Abstract

Background

The utilisation of available cross-European data for secondary data analyses on physical activity, sedentary behaviours and their underlying determinants may benefit from the wide variation that exists across Europe in terms of these behaviours and their determinants. Such reuse of existing data for further research requires Findable; Accessible; Interoperable; Reusable (FAIR) data management and stewardship. We here describe the inventory and development of a comprehensive European dataset compendium and the process towards cross-European secondary data analyses of pooled data on physical activity, sedentary behaviour and their correlates across the life course.

Methods

A five-step methodology was followed by the European Determinants of Diet and Physical Activity (DEDIPAC) Knowledge Hub, covering the (1) identification of relevant datasets across Europe, (2) development of a compendium including details on the design, study population, measures and level of accessibility of data from each study, (3) definition of key topics and approaches for secondary analyses, (4) process of gaining access to datasets and (5) pooling and harmonisation of the data and the development of a data harmonisation platform.

Results

A total of 114 unique datasets were found for inclusion within the DEDIPAC compendium. Of these datasets, 14 were eventually obtained and reused to address 10 exemplar research questions. The DEDIPAC data harmonisation platform proved to be useful for pooling, but in general, harmonisation was often restricted to just a few core (crude) outcome variables and some individual-level sociodemographic correlates of these behaviours.

Conclusions

Obtaining, pooling and harmonising data for secondary data analyses proved to be difficult and sometimes even impossible. Compliance to FAIR data management and stewardship principles currently appears to be limited for research in the field of physical activity and sedentary behaviour. We discuss some of the reasons why this might be the case and present recommendations based on our experience.

Keywords: epidemiology, preventive medicine, public health

Strengths and limitations.

We applied the Findable; Accessible; Interoperable; Reusable (FAIR) principles to provide guidance in the discovery and reuse of data for further investigation.

We have identified more than 100 potentially relevant European datasets through our outlined search approaches.

It was possible to retrieve the metadata from these datasets on the types of variables, age groups under study, study design, measurement instruments used, time frame, etc.

Limited potential for reuse has been noted and this highlights the immediate need to manage future data collection within Europe using the FAIR principles.

More consistent data collection methodologies among the scientific community should be promoted as the variation in assessment methods and operationalisation of outcome variables across current European studies hampered data harmonisation.

Background

Low levels of physical activity and high levels of sedentary behaviour (too much sitting) are recognised as important risk factors for non-communicable diseases (NCDs) across Europe.1–5 These unhealthy behaviours put stress on societies as the burden of NCDs increases among Europe’s ageing population.6 Physical activity and sedentary behaviours are influenced by a wide range of individual-level and contextual factors.7–13 Apart from some prominent emerging influencing factors that stand out—such as injuries—the contribution of most determinants of sedentary behaviour and physical activity patterns may only be relevant for some people, in interaction with other factors, in some places and under certain circumstances. In other words, such behavioural determinants consist of a combination of individual and contextual factors that may be at the group or individual level and may mediate and moderate each other. This makes the identification of target factors for policy actions or behavioural interventions challenging. Especially, the more distal or ‘upstream’ behavioural determinants—such as factors in the built or social environments that support or hinder people to be active or sedentary—are often nuanced and hard to identify.11–14 Sophisticated methods are required for identifying these, using adequately powered data with sufficient variance in physical activity or sedentary behaviours as well as their underlying factors. Gathering such data is a costly endeavour and research funders are increasingly emphasising the importance of data sharing and secondary analysis of (often publicly funded) datasets as a means to maximise the research potential, increase power and variation of existing resources and provide greater returns on research investments.15–18

To address this challenge, one of the aims of the European Determinants of Diet and Physical Activity (DEDIPAC) Knowledge Hub was to explore the interrelations between correlates and determinants of physical activity and sedentary behaviours in and across European populations through secondary data analyses, using state-of-the-art statistical methods.19 One of the important drivers for establishing the Knowledge Hub was to enable comprehensive and large-scale research using the wide variation in exposures and outcomes that exist across Europe and to make use of the scattered and sometimes overlapping research that is conducted across its member states.

Utilising existing cross-European data for secondary data analyses potentially benefits from the wide variety in levels of physical activity and sedentary behaviour and their determinants across the continent.20–24 Although comparable, objectively measured data are currently lacking, there are indications that adults in northern European countries engage in more sitting time than in countries in the south of Europe20 and that some southern European countries generally appear to be among the less physically active countries.22 24 Analysing combined (ie, pooled) datasets in which the variables are matched (ie, harmonised) is a way to increase statistical power, the representativeness of wider populations and variation in outcomes or correlates of interest. In turn, increasing the power allows for mediation and moderation analyses and subsequent stratified (subgroup) analyses. Also the reanalysis of previously collected data using contemporary statistical techniques is possible. Such retrospective pooling often requires a data harmonisation process in which similar variables across multiple datasets are made compatible.25 The process of pooling datasets and harmonising the variables can be facilitated by data harmonisation platforms (DHPs). Examples of decentralised and centralised DHPs that were developed to support the pooling, harmonisation and analyses in epidemiological research include the BioSHaRE-EU,26 the Harvard Dataverse27 (both decentralised) and ICAD28 and POLARIS29 (both centralised).

Within the numerous organisations and research institutes—inside as well as outside the DEDIPAC consortium—there is a wealth of data on physical activity, sedentary behaviours and their potential individual and contextual correlates, predictors and determinants. Many of these datasets may have strong potential for secondary data analyses if these data become available. It is, however, unclear whether and how these data are distributed across Europe, to what extent these datasets comply to the Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable (FAIR)30 principles for data management and data stewardship and whether they indeed have the potential to be used in secondary data analyses of behavioural correlates across the life course.

In this paper, we set out a stepwise process towards cross-European data analyses of physical activity, sedentary behaviour and their correlates across the life course. We describe the inventory and development of a comprehensive European dataset compendium as well as the DEDIPAC DHP and discuss to what extend behavioural physical activity and sedentary behaviour research complies to FAIR principles and can be used for secondary data analyses.

Methods

The FAIR principles suggest that each data resource, associated metadata and complementary files should be registered or indexed in a searchable resource, so that they can be located (‘Findable); they should provide relevant metadata from these datasets, for instance, on the types of variables, age groups under study, study design, measurement instruments used, time frame, etc (‘Accessible’); they should be ‘Interoperable’ and thus use a consistent data format and taxonomy for knowledge representation and finally, they should be ‘Reusable’, that is, made available.30

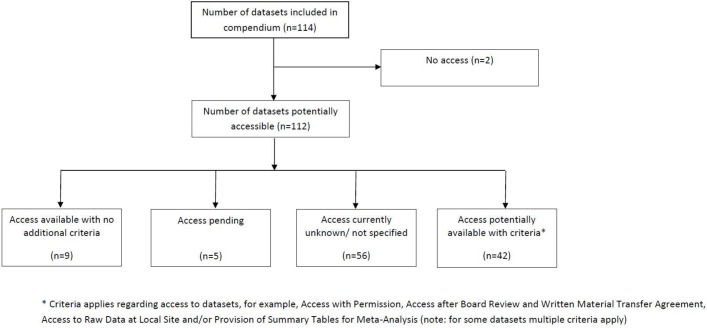

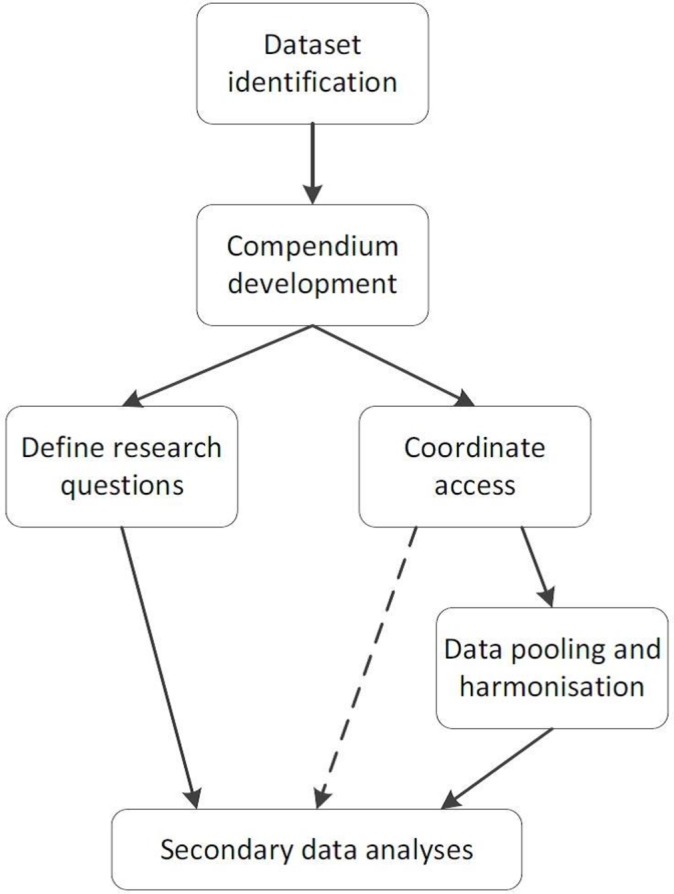

The DEDIPAC secondary data analysis plan followed a five-step approach including: (1) the identification of relevant datasets, (2) the development of a dataset compendium, (3) the clarification of key topics and approaches for analyses, (4) gaining access to datasets and (5) pooling of datasets and variable harmonisation. These steps are depicted in figure 1 and described in further detail below.

Figure 1.

Schematic outline of the stepwise approach towards secondary data analyses.

Identification of relevant European datasets

A relevant European dataset was defined as a dataset collected during an ongoing or recently (≤10 years) completed observational or intervention study focusing on physical activity and/or sedentary behaviour and its potential individual and/or contextual correlates. In addition, further inclusion criteria were formulated as follows: (1) participants had to be aged 6 years or older, (2) the observational or intervention study had a cross-sectional or longitudinal design, (3) the study was primarily conducted within the European Union and (4) the dataset consisted of quantitative data which could be either self-reported or objectively measured.

In the context of the DEDIPAC, relevant datasets were deemed ‘Findable’ if they were identified by: (1) a search of the Community Research and Development Information Services (CORDIS) project platform, which is the European Commission’s primary public repository and portal to disseminate information on all EU-funded research projects and their results in the broadest sense,31 (2) an examination of existing recent reviews of the literature and noting the nature of datasets used and (3) activities of the DEDIPAC Knowledge Hub and expert consultation.

To develop and complement a compendium of relevant European datasets

In an attempt to enhance the findability of the relevant datasets for future searches, a detailed compendium was developed. The compendium is a database in which the following information was detailed: project name, contact person details, website URL (if any), brief description of project, relevant publications, nations involved, sample size, gender, age, physical activity and sedentary behaviour and correlate measurement, indices of inequality/ethnic minorities and level of reusability. This information was gathered from publically available resources. The custodians of the datasets mentioned in the compendium were then approached and asked whether the information was correct and, in some cases, if they could provide additional details. Furthermore, they were asked for their permission to include their project and the project details in the compendium, which would be made accessible to the wider research community and to indicate the level of accessibility for secondary data analysis. The initial willingness of dataset owners to provide the data for reuse was listed in the compendium. This feedback provided some insights into the degree of challenge that would exist in achieving access to targeted datasets.

To define key topics and approaches for analyses

A number of research questions were formulated by the DEDIPAC consortium to assess the potential for secondary data analyses of the identified datasets. We aimed to add to the current state of knowledge as recently systematically summarised11–13 and informed by the DEDIPAC frameworks on determinants of sedentary behaviour32 and physical activity. The formulation of research questions was based on three distinct approaches: (1) clarify linkages of clusters and systems identified in the frameworks, (2) differentiate and nuance correlates of the two behaviours and (3) begin to fill knowledge gaps in determinant research. An expression of interest (EoI) statement was requested from DEDIPAC members that were interested in addressing one or more research questions. In addition to a clearly defined research question, the EoI included details of the target population, the project hypothesis, target dataset(s), independent and dependent variables, anticipated data harmonisation approach and the foreseen statistical analysis. To assist in this latter step, a 2-day statistical analysis workshop was organised in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, specifically focused on challenges of conducting secondary data analysis, handling pooling and harmonisation issues and to provide support on advanced statistical techniques (eg, Bayesian analyses, mediation/moderation analyses and handling missing data).

To coordinate access to target datasets

FAIR principles suggest that in order to ensure that existing and future data are accessible and reusable, specific requirements are in place, such as a common and easily shared data format, a common taxonomy, detailed metadata and a data access protocol with a clearly defined data usage licence. Implicit in these requirements is a pathway to or existing ethical approval to share data, safe and secure technologies to transfer data or facilitate remote access and analysis of data and detailed data dictionaries that clearly define the methodologies used in data collection. In the context of the DEDIPAC project, dataset owners of the required/targeted datasets were contacted to assess the potential for accessing datasets and the timeframe and relevant procedure to gain access. After initial and informal consent was obtained, a formal and detailed request for data sharing was provided, including a draft data sharing agreement that covered legal issues, terms of data usage and co-authorships agreements. The precise purpose of the data was specified and a detailed list of variables was requested. After formal agreement, the required data were sent to the central data-managing centre of the data pooling taskforce. The relevant DEDIPAC partners then received these data for analysis after they signed a data sharing agreement for recipients. In the latter agreement, data-related issues such as access rights, use, liability, publication and intellectual property rights were formally agreed on.

Data pooling and harmonisation of variables

The exemplar projects used secondary data analysis on either (1) a single dataset or (2) pooled and harmonised data from multiple datasets. In the latter case, pooling and harmonising could be conducted manually in a statistical programme, or using the DEDIPAC DHP. The DEDIPAC DHP is a Microsoft Access based DHP that is based on a DHP developed for the POLARIS project—a project for individual patient data-meta analyses and thus fully dependent on data pooling and harmonisation.29 Within this platform, the original datasets are linked with a reference dataset containing all potentially relevant variables from all individual datasets. If the studies measured and reported the same construct in the same way (eg, self-reported total physical activity based on the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)-short and reported in minutes per day), these variables were linked to the same variable in the reference dataset. However, if there was a difference in terms of concepts (eg, total physical activity vs physical activity in leisure time), measurement (eg, self-reported vs objective measurements) or reporting (eg, minutes per day vs meeting recommendations), these variables were linked to different variables in the reference dataset. Thus, the reference dataset could contain multiple variables for a single construct. In a later step, the multiple versions of a variable could be integrated into a unified measurement scheme. This unified measurement scheme describes a set of variables that have been measured in a similar fashion across a number of datasets, thus having potential for harmonisation. Within DEDIPAC, this step involved the identification of specific variables across target datasets which could/would be harmonised and required detailed examination of procedures/methods used by each dataset. Through an iterative review process, by a consensus committee, an agreed approach to the actual harmonisation of the variables was found. The selection process required a balance between uniformity (eg, exact same question wording and data collection procedures, or using the same data processing standards and cut-points) and the acceptance of a certain level of heterogeneity across datasets (ie, slightly different wording or procedures). As an aspect of expert consensus and where possible an examination of the frequency and descriptive statistics of similar variables informed the potential for harmonisation. Sharing solutions for data harmonisation across research question groups, regular telephone conferences and shared guidance documents were important aspects of this step.

Results

Identified datasets and the DEDIPAC compendium

A total of 114 unique datasets were identified for inclusion within the DEDIPAC compendium (figure 2). The majority of datasets included in the compendium were found through the CORDIS project platform. Other datasets within the compendium were identified by experts as potentially relevant for inclusion. The compendium is accessible through https://www.dedipac.eu and builds on the present level of findability. Details on the accessibility of these datasets are included in figure 2. The specific aims for gathering data within each dataset varied, with the majority of included datasets falling under one or more of the following six categories:

development, delivery and evaluation of interventions (n=33);

national surveys, for example, household surveys (n=17);

national cohort studies (n=11);

assessment and development of policy and research strategies (n=8);

studies investigating the link between lifestyle/environmental factors and disease (n=7);

studies investigating relations and interactions between health behaviours and health (n=7).

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of accessibility to datasets.

The majority of research projects included in the compendium were funded through the European Commission or other European level (53%), with just under a quarter of the related datasets (23%) supported by national funding. Just under half of datasets included data collected in two or more European countries (47%), with the remainder targeted at individual European countries. The study designs employed within the datasets are summarised in table 1. In brief, 43 datasets focused on one stage of the life course only; children only (n=13), adolescents only (n=2), adults only (n=19) or older adults only (n=9). Other datasets targeted two or more stages of the life course; with adults and older adults (n=20) being the most frequently combined stages within datasets.

Table 1.

Nature of datasets included within the determinants of diet and physical activity compendium

| n (%) | |

| Cross-sectional | 41 (36) |

| Longitudinal (including cohort) | 17 (15) |

| Intervention | 18 (16) |

| Cross-sectional and longitudinal | 13 (11) |

| Cross-sectional and intervention | 7 (6) |

| Longitudinal and intervention | 2 (2) |

| Cross-sectional, longitudinal and intervention | 2 (2) |

| Not specified | 14 (12) |

| Total | 114 |

A range of measurement tools were employed across datasets to measure physical activity and/or sedentary behaviour (table 2). Approximately, 41% of datasets included within the compendium used self-report tools to assess physical activity, using questionnaire tools designed specifically for their dataset or other routinely used questionnaires. Within the datasets using self-report tools, 27 (57.4%) used a questionnaire specifically designed for that project, with 10 (21.3%) using the IPAQ. A smaller proportion of studies used self-report proxy measures (1.8%) or a combination of self-report and proxy measures (1.8%) to assess physical activity. Approximately, 21% of datasets used self-report tools to assess sedentary behaviour.

Table 2.

Methods used to assess physical activity and/or sedentary behaviour within datasets

| Physical activity* datasets |

Sedentary behaviour* datasets |

|||

| n | % | n | % | |

| Self-report | 47 | 41.2 | 24 | 21.1 |

| Tool specifically designed for study | 27 | 57.4 | 17 | 70.8 |

| IPAQ | 10 | 21.3 | 3 | 12.5 |

| PAQ-S | 1 | 2.1 | ||

| GPAQ | 2 | 4.3 | ||

| SQUASH | 3 | 6.4 | ||

| MAQ | 1 | 2.1 | ||

| LAPAQ | 1 | 2.1 | ||

| PAQ-A and IPAQ | 1 | 2.1 | ||

| IPAQ, RPAQ and EPIC-PAQ | 1 | 2.1 | 1 | 4.2 |

| Marshall questionnaire | 1 | 4.2 | ||

| AQuAA | 2 | 8.3 | ||

| Self-report (proxy) | 3 | 2.6 | 3 | 2.6 |

| Tool specifically designed for study | 3 | 100 | 3 | 100 |

| Self-report and proxy | 1 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.9 |

| Tool specifically designed for study | 1 | 100 | ||

| IPAQ | 1 | 100 | ||

| Objective | 24 | 21.1 | 5 | 4.4 |

| Sensors/smartphones | 5 | 20.8 | ||

| Accelerometer | 16 | 66.7 | 4 | 80 |

| Heart rate monitor | 1 | 4.2 | 1 | 20 |

| Multiple monitors† | 1 | 4.2 | ||

Note: some datasets may have used more than one method to assess physical activity and/or sedentary behaviour.

*Subcategory percentage calculation is a percentage of the total number of databases for each measurement method.

†SenseWear Armband, Kenz, Actigraph GT3X, Dynaport MiniMod.

AQuAA, Activity Questionnaire for Adults and Adolescents; EPIC-PAQ, EPIC Physical Activity Questionnaire; IPAQ, International Physical Activity Questionnaire; GPAQ, Global Physical Activity Questionnaire; LAPAQ, LASA Physical Activity Questionnaire; MAQ, Modifiable Activity Questionnaire; PAQ-A, Physical Activity Questionnaire for Adolescents; PAQ-S, Physical Activity Questionnaire for Schoolchildren; RPAQ, Recent Physical Activity Questionnaire; SQUASH, Short Questionnaire to assess health-enhancing physical activity

Only 24 datasets included physical activity (n=24) measured using objective tools, either as standalone or alongside subjective tools, for example, questionnaires. Within the datasets that included objective measures, accelerometers were used to assess physical activity within 16 datasets (66.7%), as well as sensors/smartphones (20.8%), heart rate monitors (4.2%) and multiple monitors, including sensors and accelerometers (4.2%). Sedentary behaviour was measured using objective tools in five of the datasets. Heart rate monitors were used to measure sedentary behaviour in one dataset, while accelerometers were used to assess sedentary behaviour in four datasets, either on their own (n=2) or in combination with subjective tools (n=2).

The number of datasets reporting factors associated with physical activity and sedentary behaviour are summarised in tables 3A,B with 46% measuring physical activity and 15% measuring sedentary behaviour. These datasets were analysed using the following categories; biological (eg, sex, gender, health status, ethnicity, etc), psychological (eg, intentions, attitudes, self-perception, satisfaction, etc), behavioural (eg, lifestyle habits, life events, past experiences, etc), physical environment (eg, access, neighbourhood walkability/safety, climate, etc), sociocultural (eg, peer and family support, social expectation, local/national identity, etc), economic (socioeconomic status, house ownership, etc) and policy related (eg, promotion initiatives, government policy existence and implementation, etc). Biological, behavioural and psychological determinants/correlates of physical activity were most frequently reported within included datasets (table 3A). Behavioural and biological determinants/correlates were also frequently reported sedentary behaviour determinants (table 3B).

Table 3A.

Breakdown of datasets reporting on physical activity correlates or determinants by stage of the life course (where applicable)

| Datasets including physical activity determinants (overall) | Biological | Psychological | Behavioural | Physical environmental | Sociocultural | Economic | Policy | |

| Children only | 8 | 6 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 3 |

| Adolescents only | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Adults only | 11 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Older adults only | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Children and adolescents | 5 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| All stages of life course | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Children, adults, older adults | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Adolescents, adults, older adults | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Adults and older adults | 11 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Children and adults | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Children, adolescents, adults | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Adolescents and adults | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 53 | 31 | 23 | 26 | 16 | 15 | 6 | 3 |

Table 3B.

Breakdown of datasets reporting on sedentary correlates or determinants by stage of the life course (where applicable)

| Datasets including sedentary behaviour determinants (overall) | Biological | Psychological | Behavioural | Physical environmental | Sociocultural | Economic | Policy | |

| Children only | 5 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Adults only | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Children and adolescents | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| All stages of life course | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Children, adults, older adults | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Adolescents, adults, older adults | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Adults and older adults | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Children, adolescents, adults | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 17 | 7 | 4 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 0 |

Key topics and approaches for analyses

The EoI process and subsequent refinement resulted in a list of 10 research questions that addressed determinants/correlates across the life course, had a balanced focus on physical activity, sedentary behaviour or both and required a variety of statistical approaches (eg, using Bayesian network modelling, Χ2 automatic interaction detection analysis,33 etc). Work teams around each research question were formed. A 3-day writing retreat was organised in Ghent, Belgium, to further define approaches, to progress specific questions as well as identify unresolved issues regarding the pooling and harmonisation process.

Reusability of target datasets

The metadata contained within the compendium provide details on the potential level of reusability and what conditions must be met to facilitate access to the datasets (figure 2). The compendium provides metadata for all included datasets, regardless of the level of reusability of the data.

Of all 114 identified datasets, 43 were deemed to have potential in answering the 10 exemplar questions posed and subsequently data access requests were made to the dataset owners. Of these, actually, 12 datasets were not accessible during the timeframe of the DEDIPAC project, 10 dataset owners did not respond to our request after a number of attempts and 20 datasets (47%) agreed that access was possible. At the time of analyses, data had been obtained from 14 dataset owners.

Data pooling and harmonisation

The dataset owners that agreed to participate transferred the variables outlined in the data request form. The pooling of these data broadly followed the FAIR principles for interoperability, to facilitate the pooling of data across non-cooperating resources. The data were transferred in a compatible electronic format (most often SPSS, sometimes SAS or STATA). Data were then transferred to SPSS V.22.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Armonk, New York, USA) and the original data was archived for backup purposes. The datasets were then distributed to those leading the analyses. Variables to be harmonised ranged from raw accelerometry data to summary data (eg, proportion of the population above a defined threshold). As a proof of concept, the DEDIPAC DHP was used for one research question. This comprised the pooling of two large datasets and the first simple harmonisation steps encompassed the alignment of gender, education coding, etc.

Discussion

There is an increasing emphasis on the potential utility of existing datasets as a resource to answer research questions. While there are obvious benefits in terms of increased power for statistical analysis, this new and evolving approach has a number of challenges. The DEDIPAC consortium sought, for the first time, to examine the potential for data pooling and secondary data analysis in the measurement and determinants of dietary, physical activity and sedentary behaviours. In doing so, DEDIPAC has developed a valuable compendium of datasets that make it possible to ascertain the scope and scale of European projects in this research domain. Whereas low levels of physical activity and too much sitting are causing health problems worldwide, the focus of this paper is on the European setting. Many of the issues encountered regarding data pooling are expected to be similar for other regions, but the potential for data pooling and secondary data analyses may also partly be different for studies conducted in and by researchers from other regions, for example, because of differences in rules and regulations regarding data sharing. Furthermore, the data pooling was conducted to further research into potential determinants of sedentary behaviour and physical activity and such determinants themselves may be (partly) different between regions of the world, for example, because of differences in affluence, infrastructure and cultural differences.

In our approach, we applied the FAIR principles to provide guidance in the discovery and reuse of data for further investigation. We have identified more than 100 potentially relevant European datasets through our outlined search approaches (‘Findability’). It was possible to retrieve the metadata from these datasets on the types of variables, age groups under study, study design, measurement instruments used, time frame, etc (‘Accessibility’). These metadata were systematically detailed in the DEDIPAC compendium in order to be ‘Interoperable’. These datasets were, and are, being used to address 10 exemplar research questions (‘Reusability’) via direct analyses, decentralised pooling and harmonisation of multiple datasets or centralised pooling and harmonisation using a DHP. Therefore, we can conclude that, as a proof-of-concept, it is possible to apply the FAIR principles and successfully undertake research projects using existing data.

However, along the way, we encountered a number of significant challenges that were specific to the elements of the FAIR principles, but we also faced issues that applied to the pooling, harmonising and/or analysing the secondary data. These issues should be carefully considered if data pooling and harmonisation are to become a more central aspect of pan-European data analysis.

First, data that does not exist is not possible to find. The inventory of data in the development of the compendium brought to light that the number of existing datasets that may be relevant for pooling, harmonising and secondary data analyses in this field of research was rather limited—or very well hidden. There were especially few current datasets that contained a wide set of variables (outcomes, independent variables, co-variables) to study behaviours and their underlying factors. Therefore, the DEDIPAC project has highlighted a dearth of data on the determinants of physical activity and sedentary behaviour and believe a pan-European cohort study with a focus on behavioural determinants is required to address this deficiency.

Second, while we have demonstrated that it is feasible to retrieve metadata from datasets, it often required repeated personal (e-mail) contact with dataset owners. In addition, and more importantly, the reusability of datasets was limited to the small number of datasets to which access was granted. In the timeframe of the DEDIPAC project, it was challenging and time consuming to pursue access to the datasets to address the 10 exemplar research questions and only 12% had provided access at the time of writing. In the future, different approaches may be required to encourage dataset owners to participate in pooled data analysis. The outcome of the DEDIPAC exemplar projects may provide the evidence of the benefits and limitations that would provide dataset owners with a more solid basis for engagement. It is also possible that funding agencies may mandate the sharing of publicly funded data. Therefore, a continued and open discussion of the merits and limitations of data pooling is necessary.

Third, and beyond FAIR, the harmonisation of core outcome measures under study (in most cases sedentary behaviour and physical activity) was often problematic. Across the included and accessible datasets, these outcomes were measured or operationalised in a variety of ways. The substantial variation in assessment methods and operationalisation of outcome variables across current European studies (as illustrated in table 2) not only hampered the practical harmonisation process, but also presented comparability issues, as estimations of physical activity and sedentary behaviour levels are known to differ based on the assessment method used.21–24

Fourth, next to harmonisation issues of core outcomes (physical activity and/or sedentary behaviour, in this context), our focus on determinants of physical activity and sedentary behaviours meant that individual-level and contextual—more upstream—factors were to be taken into account. It was possible to harmonise some of the core outcomes sometimes, and some key sociodemographic variables (eg, age, gender and educational background) could be harmonised. However, harmonisation of the behavioural determinants was rarely possible and important covariates even less so. Thus, pooling often implied that certain variables could not be taken into account if they were not measured across all included datasets or could not be harmonised. In our opinion, the different assessment methods impeded harmonisation.

Finally, the retrospective pooling and harmonisation of variables require a ‘flexible design’, since very few established studies have used identical collection methods and procedures.34 A flexible design means that various categories of a variable such as, for instance, education attainment are reduced to few, or even only two categories (eg, higher/lower education). Hence, putting data from respondents from different studies together in one dataset indeed increases the number of observations and the absolute power of observations, but the promise that smaller associations can be picked up is likely to be compromised. The added nuance sought for with pooling data may thus be undone or even reversed by the—often rough—recategorisation of variables during the harmonisation process. This may be prevented in prospective harmonisation efforts—where particular instruments, protocols and operationalisations are specified and aligned beforehand. Such prospective harmonisation is especially required in surveillance systems to monitor regional variations and temporal trends of health behaviours and health outcomes, although this is not often done.35 36 In fact, an important goal of DEDIPAC was to work towards harmonisation of measurement instruments to better enable and promote prospective data harmonisation.19

Conclusions

The DEDIPAC project has identified and compiled a large number of pan-European projects related to physical activity and sedentary behaviour. In the design and analysis of 10 exemplar projects, using a variety of approaches, we identified a number of challenges including (1) the limited availability of datasets that contain variables to examine the determinants of physical activity and sedentary behaviour, (2) the difficulty to establish communication with dataset owners or getting their agreement to share data for analysis and (3) a low harmonisation potential for the limited number of variables that were available, especially for the potential determinants further upstream. Compliance to FAIR data management and stewardship principles currently appears to be limited for research in the field of physical activity and sedentary behaviour. It is recognised that researchers should be facilitated, funded, requested or required (eg, by funding agencies) to share their data and comply to the FAIR principles.18 37 While recognising the importance of utilising existing data, it is equally, if not, more important to highlight the absence of data that would be needed to investigate in detail the determinants of these behaviours. Not complying to the FAIR principles will limit the reusability of relevant data. In turn, the lack of suitable data will severely limit the ability of research to understand and predict these behaviours and inform policy. A bigger, targeted and more standardised data collection is needed in order to maximise the potential of data pooling and harmonisation. Until then, there are only narrow margins for determinant research to build and harvest on previous work.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JL, HvdP, LC, SC, GC, JB and CMD conceived the study. FL and AC assisted in data collection. AL and JK redesigned the DEDIPAC data warehouse. JL drafted the manuscript and AL, FL, MDC, HvdP, DOG, AC, LC, JK, JMO, SC, GC, JB and CMD contributed to iterative revisions.

Funding: The preparation of this paper was supported by the DEterminants of DIet and Physical ACtivity (DEDIPAC) knowledge hub. This work is supported by the Joint Programming Initiative ‘Healthy Diet for a Healthy Life’. The funding agencies supporting this work are: Belgium: Research Foundation, Flanders; France: Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (INRA); Germany: Federal Ministry of Education and Research; Italy: Ministry of Education, University and Research (DEDIPAC F.S. 02.15.02 COD. B84G14000040008; CDR2.PRIN 2010/11 COD. 2010KL2Y73_003)/Ministry of Agriculture Food and Forestry Policies; Ireland: The Health Research Board (HRB); The Netherlands: The Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw); UK: The Medical Research Council (MRC).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data may be obtained from the authors for academic purposes.

References

- 1. WHO. Physical activity factsheet N°385. Reviewed Jun, 2016.

- 2. Wilmot EG, Edwardson CL, Achana FA, et al. . Sedentary time in adults and the association with diabetes, cardiovascular disease and death: systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia 2012;55:2895–905. 10.1007/s00125-012-2677-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Grøntved A, Hu FB. Television viewing and risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2011;305:2448–55. 10.1001/jama.2011.812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Biswas A, Oh PI, Faulkner GE, et al. . Sedentary time and its association with risk for disease incidence, mortality, and hospitalization in adults. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:123 10.7326/M14-1651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, et al. . Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet 2012;380:219–29. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. WHO, National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health. Global health and aging. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bauman AE, Reis RS, Sallis JF, et al. . Correlates of physical activity: why are some people physically active and others not? Lancet 2012;380:258–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60735-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Marques A, Martins J, Peralta M, et al. . European adults’ physical activity socio-demographic correlates: a cross-sectional study from the European Social Survey. PeerJ 2016;4:e2066 10.7717/peerj.2066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carlin A, Perchoux C, Puggina A, et al. . A life course examination of the physical environmental determinants of physical activity behaviour: a ‘Determinants of Diet and Physical Activity’ (DEDIPAC) umbrella systematic literature review. PLoS One 2017;12:e0182083 10.1371/journal.pone.0182083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Condello G, Puggina A, Aleksovska K, et al. . Behavioral determinants of physical activity across the life course: a “DEterminants of DIet and Physical ACtivity” (DEDIPAC) umbrella systematic literature review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2017;14:58 10.1186/s12966-017-0510-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stierlin AS, De Lepeleere S, Cardon G, et al. . A systematic review of determinants of sedentary behaviour in youth: a DEDIPAC-study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2015;12:133 10.1186/s12966-015-0291-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chastin SF, Buck C, Freiberger E, et al. . Systematic literature review of determinants of sedentary behaviour in older adults: a DEDIPAC study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2015;12:127 10.1186/s12966-015-0292-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. O’Donoghue G, Perchoux C, Mensah K, et al. . A systematic review of correlates of sedentary behaviour in adults aged 18-65 years: a socio-ecological approach. BMC Public Health 2016;16:163 10.1186/s12889-016-2841-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lakerveld J, Mackenbach J. The upstream determinants of adult obesity. Obes Facts 2017;10:216–22. 10.1159/000471489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Doiron D, Burton P, Marcon Y, et al. . Data harmonization and federated analysis of population-based studies: the BioSHaRE project. Emerg Themes Epidemiol 2013;10:12 10.1186/1742-7622-10-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pisani E, AbouZahr C. Sharing health data: good intentions are not enough. Bull World Health Organ 2010;88:462–6. 10.2471/BLT.09.074393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schofield PN, Eppig J, Huala E, et al. . Sustaining the Data and Bioresource Commons. Science 2010;330:592–3. 10.1126/science.1191506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Piwowar HA, Becich MJ, Bilofsky H, et al. . Towards a data sharing culture: recommendations for leadership from academic health centers. PLoS Med 2008;5:e183–9. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lakerveld J, van der Ploeg HP, Kroeze W, et al. . Towards the integration and development of a cross-European research network and infrastructure: the DEterminants of DIet and Physical ACtivity (DEDIPAC) Knowledge Hub. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2014;11:143 10.1186/s12966-014-0143-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Loyen A, van der Ploeg HP, Bauman A, et al. . European sitting championship: prevalence and correlates of self-reported sitting time in the 28 European union member states. PLoS One 2016;11:e0149320 10.1371/journal.pone.0149320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Loyen A, Verloigne M, Van Hecke L, et al. . Variation in population levels of sedentary time in European adults according to cross-European studies: a systematic literature review within DEDIPAC. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2016;13:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Van Hecke L, Loyen A, Verloigne M, et al. . Variation in population levels of physical activity in European children and adolescents according to cross-European studies: a systematic literature review within DEDIPAC. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2016;13:1–22. 10.1186/s12966-016-0396-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Verloigne M, Loyen A, Van Hecke L, et al. . Variation in population levels of sedentary time in European children and adolescents according to cross-European studies: a systematic literature review within DEDIPAC. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2016;13:1–30. 10.1186/s12966-016-0395-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Loyen A, Van Hecke L, Verloigne M, et al. . Variation in population levels of physical activity in European adults according to cross-European studies: a systematic literature review within DEDIPAC. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2016;13:72 10.1186/s12966-016-0398-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Granda P, Blasczyk E, harmonization D. guidelines for best practice in cross-cultural surveys. MI Surv Res Centre, Inst Soc Res Univ Michigan 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gaye A, Marcon Y, Isaeva J, et al. . DataSHIELD: taking the analysis to the data, not the data to the analysis. Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:1929–44. 10.1093/ije/dyu188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Crosas M. The dataverse network®: an open-source application for sharing, discovering and preserving data. D-Lib Mag 2011;17:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sherar LB, Griew P, Esliger DW, et al. . International children’s accelerometry database (ICAD): design and methods. BMC Public Health 2011;11:485 10.1186/1471-2458-11-485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Buffart LM, Kalter J, Chinapaw MJ, et al. . Predicting optimal cancer rehabIlitation and supportive care (POLARIS): rationale and design for meta-analyses of individual patient data of randomized controlled trials that evaluate the effect of physical activity and psychosocial interventions on health-related quality of life in cancer survivors. Syst Rev 2013;2:1–9. 10.1186/2046-4053-2-75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wilkinson MD, Dumontier M, Aalbersberg IJ, et al. . The FAIR guiding principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci Data 2016;3:160018 10.1038/sdata.2016.18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. European Commission. CORDIS (Community Research and Development Information Services).

- 32. Chastin SFM, De Craemer M, Lien N, et al. . The SOS-framework (Systems of Sedentary behaviours): an international consensus transdisciplinary framework and research priorities for the study of determinants of sedentary behaviour and policy across the life course: a DEDIPAC study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2016;13:83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lakerveld J, Loyen A, Schotman N, et al. . Sitting too much: a hierarchy of socio-demographic correlates. Prev Med 2017;101:77–83. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Doiron D, Raina P, Raina P, et al. . Facilitating collaborative research: Implementing a platform supporting data harmonization and pooling. Nor Epidemiol 2012;21:221–4. 10.5324/nje.v21i2.1497 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bel-Serrat S, Huybrechts I, Thumann BF, et al. . Inventory of surveillance systems assessing dietary, physical activity and sedentary behaviours in Europe: a DEDIPAC study. Eur J Public Health 2017;56:S25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brug J, van der Ploeg HP, Loyen A, et al. . Towards better knowledge of the causes of the causes: lessons learned from European Joint Programming in research on Determinants of Diet and Physical Activity (DEDIPAC).

- 37. Genbank A. Let data speak to data. Nature 2005;438:531 10.1038/438531a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.