Delirium is a devastating condition for a patient with advanced cancer. Early diagnosis in the emergency department should improve management of this life‐threatening condition. This article presents results of a prospective study of patients with advanced cancer who presented to the emergency department at MD Anderson Cancer Center and were assessed for delirium.

Keywords: Delirium, Cancer, Emergency, Survival, Advance directives

Abstract

Background.

To improve the management of advanced cancer patients with delirium in an emergency department (ED) setting, we compared outcomes between patients with delirium positively diagnosed by both the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) and Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale (MDAS), or group A (n = 22); by the MDAS only, or group B (n = 22); and by neither CAM nor MDAS, or group C (n = 199).

Materials and Methods.

In an oncologic ED, we assessed 243 randomly selected advanced cancer patients for delirium using the CAM and the MDAS and for presence of advance directives. Outcomes extracted from patients’ medical records included hospital and intensive care unit admission rate and overall survival (OS).

Results.

Hospitalization rates were 82%, 77%, and 49% for groups A, B, and C, respectively (p = .0013). Intensive care unit rates were 18%, 14%, and 2% for groups A, B, and C, respectively (p = .0004). Percentages with advance directives were 52%, 27%, and 43% for groups A, B, and C, respectively (p = .2247). Median OS was 1.23 months (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.46–3.55) for group A, 4.70 months (95% CI 0.89–7.85) for group B, and 10.45 months (95% CI 7.46–14.82) for group C. Overall survival did not differ significantly between groups A and B (p = .6392), but OS in group C exceeded those of the other groups (p < .0001 each).

Conclusion.

Delirium assessed by either CAM or MDAS was associated with worse survival and more hospitalization in patients with advanced cancer in an oncologic ED. Many advanced cancer patients with delirium in ED lack advance directives. Delirium should be assessed regularly and should trigger discussion of goals of care and advance directives.

Implications for Practice.

Delirium is a devastating condition among advanced cancer patients. Early diagnosis in the emergency department (ED) should improve management of this life‐threatening condition. However, delirium is frequently missed by ED clinicians, and the outcome of patients with delirium is unknown. This study finds that delirium assessed by the Confusion Assessment Method or the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale is associated with poor survival and more hospitalization among advanced cancer patients visiting the ED of a major cancer center, many of whom lack advance directives. Therefore, delirium in ED patients with cancer should trigger discussion about advance directives.

Introduction

Delirium in patients with cancer is associated with an increased risk of mortality and morbidity, functional decline, falls, and increased risk of institutionalization after discharge from the hospital [1], [2], [3]. Most studies of delirium in cancer patients are limited to patients in palliative care services [4], [5], [6] and intensive care units (ICUs) [7]. In ICUs, delirium is associated with increased mortality, prolonged mechanical ventilation, prolonged hospital stays, and cognitive impairment in patients discharged alive [7]. In cancer patients receiving palliative care, delirium is associated with shorter survival and high distress in patients, families, and clinicians [2], and refractory agitated delirium is a major reason for palliative sedation [8], [9]. Therefore, delirium screening is an important component of tools developed to estimate survival in patients receiving palliative care, such as the Palliative Prognostic Index and the Palliative Prognostic Score [10], [11], [12]. The addition of delirium to the latter tool significantly improved its accuracy [12].

A diagnosis of delirium in a hospitalized patient with advanced cancer is an important reason to discuss goals of care, advance care planning, and resuscitation preferences with the patient's surrogate to prevent unnecessary and costly interventions [13], [14]. These discussions should take place in the outpatient setting and prior to the onset of delirium and an emergency department (ED) visit [3], [14], [15]. Mack et al. [14] found that patients who engage in such discussion are less likely to receive aggressive care at the end of life. In a study about bereaved family members of patients who died of advanced lung or colorectal cancer, most family members perceived admission to hospice for more than 3 days, avoidance of ICU admission within 30 days of death, or death outside the hospital as better end‐of‐life care [16].

In the ED setting [17], [18], a diagnosis of delirium in elderly patients in ED was associated with an increased 6‐month mortality rate. Our group found that the presence of altered mental status, although not delirium specifically, in an oncologic ED was independently associated with increased ICU admission and hospital mortality [19]. Previously, we determined the frequency of delirium in advanced cancer patients visiting the ED at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center [20]. Our findings were of interest to many clinicians, including Vincent et al. [21], who expressed the need to learn more about events following the ED visit, as well as the navigation of the complex decision‐making process of ICU admission, prognosis, and the role of advance directives [21]. In the present manuscript, we address this need by reporting our outcome data from the same cohort. To the best of our knowledge, the outcomes of delirium in cancer patients in the ED setting are unknown. We evaluated advance directive presence, overall survival (OS), and hospitalization and ICU admission in patients with delirium diagnosed by both the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) and Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale (MDAS), or group A (n = 22); those with delirium diagnosed by the MDAS only, or group B (n = 22); and those without a delirium diagnosis by either CAM or MDAS, or group C (n = 199).

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Patients

We performed a prospective cross‐sectional observational study of patients with advanced cancer who presented in the ED of MD Anderson Cancer Center. Study enrollment occurred from March 11, 2013 through July 21, 2014. Our primary aim was to determine the frequency of delirium in these patients; as reported previously, we found delirium in 9% (n = 22) using CAM and in 18% (n = 44) using MDAS, the latter of which included all the patients diagnosed by CAM [20]. Our secondary aim was to compare hospital admission rate, ICU admission rate, presence of advance directives, hospital mortality, and OS between the patients with and without delirium. The study was approved by the MD Anderson Institutional Review Board.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were described previously [20]. Briefly, we included adults with advanced cancer who had been in the ED for less than 12 hours, and who could provide consent or had a legally authorized representative able to provide consent, and we excluded patients with unstable conditions in need of emergent medical attention, patients with a history of dementia, and patients with communication barriers. Of 1,832 patients screened for this study, 624 were eligible, and 243 were enrolled. The main reasons for ineligibility were that the cancer was not advanced, the patient was in the ED for >12 hours, the presence of a language barrier, or that the patient was already admitted to the hospital and waiting for bed.

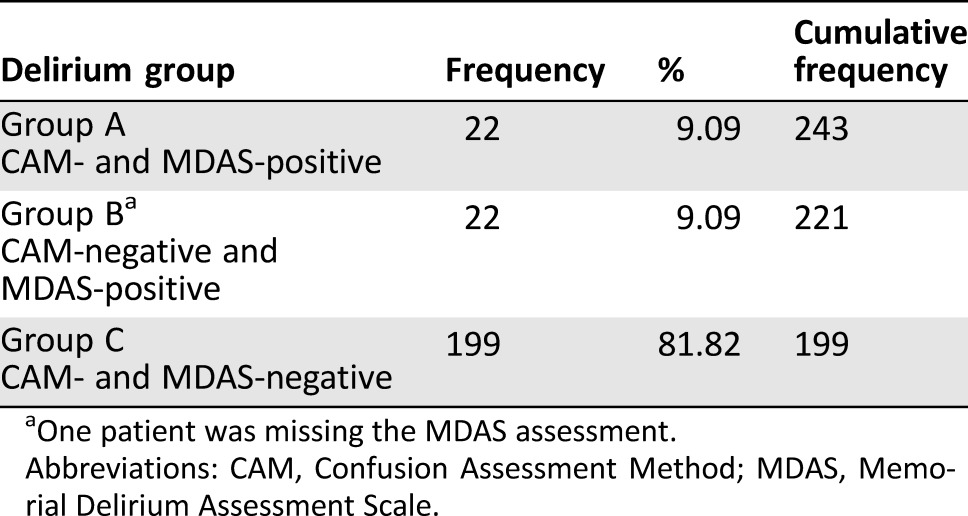

As previously described [20], we used the CAM instrument, a 4‐item questionnaire that produces results expressed as a dichotomous variable, to diagnose delirium, and we used the MDAS instrument, a 10‐item questionnaire, to measure delirium severity. Although our palliative care team uses MDAS regularly to assess for delirium in both an outpatient and inpatient setting, we did not use it primarily for the assessment of delirium in our study because it is not validated in the ED setting. However, because we found that all patients who were CAM‐positive were also MDAS‐positive, and that an additional 22 patients were MDAS‐positive but CAM‐negative, we separately assessed the outcomes of the patients diagnosed with delirium by MDAS but not CAM. Therefore, we compared the outcome of delirium between three groups: group A was patients with delirium per both CAM and MDAS, group B was patients with delirium per MDAS only, and group C was patients without delirium per both instruments (Table 1).

Table 1. Delirium assessment by CAM and MDAS.

One patient was missing the MDAS assessment.

Abbreviations: CAM, Confusion Assessment Method; MDAS, Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale.

The CAM has been validated in the ED, can differentiate delirium from other cognitive conditions, and usually takes less than 5 minutes to complete. The CAM has a sensitivity and specificity of over 90% but has a false‐positive rate of 10%. The MDAS has been validated in hospitalized cancer patients and in the palliative care setting but not in the ED. The scale has good validity and inter‐rater reliability. After a short training period, one can administer the test easily and quickly [22].

Setting and Patient Selection

MD Anderson is a large comprehensive cancer center with 26,000 ED visits per year, and over 95% of patients seen in the MD Anderson ED have cancer. In the ED, patients are seen first in the triage area before they are assigned to a room. Computer‐generated random numbers were used to determine which rooms the research assistant (RA) approached to recruit participants and in what order.

Study Protocol

After rooms to be approached were randomly chosen, eligibility was determined and patients recruited as described previously [20]. After patients were enrolled, they were assessed for delirium by the RA using CAM and MDAS. The RA then reviewed medications used by the patient over the last 24 hours, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) [23] performance status through a face‐to‐face interview with the patient and legally authorized representative (if present). The RA obtained demographic variables and clinical variables of triage acuity from medical records. The RA also asked whether the patient had advance directives, out‐of‐hospital Do‐Not‐Resuscitate (DNR) orders, or prior enrollment in hospice. We obtained rate of hospital admission related to the ED visit, rate of ICU admission related to the ED visit, hospital mortality, and median OS by reviewing the medical records of all patients enrolled in the study.

Statistical Analysis

We used logistic regression to test the association between delirium group and each of the two binary outcome variables: ED‐related hospitalizations and ED‐related ICU admissions. Odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding confidence intervals (CIs) are presented along with Nagelkerke's r2 for assessing model fit. We used the Kaplan‐Meier method to estimate OS, and we used the log‐rank test to compare survival between patients grouped by delirium status and other variables. Survival was calculated from the date of ED admission until death. Patients who did not die during follow‐up were censored at the date of last known vital status. We conducted post hoc tests with Šidák correction for pairwise group comparisons. We also analyzed the association of the presence of advance directives with hospitalization and ICU admission using Fisher's exact test. A multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to investigate the effects of delirium group while controlling for ECOG status. All p values less than .05 were considered statistically significant. All data analyses were conducted using SAS for Windows (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, https://www.sas.com/en_us/home.html).

Results

Two hundred forty‐three patients were enrolled, and all were assessed for delirium using both CAM and MDAS except for one participant, who was missing the MDAS assessment. Twenty‐two patients (9%) were diagnosed with delirium by both CAM and MDAS (group A). No patients were both CAM‐positive and MDAS‐negative. The MDAS alone diagnosed delirium in 22 other patients (9%; group B). The patient missing the MDAS assessment did not have delirium per CAM, and the remaining 199 patients (group C) did not have delirium according to both CAM and MDAS (Table 1).

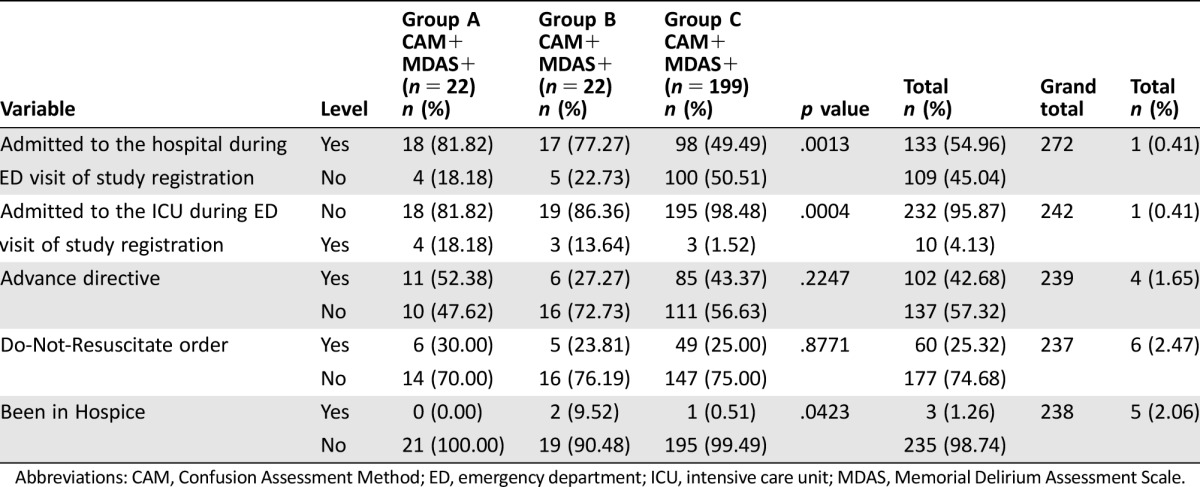

Table 2 shows the presence of advance directives and out‐of‐hospital DNR orders and whether the patient had been enrolled in hospice before. There were no significant differences between delirium groups with respect to advance directives or DNR orders. Although the delirium groups significantly differed in whether patients had been in hospice, only three patients in all the groups had a history of hospice care.

Table 2. Association between delirium group and advance directives, previous hospice admission, and hospital and ICU admission by Fisher exact test.

Abbreviations: CAM, Confusion Assessment Method; ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit; MDAS, Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale.

Delirium diagnosis was significantly associated with admission to the hospital and admission to the ICU (Table 2). A total of 133 patients were admitted to the hospital during the ED visit (chi‐square(2) = 11.888; p = .0026), although the strength of the association was relatively weak (Nagelkerke's r2 = .0762). Based on a single‐effect model, the odds of hospitalization for group A were 4.6 times those for group C (OR 4.59, 95% CI 1.50–14.05; p = .0076), and for group B patients, the odds of hospitalization were 3.5 times those of group C (OR 3.47, 95% CI 1.23–9.77; p = .0185). Group C (the no‐delirium group) showed lower odds of hospitalization than did the other two groups. In post hoc tests, a pairwise comparison of group A and group B showed no statistically significant difference in the odds of hospitalization (chi‐square(1) = 0.1392; p = .7091).

Overall, the predicted probability of hospitalization was 0.55 (95% CI 0.49–0.61). The predicted probability of hospitalization was 0.82 (95% CI 0.60–0.93) for group A, 0.77 (95% CI 0.56–0.90) for group B (MDAS only), and 0.49 (95% CI 0.43–0.56) for group C (no delirium).

Having advance directives was not associated with hospitalization. Of those hospitalized, 53.92% (n = 55/102) had advance directives and 55.47% (n = 76/137) did not (Fisher's exact test p = .90). Data were missing for four patients. Among those hospitalized, 5.45% (n = 3/55) of patients with advance directives and 7.89% (n = 6/76) of patients without advance directives were admitted to the ICU (Fisher's exact test p = .73). Also, we did not detect a statistically significant association between DNR status and hospitalization (Fisher's exact test p = .55), nor was there evidence of an association between DNR status and ICU admission among those who were hospitalized (Fisher's exact test p = .70).

In a Cox proportional hazards regression model, delirium group remained a statistically significant predictor of OS (Wald chi‐square(2) = 10.93, p = .0042) while controlling for baseline ECOG status. The risk of death relative to the CAM‐negative/MDAS‐negative group was higher for the CAM‐positive/MDAS‐positive group (hazard ratio [HR] = 2.45; 95% CI 1.40–4.29; p = .0018) and for the CAM‐negative/MDAS‐positive group (HR = 1.67; 95% CI 0.93–2.98; p = .0856). The ECOG status was statistically significant in the model (Wald chi‐square(4) = 14.80, p = .0051).

Ten patients in the study population were admitted to the ICU during the ED visit. Delirium (groups A and B) was significantly associated with ICU admission (chi‐square(2) = 12.639; p = .0018), although the strength of the association was relatively weak (Nagelkerke's r2 at .1907). Based on the single‐effect model, the odds of ICU admission for group A were greater than those of group C (no delirium; OR 14.45, 95% CI 3.00–69.63; p = .0009). Group B also had greater odds of ICU admission than did group C (OR 10.26, 95% CI 1.94–54.42; p = .0062). The point estimates are imprecise, as reflected by the wide confidence intervals. Patients without delirium (group C) showed lower odds of ICU admission than did the other two groups. In post hoc tests, a pairwise comparison of group A and group B showed no statistically significant difference in odds of ICU admission (chi‐square(1) = 0.1689; p = .6811).

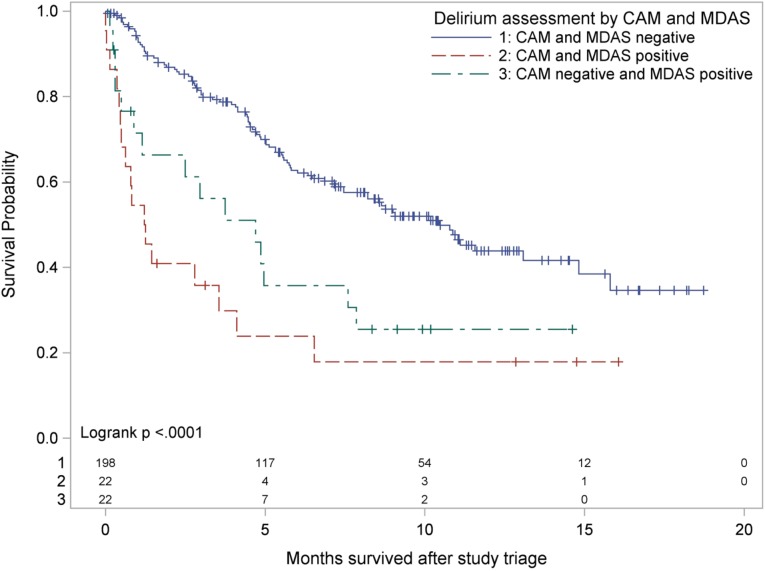

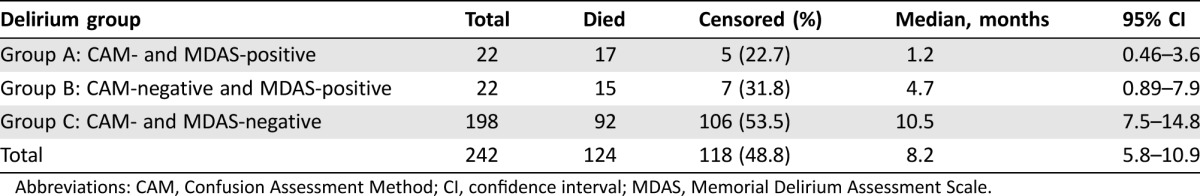

Among the 242 patients who were assessed by both CAM and MDAS, 124 died during follow‐up. For the 118 participants who were alive at the end of follow‐up, the median follow‐up from study triage was 9.13 months (range 0.07–18.7 months). For the entire study cohort, the median OS from study triage was 8.21 months (95% CI 5.82–10.87 months; Table 3). Overall survival significantly differed between the three delirium groups (log‐rank chi‐square(2) = 28.71; p < .0001; Fig. 1). The Šidák multiple‐comparison results indicated no statistically significant difference in OS between group A and group B (p = .6392), but the OS of group C was significantly longer than that of each of the other two groups (p < .0001 for each).

Table 3. Overall survival by delirium group.

Abbreviations: CAM, Confusion Assessment Method; CI, confidence interval; MDAS, Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale.

Figure 1.

Kaplan‐Meier survival by delirium group with number at risk.

Abbreviations: CAM, Confusion Assessment Method; MDAS: Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale.

Discussion

In this prospective study of patients with advanced cancer who presented to the ED at MD Anderson and were assessed for delirium using two different tools (CAM and MDAS), we found that patients with delirium had higher rates of hospitalization and ICU admission and worse OS, indicating that delirium in this setting is associated with worse outcomes. Therefore, delirium should be regularly assessed in advanced cancer patients in the ED setting so that this life‐threatening condition can be diagnosed and managed early.

Patients who were CAM‐negative but MDAS‐positive had similar outcomes to those of patients who were CAM‐ and MDAS‐positive, suggesting a higher sensitivity of MDAS in assessing for delirium in the ED. However, MDAS is not validated in the ED setting, and it is significantly longer than the CAM. Further research is needed to compare the two tools in the ED setting, probably in addition to evaluation of all patients with suspected delirium by a psychiatrist, as suggested by Lawlor [24]. A short sensitive tool is needed to detect delirium in the ED.

Most of the patients diagnosed with delirium per MDAS or CAM were admitted to the hospital, and some of the CAM‐ and MDAS‐positive patients were admitted to the ICU; these hospital and ICU admission rates were significantly greater than those of patients without delirium according to both tools. In all cases, delirium should be promptly managed, safety should be maintained at all times, and the culprit causes should be identified and corrected if possible. Medications in particular are associated with more delirium reversal [25], and symptom management, including opioid switching, is associated with resolution of delirium [26].

Overall, more than half of the patients did not have advance directives or out‐of‐hospital DNR orders, and there was no difference in these factors between patients with and without delirium (Table 1). Given the lack of advance directives and DNR orders, along with the poor survival of patients with delirium in the ED, it might be prudent to start discussing goals of care and DNR orders with the legally authorized representatives of patients with delirium in the ED if these directives have not been established previously. End‐of‐life discussions are better done by oncologists in the outpatient setting than in the ED; however, these discussions are usually initiated in the last 33 days of life, in the inpatient hospital setting, and by providers other than oncologists [27]. Mack et al. [14] found that early discussion of goals of care is associated with less aggressive care, including fewer ICU and hospital deaths and more hospice admissions [14]; notably, only a few patients in the present study had been in hospice previously. Wright et al. [16] found an association of aggressive end‐of‐life care with poor quality of life in advanced cancer patients and with complicated bereavement in their caregivers. Because of the relatively high prevalence of delirium among advanced cancer patients in the ED [20], and the high mortality we observed in this study, universal screening for delirium is justified.

We did not find statistically significant differences between patients who had advance directives or out of hospital DNR and those who did not regarding the rate of hospitalization or ICU admission. However, whether these documents (advance directives and DNR) were reviewed by ED physicians and played a role in the decision‐making process of hospitalization is not clear. Although ED physicians value these documents, they have difficulty finding and using them [28]. Moreover, the total number of patients admitted to the ICU was small, limiting further analysis. More research is needed to determine the impact of advance directives and DNR discussion in the ED on the rate and length of hospitalization, ICU admission, and hospice referral.

In a survey about barriers to end‐of‐life discussion by You et al. [29], respondents identified among the main barriers a lack of understanding of the limitations of life‐sustaining measures, difficulty in accepting a poor prognosis, and disagreement between family members. Because patients with delirium are unable to engage in meaningful discussion about goals of care and DNR orders, such interaction is carried out with their surrogates and can be time‐consuming. Having an interdisciplinary team trained in communication and in addressing these issues will significantly improve the care provided to these patients and their family members. Further research should evaluate the impact of such a team on the quality of end‐of‐life care.

We found that delirious patients had shorter survival than patients without delirium. This survival could be even shorter had we included unstable patients with life‐threatening conditions. These findings are similar to those in elderly patients with and without delirium in the ED [30]. Interestingly, we found that the median survival of advanced cancer patients with delirium in the ED was only 1.2 months for patients who were CAM‐positive, and these survival outcomes are worse than those of elderly patients with delirium but without cancer in the ED, of whom only 6% died within 1 month in one study [17] and 31%–37% died within 6 months in other studies [17], [30], [31]. Consequently, clinicians caring for advance cancer patients with delirium in EDs should strongly consider focusing on goals of care, resuscitation preferences, and quality of life for patients and their family members.

Although poor performance status (ECOG 3 or 4) was found in over 80% of patients with delirium in this cohort [20], further analysis in this study using multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression model revealed delirium to be an independent predictor of OS, while controlling for ECOG performance status. Moreover, the addition of delirium to the palliative prognostic score (which includes performance status) significantly improved the accuracy of the score [12]. Further analysis of data is needed to clarify the role of poor performance status, delirium, and other symptoms such as dyspnea in predicting mortality in ED patients with advanced cancer.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first prospective study to show the rate of hospitalization, advance care planning, and mortality among advanced cancer patients seeking emergent medical care. Our study has some limitations. First, it is a single‐center study, and therefore, our findings need to be confirmed in a multicenter study. Second, the total number of patients was relatively small, in particular when comparing groups A and B. A larger study is needed to confirm our findings. Third, we did not adjust for comorbidities or severity of illness. Finally, we did not follow patients longitudinally to evaluate whether further interventions were done during hospitalization and whether patients were discharged to hospice or to hospital follow‐up.

Conclusion

Patients with delirium upon arrival to the ED have increased hospitalization rates, increased ICU admission rates, and shorter survival than those without delirium. In addition to reversing the cause of delirium and control of symptoms, management of cancer patients with delirium in the ED should include addressing goals of care and resuscitation preferences with the patient's legally authorized representative and the treating primary oncologist.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the patients and their family members who participated in this study. We also thank Sarah Bronson from Scientific Publications at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center for her assistance with editing the manuscript. The data in this study were presented in part at the Annual Meeting of the American Delirium Society, Baltimore, MD, June 2015. This study was funded by the MD Anderson Foundation via the Institutional Research Grants Program. MD Anderson Cancer Center is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA016672.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Ahmed F. Elsayem, Eduardo Bruera, Alan Valentine, Geri L. Wood, Sai‐Ching J. Yeung, Patricia A. Brock, Knox H. Todd

Financial support: Ahmed F. Elsayem

Administrative support: Ahmed F. Elsayem, Knox H. Todd

Collection and/or assembly of data: Ahmed F. Elsayem, Valda D. Page, Julio Silvestre, Patricia A. Brock

Data analysis and interpretation: Ahmed F. Elsayem, Carla L. Warneke

Manuscript writing: Ahmed F. Elsayem, Eduardo Bruera, Carla L. Warneke

Final approval of manuscript: Ahmed F. Elsayem, Eduardo Bruera, Alan Valentine, Carla L. Warneke, Geri L. Wood, Sai‐Ching J. Yeung, Valda D. Page, Julio Silvestre, Patricia A. Brock, Knox H. Todd

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1. Breitbart W, Alici Y. Evidence‐based treatment of delirium in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1206–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bruera E, Bush SH, Willey J et al. Impact of delirium and recall on the level of distress in patients with advanced cancer and their family caregivers. Cancer 2009;115:2004–2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carlson B. Delirium in patients with advanced cancer. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:e379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sweet L, Adamis D, Meagher DJ et al. Ethical challenges and solutions regarding delirium studies in palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;48:259–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grassi L, Caraceni A, Mitchell AJ et al. Management of delirium in palliative care: A review. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2015;17:550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. de la Cruz M, Ransing V, Yennu S et al. The frequency, characteristics, and outcomes among cancer patients with delirium admitted to an acute palliative care unit. The Oncologist 2015;20:1425–1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Salluh JI, Wang H, Schneider EB et al. Outcome of delirium in critically ill patients: Systematic review and meta‐analysis. BMJ 2015;350:h2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Beller EM, van Driel ML, McGregor L et al. Palliative pharmacological sedation for terminally ill adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;1:Cd010206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Elsayem A, Curry Iii E, Boohene J et al. Use of palliative sedation for intractable symptoms in the palliative care unit of a comprehensive cancer center. Support Care Cancer 2009;17:53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Baba M, Maeda I, Morita T et al. Survival prediction for advanced cancer patients in the real world: A comparison of the Palliative Prognostic Score, Delirium‐Palliative Prognostic Score, Palliative Prognostic Index and modified Prognosis in Palliative Care Study predictor model. Eur J Cancer 2015;51:1618–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hamano J, Yamaguchi T, Maeda I et al. Multicenter cohort study on the survival time of cancer patients dying at home or in a hospital: Does place matter? Cancer 2016;122:1453–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Scarpi E, Maltoni M, Miceli R et al. Survival prediction for terminally ill cancer patients: Revision of the palliative prognostic score with incorporation of delirium. The Oncologist 2011;16:1793–1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goldberg SL, Pecora AL, Contreras J et al. A patient‐reported outcome instrument to facilitate timing of end‐of‐life discussions among patients with advanced cancers. J Palliat Med 2016;19:1092–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mack JW, Cronin A, Keating NL et al. Associations between end‐of‐life discussion characteristics and care received near death: A prospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:4387–4395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Keating NL, Landrum MB, Rogers SO Jr et al. Physician factors associated with discussions about end‐of‐life care. Cancer 2010;116:998–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A et al. Associations between end‐of‐life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA 2008;300:1665–1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Han JH, Shintani A, Eden S et al. Delirium in the emergency department: An independent predictor of death within 6 months. Ann Emerg Med 2010;56:244–252.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rizzi MA, Torres Bonafonte OH, Alquezar A et al. Prognostic value and risk factors of delirium in emergency patients with decompensated heart failure. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2015;16:799.e1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Elsayem AF, Merriman KW, Gonzalez CE et al. Presenting symptoms in the emergency department as predictors of intensive care unit admissions and hospital mortality in a comprehensive cancer center. J Oncol Pract 2016;12:e554–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Elsayem AF, Bruera E, Valentine AD et al. Delirium frequency among advanced cancer patients presenting to an emergency department: A prospective, randomized, observational study. Cancer 2016;122:2918–2924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vincent F, Pavese I, Gligorov J et al. Patients with delirium and advanced solid cancer in the emergency department: A challenge for the emergency practitioner, oncologist, and intensivist. Cancer 2017;123:704–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fadul N, Kaur G, Zhang T et al. Evaluation of the memorial delirium assessment scale (MDAS) for the screening of delirium by means of simulated cases by palliative care health professionals. Support Care Cancer 2007;15:1271–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol 1982;5:649–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lawlor PG. Cancer patients with delirium in the emergency department: A frequent and distressing problem that calls for better assessment. Cancer 2016;122:2783–2786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lawlor PG, Gagnon B, Mancini IL et al. Occurrence, causes, and outcome of delirium in patients with advanced cancer: A prospective study. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:786–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Braiteh F, El Osta B, Palmer JL et al. Characteristics, findings, and outcomes of palliative care inpatient consultations at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med 2007;10:948–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mack JW, Cronin A, Taback N et al. End‐of‐life care discussions among patients with advanced cancer: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:204–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lakin JR, Isaacs E, Sullivan E et al. Emergency physicians' experience with advance care planning documentation in the electronic medical record: Useful, needed, and elusive. J Palliat Med 2016;19:632–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. You JJ, Downar J, Fowler RA et al. Barriers to goals of care discussions with seriously ill hospitalized patients and their families: A multicenter survey of clinicians. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:549–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kennedy M, Enander RA, Tadiri SP et al. Delirium risk prediction, healthcare use and mortality of elderly adults in the emergency department. J Amer Geriatr Soc 2014;62:462–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bradshaw LE, Goldberg SE, Lewis SA et al. Six‐month outcomes following an emergency hospital admission for older adults with co‐morbid mental health problems indicate complexity of care needs. Age Ageing 2013;42:582–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]