ABSTRACT

Cone snails are biomedically important sources of peptide drugs, but it is not known whether snail-associated bacteria affect venom chemistry. To begin to answer this question, we performed 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing of eight cone snail species, comparing their microbiomes with each other and with those from a variety of other marine invertebrates. We show that the cone snail microbiome is distinct from those in other marine invertebrates and conserved in specimens from around the world, including the Philippines, Guam, California, and Florida. We found that all venom ducts examined contain diverse 16S rRNA gene sequences bearing closest similarity to Stenotrophomonas bacteria. These sequences represent specific symbionts that live in the lumen of the venom duct, where bioactive venom peptides are synthesized.

IMPORTANCE In animals, symbiotic bacteria contribute critically to metabolism. Cone snails are renowned for the production of venoms that are used as medicines and as probes for biological study. In principle, symbiotic bacterial metabolism could either degrade or synthesize active venom components, and previous publications show that bacteria do indeed contribute small molecules to some venoms. Therefore, understanding symbiosis in cone snails will contribute to further drug discovery efforts. Here, we describe an unexpected, specific symbiosis between bacteria and cone snails from around the world.

KEYWORDS: cone snail, natural products, symbiosis, venom duct

INTRODUCTION

Cone snails are common marine mollusks that prey upon worms, fish, or other snails (1, 2). To do so, they synthesize complex peptide-based venoms that are injected into prey (3, 4). Many of the resulting peptides are biomedically important and include an FDA-approved treatment for pain (5). Recent data show that cone snails also contain bioactive secondary metabolites (6) and that at least some of these are likely synthesized by actinomycete bacteria. However, little is known about which bacteria live in cone snails and how they might impact the potency of peptide venoms. Answering this question could provide a new route to discovering potential pharmaceuticals while shedding light on the possible importance of symbiosis in the chemistry of cone snail venoms.

In early work on this topic, we showed that actinomycete bacteria are common associates of several cone snail species. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) revealed that the actinomycetes live in the foot and in the hepatopancreas (7). At least one actinomycete, Nocardiopsis alba, contributes to the biology of Conus rolani and Conus tribblei. In culture, N. alba synthesizes neuroactive polyketide pyrones, which were also detected in the mucus, body, and venom ducts of the host snails (8). Because of these associations, it is likely that N. alba secretes the pyrones in the host. However, it is notoriously challenging to directly measure microbial synthesis of compounds in situ. Thus, while this evidence is strong, it remains possible that there are also other sources of pyrone compounds, such as the hosts or other symbionts.

Moreover, Conus genuanus and Conus imperialis venom ducts are dominated by small molecules at the distal ends. Some of these have been characterized, including the widely occurring neurotransmitter serotonin and various xanthines. The snails also contain the novel secondary metabolite genuanine, which causes paralysis in mice and is the major organic solvent-extractable component in the distal portion of the venom ducts (6). It is intriguing that small molecules such as genuanine contribute to the potency of cone snail venoms, which were previously thought to be dominated by peptides. While it is known that the venom peptides are synthesized by cone snails (9), the biosynthetic origin of genuanine is not known. Another unknown is whether bioactive small molecules are widespread in cone snail venoms or whether they are instead restricted to a few species. Thus, much remains to be learned about this intriguing and newly discovered aspect of cone snail biology.

The biological activities of genuanine and nocapyrones in neurological assays suggest that small molecules may contribute to the ecological function of cone snail venoms. Since the cone snail venoms are environmentally important and have such an outsized impact on biomedical science, better understanding the contribution of small molecules and bacteria to venom activity is an important problem. Here, we sought to address a key part of this problem: to determine whether specific bacterial symbionts are present in venom ducts. Secondarily, we assessed whether actinomycete bacteria dominate the microbiota of cone snails, or whether other bacterial types are more abundant. To answer these questions, we examined the microbiomes of cone snails from around the world (Fig. 1) and compared their constituents to those of other tropical animals (see Tables S1 and S2 in the supplemental material). We found that the cone snail microbiome is relatively conserved, and that the venom ducts of all sampled cone snails contain symbiotic bacteria similar to those of the genus Stenotrophomonas.

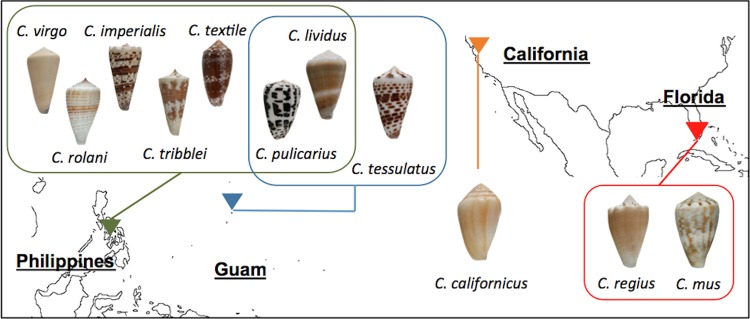

FIG 1.

Cone snail species and collection locations in this study. See Tables S1 and S2 in the supplemental material for a complete list of species (including non-cone snail species) and locations of samples sequences in this study. (Photos by My Thi Thao Huynh.)

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Cone snails have a distinct and consistent bacterial community.

We first sought to determine whether cone snails have a distinctive microbiota. To do so, using 454 pyrosequencing of bacterial 16S rRNA gene amplifications we performed an initial survey comparing a small set of cone snail samples from around the world with those of ascidians and non-cone snail mollusks collected at the same time and location. We examined one sample each of Conus rolani and Conus tribblei from the Philippines, Californiconus californicus from California, and Conus regius and Conus mus from Florida. Results from the ascidian microbiome sequencing analysis were previously reported (10); here, they are compared with those from mollusks. We found that the microbiota in mollusk samples is distinct from that found in ascidians (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), and further, cone snails appeared to contain a bacterial community that was distinct and consistent compared to that of other organisms (Fig. 2A). This initial correlative finding prompted us to perform a more thorough analysis. In addition, it should be noted that Nocardiopsis sequences were found as expected in several samples.

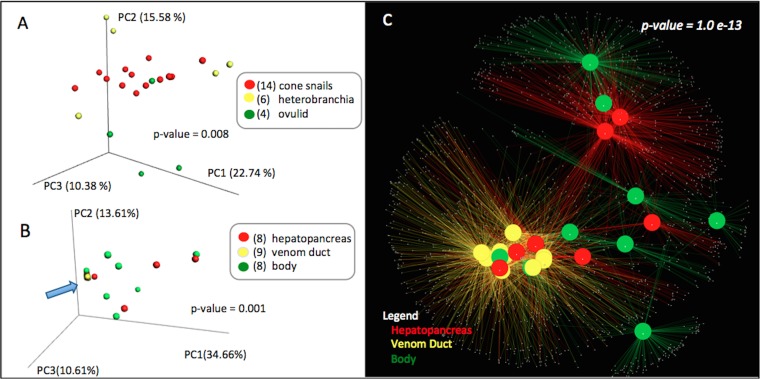

FIG 2.

The venom duct harbors a conserved microbiota. (A and B) Beta diversity analyses through principal-coordinate analysis (PCoA) plots of weighted UniFrac distances show cone snails in comparison to other taxa (A) and a comparison of tissues within cone snails in which venom duct samples (blue arrow) are strongly clustered (B). (C) Cytoscape network-based analysis of cone snail microbiome based on tissue type shows the same high degree of clustering of sequences in venom ducts of all cone snail samples.

Composition of the cone snail microbiome.

We performed a more thorough 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing and analysis using multiple replicates of cone snail species collected at the same time and location. Illumina MiSeq was used to analyze three species of cone snails: Conus pulicarius (n = 3), Conus tessulatus (n = 3), and Conus lividus (n = 3). Cone snails were dissected to generate three samples each of different body parts: body, venom duct, and hepatopancreas. In total, 25 cone snail samples were independently sequenced and analyzed. We compared these with samples of sponges (n = 7) and four species of marine gastropods from the clade Heterobranchia (n = 9). The heterobranchs were dissected to generate 18 samples coming from different body parts: mantle, pustules, and interior body.

After quality-based trimming and filtering, a total of 1,486,227 16S rRNA gene sequences from the 25 cone snail samples were generated. Reads from cone snails were classified into 7,960 operational taxonomic units (OTUs) (defined as 97% sequence identity), with an average of 150 OTUs per sample. The Shannon index and the Chao 1 richness indicator suggest that in the sequenced sample set, sufficient sequencing depth was obtained to adequately capture the diversity of microbial communities (Tables S4 and S5). Rarefaction curves from the alpha diversity plot show that sequence diversity in cone snails is low compared to that of other marine organisms such as sponges and heterobranch mollusks (Fig. S2A). Plots also show that there is little variation in terms of sequence diversity among cone snail species (Fig. S2B).

At the phylum level, the cone snail microbiome is dominated by Proteobacteria (Fig. S3). Proteobacterial OTU sequences are abundant across species and replicates sampled, making up 78.3% of all sequences and up to 90% of sequences in specific samples, such as many of the venom ducts. This result is consistent with the earlier 454 pyrosequencing cone snail data set, which was also dominated by Proteobacteria. Other abundant sequences were classified to be from the phyla Cyanobacteria (10.7%), Firmicutes (6.5%), and Actinobacteria (2.9%). Sequences related to Cyanobacteria were abundant only in the body and hepatopancreas of C. pulicarius and C. lividus. Sequences in the phylum Firmicutes were detected in samples representing cone snail body and hepatopancreas regardless of species. Altogether, 17 bacterial phyla were identified in cone snails, and only 0.9% of all sequence reads remained unclassified.

Microbial communities found in cone snails are distinct compared to those in the sponges and heterobranchs studied here (Fig. S4A). Principal-coordinate analyses using phylogenetic distances computed from weighted Unifrac values show significant clustering (P = 0.001) when grouped according to animal type (i.e., cone snails, sponges, heterobranchs). We did not find any correlation between cone snail microbiomes and geographical location (Fig. S4B). Beta-diversity analyses of microbial communities of cone snails from Florida, California, and the Philippines show no significant differences (P = 0.110). We also did not observe any correlation between microbiome and cone snail species (P = 0.259) (Fig. S4C). However, when sequences from different cone snail tissues were compared, venom ducts clustered strongly (P = 0.001) (Fig. 2B). This relationship is reinforced in network analyses, in which a high degree of OTU similarity is observed between all venom duct samples (P = 1.0e−13; Fig. 2C).

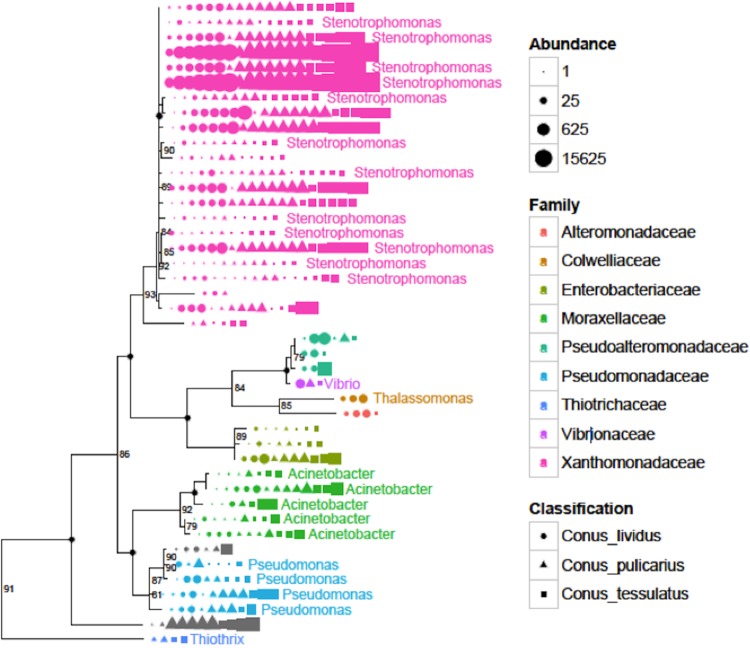

To understand what drives the high degree of clustering observed in cone snail venom ducts, we selected two different methods to examine the distribution of bacteria in the ducts (Fig. 3). First, we aimed to find the most commonly distributed bacteria, selecting strains that were shared by at least 50% of the venom duct samples. Second, we sought the most numerically dominant bacteria, selecting those with OTUs that were the top 10 most abundant in the microbiome and that were at that abundance level in every sample. Strikingly, sequences from the genus Stenotrophomonas (Gammaproteobacteria) account for at least 50% of the proteobacterial sequences in every venom duct, and the sequences are also common in the hepatopancreas. The sequences are not identical but form a tightly clustered branch on phylogenetic trees. Other shared OTUs from the venom ducts are from the families Caulobacteraceae and Propionibacteriacaeae and other Gammaproteobacteria groups, including the genera Acinetobacter and Vibrio.

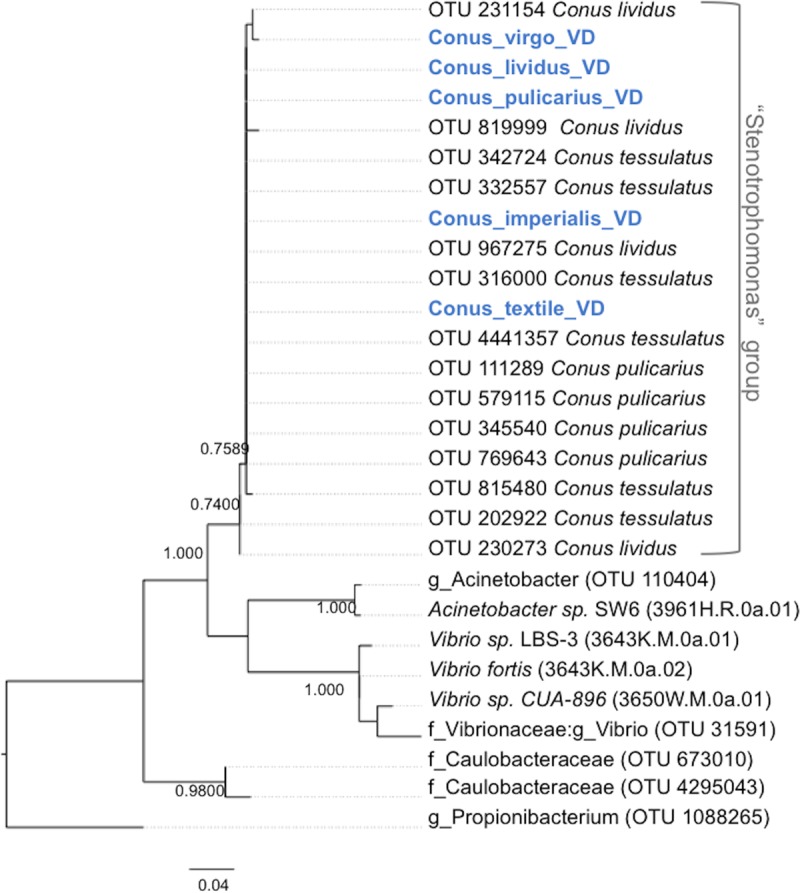

FIG 3.

Stenotrophomonas-like sequences are present in cone snail venom ducts. A maximum likelihood tree of 16S rRNA gene sequences was generated from Illumina-sequenced venom ducts (see Materials and Methods).

Stenotrophomonas is a widely occurring genus most commonly associated with plants and animals (11). It is found consistently in plants, rhizomes, soil, and human medical samples such as pleural fluid and blood. Strains are also found in the oceans and have been isolated from tissues of deep-sea invertebrates (12). Of particular relevance to pharmaceutical potential, Stenotrophomonas spp. sometimes produce toxic small molecules, such as maltophilin (13) and lytic enzymes (14). They are also well known for the production of secreted protease (15); speculatively, this could play a role in the interaction between symbiotic bacteria and peptidic venom components.

Stenotrophomonas-like bacteria are symbionts in the Conus venom duct.

The relative abundance and universal presence of Stenotrophomonas-like sequences in cone snail venom ducts led us to hypothesize that these bacteria are specific symbionts of these shelled mollusks. To test this hypothesis, we first reevaluated the initial 454 data set, determining that the Stenotrophomonas-like sequence is present in the single venom duct initially sequenced. This widespread sequence occurrence in eight cone snail species from distinct geographic locales increased our confidence that this was a specific relationship, but we sought further data to rule out other possibilities.

We therefore collected additional cone snails from different locations in the Philippines at different times of year (Table S3). The cone snail venom ducts in this new set included two of the species sequenced in the Illumina set (C. lividus and C. pulicarius) and four species that were not previously examined in the 454 data set described above (Conus textile, Conus imperialis, Conus sponsalis, and Conus virgo). Using PCR with Stenotrophomonas-specific primers followed by Sanger sequencing, we found that the venom ducts of all cone snails contained the Stenotrophomonas-like 16S rRNA gene sequences. Notably, these sequences differ from each other and from those found in other animals, further demonstrating that the Stenotrophomonas sequences originate in the samples (Fig. 4). Species with relatively long venom ducts (C. imperialis and C. textile) allowed for further partitioning by our performing PCR on three different locations (proximal, medial, and distal to the venom bulb), showing that Stenotrophomonas-like sequences were present along the length of the venom duct (Fig. S5). These results confirmed the hypothesis that Stenotrophomonas-like sequences are ubiquitously and specifically associated with cone snail venom ducts. Combining these results with results from DNA sequencing, we found Stenotrophomonas sequences in venom ducts of 10 cone snail species from Florida, California, the Philippines, and Guam. Additionally, with longer sequences available, we compared cone snail associates to previously cultivated Stenotrophomonas spp. and their relatives. We found that the venom duct associates cluster in a single clade (Fig. S6).

FIG 4.

Similar Stenotrophomonas-like sequences are broadly found in cone snails. PCR-amplified 16S rRNA gene sequences from C. virgo, C. lividus, C. pulicarius, C. imperialis, and C. textile (in blue) were aligned with OTUs obtained from the Illumina-sequenced venom ducts and used to generate a maximum likelihood tree (see Materials and Methods).

Stenotrophomonas-like symbionts inhabit the lumen of the venom duct.

To verify the presence of Stenotrophomonas-like bacteria in the cone snail venom duct, we performed FISH analysis using fixed tissues from C. virgo. By light microscopy, we defined the structure of the C. virgo venom duct as being very similar to previously studied cone snail venom ducts (16–18), including exterior tissue, a muscular duct, and a lumen containing both cellular and extracellular material, the latter of which is likely to comprise venom-containing granules as found in other cone snails (Fig. 5A). Fluorescent probes were designed and validated using cultivated bacteria with sequences similar to those found in cone snail venom ducts. Probes included the general bacterial probe EUB338, a Stenotrophomonas-specific probe, and mismatch versions of those probes as controls. By FISH, the Stenotrophomonas-like symbiont was the most abundant species present in the lumen of the duct (Fig. 5B to D and S8), where venom-containing granules are present, and nucleated cells were not visible by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining. This statement is based upon the fact that Cy5-labeled Stenotrophomonas (STEN) probe-positive particles were greater than 50% of EUB338-labeled particles in all frames, and upon our finding that bacteria other than Stenotrophomonas were highly heterogeneous in Illumina sequencing data (i.e., no other single strain would comprise the other 50% of cells in the image).

FIG 5.

Stenotrophomonas spp. are localized in the lumen of the venom duct. (A) Light micrograph of a hematoxylin and eosin-stained cross section of a C. virgo venom duct (PMS-3669S) showing the region examined in FISH, the lumen. (B) FISH using bacterial probe Eub338 in the Cy3 channel. (C) FISH using the Stenotrophomonas-specific STEN probe in the Cy5 channel. (D) Overlay of panels B and C. Arrows highlight examples of cells that bind both probes, demonstrating the presence of Stenotrophomonas-like symbionts. Control images using mismatch probes, as well as cultivated bacteria, are shown in Fig. S6.

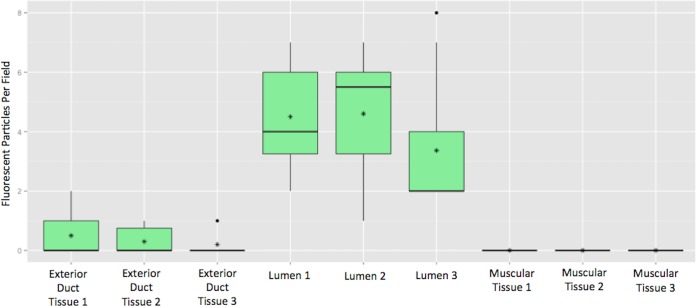

No bacteria were observed in the muscle tissue. External to the duct, several different bacterial species appeared to be present, including the Stenotrophomonas-like strain, since cells were stained with EUB338 that were not stained by the STEN probe (Fig. S9). By manual counting, in three sectioned tissue samples from a single mollusk (Fig. 6), we estimated that approximately 80 STEN-stained fluorescent particles per nanoliter are present in the venom duct lumen. Since multiple bacteria can be part of a single particle, this puts a lower limit on the number of Stenotrophomonas-like bacteria present in those sections. For comparison, this lies within the range of various estimates of bacterial concentration in human saliva (19).

FIG 6.

Abundance of Stenotrophomonas-like bacteria observed in Conus virgo venom duct. Box plot shows the number of fluorescent particles that positively hybridized with the Stenotrophomonas-specific probe. Fluorescent particles were quantitated in three venom duct sections of a single specimen of Conus virgo (PMS-3669S). Counts are average number of particles per section measuring 100 × 100 × 5 μm. Each fluorescent particle represents one or more bacterial cells. Vertical lines indicate the range of values, and horizontal lines indicate the median. Dots and asterisks represent outliers and mean, respectively.

These results demonstrate that Stenotrophomonas-like bacteria are likely to be specific symbionts of cone snails, although we do not know what type of relationship the symbionts might have with their hosts (mutualist, pathogen, etc.). It is remarkable that specific bacteria survive and apparently thrive in the challenging environment of the venom duct. The duct is heavily laden with hydrophobic peptides, at least some of which are likely to possess lytic activity in high doses. In addition, a specific cytolytic peptide was previously identified in the cone snail Conus vexillum (20). Because of the importance of cone snail venoms in biomedicine, it is worth further investigating how the bacteria survive in venom ducts and whether or not they contribute to (or detract from) the biological function of the venoms in subduing prey.

Cultivation of cone snail associates.

Because Stenotrophomonas spp. are relatively well studied, we attempted to cultivate the strains using common methods developed for the genus as well as using methods for marine bacteria. Using venom ducts from C. textile, C. imperialis, C. sponsalis, C. sugillatus (specimen PMS-3650W), and C. virgo (specimen PMS-3669S), we isolated 25 strains of bacteria and sequenced their 16S rRNA genes. None of the isolates were Stenotrophomonas, but instead represented the phyla Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, and Actinobacteria. Isolates from Proteobacteria were mostly Gammaproteobacteria from the genera Acinetobacter, Vibrio, Pseudoalteromonas, Reugeria, and Kistomonas (Table S6). Several of these had 16S rRNA gene sequences that were identical to those found in the microbiome sequence set, while others had no sequenced relative in the data (Table S5). This result shows that we recovered some of the true associates of cone snails, but we have yet to succeed in obtaining a Stenotrophomonas-like symbiont. This is not unexpected, since true symbionts are often challenging to cultivate.

Conclusion.

Here, we describe a 16S rRNA gene sequence survey defining the core microbiota of cone snails. The cone snail microbiota is conserved in eight species collected around the world and is distinct from microbiotia in other colocalized organisms studied. Further, we provide evidence defining Stenotrophomonas-like bacteria as specific symbionts inhabiting the venom ducts of cone snails.

Although we do not define the biological roles of Stenotrophomonas, there are a number of ways that the bacteria might impact predation or venoms. In other well-studied cases, the animal microbiota plays an important role in regulating the host's biochemical processes. In particular, many studies implicate bacteria in swaying signaling pathways and in regulating the secretion and stability of bioactive peptides. For example, in humans certain bacteria stimulate the secretion of GLP-1 and other peptide hormones (21). Symbiotic bacteria also influence host chemistry in other ways, for example by secreting bioactive secondary metabolites (22). Further work will be required to determine whether cone snail symbionts impact venoms in similar ways.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection and DNA extraction.

All samples (Tables S1 and S2 in the supplementary material) were collected with appropriate permits from the local and national governments. Specimens were dissected and processed on site except for those from Florida, which were obtained by a professional collector and shipped live to Utah. Dissected tissue samples were divided and stored in RNAlater, 20% glycerol, or isopropanol. DNA was extracted using previously described methods (10) and further purified by using either Genomic-tip (Qiagen) or Concentrator (Zymo Research). The quality of extracted DNA was checked by amplification of 16S rRNA genes using bacterial primers 27F (GTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG) and 1492R (GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT) before amplicon sequencing.

16S rRNA amplicon sequencing.

Extracted DNA samples from animals were submitted to Research and Testing Laboratory (RTL, Lubbock, TX) for sequencing. RTL amplified the hypervariable regions V1 to V3 of the 16S rRNA gene using primers 28F (AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG) and 388R (GCTGCCTCCCGTAGGAGT) and sequenced the resulting amplicons using either Roche 454 or Illumina MiSeq (single-end reads).

16S rRNA gene analysis.

16S rRNA gene sequences were analyzed using QIIME and phyloseq. RTL-generated FASTA files were demultiplexed, quality filtered, and checked for chimeras using default parameters in QIIME prior to analyses. De novo OTU picking was used for sequences generated from 454 pyrosequencing, while open-reference OTU picking was used for sequences generated from Illumina MiSeq. OTU was defined as having at least 97% nucleotide sequence identity. Taxonomic classification of OTUs was done using Greengenes database (23). Alpha diversity, beta diversity, and principal-coordinate analyses were done in QIIME (24). Visualized networks were done in Cytoscape (25) while core OTU and top 10 OTU picking was done in phyloseq (26). For the phylogenetic tree shown in Fig. 3, the top 10 most abundant OTUs were selected from each sample using QIIME. OTUs were selected only if they were present in at least five (out of nine) venom duct samples. These OTUs were analyzed using a maximum likelihood algorithm based on the Tamura-Nei model using the default parameters of QIIME. Phyloseq was used to visualize the analysis. For the tree shown in Fig. 4, OTUs found in Fig. 3 were combined with trimmed sequences from Sanger-sequenced PCR products of other cone snail species. Sequences were aligned in Ugene and analyzed in MEGA7, generating a maximum likelihood tree using Tamura-Nei.

Bacterial isolation and identification.

Tissue samples were homogenized using a sterile mortar and pestle and suspended in sterile seawater. The homogenate was used to make a dilution series. Aliquots (100 to 200 μl) of each dilution were plated on agar media (Marine, R2A, yeast extract-peptone-dextrose [YPD], Nutrient, Muller-Hinton, and tryptic soy). Plates were incubated at 25°C until colonies became visible. Colonies of different morphotypes were selected and purified by successive streaking on agar plates. Isolation was continued until no new colonies were observed. To identify strains, colonies were lysed at 100°C for 10 min in water and used directly in PCR with bacterial 16S primers 27F and 1492R. Reactions were run using a C1000 Touch thermal cycler (Bio-Rad) with the following conditions: 60 s of denaturation at 95°C, 35 amplification cycles (30 s at 95°C, 45 s at 54°C, and 60 s at 72°C), and extension for 300 s at 72°C. Stenotrophomonas-specific 16S rRNA gene fragments were amplified using primers Steno F (GGCGGACGGGTGAGGAATACATC) and Steno R (CGATGCGAACTGGATGTTGGGT). The specific primers were designed using the abundant Stenotrophomonas-like OTUs and full 16S rRNA gene sequences of Stenotrophomonas strains from the NCBI database. PCR conditions were as follows: 60 s of denaturation at 95°C, 35 amplification cycles (30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 54°C, and 45 s at 68°C), and extension for 30 s at 72°C. All PCRs in this study were performed using Taq DNA polymerase (0.1 μl; New England BioLabs) in the manufacturer's recommended buffer, with the following additions: dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (0.4%), 0.2 μM each primer, 10 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) mixture. In general, template DNA or lysed cells (2 μl) were used in 10-μl final reaction volumes. PCR products were sent to Genewiz (South Plainfield, NJ) for Sanger sequencing using the PCR primers. Closest sequence relatives were determined by searching the GenBank database with BLASTn.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization.

Dissection and fixation of venom ducts were performed with freshly obtained animals. Venom duct tissues were cut into sections of approximately 1 mm3 and washed with sterile seawater. Tissue sections were then fixed at room temperature for 30 min with a solution containing 4% paraformaldehyde (adjusted to pH 7.2 with 1 M NaOH) and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Fixative was removed, and the tissue was dehydrated with 100% ethanol for 20 min and 70% ethanol for 20 min, and finally stored in 70% ethanol at 4°C. Fixed venom ducts were embedded in paraffin and cross-sectioned to 5-μm thickness. Sectioned venom duct tissues were hybridized with Cy3-labeled eubacterial probe EUB338 (GCTGCCTCCCGTAGGAGT) and Cy5-labeled Stenotrophomonas probe (STEN) (GTCGTCCAGTATCCACTGC). Nonsense probes Cy3-labled nonEUB338 (ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGC) and Cy5-labeled non-STEN (ATCATCCAGTATCCACTAC) were used as negative controls. Probe hybridization was done by incubating the tissue in a buffer containing 20% formamide, 1.25 M NaCl, 25 mM Tris, 0.0125% SDS, and probe (5 ng/μl) for 2 h at 46°C. After hybridization, the tissue sections were washed for 20 min at 48°C by incubation in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris, 5 mM EDTA, 220 mM NaCl, and 0.01% SDS. Tissues were then air-dried and mounted with a coverslip in anti-fade mounting medium (Vectashield). Images were captured by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) using an Olympus FV1000 system. Probe specificities and hybridization conditions were optimized using Stenotropohomonas maltophilia (ATCC 13637) as a positive control and the closely related strain Pseudoxanthomonas kalamensis (ATCC BAA1031) as a negative control.

To estimate the abundance of Stenotrophomonas-like symbionts in the venom duct, fluorescent particles were counted in three venom duct sections from a single specimen of Conus virgo that had been treated with the Stenotrophomonas-specific STEN probe. For each of three venom duct sections, fluorescent particles were manually counted over 10 frames, each with an area of 100 × 100 μm, in the exterior duct tissue, lumen, and muscle tissue. This procedure was repeated using adjacent tissue sections treated with the negative-control non-STEN probe. Counts per frame were generated by subtracting the negative-control counts from STEN probe counts. Boxplots were done using ggplot2 (27) in R.

Accession number(s).

Sequences from DNA samples were deposited in GenBank under the BioProject number PRJNA390969.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by an International Cooperative Biodiversity Group project sponsored by the Fogarty International Center (NIH U19 TW008163) and by NIH R01 GM107557.

We thank Victor Chua (University of the Philippines) for his assistance during sample collection in the Philippines and the University of Southern California's Wrigley Marine Science Center for aid with collecting California specimens. We also thank My Thi Thao Huynh for all the cone snail photos. Imaging was performed at the Fluorescence Microscopy Core Facility, a part of the Health Sciences Core at the University of Utah. Microscopy equipment was obtained using NCRR Shared Equipment Grant 1S10RR024761-01.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01418-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Olivera BM, Seger J, Horvath MP, Fedosov AE. 2015. Prey-capture strategies of fish-hunting cone snails: behavior, neurobiology and evolution. Brain Behav Evol 86:58–74. doi: 10.1159/000438449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olivera BM, Watkins M, Bandyopadhyay P, Imperial JS, de la Cotera EP, Aguilar MB, Vera EL, Concepcion GP, Lluisma A. 2012. Adaptive radiation of venomous marine snail lineages and the accelerated evolution of venom peptide genes. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1267:61–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06603.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fedosov AE, Moshkovskii SA, Kuznetsova KG, Olivera BM. 2012. Conotoxins: from the biodiversity of gastropods to new drugs. Biochem (Mosc) Suppl Ser A Biomed Chem 6:107–122. doi: 10.1134/S1990750812020059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han TS, Teichert RW, Olivera BM, Bulaj G. 2008. Conus venoms - a rich source of peptide-based therapeutics. Curr Pharm Des 14:2462–2479. doi: 10.2174/138161208785777469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miljanich GP. 2004. Ziconotide: neuronal calcium channel blocker for treating severe chronic pain. Curr Med Chem 11:3029–3040. doi: 10.2174/0929867043363884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neves JL, Lin Z, Imperial JS, Antunes A, Vasconcelos V, Olivera BM, Schmidt EW. 2015. Small molecules in the cone snail arsenal. Org Lett 17:4933–4935. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peraud O, Biggs JS, Hughen RW, Light AR, Concepcion GP, Olivera BM, Schmidt EW. 2009. Microhabitats within venomous cone snails contain diverse actinobacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:6820–6826. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01238-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin Z, Torres JP, Ammon MA, Marett L, Teichert RW, Reilly CA, Kwan JC, Hughen RW, Flores M, Tianero MD, Peraud O, Cox JE, Light AR, Villaraza AJ, Haygood MG, Concepcion GP, Olivera BM, Schmidt EW. 2013. A bacterial source for mollusk pyrone polyketides. Chem Biol 20:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Espiritu DJ, Watkins M, Dia-Monje V, Cartier GE, Cruz LJ, Olivera BM. 2001. Venomous cone snails: molecular phylogeny and the generation of toxin diversity. Toxicon 39:1899–1916. doi: 10.1016/S0041-0101(01)00175-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tianero MD, Kwan JC, Wyche TP, Presson AP, Koch M, Barrows LR, Bugni TS, Schmidt EW. 2015. Species specificity of symbiosis and secondary metabolism in ascidians. ISME J 9:615–628. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryan RP, Monchy S, Cardinale M, Taghavi S, Crossman L, Avison MB, Berg G, van der Lelie D, Dow JM. 2009. The versatility and adaptation of bacteria from the genus Stenotrophomonas. Nat Rev Microbiol 7:514–525. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Romanenko LA, Uchino M, Tanaka N, Frolova GM, Slinkina NN, Mikhailov VV. 2008. Occurrence and antagonistic potential of Stenotrophomonas strains isolated from deep-sea invertebrates. Arch Microbiol 189:337–344. doi: 10.1007/s00203-007-0324-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jakobi M, Winkelmann G, Kaiser D, Kempler C, Jung G, Berg G, Bahl H. 1996. Maltophilin: a new antifungal compound produced by Stenotrophomonas maltophilia R3089. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 49:1101–1104. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.49.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong H, Zhu C, Chen J, Ye X, Huang YP. 2015. Antibacterial activity of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia endolysin P28 against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Front Microbiol 6:1299. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyaji T, Otta Y, Shibata T, Mitsui K, Nakagawa T, Watanabe T, Niimura Y, Tomizuka N. 2005. Purification and characterization of extracellular alkaline serine protease from Stenotrophomonas maltophilia strain S-1. Lett Appl Microbiol 41:253–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2005.01750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Endean R, Duchemin C. 1967. The venom apparatus of Conus magus. Toxicon 4:275–284. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(67)90056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marshall J, Kelley WP, Rubakhin SS, Bingham JP, Sweedler JV, Gilly WF. 2002. Anatomical correlates of venom production in Conus californicus. Biol Bull 203:27–41. doi: 10.2307/1543455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Page LR. 2012. Developmental modularity and phenotypic novelty within a biphasic life cycle: morphogenesis of a cone snail venom gland. Proc Biol Sci 279:77–83. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.0501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sender R, Fuchs S, Milo R. 2016. Revised estimates for the number of human and bacteria cells in the body. PLoS Biol 14:e1002533. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdel-Rahman MA, Abdel-Nabi IM, El-Naggar MS, Abbas OA, Strong PN. 2013. Conus vexillum venom induces oxidative stress in Ehrlich's ascites carcinoma cells: an insight into the mechanism of induction. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis 19:10. doi: 10.1186/1678-9199-19-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Everard A, Cani PD. 2014. Gut microbiota and GLP-1. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 15:189–196. doi: 10.1007/s11154-014-9288-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davidson SK, Allen SW, Lim GE, Anderson CM, Haygood MG. 2001. Evidence for the biosynthesis of bryostatins by the bacterial symbiont “Candidatus Endobugula sertula” of the bryozoan Bugula neritina. Appl Environ Microbiol 67:4531–4537. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.10.4531-4537.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeSantis TZ, Hugenholtz P, Larsen N, Rojas M, Brodie EL, Keller K, Huber T, Dalevi D, Hu P, Andersen GL. 2006. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:5069–5072. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03006-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Pena AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI, Huttley GA, Kelley ST, Knights D, Koenig JE, Ley RE, Lozupone CA, McDonald D, Muegge BD, Pirrung M, Reeder J, Sevinsky JR, Turnbaugh PJ, Walters WA, Widmann J, Yatsunenko T, Zaneveld J, Knight R. 2010. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods 7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B, Ideker T. 2003. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res 13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. 2013. phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS One 8:e61217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wickham H. 2009. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.