Abstract

Accumulating evidence suggests the idea that chronic inflammation may play a critical role in various malignancies including bladder cancer and long-term treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is significantly effective in reducing certain cancer incidence and mortality. However, the molecular mechanisms leading to malignant transformation and the progression of bladder cancer in a chronically inflammatory environment remain largely unknown. In this review, we will describe the role of inflammation in the formation and development of bladder cancer and summarize the possible molecular mechanisms by which chronic inflammation regulates cell immune response, proliferation and metastasis. Understanding the novel function orchestrating inflammation and bladder cancer will hopefully provide us insights into their future clinical significance in preventing bladder carcinogenesis and progression.

Keywords: inflammation, tumorigenesis, development, bladder cancer

INTRODUCTION

Chronic inflammation has been recognized as one of the hallmarks of cancer. In early 1989, Rudolf Virchow hypothesized that cancer originated from the sites of chronic inflammation [1]. Since then, a large amount of studies investigated the association between the inflammatory microenvironment of malignant tissues and cancer prevention or treatment, and accumulating evidence has supported Virchow's hypothesis [2, 3]. Inflammation is an essential host defense mechanism for cell or organism injury in response to stresses, by which the immune system tries to neutralize or eliminate injurious stimuli and initiate regenerative or healing processes. However, excessive or persistent inflammation is also shown to contribute to carcinogenesis and tumor progression by activating a series of inflammatory molecules and signals [4, 5].

Bladder cancer (BCa) is the fourth most common cancer among men and the ninth overall in the world [6]. Males are more likely to develop BCa than females. When diagnosed, 90% of bladder cancers are urothelial carcinomas, whereas the remaining 10% are mostly squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and adenocarcinomas [7]. Many risk factors contribute to the malignant transformation and the progression of bladder cancer, including smoking, heavy alcohol consumption and occupational exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons or aromatic amines [8, 9]. Besides these risk factors, chronic inflammation is recently recognized as another risk factor for BCa [10].

Recent studies have linked inflammation with the formation and development of bladder cancer. On the one hand, chronic inflammation, whether systemic or local, increases the risk of developing BCa. On the other, the oncogenic changes may induce a chronically inflammatory microenvironment which has many tumor-promoting effects on the cell proliferation, angiogenesis, invasion and metastasis of bladder cancer [11, 12]. However, the molecular pathways involved in inflammation-related bladder cancer still remain largely unexplained. Thus, there is an urgent need to understand the underlying molecular mechanisms on the possible role of chronic inflammation during bladder carcinogenesis. In this review we will summarize the different cellular and molecular signaling pathways regarding the relationship between chronic inflammation and bladder cancer promotion and progression, and discuss the attractive prospect of targeting inflammation as a revolutionary strategy for cancer prevention and therapy.

THE TRIGGERS OF CHRONIC BLADDER INFLAMMATION

Urinary tract infection

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are among the most common urologic diseases. About 80% of UTIs occur in women and 40–50% of females have at least one symptomatic infection during their lifetime [13]. The majority of UTIs are caused by Escherichia coli (80%) or Staphylococcus saprophyticus (10–15%) [14]. Previous epidemiological studies have reported a correlation between UTI and the increased risk of BCa. The majority of these studies show UTI not only increases the risk of BCa but also is associated with worse BCa outcomes, in both men and women [15–17]. However, there is a conflicting report regarding the potential role of UTI. Jiang et al. reported that a history of UTI was associated with a reduced risk of BCa among women [18]. Possible mechanisms that were involved in this paradox might be the cytotoxicity against BCa cells from the antibiotics commonly used to treat bladder infections. Recently, Vermeulen et al. investigated the association between UTI and the risk of BCa, and they found that regular cystitis was positively associated with the risk of BCa, whereas, those women with episodes of UTI treated with antibiotics have a decreased urinary bladder cancer (UBC) risk [19].

Schistosoma haematobium (S. haematobium), endemic in Africa and the Middle East, is a chronic infection caused by parasitic Schistosoma worms. There is strong evidence linking S. haematobium infection with increased bladder cancer incidence [20, 21]. In fact, S. haematobium is particularly relevant with squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder [22]. S. haematobium antigens have been observed to induce the development of urothelial dysplasia and inflammation [21]. In the experiment, S. haematobium was shown to have carcinogenic ability through enhanced c-KIT expression or oncogenic mutation of KRAS gene [23, 24]. The nuclear localization of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) was also involved in S. haematobium-mediated stem cell differentiation/proliferation in bladder carcinogenesis through upregulation of Oct3/4 expression [25]. In addition, p53 signaling seems to mediate urothelial malignant transformation during S. haematobium infection in a sex-specific manner, but it's not clear if p53 actually inhibits urothelial cell cycle progress and carcinogenesis in the setting of urogenital schistosomiasis [26, 27].

Human papilloma virus (HPV)

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection has been known as a risk factor for certain cancers such as cervical, anogenital, oropharyngeal carcinoma and skin cancers [28–30]. However, whether the virus might play a key role in the pathogenesis of BCa has not been well clarified. A number of studies have been done to elucidate this possibility. The meta-analysis from Li et al. reported that HPV infection were significantly associated with the increased risk of BCa [31]. However, a modified meta-analysis suggested limited biologic rationale for a role of HPV in BCa [32]. Kim et al. provided some evidence that HPV infection may be associated with squamous metaplasia of the bladder especially in non-smokers [33]. The work from Shigehara et al. showed that HPV may play an etiological role in the tumorigenesis of female BCa at younger patients with a past history of cervical cancer, however, no statistical difference was observed between high-risk HPV infection and histologic subtypes of BCa [34]. Currently, the molecular subtypes of BCa have been identified and HPV infection may have a role in the development of a small percentage of urothelial carcinoma patients with amplified and overexpressed BCL2L1 [35]. In summary, although a large number of research that has shown the presence of HPV in BCa, the results are far from conclusive.

Chronic chemical and mechanical irritations

It has been suggested that some chronic irritations of urinary tract are also risk factors for BCa. When bladder mucosa is persistently subjected to these chronic irritations, the urothelium tend to generate a high level of cell proliferation, resulting in many pathological changes such as dysplasia, metaplasia, carcinoma in situ and ultimately to invasive carcinoma [36, 37]. N-butyl-N-(4-hydroxybutyl) nitrosamine (BBN), an alkylating agent, is the most commonly-used chemical inducer of murine BCa model [38]. The uracil, a nongenotoxic chemical, can induce urinary bladder carcinomas in rats and mice, which was related to the presence of calculi in the urinary bladder and increased spontaneous mutations by vigorous cell proliferation [37, 39]. Long-standing bladder stones have been also implicated as a cause of urinary tract cancers [40, 41], however, the association between urinary stones and BCa is largely undefined. In addition, some foreign bodies such as pellets of paraffin wax, glass beads and wood chips were demonstrated to induce urothelial tumorigenesis [42–44]. Chronic indwelling urinary catheters (CIDCs) and augmentation cystoplasty are also considered as risk factors of BCa development, especially in older aged and male patients [45]. Augmentation cystoplasty is the gold standard treatment for the patients with congenital bladder abnormalities. The question is whether these patients have an increased risk of BCa. A number of early studies showed that the patients with surgical bladder augmentation had an increased risk of BCa [46, 47]. However, there are also conflicting reports regarding an increased risk of malignancy after augmentation cystoplasty. Higuchi, et al. explored the relationship between augmentation and cancer, and they found that augmentation did not appear to be an independent risk factor for the development of BCa [48, 49]. In order to clearly understand the relationship between augmentation cystoplasty and the formation of BCa, large-scale and multicenter collaboration will be necessary in the future.

INFLAMMATORY CELLS AND CYTOKINES IN TUMOR MICROENVIRONMENT OF BLADDER CANCER

The chronic inflammatory microenvironment in solid cancers is characterized by the presence of proinflammatory cells (such as macrophages, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, regulatory T cells, dendritic cells, mast cells, neutrophils and lymphocytes) and cytokines (such as tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukins) both in the supporting stroma and in tumor areas (Table 1). These chronic inflammatory cells and cytokines contribute to BCa formation and progression via multiple mechanisms (Figure 1).

Table 1. Inflammatory cells and cytokines in tumor microenvironment of bladder cancer.

| Class | Target | Biomarkers | Role in BCa | Histologic subtypes of BCa | Control | N | p value | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory cells | ||||||||

| TAMs | M1: TNF-α, IL | IL-8 | Inhibition | TCC | Patients without treatment | 12 | p<0.05 | 52 |

| M2: TGF-β, IL | CD163 | Promotion | TCC | Patients without treatment | 99 | p<0.05 | 54 | |

| MDSCs | PBMCs, IFN-γ | CD14(+)HLA-DR(-/low) | Promotion | TCC | Healthy human | 64 | p<0.01 | 64 |

| MCs | c-Kit | c-Kit | Promotion | TCC | Normal bladder mucosa | 78 | p<0.05 | 82 |

| Stem cell | ALDH1 | Inhibition | TCC | Healthy human | 52 | p<0.05 | 84 | |

| NLR | Unknown | NLR | Inhibition | TCC | NLR<2.7 | 899 | p<0.05 | 88 |

| Inflammatory cytokines | ||||||||

| TNF-α | MMP-9 | MMP-9 | Promotion | TCC | Without TNF-α | Cell lines | p<0.05 | 94 |

| ILs | Unknown | IL-1α | Inhibition | Main TCC | Low IL-1α expression | 164 | p<0.05 | 95 |

ALDH1, aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 A1; PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; TCC, Transitional cell carcinoma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

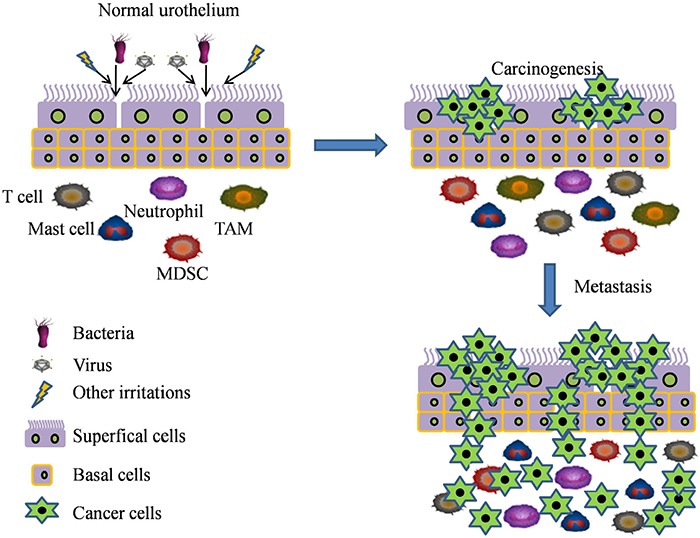

Figure 1. The inflammatory spectrum underlying the carcinogenesis and progression of bladder cancer.

Many factors such as infections (bacterial, S. haematobium, viral), proinflammatory cells (such as TAM, MDSC, T cells, mast cells and neutrophils), and chronic chemical or mechanical irritation are considered as a major risk factors of chronic inflammation. These factors can activate the inflammatory responses which contribute to the formation and development of bladder cancer.

Macrophages

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) play a dual role in BCa, depending on the different polarization states classified as M1 and M2 [50]. M1 macrophages can be induced by tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interferon-γ (IF-γ), interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, IL-23, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and show an inhibitory action in the initiation and/or progression of BCa (Table 1) [51, 52]. M2 macrophages are mainly activated by IL-4, IL-10, IL-13 or transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and associated with promotion of cancer cell proliferation, migration, invasion, metastasis and suppression of anti-tumor immune responses (Table 1) [53, 54].

Direct evidence for the role of TAM in the formation and development of BCa has recently been reported. OK-432, a streptococcus-derived anticancer immunotherapeutic agent, was demonstrated to suppress cell proliferation and metastasis through inducing M1 to secrete cytokines in BCa [55]. ATP-binding cassette transporter G1 (ABCG1) inhibited BCa growth through a phenotypic shift from a tumor-promoting M2 to a tumor-fighting M1 [56]. The predominance of M2-polarized macrophages in the stroma of low-hypoxic BCa was associated with Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) immunotherapy failure, possibly owing to immunosuppressive function of M2 [54]. Taken together, TAMs have been shown to be associated with carcinogenesis and progression of bladder, however, the molecular mechanisms that TAMs establish their tumor-inhibiting or tumor-promoting effect remain undefined.

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) originate from bone marrow or from peripheral lymphoid organs, and their presence is associated with disease progression and reduced survival in many types of tumors [57, 58]. Accumulating evidence shows that induction of MDSCs is an important immune-evading strategy for cancer cells, which is linked to their immunosuppressive activity and the capacity to impair T cell function [59, 60]. MDSCs suppress anti-tumor immunity through multiple mechanisms, including a high level of arginase or tryptophan activity as well as nitric oxide (NO), reactive oxygen species (ROSs) and prostaglandin E(2) (PGE(2)) induction [59, 61].

BCa is a highly immunogenic malignancy and MDSCs are demonstrated to be critical mediators of BCa cell-associated immune suppression. Bladder cancer tissues spontaneously produce MDSCs-attracting CXCL8 (IL-8) and CCL22, which are correlated with poor prognosis of BCa [62]. The increased tumor infiltration of MDSCs with concomitant decrease of T cells and NK cells are shown in tyrosine kinase Rip2-deficient mice model of BCa, resulting in an enhanced incidence of metastases in BCa [63]. CD14(+)HLA-DR(-/low) cells, as a new subpopulation of MDSCs, display strong T-cell suppressive activity, and are associated with gender, tumor size, number of tumors and disease progression in the patients with BCa (Table 1) [64]. Thus, MDSCs may be a potential target for the tumorigenesis, progression and treatment of BCa.

Regulatory T cells (Tregs)

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) play an essential role in the pathogenesis of inflammation and various autoimmune diseases, including cancer. Currently, numerous studies support the idea that Tregs can promote cancer progression by suppressing antitumor immune responses or expressing inflammatory cytokines [65, 66]. In bladder cancer, S1PR1 signaling in T cells can drive Treg accumulation in tumors through JAK/STAT3 activation, resulting in promoting BCa growth [67]. Moreover, the patients with bladder carcinoma show a relative enrichment of Tregs in peripheral blood compared with healthy controls [68, 69], and the suppression of Tregs contributes to an antitumor effect in an orthotopic BCa model [70]. However, the role of Tregs in chronically inflammatory environment of bladder cancer cells has not been explored.

Dendritic cells

Dendritic cells (DCs) are professional antigen-presenting cells, thus, they play a crucial role in both the induction of antigen-specific immunity and the maintenance of tolerance [71]. The impairment of myeloid DC (mDC) counts and monocyte-derived DC (MoDC) function are closely associated with proliferation of superficial transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder (STCCB) [72]. Tumor-infiltrating dendritic cells (TIDCs) exhibit an abnormal phenotype and impaired function to stimulate T cells [73, 74]. Numerous studies have suggested that TIDCs contribute to tumor escape from immune surveillance by suppressing antitumor immune responses, therefore promoting tumor development [75, 76]. The high level of CD83(+) mature TIDCs is associated with a increased risk of muscle-invasive BCa [77]. In contrast, Xiang et al. reported that TIDCs were inversely correlated with the degree of malignancy and prognosis of bladder transitional cell carcinoma (BTCC) and the decrease in the number of TIDCs could have important relation to tumor immune evasion and immune tolerance [78]. Thus, TIDCs may be risk factors for BCa.

Mast cells

Mast cells (MCs) are among potent proinflammatory cells that have been known to play an important role in variety of inflammation-associated diseases including cancer [79]. Several clinical studies suggested that MCs could influence the neoplasia and progression of BCa. The number of MCs within and around the tumor may be a useful prognostic indicator in patients with bladder carcinomas and MCs density is significantly higher in high-grade BTCC than low-grade BTCC [80, 81]. c-Kit positive MCs may contribute to tumor angiogenesis and play an important role in tumor invasion of the urinary bladder (Table 1) [82]. Recruited MCs in the tumor microenvironment are demonstrated to enhance bladder cancer metastasis through modulation of ERβ/CCL2/CCR2 EMT/MMP9 signals [83]. Whereas, stem cell marker-positive MCs are reduced in stroma of benign-appearing mucosa of BCa patients, indicating that MCs could be also involved in suppression of carcinogenesis (Table 1) [84]. However, the mechanisms of how mast cells influence the formation and progression of BCa are still unclear.

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) in peripheral blood samples has been indicated as a crucial indicator for the systemic inflammatory response [85] and the prognosis of some solid malignancies including BCa [11, 86, 87]. Elevated serum NLR level among BCa patients undergoing radical cystectomy (RC) is associated with significantly increased risk for disease recurrence and progression (Table 1) [88, 89]. NLR is also associated with pathological response (pathR) in muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) patients who receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NC) [90]. Although the large number of clinical evidence has linked NLR with BCa progression, the molecular events by which NLR promotes BCa development and tumor recurrence are not fully understood.

TNF-α

TNF-α is a key event for infectious disease and malignancy. The released TNF-α during inflammation is associated with the transformation of BCa due to induction of H2O2 [91]. The serum level of TNF-α is remarkably elevated in BCa patients with or without schistosomiasis infection, moreover, higher level of TNF-α is observed in T3 and T4 advanced-stage patients than T1 and T2 early-stage patients, indicating TNF-α level might contribute to the progression of BCa [92]. TNF-α gene promoter-308 A/G single nucleotide polymorphisms are recently found to be significantly associated with the tumor-invasive stage of BCa [93]. TNF-α is also implicated in promoting invasion and migration of BCa cells through stimulating the secretion of matrix metalloproteinases-9 (MMP-9) in the tumor microenvironment (Table 1) [94]. Taken together, TNF-α as a proinflammatory cytokine contributes to the formation and development of BCa.

Interleukins

As proinflammatory cytokines, interleukins (ILs) have been involved in cancer initiation and progression. Low levels of IL-1α mRNA expression are associated with an increased risk for BCa-specific death (Table 1) [95]. IL-6, a major trigger of the signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 (STAT3) signaling pathway, have been implicated in regulation of tumor growth and metastasis of BCa. IL-6 level is positively linked with angiogenesis and the clinical outcome of BCa [96]. Interestingly, there is a conflicting report regarding the potential role of IL-6. Tsui and colleagues found that IL-6 attenuated tumorigenesis and cell invasion in human bladder carcinoma cells [97]. IL-8 over-production is an important factor in monomethylarsonous acid [MMA(III)]-induced malignant transformation of urothelial cells [98]. Increased expression of IL-8 is also correlated with tumor recurrence and poor prognosis of BCa [99]. The same as IL-6, IL-17 has a dual role in BCa. IL-17 can promote tumor growth through an IL-6-Stat3 signaling pathway [100]. In contrast, Baharlou et al. reported that reduced IL-17 levels in peripheral blood could be used as indicators for worse prognosis of BCa patients [101]. Serum IL-18 levels were significantly higher in BCa patients when compared to the control subjects, however, the relationship between IL-18 and tumor progression need to be further determined [102]. Therefore, interleukins may promote or inhibit bladder carcinogenesis.

MOLECULAR BASIS OF CHRONIC INFLAMMATION IN INITIATION AND PROGRESSION OF BLADDER CANCER

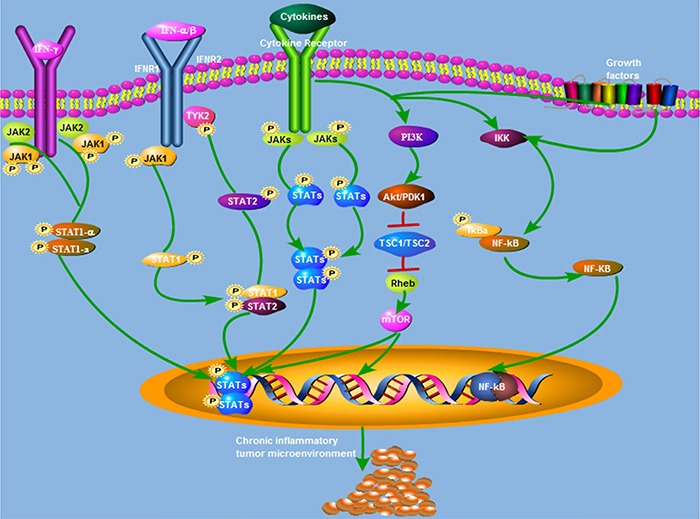

Several signaling pathways are known to be involved in the initiation and progression of BCa during inflammation, including Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2)/nitric oxide synthase (NOS), janus activated kinase (JAK)-STAT3, the nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB), and phosphoinositide-3 kinase (PI3K)-Akt-mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Summary of the signaling pathways underlying inflammatory response-mediated bladder cancer oncogenesis and progression.

CYCLOOXYGENASE-2/NITRIC OXIDE SYNTHASE (NOS)

Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), the enzyme that converts arachidonic acid to prostaglandin H2, is stimulated by a number of inflammatory cytokines and plays a key role in tumorigenesis and cancer progression. COX-2 is commonly expressed in BCa cells but not in normal urothelium [103]. Nuclear localization of COX-2 is significantly associated with inflammation-mediated stem cell proliferation/differentiation in bladder tumorigenesis [25]. The overexpression of COX-2 is involved in the development of squamous cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder [104]. The high COX-2 expression is significantly associated with advancing grade and T stage of STCCB [105]. Although numerous studies suggest that COX-2 promotes bladder tumorigenesis and progression, its precise role remains non-conclusive. The data from Tadin et al. showed an inverse correlation exists between COX-2 expression and recurrence of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) [106]. These results provide a pivotal role of COX-2 in the initiation and progression of BCa.

Nitric oxide (NO), generated by nitric oxide synthase (NOS), participates in the physiologic regulation of many diseases including cancer [107]. There are three NOS isoforms, endothelial (eNOS), neuronal (nNOS) and inducible (iNOS) [108]. NOS plays a role in simulating the pattern of fetal urothelium, which may be viewed as an oncofetal characteristic of this type of tumor [109]. Endogenously formed NO promotes cell proliferation in BCa cell lines [110]. NO generation from iNOS in the malignant epithelium and from eNOS in tumor stroma have an important potential in the angiogenesis of BCa [111]. However, the precise roles of NO and NOS of the inflammatory microenvironment in BCa carcinogenesis and progression remain to be defined.

JAK-STAT3

JAK-STAT3 is a crucial signal pathway for the pathogenesis and progression of various inflammatory diseases including cancer. JAKs are key participants in signaling networks fueled by a variety of cytokine and growth factor receptors in the tumor microenvironment, including IL-6, IL-11, IL-27, interferon (IFN-α/β/γ) oncostatin M (OSM), leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), epidermal growth factor (EGF) and others [112]. There are four JAK family members in mammalian cells, JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and TYK2. JAKs mediate intracellular signaling cascades principally through creating STAT docking sites via phosphorylation of tyrosine residue [113]. Once tyrosine is phosphorylated, STAT proteins are rapidly transported from the cytoplasm to the nucleus and bind to DNA elements to elicit transcriptional outputs in a specific cell or tissue [114]. STAT3 is a member of STAT family and its phosphorylation at Tyr705 or Ser727 is widely mediated in a variety of cellular contexts, especially JAK2 [115].

JAK-STAT3 pathway is also involved in chronic inflammation-mediated malignant transformation of urothelial cells and the progression of BCa. Stat3 activation contributes to bladder cancer cell growth and survival [116, 117]. By contrast, the silencing of STAT3 significantly suppresses proliferation of T24 BC cells both in vitro and in vivo [118]. Therefore, inhibition of JAK-STAT3 signaling pathway provides us a potential therapeutic approach for BCa. Along the same lines, the activation of JAK-STAT3 pathway in tumor inflammatory microenvironment participates in the invasion and migration of BCa. Stat3 activation in urothelial stem cells may lead to direct progression of urothelial progenitor cells to carcinoma in situ (CIS) formation and subsequent MIBC [119]. CXCR4-mediated Stat3 activation promotes CXCL12-induced cell invasion in BCa [120]. STAT3 is also phosphorylated by interacting with c-JUN, which is necessary for migration and invasion activity of T24 BCa cells [121]. Cytoplasmic p27 activates STAT3 to induce a TWIST1-dependent epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), resulting in increasing the invasion and metastasis of BCa [122]. Taken together, these reports have established a relationship between JAK-STAT3 pathway and inflammation-mediated bladder cancer.

NF-κB

NF-κB is a family of ubiquitously expressed transcription factors that are widely activated by various proinflammatory stimuli in the tumor microenvironment, including TNF-α, IL-1β and the IκB kinase (IKK) complex [115]. There are two major signaling pathways that mediate NF-κB activation: the canonical and noncanonical pathways. The canonical pathway (also known as classical pathway) depends on the IKK complex and is mainly activated by proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α or IL-1β), growth factors as well as pathogenassociated molecular patterns (PAMPs), thereby enhancing cell survival and proliferation [123]. The non-canonical pathway (also known as alternative pathway) does not require the trimeric IKK complex and depends on the inducible processing of p100, a molecule functioning as both the precursor of p52 and a RelB-specific inhibitor [124].

NF-κB activation has been reported in various human neoplasms including BCa. Fisetin, a dietary flavonoid, significantly reduces the incidence of N-methyl-N-nitrosourea (MNU) -induced bladder tumors by suppressing NF-κB activation [125]. The curcumin potentiates the antitumor effect of Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) through the induction of TRAIL receptors and inhibition of NF-κB in bladder cancer cells [126]. Nuclear expression of NF-κB is correlated with histologic grade and T category in bladder urothelial carcinoma (UC) [127]. AKT-mediated NF-κB activation upregulates snail expression and induces EMT, therefore, promoting tumor progression and metastasis in BCa [128]. NF-κB activation also mediates angiogenesis and metastasis of BTCC through the regulation of IL-8 [129]. In addition, down-regulation of NF-κB activation results in enhanced sensitivity of bladder cancer cells towards chemotherapeutic agents [130, 131].

PI3K-Akt-mTOR

PI3K activation is initiated in response to cell surface tyrosine kinase receptor-ligand binding, and leads to the conversion of phophatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3) [132]. Subsequently, PIP3 recruits AKT and phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1) to the plasma membrane, resulting in the phosphorylation of AKT either by PDK1 at Thr308 or by mTORC2 at Ser473 [133]. And then, AKT phosphorylation disrupts the interaction between tuberous sclerosis protein complex 1 (TSC1) and TSC2, and further inhibits the activation of Rheb that is a suppressor of mTOR function [134]. There are two functionally distinct mTOR complexes, mTORC1 and mTORC2. mTORC1 is mainly regulates protein translation and cell metabolism through its various downstream effectors. In contrast, mTORC2 is involved in actin cytoskeleton organization and cell survival. In addition, mTORC2 also regulates AKT activity by a feed-back loop [135].

PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling pathway is frequently changed in several malignancies including BCa. Chen et al. evaluated 231 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in 19 genes in the PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling pathway and they found four SNPs in raptor that were significantly associated with increased risk of BCa [136]. Moreover, activation of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway was demonstrated to be correlated with tumor progression and poor survival of BCa patients [137]. Nicotine could induce acquired chemoresistance and increase tumor growth through activation of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway in BCa [138]. Angiogenin (ANG), a member of RNase A superfamily, is recently demonstrated to promote tumor angiogenesis, tumorigenesis and metastasis of BCa by activating key downstream target molecules of PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling pathway [139]. Although significant progress has been made in defining the role of this pathway in BCa, the mechanisms by which PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway promotes BCa carcinogenesis and progression are not well known.

MicroRNAs

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small noncoding molecules that regulate gene expression by silencing mRNA targets. miRNA dysregulation exhibits great regulatory potential during organismal development, cell proliferation and death, immunity, and inflammation [140]. Recently, increasing studies have linked miRNAs to inflammation during bladder cancer initiation and development.

TNF-α-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) shows a strong apoptosis-inducing effect on a variety of cancer cells including BCa. MiRNA-221 silencing promoted cell apoptosis induced by TRAIL in T24 cells [141]. The problem that adenoviral vector lacks the ability to discriminate cancer and normal cells seriously hurdles the clinical application of TRAIL therapy. To solve the problem, Zhao et al. applied miRNA response elements (MREs) of miR-1, miR-133 and miR-218 to confer TRAIL expression with specificity to bladder cancer cells. They found that miRNA response elements-based TRAIL delivery showed specific survival-suppressing activity on bladder cancer [142]. Notwithstanding a long list of miRNAs deregulated in BCa, there is very little overlap in the patterns of miRNA expression between inflammation and BCa. In order to evaluate the differential effects of inflammation on the bladder cancer, microRNA research may be an exciting and challenging field in the future.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PREVENTION AND TREATMENT OF BLADDER CANCER

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents and COX-2 inhibitors

Experimental and epidemiologic evidence strongly suggests that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and COX-2 inhibitors have the potential as chemopreventive agents for cancer (Table 2) [143, 144]. NSAIDs (such as naproxen, sulindac, and their NO derivatives) show good preventive effects in a chemically induced urinary bladder cancer model [145]. As a NSAID, meloxicam treatment inhibits the development of bladder neoplastic lesions induced by BBN [146]. However, in a comprehensive meta-analysis, Zhang et al. evaluated the association between NSAIDs and BCa risk and they reported there was no significant association between use of aspirin or non-aspirin NSAIDs and BCa risk. However, non-aspirin NSAIDs use among long-term quitters might be associated with a decreased risk of BCa [147]. Celecoxib, a cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitor, promotes a striking inhibitory effect on BCa development, reinforcing the potential role of chemopreventive strategies based on COX-2 inhibition [148]. In contrast, the results from Sabichi et al. do not show a clinical benefit for celecoxib in preventing NMIBC recurrence [149]. So, whether the treatment of NSAIDs or COX-2 inhibitors may reduce the risk of BCa remains unclear.

Table 2. Active clinical drugs for the prevention and treatment of bladder cancer.

| Drugs | Identifier | Targets | Role | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meloxicam | NSAID | Unknown | Inhibition | 146 |

| Celecoxib | COX-2 inhibitor | COX-2 | Inhibition | 148 |

| BCG | Vaccine | Cytokines/chemokines and T cells | Inhibition | 151-155 |

| IL-15 | Gene therapy | T lymphocytes | Inhibition | 161 |

| IL-10 blocking antibodies | antibody | Th1 | Inhibition | 162 |

| Ipilimumab | CTLA-4 inhibitor | CTLA-4 | Investigation | 164 |

| Atezolizumab | PD-L1 inhibitor | PD-L1 | Inhibition | 167 |

| Nivolumab | PD-1 inhibitor | PD-1 | Inhibition | 167 |

| Pembrolizumab | PD-1 inhibitor | PD-1 | Inhibition | 164, 168 |

BCG immunotherapy

BCG, a live attenuated form of Mycobacterium bovis, has been used to treat high grade NMIBC for almost 40 years, to reduce the risk of recurrence and progression (Table 2) [150]. Currently, several meta-analyses have confirmed that intravesical BCG is a first-line choice for reducing tumor recurrence and delaying or preventing progression to MIBC [151–153]. In addition, some clinical and experimental research also show that intravesical BCG is safe and effective in immunologically compromised patients with BCa [154], and BCG treatment suppresses the tumorigenesis and progression in a BBN-treated rodent model [155]. Although the precise mechanism of BCG antitumor response remains undefined, the current research suggest that it stimulates both an inflammatory tumor response as well as an immune response to kill the bladder cancer cells [156]. BCG presents its antitumor potential by secretion of cytokines/chemokines (such as IL-6, IL-8, CXCL1 and CXCR4) into tumor microenviroment, moreover, increased levels of cytokines/chemokines in serum are associated with enhanced survival in the animal model of BCa [157]. BCG's anti-tumor effects can be also attributed to the elimination of BCG-infected cancer cells by presentation of cancer cell antigens to immune cells, including natural killer (NK) cells, CD4(+) T cells and CD8(+) T cells [158, 159].

ILs agonists or their antagonists

Based on the different role of ILs in the formation and development of BCa, ILs agonists or their antagonists are demonstrated to display distinct antitumor effect (Table 2). Intravesical IL-12 immunotherapy can induce tumor-specific systemic immunity against murine BCa [160]. IL-15 gene therapy inhibits cell survival in an orthotopic BCa model through inducing tumor-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes [161]. IL-10 blocking antibodies enhances BCG induced Th 1 immune responses and anti-bladder cancer immunity [162]. In addition, there are 18 phase I/II cancer clinical trials (http://clinicaltrials.gov/) is assessing the efficacy of IL with or without conventional chemotherapeutics.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) is a CD28 family member and is translocated to the membrane following activation of both CD4 and CD8 T cells. When expressed, CTLA-4 binds co-stimulatory B7 molecules with greater affinity than CD28 and generates a negative feedback loop to the early T cell response [163]. CTLA-4 targeting antibodies boost anti-tumor immunity through blocking the interaction between CTLA-4 and B7 ligands. Ipilimumab was the first FDA-approved CTLA-4 inhibitor for treatment of unresectable or metastatic melanoma as a monotherapy. Currently, one active trial (NCT01524991) is investigating the efficacy of the combination of Ipilimumab with conventional chemotherapeutics (Gemcitabine plus Cisplatin) as first-line treatment for patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma (Table 2) [164]. The information about the antitumor activity of this combination is underway.

Programed cell death protein 1 (PD-1or CD279) is another coinhibitory receptor expressed on the surface of many different subtypes of tumor infiltrating leukocytes [165]. PD-1 is mainly activated by interacting with its ligands PD-L1 which is mainly expressed on dendritic cells, IFN-γ-treated monocytes and many types of cancer cells [166]. The first FDA-approved PD-L1 inhibitor in bladder cancer was atezolizumab, in May 2016, for patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma after disease progression on or within 12 months of receiving platinum-based chemotherapy either before (neoadjuvant) or after (adjuvant) surgical treatment. This was followed by the approval of PD-1 blockade drug nivolumab in February 2017 for treatment of locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma whose disease has progressed during a period of up to 1 year after first-line platinum-containing chemotherapy [167]. Another PD-L1 inhibitor pembrolizumab showed a 24.1% overall response rate for urothelial cancer patients. To assess the efficacy of the combination of pembrolizumab with conventional chemotherapeutics, several clinical trials (NCT02335424, NCT02351739 and NCT022456436) have been launched [164, 168]. As mentioned, PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitors have shown promising roles in the treatment of BCa patients (Table 2). However, future research is necessary to characterize therapeutic response and identify predictive markers of response for these drugs.

CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

Chronic inflammation is an important risk factor for the development of urinary bladder cancer. Many factors are involved in inflammation-associated cancer risk, including infections (bacterial, S. haematobium, viral), immunological disorders, and chronic chemical and mechanical irritation. Multiple proinflammatory molecules and signaling pathways in tumor microenvironment may elicit a crucial role in formation and progression of BCa. Therefore, several cytokine/chemokine antagonists or their antagonists and some signaling pathway inhibitors as potential agents of chemoprevention and treatment against BCa are in clinical investigation.

However, several gaps still exist in our knowledge that should be addressed in the future. Firstly, the question whether we should try to inhibit local inflammatory reactions or systemic inflammation responses is paradoxical since neoplastic disorders are usually associated with a local but not a systemic inflammatory response, which should be considered in the ongoing clinical trials where systemic anti-inflammation agents are used in the prevention and treatment of BCa. Second, it is unclear whether inflammation is sufficient for the formation of cancer, which means whether inflammation can induce carcinogenesis in the absence of an exogenous carcinogenic agent. Third, it has been known that the outcomes of inflammation activation are highly dependent on the treatment characteristic and tumor types. Moreover, the signaling pathways involved in chronic inflammatory tumor microenvironment and their possible crosstalk among themselves are complicated. So, what is needed to be better known include elucidating the specific impact of the chronic inflammation on bladder carcinogenesis and progression, and determining the exact molecular mechanisms by which the chronic inflammation can regulate the growth, survival, invasion and metastasis. However, our increased understanding of the role of chronic inflammation in tumor microenvironment will hopefully provide us an attractive therapeutic strategy to impede carcinogenesis, inhibit cancer cell survival and metastasis for bladder cancer patients.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

None of the contents of this manuscript has been previously published or is under consideration elsewhere. All the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript prior to submission.

FUNDING

This study is sponsored by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant No. 81672932 and 81730108), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China for Distinguished Young Scholars (grant No. LR18H160001), Zhejiang province medical science and technology project (grant No. 2017RC007), Major Zhejiang province medical science and technology project (grant No. 2015C03055), Talent Project of Zhejiang Association for Science and Technology (grant No. 2017YCGC002), Zhejiang province science and technology project of TCM (grant No. 2015ZB033) and NIH (1R01DE019823, XL).

REFERENCES

- 1.Virchow R. Cellular pathology. As based upon physiological and pathological histology. Lecture XVI--atheromatous affection of arteries. 1858. Nutr Rev. 1989;47:23–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1989.tb02747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fernandes JV, Cobucci RN, Jatoba CA, Fernandes TA, de Azevedo JW, de Araujo JM. The role of the mediators of inflammation in cancer development. Pathol Oncol Res. 2015;21:527–534. doi: 10.1007/s12253-015-9913-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shalapour S, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer: an eternal fight between good and evil. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:3347–3355. doi: 10.1172/JCI80007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma C, Kesarwala AH, Eggert T, Medina-Echeverz J, Kleiner DE, Jin P, Stroncek DF, Terabe M, Kapoor V, ElGindi M, Han M, Thornton AM, Zhang H, et al. NAFLD causes selective CD4(+) T lymphocyte loss and promotes hepatocarcinogenesis. Nature. 2016;531:253–257. doi: 10.1038/nature16969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prasad SM, Decastro GJ, Steinberg GD. Medscape. Urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: definition, treatment and future efforts. Nat Rev Urol. 2011;8:631–642. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2011.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeegers MP, Tan FE, Dorant E, van Den Brandt PA. The impact of characteristics of cigarette smoking on urinary tract cancer risk: a meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. Cancer. 2000;89:630–639. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000801)89:3<630::aid-cncr19>3.3.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Latifovic L, Villeneuve PJ, Parent ME, Johnson KC, Kachuri L, The Canadian Cancer Registries Epidemiology Group. Harris SA. Bladder cancer and occupational exposure to diesel and gasoline engine emissions among Canadian men. Cancer Med. 2015;4:1948–1962. doi: 10.1002/cam4.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gakis G. The role of inflammation in bladder cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;816:183–196. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-0837-8_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim HS, Ku JH. Systemic inflammatory response based on neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic marker in bladder cancer. Dis Markers. 2016;2016:8345286. doi: 10.1155/2016/8345286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin C, Lin W, Yeh S, Li L, Chang C. Infiltrating neutrophils increase bladder cancer cell invasion via modulation of androgen receptor (AR)/MMP13 signals. Oncotarget. 2015;6:43081–43089. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5638. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.5638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salvatore S, Salvatore S, Cattoni E, Siesto G, Serati M, Sorice P, Torella M. Urinary tract infections in women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;156:131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stamm WE. Scientific and clinical challenges in the management of urinary tract infections. Am J Med. 2002;113:1S–4S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stone L. Bladder cancer: urinary tract infection increases risk. Nat Rev Urol. 2015;12:4. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2014.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun LM, Lin CL, Liang JA, Liu SH, Sung FC, Chang YJ, Kao CH. Urinary tract infection increases subsequent urinary tract cancer risk: a population-based cohort study. Cancer Sci. 2013;104:619–623. doi: 10.1111/cas.12127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richards KA, Ham S, Cohn JA, Steinberg GD. Urinary tract infection-like symptom is associated with worse bladder cancer outcomes in the Medicare population: implications for sex disparities. Int J Urol. 2016;23:42–47. doi: 10.1111/iju.12959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang X, Castelao JE, Groshen S, Cortessis VK, Shibata D, Conti DV, Yuan JM, Pike MC, Gago-Dominguez M. Urinary tract infections and reduced risk of bladder cancer in Los Angeles. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:834–839. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vermeulen SH, Hanum N, Grotenhuis AJ, Castano-Vinyals G, van der Heijden AG, Aben KK, Mysorekar IU, Kiemeney LA. Recurrent urinary tract infection and risk of bladder cancer in the Nijmegen bladder cancer study. Br J Cancer. 2015;112:594–600. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bedwani R, Renganathan E, El Kwhsky F, Braga C, Abu Seif HH, Abul Azm T, Zaki A, Franceschi S, Boffetta P, La Vecchia C. Schistosomiasis and the risk of bladder cancer in Alexandria, Egypt. Br J Cancer. 1998;77:1186–1189. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Botelho MC, Oliveira PA, Lopes C, Correia da Costa JM, Machado JC. Urothelial dysplasia and inflammation induced by Schistosoma haematobium total antigen instillation in mice normal urothelium. Urol Oncol. 2011;29:809–814. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2009.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mostafa MH, Sheweita SA, O'Connor PJ. Relationship between schistosomiasis and bladder cancer. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:97–111. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.1.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Botelho MC, Veiga I, Oliveira PA, Lopes C, Teixeira M, da Costa JM, Machado JC. Carcinogenic ability of possibly through oncogenic mutation of gene. Adv Cancer Res Treat. 20132013 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shams TM, Metawea M, Salim EI. c-KIT positive schistosomal urinary bladder carcinoma are frequent but lack KIT gene mutations. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:15–20. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thanan R, Murata M, Ma N, Hammam O, Wishahi M, El Leithy T, Hiraku Y, Oikawa S, Kawanishi S. Nuclear localization of COX-2 in relation to the expression of stemness markers in urinary bladder cancer. Mediators Inflamm. 2012;2012:165879. doi: 10.1155/2012/165879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santos J, Fernandes E, Ferreira JA, Lima L, Tavares A, Peixoto A, Parreira B, Correia da Costa JM, Brindley PJ, Lopes C, Santos LL. P53 and cancer-associated sialylated glycans are surrogate markers of cancerization of the bladder associated with Schistosoma haematobium infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e3329. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Honeycutt J, Hammam O, Hsieh MH. Schistosoma haematobium egg-induced bladder urothelial abnormalities dependent on p53 are modulated by host sex. Exp Parasitol. 2015;158:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steenbergen RD, Snijders PJ, Heideman DA, Meijer CJ. Clinical implications of (epi)genetic changes in HPV-induced cervical precancerous lesions. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:395–405. doi: 10.1038/nrc3728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tornesello ML, Perri F, Buonaguro L, Ionna F, Buonaguro FM, Caponigro F. HPV-related oropharyngeal cancers: from pathogenesis to new therapeutic approaches. Cancer Lett. 2014;351:198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mudrikova T, Jaspers C, Ellerbroek P, Hoepelman A. HPV-related anogenital disease and HIV infection: not always ‘ordinary’ condylomata acuminata. Neth J Med. 2008;66:98–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li N, Yang L, Zhang Y, Zhao P, Zheng T, Dai M. Human papillomavirus infection and bladder cancer risk: a meta-analysis. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:217–223. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Offutt-Powell TN, Ojha RP, Tota JE, Gurney JG. Human papillomavirus infection and bladder cancer: an alternate perspective from a modified meta-analysis. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:453–454. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis364. author reply 454-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim SH, Joung JY, Chung J, Park WS, Lee KH, Seo HK. Detection of human papillomavirus infection and p16 immunohistochemistry expression in bladder cancer with squamous differentiation. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93525. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shigehara K, Kawaguchi S, Sasagawa T, Nakashima K, Nakashima T, Shimamura M, Namiki M. Etiological correlation of human papillomavirus infection in the development of female bladder tumor. APMIS. 2013;121:1169–1176. doi: 10.1111/apm.12070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of urothelial bladder carcinoma. Nature. 2014;507:315–322. doi: 10.1038/nature12965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clouston D, Lawrentschuk N. Metaplastic conditions of the bladder. BJU Int. 2013;112:27–31. doi: 10.1111/bju.12378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takahashi S, Ikeda Y, Kimoto N, Okochi E, Cui L, Nagao M, Ushijima T, Shirai T. Mutation induction by mechanical irritation caused by uracil-induced urolithiasis in Big Blue rats. Mutat Res. 2000;447:275–280. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(99)00217-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vasconcelos-Nobrega C, Colaco A, Lopes C, Oliveira PA. Review: BBN as an urothelial carcinogen. In Vivo. 2012;26:727–739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fukushima S, Tanaka H, Asakawa E, Kagawa M, Yamamoto A, Shirai T. Carcinogenicity of uracil, a nongenotoxic chemical, in rats and mice and its rationale. Cancer Res. 1992;52:1675–1680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shih CJ, Chen YT, Ou SM, Yang WC, Chen TJ, Tarng DC. Urinary calculi and risk of cancer: a nationwide population-based study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2014;93:e342. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cho JH, Holley JL. Squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder in a female associated with multiple bladder stones. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:354. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mobley TL, Coyle JK, al-Hussaini M, McDonald DF. The role of chronic mechanical irritation in experimental urothelial tumorigenesis. Invest Urol. 1966;3:325–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu Y, Noon AP, Aguiar Cabeza E, Shen J, Kuk C, Ilczynski C, Ni R, Sukhu B, Chan K, Barbosa-Morais NL, Hermanns T, Blencowe BJ, Azad A, et al. Next-generation RNA sequencing of archival formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded urothelial bladder cancer. Eur Urol. 2014;66:982–986. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miyakawa M, Yoshida O. Induction of tumors of the urinary bladder in female mice following surgical implantation of glass beads and feeding of bracken fern. Gan. 1975;66:437–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ho CH, Sung KC, Lim SW, Liao CH, Liang FW, Wang JJ, Wu CC. Chronic indwelling urinary catheter increase the risk of bladder cancer, even in patients without spinal cord injury. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1736. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soergel TM, Cain MP, Misseri R, Gardner TA, Koch MO, Rink RC. Transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder following augmentation cystoplasty for the neuropathic bladder. J Urol. 2004;172:1649–1651. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000140194.87974.56. discussion 1651-1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Husmann DA, Rathbun SR. Long-term follow up of enteric bladder augmentations: the risk for malignancy. J Pediatr Urol. 2008;4:381–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2008.06.003. discussion 386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Higuchi TT, Granberg CF, Fox JA, Husmann DA. Augmentation cystoplasty and risk of neoplasia: fact, fiction and controversy. J Urol. 2010;184:2492–2496. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ray K. Bladder cancer: Does augmentation cystoplasty increase the risk of bladder cancer? Nat Rev Urol. 2010;7:648. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2010.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Biswas SK, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:889–896. doi: 10.1038/ni.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rodriguez D, Silvera R, Carrio R, Nadji M, Caso R, Rodriguez G, Iragavarapu-Charyulu V, Torroella-Kouri M. Tumor microenvironment profoundly modifies functional status of macrophages: peritoneal and tumor-associated macrophages are two very different subpopulations. Cell Immunol. 2013;283:51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Svatek RS, Zhao XR, Morales EE, Jha MK, Tseng TY, Hugen CM, Hurez V, Hernandez J, Curiel TJ. Sequential intravesical mitomycin plus Bacillus Calmette-Guerin for non-muscle-invasive urothelial bladder carcinoma: translational and phase I clinical trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:303–311. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maniecki MB, Etzerodt A, Ulhoi BP, Steiniche T, Borre M, Dyrskjot L, Orntoft TF, Moestrup SK, Moller HJ. Tumor-promoting macrophages induce the expression of the macrophage-specific receptor CD163 in malignant cells. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:2320–2331. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lima L, Oliveira D, Tavares A, Amaro T, Cruz R, Oliveira MJ, Ferreira JA, Santos L. The predominance of M2-polarized macrophages in the stroma of low-hypoxic bladder tumors is associated with BCG immunotherapy failure. Urol Oncol. 2014;32:449–457. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tian YF, Tang K, Guan W, Yang T, Xu H, Zhuang QY, Ye ZQ. OK-432 suppresses proliferation and metastasis by tumor associated macrophages in bladder cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:4537–4542. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.11.4537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sag D, Cekic C, Wu R, Linden J, Hedrick CC. The cholesterol transporter ABCG1 links cholesterol homeostasis and tumour immunity. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6354. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brandau S, Trellakis S, Bruderek K, Schmaltz D, Steller G, Elian M, Suttmann H, Schenck M, Welling J, Zabel P, Lang S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the peripheral blood of cancer patients contain a subset of immature neutrophils with impaired migratory properties. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;89:311–317. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0310162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Damuzzo V, Pinton L, Desantis G, Solito S, Marigo I, Bronte V, Mandruzzato S. Complexity and challenges in defining myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2015;88:77–91. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.21206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:162–174. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Movahedi K, Guilliams M, Van den Bossche J, Van den Bergh R, Gysemans C, Beschin A, De Baetselier P, Van Ginderachter JA. Identification of discrete tumor-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cell subpopulations with distinct T cell-suppressive activity. Blood. 2008;111:4233–4244. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-099226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Obermajer N, Wong JL, Edwards RP, Odunsi K, Moysich K, Kalinski P. PGE(2)-driven induction and maintenance of cancer-associated myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Immunol Invest. 2012;41:635–657. doi: 10.3109/08820139.2012.695417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Muthuswamy R, Wang L, Pitteroff J, Gingrich JR, Kalinski P. Combination of IFNalpha and poly-I: C reprograms bladder cancer microenvironment for enhanced CTL attraction. J Immunother Cancer. 2015;3:6. doi: 10.1186/s40425-015-0050-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang H, Chin AI. Role of Rip2 in development of tumor-infiltrating MDSCs and bladder cancer metastasis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94793. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yuan XK, Zhao XK, Xia YC, Zhu X, Xiao P. Increased circulating immunosuppressive CD14(+)HLA-DR(-/low) cells correlate with clinical cancer stage and pathological grade in patients with bladder carcinoma. J Int Med Res. 2011;39:1381–1391. doi: 10.1177/147323001103900424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Menetrier-Caux C, Curiel T, Faget J, Manuel M, Caux C, Zou W. Targeting regulatory T cells. Target Oncol. 2012;7:15–28. doi: 10.1007/s11523-012-0208-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen X, Du Y, Lin X, Qian Y, Zhou T, Huang Z. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in tumor immunity. Int Immunopharmacol. 2016;34:244–249. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Priceman SJ, Shen S, Wang L, Deng J, Yue C, Kujawski M, Yu H. S1PR1 is crucial for accumulation of regulatory T cells in tumors via STAT3. Cell Rep. 2014;6:992–999. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chi LJ, Lu HT, Li GL, Wang XM, Su Y, Xu WH, Shen BZ. Involvement of T helper type 17 and regulatory T cell activity in tumour immunology of bladder carcinoma. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;161:480–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04215.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Loskog A, Ninalga C, Paul-Wetterberg G, de la Torre M, Malmstrom PU, Totterman TH. Human bladder carcinoma is dominated by T-regulatory cells and Th1 inhibitory cytokines. J Urol. 2007;177:353–358. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.08.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Loskog AS, Fransson ME, Totterman TT. AdCD40L gene therapy counteracts T regulatory cells and cures aggressive tumors in an orthotopic bladder cancer model. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:8816–8821. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bloy N, Pol J, Aranda F, Eggermont A, Cremer I, Fridman WH, Fucikova J, Galon J, Tartour E, Spisek R, Dhodapkar MV, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G, Galluzzi L. Trial watch: dendritic cell-based anticancer therapy. Oncoimmunology. 2014;3:e963424. doi: 10.4161/21624011.2014.963424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lang F, Linlin M, Ye T, Yuhai Z. Alterations of dendritic cell subsets and TH1/TH2 cytokines in the peripheral circulation of patients with superficial transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. J Clin Lab Anal. 2012;26:365–371. doi: 10.1002/jcla.21532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chaux P, Favre N, Bonnotte B, Moutet M, Martin M, Martin F. Tumor-infiltrating dendritic cells are defective in their antigen-presenting function and inducible B7 expression. A role in the immune tolerance to antigenic tumors. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1997;417:525–528. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-9966-8_86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Norian LA, Rodriguez PC, O'Mara LA, Zabaleta J, Ochoa AC, Cella M, Allen PM. Tumor-infiltrating regulatory dendritic cells inhibit CD8+ T cell function via L-arginine metabolism. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3086–3094. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Karyampudi L, Lamichhane P, Krempski J, Kalli KR, Behrens MD, Vargas DM, Hartmann LC, Janco JM, Dong H, Hedin KE, Dietz AB, Goode EL, Knutson KL. PD-1 blunts the function of ovarian tumor-infiltrating dendritic cells by inactivating NF-kappaB. Cancer Res. 2016;76:239–250. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tran Janco JM, Lamichhane P, Karyampudi L, Knutson KL. Tumor-infiltrating dendritic cells in cancer pathogenesis. J Immunol. 2015;194:2985–2991. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1403134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ayari C, LaRue H, Hovington H, Caron A, Bergeron A, Tetu B, Fradet V, Fradet Y. High level of mature tumor-infiltrating dendritic cells predicts progression to muscle invasion in bladder cancer. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:1630–1637. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2013.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Xiang ST, Zhou SW, Guan W, Liu JH, Ye ZQ. [Expression of MUC1 and distribution of tumor-infiltrating dentritic cells in human bladder transitional cell carcinoma] [Article in Chinese]. Di Yi Jun Yi Da Xue Xue Bao. 2005;25:1114–1118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Soucek L, Lawlor ER, Soto D, Shchors K, Swigart LB, Evan GI. Mast cells are required for angiogenesis and macroscopic expansion of Myc-induced pancreatic islet tumors. Nat Med. 2007;13:1211–1218. doi: 10.1038/nm1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Serel TA, Soyupek S, Candir O. Association between mast cells and bladder carcinoma. Urol Int. 2004;72:299–302. doi: 10.1159/000077681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kim JH, Kang YJ, Kim DS, Lee CH, Jeon YS, Lee NK, Oh MH. The relationship between mast cell density and tumour grade in transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. J Int Med Res. 2011;39:1675–1681. doi: 10.1177/147323001103900509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sari A, Calli A, Cakalagaoglu F, Altinboga AA, Bal K. Association of mast cells with microvessel density in urothelial carcinomas of the urinary bladder. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2012;16:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rao Q, Chen Y, Yeh CR, Ding J, Li L, Chang C, Yeh S. Recruited mast cells in the tumor microenvironment enhance bladder cancer metastasis via modulation of ERbeta/CCL2/CCR2 EMT/MMP9 signals. Oncotarget. 2016;7:7842–7855. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5467. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.5467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Isfoss BL, Busch C, Hermelin H, Vermedal AT, Kile M, Braathen GJ, Majak B, Berner A. Stem cell marker-positive stellate cells and mast cells are reduced in benign-appearing bladder tissue in patients with urothelial carcinoma. Virchows Arch. 2014;464:473–488. doi: 10.1007/s00428-014-1561-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bugan B, Onar LC. Is the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio a crucial indicator of systemic inflammation, coronary artery ectasia, and atherogenesis? Angiology. 2013;64:636. doi: 10.1177/0003319713491624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gu X, Gao X, Li X, Qi X, Ma M, Qin S, Yu H, Sun S, Zhou D, Wang W. Prognostic significance of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in prostate cancer: evidence from 16,266 patients. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22089. doi: 10.1038/srep22089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Haruki K, Shiba H, Horiuchi T, Shirai Y, Iwase R, Fujiwara Y, Furukawa K, Misawa T, Yanaga K. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts therapeutic outcome after pancreaticoduodenectomy for carcinoma of the ampulla of vater. Anticancer Res. 2016;36:403–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Viers BR, Boorjian SA, Frank I, Tarrell RF, Thapa P, Karnes RJ, Thompson RH, Tollefson MK. Pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is associated with advanced pathologic tumor stage and increased cancer-specific mortality among patients with urothelial carcinoma of the bladder undergoing radical cystectomy. Eur Urol. 2014;66:1157–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hermanns T, Bhindi B, Wei Y, Yu J, Noon AP, Richard PO, Bhatt JR, Almatar A, Jewett MA, Fleshner NE, Zlotta AR, Templeton AJ, Kulkarni GS. Pre-treatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as predictor of adverse outcomes in patients undergoing radical cystectomy for urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:444–451. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Seah JA, Leibowitz-Amit R, Atenafu EG, Alimohamed N, Knox JJ, Joshua AM, Sridhar SS. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and pathological response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2015;13:e229–233. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Okamoto M, Oyasu R. Transformation in vitro of a nontumorigenic rat urothelial cell line by tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Lab Invest. 1997;77:139–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Raziuddin S, Masihuzzaman M, Shetty S, Ibrahim A. Tumor necrosis factor alpha production in schistosomiasis with carcinoma of urinary bladder. J Clin Immunol. 1993;13:23–29. doi: 10.1007/BF00920632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yang Z, Lv Y, Lv Y, Wang Y. Meta-analysis shows strong positive association of the TNF-alpha gene with tumor stage in bladder cancer. Urol Int. 2012;89:337–341. doi: 10.1159/000341701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lee EJ, Kim WJ, Moon SK. Cordycepin suppresses TNF-alpha-induced invasion, migration and matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression in human bladder cancer cells. Phytother Res. 2010;24:1755–1761. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Seddighzadeh M, Larsson P, Ulfgren AC, Onelov E, Berggren P, Tribukait B, Torstensson A, Norming U, Wijkstrom H, Linder S, Steineck G. Low IL-1alpha expression in bladder cancer tissue and survival. Eur Urol. 2003;43:362–368. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(03)00047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chen MF, Lin PY, Wu CF, Chen WC, Wu CT. IL-6 expression regulates tumorigenicity and correlates with prognosis in bladder cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61901. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tsui KH, Wang SW, Chung LC, Feng TH, Lee TY, Chang PL, Juang HH. Mechanisms by which interleukin-6 attenuates cell invasion and tumorigenesis in human bladder carcinoma cells. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:791212. doi: 10.1155/2013/791212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Escudero-Lourdes C, Wu T, Camarillo JM, Gandolfi AJ. Interleukin-8 (IL-8) over-production and autocrine cell activation are key factors in monomethylarsonous acid [MMA(III)]-induced malignant transformation of urothelial cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2012;258:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Reis ST, Leite KR, Piovesan LF, Pontes-Junior J, Viana NI, Abe DK, Crippa A, Moura CM, Adonias SP, Srougi M, Dall'Oglio MF. Increased expression of MMP-9 and IL-8 are correlated with poor prognosis of Bladder Cancer. BMC Urol. 2012;12:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-12-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wang L, Yi T, Kortylewski M, Pardoll DM, Zeng D, Yu H. IL-17 can promote tumor growth through an IL-6-Stat3 signaling pathway. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1457–1464. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Baharlou R, Ahmadi Vasmehjani A, Dehghani A, Ghobadifar MA, Khoubyari M. Reduced interleukin-17 and transforming growth factor Beta levels in peripheral blood as indicators for following the course of bladder cancer. Immune Netw. 2014;14:156–163. doi: 10.4110/in.2014.14.3.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Jaiswal PK, Singh V, Srivastava P, Mittal RD. Association of IL-12, IL-18 variants and serum IL-18 with bladder cancer susceptibility in North Indian population. Gene. 2013;519:128–134. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Margulis V, Shariat SF, Ashfaq R, Thompson M, Sagalowsky AI, Hsieh JT, Lotan Y. Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in normal urothelium, and superficial and advanced transitional cell carcinoma of bladder. J Urol. 2007;177:1163–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shirahama T, Sakakura C. Overexpression of cyclooxygenase-2 in squamous cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:558–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wadhwa P, Goswami AK, Joshi K, Sharma SK. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression increases with the stage and grade in transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Int Urol Nephrol. 2005;37:47–53. doi: 10.1007/s11255-004-4699-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tadin T, Krpina K, Stifter S, Babarovic E, Fuckar Z, Jonjic N. Lower cyclooxygenase-2 expression is associated with recurrence of solitary non-muscle invasive bladder carcinoma. Diagn Pathol. 2012;7:152. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-7-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cheng H, Wang L, Mollica M, Re AT, Wu S, Zuo L. Nitric oxide in cancer metastasis. Cancer Lett. 2014;353:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Xu W, Liu LZ, Loizidou M, Ahmed M, Charles IG. The role of nitric oxide in cancer. Cell Res. 2002;12:311–320. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Shochina M, Fellig Y, Sughayer M, Pizov G, Vitner K, Podeh D, Hochberg A, Ariel I. Nitric oxide synthase immunoreactivity in human bladder carcinoma. Mol Pathol. 2001;54:248–252. doi: 10.1136/mp.54.4.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Morcos E, Jansson OT, Adolfsson J, Kratz G, Wiklund NP. Endogenously formed nitric oxide modulates cell growth in bladder cancer cell lines. Urology. 1999;53:1252–1257. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)00033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lin Z, Chen S, Ye C, Zhu S. Nitric oxide synthase expression in human bladder cancer and its relation to angiogenesis. Urol Res. 2003;31:232–235. doi: 10.1007/s00240-003-0302-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Buchert M, Burns CJ, Ernst M. Targeting JAK kinase in solid tumors: emerging opportunities and challenges. Oncogene. 2016;35:939–951. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Aaronson DS, Horvath CM. A road map for those who don't know JAK-STAT. Science. 2002;296:1653–1655. doi: 10.1126/science.1071545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Teng Y, Ross JL, Cowell JK. The involvement of JAK-STAT3 in cell motility, invasion, and metastasis. JAKSTAT. 2014;3:e28086. doi: 10.4161/jkst.28086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.He G, Karin M. NF-kappaB and STAT3 - key players in liver inflammation and cancer. Cell Res. 2011;21:159–168. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Chen RJ, Ho YS, Guo HR, Wang YJ. Rapid activation of Stat3 and ERK1/2 by nicotine modulates cell proliferation in human bladder cancer cells. Toxicol Sci. 2008;104:283–293. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Chen CL, Cen L, Kohout J, Hutzen B, Chan C, Hsieh FC, Loy A, Huang V, Cheng G, Lin J. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 activation is associated with bladder cancer cell growth and survival. Mol Cancer. 2008;7:78. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-7-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Zhang B, Lu Z, Hou Y, Hu J, Wang C. The effects of STAT3 and Survivin silencing on the growth of human bladder carcinoma cells. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:5401–5407. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-1704-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ho PL, Lay EJ, Jian W, Parra D, Chan KS. Stat3 activation in urothelial stem cells leads to direct progression to invasive bladder cancer. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3135–3142. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Shen HB, Gu ZQ, Jian K, Qi J. CXCR4-mediated Stat3 activation is essential for CXCL12-induced cell invasion in bladder cancer. Tumour Biol. 2013;34:1839–1845. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0725-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Itoh M, Murata T, Suzuki T, Shindoh M, Nakajima K, Imai K, Yoshida K. Requirement of STAT3 activation for maximal collagenase-1 (MMP-1) induction by epidermal growth factor and malignant characteristics in T24 bladder cancer cells. Oncogene. 2006;25:1195–1204. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Zhao D, Besser AH, Wander SA, Sun J, Zhou W, Wang B, Ince T, Durante MA, Guo W, Mills G, Theodorescu D, Slingerland J. Cytoplasmic p27 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and tumor metastasis via STAT3-mediated Twist1 upregulation. Oncogene. 2015;34:5447–5459. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Annunziata CM, Davis RE, Demchenko Y, Bellamy W, Gabrea A, Zhan F, Lenz G, Hanamura I, Wright G, Xiao W, Dave S, Hurt EM, Tan B, et al. Frequent engagement of the classical and alternative NF-kappaB pathways by diverse genetic abnormalities in multiple myeloma. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:115–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Sun SC. Non-canonical NF-κB signaling pathway. Cell Res. 2011;21:71–85. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Li J, Qu W, Cheng Y, Sun Y, Jiang Y, Zou T, Wang Z, Xu Y, Zhao H. The inhibitory effect of intravesical fisetin against bladder cancer by induction of p53 and down-regulation of NF-kappa B pathways in a rat bladder carcinogenesis model. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2014;115:321–329. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.12229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Kamat AM, Tharakan ST, Sung B, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin potentiates the antitumor effects of Bacillus Calmette-Guerin against bladder cancer through the downregulation of NF-kappaB and upregulation of TRAIL receptors. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8958–8966. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Levidou G, Saetta AA, Korkolopoulou P, Papanastasiou P, Gioti K, Pavlopoulos P, Diamantopoulou K, Thomas-Tsagli E, Xiromeritis K, Patsouris E. Clinical significance of nuclear factor (NF)-kappaB levels in urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Virchows Arch. 2008;452:295–304. doi: 10.1007/s00428-007-0560-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Julien S, Puig I, Caretti E, Bonaventure J, Nelles L, van Roy F, Dargemont C, de Herreros AG, Bellacosa A, Larue L. Activation of NF-kappaB by Akt upregulates Snail expression and induces epithelium mesenchyme transition. Oncogene. 2007;26:7445–7456. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Karashima T, Sweeney P, Kamat A, Huang S, Kim SJ, Bar-Eli M, McConkey DJ, Dinney CP. Nuclear factor-kappaB mediates angiogenesis and metastasis of human bladder cancer through the regulation of interleukin-8. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:2786–2797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Ito Y, Kikuchi E, Tanaka N, Kosaka T, Suzuki E, Mizuno R, Shinojima T, Miyajima A, Umezawa K, Oya M. Down-regulation of NF kappa B activation is an effective therapeutic modality in acquired platinum-resistant bladder cancer. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:324. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1315-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Wu M, Chen J, Wang Y, Hu J, Liu C, Feng C, Zeng X. URGCP/URG4 promotes apoptotic resistance in bladder cancer cells by activating NF-kappaB signaling. Oncotarget. 2015;6:30887–30901. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5134. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.5134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Drakas R, Tu X, Baserga R. Control of cell size through phosphorylation of upstream binding factor 1 by nuclear phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9272–9276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403328101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Riobo NA, Lu K, Ai X, Haines GM, Emerson CP., Jr Phosphoinositide 3-kinase and Akt are essential for Sonic Hedgehog signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:4505–4510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504337103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Inoki K, Li Y, Zhu T, Wu J, Guan KL. TSC2 is phosphorylated and inhibited by Akt and suppresses mTOR signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:648–657. doi: 10.1038/ncb839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Sabatini DM. mTOR and cancer: insights into a complex relationship. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:729–734. doi: 10.1038/nrc1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Chen M, Cassidy A, Gu J, Delclos GL, Zhen F, Yang H, Hildebrandt MA, Lin J, Ye Y, Chamberlain RM, Dinney CP, Wu X. Genetic variations in PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway and bladder cancer risk. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:2047–2052. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Sun CH, Chang YH, Pan CC. Activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway correlates with tumour progression and reduced survival in patients with urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Histopathology. 2011;58:1054–1063. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.03856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Yuge K, Kikuchi E, Hagiwara M, Yasumizu Y, Tanaka N, Kosaka T, Miyajima A, Oya M. Nicotine induces tumor growth and chemoresistance through activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in bladder cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14:2112–2120. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Peng Y, Li L, Huang M, Duan C, Zhang L, Chen J. Angiogenin interacts with ribonuclease inhibitor regulating PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in bladder cancer cells. Cell Signal. 2014;26:2782–2792. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Lu Q, Lu C, Zhou GP, Zhang W, Xiao H, Wang XR. MicroRNA-221 silencing predisposed human bladder cancer cells to undergo apoptosis induced by TRAIL. Urol Oncol. 2010;28:635–641. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Zhao Y, Li Y, Wang L, Yang H, Wang Q, Qi H, Li S, Zhou P, Liang P, Wang Q, Li X. microRNA response elements-regulated TRAIL expression shows specific survival-suppressing activity on bladder cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2013;32:10. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-32-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Vinogradova Y, Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C, Logan RF. Risk of colorectal cancer in patients prescribed statins, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors: nested case-control study. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:393–402. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]