Summary

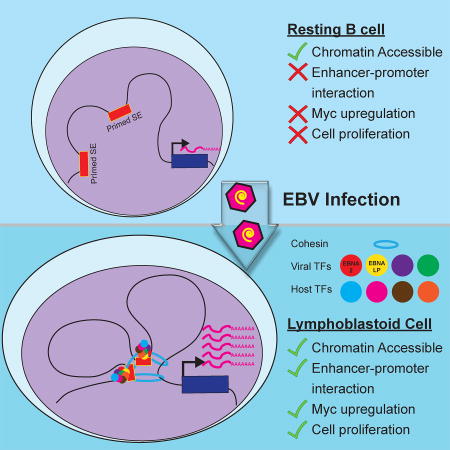

Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) transforms B cells to continuously proliferating lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs), which represent an experimental model for EBV-associated cancers. EBNAs and LMP1 are EBV transcriptional regulators that are essential for LCL establishment, proliferation, and survival. Starting with the 3D genome organization map of LCL, we constructed a comprehensive EBV regulome encompassing 1992 viral/cellular genes and enhancers. ~30% of genes essential for LCL growth were linked to EBV enhancers. Deleting EBNA2 sites significantly reduced their target gene expression. Additional EBV super-enhancer (ESE) targets included MCL1, IRF4, and EBF. MYC ESE looping to the transcriptional stat site of MYC was dependent on EBNAs. Deleting MYC ESEs greatly reduced MYC expression and LCL growth. EBNA3A/3C altered CDKN2A/B spatial organization to suppress senescence. EZH2 inhibition decreased the looping at the CDKN2A/B loci and reduced LCL growth. This study provides a comprehensive view of the spatial organization of chromatin during EBV-driven cellular transformation.

In Brief

Jiang et al. examine the 3-D chromatin landscape of Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) transformed B cells to build the EBV regulome. Viral EBNA and LMP proteins regulate host gene expression through long-range enhancer-promoter looping to activate key oncogenes and inactivate tumor suppressor genes in lymphoblastoid cells.

Introduction

~20% of human malignancies are caused by tumor viruses and other infectious agents (Howley, 2015). Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) is the first human tumor virus discovered in African Burkitt’s lymphoma samples (Epstein et al., 1964). EBV causes ~200,000 cases of different cancers annually (Cohen et al., 2011), including endemic Burkitt’s lymphoma, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Post-Transplantation Lymphoproliferative Disease (PTLD), AIDS associated lymphomas, nasopharyngeal carcinoma and ~10% of gastric cancers (Longnecker R, 2013). Various types of EBV latency programs are associated with different cancers. In EBV type III latency, six EBV Nuclear Antigens (EBNAs), three Latent Membrane Proteins (LMPs), EBV non-coding RNAs, and miRNAs are expressed. This type of latency is associated with most PTLDs and many AIDS lymphomas (Longnecker R, 2013).

In vitro, EBV transforms Resting B Lymphocytes (RBLs) to continuously proliferating Lymphoblastoid Cell Lines (LCLs) (Longnecker R, 2013). LCLs express type III latency genes and are an important model for studying EBV associated cancers. EBNA2, EBNA3A, EBNA3C, EBNALP and LMP1 are essential for LCL establishment, continuous proliferation, and survival. EBNAs are EBV transcription factors (TFs) that modulate expression of both viral and host genes, while LMP1 mimics a constitutively active CD40 to activate NF-κB (Longnecker R, 2013). EBV oncogenes and NF-κB subunits have independent roles in LCL growth and survival. EBNA2 and EBNALP are the first EBV genes expressed upon virus infection of RBLs (Alfieri et al., 1991). EBNA2 activates the expression of other virus latency genes and cell genes by binding predominately to enhancers through cell TFs including RBPJ (Grossman et al., 1994; Kaiser et al., 1999; Ling et al., 1993; Zhao et al., 2011). Most importantly, EBNA2 activates the MYC oncogene expression from distal enhancers hundreds of kilobases upstream of the MYC Transcription start site (TSS) (Wood et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2011). EBNA2 inactivation in LCLs, stops LCL growth and causes cell death (Kaiser et al., 1999; Kempkes et al., 1995). EBNALP binds preferentially to promoters than enhancers, and co-activates with EBNA2 by removing transcription repressors, including N-CoR, from EBNA2 (Harada and Kieff, 1997; Ling et al., 2005; Portal et al., 2011; Portal et al., 2013). EBNA3A and 3C can be tethered to DNA through cell TFs including IRF4 and BATF (Banerjee et al., 2013; Jiang et al., 2014; Schmidt et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015). EBNA3A and 3C repress both p14ARF and p16INK4A, thereby preventing cell senescence (Maruo et al., 2006; Skalska et al., 2010). siRNA knock down of both p14ARF and p16INK4A allows continuous LCL growth in the absence of EBNA3C or EBNA3A (Maruo et al., 2011). Genetic deletion of this locus allowed EBV to transform these cells in the absence of EBNA3C. EBNA3C recruits the transcription repressor Sin3A, WDR48, and CtBP to the (Jiang et al., 2014; Ohashi et al., 2015; Skalska et al., 2010)p14ARF promoter to repress their expression. EBNA3C also recruits polycomb repressive complex to this locus (Skalska et al., 2010). EBNA3A binds to sites >80kb away from this locus (Schmidt et al., 2015). NF-κB inactivation in LCLs effectively reduces LCL proliferation, causes cell death, and affects the expression of cells genes essential for growth and survival (Cahir-McFarland et al., 2000; Zhao et al., 2014). EBNA3A, 3C and all the NF-κB subunits also bind predominantly to enhancers, suggesting that enhancers are critically important for LCLs. However, little is known about what are regulated by EBV enhancers genome-wide.

All essential EBNAs and the NF-κB subunits converge to a small number of enhancer sites (Zhou et al., 2015). 187 have extraordinary high and broad H3K27ac signals, characteristic of super-enhancers that have critical roles in cell development and oncogenesis (Whyte et al., 2013). These enhancers are referred to as EBV super-enhancers (ESE). Many ESE associated genes, including MYC, are critical for LCL growth and survival (Faumont et al., 2009). Perturbation of ESEs by small molecule JQ1 that blocks Brd4 from binding to acetylated H3K27 histone tails, effectively arresting LCL growth and reducing MYC expression.

Enhancers up-regulate transcription independent of linear location, distance and orientation. Distant enhancers regulate transcription by looping to their direct target genes. The 3D genome spatial juxtaposition of enhancer and promoter DNA allows transcription machinery assembled on enhancers to contact basal transcription factors on promoters to enable higher order complexes formation and coordinately activate cell gene expression (Ong and Corces, 2011). Detailed functional studies of promoter-enhancer interactions were made possible by chromatin proximity ligation, and subsequent chromatin conformation capture (3C) assays (Dekker et al., 2002). High-throughput methods have emerged to study chromatin-interactions on a genome-wide basis (Lieberman-Aiden et al., 2009). Chromatin Interaction Analyses by Pair-end Tag sequencing (ChIA-PET) defines the 3D genome organization positioned by specific TFs (Tang et al., 2015). In ChIA-PET, Chromatin Immune Precipitation (ChIP) is first used to enrich the enhancer-enhancer, enhancer-promoter interactions mediated by specific TFs. Paired-end sequencing is then used to link the enhancers to their direct target genes.

In this study, we integrated recently published LCL RNA PoI II (RNAPII) ChIA-PET (Tang et al., 2015) and ChIP followed by deep-sequencing (ChIP-seq) data (Jiang et al., 2014; Portal et al., 2013; Schmidt et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2011) to generate an EBV regulome controlled by viral enhancers. These results provide insights into how EBV exploits the three-dimensional genome organization to generate its enhancer interaction network to drive proliferation and transformation.

Results

EBV regulome

EBV enhancers have very high ChIP-seq signals for H3K27ac and H3K4me1, indicative of high transcription activity. Strong RNAPII ChIP-seq signals are also evident at EBV enhancers and promoters in LCLs (Arvey et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2015). EBV enhancers can loop to their direct target genes to activate gene expression (Wood et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2011). At actively transcribed genes, RNAPII signals are very strong at promoters. High RNAPII signals are also evident at the gene body and 3’ region (Adelman and Lis, 2012). Formaldehyde crosslinking can preserve the enhancer-promoter, enhancer-enhancer interactions brought together by RNAPII. RNAPII ChIP assay enriched the protein-DNA complexes that contained RNAPII, enhancers, and promoters, or the gene body. The enhancers and promoters in the same complex can be ligated due to their physical proximity and analyzed by deep sequencing, thus linking enhancers to their direct target genes.

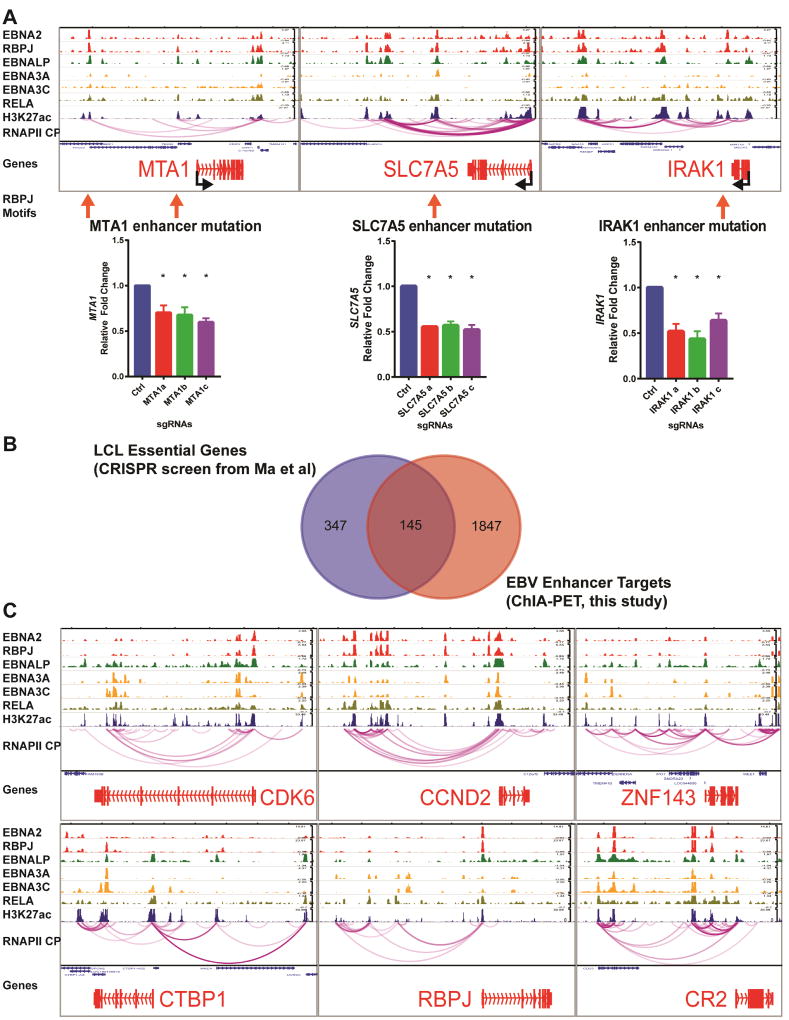

LCL RNAPII ChIA-PET linked enhancers occupied by any of the four EBNAs or five NF-κB subunits to 13216 genes (including promoters or gene body). Amongst these genes, 4074 expressed 2 fold higher in LCLs than RBLs by RNA-seq. 2223 of these 4074 EBV induced genes were expressed at high level with Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads (FKPM) >10. Furthermore, 1992 of the EBV enhancer linked genes have significant ChIP-seq signals for RNAPII with S5 phosphorylation at the RNAPII C-terminal Domain (CTD), indicative of active transcriptional initiation. These 1992 genes were therefore referred to as “the EBV regulome”. To test if the enhancers identified are important for the expression of their target genes linked by RNAPII ChIA-PET, CRISPR knock out was used. EBNA2 upregulates the expression of MTA1, IRAK1 and SLC7A5 in LCLs. RNAPII ChIA-PET identified their enhancers (Figure 1A). gRNAs were designed to target the well-defined RBPJ motifs where EBNA2 was tethered to enhancers. gRNAs were delivered into LCLs stably expressing Cas9 by lentiviruses. After puromycin selection, genomic DNA and total RNA were purified. qRT-PCR found significant reduction of gene expression following CRISPR knock out of RBPJ binding site. gRNA targeted regions were PCR amplified and sequenced. Sequencing results were analyzed by Tracking of Indels by Decomposition (TIDE) (Brinkman et al., 2014). CRISPR knock out successfully altered the RBPJ binding sites (Figure S1A,B,C). The data indicated that these EBNA2 enhancers were indeed important for the expression of their direct target genes.

Figure 1. RNAPII ChIA-PET linked EBV enhancers to their direct target genes.

(A) ChIA-PET links between EBV enhancers and known EBNA2 target genes MTA1, SLC7A5, and IRAK1 and effects of enhancer CRISPR knock out on their expression. ChIP-seq tracks for the indicated TFs were listed on top. In ChIA-PET tracks, each magenta line represented a pair of genomic interaction mediated by RNAPII. ChIA-PET linked genes were in red. gRNA targeted regions were indicated by arrows. LCLs stably expressing Cas9 were transduced with gRNA or control lentiviruses and selected with puromycin. Total RNAs were prepared from these cells and qRT-PCR was used to determine the expression level normalized against b-actin as loading control. The levels of control gRNA treated cells were set to 1. Error bars represented standard error. *p<0.05. (B) Intersection of genes essential for LCL growth and survival and EBV enhancer targeted genes. (C) ChIA-PET links between EBV enhancers and genes essential for LCL survival, CDK6, CCND2, ZNF143, CTBP, RBPJ and a well characterized EBNA2 target CR2. All data are represented as mean+/−SE. See also Figure S1 and Table S1 and S2.

Our LCL genome wide CRISPR drop out screen identified 492 genes essential for LCL growth and survival (p<0.05). Strikingly, ~30% (152) of these genes were linked to an EBV enhancer by RNAPII (Figure 1B), indicating that EBV usurps critical pathways to gain control of normal B cell program. For example, EBV enhancers were linked to CDK6, ZNF143, CTBP1, RBPJ, and CCND2 (Figure 1C). CDK6 TSS was linked to multiple EBV enhancers. Together with D-type cyclins, CDK6 phosphorylates pRB tumor suppressor to promoter cell cycle progression (Patnaik et al., 2016). Several CDK6 inhibitors are in clinical trials for various cancers and FDA has approved a CDK4/CDK6 inhibitor palbociclib for the treatment of breast cancer together with aromatase inhibitor (Sherr et al., 2016). Therefore, CDK6 inhibitors may also be useful in treatment of EBV associated cancers. 33% of ZNF143 binding sites overlap with EBNA2 (Zhao et al., 2011). ZNF143 is important for enhancer-promoter looping (Bailey et al., 2015). CTBP1 is a transcription repressor that bind to EBNA3A and 3C and important for suppression of p16INK4A (Hickabottom et al., 2002; Skalska et al., 2010). RBPJ tethers EBNA2 to DNA (Grossman et al., 1994; Henkel et al., 1994). EBNA3A and 3C binding to RBPJ is required for continuous LCL proliferation and EBNA3C can recruit RBPJ to DNA (Kalchschmidt et al., 2016; Maruo et al., 2005; Maruo et al., 2009). CCND2 is known to be up regulated by EBNA2 and LP (Sinclair et al., 1994). RNAPII ChIP-PET linked a cluster of CCND2 enhancers co-occupied by EBNA2 and LP, ~120 kb upstream of CCND2 to CCND2 TSS (Figure 1C). CR2 is a known EBV target. ChIA-PET linked EBV enhancer as far as 20kb away from CR2 TSS.

EBV regulome pathway analyses identified >270 pathways. The most significantly enriched pathways included ribosome, cell cycle, DNA replication, metabolism, EBV infection, and viral carcinogenesis (Table S1).

Genes linked via RNAPII to EBNA2, LP, 3A and 3C enhancers were also identified to generate the regulome for each individual EBV oncoprotein. EBNA2, LP, 3A, and 3C peaks were linked to 2102, 4895, 1981, and 2199 genes expressed at >10 FKPM in LCLs respectively. Pathway analyses found each EBV TF associated with unique but also overlapping cellular programs (Table S2).

ESE direct targets linked by RNAPII

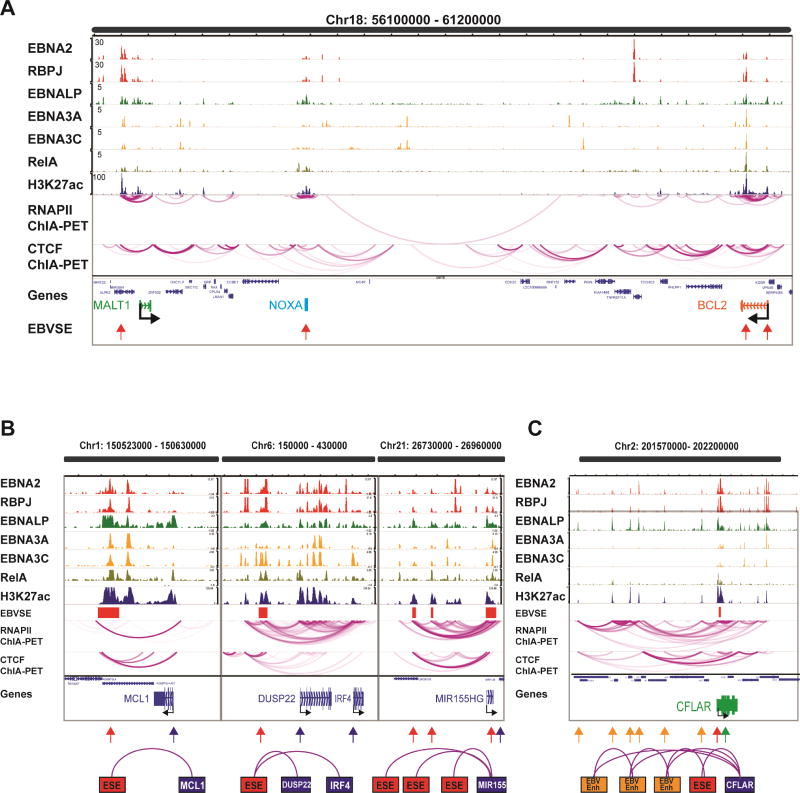

RNAPII ChIA-PET linked 187 ESEs to 544 direct target genes. The majority of previously assigned Hi-C enhancer-promoter interactions were consistent with LCL RNAPII ChIA-PET. For example, two ESEs near BCL2 and an ESE near PMAIP1 (NOXA) were linked to the BCL2 and PMAIP1 TSSs respectively, consistent with what was previously found (Zhou et al., 2015). Interestingly, another ESE originally assigned to ALPK2 by proximity was found mostly interact with MALT1 TSSs by ChIA-PET (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. RNAPII ChIA-PET linked ESEs to their direct targets.

(A) Snapshot of a 5 mb region on chromosome 18. ChIP-seq tracks for EBV TFs were shown on the top. H3K27ac track was shown in the middle followed by RNAPII and CTCF ChIA-PET. Genes in the loci was listed with MALT1, PMAIP1(NOXA), and BCL2 highlighted. Red arrows indicated ESEs at the loci. (B) Snapshots of genome browser with ChIP-seq tracks and ChIA-PET links and cartoons representing the complexities of EBV mediated enhancer-promoter interactions. Top, ChIP-seq tracks. Middle red boxes indicated ESEs. RNAPII and CTCF ChIA-PET links were below ESEs followed by gene positions. Left panel: 1 ESE regulating 1 gene. Middle Panel: 1 ESE regulating 2 genes. Right panel: 3 ESEs regulating 1 gene. In the cartoons, red arrows indicated ESEs and blue arrows indicated ESE associated genes. Magenta lines represented ChIA-PET links. (C) ESE and many other EBV enhancers were linked to CFLAR. Orange arrows indicated the EBV enhancers, red arrow indicated ESE and green arrow indicated CFLAR gene body. See also Figure S2 and Table S3.

The average distance between ESEs and their target genes was 438kb, with the most distant one at 9,800kb. Many ESEs had multiple target genes and many genes have multiple ESEs. Only 40 ESEs had one target gene while the ESE with most interactions was linked to 26 different genes. Of the total 544 ESE target genes, 63 were linked by multiple ESEs.

We previously assigned an ESE to ADAMTSL4, a gene neighboring MCL1. RNAPII ChIA-PET linked MCL1 to this ESE (Figure 2B, left). MCL1 is a BCL2 family member of anti-apoptotic mitochondrial proteins and is frequently amplified in cancer (Perciavalle et al., 2012). LMP1 activates MCL1 expression for LCL growth and survival (Wang et al., 1996). The IRF4 locus exemplifies the intrinsic interactions of a single ESE in controlling multiple genes: DUSP22 and IRF4 (Figure 2B, middle). IRF4 is essential for LCL growth and survival. IRF4 often dimerizing with other TFs such as BATF and SPI1 to activate AP1-IRF Composite Elements (AICEs) and ETS-IRF Composite Elements (EICEs) during B cell development (Ochiai et al., 2013). IRF4 is a major factor through which EBNA3A/C bind to DNA (Banerjee et al., 2013; Jiang et al., 2014; Schmidt et al., 2015). IRF4 is also likely important for NF-κB binding to genomic sites that lack classical NF-κB motifs (Zhao et al., 2014). Interestingly, both DUSP22 and IRF4 are also linked to an additional ESE near the DUSP22 promoter. IRF4 and DUSP22 gene expression are highly upregulated as RBLs are transformed by EBV (Figure S2A), providing key evidence in how this ESE has a major role in activating genes required for EBV driven proliferation. MIR155, an oncomir, was linked to 3 ESEs via RNAPII (Figure 2C, right). CFLAR is critical for LCL survival. CRISPR knock out of CFLAR greatly reduced LCL growth and induced apoptosis (Ma et al., 2017). CFLAR was linked to an ESE and multiple EBV enhancers (Figure 2C). Most RNAPII ChIA-PET linkages were intrachromosal (Tang et al., 2015). Interestingly, EBF1, a B cell pioneering TF on chromosome 5, was linked to ESEs on chromosomes 7, 16, 17 and 20 (Figure S2B). Pathway analyses of the ESE associated genes were enriched in immune related, signaling and pathways in cancer (Table S3).

1.6% of ESEs did not interact with any RefSeq annotated gene targets. GRO-seq finds abundant transcription at genomic sites targeted by these ESEs (Figure S2C). They are likely to be novel, unannotated non-coding RNAs.

EBV enhancers linking other enhancers

EBV Typical Enhancers (ETEs) are co-occupied by all the EBNAs and NF-κB subunits but have much less H3K27ac signals (Zhou et al., 2015). In contrast to 98.4% of ESEs linked to a gene, only 79.5% of ETEs were linked to a gene. Strikingly, the other EBV enhancers that don’t have all the nine factors were mostly linked to other enhancers, and only 24.3% were linked to a gene (Figure S2D). These results are consistent with ESEs as active chromatin hubs that control host genes essential for transformation. It is also possible that in order to effectively regulate gene expression, weaker enhancers had to be assembled into much larger enhancer complexes to exert their functions.

ESE associated genes expressed at higher level in LCLs than RBLs

ESE regulated genes were expressed at higher levels in transformed LCLs than RBLs (p< 0.008) (Figure S2E). This added functional relevance to the roles of ESEs in driving key genes involved in cancer cell identity in EBV transformed LCLs.

Functional roles of ESEs in their associated gene expression

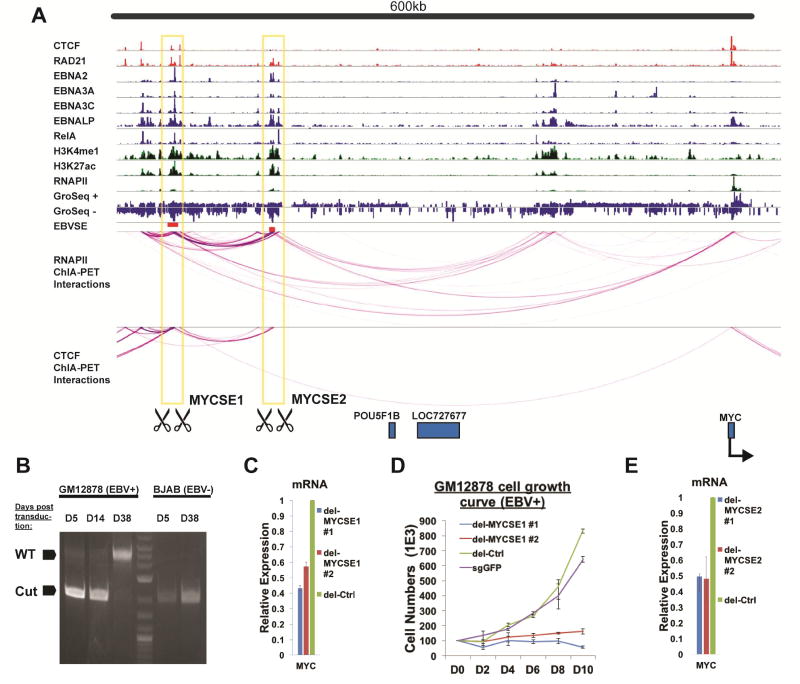

RNAPII ChIA-PET identified abundant linkages between the ESEs −525kb (MYCSE1), −428kb (MYCSE2) and MYC TSS (Figure 3A). ESEs were also linked to RUNX3 by RNAPII ChIA-PET (Figure S3A). To evaluate the functional roles of ESEs in gene expression, CRISPR/Cas9 was used to delete ESEs in LCLs.

Figure 3. MYC ESEs were essential for MYC expression and cell growth.

(A) RNAPII ChIA-PET linkages at the MYC locus. ChIP-seq tracks were shown on the top. MYCSE1 (-525kb from TSS) and MYCSE2 (-428kb from TSS) were indicated by red box below the tracks. RNAPII ChIA-PET links were shown by magenta lines. Orange boxes indicated the regions targeted by CRISPR. (B) Validation of MYCSE1 Deletion. Cas9 stable LCLs or BJAB were transduced with paired gRNA targeting the edges of ESE. After puromycin selection, genomic DNA was prepared from LCLs and BJAB cells transduced with dual gRNA. The targeted region was PCR amplified. The presence or absence of the MYC SE1 was shown. (C) MYCSE1 deletion reduced MYC mRNA level. 2 independent pairs of gRNAs both decreased MYC mRNA by qRT-PCR normalized to b-actin. Control gRNA treated cells were set to 1. (D) Growth of MYCSE1 deleted LCLs and LCLs with deletion in a control region. (E) MYCSE2 deletion also reduced MYC mRNA level. 2 independent pairs of gRNAs both decreased MYC mRNA by qRT-PCR. All data are represented as mean+/−SE. See also Figure S3.

LCLs stably expressing Cas9 were transduced with dual gRNA lentiviruses that simultaneously express pairs of gRNAs targeting a ~3kb region of MYCSE1, MYCSE2 and RUNX3 ESE (Figures 3A, S3A). Repair of the two CRISPR generated double stranded DNA breaks will result in the deletion of the genomic region flanked by the gRNA pairs. A pair of gRNAs targeting an ENCODE defined heterochromatin region 650 kb upstream of the MYC TSS, or a single gRNA against GFP were used as controls. For the MYCSE1, after puromycin selection, LCLs were seeded and the counted every 2–3 days. Total genomic DNA was analyzed for deletion by PCR. MYCSE1 was efficiently deleted 5 days after transduction (Figure 3B). Sequencing of the PCR product confirmed the targeted deletion of MYCSE1 (Figure S3B). While the MYCSE1 deletion could still be detected 14 days after transduction, the deletion was selected against after 38 days (Figure 3B). As a control, the same experiment was performed in BJAB cells, an EBV negative lymphoma cells that does not harbor the Ig/MYC translocation. 38 days after selection, the deletion was still evident (Figure 3B). These data suggested that MYCSE1 deletions were selected against in EBV transformed LCLs, but not in EBV negative lymphomas, providing evidence for the importance of a single cis-regulatory element in driving LCL growth. Two independent pairs of gRNAs targeting MYCSE1 reduced MYC expression by 40–60% compared to the control (Figure 3C). MYCSE1 CRISPR deletions also greatly reduced LCL cell growth rates (Figure 3D). Two independent pairs of gRNAs targeting MYCSE2 also resulted in drastic reduction of MYC expression (Figure 3E, S3C). RUNX3 ESE deletions also reduced RUNX3 expression accordingly (Figure S3D). These results demonstrated a striking phenotype in that excision of a single DNA regulatory region targeted by EBV was sufficient to cause LCL growth arrest.

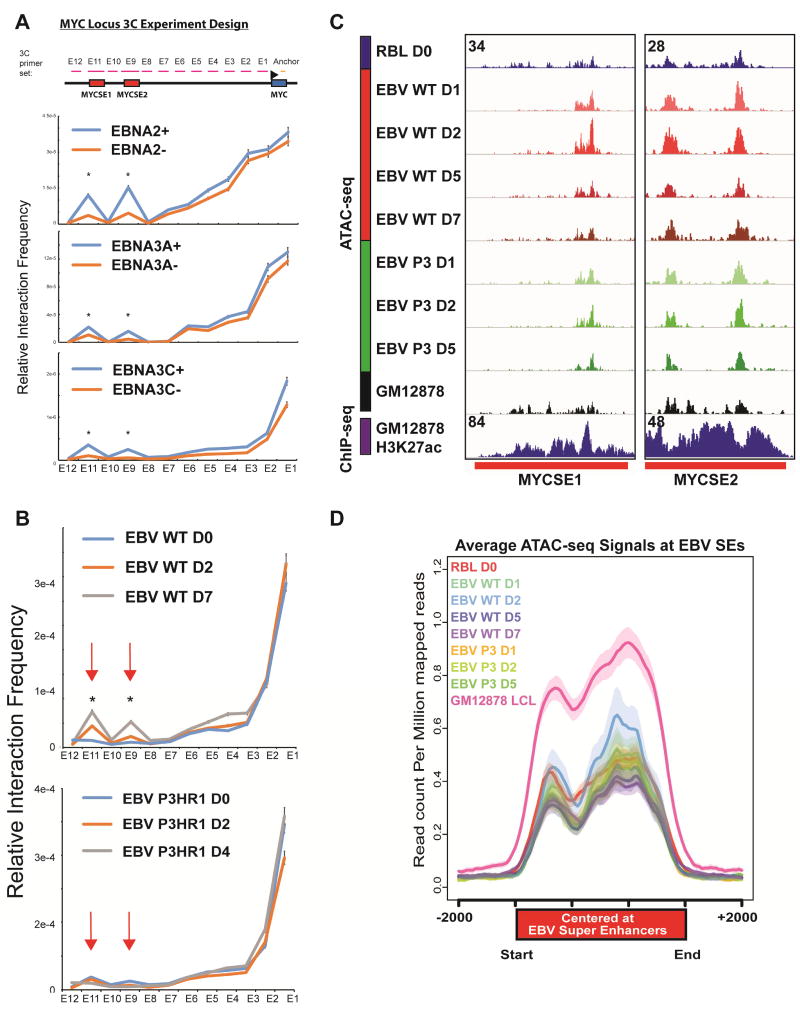

EBNAs and EBV infection induced chromatin conformation changes at the MYC locus

To further determine the molecular mechanisms through which MYC ESEs loop to MYC TSS, the effect of inactivation of conditional EBNA2, 3A, and 3C on MYC ESE looping was evaluated by 3C-qPCR. A set of primers spanning the MYCSE1, MYCSE2, and the rest of MYC locus (total ~600kb in size) with an anchor primer near MYC TSS was used to quantitate the interaction frequencies (Figure 4A, top). The efficiencies of primer pairs were normalized using BAC DNA. The interaction frequencies between MYC TSS (anchor) and the upstream genomic regions were high when the genomic regions were immediately adjacent to the anchor (Figure 4A). The interaction frequencies reduced to the background level when the genomic region moved further away from MYC TSS. The interaction frequencies increased again when primers were within the ESE regions (Figure 4A). Conditional inactivation of EBNA2, 3A, and 3C significantly reduced MYC ESEs looping to MYC TSS (Figure 4A). These data indicated that in addition to EBNA2, EBNA3A and 3C were also important for ESEs looping to MYC TSS.

Figure 4. EBNA2, EBNA3A, and EBNA3C were essential for MYC ESEs looping to MYC TSS.

(A) qPCR primers spanning the MYC locus including the MYCSE1 and MYCSE2 enhancers for 3C were indicated on the top. The anchor primer was near MYC TSS. LCLs conditional for EBNA2, EBNA3A and EBNA3C were grown under conditions permissive or non-permissive for their expression. Cells were fixed with formaldehyde and lyzed. Chromatin was digested with EcoRI, diluted, and ligated. After reverse crosslinking, DNA was purified. qPCR was used to determine the interaction frequency. The amount of DNA used in qPCR was normalized with GAPDH and the qPCR primer efficiencies were normalized using ligated DNA from BAC clones covering the entire genomic region. EBNA2, EBNA3A, and EBNA3C inactivation significantly decreased MYC ESEs looping to MYC TSS (*p<0.05). Data are represented as mean+/−SE. (B) RBLs were infected with wild type B958 or EBNA2 deletion mutant P3HR1 EBV for the time indicated. 3C-qPCR indicated that wild type EBV induced MYC ESEs looping to MYC TSS as early as two days post infection and continued to increase at day 7. However, EBV mutant delete for EBNA2 and the EBNALP Y1Y2 exons failed to induce the looping. Data are represented as mean+/−SE. (C) ATAC-seq signals at the MYC ESEs. RBLs were infected with wild type or P3HR1 mutant EBV for the indicated time. Nuclei were first prepared and mixed with transposase reaction. The DNA was then purified and PCR amplified. Deep sequencing was used to determine the accessibility of the MYC ESE regions. Published GM12878 LCLs ATAC-seq were also included. (D) ATAC-seq signals at ESEs and the neighboring +/− 2kb windows during the RBL infection time course experiment. LCL signals were indicated. See also Figure S4.

To evaluate the looping function of EBNA2 and EBNALP in context of viral infection, a time course study of wild type B958 EBV and mutant EBV P3HR1 infection of RBLs was done. P3HR1 virus lacks EBNA2 and the unique EBNALP Y1Y2 exons, hence it does not immortalize RBLs. The viral titers were determined by EBNALP immune fluorescence staining and qPCR (Figure S4A,B). RBLs were infected with wild type EBV for 0, 2 and 7 days or P3HR1 virus for 0, 2, and 4 days. 3C-qPCR was used to determine the effects of wild type or mutant virus on MYC ESEs looping to MYC TSS. MYCSE1 and MYCSE2 had low frequencies of interactions with the MYC promoter in RBLs. Wild type EBV infection resulted in gradually increased interactions between ESEs and MYC TSS (Figure 4B, top). In contrast, P3HR1 infection did not cause increased interactions (Figure 4B, bottom). These results implicated that EBNA2 as a driver of chromatin conformation changes at MYC ESEs, could effectively activate MYC transcription by enhancing interactions between MYC enhancers and promoter.

Looping factors CTCF, cohesins, YY1, and ZNF143 are important for long-range chromatin interactions. They can only bind to accessible chromatins. To determine the effect of EBV infection on chromatin accessibility, Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin followed by deep sequencing (ATAC-seq) was used. RBLs were infected with wild type or mutant EBV for 1, 2, 5, and 7 (wild-type only) days. ATAC-seq found that wild type EBV infection initially caused a dramatic increase in chromatin accessibility and then gradually reduced to lower levels at MYC ESEs. Surprisingly, P3HR1 infection also increased MYC ESE chromatin accessibility (Figure 4C). Similar finding was evident at CCND2 (Figure S4C). This data indicated that failure of mutant EBV to induce looping was not due to chromatin accessibility. EBNA2 may affect looping factor DNA binding or may act as a looping factor by itself. A similar trend was observed across all ESEs during the initial phase of infection (Figure 4D).

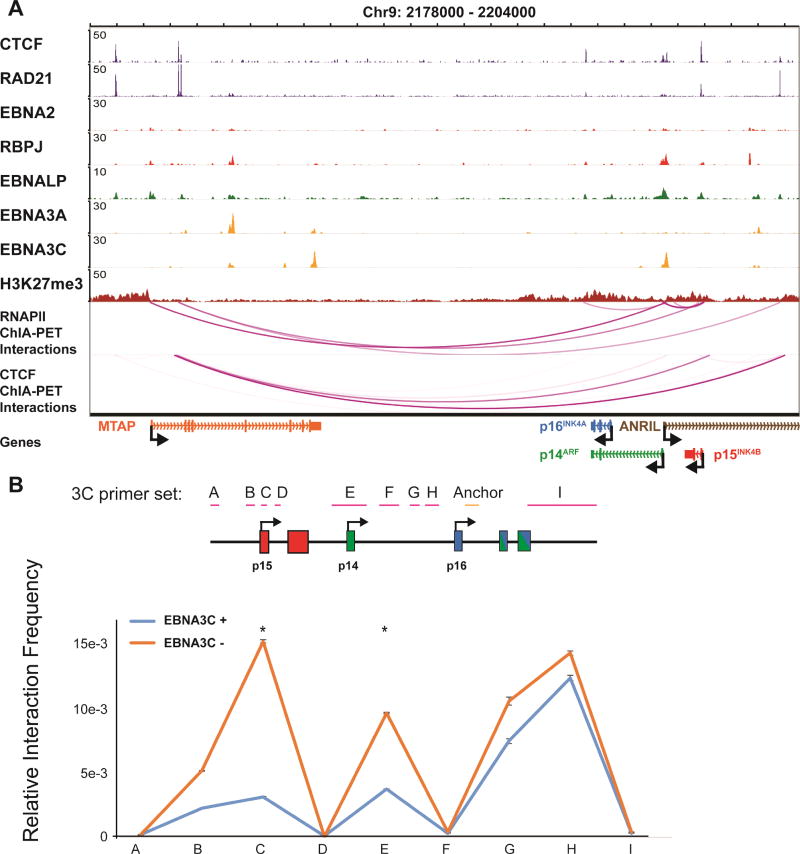

EBNA3C induced 3D conformation changes at the CDKN2A/B loci

The CDKN2A/B loci encode three tumor suppressors: p14ARF, p16INK4A and p15INK4B (Figure 5A). Both p14ARF and p16INK4A are co-regulated by EBNA3A and EBNA3C (Maruo et al., 2011; Skalska et al., 2013). p15INK4B was also identified as a target for repression by EBNA3A (Bazot et al., 2014). Given that only one significant EBNA3C peak was present at the p14ARF promoter, and the presence of other EBNA3A/C sites were distant from the loci (Figure 5A), we hypothesized that EBNA3A/C repress is through looping. Indeed, RNAPII ChIA-PET revealed that the p14ARF, p16INK4A and p15INK4B promoters, as well as MTAP, were linked together in LCLs through RNAPII (Figure 5A). Their physical interactions provided the molecular basis for their co-regulation.

Figure 5. EBNA3C reduced looping at the CDKN2A/B loci were.

(A) RNAPII ChIA-PET linked the p14ARF, p15INK4B promoter and p16INK4A gene body in LCLs. CDKN2A/B loci were also linked to MTAP promoter region. (B) EBNA3C inactivation increased looping at the CDKN2A/B loci. Primers for 3C were listed on the top. Anchor primer was also indicated. EBNA3C conditional LCLs were grown under permissive or non-permissive conditions. 3C assays were done and the interaction frequencies between the anchor and other primers were determined by qPCR. The efficiencies of PCR primer pairs were normalized with BAC DNA. GAPDH was used to normalize the amount of DNA used in qPCR. All data are represented as mean+/−SE. See also Figure S5.

To determine if EBNA3C regulates p15INK4B expression, conditional EBNA3C LCLs were grown under permissive or non-permissive condition for 14 days. qRT-PCR found EBNA3C inactivation increased p15INK4B expression (Figure S5A).

3C-qPCR was used to determine the effect of EBNA3C inactivation on the looping patterns at the CDKN2A/B loci. In the presence of EBNA3C, low frequencies of looping from p16INK4A to p14ARF, and p15INK4B were readily detectable (Figure 5B). Inactivation of EBNA3C led to significantly increased chromatin interactions between the three promoters (Figure 5B). EBNA3C inactivation had no effect on the looping of an irrelevant locus (Figure S5B). Taken together, these data indicated that all three genes were co-regulated by EBNA3C by disrupting physical interactions between the promoters to abolish transcription.

RNAPII signals at the CDKN2A/B loci were evident, suggesting that these promoters are not deficient for RNAPII recruitment. RNAPII is likely paused at these promoters. This phenomenon was also observed at the BIM locus, where RNAPII recruitment was not impaired by EBNA3C, but RNAPII S5 was not phosphorylated (Paschos et al., 2012).

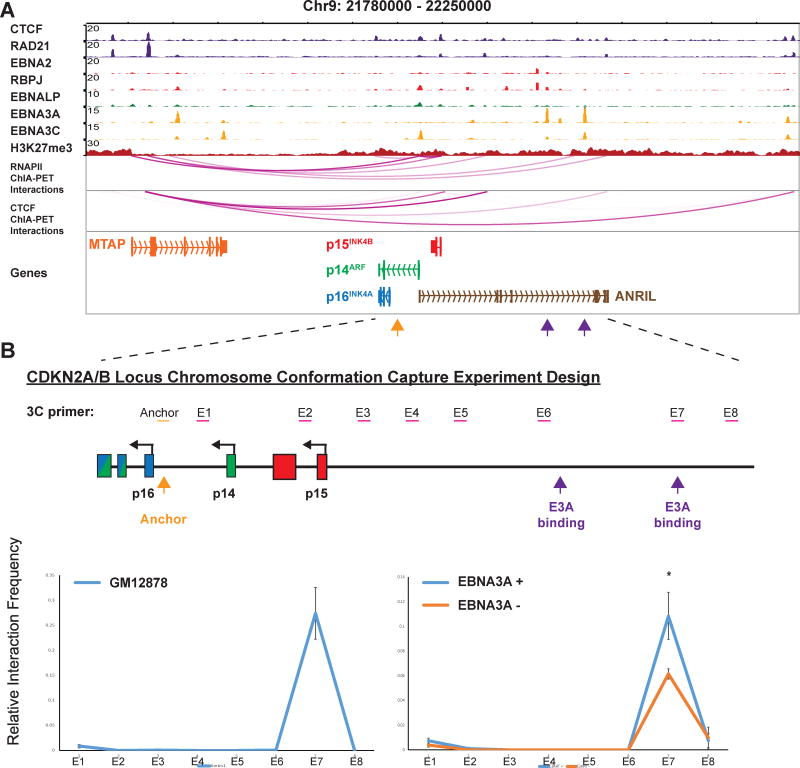

EBNA3A induced 3D conformation changes at the CDKN2A/B loci

EBNA3A binds to two distal sites >80kb upstream of the p16INK4A, p14ARF and p15INK4 B promoters (Schmidt et al., 2015). EBNA3C also has minor peaks at the same loci. Since no significant EBNA3A binding was found near the promoters, these EBNA3A sites >80kb upstream were likely candidates that repressed CDKN2A/B. RNAPII ChIA-PET found sites >80kb upstream of p15INK4B looped to enhancer sites near MTAP, which then looped back to CDKN2A/B (Figure 6A).

Figure 6. EBNA3A induced looping at the CDKN2A/B loci.

(A) RNAPII ChIA-PET linked EBNA3A peaks >80k upstream of CDKN2A/B loci to the MTAP promoter and gene body. MTAP promoter and gene body were then linked to the CDKN2A/B loci. Major EBNA3C (orange) or EBNA3A (purple) ChIP-seq peaks were indicated. (B) Primers used for 3C at the ~100 kb region of the CDKN2A/B loci. Anchor primer near p16INK4A was indicated. 3C assay was done in GM12878 LCL (left) or EBNA3A conditional LCLs (right) grown under permissive or non-permissive conditions. qPCR was used to determine the interaction frequencies. EBNA3A inactivation significantly reduced EBNA3A site looping to the CDKN2A/B loci (*P<0.05). All data are represented as mean+/−SE. See also Figure S6.

3C-qPCR was used to determine if these EBNA3A sites were linked to CDKN2A/B with primers spanning a ~150kb regions encompassing all three promoters and EBNA3A sites (Figure 6B). GM12878 LCLs had a high level of interaction between CDKN2A/B promoters and EBNA3A distal peak (primer E7, Figure 6B, left), but not the genomic regions outside the EBNA3A peak (primer E6). Similarly, LCLs expressing conditional EBNA3A had high interactions between EBNA3A distal peak and CDKN2A/B under the permissive condition. Inactivation of EBNA3A resulted in a significant (p < 0.05) reduction of interactions between the E7 peak and the p16INK4A promoter (Figure 6B, right), supporting that EBNA3A could exert its effect on the genes from a distal site through long-ranged interactions.

Since EBNA3A represses all three genes (Bazot et al., 2014; Maruo et al., 2011), the effect of EBNA3A inactivation on the looping amongst p16INK4A, p14ARF and p15INK4B promoters was determined. 3C-qPCR found EBNA3A inactivation also increased the chromatin interactions between the three promoters (Figure S6A). EBNA3A inactivation had no effect on the looping of an irrelevant locus (Figure S6B).

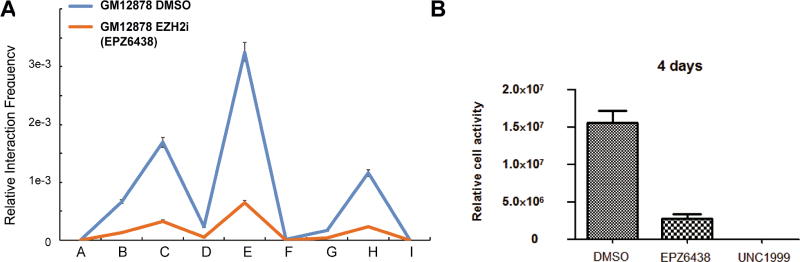

EZH2 inhibition altered looping at CDKN2A/B loci and reduced LCL growth

Polycomb Repressive Complexes (PRCs) play key roles in EBNA3A and EBNA3C mediated repression, and are also known to co-regulate p16INK4A, p14ARF and p15INK4B in other cells. PRC2 complex increase repressive H3K27me3 mark at the CDKN2A/B loci to repress their expression. (Harth-Hertle et al., 2013; Kheradmand Kia et al., 2009; Paschos et al., 2012; Skalska et al., 2010). EZH2 is the H3K27 methyl transferase component of the PRC2 complex. EZH2 can induce p15INK4B looping to p16INK4A (Kheradmand Kia et al., 2009). To evaluate the effect of EZH2 inactivation on the CDKN2A/B loci genome organization, a well characterized EZH2 inhibitors EPZ6438 was used. EZH2 inhibition reduced the interactions between the three promoters (Figure 7A). EZH2 inhibition had no effect on the loopings at an irrelevant locus (Figure S7). This is consistent with published studies where EZH2 knock down reduced the looping at the CDKN2A/B loci (Kheradmand Kia et al., 2009). Both EZH2 inhibitor EPZ6438 and UNC1999 also drastically reduced LCLs growth (Figure 7B). EZH2 inhibition reduces repressive H3K27me3, thus allows higher p16INK4A, p14ARF and p15INK4B expression to arrest cell growth. These results suggested that the EBNA3s, together with PRC2, played key roles in silencing this tumor suppressor locus through chromatin reorganization.

Figure 7. EZH2 inhibitor decreased CDKN2A/B looping and stopped LCL growth.

(A) GM12878 LCLs were grown in 1% FBS and treated with EZH2 inhibitor 20uM EPZ6438 for 4 Days. 3C-qPCR was used to determine the interaction frequencies at the CDKN2A/B loci. (B) GM12878 LCLs grown in 1% FBS were treated with 20uM EPZ6438 or 10uM UNC1999 for 4 days. Cell growth was determined using Cell Titer Glo. All data are represented as mean+/−SE. See also Figure S7.

Discussion

Human DNA is packed into a nucleus in an ordered fashion, allowing distant enhancers to regulate their direct target genes efficiently. Alterations in the spatial organization of chromatin can lead to developmental defects or cancer. 3D genome map generated from RNAPII ChIA-PET enabled us to link EBV enhancers to their direct target genes and construct an EBV regulome. A comprehensive understanding of viral regulome controlled by a human DNA tumor virus will not only allow us to understand the pathogenic mechanisms, but also identify potential therapeutics against virus related cancers.

EBV regulome contained many genes critically important for LCL growth and survival. It is striking that 30% of genes essential for LCL growth and survival were linked to an EBV enhancer, further supporting the notion that the virus has evolved to selectively target host genes and pathways critical for their growth and survival to achieve immortal growth. CFLAR, one of the most import survival factor identified by our CRISPR screen was linked to an ESE and multiple EBV enhancers. These enhancers located in both upstream and downstream regions, all linked to CFLAR TSS, and were occupied by all essential EBNAs and NF-κB. This multi-layered regulation will ensure the LCL survival. EBNA2 and LP are the main CCND2 activator (Sinclair et al., 1994). ChIA-PET linked multiple enhancers occupied by all the essential EBNAs and NF-κB subunits. This collaborative co-regulation by many EBV TFs will ensure sustained CCND2 expression and continued LCL proliferation.

187 ESEs were linked to 544 genes by ChIA-PET. A relatively small number of viral ESEs controlling a larger number of genes essential for LCL growth and survival is probably the most efficient way to subvert the host program. ESEs and their target genes mostly fall into the same domains define by CTCF. CTCF and cohesin binding sites function as insulators between the topological associated domains, segregating inactive genes from active enhancers. Most of GM12878 LCL RNAPII ChIA-PET linkages were intrachromosomal. Only 1.4% of the ChIA-PET linkages were interchromsomal (Tang et al., 2015). Surprisingly, some ESEs were linked to genes on other chromosomes. For example, EBF1 is linked to ESEs on chromosomes 7, 16, 17 and 20, and MYCSE2 is linked to LRSAM1 and RPL12 on chromosome 9. EBV is closely associate with endemic Burkitt’s lymphoma, where Ig/MYC translocation is a cancer hallmark. EBV may induce interchromosomal interactions to pre-condition the B cell for chromosome translocation and lead to lymphomas.

Some ESE targeted genes express at similar levels between LCLs and RBLs, such as EBF1 and PAX5. These TFs are fundamentally important for normal B cell functions. For example, EBF1 is a pioneering TF that opens the closed chromatin to allow subsequent TF bindings (Maier et al., 2004). It has been shown that BLIMP1 represses EBF1 and PAX5 expression during B cell differentiation (Shaffer et al., 2002). During transformation, EBV TFs gain control of these TFs thus they are no longer under the control of normal B cell transcription program. Therefore, EBV infected cells do not respond to differentiation signal and continue to grow.

ESE linked genes include many pro-survival genes, such as CFLAR, BCL2 and MCL1. Interestingly, pro-apoptotic genes, PMAIP1 (NOXA) and BID, were also linked to ESEs. Oncogenic stress upregulates PMAIP1 to induce autophagy and cell death (Elgendy et al., 2011). Therefore, under high levels of anti-apoptotic proteins BCL2 and MCL1, PMAIP1 likely only induces autophagy to provide additional nutrients for LCL growth, while cell death is inhibited.

Chromatin looping is an efficient way for EBNA3A/C to repress p14ARF, p16INK4A, and p15INK4B simultaneously. RNAPII ChIA-PET did link all three genes together. ChIP-seq signals for looping factor CTCF and ZNF143 were evident at the p14ARF, p15INK4B promoter and at the 3’ end of p16INK4A. CTCF dimerization can bring all three genes together. Removal of EBNA3C will likely allow CTCF to dimerize. This is consistent with the increased looping at this locus upon EBNA3C inactivation. EBNA3A can also recruit repressors CtBP and RBPJ (Hickabottom et al., 2002; Robertson et al., 1996). EZH2 inhibition reduce repressive H3K27me3. Like other cell type, EZH2 inhibition in LCLs reduced looping at CDKN2A/B and reduced LCL growth, likely due to increased p14ARF, p16INK4A, and p15INK4B expression. EZH2 may act through a different mechanism to repress this locus, probably by increasing the repressive H3K27me3.

This study highlights how the host 3D genome organization is subverted by a DNA tumor virus to cause cancer. EBV oncoproteins can alter the host genome organization to control key oncogenes and tumor suppressors. Understanding how these viral oncogenes function in reorganizing the host genome will likely allow identification of novel therapeutics.

STAR*METHODS

Contact for Reagent and Resource sharing

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Bo Zhao (bzhao@bwh.harvard.edu).

Experimental Model and Subject Details

Cell Culture

The GM12878-Cas9 cells, EBNA2-HT, EBNA3A-HT and EBNA3C-HT cells were previously cloned as described (Greenfeld et al., 2015; Maruo et al., 2003; Maruo et al., 2006; Zhao et al., 2006). All Lymphoblastoid Cell Lines were grown in RPMI supplemented with 1% L-glutamate, 1% Pen/Strep and 10% FBS. B958 ZHT, P3HR1 ZHT cells and virus induction were previously described (Calderwood et al., 2008) (Johannsen et al., 2004). B958 viruses were quantitated by infecting Resting B Lymphocytes followed by immune fluorescent staining of EBNALP using JF186 antibody (Finke et al., 1987). P3HR1 viruses were quantitated by qPCR (Ryan et al., 2004).

Primary Human B Cells

De-identified blood collars were obtained from the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Blood Bank, following institutional guidelines. The Epstein-Barr virus studies described in this paper were approved by the Brigham & Women’s Hospital Institutional Review Board. B cells were purified via negative selection, with RosetteSep Human B Cell Enrichment Cocktail and EasySep Human B Cell Enrichment Kits (StemCell Technologies), according to the manufacturer protocols.

Method Details

ChIA-PET analysis

ChIA-PET data were obtained from the recently published work (Tang et al., 2015), and the analysis of the ChIA-PET data to obtain the linkage information were done following the methods described in the original publication (Phanstiel et al., 2015; Quinlan and Hall, 2010; Tang et al., 2015). In short, ChIA-PET links were identified using ChIA-PET tool previous described (Guo et al. 2010), and confirmed using a separate software Mango (Phanstiel et al. 2015). We also used processed ChIA-PET data from GEO (Tang et al., 2015), RNA-POLII, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSM1872887 and CTCF: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSM1872886. RNAPII ChIA-PET links were then overlapped with the regions of our EBV enhancers, target gene promoter regions and gene bodies with BEDtools (Quinlan and Hall 2010) to identify EBV enhancer linked targets. The links were visualized using The Human Epigenome Browser at Washington University, as a custom session that has been made publicly available (see Data and Software Availability).

CRISPR knock out of ESEs

All gRNAs were designed using Benchling, a publically available webtool (www.benchling.com). sgRNAs with On and Off Target scores of > 60 (Doench et al., 2014) were selected. Dual gRNAs were cloned into pLentiGuide-Puro (Addgene Plasmid #52963) using the Multiplex gRNA kit (System Biosciences) according to the manufacturer protocol. Bacterial cultures for all gRNA vectors were grown at 30 °C to minimize recombination, and sequenced with the U6 promoter primer for verification of single or dual gRNAs.

Lentiviruses were packaged as described in the Broad GPP protocol (http://www.broadinstitute.org/rnai/public/resources/protocols). In short, 293FT cells (ThermoFischer Scientific) were transfected with viral packaging plasmids pCMV-VSV-G (Addgene #8454), psPAX2 (Addgene #12260) and the pLentiGuide-Puro vector containing the target sgRNA. Transfected 293FT cells were switched to high serum RPMI media 18h after transfection for a further 24h. The lentivirus containing supernatant was collected and filtered with a 0.45 micron filter. LCLs were transduced with the filtered lentivirus (Day 0) for 2 days, and then selected with 3ug/L Puromycin for 3 days. On Day 5, genomic DNA was extracted using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (Qiagen) and RNA was extracted with the PureLink RNA Mini kit (Ambion).

Genomic deletions were verified by PCR using the PrimeSTAR polymerase (Clonetech). qRT-PCR was done using the Power SYBR® Green RNA-to-CT™ 1-Step Kit (Applied Biosystems).

CRISPR knock out of RBPJ DNA binding motifs

Genome wide RBPJ binding motifs were identified for hg19 using homer (Heinz et al., 2010). Enhancers linked via RNAPII ChIA-PET to their target genes were filtered for both RBPJ ChIP-seq signal and RBPJ DNA binding motifs. We prioritized genes that were significantly regulated by EBNA2 in a previous study (Zhao et al., 2006). We designed gRNAs against each single RBPJ motif using Benchling and infected GM12878-Cas9 cells as described above. PCRs were performed across each RBPJ cut site for treatment and control cells, and analyzed using the Tracking of Indels by DEcomposition web server (https://tide-calculator.nki.nl/) (Brinkman et al., 2014).

Functional Enrichment Analysis

The enriched pathways of enhancers targeted genes were identified using the “;Identify Pathways” function of the IntPath database (Zhou et al., 2012) and DAVID database (Huang et al., 2008). The Gene Ontology enrichment analysis of enhancers targeted genes used the DAVID database.

Chromatin conformation capture assays

Conditional LCLs were grown under permissive or non-permissive conditions (EBNA2-HT: 2 Days, EBNA3A–HT: 10 Days, EBNA3C-HT: 14 days). 3C assays was done following published protocol (Kheradmand Kia et al., 2009; Liang et al., 2016). Cells were fixed with formaldehyde and then digested with the appropriate Restriction Enzymes (EcoRI, NEB) overnight. After dilution, DNA ends were ligated with T4 DNA ligase (NEB). After reverse cross-linking overnight at 65C, purified ligated genomic DNA from GM12878 was quantitated by qPCR. BACs spanning the entire region of the 600 kb region were EcoRI digested and ligated. qPCR analyses of the ligated BAC DNA was used to normalize the efficiencies of different primer pairs. GAPDH qPCR was used to normalize the loading for DNA for 3C-qPCR.

ATAC-seq

ATAC-seq was done with 50,000 cells. After preparation of nuclei, the nuclei were mixed with transposase reaction. The DNA was then purified and PCR amplified, and sequenced on a NextSeq 500. Adapters were trimmed from reads using trim_galore and mapped to hg19 with bowtie2 (Langmead et al., 2009). Duplicates were removed using PICARD and reads that fell within the ENCODE blacklist were also discarded. Quality Control was performed using ATAQC from the Parker lab (https://github.com/umijh/ataqc). Raw ATAC-seq reads for EBV transformed GM12878 LCLs were obtained from a previous study, and processed in parallel. All reads were down-sampled to 14 million reads per experiment using samtools (Li et al., 2009), and visualized using IGV (Shen et al., 2014).

TIDE analysis for RBPJ motif deletion

Lentivirus was used to deliver gRNAs targeting RBPJ motifs, as described above. Genomic DNA was extracted and PCR was performed to amplify the deletion. PCR sequencing was performed (Eton Biosciences) for the PCR product from both control or RBPJ motif targeted cells. The sequencing output was parsed using the Tracking of Indels by Decomposition (TIDE) software (https://tide-calculator.nki.nl/). Significant long ranged ChIA-PET interactions were detected using Mango (Phanstiel et al. 2015), following recommended guidelines for long-reads ChIA-PET. In short, linkers were parsed and removed from Paired End Tags (PETs) with parameters “--keepempty TRUE --maxlength 1000 --shortreads FALSE”. Reads were aligned with bowtie, with “-S -n 2 -l 50 -k 1 --chunkmbs 500 --sam-nohead --mapq 40 -m 1 --best”. Duplicates were removed from PETs and peak calling was performed using MACS2. The ChIP enrichment allows a background model by non-linear polymers. Mango uses a bayesian approach to account for distances between PETs and corrects for false positives using multiple hypothesis.

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

The software used in this paper have been documented under the Key Resources table. The accession number for RNA-seq datasets reported in this paper is GEO: GSE101666. The accession number for ATAC-seq datasets reported in this paper is GEO: GSE101426. The EBV-regulome resource track is now publicly available as a custom WashU Epigenome Browser session at http://epigenomegateway.wustl.edu/browser/?genome=hg19&session=AuL8qiK9Bf.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Epstein-Barr Virus enhancers loop to cellular genes essential for LCL growth and survival

EBV enhancers control expression of the cellular oncogene MYC

EBV transcription factors drive MYC enhancer-promoter looping

EBV transcription factors repress tumor suppressor CDKN2A/B through looping

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Yijun Ruan, Melissa Fullwood, Nicolas Bertin, and Megha Padi for helpful discussions. We thank Dr. Peter Kharchenko for computational resources. We thank Dr. Eric Johannsen for ZHT P3HR1 cells. We thank Dr. Daofeng Li for valuable suggestions and help in data visualization process. B.Z. is supported by R01AI123420 and R01CA047006. E.K. is supported by R01CA170023, and R01CA085180. B.G. is supported by a Burroughs Wellcome Medical Scientist career award. S.J. is a pre-doctoral Howard Hughes Medical Institute International Student Research fellow. H. Z. is a Leukemia and Lymphoma Society fellow. G.L. is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant no. 91440114.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

B.Z. is supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant no. R01AI123420) and the National Cancer Institute (grant nos. R01CA047006 and R01CA170023). E.K. is supported by the National Cancer Institute (grant nos. R01CA170023 and R01CA085180)

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, B. Z.; Methodology, S.J., H.Z., J.L., and B.Z.; Investigation, S.J., H.Z., J.L., C.G., C.W., L.K., S.S., Y.N., T. C., S.W., Y.M.; Formal Analysis, H.Z., S.J., S.W., G.L., and B.Z.; Writing – Original Draft, S.J. and B.Z; Writing – Review & Editing, S.J. and B.Z.; Data Curation, H.Z., S.J., G.L.; Resources, B.Z. and B.G.; Visualization, H.Z., S.J., and G.L.; Supervision, B.Z.; Funding Acquisition, B.Z., and E.K.

References

- Adelman K, Lis JT. Promoter-proximal pausing of RNA polymerase II: emerging roles in metazoans. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:720–731. doi: 10.1038/nrg3293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfieri C, Birkenbach M, Kieff E. Early events in Epstein-Barr virus infection of human B lymphocytes. Virology. 1991;181:595–608. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90893-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvey A, Tempera I, Tsai K, Chen HS, Tikhmyanova N, Klichinsky M, Leslie C, Lieberman PM. An atlas of the Epstein-Barr virus transcriptome and epigenome reveals host-virus regulatory interactions. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:233–245. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey SD, Zhang X, Desai K, Aid M, Corradin O, Cowper-Sal Lari R, Akhtar-Zaidi B, Scacheri PC, Haibe-Kains B, Lupien M. ZNF143 provides sequence specificity to secure chromatin interactions at gene promoters. Nat Commun. 2015;2:6186. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S, Lu J, Cai Q, Saha A, Jha HC, Dzeng RK, Robertson ES. The EBV Latent Antigen 3C Inhibits Apoptosis through Targeted Regulation of Interferon Regulatory Factors 4 and 8. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003314. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazot Q, Deschamps T, Tafforeau L, Siouda M, Leblanc P, Harth-Hertle ML, Rabourdin-Combe C, Lotteau V, Kempkes B, Tommasino M, et al. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 3A protein regulates CDKN2B transcription via interaction with MIZ-1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:9700–9716. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkman EK, Chen T, Amendola M, van Steensel B. Easy quantitative assessment of genome editing by sequence trace decomposition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:e168. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahir-McFarland ED, Davidson DM, Schauer SL, Duong J, Kieff E. NF-kappa B inhibition causes spontaneous apoptosis in Epstein-Barr virus-transformed lymphoblastoid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6055–6060. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100119497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderwood MA, Holthaus AM, Johannsen E. The Epstein-Barr virus LF2 protein inhibits viral replication. J Virol. 2008;82:8509–8519. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00315-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JI, Fauci AS, Varmus H, Nabel GJ. Epstein-Barr virus: an important vaccine target for cancer prevention. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:107fs107. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker J, Rippe K, Dekker M, Kleckner N. Capturing Chromosome Conformation. Science. 2002;295:1306–1311. doi: 10.1126/science.1067799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doench JG, Hartenian E, Graham DB, Tothova Z, Hegde M, Smith I, Sullender M, Ebert BL, Xavier RJ, Root DE. Rational design of highly active sgRNAs for CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene inactivation. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:1262–1267. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgendy M, Sheridan C, Brumatti G, Martin SJ. Oncogenic Ras-induced expression of Noxa and Beclin-1 promotes autophagic cell death and limits clonogenic survival. Mol Cell. 2011;42:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein MA, Achong BG, Barr YM. Virus Particles in Cultured Lymphoblasts from Burkitt’s Lymphoma. Lancet. 1964;1:702–703. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(64)91524-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faumont N, Durand-Panteix S, Schlee M, Gromminger S, Schuhmacher M, Holzel M, Laux G, Mailhammer R, Rosenwald A, Staudt LM, et al. c-Myc and Rel/NF-kappaB are the two master transcriptional systems activated in the latency III program of Epstein-Barr virus-immortalized B cells. J Virol. 2009;83:5014–5027. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02264-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finke J, Rowe M, Kallin B, Ernberg I, Rosen A, Dillner J, Klein G. Monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies against Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 5 (EBNA-5) detect multiple protein species in Burkitt’s lymphoma and lymphoblastoid cell lines. J Virol. 1987;61:3870–3878. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.12.3870-3878.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfeld H, Takasaki K, Walsh MJ, Ersing I, Bernhardt K, Ma Y, Fu B, Ashbaugh CW, Cabo J, Mollo SB, et al. TRAF1 Coordinates Polyubiquitin Signaling to Enhance Epstein-Barr Virus LMP1-Mediated Growth and Survival Pathway Activation. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004890. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman SR, Johannsen E, Tong X, Yalamanchili R, Kieff E. The Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 transactivator is directed to response elements by the J kappa recombination signal binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:7568–7572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada S, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein LP stimulates EBNA-2 acidic domain-mediated transcriptional activation. J Virol. 1997;71:6611–6618. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6611-6618.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harth-Hertle ML, Scholz BA, Erhard F, Glaser LV, Dölken L, Zimmer R, Kempkes B. Inactivation of Intergenic Enhancers by EBNA3A Initiates and Maintains Polycomb Signatures across a Chromatin Domain Encoding CXCL10 and CXCL9. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003638. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz S, Benner C, Spann N, Bertolino E, Lin YC, Laslo P, Cheng JX, Murre C, Singh H, Glass CK. Simple Combinations of Lineage-Determining Transcription Factors Prime cis-Regulatory Elements Required for Macrophage and B Cell Identities. Molecular Cell. 2010;38:576–589. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkel T, Ling PD, Hayward SD, Peterson MG. Mediation of Epstein-Barr virus EBNA2 transactivation by recombination signal-binding protein J kappa. Science. 1994;265:92–95. doi: 10.1126/science.8016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickabottom M, Parker GA, Freemont P, Crook T, Allday MJ. Two nonconsensus sites in the Epstein-Barr virus oncoprotein EBNA3A cooperate to bind the co-repressor carboxyl-terminal-binding protein (CtBP) J Biol Chem. 2002;277:47197–47204. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208116200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howley PM. Gordon Wilson Lecture: Infectious Disease Causes of Cancer: Opportunities for Prevention and Treatment. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2015;126:117–132. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Sherman BT, Stephens R, Baseler MW, Lane HC, Lempicki RA. DAVID gene ID conversion tool. Bioinformation. 2008;2:428–430. doi: 10.6026/97320630002428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S, Willox B, Zhou H, Holthaus AM, Wang A, Shi TT, Maruo S, Kharchenko PV, Johannsen EC, Kieff E, et al. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 3C binds to BATF/IRF4 or SPI1/IRF4 composite sites and recruits Sin3A to repress CDKN2A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:421–426. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321704111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannsen E, Luftig M, Chase MR, Weicksel S, Cahir-McFarland E, Illanes D, Sarracino D, Kieff E. Proteins of purified Epstein-Barr virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:16286–16291. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407320101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser C, Laux G, Eick D, Jochner N, Bornkamm GW, Kempkes B. The proto-oncogene c-myc is a direct target gene of Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2. J Virol. 1999;73:4481–4484. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.4481-4484.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalchschmidt JS, Gillman AC, Paschos K, Bazot Q, Kempkes B, Allday MJ. EBNA3C Directs Recruitment of RBPJ (CBF1) to Chromatin during the Process of Gene Repression in EBV Infected B Cells. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005383. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempkes B, Spitkovsky D, Jansen-Durr P, Ellwart JW, Kremmer E, Delecluse HJ, Rottenberger C, Bornkamm GW, Hammerschmidt W. B-cell proliferation and induction of early G1-regulating proteins by Epstein-Barr virus mutants conditional for EBNA2. EMBO J. 1995;14:88–96. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb06978.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kheradmand Kia S, Solaimani Kartalaei P, Farahbakhshian E, Pourfarzad F, von Lindern M, Verrijzer CP. EZH2-dependent chromatin looping controls INK4a and INK4b, but not ARF, during human progenitor cell differentiation and cellular senescence. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2009;2:16. doi: 10.1186/1756-8935-2-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R. and Genome Project Data Processing, S. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang J, Zhou H, Gerdt C, Tan M, Colson T, Kaye KM, Kieff E, Zhao B. Epstein-Barr virus super-enhancer eRNAs are essential for MYC oncogene expression and lymphoblast proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:14121–14126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1616697113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman-Aiden E, van Berkum NL, Williams L, Imakaev M, Ragoczy T, Telling A, Amit I, Lajoie BR, Sabo PJ, Dorschner MO, et al. Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science. 2009;326:289–293. doi: 10.1126/science.1181369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling PD, Peng RS, Nakajima A, Yu JH, Tan J, Moses SM, Yang WH, Zhao B, Kieff E, Bloch KD, et al. Mediation of Epstein-Barr virus EBNA-LP transcriptional coactivation by Sp100. Embo J. 2005;24:3565–3575. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling PD, Rawlins DR, Hayward SD. The Epstein-Barr virus immortalizing protein EBNA-2 is targeted to DNA by a cellular enhancer-binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:9237–9241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longnecker RKE, Cohen JI. Epstein-Barr Virus. 8. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a Wolters Kluwer Business; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Walsh MJ, Bernhardt K, Ashbaugh CW, Trudeau SJ, Ashbaugh IY, Jiang S, Jiang C, Zhao B, Root DE, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 Screens Reveal Epstein-Barr Virus-Transformed B Cell Host Dependency Factors. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;21:580–591. e587. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier H, Ostraat R, Gao H, Fields S, Shinton SA, Medina KL, Ikawa T, Murre C, Singh H, Hardy RR, et al. Early B cell factor cooperates with Runx1 and mediates epigenetic changes associated with mb-1 transcription. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1069–1077. doi: 10.1038/ni1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruo S, Johannsen E, Illanes D, Cooper A, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr Virus nuclear protein EBNA3A is critical for maintaining lymphoblastoid cell line growth. J Virol. 2003;77:10437–10447. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.19.10437-10447.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruo S, Johannsen E, Illanes D, Cooper A, Zhao B, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein 3A domains essential for growth of lymphoblasts: transcriptional regulation through RBP-Jkappa/CBF1 is critical. J Virol. 2005;79:10171–10179. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10171-10179.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruo S, Wu Y, Ishikawa S, Kanda T, Iwakiri D, Takada K. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein EBNA3C is required for cell cycle progression and growth maintenance of lymphoblastoid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19500–19505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604919104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruo S, Wu Y, Ito T, Kanda T, Kieff ED, Takada K. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein EBNA3C residues critical for maintaining lymphoblastoid cell growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4419–4424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813134106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruo S, Zhao B, Johannsen E, Kieff E, Zou J, Takada K. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigens 3C and 3A maintain lymphoblastoid cell growth by repressing p16INK4A and p14ARF expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:1919–1924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019599108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochiai K, Maienschein-Cline M, Simonetti G, Chen J, Rosenthal R, Brink R, Chong AS, Klein U, Dinner AR, Singh H, et al. Transcriptional regulation of germinal center B and plasma cell fates by dynamical control of IRF4. Immunity. 2013;38:918–929. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi M, Holthaus AM, Calderwood MA, Lai CY, Krastins B, Sarracino D, Johannsen E. The EBNA3 family of Epstein-Barr virus nuclear proteins associates with the USP46/USP12 deubiquitination complexes to regulate lymphoblastoid cell line growth. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004822. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong CT, Corces VG. Enhancer function: new insights into the regulation of tissue-specific gene expression. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:283–293. doi: 10.1038/nrg2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschos K, Parker GA, Watanatanasup E, White RE, Allday MJ. BIM promoter directly targeted by EBNA3C in polycomb-mediated repression by EBV. Nucleic Acids Research. 2012;40:7233–7246. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patnaik A, Rosen LS, Tolaney SM, Tolcher AW, Goldman JW, Gandhi L, Papadopoulos KP, Beeram M, Rasco DW, Hilton JF, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Abemaciclib, an Inhibitor of CDK4 and CDK6, for Patients with Breast Cancer, Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, and Other Solid Tumors. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:740–753. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-0095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perciavalle RM, Stewart DP, Koss B, Lynch J, Milasta S, Bathina M, Temirov J, Cleland MM, Pelletier S, Schuetz JD, et al. Anti-apoptotic MCL-1 localizes to the mitochondrial matrix and couples mitochondrial fusion to respiration. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:575–583. doi: 10.1038/ncb2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phanstiel DH, Boyle AP, Heidari N, Snyder MP. Mango: a bias-correcting ChIA-PET analysis pipeline. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3092–3098. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portal D, Zhao B, Calderwood MA, Sommermann T, Johannsen E, Kieff E. EBV nuclear antigen EBNALP dismisses transcription repressors NCoR and RBPJ from enhancers and EBNA2 increases NCoR-deficient RBPJ DNA binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:7808–7813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104991108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portal D, Zhou H, Zhao B, Kharchenko PV, Lowry E, Wong L, Quackenbush J, Holloway D, Jiang S, Lu Y, et al. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen leader protein localizes to promoters and enhancers with cell transcription factors and EBNA2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:18537–18542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317608110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan AR, Hall IM. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:841–842. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson ES, Lin J, Kieff E. The amino-terminal domains of Epstein-Barr virus nuclear proteins 3A, 3B, and 3C interact with RBPJ(kappa) J Virol. 1996;70:3068–3074. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.3068-3074.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan JL, Fan H, Glaser SL, Schichman SA, Raab-Traub N, Gulley ML. Epstein-Barr virus quantitation by real-time PCR targeting multiple gene segments: a novel approach to screen for the virus in paraffin-embedded tissue and plasma. J Mol Diagn. 2004;6:378–385. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60535-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt SC, Jiang S, Zhou H, Willox B, Holthaus AM, Kharchenko PV, Johannsen EC, Kieff E, Zhao B. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 3A partially coincides with EBNA3C genome-wide and is tethered to DNA through BATF complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:554–559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1422580112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer AL, Lin KI, Kuo TC, Yu X, Hurt EM, Rosenwald A, Giltnane JM, Yang L, Zhao H, Calame K, et al. Blimp-1 orchestrates plasma cell differentiation by extinguishing the mature B cell gene expression program. Immunity. 2002;17:51–62. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00335-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen L, Shao N, Liu X, Nestler E. ngs.plot: Quick mining and visualization of next-generation sequencing data by integrating genomic databases. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:284. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr CJ, Beach D, Shapiro GI. Targeting CDK4 and CDK6: From Discovery to Therapy. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:353–367. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair AJ, Palmero I, Peters G, Farrell PJ. EBNA-2 and EBNA-LP cooperate to cause G0 to G1 transition during immortalization of resting human B lymphocytes by Epstein-Barr virus. Embo J. 1994;13:3321–3328. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06634.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skalska L, White RE, Franz M, Ruhmann M, Allday MJ. Epigenetic repression of p16(INK4A) by latent Epstein-Barr virus requires the interaction of EBNA3A and EBNA3C with CtBP. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000951. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skalska L, White RE, Parker GA, Sinclair AJ, Paschos K, Allday MJ. Induction of p16(INK4A) Is the Major Barrier to Proliferation when Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) Transforms Primary B Cells into Lymphoblastoid Cell Lines. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003187. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Z, Luo OJ, Li X, Zheng M, Zhu JJ, Szalaj P, Trzaskoma P, Magalska A, Wlodarczyk J, Ruszczycki B, et al. CTCF-Mediated Human 3D Genome Architecture Reveals Chromatin Topology for Transcription. Cell. 2015;163:1611–1627. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang A, Welch R, Zhao B, Ta T, Keles S, Johannsen E. Epstein-Barr Virus Nuclear Antigen 3 (EBNA3) Proteins Regulate EBNA2 Binding to Distinct RBPJ Genomic Sites. J Virol. 2015;90:2906–2919. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02737-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Rowe M, Lundgren E. Expression of the Epstein Barr virus transforming protein LMP1 causes a rapid and transient stimulation of the Bcl-2 homologue Mcl-1 levels in B-cell lines. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4610–4613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyte Warren A, Orlando David A, Hnisz D, Abraham Brian J, Lin Charles Y, Kagey Michael H, Rahl Peter B, Lee Tong I, Young Richard A. Master Transcription Factors and Mediator Establish Super-Enhancers at Key Cell Identity Genes. Cell. 2013;153:307–319. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood CD, Veenstra H, Khasnis S, Gunnell A, Webb HM, Shannon-Lowe C, Andrews S, Osborne CS, West MJ. MYC activation and BCL2L11 silencing by a tumour virus through the large-scale reconfiguration of enhancer-promoter hubs. Elife. 2016;5 doi: 10.7554/eLife.18270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B, Barrera LA, Ersing I, Willox B, Schmidt SC, Greenfeld H, Zhou H, Mollo SB, Shi TT, Takasaki K, et al. The NF-kappaB genomic landscape in lymphoblastoid B cells. Cell Rep. 2014;8:1595–1606. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B, Maruo S, Cooper A, M RC, Johannsen E, Kieff E, Cahir-McFarland E. RNAs induced by Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 in lymphoblastoid cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1900–1905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510612103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B, Zou J, Wang H, Johannsen E, Peng CW, Quackenbush J, Mar JC, Morton CC, Freedman ML, Blacklow SC, et al. Epstein-Barr virus exploits intrinsic B-lymphocyte transcription programs to achieve immortal cell growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:14902–14907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108892108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Jin J, Zhang H, Yi B, Wozniak M, Wong L. IntPath--an integrated pathway gene relationship database for model organisms and important pathogens. BMC Syst Biol. 2012;6(Suppl 2):S2. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-6-S2-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Schmidt SC, Jiang S, Willox B, Bernhardt K, Liang J, Johannsen EC, Kharchenko P, Gewurz BE, Kieff E, et al. Epstein-Barr virus oncoprotein super-enhancers control B cell growth. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:205–216. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.