Abstract

Whole sporozoite vaccines confer sterilizing immunity to malaria-naïve individuals by unknown mechanisms. In the first-ever PfSPZ Vaccine trial in a malaria endemic population, Vδ2 γδT cells were significantly elevated, and Vγ9/Vδ2 transcripts ranked as most-upregulated, in vaccinees that were protected from P. falciparum infection. In a mouse model, absence of γδ T cells during vaccination impaired protective CD8 T cell responses, and ablated sterile protection. γδ T cells were not required for CSP-specific antibody responses, and γδ T cell depletion before infectious challenge did not ablate protection. γδ T cells alone were insufficient to induce protection and required the presence of CD8α+ dendritic cells. In the absence of γδ T cells, CD8α+ DC did not accumulate in the livers of vaccinated mice. Altogether our results show that γδ T cells were essential for the induction of sterile immunity during whole organism vaccination.

Keywords: γδ T cells, PfSPZ vaccination, malaria

INTRODUCTION

Malaria caused over 430,000 deaths in 2014 (WHO report 2015) and effective vaccines are urgently required for malaria eradication. PfSPZ Vaccine (Sanaria®, USA) confers sterilizing immunity against homologous Plasmodium falciparum infection in malaria-naïve individuals (1, 2). The vaccine is composed of radiation-attenuated, aseptic, purified, cryopreserved P. falciparum (Pf) sporozoites (SPZ) (3). Humoral and cellular immune responses are induced after vaccination, but there is still no consensus on mechanisms of protection and no reliable immune correlates. Antibody responses have correlated with protection in U.S. studies of PfSPZ Vaccine, but protection is maintained in some individuals even as antibody wanes (4). Intriguingly, gamma delta (γδ) T cells expanded in a dose-dependent manner in malaria-naïve subjects immunized with PfSPZ Vaccine (2, 4), and the Vδ2 subset of γδ T cells was recently associated with protection in these vaccinees (4) suggesting a role in protective immunity.

γδ T cells constitute 1–5% of total T cells circulating in healthy adults and share features that are common to both the innate and adaptive immune systems (5–7). Two major types of γδ T cells in humans are differentiated by the expression of either Vδ2 or Vδ1 chains that recognize different classes of antigens. A subset of Vδ1 cells recognize lipid antigens presented on the CD1d molecule (8), while Vδ2 T cells respond to phosphoantigens presented on butyrophilin receptors (9). Vδ2 cells recognize the blood stages of malaria and respond by producing cytokines and lytic molecules that are required to control parasite replication (10–14). In mice, where the Vδ2 homologue has not been identified, γδ T cells induced by whole sporozoite (SPZ) vaccination of αβ T cell deficient animals inhibit intraheptocytic parasitic development (15). In addition to their role as effectors, Vδ2 T cells can directly prime CD4 and CD8 T cell responses in vitro (16, 17). Hence γδ T cells may have diverse functions that could contribute to PfSPZ Vaccine-induced responses.

The PfSPZ Vaccine trial that we conducted (ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT01988636) in Mali, West Africa was the first to assess efficacy of this vaccine against naturally occurring infection (18). Here we show that Vδ2 T cells were significantly higher in Malian adult vaccinees who remained uninfected throughout follow-up. In a mouse model of SPZ vaccination, we find that γδ T cells are required during vaccination but not at the time of challenge for protection, indicating they do not function as effectors. The absence of γδ T cells during vaccination was associated with reduced accumulation of CD8α+ dendritic cells (DC) to the liver and the ensuing development of αβ T cell responses, including CD8 T cells required for sterile protection; CSP-specific antibody responses did not require γδ T cells. The data support a model wherein induction of protective immunity during SPZ vaccination requires both γδ T cells and CD8α+ DCs.

METHODS

PfSPZ Vaccine trial

Eighty-eight subjects gave informed consent and were randomized to receive 5 doses of Sanaria® PfSPZ Vaccine (2.7×105 PfSPZ), or normal saline as the placebo control, by direct venous inoculation (DVI). Vaccinations were given at four-week intervals except for the fifth vaccination, which was given 8 weeks after the fourth vaccination. One ml of whole blood was collected in a sodium heparin tube from each volunteer for ex vivo assays two weeks after the final vaccination. 150 μl of whole blood was stained using the antibodies CD3-BV650, CD4-PerCP, CD8-APC-H7, γδTCR-PE, CD11a APC, CD38 BV421, Vδ2-FITC, CD45RO PECF594, CD56 PE-Cy7. After red blood cell lysis using the BD FACS Lyse solution (Becton Dickinson, USA), the cells were washed and acquired on a LSRII flow cytometer equipped with a Blue (488nm), Red (633 nm) and Violet laser (405 nm). γδ T cells were enumerated as a percentage of total CD3 T cells two weeks after the final vaccination. All antibodies used for the studies in this manuscript are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

RNA Sequencing

RNA was purified from whole blood collected in PAXgene tubes from 22 study volunteers (17 vaccinees and 5 placebo controls) 3 days after the final vaccination (Day 143) using the PAXGene Blood RNA kit (Qiagen, USA) kit per the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA quantity and quality were measured by the NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop technologies) and a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent) respectively, to confirm a yield of at least 200 ng RNA with a quality score of at least 7. RNA sequencing was performed at the NIH Intramural Sequencing Centre (NISC) on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 Platform. Raw FASTQ read data were processed using in-house R package DuffyNGS, as originally described (19). Briefly, raw reads pass through a 3-stage alignment pipeline: 1) a pre-alignment stage to filter out unwanted transcripts, such as ribosomal RNA, mitochondrial RNA, albumin, globin, etc.; 2) a main genomic alignment stage against the genome(s) of interest; 3) a splice junction alignment stage against an index of standard and alternative exon splice junctions. All alignments were performed with Bowtie2 (20), using command line option ‘–very-sensitive’. BAM files from stages 2 & 3 were combined into read depth wiggle tracks that record both uniquely mapped and multiply mapped reads to each of the forward and reverse strands of the genome(s) at single nucleotide resolution. Multiply mapped reads were pro-rated over all highest quality aligned locations. Gene transcript abundance was then measured by summing total reads landing inside annotated gene boundaries or exon boundaries (user selectable, based on quality of exon annotation of each genome), expressed as both RPKM (21), and raw read counts. Two stringencies of gene abundance were provided using all aligned reads and by using just uniquely aligned reads.

Differential Transcription analysis

To minimize biases from the choice of algorithm for calling differential expressed (DE) genes, a panel of 5 DE tools were utilized. They include: 1) Round Robin (in-house) 2) Rank Product (22) 3) Significance Analysis of Microarrays (SAM) (23) 4) EdgeR (24) 5) DESeq (25). Each DE tool was called with appropriate default parameters, and operates on the same set of transcription results, using RPKM abundance units for RoundRobin, RankProduct, and SAM; and raw read count abundance units for DEseq and EdgeR. All 5 DE results were then synthesized, by combining gene DE rank positions across all 5 DE tools. Specifically, a gene’s rank position in all 5 results was averaged, using a generalized mean to the 1/2 power, to yield the gene’s final net rank position. Each DE tool’s explicit measurements of differential expression (fold change) and significance (p-value) was similarly combined via appropriate averaging (arithmetic and geometric mean, respectively). The final DE result was sorted by gene net rank position, so the top genes were those found in common by all DE tools. Sequencing data (accession number: GSE86308, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) is available on the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database.

Mice and experimental procedures

Ten C57Bl/6, γδTCR (B6.129P2-Tcrdtm1Mom/J, γδKO) and BATF3 (129S-Batf3tm1Kmm/J, BATF3KO) knockout mice were vaccinated three times with 104 irradiated P.berghei ANKA sporozoites (SPZ vaccination) at two-week intervals via direct intravenous inoculation (DVI). The same vaccinations were given to groups of ten C57Bl/6 that received the GL3 (depletes γδ T cells) or UC310A6 (depletes Vγ4 γδ T cells) mAb, either prior to each vaccination or just before challenge. For CD8 T cell depletions, mice were administered with the CD8β mAb (Clone: 53–5.8, BioXcell, US) one day prior to challenge. A separate group of C57Bl/6 mice received an isotype control mAb (B81-3) prior to each vaccination. Whole blood was collected for ex vivo assays prior to vaccination, 3 days after each vaccination and 1 day before challenge. Five weeks after the last vaccination, 5 mice in each group were euthanized and the livers and spleens were used for in vitro antigen stimulation assays and ex vivo staining. The remaining mice were challenged by intravenous injection of 103 freshly isolated P. berghei sporozoites and monitored for blood stage parasites from day 3 onwards by microscopy. All experiments were repeated twice.

Intracellular cytokine assays

Livers and spleens were prepared as previously described (26). One million cells, in a final volume of 100ul were plated out and either stimulated with the PbTRAP130 (10ug/ml, Peptide 2.0, USA) or with RPMI media containing 0.001% DMSO as the unstimulated control. Brefeldin A (Sigma, USA) was added to the cells two hours after the initial stimulation and cultured for an additional 16hrs at 37°C and 5% CO2 incubator. After the incubation period, the cells were washed and stained with the aqua viability dye (Invitrogen, USA) for 15 mins. Cells were washed and surface stained with anti-CD3 BV650, CD4 PE-Cy5, CD8 APC-Cy7, γδTCR-PE, KLRG1-PE-Cy7 and CD11a-FITC and incubated for 20 mins. After washing, the cells were prepared for intracellular staining by addition of 200μl of the BD Cytofix/CytoPerm buffer (Becton Dickinson, USA) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The IFN-γ antibody was added to all tubes and incubated for 20 mins. Cells were washed and acquired on the LSRII flow cytometer.

Ex vivo staining of splenocytes and hepatocytes

One million splenocytes or hepatocytes were washed and stained with the aqua viability dye (Invitrogen, USA) for 15 mins. A cocktail of antibodies containing CD3 Pe-Cy5, γδTCR PECF594, CD11c FITC, B220 PE-Cy7, Clec9A PE, CD8 Alexa 700, H2Db (or HLA Class II (A-E)) APC, XCR1 BV650 was prepared and used to stain the cells at room temperature. Cells were washed and acquired immediately on an LSRII flow cytometer.

PbCSP ELISA

The repeat region of the P. berghei circumsporozoite protein (CSP) was a kind gift from Dr. Urszula Krych (WRAIR). The CSP peptide was coated at a concentration of 1ug/ml and incubated overnight at 4C. Serum collected from immunized mice prior to challenge (Study day 65) was used at a 1:100 dilution for the assay. After a 2-hour incubation, the plates were developed using alkaline phosphatase labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (Kirkegaard & Perry Labs, Inc. 1.0mg catalog # 075-1806) and Phosphatase substrate tablets (Sigma, cat. number S0942). Plates were read on a SpectraMax 340PC instrument.

Mosquitoes

4–10 days old female Anopheles stephensi (An. stephensi) mosquitoes were a kind gift from the Laboratory of Malaria Vector Research, NIAID, NIH. The mosquitoes were infected by allowing them to feed on a donor mice (C57BL/6) infected with blood stage P. berghei ANKA parasites. The infected mosquitoes were reared in an environmental chamber set at 19–21°C, 80% relative humidity. The infected mosquitoes were exposed to 150Gy using a cesium irradiator to attenuate the PbSPZ and were dissected to harvest PbSPZ from the salivary glands within 2 hours after irradiation.

Statistics

For pairwise analysis, data were analyzed using the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test. Survival analysis was done using the log-rank test. Differential expression (DE) between groups for the RNAseq analysis was calculated using five independent algorithms (Supplementary materials). Each algorithm ranks the genes by DE using its own criteria (p-value and/or fold change), and rank positions from the 5 algorithms were averaged (generalized mean to the 1/2 power) to give final DE rankings for each gene. The measurements of differential expression (fold change) and significance (p-value) from the 5 algorithms were combined via arithmetic and geometric averaging, respectively.

Study approvals

Written informed consent was received from participants prior to inclusion in the study. All animal studies were approved and performed as per the guidelines of the Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUC) of NIAID/NIH.

RESULTS

Vδ2 T cell percentages are higher in uninfected vaccinees

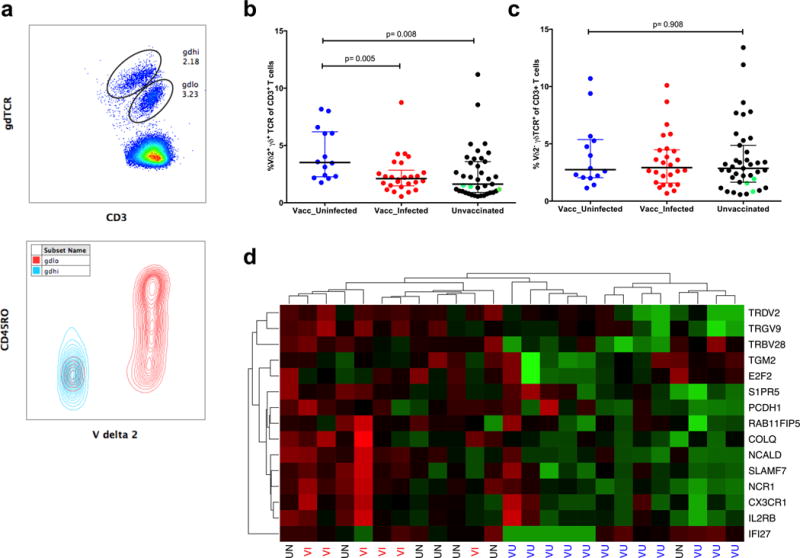

Throughout the PfSPZ Vaccine trial, whole blood samples were used for ex vivo staining to enumerate the proportions of CD4, CD8, and γδ T cells, and of NK cells, and to relate these to protection, but no significant associations were observed (18). Interestingly, two populations of γδ T cells were visible that had varying expression levels of the γδ TCR (Fig 1a, top panel). The γδTCRlo population was enriched for CD45RO expression, suggesting that these might represent the Vδ2 subset (27, 28). Therefore, we enumerated the Vδ2 subset after last vaccine dose and assessed the relationship to protection. Co-staining confirmed that the γδTCRlo subset was enriched for Vδ2 γδ T cells (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

Vδ2 T cell levels after the fifth vaccination were highest in vaccinees who remained uninfected throughout follow-up a) Representative histogram showing two populations of γδ T cells identified by differential levels of γδ TCR expression (top panel) and an overlay of Vδ2 population on total γδ T cells (bottom panel). Comparison of the percentage of (b) Vδ2+γδTCR+ T cells and (c) Vδ2−γδTCR+ T cells in vaccinees who remained uninfected throughout follow-up (blue dots) compared to vaccinees who developed parasitemia (red dots) or to unvaccinated individuals (black dots). Green dots are the unvaccinated individuals who remained uninfected. (d) Heatmap with hierarchical clustering of RNAseq data showing the top 15 genes that were differentially expressed between vaccinated/uninfected (VU), vaccinated/infected (VI) and unvaccinated (UV) study volunteers 3 days after the fifth vaccination. Upregulated genes are denoted in green and downregulated genes are in red.

The percentage of Vδ2 T cells two weeks after the last vaccine dose was significantly higher (p= 0.005, Wilcoxon Rank-sum test) in vaccinees who remained uninfected throughout the transmission season (median: 3.255 IQR: 1.688–6.725), compared to vaccinees who became infected (median: 1.82, IQR: 1.365–2.40) or to controls (median: 1.85 IQR: 0.98–3.43, p= 0.008) (Fig. 1b). Similarly, the absolute numbers of Vδ2 T cells were higher in protected vaccinees compared to vaccinees who became infected or to controls (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Levels of non-Vδ2 γδ T cells did not differ between groups (p= 0.908, Fig. 1c). Activation of Vδ2 cells (measured by CD38 co-expression, Supplementary Figure 1b) was significantly higher in the vaccinated compared to the control group (p=0.04, Supplementary Fig. 1c) two weeks after the fifth vaccination but did not differ between the uninfected and infected vaccinees. The data indicate that Vδ2 cell numbers predict protection against naturally occurring infection, similar to the relationship seen between Vδ2 percentages and protection from homologous CHMI in U.S. vaccinees (4).

Vγ9 and Vδ2 transcripts ranked as the most upregulated genes

To characterize global differences in host response profiles, RNA was purified and sequenced from whole blood of vaccinees who remained uninfected (n=12), vaccinees who became infected (n=6) and unvaccinated subjects (n=7), three days after the last vaccination. Strikingly, the Vγ9 and Vδ2 genes were ranked as the most upregulated genes, being highest in the uninfected vaccinees, and their expression profile across subjects was most similar by hierarchical clustering (Fig. 1d). These data supported the findings from the ex vivo assays that Vδ2 T cells were associated with protection. Other genes in the top 15 included those associated with regulation of proliferative responses (TGM2, SIPR5), a marker of plasma cells and activated γδ T cells (SLAMF7) (27) and activating receptor for NK cells (NCR1).

Absence of γδ T cells during vaccination abrogates protection

To elucidate the role of γδ T cells we utilized a mouse model of sterile protection against Plasmodium challenge that requires CD8 T cells for protection (29, 30). Vaccination with irradiated P. berghei sporozoites were carried out in wild type C57BL/6 mice, γδKO mice and C57BL/6 mice depleted of either all γδ T cells or the Vγ4 subset alone, using the GL3 and UC310A6 mAb respectively (Table 1). The total number of circulating white blood cells measured 3 days after last vaccination was similar between mice in the different groups (Supplementary Fig.2a).

Table 1.

Summary of the groups of mice, vaccine regimens and protection observed during the study

| Group | Type | Irradiated PbSPZ | Days of vaccination | Antibody administered | Day of antibody injection | Protected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | BATF3KO | 104 × 3 | 0,14,28 | nil | 0/10 | |

| 2 | γδ KO | 104 × 3 | 0,14,28 | nil | 0/10 | |

| 3 | C57Bl/6 | 104 × 3 | 0,14,28 | nil | 10/10 | |

| 4 | C57Bl/6 | 104 × 3 | 0,14,28 | B81-3 | −1,13,27 | 10/10 |

| 5 | C57Bl/6 | 104 × 3 | 0,14,28 | GL3 | −1,13,27 | 0/10 |

| 6 | C57Bl/6 | 104 × 3 | 0,14,28 | GL3 | 65 | 10/10 |

| 7 | C57Bl/6 | 104 × 3 | 0,14,28 | UC310A6 | −1,13,27 | 10/10 |

| 8 | C57Bl/6 | 104 × 3 | 0,14,28 | UC310A6 | 65 | 10/10 |

| 9 | C57Bl/6 | Nil | nil | nil | 0/10 |

Mice in Groups 1–8 were vaccinated with 104 irradiated P. berghei sporozoites three times at two- week intervals. Mice in group 4 received an isotype control (anti-KLH) antibody before each vaccination. Mice in groups 5 and 6 were administered the GL3 mAb to deplete γδ T cells one day prior to each vaccination and just before challenge respectively. Mice in groups 7 and 8 received the UC310A6 mAb to deplete Vγ4+ γδ T cells one day prior to each vaccination and just before challenge respectively. Mice in group 9 were the infection controls. The data is from two independent experiments.

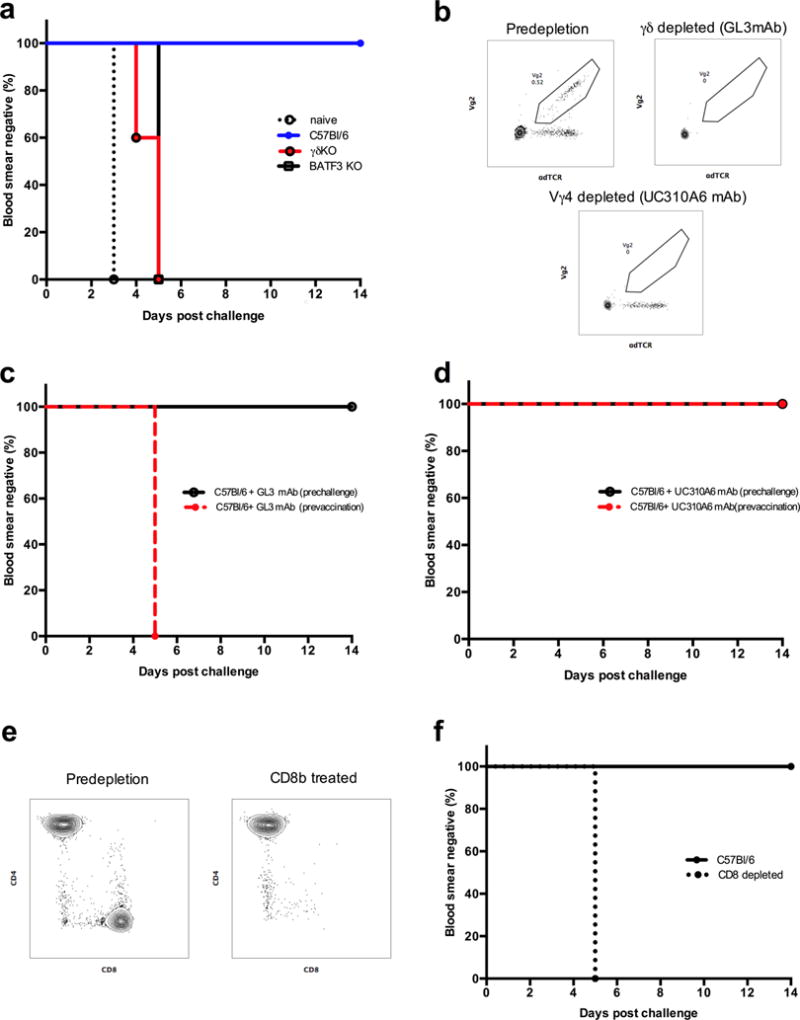

Five mice in each group were challenged with 103 freshly isolated P. berghei sporozoites five weeks after the third vaccination. All unvaccinated naïve mice became infected and blood-stage parasites appeared at day 3 post-infection, while all the wild-type and the control mAb-treated C57Bl/6 mice were protected and showed no evidence of blood stage parasitemia during 14 days of follow-up after challenge. All the γδKO mice became parasitemic by day 5 post-challenge, establishing that γδ T cells are required for sterile immunity. As previously reported (31), BATF3KO mice, which lack CD8α+ DC, also failed to develop protective immunity (Fig. 2a). Administration of either GL3 mAb or UC310A6 mAb resulted in complete depletion of total γδ T cells or Vγ4 subset respectively (Fig. 2b). γδ T cells were required for the induction of effective immunity, because C57Bl/6 mice administered the GL3 mAb during vaccination but not at the time of challenge showed no protection (Fig 2c). All mice that received the UC310A6 mAb, either during vaccination or prior to challenge, were protected after challenge, indicating that the Vγ4 subset of γδ T cells is not required for induction of protective immunity (Fig. 2d). The same results were obtained in a repeat experiment. To confirm that CD8 T cells were required for protection, previously protected animals had their CD8 T cells depleted (Figure 2e) and then were rechallenged. As expected, depletion of CD8 T cells resulted in the loss of protection (Fig. 2f and (29)).

Figure 2.

Comparison of sterile protection after PbSPZ challenge in a) vaccinated C57Bl/6, γδ KO and BATF3KO mice. b) Representative flow cytometry plots showing the depletion of total γδ T cells and Vγ4+ T cells after administration of the GL3 and UC310A6 mAb respectively. c) Comparison of sterile protection in mice depleted of total γδ T cells using the GL3 mAb prior to each vaccination or before challenge. d) Comparison of sterile protection in mice depleted of the Vγ4+ γδ T cells using the UC310A6 mAb prior to each vaccination or before challenge. e) Representative flow cytometry plots of CD8 depletions in protected mice. f) Effect of CD8 depletion on protection after rechallenge. Sterile protection was defined as absence of blood stage parasitemia after challenge with 103 P. berghei ANKA sporozoites. All vaccination studies were done twice.

Impaired induction of T cell but not CSP-specific antibody responses in the absence of γδ T cells

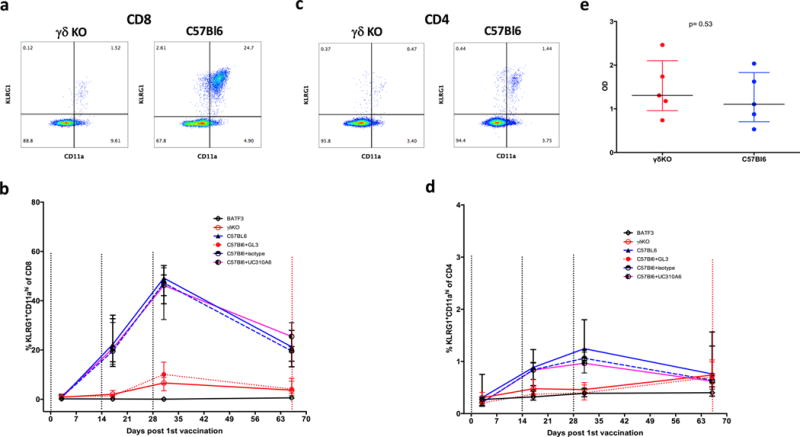

We examined the requirement for γδ T cells during vaccination to induce αβ T cell and antibody responses. Activated CD4 and CD8 T cells were defined by the co-expression of CD11a and KLRG1 as previously described (26, 30). The levels of activated T cells were measured in the blood of all mice 3 days after each vaccination and just before challenge (day 66).

There was no expansion of either T cell subset in BATF3KO mice. Levels of activated CD8 and CD4 T cells were significantly higher in γδKO mice or in C57Bl/6 mice treated with GL3 than in BATF3KO mice (p<0.001, Mann-Whitney U test), but were significantly lower than in wild-type C57Bl/6 and UC310A6 treated C57Bl/6 mice (Fig. 3b and d, p<0.001 for all comparisons). Antibody responses were measured against the immunodominant repeat region of P. berghei CSP in γδKO mice and wild-type mice, using sera collected on study day 66 (pre-challenge). Antibody titers (expressed as OD values) in wild-type or γδKO mice did not significantly differ (Fig 3e). Taken together, the evidence indicates that γδ T cells are required for the induction of protective CD8 T cell responses, but not of CSP-specific antibody responses to SPZ vaccination.

Figure 3. γδ T cells were required during irradiated PbSPZ vaccination to induce effector αβ T cells.

Representative flow plot of (a) CD8+CD11ahiKLRG1+ cells and (c) CD4+CD11ahiKLRG1+ cells in the γδKO mice and C57Bl/6 mice in whole blood at Day 31 (3 days after last vaccination). Comparison of the percentage of (b) CD8+CD11ahiKLRG1+ and (d) CD4+CD11ahiKLRG1+ in C57Bl/6 mice treated with GL3 mAb (red dashed line), C57Bl/6 mice treated with UC310A6 mAb (purple solid line), γδKO (red solid line), BATF3KO (black line) control C57Bl/6 mice that did (blue solid line) or did not receive anti-KLH (“isotype” blue dashed line) mAb. N=10 in each group. Data are presented as medians with interquartile ranges measured 3 days after each vaccination (days 3,17 and 31) and the day of challenge (day 66). (e) Comparison of antibody titers (expressed as OD) to the repeat region of the P. berghei CSP in sera from γδKO and C57Bl/6 mice at day 66.

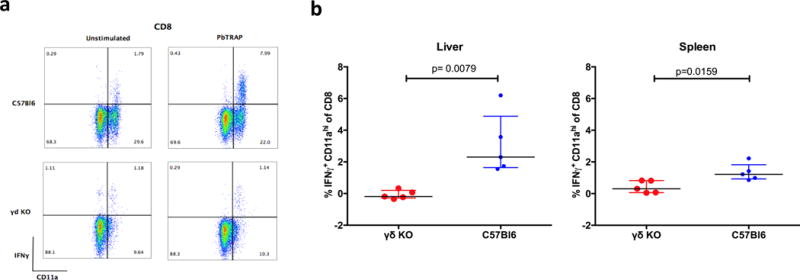

Reduced TRAP130 specific CD8 T cell responses in livers and spleens in γδKO mice

We next determined the levels of antigen-specific T cell responses in livers and spleens of vaccinated mice from γδKO and wild type C57Bl/6 mice. Cells from livers and spleens were stimulated overnight with the PbTRAP130 peptide (32) and CD8+IFNγ+ cells were enumerated. Interestingly, PbTRAP130-specific CD8 T cells were in the CD11ahi subset (Fig. 4a) and were significantly more frequent in the livers of C57Bl/6 (median: 2.3% IQR: 1.64 – 4.89) compared to γδKO mice (median: −0.19% IQR: −1.19 – 0.33) (p=0.0001, Fig 4b). Similarly, the percentage of PbTRAP130 -specific CD8+IFNγ+ T cells was higher in the spleens of C57Bl/6 compared to γδKO mice (medians: 1.1% versus 0.30%, p = 0.016, Fig.4b). These data demonstrate that accumulation of Plasmodium-specific T cells is impaired in the absence of γδ T cells during SPZ vaccination.

Figure 4. Absence of γδ T cells impaired antigen-specific immune responses and protection from infectious challenge.

(a) Representative flow plots of liver cells gated on CD8 showing the percentage of IFNγ+ events in the unstimulated and PfTRAP130 peptide-stimulated cells in C57Bl/6 and γδKO mice. (b) Comparison of IFNγ+ CD8 T cells in γδKO (red) and C57Bl/6 mice (blue) in the liver and spleen. The values shown were determined by subtracting the control unstimulated from the PbTRAP130 stimulated samples. Data are presented as medians with interquartile ranges.

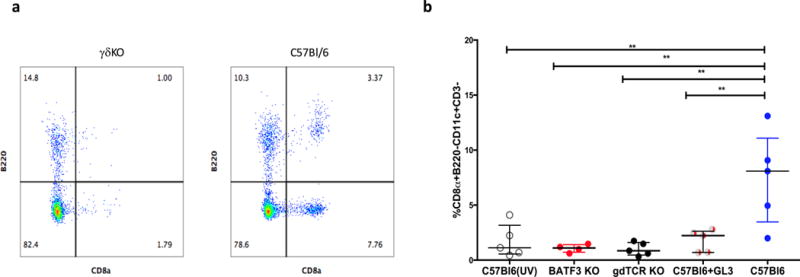

Reduced accumulation of CD8α+ DC in the livers of vaccinated γδKO mice

The above data showed that both γδ T cells and CD8α+ DC are required to induce protective immune effectors. We sought to clarify their independent or interacting roles for induction of protective immune responses. CD8α+ DC were enumerated in the livers of wild-type C57Bl/6, BATF3KO, GL3 treated C57Bl/6 mice and γδKO mice. CD8α+ DC cells were defined as CD11c+CD8+B220− CD3−NK1.1− (Fig. 5a) as previously described (31). Following vaccination CD8α+ DCs were increased in the livers of wild-type C57Bl/6 mice compared to unvaccinated mice. Similarly, vaccinated γδKO and GL3 treated C57Bl/6 mice had substantially reduced percentages (p=0.016, Fig. 5b) and numbers (p=0.04, Supplementary Fig. 2b) of CD8α+ DCs compared to wild-type C57Bl/6 mice. The results suggest that γδ T cells are required for accumulation of CD8α+ DC in the liver during the response to SPZ vaccination.

Figure 5. CD8α+ DC and B220+ γδ T cells in SPZ vaccinated mice.

(a) Representative flow cytometry plot of CD8α DC in the liver identified as CD8+B220− in γδKO and C57Bl/6 mice (D66). Events were gated on CD3−CD11c+. (b) Comparison of CD8+B220− cell percentage in C57Bl/6, γδKO, BATF3KO and C57Bl/6 treated with GL3 mAb.

Discussion

Vaccine confers sterilizing immunity against homologous infection in malaria naïve subjects (2, 4). In the recently concluded PfSPZ trial in Mali, we demonstrated vaccine-induced protection against naturally occurring infections (18), which allowed us to examine correlates of immunity. In malaria-naïve vaccinees CSP antibody responses and fold increases of γδ T cell levels associated with protection against homologous challenge (2, 4). In Malian vaccinees who remained uninfected throughout our follow-up, neither response was convincing as a correlate of protection. The anti-CSP antibody titers were modest compared to U.S. vaccinees, and total γδ T cell levels were not significantly elevated (18). Here, we used human data and animal models to provide definitive evidence that a subset of γδ T cells are required for the induction of protective CD8 T cell responses, but do not themselves function as effectors mediating protection.

During the Mali trial, levels of γδ T cells were enumerated ex vivo along with other immune subsets using peripheral blood samples. The Vδ2 subset had lower expression of the γδTCR and a subset expressed CD45RO, which is consistent with a memory phenotype (27, 28). This prompted us to measure the Vδ2 subset in all study participants after the final vaccination. Vaccinees who remained uninfected during follow up had a significantly higher percentage of Vδ2 T cells than vaccinees that became infected or the placebo group. Strikingly, the Vδ2 and Vγ9 transcript levels were also the most highly upregulated genes in the vaccinees who remained uninfected, independently supporting the association of Vδ2 T cells with protection. Our results concur with the recent finding that the expansion of Vδ2 T cells during vaccination of malaria-naïve vaccinees is greatest among those who become protected from infection with homologous parasites (4). Taken together, these results highlight that Vδ2 T cells could be a valuable biomarker during PfSPZ vaccination in malaria endemic populations.

γδ T cells may have diverse functions during vaccinations. For example, BCG-expanded human Vδ2 T cells can function as effectors (33), as accessory cells for antigen presenting cells, or as antigen presenting cells (34). Vδ2 T cells can be activated by P. falciparum (35, 36) and lyse infected erythrocytes in their role as effectors (12). In addition, it has been shown that in vitro, Vδ2 T cells can induce CD8 T cell responses to P. falciparum antigens (37). To elucidate the precise role of γδ T cells during PfSPZ vaccination, we utilized a mouse model of SPZ vaccination that confers sterile protection and is dependent on CD8 T cells. The γδ T cell subpopulation in mice that corresponds to the human Vδ2 T cell subset has not been defined, and therefore all γδ T cells were depleted initially. These experiments clearly demonstrated that γδ T cells were not required as effector cells, inasmuch as depletion of these cells just before infectious challenge had no impact on protection.

Instead, γδ T cells were essential during vaccination to induce effector CD8 T cells that mediated sterile protection. In the absence of γδ T cells during vaccination, there was diminished activation of CD8 T cells in the periphery and reduced numbers of PbTRAP130 specific CD8 T cells in the liver and the spleen that are required for sterile immunity (38). Since we did not specifically stain for markers of tissue resident T cells, we cannot exclude the possibility that some of these responses are due to circulating effector memory T cells.

The absence of γδ T cells did not affect antibody titers to the immunodominant P. berghei CSP repeat region. Although γδ T cells can assist in induction of humoral responses (39–41), previous studies showed that antibody titers are not impaired in γδ T cell deficient mice after oral immunization (42), similar to what we have observed in our model. These results clearly show that induction of protective CD8 T cells, but not CSP-specific antibodies, is dependent on the presence of γδ T cells during SPZ vaccination. A caveat to our results is the possibility that the GL3 mAb we used may not deplete γδ T cells but instead leads to downregulation of the TCR receptor as reported by one study (43). We found consistent results in the γδ knockout mice and C57Bl/6 mice that received the GL3 mAb. In both these mice, SPZ vaccination did not lead to induction of effector CD8 T cells and consequently they were not protected after challenge. Also, studies in multiple models have demonstrated that, at the very least, treatment with GL3 leads to functional impairment of γδT cells (44, 45). The fact that sterile immunity was not perturbed in mice that were treated with the GL3 mAb just prior to challenge strongly suggests that γδ T cells are not required as effectors for control of parasite replication in the liver.

We next attempted to identify the subset of γδ T cells in mice that were responsible for induction of protective immunity. We focused on the Vγ4+ subset since they were required for induction of CD8 T cells in a BCG vaccination model (46). Depletion of Vγ4 γδ T cells in our model had no effect on induction of sterile immunity. Further studies are needed to identify the γδ T cell subset that is required during the induction of effector CD8 T cell responses.

CD8α+ DCs have are required for protection induced by SPZ vaccines (31, 47) and we replicated those findings here. We therefore examined the CD8α+ DC in the liver after SPZ vaccine in the absence of γδ T cells. Absence of γδ T cells during vaccinations was associated with a dramatic reduction of CD8α+ DC numbers in the livers of vaccinated mice. These findings are consistent with those of Montagna et al., (31) who similarly showed accumulation of CD8α+ DCs in the liver in protected mice. This suggests that γδ T cells are required for the expansion of CD8α+ DC in the liver either by facilitating their migration or supporting their proliferation. Our results are suggestive and we cannot conclude that there is direct interaction between γδ T cells and CD8α+ DC, or that this solely occurs in the liver. Further experiments are required to tease out the precise location and interaction of CD8α+ DCs and γδ T cells during the induction of protective CD8 T cell responses that impart sterile immunity. Taken together the data from this study suggest that crosstalk between γδ T cells and CD8α+ DC is required for induction of downstream effector T cell responses during SPZ vaccination. While we did not examine the role of CD4 T cells in this study, there is ample evidence to show that they are also required for induction of protective CD8 T cell responses (48).

In summary, we showed that the Vδ2 T cells are elevated in vaccinees with prior exposure to malaria that showed evidence of protection against natural infection. In murine vaccination studies, we definitively demonstrated that a subset of γδ T cells, along with CD8α+ DC, are required for the induction of protective immunity by SPZ vaccination, but not as direct effectors. The understanding that γδ T cells are required for induction of protective CD8 T cell responses can guide strategies to improve the efficacy of SPZ vaccines in malaria exposed populations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Eric James, Peter Billingsley, Anita Manoj and Yonas Abebe for PfSPZ Vaccine preparations, quality assurance and logistics in Mali, and we acknowledge the support from the Sanaria Manufacturing, Quality, Regulatory and Clinical Teams. We acknowledge the support from Richard Sakai and Sharon Wong-Madden during the vaccine trial in Mali. We would like to thank Jean Langhorne and J. Patrick Gorres for reviewing the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of NIAID, National Institutes of Health. Production and characterization of the Sanaria PfSPZ vaccine were supported in part by NIAID Small Business Innovation Research grants 5R44AI055229 and 5R44AI058499.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Human studies were conducted by IZ and HD, IZ, SC, DC, LL, BB, JK, SO, YR conducted the mouse experiments. IZ, SC, PD, SLH, BKS, SH, MS, OKD designed the studies. EB and RM conducted the statistical analysis. IZ, PD and SLH wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Epstein JE, Tewari K, Lyke KE, Sim BK, Billingsley PF, Laurens MB, Gunasekera A, Chakravarty S, James ER, Sedegah M, Richman A, Velmurugan S, Reyes S, Li M, Tucker K, Ahumada A, Ruben AJ, Li T, Stafford R, Eappen AG, Tamminga C, Bennett JW, Ockenhouse CF, Murphy JR, Komisar J, Thomas N, Loyevsky M, Birkett A, Plowe CV, Loucq C, Edelman R, Richie TL, Seder RA, Hoffman SL. Live attenuated malaria vaccine designed to protect through hepatic CD8(+) T cell immunity. Science. 2011;334:475–480. doi: 10.1126/science.1211548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seder RA, Chang LJ, Enama ME, Zephir KL, Sarwar UN, Gordon IJ, Holman LA, James ER, Billingsley PF, Gunasekera A, Richman A, Chakravarty S, Manoj A, Velmurugan S, Li M, Ruben AJ, Li T, Eappen AG, Stafford RE, Plummer SH, Hendel CS, Novik L, Costner PJ, Mendoza FH, Saunders JG, Nason MC, Richardson JH, Murphy J, Davidson SA, Richie TL, Sedegah M, Sutamihardja A, Fahle GA, Lyke KE, Laurens MB, Roederer M, Tewari K, Epstein JE, Sim BK, Ledgerwood JE, Graham BS, Hoffman SL, V. R. C. S. Team Protection against malaria by intravenous immunization with a nonreplicating sporozoite vaccine. Science. 2013;341:1359–1365. doi: 10.1126/science.1241800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoffman SL, Billingsley PF, James E, Richman A, Loyevsky M, Li T, Chakravarty S, Gunasekera A, Chattopadhyay R, Li M, Stafford R, Ahumada A, Epstein JE, Sedegah M, Reyes S, Richie TL, Lyke KE, Edelman R, Laurens MB, Plowe CV, Sim BK. Development of a metabolically active, non-replicating sporozoite vaccine to prevent Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Hum Vaccin. 2010;6:97–106. doi: 10.4161/hv.6.1.10396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishizuka AS, Lyke KE, DeZure A, Berry AA, Richie TL, Mendoza FH, Enama ME, Gordon IJ, Chang LJ, Sarwar UN, Zephir KL, Holman LA, James ER, Billingsley PF, Gunasekera A, Chakravarty S, Manoj A, Li M, Ruben AJ, Li T, Eappen AG, Stafford RE, CN K, Murshedkar T, DeCederfelt H, Plummer SH, Hendel CS, Novik L, Costner PJ, Saunders JG, Laurens MB, Plowe CV, Flynn B, Whalen WR, Todd JP, Noor J, Rao S, Sierra-Davidson K, Lynn GM, Epstein JE, Kemp MA, Fahle GA, Mikolajczak SA, Fishbaugher M, Sack BK, Kappe SH, Davidson SA, Garver LS, Bjorkstrom NK, Nason MC, Graham BS, Roederer M, Sim BK, Hoffman SL, Ledgerwood JE, Seder RA. Protection against malaria at 1year and immune correlates following PfSPZ vaccination. Nat Med. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nm.4110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holtmeier W, Kabelitz D. gammadelta T cells link innate and adaptive immune responses. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2005;86:151–183. doi: 10.1159/000086659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayday AC. [gamma][delta] cells: a right time and a right place for a conserved third way of protection. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:975–1026. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carding SR, Egan PJ. Gammadelta T cells: functional plasticity and heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:336–345. doi: 10.1038/nri797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uldrich AP, Le Nours J, Pellicci DG, Gherardin NA, McPherson KG, Lim RT, Patel O, Beddoe T, Gras S, Rossjohn J, Godfrey DI. CD1d-lipid antigen recognition by the gammadelta TCR. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:1137–1145. doi: 10.1038/ni.2713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sandstrom A, Peigne CM, Leger A, Crooks JE, Konczak F, Gesnel MC, Breathnach R, Bonneville M, Scotet E, Adams EJ. The intracellular B30.2 domain of butyrophilin 3A1 binds phosphoantigens to mediate activation of human Vgamma9Vdelta2 T cells. Immunity. 2014;40:490–500. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Langhorne J, Goodier M, Behr C, Dubois P. Is there a role for gamma delta T cells in malaria? Immunol Today. 1992;13:298–300. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guenot M, Loizon S, Howard J, Costa G, Baker DA, Mohabeer SY, Troye-Blomberg M, Moreau JF, Dechanet-Merville J, Mercereau-Puijalon O, Mamani-Matsuda M, Behr C. Phosphoantigen Burst Upon Plasmodium Falciparum Schizont Rupture Can Distantly Activate Vgamma9-Vdelta2 T-Cells. Infect Immun. 2015 doi: 10.1128/IAI.00446-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costa G, Loizon S, Guenot M, Mocan I, Halary F, de Saint-Basile G, Pitard V, Dechanet-Merville J, Moreau JF, Troye-Blomberg M, Mercereau-Puijalon O, Behr C. Control of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocytic cycle: gammadelta T cells target the red blood cell-invasive merozoites. Blood. 2011;118:6952–6962. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-376111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Behr C, Poupot R, Peyrat MA, Poquet Y, Constant P, Dubois P, Bonneville M, Fournie JJ. Plasmodium falciparum stimuli for human gammadelta T cells are related to phosphorylated antigens of mycobacteria. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2892–2896. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.2892-2896.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Behr C, Dubois P. Preferential expansion of V gamma 9 V delta 2 T cells following stimulation of peripheral blood lymphocytes with extracts of Plasmodium falciparum. Int Immunol. 1992;4:361–366. doi: 10.1093/intimm/4.3.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsuji M, Mombaerts P, Lefrancois L, Nussenzweig RS, Zavala F, Tonegawa S. Gamma delta T cells contribute to immunity against the liver stages of malaria in alpha beta T-cell-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:345–349. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brandes M, Willimann K, Moser B. Professional antigen-presentation function by human gammadelta T Cells. Science. 2005;309:264–268. doi: 10.1126/science.1110267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brandes M, Willimann K, Bioley G, Levy N, Eberl M, Luo M, Tampe R, Levy F, Romero P, Moser B. Cross-presenting human gammadelta T cells induce robust CD8+ alphabeta T cell responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2307–2312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810059106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sissoko MS, Healy SA, Katile A, Omaswa F, Zaidi I, Gabriel EE, Kamate B, Samake Y, Guindo MA, Dolo A, Niangaly A, Niare K, Zeguime A, Sissoko K, Diallo H, Thera I, Ding K, Fay MP, O’Connell EM, Nutman TB, Wong-Madden S, Murshedkar T, Ruben AJ, Li M, Abebe Y, Manoj A, Gunasekera A, Chakravarty S, Sim BK, Billingsley PF, James ER, Walther M, Richie TL, Hoffman SL, Doumbo O, Duffy PE. Safety and efficacy of PfSPZ Vaccine against Plasmodium falciparum via direct venous inoculation in healthy malaria-exposed adults. Mali: a randomised, double-blind phase 1 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30104-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vignali M, Armour CD, Chen J, Morrison R, Castle JC, Biery MC, Bouzek H, Moon W, Babak T, Fried M, Raymond CK, Duffy PE. NSR-seq transcriptional profiling enables identification of a gene signature of Plasmodium falciparum parasites infecting children. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:1119–1129. doi: 10.1172/JCI43457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wold B, Myers RM. Sequence census methods for functional genomics. Nat Methods. 2008;5:19–21. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Breitling R, Armengaud P, Amtmann A, Herzyk P. Rank products: a simple, yet powerful, new method to detect differentially regulated genes in replicated microarray experiments. FEBS Lett. 2004;573:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tusher VG, Tibshirani R, Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:5116–5121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson MD, Smyth GK. Small-sample estimation of negative binomial dispersion, with applications to SAGE data. Biostatistics. 2008;9:321–332. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxm030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doll KL, Butler NS, Harty JT. Tracking the total CD8 T cell response following whole Plasmodium vaccination. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;923:493–504. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-026-7_34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jagannathan P, Kim CC, Greenhouse B, Nankya F, Bowen K, Eccles-James I, Muhindo MK, Arinaitwe E, Tappero JW, Kamya MR, Dorsey G, Feeney ME. Loss and dysfunction of Vdelta2(+) gammadelta T cells are associated with clinical tolerance to malaria. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:251ra117. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyawaki T, Kasahara Y, Taga K, Yachie A, Taniguchi N. Differential expression of CD45RO (UCHL1) and its functional relevance in two subpopulations of circulating TCR-gamma/delta+ lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1990;171:1833–1838. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.5.1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weiss WR, Sedegah M, Beaudoin RL, Miller LH, Good MF. CD8+ T cells (cytotoxic/suppressors) are required for protection in mice immunized with malaria sporozoites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:573–576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zarling S, Krzych U. Characterization of Liver CD8 T Cell Subsets that are Associated with Protection Against Pre-erythrocytic Plasmodium Parasites. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1325:39–48. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2815-6_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Montagna GN, Biswas A, Hildner K, Matuschewski K, Dunay IR. Batf3 deficiency proves the pivotal role of CD8alpha+ dendritic cells in protection induced by vaccination with attenuated Plasmodium sporozoites. Parasite Immunol. 2015 doi: 10.1111/pim.12222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hafalla JC, Bauza K, Friesen J, Gonzalez-Aseguinolaza G, Hill AV, Matuschewski K. Identification of targets of CD8(+) T cell responses to malaria liver stages by genome-wide epitope profiling. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003303. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spencer CT, Abate G, Blazevic A, Hoft DF. Only a subset of phosphoantigen-responsive gamma9delta2 T cells mediate protective tuberculosis immunity. J Immunol. 2008;181:4471–4484. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abate G, Spencer CT, Hamzabegovic F, Blazevic A, Xia M, Hoft DF. Mycobacterium-Specific gamma9delta2 T Cells Mediate Both Pathogen-Inhibitory and CD40 Ligand-Dependent Antigen Presentation Effects Important for Tuberculosis Immunity. Infect Immun. 2016;84:580–589. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01262-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guenot M, Loizon S, Howard J, Costa G, Baker DA, Mohabeer SY, Troye-Blomberg M, Moreau JF, Dechanet-Merville J, Mercereau-Puijalon O, Mamani-Matsuda M, Behr C. Phosphoantigen Burst upon Plasmodium falciparum Schizont Rupture Can Distantly Activate Vgamma9Vdelta2 T Cells. Infect Immun. 2015;83:3816–3824. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00446-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones SM, Goodier MR, Langhorne J. The response of gamma delta T cells to Plasmodium falciparum is dependent on activated CD4+ T cells and the recognition of MHC class I molecules. Immunology. 1996;89:405–412. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.d01-762.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Howard J, Loizon S, Tyler CJ, Duluc D, Moser B, Mechain M, Duvignaud A, Malvy D, Troye-Blomberg M, Moreau JF, Eberl M, Mercereau-Puijalon O, Dechanet-Merville J, Behr C, Mamani-Matsuda M. The Antigen-Presenting Potential of Vgamma9Vdelta2 T Cells During Plasmodium falciparum Blood-Stage Infection. J Infect Dis. 2017;215:1569–1579. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doll KL, Pewe LL, Kurup SP, Harty JT. Discriminating Protective from Nonprotective Plasmodium-Specific CD8+ T Cell Responses. J Immunol. 2016;196:4253–4262. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bansal RR, Mackay CR, Moser B, Eberl M. IL-21 enhances the potential of human gammadelta T cells to provide B-cell help. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:110–119. doi: 10.1002/eji.201142017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dianda L, Gulbranson-Judge A, Pao W, Hayday AC, MacLennan IC, Owen MJ. Germinal center formation in mice lacking alpha beta T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1603–1607. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wen L, Pao W, Wong FS, Peng Q, Craft J, Zheng B, Kelsoe G, Dianda L, Owen MJ, Hayday AC. Germinal center formation, immunoglobulin class switching, and autoantibody production driven by “non alpha/beta” T cells. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2271–2282. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fujihashi K, McGhee JR, Kweon MN, Cooper MD, Tonegawa S, Takahashi I, Hiroi T, Mestecky J, Kiyono H. gamma/delta T cell-deficient mice have impaired mucosal immunoglobulin A responses. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1929–1935. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koenecke C, Chennupati V, Schmitz S, Malissen B, Forster R, Prinz I. In vivo application of mAb directed against the gammadelta TCR does not deplete but generates “invisible” gammadelta T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:372–379. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glanville N, Message SD, Walton RP, Pearson RM, Parker HL, Laza-Stanca V, Mallia P, Kebadze T, Contoli M, Kon OM, Papi A, Stanciu LA, Johnston SL, Bartlett NW. gammadeltaT cells suppress inflammation and disease during rhinovirus-induced asthma exacerbations. Mucosal Immunol. 2013;6:1091–1100. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murdoch JR, Lloyd CM. Resolution of allergic airway inflammation and airway hyperreactivity is mediated by IL-17-producing {gamma}{delta}T cells. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:464–476. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200911-1775OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakamizo S, Egawa G, Tomura M, Sakai S, Tsuchiya S, Kitoh A, Honda T, Otsuka A, Nakajima S, Dainichi T, Tanizaki H, Mitsuyama M, Sugimoto Y, Kawai K, Yoshikai Y, Miyachi Y, Kabashima K. Dermal Vgamma4(+) gammadelta T cells possess a migratory potency to the draining lymph nodes and modulate CD8(+) T-cell activity through TNF-alpha production. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:1007–1015. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Radtke AJ, Kastenmuller W, Espinosa DA, Gerner MY, Tse SW, Sinnis P, Germain RN, Zavala FP, Cockburn IA. Lymph-node resident CD8alpha+ dendritic cells capture antigens from migratory malaria sporozoites and induce CD8+ T cell responses. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004637. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weiss WR, Sedegah M, Berzofsky JA, Hoffman SL. The role of CD4+ T cells in immunity to malaria sporozoites. J Immunol. 1993;151:2690–2698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.