Abstract

Quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs) are commonly used antiseptics that are now known to be subject to bacterial resistance. The prevalence and mechanisms of such resistance, however, remain underexplored. We investigated a variety of QACs, including those with multicationic structures (multiQACs), and the resistance displayed by a variety of Staphylococcus aureus strains with and without genes encoding efflux pumps, the purported main driver of bacterial resistance in MRSA. Through MIC, kinetic, and efflux-based assays, we find that neither the qacR/qacA system present in S. aureus nor another efflux pump system is the main reason for bacterial resistance to QACs. Our findings suggest that membrane composition is the predominant driver that allows CA-MRSA to withstand the assault of conventional QAC antiseptics.

Keywords: quaternary ammonium compound, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, qac, resistance

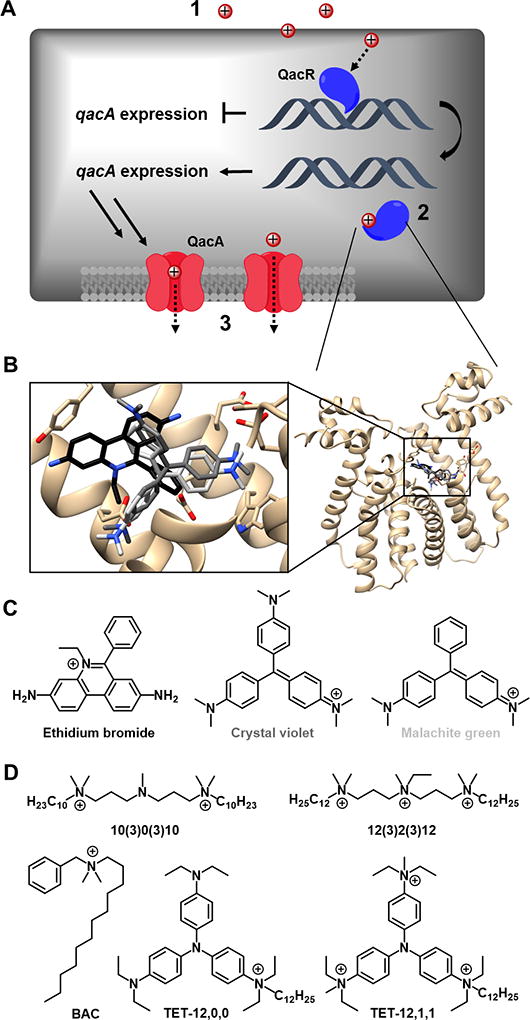

Quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs) comprise a large class of agents widely used in hospital and community settings to eradicate bacteria. Their amphiphilic nature causes cell membrane disruption, with gradient destruction and leakage of cellular material ensuing.1,2 Bacterial resistance to such compounds has been demonstrated by a change in membrane content3 and by transcriptionally regulated qac efflux systems.4–6 The number of publications detailing qac genes and their associated resistance levels has risen dramatically in recent years, leading to claims that this resistance may render commonly used QACs such as benzalkonium chloride (BAC) and chlorhexidine less effective.7–11 This efflux system commonly utilizes qacR, the gene product of which (QacR) transcriptionally regulates qacA, which produces the most prevalent QAC-specific efflux pump, QacA (Figure 1A). It has been suggested that this system may be limited to mono- and biscationic QACs.12 We have been actively testing this hypothesis by exploring the substrate scope of the system using analogs of known substrates of QacR; its native aromatic ligands have been co-crystallized by others, and show electrostatic and π-π interactions with acidic and aromatic residues, respectively (Figure 1B).13 These substrates include natural product QACs such as berberine, intercalating agent ethidium bromide, and commercially available dyes crystal violet (CV) and malachite green (MG) (Figure 1B,C).7 Throughout our work we too have yet to identify qac-resistance to any trisQACs that bear multiple lipophilic tails, further supporting the observation above.

Figure 1.

(A) Postulated mechanisms of differences in QAC activity against MRSA: (1) Differences in membrane permeability would lead to differences in membrane damage and intracellular accumulation; (2) QacR recognition, which affects the production of efflux pumps; and/or (3) QacA recognition, which affects the ability of QACs to be effluxed. (B) Crystal structures of QacR with select native dye substrates relevant to this work (ethidium bromide = black, crystal violet = dark grey, malachite green = light grey), with chemical structures shown in (C). (D) QACs evaluated in this study, including dye analogs.

The presence of qac genes has most often been associated with community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA), such as USA300-0114,14 which differs from the hospital-acquired evolutionary line (HA-MRSA). Though both are designated MRSA because they contain a mobile genetic element staphylococcal chromosomal cassette mec (SCCmec) - conferring resistance to methicillin - they have evolved separately, yielding distinct virulence and resistance profiles.15,16 Specifically, while both strains express significant quantities of PBPs overall, CA-MRSA generally expresses lower levels of PBP2a, encoded by mecA, than HA-MRSA.17 It has been postulated these differences render HA-MRSA less virulent and therefore less able to survive outside of healthcare settings. Strains lacking mec are designated methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA); examples include SH1000 and the genetically-manipulated S. aureus qac strains (qacSA) used herein (Table 1), all of which derive from NCTC 8325.3,18

Table 1.

Strains and their corresponding resistance profiles relevant to this work

Through our previous studies with diverse QAC scaffolds and charge state, we observed large differences in minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) between MSSA and qac-bearing CA-MRSA (up to 63-fold) for many aryl and monocationic QACs, while multiQACs displayed more uniform activity (Table 2).19–21 Upon examination of the literature on QAC resistance, we found a surprising amount of biochemical space left underexplored, and thus were motivated to further probe the mechanism of QAC resistance with our existing bis- and triscationic QACs (collectively, multiQACs), based on both linear architectures and aromatic cores designed to mimic dye structures (Figure 1D). We postulated that this differential in bioactivity between CA- MRSA and MSSA was founded in this qac-resistance machinery and wanted to further characterize the role it played using our chemical library. We set out to perform inhibitory, kinetic, and efflux-based assays in order to assess details of the resistance mechanism unique to QACs and to determine if this “selective resistance“ was strictly related to the qac genes or to some other intrinsic property of trisQACs.

Table 2.

Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MIC) against S. aureus and qacSA strains. Values are reported in micromolar.

| Compound | MSSA | CA- MRSA |

SK 982 (parent) |

SK 5872 (qacA/R) |

SK 5873 (qacA) |

SK 5791 (qacR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAC | 8 | 32 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 2 |

| 10(3)0(3)10 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 12(3)2(3)12 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 |

| TET-12,0,0 | 2 | 125 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 4 |

| TET-12,1,1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

From the onset, we postulated that the dramatic bacterial resistance experienced by dye-based monoQACs and other aromatic multiQACs can arise from one of three modes of action (Figure 1A). The first possibility is that, in contrast to monoQACs, multiQACs are less likely to traverse the cell membrane due to their increased cationic charge thus preventing the intracellular buildup of QACs and triggering the overexpression of QacA (Figure 1A, 1). A second mechanism focuses on the binding site of QacR and its ability to recognize more complex substrates such as the multiQACs (Figure 1A, 2). A third possible mechanism involves an inability of multiQAC efflux by QacA, resulting in the accumulation of QAC and cell death (Figure 1A, 3). To examine these questions we strategically selected four of our lead compounds, alongside benzalkonium dodecyl chloride (BAC). We chose three of our multiQACs that showed broad-spectrum activity against MSSA and CA-MRSA strains and one specific monoQAC that demonstrated a 63-fold decrease in activity against CA-MRSA (Figure 1D, Table 2). We sought to answer two key questions going forward – 1) how do multiQACs evade qac-resistance and 2) is the qac efflux system responsible for the 63-fold change in activity observed between MSSA and CA-MRSA?

Previous efforts in our laboratories explored if QacR was responsible for the limited development of resistance for some compounds.21 We postulated that by conducting a potentiation assay, wherein bacteria are dosed with a sub-lethal concentration of a compound known to be recognized by QacR, that the activation of qac machinery would occur and thereby cause an increase in MIC values of multiQACs.22 However, dosing of CA-MRSA with a sub-MIC amount of BAC, a known substrate for QAC resistance, and varying concentrations of our multiQAC analogs did not result in any significant change in MIC values. This result suggests that such monocationic derivatives capable of eliciting resistance on their own, are unable to elicit resistance to other compounds and providing evidence in opposition to our second proposed explanation (Figure 1A, 2).

It is well known that CA-MRSA harbors a number of resistance plasmids and efflux pumps. Therefore, in an effort to focus our investigation specifically on the qac-resistance system, we obtained strains of S. aureus containing qacA, qacR, both genes, or neither3 to directly evaluate QAC activity. The inhibitory activity (MIC) of five mono- and multiQACs were tested against strains of S. aureus bearing qac resistance genes (qacSA) (Table 2). SK982 is the parent strain that possesses no qac-resistance plasmid; SK5872 possesses both qacA for generation of the efflux pump and qacR for transcriptional regulation; SK5873 possesses qacA only; and SK5791 possesses qacR only.

We were surprised to observe no significant differences in MICs among the four strains differing in qac composition for any compound tested, despite some major differences in activity between MSSA and CA-MRSA. When comparing the two monocationic QACs tested (BAC and TET-12,0,0), a modest ~4-fold reduction in activity was observed for qacA-carrying strains SK5872 and SK5873, as compared to the strains lacking qacA (SK982 and SK5791); this was not observed for multicationic species. Further, TET-12,0,0 did display an 8-fold reduction in activity as compared to tris-cationic analog TET-12,1,1 for qacA-carrying strains, suggesting that the QacA efflux of monoQACs plays some role in differentiating between these two compounds; however, it cannot fully explain the increase observed in CA-MRSA.

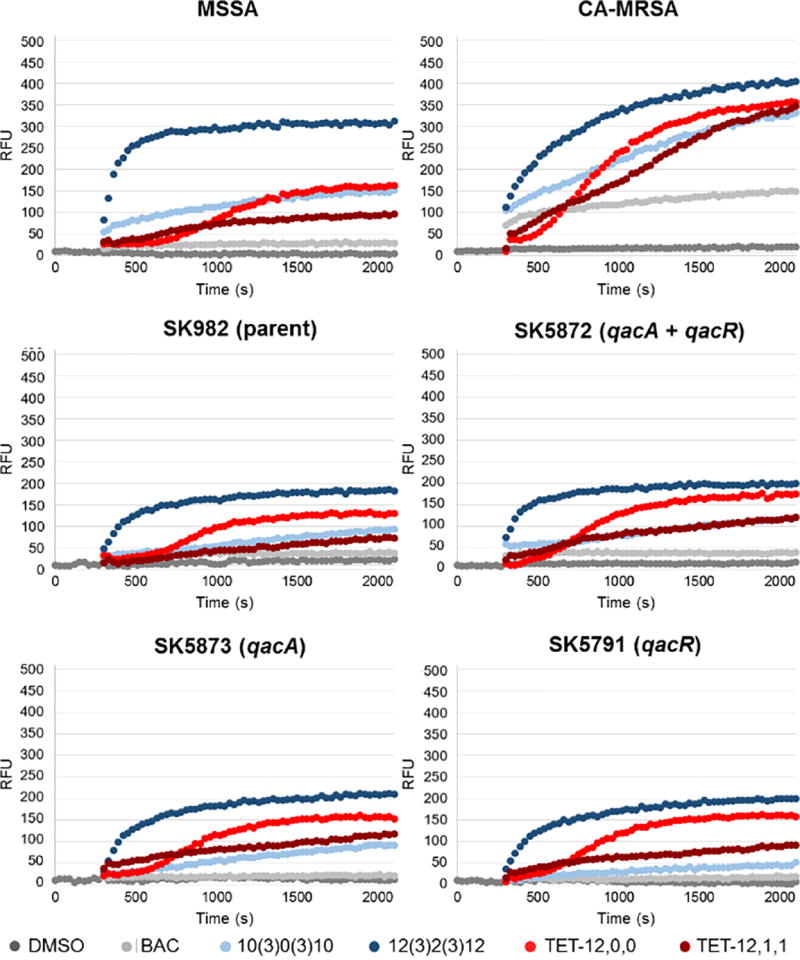

In order to better characterize the lytic activity of QACs, and more specifically, the kinetic binding profile, we evaluated membrane permeability using a propidium iodide fluorescence assay. Propidium iodide fluorescently stains dead or heavily membrane-damaged cells, and allows for facile and rapid data collection. Surprisingly, the curves for each compound was similar across five of the six strains of S. aureus (Figure 2). We expected to see striking differences based on our hypotheses that BAC and TET-12,0,0 are being recognized by the qac system, yet the only differences occurred in CA-MRSA, where membrane permeability occurred to a much greater extent for all compounds – on the order of 2-fold for each compound in terms of relative fluorescence units (RFU). The assay clearly shows an increased affinity by the CA-MRSA membrane for the four novel QACs when compared to the other strains, potentially hinting at a preferential selectivity based on the membrane composition.

Figure 2.

Representative membrane permeability plots for alkyl and aryl QACs. QAC was added at t = 300s. DMSO represents the untreated control. RFU = relative fluorescence units of propidium iodide, which provides a measure of membrane permeability.

Since inhibitory activity against various qacSA strains was not significantly different (as determined both by MIC assays and fluorescence studies), we postulated that perhaps the differences in activity between MSSA and qac-bearing CA-MRSA could additionally be explained by other multidrug efflux pumps found in CA-MRSA. One method of probing the general efflux activity of a bacterium is by comparing the inhibitory activity of a compound in both the presence and absence of an efflux pump inhibitor (EPI). This can be thought of as the inverse to a potentiation assay; in this case, bacteria are dosed with a QAC + EPI, or QAC alone, and any resulting differences in MIC can be attributed to efflux. QacA is multidrug efflux pump that is powered by proton motive forces; therefore we utilized two distinct classes of EPIs. The first, reserpine, is a broad inhibitor of multidrug resistance pumps23 and targets several families of efflux pumps.24 The second, carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) is a protonophore and proton motive force uncoupler.25,26

Neither of the strains, MSSA nor CA-MRSA, showed significant differences in the antibacterial activity of our multiQACs, suggesting that efflux is either not heavily involved or not significant enough to cause the marked differences in vivo. In contrast, BAC showed a 4-fold increase in activity against CA-MRSA dosed with either reserpine or CCCP, suggesting that efflux may be partially responsible for the decreased activity against CA-MRSA as compared to MSSA, in line with our earlier findings with qacSA strains. The concentrations of EPIs used correspond to those in the literature and have been shown to drastically recover the bioactivity of effluxed compounds.27

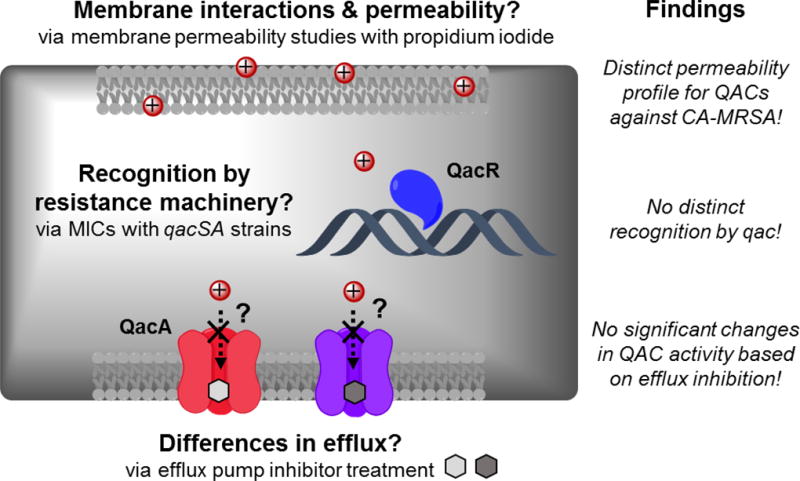

The work presented here, summarized in Figure 3, adds foundational knowledge to the field of QAC resistance while also raising questions for future study. Initial hypotheses were based on specific interactions between permability of the QACs between MSSA and CA-MRSA strains, the QAC substrate and QacR, or the greater cell permeation of QACs possessing rigid or aromatic moieties (Figure 1A).28 It was found that there were distinct differences in membrane permeability as assessed by fluorescence spectroscopy. This finding lends credence to the evolving theory that amphiphilic multiQACs are able to evade resistance by their increased affinity to the cell surface (Mechanism 1 in Figure 1A); however, this discovery does not explain the differential activity of TET-12,0,0 between susceptible and resistant strains. In addition, neither qac nor other efflux systems appear to be the primary drivers of the differential activity reported, hinting that differences in membrane composition and interactions thereof are paramount for resistance. This would parallel the suggestion that differences in membrane composition between Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria are the primary reason for differing QAC susceptibility. In an analogous manner, we speculate that the differential in activity of QACs between CA-MRSA and MSSA may reside in the intracies of the membrane composition. More specifically, as noted earlier, CA-MRSA differs significantly from MSSA in the presence of PBPs. Little work has been done to investigate the role that PBPs play in broad-spectrum resistance. These findings hint at an ancillary role for these infamous proteins and warrant further investigation.

Figure 3.

Summary of possible explanations of QAC resistance in CA-MRSA, assays designed to explore each hypothesis, and findings from each realm.

Experimental Section

Compounds were synthesized as reported previously.7,21 Laboratory strains of bacteria were grown at 37°C overnight in 10mL of appropriate media from 15% glycerol freezer stocks maintained at -80°C. Strains were obtained from ATCC, Professor Bettina Buttaro (Lewis Katz School of Medicine, Temple University), and Professor Arnold Bayer (David Geffen School of Medicine, UCLA).

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)

Into each well of a U-bottom 96-well plate (BD Biosciences, BD 351177) containing 100µL of compound solution was dosed 100µL of overnight bacterial culture diluted to ca. 106 cfu/mL in Mueller Hinton media. For the EPI MIC studies, reserpine or CCCP was added (as a solution in DMSO) to yield final test concentrations of 32 and 1µM, respectively. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 72 hours, upon which time wells were evaluated visually for bacterial growth. The MIC was determined as the lowest concentration of compound resulting in no bacterial growth visible to the naked eye, based on the majority of three independent trials.

Propidium iodide membrane permeability kinetics

Into an Eppendorf tube, 1mL of bacterial culture (OD 0.7) was pipetted, centrifuged at 10,000rpm for 10 minutes, and the resulting cell pellet was washed with 1mL of DI H2O. The pellet was then suspended in 1mL of PBS and 130µL were transferred to a black-walled, clear bottom 96-well plate (Corning 3631). To each well, 10µL of 150µM of propidium iodide solution (in DMSO, Life Technologies, L7012) was added. Fluorescence was measured every 30 seconds for 5 minutes prior to the addition of compound on a spectrofluorometer (SpectraMax Gemini EM, Molecular Devices) at 535nm excitation/617nm emission wavelengths. Compound was added (10µL of 1mM stock solution) and fluorescence was monitored every 30 seconds for 30 minutes. At least four independent replicates were performed for each data point.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. A.S. Bayer (Harbor-UCLA Medical Center) for graciously providing the qac strains. This work was funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences R35 GM119426 (W.M.W), Temple and Villanova Universities. M.C.J. acknowledges a National Science Foundation fellowship (DGE1144462).

References

- 1.Gilbert P, Moore LE. Cationic antiseptics: Diversity of action under a common epithet. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2005;99(4):703–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ioannou CJ, Hanlon GW, Denyer SP. Action of disinfectant quaternary ammonium compounds against Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007;51(1):296–306. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00375-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bayer AS, Kupferwasser LI, Brown MH, Skurray RA, Grkovic S, Jones T, Mukhopadhay K, Yeaman MR. Low-level resistance of staphylococcus aureus to thrombin-induced platelet microbicidal protein 1 in vitro associated with qacA gene carriage is independent of multidrug efflux pump activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006;50(7):2448–2454. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00028-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paulsen IT, Brown MH, Littlejohn TG, Mitchell BA, Skurray RA. Multidrug resistance proteins QacA and QacB from Staphylococcus aureus: membrane topology and identification of residues involved in substrate specificity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93(8):3630–3635. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown M, Skurray R. Staphylococcal multidrug efflux protein QacA. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001;3(2):163–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jennings MC, Minbiole KPC, Wuest WM. Quaternary Ammonium Compounds: An Antimicrobial Mainstay and Platform for Innovation to Address Bacterial Resistance. ACS Infect. Dis. 2015;1(7):288–303. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.5b00047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jennings MC, Buttaro BA, Minbiole KPC, Wuest WM. Bioorganic Investigation of Multicationic Antimicrobials to Combat QAC-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. ACS Infect. Dis. 2015;1(7):304–309. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.5b00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vali L, Davies SE, Lai LLG, Dave J, Amyes SGB. Frequency of biocide resistance genes, antibiotic resistance and the effect of chlorhexidine exposure on clinical methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2008;61(3):524–532. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furi L, Ciusa ML, Knight D, Di Lorenzo V, Tocci N, Cirasol D, Aragones L, Coelho JR, Freitas AT, Marchi E, et al. Evaluation of reduced susceptibility to quaternary ammonium compounds and bisbiguanides in clinical isolates and laboratory-generated mutants of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013;57(8):3488–3497. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00498-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Longtin J, Seah C, Siebert K, McGeer A, Simor A, Longtin Y, Low DE, Melano RG. Distribution of antiseptic resistance genes qacA, qacB, and smr in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated in Toronto, Canada, from 2005 to 2009. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011;55(6):2999–3001. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01707-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buffet-Bataillon S, Tattevin P, Bonnaure-Mallet M, Jolivet-Gougeon A. Emergence of resistance to antibacterial agents: The role of quaternary ammonium compounds - A critical review. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2012;39(5):381–389. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell BA, Brown MH, Skurray RA. QacA multidrug efflux pump from Staphylococcus aureus: Comparative analysis of resistance to diamidines, biguanidines, and guanylhydrazones. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998;42(2):475–477. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.2.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schumacher MA, Miller MC, Grkovic S, Brown MH, Skurray RA, Brennan RG. Structural Mechanisms of QacR Induction and Multidrug Recognition. Science. 2001;294:2158–2163. doi: 10.1126/science.1066020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tenover FC, McDougal LK, Goering RV, Killgore G, Projan SJ, Patel JB, Dunman PM. Characterization of a Strain of Community-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Widely Disseminated in the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006;44:108–118. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.1.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fey PD, Saı B, Rupp ME, Hinrichs SH, Boxrud DJ, Davis CC, Kreiswirth BN, Schlievert PM. Comparative Molecular Analysis of Community- or Hospital-Acquired Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47(1):196–203. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.1.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang H, Flynn NM, King JH, Monchaud C, Morita M, Cohen SH. Comparisons of Community-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus ( MRSA ) and Hospital-Associated MSRA Infections in Sacramento , California. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006;44(7):2423–2427. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00254-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rudkin JK, Edwards AM, Bowden MG, Brown EL, Pozzi C, Waters EM, Chan WC, Williams P, Gara JPO, Massey RC. Methicillin Resistance Reduces the Virulence of Staphylococcus aureus by Interfering With the agr Quorum Sensing System. J. Infect. Dis. 2012;205:798–806. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vitko NP, Richardson AR, Carolina N. Laboratory Maintenance of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus ( MRSA ) Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. 2013 Feb 1–14; doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc09c02s28. No. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joyce MD, Jennings MC, Santiago CN, Fletcher MH, Wuest WM, Minbiole KP. Natural product-derived quaternary ammonium compounds with potent antimicrobial activity. J. Antibiot. 2016;69(4):344–347. doi: 10.1038/ja.2015.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitchell MA, Iannetta AA, Jennings MC, Fletcher MH, Wuest WM, Minbiole KPC. Scaffold-Hopping of Multicationic Amphiphiles Yields Three New Classes of Antimicrobials. ChemBioChem. 2015;16(16):2299–2303. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201500381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forman ME, Fletcher MH, Jennings MC, Duggan SM, Minbiole KPC, Wuest WM. Structure-Resistance Relationships: Interrogating Antiseptic Resistance in Bacteria with Multicationic Quaternary Ammonium Dyes. ChemMedChem. 2016;11(9):958–962. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201600095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huigens RW, Abouelhassan Y, Garrison AT. Combination Therapy for Treating Infectious Diseases. WO 2016/154051 A1. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frempong-Manso E, Raygada JL, DeMarco CE, Seo SM, Kaatz GW. Inability of a reserpine-based screen to identify strains overexpressing efflux pump genes in clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2009;33(4):360–363. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braoudaki M, Hilton AC. Mechanisms of resistance in Salmonella enterica adapted to erythromycin, benzalkonium chloride and triclosan. Int.. Antimicrob. Agents. 2005;25:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu D, Li Y, Shamim Hasan Zahid M, Yamasaki S, Shi L, Li J rong, Yan H. Benzalkonium chloride and heavy-metal tolerance in Listeria monocytogenes from retail foods. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2014;190:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2014.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fuentes DE, Navarro CA, Tantaleán JC, Araya MA, Saavedra CP, Pérez JM, Calderón IL, Youderian PA, Mora GC, Vásquez CC. The product of the qacC gene of Staphylococcus epidermidis CH mediates resistance to β-lactam antibiotics in Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Res. Microbiol. 2005;156(4):472–477. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Costa SS, Falcao C, Viveiros M, Machado D, Martins M, Melo-Cristino J, Amaral L, Couto I. Exploring the contribution of efflux on the resistance to fluoroquinolones in clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:241–253. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2013.0058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sgolastra F, Minter LM, Osborne BA, Tew GN. Importance of sequence specific hydrophobicity in synthetic protein transduction domain mimics. Biomacromolecules. 2014;15(3):812–820. doi: 10.1021/bm401634r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]