Abstract

Despite intensive investigation of molecular mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of sepsis, many aspects of sepsis remain unresolved; this hampers the development of appropriate therapeutics. In the present study, we developed a biologic nanomedicine containing a cationic antimicrobial decapeptide KSLW (KKVVFWVKFK), self-associated with biocompatible and biodegradable PEGylated phospholipid micelles (PLM), and analyzed its efficacy for treating sepsis. KSLW was modified with polyethylene glycol (PEG)-aldehyde or was conjugated with distearoylphosphatidylethanolamine (DSPE) -PEG-aldehyde. We compared the antibacterial and antiseptic effects of PEG-KSLW and PLM-KSLW with those of unmodified KSLW both in vitro and in vivo. We found that the PLM-KSLW improved the survival rate of sepsis mouse models without undesired immune responses, and inhibited lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced severe vascular inflammatory responses in human umbilical vein endothelial cells compared with unmodified KSLW or PEG-KSLW. Furthermore, PLM-KSLW dramatically reduced the bacterial count and inhibited bacterial growth. We also found a new role of PLM-KSLW in tightening vascular barrier integrity by binding to the glycine/tyrosine-rich domain of occludin (OCLN). Our results showed that PLM-KSLW had a more effective antiseptic effect than KSLW or PEG-KSLW, possibly because of its high affinity toward OCLN. Moreover, PLM-KSLW could be potentially used to treat severe vascular inflammatory diseases, including sepsis and septic shock.

Keywords: sepsis, KSLW, PEGylation, DSPE, occluding.

Introduction

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), which are found from bacterial to mammalian species, form an important part of the innate immunity after inflammatory stimulation 1. AMPs inhibit the destructive effects of proinflammatory cascades induced during severe inflammatory responses by directly killing bacteria or neutralizing their pathogenic factors such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or lipoprotein 2. However, naturally occurring AMPs induce toxicity, hemolysis, nephrotoxicity, and neurotoxicity 3. Therefore, it is challenging to develop innocuous synthetic peptide-based drugs for effectively treating inflammatory diseases. Of the numerous AMPs available, we selected a cationic antimicrobial decapeptide KSLW (KKVVFWVKFK) because it contains few amino acids (12 amino acids); has a linear structure (absence of disulfide bridges), positive net charge, and low hemolytic activity; and shows antibiotic properties toward a wide range of bacteria. KSLW is commercially used to control the growth of dental plaque and in DispersinB® KSLW peptide-based wound gel for treating chronic wound infections caused by bacteria 4-5. A study showed that KSLW exerted anti-inflammatory effect on phorbol myristate acetate (PMA)- and LPS-stimulated neutrophils 6. Phospholipid, an essential component of all cellular membranes, can be aligned with bilayer membranes and self-assembled into circulating lipoproteins to form micelles 7. Polyethylene glycol (PEG)-modified distearoylphosphatidylethanolamine (DSPE-PEG), which forms sterically stabilized micelles, is widely used as a lipid-based nanocarrier for drug delivery 8. Self-assembled DSPE-PEG micelles contain a hydrophobic core made of DSPE and a hydrophilic shell made of PEG. The PEG layer increases the steric stability of the micelles, thus preventing their uptake by mononuclear phagocytic cells and substantially increasing their systemic half-life 9. PEGylated phospholipids have lower critical micelle concentration (CMC) than native phospholipids. Therefore, DSPE-PEG micelles are thermodynamically more stable than conventional micelles upon dilution 10. In addition, DSPE-PEG micelles show good biocompatibility and are relatively non-toxic 11.

Sepsis is associated with infections caused by different bacteria, viruses such as Ebola or MERS, and mites, and accounts for high mortality rate worldwide. Medical expenditure for treating sepsis is high because of the non-availability of an appropriate medicine 12. Although several studies have attempted to develop an effective treatment for sepsis by using recent advances in different therapeutics, these studies have failed to develop drugs that can increase the clinical survival rate of patients with sepsis 13-14. Recently, siRNA delivery system has been extensively used for numerous therapeutic modalities to treat severe inflammatory conditions 15-17. Early treatment of patients with severe sepsis and septic shock is the key to increase their survival rate. Initiation of anti-infective therapy and selection of an appropriate anti-infective drug with an appropriate administration time are important; however, sepsis is associated with multiple organ dysfunction induced by pathogens and endotoxins 18. Therefore, there is a growing interest to develop novel multifunctional nanomedicines that exert anti-infective and vasoprotective effects. In the present study, we developed a novel biologic nanomedicine containing KSLW, self-associated with biocompatible and biodegradable PEGylated phospholipid micelles, and analyzed its efficacy for treating sepsis.

Materials and Methods

The online supplement provides information on methods used in this study.

Results and Discussion

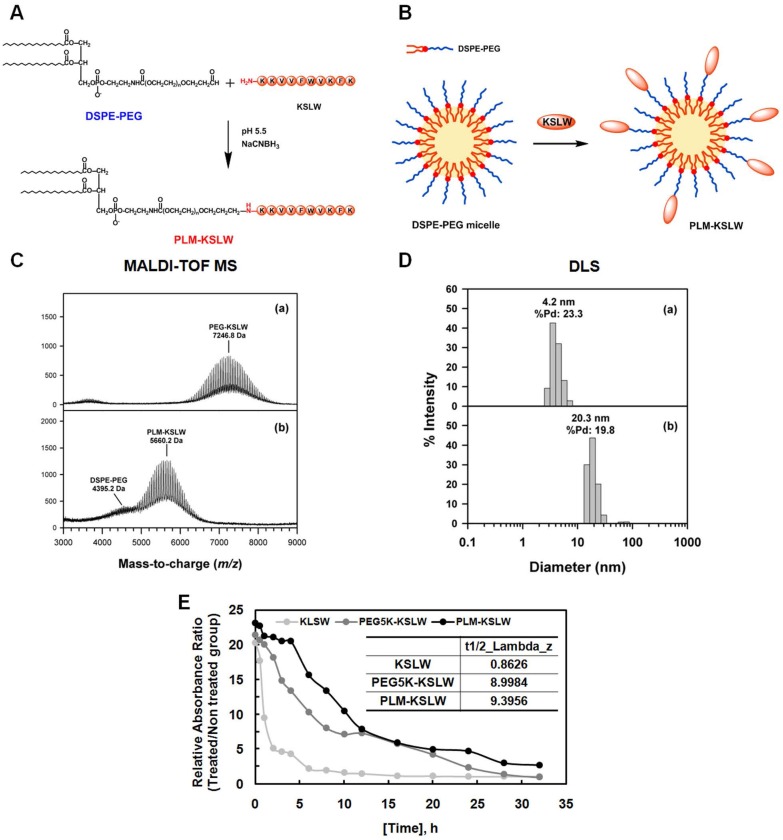

PEGylation is an effective approach for improving the therapeutic efficacy of peptide drugs by increasing their systemic circulation time, and by improving their stability in biological fluids 19-21. PEG-aldehyde (PEG-ALD) or DSPE-PEG-aldehyde (DSPE-PEG-ALD) site-specifically reacts with the N-terminal amine of KSLW under acidic conditions 22 based on the difference in the reactivity of the α-amino group at the N-terminus (pKa = 7.6-8.0), and ε-amino group in the Lys residue (pKa = 10.0-10.2) 23. In the present study, KSLW was modified using a PEG-ALD or was conjugated with DSPE-PEG-ALD. Fig. 1A shows the reaction between KSLW and DSPE-PEG-ALD, which forms a secondary amine linkage between PEG and the N-terminal amine of KSLW. Because DSPE-PEG has a low CMC of approximately 1 μM because of the requirement of strong hydrophobic driving forces for inducing self-assembly 24, KSLW reacts with the surface of these micelles (Fig. 1B). Average molecular masses of PEG-KSLW and PLM-KSLW, which were measured by performing matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS), were 7,246.8 and 5,660.2 Da, respectively (Fig. 1C), indicating that the mono-PEGylation reaction was complete in both PEG-KSLW and PLM-KSLW. Average hydrodynamic diameters of PEG-KSLW and PLM-KSLW, which were measured by performing dynamic light scattering (DLS), were 4.2 and 20.3 nm, respectively (Fig. 1D). The hydrodynamic diameter of PLM-KSLW (20.3 mm) was similar to that of DSPE-PEG-3000 reported previously 25. Percentage polydispersity (%Pd) values of PEG-KSLW and PLM-KSLW were 23.3% and 19.8%, respectively. The level of homogeneity is considered to be high when %Pd value is <15% 26. Thus, the %Pd value of PLM-KSLW (19.8%) indicates that it has relatively good homogeneity. Results of MALDI-TOF MS and DLS indicated that KSLW was successfully conjugated with DSPE-PEG, and that PLM-KSLW micelles were formed appropriately. Further, the loading capacity of KSLW in the micelles was 248 μg (± 6) per mg of micelles, indicating that the drug loading capacity was 25%. The preparation yield of PLM-KSLW was 76.8% (± 1.9). In vivo half-lives of PEG-KSLW and PLM-KSLW were >10-fold higher than that of KSLW (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1.

Synthesis and characterization of PEG-KSLW and PLM-KSLW. The reaction between DSPE-PEG and KSLW at pH 5.5 in the presence of NaCNBH3 (A) and formation of KSLW-conjugated DSPE-PEG micelles (PLM-KSLW) (B). Characterization of PEG-KSLW (C) and PLM-KSLW (D) by performing MALDI-TOF MS (left) and DLS (right). (E) Average in vivo half-lives of KSLW, PEG5K-KSLW, and PLM-KSLW are shown. The y-axis represents the relative absorbance ratio of each construct-treated group vs. untreated group.

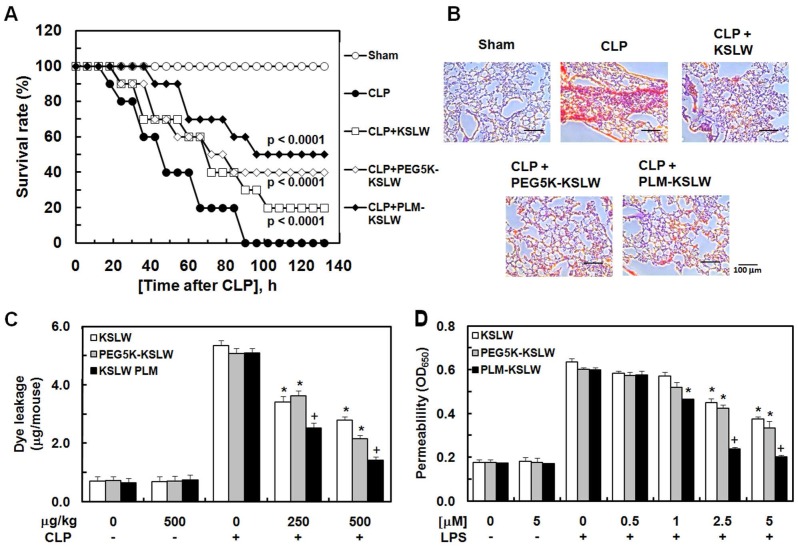

In the present study, we used a mouse model of cecal ligation and puncture (CLP)-induced sepsis because it is the most similar animal model to human sepsis 27. We hypothesized that the treatment of CLP-induced septic mice with KSLW, PEG5K-KSLW, or PLM-KSLW increased their survival because of the high clinical biocompatibility 25, 28 and antimicrobial activity of KSLW. Survival of mice was monitored for five days after CLP. The sham control mice underwent similar surgery without CLP. Treatment with KSLW, PEG5K-KSLW, and PLM-KSLW increased the survival rate of CLP-induced septic mice (Fig. 2A and Table 1). We also compared the survival rate of PLM-KSLW in CLP-induced septic mice with two other cationic AMPs, lactoferricin B or LL-37, which has anti-inflammatory or antiseptic effects. The data showed that the antiseptic effects of PLM-KSLW were better than those of lactoferricin B or LL-37 (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Moreover, treatment with each construct decreased the mortality in septic mice intravenously injected with LPS (Supplementary Fig. 1B). To confirm these beneficial effects, septic mice were infected with gram-negative or -positive bacteria and were treated with KSLW, PEG5K-KSLW, and PLM-KSLW. Treatment with KSLW, PEG5K-KSLW, and PLM-KSLW improved the survival rate of septic mice infected with gram-negative bacteria but not of septic mice infected with gram-positive bacteria (Supplementary Figs. 1C and 1D). These results confirmed the beneficial effects of each cationic construct in inhibiting the colonization and promoting the clearance of gram-negative bacteria 29. Pulmonary dysfunction and hyper-inflammation are closely associated with septic mortality 30. Histopathological examination showed that the lungs of CLP-induced septic mice showed severe injury and alveolar damage, which reduced after treatment with KSLW, PEG5K-KSLW, or PLM-KSLW (Fig. 2B). However, the histological structure of liver was normal as in the sham group (Supplementary Fig. 2). CLP also induced the formation of necrotic areas in the liver, with significantly enhanced infiltration of inflammatory cells into areas surrounding the centrilobular veins of the liver (Supplementary Fig. 2). Treatment with KSLW, PEG5K-KSLW, or PLM-KSLW, however, attenuated the severity of inflammation and necrosis induced by CLP (Supplementary Fig. 2). These results suggest that PEG5K-KSLW or PLM-KSLW promote barrier repair and endothelial cell regeneration after CLP-induced lung and liver injury. Therefore, we hypothesized that PEG5K-KSLW or PLM-KSLW exerted protective effects on vascular barrier integrity under septic condition. Because cytokines released in response to large-scale inflammation result in excessive vasodilation, increased vascular permeability, decreased systemic vascular resistance, and low blood pressure 31-32, it is important to decrease vascular permeability while treating sepsis. Therefore, we examined whether PEG5K-KSLW or PLM-KSLW inhibited LPS- or CLP-induced vascular barrier disruption in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and mice. Results of in vivo (Fig. 2C) and in vitro permeability assays (Fig. 2D) indicate that PEG5K-KSLW and PLM-KSLW prevented vascular leakage under septic conditions. The average circulating blood volume in mice is 72 mL/kg 33. Because the average weight of mice used in the present study was 26 g and their average blood volume was 2 mL, the dose of KSLW (250 or 500 µg/kg) used in the present study was equal to its peripheral blood concentration of approximately 2.5 or 5 µM. Furthermore, none of the constructs affected cell viability at concentrations up to 10 μM, as determined by performing MTT assay in HUVECs treated with each construct for 48 h (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Antiseptic effects of PEG-KSLW and PLM-KSLW. (A and B) Male C57BL/6 mice (n = 20) were treated with KSLW, PEG-KSLW, or PLM-KSLW (500 μg/kg) at 12 and 50 h after CLP. Control CLP-operated mice (○) and sham-operated mice (●) were treated with sterile saline. Survival curves of CLP-operated mice (A), and H&E staining of lung tissues (B). Images are representative of three independent experiments. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed to determine overall survival rates compared with those of CLP-operated mice. (C) Effects of treatment with 250 or 500 μg/kg of each construct on vascular permeability in CLP-induced septic mice were examined by measuring the amount of Evans blue present in peritoneal washings (expressed as μg/mouse, n = 5). (D) Effects of post-treatment with different concentrations of each construct for 6 h on barrier disruption induced by LPS (1 μg/mL, 8 h) were monitored by measuring the flux of Evans blue-bound albumin into HUVECs. All results are expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments performed on different days; *p < 0.05 vs. CLP only treatment (C) or LPS only treatment (D); +p < 0.05 vs. white or gray bar.

Table 1.

Final survival rate (%) of KSLW, PEG-KSLW, or PLM-KSLW in CLP-induced septic lethality 132 hours after CLP surgerya.

| μg/kg | Sham | CLP | CLP + KSLW | CLP + PEG5K-KSLW | CLP + PLM-KSLW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 20 |

| 250 | 100 | 0 | 5 | 20 | 40 |

| 500 | 100 | 0 | 20 | 40 | 50 |

aEach value represents the means±SD (n=20).

Systemic inflammatory responses in sepsis induce the failure of major organs such as the liver and kidney 34. CLP significantly increased the plasma levels of alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST), which are hepatic injury markers (Supplementary Fig. 3A), and creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN), which are renal injury markers (Supplementary Figs. 3B and 3C). PEG5K-KSLW or PLM-KSLW treatment decreased CLP-induced increase in the levels of hepatic and renal injury markers. PEG5K-KSLW or PLM-KSLW treatment also decreased the levels of LDH, another important tissue injury marker, in CLP-operated mice (Supplementary Fig. 3D). Moreover, PEG5K-KSLW or PLM-KSLW treatment significantly decreased CLP-induced increase in the levels of inflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and IL-10 (Supplementary Fig. 3E); tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α (Supplementary Fig. 3F); and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1; Supplementary Fig. 3G). These results indicate that PLM-KSLW was a more effective antiseptic than KSLW and PEG5K-KSLW. This may be because of the high affinity of PLM-KSLW toward occludin (OCLN), the main tight junction protein expressed on vascular endothelial cells, compared with that of KSLW and PEG5K-KSLW (Supplementary Fig. 4A-4C). A plausible explanation is that because PLM forms micelles at high concentration, circulates stably in the body, and biodegrades into a monomer 24, an unwearied monomeric form of PLM-KSLW may protect vascular barrier function and exert antiseptic effects. In addition, CD31 (endothelial cell marker) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) showed the compatibility of KSLW, PEG5K-KSLW, or PLM-KSLW in normal human endothelial cells (Supplementary Fig. 4D). Next, we determined whether KSLW or PLM-KSLW caused undesired immune responses after i.v. injection. To do this, we examined the expression levels of various cytokines such as inflammatory or T cell cytokines, IgG2A, and IgG2B in the mouse blood. Data showed that Th1 cytokines (interferon (IFN)-γ, IL-2), Th2 cytokines (IL-4, -5, -13), and inflammatory related cytokines (IL-1β, -6, -13, TNF-α) did not show significant changes within five days after injection (Table 2). Further, the expression levels of IgG2A and IgG2B were not changed significantly by KSLW or PLM-KSLW (Table 2). These results suggest that PLM-KSLW ameliorates polymicrobial septic death without undesired immune responses, and can be used as a potential therapeutic drug candidate for treating sepsis and septic shock.

Table 2.

Effects of KSLW or PLM-KSLW on the expressions of cytokines, IgG2A, and IgG2B in vivo after 5 days i.v. injectiona.

| PBS | KSLW(500 μg/kg) | PLM-KSLW(500 μg/kg) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IFN-γ (pg/mL) | 11.35 ± 1.32 | 12.72 ± 1.53 | 12.58 ± 1.56 |

| IL-1β (ng/mL) | 0.51 ± 0.04 | 0.47 ± 0.03 | 0.42 ± 0.05 |

| IL-2 (pg/mL) | 10.21 ± 0.85 | 10.75 ± 0.95 | 11.05 ± 1.12 |

| IL-4 (pg/mL) | 12.35 ± 1.41 | 13.14 ± 1.75 | 12.92 ± 1.22 |

| IL-5 (pg/mL) | 43.82 ± 2.92 | 40.83 ± 3.14 | 42.11 ± 3.13 |

| IL-6 (ng/mL) | 0.54 ± 0.054 | 0.59 ± 0.04 | 0.53 ± 0.06 |

| IL-13 (pg/mL) | 60.57 ± 5.35 | 62.05 ± 4.31 | 61.35 ± 5.35 |

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 195.53 ± 15.31 | 205.31 ± 17.39 | 214.07 ± 12.39 |

| IgG2A (OD490) | 0.249 ± 0.023 | 0.235 ± 0.017 | 0.252 ± 0.031 |

| IgG2B (OD490) | 0.275 ± 0.015 | 0.265 ± 0.024 | 0.281 ± 0.031 |

aEach value represents the means±SD (n=5).

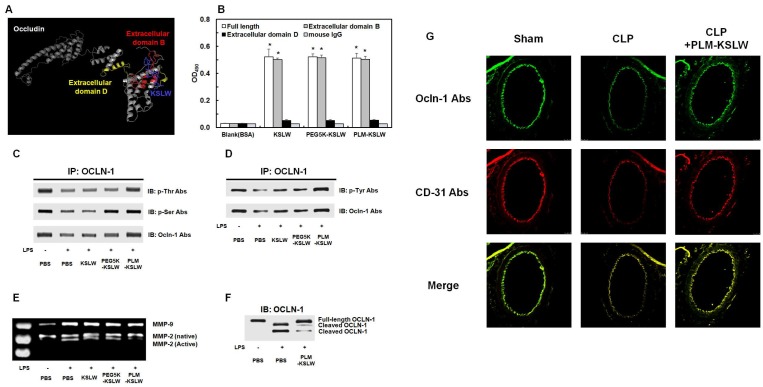

We determined the binding proteins and domains of KSLW in vascular endothelial cells by using I-TASSER method 35-37 and ZDOCK-server 38 that predicted its protein structure and protein-peptide docking model, respectively. KSLW binds to the extracellular loop B glycine/tyrosine (GY)-rich domain of OCLN, which is the cleavage site for matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) (Fig. 3A, docking image) 39-40. Results of previous studies indicate that vascular barrier disruption occurs because of the destruction of tight junction architecture in vascular endothelial cells 41, and that the extracellular loops of OCLN play a critical role in tight junctions to maintain vascular barrier integrity 42-43. Thus, our results indicate that KSLW is a novel binding partner of OCLN and exerts protective effects against vascular barrier disruption. To determine the ability of KSLW, PEG5K-KSLW, or PLM-KSLW to directly bind OCLN, we determined the binding affinities of these constructs toward the extracellular loops B and D of OCLN and toward full-length OCLN (Supplementary Fig. 5) by performing solid-phase ELISA. Our results showed that each construct complexed with full-length OCLN and with extracellular loop B of OCLN (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Fig. 4), and that the binding ability of PLM-KSLW was better than that of KSLW or PEG5K-KSLW (Supplementary Figs. 4A and 4B). However, none of the constructs interacted with the extracellular loop D of OCLN (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Fig. 4C), as predicted using the ZDOCK server. These results suggest that the modification of KSLW does not induce a steric hindrance in its binding to the extracellular loop B of OCLN. PLM-KSLW inhibited inflammation-induced reduction in OCLN phosphorylation (Figs. 3C and 3D), which was consistent with the findings of a previous study that septic condition decreased the phosphorylation of Ser, Thr, and Tyr residues in OCLN expressed on endothelial cells 44-45, and that dephosphorylation of OCLN was associated with the disassembly of tight junctions and increase in vascular permeability 46-47. Secreted MMP-induced cleavage of OCLN under inflammatory condition impairs the barrier function of endothelial cells and redistributes tight junctional molecules in cell contact site 48. Therefore, PLM-KSLW may prevent secreted MMP-induced cleavage of OCLN under inflammatory condition (Figs. 3E and 3F). These results (Figs. 3C-3F) were confirmed by performing confocal imaging, which indicated that PLM-KSLW decreased the increase in OCLN cleavage in the mouse vena cava (Fig. 3G). These results suggest that PLM-KSLW complexes with OCLN and inhibits its dephosphorylation and cleavage by inducing steric hindrance, and by forming a protective layer on blood vessels, thus inhibiting sepsis-induced cleavage of endothelial tight junctions and disruption of the vascular barrier.

Figure 3.

Binding affinities of KSLW, PEG-KSLW, and PLM-KSLW toward OCLN and their effects on the cleavage of OCLN. (A) Binding of KSLW (blue) to the extracellular domain B (red), extracellular domain D (yellow), or other sites (gray) of OCLN was predicted using the ZDOCK server. (B) The ability of KSLW, PEG-KSLW, and PLM-KSLW to bind to full-length OCLN (white), extracellular domain B of OCLN (gray), or extracellular domain D of OCLN (black) were measured by performing ELISA; *p < 0.05 vs. BSA (B). All results are expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments performed on different days. (C and D) PLM-KSLW suppressed LPS-induced phosphorylation of Thr, Ser, and Tyr residues of OCLN, as determined by performing immunoprecipitation (IP) and immunoblotting (IB). (E) Enzymatic activity of MMP-2 or MMP-9 in cell culture supernatants of LPS-treated HUVECs was determined by performing SDS-PAGE gelatin zymography. (F) Protective effect of PLM-KSLW against the cleavage of OCLN in HUVECs treated with LPS (1 μg/ml, 12 h) was determined by performing western blotting. (G) Protective effect of PLM-KSLW on the cleavage of OCLN after CLP was examined by performing immunohistochemistry. OCLN (green) and CD31 (red) were stained with the respective fluorescent antibodies and were imaged by performing confocal microscopy. Images are representative of three independent experiments.

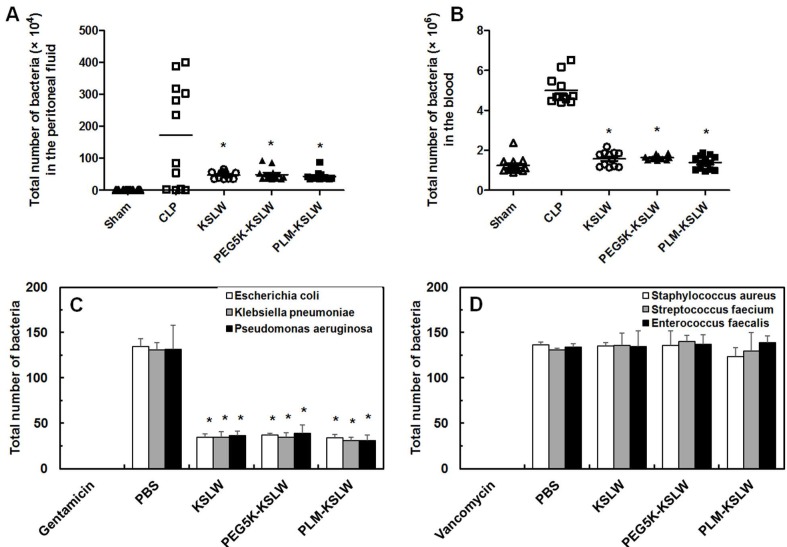

Previous studies have shown that CLP lethality is associated with bacterial colony count in the peritoneal fluid and blood 30, 49. In the present study, we determined the effect of KSLW, PEG5K-KSLW, or PLM-KSLW on bacterial clearance in both the peritoneal fluid and blood. Treatment with KSLW, PEG5K-KSLW, or PLM-KSLW dramatically decreased bacterial colony count by 70% in the peritoneal fluid and by 90% in the blood at 24 h after CLP (Figs. 4A and 4B). Because results of clinical studies indicate that the use of antimicrobial agents is a definitive therapeutic strategy for treating patients with sepsis 50-53, we determined the direct bactericidal effects of KSLW, PEG5K-KSLW, or PLM-KSLW in vitro. Antimicrobial activity of KSLW, PEG5K-KSLW, or PLM-KSLW was examined using gram-negative (Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa) and gram-positive (Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus faecium, and Enterococcus faecalis) bacteria. Gentamicin and vancomycin were used as positive controls for determining antimicrobial activities against gram-negative and gram-positive, respectively. We found that KSLW, PEG5K-KSLW, and PLM-KSLW showed antibacterial activity against gram-negative bacteria but not against gram-positive bacteria (Figs. 4C and 4D). KSLW reduced bacterial count and inhibited bacterial growth. These findings indicate that KSLW performs a dual function, in that it inhibits bacterial growth in the peritoneal fluid and blood and prevents OCLN cleavage in vascular endothelial cells, indicating its potent usefulness for treating sepsis.

Figure 4.

In vivo and in vitro bactericidal activities of KSLW, PEG-KSLW, and PLM-KSLW. (A and B) KSLW, PEG-KSLW, and PLM-KSLW (500 μg/kg) were intravenously injected into CLP-induced septic mice 12 h after CLP. Bacterial loads in the peritoneal fluid (A) and blood (B) of CLP-operated mice (n = 10 each) treated with KSLW, PEG-KSLW, or PLM-KSLW were analyzed by counting bacterial colonies. Data were statistically analyzed using Mann-Whitney U test. (C and D). Bactericidal effect of KSLW, PEG-KSLW, or PLM-KSLW on gram-negative or -positive bacteria. Gram-negative and -positive bacteria seeded in Luria-Bertani (LB) plates were treated with the indicated concentrations of KSLW, PEG-KSLW, or PLM-KSLW, and surviving colonies were counted. LB plates containing antibiotics gentamicin or vancomycin were used as positive controls. All results are expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments performed on different days; *p < 0.05 vs. CLP only treatment (A and B) or PBS treatment (C).

Vascular inflammation increases the expression of cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) such as vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), and E-selectin on the surface of endothelial cells and leukocytes, thus promoting the adhesion and migration of leukocytes across the endothelium 54. Under severe septic condition, many neutrophils adhere to the surface of the endothelium and transmigrate to the extravascular space, resulting in severe microvascular injury and dysfunction 55. We hypothesized that treatment with KSLW, PEG5K-KSLW, and PLM-KSLW alleviated LPS-induced vascular inflammatory responses. We found that treatment with KSLW, PEG5K-KSLW, and PLM-KSLW inhibited LPS-mediated upregulation of CAM expression (Supplementary Figs. 6A-6C), adhesion of leukocytes (Supplementary Fig. 6D), transendothelial migration (Supplementary Fig. 6E), and CLP-induced migration of leukocytes (Supplementary Fig. 6F). These results indicate the potential of KSLW, PEG5K-KSLW, and PLM-KSLW for treating severe vascular inflammatory diseases. PLM-KSLW showed the highest anti-inflammatory activity, followed by KSLW and PEG5K-KSLW.

Thus, we developed a novel safe antimicrobial peptide, KSLW, in the form of a PEGylated phospholipid micelle, and determined its efficacy in decreasing sepsis-associated mortality rate because of its increased bioavailability. Interestingly, we found a novel role of PLM-KSLW in tightening vascular barrier integrity by binding to the GY-rich domain of OCLN, a tight junction protein. Furthermore, PLM-KSLW improved the survival rate of mouse models with LPS-, bacteria-, and CLP-induced sepsis and inhibited LPS-induced severe vascular inflammatory responses in HUVECs. We believe that PLM-KSLW can be used for treating sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock because of its dual function of exerting antibacterial and cytoprotective effects against bacteria and proinflammatory mediators, respectively.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (2014R1A2A1A11049526), by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2016R1A6A3A11934589), and by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HI14C2202 and HI15C0001).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures.

References

- 1.Jenssen H, Hamill P, Hancock RE. Peptide antimicrobial agents. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:491–511. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00056-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pfalzgraff A, Heinbockel L, Su Q, Gutsmann T, Brandenburg K, Weindl G. Synthetic antimicrobial and LPS-neutralising peptides suppress inflammatory and immune responses in skin cells and promote keratinocyte migration. Sci Rep-UK. 2016;6:31577. doi: 10.1038/srep31577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gordon YJ, Romanowski EG, McDermott AM. A review of antimicrobial peptides and their therapeutic potential as anti-infective drugs. Curr Eye Res. 2005;30:505–15. doi: 10.1080/02713680590968637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leung KP, Abercrombie JJ, Campbell TM, Gilmore KD, Bell CA, Faraj JA. et al. Antimicrobial peptides for plaque control. Adv Dent Res. 2009;21:57–62. doi: 10.1177/0895937409335627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gawande PV, Leung KP, Madhyastha S. Antibiofilm and antimicrobial efficacy of DispersinB(R)-KSL-W peptide-based wound gel against chronic wound infection associated bacteria. Curr Microbiol. 2014;68:635–41. doi: 10.1007/s00284-014-0519-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams RL, Sroussi HY, Leung K, Marucha PT. Antimicrobial decapeptide KSL-W enhances neutrophil chemotaxis and function. Peptides. 2012;33:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2011.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Helm F, Fricker G. Liposomal conjugates for drug delivery to the central nervous system. Pharmaceutics. 2015;7:27–42. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics7020027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang RR, Xiao RZ, Zeng ZW, Xu LL, Wang JJ. Application of poly(ethylene glycol)-distearoylphosphatidylethanolamine (PEG-DSPE) block copolymers and their derivatives as nanomaterials in drug delivery. Int J Nanomed. 2012;7:4185–98. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S34489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamada A, Taniguchi Y, Kawano K, Honda T, Hattori Y, Maitani Y. Design of folate-linked liposomal doxorubicin to its antitumor effect in mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:8161–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsiraki MI, Karam L, Abiad MG, Yehia HM, Savvaidis IN. Use of natural antimicrobials to improve the quality characteristics of fresh "Phyllo" - A dough-based wheat product - Shelf life assessment. Food Microbiol. 2017;62:153–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torchilin VP. Micellar nanocarriers: pharmaceutical perspectives. Pharm Res. 2007;24:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jafarzadeh SR, Thomas BS, Gill J, Fraser VJ, Marschall J, Warren DK. Sepsis surveillance from administrative data in the absence of a perfect verification. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26:717–22. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2016.08.002. e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coccolini F, Sartelli M, Catena F, Ceresoli M, Montori G, Ansaloni L. Early goal-directed treatment versus standard care in management of early septic shock: Meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Trauma Acute Care. 2016;81:971–8. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marshall JC. Special issue: Sepsis Why have clinical trials in sepsis failed? Trends Mol Med. 2014;20:195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ye C, Choi JG, Abraham S, Wu H, Diaz D, Terreros D. et al. Human macrophage and dendritic cell-specific silencing of high-mobility group protein B1 ameliorates sepsis in a humanized mouse model. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:21052–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216195109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He H, Zheng N, Song Z, Kim KH, Yao C, Zhang R. et al. Suppression of Hepatic Inflammation via Systemic siRNA Delivery by Membrane-Disruptive and Endosomolytic Helical Polypeptide Hybrid Nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2016;10:1859–70. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b05470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee S, Yang SC, Kao CY, Pierce RH, Murthy N. Solid polymeric microparticles enhance the delivery of siRNA to macrophages in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:e145. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valles J, Rello J, Ochagavia A, Garnacho J, Alcala MA. Community-acquired bloodstream infection in critically ill adult patients: impact of shock and inappropriate antibiotic therapy on survival. Chest. 2003;123:1615–24. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.5.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee W, Park EJ, Kwak S, Lee KC, Na DH, Bae JS. Trimeric PEG-Conjugated Exendin-4 for the Treatment of Sepsis. Biomacromolecules. 2016;17:1160–9. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.5b01756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim MS, Park EJ, Na DH. Synthesis and characterization of monodisperse poly(ethylene glycol)-conjugated collagen pentapeptides with collagen biosynthesis-stimulating activity. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2015;25:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swierczewska M, Lee KC, Lee S. What is the future of PEGylated therapies? Expert Opin Emerg Dr. 2015;20:531–6. doi: 10.1517/14728214.2015.1113254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park EJ, Na DH. Characterization of the Reversed-Phase Chromatographic Behavior of PEGylated Peptides Based on the Poly(ethylene glycol) Dispersity. Anal Chem. 2016;88:10848–53. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b03577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kinstler O, Molineux G, Treuheit M, Ladd D, Gegg C. Mono-N-terminal poly(ethylene glycol)-protein conjugates. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54:477–85. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kastantin M, Ananthanarayanan B, Karmali P, Ruoslahti E, Tirrell M. Effect of the lipid chain melting transition on the stability of DSPE-PEG(2000) micelles. Langmuir. 2009;25:7279–86. doi: 10.1021/la900310k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ashok B, Arleth L, Hjelm RP, Rubinstein I, Onyuksel H. In vitro characterization of PEGylated phospholipid micelles for improved drug solubilization: effects of PEG chain length and PC incorporation. J Pharm Sci-US. 2004;93:2476–87. doi: 10.1002/jps.20150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perevyazko IY, Delaney JT, Vollrath A, Pavlov GM, Schubert S, Schubert US. Examination and optimization of the self-assembly of biocompatible, polymeric nanoparticles by high-throughput nanoprecipitation. Soft Matter. 2011;7:5030–5. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buras JA, Holzmann B, Sitkovsky M. Animal models of sepsis: setting the stage. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:854–65. doi: 10.1038/nrd1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lukyanov AN, Gao Z, Mazzola L, Torchilin VP. Polyethylene glycol-diacyllipid micelles demonstrate increased acculumation in subcutaneous tumors in mice. Pharm Res. 2002;19:1424–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1020488012264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malanovic N, Lohner K. Antimicrobial Peptides Targeting Gram-Positive Bacteria. Pharmaceuticals; 2016. p. 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen J. The immunopathogenesis of sepsis. Nature. 2002;420:885–91. doi: 10.1038/nature01326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wynn JL, Wong HR. Pathophysiology and treatment of septic shock in neonates. Clin Perinatol. 2010;37:439–79. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schumer W. Pathophysiology and treatment of septic shock. Am J Emerg Med. 1984;2:74–7. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(84)90112-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Diehl KH, Hull R, Morton D, Pfister R, Rabemampianina Y, Smith D. et al. A good practice guide to the administration of substances and removal of blood, including routes and volumes. J Appl Toxicol. 2001;21:15–23. doi: 10.1002/jat.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Astiz ME, Rackow EC. Septic shock. Lancet. 1998;351:1501–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)01134-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roy A, Kucukural A, Zhang Y. I-TASSER: a unified platform for automated protein structure and function prediction. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:725–38. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang J, Yan R, Roy A, Xu D, Poisson J, Zhang Y. The I-TASSER Suite: protein structure and function prediction. Nat Methods. 2015;12:7–8. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y. I-TASSER server for protein 3D structure prediction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pierce BG, Wiehe K, Hwang H, Kim BH, Vreven T, Weng Z. ZDOCK server: interactive docking prediction of protein-protein complexes and symmetric multimers. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1771–3. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nava P, Kamekura R, Nusrat A. Cleavage of transmembrane junction proteins and their role in regulating epithelial homeostasis. Tissue Barriers. 2013;1:e24783. doi: 10.4161/tisb.24783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Osanai M, Murata M, Nishikiori N, Chiba H, Kojima T, Sawada N. Epigenetic silencing of occludin promotes tumorigenic and metastatic properties of cancer cells via modulations of unique sets of apoptosis-associated genes. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9125–33. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chattopadhyay R, Dyukova E, Singh NK, Ohba M, Mobley JA, Rao GN. Vascular endothelial tight junctions and barrier function are disrupted by 15(S)-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid partly via protein kinase C epsilon-mediated zona occludens-1 phosphorylation at threonine 770/772. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:3148–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.528190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Denker BM, Nigam SK. Molecular structure and assembly of the tight junction. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:F1–9. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.274.1.F1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morita K, Sasaki H, Furuse M, Tsukita S. Endothelial claudin: claudin-5/TMVCF constitutes tight junction strands in endothelial cells. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:185–94. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.1.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou G, Kamenos G, Pendem S, Wilson JX, Wu F. Ascorbate protects against vascular leakage in cecal ligation and puncture-induced septic peritonitis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2012;302:R409–16. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00153.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sheth P, Delos Santos N, Seth A, LaRusso NF, Rao RK. Lipopolysaccharide disrupts tight junctions in cholangiocyte monolayers by a c-Src-, TLR4-, and LBP-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G308–18. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00582.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Han M, Pendem S, Teh SL, Sukumaran DK, Wu F, Wilson JX. Ascorbate protects endothelial barrier function during septic insult: Role of protein phosphatase type 2A. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:128–35. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nunbhakdi-Craig V, Machleidt T, Ogris E, Bellotto D, White CL 3rd, Sontag E. Protein phosphatase 2A associates with and regulates atypical PKC and the epithelial tight junction complex. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:967–78. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200206114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qin LH, Huang W, Mo XA, Chen YL, Wu XH. LPS Induces Occludin Dysregulation in Cerebral Microvascular Endothelial Cells via MAPK Signaling and Augmenting MMP-2 Levels. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2015;2015:120641. doi: 10.1155/2015/120641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Riedemann NC, Guo RF, Ward PA. Novel strategies for the treatment of sepsis. Nat Med. 2003;9:517–24. doi: 10.1038/nm0503-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ibrahim EH, Sherman G, Ward S, Fraser VJ, Kollef MH. The influence of inadequate antimicrobial treatment of bloodstream infections on patient outcomes in the ICU setting. Chest. 2000;118:146–55. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.1.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kang CI, Kim SH, Kim HB, Park SW, Choe YJ, Oh MD. et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia: risk factors for mortality and influence of delayed receipt of effective antimicrobial therapy on clinical outcome. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:745–51. doi: 10.1086/377200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kang CI, Kim SH, Park WB, Lee KD, Kim HB, Kim EC. et al. Bloodstream infections caused by antibiotic-resistant gram-negative bacilli: risk factors for mortality and impact of inappropriate initial antimicrobial therapy on outcome. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:760–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.2.760-766.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Micek ST, Lloyd AE, Ritchie DJ, Reichley RM, Fraser VJ, Kollef MH. Pseudomonas aeruginosa bloodstream infection: importance of appropriate initial antimicrobial treatment. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:1306–11. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.4.1306-1311.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Frenette PS, Wagner DD. Adhesion molecules-Part 1. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1526–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199606063342308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brown KA, Brain SD, Pearson JD, Edgeworth JD, Lewis SM, Treacher DF. Neutrophils in development of multiple organ failure in sepsis. Lancet. 2006;368:157–69. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures.