Abstract

Oligodendrocytes are essential regulators of axonal energy homeostasis and electrical conduction and emerging target cells for restoration of neurological function. Here we investigate the role of protease activated receptor 2 (PAR2), a unique protease activated G protein-coupled receptor, in myelin development and repair using the spinal cord as a model. Results demonstrate that genetic deletion of PAR2 accelerates myelin production, including higher proteolipid protein (PLP) levels in the spinal cord at birth and higher levels of myelin basic protein and thickened myelin sheaths in adulthood. Enhancements in spinal cord myelin with PAR2 loss-of-function were accompanied by increased numbers of Olig2- and CC1-positive oligodendrocytes, as well as in levels of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), and extracellular signal related kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) signaling. Parallel pro-myelinating effects were observed after blocking PAR2 expression in purified oligodendrocyte cultures, whereas inhibiting adenylate cyclase reversed these effects. Conversely, PAR2 activation reduced PLP expression and this effect was prevented by brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a pro-myelinating growth factor that signals through cAMP. PAR2 knockout mice also showed improved myelin resiliency after traumatic spinal cord injury and an accelerated pattern of myelin regeneration after focal demyelination. These findings suggest that PAR2 is an important controller of myelin production and regeneration, both in the developing and adult spinal cord.

Introduction

Proteases are emerging as key regulators of neural cell behavior in part by virtue of their ability to activate specific G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) called protease activated receptors (PARs). There are 4 PARs (PAR1-4) and each is expressed in the brain and spinal cord (Striggow et al., 2000; Junge et al., 2004; Vandell et al., 2008), yet we are only just beginning to discover their physiological functions and significance. PARs have seven transmembrane helices coupled to intracellular heterotrimeric G proteins and are activated site-specifically by different extracellular proteases that cleave the PAR extracellular N-terminal domain. This proteolytic activation exposes a new tethered peptide sequence that acts as a ligand, folding back onto the PAR to elicit intracellular signaling. These unique GPCRs are biosensors that can translate dynamic changes in the proteolytic microenvironment into adaptive, or in some cases maladaptive, cellular responses. The roles of PARs as regulators of myelin production are of particular interest since deregulation of their activating proteases is a widespread feature of neurological injury and disease (Gingrich and Traynelis, 2000; Scarisbrick et al., 2008; Radulovic et al., 2013).

Abnormalities in CNS PAR activating enzymes may occur after extravasation and/or secretion by CNS endogenous, or infiltrating immune cells. For example, the canonical activator of protease activated receptor 1 (PAR1), thrombin, is elevated in the CNS in the context of injury and disease (Citron et al., 2000; Arai et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2012; Yoon et al., 2013; Radulovic et al., 2016). Our recent studies demonstrated that PAR1 knockout mice show accelerated patterns of myelination developmentally, thickened myelin sheaths, and higher levels of myelin basic protein in adulthood (Yoon et al., 2015). Moreover, we showed that targeting PAR1 genetically or pharmacologically could effectively reduce dysmyelinating effects of PAR1 over activation (Burda et al., 2013). Given these findings, we hypothesized that protease activated receptor 2 (PAR2) may likewise be highly relevant to the myelination program, particularly since it is preferentially activated by a number of proteases enriched in the CNS, including kallikrein 6 (also referred to as neurosin). Kallikrein 6 is a secreted serine protease that is abundant in CNS white matter (Scarisbrick et al., 1997; Scarisbrick et al., 2000; Scarisbrick et al., 2001; Scarisbrick et al., 2002; Scarisbrick et al., 2006a), and is one of the most up regulated genes (6.5-fold) upon oligodendrocyte differentiation (Cahoy et al., 2008). Kallikrein 6 is also elevated in MS patient sera (Scarisbrick et al., 2008), and CSF (Hebb et al., 2011; Schutzer et al., 2013; Singh et al., 2015), and coordinately elevated along with PAR2 (Noorbakhsh et al., 2006) in MS lesions (Scarisbrick et al., 2001), and after traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI) (Yoon et al., 2013; Radulovic et al., 2015).

The myelin production program is dynamic and tightly controlled by cell-intrinsic and extrinsic factors directing a delicate balance of positive or negative regulatory effects (Kremer et al., 2016). There is an innate capacity for myelin regeneration centered on widely distributed oligodendrocyte progenitors cells (OPCs). OPCs are also present within demyelinated MS plaques, but differentiation failure is common (Smith et al., 1979; Patrikios et al., 2006; Irvine and Blakemore, 2008). Given the accumulating evidence that PAR2 and its activators are also present in MS lesions, we hypothesized that PAR2 may serve as an essential regulator of the myelin production program. Since there are currently no therapies to effectively protect myelin, or to promote myelin regeneration, there is a great need to identify druggable target proteins that are integral regulators governing myelin production.

To evaluate the regulatory actions of PAR2 in myelination, we determined the impact of PAR2 loss-of-function on myelin development and repair using the developing and adult spinal cord as experimental model systems. Our findings reveal that PAR2 is a negative regulator of myelination with PAR2 knockout mice exhibiting an accelerated appearance of oligodendrocytes and proteolipid protein (PLP) during spinal cord development. The regulatory role of PAR2 extended into adulthood with thicker myelin membranes in PAR2 knockout mice, including higher levels of myelin basic protein (MBP). Evidence is presented that genetic or pharmacological blockade of PAR2 removes a physiologic brake to unleash an adenylate cyclase-linked myelination program that is associated with elevations in ERK1/2, and which can be modulated by BDNF. Moreover, genetic targeting of PAR2 fostered myelin regeneration in the adult spinal cord, and was associated with myelin preservation after traumatic spinal cord injury. These are the first studies to identify PAR2 as a key suppressor of myelination, both in the developing and adult spinal cord, and to identify this unique receptor as a potential new drug target to promote myelin protection and repair.

Materials and Methods

Animal care and use

Mice genetically deficient in PAR2 (PAR2-/-, B6.Cg-F2rl1tm1Mslb/J (former B6.Cg-F2rl1tm1Nwb/J, Stock No. 004993 (https://www.jax.org/strain/004993)) were backcrossed to C57BL/6J (Stock No. 000664, https://www.jax.org/strain/000664) for more than 40 generations (Radulovic et al., 2015). All mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). PAR2+/+ littermates served as controls. An equal number of male and female mice were used in studies examining the impact of PAR2 on myelin development in vivo and in vitro and in the studies of lysophosphatidylcholine-medicated focal demyelination and remyelination. Studies examining the impact of PAR2 on recovery after traumatic spinal cord injury involved female mice (Radulovic et al., 2015). All animal experiments were carried out with adherence to NIH Guidelines for animal care and safety and were approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Developmental regulation of PAR2 in the spinal cord

To begin to address the significance of PAR2 to myelination of the spinal cord, we quantified the expression of PAR2 RNA in the spinal cord of mice at P0, 7, 21 or 45 using real time PCR (Radulovic et al., 2015). RNA was isolated using RNA STAT-60 (Tel-Test, Friendswood, TX) and stored at -70 C until the time of analysis. Amplification of the housekeeping gene 18S in the same RNA samples was used to control for loading. Real-time PCR amplification in each case was accomplished using primers obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA), or Applied Biosystems (Grand Island, NY), as detailed in Table 1, on an iCycler iQ5 system (BioRad, Hercules, CA). In addition, we localized PAR2 (sc-8205, RRID: AB_2101309, Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA) to Olig2 (Ab9610, RRID:AB_10141047, Millipore, Temecula, CA) or CC-1-postive cells (adenomatous polyposis coli, OP80, RRID:AB_213434, Millipore, Temecula, CA) within the spinal cord white matter at the P21 peak of myelination, using immunofluorescence techniques. Stained sections were cover slipped with Hardset containing DAPI (Vector, Burlingame, CA) and digitally imaged (Olympus BX51 microscope, Olympus, Center Valley, PA). Counts were made of either Olig2 or CC-1+ cells with a DAPI stained nucleus within the entire dorsal column of at least 3 mice at each time point without knowledge of genotype.

Table 1. Primers used for quantitative real-time PCR.

| Gene | Accession number | Primer Sequence Forward/Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| MBP | NM_001025251 | CCAGTAGTCCATTTCTTCAAGAACAT/ GCCGATTTATAGTCGGAAGCTC |

| NogoA | NM_024226.4 | Applied Biosystems, Assay ID: Mm00445861_m1 |

| Olig2 | NM_016967 | Assay ID: Mm.PT.56a.42319010 |

| PLP | NM_011123.2 | TCTTTGGCGACTACAAGACCAC/ CACAAACTTGTCGGGATGTCCTA |

| PAR2 | NM_007974.3 | CCGGACCGAGAACCTTG / CGGAAGAAAGACAGTGGTCAG |

| Rn18S | NR_003278.3 | Applied Biosystems, Assay ID: Mm03928990_g1 |

All primers were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) unless otherwise indicated.

Quantification of oligodendrocyte number in the developing mouse spinal cord

To determine the impact of PAR2 on the number of OPCs and mature oligodendroglia over the course of spinal cord myelin development, we enumerated Olig2 (Ab9610, Millipore) or CC-1/APC 1 (Ab16794, Abcam) immunopositive cells in 5 μm paraffin sections through the dorsal columns and in in the lateral white matter columns at P0, 7, 21, or 45. Olig2 is a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor expressed by OPCs and oligodendroglia at the early stages of differentiation, whereas CC-1 is associated only with the mature phenotype (Ligon et al., 2006; Kuhlmann et al., 2008; Funfschilling et al., 2012). Immunoperoxidase stained sections were cover slipped with DPX Mountant (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), nuclei counterstained with 0.5% methyl green (Sigma-Aldrich), and all cells with a visible nucleus were counted from digital images. Counts of either Olig2 or CC-1+ cells with a methyl green stained nucleus were made within the entire dorsal column, or within the lateral column white matter, of at least 3 mice at each time point without knowledge of genotype.

Quantification of myelin protein expression using Western blot

Western blots were used to quantify myelin abundance and signaling proteins. Whole spinal cords were harvested from three individual PAR2+/+ or PAR2-/- mice on postnatal day (P) 0, 7, 21 or 45 (adulthood). Spinal cords at each time point were collectively homogenized in radio-immunoprecipitation assay buffer and 25 μg of protein resolved on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Multiple electroblotted membranes were used to sequentially probe for antigens of interest, including myelin proteins PLP (Ab28486, RRID:AB_776593, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), MBP (MAB386, RRID:AB_94975, Millipore), and CNPase (MAB326, Millipore); oligodendrocyte proteins, Olig2 (Ab9610, Millipore); neuron specific proteins, Neurofilament H or L (N4142, RRID:AB_477272; N5139, RRID:AB_477276, Sigma-Aldrich); or the phosphorylated or total protein forms of select signaling proteins, ERK1/2 (9101S, RRID:AB_331646; 9102S, RRID:AB_330744, Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA), or protein kinase B (AKT, 4058L, RRID:AB_331168; 9272S, RRID:AB_329827, Cell Signaling Technology). Membranes were also re-probed for β-actin (NB600-501, RRID:AB_10077656, Novus Biological, Littleton, CO, USA) to further control for loading. The relative optical density (ROD) of each protein of interest was normalized to that of Actin, or in the case of pERK1/2 or pAKT to total ERK1/2 or AKT, respectively. The mean and standard error (s.e.) of ROD readings across at least 3 independent Westerns for each antigen of interest was used for statistical comparisons (Yoon et al., 2013).

Myelin RNA and protein expression by OPCs and oligodendroglia in vitro

To determine whether the absence of PAR2 may directly impact myelin expression, we used real time reverse transcription PCR to establish the level of oligodendrocyte associated gene transcripts in OPCs freshly shaken from PAR2+/+ or PAR2-/- mixed glial cultures (0 h), or after a 72 h period of differentiation in vitro. The level of PAR2 RNA expression was determined in parallel. Mixed glial cultures were prepared from the cortices of P1 mice according to a modified McCarthy and de Vellis protocol (Burda et al., 2013). 0 h OPC RNA was obtained from cells immediately after shaking from 10 day-in-vitro mixed glial cultures. Alternatively, OPCs were differentiated for 72 h prior to RNA isolation by plating at 3 × 104/cm2 cells per well on poly-L-lysine (PLL, 10 μg/mL) coated 6-well plates in Neurobasal A media containing 1% N2, 50 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin, 2 mM Glutamax, 1 mM sodium pyruvate and 0.45% glucose.

The impact of PAR2 gene deletion on the expression of PLP protein in vitro was determined by comparing PLP-immunoreactivity (Ab28486, Abcam) in 72 h differentiated PAR2+/+ or PAR2-/- oligodendrocytes plated at 4 × 104/cm2 on PLL coated 12 mm glass cover slips. Five 20× fields encompassing the poles and center of each coverslip were captured digitally and Image J software was used to determine the ROD of somal PLP staining, as well as somal area. The mean number of PLP+ cells was also enumerated and expressed as a ratio of the number of DAPI cells present in each field. Cell culture studies were performed in triplicate and the mean and standard error across three coverslips per condition quantified and presented. All experiments were repeated at least twice with independent cell culture preparations with similar results.

The impact of increasing of decreasing PAR2 activity on myelin gene expression in purified cultures of oligodendrocytes, was determined by application of a PAR2-activating peptide (PAR2-AP, SLIGRL-amide, 100 μM Peptides International, Lexington KY) (Vandell et al., 2008), or a PAR2 antagonist (GB88, 5 μM, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia) (Barry et al., 2010; Lohman et al., 2012a; Lohman et al., 2012b). In each case, freshly isolated OPCs were plated and allowed to adhere for 3 h before application of the PAR2 agonist, or antagonist, for a 72 h period of differentiation. The contribution of adenylate cyclase to the pro-myelinating effects of GB88 was determined by co-application of the adenylate cyclase inhibitor SQ22536 in parallel experiments (100μM, 568500, Sigma-Aldrich). In addition, we evaluated whether BDNF, a neurotrophin well recognized to participate in synaptic plasticity in a cAMP-dependent manner (Ji et al., 2005), and to exert promyelinating effects (Fulmer et al., 2014), can overcome the ability of PAR2-activation to suppress myelin gene expression. BDNF (10 ng/ml, Peprotech Rocky Hill, NJ) or SQ22536 were co-applied with agonists or antagonists. The level of RNA encoding PAR2, MBP, PLP, NogoA, or Olig2 was determined in 0.10 μg of RNA in triplicate using an iCycler iQ5 system (BioRad) with primers described in Table 1 (Yoon et al., 2015). Results were repeated twice from independent cell preparations with parallel results. The relative amount of RNA in each case was normalized to the constitutively expressed gene Rn18S.

Quantification of spinal cord cAMP

To test the hypothesis that PAR2 may suppress myelin production by blocking the activity of adenylate cyclase, we measured levels of the second messenger cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) in the spinal cord of PAR2+/+ and PAR2-/- at the P21 peak of myelin production. cAMP levels were quantified using a direct cAMP ELISA kit (Enzo Life Sciences, Inc., Farmingdale, NY).

Analysis of myelin thickness

The thickness of myelin sheaths was determined by structural and ultrastructural analysis of the spinal cord dorsal column white matter at P45. Mice were perfused with Trump's fixative (4% formaldehyde with 1% glutaraldehyde, pH 7.4) and a 1 mm segment of the cervical spinal cord was osmicated and embedded in araldite. Myelin sheath thickness in the dorsal column of the cervical spinal cord at P45 was quantified in ultrathin (0.1 μm) sections taken from araldite blocks using a JEM-1400 Transmission Electron Microscope (JEOL USA, Inc., Peabody, MA). Images were captured at 8000X without knowledge of genotype and included 6 fields across the dorsal-ventral axis of the dorsal column. G-ratios were calculated from all myelinated axons in each image and this included axons with diameters ranging from 0.6 to 6 um. Across 3 animals per time point this resulted in measurement of roughly 2300 myelinated fibers for each genotype. Measurements of axon diameter (d) and myelin fiber diameter (D) were made by including axons of all diameters using Image J software and presented as mean g-ratio (d/D), or myelin thickness ± s.e. Since very few axons were ≥ 4 μm, the mean values calculated in each case included only those axons < 4 um. This analysis parallels methods used in in prior studies (Furusho et al., 2012; Ishii et al., 2012; Ishii et al., 2013), facilitating comparison of results.

Evaluation of locomotor activity in PAR2+/+ and PAR2-/- mice

Potential differences in locomotor activity between PAR2+/+ and PAR2-/- mice were evaluated using a Comprehensive Laboratory Animal Monitoring System (Columbus Instruments, Columbus OH). Animals were housed in the system and total activity, ambulatory activity, and rearing data collected for a period of 72 h that included a 24 h period of acclimation followed by 24 h fed and 24 h fasted periods. The mean activity across genotypes in each case (PAR2+/+, n=11 or PAR2-/-, n=12) was analyzed for light and dark periods under both fed and fasted conditions.

Compression Spinal Cord Injury

The effect of PAR2-loss-of-function on spinal cord myelin after traumatic injury was examined in mice with contusion-compression SCI as previously described (Radulovic et al., 2015). Briefly, SCI at the level of L2/L3 was generated in twelve-week old (19-23 g) adult female PAR2+/+ or PAR2-/- mice by application of a modified aneurysm clip (FEJOTA™ mouse clip, 8g closing force) (Joshi and Fehlings, 2002; Yu and Fehlings, 2011; Radulovic et al., 2013). This model generates a severe injury with both an initial contusion as well as a persistent dorsal and ventral compression that results in robust neuroinflammatory responses, astrogliosis and axon degeneration (Yu and Fehlings, 2011). Analysis of changes in myelin in PAR2+/+ and PAR2-/- mice were made in the same protein homogenates and tissue specimens that were used for examination of inflammatory astrogliosis, neurodegenerative responses, and neurobehavioral recovery reported in our recent publication demonstrating improvements in neurobehavioral outcomes in mice lacking the PAR2 gene. Here we extend these studies to additionally determine the expression of MBP at 3 and 30 dpi in spinal segments encompassing the injury epicenter, above and below. Also, tissue sections from additional groups of wild type and PAR2-/- mice at 31 dpi were immunostained to quantify potential differences in the number of Olig2 and CC-1 oligodendrocytes.

Lysophosphatidyl choline model of remyelination

To determine the impact of PAR2 on myelin regeneration, 6 μl of a 1% solution of lysophosphatidyl choline (L-4129, Sigma-Aldrich) was injected into the dorsal column of 12 wk old PAR2+/+ or PAR2-/- male or female mice, without knowledge of genotype. In each case, mice were anesthetized with ketamine (1mg/kg, Fort Dodge Animal Health, Fort Dodge, IA) and xylazine (0.125 mg/kg, Akom, Inc., Decatur, IL) and a dorsal laminectomy performed between the T6 and T9 vertebrae, allowing for lysolecithin injection at T11-T12. All mice were randomized prior to surgery and the surgeon blinded to genotype. Lysolecithin in saline was injected into the dorsal column using a 30 to 70 μm glass micropipette at a rate of 1.2 μl/min using a stereotaxic microinjection system (Stoelting, Inc., Wood Dale, IL). Buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg, Hospira, Lake Forest, IL) was given intraperitoneally postoperatively to minimize discomfort. Following a 14 d period of recovery mice were perfused transcardially with 4% paraformaldehyde. A dorsal laminectomy exposing the region of injection was performed and 2 mm of spinal cord surrounding the injection site collected, with the rostral 1 mm embedded in paraffin and the caudal 1 mm embedded in araldite. Each 1 mm segment was angled to ensure tracking of the injection site that consistently contained the largest lesion. First, the 1 mm of spinal cord rostral to the injection site was embedded in paraffin to confirm successful lesion and quantify CC-1 and Olig2+ cells. Fifty serial 6 μm paraffin sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin to identify the segmental level with the largest lesion. Serial sections adjacent to that with the largest lesion were then immunostained for Olig2 or CC1 and quantified as described above. Lesions studied were between 0.2 and 0.8 mm2. Any mice in which lesions contained surgical damage, such as hemorrhage or a visible needle track were not included in the study. Next, the 1 mm block immediately below the site of lysolecithin injection was osmicated using 1% osmium tetroxide (0223B, Polysciences, Warrington, PA), followed by a series of alcohol dehydrations before being embedded in araldite (18050, Ted Pella, Redding, CA). Twenty, 1 μm sections were cut from each araldite block, slide mounted, and stained with 4% p-phenylenediamine (P6001, Sigma-Aldrich) to identify myelin sheaths. Images through the site of focal demyelination were taken at 60× (Olympus BX51 microscope, Olympus, Center Valley, PA) and montaged as a complete lesion in Adobe Photoshop. The area of demyelination was measured and counts of remyelinated axons, that is those with a lightly stained and thin myelin sheath, were made without knowledge of genotype and expressed as the number of remyelinated axons per mm2 of lesion.

Statistical comparisons

All data were expressed as mean ± s.e.. Comparisons between multiple groups were made using a One-Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and the Newman Keuls post-hoc test. When multiple comparison data was not normally distributed, the Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA on Ranks was applied with Dunn's method. For pairwise comparisons between two groups two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test was applied. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Quantification of results in all experiments was performed without knowledge of genotype.

Results

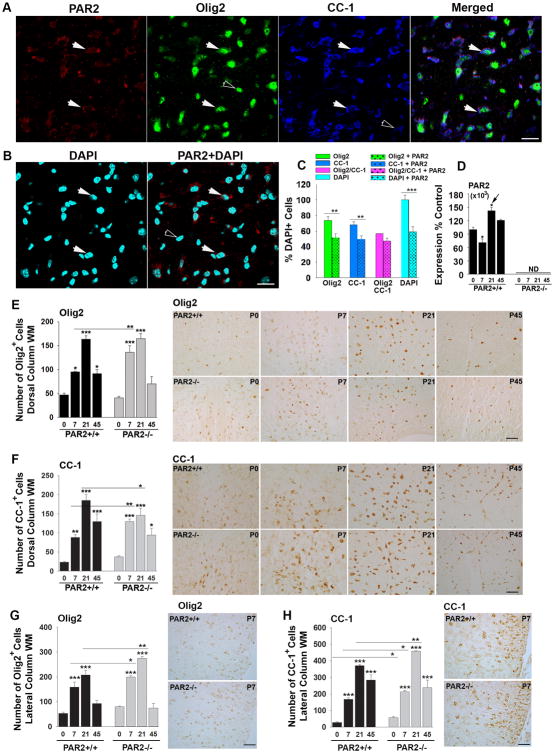

PAR2 loss-of-function increases oligodendrocyte numbers in early development

The highest levels of PAR2 expression in the developing spinal cord occurred at P21 when levels were 1.4-fold higher than those observed on P0 (Fig. 1, P < 0.01, NK). At P7, there was a slight reduction in PAR2 expression compared to that observed on P0 (P < 0.001, NK). To shed light on any differences in PAR2 expression associated with OPCs at early stages of myelin production compared to mature myelinating cells, we used immunofluorescence techniques to localize PAR2 to Olig2+ or CC-1+ oligodendrocytes, respectively, at the P21 peak of myelin production. First, we observed that 59 ± 6% of all DAPI+ cells in the spinal cord dorsal column were PAR2+. Next, we found that 73.8 ± 5% of all DAPI+ cells were Olig2+, 69 ± 4% were CC-1+, and 57 ±3% were both Olig2 and CC-1+. Of the PAR2+ cells, 52 ± 5% were Olig2+, 50 ± 4% were CC1+, and 47% ± 4% were positive for all 3 markers. These findings suggest that at the P21 peak of spinal cord myelination, approximately equal numbers of OPCs and young oligodendrocytes (Olig2+), and mature CC-1+ oligodendrocytes, express PAR2. While these results suggest that the majority of PAR2+ cells in spinal cord white matter are oligodendrocytes, approximately 12% of all PAR2+ cells were not stained for either oligodendrocyte marker. Based on prior studies it is likely that the non-myelin related PAR2+ cell types in the spinal cord white matter are astrocytes or microglia (Noorbakhsh et al., 2006; Radulovic et al., 2015).

Figure 1. PAR2 loss-of-function results in accelerated oligodendrocyte generation and differentiation.

(A) Immunofluorescence for PAR2 in the dorsal column white matter at the P21 peak of spinal cord myelination shows localization to roughly equal numbers of Olig2+ and CC-1+ oligodendrocytes (C). Double labeled cells are indicated by solid arrowheads, while singly labeled cells are indicated by unfilled arrow heads. Approximately 59 ± 6% of all dorsal column cells were PAR2-immunoreactive (B, C). (D) The expression of PAR2 RNA in the developing spinal cord dipped at P7 and peaked at P21. Counts of Olig2- or CC-1-immunopositive cells in spinal cord dorsal column (E and G), and in the lateral column white matter (F and H) were increased across the postnatal period in mice with PAR2 loss-of-function (P ≤ 0.02, Newman Keuls). Parallel elevations in Olig2 protein were observed by Western blot (see Fig. 2A and E). (*P < 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001 Newman Keuls; ND, not detected). (Scale bar B = 20 μm; C and D = 50 μm).

To determine whether increases in PLP and MBP protein in the spinal cord of PAR2-/- mice reflect potential increases in myelin protein expression per cell, or alternatively, more myelin producing oligodendroglia, we quantified the number of Olig2 and CC-1-immunopositive cells (Fig. 1E to H). The number of Olig2+ cells in the dorsal column white matter was 1.4-fold greater in PAR2-/- at P7 compared to wild type controls (P = 0.007, NK, Fig. 1E). Olig2+ cells were also elevated in the lateral column white matter at P7 and at P21 (P < 0.04, NK, Fig. 1G). Overall spinal cord Olig2 protein levels detected by Western blot were also higher in spinal cords of PAR2-/- compared to PAR2+/+ mice at P7 (2.2-fold, P < 0.001, NK, Fig. 2E). The number of CC-1-immunoreactive mature oligodendrocytes was also increased on P7 in the dorsal column white matter of PAR2-/- mice (1.2 to 1.5-fold, P = 0.02, NK, Fig. 1F). The number of CC-1-positive oligodendrocytes was 1.3-fold lower in PAR2-/- mice at P21 compared to PAR2+/+ mice (P < 0.05, NK). In the lateral column white matter, elevations in CC-1+ oligodendrocytes were observed on P0, P7 and P21 (1.3 to 2-fold, P ≤ 0.03, NK, Fig. 1H). Despite the accelerated appearance of Olig2+ and CC-1+ oligodendrocytes in PAR2 knockout mice, numbers were identical across genotypes at P45.

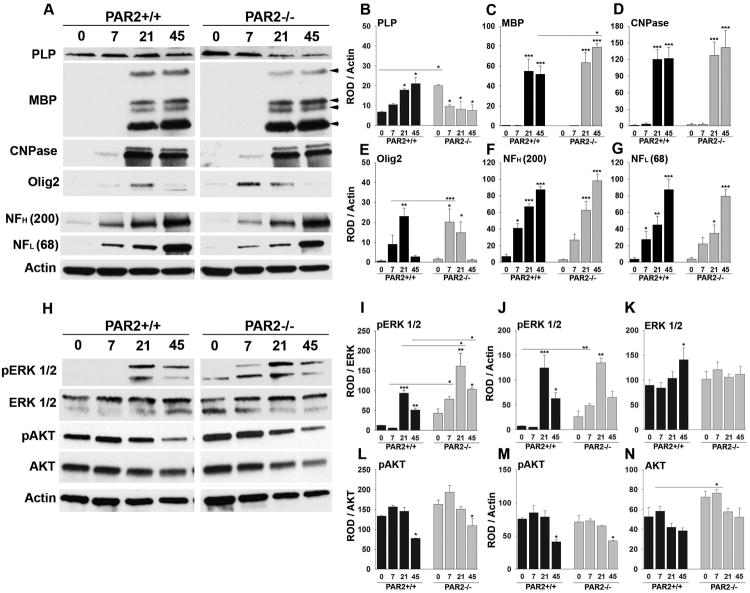

Figure 2. Enhanced expression of myelin-associated proteins and pro-myelination signaling occurs in the spinal cord of mice with PAR2-loss-of-function.

Western blots of whole spinal cord homogenates and associated histograms (A to G) illustrate that mice lacking PAR2 show significant increases in the expression of PLP at P0 (B) and MBP by P45 (C). Higher levels of Olig2 protein occurred in the PAR2-/- spinal cord on P7 compared to wild type. Increases in the pro-myelination signaling pathway ERK1/2 was also observed by P7, on P21, and in adulthood (H, I). No significant differences in NFH (F), or NFL (G), were observed in the same spinal cord samples. Levels of total AKT were significantly elevated in PAR2-/- mice on P7 (N). ROD readings for pERK and pAKT were normalized to total protein or to Actin (I to K). Actin was probed on every membrane to control for loading and is shown for the corresponding membrane in the lower panel in (A) and (H). (*P < 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001 Newman Keuls; ND, not detected).

The Western blots presented in Fig. 2 showing quantification of myelin associated proteins and signaling molecules in wild type and PAR2 knockout mouse spinal cords, were blotted alongside protein from PAR1 knockout spinal cords. The blots related to developmental changes in myelin proteins in PAR1 knockout spinal cord were published versus wild type mice in Yoon et al., 2015. Therefore, the blots for PLP, CNPase, Olig2, neurofilament ERK1/2 and actin in wild type mice (only) can also be found in our prior publication. The findings related to PAR2 have not been previously published.

PAR2 loss-of-function accelerates PLP and Olig2 expression in the perinatal spinal cord and results in higher MBP levels in adulthood

To critically evaluate the role of PAR2 loss-of-function in myelin development in vivo, we directly compared the onset, magnitude and duration of expression of myelin proteins, including the two major myelin structural proteins, proteolipid protein (PLP) and myelin basic protein (MBP), in the spinal cord of PAR2+/+ and PAR2-/- mice at P0 through P45 (adulthood) (Fig. 2). Consistent with a regulatory role for PAR2 in onset of myelin protein expression, spinal cord PLP levels were 3-fold higher at P0 in PAR2-/- mice relative to PAR2+/+ mice (P = 0.04, NK). MBP protein levels were very low in both genotypes at birth, but by P45 MBP levels were 1.5-fold higher in mice lacking PAR2 relative to their wild type counterparts (P=0.002, NK). These data highlight an important role for PAR2 in regulating the onset of myelin protein expression and the ultimate abundance of major myelin proteins in the developing and adult spinal cord.

Levels of Olig2 protein were comparable between PAR2+/+ and PAR2-/- mice at birth, but by P7 were 2.2-fold higher in mice lacking PAR2 relative to PAR2+/+ mice (P < 0.001, NK, Fig. 2). The peak of Olig2 expression was accelerated in PAR2-/- mice, occurring at P7 compared to P21 in mice with an intact PAR receptor. There was a substantial loss of Olig2 protein expression after P21 in both genotypes. Substantial elevation in spinal cord 2′, 3′-cyclic-nucleotide 3′-phosphodiesterase (CNPase) was also observed between birth and P21, but no differences were seen across genotypes. As expected, there was a progressive increase in the abundance of both the heavy and light chains of neurofilament protein (NFH or NFL) from birth through adulthood, and these changes were identical in the spinal cord of PAR2+/+ and PAR2-/- mice.

PAR2 loss-of-function increases spinal cord ERK1/2 signaling

Since extracellular-signal-related kinase (ERK1/2) and AKT (protein kinase B) are known positive regulators of myelinogenesis, (Czopka et al., 2010; Harrington et al., 2010; Guardiola-Diaz et al., 2012; Ishii et al., 2012; Fyffe-Maricich et al., 2013; Ishii et al., 2013), we next investigated the impact of PAR2 gene deletion on their signaling. Consistent with ERK1/2 signaling being associated with enhanced myelination, we observed significantly higher levels of activated ERK1/2 in the spinal cords of PAR2-/- mice at P7, P21 and adulthood, compared to wild type controls (Fig. 2H to K). Elevated expression of activated ERK1/2 peaked in both genotypes at P21, but was 1.7-fold higher in the spinal cord of mice with PAR2 loss-of-function (P = 0.01, NK). Elevated levels of activated ERK1/2 were also detected in PAR2-/- spinal cords on P7, when levels were 12.9-fold higher than wild type (P = 0.02, Newman Keuls). Levels of total AKT were higher in PAR2-/- spinal cords on P7 (P = 0.01, NK). There was also a strong trend for increased levels of phosphorylated AKT at P0 and P7, but these elevations did not reach the level of statistical significance. While we do not assume that all of the elevations in ERK and AKT signaling observed in the developing spinal cord are associated with myelinating cells, the temporal changes observed do correspond to the accelerated patterns of myelin production observed in the spinal cords mice lacking PAR2. Future studies will be needed to immune localize elevations in ERK and AKT signaling to myelinating cells.

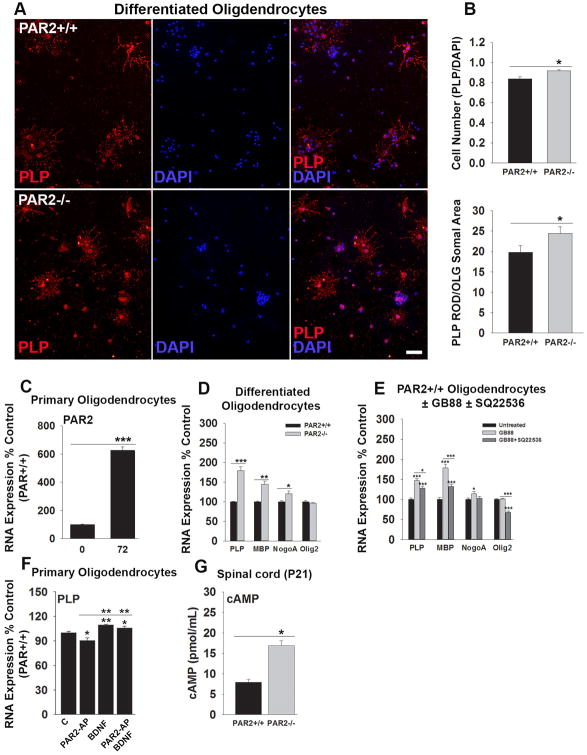

PAR2 loss-of-function enhances oligodendrocyte differentiation in vitro

To determine whether reductions in oligodendrocyte PAR2 may directly impact oligodendrocyte differentiation, we evaluated the appearance of myelin-associated proteins in OPCs, derived from wild type or PAR2-/- mice, in cell culture (Fig. 3). First, we show that PAR2 is expressed by OPCs in culture and increases 6-fold over a 72 h period of differentiation (P = 0.00004, Student's t-test). Over the same period of differentiation, the number of oligodendrocytes immunopositive for PLP was approximately 10% greater in PAR2-/- compared to PAR2+/+ cultures (P = 0.01, Student's t-test). Also, oligodendrocytes lacking PAR2 expressed 1.2-fold higher levels of PLP protein (P < 0.05, Student's t-test). In addition, 72 h differentiated oligodendrocytes lacking PAR2 expressed higher levels of PLP (1.8-fold, P = 0.002), MBP (1.5-fold, P = 0.006) and NogoA RNA (1.2-fold, P = 0.02, Student's t-test). Near parallel increases in myelin associated genes were observed when PAR2+/+ OPCs were treated with a PAR2 small molecule inhibitor (GB88, 5 μM) with a 1.6-fold increase in PLP (P = 0.005), a 1.9-fold increase in MBP (P = 0.03), and a 1.2-fold increase in NogoA (P = 0.002, Student's t-test). A small molecule inhibitor of adenylate cyclase (SQ22536, 100 μM) significantly reduced GB88-mediated increases in myelin-associated gene expression (P ≤ 0.03, Student's t-test).

Figure 3. PAR2 suppresses myelin associated gene expression in oligodendrocyte progenitor cells in an adenylate cyclase dependent manner.

Photomicrographs and associated histograms (A, B), show that PAR2-/- OPCs differentiated for 72 h show a greater mean number of PLP-immunoreactive cells per cover slip, and more PLP per cell, compared to PAR2+/+ cells (P = 0.01, Student's t-test, Scale bar = 20 μm). (C) PAR2 RNA expression increased as OPCs differentiate in cell culture (P < 0.001), reminiscent of what we see in the intact spinal cord (see Fig. 1D). PAR2-/- OPCs (D), or those treated with a PAR2 small molecule inhibitor (E, GB88 5 μM), also show a significant increase in PLP, MBP and NogoA expression after a 72 h period of differentiation (P ≤ 0.03, Student's t-test). Application of an adenylate cyclase small molecule inhibitor (E, SQ22536 100 μM) reversed increases in myelin associated gene expression seen with PAR2 blockade (P ≤ 0.03, Student's t-test). (F) A PAR2 activating peptide (PAR2-AP, 100 μM) suppressed PLP expression, an effect that was overcome by co-application of the cAMP activating, pro-myelination growth factor, BDNF (10 ng/ml). (G) cAMP was elevated in the spinal cord of PAR2-/- mice at the P21 peak of myelination relative to their wild type littermates (P = 0.04, Student's t-test). (*P < 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, Student's t-test).

Treatment of OPCs with a selective PAR2 activating peptide (PAR2-AP) reduced increases in PLP RNA expression observed after a 72 h period of differentiation by approximately 10% (P < 0.05, Student's t-test). BDNF increased PLP expression by 10% over the same period (P = 0.007), and when co-applied with PAR2-AP, prevented its dysmyelinating effects (P = 0.03, Student's t-test).

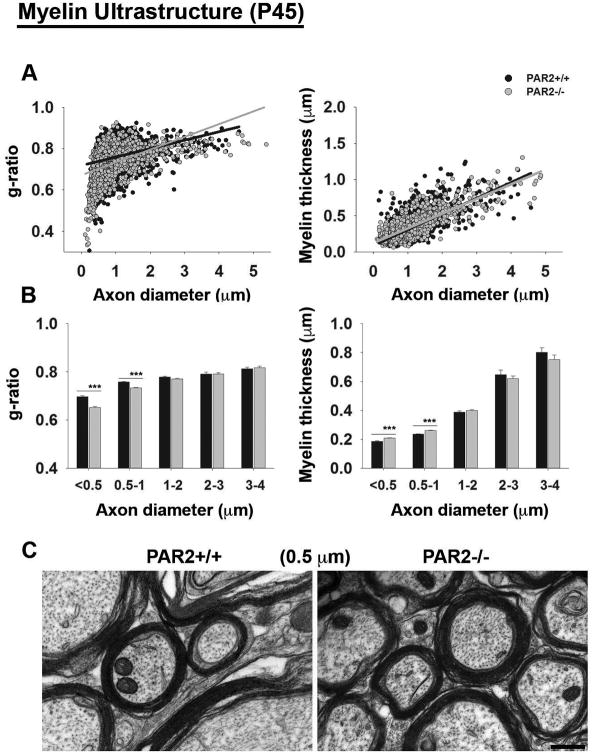

PAR2 regulates myelin thickness in the adult spinal cord

To determine whether increases in myelin protein expression in the adult spinal cord were reflected in myelin thickness, we used ultrastructural approaches to evaluate g-ratios with the dorsal column white matter (Fig. 4). Approximately 70% of all axons in the dorsal column were less than 1 μm and this is where we saw the most significant increases in myelin thickness in PAR2-/- compared to wild type mice (P ≤ 1.5 × 10-6, Student's t-test). The myelin sheaths of mice lacking PAR2 showed reduced g-ratios (0.72 ± 0.002) compared to PAR2+/+ mice on P45 (0.75 ± 0.002, P=0.37×10-43, Student's t-test). Also, myelin thickness was greater in mice lacking PAR2 (PAR2-/- = 0.29 ± 0.003 μm; PAR2+/+ = 0.28 ± 0.003 μm; P=0.01, Student's t-test).

Figure 4. PAR2-loss-of-function enhances myelin thickness in the adult spinal cord.

(A) At P45, mean g-ratios were significantly lower in PAR2-/- mice (0.72 ± 0.002) compared to PAR2+/+ mice (0.75 ± 0.002, P = 0.37×10-43, Student's t-test) and myelin thickness was significantly greater (PAR2-/- = 0.29 ± 0.003 μm; PAR2+/+ = 0.28 ± 0.003 μm; P = 0.01, Student's t-test, n=3 per genotype). (B) Histograms show the mean g-ratios and myelin thickness for axons across a range of diameters, demonstrating that the most significant increases in myelin thickness were observed in axons ranging from 0.5 to 1 μm (P = 1.5 × 10-6, Student's t-test), (Scale bar, C = 0.2 μm). (C) Representative electron micrographs taken from the spinal cord dorsal column white matter of PAR2+/+ or PAR2-/- mice at P45. Micrographs were used to calculate g-ratios and myelin thickness, which were plotted relative to axon diameter.

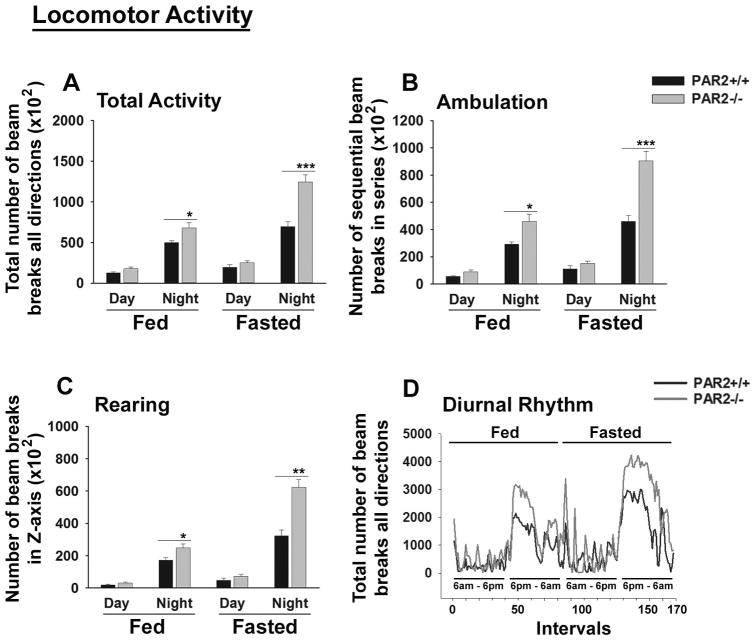

Motor activity in PAR2-/- mice

To determine whether enhancements in spinal cord myelination observed in PAR2-/- mice may result in changes in motor outcomes, we evaluated overall motor activity, ambulation and rearing during diurnal and nocturnal cycles under both fed and fasted conditions using a comprehensive laboratory animal monitoring system (Fig. 5). Overall activity of mice lacking PAR2 was increased at night under fed (1.4-fold) or fasted (1.8-fold) conditions (Fig. 5A). In addition, both nocturnal ambulation (Fig. 5B) and rearing responses (Fig. 5C) were also increased in PAR2-deficient mice under fed or fasted conditions (1.5- to 2-fold, P ≤ 0.05 Student's unpaired t-test, Fig. 5B, C). Despite these differences in nocturnal activity, diurnal rhythms did not differ across genotypes (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5. PAR2 loss-of-function results in increased nocturnal locomotor activity.

A comprehensive laboratory animal monitoring system was used to demonstrate that PAR2-/- mice have (A) higher total nocturnal activity under fed (P = 0.04) or fasted conditions (P = 0.001), (B) higher nocturnal ambulation under fed (P = 0.03) or fasted night conditions (P = 0.009), and (C) higher rearing under fed (P = 0.05) or under fasted night conditions (P = 0.002) (Student's unpaired t-test). (D) Line graph shows total beam breaks during 168, 17 min intervals during the Fed and Fasted 12 h light and dark cycles. The parallel timing of beam break onset and offset between PAR2+/+ and PAR2-/- mice demonstrates that diurnal rhythms were similar between the two genotypes. Also no significant differences were observed in daytime activity, ambulation or rearing under any conditions.

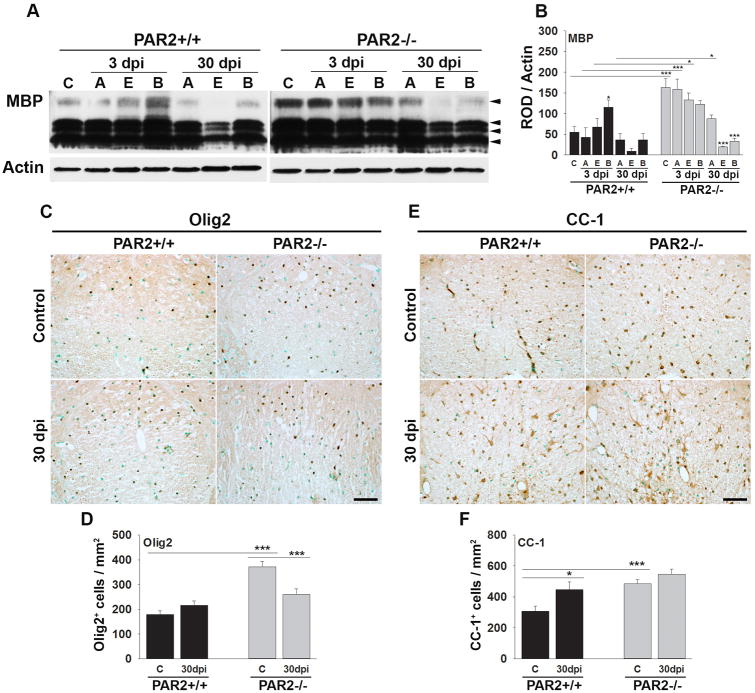

PAR2 loss-of-function improves myelin integrity after traumatic SCI

To determine whether the pro-myelination effects of PAR2 loss-of-function also occur in the context of CNS injury, we compared the appearance of myelin markers in an experimental model of contusion-compression spinal cord injury (Fig. 6). SCI was induced in P90 mice such that all mice were P120 at the 30 dpi end point examined. Mirroring the 1.5-fold elevation in MBP protein observed in the intact spinal cord of P45 PAR2-/- mice relative to PAR2+/+ (Fig. 2), MBP protein levels were 3-fold higher in the uninjured spinal cord of PAR2-/- mice at P120 (P = 0.001, NK). At 3 dpi, MBP protein levels were 3.7-fold higher in spinal segments above the injury epicenter, and 2-fold higher at the injury epicenter, in mice with PAR2 loss-of-function compared to mice with an intact PAR2 signaling system (P ≤ 0.04, NK). At 30 dpi, MBP protein levels above the injury epicenter were 2.4-fold higher in PAR2-/- compared to wild type mice (P = 0.02, NK).

Figure 6. Mice lacking PAR2 show improvements in the abundance of myelin and myelinating cells after traumatic spinal cord injury.

(A) Western blot and associated histogram (B) demonstrates higher levels of myelin basic protein (MBP) in the spinal cord of mice with PAR2 loss-of-function at base line (C, control), and at 3 and 30 dpi. MBP levels were higher in spinal segments at the injury epicenter (E) and above (A) at 3 dpi, and in spinal segments above at 30 dpi in PAR2-/- relative to those with an intact PAR2 signaling system (B, below the injury epicenter). Photomicrographs and associated histograms (C to F), demonstrate that the number of Olig2+- and CC-1+-oligodendrocytes was higher in the spinal cord of PAR2-/- compared to PAR2+/+ mice at baseline (C, control). (Scale bar C and E = 50 μm)

To determine whether differences in myelin abundance in P120 PAR2-/- mice before and after SCI are reflected in differences in the number of myelinating cells, counts of Olig2 and CC-1+ cells were made in spinal segments above the lesion epicenter (Fig. 6). The number of Olig2+-oligodendrocytes was 2.1-fold higher in mice with PAR2 loss of function compared to wild type mice prior to injury (P ≤ 0.001, Student's t-test). In parallel, the number of mature CC-1+-oligodendrocytes was 1.6-fold higher in mice with PAR2 loss-of-function prior to SCI (P = 0.018, Student's t-test). After SCI, there was a trend towards retention of a greater number of Olig2 and CC-1 oligodendrocytes in mice lacking PAR2, but the differences were not statistically significant.

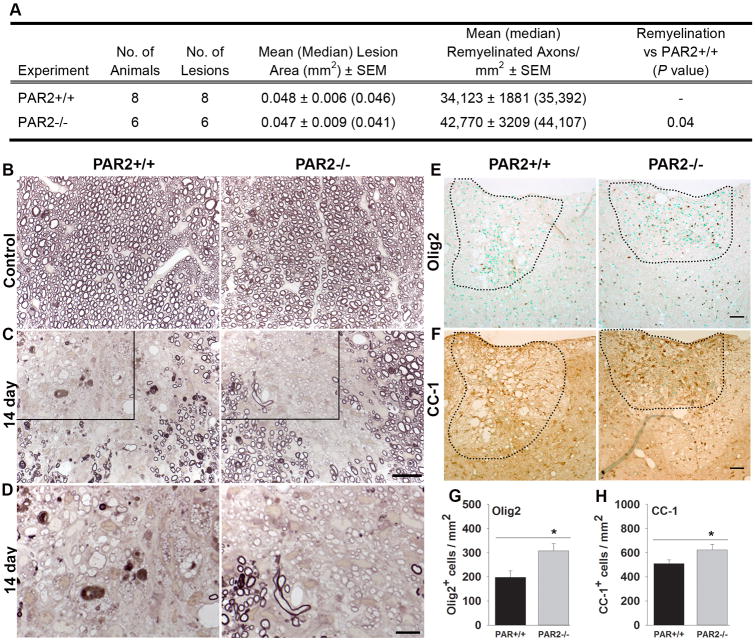

PAR2 loss-of-function facilitates myelin regeneration

The potential impact of PAR2 loss-of-function on myelin repair in the adult spinal cord was evaluated by making counts of remyelinated axons 14 d after lysophosphatidyl choline-mediated induction of a focal demyelinating lesion in the dorsal column white matter (Fig. 7). We first confirmed that mean size of focal demyelination was similar in PAR2+/+ (0.049 ± 0.005 mm2) and PAR2-/- (0.047 ± 0.008 mm2) mice. The mean number of remyelinated axons in PAR2+/+ mice at 14 dpi was 34,123 ± 1881. The mean number of remyelinated axons was increased by 25% at the same time post-lesion in mice with PAR2 loss-of-function, which had a mean of 42,770 ± 3209 remyelinated axons (P = 0.04, Student's t-test). At 14 d after demyelination, focal lesions in mice lacking PAR2 contained 1.6-fold more Olig2+-, and 1.2-fold more CC-1+-immunopositive oligodendrocytes, compared to their wild type counterparts (P ≤ 0.04, Student's t-test). These results suggest that inhibition of PAR2 may be a useful approach to accelerating myelin regeneration in the adult spinal cord.

Figure 7. Myelin regeneration was enhanced in mice with PAR2 loss-of-function.

(A) Remyelinated axons were counted in areas of focal demyelination 14 d after microinjection of lysolecithin into the dorsal column of PAR2+/+ or PAR2-/- mice. The mean number of remyelinated axons per mm2 was increased in mice with PAR2 loss-of-function. Mean lesions sizes were identical across genotypes. (B to D), Photomicrographs show examples of paraphenylenediamine (PPD) stained myelin sheaths in the spinal cord dorsal column white matter of control PAR2+/+ and PAR2-/- mice (B), and in those at 14 d after injection of the demyelinating agent lysophosphatidyl choline (C). Counts of remyelinated axons at 14 d after demyelination demonstrate 25% more remyelinated axons per mm2 in mice with PAR2 loss-of-function (P = 0.04, Student's t-test, see A). Remyelinated axons are identified as those with thinner and more lightly PPD stained myelin sheaths. Boxed area through a 14 d remyelinated lesion (C) is provided at higher magnification (D) to facilitate visualization of remyelinated axons. Photomicrographs show the appearance of (E) Olig2- or (F) CC-1-immunopositive cells in the spinal cord dorsal column 14 d after lysolecithin-mediated demyelination. Sections were counterstained with methyl green to facilitate counting. Areas of myelin loss were outlined based on immunoreactivity for myelin basic protein (not shown)). The mean number of Olig2 and CC-1 oligodendrocytes in areas of myelin loss at 14 d was greater in PAR2-/- compared to PAR2+/+ mice (P ≤ 0.04, Student's t-test). (Scale bar A, B = 20 μm and D = 10 μm; Scale bar E and F = 50 μm).

Discussion

These studies identify PAR2 as a key regulator of myelin development along with myelin resiliency and regeneration in the adult CNS. PAR2 knockout mice exhibit enhancements in myelin production developmentally and after demyelination, suggesting that this receptor serves as an innate suppressor of the myelin production program across the lifespan. In addition, loss-of-PAR2 function supports a level of myelin reserve in the adult spinal cord that renders it more resilient to the demyelinating effects of spinal cord trauma, possibly contributing to the improvements in cellular, molecular, and behavioral outcomes previously observed in PAR2 null mice after SCI (Radulovic et al., 2015). Results demonstrate that PAR2 is uniquely positioned as a target for therapies aimed at improving the capacity for myelin production, preservation, and regeneration in the developing and adult CNS.

PAR2 loss-of-function accelerates the production of oligodendrocytes and PLP in the developing spinal cord and results in higher levels of MBP and thickened myelin sheaths in adulthood. Greater numbers of Olig2- and CC-1-positive oligodendrocytes were observed by P7 in PAR2 knockout mice, but not at earlier time points, suggesting this receptor regulates the speed of oligodendrocyte differentiation rather than exclusively the number of oligodendrocytes generated. In conjunction with this, we observed temporally discrete enhancements in PLP in the spinal cord at birth, and in MBP in adulthood. Thus the removal of a single receptor can specifically impact on the two major myelin structural proteins located on unique chromosomes, suggesting that PAR2 is an integral intersection point capable of serving as a fundamental regulator of unique aspects of myelin production. Despite these changes in myelin, there were no significant alterations in the heavy or light chains of neurofilament at any age examined, suggesting that the enhancements in myelin observed in PAR2-/- mice were not dependent on, nor did they result in obvious changes in axons. The extent to which enhancements in myelination observed in the spinal cord of PAR2-/- mice contribute to the parallel increases observed in locomotor activity will be an important avenue for future investigation.

Consistent with a model in which PAR2 serves as a negative regulator of myelin production, expression of PAR2 in the developing spinal cord dipped transiently at P7, preceding a significant rise in PLP and MBP production. Correspondingly, PAR2 expression peaked at P21, when the highest levels of myelinating cells and myelin production were observed. In parallel, PAR2 expression in purified oligodendrocyte cultures also progressively increased as OPCs differentiated. Elevations in PAR2 seen with oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelin maturation are positioned to constrain the myelin production program. Supporting this, treatment of OPCs with a PAR2 activating peptide suppressed PLP expression. Furthermore, diminishing PAR2 activity in purified cultures of OPCs genetically (PAR2-/-), or pharmacologically (GB88) (Barry et al., 2010), resulted in significantly increased expression of PLP, MBP and NogoA.

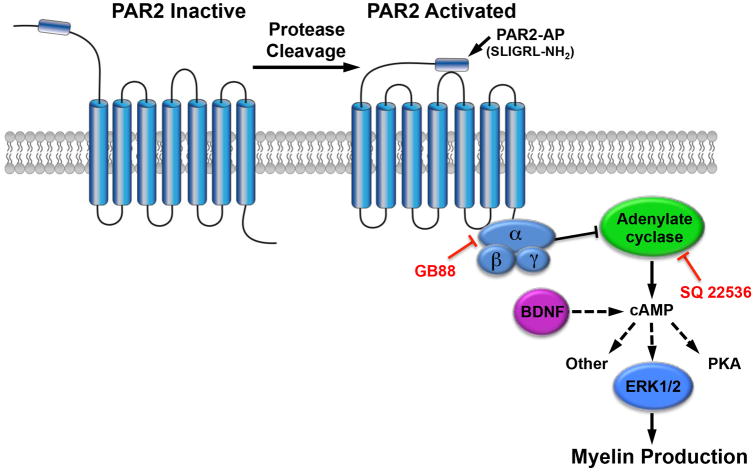

Evidence is presented here to suggest that the mechanism by which PAR2 loss-of-function enhances myelin production is related to an ability to inhibit cAMP production. First, we discovered that cAMP levels are elevated by more than two-fold in the spinal cord of mice lacking PAR2. cAMP is a pleiotropic second messenger generated by adenylate cyclase, an enzyme whose activity can be increased or decreased by a variety of hormone and growth factor signaling mechanisms. With regard to myelination, it is well recognized that increasing adenylate cyclase activity promotes oligodendrocyte differentiation (Raible and McMorris, 1990). While we have not pinpointed the elevations in spinal cord cAMP in PAR2-/- mice to myelinating cells, the current findings taken with prior studies point to a model in which loss-of-PAR2 function diminishes Gαi-mediated inhibition of adenylate cyclase, resulting in increased cAMP and myelin production (Fig. 8). For example, PAR2 is known to signal through Gαi to inhibit adenylate cyclase in smooth muscle cells (Sriwai et al., 2013). Also, we showed that BDNF, a growth factor known to elevate cAMP, prevented decreases in PLP expression observed in OPC cultures treated with a PAR2 activating peptide. We also showed that a small molecule inhibitor of PAR2 (GB88) increases OPC myelin gene expression and that these effects were diminished by an adenylate cyclase inhibitor (SQ22536). Interestingly, the ability of GPR17 (Simon et al., 2016), and GPR37 (Yang et al., 2016) to block myelin production was also recently linked to a G protein-mediated suppression of adenylate cyclase. These findings suggest that PAR2 activators, such as kallikrein 6 that are found in MS lesions (Scarisbrick et al., 2002), and at other sites of neural injury including SCI (Scarisbrick et al., 2006b; Yoon et al., 2013), may impede myelin repair by suppressing adenylate cyclase activity.

Figure 8. Model where PAR2 activation suppresses myelin production by reducing cAMP.

Results collectively point to a model in which PAR2 activation by endogenous proteases, such as kallikrein 6 (Klk6) (Radulovic et al., 2015), impedes the activity of adenylate cyclase and hence cAMP production, thereby reducing myelin production. Supporting this, a PAR2-activating peptide (PAR2-AP, SLIGRL-NH2), reduced PLP expression in primary oligodendrocyte cultures and this effect was overcome by BDNF, a pro-myelinating growth factor that elevates cAMP. Also, blocking the activity of PAR2 by genetic deletion of the receptor increased spinal cord cAMP, and ERK1/2 phosphorylation, and was associated with significant enhancements in markers of myelin membrane differentiation, including PLP and MBP, in vivo and in purified oligodendrocyte cultures. Further linking the promyelinating effects of PAR2 loss-of-function to its ability to inhibit adenylate cyclase, the enhancements in myelin production observed in PAR2-/- OPCs were replicated by application of a PAR2 small molecule inhibitor (GB88) to PAR2+/+ cultures, an effect that was impeded by application of the adenylate cyclase inhibitor SQ22536. Since cAMP is a pleiotropic molecule that also activates PKA, in addition to other signaling pathways, more studies will be needed to fully define the mechanism(s) by which blocking PAR2 enhances myelination developmentally, in addition to myelin regeneration and myelin reserve in the adult spinal cord.

The ‘pro-myelinating’ effects of the PAR2 antagonist GB88 in vitro are encouraging, singling out PAR2 as a new potential therapeutic target for demyelinating conditions affecting the developing and adult CNS. While the signaling pathway(s) that GB88 targets downstream of PAR2 in OPCs to foster myelin gene expression were not studied in detail, the fact that these effects were diminished by SQ22536 suggests that adenylate cyclase plays a role. In other studies, GB88 has been shown to selectively inhibit Gq11, Ca2+ and PKC signaling, and to lead to anti-inflammatory activity in vivo. In addition, GB88 may also activate ERK and Rho, at least in some cell types (Suen et al., 2014). Although the precise signaling mechanisms have not been fully detailed, the current studies taken with findings that GB88 exhibits anti-inflammatory activity in vivo in rodent models of arthritis, (Lohman et al., 2012a) and inflammatory bowel disease, (Lohman et al., 2012b), provides considerable promise that PAR2 small molecule inhibitors have therapeutic potential for a vast range of conditions, including conditions affecting myelin development and myelin regeneration.

Adult mice with PAR2 loss-of-function show improvements in the abundance of MBP at acute and chronic time points after SCI. The preservation of myelin after traumatic SCI in PAR2-/- mice may reflect in part a greater number of Olig2 and CC-1+ oligodendrocytes in the spinal cord at baseline. Also, given the co-ordinate elevations in many proteases capable of activating PAR2, such as kallikrein 6 at sites of spinal cord trauma (Scarisbrick et al., 2006b; Radulovic et al., 2013; Yoon et al., 2013; Radulovic et al., 2015), the absence of PAR2 may protect myelinating cells from protease-mediated myelin loss, including by way of a direct receptor-dependent suppression of myelin gene expression (Burda et al., 2013). Indeed, here we show that selective activation of PAR2 suppresses PLP production in OPC cultures. Altogether, these new findings raise the intriguing possibility that the improvements in molecular, histopathological, and locomotor outcomes that we observe in PAR2-/- mice after SCI (Radulovic et al., 2015), including preservation of corticospinal axons, may relate to improvements conferred by increases in the abundance of oligodendrocytes and their progenitors, and to higher levels of myelin preservation.

The greater quantities of MBP observed in the spinal cord of PAR2-/- mice at 3 and 30 d after SCI may relate to a level of resiliency afforded by higher baseline levels. In addition, we cannot rule out the possibility that enhancements in MBP in PAR2-/- mice at 30 dpi relate in part to improved myelin repair. To test this possibility, we investigated whether genetic deletion of PAR2 impacts myelin regeneration in the adult spinal cord using the lysophosphatidyl choline model of focal demyelination. Consistent with other lines of evidence presented suggesting that PAR2 is a negative regulator of myelination, mice lacking PAR2 showed improvements in the number of remyelinated axons compared to their wild type littermates 14 d after demyelination. Enhancements in myelin regeneration were paralleled by increased numbers of Olig2 and CC-1 positive oligodendrocytes. Taken together these findings demonstrate that blocking PAR2 may be a novel approach to enhancing myelin resiliency and myelin regeneration in the adult spinal cord, raising the possibility of pharmacological modulation of PAR2 as a new therapeutic strategy for treating SCI and other neurological conditions.

One limitation of the current study is that we have used mice with complete PAR2 knockout. While this approach has the potential to mimic the effects of administration of a PAR2 inhibitor, it does not permit us to specifically address the cellular mechanism(s) underlying the promyelinating effects observed. In the CNS, PAR2 is also expressed by at least some neurons, in addition to astrocytes and microglia, especially in the context of injury (Noorbakhsh et al., 2005; Noorbakhsh et al., 2006; Radulovic et al., 2015; Radulovic et al., 2016). Moreover, PAR2 is widely distributed in peripheral organs, including the kidney, spleen and gastrointestinal system (D'Andrea et al., 1998). Thus, while the current findings do demonstrate that mice lacking PAR2 show enhancements in myelination developmentally and after injury in adulthood, whether these effects are dependent on changes in PAR2 in myelinating cells alone, or alternatively, or additionally depend on loss-of-PAR2 function in other cell types, awaits investigation of myelination in mice with cell specific PAR2 knockdown.

We recently reported that mice with PAR1 loss-of-function also show enhancements in spinal cord myelination developmentally (Yoon et al., 2015). It is therefore of interest to compare the enhancements we observe in myelination in PAR2 knockout mice with this prior report. First, immunofluorescence double labeling approaches showed that PAR1 and PAR2 are each expressed by oligodendrocyte progenitor cells, in addition to mature CC-1+ oligodendrocytes. However, in purified cultures of OPCs, PAR1 RNA expression decreased as cells differentiated, while PAR2 increased. In parallel, PAR1 expression was observed to decrease in the spinal cord over the period of postnatal development, while PAR2 increased. While the functional significance of these dichotomies in developmental expression dynamics between the two receptors is not yet known, findings across studies demonstrate that deletion of PAR1 or PAR2 promotes a similar acceleration of the onset of myelination, including higher levels of PLP at birth, a greater number of OPCs early in development, accelerated OPC differentiation, and higher levels of MBP and thicker myelin sheaths in adulthood. Enhancements in the abundance of pro-myelination signaling molecules, ERK1/2 and AKT, were also observed in the spinal cord of mice lacking either PAR1 or PAR2. Also, parallel to the myelin protective effects we observe here with genetic or pharmacologic targeting of PAR2, we observed similar myelin protective effects by targeting of PAR1 (Burda et al., 2013). Whether PAR1 or PAR2 will serve as a more amenable target to foster myelination and myelin repair, and whether targeting these receptors in unison would promote additive pro-myelinating effects, awaits additional study.

Summary

These studies identify PAR2 as a central biological signaling node that is important in controlling myelination in the developing and adult spinal cord. In the proposed model, PAR2 can be blocked during myelin development or after injury in adulthood to foster myelin production. Results link PAR2 to myelinogenesis through adenylate cyclase and ERK1/2 signaling, identifying a new and important role for PAR2 as an integral regulator of myelin dynamics. These studies also provide a new mechanistic link between the actions of extracellular proteases, myelination, and cellular repair. Findings are relevant to myelin generation in protection, repair and regeneration in SCI and neurological diseases, and strongly implicate PAR2 as a possible therapeutic target for myelin regeneration and intervention in CNS disease pathology.

Main Points.

Genetic deletion of PAR2 fosters myelin production developmentally and myelin regeneration in the adult. The promyelinating effects of blocking PAR2 are associated with increases in cAMP, and can be blocked in vitro by inhibiting adenylate cyclase.

Acknowledgments

Studies were supported by the National Institutes of Health R01NS052741, RG4958 from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, an Accelerated Regenerative Medicine Award from the Mayo Clinic Center for Regenerative Medicine (IAS), the Australian Research Council CE140100011 and National Health and Medical Research Council 1084083, 1047759, 1027369 (DPF).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: DPF is an inventor on PAR2 small molecules owned by University of Queensland. The authors declare no other competing financial interests.

References

- Arai T, Miklossy J, Klegeris A, Guo JP, McGeer PL. Thrombin and prothrombin are expressed by neurons and glial cells and accumulate in neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer disease brain. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology. 2006;65:19–25. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000196133.74087.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry GD, Suen JY, Le GT, Cotterell A, Reid RC, Fairlie DP. Novel agonists and antagonists for human protease activated receptor 2. J Med Chem. 2010;53:7428–7440. doi: 10.1021/jm100984y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burda JE, Radulovic M, Yoon H, Scarisbrick IA. Critical role for PAR1 in kallikrein 6-mediated oligodendrogliopathy. Glia. 2013;61:1456–1470. doi: 10.1002/glia.22534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahoy JD, Emery B, Kaushal A, Foo LC, Zamanian JL, Christopherson KS, Xing Y, Lubischer JL, Krieg PA, Krupenko SA, Thompson WJ, Barres BA. A transcriptome database for astrocytes, neurons, and oligodendrocytes: a new resource for understanding brain development and function. J Neurosci. 2008;28:264–278. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4178-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Friedman B, Whitney MA, Winkle JA, Lei IF, Olson ES, Cheng Q, Pereira B, Zhao L, Tsien RY, Lyden PD. Thrombin activity associated with neuronal damage during acute focal ischemia. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2012;32:7622–7631. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0369-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citron BA, Smirnova IV, Arnold PM, Festoff BW. Upregulation of neurotoxic serine proteases, prothrombin, and protease- activated receptor 1 early after spinal cord injury. Journal of neurotrauma. 2000;17:1191–1203. doi: 10.1089/neu.2000.17.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czopka T, von Holst A, ffrench-Constant C. Faissner A. Regulatory mechanisms that mediate tenascin C-dependent inhibition of oligodendrocyte precursor differentiation. J Neurosci. 2010;30:12310–12322. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4957-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Andrea MR, Derian CK, Leturcq D, Baker SM, Brunmark A, Ling P, Darrow AL, Santulli RJ, Brass LF, Andrade-Gordon P. Characterization of protease-activated receptor-2 immunoreactivity in normal human tissues. J Histochem Cytochem. 1998;46:157–164. doi: 10.1177/002215549804600204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulmer CG, VonDran MW, Stillman AA, Huang Y, Hempstead BL, Dreyfus CF. Astrocyte-derived BDNF supports myelin protein synthesis after cuprizone-induced demyelination. J Neurosci. 2014;34:8186–8196. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4267-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funfschilling U, Supplie LM, Mahad D, Boretius S, Saab AS, Edgar J, Brinkmann BG, Kassmann CM, Tzvetanova ID, Mobius W, Diaz F, Meijer D, Suter U, Hamprecht B, Sereda MW, Moraes CT, Frahm J, Goebbels S, Nave KA. Glycolytic oligodendrocytes maintain myelin and long-term axonal integrity. Nature. 2012;485:517–521. doi: 10.1038/nature11007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furusho M, Dupree JL, Nave KA, Bansal R. Fibroblast growth factor receptor signaling in oligodendrocytes regulates myelin sheath thickness. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2012;32:6631–6641. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6005-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyffe-Maricich SL, Schott A, Karl M, Krasno J, Miller RH. Signaling through ERK1/2 controls myelin thickness during myelin repair in the adult central nervous system. J Neurosci. 2013;33:18402–18408. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2381-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingrich MB, Traynelis SF. Serine proteases and brain damage - is there a link? Trends in Neuroscience. 2000;23:399–407. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01617-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guardiola-Diaz HM, Ishii A, Bansal R. Erk1/2 MAPK and mTOR signaling sequentially regulates progression through distinct stages of oligodendrocyte differentiation. Glia. 2012;60:476–486. doi: 10.1002/glia.22281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington EP, Zhao C, Fancy SP, Kaing S, Franklin RJ, Rowitch DH. Oligodendrocyte PTEN is required for myelin and axonal integrity, not remyelination. Ann Neurol. 2010;68:703–716. doi: 10.1002/ana.22090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebb AL, Bhan V, Wishart AD, Moore CS, Robertson GS. Human kallikrein 6 cerebrospinal levels are elevated in multiple sclerosis. Curr Drug Discov Technol. 2011;7:137–140. doi: 10.2174/157016310793180611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine KA, Blakemore WF. Remyelination protects axons from demyelination-associated axon degeneration. Brain. 2008;131:1464–1477. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii A, Fyffe-Maricich SL, Furusho M, Miller RH, Bansal R. ERK1/ERK2 MAPK signaling is required to increase myelin thickness independent of oligodendrocyte differentiation and initiation of myelination. J Neurosci. 2012;32:8855–8864. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0137-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii A, Furusho M, Bansal R. Sustained activation of ERK1/2 MAPK in oligodendrocytes and schwann cells enhances myelin growth and stimulates oligodendrocyte progenitor expansion. J Neurosci. 2013;33:175–186. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4403-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Y, Pang PT, Feng L, Lu B. Cyclic AMP controls BDNF-induced TrkB phosphorylation and dendritic spine formation in mature hippocampal neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:164–172. doi: 10.1038/nn1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi M, Fehlings M. Development and characterization of a novel, graded model of clip compressive spinal cord injury in the mouse: Part 1. Clip design, behavioral outcomes, and histopathology. J Neurotrauma. 2002;19:175–190. doi: 10.1089/08977150252806947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junge CE, Lee CJ, Hubbard KB, Zhang Z, Olson JJ, Hepler JR, Brat DJ, Traynelis SF. Protease-activated receptor-1 in human brain: localization and functional expression in astrocytes. Exp Neurol. 2004;188:94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer D, Gottle P, Hartung HP, Kury P. Pushing Forward: Remyelination as the New Frontier in CNS Diseases. Trends Neurosci. 2016;39:246–263. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlmann T, Miron V, Cui Q, Wegner C, Antel J, Bruck W. Differentiation block of oligodendroglial progenitor cells as a cause for remyelination failure in chronic multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2008;131:1749–1758. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligon KL, Fancy SP, Franklin RJ, Rowitch DH. Olig gene function in CNS development and disease. Glia. 2006;54:1–10. doi: 10.1002/glia.20273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohman RJ, Cotterell AJ, Barry GD, Liu L, Suen JY, Vesey DA, Fairlie DP. An antagonist of human protease activated receptor-2 attenuates PAR2 signaling, macrophage activation, mast cell degranulation, and collagen-induced arthritis in rats. Faseb J. 2012a;26:2877–2887. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-201004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohman RJ, Cotterell AJ, Suen J, Liu L, Do AT, Vesey DA, Fairlie DP. Antagonism of protease-activated receptor 2 protects against experimental colitis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012b;340:256–265. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.187062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noorbakhsh F, Vergnolle N, McArthur JC, Silva C, Vodjgani M, Andrade-Gordon P, Hollenberg MD, Power C. Proteinase-activated receptor-2 induction by neuroinflammation prevents neuronal death during HIV infection. J Immunol. 2005;174:7320–7329. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.7320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noorbakhsh F, Tsutsui S, Vergnolle N, Boven LA, Shariat N, Vodjgani M, Warren KG, Andrade-Gordon P, Hollenberg MD, Power C. Proteinase-activated receptor 2 modulates neuroinflammation in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis. J Exp Med. 2006;203:425–435. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrikios P, Stadelmann C, Kutzelnigg A, Rauschka H, Schmidbauer M, Laursen H, Sorensen PS, Bruck W, Lucchinetti C, Lassmann H. Remyelination is extensive in a subset of multiple sclerosis patients. Brain. 2006;129:3165–3172. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radulovic M, Yoon H, Larson N, Wu J, Linbo R, Burda JE, Diamandis EP, Blaber SI, Blaber M, Fehlings MG, Scarisbrick IA. Kallikrein cascades in traumatic spinal cord injury: in vitro evidence for roles in axonopathy and neuron degeneration. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology. 2013;72:1072–1089. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0000000000000007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radulovic M, Yoon H, Wu J, Mustafa K, Fehlings MG, Scarisbrick IA. Genetic targeting of protease activated receptor 2 reduces inflammatory astrogliosis and improves recovery of function after spinal cord injury. Neurobiol Dis. 2015;83:75–89. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radulovic M, Yoon H, Wu J, Mustafa K, Scarisbrick IA. Targeting the thrombin receptor modulates inflammation and astrogliosis to improve recovery after spinal cord injury. Neurobiol Dis. 2016;93:226–242. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2016.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raible DW, McMorris FA. Induction of oligodendrocyte differentiation by activators of adenylate cyclase. J Neurosci Res. 1990;27:43–46. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490270107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarisbrick IA, Towner MD, Isackson PJ. Nervous system-specific expression of a novel serine protease: regulation in the adult rat spinal cord by excitotoxic injury. J Neurosci. 1997;17:8156–8168. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-21-08156.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarisbrick IA, Asakura K, Blaber S, Blaber M, Isackson PJ, Beito T, Rodriguez M, Windebank AJ. Preferential expression of myelencephalon specific protease by oligodendrocytes of the adult rat spinal cord white matter. Glia. 2000;30:219–230. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(200005)30:3<219::aid-glia2>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarisbrick IA, Isackson PJ, Ciric B, Windebank AJ, Rodriguez M. MSP, a trypsin-like serine protease, is abundantly expressed in the human nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 2001;431:347–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarisbrick IA, Blaber SI, Lucchinetti CF, Genain CP, Blaber M, Rodriguez M. Activity of a newly identified serine protease in CNS demyelination. Brain. 2002;125:1283–1296. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarisbrick IA, Blaber SI, Tingling JT, Rodriguez M, Blaber M, Christophi GP. Potential scope of action of tissue kallikreins in CNS immune-mediated disease. J Neuroimmunology. 2006a;178:167–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarisbrick IA, Sabharwal P, Cruz H, Larsen N, Vandell A, Blaber SI, Ameenuddin S, Papke LM, Fehlings MG, Reeves RK, Blaber M, Windebank AJ, Rodriguez M. Dynamic role of kallikrein 6 in traumatic spinal cord injury. Eur J Neuroscience. 2006b;24:1457–1469. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarisbrick IA, Linbo R, Vandell AG, Keegan M, Blaber SI, Blaber M, Sneve D, Lucchinetti CF, Rodriguez M, Diamandis EP. Kallikreins are associated with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis and promote neurodegeneration. Biol Chem. 2008;389:739–745. doi: 10.1515/BC.2008.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutzer SE, Angel TE, Liu T, Schepmoes AA, Xie F, Bergquist J, Vecsei L, Zadori D, Camp DG, 2nd, Holland BK, Smith RD, Coyle PK. Gray matter is targeted in first-attack multiple sclerosis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66117. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon K, Hennen S, Merten N, Blattermann S, Gillard M, Kostenis E, Gomeza J. The Orphan G Protein-coupled Receptor GPR17 Negatively Regulates Oligodendrocyte Differentiation via Galphai/o and Its Downstream Effector Molecules. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:705–718. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.683953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh V, van Pelt ED, Stoop MP, Stingl C, Ketelslegers IA, Neuteboom RF, Catsman-Berrevoets CE, Luider TM, Hintzen RQ. Gray matter-related proteins are associated with childhood-onset multiple sclerosis. Neurology(R) neuroimmunology & neuroinflammation. 2015;2:e155. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KJ, Blakemore WF, McDonald WI. Central remyelination restores secure conduction. Nature. 1979;280:395–396. doi: 10.1038/280395a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sriwai W, Mahavadi S, Al-Shboul O, Grider JR, Murthy KS. Distinctive G Protein-Dependent Signaling by Protease-Activated Receptor 2 (PAR2) in Smooth Muscle: Feedback Inhibition of RhoA by cAMP-Independent PKA. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66743. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striggow F, Riek M, Breder J, Henrich-Noack P, Reymann KG, Reiser G. The protease thrombin is an endogenous mediator of hippocampal neuroprotection against ischemia at low concentrations but causes degeneration at high concentrations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:2264–2269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040552897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suen JY, Cotterell A, Lohman RJ, Lim J, Han A, Yau MK, Liu L, Cooper MA, Vesey DA, Fairlie DP. Pathway-selective antagonism of proteinase activated receptor 2. British journal of pharmacology. 2014;171:4112–4124. doi: 10.1111/bph.12757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandell AG, Larson N, Laxmikanthan G, Panos M, Blaber SI, Blaber M, Scarisbrick IA. Protease Activated Receptor Dependent and Independent Signaling by Kallikreins 1 and 6 in CNS Neuron and Astroglial Cell Lines. Journal of neurochemistry. 2008;107:855–870. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05658.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang HJ, Vainshtein A, Maik-Rachline G, Peles E. G protein-coupled receptor 37 is a negative regulator of oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination. Nature communications. 2016;7:10884. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon H, Radulovic M, Wu J, Blaber SI, Blaber M, Fehlings MG, Scarisbrick IA. Kallikrein 6 signals through PAR1 and PAR2 to promote neuron injury and exacerbate glutamate neurotoxicity. Journal of neurochemistry. 2013;127:283–298. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon H, Radulovic M, Drucker KL, Wu J, Scarisbrick IA. The thrombin receptor is a critical extracellular switch controlling myelination. Glia. 2015;63:846–859. doi: 10.1002/glia.22788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu WR, Fehlings MG. Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis and inflammation are key features of acute human spinal cord injury: implications for translational, clinical application. Acta neuropathologica. 2011;122:747–761. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0882-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]