Abstract

Background

Subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH) has been associated with increased carotid intima-media thickness (C-IMT) in recent studies, but the effects of levothyroxine (L-T4) therapy on C-IMT in SCH patients are still controversial.

Aim

To evaluate the effect of L-T4 therapy on endothelial function as determined by C-IMT in patients with SCH.

Methods

BeforeJuly 2016, we searched the PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library and Google Scholar databases, selecting published randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and self-controlled trials for the meta-analysis.

Results

Three RCTs with 117 patients were considered appropriate for the meta-analysis. The results of the meta-analysis indicated that L-T4 significantly decreased the development of C-IMT (weighted mean difference (WMD) −0.05 mm, 95% CI −0.08 to –0.01 mm; p=0.025). We also analysed nine studies (self-controlled trials) with 247 patients and extracted the IMT of SCH patients before and after L-T4 treatment. After L-T4 therapy, the pooled estimate of the WMD of decreased C-IMT was −0.04 mm (95% CI −0.07 to –0.02 mm; p=0.05). Subgroup analysis showed that L-T4 therapy was associated with a decrease in C-IMT among patients of mixed genders (WMD −0.03 mm, 95% CI −0.06 to –0.01 mm; p=0.145). L-T4 therapy was associated with a decrease in C-IMT among female patients (WMD −0.07 mm, 95% CI −0.14 to –0.01; p=0.186). Longer treatment (>6 months) also resulted in a significant decrease in C-IMT (WMD −0.05 mm, 95% CI −0.08 to –0.02; p=0.335).

Conclusion

This meta-analysis indicates that L-T4 treatment of SCH patients can reduce C-IMT, possibly as a result of the reduction of total cholesterol, triglyceride, low density lipoprotein, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, lipoprotein(a), and flow-mediated dilatation. Decreased C-IMT was observed in SCH patients after long-term (>6 months) L-T4 treatment. RCTs with larger samples are needed to verify these observations.

Keywords: subclinical hypothyroidism, carotid intima-media thickness, thyroxin, cardiovascular risk

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Strong quality evidence on the effect of levothyroxine (L-T4) therapy in patients from the original studies in the literature, which required the use of different methods of statistical analysis and quality evaluation. Due to differing heterogeneity, we adopted a different effect model. This embodies the rigour of methodology.

We analysed other metabolic parameters to determine the effect of L-T4 therapy in SCH.

The number of studies included was small, and the overall population of these trials was not large. Meta-analysis has moderate heterogeneity. It was difficult to assess the effect of potential publication bias, mainly due to the previous two factors.

We did not perform subgroup analysis on the level of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) (the cutoff value is 10 mU/mL to distinguish mild from severe SCH) because the original studies did not perform analyses according to TSH levels.

We did not perform subgroup analysis by mean age (>65 or <65 years) because the mean age of all the participants was <65 years.

Introduction

Subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH) is characterised by a normal range of free thyroxin concentrations together with increased serum thyroxin (thyroid stimulating hormone, TSH) levels. Recently, SCH was found in 5–10% of the general population and 6–10% of women (approximately 15% was found in women >60 years old), while the incidence in males was 2.4–3%.1 Although SCH is frequently asymptomatic, approximately 30% of patients have symptoms indicative of thyroid hormone deficiency.2 3 However, the clinical significance and therapeutic strategies of SCH are controversial.

Carotid intima-media thickness (C-IMT) is a generally acknowledged measure of subclinical atherosclerotic alterations. It is increasingly used to evaluate vascular function in clinical analyses to assess the efficacy of interventions that reduce atherosclerosis and related diseases.4 This parameter is listed in the European guidelines for prophylaxis of cardiovascular disease, and 0.9 mm is the threshold value for C-IMT. Progression of atherosclerosis is indicated when the value of C-IMT is over the threshold.

A meta-analysis involving eight studies with 3602 participants found a relationship between SCH and C-IMT, especially when TSH is >10.0 mIU/L.5 Levothyroxine (L-T4) replacement therapy should be used to treat patients with clinical hypothyroidism; however, the treatment of SCH is complex. Several placebo-controlled studies have shown the beneficial effects of L-T4 therapy on early atherosclerotic alterations and cardiovascular hazard in patients with SCH.6 7 Recently, in a large-scale retrospective cohort study examining the efficacy of L-T4 replacement on cardiovascular mortality, myocardial infarction and all-cause death, no beneficial effects in patients with SCH were found, except for patients <65 years old.8 The purpose of the current study was to evaluate the effect of L-T4 therapy on endothelial function as evaluated by C-IMT in patients with SCH.

Methods

Search strategy

Studies published in English were found in the Embase, PubMed, Google Scholar and Cochrane Library electronic databanks up to June 2016. We identified studies that measured IMT in patients with SCH before and after treatment with L-T4. Studies were identified and evaluated by two authors (TZ, BC) using the following words (the following is an example for PubMed): (‘hypothyroidism’(MeSH Terms) OR ‘hypothyroidism’(All Fields)) OR (subclinical(All Fields) AND (‘hypothyroidism’(MeSH Terms) OR ‘hypothyroidism’(All Fields)) AND (‘thyroxine’(MeSH Terms) OR ‘thyroxine’(All Fields)) AND (‘carotid intima-media thickness’(MeSH Terms) OR (‘carotid’(All Fields) AND ‘intima-media’(All Fields) AND ‘thickness’(All Fields)) OR ‘carotid intima-media thickness’(All Fields) OR (‘carotid’(All Fields) AND ‘intima’(All Fields) AND ‘media’(All Fields) AND ‘thickness’(All Fields)) OR (‘carotid intima media thickness’(All Fields)). For a thorough review of the literature, we searched more studies by browsing the references of the identified reports and review articles.

Criteria for study selection

Subjects with SCH have standard free thyroxin levels and increased TSH levels. There is still controversy about the TSH reference interval; several reviews have proposed a TSH upper cut-off between 4.5 and 5.0 mIU/L,9 10 but some experts suggest that peak TSH should be decreased to 2.5–3.0 mIU/L. Because there are no consistent conclusions, no specific TSH cut-off was used to define SCH, but all articles had a cut-off point from 3.6 to 5.5 mIU/L. To be included, a study had to satisfy the following conditions: (1) reported SCH defined based on a thyroid function test (normal free T4 and increased TSH); (2) defined as a randomised controlled trial (RCT), which compared C-IMT in SCH patients in a L-T4 treatment and control group, or a self-controlled trial, which compared C-IMT values of a patient with SCH before and after L-T4 replacement therapy

Study selection

Two investigators independently screened both abstracts and titles of the studies, and the studies were excluded when they did not conform to the inclusion criteria or they accorded with the exclusion criteria. Two investigators independently extracted data from the papers. If there was disagreement, a third reviewer was asked for advice. Discrepancies were solved by unanimous agreement.

Data extraction

The following information is contained in the data extraction table: (1) author; (2) year of publication; (3) region; (4) sample size; (5) sample gender; (6) mean age of the cohort; (7) definition of SCH; (8) duration of SCH; (9) SCH detection method; (10) mean L-T4 dosage; (11) duration of treatment; (12) thyroid function after treatment; (13) IMT assessment; (14) IMT values (mean and SD) before and after treatment with the corresponding treatment method.

Assessment of study quality

The quality of non-randomised studies was evaluated using the MINORS method,11 which is based on the following items: a stated aim of the study; inclusion of consecutive patients; prospective collection of data; endpoint appropriate to the study aim; unbiased evaluation of endpoints; follow-up period appropriate to the major endpoint; and loss to follow-up not exceeding 5%.

Methodological quality of the included RCTs was assessed using the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Review of Interventions by several domains: generation of random sequence; allocation concealment; blinding; incomplete outcome date addressed; free of selective reporting; free of other bias.

Statistical analysis

We represented the results as weighted mean differences (WMDs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for continuous variables. For continuous outcomes, if all reports had uniform units of measurement (expressed as mm), we showed the WMD and 95% CIs as the results. We evaluated statistical heterogeneity across the studies using the Cochrane’s Q test (p<0.1 was statistically significant) and the I2 test (I2 >50%: high heterogeneity; I2=25–50%: moderate heterogeneity; I2 <25%: low heterogeneity).12 In 2011, Kulinskaya et al suggested a method based on fractional degrees of freedom (df) which substantially improves the original Χ2 distribution with s-1 df, where this is the number of studies included in the meta-analysis.13 The pooled effect size was assessed with a random-effect model when significant statistically heterogeneity was present; in contrast, we also selected a fixed-effect model. A value of p<0.05 was considered significant. The weighting of WMD in a fixed-effect model is inverse variance. However, the weighting of WMD in a random-effect model is the D-L method (DerSimonian and Laired method).14 We assessed publication bias with Begg’s correlation test and Egger’s regression method.15 Sensitivity analysis was carried out for all papers in addition to the studies with boundary qualification. Pre-specified subgroup meta-analyses were performed to assess the between-study heterogeneity on the basis of the gender of participants (female or genders) and duration of treatment (>6 months or ≤6 months). Among nine included studies, three of them were RCTs and the remainder were self-controlled trials. We performed statistical analysis of three RCTs. The SCH treatment groups in three RCTs also had information on the C-IMT values in the SCH patients before and after treatment. We combined the SCH treatment groups of the RCTs with the other self-controlled trials to perform statistical analysis in order to fully reveal the effect of L-T4 treatment in SCH patients. Statistical analyses were performed with STATA 11 for Windows.

Results

Study selection

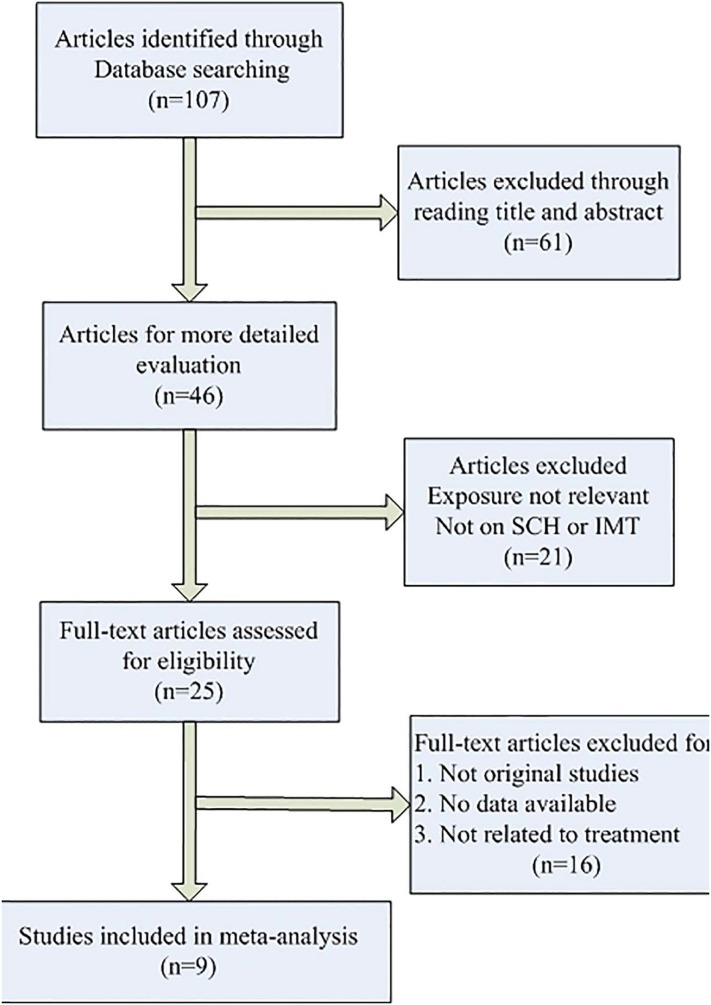

Three RCTs7 16 17 (57 patients treated with L-T4 and 60 included in the control group) were selected for the meta-analysis, with a total of 117 patients. A total of nine publications7 16–23 with 247 SCH patients measured the C-IMT before and after L-T4. We selected these studies from among 107 potentially related articles (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Process of study selection. IMT, intima-media thickness; SCH, subclinical hypothyroidism.

Baseline characteristics and study quality

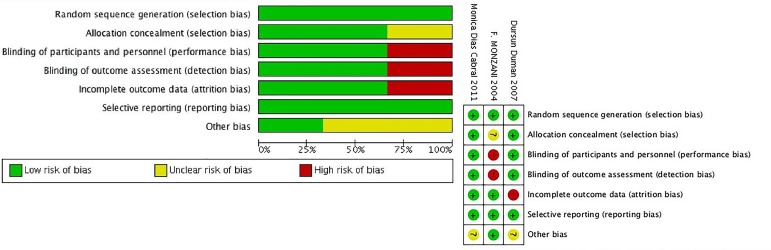

The baseline characteristics of the included trials are shown in table 1A,B. The duration of therapy with L–T4 ranged from 2 to 18 months, the patient count varied from 14 to 56 subjects, and the year of publication was from 2004 to 2016. Six trials included female and male patients, and the other three only examined female patients. Based on the type of original research, the methodological evaluation of study quality was different. We used MINORS to assess the quality of the self-controlled trials. In general, the included self-controlled trials were of moderate quality (table 1). The results of RCT quality are shown in figure 2.

Table 1.

Summary of the characteristics of the included studies

| (A) | |||||||||||

| Author/year | Sample size |

Region | Gender | Mean age (year) | Definition of SCH | SCH duration (months) |

L-T4 dosage (initial value) | Treatment duration (months) |

Thyroid function after treatment | CIMT (mm) (before/after) |

Quality score |

| Monzani | 23 | Italy | Mixed genders | 37±11 | TSH >3.6 mIU/L | At least 6 months | 25–75 μg/day | 10.5* | Normal | 0.76±0.14 | 12 |

| 2004 | 0.67±0.13 | ||||||||||

| Soo-Kyung | 28 | Korea | Mixed genders | 36.0±6.2 | TSH >5.5 mIU/L | Newly diagnosed | 67 µg/day† | 18† | Normal | 0.67±0.11 | 9 |

| 2009 | 0.60±0.10 | ||||||||||

| Monica | 14 | Brazil | Female | 43.4±9.8 | TSH >4.0 mIU/L | _ | 44.23±18.13 μg/day‡ | 12 | Normal | 0.66±0.11 | 10 |

| 2011 | 0.66±0.15 | ||||||||||

| Levent | 38 | Turkey | Mixed genders | 49.8±10.0 | TSH >5.0 mIU/L | At least 2 months | 101±27.46 µg/day§ | 6† | Normal | 0.64±0.13 | 11 |

| 2010 | 0.63±0.12 | ||||||||||

| Nasmi | 25 | Iran | Mixed genders | 35.9±7.6 | TSH >4.0 mIU/L | _ | 50 μg/day | 2 | Normal | 0.56±0.09 | 11 |

| 2016 | 0.57±0.08 | ||||||||||

| Ilknur | 56 | Turkey | Mixed genders | 41.3±14.5 | TSH >4.2 mIU/L | _ | 25–50 μg/day | _ | Normal | 0.533±0.112 | 12 |

| 2014 | 0.507±0.126 | ||||||||||

| Dursun | 20 | Turkey | Female | 36±11 | TSH >4.2 mIU/L | Newly diagnosed | 25–100 μg/day | 5† | Normal | 0.65±0.09 | 12 |

| 2007 | 0.55±0.08 | ||||||||||

| Adrees | 20 | Ireland | Female | 50±9 | _ | At least 6 months | 100±30 μg/day§ | 18 | Normal | 0.82±0.2 | 10 |

| 2009 | 0.71±0.2 | ||||||||||

| Dilek | 23 | Turkey | Mixed genders | 35.2±10.7 | TSH >4.0 mIU/L | At least 6 months | _ | 6 | Normal | 0.51±0.09 | 11 |

| 2015 | 0.46±0.07 | ||||||||||

| (B) | |||||||||||

| Author | TSH assay | Carotid IMT assessment | |||||||||

| Monzani | Ultrasensitive immunoradiometric assay | Both the near and far wall of the right and left common carotid artery and carotid bifurcation (high-resolution ultrasonography) | |||||||||

| Soo-Kyung | Chemiluminescent immunometric assay | 20 mm proximal to the origin of the carotid bulb (high-resolution ultrasonographic system) | |||||||||

| Monica | Immunochemiluminescence | Both the near and far wall of the right and left common artery and the carotid bifurcation (high-resolution ultrasound imaging) | |||||||||

| Levent | Chemiluminescence immunometric assay | Approximately 1 cm segment from both the left and right CCA proximal and distal portions (ultrasonographic images) | |||||||||

| Nasmi | _ | Sonogram B-mode images | |||||||||

| Ilknur | Electrochemiluminescence immunoassays | Three arterial wall segments of the common carotid artery were measured bilaterally after imaging from a fixed lateral transducer angle and designated (high-resolution B-mode ultrasonography) | |||||||||

| Dursun | Immunoassay | Right and left extracranial carotid arteries: the CCA (1 cm proximal to the dilation of the carotid bulb), the bifurcation (the 1 cm segment proximal to the flow divider), and the internal carotid artery (the 1 cm segment in the internal branch distal to the flow divider)(high-resolution ultrasonography) | |||||||||

| Adrees | Chemiluminescent immunometric assay | 1 cm proximal to the carotid bulb when a satisfactory position was found (calibrated ultrasound machine) | |||||||||

| Dilek | _ | Ultrasound system | |||||||||

Age and C-IMT are expressed as mean±SD.

*Median.

†mean.

‡median±IQR.

§mean.

CCA, common carotid artery; CIMT, carotid intima-media thickness; L-T4, levothyroxine; SCH, subclinical hypothyroidism; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Figure 2.

Quality assessment of the included studies.

Progression of C-IMT in the follow-up and subgroup analysis

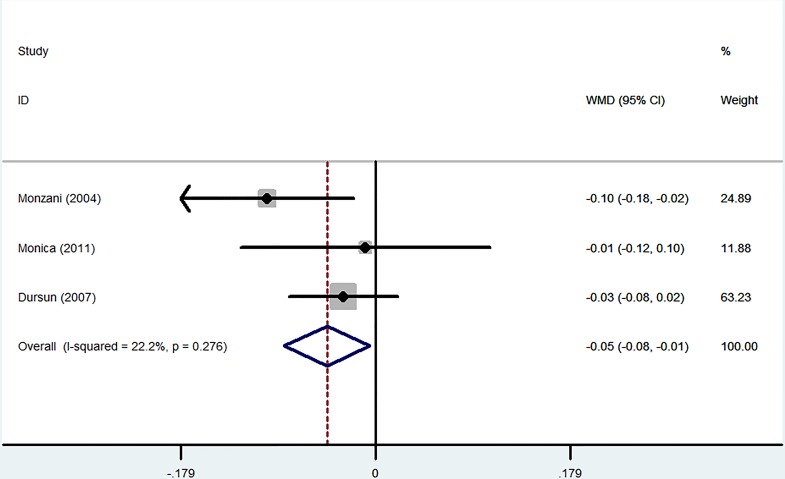

A total of three RCTs involving 117 patients were analysed. L-T4 treatment significantly decreased C-IMT progression in SCH patients (WMD −0.05 mm, 95% CI −0.08 to –0.01; p=0.025). The heterogeneity was very low (I2=22.2%) (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plots showing weighted mean differences (WMD, 95% CI) for improvement in carotid intima-media thickness (C-IMT) comparing L-T4 treatment to the control in a fixed effects model. X-axis: negative values equal improvement in C-IMT.

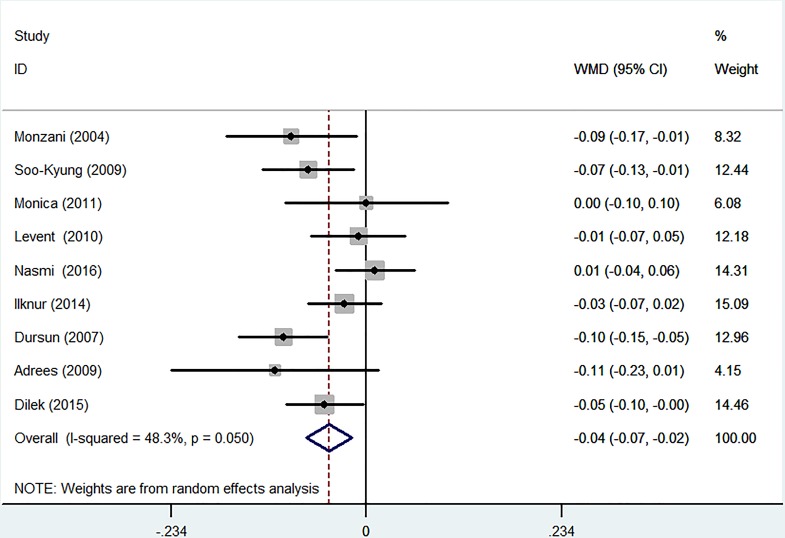

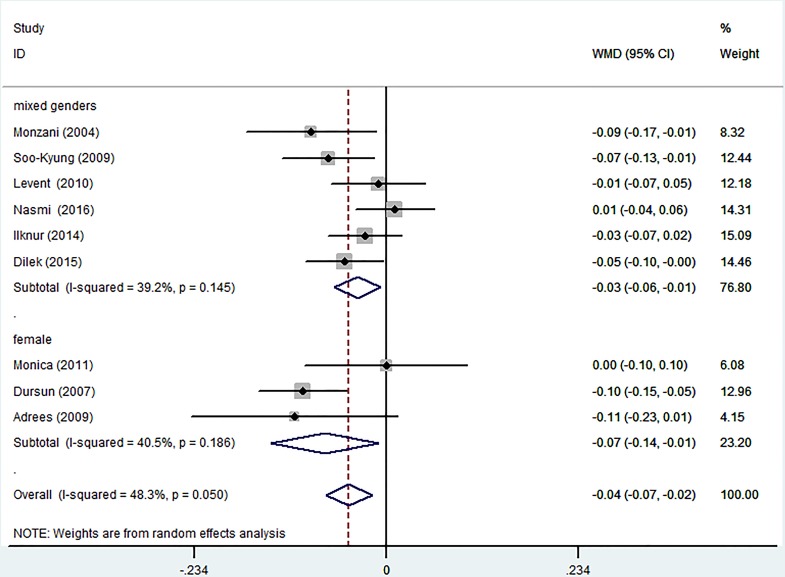

The nine self-controlled experiments compared the value of C-IMT before replacement and after treatment. After L-T4 therapy, the thyroid function of all patients was normalised from SCH, and then patient IMT was measured again. Because clinical heterogeneity was relatively high, we selected a random-effect model. L-T4 therapy was associated with a mild but significant decrease in the development of C-IMT (WMD −0.04 mm, 95% CI −0.07 to –0.02; p=0.050). The heterogeneity was moderate (I2=48.3%) (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Forest plots showing weighted mean differences (WMD, 95% CI) comparing the value of carotid intima–media thickness (C-IMT) before replacement and after treatment in a random-effect model. X-axis: negative values equal improvement in C-IMT.

Subgroup analyses stratified by gender revealed that L–T4 therapy caused a significant decrease in C-IMT among patients of mixed genders (WMD −0.03 mm, 95% CI −0.06 to –0.01; p=0.145). The outcomes showed moderate heterogeneity (I2=39.2%).

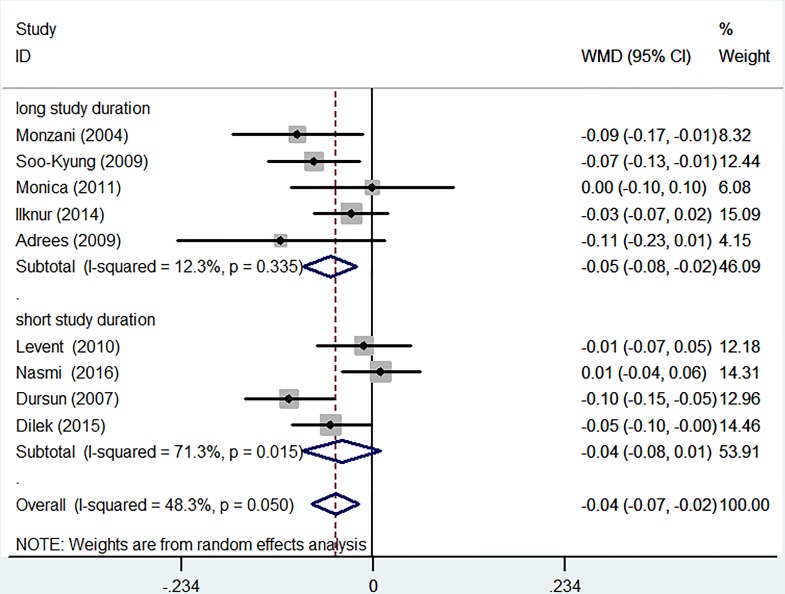

After L-T4 treatment, female participants with SCH displayed a significant reduction in C-IMT (WMD −0.07 mm, 95% CI −0.14 to –0.01; p=0.186). The heterogeneity was moderate (I2=40.5%) (figure 5). Subgroup analyses were performed using the duration of L-T4 replacement. Except for one report, all trials had information on the length of the therapy. There was a significant decrease in C-IMT in the patients with long-term (>6 months) treatment (WMD −0.05 mm, 95% CI −0.08 to –0.02; p=0.335). The outcome showed low heterogeneity (I2=12.3%). A non-significant reduction was found in C-IMT in the participants with short-term (≤6 months) replacement therapy (WMD −0.04 mm, 95% CI −0.08 to 0.01; p=0.015). The heterogeneity was high (I2=71.3%) (figure 6).

Figure 5.

Subgroup analyses of carotid intima-media thickness (C-IMT) changes based on gender in a random effects model. X-axis: negative values equal improvement in C-IMT. WMD, weighted mean difference.

Figure 6.

Subgroup analyses of carotid intima-media thickness (C-IMT) changes based on duration of levothyroxine (L-T4) replacement in a random effects model. X-axis: negative values equal improvement in C-IMT. Long study duration, duration of L-T4 replacement >6 months. Short study duration, duration of L-T4 replacement ≤6 months. WMD, weighted mean difference.

Changes in metabolic parameters

Table 2 indicates the changes in metabolic parameters from pre-replacement to post-treatment. L-T4 therapy was linked to significant reductions in total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), low density lipoprotein (LDL), systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), and lipoprotein(a) (LP(a)) and decreased flow-mediated dilatation (FMD). There were no significant changes in body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, high density lipoprotein (HDL), apolipoprotein A (ApoA), apolipoprotein B (ApoB) and glucose between the pre-treatment and post-therapy conditions.

Table 2.

Changes in metabolic parameters between pre-treatment and post-treatment

| Parameters | No. of patients | WMD (95% CI) | p Value |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 66 | −0.544 (-4.041 to 2.954) | 0.761 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 152 | −0.231 (-1.044 to 0.582) | 0.577 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 48 | 0.090 (-0.109 to 0.289) | 0.375 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 109 | −9.391 (-14.405 to -4.377) | <0.001 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 109 | −5.693 (-8.471 to -2.916) | <0.001 |

| TC (mg/dL) | 166 | −9.037 (-16.635 to -1.439) | 0.02 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 166 | −9.842 (-18.763 to -0.921) | 0.031 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 166 | −1.032 (-4.059 to 1.995) | 0.504 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 166 | −14.303 (-19.133 to -9.472) | <0.001 |

| FMD (%) | 39 | 3.962 (2.636 to 5.289) | <0.001 |

| ApoA (mg/dL) | 37 | −10.092 (-23.173 to 2.989) | 0.131 |

| ApoB (mg/dL) | 37 | −7.718 (-21.723 to 6.287) | 0.28 |

| LP(a) (mg/L) | 34 | −9.974 (-12.844 to -7.103) | <0.001 |

ApoA, apolipoprotein A; ApoB, apolipoprotein B; BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FMD, flow-mediated dilatation; HDL, high density lipoprotein; LDL, low density lipoprotein; Lp(a), lipoprotein(a); SBP, systolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; WMD, weighted mean difference.

Sensitivity and publication bias evaluation

We conducted sensitivity analyses by sequentially eliminating one study to probe the change in the total WMD and 95% CI of C-IMT. The results of three RCTs indicated no variation in the direction of WMD when each publication was removed (online supplementary figure 1). Neither Egger’s test (p=0.881) nor Begg’s test (p=0.602) of C-IMT in SCH manifested publication biases (online supplementary figure 2) and online supplementary figure 3). We also evaluate the sensitivity and publication bias of the nine self-controlled trials. The results showed that there was only a slight change in the WMD or 95% CI, and no change in the direction of WMD when any one study was omitted (online supplementary figure 4). Egger’s test (p=0.458) and Begg’s test (p=0.602) of C-IMT in SCH manifested publication biases (online supplementary figure 5 and online supplementary figure 6).

bmjopen-2017-016053supp001.pdf (3MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-016053supp002.pdf (2.2MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-016053supp003.pdf (4MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-016053supp004.pdf (5.1MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-016053supp005.pdf (2.3MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-016053supp006.pdf (4.1MB, pdf)

Discussion

This meta-analysis indicated that L-T4 has beneficial effects on the development of C-IMT. Decreased C-IMT was also observed with longer treatment (>6 months). L–T4 therapy of SCH participants also resulted in a significant reduction in TC, TG, LDL, SBP, DBP, LP(a), and FMD.

The American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines designated C-IMT along with coronary artery calcium (CAC) score as a class IIa recommendation for cardiovascular risk assessment in asymptomatic adults at intermediate risk of cardiovascular disease. For a 0.1 mm difference in C-IMT, the prospective risk of myocardial infarction increased from 10% to 15%, and the stroke risk increased from 13% to 18%.5 The result showed that C-IMT in SCH patients can be reversed by L-T4 replacement. The mechanism underlying the L-T4-mediated decrease in C-IMT has not been fully elucidated. TSH receptor (TSHR), hyperlipidaemia and blood pressure may contribute to this result.

In SCH, the increased TSH is the only prominent change, and increased TSH can bind with TSHR to perform its function. Balzan et al24 revealed that microvascular endothelial cells produce TSHR, which may help to elucidate this relationship. Recently, Tian et al25 published a study to identify the potential function of TSHR and showed that increased TSH aggravated endothelial dysfunction. However, L-T4 can control the elevated TSH by reversing the above-mentioned changes to reduce the mean C-IMT.

Six out of 13 papers in a systemic review reported that L-T4 treatment improved TC and LDL.26 An RCT with the same conclusion further supported this hypothesis.8 Among four markers of hyperlipidaemia (TC, TG, LDL, HDL), except for HDL, we observed non-significant differences between pre-treatment and post-replacement conditions, which is supported by a previous study with similar findings.27 Reports by Kannel et al28 and Lewington et al29 showed that the TC/HDL ratio is more important in the progress of coronary heart disease than either TC or HDL alone. Although HDL concentration was not changed after restoration of euthyroidism by L-T4 replacement in SCH patients in our study, L-T4 treatment altered the TC/HDL ratio. Hyperlipidaemia promotes endothelial dysfunction because it can inhibit the nitric oxide (NO) synthesis pathway in endothelial cells.30 Meanwhile, a recent paper found that SCH can cause endothelial dysfunction because of a decrease in NO availability, which is partly independent of dyslipidaemia, and L-T4 supplementation can reverse endothelial dysfunction.31 Thus, we found that SCH not only results in endothelial dysfunction but is also an independent risk factor for dyslipidaemia, which then further amplifies endothelial dysfunction. L-T4 treatment of SCH patients can reduce these effects.

A meta-analysis showed that blood pressure was an independent risk factor for C-IMT.32 Recently, another meta-analysis demonstrated that SCH is linked to higher SBP and DBP.33 We know little about the mechanism of SCH-associated hypertension; nevertheless, hypothyroidism increases vascular resistance, and enhances blood pressure, salt sensitivity and abnormal sodium metabolism, which may promote the development of hypertension.

For the short duration (≤6 months) subgroup, an insignificant difference in C-IMT was observed after treatment. Meanwhile, mean C-IMT in SCH subjects undergoing long-term treatment significantly increased compared with that in the pre-treatment condition. This phenomenon was confirmed in our clinical observation. The major reason is that the duration of treatment is too short to improve C-IMT. The rate of progression of IMT in the common carotid artery was approximately 0.01 mm/year.

For stratification by gender, we find a significant difference in female patients between pre-replacement and post-replacement. Meanwhile, for the mixed gender subgroup, mean C-IMT was significantly reduced after treatment. Although the prevalence of SCH is a little different between women and the general population, the effects of L-T4 on C-IMT are similar. This suggests that the changes in C-IMT are similar when we control thyroid function in the normal range regardless of gender.

Limitations

The number of studies included in this meta-analysis was small, and the overall population of these trials was not large. Meta-analysis has moderate heterogeneity. Difficult assessment of the potential publication bias was mainly due to the previous two factors. Additionally, we did not perform subgroup analysis according to the level of TSH (the cut-off value is 10 mU/mL to distinguish mild SCH and severe SCH) because the original studies did not perform analyses according to the level of TSH. Finally, we did not perform subgroup analysis by mean age (>65 or <65 years) because the mean age of all the participants was below 65 years.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that C-IMT in SCH patients can be reversed by L-T4 replacement. Hyperlipidaemia and hypertension may improve after L-T4 therapy. Long L-T4 replacement duration (>6 months) is more useful compared with short-term duration for improving C-IMT in SCH patients. Therefore, L-T4 supplementation can prevent or inhibit the progression of atherosclerosis, at least in SCH patients. RCTs with a larger sample size are needed to confirm these findings.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: ZT and CB made search strategies, searched papers from databases, assessed study quality, independently extracted data from the papers and wrote the paper. WH as a third reviewer was asked for advice, if there was disagreement. ZY, WX and ZY participated in the revision of the paper. SZ provided advice on the discussion section of this article.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional unpublished data are available.

References

- 1. Cooper DS. Clinical practice. Subclinical hypothyroidism. N Engl J Med 2001;345:260–5. 10.1056/NEJM200107263450406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cooper DS, Halpern R, Wood LC, et al. L-thyroxine therapy in subclinical hypothyroidism. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1984;101:18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Monzani F, Caraccio N, Del Guerra P, et al. Neuromuscular symptoms and dysfunction in subclinical hypothyroid patients: beneficial effect of L-T4 replacement therapy. Clin Endocrinol 1999;51:237–42. 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1999.00790.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. O’Leary DH, Polak JF. Intima-media thickness: a tool for atherosclerosis imaging and event prediction. Am J Cardiol 2002;90:18l–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gao N, Zhang W, Zhang YZ, et al. Carotid intima-media thickness in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism: a meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis 2013;227:18–25. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.10.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Razvi S, Ingoe L, Keeka G, et al. The beneficial effect of L-thyroxine on cardiovascular risk factors, endothelial function, and quality of life in subclinical hypothyroidism: randomized, crossover trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:1715–23. 10.1210/jc.2006-1869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Monzani F, Caraccio N, Kozàkowà M, et al. Effect of levothyroxine replacement on lipid profile and intima-media thickness in subclinical hypothyroidism: a double-blind, placebo- controlled study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:2099–106. 10.1210/jc.2003-031669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Andersen MN, Olsen AM, Madsen JC, et al. Levothyroxine substitution in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism and the risk of myocardial infarction and mortality. PLoS One 2015;10:e0129793 10.1371/journal.pone.0129793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Helfand M. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for subclinical thyroid dysfunction in nonpregnant adults: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2004;140:128–41. 10.7326/0003-4819-140-2-200401200-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Surks MI, Ortiz E, Daniels GH, et al. Subclinical thyroid disease: scientific review and guidelines for diagnosis and management. JAMA 2004;291:228–38. 10.1001/jama.291.2.228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, et al. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg 2003;73:712–6. 10.1046/j.1445-2197.2003.02748.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kulinskaya E, Dollinger MB, Bjørkestøl K. Testing for homogeneity in meta-analysis I. The one-parameter case: standardized mean difference. Biometrics 2011;67:203–12. 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2010.01442.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials revisited. Contemp Clin Trials 2015;45:139–45. 10.1016/j.cct.2015.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sterne JA, Egger M, Smith GD. Systematic reviews in health care: Investigating and dealing with publication and other biases in meta-analysis. BMJ 2001;323:101–5. 10.1136/bmj.323.7304.101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cabral MD, Teixeira P, Soares D, et al. Effects of thyroxine replacement on endothelial function and carotid artery intima-media thickness in female patients with mild subclinical hypothyroidism. Clinics 2011;66:1321–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Duman D, Demirtunc R, Sahin S, et al. The effects of simvastatin and levothyroxine on intima-media thickness of the carotid artery in female normolipemic patients with subclinical hypothyroidism: a prospective, randomized-controlled study. J Cardiovasc Med 2007;8:1007–11. 10.2459/JCM.0b013e3282f03bc1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Unsal IO, Topaloglu O, Cakir E, et al. Effect of L-thyroxin therapy on thyroid volume and carotid artery intima-media thickness in the patients with subclinical hypothyroidism. Journal of Medical Disorders 2014;2:1 10.7243/2053-3659-2-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kebapcilar L, Comlekci A, Tuncel P, et al. Effect of levothyroxine replacement therapy on paraoxonase-1 and carotid intima-media thickness in subclinical hypothyroidism. Med Sci Monit 2010;16:CR41–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Adrees M, Gibney J, El-Saeity N, et al. Effects of 18 months of L-T4 replacement in women with subclinical hypothyroidism. Clin Endocrinol 2009;71:298–303. 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03509.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yazıcı D, Özben B, Toprak A, et al. Effects of restoration of the euthyroid state on epicardial adipose tissue and carotid intima media thickness in subclinical hypothyroid patients. Endocrine 2015;48:909–15. 10.1007/s12020-014-0372-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Niknam N, Khalili N, Khosravi E, et al. Endothelial dysfunction in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism and the effects of treatment with levothyroxine. Adv Biomed Res 2016;5:38 10.4103/2277-9175.178783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim SK, Kim SH, Park KS, et al. Regression of the increased common carotid artery-intima media thickness in subclinical hypothyroidism after thyroid hormone replacement. Endocr J 2009;56:753–8. 10.1507/endocrj.K09E-049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Balzan S, Del Carratore R, Nicolini G, et al. Proangiogenic effect of TSH in human microvascular endothelial cells through its membrane receptor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97:1763–70. 10.1210/jc.2011-2146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tian L, Zhang L, Liu J, et al. Effects of TSH on the function of human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J Mol Endocrinol 2014;52:215–22. 10.1530/JME-13-0119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Danese MD, Ladenson PW, Meinert CL, et al. Clinical review 115: effect of thyroxine therapy on serum lipoproteins in patients with mild thyroid failure: a quantitative review of the literature. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000;85:2993–3001. 10.1210/jcem.85.9.6841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Asranna A, Taneja RS, Kulshreshta B. Dyslipidemia in subclinical hypothyroidism and the effect of thyroxine on lipid profile. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 2012;16(Suppl 2):S347–9. 10.4103/2230-8210.104086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kannel WB, Vasan RS, Keyes MJ, et al. Usefulness of the triglyceride-high-density lipoprotein versus the cholesterol-high-density lipoprotein ratio for predicting insulin resistance and cardiometabolic risk (from the Framingham Offspring Cohort). Am J Cardiol 2008;101:497–501. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.09.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lewington S, Whitlock G, Clarke R, et al. Blood cholesterol and vascular mortality by age, sex, and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of individual data from 61 prospective studies with 55,000 vascular deaths. Lancet 2007;370:1829–39. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61778-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ito A, Tsao PS, Adimoolam S, et al. Novel mechanism for endothelial dysfunction: dysregulation of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase. Circulation 1999;99:3092–5. 10.1161/01.CIR.99.24.3092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Taddei S, Caraccio N, Virdis A, et al. Impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilatation in subclinical hypothyroidism: beneficial effect of levothyroxine therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:3731–7. 10.1210/jc.2003-030039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang JG, Staessen JA, Li Y, et al. Carotid intima-media thickness and antihypertensive treatment: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Stroke 2006;37:1933–40. 10.1161/01.STR.0000227223.90239.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cai Y, Ren Y, Shi J. Blood pressure levels in patients with subclinical thyroid dysfunction: a meta-analysis of cross-sectional data. Hypertens Res 2011;34:1098–105. 10.1038/hr.2011.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-016053supp001.pdf (3MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-016053supp002.pdf (2.2MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-016053supp003.pdf (4MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-016053supp004.pdf (5.1MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-016053supp005.pdf (2.3MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-016053supp006.pdf (4.1MB, pdf)