Abstract

Bats perform important ecosystem services, but it remains difficult to quantify their dietary strategies and trophic position (TP) in situ. We conducted measurements of nitrogen isotopes of individual amino acids (δ 15NAA) and bulk-tissue carbon (δ 13Cbulk) and nitrogen (δ 15Nbulk) isotopes for nine bat species from different feeding guilds (nectarivory, frugivory, sanguivory, piscivory, carnivory, and insectivory). Our objective was to assess the precision of δ 15NAA-based estimates of TP relative to other approaches. TPs calculated from δ 15N values of glutamic acid and phenylalanine, which range from 8.3–33.1‰ and 0.7–15.4‰ respectively, varied between 1.8 and 3.8 for individuals of each species and were generally within the ranges of those anticipated based on qualitative dietary information. The δ 15NAA approach reveals variation in TP within and among species that is not apparent from δ 15Nbulk data, and δ 15NAA data suggest that two insectivorous species (Lasiurus noctivagans and Lasiurus cinereus) are more omnivorous than previously thought. These results indicate that bats exhibit a trophic discrimination factor (TDF) similar to other terrestrial organisms and that δ 15NAA provides a reliable approach for addressing questions about variation in the TP of bats that have heretofore proven elusive.

Introduction

Bats exhibit a diversity of feeding strategies, including nectarivory, frugivory, sanguivory, piscivory, carnivory, and insectivory. In doing so they carry out ecosystem services of ecological and socioeconomic importance, such as pollination and insect predation (e.g.1,2). Within and among these broad feeding guilds there exists variation in the extent to which different species are dietary specialists versus generalists (e.g.3–6). Knowledge of the dietary complexity and requirements of bats is important to assess their behavior, ecological and evolutionary processes, and susceptibility to extirpation or extinction (e.g.7–11). However, there remains limited understanding of how the dietary strategies of most organisms, including bats, vary across space and time in nature.

A primary reason for the lack of understanding of the dietary strategies of many species is the limitation of existing approaches for inferring dietary strategies. Direct observation and characterization of feeding behavior in situ is typically uncommon outside of experimental settings. Indirect assessments of animal diets are more common, but suffer from limitations. For example, morphological analysis of stomach contents or fecal material can provide precise dietary information. However, such approaches are labor-intensive, skewed toward detecting identifiable prey parts, and provide only a snapshot of a recent meal. DNA-based analyses of gut and/or fecal material can provide detailed dietary information (e.g.12), but also indicate only recently consumed resources and are typically non-quantifiable. Stable isotope ratios of carbon and nitrogen (δ 13Cbulk and δ 15Nbulk, respectively) in animal tissues provide a more spatiotemporally integrated and inexpensive assessment of diet, and have become an important tool to enhance understanding of the prey items and trophic positions (TP) of wildlife, including bats (e.g.4,13–16). However, a challenge to interpreting such data in the context of TP is that the isotope values of a consumer’s tissues inherently reflect changes related to both the consumer’s TP and to the isotope values of the primary producers (autotrophs) at the base of the consumer’s food web, the latter of which can vary spatially and/or temporally and are often unknown17. This issue concerning interpretation of TP from δ 15Nbulk may be particularly important for mobile organisms, such as bats, that feed across broad spatial scales on potentially isotopically distinct food webs (e.g.8,17,18).

Analysis of δ 15N values of individual amino acids (δ 15NAA) emerged within the last ~15 years as a valuable tool for improving assessment of the trophic status of organisms in marine, freshwater, and terrestrial ecosystems (e.g.18–22). The basis of this method is that in certain amino acids (called “trophic” amino acids), the transamination and deamination reactions that form and cleave C-N bonds lead to isotopic fractionations and more positive δ 15N values at higher trophic levels. In contrast, C-N bonds are not created or broken during the metabolic processing of a few amino acids that are only biosynthesized by autotrophs (called “source” amino acids), which means that they confer little shift in δ 15N values across trophic levels20,23 and thus integrate the δ 15N values of the autotrophs eaten by consumers in food webs. Two common amino acids that are representative of trophic and source amino acids are glutamic acid and phenylalanine, respectively. Assuming similar turnover times (or periods of integration) for trophic and source amino acids, the TP of an organism can be estimated from its δ 15N values of glutamic acid (δ 15NGlu) and phenylalanine (δ 15NPhe) as

| 1 |

where β represents the difference between δ 15NGlu and δ 15NPhe in autotrophs, and TDF represents the trophic discrimination factor. β values depend on whether primary producers in food webs are aquatic or terrestrial (including C3 plants or agricultural C4 plants)19. Studies of terrestrial insects19,24–26; microorganisms27; and mammals, including modern27,28 and fossil29,30 herbivores, carnivores, and ancient humans31,32 suggest that a TDF of 7.6 ± 1.2‰ (1σ) is applicable for terrestrial organisms. However, relative to marine organisms, this tool has been applied to only a limited number of terrestrial taxa and its further use is likely to provide more quantitative and precise estimates of the TP of individuals of other species of ecologically important terrestrial organisms.

We measured δ 13Cbulk and δ 15Nbulk, along with δ 15NAA, from nine bat species with relatively well-characterized and specialized diets and which represent a variety of feeding guilds. We use these data to assess the precision of δ 15NAA-based estimates of TP relative to δ 15Nbulk and estimates of TP inferred from known dietary information.

Materials and Methods

Species and samples

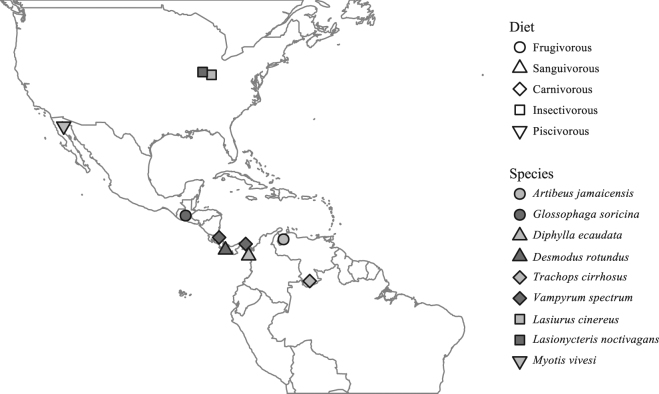

We obtained hair samples from two species of herbivorous bats, two species of sanguivorous bats, two species of insectivorous bats, one species of piscivorous bat, and two species of carnivorous bats in the Americas. All samples were obtained from dry skins of carcasses housed in the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History’s Division of Mammals collection, with the exception of samples from carcasses of the insectivorous species, which were obtained from a wind-energy facility. For each species, all individuals were collected from the same location within North, Central, or South America, with the exception of individuals of Vampyrum spectrum that were obtained from two locations (Fig. 1, Table S1). We collected hair because, unlike other tissues that turnover continuously (e.g. blood), hair is metabolically inert following its growth. Therefore, hair isotopic values should reflect an integrated measure of diet during the period of hair growth33. Bats living in temperate regions are thought to molt during the summer months34–38, although there may be variation in the timing of molt between sexes and among age groups. Furthermore, the timing of annual molt in neotropical bats is poorly understood34.

Figure 1.

Locations where samples were obtained from 9 bat species. Map was generated in the R programming language v3.3.1 (R: A language and environment for statistical computing. v3.3.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria [2016] https://www.r-project.org/)73, using the “maps” package v3.2.0 (http://cran.r-project.org/package=maps)85 and public domain political boundary data published by Natural Earth (http://www.naturalearthdata.com/).

Basic dietary information is known for each species from which we obtained hair. Although the diets of these species are better understood than those of most bat species, such information is not quantitative. Furthermore, understanding of the diets and TPs of many of the organisms that these species of bats prey upon is lacking. Such uncertainties make it challenging to use existing dietary information from the literature to precisely estimate the expected TP of each species. Nevertheless, broad differences in TP are expected, such as that herbivorous bats eat at lower TPs than carnivorous bats.

We obtained hair from the following species:

Jamaican fruit bat (Artibeus jamaicensis), a frugivore that lives in Mexico, Central America, and far northwestern South America that is known to eat fruit and occasionally leaves and flowers14,39,40.

Pallas’s long-tongued bat (Glossophaga soricina), a nectarivore and frugivore found in Central and South America41 that is also known to prey upon insects16,42,43.

Hairy-legged vampire bat (Diphylla ecaudata), a sanguivore occurring in Mexico, Central America, and South America that consumes blood, mostly or entirely of small birds44,45. Blood contains a large proportion of non-metabolized amino acids derived from food amino acids and peptides28,46, and thus D. ecaudata’s TP should be similar to that of its prey rather than being higher than its prey.

Common vampire bat (Desmodus rotundus), a sanguivore with a distribution that includes Mexico, Central America, and South America. Isotopic data suggests this species prefers to ingest blood from cattle47. Like D. ecaudata, we expect the TP of D. rotundus to be similar to that of its prey, but perhaps lower, because D. rotundus feeds exclusively on blood from herbivores whereas D. ecaudata may also feed on organisms at higher trophic levels.

Fringe-lipped bat (Trachops cirrhosus), a carnivore that lives in southern Mexico, Central America, and South America that eats a diversity of prey, including insects, small birds, small mammals (including rodents and small bats), and lizards48,49.

Spectral bat (Vampyrum spectrum), a carnivore from southern Mexico, Central America, and northern South America that eats small birds and mammals48,50.

Hoary bat (Lasiurus cinereus), an insectivore found throughout North, Central, and South America that eats moths and other insects51–55. Prior studies indicate that plant material has occasionally been found in the stomach contents or fecal material of insectivorous bats56, including L. cinereus and L. noctivagans 57–60.

Silver-haired bat (Lasionycteris noctivagans), an insectivore that occurs in North America that eats a variety of prey51,52.

Fish-eating myotis (Myotis vivesi), a piscivore found around the Gulf of California that eats small marine fish (in the Engraulidae, Clupeidae, and Myctophidae families) and surface-swimming crustaceans. It is also thought to occasionally consume terrestrial insects61,62.

Bulk isotope analysis

We obtained hair from 5–13 individuals per species. These samples were cleaned using 1:200 Triton X-100 detergent and 100% ethanol, rinsed 5 times with nano-pure water, and air dried to remove any potential oil or contaminants from the surface of the hair63. Approximately 1 mg of cleaned hair was analyzed for δ 13C and δ 15N using a Carlo Erba NC2500 elemental analyzer (CE Instruments, Milano, Italy) interfaced with a ThermoFinnigan Delta V+ isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS; Bremen, Germany) at the Central Appalachians Stable Isotope Facility (CASIF) at the Appalachian Laboratory (Frostburg, Maryland, USA). The δ 13C and δ 15N data were normalized to the VPDB and AIR scales, respectively, using a two-point normalization curve with laboratory standards calibrated against USGS40 and USGS41. The among-run precision of a keratin standard analyzed multiple times alongside samples was 0.1‰ for δ 13C and δ 15N.

Amino-acid δ15N analysis

The preparation of samples for δ 15NAA analysis is time consuming and costly relative to δ 13Cbulk and δ 15Nbulk analysis. Thus, for δ 15NAA we selected a subset of the individuals that were analyzed for δ 13Cbulk and δ 15Nbulk. We performed δ 15NAA analysis on cleaned hair from five individuals of M. vivesi and three individuals for all other species. We selected individuals spanning a range of δ 15Nbulk values to use for δ 15NAA.

Nitrogen isotope analysis of amino acids was conducted at the Department of Biogeochemistry at the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC; Yokosuka, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan). Samples were prepared as in Chikaraishi et al.18,23. Briefly, ~1 mg of hair from each sample was hydrolyzed, delipified, and derivatized; the derivatives were then extracted. Compound-specific nitrogen isotope analysis was conducted with an Agilent 6890N gas chromatograph coupled to a ThermoFinnigan Delta Plus XP IRMS through GC combustion III interface (Bremen, Germany). Any potential chemicals that hair may have been exposed to (e.g. during preservation as museum specimens) are unlikely to cleave or form bonds associated with the amino-group nitrogen of amino acids and thus are unlikely to affect δ 15NAA (e.g.64). We compared δ 15NAA values from hair cleaned as above vs. rinsed only with water from a subset of individuals, and we observed no effect of the cleaning procedure on the relative abundance of amino acids or δ 15NAA values (data not shown).

Data analysis

The TP of each individual was calculated using equation 1 with the measured δ 15NGlu and δ 15NPhe values, the assigned β values, and the TDF value (7.6 ± 1.2‰, 1σ) recommended for terrestrial organisms19,24–27. Ideally, TDF values are assessed empirically for organisms of interest via controlled-diet studies (e.g.18,65,66). However, such studies are challenging to perform for taxa, such as bats, that are generally difficult to rear in captivity on diets limited to represent a specific TP. Therefore, we used a TDF value of 7.6 ± 1.2‰, which is thought to be applicable for terrestrial food webs (e.g.19,24,26,27,29), for bats with different feeding strategies that have relatively well-characterized and specialized diets.

Values of β differ among aquatic plants, C3 plants, and C4 plants19. Thus, we used δ 13Cbulk and δ 15Nbulk data to identify bats eating on food webs supported by these groups of primary producers (e.g.67–69) and then assign appropriate β values. Individuals with hair δ 13C values > −19‰ and δ 15N values > 12‰, the approximate thresholds for identifying individuals using marine-based food webs67,68, were considered to consume marine prey, and thus were assigned a β value for primary producers in aquatic systems of −3.4 ± 0.9‰ (1σ). Individuals with δ 13C values > −15‰ and δ 15N values < 12‰ were presumed to be eating on C4-plant based terrestrial food webs and thus were assigned a β value of −0.4 ± 1.7‰ (1σ). All other individuals were assigned a β value for terrestrial C3 plants of +8.4 ± 1.6‰ (1σ)70. For species in food webs that include aquatic and terrestrial, or C3 and C4, plants it is possible to use δ 13Cbulk data to calculate a “mixed” β value71, but given the relatively specialized diets of the species we analyzed and the strong observed separation of δ 13Cbulk and δ 15Nbulk values (Fig. 2) we did not use such an approach in this study.

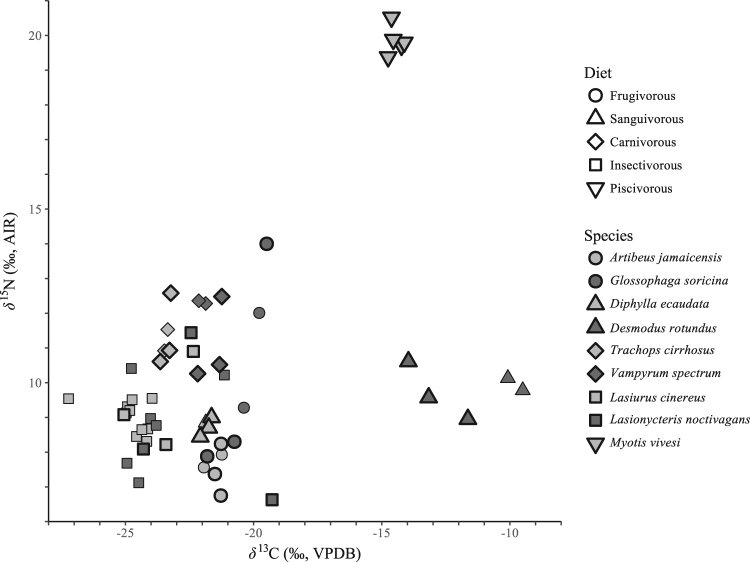

Figure 2.

δ 13C and δ 15N values of bulk hair samples. Samples selected for amino-acid δ 15N analysis are outlined in bold.

The uncertainties in δ 15NGlu and δ 15NPhe values (±0.5‰, 1σ), β values (as above), and TDF (as above), were propagated in equation 1 using the “propagate” package (version 1.0–4) in R (version 3.3.1) to assess uncertainty in calculated TP values72. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) of the calculated TP of each species, as well as δ 15Nbulk for the samples from which δ 15NAA measurements were made, was performed in R73.

Results

Amongst all species, δ 13Cbulk ranges between −27.2 and −9.5‰, and δ 15Nbulk between 6.6 and 20.5‰. Samples from M. vivesi have δ 13Cbulk > −15‰ and δ 15Nbulk > 19‰, and samples from D. rotundus have δ 13Cbulk > −15‰ and δ 15Nbulk < 11‰. Thus, β values of −3.4 ± 0.9‰ and −0.4 ± 1.7‰ are used in calculations of the TP for individuals of these species, respectively. All other individuals have δ 13Cbulk < −19‰ and δ 15Nbulk < 12‰ and thus a β value for terrestrial food webs (+8.4 ± 1.6‰) is used in calculating the TP of the remaining seven species (Fig. 2).

Mean δ 15Nbulk is indistinguishable between A. jamaicensis and D. rotundus, D. ecaudata, L. cinereus and L. noctivagans (Fig. S1). Mean δ 15Nbulk is highest for M. vivesi, followed by T. cirrhosus and V. spectrum. Mean δ 15Nbulk of T. cirrhosus and V. spectrum overlaps with those of D. rotundus and G. soricina.

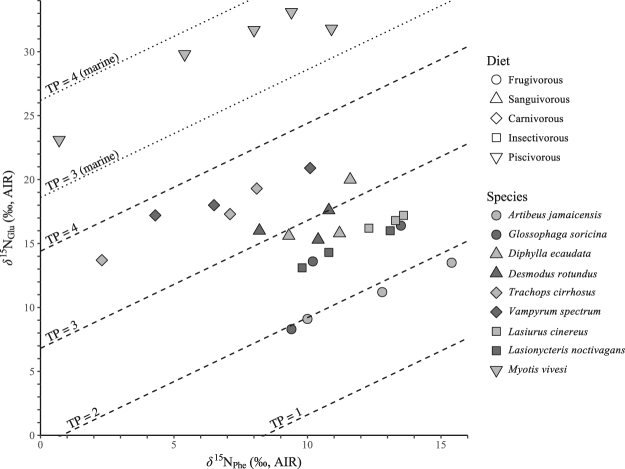

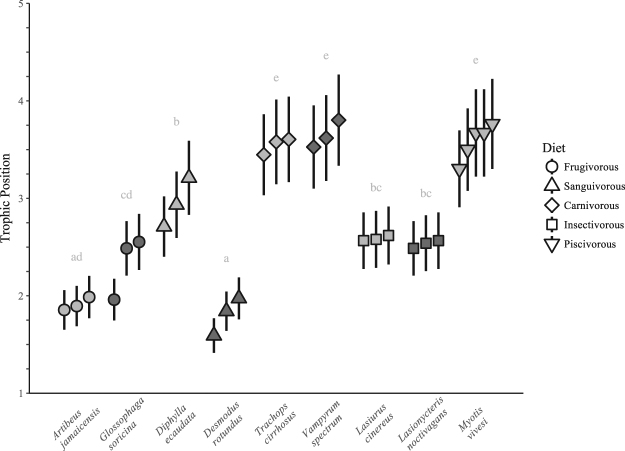

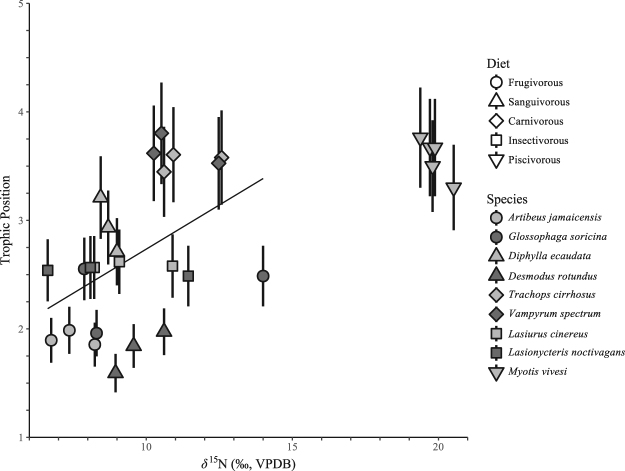

Across all species, δ 15NGlu values range between 33.1 and 8.3‰, and δ15NPhe values range between 15.4 and 0.7‰ (Fig. 3). M. vivesi has the largest range of variation of δ 15NPhe values (0.7–10.9‰). The calculated TP values are highest for individuals of the piscivorous species (M. vivesi, 3.3–3.8) and the carnivorous species (V. spectrum, 3.5–3.8; T. cirrhosus, 3.4–3.8). The calculated TP values are lowest for A. jamaicensis (1.9–2.0) and D. rotundus (1.6–2.0). The calculated TP values of G. soricina (2.0–2.6) are not distinct from A. jamaicensis. The calculated TP values for D. ecaudata (2.7–3.2) are higher than those of the A. jamaicensis, G. soricina, and D. rotundus, but indistinct from those of the insectivorous species, L. cinereus (2.6) and L. noctivagans (2.5–2.6). The calculated TP values for the insectivorous species are higher than those of A. jamaicensis and D. rotundus, but indistinct from G. soricina and D. ecaudata (Fig. 4). There is a positive relationship (r2 = 0.18, p = 0.023, n = 24) between δ 15Nbulk and TP of each individual calculated from δ 15NAA (Fig. 5).

Figure 3.

δ 15N values of glutaminic acid and phenylalanine. Dashed and dotted lines denote trophic position (TP) for terrestrial and marine systems, respectively.

Figure 4.

Trophic position of each individual calculated from amino-acid δ 15N values. Points and error bars denote first-order Taylor expansion mean and one standard deviation, respectively. Letters indicate species-level differences in trophic position determined by Tukey’s test of mean comparison.

Figure 5.

Relationship between bulk δ15N values of hair and trophic position of each individual calculated from amino-acid δ15N values. The regression line (r2 = 0.18, p = 0.023, n = 24) is fit through all of the data, excluding M. vivesi.

Discussion

The broad patterns of variation in bulk-tissue isotopic values reflect the variation expected from known dietary information. For example, M. vivesi had high δ 13Cbulk and δ 15Nbulk values, which is consistent with the facts that M. vivesi is a piscivore and δ 13C and δ 15N values are typically high in aquatic-based food chains67,68. The less negative δ 13C values of D. rotundus supports a prior study suggesting that this species prefers to ingest blood from cattle that, in contrast to native mammals that are part of C3-plant based foodwebs, are typically fed an agricultural C4-plant (i.e. corn) based diet in Central America where our D. rotundus samples originate47. However, beyond assisting with coarse dietary characterization (e.g. marine vs. terrestrial or C3 vs. C4), we are hesitant to use our δ 15Nbulk data to assess the TP of the species we analyzed because the baseline δ 15N values of their foodwebs are unknown. The species with the highest expected and calculated TPs in our dataset (M. vivesi, V. spectrum and T. cirrhosus) had some of the lowest δ 15NPhe values (Figs 3 and 4). Low basal δ 15N values of the foodwebs on which these species ate likely depress their δ 15Nbulk values relative to those otherwise expected for organisms eating at relatively high TPs. Indeed, the δ 15Nbulk values of the carnivorous species were indistinct from those of a frugivore, G. soricina, and a sanguivore, D. rotundus (Figs 2, 5 and S1).

TP values calculated using the δ 15NAA approach are broadly similar to differences in TP expected based on qualitative information about the diets of each species, which helps to validate the δ 15NAA approach for identifying the TP of bats. Strictly herbivorous animals provide perhaps the best opportunity to evaluate the effectiveness of δ 15NAA for identifying TP. In this regard, the calculated TP values for A. jamaicensis (1.9–2.0) are what would be anticipated for a strict frugivore. One individual of G. soricina had a TP of 2.0, but two other individuals of G. soricina had a TP of 2.5–2.6. Such inter-species differences may reflect that A. jamaicensis is thought to be a strict frugivore, whereas G. soricina is thought to also prey upon insects and thus be relatively more omnivorous16,42,43. However, because the timing of molt of these species is not well defined, we cannot exclude the potential that such variation could also indicate differences in TP through time related to hair growth potentially occurring during different time periods among individuals. Furthermore, as expected, TP values were highest for the piscivorous and carnivorous species that are not thought to directly consume primary producers. Calculated TP values were overall lowest for the frugivorous species, as well as one sanguivore, D. rotundus. The mean TP calculated from the δ 15NAA approach for the other sanguivore, D. ecaudata was roughly one TP higher than D. rotundus, likely because D. rotundus feeds exclusively on blood from herbivores, whereas D. ecaudata also feeds on blood of animals at higher trophic levels44,45,47. Such differences in TP between D. rotundus and D. ecaudata were not apparent in δ 15Nbulk (Figs 5 and S1). Together, such results illustrate the effectiveness of δ 15NAA data for determining the TP of bats across diverse dietary groups.

Insectivores should have a TP of ≥3.0. Thus, our finding of a relatively low TP (2.5–2.6) for the analyzed samples of L. noctivagans and L. cinereus was unexpected. One factor by which the TP of these insectivorous bats may have been underestimated is if the TDF value of 7.6 ± 1.2‰ was too large. Although TDF displays minor variation in terrestrial organisms, greater variation in TDF exists in aquatic organisms likely in response to differences in mode of nitrogen excretion and diet quality (the amino acid composition of diet relative to the needs of a consumer)74,75. Mammals excrete urea and thus any influence of mode of nitrogen excretion on the TDF value is likely to affect all bats similarly and is unlikely to explain these results. In aquatic settings, when dietary protein content is low (e.g. for herbivores) TDF is generally high and when protein content is high (e.g. carnivores) TDF values are generally lower74,75. If the TDF value used for L. noctivagans and L. cinereus was too large, perhaps because of a diet potentially high in protein, then TP could be underestimated. However, the TPs calculated from δ 15NAA values for other bat species of higher (and lower) TP appear reasonable, which suggests that it is unlikely that TPs derived from δ 15NAA values would be consistently less than 3.0 for bats that eat insects exclusively. Furthermore, it is unlikely that the calculated TPs of L. noctivagans and L. cinereus were driven lower by undigested plant material that may have been in the alimentary canals of their insect prey, as prior studies based on δ 15NAA data indicate that herbivorous insects consistently have a calculated TP of 2.018,20,24.

Prior studies indicate that small quantities of plant material are occasionally found in the stomach contents or fecal material of insectivorous bats56, including L. noctivagans and L. cinereus 57–60. The exoskeletons of insects are highly resistant and thus more easily digested plant material may be less likely encountered during morphological analysis of gut or fecal material than insect remains (e.g.76). If so, the small quantities of identifiable plant material found in prior studies could suggest that these species are more omnivorous, with greater dietary flexibility to consume plant-based material, than morphological assessments of stomach contents or fecal material suggest.

Although L. noctivagans and L. cinereus had nearly identical TP based on δ 15NAA, δ 15Nbulk of L. noctivagans varied about twice as much as L. cinereus (Figs 2 and 5). The samples from these species were obtained from individuals at the same location and their hair is thought to molt during the summer months33. Therefore, these results may suggest that L. noctivagans has a more general diet and consumes a greater variety of prey (that differ in δ 15N at the base of their food webs) than does L. cinereus, although both species eat at similar TPs. Prior studies suggest that L. noctivagans and L. cinereus hunt a diversity of prey, although other studies consider them to specialize on moths51,52. Although our sample size is small, our results suggest that L. noctivagans may be more of a generalist than L. cinereus. Consistent with this idea, L. cinereus uses narrow-band (long-range) echolocation calls, which might indicate that it is able to be relatively selective about the prey it detects and captures since it detects them from far away. In contrast, L. noctivagans uses broad-band (short-range) echolocation calls that perhaps provide less time for it to decide which prey to pursue and therefore less dietary specialization51. Future studies should further investigate the degree of omnivory and dietary specialization exhibited by these and other species of insectivorous bats.

We observed a particularly wide range of variation (i.e. 0.7–10.9‰) in δ 15NPhe values of M. vivesi. This range suggests differences in the δ 15N values of primary producers at the base of the food webs upon which M. vivesi feeds. Since all samples of this species were obtained on the same day and year it is unlikely that such variation is related to seasonal and/or inter-annual variation in an environmental factor such as climate. Rather, we speculate that such variation may be related to spatial gradients in the extent of denitrification and nitrogen fixation in marine waters of the Gulf of California region (e.g.77,78). Such gradients might allow some of the prey that M. vivesi eats to originate from waters with primary producers with relatively low δ 15N values (e.g. where nitrogen fixation is extensive) and high δ 15N values (e.g. where denitrification is extensive). Alternatively, some of the prey that M. vivesi eats (e.g. Clupeidae) may originate from areas further north in the Pacific Ocean, where δ 15N values are lower, and then transport such low δ 15N values in their biomass to the Gulf of California region.

The error bars in the TP calculated for each individual using the δ 15NAA approach are small, which illustrates the relatively precise estimates of TP for individual organisms that are possible to obtain from δ 15NAA. The positive relationship between δ 15Nbulk and TP calculated from δ 15NAA for the species eating on terrestrial food webs is not unexpected because δ 15Nbulk is partly influenced by TP. However, the predictive capacity of δ 15Nbulk for estimating TP calculated from δ 15NAA is weak. For example, δ 15Nbulk of individuals of L. noctivagans span a range of ~4.8‰, but exhibit variation of only 0.1 in their TP as calculated from δ 15NAA (Fig. 5). Furthermore, δ 15Nbulk values are indistinct among some species with known dietary differences and TPs as inferred from δ 15NAA, such as G. soricina and the carnivorous species (Fig. S1).

Overall, our results indicate that δ 15NAA values are useful for assessing variation in the TP of bats. Therefore, δ 15NAA data will be helpful in addressing ecological and evolutionary questions that have previously been difficult to answer. For example, omnivory is thought to be less common in insectivores than frugivores79,80, and δ 15NAA data may be used to characterize the degree of omnivory in such bat species more precisely than is possible using other approaches. Furthermore, nearly half of all bat species are endangered, threatened, or of conservation concern81. Bats are particularly susceptible to extirpation and extinction because of their low annual reproductive rates82, and bat species of conservation concern are thought to have relatively specialized diets7. Thus, δ 15NAA data could also be used to assess variation in the degree of dietary specialization (measured as shifts in TP) of populations, species, and/or communities and thus identify those at relatively greater risk. Finally, such data could be used to test ecological theory, which predicts dietary specialists to be most prevalent where food availability is stable, whereas generalists are predicted to thrive in environments where resource availability varies (e.g.10,83,84).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

Funding for this study was provided by U.S. National Science Foundation East Asia and Pacific Summer Institute grant OISE 1614267 and by a Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Summer Institute Fellowship (to C.J.C.) and a short-term Invitational Fellowship (ID #S17093) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (to D.M.N.). We thank the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History’s Division of Mammals and Lori Pruitt for providing samples, Robin Paulman for assistance with bulk isotope analysis, Yoko Sasaki for assistance with δ 15NAA analysis, and Hannah Vander Zanden and anonymous reviewers for helpful feedback on earlier versions of the manuscript.

Author Contributions

C.J.C. and D.M.N. conceived and designed the study. C.J.C., N.O.O., Y.C., and N.O. conducted the isotopic analyses. C.J.C. analyzed the data. C.J.C. and D.M.N. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-15440-3.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Boyles JG, Cryan PM, McCracken GF, Kunz TH. Economic importance of bats in agriculture. Science. 2011;332:41–42. doi: 10.1126/science.1201366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kunz TH, et al. Ecosystem services provided by bats. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2011;4:1–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andreas M, Reiter A, Cepáková E, Uhrin M. Body size as an important factor determining trophic niche partitioning in three syntopic rhinolophid bat species. Biologia (Bratisl). 2013;68:170–175. doi: 10.2478/s11756-012-0139-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siemers BM, Greif S, Borissov I, Voigt-Heucke SL, Voigt CC. Divergent trophic levels in two cryptic sibling bat species. Oecologia. 2011;166:69–78. doi: 10.1007/s00442-011-1940-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smirnov DG. Ecology of nutrition and differentiation of the trophic niches of bats. Biol. Bull. 2014;41:60–70. doi: 10.1134/S1062359014010105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arlettaz R, Godat S, Meyer H. Competition for food by expanding pipistrelle bat populations (Pipistrellus pipistrellus) might contribute to the decline of lesser horseshoe bats (Rhinolophus hipposideros) Biol. Conserv. 2000;93:55–60. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3207(99)00112-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyles JG, Storm JJ. The perils of picky eating: Dietary breadth is related to extinction risk in insectivorous bats. PLoS One. 2007;2:e672. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cryan, P. et al. Evidence of late-summer mating readiness and early sexual maturation in migratory tree-roosting bats found dead at wind turbines. PLoS One7 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Kalka MB, Smith AR, Kalko EKV. Bats limit arthropods and herbivory in a tropical forest. Science. 2008;320:71. doi: 10.1126/science.1153352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montoya JM, Pimm SL, Solé RV. Ecological networks and their fragility. Nature. 2006;442:259–264. doi: 10.1038/nature04927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rana JS, Dixon AFG, Jarošík V. Costs and benefits of prey specialization in a generalist insect predator. J. Anim. Ecol. 2002;71:15–22. doi: 10.1046/j.0021-8790.2001.00574.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clare EL, Fraser EE, Braid HE, Fenton MB, Hebert PDN. Species on the menu of a generalist predator, the eastern red bat (Lasiurus borealis): using a molecular approach to detect arthropod prey. Mol. Ecol. 2009;18:2532–2542. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frick WF, Shipley JR, Kelly JF, Heady PA, Kay KM. Seasonal reliance on nectar by an insectivorous bat revealed by stable isotopes. Oecologia. 2014;174:55–65. doi: 10.1007/s00442-013-2771-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herrera Montalvo LG, et al. Sources of assimilated protein in five species of New World bats frugivorous bats. Oecologia. 2002;133:280–287. doi: 10.1007/s00442-002-1036-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.York HA, Billings SA. Stable-isotope analysis of diets of short-tailed fruit bats (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae: Carollia) J. Mammal. 2009;90:1469–1477. doi: 10.1644/08-MAMM-A-382R.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herrera GLM, et al. Sources of protein in two species of phytophagous bats in a seasonal dry forest: Evidence from stable-isotope analysis. J. Mammal. 2001;82:352–361. doi: 10.1644/1545-1542(2001)082<0352:SOPITS>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Post DM. Using stable isotopes to estimate trophic position: Models, methods, and assumptions. Ecology. 2002;83:703–718. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083[0703:USITET]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chikaraishi Y, et al. Determination of aquatic food-web structure based on compound-specific nitrogen isotopic composition of amino acids. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods. 2009;7:740–750. doi: 10.4319/lom.2009.7.740. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chikaraishi Y, et al. High-resolution food webs based on nitrogen isotopic composition of amino acids. Ecol. Evol. 2014;4:2423–2449. doi: 10.1002/ece3.1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McClelland JW, Montoya JP. Trophic relationships and the nitrogen isotopic composition of amino acids in plankton. Ecology. 2013;83:2173–2180. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083[2173:TRATNI]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohkouchi N, Ogawa NO, Chikaraishi Y, Tanaka H, Wada E. Biochemical and physiological bases for the use of carbon and nitrogen isotopes in environmental and ecological studies. Prog. Earth Planet. Sci. 2015;2:1. doi: 10.1186/s40645-015-0032-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohkouchi, N. et al. Advances in the application of amino acid nitrogen isotopic analysis in ecological and biogeochemical studies. Org. Geochem. In Press, 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2017.07.009 (2017).

- 23.Chikaraishi Y, Kashiyama Y, Ogawa NO, Kitazato H, Ohkouchi N. Metabolic control of nitrogen isotope composition of amine acids in macroalgae and gastropods: implications for aquatic food web studies. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2007;342:85–90. doi: 10.3354/meps342085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chikaraishi Y, Ogawa NO, Doi H, Ohkouchi N. 15N/14N ratios of amino acids as a tool for studying terrestrial food webs: a case study of terrestrial insects (bees, wasps, and hornets) Ecol. Res. 2011;26:835–844. doi: 10.1007/s11284-011-0844-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ishikawa NF, Hayashi F, Sasaki Y, Chikaraishi Y, Ohkouchi N. Trophic discrimination factor of nitrogen isotopes within amino acids in the dobsonfly Protohermes grandis (Megaloptera: Corydalidae) larvae in a controlled feeding experiment. Ecol. Evol. 2017;7:1674–1679. doi: 10.1002/ece3.2728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steffan SA, et al. Trophic hierarchies illuminated via amino acid isotopic analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76152. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steffan SA, et al. Microbes are trophic analogs of animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015;112:15119–15124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1508782112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakashita R, et al. Ecological application of compound-specific stable nitrogen isotope analysis of amino acids: A case study of captive and wild bears. Resour. Org. Geochemistry. 2011;27:73–79. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Itahashi Y, et al. Preference for fish in a neolithic hunter-gatherer community of the upper Tigris, elucidated by amino acid δ15N analysis. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2017;82:40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2017.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naito YI, et al. Evidence for herbivorous cave bears (Ursus spelaeus) in Goyet Cave, Belgium: implications for palaeodietary reconstruction of fossil bears using amino acid δ15N approaches. J. Quat. Sci. 2016;31:598–606. doi: 10.1002/jqs.2883. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naito YI, et al. Ecological niche of Neanderthals from Spy Cave revealed by nitrogen isotope analysis of collagen amino acids. J. Hum. Evol. 2016;93:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naito YI, Honch NV, Chikaraishi Y, Ohkouchi N, Yoneda M. Quantitative evaluation of marine protein contribution in ancient diets based on nitrogen isotope ratios of individual amino acids in bone collagen: An investigation at the Kitakogane Jomon site. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2010;143:31–40. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.21287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cryan PMP, Bogan MMA, Rye RO, Landis GGP, Kester CL. Stable hydrogen isotope analysis of bat hair as evidence for seasonal molt and long-distance migration. J. Mammal. 2004;85:995–1001. doi: 10.1644/BRG-202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fraser EE, Longstaffe FJ, Fenton MB. Moulting matters: the importance of understanding moulting cycles in bats when using fur for endogenous marker analysis. Can. J. Zool. Can. Zool. 2013;91:533–544. doi: 10.1139/cjz-2013-0072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Voigt CC. Low turnover rates of carbon isotopes in tissues of two nectar-feeding bat species. J. Exp. Biol. 2003;206:1419–1427. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Constantine DG. Color variation in Tadarida brasiliensis and Myotis velifer. J. Mammal. 1957;38:461–466. doi: 10.2307/1376398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cryan PM, Stricker CA, Wunder MB. Evidence of cryptic individual specialization in an opportunistic insectivorous bat. J. Mammal. 2012;93:381–389. doi: 10.1644/11-MAMM-S-162.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kunz, T. H. Feeding ecology of a temperate insectivorous bat (Myotis velifer). Ecology, 10.2307/1934408 (1974).

- 39.Kunz TH, Diaz CA. Folivory in fruit-eating bats, with new evidence from Artibeus jamaicensis (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae) Biotropica. 1995;27:106–120. doi: 10.2307/2388908. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ortega J, Castro-Arellano I. Artibeus jamaicensis. Mamm. Species. 2001;662:1–9. doi: 10.1644/1545-1410(2001)662<0001:AJ>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alvarez J, Willig MR, Jones JK, Webster WD. Glossophaga soricina. Mamm. Species. 1991;379:1. doi: 10.2307/3504146. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clare EL, et al. Trophic niche flexibility in Glossophaga soricina: how a nectar seeker sneaks an insect snack. Funct. Ecol. 2014;28:632–641. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mirón M. LL, Herrera M. LG, Ramírez P. N, Hobson KA. Effect of diet quality on carbon and nitrogen turnover and isotopic discrimination in blood of a New World nectarivorous bat. J. Exp. Biol. 2006;209:541–548. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greenhall AM, Schmidt U, Joermann G. Diphylla ecaudata. Mamm. Species. 1984;21:1347–1354. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoyt R, Altenbach J. Observations on Diphylla ecaudata in captivity. J. Mammal. 1981;62:215–216. doi: 10.2307/1380503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lorrain A, et al. Nitrogen and carbon isotope values of individual amino acids: a tool to study foraging ecology of penguins in the Southern Ocean. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2009;391:293–306. doi: 10.3354/meps08215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Voigt CC, Kelm DDH. Host preference of the common vampire bat (Desmodus rotundus; Chiroptera) assessed by stable isotopes. J. Mammal. 2006;87:1–6. doi: 10.1644/05-MAMM-F-276R1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bonato V, Gomes Facure K, Uieda W. Food habits of bats of subfamily Vampyrinae in Brazil. J. Mammal. 2004;85:708–713. doi: 10.1644/BWG-121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Whitaker J, Findley J. Foods eaten by some bats from Costa Rica and Panama. J. Mammal. 1980;61:540–544. doi: 10.2307/1379850. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vehrencamp SL, Stiles FG, Bradbury JW. Observations on the foraging behavior and avian prey of the Neotropical carnivorous bat, Vampyrum spectrum. J. Mammal. 1977;58:469–478. doi: 10.2307/1379995. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barclay RMR. Long- versus short-range foraging strategies of hoary (Lasiurus cinereus) and silver-haired (Lasionycteris noctivagans) bats and the consequences for prey selection. Can. J. Zool. 1985;63:2507–2515. doi: 10.1139/z85-371. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Black HL. A North Temperate bat community: Structure and prey populations. J. Mammal. 1974;55:138–157. doi: 10.2307/1379263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reimer JP, Baerwald EF, Barclay RMR. Diet of hoary (Lasiurus cinereus) and silver-haired (Lasionycteris noctivagans) bats while migrating through southwestern Alberta in late summer and autumn. Am. Midl. Nat. 2010;164:230–237. doi: 10.1674/0003-0031-164.2.230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rolseth SL, Koehler CE, Barclay RMR. Differences in the diets of juvenile and adult hoary bats. Lasiurus cinereus. J. Mammal. 1994;75:394–398. doi: 10.2307/1382558. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Valdez EW, Cryan P. Insect prey eaten by hoary bats (Lasiurus cinereus) prior to fatal collisions with wind turbines. West. North Am. Nat. 2013;73:516–524. doi: 10.3398/064.073.0404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thomas HHH, Moosman PPR, Veilleux JPJJP, Holt J. Foods of bats (Family Vespertilionidae) at five locations in New Hampshire and Massachusetts. Can. Field-Naturalist. 2012;126:117–124. doi: 10.22621/cfn.v126i2.1326. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lacki MJ, Johnson JS, Dodd LE, Baker MD. Prey consumption of insectivorous bats in coniferous forests of north-central Idaho. Northwest Sci. 2007;81:199–205. doi: 10.3955/0029-344X-81.3.199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Valdez EW, Cryan PM. Food Habits of the hoary bat (Lasiurus cinereus) during spring migration through New Mexico. Southwest. Nat. 2009;54:195–200. doi: 10.1894/PS-45.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Whitaker JO. Hoary bat apparently hibernating in Indiana. J. Mammal. 1967;48:663. doi: 10.2307/1377600. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Whitaker JO., Jr. Food habits of bats from Indiana. Can. J. Zool. 1972;50:877–883. doi: 10.1139/z72-118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Otalora-Ardila A, Gerardo Herrera LM, Juan Flores-Martinez JJ, Voigt CC. Marine and terrestrial food sources in the diet of the fish-eating myotis (Myotis vivesi) J. Mammal. 2013;94:1102–1110. doi: 10.1644/12-MAMM-A-281.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Blood, B. R. & Clark, M. K. Myotis vivesi. Mamm. Species 1–5 (1998).

- 63.Coplen TB, Qi H. USGS42 and USGS43: Human-hair stable hydrogen and oxygen isotopic reference materials and analytical methods for forensic science and implications for published measurement results. Forensic Sci. Int. 2012;214:135–41. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2011.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ogawa NO, Chikaraishi Y, Ohkouchi N. Trophic position estimates of formalin-fixed samples with nitrogen isotopic compositions of amino acids: An application to gobiid fish (Isaza) in Lake Biwa, Japan. Ecol. Res. 2013;28:697–702. doi: 10.1007/s11284-012-0967-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hebert CE, et al. Amino acid-specific stable nitrogen isotope values in avian tissues: Insights from captive American kestrels and wild herring gulls. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016;50:acs.est.6b04407. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b04407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McMahon KW, Polito MJ, Abel S, Mccarthy MD, Thorrold SR. Carbon and nitrogen isotope fractionation of amino acids in an avian marine predator, the gentoo penguin (Pygoscelis papua) Ecol. Evol. 2015;5:1278–1290. doi: 10.1002/ece3.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Newsome SD, et al. Variation in δ13C and δ15N diet-vibrissae trophic discrimination factors in a wild population of California sea otters. Ecol. Appl. 2010;20:1744–1752. doi: 10.1890/09-1502.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yerkes T, Hobson KA, Wassenaar LI, Macleod R, Coluccy JM. Stable isotopes (δD, δ13C, δ15N) reveal associations among geographic location and condition of Alaskan northern pintails. J. Wildl. Manage. 2008;72:715–725. doi: 10.2193/2007-115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nelson DM, et al. Stable hydrogen isotopes identify leapfrog migration, degree of connectivity, and summer distribution of golden eagles in eastern North America. Condor. 2015;117:1–17. doi: 10.1650/CONDOR-14-209.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chikaraishi, Y. & Ogawa, N. Further evaluation of the trophic level estimation based on nitrogen isotopic composition of amino acids. in Earth, Life, and Isotopes (Kyoto University Press, 2010).

- 71.Choi B, et al. Trophic interaction among organisms in a seagrass meadow ecosystem as revealed by bulk δ13C and amino acid δ15N analyses. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2017;62:1426–1435. doi: 10.1002/lno.10508. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Spiess A. Propagate: Propagation of Uncertainty. R package version. 2014;1:0–4. [Google Scholar]

- 73.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Core Team, doi:3-900051-14-3 (2016).

- 74.McMahon KW, McCarthy MD. Embracing variability in amino acid δ15N fractionation: Mechanisms, implications, and applications for trophic ecology. Ecosphere. 2016;7:e01511. doi: 10.1002/ecs2.1511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McMahon KW, Thorrold SR, Elsdon TS, Mccarthy MD. Trophic discrimination of nitrogen stable isotopes in amino acids varies with diet quality in a marine fish. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2015;60:1076–1087. doi: 10.1002/lno.10081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Herrera M. LG, et al. The role of fruits and insects in the nutrition of frugivorous bats: Evaluating the use of stable isotope models. Biotropica. 2001;33:520. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7429.2001.tb00206.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yamagishi H, et al. Role of nitrification and denitrification on the nitrous oxide cycle in the eastern tropical North Pacific and Gulf of California. J. Geophys. Res. 2007;112:G02015. doi: 10.1029/2006JG000227. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.White AE, et al. Nitrogen fixation in the Gulf of California and the Eastern Tropical North Pacific. Prog. Oceanogr. 2013;109:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2012.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Arkins AM, Winnington AP, Anderson S, Clout MN. Diet and nectarivorous foraging behaviour of the short-tailed bat (Mystacina tuberculata) J. Zool. London. 1999;247:183–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7998.1999.tb00982.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Frick WF, Heady PA, Hayes JP. Facultative nectar-feeding behavior in a gleaning insectivorous bat (Antrozous pallidus) J. Mammal. 2009;90:1157–1164. doi: 10.1644/09-MAMM-A-001.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mickleburgh, S. P., Hutson, A. M. & Racey, P. A. A review of the global conservation status of bats. Oryx36 (2002).

- 82.Barclay, R. M. & Harder, L. D. Life histories of bats: life in the slow lane. In Bat Ecology 209–253 (2003).

- 83.Futuyma DJ, Moreno G. The evolution of ecological specialization. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 1988;19:207–233. doi: 10.1146/annurev.es.19.110188.001231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Maine JJ, Boyles JG. Bats initiate vital agroecological interactions in corn. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015;112:12438–12443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505413112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Becker, R. A., Wilks, A. R., Brownrigg, R. & Minka, T. P. maps: Draw geographical maps. R package version 3.2.1 (2016).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.