Abstract

Aphid saliva plays important roles in aphid-host interactions, such as assisting aphid digestion, detoxification, activating or suppressing plant defenses. The grain aphid, Sitobion avenae, is one of the most devastating pests of cereals worldwide. In this study, we performed the transcriptome analysis of salivary glands of S. avenae. A total of 33,079 assembled unigenes were identified in the salivary glands of aphids. Of the all obtained unigenes, 15,833(47.86%) and 10,829(32.73%) unigenes showed high similarity to known proteins in Nr and Swiss-Prot databases respectively. 526 unigenes were predicted to encode secretory proteins, including some digestive and detoxifying enzymes and potential effectors. The RT-PCR and RT-qPCR results showed that all of the 15 most highly expressed putative secretory proteins specifically expressed in salivary glands. Interestingly, 11 of the 15 most highly expressed putative secretory proteins were still not matched to function-known proteins. We also detected the expression of 9 interested putative secretory proteins in aphid different tissues, including some digestive and detoxifying enzymes, effectors and Ca2+ binding proteins. The results showed that only glutathione-S-transferase 1 was specifically expressed in salivary glands. These findings provide a further insight into the identification of potential effectors involving in aphid-cereals interactions.

Introduction

The salivary components of insects are thought to play crucial roles during interactions with host plants. During feeding, insects secrete saliva with wide composition into host plants for ingesting nutrients and degrading toxins1,2. Saliva also contains some proteins and small molecules that have been discovered to activate or suppress plant defense responses3–6.

Unlike leaf chewing insects such as lepidopterans, aphids (Hemiptera: Aphidoidea) have highly modified piercing-sucking mouthparts (stylets) that can penetrate between plant cells to feed phloem sap from sieve elements7. During probing and feeding, aphids secrete two types of saliva: gelling saliva, which solidifies into a tube-like sheath to protect the stylet from mechanical damage and chemical attack, and watery saliva, which is secreted into plant cells, intercellular spaces and phloem8–10. The feeding process of aphids is similar to the infection process of plant pathogens, with an interplay between aphid and host plants that follows the plant–pathogen model proposed by Jones and Dangl11,12. Pathogens deliver effectors into the host to modulate plant immunity using a specific secretion system13,14. Aphids are also thought to secrete some salivary proteins as effectors into their host plants to alter cell metabolic processes and modulate plant defense responses15,16.

Recently, a number of studies have focused on the function of salivary proteins during aphid–host interactions. Salivary proteins between 3 and 10 kD of the green peach aphid, Myzus persicae, can elicit plant defense responses in Arabidopsis thaliana 17. Salivary secretions by aphids can also prevent phloem from clogging as a result of a plant wound response to enable phloem feeding to continue18. The essential roles of salivary protein C002 in the successful feeding of the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphone pisum, on fava bean have been demonstrated using RNA interference19. Overexpression of M.persicae effector MpC002, potato aphid Macrosiphum euphorbiae effectors Me10 and Me23 in Nicotiana benthamiana increased aphid fecundity, suggesting their ability to suppress plant defenses, however, in planta expression of Mp10 and Mp42 reduced aphid fecundity and Mp10 induced obvious chlorosis response in N. benthamiana, suggested these effectors involved in the activation of plant defense response20–22.

For investigating the roles of saliva in aphid–plant interactions, the composition of aphid salivary proteins first needs to be identified. Actually, the transcriptome of salivary glands has been analyzed in some hemipteran species such as potato leafhopper Empoasca fabae 23, whitefly Bemisia tabaci 24, rice brown planthopper Nilaparvata lugens 25, green rice leafhopper Nephotettix cincticeps 26, tarnished plant bug Lygus lineolaris 27. Some salivary proteins with enzymatic activities were also identified in the watery saliva of M. persicae using mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS); e.g., glucose oxidase, first identified in the chewing insect Helicoverpa zea, was demonstrated to be an effector that suppresses plant defense4,28. In a dual transcriptomic-proteomic approach, over 300 secretory salivary proteins from the salivary glands of A. pisum were identified29.

The grain aphid, Sitobion avenae, is an important agricultural pest of cereals causing serious economic losses through nutrient robbing and transmitting plant viruses (BYDV)30,31. In research to elucidate the composition and function of S. avenae saliva, pectinase was detected, and exogenous application of pectinase induced volatile emissions in wheat and attracted the aphid parasitoid Aphidius avenae 32. Ma et al. found polyphenol oxidase (PPO) in S. avenae saliva, and wheat seedlings treated with PPO had increased expression of genes related to plant defense signaling33. Recently, the composition of watery salivary proteins of S. avenae was studied by tandem mass spectrometry, and 12 proteins were identified34.

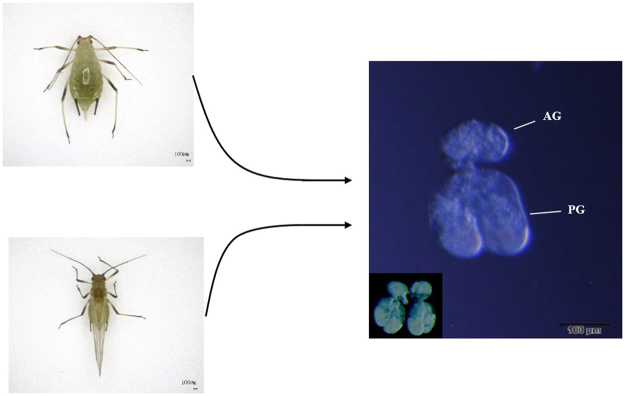

Aphid salivary secretory proteins were usually collected from artificial diet for further identification by proteomics, some proteins with low concentrations or only induced during interacted with host plants may not be detected. Aphid salivary glands are paired and composed of two primary glands and two accessory glands, secreted salivary proteins are mainly synthesized in the primary glands35. Although the function of the accessory glands has not been well studied, they might be involved in the transmission of viruses such as BYDV in S. avenae 36. Therefore, in this study, we directly dissected whole salivary glands from aphids (Fig. 1) and sequenced the transcriptome of the salivary glands of S. avenae. Of 33,079 unigenes identified in the whole salivary glands, 526 unigenes were predicted to encode secretory proteins, and some of their orthologs have been proved to play important roles in aphid-host interactions. These findings firstly provide insight into the identification of potential effector molecules in S. avenae saliva and further our understanding of the roles of saliva in aphid–wheat interactions.

Figure 1.

Paired salivary glands of Sitobion avenae, consisting of two principal glands (PG) and accessory salivary glands (AG). Photos of S. avenae were imaged by digital microscope VHX-2000C (KEYENCE, OSA, Japan) and salivary gland was scanned with stereomicroscope Olympus SZX16 (Olympus, TYO, Japan).

Results and Discussions

Illumina sequencing and unigene assembly

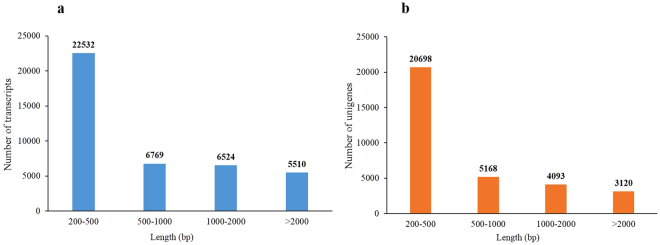

In total, 58,224,912 bp and 50,854,016 bp raw reads were acquired from salivary glands of apterous and alate S. avenae adult, respectively. After removing adapters, ambiguous nucleotides and low quality sequences, 56,280,842 bp and 49,104,484 bp cleans reads remained. Subsequently, the transcriptome of S. avenae salivary glands was de novo assembled using the short reads assembling program-Trinity37, which were then clustered into 41,335 transcripts and 33,079 unigenes (Table 1). These transcripts ranged from 201 to over 14,923 bp with an average size of 941 bp. Among the transcripts, 22,532 (54.51%) were between 200 bp and 500 bp long, and 5,510 (13.33%) were over 2,000 bp. Also, among the assembled unigenes, 20,698 (62.57%) unigenes were between 200 bp and 500 bp long, and 3,120 (9.43%) were over 2,000 bp; mean length of unigenes was 711 bp (Fig. 2). All sequences of the unigenes in this study are provided in (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1.

The quality of S. avenae salivary glands unigene sequences and assembly.

| Statistic | apterous adult | alate adult |

|---|---|---|

| Raw reads (bp) | 58,224,912 | 50,854,016 |

| Clean reads (bp) | 56,280,842 | 49,104,484 |

| Clean base pairs (Gb) | 8.44 | 7.37 |

| Error (%) | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Q20 (%) | 96.79 | 96.68 |

| Q30 (%) | 91.98 | 91.75 |

| GC (%) | 38.48 | 38.58 |

| Unigenes | 33,079 | |

Figure 2.

Length distribution of transcripts (a) and unigenes (b) in transcriptome assembly for S. avenae salivary glands.

Functional annotation of transcripts

For functional annotation, sequence similarity searches of 33,079 unigenes were run against Nr, Nt, KEGG, Swiss-Prot, PFAM, GO and KOG databases. The results showed that 15,833 (47.86%), 18,624 (56.3%), 6,772 (20.47%), 10,829 (32.73%), 10,602 (32.05%), 10,776 (32.57%) and 7,956 (24.05%) unigenes matched to known proteins in the Nr, Nt, KEGG, SwissProt, PFAM, GO and KOG databases, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Number of unigenes annotated in seven public databases.

| Database | Number of unigenes | Percentage of unigenes (%) |

|---|---|---|

| NR | 15833 | 47.86 |

| NT | 18624 | 56.3 |

| KO | 6772 | 20.47 |

| Swiss-Prot | 10829 | 32.73 |

| PFAM | 10602 | 32.05 |

| GO | 10776 | 32.57 |

| KOG | 7956 | 24.05 |

| All databases | 4663 | 14.09 |

| At least one database | 20783 | 62.82 |

| Total unigenes | 33079 | 100 |

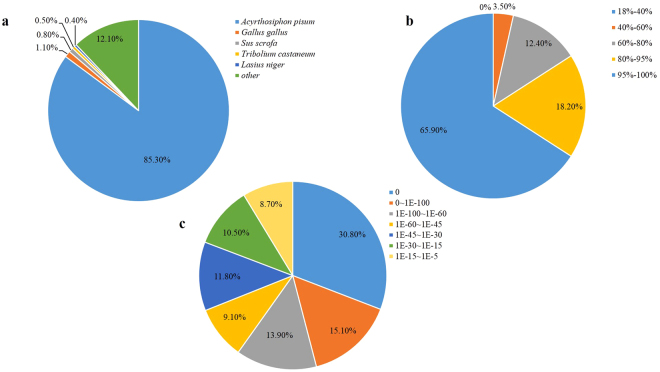

The highest percentage of blast hits came from A. pisum (85.3%). The species distribution of unigenes that have significant BLASTn hits against the NCBI nr protein database are shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

Results of similarity search of unigenes against Nr database. (a) Species distribution of the top BLAST hits for each unigene in Nr database. (b) Similarity distribution of the top BLAST hits for each unigene. (c) E-value distribution of BLAST hits for each unigene with a E-value cut off of 1.0E−5.

Gene Ontology (GO) and Eukaryotic Othologous Groups classification (KOG)

The unigenes from S. avenae salivary glands were annotated for function using Gene Ontology (GO)38. Of the 33,079 assembled unigenes, 10,776 were assigned into 55 different functional groups. The three most abundantly represented categories in “biological process” were “cellular process”, “metabolic process” and “single-organism process” with 5,865 (54.43%), 5,232 (48.55%) and 4,415(40.97%) unigenes, respectively. In “cellular components” ontology, “cell” with 3,403 (31.58%) and “cell parts” with 3,403 (31.58%) unigenes were the two most common categories. In addition, in the “molecular function” group, unigenes were mainly distributed in two categories: “binding” with 6,108 (56.68%) unigenes and “catalytic activity” with 4,171 (38.70%) unigenes (Supplementary Figure 1).

EuKaryotic Orthologous Groups (KOG) is a version of the Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) for identifying orthologous and paralogous proteins in eukaryotic organisms39. In total, 7,956 unigenes were categorized into 26 groups, among these categories, the cluster of “General function prediction only” group had the most unigenes (1,425, 17.89%) followed by “Signal transduction mechanisms” (1,186, 14.91%), “Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones” (836, 10.51%), “Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis” (669, 8.41%), and “Transcription” (471, 5.92%) (Supplementary Figure 1).

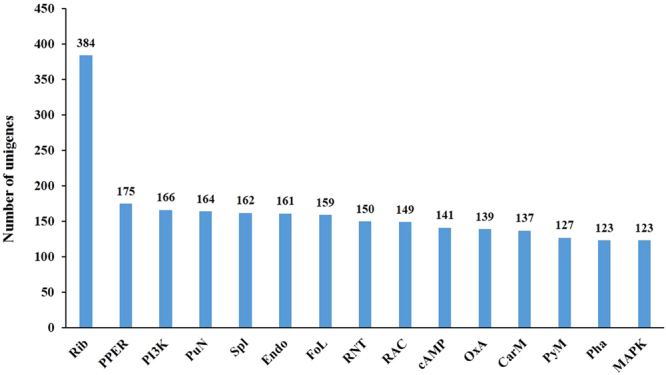

Metabolic pathway analysis by Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)

When the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway was used to describe the network of molecular interactions and metabolic pathways in cells40, 6,772 unigenes in the salivary glands of S. avenea were mapped to a total of 229 KEGG pathways. Among these pathways, “Ribosome” (384 unigenes), “Protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum” (175 unigenes), and “PI3K-Akt signaling pathway” (166 unigenes) had the most unigenes (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

The top15 KEGG pathways with highest numbers of unigenes in salivary glands of S. avenae. Abbreviation for pathways: ribosome(Rib), protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum (PPER), PI3K-Akt signaling pathway (PI3K), purine metabolism (PuN), spliceosome (Spl), endocytosis (Endo), focal adhesion (FoL), RNA transport (RNT), regulation of actin cytoskeleton (RAC), cAMP signaling pathway (cAMP), oxidative phosphorylation (OxA), carbon metabolism (CarM), pyrimidine metabolism (PyM), phagosome (Pha), mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway(MAPK).

In the KO and KEGG annotations, the unigenes in the second hierarchy of the KEGG pathway were assigned to 5 categories, including “Cellular Processes”, “Environmental Information Processing”, “Genetic Information Processing”, “Metabolism” and “Organismal Systems” (Supplementary Figure 2). In the “Cellular Processes” category, “Transport and catabolism” and “Cellular community” were the two most common pathways with 463 (6.84%) and 344 (5.08%) unigenes, respectively. In the “Environmental Information Processing” category, “Signal transduction” included the most unigenes (935, 13.81%). In “Genetic Information Processing”, “Translation” and “Folding, sorting and degradation” were the top two pathways with 713 (10.53%) and 434 (6.41%) unigenes, respectively. In the “Metabolism” group, “Carbohydrate metabolism”, “Lipid metabolism” and “Amino acid metabolism” were the three most abundantly represented pathways with 346 (5.11%), 293 (4.33%) and 249 (3.68%) unigenes, respectively. In “Organismal Systems”, the unigenes were mainly assigned to “Endocrine system” (501, 7.40%), “Immune system” (355, 5.24%) and “Digestive system” (309, 4.56%). The KEGG pathway distributions were consistent with the characterization and potential function of aphid salivary proteins.

Putative secretory proteins

Salivary proteins are proposed to be involved in interactions with plant, only when they can be secreted into plant during aphid probing and feeding. Therefore, all unigenes were analyzed for the presence of signal peptide and potential cleavage site using SignaIP software in this study. In total, 526 putative secretory proteins were obtained from all unigenes, however, some putative secretory proteins might have been missed as a result of partial ORF sequences, such as 3′ partial, 5′ partial and internal partial sequences. Of all putative secretory proteins, 335 (63.69%) proteins were functionally annotated and 191(36.31%) showed no similarities with known-function proteins in the Nr database. And, some function-annotated putative secretory proteins are very closely related to several insect salivary proteins that have been proved to play important roles in insect–host interactions, such as digestive and detoxifying enzymes and effectors (Supplementary Table 2).

Digestive and detoxifying enzymes

During phloem feeding, aphids secrete salivary proteins with digestive enzyme activity that facilitate probing and feeding. The transcript of a cell wall degradation enzyme, beta-mannosidase (c15158_g1) was found in our study. Beta-mannosidase catalyzes the endo-wise hydrolysis of the backbone of mannan and heteromannans, including a major component of plant cell walls, hemicellulose polysaccharides41. This enzyme can help aphids penetrate the plant cells. Sugar-degrading enzymes and proteases such as maltase, beta-glucuronidase, serine protease, trypsin and cathepsin were also identified in the salivary glands of S. avenae in our study. Wheat phloem sap is high in sucrose and some amino acids, predominantly glutamic acid, aspartic acid and serine42. The presence of these secretory digestive enzymes from S. avenae could thus aid extra-orally digestion, consistent with the feeding style of S. avenae.

When plants are attacked by herbivorous insects, plant hormones including jasmonic acid (JA), salicylic acid (SA), ethylene (ET), abscisic acid (ABA), and gibberellic acid (GA), known to modulate defense responses, are induced43. Plants also produce toxic secondary metabolites and defensive proteins, such as 2,4-dihydroxy-7-methoxy-2H-1,4-benzoxazin-3(4 H)-one (DIMBOA), lectins, glucosinolates, protease inhibitors to limit herbivory44–47. However, insects possess many enzymes to degrade toxins and facilitate host adaptation to adverse conditions. Cytochrome oxidases, glutathione S-transferases and esterase have been suggested as important enzymes for resistance to plant secondary metabolites and insecticides in aphids and other insects48,49. We identified the transcripts of cytochrome oxidase (c1987_g1), glutathione S-transferase 1 (c14396_g2), esterase FE4 (c7566_g1) and esterase E4 (c12530_g1) in the salivary glands of S. avenae. Previously, transcripts of cytochrome P450 oxidases and GSTs were found in the salivary gland of E. fabae 23, N. lugens 25, N. cincticeps 26, A. pisum 29 and protein cytochrome P450 oxidases and GST were also detected from saliva of Russian wheat aphid Diuraphis noxia 50, vetch aphid Megoura viciae 51 and M. euphorbiae 52. We also found metalloproteases (c14542_g1, c26916_g1) in S. avenae, a kind of peptidases, which were also identified in the saliva of A. pisum, M. viciae and M. persicae before51. Although the function of metalloproteases in aphid–plant interactions is still unclear, they are predicted to be involved in detoxifying plant defense proteins.

Peroxidase (c28134_g1, c13443_g1, c12708_g1, c14634_g2, c14243_g1, c14995_g1), an oxidoreductase was detected here, and was reported previously in salivary glands of Hession fly Mayetiola destructor 53, A. pisum 29 and M. viciae 51. Reactive oxygen species (ROS), including singlet oxygen, superoxide and hydrogen peroxide are involved in signaling pathways to activate plant defense responses and resistance to aphid. For example, accumulation of hydrogen peroxide at aphid feeding sites indicated reactive oxygen species are involved in early signaling of A. thaliana after infestation by the cabbage aphid Brevicoryne brassicae 54. High levels of H2O2 accumulated in a resistant near-isogenic wheat line but not in a susceptible line after infestation by the D. noxia 55. A sudden rise in oxygen concentration in sieve elements might result in protein coagulation in cucurbit phloem sap56. Additionally, high H2O2 levels in plants could be toxic to aphids. Peroxidase, acting as antioxidant enzymes involved in H2O2 scavenge, suggest that peroxidase detected in aphid salivary glands may protect aphids from plants oxidative stress as a detoxifying enzymes and play important roles in suppressing ROS production and ROS-induced plant defense responses.

Effectors eliciting or suppressing plant defenses

We found beta-glucosidase (c10709_g1) in the salivary glands of S. avenae. Beta-glucosidase, mainly regarded as a digestive enzyme for molecules such as hemicellulose, was also detected in the salivary glands of the termite Neotermes koshunensis57. However, it might also be an effector to activate plant defense responses. Lima bean Phaseolus lunatus treated with a solution of beta-glucosidase emitted more volatile compounds, which were similar to those emitted in response to red spotted spider mite Tetranychus urticae infestation58. Leaves treated with commercial beta-glucosidase released volatile blends similar to that of leaves infested with cabbage white butterfly Pieris brassicae 59. Also, the levels of plant defense signaling molecules salicylic acid, ethylene, and H2O2 in rice increased after the application of beta-glucosidase, and the defense signaling pathways induced by beta-glucosidase were similar to those activated by infestation with N. lugens 60.

Lipases (c11727_g1, c8374_g1) and some phospholipases (c13818_g1, c7165_g1) were detected in the transcriptome of S. avenae salivary glands in this study. Lipases also have been found in the salivary glands of some insects, including mosquito Anopheles stephensi 61, M. destructor 62, large milkweed bug Oncopeltus fasciatus 63 and E. fabae 23. The primary function of lipases is presumed to be the breakdown membrane lipids and thereby the membrane; thus, they were first predicted to act as digestive enzymes to facilitate penetration of the cell membrane. However, Schäfer et al. showed that lipases in grasshopper oral secretions induced accumulation of cyclopentenone 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid (OPDA), a precursor of JA biosynthesis in A. thaliana, and external application of lipase solution to wounded leaves also highly increased the levels of 13-hydroperoxy octadecatrienoic acid, OPDA, JA, and jasmonic acid-isoleucine, suggesting that lipases elicited plant defense responses64. Phospholipases hydrolyze phospholipids, which take part in lipid synthesis, lipid-derived signaling pathway and plant stress responses. It is assumed that phospholipases D (PLD) and its products, phosphatidic acid, are involved in plant signal transduction cascades and the lipid metabolic pathway to influence plant stress responses. Gene expression and enzyme activity of PLD increased rapidly after exposure to various stresses, such as mechanical wounding, frost and pathogen infestation65–67. Increases in the PLD transcripts and accumulation of PLD along the plasma membrane were observed after rice leaves were infected with the bacterial pathogen Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae 68. Also, PLD participates in the production of plant defense response signaling molecules (ABA, ET, NADPH oxidase)66. Thus, lipases in S. avenae or lipase-derived molecules are likely to serve as effectors to induce downstream plant defense responses.

Salivary glucose oxidase (GOX) was the first effector identified in the saliva of herbivores to suppress plant defense. The caterpillar H. zea secretes GOX into its host Nicotiana tabacum to suppress nicotine production and the jasmonic acid defense signaling pathway4. GOX was found in the saliva of many other caterpillar species and in the aphid M. persicae 28, but not in other aphid species. We identified another highly expressed glucose-methanol-choline oxidoreductase, glucose dehydrogenase (GLD, c10172_g2, c10815_g1, c12301_g1), in the salivary glands of S. avenae. GLD is also found in the saliva and salivary glands of other aphid species29,34,50,51. We predicted that GLD functioned in a similar way to GOX and as a potential effector to suppress plant defense responses after aphid infestation.

C002 is an aphid-specific watery saliva protein and also a well-known effector protein related to aphid feeding behavior and subsequent survival and fecundity69–71. Knockdown of C002 transcript of A. pisum and S. graminum resulted in high mortality of aphids19,69,71. The reproduction rate of M. persicae increased after feeding on host plants that over-express MpC002 but decreased after feeding on plants producing double-strand RNA (dsRNA) against C00220,70. At the proteomic level, C002 protein has been identified in M. persicae and A. pisum saliva19,28,72. However, its underlying mechanism is still unknown. An ortholog of C002 (c12732_g1) was also found in the salivary glands of S. avenae in this study with very high abundance in the transcriptome (RPKM = 10,926.33).

Angiotensin converting enzyme-1 (ACE-1, c10308_g1) was found in the salivary glands of S. avenae in the present study. ACE is a zinc-metallopeptidase found on the endothelial, epithelial and neuronal tissues in mammals73. The function of ACEs were studied in various insects such as locust Locusta migratoria 74, cotton leafworm Spodoptera littoralis 75 and buffalo fly Haematobia irritans exigua 76. Three ACE genes, ACE1, ACE2 and ACE3, were identified in the genome of A. pisum 77, and the ACE proteins were also detected in the saliva of A. pisum 29,72. ACE1 and ACE2 are highly expressed in the salivary glands, and compared with aphid survival rate on artificial diets, the survival rate of aphids with simultaneous knockdown of ACE1 and ACE2 decreased significantly after aphids fed on plants. These results indicated that ACE1 and ACE2 can function as effectors to modulate plant physiological processes to benefit aphid infestation77.

Trehalose, a kind of glucosidase in many organisms ranging from bacteria, fungi to plants78. Although the level of trehalose is very low in plants, many studies have demonstrated that it plays a regulatory role in sugar metabolism, growth, development and stress responses of plants79. Overexpressing trehalose biosynthetic genes of microbial and plant origin or receive exogenous trehalose, stress tolerance increased in several plants, such as tobacco, potato and rice80,81. We identified trehalase (c11521_g1, c13987_g1, c14644_g1), which degrades trehalose, in the salivary glands of S. avenae, and it has also been found in salivary glands of B. tabaci and the saliva of M. dirhodum and S. avenae 24,34. Trehalase activity in A.thaliana increased before trehalose accumulated when infested with the trehalose-producing pathogen Plasmodiophora brassicae, suggesting that trehalase may be a part of the plant defense responses and prevent excess accumulation of trehalose in plant cells82. Aphid-secreted trehalase may also play a role in interrupting trehalose accumulation to repress plant defense responses. However, a study showed that exogenous trehalose suppressed the transcript levels of some genes encoding enzymes related to plant defense, wound response, or pathogenesis, such as peroxidase-2 (PRXR2), basic endochitinase (ChiB), endo-1,3-b-d-glucanase (BGL1), lipoxygenase-2 (LOX2), and a chitinase-like protein 1 (CTL1)83. The role of trehalase in plant defense response needs further study.

Among the putative secretory proteins, we found odorant binding proteins (OBPs, c5921_g1, c2376_g1) and chemosensory proteins (CSPs, c5314_g1, c8576_g1, c18419_g1, c2724_g1). Transcripts of OBPs and CSPs have also been found in salivary glands of N. lugens, M.persicae, M.cerasi and bird cherry-oat aphid Rhopalosiphum padi 25,84. Insect OBPs and CSPs involved in olfaction and gustation are thought to be crucial for insect behaviors such as locating food and ovipository sites, as well as intraspecific communication85, and are mainly specifically expressed in chemosensory organs such as antennae and mouthparts and predicted to function in chemoperception86–88. However, some insect OBPs and CSPs are found in other tissues such as legs, heads, bodies and salivary glands86 with functions in insect development89, leg regeneration90, immune responses, and even interactions with the host. For example, Dengue virus (DENV) infection increased transcripts expression of OBP10 and OBP22 in the salivary glands of Aedes aegypti and silencing of the OBP10 or OBP22 genes resulted in a low efficiency of mosquito blood-feeding91. OBPs were found in the salivary glands of Anopheles gambiae and predicted to be secreted into host cells to manipulate host physiology by scavenging host amines92. Also, CSPs were identified using mass spectrometry as the most abundant proteins in the mandibular glands of larvae of the butterfly Vanessa gonerilla and speculated to play important roles in detecting microorganisms on plant surfaces, recognizing host plants and communicating with conspecifics93. CSP4 in cotton bollworm Helicoverpa armigera and oriental tobacco budworm Helicoverpa assulta possess unique functions that act as surfactants to reduce water surface tension and, consequently, pressure during sucking94, suggesting CSPs are involved in insect feeding. Among the CSPs identified in S. avenae, unigene c18419_g1 had high similarity to Mp10 known to be an effector in M. persicae. Mp10, a chemosensory protein was detected in the heads, salivary glands and whole bodies of M. persicae. Functional assays showed that overexpression of Mp10 in N. benthamiana suppressed bacterial pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) flg22-induced defense responses, but induced chlorosis and local cell death in N. benthamiana, resulting in a decrease of M. persicae fecundity20,22. Thus, OBPs and CSPs secreted by salivary glands of S. avenae may play important roles in aphid-host interactions and warrant further functional study.

Among potential effectors that were detected, such as lipid-binding proteins apolipophorins (c26673_g1)51, we also identified transcript sequence c10120_g1 as an ortholog of potato aphid M. euphorbiae effector Me10. Overexpression of Me10 in the host plant N. benthamiana increased M. persicae fecundity, suggesting its ability to suppress plant defenses21,52. As we mentioned before, some putative secretory proteins with effector activity may be missed because of partial sequences. For example, the unigene c9478_g1 (5′ primer partial) is a likely homolog of a potential salivary effector Mp55 of M. persicae, A. thaliana expressing Mp55 increased aphid reproduction, and accumulated less 4-methoxyindol-3-ylmethylglucosinolate, callose and hydrogen peroxide in response to aphid infestation, suggesting a role of Mp55 in suppressing plant defenses95.

Calcium ion () binding proteins

We identified some potential Ca2+ binding proteins in the putative secretory proteins of S. avenae salivary glands, including regucalcin (c11006_g1), reticulocalbin-2 (c8802_g1) and calumenin (c10782_g1).

Calcium ions (Ca2+) constitute a ubiquitous intracellular second messenger in many plant signaling pathways including induction of defense responses96,97. Mechanical damage of phloem tubes can trigger the sieve plate occlusion to avoid the outflow of phloem sap because of the releasing of Ca2+ into the sieve element lumen98. But damage caused by aphid stylets penetration don’t lead to the phloem sieve cell plugging18. Will T. firstly reported that M. viciae saliva contained some Ca2+ binding proteins prevent Ca2+-dependent sieve occlusion in Vicia faba through inducing dispersed forisomes, a Ca2+-driven contractile protein that can cause reversible plugs in sieve element, to return to the non-plugging state, and secretion of watery saliva also seems to be a universal way for aphids to suppress sieve-plate occlusion99,100. Some Ca2+ binding proteins were also found in salivary glands and saliva of hemipterans using transcriptomic and proteomic technologies, such as regucalcin in A. pisum and N. cincticeps 26,72, the most highly expressed salivary glands gene calcium-binding protein SP84(NcSP84) in N. cincticeps 26. These indicated that Ca2+ binding proteins secretion to suppress plant defense may be a common strategy amongst phloem-feeding insects.

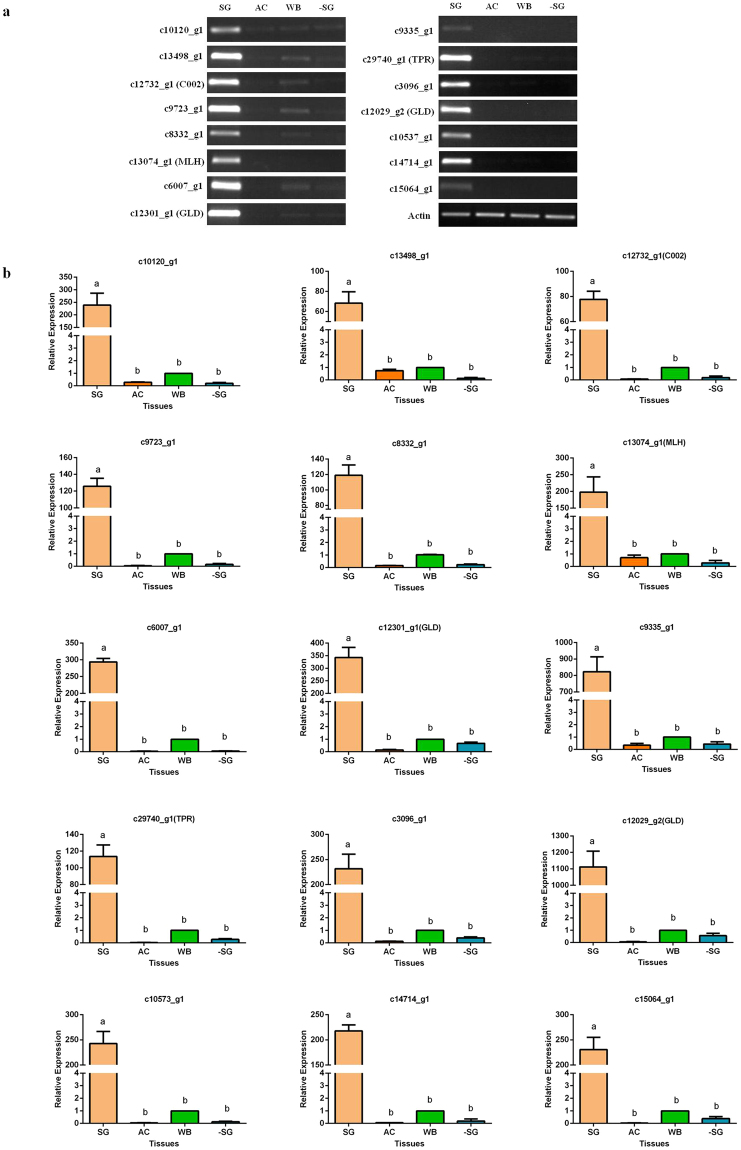

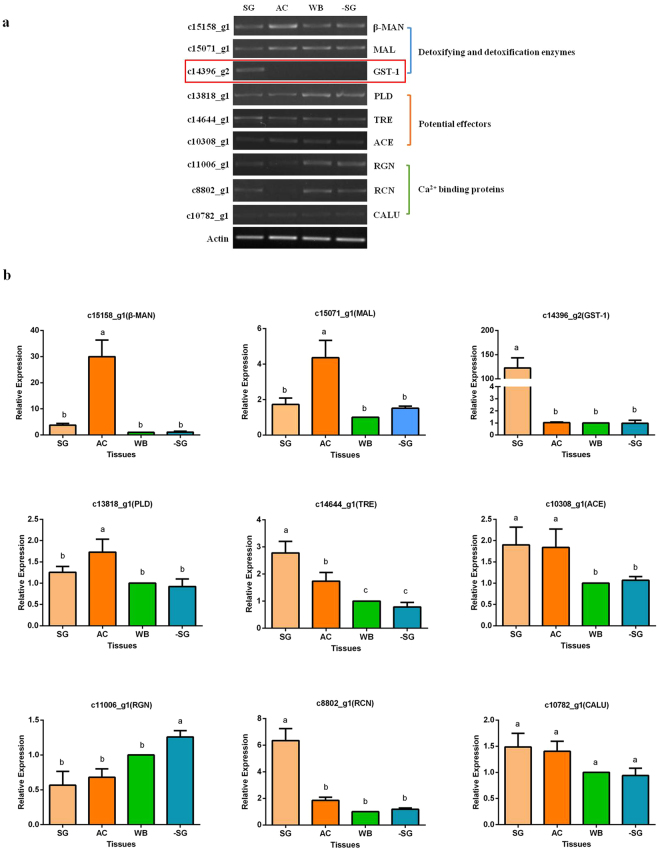

RT-PCR and RT- qPCR analysis of gene expression in different aphid tissues

The expression of the top 15 most highly expressed and some of interesting unigenes in salivary glands, alimentary canal, whole body minus salivary glands of apterous aphids were detected using RT-PCR and RT-qPCR. The 15 highly expressed transcripts, c10120_g1, c13498_g1, c12732_g1 (C002), c9723_g1, c8332_g1, c13074_g1 (micronuclear linker histone polyprotein-like , MLH), c6007_g1, c12301_g1 (glucose dehydrogenase, GLD), c9335_g1, c29740_g1 (tetratricopeptide repeat protein 21B, TPR), c3096_g1, c12029_g2 (glucose dehydrogenase, GLD), c10537_g1, c14714_g1, c15064_g1 and 9 interesting transcripts, c15158_g1 (beta-mannosidase, β-MAN), c15071_g1 (maltase A1, MAL), c14396_g2 (glutathione-S-transferase 1, GST-1), c13818_g1 (phospholipase D, PLD), c14644_g1 (trehalase, TRE), c10308_g1 (angiotensin converting enzyme, ACE) c11006_g1 (regucalcin, RGN), c8802_g1 (reticulocalbin-2, RCN), c10782_g1 (calumenin, CALU), are shown in (Supplementary Table 3).

Interestingly, only 4 transcripts were annotated in top 15 highly expressed unigenes, with most still categorized as function unknown. Among these 4 annotated unigenes, GLD (c12301_g1, c12029_g2) was described before and predicted to be an aphid effectors to promote aphid infestation. Unigene c13074_g1 and c29740_g1 were annotated as MLH and TPR, respectively. MLH is a DNA binding protein and involved in plant salt tolerance mechanisms. The gene expression for MLH polyproteins is upregulated in the salt-tolerant genotype of Acer palmatum, suggesting it is involved in the improvement of plant resistance to abiotic stress101. The TPR motif is a protein-protein interaction module, which is important for the functioning of chaperones, cell-cycle, transcription, protein transport complexes and the gibberellin signal transduction pathway102,103. Gibberellins (GAs) represent an important class of plant hormones that control growth and developmental processes. We predict that TPR secreted by aphids may have roles in the interactions with plant proteins and affect plant development. The RT-PCR and RT-qPCR results showed that all of these highly expressed transcripts were specifically expressed in aphid salivary glands (Fig. 5a,b). Relative expression of the most highly expressed unigenes c10120_g1 and c12029_g2 (GLD) in salivary gland was 238.5 ± 27.7 and 823.3 ± 51.9 times higher than in the whole body, respectively. These highly expressed salivary gland-specific genes may play vital roles in aphid-plant interactions, and are worth further analysis.

Figure 5.

RT-PCR (a) and RT-qPCR (b) results of relative gene expression of the 15 most highly expressed putative secretory proteins of S. avenae salivary glands in different tissues. Abbreviation for unigenes: micronuclear linker histone polyprotein (MLH), glucose dehydrogenase (GLD); tetratricopeptide repeat protein (TPR). Tissues: salivary glands (SG); alimentary canals (AC); whole body of apterous adult (WB); whole body minus salivary glands of apterous adult (-SG). β-actin and NADH were used as an internal reference genes. In RT-PCR, the similar intensity of β-actin bands among different tissues indicates the equal concentrations of each template. Electrophoresis of all unigenes are run under the same PCR conditions. The display for each unigenes are cropped figures from the gels. The full-length gels are presented in Supplementary Figure 3. Standard error (SE) is represented by the error bar. Different small letters above each bar indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Among 9 genes of interest, β-MAN, MAL and PLD were detected in the transcriptome of S. avenae salivary glands, but the RT-PCR and RT-qPCR results showed that the expression levels of these transcripts in alimentary canal were significantly higher than in other tissues. The expression levels of ACE and putative Ca2+ binding proteins RCN in salivary glands were significantly higher than those in other tissues. GST-1 transcript was specifically expressed in the salivary glands. Aphid salivary protein with GST activity involved in modifying plant defense responses, overexpression of a single putative GST protein named Me47 detected in M. euphorbiae saliva could induce or suppress plant defense depending on different host plants104. TRE and CALU had high expression in both salivary glands and alimentary canal. In our study, RT-PCR and qPCR results showed that RGN was very low in the salivary glands compared with its levels in the alimentary canal and whole body (Fig. 6a,b). RGN was found exclusively in the anterior fat bodies of the flesh fly Sarcophaga peregrine 105, whereas the RGN protein was detected in the watery saliva of A.pisum 34, suggesting that RGN may be mainly produced in the alimentary canal and other tissues such as fat bodies, then transported from the haemolymph into the salivary gland to be secreted into the host.

Figure 6.

RT-PCR (a) and qRT-PCR (b) results of relative gene expression of 9 interested putative secretory proteins of S. avenae salivary glands in different tissues. The display for each unigenes are cropped figures from the gels. The full-length gels are presented in Supplementary Figure 4. Abbreviation for unigenes: beta-mannosidase (β-MAN), maltase A1 (MAL), glutathione-S-transferase 1 (GST-1) phospholipase D (PLD), trehalase (TRE), angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), regucalcin (RGN), reticulocalbin-2 (RCN), calumenin (CALU). Tissues: salivary glands (SG); alimentary canals (AC); whole body of apterous adult (WB); whole body minus salivary glands of apterous adult (-SG). β- actin and NADH were used as the internal reference genes. Standard error (SE) is represented by the error bar. Different small letters above each bar indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

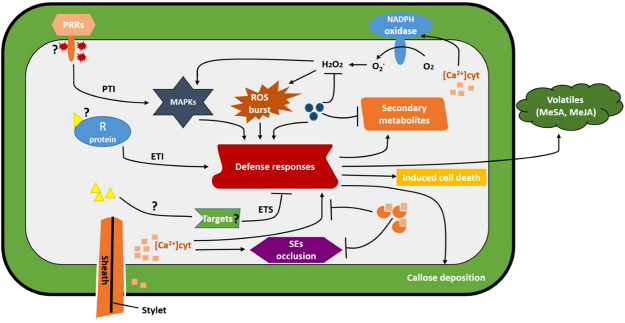

In conclusion, we revealed the transcripts of the salivary glands of S. avenae using Illumina HiSeq 2500. Five hundred and twenty five putative secretory proteins that were expected to be secreted into plants and may play critical roles in aphid-host interactions were identified. Among of them, some highly and salivary gland-specifically expressed genes were also uncovered, but most of these putative secretory proteins were still function-unknown, which are worthy of further study. We also suggest a model describing the potential roles of some salivary proteins in aphid-host interactions (Fig. 7). Further investigations are needed to confirm these predicted secreted proteins at the proteomic level for a more comprehensive understanding of the composition of its saliva. RNA interference (RNAi)69–71 and transient over-expression of aphid candidate effectors in model plants or non-model crops such as wheat or barley20,106,107 and yeast two-hybrid screening108 are also valuable approach to further investigate the function of aphid salivary proteins in aphid-host interactions.

Figure 7.

Schematic drawing of potential roles of secretory proteins from aphid saliva in aphid–plant interactions. During probing and feeding, the aphid secretes saliva into the cytoplasm of the plant cell. Digestive and detoxification enzymes ( ) in salivary proteins facilitate probing and feeding because these enzymes are involved in the breaking down cell walls and membranes, metabolizing sugars and amino acids, and detoxifying secondary metabolites in plant tissues. Some digestive enzymes and degradative products also can induce plant defense responses as potential effectors. Some effectors (

) in salivary proteins facilitate probing and feeding because these enzymes are involved in the breaking down cell walls and membranes, metabolizing sugars and amino acids, and detoxifying secondary metabolites in plant tissues. Some digestive enzymes and degradative products also can induce plant defense responses as potential effectors. Some effectors ( ) in saliva can be recognized by plant transmembrane pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), resulting in the induction of plant basal defenses (pattern-triggered immunity, PTI). Aphid also secretes other effectors (

) in saliva can be recognized by plant transmembrane pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), resulting in the induction of plant basal defenses (pattern-triggered immunity, PTI). Aphid also secretes other effectors ( ) to suppress plant defenses to promote infestation, resulting in effector-triggered susceptibility (ETS). However, in resistant interactions, an effector (

) to suppress plant defenses to promote infestation, resulting in effector-triggered susceptibility (ETS). However, in resistant interactions, an effector ( ) can be specifically recognized by plant resistance proteins (R proteins) according to the gene for gene hypothesis, resulting in a stronger defense responses, effector-triggered immunity (ETI) such as induced cell death. Penetration of plant cell membranes by aphids causes an increase in the cytosolic concentration of Ca2+ ([Ca2+]cyt), resulting in sieve pore occlusion and calcium signaling for defense responses such as the reactive oxygen species (ROS) burst. Ca2+ -binding proteins (

) can be specifically recognized by plant resistance proteins (R proteins) according to the gene for gene hypothesis, resulting in a stronger defense responses, effector-triggered immunity (ETI) such as induced cell death. Penetration of plant cell membranes by aphids causes an increase in the cytosolic concentration of Ca2+ ([Ca2+]cyt), resulting in sieve pore occlusion and calcium signaling for defense responses such as the reactive oxygen species (ROS) burst. Ca2+ -binding proteins ( ) injected with saliva can bind Ca2+, thereby preventing sieve pore blockage and calcium signaling pathways. Also, the hole in the membrane created by the aphid can be sealed after the secreted gelling saliva solidifies into a sheath, minimizing the influx of Ca2+ and downstream plant defense responses. However, few effectors have been identified, and details of the mechanisms involved in aphid–plant interaction are still unknown. Abbreviations: SEs: sieve elements MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; MeSA: menthyl salicylate; MeJA: methyl jasmonate.

) injected with saliva can bind Ca2+, thereby preventing sieve pore blockage and calcium signaling pathways. Also, the hole in the membrane created by the aphid can be sealed after the secreted gelling saliva solidifies into a sheath, minimizing the influx of Ca2+ and downstream plant defense responses. However, few effectors have been identified, and details of the mechanisms involved in aphid–plant interaction are still unknown. Abbreviations: SEs: sieve elements MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; MeSA: menthyl salicylate; MeJA: methyl jasmonate.

Materials and Methods

Insect rearing

A clone of S. avenae was initially established from a single aphid collected from wheat field in Langfang, Hebei Province, China and has been reared on wheat plants (variety Beijing 837, which is susceptible to S. avenae) for 5 yr in an indoor environment at 20 ± 1 °C, 75–80% relative humidity and 16 h light/8 h dark.

Sample collection and RNA isolation

About 600 pairs of salivary glands were individually dissected from apterous and alate adult aphids in phosphate buffered saline (pH = 7.2, Hyclone, Thermo Scientific, MA, USA) respectively, then quickly transferred to TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) on ice. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol Reagent following the manufacturer’s instructions and stored at −80 °C until used. RNA concentration was measured using Qubit RNA Assay Kit and Qubit 2.0 Flurometer (Life Technologies, CA, USA). RNA integrity was assessed using the RNA Nano 6000 Assay Kit and the Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). Three micrograms total RNA sample with standard quality (1.8 < OD260/280 < 2.1, RIN values > 8.0) was prepared for further sequencing.

Illumina sequencing, assembly, and annotation

NEBNext® Ultra™ RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® (New England Biolabs (NEB), Beverly, MA, USA) was used to generate the sequencing libraries following the manufacturers’ introductions. Firstly, mRNA was purified from total RNA sample using poly-T oligo-attached magnetic beads. Fragmentation was performed using divalent cations under elevated temperature in NEBNext First Strand Synthesis Reaction Buffer (5×). First strand cDNA synthesis was carried out using M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase and random hexamers, then second strand cDNA was synthesized using DNA polymerase I and RNase H. The remaining overhangs were converted into blunt ends using exonuclease/polymerase activities. After adenylation of 3′ ends of DNA fragments, NEBNext Adaptors were ligated to DNA fragments for hybridization. The library fragments were purified with the AMPure XP system to select the cDNA fragments with a length between 150 and 200 bp. Three microlitres USER Enzyme (NEB, USA) was used with size-selected, adaptor-ligated DNA at 37 °C for 15 min followed by 5 min at 95 °C, PCR was then performed to amplify cDNA with Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase, Universal PCR primers and Index (X) Primer. The PCR products were purified with AMPure XP system and quantified using the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). The clustering of the index-coded samples was performed on a cBot Cluster Generation System using TruSeq PE Cluster Kit v3-cBot-HS (Illumina, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

After cluster generation, the library preparations were sequenced using an Illumina HiSeq. 2500/Miseq platform and paired-end reads (the sequencing strategy was PE150). The clean reads were obtained after adaptor sequences, ambiguous “N” nucleotides (the percentage of “N” > 10%) and low-quality sequences (the ratio of nucleotides with Qphred ≤ 5 was more than 50%) were removed from raw reads. The clean reads were assembled using Trinity r20140413p1 min_kmer_cov:2 and the other default parameters as described for de novo transcriptome assembly without a reference genome to generate transcripts and unigenes109. For homology searches and annotation, all unigenes were used in a search of public databases including non-redundant protein (Nr, e-value ≦ 1.0e−5), nucleotide sequence (Nt, e-value ≦ 1.0e−5), Pfam (e-value ≦ 0.01), euKaryotic Ortholog Groups (KOG)/Clusters of Orthologous Groups of proteins (COG, e-value ≦ 1.0e−3) and Swiss-Prot (e-value ≦ 1.0e−5). Functional annotation by Gene Ontology (GO) term was analyzed using Blast2GO with a cutoff value of E-value ≦ 1.0E−6. Pathways were annotated by KEGG Automatic Annotation Server (KAAS) based on the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) with a cutoff value of E-value ≦ 1.0E−10.

Putative secretory proteins

Open reading frames (ORFs) within transcript sequences generated by de novo RNA-Seq transcript assembly using Trinity were identified using TransDecoder v3.0.0 (https://github.com/TransDecoder/TransDecoder/releases). Signal peptides and cleavage sites in amino acid sequences were predicted by the SignaIP 4.1 Server (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/). For transmembrane domains prediction, amino acid sequences with a signal peptide were submitted to the TMHMM Server v. 2.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/ services/TMHMM/). Putative proteins with a signal peptide and 0–1 transmembrane domain (the signal peptide can be a transmembrane domain) were considered to be potential secreted proteins25.

RT-PCR and RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from 600 salivary glands, 450 alimentary canals, 10 whole bodies of apterous adult aphids and 10 whole bodies minus salivary glands as mentioned before. The cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg RNA using TransScript One-Step gDNA Removal and cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China) for RT-PCR and qRT-PCR. All specific primers for RT-PCR and qRT-PCR were designed with Primer Premier 5.0 (PREMIER Biosoft, CA, USA) and are shown in (Supplementary Table 4). β-Actin and NADH dehydrogenase (NADH) were used as reference genes to normalize target gene expression110,111. All PCR products were sequenced (Sunbiotech, Beijing, China).

RT-PCR was conducted in a 20 μL reaction volume containing 10 μL 2 × Taq PCR MasterMix (BioMed, Beijing, China), 2 μL cDNA, 1 μL each forward and reverse primer (10 μM), 6 μL ddH2O. The RT-PCR conditions were 3 min at 94 °C; 28 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 60 °C and 30 s at 72 °C; and final 10 min at 72 °C. PCR products were separated in 1% agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA). RT-qPCR was performed using an ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA).cDNA was diluted 10-fold and then used as the template to determine the relative expression of the target gene in a 20 μL reaction volume containing 2 μL cDNA, 0.5 μL each of 10 μmol L−1 forward primer and reverse primer, 10 μL of 2 × SYBR premix Ex Taq (Tli RNaseH Plus, Takara, Dalian, China) and 0.4 μL of 50 × ROX Reference Dye II (Tli RNaseH Plus, Takara, Dalian, China) at the following conditions: 30 s at 95 °C; followed by 40 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, and 30 s at 60 °C. RT-qPCR reaction for each sample was carried out with 3 biological replicates and 3 technical replicates.

RT-qPCR data analysis

Each treatment was performed in triplicate, and the differential expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method112. The fold-change in expression of the unigenes in different tissues to the whole body of apterous adult aphid was calculated. Results were expressed as Means ± SE. All data were analyzed using SAS 9.1 software (SAS Institute Inc., NC, USA) and the differences among groups were examined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test. P values less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the technician, Ms Yanxia Liu for aphid rearing. This work was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31371946, 31401740), National Key R&D Plan in China (2016YFD0300701, 2017YFD- 0201701) and Cooperation Project between China and Belgium from Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) (2014DFG32270).

Author Contributions

Y.Z. and J.F. did the salivary gland dissection and wrote the manuscript. Y.Z. and J.R.S. analyzed all the transcriptomes and qPCR results. F.F. and J.L.C. designed the experiments and revised the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-16092-z.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Frédéric Francis, Email: Frederic.Francis@ulg.ac.be.

Julian Chen, Email: jlchen@ippcaas.cn.

References

- 1.Veivers PC, Musca AM, O’Brien RW, Slaytor M. Digestive enzymes of the salivary glands and gut of Mastotermes darwiniensis. Insect Biochem. 1982;12:35–40. doi: 10.1016/0020-1790(82)90068-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miles PW, Peng Z. Studies on the salivary physiology of plant bugs: Detoxification of phytochemicals by the salivary peroxidase of aphids. J.Insect Physiol. 1989;35:865–872. doi: 10.1016/0022-1910(89)90102-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu-Salzman K, Bi JL, Liu TX. Molecular strategies of plant defense and insect counter-defense. Insect Sci. 2005;12:3–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1672-9609.2005.00002.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Musser RO, et al. Herbivory: caterpillar saliva beats plant defences. Nature. 2002;416:599–600. doi: 10.1038/416599a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Will T, van Bel AJE. Induction as well as suppression: How aphid saliva may exert opposite effects on plant defense. Plant Signal. Behav. 2008;3:427–430. doi: 10.4161/psb.3.6.5473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Consales F, et al. Insect oral secretions suppress wound-induced responses in. Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2011;63:727–737. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miles P. Insect secretions in plants. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1968;6:137–164. doi: 10.1146/annurev.py.06.090168.001033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miles PW. Secretion of two types of saliva by an aphid. Nature. 1959;183:756–756. doi: 10.1038/183756b0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miles PW. Aphid saliva. Biol. Rev. 1999;74:41–85. doi: 10.1017/S0006323198005271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Will T, Steckbauer K, Hardt M, van Bel AJ. Aphid gel saliva: sheath structure, protein composition and secretory dependence on stylet-tip milieu. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46903. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones JD, Dangl JL. The plant immune system. Nature. 2006;444:323–329. doi: 10.1038/nature05286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaloshian I, Walling LL. Hemipterans as plant pathogens. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2005;43:491–521. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.43.040204.135944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chisholm ST, Coaker G, Day B, Staskawicz BJ. Host-microbe interactions: shaping the evolution of the plant immune response. Cell. 2006;124:803–814. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vallet-Gely I, Lemaitre B, Boccard F. Bacterial strategies to overcome insect defences. Nat. Rev. Micro. 2008;6:302–313. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hogenhout SA, Bos JIB. Effector proteins that modulate plant–insect interactions. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2011;14:422–428. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walling LL. Avoiding effective defenses: Strategies employed by phloem-feeding insects. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:859–866. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.113142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Vos M, Jander G. Myzus persicae (green peach aphid) salivary components induce defence responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Environ. 2009;32:1548–1560. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tjallingii WF. Salivary secretions by aphids interacting with proteins of phloem wound responses. J. Exp. Bot. 2006;57:739–745. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mutti NS, et al. A protein from the salivary glands of the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum, is essential in feeding on a host plant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:9965–9969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708958105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bos JI, et al. A functional genomics approach identifies candidate effectors from the aphid species Myzus persicae (green peach aphid) PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atamian HS, et al. In planta expression or delivery of potato aphid Macrosiphum euphorbiae effectors Me10 and Me23 enhances aphid fecundity. Mol. Plant Microbe. Interact. 2013;26:67–74. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-06-12-0144-FI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodriguez PA, Stam R, Warbroek T, Bos JI. Mp10 and Mp42 from the aphid species Myzus persicae trigger plant defenses in Nicotiana benthamiana through different activities. Mol. Plant Microbe. Interact. 2014;27:30–39. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-05-13-0156-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delay B, Mamidala P, Wijeratne A. Transcriptome analysis of the salivary glands of potato leafhopper. Empoasca fabae. J. Insect Physiol. 2012;58:1626–1634. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Su YL, et al. Transcriptomic analysis of the salivary glands of an invasive whitefly. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39303. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ji R, et al. Comparative transcriptome analysis of salivary glands of two populations of rice brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens, that differ in virulence. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79612. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsumoto Y, Suetsugu Y, Nakamura M, Hattori M. Transcriptome analysis of the salivary glands of Nephotettix cincticeps (Uhler) J. Insect Physiol. 2014;71:170–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Showmaker KC, et al. Insight into the salivary gland transcriptome of Lygus lineolaris (Palisot de Beauvois) PLoS One. 2016;11:e0147197. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harmel N, et al. Identification of aphid salivary proteins: a proteomic investigation of Myzus persicae. Insect Mol. Biol. 2008;17:165–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2008.00790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carolan JC, et al. Predicted effector molecules in the salivary secretome of the pea aphid (Acyrthosiphon pisum): a dual transcriptomic/proteomic approach. J. Proteome Res. 2011;10:1505–1518. doi: 10.1021/pr100881q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scheller H, Shukle R. Feeding behavior and transmission of barley yellow dwarf virus by Sitobion avenae on oats. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 1986;40:189–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1570-7458.1986.tb00501.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carter, N., Dixon, A. F. G. & Rabbinge, R. Cereal aphid populations: biology, simulation and prediction. (Centre for Agricultural Publishing and Documentation (Pudoc), 1982).

- 32.Liu Y, Wang WL, Guo GX, Ji XL. Volatile emission in wheat and parasitism by Aphidius avenae after exogenous application of salivary enzymes of Sitobion avenae. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2009;130:215–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1570-7458.2008.00822.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma R, Chen JL, Cheng DF, Sun JR. Activation of defense mechanism in wheat by polyphenol oxidase from aphid saliva. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2010;58:2410–2418. doi: 10.1021/jf9037248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rao SA, Carolan JC, Wilkinson TL. Proteomic profiling of cereal aphid saliva reveals both ubiquitous and adaptive secreted proteins. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57413. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wohlfarth-Bottermann K, Moericke V. Zur funktionellen Morphologie der Speicheldrüsen von Homopteren. Cell Tissue Res. 1960;52:346–361. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ng JC, Perry KL. Transmission of plant viruses by aphid vectors. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2004;5:505–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2004.00240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grabherr MG, et al. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011. Trinity: reconstructing a full-length transcriptome without a genome from RNA-Seq data; pp. 644–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Young MD, Wakefield MJ, Smyth GK, Oshlack A. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R14. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-2-r14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tatusov RL, et al. The COG database: an updated version includes eukaryotes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2003;4:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kanehisa M, et al. KEGG for linking genomes to life and the environment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:480–484. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stålbrand H, Saloheimo A, Vehmaanperä J, Henrissat B, Penttilä M. Cloning and expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae of a Trichoderma reesei beta-mannanase gene containing a cellulose binding domain. Appl. Environ. Microb. 1995;61:1090–1097. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.3.1090-1097.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hayashi H, Chino M. Collection of pure phloem sap from wheat and its chemical composition. Plant Cell Physiol. 1986;27:1387–1393. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a077237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bari R, Jones JDG. Role of plant hormones in plant defence responses. Plant Mol. Biol. 2009;69:473–488. doi: 10.1007/s11103-008-9435-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bennett RN, Wallsgrove RM. Secondary metabolites in plant defence mechanisms. New Phytol. 1994;127:617–633. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1994.tb02968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Niemeyer HM, et al. Changes in hydroxamic acid levels of wheat plants induced by aphid feeding. Phytochemistry. 1989;28:447–449. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(89)80029-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahmad S, et al. Benzoxazinoid metabolites regulate innate immunity against aphids and fungi in maize. Plant Physiol. 2011;157:317–327. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.180224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morkunas I, Mai VC, Gabryś B. Phytohormonal signaling in plant responses to aphid feeding. Acta Physiol. Plantarum. 2011;33:2057–2073. doi: 10.1007/s11738-011-0751-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Després L, David J-P, Gallet C. The evolutionary ecology of insect resistance to plant chemicals. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007;22:298–307. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li X, Schuler MA, Berenbaum MR. Molecular mechanisms of metabolic resistance to synthetic and natural xenobiotics. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2007;52:231–253. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.51.110104.151104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nicholson SJ, Hartson SD, Puterka GJ. Proteomic analysis of secreted saliva from Russian wheat aphid (Diuraphis noxia Kurd.) biotypes that differ in virulence to wheat. J. Proteomics. 2012;75:2252–2268. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vandermoten S, et al. Comparative analyses of salivary proteins from three aphid species. Insect Mol. Biol. 2014;23:67–77. doi: 10.1111/imb.12061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chaudhary R, Atamian HS, Shen Z, Briggs SP, Kaloshian I. Potato aphid salivary proteome: enhanced salivation using resorcinol and identification of aphid phosphoproteins. J. Proteome Res. 2015;14:1762–1778. doi: 10.1021/pr501128k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen M-S, et al. Analysis of transcripts and proteins expressed in the salivary glands of Hessian fly (Mayetiola destructor) larvae. J. Insect Physiol. 2008;54:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kusnierczyk A, et al. Towards global understanding of plant defence against aphids–timing and dynamics of early Arabidopsis defence responses to cabbage aphid (Brevicoryne brassicae) attack. Plant Cell Environ. 2008;31:1097–1115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2008.01823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moloi MJ, van der Westhuizen AJ. The reactive oxygen species are involved in resistance responses of wheat to the Russian wheat aphid. J. Plant Physiol. 2006;163:1118–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alosi MC, Melroy DL, Park RB. T The regulation of gelation of phloem exudate from cucurbita fruit by dilution, glutathione, and glutathione reductase. Plant Physiol. 1988;86:1089–1094. doi: 10.1104/pp.86.4.1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tokuda G, Saito H, Watanabe H. A digestive beta-glucosidase from the salivary glands of the termite, Neotermes koshunensis (Shiraki): distribution, characterization and isolation of its precursor cDNA by 5′- and 3′-RACE amplifications with degenerate primers. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2002;32:1681–1689. doi: 10.1016/S0965-1748(02)00108-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hopke J, Donath J, Blechert S, Boland W. Herbivore-induced volatiles: the emission of acyclic homoterpenes from leaves of Phaseolus lunatus and Zea mays can be triggered by a beta-glucosidase and jasmonic acid. FEBS Lett. 1994;352:146–150. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00948-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mattiacci L, Dicke M, Posthumus M. A. beta-Glucosidase: an elicitor of herbivore-induced plant odor that attracts host-searching parasitic wasps. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:2036–2040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.6.2036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang X, et al. β-Glucosidase treatment and infestation by the rice brown planthopper Nilaparvata lugens elicit similar signaling pathways in rice plants. Chinese Sci. Bull. 2008;53:53–57. doi: 10.1007/s11434-008-0048-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Valenzuela JG, Francischetti IM, Pham VM, Garfield MK, Ribeiro JM. Exploring the salivary gland transcriptome and proteome of the Anopheles stephensi mosquito. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2003;33:717–732. doi: 10.1016/S0965-1748(03)00067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shukle RH, Mittapalli O, Morton PK, Chen MS. Characterization and expression analysis of a gene encoding a secreted lipase-like protein expressed in the salivary glands of the larval Hessian fly, Mayetiola destructor (Say) J. Insect Physiol. 2009;55:104–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Francischetti IM, Lopes AH, Dias FA, Pham VM, Ribeiro JM. An insight into the sialotranscriptome of the seed-feeding bug. Oncopeltus fasciatus. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2007;37:903–910. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schäfer M, et al. Lipase activity in insect oral secretions mediates defense responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2011;156:1520–1534. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.173567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bargmann BO, Munnik T. The role of phospholipase D in plant stress responses. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2006;9:515–522. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang X. The role of phospholipase D in signaling cascades. Plant Physiol. 1999;120:645–652. doi: 10.1104/pp.120.3.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.De TZM, Fernandez-Delmond I, Niittyla T, Sanchez P, Grant M. Differential expression of genes encoding Arabidopsis phospholipases after challenge with virulent or avirulent Pseudomonas isolates. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2002;15:808–816. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2002.15.8.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Young SA, Wang X, Leach JE. Changes in the plasma membrane distribution of rice phospholipase D during resistant interactions with Xanthomonas oryzae pv oryzae. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1079–1090. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.6.1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mutti NS, Park Y, Reese JC, Reeck GR. RNAi knockdown of a salivary transcript leading to lethality in the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum. J. Insect Sci. 2006;6:1–7. doi: 10.1673/031.006.3801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pitino M, Coleman AD, Maffei ME, Ridout CJ, Hogenhout SA. Silencing of aphid genes by dsRNA feeding from plants. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang Y, Fan J, Sun JR, Chen JL. Cloning and RNA interference analysis of the salivary protein C002 gene in Schizaphis graminum. J. Integr. Agr. 2015;14:698–705. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(14)60822-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Carolan JC, Fitzroy CI, Ashton PD, Douglas AE, Wilkinson TL. The secreted salivary proteome of the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum characterised by mass spectrometry. Proteomics. 2009;9:2457–2467. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Corvol P, Michaud A, Soubrier F, Williams TA. Recent advances in knowledge of the structure and function of the angiotensin I converting enzyme. J. Hypertens. Suppl. 1995;13:3–10. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199509003-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Macours N, Hens K, Francis C, De Loof A, Huybrechts R. Molecular evidence for the expression of angiotensin converting enzyme in hemocytes of Locusta migratoria: stimulation by bacterial lipopolysaccharide challenge. J. Insect Physiol. 2003;49:739–746. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1910(03)00110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lemeire E, Vanholme B, Van Leeuwen T, Van Camp J, Smagghe G. Angiotensin-converting enzyme in Spodoptera littoralis: molecular characterization, expression and activity profile during development. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2008;38:166–175. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wijffels G, Gough J, Muharsini S, Donaldson A, Eisemann C. Expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxydipeptidases in the larvae of four species of fly. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1997;27:451–460. doi: 10.1016/S0965-1748(97)00020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang W, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzymes modulate aphid-plant interactions. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:8885. doi: 10.1038/srep08885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Elbein AD, Pan YT, Pastuszak I, Carroll D. New insights on trehalose: a multifunctional molecule. Glycobiology. 2003;13:17–27. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwg047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Grennan AK. The role of trehalose biosynthesis in plants. Plant Physiol. 2007;144:3–5. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.900223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Iordachescu M, Imai R. Trehalose biosynthesis in response to abiotic stresses. J.Integr. Plant Biol. 2008;50:1223–1229. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Almeida AM, et al. Transformation of tobacco with an Arabidopsis thaliana gene involved in trehalose biosynthesis increases tolerance to several abiotic stresses. Euphytica. 2005;146:165–176. doi: 10.1007/s10681-005-7080-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Brodmann A, et al. Induction of trehalase in Arabidopsis plants infected with the trehalose-producing pathogen Plasmodiophora brassicae. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2002;15:693–700. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2002.15.7.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bae H, Herman E, Bailey B, Bae HJ, Sicher R. Exogenous trehalose alters Arabidopsis transcripts involved in cell wall modification, abiotic stress, nitrogen metabolism, and plant defense. Physiol. Plantarum. 2005;125:114–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2005.00537.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Thorpe P, Cock PJ, Bos J. Comparative transcriptomics and proteomics of three different aphid species identifies core and diverse effector sets. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:172. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2496-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Missbach C, Vogel H, Hansson BS, Grobetae-Wilde E. Identification of odorant binding proteins and chemosensory proteins in antennal transcriptomes of the jumping bristletail Lepismachilis y-signata and the firebrat Thermobia domestica: Evidence for an independent OBP-OR Origin. Chem. Senses. 2015;40:615–626. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjv050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dippel S, et al. Tissue-specific transcriptomics, chromosomal localization, and phylogeny of chemosensory and odorant binding proteins from the red flour beetle Tribolium castaneum reveal subgroup specificities for olfaction or more general functions. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:1141. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gu SH, et al. Identification of genes expressed in the sex pheromone gland of the black cutworm Agrotis ipsilon with putative roles in sex pheromone biosynthesis and transport. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:636. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fan J, Francis F, Liu Y, Chen JL, Cheng DF. An overview of odorant-binding protein functions in insect peripheral olfactory reception. Genet. Mol. Res. 2011;10:3056–3069. doi: 10.4238/2011.December.8.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Stathopoulos A, Van Drenth M, Erives A, Markstein M, Levine M. Whole-genome analysis of dorsal-ventral patterning in the Drosophila embryo. Cell. 2002;111:687–701. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nomura A, Kawasaki K, Kubo T, Natori S. Purification and localization ofp10, a novel protein that increases in nymphal regenerating legs of Periplaneta americana (American cockroach) Int. J. Dev. Biol. 1992;36:391–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sim S, Ramirez JL, Dimopoulos G. Dengue virus infection of the Aedes aegypti salivary gland and chemosensory apparatus induces genes that modulate infection and blood-feeding behavior. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002631. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Calvo E, Mans BJ, Andersen JF, Ribeiro JM. Function and evolution of a mosquito salivary protein family. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:1935–1942. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510359200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Celorio-Mancera Mde L, et al. Chemosensory proteins, major salivary factors in caterpillar mandibular glands. Insect Biochem. Mol. Bio. 2012;42:796–805. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Liu YL, Guo H, Huang LQ, Pelosi P, Wang CZ. Unique function of a chemosensory protein in the proboscis of two Helicoverpa species. J. Exp. Biol. 2014;217:1821–1826. doi: 10.1242/jeb.102020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Elzinga DA, De Vos M, Jander G. Suppression of plant defenses by a Myzus persicae (green peach aphid) salivary effector protein. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2014;27:747–756. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-01-14-0018-R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lecourieux D, Ranjeva R, Pugin A. Calcium in plant defence-signalling pathways. New Phytol. 2006;171:249–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Maffei ME, Mithofer A, Boland W. Before gene expression: early events in plant-insect interaction. Trends Plant Sci. 2007;12:310–316. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Furch AC, Hafke JB, Schulz A, van Bel AJ. Ca2+-mediated remote control of reversible sieve tube occlusion in Vicia faba. J. Exp. Bot. 2007;58:2827–2838. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Will T, Tjallingii WF, Thonnessen A, van Bel AJ. Molecular sabotage of plant defense by aphid saliva. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:10536–10541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703535104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Will T, Kornemann SR, Furch AC, Tjallingii WF, van Bel AJ. Aphid watery saliva counteracts sieve-tube occlusion: a universal phenomenon? J. Exp. Biol. 2009;212:3305–3312. doi: 10.1242/jeb.028514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rong L, Li Q, Li S, Tang L, Wen J. De novo transcriptome sequencing of Acer palmatum and comprehensive analysis of differentially expressed genes under salt stress in two contrasting genotypes. Mol. Genet. Genomics. 2016;291:575–586. doi: 10.1007/s00438-015-1127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Blatch GL, Lassle M. The tetratricopeptide repeat: a structural motif mediating protein-protein interactions. BioEssays. 1999;21:932–939. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199911)21:11<932::AID-BIES5>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Jacobsen SE, Binkowski KA, Olszewski NE. SPINDLY, a tetratricopeptide repeat protein involved in gibberellin signal transduction in. Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:9292–9296. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kettles GJ, Kaloshian I. The potato aphid salivary effector Me47 is a glutathione-S-transferase involved in modifying plant responses to aphid infestation. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:1142. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nakajima Y, Natori S. Identification and characterization of an anterior fat body protein in an insect. J. Biochem. 2000;127:901–908. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Thomas WJ, Thireault CA, Kimbrel JA, Chang JH. Recombineering and stable integration of the Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae 61 hrp/hrc cluster into the genome of the soil bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf0-1. Plant J. 2009;60:919–928. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Upadhyaya, N. M., Ellis, J. G. & Dodds, P. N. A bacterial type III secretion-based delivery system for functional assays of fungal effectors in cereals. Plant-Pathogen Interactions: Methods and Protocols, (eds Paul, B. et al.) 277–290 (Springer, 2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 108.Lu S. Use of the yeast two-hybrid system to identify targets of fungal effectors. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012;835:165–189. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-501-5_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Grabherr MG, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotech. 2011;29:644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Xue W, et al. Identification and expression analysis of candidate odorant-binding protein and chemosensory protein genes by antennal transcriptome of Sitobion avenae. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0161839. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zhang M, et al. Identifying potential RNAi targets in grain aphid (Sitobion avenae F.) based on transcriptome profiling of its alimentary canal after feeding on wheat plants. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:560. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.