Abstract

Human islet amyloid polypeptide (hIAPP) aggregation is associated with β-cell dysfunction and death in type 2 diabetes (T2D). we aimed to determine whether in vivo treatment with chemical chaperone 4-phenylbutyrate (PBA) ameliorates hIAPP-induced β-cell dysfunction and islet amyloid formation. Oral administration of PBA in hIAPP transgenic (hIAPP Tg) mice expressing hIAPP in pancreatic β cells counteracted impaired glucose homeostasis and restored glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Moreover, PBA treatment almost completely prevented the transcriptomic alterations observed in hIAPP Tg islets, including the induction of genes related to inflammation. PBA also increased β-cell viability and improved insulin secretion in hIAPP Tg islets cultured under glucolipotoxic conditions. Strikingly, PBA not only prevented but even reversed islet amyloid deposition, pointing to a direct effect of PBA on hIAPP. This was supported by in silico calculations uncovering potential binding sites of PBA to monomeric, dimeric, and pentameric fibrillar structures, and by in vitro assays showing inhibition of hIAPP fibril formation by PBA. Collectively, these results uncover a novel beneficial effect of PBA on glucose homeostasis by restoring β-cell function and preventing amyloid formation in mice expressing hIAPP in β cells, highlighting the therapeutic potential of PBA for the treatment of T2D.—Montane, J., de Pablo, S., Castaño, C., Rodríguez-Comas, J., Cadavez, L., Obach, M., Visa, M., Alcarraz-Vizán, G., Sanchez-Martinez, M., Nonell-Canals, A., Parrizas, M., Servitja, J.-M., Novials, A. Amyloid-induced β-cell dysfunction and islet inflammation are ameliorated by 4-phenylbutyrate (PBA) treatment.

Keywords: diabetes, IAPP, insulin, pancreatic islets

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) results from peripheral insulin resistance coupled with a failure of pancreatic β cells to secrete sufficient insulin to maintain normoglycemia. Islet amyloid deposits have been associated with the decreased β-cell area and increased β-cell apoptosis observed in patients with T2D (1, 2). Amyloid deposits result from the aggregation of islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP), its main peptide constituent. IAPP is a hormone synthesized and secreted by pancreatic β cells upon glucose stimulation, together with insulin. The central region of human IAPP (hIAPP) is formed by hydrophobic amino acids, which are thought to be responsible for its aggregation (3). Conversely, rodent IAPP lacks these amyloidogenic residues and does not aggregate.

Previous studies have demonstrated that endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress plays a dominant role in the development of T2D (4). In this regard, hIAPP overexpression induces ER stress–mediated β-cell apoptosis and leads to defective insulin and IAPP secretion in response to glucose in mouse islets and β-cell lines (5–8). Thus, strategies aimed at counteracting hIAPP misfolding and deposition could be of benefit for T2D treatment.

Chemical chaperones, such as tauroursodeoxycholic acid and 4-phenylbutyrate (PBA), have been shown to alleviate ER stress and enhance insulin action in peripheral tissues and restore glucose homeostasis in a mouse model of T2D (4). Moreover, these chemical chaperones have already been tested in human studies, demonstrating its capacity for increasing insulin sensitivity, preventing lipotoxicity, and increasing insulin secretion (9–11). Furthermore, treatment with these chemical chaperones and with molecular chaperones such as binding immunoglobulin protein (BiP) and protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) ameliorates β-cell dysfunction associated with hIAPP overexpression in a rat pancreatic cell line (12). In this context, we have also demonstrated that PDI ameliorates β-cell dysfunction and cell apoptosis in hIAPP transgenic (hIAPP Tg) mouse islets (13). Likewise, a decrease in the aggregation of hIAPP can potentially reduce its damaging effects. Several compounds have been shown to prevent amyloid formation in both T2D and Alzheimer disease (AD) (14, 15). In particular, PBA treatment was able to attenuate amyloid plaque formation and facilitate cognitive memory performance in AD Tg mice (14). Because amyloid formation in pancreatic islets and in the brain share common pathogenic pathways (16), we hypothesized that PBA may have a similar effect in a mouse model of T2D characterized by islet hIAPP overexpression.

We demonstrated that in vivo administration of PBA restores glucose homeostasis and prevents islet amyloid deposition in mice overexpressing hIAPP in pancreatic islets. In addition, we found that PBA prevents and reverses islet amyloid aggregation when islets are exposed to high glucose levels. Finally, in silico analyses reveal a direct interaction of PBA with different forms of hIAPP oligomerization. These findings will contribute toward developing new therapies for preventing the loss of β-cell mass associated with amyloid formation in T2D.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tg mice and in vivo treatment

Heterozygous male Tg mice with β-cell-specific expression of hIAPP in a Friend leukemia virus B (FVB) background (FVB/N-Tg(Ins2-IAPP)RHFSoel/J) (17) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Non-Tg littermates were used as controls. Mice aged 8 wk were treated with 1 g/kg/d of PBA dissolved in drinking water for 12 wk or left untreated, as described in refs. 4, 14, and 18. All animals were housed in the animal facility of the University of Barcelona, in a 12-h light/dark cycle, with free access to food and water. Animal studies were performed in compliance with current Spanish and European legislation. Studies were approved by the University of Barcelona Ethics Committee (ID: 317/13).

Glucose and insulin tolerance tests

Glucose tolerance tests were performed by intraperitoneal injection of glucose (2 g/kg body weight) in mice unfed for 8 h. For insulin tolerance tests, 0.5 U/kg human insulin (Novo Nordisk, Clayton, NC, USA) was intraperitoneally injected. Plasma insulin levels were measured using an insulin ELISA kit (Mercodia, Uppsala, Sweden).

RNA isolation and real-time PCR

Total RNA from pancreatic islets was extracted with RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA). Reverse transcription was performed with 0.5 to 1 µg of total RNA using Superscript III (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Real-time PCR was carried out using SYBR Green. Quantitative PCR products were verified through dissociation curve analysis by SDS software (Roche Applied Sciences, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Expression levels were normalized to hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase (Hprt) and TATA-box-binding protein 1 (Tbp1). Primer sets are shown in Supplemental Table 1.

Global gene expression profiling

RNA from mouse pancreatic islets was hybridized onto GeneChip HT MG-430 PM arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Expression data were normalized with RMA, and the Limma package available from Bioconductor (http://www.bioconductor.org) was used for statistical analysis to identify differentially expressed genes using a multiple test–adjusted P value (false detection rate) of P < 0.05, as previously described (19). Data were deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) under accession number GSE84423. The Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID ) Functional Annotation Tool (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov) was used to identify enriched functional categories among differentially expressed genes.

Mouse islet isolation and culture

Pancreatic islets were isolated by collagenase digestion (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and a density gradient using Histopaque (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) as previously described (20). Handpicked islets were allowed to recover overnight in RPMI 1640 (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (v/v), 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Palmitate (400 μM; Sigma-Aldrich) combined with 16.7 mM glucose was added to the islets by conjugating with 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich). PBA (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in PBS and used at 2.5 mM. IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA or anakinra; PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) was dissolved in water and used at 4 µg/ml. Adenoviral transduction for PDI overexpression was performed as previously described (13). For islet amyloid formation experiments, islets were incubated at 16.7 mM glucose for 7 d.

Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion assays

Groups of 10 islets were preincubated in triplicate with Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate buffer containing 140 mM NaCl, 4.5 mM KCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, and supplemented with 0.1% bovine serum albumin and 2.8 mM glucose for 30 min, followed by incubation with 2.8 or 16.7 mM glucose for 1 h at 37°C. Supernatant was recovered, and islets were lysed in 200 μl of acid–ethanol solution to measure insulin content. Insulin levels in supernatant and lysates were determined by insulin ELISA kit (Mercodia).

Immunohistochemistry

Islets were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 min. After blocking with PBS in 10% fetal bovine serum and 0.5% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich), islets were incubated with polyclonal guinea pig anti-insulin (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) and rabbit anti–caspase 3 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) antibodies, followed by secondary incubation with Alexa Fluor 555 conjugated goat anti–guinea pig IgG (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 594 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA). Islets were counterstained with DAPI (Molecular Probes) and mounted with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). TUNEL staining was performed using the DeadEnd Fluorometric TUNEL system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). For double insulin and amyloid (thioflavin S) staining, sections with isolated pancreatic islets embedded in 2% agarose were immunostained for insulin as described above. Sections were then incubated in 0.5% thioflavin S (Sigma-Aldrich) solution for 2 min and rinsed twice with 70% ethanol. Fluorescent slides were viewed using a Leica TCS SPE confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA), and images were acquired using Leica LAS Image Analysis software.

Computational studies

Receptors were modeled from available crystal structures [PDB IDs 2KB8 (21), 2L86 (22)] and 3-dimensional structures provided by M. T. Bowers (23) and R. Tycko (24). The ligands’ 3-dimensional structures were obtained from ChemSpider (http://www.chemspider.com/). Blind docking calculations, including the setup, were carried out using Kin (25). Molecular dynamic simulations were performed using NAMD (26), in explicit solvent using the TIP3P (27) water model with the imposition of periodic boundary conditions via a cubic box, at NPT (temperature and pressure were kept at 300 K and 1 atm) conditions with full Particle MeshEwald–based electrostatics, with 2 fs time step. The Ambers99SB-ILDN (28) parameter was set for the receptors and the GAFF force field (29) for the ligands. Receptors and ligands parameters were obtained using the leap module of AmberTools (30) and ACPYPE (31), respectively. Molecular mechanics/generalized born surface area (MM/GBSA) calculations were performed using the MMPBSA.py (32) algorithm. All graphical representations derived were prepared using VMD 1.9.1 (33).

Thioflavin T fluorescent assays

A stock solution (500 mM) of hIAPP and rat IAPP (rIAPP) was diluted in a 25 mM Tris-HCl plus 100 mM NaCl buffer at pH 8.0. PBA was added to solutions of hIAPP and rIAPP in a Tris buffer containing 65 µM of thioflavin T at pH 7.3 for a final concentration of 10 µM of each peptide, as previously described (34). Fluorescence was measured using an Infinite F200 fluorescence spectrophotometer (Tecan, Zurich, Switzerland). The excitation wavelength used was 445 nm, and the emission wavelength was 485 nm.

Transmission electron microscopy

For transmission electron microscopy (TEM) studies, aliquots of 4 µl of 10 µM hIAPP with or without 2.5 mM of PBA were placed on a carbon-coated 200-mesh copper grid and negatively stained with saturated uranyl acetate. Images were collected from 2 independent prepared samples. Ultrastructural analyses were performed in a Jeol 1010 electron microscope (Jeol Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at 80 kV, and images were acquired with a BioScan 972 camera (Gatan, Munich, Germany).

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance between 2 groups was determined by a 2-tailed Student’s t test, and differences among more than 2 groups were carried out by ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s post hoc test. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05. Data are presented as means ± sem for the number of experiments indicated.

RESULTS

PBA administration restores glucose metabolism in hIAPP Tg mice

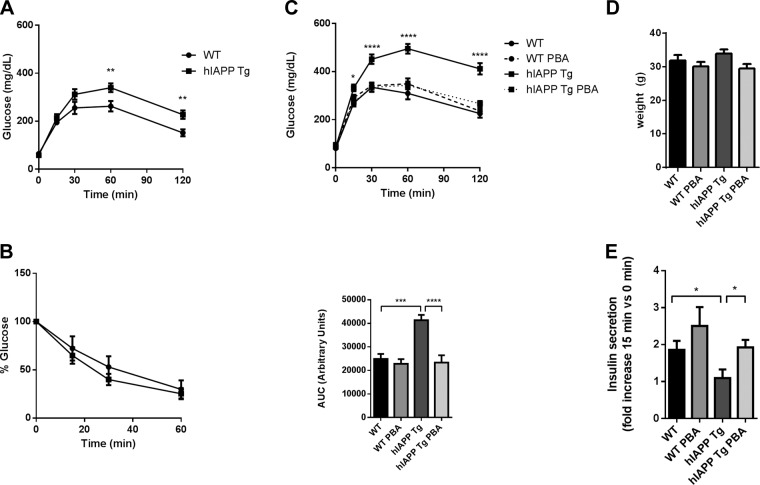

In order to determine the effect of the chemical chaperone PBA in a model of islet hIAPP overexpression, we used hIAPP Tg mice, which overexpress hIAPP in pancreatic β cells in an FVB background and exhibit a marked β-cell dysfunction and glucose intolerance. PBA was administered in drinking water to 8-wk-old hIAPP Tg and wild-type (WT) male mice for 12 wk. Just before the initiation of PBA treatment, intraperitoneal glucose tolerance tests revealed that hIAPP Tg mice already exhibited glucose intolerance (Fig. 1A). An insulin tolerance test demonstrated that hIAPP Tg mice did not exhibit insulin resistance (Fig. 1B), and glucose intolerance could therefore be mainly attributed to islet dysfunction. After 12 wk of treatment, when mice were 20 wk old, glucose intolerance in nontreated control hIAPP Tg mice was further exacerbated. Strikingly, PBA administration completely restored glucose homeostasis in hIAPP Tg mice (Fig. 1C), with no effect on body weight (Fig. 1D) and fasting glucose levels (Fig. 1C). Further, PBA restored glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in hIAPP Tg mice, indicating that PBA prevented β-cell dysfunction in these mice (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1.

PBA treatment prevents glucose intolerance in hIAPP Tg mice. A, B) Glucose (A) and insulin (B) tolerance tests in 8-wk-old WT and hIAPP Tg male mice before initiation of PBA treatment. C) Glucose tolerance tests after 12 wk of oral administration of PBA. Glycemia values at glucose administration and respective areas under curve (AUC) are shown. D) Body weight of mice after 12 wk of PBA treatment. E) Fold increase of plasma insulin levels at 15 min after glucose injection with respect to initial values. A, B, E) n = 6–8 mice per group. C, D) n = 11–13 mice per group. Results are presented as means ± sem. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001(by ANOVA).

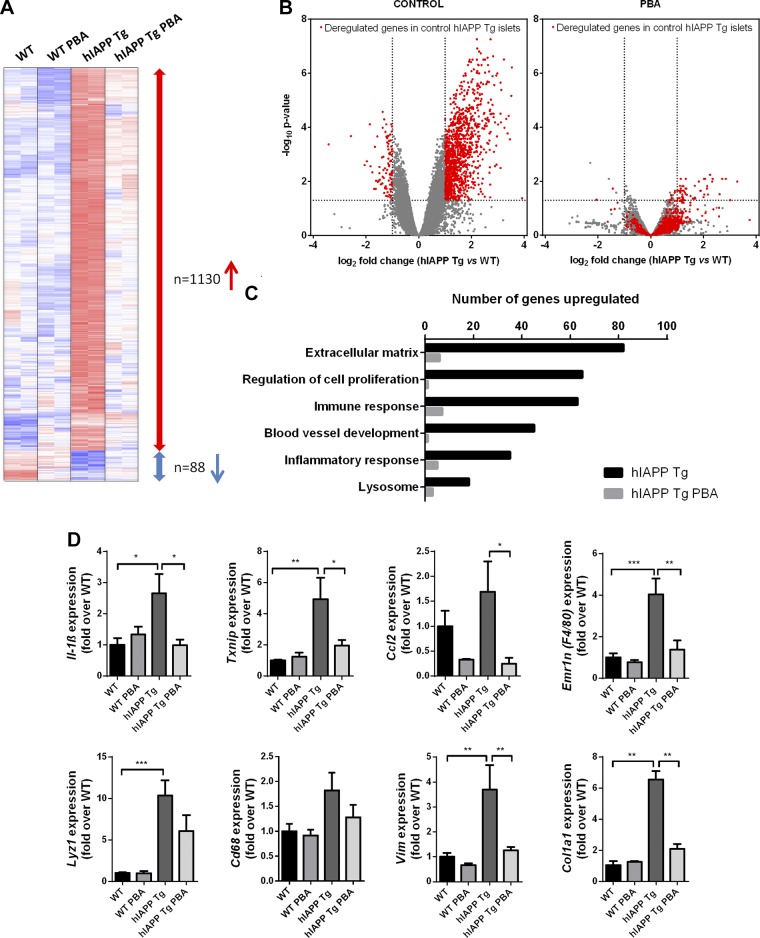

PBA treatment restores the islet transcriptome in hIAPP Tg mice

Global gene expression analyses revealed that the transcriptional profile of islets from 20-wk-old hIAPP Tg mice was profoundly altered, with over 1000 genes being up-regulated more than 2-fold compared to WT islets (Fig. 2A, B). The number of genes that were down-regulated was much lower (n = 88). Gene ontology analysis revealed an enrichment of categories related to extracellular matrix, vascularization, inflammation, and immune response among the up-regulated genes (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

PBA treatment globally normalizes islet transcriptome in hIAPP Tg mice. WT and hIAPP Tg mice were treated with PBA for 12 wk or left untreated. Islets were isolated, and RNA was extracted for global gene expression analysis. A) Heat maps depicting expression levels of genes deregulated in hIAPP Tg mice (blue, lowest expression; red, highest expression). Red and blue arrows show up-regulated and down-regulated genes (>2 fold) in hIAPP Tg mice, respectively. n = 2 mice per group. B) Volcano plots of global gene expression changes in control (left) or PBA-treated (right) hIAPP Tg mice with respect to WT littermates. Dashed lines represent threshold for fold change (±2) and false detection rate (≤0.05). Deregulated genes in hIAPP Tg islets (red spots) are globally normalized by PBA treatment. C) Number of genes belonging to different gene ontology categories that are up-regulated in hIAPP Tg (black) and hIAPP Tg PBA (gray) compared to WT mice. D) qPCR analysis of mRNA expression levels of representative genes related to inflammation and extracellular matrix were normalized to Tbp1 and Hprt. Results are expressed as means ± sem of 4–5 mice per group from 2 independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.00, ****P < 0.0001 (by ANOVA).

Strikingly, and in line with the restoration of glucose homeostasis, PBA treatment normalized the expression of about 90% of deregulated genes in hIAPP Tg islets (Fig. 2A–C). PBA treatment affected all the functional categories that are affected in hIAPP Tg islets (Fig. 2D), including those related to inflammation and extracellular matrix. This is illustrated by the complete or partial reduction by PBA of the induction of inflammatory genes such as Il-1β, Txnip, and Ccl2. Furthermore, PBA also abrogated the increased expression of several macrophage cell markers, such as Emr1 (encoding F4/80) and Lyz1. The macrophage marker CD68 showed subtle changes in gene expression. Furthermore, PBA administration also completely prevented the up-regulation of extracellular matrix genes such as the collagen gene Col1a1. Notably, overexpression of hIAPP in pancreatic islets was not associated with an increase in the mRNA expression levels of several ER stress markers, such as Atf6, Chop, Bip, or Atf3 (Supplemental Fig. 1). Collectively, these results indicate that hIAPP Tg islets display a profound inflammatory response in the absence of ER stress induction, and that PBA is able to almost completely abolish this response.

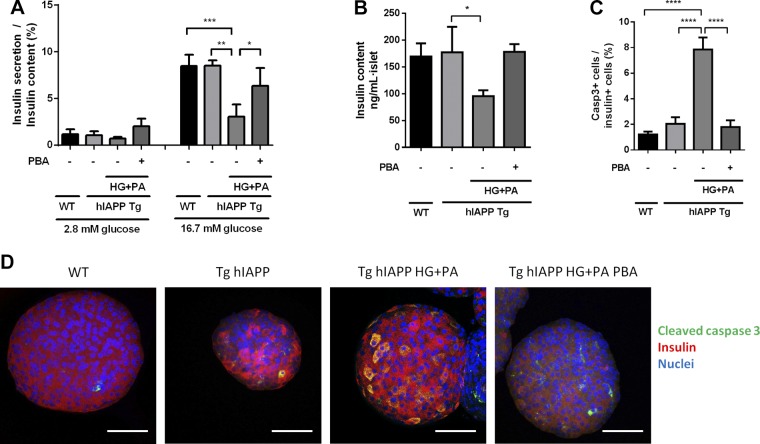

PBA treatment restores β-cell function and decreases β-cell death in hIAPP Tg islets under glucolipotoxic conditions

Function and survival of β-cells are markedly affected when hIAPP Tg islets are cultured under glucolipotoxic conditions (13). Thus, we next evaluated whether PBA was able to prevent the detrimental effects of high glucose and palmitate (HG + PA) in hIAPP Tg and WT islets. Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion assays revealed that β-cell function was not affected in hIAPP Tg islets under nonglucolipotoxic conditions (Fig. 3A). In contrast, HG + PA exposure diminished glucose-stimulated insulin release in hIAPP Tg islets. Remarkably, PBA prevented the detrimental glucolipotoxic effects in hIAPP Tg islets, restoring insulin secretion and insulin content to control levels (Fig. 3A, B). Additionally, PBA completely abolished the activation of caspase 3 in β cells in hIAPP Tg islets cultured under glucolipotoxic conditions (Fig. 3C, D). Overall, these results indicate that PBA is able to recover insulin secretion, maintain insulin content, and prevent apoptosis in hIAPP-expressing pancreatic islets under glucolipotoxic conditions.

Figure 3.

PBA treatment prevents HG + PA–induced β-cell dysfunction and death in hIAPP Tg islets. WT and hIAPP Tg islets were left untreated or were treated with high glucose (16.7 mM) and 400 μM palmitate (HG + PA) for 24 h in absence or presence of 2.5 mM PBA. A) Insulin secretion was tested at 2.8 and 16.7 mM glucose. Results are expressed as means ± sem from 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 relative to hIAPP Tg HG + PA control. B) Insulin content (ng/ml per islet) of WT or hIAPP Tg islets left untreated or treated with HG + PA. *P < 0.05 relative to hIAPP Tg control. C) Quantification of cleaved caspase 3–positive cells relative to insulin-positive cells. Results are expressed as means ± sem from at least 20 islets obtained from 3 mice per group. D) Representative images of in toto immunostaining of insulin (red), cleaved caspase 3 (green), and nuclei (blue). Scale bars, 50 µm. ****P < 0.0001 relative to hIAPP Tg HG + PA control (by ANOVA).

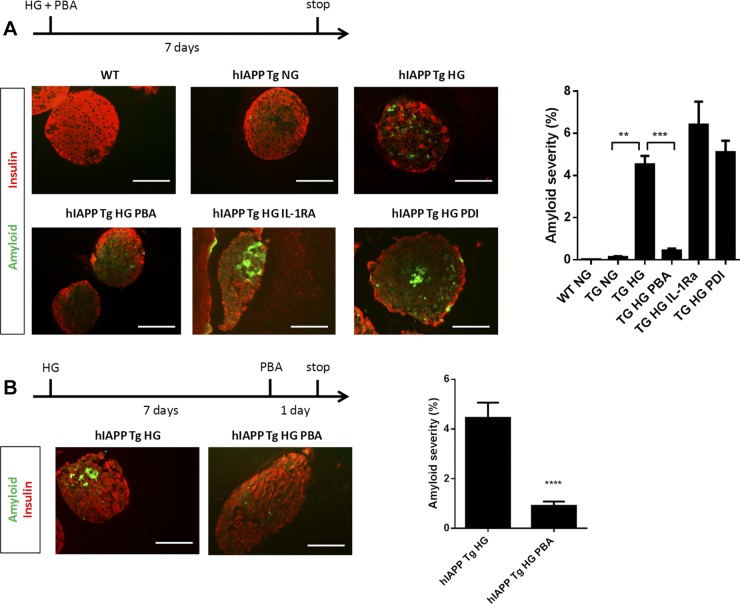

Chaperone treatment prevents and reverses amyloid formation in hIAPP Tg islets

Although hIAPP Tg mice show a clear glucose intolerance phenotype, amyloid deposits are not detectable until the animals reach an advanced age and are fed a high-fat diet (17). In contrast, isolated hIAPP Tg islets form extracellular amyloid deposits after 7 d of culture with high glucose (35). To study the effects of PBA treatment on amyloid deposition, we exploited this rapid amyloid deposition observed in islets cultured under high glucose concentrations (16.7 mM glucose). Indeed, in hIAPP Tg islets exposed to high glucose for 7 d, amyloid was formed throughout the islets, engaging 4.52 ± 0.4% of the insulin-positive area (Fig. 4A). Remarkably, PBA addition markedly reduced islet amyloid severity (0.43 ± 0.08%). Interestingly, overexpression of PDI in islets and treatment with the IL-1RA did not reduce amyloid formation, highlighting an additional beneficial effect of PBA with respect to other agents that have been shown to protect hIAPP Tg islets.

Figure 4.

PBA treatment prevents and reverses islet amyloid deposits in hIAPP Tg islets. A) hIAPP Tg islets were left untreated, were treated with PBA or IL-1RA, or were transduced with adenovirus encoding PDI and cultured in normal-glucose (NG, 11.1 mM glucose) or high-glucose (HG, 16.7 mM glucose) conditions for 7 d. WT islets were used as controls. Insulin (red) and amyloid (green) were determined by immunohistochemistry and thioflavin S staining (representative images at left). Amyloid severity (amyloid area/insulin area × 100) is shown at right. Results are expressed as means ± sem from at least 30 islets in 2 independent experiments. B) hIAPP Tg islets were incubated for 7 d at HG conditions, then left untreated or treated with 2.5 mM PBA for 24 h. Representative images (left) and quantification (right) of insulin-positive cells (red) and amyloid (green) are shown. Scale bars, 50 µm. Results are expressed as means ± sem from at least 30 islets from 2 independent experiments. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 relative to hIAPP Tg HG control (by ANOVA).

Next, we explored whether PBA also had an effect in hIAPP Tg islets after a 1-wk exposure to high-glucose conditions, when amyloid deposits are already formed. Strikingly, the addition of PBA for only 24 h reversed amyloid deposition (Fig. 4B), decreasing amyloid severity from 4.5 ± 0.6 to 0.9 ± 0.1%. This result pointed to the possibility that PBA may directly interact with hIAPP and avoid, and even reverse, its aggregation.

Computational validation of PBA binding to hIAPP

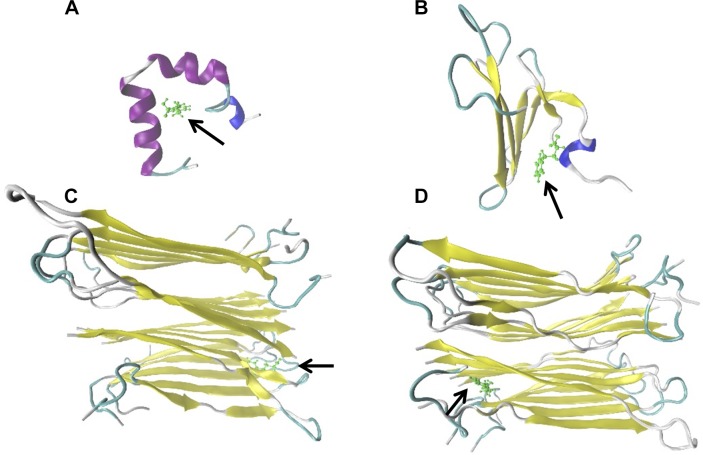

In order to determine whether PBA may directly interact with hIAPP, we performed an in silico analysis to identify potential interactions between hIAPP and PBA crystal structures representing different states of the conformational landscape (monomers, dimers, and oligomers) of hIAPP (Supplemental Fig. 2A). Results were replicated against resveratrol and epigallocatechin gallate (Supplemental Fig. 2B), natural polyphenols that have been shown to act as amyloid inhibitors (36, 37), to validate our computational models. Interestingly, PBA showed similar results to those of resveratrol or epigallocatechin gallate. In general, the best cavities (protein regions able to host bound ligands) were shared by all 3 molecules (Supplemental Table 2). Next, we selected the best complexes on the basis of docking interaction energies (Supplemental Table 2), and we checked their stability via molecular dynamic simulations and MM/GBSA calculations. Our results confirmed, in accordance with the docking calculations, that PBA may bind not only to monomeric and dimeric structures, but also to pentameric fibrillar structures with even higher stability (Fig. 5 and Table 1). Thus, our computational analyses revealed that PBA may act as a fibril-formation inhibitor by binding intermediate structures from monomers to fibrils with a growing complexity.

Figure 5.

Potential binding of PBA to hIAPP monomeric, dimeric, and pentameric structures. Representative images of PBA-hIAPP complexes with best identified binding sites (based on MM/GBSA energies summarized in Table 1) of PBA (green, arrows) on hIAPP 1−37 protein (colored based on adopted secondary structure) in monomer 2 (A), dimer 2 (B), oligomer 1 (C), and oligomer 2 systems (D).

TABLE 1.

MM/GBSA energies of best PBA-hIAPP complexes based on docking interaction energies

| Molecule | Cavity | MM/GBSA (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| Monomer 1 | 0 | −9.3485 |

| Monomer 2 | 0 | −15.9626 |

| Monomer 4 | 0 | −9.4133 |

| 1 | −7.3049 | |

| Dimer 1 | 0 | −18.5082 |

| Dimer 2 | 0 | −15.5346 |

| Dimer 3 | 0 | −8.4134 |

| Oligomer 1 | 0 | −24.8294 |

| 1 | −22.7924 | |

| 2 | −31.8566 | |

| 3 | −33.7282 | |

| 5 | −23.4097 | |

| Oligomer 2 | 0 | −31.1676 |

| 1 | −29.3356 | |

| 3 | −18.6350 | |

| 14 | −14.4214 |

PBA prevents hIAPP aggregation in vitro

Having determined in silico that PBA may bind directly to different hIAPP structures, we next assessed whether PBA could prevent hIAPP aggregation in cell-free systems. When hIAPP was placed in a solution with thioflavin T, an initial lag phase with no significant production of amyloid was followed by a rapid growth phase that led to a steady state in which soluble peptide was in equilibrium with amyloid fibrils (Fig. 6A). As expected, rat IAPP did not aggregate. Importantly, the addition of PBA prevented fibril formation in a dose-dependent manner, as a 22.7 and 58.2% reduction in the hIAPP aggregation plateau was observed in the presence of 5 and 25 mM PBA, respectively. We further assessed the inhibitory capacity of PBA on hIAPP aggregation by direct visualization of fibril formation by TEM. As shown in Fig. 6B, hIAPP in solution aggregated, forming dense clusters of amyloid fibrils. In contrast, when hIAPP peptide was incubated with 2.5 mM PBA, the fibrils were far fewer in number and appeared dispersed as smaller aggregates. These results confirm that PBA directly interacts with hIAPP and thereby prevents its aggregation.

Figure 6.

PBA prevents hIAPP aggregation. A) Thioflavin T assay was performed with hIAPP alone or combined with 2.5, 5, or 25 mM PBA. rIAPP was used as control. Representative data are shown from 2 independent experiments. B) Visualization of hIAPP fibrils by TEM of hIAPP solutions alone (left) or in combination with 2.5 mM PBA (right). Scale bars, 2 µm. Representative images from 2 independent samples are shown.

DISCUSSION

Islet amyloid is formed by aggregation of hIAPP, a peptide secreted by β cells along with insulin in response to glucose. hIAPP misfolding has been linked to amyloid formation as a result of either cellular stress or inflammation. These are important factors that induce hIAPP aggregation to oligomers, and eventually amyloid plaques. Thus, preventing hIAPP amyloid fibril formation is a logical approach in drug discovery for T2D. In the present study, we demonstrate that in vivo treatment with the chaperone PBA restores glucose homeostasis, ameliorates β-cell dysfunction, and prevents islet amyloid formation in mice expressing hIAPP in β cells.

PBA has been successfully applied in rodent models of metabolic disease to modulate ER stress responses and improve systemic metabolism (4). Moreover, PBA has already been tested in human studies, demonstrating its capacity for increasing insulin sensitivity, preventing lipotoxicity, and increasing insulin secretion (9–11). By demonstrating that PBA restores β-cell function in pancreatic islets exposed to amyloid deposition, we here have uncovered a novel beneficial action of PBA on one of the main tissues involved in the control of glucose homeostasis. The fact that PBA, with a good safety profile in vivo, has already been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for clinical use in urea-cycle disorders and cystic fibrosis (38, 39) may facilitate the potential application of PBA to restore β-cell function in the treatment of T2D.

Some reports have shown that ER stress–mediated apoptosis is exacerbated in rodent cells expressing amyloidogenic isoforms of hIAPP in β cells, leading to a reduction of β-cell mass in hIAPP Tg mice and rats (5). In addition, we have previously demonstrated that the extracellular addition of hIAPP induces ER stress in a mouse β-cell line (6). In contrast, we and others have shown that endogenously expressed hIAPP does not contribute to ER stress (8, 12, 40). The differences between these findings can be can be explained by the different experimental models used in each study. First, we have to consider the amount of hIAPP present in each model: when added exogenously or when overexpressed in cell lines, the levels of hIAPP are extremely high compared to the levels determined in hIAPP Tg mice (17). Furthermore, differences between in vivo models could be also explained by the levels of overexpression, since islet amyloid formation that occurs at physiologic levels of hIAPP does not result in ER stress, whereas marked increases in amyloidogenic hIAPP does result in an ER stress response (5, 7, 40). Thus, although we cannot completely exclude the notion that hIAPP expression or aggregation may be associated with ER stress under certain conditions or in a minor fraction of islet cells, it does not appear to be an obligatory mediator of the toxic effects of islet amyloid deposition. These data suggest that other events may play a prominent role in the progression of β-cell dysfunction associated with amyloid aggregation, such as islet inflammation (41).

Although the Tg mouse model used for this study does not exhibit amyloid deposits at the onset and even at more advanced stages of glucose intolerance, the global transcriptional analysis revealed a potent perturbation of the islet transcriptome. One of the main transcriptional changes is an increase in the expression of a large number of genes related to inflammation and extracellular matrix. Early aggregates of hIAPP have been shown to induce a release of proinflammatory chemokines and IL from pancreatic islets, such as CCL2 and CXCL1 (42). Moreover, hIAPP induces the secretion by macrophages of IL-1β, TNF-α, CCL2, and other proinflammatory molecules that can impair β-cell function (42–44). The increase in the expression of extracellular matrix genes suggests that fibrosis occurs in hIAPP Tg islets. Of note, fibrosis is usually linked to inflammation and is a common feature of T2D in several animal models as well as in humans (45, 46). Remarkably, PBA treatment resulted in a potent normalization of the islet transcriptome, almost completely preventing the induction of genes related to inflammation and extracellular matrix in hIAPP Tg islets. These results highlight the potential of PBA to abrogate islet inflammation, a main pathologic effect induced by hIAPP in pancreatic islets that ultimately results in β-cell dysfunction.

The exact mechanism responsible for β-cell cytotoxicity during hIAPP aggregation is still not well defined. It has been suggested that hIAPP fibrils or oligomers, rather than monomers or aggregated amyloid plaques, are responsible for toxicity in amyloid models of T2D (44, 47, 48). hIAPP Tg mice do not form islet amyloid plaques in vivo until treated with a high-fat diet for at least 1 yr (49); however, islet amyloid can be rapidly induced by culturing hIAPP Tg islets at high-glucose conditions ex vivo (35). Although knowledge about the structure of amyloid is still limited, small-molecule inhibitors may represent interesting candidates for preventing amyloid aggregation (17, 50). Furthermore, because in many ways T2D and AD share common pathogenic mechanisms (16), amyloid plaque inhibitors in AD may help us to explore strategies to inhibit amyloid formation in T2D. Along these lines, chemical chaperone PBA has been shown to attenuate amyloid plaque formation and facilitate cognitive memory performance in AD Tg mice (14). Of note, our studies showed that PBA decreased amyloid formation and β-cell death upon exposure to high glucose concentrations. Even more surprising was the observation that PBA was able to eliminate amyloid deposits that were already formed.

We also compared the effects on amyloid deposition of PBA with those produced by other agents that have been shown to protect hIAPP Tg islets. For instance, treatment of hIAPP Tg islets ex vivo with an antiinflammatory agent such as IL-1RA was not able to reduce amyloid severity. In line with these results, it has been demonstrated that IL-1RA treatment is able to improve glucose tolerance without reducing amyloid accumulation in obese hIAPP Tg mice (41). Similarly, overexpression of a chaperone that does not play a direct role in ER stress, such as PDI, did not reduce amyloid deposition, although we have previously demonstrated that it restores insulin secretion in hIAPP Tg islets (13). These results indicate a superior beneficial effect of PBA with respect to other agents that have already been shown to protect hIAPP Tg islets.

Because we do not detect activation of ER stress markers in islets from hIAPP Tg mice but PBA prevents and reverses amyloid accumulation, we further explored a potential mechanism of action of PBA. Indeed, our experimental observations favor the possibility of a direct interaction between PBA and the oligomer and hIAPP fibrils, ensuring a preventive and even a reversing effect on amyloid aggregation. This hypothesis was further supported by in silico analyses indicating that PBA may bind both the monomer and the oligomer forms of hIAPP, and by in vitro assays showing that PBA inhibits hIAPP fibril formation. We suggest that these direct interactions may disrupt the oligomer formation process and prevent its toxic effect, thus explaining the amelioration in insulin secretion, the almost complete normalization of the islet transcriptome, the decrease in inflammation, the reduction of islet amyloid plaques, and the general improvement in β-cell function.

In summary, we show here that the chemical chaperone PBA prevents amyloid formation, thus ameliorating β-cell dysfunction and improving glucose tolerance. Our findings point to a direct interaction between PBA and hIAPP that may avoid hIAPP aggregation and eventually abrogate amyloid-mediated islet inflammation and dysfunction. Because PBA has already been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, because it has a long-term safety profile, and because it is able to prevent and even reverse amyloid deposits, it provides important advantages with respect to other treatments that have also been shown to successfully protect hIAPP Tg islets. Our study uncovers a novel potential therapeutic action of PBA for the treatment of T2D by preventing the β-cell dysfunction and amyloid formation associated with this disease.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank M. T. Bowers (University of California, Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA, USA) and R. Tycko (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) for kindly providing the crystal structures of hIAPP. The authors also thank L. Llorach-Pares (Mind the Byte) for assistance in the computational analysis of hIAPP-PBA complexes. The authors acknowledge K. Katte (CIBERDEM) for editorial work. J.M. is a recipient of an IDIBAPS Postdoctoral Fellowship-BioTrack, supported by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (ECFP7/2007-2013) under Grant 229673. L.C. is a recipient of Fundação da Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT-PhD) fellowship SFRH/BD/65645/2009, financed by POPH-QREN. This work was supported by Grants PI11/00679 and PI14/00447, integrated in the Plan Estatal I + D + I 2013-2016 from the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad and cofinanced by the ISCIII-Subdirección General de Evaluación y Fomento de la investigación, Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER), the Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Diabetes y Enfermedades Metabólicas Asociadas (CIBERDEM), and the CERCA Programme (Generalitat de Catalunya), as well as with the support of Project 2014_SGR_520 of the Department of Universities, Research and Information Society of the Government of Catalonia. J.-M.S. and A.N. are joint senior authors. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- BiP

binding immunoglobulin protein

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FVB

Friend leukemia virus B

- HG + PA

high glucose and palmitate

- hIAPP Tg

human islet amyloid polypeptide transgenic

- hIAPP

human islet amyloid polypeptide

- IAPP

islet amyloid polypeptide

- IL-1RA

IL-1 receptor antagonist

- MM/GBSA

molecular mechanics/generalized born surface area

- PBA

4-phenylbutyrate

- PDI

protein disulfide isomerase

- rIAPP

rat islet amyloid polypeptide

- T2D

type 2 diabetes

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

- Tg

transgenic

- WT

wild type

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J. Montane, S. de Pablo, C. Castaño, J. Rodríguez-Comas, and J.-M. Servitja designed and performed experiments and analyzed data; L. Cadavez, M. Obach, M. Visa, and G. Alcarraz-Vizán performed experiments and analyzed data; M. Sanchez-Martinez and A. Nonell-Canals performed computational analysis; M. Parrizas contributed toward experimental design and data interpretation; J. Montane wrote the article, which was critically reviewed by J.-M. Servitja and A. Novials;. J.-M. Servitja and A. Novials conceived and directed the research and oversaw article preparation; and all authors approved the final version of the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Butler A. E., Janson J., Bonner-Weir S., Ritzel R., Rizza R. A., Butler P. C. (2003) β-Cell deficit and increased β-cell apoptosis in humans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 52, 102–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jurgens C. A., Toukatly M. N., Fligner C. L., Udayasankar J., Subramanian S. L., Zraika S., Aston-Mourney K., Carr D. B., Westermark P., Westermark G. T., Kahn S. E., Hull R. L. (2011) β-Cell loss and β-cell apoptosis in human type 2 diabetes are related to islet amyloid deposition. Am. J. Pathol. 178, 2632–2640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Westermark P., Engström U., Johnson K. H., Westermark G. T., Betsholtz C. (1990) Islet amyloid polypeptide: pinpointing amino acid residues linked to amyloid fibril formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 5036–5040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ozcan U., Yilmaz E., Ozcan L., Furuhashi M., Vaillancourt E., Smith R. O., Görgün C. Z., Hotamisligil G. S. (2006) Chemical chaperones reduce ER stress and restore glucose homeostasis in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Science 313, 1137–1140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang C. J., Lin C. Y., Haataja L., Gurlo T., Butler A. E., Rizza R. A., Butler P. C. (2007) High expression rates of human islet amyloid polypeptide induce endoplasmic reticulum stress mediated β-cell apoptosis, a characteristic of humans with type 2 but not type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 56, 2016–2027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casas S., Gomis R., Gribble F. M., Altirriba J., Knuutila S., Novials A. (2007) Impairment of the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway is a downstream endoplasmic reticulum stress response induced by extracellular human islet amyloid polypeptide and contributes to pancreatic beta-cell apoptosis. Diabetes 56, 2284–2294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montane J., Cadavez L., Novials A. (2014) Stress and the inflammatory process: a major cause of pancreatic cell death in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 7, 25–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soty M., Visa M., Soriano S., Carmona Mdel. C., Nadal Á., Novials A. (2011) Involvement of ATP-sensitive potassium (K(ATP)) channels in the loss of beta-cell function induced by human islet amyloid polypeptide. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 40857–40866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiao C., Giacca A., Lewis G. F. (2011) Sodium phenylbutyrate, a drug with known capacity to reduce endoplasmic reticulum stress, partially alleviates lipid-induced insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction in humans. Diabetes 60, 918–924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kars M., Yang L., Gregor M. F., Mohammed B. S., Pietka T. A., Finck B. N., Patterson B. W., Horton J. D., Mittendorfer B., Hotamisligil G. S., Klein S. (2010) Tauroursodeoxycholic acid may improve liver and muscle but not adipose tissue insulin sensitivity in obese men and women. Diabetes 59, 1899–1905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hetz C., Chevet E., Harding H. P. (2013) Targeting the unfolded protein response in disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 12, 703–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cadavez L., Montane J., Alcarraz-Vizán G., Visa M., Vidal-Fàbrega L., Servitja J. M., Novials A. (2014) Chaperones ameliorate beta cell dysfunction associated with human islet amyloid polypeptide overexpression. PLoS One 9, e101797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montane J., de Pablo S., Obach M., Cadavez L., Castaño C., Alcarraz-Vizán G., Visa M., Rodríguez-Comas J., Parrizas M., Servitja J. M., Novials A. (2016) Protein disulfide isomerase ameliorates β-cell dysfunction in pancreatic islets overexpressing human islet amyloid polypeptide. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 420, 57–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiley J. C., Pettan-Brewer C., Ladiges W. C. (2011) Phenylbutyric acid reduces amyloid plaques and rescues cognitive behavior in AD transgenic mice. Aging Cell 10, 418–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zraika S., Aston-Mourney K., Marek P., Hull R. L., Green P. S., Udayasankar J., Subramanian S. L., Raleigh D. P., Kahn S. E. (2010) Neprilysin impedes islet amyloid formation by inhibition of fibril formation rather than peptide degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 18177–18183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Götz J., Ittner L. M., Lim Y. A. (2009) Common features between diabetes mellitus and Alzheimer’s disease. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 66, 1321–1325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Couce M., Kane L. A., O’Brien T. D., Charlesworth J., Soeller W., McNeish J., Kreutter D., Roche P., Butler P. C. (1996) Treatment with growth hormone and dexamethasone in mice transgenic for human islet amyloid polypeptide causes islet amyloidosis and beta-cell dysfunction. Diabetes 45, 1094–1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ricobaraza A., Cuadrado-Tejedor M., Garcia-Osta A. (2011) Long-term phenylbutyrate administration prevents memory deficits in Tg2576 mice by decreasing Abeta. Front. Biosci. (Elite Ed.) 3, 1375–1384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreno-Asso A., Castaño C., Grilli A., Novials A., Servitja J. M. (2013) Glucose regulation of a cell cycle gene module is selectively lost in mouse pancreatic islets during ageing. Diabetologia 56, 1761–1772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Visa M., Alcarraz-Vizán G., Montane J., Cadavez L., Castaño C., Villanueva-Peñacarrillo M. L., Servitja J.-M., Novials A. (2015) Islet amyloid polypeptide exerts a novel autocrine action in β-cell signaling and proliferation. FASEB J. 29, 2970–2979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patil S. M., Xu S., Sheftic S. R., Alexandrescu A. T. (2009) Dynamic alpha-helix structure of micelle-bound human amylin. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 11982–11991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nanga R. P. R., Brender J. R., Vivekanandan S., Ramamoorthy A. (2011) Structure and membrane orientation of IAPP in its natively amidated form at physiological pH in a membrane environment. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1808, 2337–2342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dupuis N. F., Wu C., Shea J.-E., Bowers M. T. (2011) The amyloid formation mechanism in human IAPP: dimers have β-strand monomer–monomer interfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 7240–7243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luca S., Yau W. M., Leapman R., Tycko R. (2007) Peptide conformation and supramolecular organization in amylin fibrils: constraints from solid-state NMR. Biochemistry 46, 13505–13522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Felix E., Santamaria-Navarro E., Sanchez-Martinez M., Nonell-Canals A. Kin: A cloud based approach for blind docking. Available at www.mindthebyte.com/saas-platform/kin/. Accessed March 21, 2017.

- 26.Phillips J. C., Braun R., Wang W., Gumbart J., Tajkhorshid E., Villa E., Chipot C., Skeel R. D., Kalé L., Schulten K. (2005) Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 26, 1781–1802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jorgensen W. L. Chandrasekhar J. Madura J. D. Impey R. W., Klein M. L. (1983) Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 79, 926–935 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindorff-Larsen K., Piana S., Palmo K., Maragakis P., Klepeis J. L., Dror R. O., Shaw D. E. (2010) Improved side-chain torsion potentials for the Amber ff99SB protein force field. Proteins 78, 1950–1958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang J., Wolf R. M., Caldwell J. W., Kollman P. A., Case D. A. (2004) Development and testing of a general amber force field. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1157–1174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Case D. A., Berryman J. T., Betz R. M., Cerutti D. S., Cheatham I. T. E., Darden T. A., Duke R. E., Giese T. J., Gohlke H., Goetz A. W., Homeyer N., Izadi S., Janowski P., Kaus J., Kovalenko A., Lee T. S., LeGrand S., Li P., Luchko T., Luo R., Madej B., Merz K. M., Monard G., Needham P., Nguyen H., Nguyen H. T., Omelyan I., Onufriev A., Roe D. R., Roitberg A., Salomon-Ferrer R., Simmerling C. L., Smith W., Swails J., Walker R. C., Wang J., Wolf R. M., Wu X., York D. M., Kollman P. A. (2015) Amber15, University of California, San Francisco [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sousa da Silva A. W., Vranken W. F. (2012) ACPYPE—AnteChamber PYthon Parser interfacE. BMC Res. Notes 5, 367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller B. R. III, McGee T. D. Jr., Swails J. M., Homeyer N., Gohlke H., Roitberg A. E. (2012) MMPBSA.py: an efficient program for end-state free energy calculations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 8, 3314–3321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. (1996) VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 33–38, 27–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Potter K. J., Abedini A., Marek P., Klimek A. M., Butterworth S., Driscoll M., Baker R., Nilsson M. R., Warnock G. L., Oberholzer J., Bertera S., Trucco M., Korbutt G. S., Fraser P. E., Raleigh D. P., Verchere C. B. (2010) Islet amyloid deposition limits the viability of human islet grafts but not porcine islet grafts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 4305–4310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henson M. S., Buman B. L., Jordan K., Rahrmann E. P., Hardy R. M., Johnson K. H., O’Brien T. D. (2006) An in vitro model of early islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) fibrillogenesis using human IAPP-transgenic mouse islets. Amyloid 13, 250–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang P., Li W., Shea J. E., Mu Y. (2011) Resveratrol inhibits the formation of multiple-layered β-sheet oligomers of the human islet amyloid polypeptide segment 22-27. Biophys. J. 100, 1550–1558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meng F., Abedini A., Plesner A., Verchere C. B., Raleigh D. P. (2010) The flavanol(−)-epigallocatechin 3-gallate inhibits amyloid formation by islet amyloid polypeptide, disaggregates amyloid fibrils, and protects cultured cells against IAPP-induced toxicity. Biochemistry 49, 8127–8133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maestri N. E., Brusilow S. W., Clissold D. B., Bassett S. S. (1996) Long-term treatment of girls with ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 335, 855–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen W. Y., Bailey E. C., McCune S. L., Dong J. Y., Townes T. M. (1997) Reactivation of silenced, virally transduced genes by inhibitors of histone deacetylase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 5798–5803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hull R. L., Zraika S., Udayasankar J., Aston-Mourney K., Subramanian S. L., Kahn S. E. (2009) Amyloid formation in human IAPP transgenic mouse islets and pancreas, and human pancreas, is not associated with endoplasmic reticulum stress. Diabetologia 52, 1102–1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Westwell-Roper C. Y., Chehroudi C. A., Denroche H. C., Courtade J. A., Ehses J. A., Verchere C. B. (2015) IL-1 mediates amyloid-associated islet dysfunction and inflammation in human islet amyloid polypeptide transgenic mice. Diabetologia 58, 575–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Westwell-Roper C., Dai D. L., Soukhatcheva G., Potter K. J., van Rooijen N., Ehses J. A., Verchere C. B. (2011) IL-1 blockade attenuates islet amyloid polypeptide–induced proinflammatory cytokine release and pancreatic islet graft dysfunction. J. Immunol. 187, 2755–2765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Westwell-Roper C. Y., Ehses J. A., Verchere C. B. (2014) Resident macrophages mediate islet amyloid polypeptide–induced islet IL-1β production and β-cell dysfunction. Diabetes 63, 1698–1711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Montane J., Klimek-Abercrombie A., Potter K. J., Westwell-Roper C., Bruce Verchere C. (2012) Metabolic stress, IAPP and islet amyloid. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 14 (Suppl 3), 68–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Homo-Delarche F., Calderari S., Irminger J.-C., Gangnerau M. N., Coulaud J., Rickenbach K., Dolz M., Halban P., Portha B., Serradas P. (2006) Islet inflammation and fibrosis in a spontaneous model of type 2 diabetes, the GK rat. Diabetes 55, 1625–1633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Almaça J., Molina J., Arrojo E Drigo R., Abdulreda M. H., Jeon W. B., Berggren P. O., Caicedo A., Nam H. G. (2014) Young capillary vessels rejuvenate aged pancreatic islets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 17612–17617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haataja L., Gurlo T., Huang C. J., Butler P. C. (2008) Islet amyloid in type 2 diabetes, and the toxic oligomer hypothesis. Endocr. Rev. 29, 303–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zraika S., Hull R. L., Verchere C. B., Clark A., Potter K. J., Fraser P. E., Raleigh D. P., Kahn S. E. (2010) Toxic oligomers and islet beta cell death: guilty by association or convicted by circumstantial evidence? Diabetologia 53, 1046–1056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Verchere C. B., D’Alessio D. A., Palmiter R. D., Weir G. C., Bonner-Weir S., Baskin D. G., Kahn S. E. (1996) Islet amyloid formation associated with hyperglycemia in transgenic mice with pancreatic beta cell expression of human islet amyloid polypeptide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 3492–3496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wijesekara N., Ahrens R., Wu L., Ha K., Liu Y., Wheeler M. B., Fraser P. E. (2015) Islet amyloid inhibitors improve glucose homeostasis in a transgenic mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 17, 1003–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.