Abstract

The tumor suppressor p53 is a transcription factor that regulates the expression of a range of target genes in response to cellular stress. Adding to the complexity of understanding its cellular function is that in addition to the full-length protein, several p53 isoforms are produced in humans, harboring diverse expression patterns and functionalities. One isoform, Δ40p53, which lacks the first transactivation domain including the binding region for the negative regulator MDM2, was shown to be a product of alternative translation initiation. Here we report the discovery of an alternative cellular mechanism for Δ40p53 formation. We show that the 20S proteasome specifically cleaves the full-length protein (FLp53) to generate the Δ40p53 isoform. Moreover, we demonstrate that a dimer of FLp53 interacts with a Δ40p53 dimer, creating a functional hetero-tetramer. Consequently, the co-expression of both isoforms attenuates the transcriptional activity of FLp53 in a dominant negative manner. Finally, we demonstrate that following oxidative stress, at the time when the 20S proteasome becomes the major degradation machinery and FLp53 is activated, the formation of Δ40p53 is enhanced, creating a negative feedback loop that balances FLp53 activation. Overall, our results suggest that Δ40p53 can be generated by a 20S proteasome-mediated post-translational mechanism so as to control p53 function. More generally, the discovery of a specific cleavage function for the 20S proteasome may represent a more general cellular regulatory mechanism to produce proteins with distinct functional properties.

The tumor suppressor p53 is a stress response protein that functions primarily as a transcription factor regulating the levels of more than 300 genes.1 p53 activity is tightly regulated by a complex network of feedback loops that controls its cellular levels. Under basal conditions p53 levels are kept low due to continuous degradation.2 However, upon cellular insults, including oncogene activation and DNA damage, the protein is extensively post-translationally modified, and consequently stabilized and activated.3, 4, 5, 6 This in turn, leads to the induction of p53 response genes, which can induce growth arrest, apoptosis, DNA repair and differentiation,7 mediating protection from tumorigenesis.

Active p53 exists as a homo-tetramer, embracing two-folded regions: a tetramerization domain and a core DNA binding domain (reviewed in Joerger and Fersht8). These structural elements are flanked by natively unfolded domains at the N- and C-termini. The intrinsically disordered N-terminal region comprises the transactivation capacity with two transactivation domains; TADI (residues 1–40) and TADII (residues 40–61). TAD domains interact with numerous proteins including components of the transcription machinery, and the negative regulator MDM2. The latter functions both as an E3 ubiquitin ligase mediating p53 ubiquitination and subsequent 26S proteasomal degradation, and as an inhibitor of p53 transcriptional activation.9, 10 The intrinsically disordered properties of the N-terminus are also responsible for the protein susceptibility toward 20S proteasome-mediated degradation, a process that is independent on p53 ubiquitination.11

An additional mechanism that has evolved to regulate p53 function is the formation of 12 different isoforms.12, 13 These are generated by multiple mechanisms, such as alternative splicing that modify the C-terminal region of the protein (p53β, p53γ), as well as alternative promoter usage and alternative translation initiation sites that gives rise to p53 isoforms lacking the N-terminus (Δ40p53, Δ133p53, Δ160p53). In addition, multiple combinations of both N- and C-terminal variants are produced (Δ40p53β, Δ40p53γ, Δ133p53β, Δ133p53γ, Δ160p53β, Δ160p53γ).13, 14 The various p53 isoforms harbor diverse biological activities that can specifically adjust the function of the full-length p53 (FLp53) or independently regulate a variety of cellular processes.15, 16, 17, 18 Thus, in addition to the widely accepted view that ~50% of human cancers are due to p53 mutations, there are indications that the balance of p53 isoform levels may also have a role in carcinogenesis.

Here, we focus on Δ40p53, one of the p53 isoforms that is lacking the first 39 amino acids.18 This p53 variant, which is detected both in cancer cells and in healthy tissues, is generated by alternative translation initiation, a process that is conserved between mice and humans.18, 19, 20, 21 The TADI domain containing the binding site for the most critical negative regulator of p53, MDM2, is absent in this isoform. Therefore, it is not subjected to MDM2-mediated ubiquitination and 26S proteasome degradation except when it is bound to FLp53.18 The Δ40p53 isoform has been shown to impact p53 activity, when expressed together with the wild-type (WT) p53 protein, especially in imposing a dominant negative effect.18, 22, 23, 24 Altogether, it seems that Δ40p53 expression can affect cancer formation and, therefore, it is important to uncover the molecular mechanisms that coordinate its cellular levels and function.

In this study, we show an alternative cellular mechanism for Δ40p53 formation that is mediated by 20S proteasome cleavage. Specifically, by combining native mass spectrometry (MS), biochemical and cellular analyses, we demonstrate that the 20S proteasome does not degrade p53 to completion, but rather cleaves the protein precisely at position 40, generating a product homologous to Δ40p53. Additionally, we demonstrate that FLp53 and Δ40p53 form active hetero-tetramers that modulate the transcriptional activity of p53. Our data also indicate that under oxidative conditions Δ40p53 formation is enhanced, leading to attenuation of p53 transcriptional activity. Overall, our results suggest that in addition to translation initiation at position 40, Δ40p53 is generated by a post-translational event via the 20S proteasome and that this process is prominent under oxidative conditions when MDM2-mediated regulation of p53 is compromised.

Results

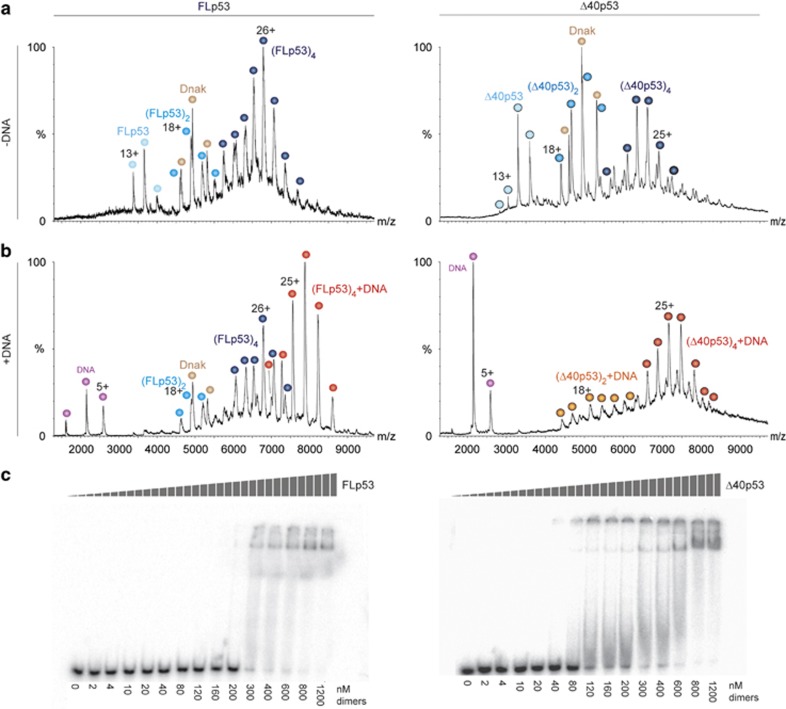

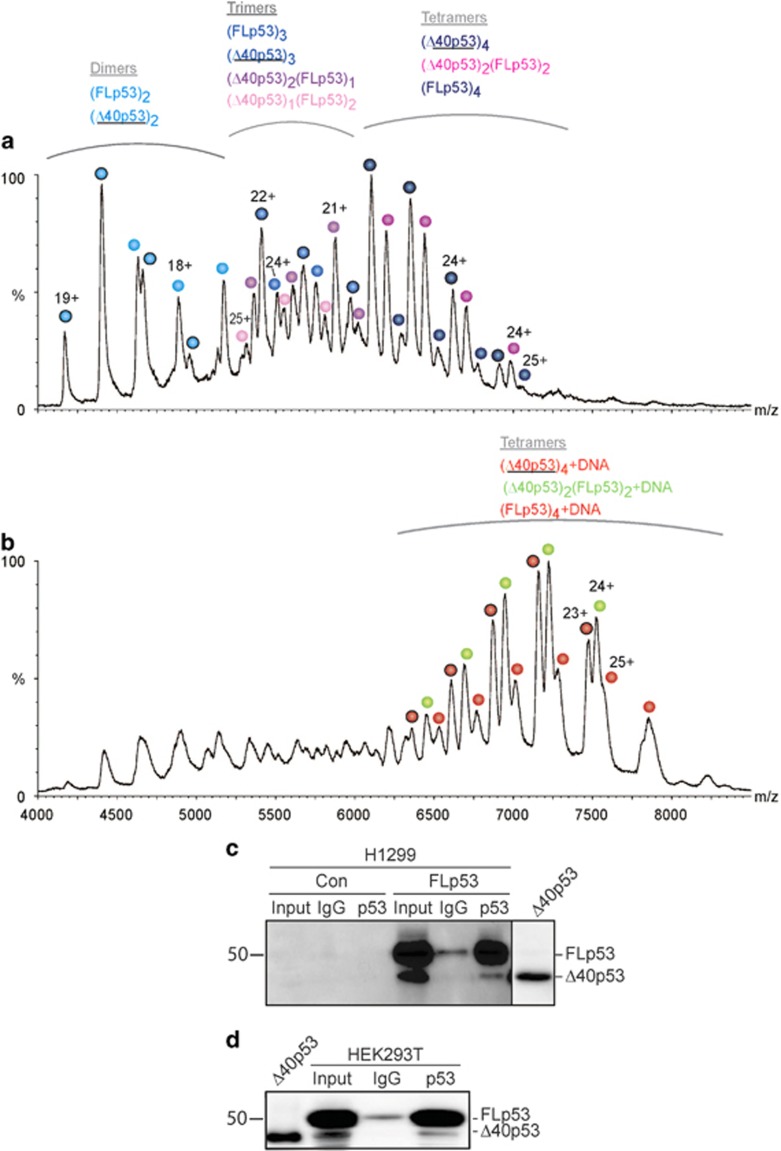

Purified FLp53 and Δ40p53 proteins form active homo-tetramers

Two alternative proteasomal degradation mechanisms, which are not mutually exclusive, have been described for p53: ubiquitin-dependent degradation by the 26S proteasome and ubiquitin-independent degradation by the 20S proteasome.9, 10, 11 Unlike the degradation by the 26S proteasome, which is an active process that is regulated by a series of ubiquitination enzymes, the ubiquitin-independent pathway is a passive process that is a result of the inherent disorder of the N-terminal region of p53. Here, in order to assess the susceptibility of human FLp53 and Δ40p53 toward 20S proteasomal cleavage, we established an in vitro system consisting of isolated 20S proteasomes and recombinant human FLp53 and Δ40p53 proteins. First, we verified the assembly state and the functionality of each of the purified p53 proteins by native MS analysis under conditions that preserve non-covalent interactions.25 Mass spectra of both proteins in the absence of DNA revealed the coexistence of monomeric, dimeric and tetrameric forms (Figure 1a). The mutual existence of dimers and tetramers is in accord with p53 assembly as a dimer of dimers.26, 27 Adding DNA to both p53 isoforms gave rise to a new dominant charge series corresponding in mass to tetrameric p53/DNA complexes (Figure 1b). Not only was the monomeric form of the protein not detected in these spectra, but the intensity of the dimeric form was significantly reduced, reflecting increased stability of the tetrameric p53/DNA complex. Moreover, in the presence of DNA, only DNA-bound Δ40p53 species were detected, unlike the spectrum of FLp53/DNA in which free dimeric and tetrameric forms are observed, suggesting higher affinity of Δ40p53 for DNA. Overall, the MS results confirmed that the purified FLp53 and Δ40p53 proteins are properly folded and able to form a tetrameric complex on DNA.

Figure 1.

Functional FLp53 and Δ40p53 were isolated from Escherichia coli. Native MS of purified FLp53 and Δ40p53 before (a) and after (b) the addition of DNA. In both cases, the p53r2 response element was used. p53 assemblies bound to DNA are indicated in warmer colors, while free p53 forms are labeled in cooler colors. Charge states circled with a black border correspond to the Δ40p53 isoform. The bacterial homolog of Hsp70, Dnak, which is known to bind p53,61 was co-purified with the p53 forms. Overall, the spectra indicate that the recombinant forms of FLp53 and Δ40p53 are capable of assembling into homo-dimers and -tetramers that bind DNA. (c) Autoradiograms of EMSA result of FLp53 and Δ40p53 bound to a p53 response element showing sequence-specific DNA binding activities

To verify our native MS data, DNA binding experiments of the two proteins were performed via electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) using radiolabeled p53 response element DNA. The binding affinities of both proteins are in the range of 300–600 nM, based on the appearance of p53–DNA complexes as a function of protein concentration (Figure 1c). The shifted complex of Δ40p53/DNA appears at a lower protein concentration than that of FLp53, indicating a higher binding affinity. In agreement with Figure 1b, this observation suggests that the absence of the negatively charged N-terminus in Δ40p53 leads to an enhanced interaction with the negatively charged DNA compared to FLp53. This finding agrees with a previous study indicating that N-terminal masking by monoclonal antibodies stabilizes p53–DNA interactions.28

Cleavage of FLp53 by the 20S proteasome generates a protein homologous to Δ40p53

To examine the susceptibility of FLp53 and Δ40p53 toward 20S proteasomal proteolysis, we performed degradation assays in the absence (Figure 2a) and presence (Figure 2b) of DNA. The results indicated that both forms of p53 are degraded by the 20S proteasome (Figures 2a–c); however, FLp53 is more susceptible to proteolysis, in comparison to Δ40p53. In addition, while DNA had no effect on FLp53 degradation, Δ40p53 is significantly less degraded following DNA addition. Notably, p53 degradation was not observed in the presence of purified 26S proteasomes, which is consistent with previous findings29 (Supplementary Figure 1). Overall, these results support the view that the unstructured N-terminal domain of FLp53 is responsible for susceptibility toward 20S proteasomal degradation.11 Additionally, they suggest that by binding to DNA (Figure 1), Δ40p53 gains structural stability,30 which in turn reduces its susceptibility toward 20S proteasome cleavage.

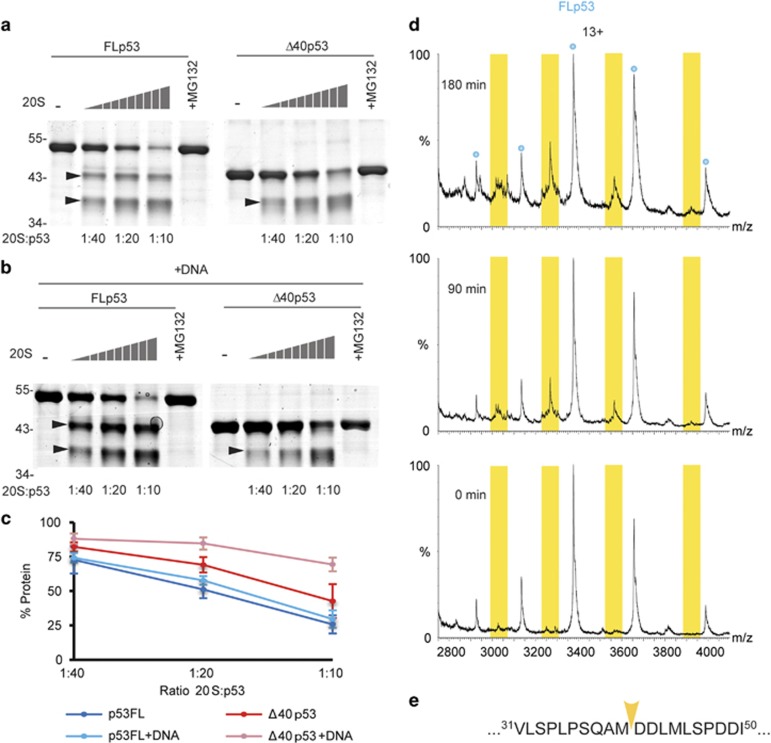

Figure 2.

Δ40p53 is generated through 20S proteasome cleavage. Degradation assays were carried out in the (a) absence or (b) presence of DNA (p53r2 duplex B), with purified p53 substrates and 20S proteasomes. FLp53 and Δ40p53 were incubated with serially diluted 20S proteasomes. Arrows indicate discrete p53 cleavage products that are generated via proteasomal processing. These emerging bands are not present when the proteasome inhibitor MG132 is added to the mixture. (c) Densitometric quantification analysis of SDS-PAGE results. Error bars represent S.D. of three repeats. (d) Native MS analysis of FLp53 processing by the 20S proteasome. A p53/20S proteasome mixture was incubated on ice. An aliquot of the sample was analyzed by MS at the indicated time points. Additional peaks arose between the charge series corresponding to the intact FLp53 monomer, consistent with cleavage of the first 40 amino acids. (e) The mapped cleavage site is shown by a yellow arrow on p53 sequence

Notably, in both experiments, FLp53 and Δ40p53 were not entirely degraded, but rather processed into discrete products: two cleavage products for FLp53, and a single product for Δ40p53 (Figures 2d and e). Moreover, the apparent size of the larger FLp53-derived product was very close to that of Δ40p53. Characterization of this latter product, which suggests that the Δ40p53 isoform can be generated by 20S proteasome-mediated processing of FLp53, is the focus of this study.

To examine the Δ40p53-like cleavage product, we applied the native MS approach, in which formation of the FLp53 cleavage product was monitored in a time-dependent manner (Figure 2d). At the first time point, five major peaks, corresponding to the 11+–15+ charge states of intact FLp53 were observed. After 90 min an additional single charge series centered at ~3450 m/z also appeared and its relative intensity increased up to the 180 min time point. The measured mass of this emerging charge series is 39 185±7 Da, relating to a distinct cleavage product between residue 40 and 41 of FLp53 (with the theoretical mass of 39 189 Da). This species corresponds precisely to the sequence of Δ40p53 lacking the first methionine residue (Figure 2e). In summary, these results suggest that the 20S proteasome can generate Δ40p53 via specific FLp53 cleavage.

Post-translational processing of FLp53 by the 20S proteasome generates the Δ40p53 isoform

To assess our hypothesis that Δ40p53 can be generated by 20S proteasome-mediated cleavage in cells, we introduced into the non-small-cell lung carcinoma cells, H1299, which are p53-deficient, WT FLp53.31 Cell extracts were incubated with increasing amounts of purified 20S proteasome. p53 forms were then detected using an anti-p53 polyclonal antibody. As expected, a band corresponding to Δ40p53 existed even before adding 20S proteasomes (Figure 3a). Nevertheless, its levels were clearly increased in dependence of 20S proteasome concentration (Figure 3a), suggesting that cellular Δ40p53 can be generated by 20S proteasome cleavage. To validate that the 20S proteolytic product is Δ40p53 and not another p53 isoform with a similar molecular weight, we performed the same experiment, while detecting p53 forms with a monoclonal antibody, raised against a p53 N-terminal epitope that is absent in Δ40p53 (DO-1). As expected, only FLp53 was detected (Supplementary Figure 2), supporting our hypothesis that Δ40p53 is generated by 20S proteolysis.

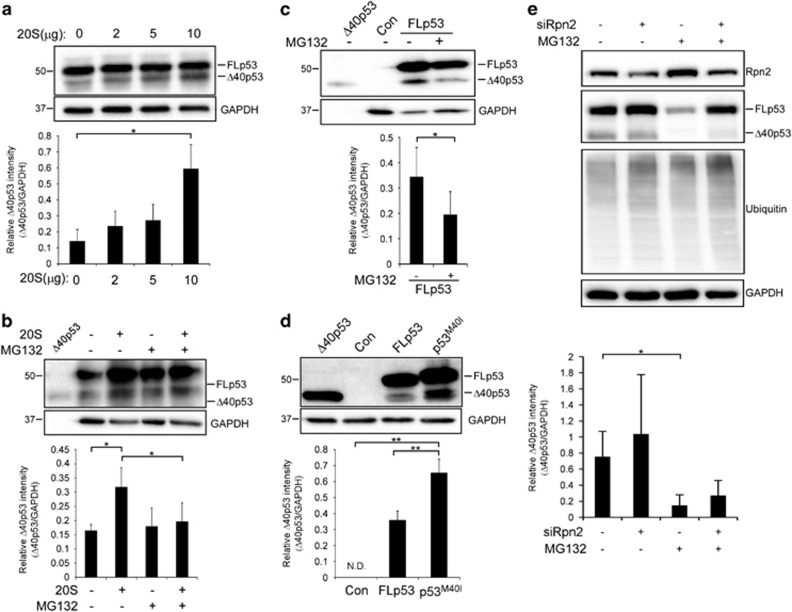

Figure 3.

Cellular FLp53 post-translational processing by the 20S proteasome generates the Δ40p53 isoform. (a) The non-small-cell lung carcinoma cell line, H1299, which is p53 deficient, was transiently transfected with pC53-SN3 vector expressing FLp53, followed by cell lysis. Cells extracts were incubated with the indicated elevated concentrations of 20S proteasome for 120 min at 37 °C and p53 forms were detected by SDS-PAGE. (b) H1299 cells were transiently transfected with pC53-SN3 vector expressing FLp53 followed by cell lysis. Cells extracts were incubated with 20S proteasome (10 μg) in the presence or absence of the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (50 μM) for 120 min at 37 °C and p53 forms were detected by SDS-PAGE. (c) H1299 cells were transiently transfected with pC53-SN3 vector expressing FLp53. After 24 h, cells were treated with proteasome inhibitor MG132 (10 μM) for 6 h. Cells were lysed and cell extracts were loaded on SDS-PAGE gel. Cells expressing an empty vector (Con) were used as negative controls. (d) H1299 cells were transiently transfected with the following vectors: pC53-SN3 vector (FLp53), pC53-SN3 vector containing a single in-frame mutation, substituting methionine (ATG) in position 40 to isoleucine (ATA) (p53M40I) to eliminate translation initiation from the alternative site and an empty vector (Con). Cells were lysed and cells extracts were loaded on SDS-PAGE gel. (e) HEK293T cells were transiently transfected to silence Rpn2. As controls, non-targeting siRNA (NT) was used. After 48 h, cells were treated with proteasome inhibitor MG132 (40 μM) for 3 h. Cells were lysed and cell extracts were loaded on SDS-PAGE gels, analyzed by western blot and visualized using various antibodies. In all experiments, the polyclonal anti-p53 antibody was used to detect p53 forms. The housekeeping protein GAPDH was used as a loading control. Purified Δ40p53 was loaded on gels as a control. Blots are of a representative experiment. Quantification demonstrates the average of four (a, c–e) or five (b) independent experiments. Measurements were subjected to Student’s t-test analysis, *P⩽0.05, **P⩽0.01. Error bars represents S.E. ND, not detected

To verify that the generation of Δ40p53 is dependent on proteolysis, H1299 cells were introduced with FLp53, and cell extracts were incubated with purified 20S proteasome in the presence and absence of the proteasome inhibitor MG132. Indeed, Figure 3b demonstrates that the addition of MG132 reduced Δ40p53 levels. Similarly, inhibiting 20S proteasome by treating cells with MG132, reduced the formation of the Δ40p53 isoform in vivo (Figure 3c). Taken together these findings support our view that Δ40p53 can be a product of 20S proteolysis.

Considering that alternative translation initiation at codon 40 is the accepted mechanism of Δ40p53 formation,18, 19, 20, 21 we wished to prevent this process by inserting a single in-frame mutation into the FLp53 over-expressing plasmid to substitute the Met codon to Ile (p53M40I). The WT and p53M40I constructs exhibited slight differences in their migratory properties, in agreement with previous single mutant analysis (Figure 3d).32 Nevertheless, the western blot analysis indicated the formation of a Δ40p53 form, despite the removal of the alternative translation site. Altogether, these results suggest that processing by the 20S proteasome is an alternative mechanism for generating the Δ40p53 isoform following FLp53 translation. To what extent each one of these processes contribute to Δ40p53 cellular levels remains to be determined.

Considering that p53 can be sent to degradation via both the 20S and 26S proteasomes,29 it was necessary to clarify that the formation of Δ40p53 in cells is specifically associated with 20S and not 26S proteolysis. We therefore silenced Rpn2 (PSMD1), a non-ATPase 19S proteasome subunit, in HEK293T cells using short interfering RNA (siRNA). Rpn2 depletion was previously shown to cause a significant reduction in 26S proteasome activity accompanied by an increase in 20S proteasome function.11, 33 Our results indicated that Rpn2 knockdown led to accumulation of ubiquitin–protein conjugates, as expected due to the reduction of 26S proteasome activity (Figure 3e). Δ40p53, though, was still detected in spite of Rpn2 depletion. Δ40p53 levels, however, were reduced, after the addition of MG132, either with or without silencing of Rpn2. Together these findings suggest that the 20S, rather than the 26S proteasome, facilitates Δ40p53 formation.

Δ40p53 modulates p53 gene expression

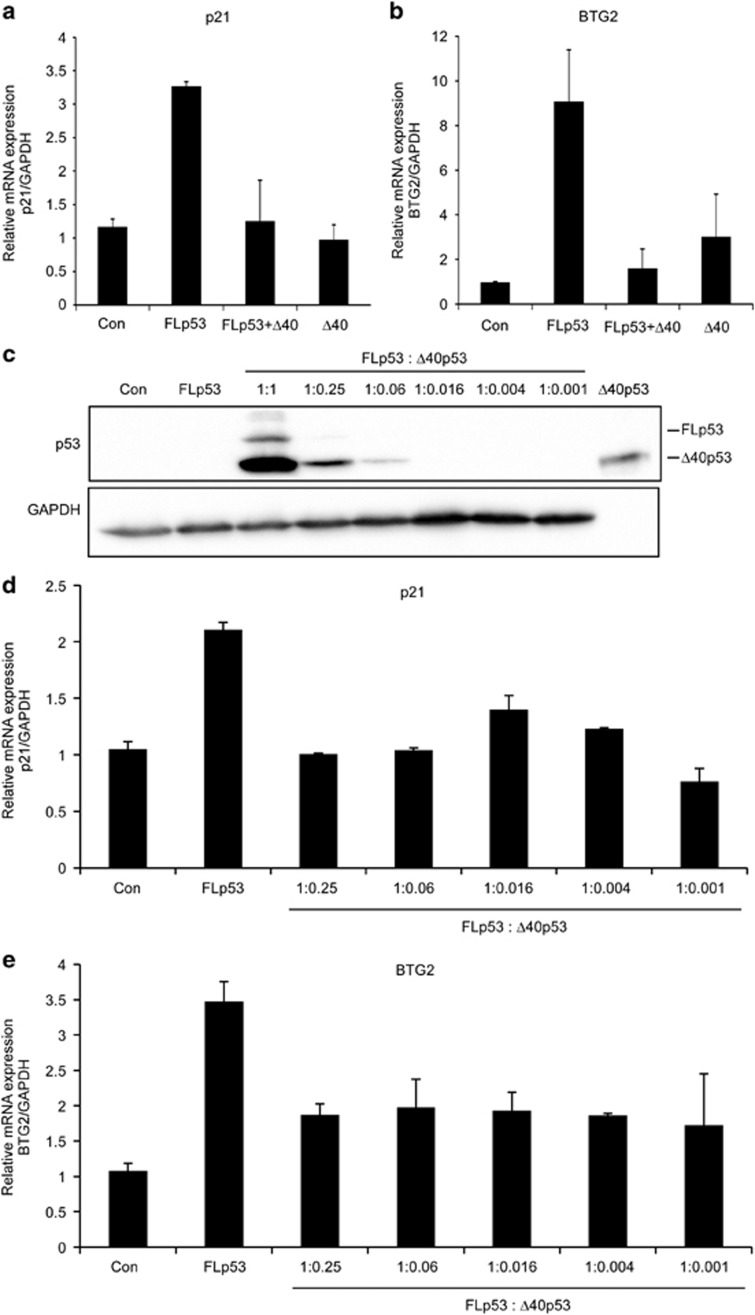

To examine whether Δ40p53 modulates the transcriptional activity of p53, we co-transfected H1299 cells with FLp53 and Δ40p53. As controls, FLp53 and Δ40p53 were transfected alone. Cells were collected and RNA was extracted. The mRNA expression levels of the well-characterized target genes p21 and BTG2 were measured by quantitative real-time PCR. As expected, expression of FLp53 induced the expression of its target genes (Figures 4a and b). In contrast, addition of Δ40p53 in 1 : 1 ratio (FLp53 +Δ40p53) significantly reduced the levels of p21 and BTG2. These results are in accordance with previous reports suggesting that Δ40p53 induces a dominant negative effect over WT FLp53 function.18, 34, 35

Figure 4.

Δ40p53 attenuates the transcriptional activity of FLp53. (a, b) H1299 cells were transiently co-transfected with 1 μg PSVL-p53 vector expressing p53 full-length (FLp53) and 1 μg SV-p53Δ40 vector expressing Δ40p53 (Δ40p53). As controls, cells were transfected with empty vector (Con), 1 μg of PSVL-p53 (FLp53) and 4 μg SV-p53Δ40 (Δ40p53) vectors alone. After 48 h, cells were lysed and RNA was extracted. The mRNA expression levels of the p53 target genes p21 (a) and BTG2 (b) were measured by quantitative real-time PCR using specific primers. (c–e) H1299 cells were transiently co-transfected with 5 μg FLp53 and Δ40p53 at serial dilutions, as indicated. As controls, cells were transfected with empty vector (Con) or 5 μg FLp53. Purified Δ40p53 was used as a positive control for the protein size. After 24 h, cells were lysed, and protein and RNA were extracted. (c) Western blots displaying FLp53 and Δ40p53 protein levels. GAPDH served as a loading control. As can be seen, the strong SV40 promoter of Δ40p53 led to high levels of protein expression in comparison to FLp53, consisting of the late SV40 promoter. Therefore, serial dilutions of Δ40p53 were co-transfected with FLp53, and the mRNA expression levels of p21 (d) and BTG2 (e) subsequently measured by quantitative real-time PCR, using specific primers. The results indicate that even low levels of Δ40p53 are sufficient to attenuate FLp53 function and reduce the expression levels of p21 and BTG2. Genes expression levels were normalized to GAPDH. Graphs represent an average of three independent experiments. Error bars represents S.E.

Considering the relatively high protein expression of Δ40p53 in comparison to that of FLp53 (Figure 4c), we next examined whether low levels of Δ40p53 are also capable of modulating the transcriptional activity of p53. To this end, we co-transfected H1299 cells with a constant amount of the FLp53, and serial dilutions of the Δ40p53 plasmid, from a FLp53/Δ40p53 ratio of 1 : 0.25–1 : 0.001 (Figure 4c). Then, cells were collected and mRNA was extracted. Our results indicated that although there was no change in the transfection amounts of FLp53, there was a reduction in the levels of the protein, in correlation with the lower dosage of the Δ40p53 plasmid (Figure 4c). This suggests that Δ40p53 stabilizes FLp53, probably due to the absence of MDM2 binding, as shown previously.36 Notably, we observed that low dilutions of Δ40p53, in which the expressed protein is not even detectable (Figure 4c), are sufficient for reducing p21 and BTG2 expression levels (Figures 4d and e). Thus, low cellular levels of Δ40p53 are sufficient for attenuation of p53 transcription activity. Altogether, these results suggest that the FLp53/Δ40p53 interaction modulates p53 transcriptional activity, and thus acts as a p53 negative regulator.

Full-length p53 and Δ40p53 form hetero-tetramers within cells

Formation of FLp53 and Δ40p53 hetero-oligomeric complexes could provide a reasonable explanation for the transactivation inhibition of Δ40p53 toward FLp53. We examined this possibility at first by applying the native MS approach. Spectra were acquired after mixing the two p53 proteins in the presence and absence of DNA. Mixed trimeric and tetrameric forms of the p53 proteins were detected in the absence of DNA (Figure 5a). Following DNA addition, which stabilizes the tetrameric state of the protein (Figure 1b), only homo- and hetero-tetramers were observed: (FLp53)4DNA, (Δ40p53)4DNA and (FLp53)2(Δ40p53)2DNA (Figure 5b). Notably, although theoretically different compositions of tetrameric FLp53 and Δ40p53 complexes could be conceived, only a dimer of FLp53 bound to a dimer of Δ40p53 was observed in the presence of DNA, suggesting the increased propensity for homo-dimer formation.

Figure 5.

Hetero-tetrameric p53 is formed through the association of FLp53 and Δ40p53 dimers. FLp53 and Δ40p53 were mixed in a ratio of 1 : 1, in the absence (a) and presence (b) of DNA (p53r2 RE), followed by native MS analysis of the species generated after overnight incubation at 4 °C. (c) H1299 cells were transiently transfected with pC53-SN3 vector expressing FLp53 (FLp53) or with an empty vector as a negative control (Con). After 48 h, cells were lysed and cells extracts were incubated with either monoclonal antibody against p53 N-terminus (DO-1) that is directed to an epitope that does not appear in Δ40p53 protein, in order to immunoprecipitate only FLp53, or with a non-specific IgG antibody as a negative control. Immunoprecipitates were loaded on SDS-PAGE gel, and p53 forms were detected using goat polyclonal anti-p53 horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody (p53HRP). To examine p53 expression, non-immunoprecipitated samples were loaded (input). Purified Δ40p53 was loaded as a positive control. This figure combines two exposures of the same gel, which are separated by a vertical line; the long exposure of the immunoprecipitated samples is shown on the left and the short exposure of the highly concentrated purified Δ40p53 protein is displayed on the right. The two original images are presented in Supplementary Figure 3. (d) HEK293T cells were lysed and cells extracts were incubated with either DO-1 antibody, to immuneprecipitate FLp53, or with a non-specific IgG antibody as a negative control. Immunoprecipitates were loaded on SDS-PAGE gel, and p53 forms were detected using p53HRP antibody. To examine p53 expression, non-immunoprecipitated samples were loaded (input). Purified Δ40p53 was loaded as a positive control. Results are a representative experiment of at least three independent experiments

To investigate whether FLp53/Δ40p53 hetero-complexes exist within the cellular environment co-immunoprecipitation was performed using extracts of H1299 cells transfected with either FLp53 or an empty vector as a negative control. FLp53, but not Δ40p53, was immunoprecipitated using the DO-1 antibody. The immunoprecipitated proteins were detected by western blot, using p53 polyclonal antibody. As expected, cellular introduction of FLp53 enables detection of both FLp53 and Δ40p53 (Figure 5c; Supplementary Figure 3). Moreover, Δ40p53 was pulled-down together with FLp53, indicating that Δ40p53 binds FLp53 protein. We next validated this interaction in HEK293T, endogenously expressing FLp53 and Δ40p53 by the same experimental settings. Figure 5d shows that the endogenously expressed Δ40p53 was co-immunoprecipitated with FLp53. Altogether, the results suggest that FLp53 interacts with Δ40p53 within cells.

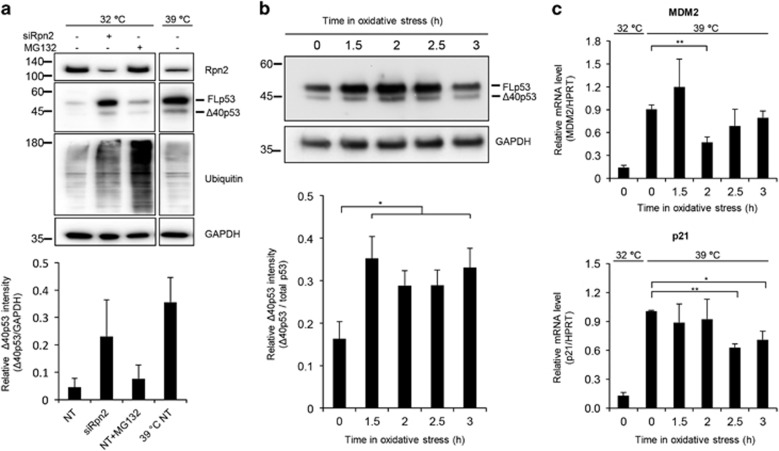

The generation of Δ40p53 is enhanced under oxidative conditions

Under oxidizing conditions, the 20S proteasome was identified as the major degradation machinery.37, 38, 39, 40, 41 Therefore, we expected that under such conditions an increase in Δ40p53 levels would be observed. In order to validate that the formation of Δ40p53 is specifically associated with the 20S and not the 26S proteasome, we used the A31N-ts20 BALB/c mouse cell line harboring a temperature-sensitive E1 variant. Consequently, under restrictive temperature (39 °C), the E1 enzyme is inactivated and protein ubiquitination and 26S proteasome-mediated degradation is repressed.42

Initially we validated that Δ40p53 formation, in A31N-ts20 cells, is 20S proteasome-dependent. To this end, Rpn2 was knocked down in A31N-ts20 cells grown at the permissive temperature (32 °C). As expected, due to impaired 26S proteasome activity, FLp53 was stabilized and accumulation of ubiquitin conjugates was observed (Figure 6a). However, in spite of 26S proteasome suppression, the formation of Δ40p53 was retained. Similarly, transferring cells to a 39 °C environment, which impairs the ubiquitination process,11, 29, 42 did not eliminate the formation of Δ40p53. Conversely, treating the cells with MG132 reduced Δ40p53 levels almost to its basal state. Overall, the results support our view that Δ40p53 formation is mediated by the 20S proteasome complex.

Figure 6.

Δ40p53 formation is increased under oxidative stress. (a) A31N-ts20 BALB/C mouse cells were grown at the permissive temperature (32 °C). In order to attenuate the 26S proteasome degradation pathway, cells were either transiently transfected with short interfering RNA (siRNA) targeting Rpn2 to silence its expression or shifted to the restrictive temperature (39 °C). As controls, non-targeting siRNA (NT) or MG132 were used. Cells were lysed and cell extracts were loaded on SDS-PAGE gel, analyzed for the expression of Rpn2, p53, ubiquitin-tagged proteins and GAPDH (as controls) by western blot. Samples were run on the same gel and presented lanes are from the same exposure. (b, c) To induce oxidative stress, cells cultured at 39 °C were treated with 100 μM DEM and collected at the indicated time points. (b) Cell exposed to oxidative stress were subjected to western blot analyses and p53 levels were probed using an anti-p53 antibody. Quantification of the bands indicates upregulation of Δ40p53 levels. The housekeeping protein GAPDH was used as a loading control. (c) Following the induction of oxidative stress, RNA was extracted and mRNA levels of MDM2 and p21 were measured by quantitative real-time PCR. Gene expression levels were normalized to HPRT. Quantification demonstrates the average of three (a, c) or seven (b) independent experiments. Measurements were subjected to Student’s t-test analysis, *P⩽0.05, **P⩽0.01. Error bars represents S.E. ND, not detected

Next, in order to investigate the impact of oxidizing conditions on Δ40p53 cellular levels, A31N-ts20 cells were treated with diethylmaleate (DEM), a glutathione-depleting compound causing accumulation of reactive oxygen species within the cell.43 We then monitored, over time, the endogenous levels of the p53 forms by immunoblot analysis, using an antibody directed toward the C-terminal region of p53, to ensure that the generated p53 forms are due to N-terminal, rather than C-terminal, cleavage (Figure 6b). We found that inducing oxidative stress at the restrictive temperature led to an increase in Δ40p53 levels, reaching maximum accumulation after 1.5 h (Figure 6b). This finding is in agreement with previous findings demonstrating an increase in Δ40p53 levels following exposure to hydrogen peroxide.44

To examine the effect of the DEM-induced Δ40p53 on p53 transactivation activity, we measured the mRNA levels of p53 target genes, p21 and MDM2, following treatment. Upon induction of oxidative stress, where Δ40p53 levels are increased (Figure 6b), mRNA expression levels of p21 and MDM2 were reduced (Figure 6c). Notably, the reduction in the expression of p21 and MDM2 occurs at different kinetics. This might be due to differences in DNA conformation, chromatin architecture or regulation by additional cooperating transcription factors.3 Taken together, this result implies that under oxidative stress, Δ40p53 attenuates FLp53 transcriptional activity in a dominant negative manner.

Discussion

Here, we show that the 20S proteasome specifically cleaves FLp53 to generate the Δ40p53 isoform lacking the first 40 amino acids. Only one residue, Met40, differentiates between the Δ40p53 isoform generated through alternative translation initiation and the species produced by 20S proteasomal processing. However, as the first methionine residue tends to be removed after expression, the two Δ40p53 forms are actually similar proteins. In agreement with previous studies our results indicate that FLp53 oligomerizes with Δ40p53.19, 20, 34, 45 Particularly, we suggest a defined stoichiometry wherein dimers of Δ40p53 interact with dimers of the full-length protein. Consequently, the transcriptional activity of p53 is modulated and the expression level of target genes is attenuated. Our data also reveal that under oxidative stress, Δ40p53 levels are increased in a 20S proteasome-dependent manner, leading to reduction in p53 transcriptional activity. Together our results suggest that an alternative post-translational mechanism mediated by the 20S proteasome is responsible for generating the Δ40p53 isoform so as to coordinate p53 function.

It has already been established that the cellular function of p53 is tightly controlled by numerous feedback loops. One major mechanism involves the E3 ubiquitin ligase, MDM2, which mediates p53 degradation via the ubiquitin 26S proteasome system.46 An additional layer of functional coordination involves the existence of multiple isoforms of p53 itself and its family members, p63 and p73, which modulate the different biological activities of the protein. Here, we propose an additional mechanism for controlling p53 activation that involves 20S proteasome-mediated cleavage of p53, leading to the generation of the Δ40p53 isoform, which acts in a dominant negative manner toward FLp53. We observed decreased expression of p53 target genes when Δ40p53 was co-expressed together with FLp53, even upon low levels of Δ40p53. Moreover, under oxidative stress conditions, where the 20S proteasome is the major degradation machinery, the generation of Δ40p53 serves to attenuate p53 transcription and by that balances its activity. These results are in accordance with other studies demonstrating p53 transcriptional inhibition in a Δ40p53-dependent manner.18, 34, 35 However, studies claiming gene-activating properties of Δ40p53 toward the p53 transcriptional response have been also reported.20, 22 Hence, it is possible that Δ40p53 differently affects p53 activity under diverse cellular conditions, as was shown in response to DNA damage or proteotoxic stress.19, 23, 34 Therefore, we conclude that the balance between Δ40p53 and FLp53 has an impact on the expression pattern of p53-inducible genes. Whether recruitment of diverse co-activators and chromatin remodeling factors, or different affinities toward DNA (as shown in Figure 1c) dictate Δ40p53 effect, remains elusive.

A key question that arises is why an alternative post-translational mechanism has evolved to generate Δ40p53. This may be due to the urgent need to regulate p53 function under stress conditions and following oxidative stress. Under these conditions, degradation precedes mainly through the 20S proteasome, while degradation by the 26S proteasome is compromised.37, 38, 39, 40 Thus, 20S proteasome-mediated cleavage of p53—generating the Δ40p53 variant—may provide an immediate leverage for p53 functional coordination. Moreover, by eliminating the key binding platform for MDM2, the most stringent negative regulator of p53 abundance—the dominant negative effect of Δ40p53 on p53 transcriptional activity, may be sustained considerably. In addition, it is likely that Δ40p53 gains additional proteolytic stability through cognate DNA binding, however how this contributes to modulating p53 response remains to be investigated.

In response to low-level oxidative stress, p53 exhibits antioxidant activities promoting cell survival; high-level oxidative stress, however, leads to prooxidative p53 activities promoting cell death.3 However, the mechanism that enables switching of p53 function from antioxidant to prooxidant remains unclear. Δ40p53 formation via the 20S proteasome may explain this paradoxical aspect of p53 activity. In this respect, it is important to note that many studies that assess p53 expression use the DO-1 antibody or alike, which are directed against p53 N-terminus. Because these antibodies do not recognize Δ40p53 it is unclear how frequent the expression of this isoform is. Thus, it remains to be examined whether other cellular stimuli also induce the 20S proteasome-mediated Δ40p53 formation.

It has been demonstrated that the 20S proteasome specifically cleaves the translation initiation factors eIF4G, a subunit of eIF4F, and eIF3a, a subunit of eIF3.47 Like Δ40p53, the processed proteins possessed distinct functional capabilities, that is, the proteasome-mediated cleavage of eIF4G or eIF3a affects the assembly of the ribosomal preinitiation complex on different cellular and viral mRNAs.47 Similarly, processing of the NF-κB1 precursor p105 into a functional p50 product by the 20S proteasome was also reported.48 Along these lines, the 20S proteasome has been shown to specifically cleave more than 20% of all cellular proteins in mammalian lysates.49 In these cases, unlike the ubiquitin 26S proteasome degradation system, proteolysis is not dependent on the enzymatic cascade required for ubiquitination, therefore substrates can be processed instantly (reviewed in Ben-Nissan and Sharon50). In conclusion, these studies together with our results, hint at a more general biological principle in which specific cleavage of cellular proteins by the 20S proteasome may not be solely for degradation purpose but rather to regulate distinct functional properties. Considering that the majority of proteasomes in mammalian cells were found to be uncapped 20S,51, 52 and that 44% of human protein-coding genes, including numerous signaling and regulatory proteins, are predicted to contain intrinsically disordered regions,53 making them susceptible to 20S cleavage, we anticipate that the number of proteins identified to be functionally modulated by the 20S proteasome will increase.

Materials and methods

Purification of the 20S proteasome

Rat livers were chosen as our source for 20S proteasomes, given the high evolutionary conservation of subunit sequences that exist between human and rat (>96% identity). Purification of the native rat 20S proteasome was performed as described previously.54, 55 In brief, rat livers were homogenized in buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCL (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and 250 mM sucrose. The extract was subjected to centrifugation, first at 1000 × g for 15 min. The supernatant was then diluted to 400 ml to a final concentration of 0.5 M NaCl and 1 mM DTT, and subjected to ultracentrifugation for 2.2 h at 145 000 × g. The supernatant was centrifuged again at 150 000 × g for 6 h. The pellet containing the proteasomes was re-suspended in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and loaded onto 1.8 l Sepharose 4B resin. Fractions containing the 20S proteasome were identified by their ability to hydrolyse the flurogenic peptide suc-LLVY-AMC in the presence of 0.02% SDS. Proteasome-containing fractions were then combined and loaded onto four successive anion exchange columns: Source Q15, HiTrap DEAE FF and Mono Q 5/50 GL (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA). Elution was performed with a 0–1 M NaCl gradient. Active fractions were combined, and buffer exchanged to 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH=7.4) containing 10 mM MgCl2 using 10 kD Vivaspin 20 ml columns (GE Healthcare). Samples were then loaded onto a CHT ceramic hydroxyapatite column (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, USA); a linear gradient of 10–400 mM phosphate buffer was used for elution. The purified 20S proteasomes were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, activity assays and MS analysis.

Purification of 26S proteasomes

Purification of the 26S protesome was carried out as previously described.54

Expression and purification of recombinant FLp53 and Δ40p53

To increase yields of soluble p53 expression, a lipoyl-domain tag was cloned at the N-terminal of the WT FLp53 gene, followed by a TEV protease cleavage site, as done previously.54 The expression construct for Δ40p53 was created in identical manner. p53 fusion proteins were then expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells as previously described,54 with some modifications. Briefly, 1.5 l cultures in 2YT were grown at 37 °C until log-phase, cooled to 16 °C for 30 min, induced with 1 mM IPTG and cultures supplemented with 0.1 mM ZnCl2. Expression was carried out for 16–22 h at 16 °C.

Bacterial cell pellets were lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 300 mM NaCl, 1 × Roche EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol) and cleared lysate loaded onto Nickel affinity resin equilibrated with Buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 300 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol). Bound protein was subsequently eluted with Buffer B (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 300 mM NaCl, 300 mM imidazole) and dialyzed overnight against dialysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol (v/v), 5 mM DTT) with TEV protease. Dialyzed protein was diluted 10-fold into dilution buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10% glycerol (v/v), 5 mM DTT) and loaded onto Q-Sepharose equilibrated with Buffer A1 (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 30 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol (v/v), 5 mM DTT). Elution was performed over a linear NaCl gradient to 100% Buffer B1 (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 M NaCl, 10% glycerol (v/v), 5 mM DTT). Peak fractions were concentrated to 5–7 mg/ml and loaded onto a Superdex200 10/30 size-exclusion column equilibrated with GF Buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7, 300 mM NaCl, 5 mM DTT, 0.5 M arginine), which was also the running and storage buffer.

Degradation assays

Given the marginal thermal stability of the purified endogenous FLp53 protein,56 which denatures readily at 37 °C, degradation assays were performed using different p53/20S proteasome ratios at a single time point rather than carrying out a time-course assay. Specifically, 5 μM purified p53 protein was incubated with serial dilutions of 20S proteasomes in the presence, or absence, of the proteasome inhibitor MG132, and incubated at 37 °C for 45 min. To test the effect of DNA binding on degradation, a 10-fold molar excess of p53r2 duplex B (5′-ttTGACATGCCCAGGCATGTCTa-3′) was incubated with p53 on ice for 30 min prior to addition of proteasomes. Proteolysis was quenched by the addition of Laemmli buffer and sample boiling. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by coomassie staining. Alternatively, 50 μg of cell extracts was incubated at 37 °C for 120 min with degradation buffer (10 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT) and serial dilutions of 20S proteasomes in the presence or absence of the proteasome inhibitor MG132. Proteolysis was quenched by the addition of sample buffer (140 mM Tris (pH 6.8), 22.4% glycerol, 6% SDS, 10% β-mercaptoethanol and 0.02% bromphenol blue) and sample boiling. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, followed by western blot analysis.

Native mass spectrometry analysis

Prior to MS measurements, aliquots of protein sample were buffer exchanged 2–3 times into 500 mM ammonium acetate using Bio-Spin 6 columns (Bio-Rad) or home-made desalting columns packed with Sephadex G-25 (GE Healthcare). For each MS experiment, about 2 μl of buffer exchanged sample (~10 μM) was loaded into gold-coated borosilicate needles prepared in-house.54 MS analysis was performed on a Synapt HDMS instrument (WATERS, Milford, MA, USA). Typical instrument parameters for the transmission of native complexes were as follows: backing pressure (mbar)=4, capillary voltage (kV)=1.1–1.3, sampling cone voltage (V)=80–100, extraction cone voltage (V) 0–2, nanoflow gas pressure (Bar)=0–0.15, trap collision energy (V)=12–20, transfer collision energy (V)=2–12, trap gas flow (ml/min)=1.5–3.5, trap bias voltage (V)=0–15.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays

DNA binding assays were performed by closely following previously published protocols.57, 58 In brief, a DNA duplex, incorporating a consensus 20 base-pair long p53 RE and extrahelical thymidine nucleosides at the 5′-end (5′-tGGGCATGTCCGGACATGCCC-3′), was radioactively labeled with [γ−32P]ATP and purified from denaturing 10% polyacrylamide gel, followed by overnight annealing to room temperature. Labeled DNA and purified WTp53 or Δ40p53 were incubated for 2 h at 20° in reaction mixtures containing <1 nM DNA and serially diluted p53 protein, ranging from 12 μM to 2 nM in a buffer made of 50 mM Tris HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP, 25 U/ml BSA, 10% glycerol, 10 mM DTT and 100 mM KCl. Protein–DNA mixtures were separated on a 6% non-denaturing acrylamide gel and bands subsequently visualized by GE Typhoon FLA7000 phosphoimager. In estimating protein–DNA affinities via EMSA, it should be noted that true Kd values are likely smaller (i.e., higher binding affinities), as the protein fraction available for sequence-specific DNA binding is lower than in the starting reaction mixtures. This phenomenon results from the tendency of the proteins to aggregate as indicated by the high-intensity bands in the gel wells.

Cell lines, transfections and treatments

The non-small-cell lung carcinoma cell line NCI-H1299 was maintained in RPMI-1640 media supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and Pen/Strep solution (Biological Industries, Kibbutz Beit-Haemek, Israel). Cells were cultured in a humidified incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The transfections into NCI-H1299 cells were conducted using the jetPEI reagent (Polyplus transfection, New York, NY, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The transformed human embryonic kidney cells, HEK293T cell line was maintained in DMEM media supplemented with 10% FCS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate and Pen/Strep solution (Biological Industries, Kibbutz Beit-Haemek, Israel). Oxidative stress was induced in A31N-ts20 BALB/C mouse cells cultured at 32 °C. To induce oxidative stress, cells were moved for 24 h to 39 °C and then treated with 100 μM DEM. Subsequently, cells were collected at different time points and analyzed by immunoblotting, as indicated. Given that in mouse, an alternative spliced p53 with an altered C-terminus exists,59 Pab421, a mouse antibody against the C-terminal region of p53, was used to prevent a possible overlap of bands. The increase in protein levels was quantified by dividing the band intensities of Δ40p53 by the sum of intensities of the FLp53 and Δ40p53 bands. Considering that in this experiment A31N-ts20 cells were already exposed to two different types of stressors (inhibition of 26S proteasome degradation and oxidative stress), a control experiment in the presence of the proteasome inhibitor MG132 could not be carried out, as the cells died. Values are averaged over seven independent experiments; errors represent S.Es.

For silencing experiments, the following siRNAs were used: Dharmacon ON-TARGET plus Human PSMD1(5707) siRNA (L-011363-01-0005), Dharmacon siGenome non-targeting siRNA Pool #2 (D-001206-14-05) and IDT Trifecta Kit Mouse DsiRNA (mm.Ri.Psmd1.13.1,2,3). JetPrime transfection reagent (Polyplus transfection, New York, NY, USA) was used for transfection of HEK293T cells, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Before transfection the growth medium was replaced with medium containing reduced FCS (2%). For electro transfection of A31N-ts20 BALB/c, 1 × 106 cells were mixed with 150 pmol of siRNA, and transfected according to the manufacturer’s instructions, using a poring pulse of 125 V for 5 ms. After electroporation, cells were cultured at 32 °C for 24 h, following 24 h of incubation at 32 °C, and cells were transferred to 39 °C for another 24 h. About 48 h post transfection, cells were treated with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (40 μM) for 3 h, collected and analyzed by immunoblotting, as indicated.

Compounds and plasmids

The WT p53 expression plasmid, pC53-SN3, containing the p53 5′-UTR coding region, as well as the proximal non-regulatory portion of the 3′-UTR sequence was kindly provided by B Vogelstein (Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA). This vector was used as a template for site-directed mutagenesis to produce the plasmid carrying p53 with the mutation M40I (p53M40I).

The p53M40I carrying plasmid was constructed by site-directed mutagenesis using the QuickChange kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions using specific primers to create the specific mutation altering ATG codon (Methionine) at position 40 into ATA codon (Isoleucine). The following primers were used:

Forward: 5′-CCCTTGCCGTCCCAAGCAATAGATGATTTGATGCTGTCCC-3′

Reverse: 5′-GGGACAGCATCAAATCATCTATTGCTTGGGACGGCAAGGG-3′

The Δ40p53 expressing vector SV-p53Δ40 was kindly provided by Prof. Jean-Christophe Bourdon (University of Dundee, Ninewells Hospital, Centre for Oncology and Molecular Medicine, CR-UK Cell Transformation Research Group, Dundee, UK.) PSVL-p53 vector expressing WTp53 full length (FLp53) was constructed by cloning the human WTp53 cDNA sequence into PSVL expression vector as described previously.60

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed in Tris triton lysis buffer (TLB) buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, 100 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate and 0.1% SDS) supplemented with protease inhibitor mixture (EMD Millipore) for 20 min on ice. Extracts were analyzed for protein concentration by BCA protein assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For electrophoresis, 50 μg of protein extracts was dissolved in sample buffer (140 mM Tris (pH 6.8), 22.4% glycerol, 6% SDS, 10% β-mercaptoethanol and 0.02% bromphenol blue) boiled and loaded on 10% polyacrylamide gels containing SDS. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Ponceau S stain (Sigma-Aldrich Corporation) was used for membrane staining to assess protein loading. The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit polyclonal anti-p53, H47 (produced in our laboratory); goat polyclonal anti-p53 horseradish peroxidase-conjugated (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) PAb421 mouse monoclonal anti-p53 directed to the C-terminal were purified from ascetic fluids, mouse monoclonal anti-p53 antibody, DO-1, directed against residues 21–25 in p53 N′ terminus that are not included in the Δ40p53 isoform (kindly provided by Prof. Sir David Lane (p53 Laboratory, A*STAR, Singapore). The protein–antibody complexes were detected by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and the ECL kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), using the ChemiDoc MP imaging system (Bio-Rad).

Co-Immunoprecipitation

Cells were lysed in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10% glycerol), supplemented with protease inhibitor mixture (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) for 20 min on ice. Extracts were pre-cleared for 2 h with 30 μl of protein A beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA). Following pre-clearing, extracts were analyzed for protein concentration by BCA protein assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 500 μg of protein extracts was incubated either with mouse monoclonal anti-p53 antibody, DO-1, directed to p53 N’ terminus that is not included in Δ40p53 isoform (kindly provided by Prof. Sir David Lane (p53 Laboratory, A*STAR, Singapore), or with non-specific IgG as a negative control (Sigma-Aldrich Corporation, St. Louis, MO, USA). Immune complexes were precipitated overnight at 4 °C followed by incubation with protein A beads for additional 2 h. The immunoprecipitated material was washed three times with PBS. The pellet was then re-suspended in SDS sample buffer and analyzed by western blotting using goat polyclonal anti-p53 horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody that recognizes both FLp53 and Δ40p53 proteins.

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated using NucleoSpin kit (Macherey–Nagel, Duren, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. A 2 μg aliquot of the total RNA was reverse transcribed using Bio-RT (Bio-Lab, Jerusalem, Israel) and random hexamer primers (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). QRT-PCR was performed with ABI StepOne instrument (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using Platinum SYBR Green FastMix (Quanta Biosciences, Beverly, MA, USA). Specific primers were designed for the following genes: human BTG2, human p21WAF mouse MDM2, mouse p21WAF. Gene expression levels were normalized to human GAPDH and mouse HPRT, in human and mouse cells, respectively (primers sequences are listed in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). QRT-PCR data are described in arbitrary units.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Profs. Alan Fersht and Assaf Friedler for providing us a vector with the full-length p53 sequence and the HLT tag, respectively. We are thankful to Prof. Jean-Christophe Bourdon for providing us a vector with the Δ40p53 isoform sequence. We also thank Mr. Pratik Vyas and Prof. Tali Haran for their assistance in carrying out the EMSA experiments. In addition, we are honored to receive financial support of a Starting Grant from the European Research Council (ERC) (Horizon 2020)/ERC Grant Agreement no. 636752, and the Minerva Foundation, with funding from the Federal Ministry for Education and Research, Germany (to MS). We also wish to express our gratitude for the financial support of a Center of Excellence of the Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute (FAMRI), and by the Israel Science Foundation ISF-MOKED Center from the Israeli Academy of Sciences (to VR), and the Israel Science Foundation [349/12] (to ZS). VR is the incumbent of the Norman and Helen Asher Professorial Chair for Cancer Research at the Weizmann Institute of Science.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Cell Death and Differentiation website (http://www.nature.com/cdd)

Edited by X Lu

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Hoh J, Jin S, Parrado T, Edington J, Levine AJ, Ott J. The p53MH algorithm and its application in detecting p53-responsive genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002; 99: 8467–8472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joerger AC, Fersht AR. Structural biology of the tumor suppressor p53. Annu Rev Biochem 2008; 77: 557–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckerman R, Prives C. Transcriptional regulation by p53. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2010; 2: a000935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosh R, Rotter V. When mutants gain new powers: news from the mutant p53 field. Nat Rev Cancer 2009; 9: 701–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oren M. Decision making by p53: life, death and cancer. Cell Death Differ 2003; 10: 431–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelstein B, Lane D, Levine AJ. Surfing the p53 network. Nature 2000; 408: 307–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieging KT, Mello SS, Attardi LD. Unravelling mechanisms of p53-mediated tumour suppression. Nat Rev Cancer 2014; 14: 359–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joerger AC, Fersht AR. Structural biology of the tumor suppressor p53. Annu Rev Biochem 2008; 77: 557–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chene P. Inhibiting the p53-MDM2 interaction: an important target for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2003; 3: 102–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pant V, Lozano G. Limiting the power of p53 through the ubiquitin proteasome pathway. Genes Dev 2014; 28: 1739–1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsvetkov P, Reuven N, Prives C, Shaul Y. Susceptibility of p53 unstructured N terminus to 20S proteasomal degradation programs the stress response. J Biol Chem 2009; 284: 26234–26242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joruiz SM, Bourdon JC. p53 isoforms: key regulators of the cell fate decision. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2016; 6: a026039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivares-Illana V, Fahraeus R. p53 isoforms gain functions. Oncogene 2010; 29: 5113–5119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoury MP, Bourdon JC. p53 isoforms: an intracellular microprocessor? Genes Cancer 2011; 2: 453–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoubala M, Murray-Zmijewski F, Khoury MP, Fernandes K, Perrier S, Bernard H et al. p53 directly transactivates delta133p53alpha, regulating cell fate outcome in response to DNA damage. Cell Death Differ 2011; 18: 248–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdon JC, Fernandes K, Murray-Zmijewski F, Liu G, Diot A, Xirodimas DP et al. p53 isoforms can regulate p53 transcriptional activity. Genes Dev 2005; 19: 2122–2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourougaa K, Naski N, Boularan C, Mlynarczyk C, Candeias MM, Marullo S et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress induces G2 cell-cycle arrest via mRNA translation of the p53 isoform p53/47. Mol Cell 2010; 38: 78–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtois S, Verhaegh G, North S, Luciani MG, Lassus P, Hibner U et al. DeltaN-p53, a natural isoform of p53 lacking the first transactivation domain, counteracts growth suppression by wild-type p53. Oncogene 2002; 21: 6722–6728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi R, Markovic SN, Scrable HJ. Dominant effects of Delta40p53 on p53 function and melanoma cell fate. J Invest Dermatol 2014; 134: 791–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y, Stephen CW, Luciani MG, Fahraeus R. p53 Stability and activity is regulated by Mdm2-mediated induction of alternative p53 translation products. Nat Cell Biol 2002; 4: 462–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover R, Ray PS, Das S. Polypyrimidine tract binding protein regulates IRES-mediated translation of p53 isoforms. Cell Cycle 2008; 7: 2189–2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier B, Gluba W, Bernier B, Turner T, Mohammad K, Guise T et al. Modulation of mammalian life span by the short isoform of p53. Genes Dev 2004; 18: 306–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SC, Karoly ED, Taatjes DJ. The human DeltaNp53 isoform triggers metabolic and gene expression changes that activate mTOR and alter mitochondrial function. Aging Cell 2013; 12: 863–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pehar M, O'Riordan KJ, Burns-Cusato M, Andrzejewski ME, del Alcazar CG, Burger C et al. Altered longevity-assurance activity of p53:p44 in the mouse causes memory loss, neurodegeneration and premature death. Aging Cell 2010; 9: 174–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharon M. Biochemistry. Structural MS pulls its weight. Science 2013; 340: 1059–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlt C, Ihling CH, Sinz A. Structure of full-length p53 tumor suppressor probed by chemical cross-linking and mass spectrometry. Proteomics 2015; 15: 2746–2755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagel K, Natan E, Hall Z, Fersht AR, Robinson CV. Intrinsically disordered p53 and its complexes populate compact conformations in the gas phase. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2013; 52: 361–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain C, Miller S, Ahn J, Prives C. The N terminus of p53 regulates its dissociation from DNA. J Biol Chem 2000; 275: 39944–39953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asher G, Tsvetkov P, Kahana C, Shaul Y. A mechanism of ubiquitin-independent proteasomal degradation of the tumor suppressors p53 and p73. Genes Dev 2005; 19: 316–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock AN, Henckel J, DeDecker BS, Johnson CM, Nikolova PV, Proctor MR et al. Thermodynamic stability of wild-type and mutant p53 core domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997; 94: 14338–14342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker SJ, Markowitz S, Fearon ER, Willson JK, Vogelstein B. Suppression of human colorectal carcinoma cell growth by wild-type p53. Science 1990; 249: 912–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Mowery RA, Ashley J, Hentz M, Ramirez AJ, Bilgicer B et al. Abnormal SDS-PAGE migration of cytosolic proteins can identify domains and mechanisms that control surfactant binding. Protein Sci 2012; 21: 1197–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craxton A, Butterworth M, Harper N, Fairall L, Schwabe J, Ciechanover A et al. NOXA, a sensor of proteasome integrity, is degraded by 26S proteasomes by an ubiquitin-independent pathway that is blocked by MCL-1. Cell Death Differ 2012; 19: 1424–1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell DJ, Hrstka R, Candeias M, Bourougaa K, Vojtesek B, Fahraeus R. Stress-dependent changes in the properties of p53 complexes by the alternative translation product p53/47. Cell Cycle 2008; 7: 950–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A, Stewart D, Matlashewski G. Regulation of human p53 activity and cell localization by alternative splicing. Mol Cell Biol 2004; 24: 7987–7997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafsi H, Santos-Silva D, Courtois-Cox S, Hainaut P. Effects of delta40p53, an isoform of p53 lacking the N-terminus, on transactivation capacity of the tumor suppressor protein p53. BMC Cancer 2013; 13: 134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering AM, Davies KJ. Degradation of damaged proteins: the main function of the 20S proteasome. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 2012; 109: 227–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken CT, Kaake RM, Wang X, Huang L. Oxidative stress-mediated regulation of proteasome complexes. Mol Cell Proteomics 2011; 10: R.110.006924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breusing N, Grune T. Regulation of proteasome-mediated protein degradation during oxidative stress and aging. Biol Chem 2008; 389: 203–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grune T, Catalgol B, Licht A, Ermak G, Pickering AM, Ngo JK et al. HSP70 mediates dissociation and reassociation of the 26S proteasome during adaptation to oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med 2011; 51: 1355–1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Yen J, Kaiser P, Huang L. Regulation of the 26S proteasome complex during oxidative stress. Sci Signal 2010; 3: ra88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvat C, Acquaviva C, Scheffner M, Robbins I, Piechaczyk M, Jariel-Encontre I. Molecular characterization of the thermosensitive E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme cell mutant A31N-ts20. Requirements upon different levels of E1 for the ubiquitination/degradation of the various protein substrates in vivo. Eur J Biochem 2000; 267: 3712–3722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalo E, Kogan-Sakin I, Solomon H, Bar-Nathan E, Shay M, Shetzer Y et al. Mutant p53R273H attenuates the expression of phase 2 detoxifying enzymes and promotes the survival of cells with high levels of reactive oxygen species. J Cell Sci 2012; 125(Pt 22): 5578–5586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambino V, De Michele G, Venezia O, Migliaccio P, Dall'Olio V, Bernard L et al. Oxidative stress activates a specific p53 transcriptional response that regulates cellular senescence and aging. Aging Cell 2013; 12: 435–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson WR, Kari C, Ren Q, Daroczi B, Dicker AP, Rodeck U. Differential regulation of p53 function by the N-terminal DeltaNp53 and Delta113p53 isoforms in zebrafish embryos. BMC Dev Biol 2010; 10: 102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris SL, Levine AJ. The p53 pathway: positive and negative feedback loops. Oncogene 2005; 24: 2899–2908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baugh JM, Pilipenko EV. 20S proteasome differentially alters translation of different mRNAs via the cleavage of eIF4F and eIF3. Mol Cell 2004; 16: 575–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorthy AK, Savinova OV, Ho JQ, Wang VY, Vu D, Ghosh G. The 20S proteasome processes NF-kappaB1 p105 into p50 in a translation-independent manner. EMBO J 2006; 25: 1945–1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baugh JM, Viktorova EG, Pilipenko EV. Proteasomes can degrade a significant proportion of cellular proteins independent of ubiquitination. J Mol Biol 2009; 386: 814–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Nissan G, Sharon M. Regulating the 20S proteasome ubiquitin-independent degradation pathway. Biomolecules 2014; 4: 862–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabre B, Lambour T, Delobel J, Amalric F, Monsarrat B, Burlet-Schiltz O et al. Subcellular distribution and dynamics of active proteasome complexes unraveled by a workflow combining in vivo complex cross-linking and quantitative proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics 2012; 12: 687–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabre B, Lambour T, Garrigues L, Ducoux-Petit M, Amalric F, Monsarrat B et al. Label-free quantitative proteomics reveals the dynamics of proteasome complexes composition and stoichiometry in a wide range of human cell lines. J Proteome Res 2014; 13: 3027–3037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Lee R, Buljan M, Lang B, Weatheritt RJ, Daughdrill GW, Dunker AK et al. Classification of intrinsically disordered regions and proteins. Chem Rev 2014; 114: 6589–6631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscovitz O, Ben-Nissan G, Fainer I, Pollack P, Mizrachi L, Sharon M. The Parkinson’s-associated protein DJ-1 regulates the 20S proteasome. Nat Commun 2015; 6: 6609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscovitz O, Tsvetkov P, Hazan N, Michaelevski I, Keisar H, Ben-Nissan G et al. A mutually inhibitory feedback loop between the 20S proteasome and its regulator, NQO1. Mol Cell 2012; 47: 76–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt T, Kaar JL, Fersht AR, Veprintsev DB. Stability of p53 homologs. PLoS ONE 2012; 7: e47889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayner M, Rozenberg H, Kessler N, Rabinovich D, Shaulov L, Haran TE et al. Structural basis of DNA recognition by p53 tetramers. Mol Cell 2006; 22: 741–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beno I, Rosenthal K, Levitine M, Shaulov L, Haran TE. Sequence-dependent cooperative binding of p53 to DNA targets and its relationship to the structural properties of the DNA targets. Nucleic Acids Res 2011; 39: 1919–1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf D, Harris N, Goldfinger N, Rotter V. Isolation of a full-length mouse cDNA clone coding for an immunologically distinct p53 molecule. Mol Cell Biol 1985; 5: 127–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaulsky G, Goldfinger N, Ben-Ze'ev A, Rotter V. Nuclear accumulation of p53 protein is mediated by several nuclear localization signals and plays a role in tumorigenesis. Mol Cell Biol 1990; 10: 6565–6577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourie AM, Hupp TR, Lane DP, Sang BC, Barbosa MS, Sambrook JF et al. HSP70 binding sites in the tumor suppressor protein p53. J Biol Chem 1997; 272: 19471–19479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.