Abstract

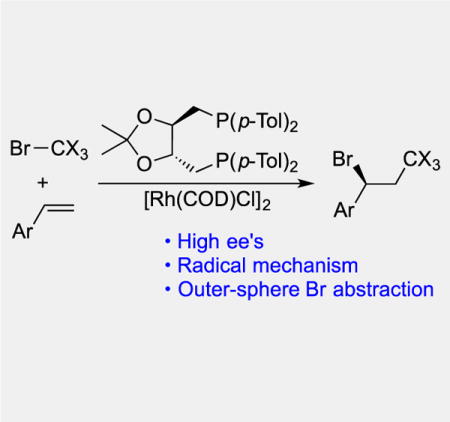

We describe an enantioselective addition of Br-CX3 (X = Cl or Br) to terminal olefins that introduces a trihalomethyl group and generates optically active secondary bromides. Computational and experimental evidence supports an asymmetric atom transfer radical addition (ATRA) mechanism in which the stereodetermining step involves outer-sphere bromine abstraction from a (bisphosphine)Rh(II)BrCl complex by a benzylic radical intermediate. Beyond the synthetic utility, this mechanism appears unprecedented in asymmetric catalysis.

Keywords: asymmetric catalysis, radical addition, enantioselectivity

TOC image

The first highly enantioselective Kharasch addition reaction involves CX3 radical addition to olefins followed by outer-sphere bromine abstraction from a Rh(II)Br complex. The reaction provides benzylic bromides in enantioenriched form and high yields.

Radical additions to olefins provide effective methods to increase molecular complexity. For example, in 1945 Kharasch described the addition of CX4 across terminal olefins to form a new C-C bond, introduce a new CX3 group and generate a new C-X bond (Figure 1a).[1] This addition generally occurs with high Markovnikov selectivity and good functional group tolerance.[2] More broadly, free radicals are prized intermediates in organic synthesis because they possess exceptional reactivity, although controlling that reactivity remains difficult.[3] In this context, the development of an enantio-selective Kharasch addition reaction appeared valuable for both practical and fundamental reasons. It would provide optically active alkyl halides,[4] and the trihalomethyl group finds utility as a metabolically stable replacement for –CH3 groups. Finally, an asymmetric platform for the Kharasch addition reaction could potentially be expanded to other C-X (X = halide) and X-Y (Y = SR, NR2) reagents.

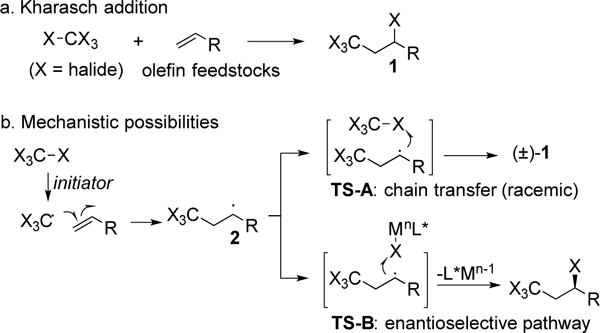

Figure 1.

Addition of CX4 reagents to olefins.

Kharasch noted, “Strange as the reactions cited may appear, the explanation of their mechanisms is not too difficult.”[1] These atom-transfer radical additions proceed through addition of the CX3 radical to an olefin, followed by abstraction of bromine radical to form the secondary C-Br bond (Figure 1B). Transition metals, heat or peroxides can initiate the reaction by generating the CX3 radical. Importantly, in this scenario the initiator does not participate in the stereodetermining step, which involves abstraction of X radical from CX4 to complete the propagation cycle (see TS-A).[3], [5] Accordingly, asymmetric induction is impossible with this mode of initiation.[6]

We hypothesized that radical abstraction of a halide from CX4 by a metal catalyst (Mn) would generate the CX3 radical and an M(n+1)-X species. Radical addition to the terminal olefin would generate the secondary radical as in the radical propagation mechanism. In the key step, abstraction of X from the M-X species would form the new C-X bond. Thus, the metal catalyst would be present in the stereodetermining step, offering the possibility to induce asymmetry with chiral ligands on the metal (see TS-B)

While the transition state envisioned in TS-B could lead to an enantioselective reaction, it appears largely unprecedented. More generally, asymmetric radical reactions of any type are rare, although notable successes have been achieved recently.[7] Most existing asymmetric radical reactions fall into one of three mechanistic classes. Most commonly, a radical adds to an olefin that is associated with a chiral metal complex (3, Figure 2A). Examples include the addition of nucleophilic radicals,[8] aminomethyl radicals,[9] and photolytically generated alkyl radicals[10] to α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds. Additionally, enolates coordinated to a chiral-at-metal Ir complex can combine with electrophilic trichloromethyl radicals[11] and electron-poor benzylic radicals.[12],[13]

Figure 2.

Mechanisms of asymmetric radical reactions. A. Radical addition to metal-coordinated substrate. B. Oxidation of chiral enamine intermediates followed by radical trapping. C. Metal capture of radical intermediates follwed by reductive elimination. D. Outer-sphere ligand abstraction by pro-chiral radical.

A second mechanistic platform for asymmetric radical reactions features organocatalysts (Figure 2B). Chiral enamines 4 can undergo single electron transfer to generate a chiral radical species that then combines with a radical electrophile, as described by the Sibi[14] and MacMillan[15] laboratories.[16,17]

A third mechanism for enantioselective catalysis involving radical intermediates relies on inner-sphere bond formation from organometallic intermediates (Figure 2C). The Fu group defined a Ni-catalyzed cross-coupling of racemic alkyl bromides with a variety of electrophiles.[18] In these transformations a secondary radical likely combines with an alkyl metal species to provide a dialkyl metal species 6. Reductive elimination generates the optically active cross-coupled product (7).[19] More recently Liu and Stahl reported a related Cu-catalyzed benzylic cyanation.[20,21] Cu-catalyzed α-amination of amides[22] and difunctionalization of olefins[23] likely operate through similar inner-sphere mechanisms, although complete mechanistic details are not available.

In contrast to the three mechanistic classes described above, a fourth potential mechanism remains essentially unexplored. Specifically, we wondered if it might be possible to effect an enantioselective outer-sphere bromine abstraction from an optically active metal bromide (Figure 2D). We are aware of only three examples of asymmetric Kharash addition reactions: The addition of CCl3Br to acrylates and styrene in up to 22% ee[24] and 30% ee, respectively.[25] Alternatively, ArSO2Cl added to styrene in up to 40% ee.[26] More generally, we are aware of no asymmetric reactions that have been shown to involve outer-sphere abstraction of one of the ligands (halide in our case) by a radical, although the Jacobsen epoxidation likely involves radical addition to a metal oxo species.[27] Accordingly, the development of an enantioselective Kharasch addition could solve a long-standing challenge in asymmetric synthesis and provide a new mechanistic platform for the development of a variety of enantioselective reactions.

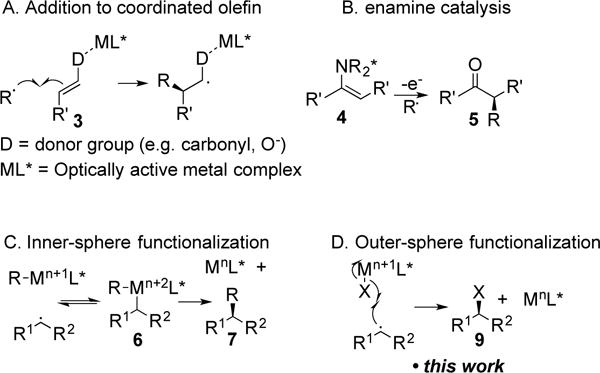

We initiated our investigations by evaluating the addition of BrCCl3 to styrene (Figure 3). We evaluated a variety of redox-active transition metals including Fe, Mn, Ni, Rh, Ru, Ir and Cu in our initial survey, and discovered that Rh(I) complexes promoted the reaction at room temperature and below. Therefore, we combined [Rh(COD)Cl]2 with a variety of monodentate and bidentate ligands and evaluated the ability of the resulting complexes to catalyze the Kharasch reaction at −78 °C. Monodentate phosphines and phosphoramidites did not yield active catalysts. Likewise, the complexes derived from BINAP, DuPhos and Trost’s ligand[28] proved largely inactive. By contrast, chelating phosphines of the form Ph2P-(CH2)n-PPh2 proved more promising. Interestingly, we noticed a profound impact on bite angle such that bis(diphenylphosphino)butane generated the racemic product in quantitative yield whereas bis-phosphines with longer or shorter linkers were markedly less effective. DIOP features a similar 4-carbon bridge between phosphines, and it is also a diaryl, alkyl phosphine. We were therefore gratified to discover that the complex derived from DIOP (10a) and a Rh(I) source provided the secondary bromide in 89:11 er. p-Tol-DIOP (10d) emerged as the optimal ligand. In detail, small electron-donating groups (Me, OMe) at the 4-position of the phenyl ring improved er’s while larger (Me > Et > iPr > tBu) alkyl groups or halogens decreased enantioselectivity. Substitution on the 2 or 3 position had deleterious effects on reactivity and selectivity (10k, 10l). The ketal substitution on DIOP had little impact on reactivity or selectivity (10a, 10m – 10p). However, the reaction appears very sensitive to steric effects on the ligand because methyl substitution adjacent to the phosphine totally inhibited the reaction (10q, 10r). Finally, we observed modest increases in enantioselectivity (depending on substrate) when the reaction was carried out in a 1:1 mixture of hexane and toluene. Other modifications to the reaction conditions did not improve selectivity including lower or higher temperatures, alternative Rh(I) sources, or different solvent mixtures.29

Figure 3.

Discovery of an enantioselective Kharasch reaction

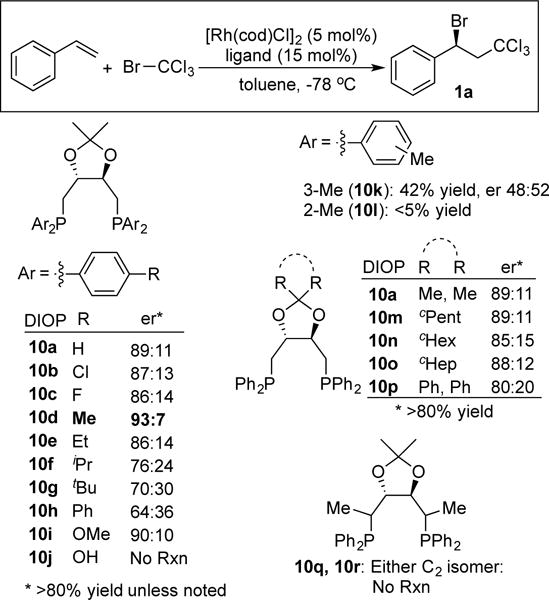

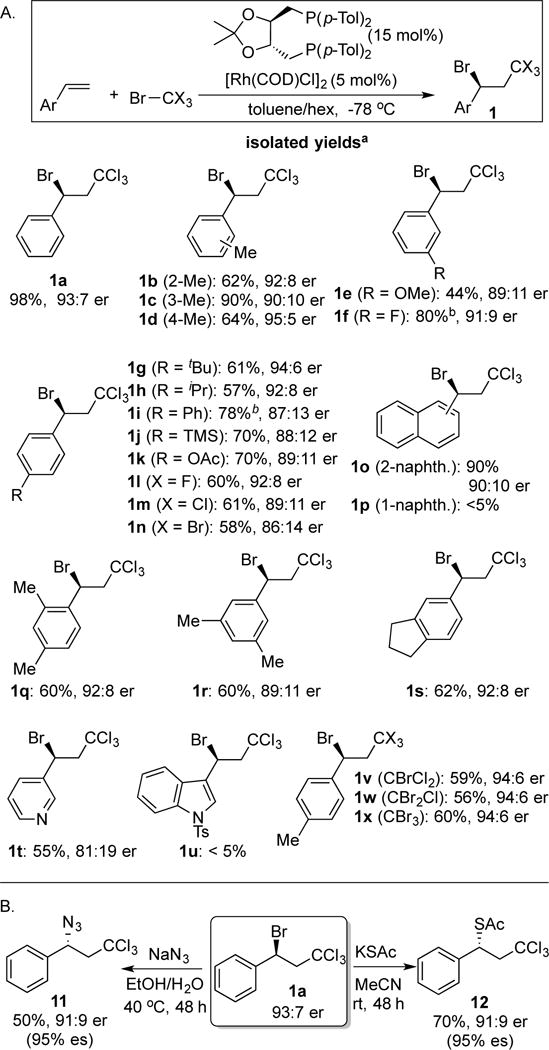

The addition of BrCCl3 to vinyl arenes tolerates functional groups such as alkyl, halides, ester, methoxy, and TMS groups (Fig 4, 1b–1n). The substituents on the aromatic ring could be in the ortho, meta, or para position (1b–1d). The addition is relatively insensitive to sterics at the para-position, and electron-donating and modestly electron withdrawing groups are suitable. In contrast, strongly electron-withdrawing groups (CN, CF3) lead to poor enantioselectivity. Multiply- substituted styrenes are also suitable substrates for this reaction (1q–1s). 3-Vinyl pyridine afforded the adduct in moderate yield and ee (1t), while vinyl indole generated an unstable product (1u). Similarly, 2-vinyl naphthalene was an excellent substrate (1o), but the product derived from 1-vinyl naphthalene (1p) could not be isolated.

Figure 4.

A. Substrate scope for the addition of tetrahalomethanes to vinyl arenes. aReactions carried out with 0.25 mmol olefin, 0.5 mmol CX4, in 2.5 mL toluene/hexanes (1:1 v/v). Er’s determined by HPLC. btoluene solvent. B. Derivitization of secondary bromide 1a.

Other polyhalomethanes could react to give similar Kharasch Thus, a –CCl3, –CBrCl2, –CBr2Cl and a –CBr3 group could all be introduced with similar selectivity and yield (1v–1x). With bromo-chloro-methanes, exclusive formation of the benzylic bromide was observed, and we have not isolated any benzylic chloride products when the reaction is performed at −78 °C.

Benzylic bromides are synthetically valuable as substrates for stereospecific SN2 substitutions. We have performed preliminary experiments to evaluate the range of suitable nucleophiles for substitution reactions. Specifically, the C-Br bond can be transformed into a C-N (11) and C-S (12) bond with high stereochemical fidelity and moderate yield. Currently, attempted substitution with carbon nucleophiles (cyanide, enolates) leads to elimination.

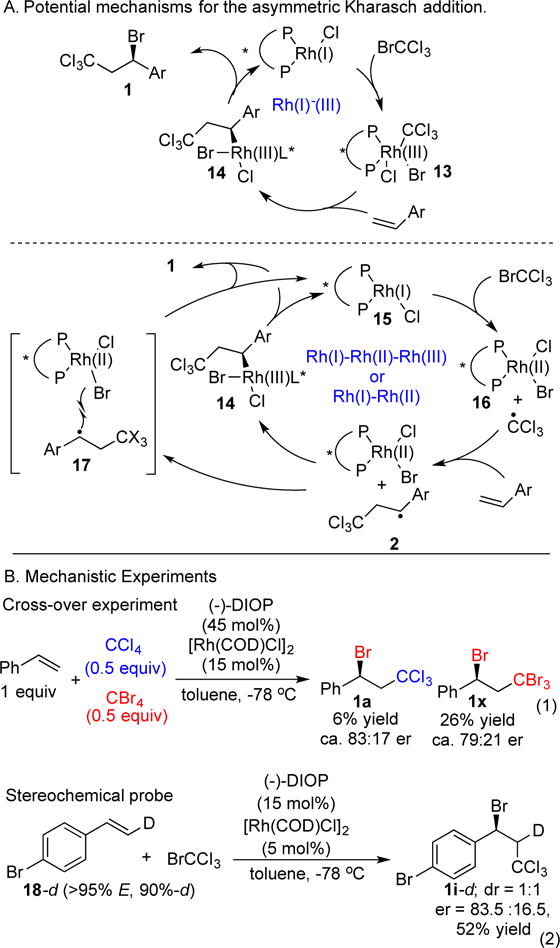

Two general mechanisms for the asymmetric ATRA appeared reasonable, one closed shell and one radical in nature. Shown in Figure 5A is a Rh(I)-Rh(III) cycle featuring oxidative addition to Br-CX3 to give a Rh(III) complex 13. Stereospecific and enantioselective olefin insertion would generate a benzylic Rh species 14. Final reductive elimination would provide the observed product 1. Alternatively, bromine radical abstraction could generate the CX3 radial and a Rh(II)BrCl species 16; addition to styrene could then yield the benzylic radical 2 (Figure 5A, bottom). Radical 2 could recombine with Rh(II) to provide the Rh(III) intermediate 14, which could again undergo reductive elimination to product. Alternatively, it could directly abstract bromine from the Rh(II)BrCl species in an outer-sphere mechanism to give the observed product 1 (see 17).

Figure 5.

A. Potential Rh(I)-Rh(III) catalytic cycle (top) and two catalytic cycles involving radical intermediates (bottom). B. Experiments to probe the mechanism of the addition reaction.

Existing data implicates radical intermediates (Figure 5B). In particular, when styrene was exposed to CCl4 and CBr4 in the presence of ClRh(DIOP), we obtained the cross-over product 1a along with the expected product 1x (eq 1). At cryogenic temperatures, benzyl chloride formation is not observed, but the generation of 1a suggests that CCl3 radical was generated. After addition to styrene, the corresponding benzylic radical abstracted a bromine from a Rh(II)Br species, which was generated from CBr4.[30] The low yields even at high Rh loadings are likely because the (DIOP)RhCl2 formed from CCl4 is catalytically inactive. Similarly, stereochemically pure deuterated styrene 18-d reacted with Br-CCl3 to yield 1i-d as a 1:1 mixture of diastereomers (eq 2). This result rules out the Rh(I)-Rh(III) mechanism because olefin insertion would proceed stereospecifically. By contrast, radical addition to styrene 18-d is expected to yield a mixture of diastereomers, as observed.

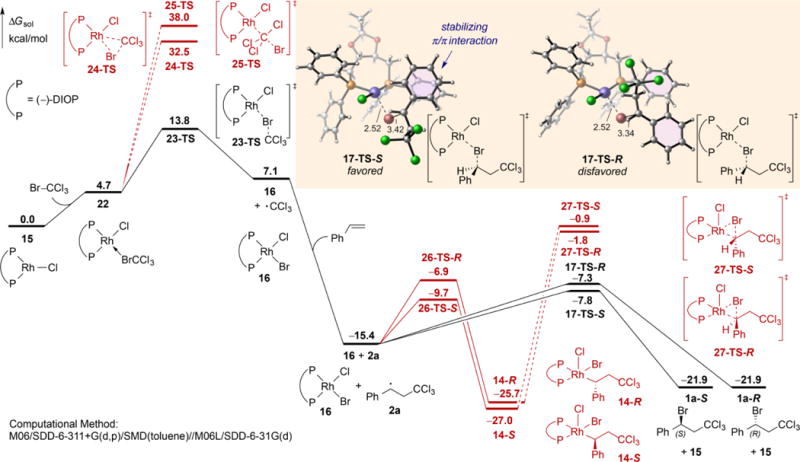

We have used experimental[29] and DFT methods to explore the enantioselective bromination of styrene using [(−)-DIOP]RhCl as the catalyst (Figure 6). The closed-shell Br−CCl3 oxidative addition via either a three-centered TS[31] (24-TS) or an SN2-type linear TS[32,33] (25-TS) both require high activation free energies (32.5 and 38.0 kcal/mol, respectively). In contrast, the radical pathway involving bromine atom abstraction by the Rh(I) catalyst (23-TS) is much more favorable. The resulting CCl3 radical adds to styrene to form the benzylic radical 2a, which then abstracts the bromine atom from the Rh(II) complex 16 (via 17-TS) to form the bromination product (1a) and regenerate the Rh(I) catalyst 15. The Br atom abstraction again requires a very low barrier, 7.6 and 8.1 kcal/mol with respect to 16 and 2a for the formation of (S)- and (R)-1a, respectively. The closed-shell reductive elimination from the Rh(III) intermediate 14 (via 27-TS) and the chain transfer reaction of 2a with BrCCl3 (∆G‡ = 20.2 kcal/mol with respect to 2a, see SI for details) both require much higher barriers. Thus, the DFT calculations suggested a Rh(I)/Rh(II) catalytic cycle with two Br atom abstraction steps. The closed-shell transition states (24-TS, 25-TS, and 27-TS) are all destabilized due to the unfavorable steric repulsions between the Rh center and the CCl3 or benzyl group in the oxidative addition/reductive elimination transition states.

Figure 6.

Computed reaction energy profiles of radical (in black) and closed-shell (in red) pathways of (DIOP)RhCI-catalyzed bromination of styrene.

An interesting feature of the Br atom abstraction transition states (23-TS and 17-TS) is that the Rh−Br−C bond angles are bent (85~105°) rather than linear, as expected in radical abstraction TSs involving two organic radicals. The bent geometry leads to much stronger interactions between the chiral bisphosphine ligand and the substrate in 17-TS, and thus is critical to the chiral induction by the Rh catalyst. As shown in Figure 6, the preferred Br abstraction transition state 17-TS-S is stabilized by a π/π interaction between the Ph on the benzylic radical and one of the Ph groups on the DIOP ligand, while in the disfavored transition state, 17-TS-R, the Ph on the benzylic radical is pointing away from the ligand.

The results described herein establish the first example of a highly enantioselective addition of CX4 reagents to olefins. The addition appears to operate through a mechanism that has not been exploited previously in asymmetric catalysis. Looking forward, it appears likely that the principles outlined here will prove applicable to other enantioselective ATRA reactions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support provided by the NIH (R01GM102403), the Welch Foundation (I-1612), and the University of Pittsburgh. DFT calculations were performed at the Center for Research Computing at the University of Pittsburgh and the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE) supported by the NSF.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Dr. Bo Chena, Department of Biochemistry, UT Southwestern Medical Center, 5323 Harry Hines Blvd, Dallas, Texas 75390-9038 USA

Cheng Fang, Department of Chemistry University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15260 USA; Computational Modeling & Simulation Program University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15260 USA.

Prof. Peng Liu, Department of Chemistry University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15260 USA

Prof. Joseph M. Ready, Department of Biochemistry, UT Southwestern Medical Center, 5323 Harry Hines Blvd, Dallas, Texas 75390-9038 USA

References

- 1.Kharasch MS, Jensen EV, Urry WH. Science. 1945;102:128. doi: 10.1126/science.102.2640.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Pintauer T. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2010;2010:2449. [Google Scholar]; b) Reiser O. Acc Chem Res. 2016;49:1990. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Courant T, Masson G. J Org Chem. 2016;81:6945. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b01058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Studer A, Curran DP. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:58. doi: 10.1002/anie.201505090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2016;128:58. [Google Scholar]

- 4.For alternative approaches to asymmetric halogenation, see:; Cresswell AJ, Eey STC, Denmark SE. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:15642. doi: 10.1002/anie.201507152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2015;127:15866. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nguyen JD, Tucker JW, Konieczynska MD, Stephenson CRJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:4160. doi: 10.1021/ja108560e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atom-transfer polymerization presents another obstacle. See:; Matyjaszewski K, Xia J. Chem Rev. 2001;101:2921. doi: 10.1021/cr940534g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Sibi MP, Manyem S, Zimmerman J. Chem Rev. 2003;103:3263. doi: 10.1021/cr020044l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yan M, Lo JC, Edwards JT, Baran PS. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:12692. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b08856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Miyabe H, Takemoto Y. Chem Eur J. 2007;13:7280. doi: 10.1002/chem.200700864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sibi MP, Ji J, Wu JH, Gurtler S, Porter NA. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:9200. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Espelt L Ruiz, McPherson IS, Wiensch EM, Yoon TP. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:2452. doi: 10.1021/ja512746q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huo H, Harms K, Meggers E. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:6936. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b03399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huo H, Wang C, Harms K, Meggers E. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:9551. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b06010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huo H, Shen X, Wang C, Zhang L, Rose P, Chen LA, Harms K, Marsch M, Hilt G, Meggers E. Nature. 2014;515:100. doi: 10.1038/nature13892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herrmann AT, Smith LL, Zakarian A. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:6976. doi: 10.1021/ja302552e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sibi MP, Hasegawa M. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:4124. doi: 10.1021/ja069245n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beeson TD, Mastracchio A, Hong JB, Ashton K, MacMillan DWC. Science. 2007;316:582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagib DA, Scott ME, MacMillan DWC. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:10875. doi: 10.1021/ja9053338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Y, Du Y, Huang Z, Xu J, Wu X, Wang Y, Wang M, Yang S, Webster RD, Chi YR. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:2416. doi: 10.1021/ja511371a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.a) Binder JT, Cordier CJ, Fu GC. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:17003. doi: 10.1021/ja308460z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Liang Y, Fu GC. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:9523. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b04725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Zuo Z, Cong H, Li W, Choi J, Fu GC, MacMillan DWC. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:1832. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b13211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Schmidt J, Choi J, Liu AT, Slusarczyk M, Fu GC. Science. 2016;354:1265. doi: 10.1126/science.aai8611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gutierrez O, Tellis JC, Primer DN, Molander GA, Kozlowski MC. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:4896. doi: 10.1021/ja513079r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang W, Wang F, McCann SD, Wang D, Chen P, Stahl SS, Liu G. Science. 2016;353:1014. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf7783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang F, Wang D, Wan X, Wu L, Chen P, Liu G. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:15547. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b10468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kainz QM, Matier CD, Bartoszewicz A, Zultanski SL, Peters JC, Fu GC. Science. 2016;351:681. doi: 10.1126/science.aad8313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) Zhu R, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:8069. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b04821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lin JS, Dong XY, Li TT, Jiang NC, Tan B, Liu XY. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:9357–9360. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b04077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lin JS, Wang FL, Dong XY, He WW, Yuan Y, Chen S, Liu XY. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14841. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iizuka Y, Li Z, Satoh K, Kamigaito M, Okamoto Y, Ito J-i, Nishiyama H. Eur J Org Chem. 2007;2007:782. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murai S, Sugise R, Sonoda N. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1981;20:475. [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 1981;93:481. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kameyama M, Kamigata N, Kobayashi M. J Org Chem. 1987;52:3312. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palucki M, Finney NS, Pospisil PJ, Güler ML, Ishida T, Jacobsen EN. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:948. [Google Scholar]

- 28.(1R,2R)-(+)-1,2-Diaminocyclohexane-N, N′-bis(2-diphenylphosphino-1-naphthoyl).

- 29.See supporting information.

- 30.Little halogen exchange occurred on Rh under the reaction conditions.

- 31.Jiao Y, Brennessel WW, Jones WD. Organometallics. 2015;34:1552. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Griffin TR, Cook DB, Haynes A, Pearson JM, Monti D, Morris GE. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:3029. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feliz M, Freixa Z, van Leeuwen PWNM, Bo C. Organometallics. 2005;24:5718. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.