression profile, or instruct them in a specific function? Are the interactions between apoptotic cells and macrophages somehow different during homeostasis and tissue damage? While parts of these questions remain to be answered, our group recently described a common cellular mechanism that may clarify some of these points. We showed that apoptotic cells generated from tissue damage integrate with other local signals to markedly enhance the capacity of macrophages to induce tissue remodeling (Figure 3C).

The Type 2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 have been previously described to orchestrate the induction of a distinct tissue remodeling phenotype in macrophages (145). Stromal cells from the skin, the intestine, and the lung are not only physical barriers to pathogens; they can also secrete several cytokines in response to stimuli (146). Resident and infiltrating inflammatory cells further contribute to this cytokine milieu upon injury. Accordingly, we examined IL-4/IL-13-mediated macrophage activation in the context of apoptotic cells, so as to model the contemporaneous exposure of macrophages to these two types of signals during tissue damage.

We identified a coincidence detection mechanism comprising of IL-4Rα and the phagocytic RTKs AXL and MERTK that was required to launch the tissue repair response in macrophages. The induction of IL-4/IL-13-mediated tissue repair was substantially abrogated when sensing of apoptotic cells by the macrophages was impaired, either by genetic ablation of Axl and Mertk or by the administration of Annexin-V, which masks the exposed PtdSer on apoptotic cells (147). The observation that apoptotic cells are constantly present in normal culture conditions demonstrated that the expression of tissue repair genes previously ascribed to IL-4/IL-13 alone in vitro actually requires these two types of signals. Importantly, this mechanism was also necessary for efficient repair in diverse tissue compartments following damage and a surge in apoptotic cells. Macrophages in the lung and adipose tissue of Axl−/− Mertk−/− mice infected with the parasite Nippostrongylus brasiliensis, which triggers the release of large amounts of Type 2 cytokines (148), were unable to acquire the same tissue remodeling phenotype as macrophages in infected WT mice. Similarly, injection of exogenous IL-4 after DSS or thioglycollate administration drove efficient tissue repair responses in the intestine and peritoneum respectively, in a manner dependent on the sensing of apoptotic cells.

These findings could help to explain previous reports that macrophages deficient for other phagocytic receptors did not upregulate a tissue repair program in response to stimulation with IL-4. For example, simultaneous absence of Mertk and Mfge8 on macrophages affected their capacity to acquire an anti-inflammatory phenotype and release VEGF upon IL-4 sensing (149). This impairment was particularly important in the infarcted heart, where clearance of injured cardiomyocytes by macrophages promotes the release of VEGF-A and the ensuing healing of the damaged heart (149). Similarly, the phagocytic receptor CD300f was observed to physically associate with IL-4Rα, and regulate macrophages response to IL-4 and IL-13 by modulating their capacity to acquire an anti-inflammatory signature (150). CD300f expression also controlled the aeroallergen-induced IL-4 mediated response in vivo (150).

Overall, these results raise several key points not yet explored. Further studies will need to dissect (i) how the apoptotic cell/type 2 cytokine-signaling crosstalk occurs; (ii) whether integration of the two signals is a specific characteristic of the detectors AXL and MERTK, or a broader signature of all PtdSer-sensing phagocytic receptors; (iii) whether the cross-communication between cytokine receptors and PtdSer phagocytic receptors also occurs in non-professional phagocytic cells; and (iv) whether sensing of apoptotic cells regulates the cellular response of macrophages to other cytokines, such as TNFα, IL-1β, and IFNγ. This newly elucidated relationship between apoptotic cells, cytokines, and phagocytes represents a novel and critical challenge for apoptotic cell- and cytokine-based therapies aimed at promoting resolution of inflammation and tissue remodeling.

Restoring life with cell death: the therapeutic potential of apoptotic cells

Due to its varied roles in regulating clearance, proliferation, inflammation, and tissue repair, the phagocytic/apoptotic cell axis presents an appealing target for manipulating the immune response. Pharmacological agents have already been developed to increase the phagocytic activity of macrophages and tip the system towards enhanced clearance. For instance, many malignant cells have been found to display CD47 on their surface, allowing them to avoid SIRPα-mediated uptake by phagocytes (151). Neutralization of this CD47 with a monoclonal antibody inhibited tumor growth in xenograft models of hematological cancers (such as AML (152), ALL (153), and multiple myeloma (154)), as well as solid tumors (including breast (151), leiomyosarcoma (155), small-cell lung cancer (156), and pediatric brain tumors (157)). In addition to promoting engulfment selectively of tumor cells by macrophages, CD47 blockade also has been shown to elicit tumor cell uptake and antigen presentation by SIRPα+ dendritic cells, engaging the T-cell response (158). With Hu5F9-G4, a humanized anti-CD47 antibody, entering Phase I clinical trials, modulating clearance shows promise as a therapeutic strategy for a range of malignancies (159).

Based on their immunomodulatory properties, apoptotic cells themselves are also being considered as a clinical tool for controlling and preventing macrophage-induced inflammation. Several groups have tested the capacity of infused apoptotic cells to directly treat acute and chronic inflammation in mice in vivo, of which we review here just a subset. Henson and colleagues instilled apoptotic Jurkat T-cells into the peritoneum of mice previously injected with thioglycollate, as well as in the lung of mice stimulated endotracheally with LPS. The observed increase in bioactive TGF-β1 upon apoptotic cell injection likely resulted from the in vivo clearance of the apoptotic cargo, since apoptotic Jurkat T-cells neither contain nor produce detectable TGF-β1 (160). This process was dependent on PtdSer recognition (160). The feasibility of apoptotic cell infusion as a cellular therapy has since been validated in several settings of acute and chronic damage. In a model of DSS-induced colitis, a single dose of apoptotic cells protected mice from the disease, by inhibiting both inflammasome- and NF-κB-dependent inflammation (161). Injection of apoptotic cells also protected mice from endotoxic shock by reducing the infiltration of cells into target organs and by limiting the secretion of TNF-α, IL-6, and IFNγ (162). A single administration of apoptotic cells in the lungs of bleomycin-treated mice was also found to increase PPAR-γ activity and the expression of PPAR-γ targets that enhance the phagocytic and anti-inflammatory capacity of alveolar macrophages, such as CD36, CD206 and arginase 1. This led to PPAR-γ-dependent upregulation of TGF-β, IL-10 and HGF secretion, which facilitated the resolution of inflammation in the lung (163).

The induction of TGF-β upon apoptotic cell infusion and phagocytosis also has important effects on T-cell activation and differentiation. Injection of apoptotic cells into the spleen resulted in the expansion of the regulatory T-cell population, which in turn protected against the development of murine graft-versus-host disease (GvHD). In this setting, neutralization of TGF-β stymied the apoptotic cell-induced regulatory T-cell expansion (164). This expansion was also one of the distinctive features observed when exogenous apoptotic thymocytes were administered in a streptococcal cell wall (SCW)-induced arthritis model. Similar to rheumatoid arthritis, SCW-induced arthritis is normally characterized by a lack of apoptosis leading to hyperplasia of the synovial lining. Here, infusion of apoptotic thymocytes substantially decreased joint swelling and destruction compared to control-treated animals (165). Similarly, instilment of apoptotic cells in NOD mice induced both Th2 responses and IL-10-producing regulatory cells, thereby delaying the onset of diabetes (166).

Although significant work remains to be done to translate these experimental findings to the clinic, extracorporeal photopheresis (ECP) therapy has already been successfully implemented for the treatment of acute rejection following organ transplantation. As part of this approach, primary PBMCs are isolated from the patient and then induced to undergo apoptosis with the addition of a photosensitive drug that crosslinks DNA. After UV exposure, the now apoptotic PBMCs are re-infused into the patient. This strategy has proven effective at generating an anti-inflammatory environment that facilitates acceptance of bone marrow, liver, lung, kidney, and pancreas transplantations (167). Additionally, ECP alone and in combination with other treatments was found to treat cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (168).

While the effects of ECP on macrophages have not yet been fully described, injected ECP-treated cells have been observed to localize to the liver and spleen (169), tissues easily accessible by phagocytes. An increased percentage of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T-cells has also been documented in patients treated with ECP to protect against GvHD following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantations (170). It is therefore tempting to speculate that that apoptotic cells themselves, or ingestion of apoptotic cells by phagocytic macrophages, could be essential elements for the clinical success of ECP.

Taken together, these studies suggest that the delivery of apoptotic cells in vivo could be a multi-pronged approach for ameliorating a range of diseases. This cellular therapy notably takes advantage of both the immunosuppressive capacity of apoptotic cells themselves, and their regulation of the polarization and inflammatory signature of phagocytic cells. Additional studies must be performed to understand the minimum apoptotic cell components necessary for the induction of an immunosuppressive/anti-inflammatory environment, and whether specific types or apoptotic cells or signals are required. Furthermore, testing whether PtdSer liposomes provide the same therapeutic benefits as apoptotic cells in different settings may provide further insight into the pathogenesis of specific inflammatory diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH-NIAID R01 AI089824 to C.V.R., NIH-NCI R01 CA212376 to C.V.R. and S.G), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Grant SFB841 to L.B.), Alliance for Lupus Research (Grant 332789 to C.V.R.), the Yale Immunobiology Department (NIH-NIAID T32 AI007019 to L.D.H.), and the National Science Foundation (DGE-1122492 to L.D.H.). C.V.R. is a HHMI Faculty Scholar. The authors thank Macy Akalu for her critical reading of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

None to disclose.

References

- 1.Muller WE, Muller IM. Origin of the metazoan immune system: identification of the molecules and their functions in sponges. Integr Comp Biol. 2003;43:281–292. doi: 10.1093/icb/43.2.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green DR. Cell death and the immune system: getting to how and why. Immunol Rev. 2017;277:4–8. doi: 10.1111/imr.12553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Abrams JM, et al. Molecular definitions of cell death subroutines: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2012. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:107–120. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor RC, Cullen SP, Martin SJ. Apoptosis: controlled demolition at the cellular level. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:231–241. doi: 10.1038/nrm2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saunders JW., Jr Death in embryonic systems. Science. 1966;154:604–612. doi: 10.1126/science.154.3749.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vogt C. In: Untersuchungen uber die Entwicklungsgeschichte der Geburtshelferkrote (Alytes obstetricians) Gassman JU, editor. 1842. p. 130. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klion FM, Schaffner F. The ultrastructure of acidophilic "Councilman-like" bodies in the liver. Am J Pathol. 1966;48:755–767. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farbman AI. Electron microscope study of palate fusion in mouse embryos. Dev Biol. 1968;18:93–116. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(68)90038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerr JF. Shrinkage necrosis: a distinct mode of cellular death. J Pathol. 1971;105:13–20. doi: 10.1002/path.1711050103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Child PL, Ruiz A. Acidophilic bodies. Their chemical and physical nature in patients with Bolivian hemorrhagic fever. Arch Pathol. 1968;85:45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kerr JF, Wyllie AH, Currie AR. Apoptosis: a basic biological phenomenon with wide-ranging implications in tissue kinetics. Br J Cancer. 1972;26:239–257. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1972.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wyllie AH. Apoptosis: cell death in tissue regulation. J Pathol. 1987;153:313–316. doi: 10.1002/path.1711530404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morris RG, Hargreaves AD, Duvall E, Wyllie AH. Hormone-induced cell death. 2. Surface changes in thymocytes undergoing apoptosis. Am J Pathol. 1984;115:426–436. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wyllie AH, Morris RG, Smith AL, Dunlop D. Chromatin cleavage in apoptosis: association with condensed chromatin morphology and dependence on macromolecular synthesis. J Pathol. 1984;142:67–77. doi: 10.1002/path.1711420112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wyllie AH, Arends MJ, Morris RG, Walker SW, Evan G. The apoptosis endonuclease and its regulation. Semin Immunol. 1992;4:389–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wyllie AH. Glucocorticoid-induced thymocyte apoptosis is associated with endogenous endonuclease activation. Nature. 1980;284:555–556. doi: 10.1038/284555a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Creagh EM, Conroy H, Martin SJ. Caspase-activation pathways in apoptosis and immunity. Immunol Rev. 2003;193:10–21. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thornberry NA, Rano TA, Peterson EP, et al. A combinatorial approach defines specificities of members of the caspase family and granzyme B. Functional relationships established for key mediators of apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17907–17911. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.29.17907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Earnshaw WC, Martins LM, Kaufmann SH. Mammalian caspases: structure, activation, substrates, and functions during apoptosis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:383–424. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Segawa K, Kurata S, Yanagihashi Y, et al. Caspase-mediated cleavage of phospholipid flippase for apoptotic phosphatidylserine exposure. Science. 2014;344:1164–1168. doi: 10.1126/science.1252809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuida K, Zheng TS, Na S, et al. Decreased apoptosis in the brain and premature lethality in CPP32-deficient mice. Nature. 1996;384:368–372. doi: 10.1038/384368a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woo M, Hakem R, Soengas MS, et al. Essential contribution of caspase 3/CPP32 to apoptosis and its associated nuclear changes. Genes Dev. 1998;12:806–819. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.6.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuida K, Haydar TF, Kuan CY, et al. Reduced apoptosis and cytochrome c-mediated caspase activation in mice lacking caspase 9. Cell. 1998;94:325–337. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81476-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hakem R, Hakem A, Duncan GS, et al. Differential requirement for caspase 9 in apoptotic pathways in vivo. Cell. 1998;94:339–352. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81477-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cowan WM, Fawcett JW, O'Leary DD, Stanfield BB. Regressive events in neurogenesis. Science. 1984;225:1258–1265. doi: 10.1126/science.6474175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cecconi F, Alvarez-Bolado G, Meyer BI, Roth KA, Gruss P. Apaf1 (CED-4 homolog) regulates programmed cell death in mammalian development. Cell. 1998;94:727–737. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81732-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoshida H, Kong YY, Yoshida R, et al. Apaf1 is required for mitochondrial pathways of apoptosis and brain development. Cell. 1998;94:739–750. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81733-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martinou JC, Dubois-Dauphin M, Staple JK, et al. Overexpression of BCL-2 in transgenic mice protects neurons from naturally occurring cell death and experimental ischemia. Neuron. 1994;13:1017–1030. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90266-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zou H, Niswander L. Requirement for BMP signaling in interdigital apoptosis and scale formation. Science. 1996;272:738–741. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5262.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yokouchi Y, Sakiyama J, Kameda T, et al. BMP-2/-4 mediate programmed cell death in chicken limb buds. Development. 1996;122:3725–3734. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.3725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guha U, Gomes WA, Kobayashi T, Pestell RG, Kessler JA. In vivo evidence that BMP signaling is necessary for apoptosis in the mouse limb. Dev Biol. 2002;249:108–120. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bandyopadhyay A, Tsuji K, Cox K, et al. Genetic analysis of the roles of BMP2, BMP4, and BMP7 in limb patterning and skeletogenesis. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ganan Y, Macias D, Basco RD, Merino R, Hurle JM. Morphological diversity of the avian foot is related with the pattern of msx gene expression in the developing autopod. Dev Biol. 1998;196:33–41. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bakrania P, Efthymiou M, Klein JC, et al. Mutations in BMP4 cause eye, brain, and digit developmental anomalies: overlap between the BMP4 and hedgehog signaling pathways. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:304–319. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haas A. The phagosome: compartment with a license to kill. Traffic. 2007;8:311–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swanson JA. Shaping cups into phagosomes and macropinosomes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:639–649. doi: 10.1038/nrm2447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoffmann PR, deCathelineau AM, Ogden CA, et al. Phosphatidylserine (PS) induces PS receptor-mediated macropinocytosis and promotes clearance of apoptotic cells. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:649–659. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.May RC, Machesky LM. Phagocytosis and the actin cytoskeleton. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:1061–1077. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.6.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yutin N, Wolf MY, Wolf YI, Koonin EV. The origins of phagocytosis and eukaryogenesis. Biol Direct. 2009;4:9. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-4-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Truman LA, Ford CA, Pasikowska M, et al. CX3CL1/fractalkine is released from apoptotic lymphocytes to stimulate macrophage chemotaxis. Blood. 2008;112:5026–5036. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-162404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elliott MR, Chekeni FB, Trampont PC, et al. Nucleotides released by apoptotic cells act as a find-me signal to promote phagocytic clearance. Nature. 2009;461:282–286. doi: 10.1038/nature08296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martin SJ, Reutelingsperger CP, McGahon AJ, et al. Early redistribution of plasma membrane phosphatidylserine is a general feature of apoptosis regardless of the initiating stimulus: inhibition by overexpression of Bcl-2 and Abl. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1545–1556. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fadok VA, Voelker DR, Campbell PA, et al. Exposure of phosphatidylserine on the surface of apoptotic lymphocytes triggers specific recognition and removal by macrophages. J Immunol. 1992;148:2207–2216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koopman G, Reutelingsperger CP, Kuijten GA, et al. Annexin V for flow cytometric detection of phosphatidylserine expression on B cells undergoing apoptosis. Blood. 1994;84:1415–1420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]