Abstract

Background

The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) epidemic is associated with a significant increase in the incidence of tuberculosis (TB); however, little is known about the quality of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB)-specific cellular immune responses in coinfected individuals.

Methods

A total of 137 HIV-1-positive individuals in Durban, South Africa, were screened with the use of overlapping peptides spanning Ag85A, culture filtrate protein 10 (CFP-10), early secretory antigen target 6 (ESAT-6), and TB10.4, in an interferon (IFN)-γ enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay. Intracellular cytokine staining for MTB-specific production of IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and interleukin (IL)-2 was performed, as was ex vivo phenotyping of memory markers on MTB-specific T cells.

Results

A total of 41% of subjects responded to ESAT-6 and/or CFP-10, indicating the presence of latent MTB infection. The proportion of MTB-specific IFN-γ+/TNF-α+ CD4+ cells was significantly higher than the proportion of IFN-γ+/IL-2+ CD4+ cells (P = .0220), and the proportion of MTB-specific IL-2-secreting CD4 cells was inversely correlated with the HIV-1 load (P = .0098). MTB-specific CD8 T cells were predominately IFN-γ+/TNF-α+/IL-2−. Ex vivo memory phenotyping of MTB-specific CD4 and CD8 T cells indicated an early to intermediate differentiated phenotype for the population of effector memory cells.

Conclusions

Polyfunctional MTB-specific CD4 and CD8 T cell responses are maintained in the peripheral blood of HIV-1-positive individuals, in the absence of active disease, and the functional capacity of these responses is affected by HIV-1 disease status.

Approximately 90% of HIV-1-negative individuals infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) do not develop active disease after initial MTB infection; this observation provides compelling evidence that the host immune response is usually successful in containing the infection [1, 2]. Coinfection with HIV-1, which impairs cellular immune responses, greatly increases the risk of development of active tuberculosis (TB) [3, 4], and the HIV-1 epidemic has contributed significantly to the rapid spread of TB, as well as to subsequent increases in the number of cases of active disease in such areas as sub-Saharan Africa [5].

Previous studies in interferon (IFN)-γ-deficient mice and in humans with IFN-γ receptor abnormalities have indicated an essential role of IFN-γ-producing T cells in the containment of MTB infection [6–9]. IFN-γ-secreting T cells specific for multiple immunogenic antigens of MTB have been identified, including the Ag85 complex, culture filtrate protein 10 (CFP-10), early secretory antigenic target 6 (ESAT-6), heat shock protein 65, and TB10.4 [10–16]. Recently, tests have been developed for immunodiagnosis of MTB infection on the basis of the presence of IFN-γ-secreting cells in response to the following antigens in the region of difference 1 (RD1): ESAT-6 and CFP-10; these tests have been shown to be more specific and sensitive than tuberculin skin tests [17]. The RD1 antigens have been deleted from all Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccines [18] and are, therefore, useful in differentiating individuals who have been exposed to MTB within a BCG-vaccinated population. Although the majority of studies of the performance of IFN-γ release assays for the detection of MTB infection have been performed in HIV-1-negative cohorts, the performance of these assays has not been found to be significantly affected by HIV-1 infection in studies involving HIV-1-positive subjects [19–24].

Despite the high prevalence of coinfection with HIV-1 and MTB, very little information is currently known about the functional capacity of MTB-specific cellular immune responses in HIV-1-positive individuals. A high sensitivity for the detection of MTB infection has been noted with the use of an RD1-based IFN-γ enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay in the screening of HIV-1-positive patients with TB, including both adults and children [19, 21, 25]. However, the degree to which HIV-1 coinfection influences the magnitude of responding MTB-specific T cells in patients with TB varies in different study cohorts [19, 26, 27]. Moreover, detailed analyses of the effector functions of MTB-specific T cell responses in HIV-1-positive individuals with latent and active TB, as well as the extent to which HIV-1 disease progression influences the functional capacity of these responses, have not been well described.

In the present study, we characterized the MTB-specific T cell response in HIV-1-positive individuals with latent TB from KwaZulu Natal, South Africa, where 80% of active TB cases are associated with HIV-1 infection [28]. Our aims were to determine the magnitude and breadth of responses to mycobacterial antigens, to determine the relationship between MTB-specific T cell responses and parameters of HIV-1 disease progression, and to assess the ex vivo phenotype of MTB-specific T cells and their capacity to secrete multiple cytokines in individuals with chronic HIV-1 infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

One hundred thirty-seven subjects were recruited from the Sinikithemba Care Center at McCord Hospital in Durban, South Africa. All subjects were HIV-1 positive and antiretroviral therapy naive, and they had no previous history of TB symptoms, diagnosis, or treatment, as well as no current symptoms of active TB. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from blood samples by means of density centrifugation with ficoll-hypaque (Sigma). The HIV-1 load was measured using the Roche Amplicor assay (version 1.5). The median viral load of the cohort was 20,500 HIV-1 RNA copies/mL of plasma, and the median absolute CD4 cell count was 359 cells/μL of whole blood. Five HIV-1-negative subjects from the United States who were not vaccinated with BCG and who had no previous history of TB were included as negative controls. All study participants provided written, informed consent for the study, which was approved by institutional review boards.

Synthetic peptides

Peptides (16- to 18-mers overlapping by 10 aa) corresponding to the sequence of the MTB antigens Ag85A, CFP-10, ESAT-6, and TB10.4 were synthesized on an automated peptide synthesizer. For initial screening purposes, peptides were arranged into pools of 9 peptides each in a matrix fashion, such that each peptide was uniquely represented in 2 pools [29].

IFN-γ ELISPOT assays

Ninety-six-well polyvinylidene plates (Millipore) were precoated with 0.5 μg/mL anti-human IFN-γ monoclonal antibody (1-D1K; Mabtech). A total of 100,000 freshly isolated PBMCs were added per well in a volume of 100 μL of R10 medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 10 mmol/L HEPES buffer, 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, and 50 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin). Peptides were added at a final concentration of 2 μg/mL. Negative controls consisted of wells containing PBMCs incubated with medium alone. Positive controls consisted of wells containing PBMCs and 12.5 μg/mL phytohemagglutinin (PHA; Murex Biotech). Plates were incubated overnight at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator and were washed the next morning; 0.5 μg/mL biotinylated anti-IFN-γ antibody (7-B6-1; Mabtech) was then added for 1.5 h, and the plates were washed and incubated with streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase (Mabtech) for 45 min. The plates were developed by the addition of the alkaline phosphatase color reagents 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate and nitro blue tetrazolium chloride in Tris buffer (pH 9.5). The reaction was stopped by washing with tap water after the appearance of intense blue spots in the positive control wells. Spots were counted on an ELISPOT reader (AID), and responses were considered to be positive if the number of spots per well minus the background value was ⩾50 spot-forming cells (SFCs)/106 PBMCs (i.e., if the value was greater than the mean value plus 3 times greater than the standard deviation of the responses in the negative control subjects).

Intracellular cytokine staining and immunophenotyping

A total of 0.5 × 106 PBMCs were incubated with 1 μg of peptide in 1 mL of R10 medium overnight (12–14 h) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. After the first hour of incubation, 10 μg of brefeldin A (Sigma) was added. The cells were washed and stained with the following surface antibodies at room temperature for 15 min: peridinin-chlorophyll-protein complex (PerCP)-conjugated anti-CD4, allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated anti-CD8, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-CD27, APC- conjugated anti-CD28, APC-conjugated anti-CD45RA, FITC-conjugated anti-CCR7 (R&D Systems), and APC-conjugated CD62L. The cells were washed, fixed, and permeabilized (Caltag reagents A and B; Caltag Laboratories). The following intracellular antibodies were then added: FITC-conjugated anti-IFN-γ, phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated TNF-α, PE-conjugated IL-2, and APC-conjugated Granzyme B (GrB; Caltag Laboratories). All antibodies were from Becton Dickinson, unless otherwise noted. The cells were incubated for 15 min and then were washed and acquired on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer with the use of CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson). Negative controls consisting of PBMCs incubated with medium alone were included in each assay. Responses ⩾0.03% above the background value were considered to be positive. For phenotypic analysis of CD4 cells, peptide-stimulated cells were gated on CD4+ TNF-α+ cells and analyzed for expression of CD27, CD28, CD45RA, CCR7, and CD62L. For phenotypic analysis of CD8 cells, peptide- stimulated cells were gated on CD8+ TNF-α+ cells and analyzed for expression of CD27, CD28, CD45RA, CCR7, and GrB.

Statistical analysis

The Mann-Whitney U test and Spearman rank correlation were performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 4.0; GraphPad Prism). P < .05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Identification of MTB-specific T cell responses in HIV-1- positive individuals with latent MTB infection

To characterize the MTB-specific cellular immune response in HIV-1- positive individuals in an area of endemicity for TB who are at high risk for reactivation and development of active disease, we screened a large cohort of individuals with chronic HIV-1 infection for the presence of IFN-γ-producing T cells. Screening was performed using an ELISPOT assay for the detection of MTB RD1 antigens CFP-10 and ESAT-6, as well as the immunogenic secreted antigens Ag85A [11] and TB10.4 [30, 31]. Fifty-six (41%) of 137 subjects had positive responses to ESAT-6 and/or CFP-10, according to the ELISPOT assay (data not shown), and they were thus identified as subjects with latent MTB infection. No significant differences in either absolute CD4 cell count or viral load were observed between individuals with detectable and undetectable MTB-specific responses in the IFN-γ ELISPOT assay (data not shown).

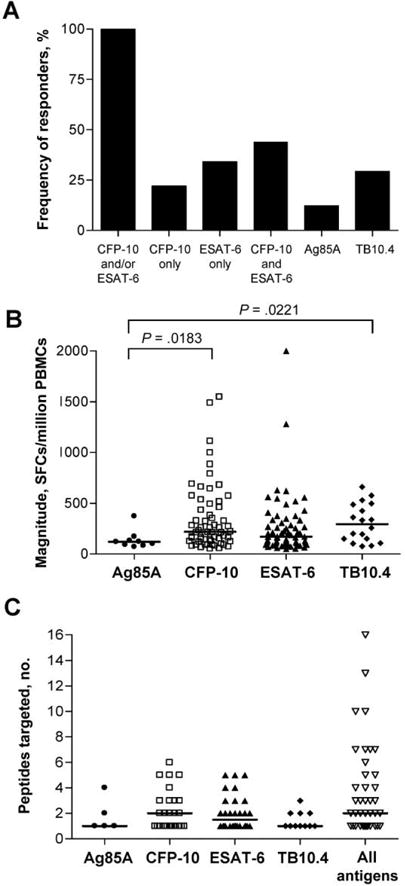

Forty-one of the 56 subjects with positive responses in the initial screening performed with the peptide pools had sufficient numbers of cells available with which to perform a second ELISPOT assay the next day to confirm the individual peptides eliciting the positive response. All of the subjects responded to at least one peptide in either CFP-10 and/or ESAT-6, thus confirming all initial positive responses at an individual peptide level; 44% of subjects responded to peptides from both CFP-10 and ESAT-6, whereas 34% responded to ESAT-6 only and 22% responded to CFP-10 only (figure 1A). All subjects responding to peptides in Ag85A or TB10.4 also responded to at least one other peptide in ESAT-6 and/or CFP-10 (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Magnitude and breadth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB)–specific T cell responses in HIV-positive individuals with latent infection. 18-mer overlapping peptides spanning the Ag85A, culture filtrate protein 10 (CFP-10), early secretory antigen target 6 (ESAT-6), and TB10.4 proteins were arranged in pools of 9 peptides each in a matrix fashion such that each peptide was represented in 2 pools. Freshly isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were screened for positive responses to the peptide pools in an interferon (IFN)-γ enzyme- linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay; responses to individual peptides were reconfirmed in a second ELISPOT assay. Positive responses to individual 18-mer peptides from the confirmation assay are shown; for 41 individuals, a second confirmatory ELISPOT assay with individual peptides was performed. A, Frequency (percentage) of subjects with a positive IFN-γ ELISPOT assay response who demonstrated a response to each of the 4 antigens tested. Individuals were considered to be “responders” if they targeted at least one peptide within the antigen indicated. B, Magnitude of T cell responses to individual peptides (Ag85A, CFP-10, ESAT-6, and TB10.4 peptides) in an IFN-γ ELISPOT assay. Horizontal lines denote the median number of spot-forming cells (SFCs) per million PBMCs. C, No. of peptides targeted per individual within each antigen and across all antigens tested. Horizontal lines denote median values.

The magnitudes of the positive responses to individual peptides within the 4 antigens tested ranged from 50 to 2000 SFCs/million PBMCs. The median magnitude was highest for TB10.4- specific cells, although this finding was not significantly different from responses directed against CFP-10 (median magnitude, 219 SFCs/million PBMCs) or ESAT-6 (median magnitude, 171 SFCs/million PBMCs) (figure 1B). The number of epitopes targeted (per individual) within each antigen tested ranged from 1 to 6 (figure 1C). Overall, summing up the responses to epitopes in all 4 antigens tested, the breadth of responses ranged from 1 to 16 epitopes simultaneously targeted in a single subject, with a median of 2 epitopes targeted (figure 1C).

Identification of immunodominant epitopes in CFP-10 and ESAT-6

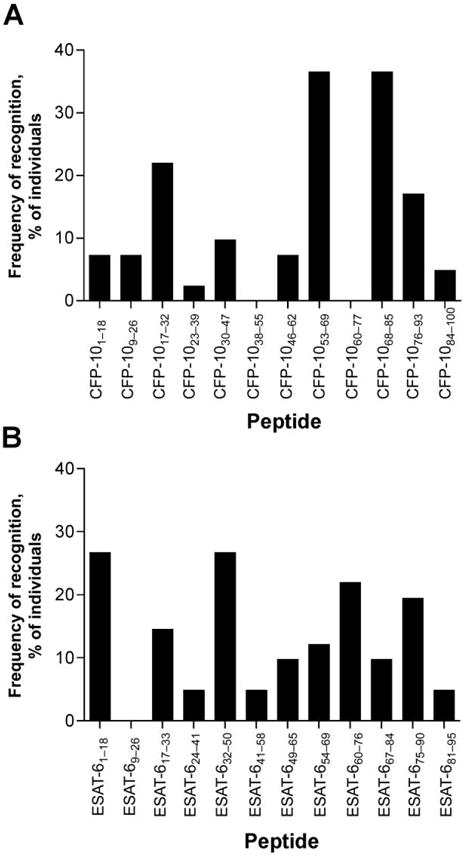

We next analyzed the frequency of recognition of individual overlapping peptides in CFP-10 and ESAT-6, to further map immunodominant epitopes targeted in this population. Ten of 12 overlapping peptides for CFP-10 were recognized by ⩾1 subject, with 2 dominant epitopes (CFP-1053– 69 and CFP-1068–85) each targeted by 37% of subjects (figure 2A). Eleven of 12 ESAT-6 peptides were recognized by ⩾1 subject. The most frequently targeted peptides (ESAT-61–18 and ESAT-632–50) were each recognized by 27% of subjects. Peptides overlapping with the sequences of the 4 most dominant peptides identified in the present study have previously been reported to be frequently recognized by HIV-1-negative subjects in Indian, European, Cambodian, and Middle Eastern cohorts with both latent and active TB [14, 21, 32–35]. Furthermore, ESAT-632–50 and CFP-1053–69 have been described to be immunodominant in HIV-1– positive patients with TB and asymptomatic adults in Zambia [19]. Taken together, these data indicate that the pattern of epitope recognition in these antigens may be similar among ethnically diverse populations of HIV-1-positive and HIV-1-negative individuals.

Figure 2.

Frequency of recognition of individual culture filtrate protein 10 (CFP-10) and early secretory antigen target 6 (ESAT-6) peptides. The percentage of individuals responding to each individual overlapping 18-mer peptide spanning the length of the secreted antigens culture filtrate protein 10 (CFP-10) (A) or ESAT-6 (B) in an ex vivo interferon-γ enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay is shown. Subjects were screened for responses to overlapping 18-mer CFP-10 and ESAT-6 peptides, as described in the figure 1 legend. Forty-one subjects had positive ELISPOT assay responses to either CFP-10 and/or ESAT-6.

Analysis of cytokine production by MTB-specific CD4 and CD8 T cells at the single-cell level

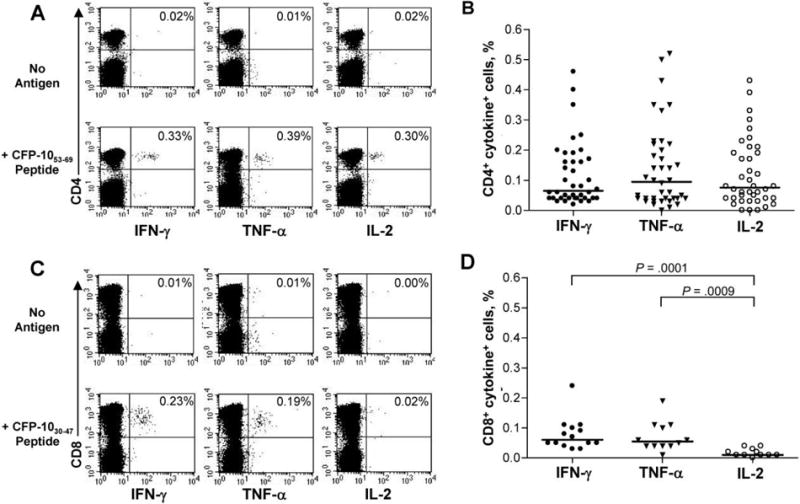

The aforementioned experiments using the IFN-γ ELISPOT assay were designed to identify HIV-1-positive subjects with evidence of latent TB. Because IFN-γ is but one of the cytokines produced by antigen-specific T cells, we next determined the ability of MTB-specific T cells in these subjects to secrete additional cytokines by use of an intracellular cytokine-staining assay to detect IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2 after short-term stimulation with individual ESAT-6 or CFP-10 peptides. Representative data are shown in figure 3A, and composite data (n = 40) are shown in figure 3B. There was no statistical difference in the median frequency of IFN-γ-, TNF-α-, and IL-2-secreting CD4 cells (0.065%, 0.095%, and 0.075% of CD4+ cells, respectively).

Figure 3.

Cytokine production by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB)-specific CD4 and CD8 T cells. A, Representative intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) data for a subject whose cells were stimulated with peptide culture filtrate protein 10 (CFP-10; in this case, CFP-1053–69) and stained intracellulary for interferon (IFN)—γ, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and interleukin (IL)-2. The percentages in the upper right quadrant denote the percentage of CD4+ cytokine-positive cells, with background cytokine production values subtracted. Top, no antigen stimulation; Bottom, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) stimulated for 12 h with CFP-1053–69 peptide. B, Composite data on IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2 production by CD4 T cells in response to individual TB peptides, as tested by ICS (n = 40). For the ICS assay, each subject was tested with individual early secretory antigen testing-6 and CFP-10 peptides that elicited a positive response from that subject in the initial IFN-γ enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) screening assay. Horizontal bars denote the median percentage of CD4+ cytokine-positive cells. C, Representative ICS data for a subject whose cells were stimulated with peptide CFP-1 030–47 and stained intracellularly with IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2. The percentage in the upper right quadrant denotes the percentage of CD8+ cytokine-positive cells, with background cytokine production values subtracted. Top, no antigen stimulation; Bottom, PBMCs stimulated for 12 h with CFP-1030–47 peptide. D, Summary data of IFN-γ (n = 14), TNF-α (n = 12), and IL-2 (n = 11) production by CD8 T cells in response to individual MTB peptides tested by ICS. Horizontal lines denote median percentages of CD8+ cytokine-positive cells.

The majority of MTB-specific T cell responses identified in this cohort were CD4 mediated; however, we were able to identify subjects with detectable MTB-specific CD8 T cell responses. Representative data are shown in figure 3C, with composite data of CD8 responses in 14 subjects shown in figure 3D. The median frequency of MTB-specific cells secreting IFN-γ and TNF-α to an individual ESAT-6 or CFP-10 peptide was 0.060% and 0.055%, respectively, of CD8+ cells. The frequency of IFN-γ- and TNF-α-secreting CD8+ cells was significantly higher than the median frequency of MTB-specific IL-2-secreting CD8+ cells (P = .0001 and P = .0009, respectively) (figure 3D).

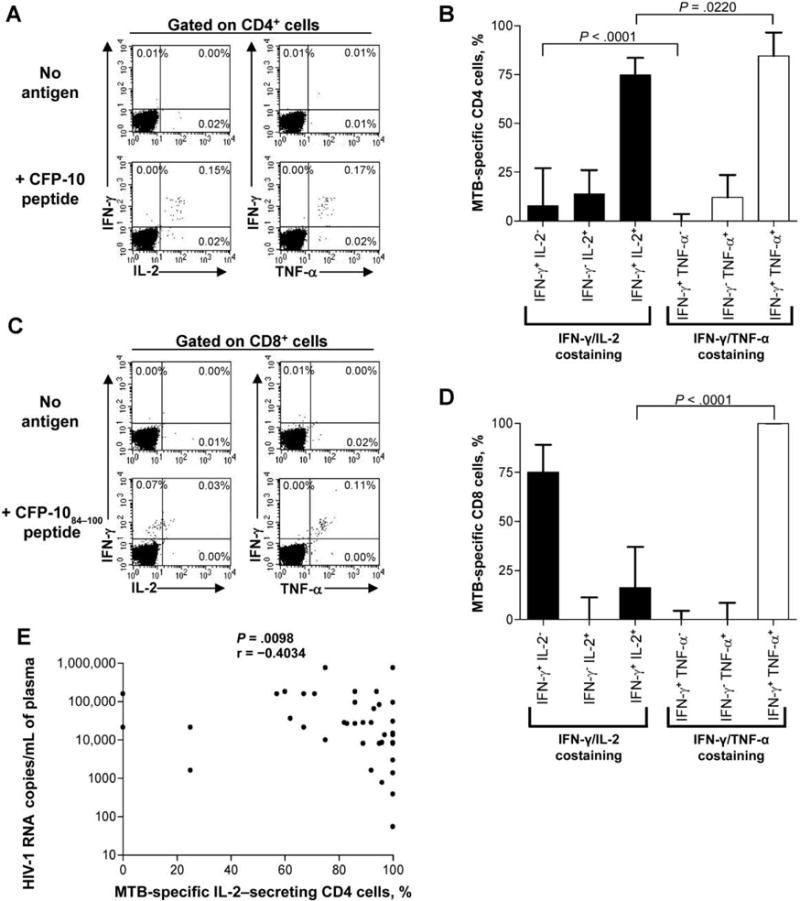

Assessment of production of multiple cytokines by antigen- specific T cells is thought to be an indication of functionality, with loss of cytokine production indicative of impairment of function [36]. To address whether there was evidence of impaired function of MTB-specific T cells in HIV-1-positive individuals, we assessed the frequency of MTB-specific CD4 and CD8 T cells that were able to secrete multiple cytokines simultaneously. Because only a 4-color flow cytometer was available on site in Durban, we performed costaining for IFN-γ/IL-2 and IFN-γ/TNF-α separately. Representative data shown in figure 4A indicated that the majority (⩾75%) of MTB-specific CD4 T cells are polyfunctional: IFN-γ+/IL-2+ and IFN-γ+/TNF-α+. The proportion of INF-y+/TNF-α+ cells was significantly greater than the proportion of IFN-γ+/IL-2+ cells (P = .0220). Although there were virtually no IFN-γ+/TNF-α− cells detectable, a small but significant proportion of MTB-specific CD4 cells that were IFN-γ+/IL-2− was detected (P < .0001).

Figure 4.

Polyfunctional cytokine analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB)-specific CD4 and CD8 T cells. A, Representative Intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) data from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) stimulated with culture filtrate protein 10 (CFP-10; in this case, CFP-1 053–69) peptide and costained with interferon (IFN)—γ/interleukln (IL)—2 and IFN-γ/tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. Cells were gated on CD4+ events, and the percentages denote the percentage of CD4+ cytokine-positive cells in each quadrant. The background cytokine production value has been subtracted from the percentages shown in the lower 2 plots. B, Analysis of the proportion of MTB-specific CD4 cells that are IFN-γ+/IL-2−, IFN-γ−/IL-2+, IFN-γ+/IL-2+, IFN-γ+/TNF-α−, IFN-γ−/TNF-α+, and IFN-γ+/TNF-α+. PBMCs were stimulated with peptide overnight and were costained with either IFN-γ and IL-2 or IFN-γ and TNF-α, as indicated in panel A. The median value and interquartile range for each population are shown (40 subjects had IFN-γ/IL-2 costaining done, and 26 had IFN-γ/TNF-α costaining done). Statistical comparisons were made using the Mann-Whitney test. C, Representative ICS data for MTB-specific CD8 cells stimulated with CFP-1030–47 peptide and costained with IFN-γ/IL-2 and IFN-γ/TNF-α. Cells were gated on CD8+ events, and the percentage of CD8+ cytokine+ cells is shown in the quadrants; the background cytokine production value has been subtracted in the lower 2 plots. D, The proportion of MTB-specific CD8 cells that are IFN-γ+/IL-2−, IFN-γ−/IL-2+, IFN-γ+/IL-2+, IFN-γ+/TNF-α−, IFN-γ−/TNF-α+, and IFN-γ+/TNF-α+. The median value and interquartile range are shown for each population (10 subjects had IFN-γ/IL-2 costaining done, and 9 had IFN-γ/TNF-α costaining done). Statistical comparisons were made using the Mann-Whitney test. E, Inverse correlation between the proportion of MTB-specific IL-2-secreting CD4+ cells and HIV-1 load (P = .0098, by Spearman correlation; n = 40). Results are presented as the percentage of IL-2-positive cells (IFN-γ+/IL-2+ and IFN-γ−/IL-2+) contributing to the total MTB-specific response to individual CFP-10 or early secretory antigen target 6 peptides.

We similarly addressed the polyfunctional cytokine-secreting capacity of MTB-specific CD8 cells by costaining with IFN-γ/IL-2 and IFN-γ/TNF-α (figure 4C), and we found a dominance of IFN-γ+/IL-2− cells and IFN-γ+/TNF-α+ cells (figure 4D). The proportion of TB-specific IFN-γ+/IL-2+ CD8 cells was significantly lower than the proportion of IFN-γ+/TNF-α+ cells (P < .0001) (figure 4D).

Relationship between functionality of MTB-specific T cell responses and parameters of HIV-1 disease progression

To determine the impact of HIV-1 coinfection on the functionality of MTB-specific T cell responses, we next analyzed the relationship between the breadth and magnitude of MTB-specific T cell responses, as determined by the IFN-γ ELISPOT assay, in relation to HIV-1 disease progression, including absolute CD4 cell count and HIV-1 load, and we found no correlations (data not shown). However, analysis of the cytokine costaining data indicated an inverse correlation between the proportion of TB- specific IL-2-secreting (IFN-γ+/IL-2+and IFN-γ−/IL-2+) CD4 cells and the viral load, and a corresponding positive correlation between IFN-γ+/IL-2− CD4 cells and the viralload (P = .0098) (figure 4E). These data indicate that IL-2-secreting MTB- specific CD4 T cells are diminished or have impaired function under conditions of high levels of HIV-1 viremia.

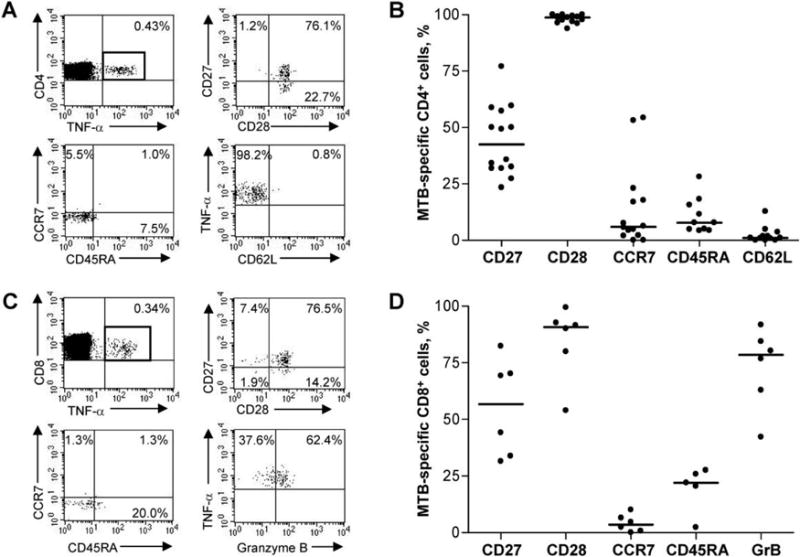

Phenotypic analysis of MTB-specific CD4 and CD8 T cells

Antigen-specific T cells can be classified into different populations of memory and effector cells on the basis of the expression of phenotypic markers associated with maturation status. To determine the phenotypic profile of MTB-specific CD4 T cells associated with latent TB, we used the intracellular cytokine-staining assay to stimulate PBMCs with individual peptides, gating on CD4+ TNF-α+ cells and analyzing expression of the memory markers CD27, CD28, CCR7, CD45RA, and CD62L (figure 5A). MTB-specific CD4 T cells were found to be CCR7loCD45RAloCD62Llo, indicating an effector memory phenotype (n = 14) (figure 5B). The high level of expression of CD28 and the intermediate level of CD27 expression denote an early to intermediate differentiated phenotype.

Figure 5.

Memory phenotypic analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB)-specific CD4 and CD8 T cells. A, Representative MTB-specific CD4 memory phenotyping data for a subject with cells stimulated with peptide culture filtrate protein 10 (CFP-10; in this case, CFP-1053–69). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were gated on CD4+ TNF-α+ cells and analyzed for expression of memory markers CD27, CD28, CD45RA, CCR7, and CD62L, as indicated. The percentages in the flow plots denote the percentage of CD4+ TNF-α+ cells that express the markers indicated. B, Summary data of the memory phenotype of MTB-specific CD4 T cells. PBMCs were stimulated with individual peptides and gated on CD4+ TNF-α+ cells, as shown in panel A (n = 14 subjects). Horizontal lines denote median expression of the indicated marker on MTB-specific CD4 T cells. C, Representative MTB-specific CD8 memory phenotyping data for a subject with cells stimulated with peptide CFP-1030–47. PBMCs were gated on CD8+ TNF-α+ cells and were analyzed for expression of the memory and effector markers CD27, CD28, CD45RA, CCR7, and Granzyme B (GrB; Caltag Laboratories), as indicated. The percentages in the quadrants denote the percentage of CD8+ TNF-α+ cells that express the markers indicated. D, Summary of phenotyping data of MTB-specific CD8 T cells (n = 6 subjects). PBMCs were stimulated with individual MTB peptides and gated on CD8+ TNF-α+ cells, as indicated in panel C. Horizontal lines denote median expression of the indicated marker on MTB-specific CD8 T cells.

Phenotypic analysis of MTB-specific CD8 T cells was performed by stimulating PBMCs with individual peptides and gating on CD8+ TNF-α+ cells for analysis of CD27, CD28, CCR7, CD45RA, and GrB expression (figure 5C). MTB-specific CD8 T cells were found to be CCR7loCD45RAloGrBhi, indicating an effector phenotype (n = 6) (figure 5D). Similar to MTB-specific CD4 cells, MTB-specific CD8 cells demonstrated high levels of expression of CD28 and intermediate levels of expression of CD27, suggesting an early to intermediate differentiated phenotype.

DISCUSSION

This is the first detailed study to characterize MTB-specific CD4 and CD8 T cell responses at the single-cell level in HIV-1-positive adults with latent TB. We used an IFN-γ ELISPOT-based assay using overlapping peptides spanning the RD1 antigens ESAT-6 and CFP-10 to identify HIV-1-positive subjects with latent TB in KwaZulu Natal Province, South Africa, where extensively drug-resistant TB recently has been detected [28]. Our rate of detection of latent TB by use of this RD1-based IFN-γ ELISPOT assay in this cohort was 41%, a rate similar to that reported in a previous study of HIV-1-positive asymptomatic adults in Zambia, in which 9 (43%) of 21 subjects responded to RD1 peptides in an IFN-γ ELISPOT assay [19]. The frequency of latent TB in our study population in South Africa is likely to be even higher than that identified here, because some individuals, particularly those with extremely low CD4 cell counts (<100 cells/μL), may have responses below the level of detection of the ELISPOT assay [20, 24], or they may respond to antigens other than CFP-10 or ESAT-6. Tests for the identification of individuals with latent TB may be useful in predicting who will develop active disease [37], although longitudinal studies are still required to determine the prognostic value of positive responses to CFP-10/ESAT-6 in the development active disease.

Analysis of production of multiple cytokines by antigen-specific T cells is an important measurement of their functionality, and such production is thought to be associated with antigen load [38, 39]. Because of the limitations associated with the use of a 4-color flow cytometer in KwaZulu Natal, we costained cells with either IFN-γ and IL-2 or IFN-γ and TNF-α, and, because a median of ⩾75% of MTB-specific CD4 cells were IFN- γ+/TNF-α+ and IFN-γ+/IL-2+, we can infer that the majority of MTB-specific CD4 cells are polyfunctional and secrete all 3 cytokines simultaneously. However, we found a significantly higher proportion of MTB-specific CD4 cells that were IFN-γ+/TNF-α+, compared with IFN-γ+/IL-2+, suggesting that IL-2 secretion capacity may be lost first (before the loss of TNF-α or IFN-γ). This finding is consistent with murine models of lymphocyte choriomeningitis virus that indicate a hierarchal loss of function of antigen-specific T cells under conditions of persistent antigen stimulation, with loss of IL-2 production preceded by loss of TNF-α synthesis and then, finally, by loss of IFN-γ production [40].

Previous studies involving HIV-1-positive individuals have also indicated loss of IL-2 function by HIV-1-specific CD4 T cells in subjects with progressive disease [41]. The inverse correlation found between the proportion of MTB-specific IL-2-secreting CD4 cells and viral load suggests that MTB-specific CD4 T cells in HIV-1-positive subjects may gradually lose IL-2 secretion capacity as HIV-1 disease progresses. This finding has important implications for MTB pathogenesis, because these responses may already be impaired by the time of reactivation, thus potentially contributing to the rapid course of TB disease often seen in HIV-1-positive individuals. The time of MTB infection is not known in this cohort, and longitudinal studies would need to be performed to determine how the duration of MTB and HIV-1 coinfection affects the IL-2 secretion capacity of MTB-specific CD4 cells. It is important to note that there was no correlation between the total frequency of MTB-specific IFN- γ+, IL-2+, or TNF-α+ CD4 cells and viral load or CD4 count, thus underscoring the need to analyze multiple cytokine functions simultaneously to determine the impact of HIV-1 infection on the functional capacity of MTB-specific T cells.

A previous study indicated reduced frequencies of purified protein derivative-specific IFN-γ+/IL-2+ CD4 T cells in BCG-vaccinated HIV-positive subjects, compared with BCG-vaccinated HIV-negative subjects [42]. In the present study, we were unable to recruit HIV-1-negative individuals with latent TB to directly compare the functional profile of MTB-specific T cell responses in HIV-1-positive and -negative individuals and to determine the relative contributions of these 2 pathogens in the impairment of MTB-specific T cell function. However, a recent study assessing the capacity for IFN-γ and IL-2 secretion by MTB-specific T cells in HIV-1-negative subjects with active TB indicated codominance of IFN-γ+/IL-2− and IFN-γ+/IL-2+ cells, followed by a shift to dominance of IFN-γ+/IL-2+ cells after treatment [39]. Taken together, these data imply that establishment of active disease may further impair MTB-specific T cell function, as evidenced by lack of IL-2 secretion capacity.

Phenotypic analysis of antigen-specific T cells provides important information regarding effector function and maturation status, and it has been well described in human viral infections [43–47] but less so in such bacterial infections as MTB infection. We found the phenotype of MTB-specific CD4 and CD8 cells to be intermediate differentiated effector memory cells, consistent with findings of previous studies of chronically infected mice [48, 49]. Our phenotypic analysis of MTB-specific T cells provides new insights into the development of MTB-specific memory cells in humans. MTB-specific CD8 T cells displayed an unusual phenotype for antigen-specific CD8 T cells in that they exhibited high CD28 expression and intermediate CD27 expression, while they also maintained high GrB expression, which may represent a dysregulated phenotype associated with MTB infection. Antigen-specific CD8 T cells in viral infections are thought to start off as CD27+/CD28+ (early differentiated phenotype) and then lose CD28 expression (CD27+/CD28−; intermediate differentiated phenotype) before losing CD27 expression (CD27−/CD28−; late differentiated phenotype) [44]. However, we found MTB-specific CD8 T cells to be high in CD28 expression and lower in CD27 expression, suggesting that they lose CD27 expression first (before they lose CD28 expression), consistent with the model that has been proposed for antigen-specific CD4 cell differentiation rather than antigen-specific CD8 T cells. There is no accurate test for antigen levels associated with MTB infection in humans, and it is not known whether there is some degree of bacterial replication ongoing in these HIV-1-positive subjects (despite the absence of symptoms of active TB) that may drive these cells to maintain an effector memory phenotype. Furthermore, we did not have access to chest radiographs of these subjects, and it is possible that a proportion of these asymptomatic subjects had undiagnosed, subclinical, active TB.

In conclusion, we found that polyfunctional MTB-specific CD4 and CD8 T cell responses with an effector memory phenotype are readily detectable in the absence of active TB disease in HIV-1-positive subjects. The proportion of IL-2-secreting MTB-specific CD4 cells is inversely associated with HIV-1 viremia, indicating that coinfection with HIV-1 may impair the MTB-specific cellular immune response such that, ultimately, these cells are less capable of containing MTB replication on reactivation, possibly contributing to an accelerated course of disease. Further studies regarding the impact of HIV-1 coinfection on the functional capacity of MTB-specific T cells in persons who do and do not develop active TB are required to identify potential mechanisms contributing to impairment of MTB-specific responses in individuals with chronic HIV-1 infection.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: National Institutes of Health (grant R01 AI067073); Mark and Lisa Schwartz Foundation.

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest: none reported.

Presented in part: 3rd South African AIDS Conference, Durban, South Africa, June 2007 (poster A61).

References

- 1.Corbett EL, Steketee RW, ter Kuile FO, Latif AS, Kamali A, Hayes RJ. HIV-1/AIDS and the control of other infectious diseases in Africa. Lancet. 2002;359:2177–87. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09095-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vynnycky E, Fine PE. The natural history of tuberculosis: the implications of age-dependent risks of disease and the role of reinfection. Epidemiol Infect. 1997;119:183–201. doi: 10.1017/s0950268897007917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selwyn PA, Hartel D, Lewis VA, et al. A prospective study of the risk of tuberculosis among intravenous drug users with human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:545–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198903023200901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sonnenberg P, Murray J, Glynn JR, Shearer S, Kambashi B, Godfrey-Faussett P. HIV-1 and recurrence, relapse, and reinfection of tuberculosis after cure: a cohort study in South African mineworkers. Lancet. 2001;358:1687–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06712-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raviglione MC, Harries AD, Msiska R, Wilkinson D, Nunn P. Tuberculosis and HIV: current status in Africa. AIDS. 1997;11(Suppl B):S115–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper AM, Dalton DK, Stewart TA, Griffin JP, Russell DG, Orme IM. Disseminated tuberculosis in interferon gamma gene-disrupted mice. J Exp Med. 1993;178:2243–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flynn JL, Chan J, Triebold KJ, Dalton DK, Stewart TA, Bloom BR. An essential role for interferon gamma in resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J Exp Med. 1993;178:2249–54. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jouanguy E, Altare F, Lamhamedi S, et al. Interferon-γ-receptor deficiency in an infant with fatal bacille Calmette-Guérin infection. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1956–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612263352604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jouanguy E, Lamhamedi-Cherradi S, Lammas D, et al. A human IF- NGR1 small deletion hotspot associated with dominant susceptibilityto mycobacterial infection. Nat Genet. 1999;21:370–8. doi: 10.1038/7701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geluk A, van Meijgaarden KE, Franken KL, et al. Identification of major epitopes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis AG85B that are recognized by HLA-A*0201-restricted CD8+ T cells in HLA-transgenic mice and humans. J Immunol. 2000;165:6463–71. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.11.6463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith SM, Brookes R, Klein MR, et al. Human CD8+ CTL specific for the mycobacterial major secreted antigen 85A. J Immunol. 2000;165:7088–95. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.7088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lalvani A, Brookes R, Wilkinson RJ, et al. Human cytolytic and interferon γ-secreting CD8+ T lymphocytes specific for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:270–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valle MT, Megiovanni AM, Merlo A, et al. Epitope focus, clonal composition and Th1 phenotype of the human CD4 response to the secre- torymycobacterial antigenAg85. Clin Exp Immunol. 2001;123:226–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01450.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pathan AA, Wilkinson KA, Klenerman P, et al. Direct ex vivo analysis of antigen-specific IFN-γ-secreting CD4 T cells in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected individuals: associations with clinical disease state and effect of treatment. J Immunol. 2001;167:5217–25. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.5217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pathan AA, Wilkinson KA, Wilkinson RJ, et al. High frequencies of circulating IFN-γ-secreting CD8 cytotoxic T cells specific for a novel MHC class I-restricted Mycobacterium tuberculosis epitope in M. tuberculosis-infected subjects without disease. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:2713–21. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200009)30:9<2713::AID-IMMU2713>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ravn P, Demissie A, Eguale T, et al. Human T cell responses to the ESAT-6 antigen from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:637–45. doi: 10.1086/314640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pai M, Riley LW, Colford JM., Jr Interferon-γ assays in the immunodiagnosis of tuberculosis: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4:761–6. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01206-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Behr MA, Wilson MA, Gill WP, et al. Comparative genomics of BCG vaccines by whole-genome DNA microarray. Science. 1999;284:1520–3. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5419.1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chapman AL, Munkanta M, Wilkinson KA, et al. Rapid detection of active and latent tuberculosis infection in HIV-positive individuals by enumeration of Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific T cells. AIDS. 2002;16:2285–93. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200211220-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dheda K, Lalvani A, Miller RF, et al. Performance of a T-cell-based diagnostic test for tuberculosis infection in HIV-infected individuals is independent of CD4 cell count. AIDS. 2005;19:2038–41. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000191923.08938.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lalvani A, Nagvenkar P, Udwadia Z, et al. Enumeration of T cells specific for RD1-encoded antigens suggests a high prevalence of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in healthy urban Indians. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:469–77. doi: 10.1086/318081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luetkemeyer AF, Charlebois ED, Flores LL, et al. Comparison of an interferon-γ release assay with tuberculin skin testing in HIV-infected individuals. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:737–42. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200608-1088OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rangaka MX, Wilkinson KA, Seldon R, et al. Effect of HIV-1 infection on T-cell-based and skin test detection of tuberculosis infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:514–20. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200610-1439OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawn SD, Bangani N, Vogt M, et al. Utility of interferon-γ ELISPOT assay responses in highly tuberculosis-exposed patients with advanced HIV infection in South Africa. BMC Infect Dis. 2007;7:99. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-7-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liebeschuetz S, Bamber S, Ewer K, Deeks J, Pathan AA, Lalvani A. Diagnosis of tuberculosis in South African children with a T-cell-based assay: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2004;364:2196–203. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17592-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scarpellini P, Tasca S, Galli L, Beretta A, Lazzarin A, Fortis C. Selected pool of peptides from ESAT-6 and CFP-10 proteins for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:3469–74. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.8.3469-3474.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang M, Gong J, Iyer DV, Jones BE, Modlin RL, Barnes PF. T cell cytokine responses in persons with tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:2435–42. doi: 10.1172/JCI117611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gandhi NR, Moll A, Sturm AW, et al. Extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis as a cause of death in patients co-infected with tuberculosis and HIV in a rural area of South Africa. Lancet. 2006;368:1575–80. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69573-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Addo MM, Yu XG, Rathod A, et al. Comprehensive epitope analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-specific T-cell responses directed against the entire expressed HIV-1 genome demonstrate broadly directed responses, but no correlation to viral load. J Virol. 2003;77:2081–92. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.3.2081-2092.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hervas-Stubbs S, Majlessi L, Simsova M, et al. High frequency of CD4+ T cells specific for the TB10.4 protein correlates with protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Infect Immun. 2006;74:3396–407. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02086-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skjot RL, Oettinger T, Rosenkrands I, et al. Comparative evaluation of low-molecular-mass proteins from Mycobacterium tuberculosis identifies members of the ESAT-6 familyas immunodominant T-cell antigens. Infect Immun. 2000;68:214–20. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.214-220.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shams H, Klucar P, Weis SE, et al. Characterization of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis peptide that is recognized by human CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the context of multiple HLA alleles. J Immunol. 2004;173:1966–77. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ulrichs T, Munk ME, Mollenkopf H, et al. Differential T cell responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis ESAT6 in tuberculosis patients and healthy donors. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:3949–58. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199812)28:12<3949::AID-IMMU3949>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Delgado JC, Baena A, Thim S, Goldfeld AE. Aspartic acid homozygosity at codon 57 of HLA-DQ β is associated with susceptibility to pulmonary tuberculosis in Cambodia. J Immunol. 2006;176:1090–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mustafa AS, Shaban FA, Al-Attiyah R, et al. Human Th1 cell lines recognize the Mycobacterium tuberculosis ESAT-6 antigen and its peptides in association with frequently expressed HLA class II molecules. Scand J Immunol. 2003;57:125–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2003.01204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kannanganat S, Ibegbu C, Chennareddi L, Robinson HL, Amara RR. Multiple-cytokine-producing antiviral CD4 T cells are functionally superior to single-cytokine-producing cells. J Virol. 2007;81:8468–76. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00228-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andersen P, Doherty TM, Pai M, Weldingh K. The prognosis of latent tuberculosis: can disease be predicted? Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:175–82. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harari A, Vallelian F, Meylan PR, Pantaleo G. Functional heterogeneity of memory CD4 T cell responses in different conditions of antigen exposure and persistence. J Immunol. 2005;174:1037–45. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Millington KA, Innes JA, Hackforth S, et al. Dynamic relationship between IFN-γ and IL-2 profile of Mycobacterium tuberculosis–specific T cells and antigen load. J Immunol. 2007;178:5217–26. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.5217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wherry EJ, Blattman JN, Murali-Krishna K, van der Most R, Ahmed R. Viral persistence alters CD8 T-cell immunodominance and tissue distribution and results in distinct stages of functional impairment. J Virol. 2003;77:4911–27. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.8.4911-4927.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Day CL, Walker BD. Progress in defining CD4 helper cell responses in chronic viral infections. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1773–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sutherland R, Yang H, Scriba TJ, et al. Impaired IFN-γ-secreting capacity in mycobacterial antigen-specific CD4 T cells during chronic HIV-1 infection despite long-term HAART. AIDS. 2006;20:821–9. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000218545.31716.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amyes E, McMichael AJ, Callan MF. Human CD4+ T cells are predominantly distributed among six phenotypically and functionally distinct subsets. J Immunol. 2005;175:5765–73. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.5765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Appay V, Dunbar PR, Callan M, et al. Memory CD8+ T cells vary in differentiation phenotype in different persistent virus infections. Nat Med. 2002;8:379–85. doi: 10.1038/nm0402-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yue FY, Kovacs CM, Dimayuga RC, Parks P, Ostrowski MA. HIV-1- specific memory CD4+ T cells are phenotypically less mature than cytomegalovirus-specific memory CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2004;172:2476–86. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.4.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Champagne P, Ogg GS, King AS, et al. Skewed maturation of memory HIV-specific CD8 Tlymphocytes. Nature. 2001;410:106–11. doi: 10.1038/35065118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lucas M, Day CL, Wyer JR, et al. Ex vivo phenotype and frequency of influenza virus-specific CD4 memory T cells. J Virol. 2004;78:7284–7. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.13.7284-7287.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kamath A, Woodworth JS, Behar SM. Antigen-specific CD8+ T cells and the development of central memory during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J Immunol. 2006;177:6361–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Junqueira-Kipnis AP, Turner J, Gonzalez-Juarrero M, Turner OC, Orme IM. Stable T-cell population expressing an effector cell surface phenotype in the lungs of mice chronically infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2004;72:570–5. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.1.570-575.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]