Abstract

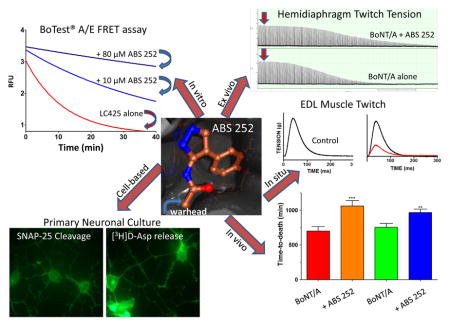

Botulinum neurotoxins (BoNTs) are the most toxic substances known to mankind and are the causative agents of the neuroparalytic disease botulism. Their ease of production and extreme toxicity have caused these neurotoxins to be classified as Tier 1 bioterrorist threat agents and have led to a sustained effort to develop countermeasures to treat intoxication in case of a bioterrorist attack. While timely administration of an approved antitoxin is effective in reducing the severity of botulism, reversing intoxication requires different strategies. In the present study, we evaluated ABS 252 and other mercaptoacetamide small molecule active-site inhibitors of BoNT/A light chain using an integrated multi-assay approach. ABS 252 showed inhibitory activity in enzymatic, cell-based and muscle activity assays, and importantly, produced a marked delay in time-to-death in mice. The results suggest that a multi-assay approach is an effective strategy for discovery of potential BoNT therapeutic candidates.

Keywords: botulism, botulinum toxin, botulinum neurotoxin, mercaptoacetamide, metalloprotease inhibitor, SNAP-25, SNARE protein, X-ray crystallography

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Botulinum neurotoxins (BoNTs) have been studied extensively for well over a century (Simpson, 2004; Simpson, 2013; Rossetto et al., 2014). While much knowledge has been gleaned from this effort, the ability to rescue intoxicated hosts from BoNT-mediated paralysis has remained elusive (Cai and Singh, 2007; Seki et al., 2015; Kumaran et al., 2015). BoNT/A is the most toxic of the seven established serotypes, with BoNT/B, /E and /F also showing lethal effects in humans (Simpson, 2004; Montgomery et al., 2015). The neurotoxins are comprised of a heavy chain (HC) and a light chain (LC), which after proteolytic processing, are covalently linked by a single interchain disulfide bond (DasGupta and Sugiyama, 1972). The HC is responsible for the binding and internalization of BoNT into motor neuron terminals, while the LC is responsible for the observed neurotoxicity (Bandyopadhyay et al., 1987; Dolly et al., 1990; Colasante et al., 2013). The LC is a Zn2+-dependent metalloprotease, which in the case of BoNT/A, catalyzes the cleavage of the Gln197-Arg198 bond of SNAP-25 (synaptosome-associated protein of 25 kDa) (Blasi et al., 1993; Schiavo et al., 1994). SNAP-25 is a critical component of the SNARE complex that controls release of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. Since acetylcholine is required for neuromuscular and autonomic function (Wu et al., 2012), intoxication by BoNT/A leads to flaccid paralysis and autonomic dysfunction.

Therapy for botulism relies on antitoxins to neutralize BoNT in circulation, and severe cases require intensive care with artificial ventilation (Cheng et al., 2009; Trott et al., 2009; Yu et al., 2009; Adler et al., 2014). Currently, only one formulation of antitoxin is licensed for clinical use: a despeciated equine-derived heptavalent botulism antitoxin (BAT®) that received FDA approval in 2013 (Hill et al., 2013). Antitoxins although effective, cannot be relied on as the sole treatment for botulism. In addition to the difficulty and cost of producing and stockpiling large quantities of antitoxin, a sizable percent of the population may show hypersensitivity to the equine-derived product (Hibbs et al, 1996). The greatest shortcoming of antitoxin therapy, however, is that this approach is useful only in neutralizing toxin that remains within the bloodstream (Ravichandran et al., 2006), not in reversing the consequences of intoxication.

Moreover, although dilute forms of the toxin have been approved for medical and aesthetic use (Münchau and Bhatia, 2000; Shukla and Sharma, 2005), intoxication can occur even with controlled clinical doses of BoNT (Crowner et al., 2007). Treatment of BoNT intoxication following a bioterrorist attack, natural outbreak or clinical overdose requires a therapeutic agent that is unconstrained by a limited therapeutic window (Kostrzewa et al., 2015).

From the time that BoNT was revealed to be a Zn2+ metalloprotease (Schiavo et al., 1992), efforts have focused on developing small molecule inhibitors (SMIs) targeting the protease activity of the BoNT LCs (Adler et al., 1998; Anne et al., 2001; Eubanks et al., 2010; Šilhár et al., 2013a; Duplantier et al., 2016; Bremer et al., 2017). Despite considerable effort, development of suitable drug candidates with significant in vivo efficacy has not been achieved. This is due in part to the size and conformational flexibility of the BoNT active site and to the extensive binding interactions between BoNT/A LC (LC/A) and SNAP-25 (Chen et al., 2007; Bremer et al., 2017). Thus, crystal structure data suggest that the active site of LC/A has a great deal of conformational flexibility, making the design of highly potent SMI inhibitors challenging (Silvaggi et al., 2007; Kumaran et al., 2015; Harrell et al., 2017). Further complicating a small molecule approach is the presence of ancillary binding sites (exosites) that contribute to the tight binding of SNAP-25 to LC/A (Chen et al., 2007; Xue et al., 2014). The enzyme-substrate interface that encompasses the active site plus α- and β-exosites has been determined to be ca. 4,840 Å2 (Breidenbach and Brunger, 2004), an area that would require the cooperative action of multiple inhibitors.

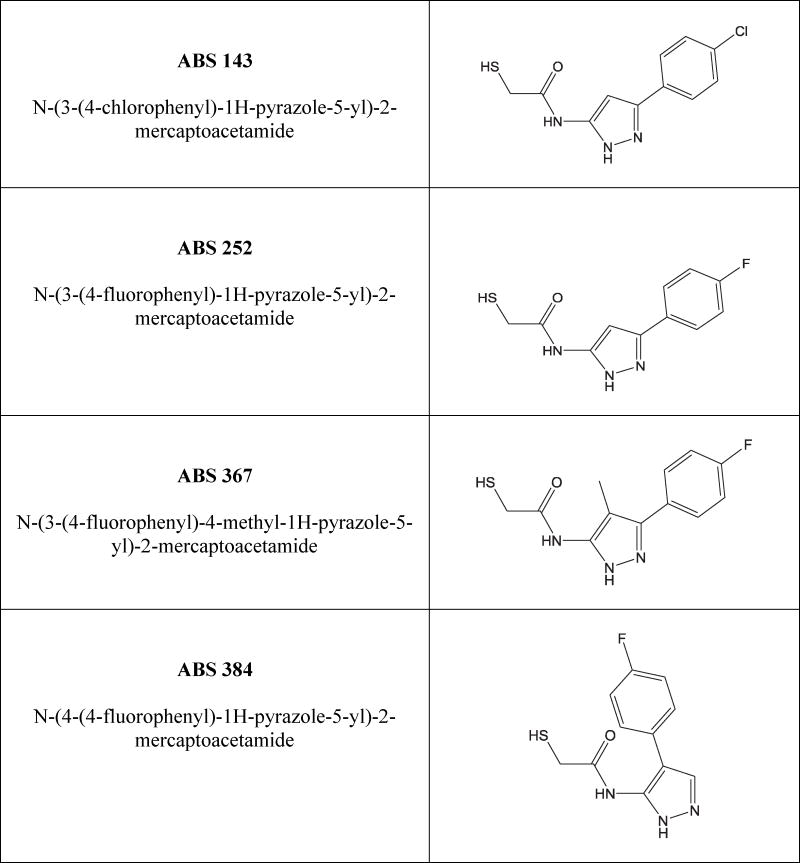

An examination of some known active-site inhibitors led to the suggestion of a three-zone pharmacophore model as optimal for inhibitor-LC binding (Hermone et al., 2008). However, since the substrate binding cleft of LC/A is unusually large, inhibitors with surface areas >200 Å2 may be required for effective interaction with the active site cavity (Segelke et al., 2004). This is clearly beyond the purview of a typical SMI (Pang et al., 2009; Kumaran et al., 2015; Harrell et al., 2017). In this study, we report on the efficacy of the mercaptoacetamide inhibitor ABS 252 in enzymatic and biological assays and assess its ability to extend survival of mice in vivo. In addition, we examine the complex between LC/A and related mercaptoacetamides ABS 143, ABS 367 and ABS 384 (Fig. 1) by X-ray crystallography to elucidate their interactions with the active site of LC/A. ABS 252 was found to be effective in all assays of BoNT action and produced a significant delay in time-to-death (TTD) when administered to mice challenged with BoNT/A in vivo.

Fig. 1.

Structure of ABS compounds examined in this study. Each analog in this series interacts with the catalytically important Zn2+ in the LC/A active site via its sulfur atom.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemistry

The rationale and design strategy for the ABS compounds and their synthetic routes have been reported elsewhere (Moe et al., 2009). For animal protection experiments, the compounds were recrystallized from warm toluene at least 3 times, and each compound was > 99% pure with no single impurity accounting for > 0.25% based on NMR and HPLC spectra. Unless stated otherwise, stock solutions of ABS compounds were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and contained 10 mM inhibitor plus 20 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA); the latter served to protect the sulfhydryl warhead from undergoing spontaneous oxidation (Winther and Thorpe, 2014). Since ABS compounds have limited aqueous solubility (Moe et al., 2009), preparation of working solutions was made by slow addition (30 sec) of DMSO stocks into stirred aqueous solutions at 37 °C.

BoNT/A holotoxins with specific toxicity of 2.7 x 108 mouse intraperitoneal (i.p.) LD50 units (U) per mg were obtained from Metabiologics, Inc. (Madison, WI, USA). BoNTs were received in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.0) at a concentration of 6.66 μM. Stock solution was diluted to 100 nM with 0.9% saline containing 0.1% gelatin, aliquoted in single use vials and stored frozen at −20 °C.

2.2. X-ray structure determination

BoNT/A LC was expressed in E. coli as a C-terminal truncation mutant (residues 1- 425) with an N-terminal His6-tag and thrombin cleavage site and purified as described (Silvaggi et al. 2007). Purified BoNT/A LC425 was crystallized by mixing equal volumes of protein solution (10–12 mg/ml LC425, 50 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM EDTA, pH 6.5) and crystallization buffer (10–15% polyethylene glycol [PEG] 2,000 monomethyl ester, 0.2–0.3 M K2HPO4, 0.1 M D,L-malic acid pH 7.0) in the hanging-drop geometry. Clusters of needle and plate-shaped crystals appeared in 2–4 days, reaching a maximum size of 0.2 x 0.4 mm after 7 days. Crystal morphology was improved by microseeding. Crystal structures of the enzyme-inhibitor complexes were obtained by soaking the largest, thickest plates available in solution containing 25% PEG 2,000 monomethyl ester, 0.3 M K2HPO4, 0.1 M D,L-malic acid, 5 mM Zn(NO3)2, 5 mM TCEP, 2.5% DMSO, and 2.5 mM inhibitor (ABS 143, ABS 252, ABS 367 or ABS 384).

Data for the LC/A:ABS 143 complex were collected on a Rigaku Rotaflex RU-H X-ray diffractometer equipped with osmic mirrors and an R-AXIS IV++ image plate detector located at Boston University School of Medicine. Data for the LC/A:ABS 367 and LC/A:ABS 384 complexes were collected at Beamline X29 of the National Synchrotron Light Source, Brookhaven National Laboratory. The structures were determined by molecular replacement using the high-resolution unliganded structure (PDB ID: 3BON) (Silvaggi et al., 2008) as the search model, with waters, Zn2+ and flexible loops (residues 245–258 and 367–373) removed. The resulting models were refined in phenix.refine from the PHENIX suite (Adams et al, 2002) with riding hydrogen atoms (without contribution to Fcalc) and TLS (translation/libration/screw) using groups suggested by TLSMD (TLS motion determination) analysis (Painter and Merritt, 2006) (3 groups for chain A and 5 for chain B). After rebuilding parts of the protein model and adding ordered solvent molecules, the inhibitor molecules were modeled into unambiguous difference electron density (contoured at 2.5 – 3.0σ). The quality of the final models was confirmed by MolProbity (Davis et al., 2004). Data collection and refinement statistics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Crystallographic data and model quality statistics

| BoNT/A- LC:ABS 143 | BoNT/A- LC:ABS 367 | BoNT/A- LC:ABS 384 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Space group | P 21 | P 21 | P 21 |

| Unit cell dimensions | |||

| a, b, c (Å); ß(°) | 73.2, 67.3, | 73.0, 67.6, | 73.2, 67.4, |

| 98.1; 105.6 | 98.0; 105.2 | 97.8; 105.0 | |

| Resolution (Å)a | 50.00–2.50 (2.59–2.50) | 50.00–2.05 (2.12–2.05) | 50.00–1.90 (1.97–1.90) |

| Rsymm | 0.096 (0.616) | 0.089 (0.339) | 0.078 (0.322) |

| I/σI | 16.0 (2.3) | 11.3 (2.1) | 12.9 (2.6) |

| Completeness | 99.6 (99.7) | 95.9 (76.1) | 94.9 (76.0) |

| Multiplicity | 3.4 (3.2) | 3.4 (2.4) | 3.6 (2.8) |

| Resolution (Å) | 18.33–2.50 | 37.52–2.05 | 29.48–1.90 |

| No. of reflections | 29,263 | 53,284 | 67,754 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.210/0.253 | 0.225/0.268 | 0.175/0.222 |

| No. of non-H atoms | |||

| Protein | 6484 | 6348 | 6574 |

| Ligands/ions | 36 | 38 | 36 |

| Solvent | 119 | 364 | 345 |

| Ave. B factors (Å2) | |||

| Protein | 53.4 | 37.1 | 46.2 |

| Ligands/ions | 73.1 | 50.8 | 56.4 |

| Solvent | 44.2 | 43.2 | 43.7 |

| R.M.S. deviations | |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.003 | 0.009 | 0.016 |

| Bond angles (º) | 0.592 | 1.142 | 1.444 |

2.3. BoTest® A/E Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) assay

Fluorescence measurements were made on a Spectramax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). To determine inhibitor efficacy, we performed kinetic studies using truncated LC/A 425 or full-length LC/A 448 and the FRET reporter CFP-SNAP-25141-206-YFP (BoTest® A/E; BioSentinel Pharma, Madison, WI, USA). Reactions were carried out in triplicate using 96-well opaque black Microfluor 1 plates (ThermoFisher) in buffer containing 50 mM HEPES pH 7.1, 0.1% Tween-20, 10 μM ZnCl2 and 0.15% glycerol. ABS 252 and ABS 143 were pre-incubated with LC/A 425 (500 pM) or LC/A 448 (60 pM) at 37 °C for 15 min to ensure enzyme-inhibitor equilibrium.

To initiate cleavage, BoTest® (0.1 μM) was added, and kinetic measurements were performed at 1 min intervals. LC/A-mediated reductions in FRET/CFP ratio were plotted as a function of time, and IC50 values were obtained via least-squares nonlinear regression fits (GraphPad Prism, La Jolla, CA, USA). Conversion of IC50 to Ki was made using a public domain IC50-to-Ki-converter (Cer et al., 2009) with a previously established Km for the BoTest® substrate of 0.7 μM (Ruge et al., 2011).

2.4. Primary rat cerebellar neuron assay

2.4.1. Culture conditions

Neuronal granule cells from pooled cerebella of either 7- or 8-day-old Sprague-Dawley rats (SNAP-25 cleavage assay) or 5- to 7-day-old CD-1 mice (aspartate release assay) were harvested by methods previously described (Skaper et al., 1979). Cells were cultured in DMEM/F-12 media (Gibco-Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing 50 U/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin, 10% fetal bovine serum and N2 supplement. Cells were seeded onto poly-L-lysine-coated 24-well plates at a density of 1 x 105 cells per well and cultured in a humidified atmosphere of 93% air/7% CO2 at 37 °C. After 24 h, 10 μM cytosine arabinoside (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to inhibit the replication of non-neuronal cells. The media was replaced by 75% after 24 h, and completely each week thereafter.

2.4.2. Cell-based protection studies

Primary cerebellar cells were used 8 – 30 days post-seeding. Two strategies were used to determine efficacy of ABS 252 against BoNT/A: 1) ABS 252 was added to cells followed immediately by 500 pM BoNT/A, and cells were assayed for SNAP-25 cleavage 4 h later; 2) cells were exposed to 50 pM BoNT/A for 30 min, washed with PBS to remove unbound neurotoxin, cultured overnight in medium containing ABS 252 and assayed for SNAP-25 cleavage.

To determine the degree of protection of SNAP-25 afforded by ABS 252, cells were washed with PBS, harvested into pre-weighed Eppendorf screw cap vials and pelleted by centrifugation. Cells were lysed by M-PERTM (Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent; ThermoFisher), solubilized in SDS-PAGE sample buffer and boiled for 10 min prior to immunoblotting.

2.4.3. SNAP-25 immunoblot analysis

Aliquots of primary neuronal extract were resolved by SDS-PAGE on 12% polyacrylamide gels, and proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA, USA). The membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in TBST buffer (10 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20) for 30 min at room temperature and probed with rabbit anti-SNAP-25 antibody (1:5000, Sigma-Aldrich) in TBST by gentle rocking for at least 1 h at room temperature. The secondary antibody incubation was for 1 h with horse radish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:50,000). Blots were washed and developed using enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Marlborough, MA, USA). Band densities for intact and 197-mer truncated SNAP-25 were normalized, and the relative intensity was determined by scanning densitometry.

2.4.4. [3H]D-aspartate release assay

Mouse primary cerebellar neuronal cells were used 10 – 15 days post-seeding. Cells were pretreated with 40, 50 or 60 μM ABS 252 for 30 min. BoNT/A (50 pM) was then added to the media, and cells were incubated overnight. Cells were washed with PBS (3-times) and incubated at 37 °C with 0.2 μCi/ml [3H]D-aspartate in Krebs-Ringer-HEPES-glucose (K-R-g) medium (Sigma-Aldrich). After a 30-min loading period, cells were washed with control K-R-g medium (3-times), and baseline release of [3H]D-aspartate was measured.

K-R-g medium containing 25 mM KCl was subsequently added for determination of depolarization-dependent release of [3H]D-aspartate. Aliquots of K-R-g media were removed at 3-min intervals over 21 min and analyzed for radioactivity to obtain the time course for evoked release. Finally, the radiolabel remaining in the cells was determined by scraping the cell monolayer in 1 ml of scintillation cocktail with 10% bleach. Cells were incubated with this mixture for 10 min to inactivate BoNT/A prior to isotope counting. [3H]D-aspartate released in the presence of 25 mM KCl was calculated as a percentage of total radioactivity: (dpm released divided by total dpm) minus baseline.

2.5. Hemidiaphragm muscle tension assay

Experiments were performed on hemidiaphragm muscles dissected from male CD-1 mice (20–25 g). Mice were housed in Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) International accredited facilities with food and water available ad libitum as described previously (Adler et al., 2011). To obtain isolated muscle preparations, the animals were euthanized by an overdose of isoflurane and decapitated. Hemidiaphragms with attached phrenic nerves were dissected, mounted in temperature-controlled tissue baths and immersed in Tyrode’s solution (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37 °C. The solution was bubbled with a gas mixture of 95% O2 / 5% CO2 and had a pH of 7.3. The phrenic nerve was stimulated continually at 0.03 Hz with 0.2 msec supramaximal (6 V) pulses. Muscle twitches were measured with Grass FT03 isometric force displacement transducers (Astro-Med, Inc., West Warwick, RI, USA), digitized and analyzed off-line with pClamp software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Resting tensions were maintained at 1.0 g to obtain optimal nerve-evoked tensions.

Because no SMI has shown efficacy as a posttreatment drug in BoNT-intoxicated nerve-muscle preparations, ABS-252 was evaluated as a pretreatment. Accordingly, muscles were pretreated with ABS 252 (10 or 100 μM) for 30 min prior to challenge with BoNT/A (5 pM), and twitch tensions were recorded until they fell by ≥50%. Control hemidiaphragm muscles were pretreated with vehicle used for dissolving 100 μM ABS 252 (1% DMSO plus 200 μM TCEP) for 30 min, exposed to 5 pM BoNT/A, and monitored concurrently for changes in twitch tension.

2.6. In situ contractions in rat extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscle

In situ EDL muscle tension measurements were performed on male Sprague Dawley Crl:CD (SD)IGS BR rats (300–350 g) from Charles River housed under an approved AAALAC International program (Adler et al., 2011). Local intramuscular (i.m.) injections were performed under isoflurane-oxygen anesthesia (3% isoflurane for induction, 2% for maintenance). After determining adequacy of anesthesia, a small incision was made in the skin on the dorsal surface of the ankle region over the left EDL muscle to allow for injections under direct visual guidance. ABS 252 (10 mM) and TCEP (20 mM) were dissolved in a 1:1 mixture of DMSO:PBS (v/v). TCEP was neutralized to pH 7.4 with NaOH to prevent muscle necrosis at the injection site and was prepared immediately before use for maximal stability (Zhao et al., 2013).

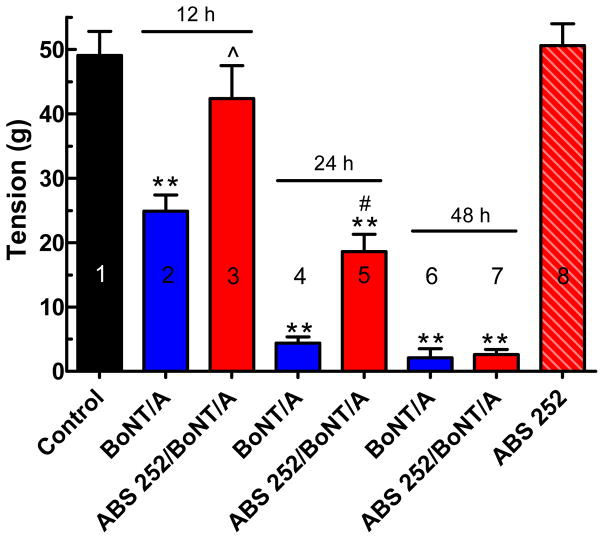

In groups designated as 3, 5, 7 & 8 in Fig. 6, 30 μl of ABS-252 was injected i.m. into the hindlimb between the anterior tibialis and EDL muscles using a 26 gauge needle attached to a Hamilton syringe. Groups 2, 4 & 6 were injected in a similar fashion with a 30 μl solution of 20 mM TCEP dissolved in 1:1 DMSO:PBS (vehicle for ABS 252). PBS was included to minimize local toxic action of neat DMSO (Gad et al., 2006).

Fig. 6.

EDL muscle tensions recorded in situ under the indicated conditions. Muscles were pretreated with 30 μl ABS 252 (10 mM) (3, 5 &7) or vehicle (1:1 DMSO:PBS plus 20 mM TCEP) (2, 4 & 6) 1 h before local i.m. injection of BoNT/A (4 U, 15 μl); tensions were recorded at 12, 24 and 48 h after toxin exposure. Tensions in muscles pretreated with ABS 252 and injected with BoNT/A vehicle 1-h later (0.9% saline plus 0.1% gelatin) (8) were recorded at 12, 24 and 48 h after vehicle administration (n = 4 at each time point) and pooled. Symbols represent the mean ± SEM of data from 8 - 12 EDL muscles per condition. **Differs significantly from tension recorded in control (1) or ABS 252 pretreated muscle (8): P < 0.001; ^differs significantly from tensions recorded in BoNT/A-injected muscles at 12 h: P <0.05; #differs significantly from tensions in BoNT/A-injected muscles at 24 h: P <0.05.

Injections were made near the point of insertion of the peroneal nerve to the EDL muscle to optimize drug delivery to presynaptic terminals. ABS 252 and vehicle administration were followed 1 h later with an injection of 4 U of BoNT/A in a volume of 15 μl, after which the skin incision was closed with VetbondTM surgical glue (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA). Right EDL muscles received either no treatment (Group 1), or were pretreated with ABS 252 followed 1 h later by a 15 μl injection of 0.9% saline containing 0.1% gelatin (vehicle for BoNT/A) (Group 8).

To prepare rats for measurement of tension, animals were anesthetized with an isoflurane-oxygen mixture. The peroneal nerve was isolated, and the tendon of the EDL was freed at its distal insertion. The rat was placed in a stereotaxic frame (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA, USA) with knee and ankle immobilized. Surgical areas were covered with mineral oil to prevent tissues from drying, and body temperature was maintained by use of a thermostatically controlled heating pad.

Tension measurements were performed at 12, 24 or 48 h, as described earlier (Adler et al., 2001). The distal tendon of the EDL was attached to a Grass FT03 isometric force displacement transducer (Astro-Med, Inc., West Warwick, RI, USA), and the peroneal nerve was stimulated at 6.5 V for 0.2 msec via a bipolar stainless steel electrode using a Grass S88 stimulator (Astro-Med). Resting tensions were maintained at 5 g, and muscles were allowed to equilibrate for 15 min prior to recording. Tension measurements were performed in duplicate and averaged. Outputs from the transducers were amplified, digitized and analyzed using pClamp software (Molecular Devices). At the end of the recordings, rats were euthanized with Fatal-PlusTM without regaining consciousness (Vortech Pharmaceuticals, Dearborn, MI, USA).

2.7. In silico modeling

In silico modeling was used to obtain information about the pharmaceutical properties of ABS 252, such as aqueous solubility, logP (1-octanol/water partition coefficient), polar surface area, molar refractivity and plasma protein binding. The calculations were performed using programs from the Biotechnology High Performance Computing Software Applications Institute (BHSAI) (http://bhsai.org/) and Chem3D Pro (CambridgeSoft Corporation Software).

2.8. Effect of ABS 252 on BoNT/A-mediated time-to-death (TTD)

Protection studies were carried out on CD-1 mice at the University of Wisconsin Food Research Institute. ABS 252 was dissolved in 100% DMSO at 20 mg/ml and diluted 1:1 (v/v) in PBS. Compound solubility was marginal under these conditions; however, higher concentrations of DMSO were not well tolerated by the mice. To minimize precipitation of test compound, only enough ABS 252 was prepared to inject 5–7 mice, after which the solution was discarded and more compound was prepared for the next group of animals.

Mice were assigned randomly to vehicle or experimental groups. For drug or vehicle administration, animals were briefly restrained, and 0.1 ml of ABS 252 (1 mg) or vehicle (1:1 DMSO:PBS) was administered intravenously (i.v.) into the left lateral tail vein. After 5 min, mice were challenged by i.p. injection (0.5 ml) of 10 U of BoNT/A.

2.9. Data analysis

Data analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc tests except for the TTD studies (Table 4), where data analysis was performed using the Student’s t-test (GraphPad Prism). Significance was defined as P ≤ 0.05.

Table 4.

ABS 252 delays TTD in mice challenged by BoNT/A1

| Treatment group | Control2 TTD ±SEM (min) | ABS 2523 TTD ± SEM (min) | Ratio | P value (t-test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 701 ± 65 | 1061 ± 78 | 1.51 | <0.0002 |

| B | 754 ± 55 | 967 ± 49 | 1.28 | < 0.02 |

Mice in group A (n = 10) were injected i.v. with 0.1 ml of a 10 mg/ml solution of ABS 252 and challenged 5 min later with an i.p. injection of BoNT/A (10 U). Mice in group B (n = 5) were administered 0.1 ml of a 10 mg/ml solution of ABS 252 (i.v.) and challenged 5 min later by 10 U BoNT/A (i.p.). An additional 0.2 ml of ABS 252 was injected i.p. 60 min post-intoxication. The i.p. route was chosen for the second ABS 252 dose to maintain the selected dose interval, which was more difficult with i.v. tail vein injections.

Control mice were injected with vehicle (1:1 DMSO:PBS) in place of ABS 252 but were otherwise treated identically as the ABS 252 group.

A similar study at Metabiologics yielded comparable results.

3. Results

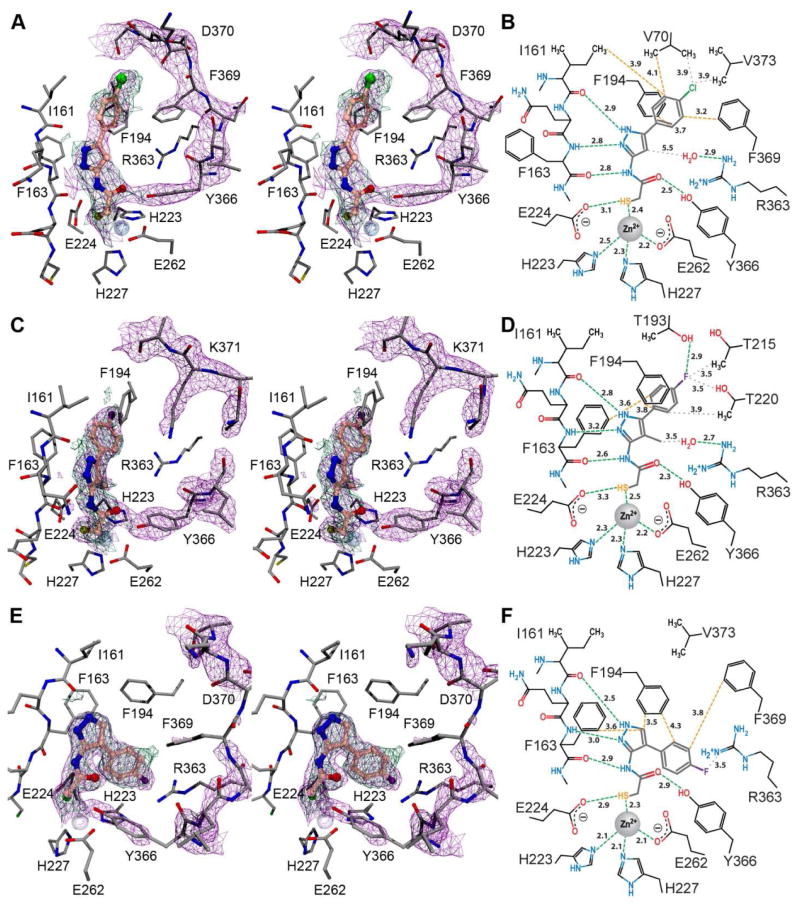

3.1. X-ray crystallography

X-ray crystal structures of the complexes between the LC/A and ABS 252, as well as the analogs ABS 143, ABS 367 and ABS 384, were determined to elucidate the binding mode of this class of compounds, and to identify parts of the scaffold that might be modified to improve binding and/or inhibitory activity. Since the chemical structures of ABS 252 and ABS 143 are similar (p-fluoro and p-chloro, respectively; Fig. 1), and their complexes with LC/A were essentially identical, we only report on the LC/A:ABS 143 complex here because its crystal structure was of superior quality. As expected from the structures of complexes with other metal-chelating SMIs of LC/A (Silvaggi et al., 2007), these inhibitors bind in the protease active site, primarily through interaction with the catalytic Zn2+ (Fig. 2). The sulfur of ABS 143 directly chelates the Zn2+ and replaces the Zn2+-bound water molecule that is required for catalysis of SNAP-25. The monodentate (2.5 Å) interaction between the inhibitor sulfur and Zn2+ has a geometry typical of Zn2+-sulfur interactions (Chakrabarti, 1989).

Fig. 2.

Stereo (A) and schematic (B) views of the active site in the LC/A:ABS 143 complex. In the stereoview, the inhibitor is rendered with orange carbon atoms, LC/A is depicted in grey and Zn2+ is shown as a metallic silver sphere. The 2|Fo|−|Fc| electron density contoured at 1.0σ is shown as magenta mesh for the inhibitor and 370 loop. The simulated annealing omit electron density map, also contoured at 1.0σ, is shown as green mesh for the inhibitor. In the schematic, interactions are labeled with the distance in Å and are colored green for hydrogen bonds and metal ligands and yellow for hydrophobic interactions. Lightly dotted grey lines are used for reference and do not indicate formal interactions. Panels C and D show the same pair of diagrams for the LC/A:ABS 367 structure, and panels E and F show corresponding views for the LC/A:ABS 384 structure. Panels A, C and E were rendered using the POVScript+ modification of MOLSCRIPT and POVRay (Kraulis, 1991; Fenn et al., 2003).

Thus, like almost all small-molecule and peptidic LC/A inhibitors studied to date, ABS 143 (and by extension ABS 252) and its analogs act by (1) competing with SNAP-25 for access to the active site and (2) disabling the catalytic center by displacing the nucleophilic water molecule from the Zn2+ coordination sphere. ABS 143/252 makes additional, specific interactions with the LC/A active site. These can be divided into two groups that localize to two distinct regions of the scaffold. The first group consists of three hydrogen bonds between the mercaptoacetamide and pyrazole nitrogens with the backbone of a ß-strand that forms one wall of the catalytic site (residues I161-F163, Fig. 2A & B). The second group consists entirely of hydrophobic contacts between the substituted phenyl ring and a hydrophobic pocket formed by residues V70, I161, F194, F369 and V373.

Notably, these same residues (with the exception of F369) form part of the S1' subsite that binds the P1' Arg of SNAP-25. Specificity is derived from the combination of all three sets of interactions between inhibitor and LC: Zn2+ coordination, hydrogen bonding (pyrazole moiety), and hydrophobic interactions (phenyl ring). While the enzyme active site is highly dynamic and accommodates a wide variety of substrate analogs and inhibitors (Park et al., 2006; Burnett et al., 2007; Silvaggi et al., 2007), there are tight constraints on the distance between the Zn2+-chelating group (the warhead) and the hydrophobic pocket, as well as on the size of the pocket. Thus, structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies and existing structural data show that analogs of ABS 143/252 with large substituents at the para position of the phenyl ring are weak inhibitors of the LC/A, because the hydrophobic pocket, though flexible, cannot accommodate groups bulkier than a single atom.

In the structures of the ABS 143 and ABS 252 complexes with LC/A, a water molecule remains bound to R363 approximately 5.5 Å from the pyrazole rings of the bound inhibitors. To evaluate the possibility of adding functionality to the pyrazole ring by displacing this water molecule and making an additional interaction with R363, we determined the structure of LC/A with ABS 367 in the active site (Figure 2C & D). This compound has a methyl group at C4 of the pyrazole ring. Given the amount of space around this atom in the LC/A:ABS 143 complex structure, the addition caused a surprising alteration in the binding mode of ABS 367. The mercaptoacetamide sulfur atom still chelates Zn2+, but the presence of the methyl group on the pyrazole ring causes it to twist in the active site by ~65° relative to the LC/A:ABS 143 structure.

This twist does not prevent the mercaptoacetamide and pyrazole nitrogens from making the same set of hydrogen bonds observed in the LC/A:ABS 143 complex; however, their geometry is somewhat distorted. As a result of the pyrazole twist, the phenyl ring is buried deeper in the active site and occupies a new pocket formed by F163, T193, F194, T215 and T220. R363 is approximately 4.0 Å from the edge of the phenyl ring of ABS 367; thus the Arg moiety encloses the pocket but does not make any direct interactions with the inhibitor. The pyrazole methyl group of ABS 367 is directed toward a sizable pocket that may, in future designs, accommodate additional functionalities at this position. The R363-bound solvent molecule is still present in the LC/A:ABS 367 complex approximately 3.5 Å from the pyrazole methyl group. It is possible that the scaffold might be modified to (1) more fully occupy this space and (2) make direct interactions with R363. Thus, it may be possible to substantially improve the interactions between ABS 367 and active site residues.

This assertion is supported by the structure of LC/A with the 4-phenylpyrazole inhibitor ABS 384 (Fig. 2E & F). ABS 384 binds with the pyrazole ring at approximately the same angle as ABS 367 but is forced slightly closer to the wall of the active site (residues I161-F163). The phenyl ring is bound in a pocket defined by H223, E224, R363, E351, F369 and T220. In the LC/A:ABS 384 complex, R363 is in a different conformation from that in the ABS 143 structure, leading to displacement of the water molecule that was retained in the ABS 143 and ABS 367 complexes. The ABS scaffold is well suited for design of inhibitor candidates that can interact with diverse active site moieties of LC/A.

3.2. Effect of ABS 252 and ABS 143 on BoNT/A LC enzymatic activity

ABS 252 and ABS 143 were tested in a FRET assay with the commercially available reporter BoTest® A/E and either truncated LC/A 425 or full-length LC/A 448 (Table 2). The former was used since it is a crystallizable form of the LC, and the latter, because its sensitivity to inhibitors resembles that of BoNT/A holotoxin (Kumaran et al., 2015). ABS 252 and ABS 143 were found to be approximately equipotent in inhibiting the protease activity of each respective LC/A, as expected from their structural similarity (Table 2). Moreover, both compounds showed a higher affinity for the truncated LC/A 425 compared to the full-length LC/A 448.

Table 2.

ABS 252 and ABS 143 inhibits cleavage of the FRET reporter BoTest®.

| Inhibitor | BoNT/A LC | Ki (μM) | 95% Confidence Interval (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABS 143 | 425 | 10.2 | 7.8 – 19.1 |

| 448 | 79.5 | 53.3 – 118.7 | |

| ABS 252 | 425 | 13.7 | 9.3 – 18.6 |

| 448 | 72.9 | 55.7 – 96.3 |

Each inhibitor was preincubated with 500 pM LC/A 425 or 60 pM LC/A 448 for 15 min at 37 °C prior to addition of BoTest® reporter. Data were obtained from 3 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate.

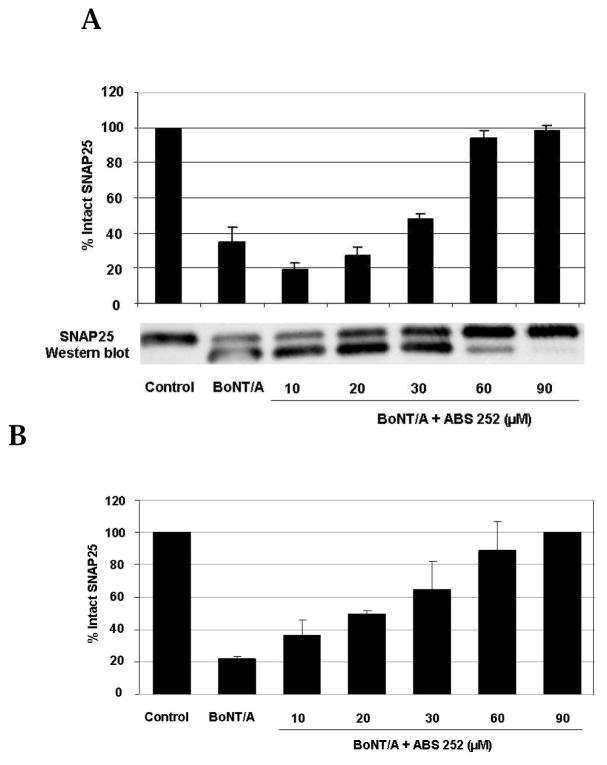

3.3. Efficacy of ABS 252 in primary cerebellar cultures

3.3.1 SNAP-25 cleavage

The ability of ABS 252 to antagonize BoNT/A was evaluated in primary neurons prepared from mouse and rat cerebella. Initial assays tested the potency of ABS 252 in preventing proteolytic cleavage of SNAP-25 when drug was added to primary neurons either before addition of toxin (pre-intoxication) or after cells had been exposed to toxin (post-intoxication). As shown in Fig. 3A, concentrations of ≥30 μM ABS 252 applied immediately prior to intoxication with 500 pM BoNT/A resulted in reduced levels of SNAP-25 cleavage when assessed 4 h after toxin exposure. The level of inhibition approached 100% with concentrations of 60 or 90 μM ABS 252.

Fig. 3.

ABS 252 inhibits BoNT/A-mediated SNAP-25 cleavage in primary rat cerebellar neurons. (A) Neurons were incubated in growth media (Control) or in media containing 500 pM BoNT/A for 4 h. ABS 252 was added at the indicated concentrations immediately prior to BoNT/A. Cells were harvested, and Western blotting was performed for SNAP-25 detection. Data are the mean ± SEM of 3 experiments. The inset shows a typical blot. (B) Neurons were incubated in growth media (Control) or in media containing 50 pM BoNT/A for 30 min. Cells were washed to remove unbound BoNT/A, and fresh media containing ABS 252 was added at the indicated concentrations. Cells were harvested after overnight incubation, and SNAP-25 cleavage was assessed by Western blotting as described for panel (A).

Similar results were obtained when ABS 252 was applied to primary neurons after intoxication. As shown in Fig. 3B, concentrations of ≥10 μM ABS 252 antagonized BoNT/A-mediated SNAP-25 cleavage in neurons that had been exposed to 50 pM BoNT/A for 30 min and then washed before ABS 252 was added. The potency of ABS 252 was consistently greater in the post-intoxication assay, possibly due to the lower toxin concentration used.

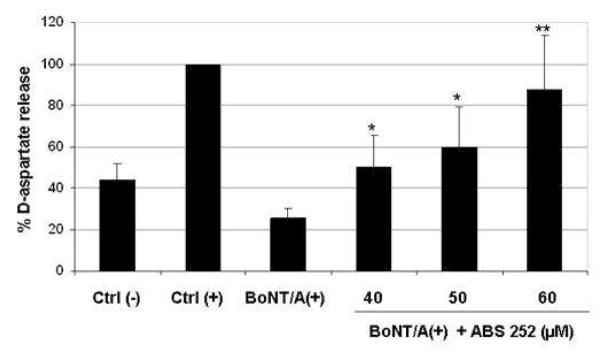

3.3.2 Transmitter release assay

To establish that ABS 252 was able to counteract the inhibitory action of BoNT/A on transmitter release, we employed an 3[H]D-aspartate release assay in primary mouse cerebellar cultures. As shown in Fig. 4, inhibition of aspartate release by BoNT/A was antagonized by ABS 252 in a concentration-dependent fashion. The highest concentration of ABS 252 (60 μM) almost completely prevented the inhibitory action of BoNT/A on high K+-evoked release of 3[H]D-aspartate (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

BoNT/A-mediated inhibition of evoked 3[H]D-aspartate release is antagonized by ABS 252. Primary mouse cerebellar neurons were cultured for 24 h in control media, in media containing 50 pM BoNT/A, or in media containing 50 pM BoNT/A plus 40, 50 or 60 μM ABS 252. Cells were subsequently washed and exposed to 3[H]D-aspartate for 30 min. Fresh media containing 5.4 mM KCl Ctrl (−) or 25 mM KCl (all other groups) were added, and release of 3[H]D-aspartate was measured under the indicated conditions. Release of 3[H]D-aspartate in control cells exposed to 25 mM KCl [Ctrl (+)] was taken as 100% and used to normalize the relative percent of 3[H]D-aspartate released in the other samples. Data represent the mean ± SEM of 3 experiments. Differs significantly from high K+- evoked release in cells exposed to BoNT/A in the absence of ABS 252 [BoNT/A (+)]: * P ≤0.01; ** P <0.001.

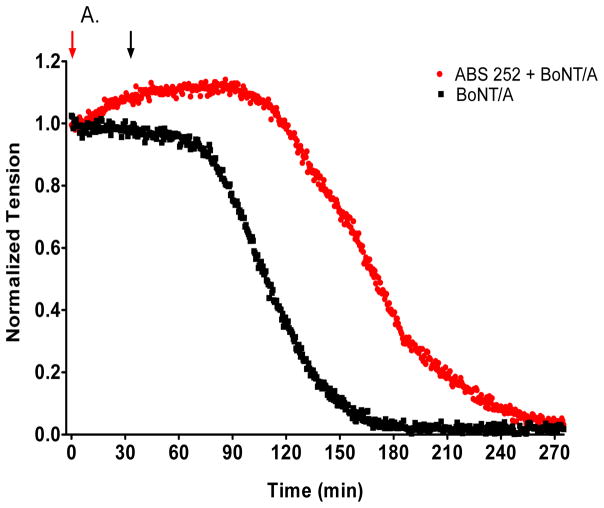

3.4. Effect of ABS 252 on mouse hemidiaphragm nerve-muscle preparations

Twitch tensions in control mouse diaphragm muscles ranged from 2.6 to 5.2 g (mean ± SEM = 3.4 ± 0.24 g, n = 16) and remained stable for at least 8 h of continuous recording. Addition of 5 pM BoNT/A led to a gradual decline of tension after a 45–60 min latency (Fig 5A), culminating in near complete muscle paralysis within 3 h of addition: half-time = 94.8 ± 6.7 min, n = 8 (Fig. 5B) (1).

Fig. 5.

Effect of ABS 252 pre-treatment on isolated mouse phrenic nerve-hemidiaphragm muscles intoxicated with 5 pM BoNT/A at 37 °C. A. Time course of a representative experiment; 0-time on the abscissa denotes time of addition of 100 μM ABS 252 (red arrow), and BoNT/A addition is denoted by the black arrow. The inhibitor was added to the muscle bath from concentrated DMSO stock solutions. B. Half-paralysis times under the indicated conditions; bars represent mean ± SEM (n = 6 - 8). At 10 μM, ABS 252 showed no protection (3), but at 100 μM (4) the inhibitor caused a significant prolongation in BoNT/A-mediated half-paralysis time relative to that of non-pretreated control muscle (1) or to vehicle pretreated muscle (2),**P <0.001. The vehicle consisted of 1% DMSO plus 200 μM TCEP. The 5 pM bath concentration of BoNT/A corresponds to 203 U/ml.

The ability of ABS 252 to protect hemidiaphragms from the paralytic action of BoNT/A was determined by pretreating muscles with 10 or 100 μM ABS 252 for 30 min followed by challenge with 5 pM BoNT/A. As shown in Fig. 5B, 10 μM ABS 252 was unable to ameliorate the paralytic action of BoNT/A (3). However, raising the concentration of ABS 252 to 100 μM caused a prolongation of the half-paralysis time to 139.3 ± 10.8 min (4), which was statistically significant (P < 0.01). The vehicle for this concentration of ABS 252 (1% DMSO plus 200 μM TCEP) had no effect on muscle tension under the present experimental conditions (data not shown) and did not alter the inhibitory action of BoNT/A (2) (Fig. 5B).

Higher concentrations of ABS 252 were not examined in this assay due to problems with solubility of the inhibitor in Tyrode’s solution. In addition, DMSO concentrations above 1% often produced spontaneous muscle fasciculation’s which were generally followed by a sustained reduction of twitch tension.

3.5. Effect of ABS 252 on in situ tensions in rat EDL muscle

Since isolated nerve-muscle preparations have limited viability following excision, they require high concentrations of BoNT/A to allow evaluation of candidate therapeutic agents. Thus, it is not possible to determine whether the action of ABS 252 can be sustained over time in excised hemidiaphragm muscle. However, nerve-muscle preparations in which BoNT is injected locally (to avoid systemic toxicity), and in which tensions are recorded in situ, are better suited to answer this question. Accordingly, ABS 252 was evaluated in rat EDL muscle in situ. EDL muscles were injected locally with 30 μl of a 1:1 DMSO/PBS solution containing 10 mM ABS 252 and 20 mM TCEP 1 h before local injection of 4 U of BoNT/A (15 μl). Other EDL muscles were untreated (1), or served to control for possible injection-induced muscle alterations or for potential pharmacological action of the vehicles used for preparation of ABS-252 or BoNT/A solutions. Muscle tensions in response to peroneal nerve stimulation were determined in situ 12, 24 and 48 h after pretreatment (Adler et al., 1996; 2001). As shown in Fig. 6, a local injection of BoNT/A (4 U) produced a marked decline of nerve-evoked contraction in EDL muscle. By 12 h after injection of BoNT/A, tensions were reduced to 50.7 ± 5.1% of control (2). Tensions continued to decline, reaching 8.9 ± 2.0% (4) and 4.3 ± 2.8% (6) of control, respectively, at 24 and 48 h after exposure to BoNT/A.

The paralytic action of BoNT/A was antagonized by ABS 252, which was especially pronounced at the earliest time point. Thus, muscles injected locally with ABS 252 1 h before BoNT/A exhibited tensions of 86.4 ± 10.4% of control after a 12-h exposure to 4 U of BoNT/A (3). However, by 24 h, tensions in the ABS 252- pretreated muscle were reduced to 37.9 ± 5.4% of control (5), and by 48 h (7), tensions reached levels similar to those observed in muscles exposed to BoNT/A in the absence of ABS 252 (6). As expected, muscles pretreated with ABS 252 and challenged 1-h later with BoNT/A vehicle (0.9% saline containing 0.1% gelatin) showed no decrement in tension (8). The concentration of ABS 252 used for local injections were constrained by the need to maintain solubility of both ABS 252 and TCEP in the vehicle used; the relatively low volume of 30 μl was selected to avoid necrotic lesions of the EDL and surrounding muscles from the local i.m. injection (Treadwell, 2003).

3.6 ABS 252 in silico predictions

Because of their extremely high potency, extraordinary persistence and intracellular localization, few candidate BoNT inhibitors have been able to protect animals from the lethal actions of the neurotoxin. However, based on the efficacy of ABS 252 in primary neurons and in muscle preparations, it was of interest to examine the inhibitor for possible in vivo efficacy. Since neither pharmacokinetic nor ADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion) data exist for this compound, we performed in silico modeling to obtain estimates of pharmaceutical properties relevant to its suitability as an in vivo drug candidate. The results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

In silico predictions of pharmaceutical properties for ABS 252

| 1 Properties | Values |

|---|---|

| LogS (aqueous solubility) | −3.6 (251 μM) |

| LogP | 2.7 |

| Plasma protein binding | 64% bound |

| Polar surface area | 53.5 Å2 |

| Formal charge | 0 |

| H-bond donor/acceptor | 3/4 |

| Molar refractivity | 65.7 cm3/mol |

| Molecular weight | 251.1 Da |

| Number of rotatable bonds | 3 |

Determined with BHSAI or Chem3D Pro software

As shown in Table 3, the aqueous solubility and plasma protein binding of ABS 252 was predicted to be 251 μM and 64%, respectively, making ABS 252 a reasonable candidate for studies of in vivo efficacy against BoNT/A intoxication. The in silico results suggest that with a sufficiently high dose, it may be possible for ABS 252 to reach a free plasma concentration of 90 μM (251 μM x 0.36), which is in the range found effective in primary cerebellar cells (Figs. 3 & 4) and in isolated diaphragm preparations (Fig. 5). In addition, the absence of a formal charge at physiological pH (Table 3) would enable ABS 252 to penetrate biological membranes and allow it to reach the LC/A in the nerve terminal cytosol. ABS-252 has other desirable attributes for “drug-likeness” such as a polar surface area ≤140 A2, a molar refractivity of 40 to 130 cm3/mol and ≤10 rotatable bonds. ABS 252 also conforms to Lipinski’s rule of five: logP (≤5) hydrogen bond donors (≤5), hydrogen bond acceptors (≤10) and molecular weight ≤500 D (Leeson, 2012).

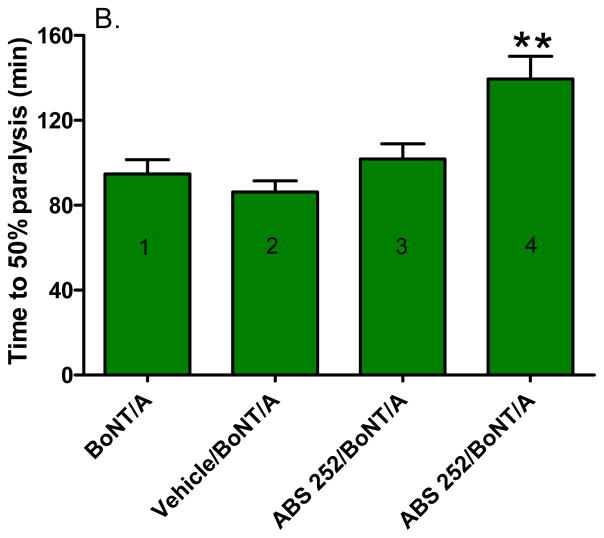

3.7. Effect of ABS 252 on survival times

Although ABS 252 did not protect animals from lethality, it was able to delay the TTD in BoNT/A-intoxicated mice. As shown in Table 4, ABS 252-pretreated animals survived challenge by 10 U of BoNT/A considerably longer than did control animals. The low aqueous solubility of ABS 252 precluded administering higher doses of drug; however, even with this limitation, ABS 252 showed a significant ability to delay the lethal actions of the neurotoxin (Table 4).

Interestingly, as indicated by the difference in the TTD ratio between group A and B, administration of two doses of ABS 252 appeared to reduce the efficacy of the inhibitor, suggesting that the dose and/or schedule of ABS 252 were not optimal. The reduced efficacy of the two-dose regimen may be due to toxicity of ABS 252 or possibly of DMSO. Further, in experiments where ABS 252 was initially given i.p. followed by a second i.p. dose 1-h later, no protection was observed (data not shown), implying that the more rapid i.v. route may be required for protecting animals against a 10 U challenge of BoNT/A. In addition, the i.p. route may have reduced the bioavailability of ABS 252 due to first pass metabolism.

4. Discussion

In spite of the intense search for active site inhibitors of BoNT, especially of serotype A, development of SMIs targeted against the LC protease activity of the BoNTs has proven difficult. Complicating discovery efforts are findings that potency against the isolated LC depends on factors such as C-terminal truncation of the LC and the length of the substrate used in enzymatic assays (Baldwin et al., 2004). A similar observation was recently reported by Kumaran et al. (2015). Interestingly, their cyclic peptide inhibitor showed a higher potency against full-length LC/A relative to the more commonly used truncated forms (1–425 aa or 1–429 aa). In the current study, ABS compounds were found to be more potent in inhibiting truncated LC/A 425 by a factor of 5.3 for ABS 252 and 7.8 for ABS 143 (Table 2). This is in accord with the general preference of SMIs for inhibiting truncated LCs. Šilhár et al. (2013b) proposed that the additional 23 C-terminal residues in LC/A 448 increases the conformational flexibility of the active site, which reduces the binding affinity for SMIs. Although full-length LC/A 448 is clearly the more relevant target for BoNT/A inhibitor studies, it is less often used since the recombinant enzyme in solution has a tendency to form dimers and to undergo autocatalysis (Šilhár et al., 2013b; Mizanur et al., 2013).

In a study using peptide-like inhibitors, Zuniga et al. (2010) noted that their model of a pseudo-peptide bound to LC/A could not account for the observed SAR seen in enzyme assays, suggesting that the model for the LC/A developed from the crystal structure may not represent the physiologically relevant enzyme conformation with respect to inhibitor binding modes. In addition, Pang et al. (2009) were unable to improve on the potency of their lead compound based on the model they derived, while Roxas-Duncan et al. (2009) reported on the computer-aided development of an inhibitor that shows low micromolar activity against the isolated enzyme and that, surprisingly, was found to have even greater cellular potency with an EC50 of 500 nM. ABS 252 also exhibited only modest potency in the cell-free FRET assay (Table 2), but relatively high activity in the more relevant cell-based (Fig. 3 & 4) and nerve-muscle assays (Figs. 5 & 6).

To rationalize the observed difficulties in developing SMIs against BoNT/A, we suggest that LC/A within the cell may have significant structural differences relative to the forms of the enzyme used in cell-free activity assays. Consequently, the enzyme inhibition and crystallography data alone may not be capable of providing a clear pathway for the development of an effective SMI therapeutic. Apparently, there are enough differences between the overall three-dimensional conformation of the endogenous enzyme relative to those of the recombinant LCs that a classical developmental approach may not work. Whether this phenomenon is related to the endogenous enzyme being membrane-bound (Shoemaker and Oyler, 2013) or to post-translational modifications of the LC by host mechanisms (Ferrer-Montiel et al., 1996) remains to be established. However, caution is warranted when trying to draw too detailed of a conclusion from the SAR. The present study reinforces the idea that an integrated approach to the development of inhibitors for the clostridial neurotoxins is necessary (Boldt et al., 2006; Bremer et al., 2017). Efficacy in an enzyme inhibition assay should not be used as the sole criterion to eliminate a given scaffold or compound, and additional studies should be undertaken concurrently before determining the usefulness of the inhibitor.

The unusually high potency and long duration of action of BoNT/A, coupled with the intracellular localization of LC/A impose severe constraints on the discovery of effective inhibitors of BoNT/A intoxication (Adler et al., 2014). The above may account for the finding that no SMIs examined to date have been able to provide robust protection from BoNT/A-induced lethality. Thus, a single inhibitor targeting only one aspect of the complex mechanism of BoNT action may not be adequate to treat botulism (Simpson, 2013). This realization has led to consideration of alternative strategies for treatment of botulism. Among the promising emergent candidates, two are especially noteworthy: 1) atoxic BoNT constructs (Vazquez-Cintron et al., 2017) capable of intracellular delivery of a broad range of inhibitors (e.g., highly potent camelid antibodies that target the active site of the LC (Tremblay et al., 2010); 2) selective inhibitors for the deubiquitinating enzyme VCIP135/VCPIP1, which is largely responsible for the neuronal persistence of LC/A (Tsai et al., 2017). It is envisioned that an effective strategy for future treatment of BoNT/A intoxication will consist of one or more SMIs and/or potent camelid antibodies delivered by recombinant atoxic BoNTs to effectively inhibit LC/A and deubiquitinase inhibitors to accelerate its degradation.

5. Conclusions

Owing to the potential use of BoNT as a bioterrorism/biowarfare agent, coupled with the difficulties in the medical management of outbreaks and the absence of a specific drug treatment, a post exposure BoNT therapeutic is clearly needed. Development of an SMI for LC/A has been hampered by a number of factors, including the extended binding pocket of the enzyme (Segelke et al., 2004; Zuniga et al., 2010; Kumaran et al., 2015) and the disparate results obtained from different biological assays. In this study, we found that in spite of the relatively low potency of ABS 252/143 in enzymatic assays, the compounds were effective in the more complex biological assays. Most importantly, ABS 252 was able to show significant protection in a TTD animal model. Moreover, the X-ray crystal structure of ABS 252/143 and related compounds provides insights for building onto the existing scaffold. ABS 252 represents one of the few SMIs against LC/A that shows efficacy across a variety of biological assays as well as significant activity in an in vivo TTD model. In addition, in silico modeling suggests that ABS 252 has desirable pharmaceutical properties and conforms to Lipinski’s rule of five in terms of its molecular weight, logP, number of hydrogen bond donors and number of hydrogen bond acceptors (Leeson, 2012). As such, it is a promising candidate for developing as a small molecule therapeutic against botulinum intoxication.

Highlights.

ABS 143 and ABS 252 inhibited the proteolytic activity of BoNT/A light chain.

Inhibition involved specific interactions with active site groups in the light chain.

ABS 252 antagonized BoNT/A-mediated cleavage of SNAP-25 in primary neurons.

ABS 252 slowed onset of paralysis in BoNT/A-intoxicated nerve-muscle preparations.

ABS 252 delayed time-to-death in mice intoxicated by BoNT/A.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by NIH Contract No. N01-AI-30050 (ST) and an award from DTRA-JSTO, Medical S & T Division, award No. CB4080 (MA). The authors would like to thank Joseph Barbieri (Medical College of Wisconsin and Leonard Smith (USAMRIID) for their generous supply of truncated BoNT/A LC425 and full-length BoNT/A LC448, respectively. We also thank Dr. Kim Janda and Dr. Sean O’Malley for helpful discussions and Mr. Richard Sweeney with carrying out the in silico studies

Abbreviations

- ADME

absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion

- BAT®

heptavalent botulism antitoxin

- BHSAI

Biotechnology High Performance Computing Software Applications Institute

- BoNT

botulinum neurotoxin

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- EDL

extensor digitorum longus

- FRET

Förster resonance energy transfer

- HC

BoNT heavy chain

- LC

BoNT light chain

- LC/A

BoNT/A light chain

- M-PERTM

mammalian protein extraction reagent

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- SAR

structure-activity relationship

- SMI

small molecule inhibitor

- SNAP-25

synaptosome-associated protein of 25 kDa

- SNARE

soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor

- TCEP

tris (2-carboxyethyl)phosphine

- TLS

translation/libration/screw

- TLSMD

TLS motion determination

- TTD

time-to-death

- U

mouse intraperitoneal LD50 unit

- VAMP1/2

vesicle-associated membrane protein isoforms 1 or 2.

Footnotes

Disclaimer

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of Army, Department of Defense, or U.S. Government.

The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the USAMRICD and all procedures were conducted in accordance with the principles stated in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the Animal Welfare Act of 1966 (P.L. 89-544), as amended.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics statement

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams PD, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Hung LW, Ioerger TR, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, et al. PHENIX: building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2002;58:1948–1954. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler M, Gul N, Eitzen E, Oyler G, Molles B. Prevention and treatment of botulism. In: Foster KA, editor. Molecular Aspects of Botulinum Neurotoxin, Current Topics in Neurotoxicity. Vol. 4. Springer; New York: 2014. pp. 291–342. [Google Scholar]

- Adler M, Keller JE, Sheridan RE, Deshpande SS. Persistence of botulinum neurotoxin A demonstrated by sequential administration of serotypes A and E in rat EDL muscle. Toxicon. 2001;39:233–243. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(00)00120-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler M, Macdonald DA, Sellin LC, Parker GW. Effect of 3,4-diaminopyridine on rat extensor digitorum longus muscle paralyzed by local injection of botulinum neurotoxin. Toxicon. 1996;34:237–249. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(95)00127-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler M, Nicholson JD, Cornille F, Hackley BE. Efficacy of a novel metalloprotease inhibitor on botulinum neurotoxin B activity. FEBS Lett. 1998;429:234–238. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00492-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler M, Sweeney RE, Hamilton TA, Lockridge O, Duysen EG, Purcell AL, et al. Role of acetylcholinesterase on the structure and function of cholinergic synapses: insights gained from studies on knockout mice. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2011;31:909–920. doi: 10.1007/s10571-011-9690-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anne C, Cornille F, Lenoir C, Roques BP. High throughput fluorogenic assay for determination of botulinum type B neurotoxin protease activity. Anal Biochem. 2001;291:253–261. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin MR, Bradshaw M, Johnson EA, Barbieri JT. The C-terminus of botulinum neurotoxin type A light chain contributes to solubility, catalysis and stability. Protein Expr Purif. 2004;37:187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay S, Clark AW, DasGupta BR, Sathyamoorthy V. Role of the heavy and light chains of botulinum neurotoxin in neuromuscular paralysis. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:2660–2663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasi J, Chapman ER, Link E, Binz T, Yamasaki S, De Camilli P, et al. Botulinum neurotoxin A selectively cleaves the synaptic protein SNAP-25. Nature. 1993;365:160–163. doi: 10.1038/365160a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldt GE, Eubanks LM, Janda KD. Identification of a botulinum neurotoxin A protease inhibitor displaying efficacy in a cellular model. Chem Comm (Camb) 2006:3063–3065. doi: 10.1039/b603099h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breidenbach MA, Brunger AT. Substrate recognition strategy for botulinum neurotoxin serotype A. Nature. 2004;432:925–929. doi: 10.1038/nature03123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremer PT, Adler M, Phung CH, Singh AK, Janda KD. Newly designed quinolinol inhibitors mitigate the effects of botulinum neurotoxin A in enzymatic, cell- based and ex vivo assays. J Med Chem. 2017;60:338–348. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett JC, Ruthel G, Stegmann CM, Panchal RG, Nguyen TL, Hermone AR. Inhibition of metalloprotease botulinum serotype A from a pseudo-peptide binding mode to a small molecule that is active in primary neurons. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:5004–5014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608166200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai S, Singh BR. Strategies to design inhibitors of Clostridium botulinum neurotoxins. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2007;7:47–57. doi: 10.2174/187152607780090667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cer RZ, Mudunuri U, Stephens R, Lebeda FJ. IC50-to-Ki: a web-based tool for converting IC50 to Ki values for inhibitors of enzyme activity and ligand binding. Nucleic Acids Research. 2009;37(Web Server issue):W441–W445. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti P. Geometry of interaction of metal ions with sulfur-containing ligands in protein structures. Biochemistry. 1989;28:6081–6085. doi: 10.1021/bi00440a052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Kim JJ, Barbieri JT. Mechanism of substrate recognition by botulinum neurotoxin serotype A. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:9621–9627. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611211200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng LW, Stanker LH, Henderson TD, II, Lou J, Marks JD. Antibody protection against botulinum neurotoxin intoxication in mice. Infect Immun. 2009;77:4305–4313. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00405-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colasante C, Rossetto O, Morbiato L, Pirazzini M, Molgó J, Montecucco C. Botulinum neurotoxin type A is internalized and translocated from small synaptic vesicles at the neuromuscular junction. Mol Neurobiol. 2013;48:120–127. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8423-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowner BE, Brunstrom JE, Racette BA. Iatrogenic botulism due to therapeutic botulinum toxin A injection in a pediatric patient. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2007;30:310–313. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e31804b1a0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DasGupta BR, Sugiyama H. Role of protease in natural activation of Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin. Infect Immun. 1972;6:587–590. doi: 10.1128/iai.6.4.587-590.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis IW, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. MOLPROBITY: structure validation and all-atom contact analysis for nucleic acids and their complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Web Server issue):W615–W619. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolly JO, Ashton AC, McInnes C, Wadsworth JD, Poulain B, Tauc L, et al. Clues to the multi-phasic inhibitory action of botulinum neurotoxins on release of transmitters. J Physiol (Paris) 1990;84:237–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duplantier AJ, Kane CD, Bavari S. Searching for therpeutics against botulinum neurotoxins: a true challenge for drug discovery. Curr Top Med Chem. 2016;16:2330–2349. doi: 10.2174/1568026616666160413135630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eubanks LM, Silhár P, Salzameda NT, Zakhari JS, Xiaochuan F, Barbieri JT, et al. Identification of a Natural product antagonist against the botulinum neurotoxin light chain protease. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2010;1:268–272. doi: 10.1021/ml100074s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenn TD, Ringe D, Petsko GA. POVScript+: a program for model and data visualization using persistence of vision ray-tracing. J Appl Crystallogr. 2003;36:944–947. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer-Montiel AV, Canaves JM, DasGupta BR, Wilson MC, Montal M. Tyrosine phosphorylation modulates the activity of clostridial neurotoxins. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:18322–18325. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gad SC, Cassidy CD, Aubert N, Spainhour B, Robbe H. Nonclinical vehicle use in studies by multiple routes in multiple species. Int J Toxicol. 2006;25:499–521. doi: 10.1080/10915810600961531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell WA, Jr, Vieira RC, Ensel SM, Montgomery V, Guernieri R, Eccard VS, et al. A matrix-focused structure-activity and binding site flexibility study of quinolinol inhibitors of botulinum neurotoxin serotype A. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2017;27:675–678. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermone AR, Burnett JC, Nuss JE, Tressler LE, Nguyen TL, Šolaja BA, et al. Three-dimensional database mining identifies a unique chemotype that unites structurally diverse botulinum neurotoxin serotype A inhibitors in a three-zone pharmacophore. ChemMedChem. 2008;3:1905–1912. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200800241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbs RG, Weber JT, Corwin A, Allos BM, El Rehim MSA, El Sharkawy S, et al. Experience with the use of an investigational F(ab')2 heptavalent botulism immune globulin of equine origin during an outbreak of type E botulism in Egypt. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:337–340. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.2.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SE, Iqbal R, Cadiz CL, Le J. Foodborne botulism treated with heptavalent botulism antitoxin. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47:e12. doi: 10.1345/aph.1R646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostrzewa RM, Kostrzewa RA, Kostrzewa JP. Botulinum neurotoxin: Progress in negating its neurotoxicity; and in extending its therapeutic utility via molecular engineering. Peptides. 2015;72:80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraulis P. MOLSCRIPT: a program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J Appl Crystallogr. 1991;24:946–950. [Google Scholar]

- Kumaran D, Adler M, Levit M, Krebs M, Sweeney R, Swaminathan S. Interactions of a potent cyclic peptide inhibitor with the light chain of botulinum neurotoxin A: Insights from X-ray crystallography. Bioorg Med Chem. 2015;23:7264–7273. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeson P. Drug discovery: Chemical beauty contest. Nature. 2012;481:455–456. doi: 10.1038/481455a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizanur RM, Frasca V, Swaminathan S, Bavari S, Webb R, Smith LA, et al. The C terminus of the catalytic domain of type A botulinum neurotoxin may facilitate product release from the active site. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:24223–24233. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.451286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moe ST, Thompson AB, Smith GM, Fredenburg RA, Stein RL, Jacobson AR. Botulinum neurotoxin serotype A inhibitors: Small-molecule mercaptoacetamide analogs. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009;17:3072–3079. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery VA, Ahmed SA, Olson MA, Mizanur RM, Stafford RG, Roxas-Duncan VI, et al. Ex vivo inhibition of Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin types B, C, E, and F by small molecular weight inhibitors. Toxicon. 2015;98:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Münchau A, Bhatia KP. Uses of botulinum toxin injection in medicine today. BMJ. 2000;320:161–165. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7228.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Painter J, Merritt EA. Optimal description of a protein structure in terms of multiple groups undergoing TLS motion. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:439–450. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906005270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang YP, Vummenthala A, Mishra RK, Park JG, Wang S, Davis J, et al. Potent new small-molecule inhibitor of botulinum neurotoxin serotype A endopeptidase developed by synthesis-based computer-aided molecular design. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7730. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JG, Sill PC, Makiyi EF, Garcia-Sosa AT, Millard CB, Schmidt JJ, et al. Serotype-selective, small-molecule inhibitors of the zinc endopeptidase of botulinum neurotoxin serotype A. Bioorg Med Chem. 2006;14:395–408. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravichandran E, Gong Y, Al Saleem FH, Ancharski DM, Joshi SG, Simpson LL. An initial assessment of the systemic pharmacokinetics of botulinum toxin. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;318:1343–1351. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.104661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossetto O, Pirazzini M, Montecucco C. Botulinum neurotoxins: genetic, structural and mechanistic insights. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12:535–549. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roxas-Duncan V, Enyedy I, Montgomery VA, Eccard VS, Carrington MA, Lai H, et al. Identification and biochemical characterization of small-molecule inhibitors of Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin serotype A. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:3478–3486. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00141-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruge DR, Dunning FM, Piazza TM, Molles BE, Adler M, Zeytin FN. Detection of six serotypes of botulinum neurotoxin using fluorogenic reporters. Anal Biochem. 2011;411:200–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiavo G, Rossetto O, Benfenati F, Poulain B, Montecucco C. Tetanus and botulinum neurotoxins are zinc proteases specific for components of the neuroexocytosis apparatus. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;710:65–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb26614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiavo G, Rossetto O, Santucci A, DasGupta BR, Montecucco C. Botulinum neurotoxins are zinc proteins. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:23479–23483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segelke B, Knapp M, Kadkhodayan S, Balhorn R, Rupp B. Crystal structure of Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin protease in a product-bound state: Evidence for noncanonical zinc protease activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 2004;101:6888–6893. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400584101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki H, Xue S, Hixon MS, Pellett S, Remes M, Johnson EA, et al. Toward the discovery of dual inhibitors for botulinum neurotoxin A: concomitant targeting of endocytosis and light chain protease activity. Chem Commun (Camb) 2015;51:6226–6229. doi: 10.1039/c5cc00677e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker CB, Oyler GA. Persistence of botulinum neurotoxin inactivation of nerve function. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2013;364:179–196. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-33570-9_9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla HD, Sharma SK. Clostridium botulinum: a bug with beauty and weapon. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2005;31:11–18. doi: 10.1080/10408410590912952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šilhár P, Lardy MA, Hixon MS, Shoemaker CB, Barbieri JT, Struss AK, et al. The C-terminus of botulinum A protease has profound and unanticipated kinetic consequences upon the catalytic cleft. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2013b;4:283–287. doi: 10.1021/ml300428s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šilhár P, Silvaggi NR, Pellett S, Čapková K, Johnson EA, Allen KN. Evaluation of adamantane hydroxamates as botulinum neurotoxin inhibitors: synthesis, crystallography, modeling, kinetic and cellular based studies. Bioorg Med Chem. 2013a;21:1344–1348. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvaggi NR, Boldt GE, Hixon MS, Kennedy JP, Tzipori S, Janda KD, et al. Structures of Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin serotype A light chain complexed with small-molecule inhibitors highlight active-site flexibility. Chem Biol. 2007;14:533–542. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvaggi NR, Wilson D, Tzipori S, Allen KN. Catalytic features of the botulinum neurotoxin A light chain revealed by high resolution structure of an inhibitory peptide complex. Biochemistry. 2008;47:5736–5745. doi: 10.1021/bi8001067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson LL. Identification of the major steps in botulinum toxin action. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;44:167–193. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson LL. The life history of a botulinum toxin molecule. Toxicon. 2013;68:40–59. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaper SD, Adler V, Varon S. A procedure for purifying neuron-like cells in cultures from central nervous tissue with a defined medium. Develop Neurosci. 1979;2:233–237. doi: 10.1159/000112485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treadwell T. Diagnostic dilemma: intramuscular injection site injuries masquerading as pressure ulcers. Wounds. 2003;15:302–312. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay JM, Kuo CL, Abeijon C, Sepulveda J, Oyler G, Hu X, et al. Camelid single domain antibodies (VHHs) as neuronal cell intrabody binding agents and inhibitors of Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT) proteases. Toxicon. 2010;56:990–998. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trott DL, Yang M, Gonzalez J, Larson AE, Tepp WH, Johnson EA, et al. Egg yolk antibodies for detection and neutralization of Clostridium botulinum type A neurotoxin. J Food Prot. 2009;72:1005–1011. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-72.5.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai YC, Kotiya A, Kiris E, Yang M, Bavari S, Tessarollo L, et al. Deubiquitinating enzyme VCIP135 dictates the duration of botulinum neurotoxin type A intoxication. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 2017 Jun 5; doi: 10.1073/pnas.1621076114. pii: 201621076. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez-Cintron EJ, Beske PH, Tenezaca L, Tran BQ, Oyler JM, Glotfelty EJ, et al. Engineering botulinum neurotoxin C1 as a molecular vehicle for intra-neuronal drug delivery. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42923. doi: 10.1038/srep42923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winther JR, Thorpe C. Quantification of thiols and disulfides. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1840:838–846. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Gu Y, Morphew MK, Yao J, Yeh FL, Dong M, et al. All three components of the neuronal SNARE complex contribute to secretory vesicle docking. J Cell Biol. 2012;198:323–330. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201106158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue S, Javor S, Hixon MS, Janda KD. Probing BoNT/A protease exosites: implications for inhibitor design and light chain longevity. Biochemistry. 2014;53:6820–6824. doi: 10.1021/bi500950x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu R, Wang S, Yu YZ, Du WS, Yang F, Yu WY, et al. Neutralizing antibodies of botulinum neurotoxin serotype A screened from a fully synthetic human antibody phage display library. J Biomol Screen. 2009;14:991–998. doi: 10.1177/1087057109343206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao DS, Gregorich ZR, Ge Y. High throughput screening of disulfide-containing proteins in a complex mixture. Proteomics. 2013;13:3256–3260. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201300242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuniga JE, Hammill JT, Drory O, Nuss JE, Burnett JC, Gussio R, et al. Iterative structure-based peptide-like inhibitor design against the botulinum neurotoxin serotype A. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11378. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]