Abstract

Objectives

There have been conflicting reports of altered vaginal microbiota and infection susceptibility associated with contraception use. The objectives of this study were to determine if intrauterine contraception altered the vaginal microbiota and to compare the effects of a copper intrauterine device (Cu-IUD) and a levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) on the vaginal microbiota.

Study Design

DNA was isolated from the vaginal swab samples of 76 women using Cu-IUD (n=36) or LNG-IUS (n=40) collected prior to insertion of intrauterine contraception (baseline) and at 6 months. A third swab from approximately 12 months following insertion was available for 69 (Cu-IUD, n=33; LNG-IUS, n=36) of these women. The V4 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA-encoding gene was amplified from the vaginal swab DNA and sequenced. The 16S rRNA gene sequences were processed and analyzed using the software package mothur to compare the structure and dynamics of the vaginal bacterial communities.

Results

The vaginal microbiota from individuals in this study clustered into 3 major vaginal bacterial community types: one dominated by Lactobacillus iners, one dominated by Lactobacillus crispatus and one community type that was not dominated by a single Lactobacillus species. Changes in the vaginal bacterial community composition were not associated with the use of Cu-IUD or LNG-IUS. Additionally, we did not observe a clear difference in vaginal microbiota stability with Cu-IUD versus LNG-IUS use.

Conclusions

Although the vaginal microbiota can be highly dynamic, alterations in the community associated with the use of intrauterine contraception (Cu-IUD or LNG-IUS) were not detected over 12 months.

Implications

We found no evidence that intrauterine contraception (Cu-IUD or LNG-IUS) altered the vaginal microbiota composition. Therefore, the use of intrauterine contraception is unlikely to shift the composition of the vaginal microbiota such that infection susceptibility is altered.

Keywords: Vaginal microbiota, 16S rRNA gene, intrauterine contraception, bacterial community

Introduction

With nearly half of all pregnancies in the United States considered unintended (45% in 2011), options for safe and effective contraception are critical [1]. Intrauterine contraception, both the non-hormonal copper intrauterine device (Cu-IUD) and the hormonal levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS), offer women a long-acting, reversible and highly effective choice for contraception option [2]. To date few studies have investigated the effects of intrauterine devices (IUDs) on the vaginal microbiota and infection susceptibility and thus far the results have been contradictory. One study found that IUDs increase the likelihood of bacterial vaginosis (BV) [3], whereas another found no association between the two [4]. A recent study by Madden et al, evaluated the rate of BV among users of different contraceptive methods and found IUDs linked with a higher prevalence of BV than other contraceptives (COC, ring, patch) but no significant difference between BV rates of hormonal vs. non-hormonal IUDs [5]. Evaluating if contraceptive use alters vaginal microbiota is important because alterations are associated with sexually transmitted infection (STI) susceptibility.

Vaginal microbiotas dominated by Lactobacillus sp. are common and widely considered to be healthy. Moreover, the low pH and high lactic acid levels typical when Lactobacillus sp. are the dominant members of the vaginal microbiota inhibit other microbes [6–8] and are associated with lower levels of inflammatory markers [9]. The health significance of vaginal communities that are not dominated by Lactobacillus sp. is controversial. Low Lactobacillus levels are one indicator for bacterial vaginosis (BV) and have been associated with increased prevalence, susceptibility and transmission of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis and Trichomonas vaginalis [10–14]. However, many asymptomatic women have vaginal bacterial communities that are not dominated by Lactobacillus sp.[8, 9, 15, 16]. The percentage of asymptomatic women with vaginal microbiotas not dominated by Lactobacillus varies by study (ranging from 7%–63%), depending on subject race/ethnicity [8, 9, 15].

The factors that influence vaginal microbiota composition and dynamics are not well understood. We hypothesized that the Cu-IUD and LNG-IUS would have different effects on the vaginal environment and, thus, potentially different effects on the vaginal microbiota composition and dynamics. Women using Cu-IUDs typically menstruate, often with increased bleeding initially after IUD placement. In contrast, many women using LNG-IUS experience a reduction of menstrual bleeding or amenorrhea. Menstruation has been associated with changes in the vaginal microbiota [17]. Additionally, LNG-IUS use results in thickened cervical mucus [18]. In this study we sought to determine the effects of the Cu-IUD and the LNG-IUS on the vaginal microbiota during the first year of use.

Material and methods

Sample collection

Samples were collected as part of the VAST Substudy of the Contraceptive CHOICE Project (CHOICE), which was approved by the Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine Human Research Protections Office [19]. Informed consent was obtained as described previously [19]. Subjects self-collected their vaginal swab samples, with the baseline samples collected in clinic and the 6 and 12 months samples collected at home and returned by mail. Self-collection has been widely in used in vaginal microbiota studies (e.g. [8]) and has been shown to be equivalent to physician-collected swabs for microbiota analysis [20]. Participants eligible for the VAST Substudy included English-speaking women over the age of 18 who met the eligibility criteria for CHOICE (sexually active women at risk for pregnancy who lived in the St. Louis, Missouri region and did not intend to attempt to conceive within 12 months).

DNA isolation, amplification and sequencing

For our bacterial community analysis, we used a common approach in which different types of bacteria in the vaginal swab samples were detected by the DNA sequences of their 16S rRNA gene. To obtain these 16S rRNA gene sequences, DNA was isolated from vaginal swab samples with a PowerMag Soil DNA Isolation Kit (Mo Bio Laboratories, Inc.) using an epMotion 5075 liquid handling system (Eppendorf). The V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was PCR-amplified from the vaginal swab sample DNA using primers designed by Kozich et. al. [21]. The V4 amplicon pool was prepared and sequenced with a MiSeq (Illumina) as described previously [22].

Sequence processing and analysis overview

The 16S rRNA gene sequence data was processed and analyzed using the software package mothur (v.1.31.2, v.1.34.4, v.1.35.1) and the MiSeq SOP (accessed March 2014, March 2015) [21, 23, 24]. To allow comparisons, sequences were aligned to the SILVA reference alignment [25, 26]. Sequences were then organized into operational taxonomic units (OTUs), with each OTU representing a different type of bacteria. The binning of sequences into OTUs was based on 98% sequence similarity using an average neighbor algorithm [27, 28]. Samples were included in the analysis if a minimum of 3437 sequences were obtained.

To determine how similar bacterial communities from different samples were, we calculated θYC distances, a metric based on relative abundances of both shared and non-shared OTUs, between communities [29]. We used analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) on θYC distances to detect significant differences between the microbiota of different subject groups [30]. We grouped the samples using partitioning around the medoid (PAM) clustering based on θYC distances using the get.communitytype command in mothur. Within subject distances were compared using non-parametric statistical tests — Mann-Whitney test (for pairwise comparisons) and Kruskal-Wallis followed by a Dunn’s multiple comparisons posttest (for multiple comparisons), as appropriate, in Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Additional sequence analysis details are provided in the supplement.

Results

Subject characteristics, sequencing results and samples included

Samples from 76 women were included in this study (Table 1). Characteristics of subjects using LNG-IUS and Cu-IUD were not statistically significantly different by unpaired t test (age, BMI) or Fisher’s exact test (race, baseline STI status). DNA was isolated from vaginal swab samples from all subjects (Cu-IUD, n=36; LNG-IUS, n=40) at baseline and 6 months, and from 69 subjects at 12 months (Cu-IUD, n=33; LNG-IUS, n=36). Ultimately, after processing and exclusion of samples that didn’t meet our cutoffs for sequence numbers, our analyses included 7,974,111 high quality V4 sequences from 209 samples (n=74). Samples included in the analysis had an average of 38,154±15,057 (SD) sequences per sample after processing. Sequence files (fastq) will be deposited in the NCBI’s SRA.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics

| Contraceptive method | LNG-IUS (n=40) | Cu-IUD (n=36) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean±standard deviation) | 26.0±5.0 | 27.6±5.5 |

| Race: Black | 40% (n=16) | 19.4% (n=7) |

| Race: White | 55% (n=22) | 72.2% (n=26) |

| Race: Other | 5% (n=2) | 8.3% (n=3) |

| Baseline BMI (mean±standard deviation) | 27.4±7.0 | 27.0±7.5 |

| Positive for Chlamydia at baseline | 5% (n=2) | 2.8% (n=1) |

| Positive for Gonorrhea at baseline | 2.5% (n=1) | 0% (n=0) |

| Positive for Trichomonas at baseline | 5% (n=2) | 5.6% (n=2) |

Characteristics of subjects using LNG-IUS and Cu-IUD were not statistically significantly different by unpaired t test (age, BMI) or Fisher’s exact test (race, baseline STI status).

Composition of vaginal microbiota: 3 major groups observed

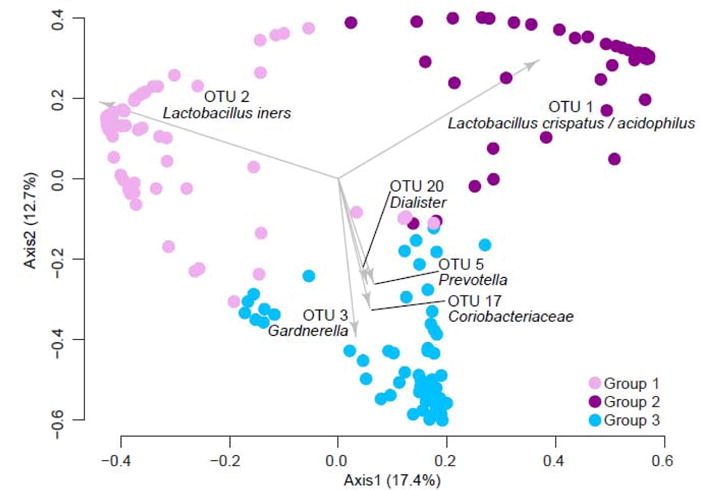

The relationships between the microbiota of each sample, based on θYC distances, were visualized by principle coordinates analysis (PCoA) (Fig. 1). PAM clustering of the communities based on θYC distances between samples was optimal with 3 groups, based on the highest Laplace value found by testing groupings with up to 6 partitions. Group 1 was dominated by L. iners (OTU2), group 2 was dominated by L. crispatus/acidophilus (OTU1) and group 3 was more diverse and not dominated by one type of Lactobacillus (Figure 1 and Supplemental Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) of θYC distances between bacterial communities of baseline, 6 month and 12 month vaginal swab samples.

The PCoA represents θYC distances between samples based on OTUs (98% sequence similarity) of V4 region sequences of 16S rRNA genes. All samples that yielded at least 3437 V4 region sequences (n=209) were included. The three community types are color-coded: Group 1 (OTU2/L. iners dominant), Group 2 (OTU2/L. crispatus/acidophilus dominant) and Group 3 (no dominant Lactobacillus, more diverse). The biplot arrows indicate the top 6 OTUs responsible for the position of samples on the PCoA.

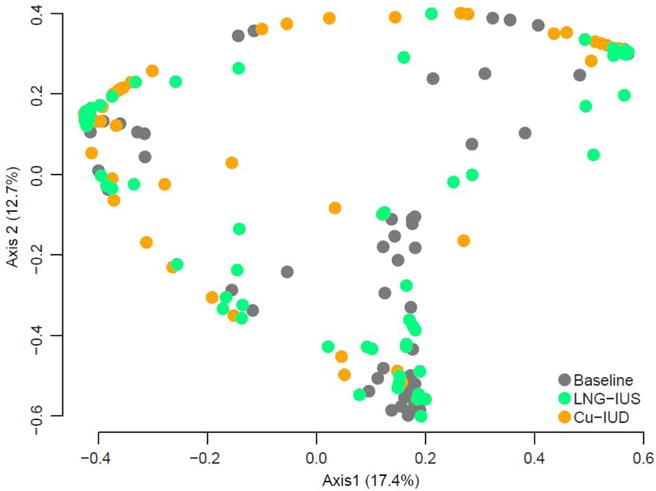

Use of intrauterine contraception was not associated with altered overall community composition

We tested if either type of intrauterine contraception was associated with vaginal community composition by AMOVA on θYC distances between all baseline samples, all (6 and 12 months combined) LNG-IUS samples and all (6 and 12 months combined) Cu-IUD samples. There was no significant difference in overall community composition between baseline samples, LNG-IUS samples and Cu-IUD samples (Figure 2, AMOVA p-value: 0.623). If samples were further split into LNG-IUS baseline, LNG-IUS 6 months, LNG-IUS 12 months, Cu-IUD baseline, Cu-IUD 6 months and Cu-IUD 12 months there was still not a statistically significant difference between groups (AMOVA p-value: 0.945).

Figure 2. Contraceptive status and vaginal bacterial communities.

The same PCoA as in Fig. 1 but color-coded to indicate contraceptive status of the sample. All baseline samples are gray, 6 and 12 month LNG-IUS samples are green and 6 and 12 month Cu-IUD samples are orange. The PCoA represents θYC distances based on OTUs (98% sequence similarity) of V4 region sequences of 16S rRNA. All samples that yielded at least 3437 V4 region sequences (n=209) were included. AMOVA on the θYC distances indicated no differences between vaginal bacterial communities at baseline, after 6 or 12 months with a LNG-IUS and after 6 or 12 months with a Cu-IUD (AMOVA p-value: 0.623).

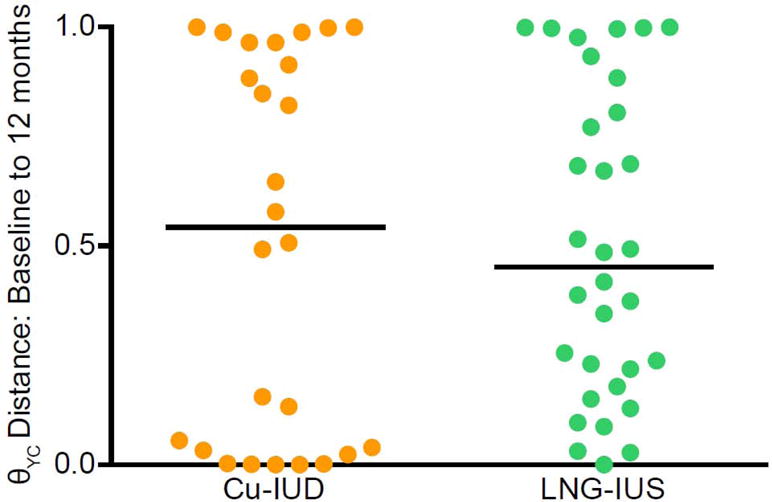

Community stability within women depends on community composition

Although we did not detect an association between vaginal bacterial community composition and the use of either type of intrauterine contraception in the cohort, we wanted to test if Cu-IUDs and LNG-IUSs had different effects on community stability within individual women. To determine community stability, we calculated the θYC distance between communities at baseline and 6 months, between communities at baseline and 12 months, and between 6 months and 12 months within each woman. There was no difference between women with Cu-IUDs and women with LNG-IUSs over 12 months in vaginal microbiota stability (Mann-Whitney test p-value: 0.7270) (Figure 3). Similarly, there was no difference in stability from baseline to 6 months or 6 months to 12 months in women with Cu-IUDs and LNG-IUSs (Mann-Whitney test p-value: 0.2357and 0.3149, respectively) (data not shown).

Figure 3. Within subject θYC distances between vaginal microbiota at baseline and after 12 months of intrauterine contraceptive use.

θYC distances were based on OTUs (98% sequence similarity) of V4 region sequences of 16S rRNA genes. Orange represents subject with a Cu-IUD and green represents subjects with a LNG-IUS. Subjects were included only if their baseline and 12 months samples each yielded at least 3437 V4 region sequences (Cu-IUD: n=26, LNG-IUD: n=32). The lines indicate median θYC distances. There was no significant difference between the groups (Mann-Whitney p-value: 0.7270).

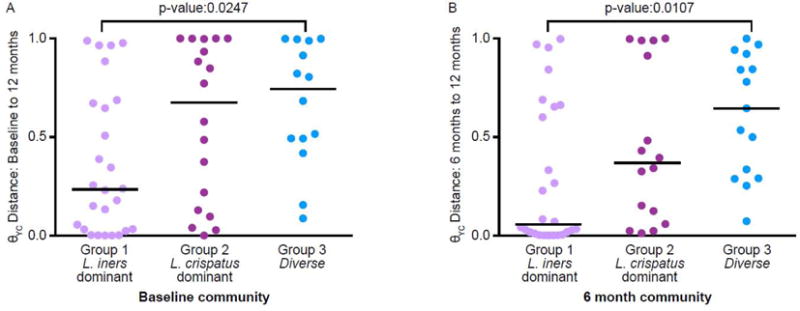

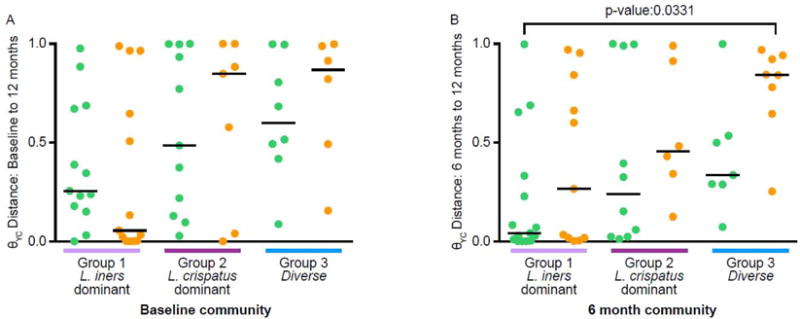

Communities dominated by L. iners were more stable than diverse communities

To determine if community composition affects community stability we compared within subject θYC distances over time by community group at the initial time point. The vaginal microbiota of women with L. iners-dominant (group 1) vaginal microbiota at baseline or 6 months was more stable than the vaginal microbiota of women with diverse (group 3) communities, with significantly smaller θYC distances between baseline and 12 months (Kruskal-Wallis test p-value: 0.0247) (Figure 4A) and between 6 months and 12 months (Kruskal-Wallis test p-value: 0.0107) (Figure 4B). The θYC distances between baseline and 6-month communities followed a similar trend, with the lowest median distance in women with L. iners-dominant (group 1) communities at baseline, but the difference was not statistically significant (Kruskal-Wallis test p-value: 0.1444) (data not shown).

Figure 4. Within subject θYC distances of the 3 vaginal community groups.

θYC distances were based on OTUs (98% sequence similarity) of V4 region sequences of 16S rRNA genes. A. Baseline to 12 months. Subjects were grouped based on baseline community group and were included only if their baseline and 12 months samples each yielded at least 3437 V4 region sequences (Group 1: n=26, Group 2: n=18, Group 3: n=14). Comparing all of the groups to each other indicated a significant difference (Kruskal-Wallis test p-value: 0.0247). A Dunn’s multiple comparisons posttest indicated a significant difference between only Group 1 and Group 3 (p-value: ≤0.05). B. 6 months to 12 months. Subjects were grouped based on their community group at 6 months and were included only if their 6 month and 12 month samples each yielded at least 3437 V4 region sequences (Group 1: n=26, Group 2: n=16, Group 3: n=15). Comparing all of the groups to each other indicated a significant difference (Kruskal-Wallis test p-value: 0.0107). A Dunn’s multiple comparisons posttest indicated a significant difference between only Group 1 and Group 3 (p-value: ≤0.05). P-values for groups that were significantly different by Dunn’s multiple comparison posttest of the Kruskal-Wallis test are shown. The lines indicate median θYC distances.

Although there were transitions between different community groups, most vaginal microbiotas remained in the same community group over time (Table 2). Consistent with the high stability of the vaginal microbiota of women with L. iners-dominant (group 1) vaginal microbiota based on θYC distances (Figure 4), 81.5% of vaginal microbiotas in group 1 at 6 months were also in group 1 at 12 months (Table 2).

Table 2.

Within-subject community group transitions

| A | 6 month: Group 1 | 6 month: Group 2 | 6 month: Group 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline: Group 1 | 64.5% | 16.1% | 19.4% |

| Baseline: Group 2 | 36.8% | 63.2% | 0.0% |

| Baseline: Group 3 | 23.8% | 9.5% | 66.7% |

| B | 12 month: Group 1 | 12 month: Group 2 | 12 month: Group 3 |

| 6 month: Group 1 | 81.5% | 11.1% | 7.4% |

| 6 month: Group 2 | 16.7% | 61.1% | 22.2% |

| 6 month: Group 3 | 37.5% | 0.0% | 62.5% |

Group 1=L. iners dominant communities, Group 2=L. crispatus dominant communities and Group 3=Non-Lactobaciilus dominant/diverse communities

After 6 months of acclimation to intrauterine contraception, L. iners-dominant vaginal microbiotas in LNG-IUS users are more stable than diverse microbiotas in Cu-IUD users

Finally, we wanted to test if there was a community composition-dependent effect of intrauterine contraception on the stability of the vaginal microbiota. When women were grouped by baseline community composition and type of intrauterine contraception, there were no significant differences in θYC distances from baseline to 12 months overall or using a pairwise comparison between contraceptive methods within a community group (Figure 5A). However, when women were grouped by their 6-month community composition and type of intrauterine contraception, the women with L. iners-dominant (group 1) communities at 6 months that were using LNG-IUSs had more stable vaginal bacterial communities over the next 6 months than women with diverse (group 3) communities using Cu-IUDs, with a significantly lower θYC distance between 6 month and 12 month communities (Kruskal-Wallis test p-value: 0.0331, Dunn’s multiple comparisons posttest between group 1, LNG-IUS and group 3, Cu-IUD P-value: ≤0.05) (Figure 5B). There were still no significant differences in 6 to 12 month θYC distances between contraceptive types within community groups. However, the difference in 6 to 12 month θYC distances between Cu-IUD and LNG-IUS users with diverse (group 3) communities at 6 months was approaching statistical significance (Mann-Whitney test p-value: 0.0932) so with more subjects, a statistically significant difference may be detected.

Figure 5. Within subject θYC distances by contraceptive method and vaginal community groups.

θYC distances were based on OTUs (98% sequence similarity) of V4 region sequences of 16S rRNA genes. A. Baseline to 12 months. Subjects were grouped based on baseline community group and were included only if their baseline and 12 month samples each yielded at least 3437 V4 region sequences (Group 1: LNG-IUS, n=13, Cu-IUD=13; Group 2: LNG-IUS, n=11, Cu-IUD=7; Group 3: LNG-IUS, n=8, Cu-IUD=6). There were no significant differences in θYC distances from baseline to 12 months comparing all of the samples (Kruskal-Wallis test p-value: 0.1535) or using a pairwise comparison between contraceptive methods within a community group (Mann-Whitney p-values: 0.3358 (Group 1), 0.8601 (Group 2) and 0.6620 (Group 3)). B. 6 months to 12 months. Subjects were grouped based on their community group at 6 months and were included only if their 6 month and 12 month samples each yielded at least 3437 V4 region sequences (Group 1: LNG-IUS, n=15, Cu-IUD=11; Group 2: LNG-IUS, n=10, Cu-IUD=6; Group 3: LNG-IUS, n=7, Cu-IUD=8). There were no significant differences in θYC distances from baseline to 12 months using a pairwise comparison between contraceptive method within a community group (Mann-Whitney p-values: 0.3302 (Group 1), 0.4278 (Group 2) and 0.0939 (Group 3). Comparing all of the groups to each other indicated a significant difference (Kruskal-Wallis test p-value: 0.0331). A Dunn’s multiple comparisons posttest indicated a significant difference between only Group 1: LNG-IUS and Group 3: Cu-IUD (p-value: ≤0.05). P-values for groups that were significantly different by Dunn’s multiple comparison posttest of the Kruskal-Wallis test are shown. The lines indicate median θYC distances. Green indicates LNG-IUS and orange indicates Cu-IUD.

Discussion

There is a clear knowledge gap concerning how IUDs affect the vaginal microbiota and, consequently, women’s health. In the United States, rates of intrauterine contraception use are increasing, reaching 10.3% of female contraception users in 2012 [31]. With new recommendations by the American Academy of Pediatrics and expanded insurance coverage with the Affordable Care Act, there is a potential for further increases in intrauterine contraceptive use in the United States [32, 33]. This issue also warrants global attention, particularly in areas with high HIV prevalence due to the potential effects of the vaginal microbiota on HIV transmission and acquisition [10–12]. Recent studies have suggested that depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) increases the risk of HIV acquisition and transmission [34–36]. This evidence has been regarded cautiously because the studies have important limitations and HIV risks associated with potential alternatives, including intrauterine contraception, are not well understood [35, 37, 38]. The possibility that hormonal contraceptives may alter HIV susceptibility warrants further investigation of potential mechanisms.

To begin filling this gap we studied the vaginal microbiota of women during their first year of intrauterine contraception use. Our study demonstrates that use of intrauterine contraception (Cu-IUD or LNG-IUS) was not associated with alterations in the overall composition of the vaginal microbiota over 12 months. Changes in the vaginal microbiota did occur between baseline, 6 months and 12 months but there is no evidence that these changes depend on the use of intrauterine contraception. A recent study of 11 Caucasian women reported minimal changes in the vaginal microbiota associated with LNG-IUS use but community composition data for individuals was not presented [39]. A significant increase in samples with L. crispatus relative abundance above 50% after LNG-IUS placement was observed [39]. Our sampling frequency may have missed changes that occurred on a shorter timescale (prior to 6 months). Another potential limitation of our study was the higher percentage of black LNG-IUS users compared to black Cu-IUD users (Table 1). This difference, while not statistically significant in our relatively small study, may be important given the links between race and vaginal microbiota composition [8, 9,15].

Additionally, we observe increased stability in the L. iners-dominant (group 1) communities compared to diverse (group 3) communities irrespective of contraceptive type. The high stability of L. iners-dominant communities agrees with Gajer et al. [17]. Within community groups, there were no significant differences in community stability between Cu-IUD and LNG-IUS users. However, there may be a trend towards higher community stability with LNG-IUS use. Interestingly, when subjects were grouped by 6-month community group and type of contraception, the only statistically significant difference in stability between 6 and 12 months was between L. iners-dominant (group1) communities with LNG-IUSs and diverse (group 3) communities with Cu-IUDs (Figure 5B). This comparison, after 6 months of acclimation to intrauterine contraception, may represent 2 extremes in stability: the highly stable L. iners dominant (group 1) communities with an LNG-IUS and the highly dynamic diverse (group 3) communities with a Cu-IUD (Figure 5B). L. iners does have the ability to use mucus as a growth substrate, so perhaps the thicker cervical mucus produced by LNG-IUS users promotes L. iners growth, making a dramatic shift in community composition unlikely [40]. Future studies with more subjects will be needed to clarify the effects of intrauterine contraception on the stability of specific vaginal microbiota compositions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the study subjects; the Microbial Systems Molecular Biology Lab of the Host Microbiome Initiative at the University of Michigan and Susan Foltin for sequencing; and Anna Seekatz and Robert Hein for help with R. This research was supported in part through computational resources and services provided by Advanced Research Computing at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health [Award Number UL1TR000433] and the National Institutes of Health [Grant Number R03HD077909].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in Unintended Pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;374:843–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1506575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception. 2011;83:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calzolari E, Masciangelo R, Milite V, Verteramo R. Bacterial vaginosis and contraceptive methods. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2000;70:341–6. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(00)00217-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shoubnikova M, Hellberg D, Nilsson S, Mårdh P-A. Contraceptive use in women with bacterial vaginosis. Contraception. 1997;55:355–8. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(97)00044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Madden T, Grentzer JM, Secura GM, Allsworth JE, Peipert JF. Risk of bacterial vaginosis in users of the intrauterine device: a longitudinal study. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2012;39:217–22. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31823e68fe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Hanlon D, Moench T, Cone R. In vaginal fluid, bacteria associated with bacterial vaginosis can be suppressed with lactic acid but not hydrogen peroxide. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2011;11:200. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Hanlon DE, Moench TR, Cone RA. Vaginal pH and Microbicidal Lactic Acid When Lactobacilli Dominate the Microbiota. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e80074. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ravel J, Gajer P, Abdo Z, et al. Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108:4680–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002611107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anahtar Melis N, Byrne Elizabeth H, Doherty Kathleen E, et al. Cervicovaginal Bacteria Are a Major Modulator of Host Inflammatory Responses in the Female Genital Tract. Immunity. 2015;42:965–76. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borgdorff H, Tsivtsivadze E, Verhelst R, et al. Lactobacillus-dominated cervicovaginal microbiota associated with reduced HIV/STI prevalence and genital HIV viral load in African women. ISME J. 2014;8:1781–93. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cone RA. Vaginal Microbiota and Sexually Transmitted Infections That May Influence Transmission of Cell-Associated HIV. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2014;210:S616–S21. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin HL, Richardson BA, Nyange PM, et al. Vaginal Lactobacilli, Microbial Flora, and Risk of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 and Sexually Transmitted Disease Acquisition. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1999;180:1863–8. doi: 10.1086/315127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiesenfeld HC, Hillier SL, Krohn MA, Landers DV, Sweet RL. Bacterial Vaginosis Is a Strong Predictor of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis Infection. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2003;36:663–8. doi: 10.1086/367658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Veer C, Bruisten S, van der Helm J, de Vries H, van Houdt R. The cervicovaginal microbiota in women notified for Chlamydia trachomatis infection: A case-control study at the STI outpatient clinic in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2016 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou X, Brown CJ, Abdo Z, et al. Differences in the composition of vaginal microbial communities found in healthy Caucasian and black women. ISME J. 2007;1:121–33. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2007.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fettweis JM, Brooks JP, Serrano MG, et al. Differences in vaginal microbiome in African American women versus women of European ancestry. Microbiology. 2014;160:2272–82. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.081034-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gajer P, Brotman RM, Bai G, et al. Temporal Dynamics of the Human Vaginal Microbiota. Science Translational Medicine. 2012;4:132ra52–ra52. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis RA, Taylor D, Natavio MF, Melamed A, Felix J, Mishell D., Jr Effects of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system on cervical mucus quality and sperm penetrability. Contraception. 82:491–6. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Secura GM, Allsworth JE, Madden T, Mullersman JL, Peipert JF. The Contraceptive CHOICE Project: reducing barriers to long-acting reversible contraception. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2010;203:115.e1–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forney LJ, Gajer P, Williams CJ, et al. Comparison of Self-Collected and Physician-Collected Vaginal Swabs for Microbiome Analysis. Journal Of Clinical Microbiology. 2010;48:1741–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01710-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kozich JJ, Westcott SL, Baxter NT, Highlander SK, Schloss PD. Development of a Dual-Index Sequencing Strategy and Curation Pipeline for Analyzing Amplicon Sequence Data on the MiSeq Illumina Sequencing Platform. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2013;79:5112–20. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01043-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seekatz AM, Theriot CM, Molloy CT, Wozniak KL, Bergin IL, Young VB. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Eliminates Clostridium difficile in a Murine Model of Relapsing Disease. Infection and Immunity. 2015;83:3838–46. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00459-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, et al. Introducing mothur: Open-Source, Platform-Independent, Community-Supported Software for Describing and Comparing Microbial Communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:7537–41. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01541-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hartman A, Riddle S, McPhillips T, Ludaescher B, Eisen J. WATERS: a Workflow for the Alignment, Taxonomy, and Ecology of Ribosomal Sequences %U. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:317. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-317. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2105/11/317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schloss PD. A High-Throughput DNA Sequence Aligner for Microbial Ecology Studies. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e8230. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pruesse E, Quast C, Knittel K, et al. SILVA: a comprehensive online resource for quality checked and aligned ribosomal RNA sequence data compatible with ARB. Nucl Acids Res. 2007;35:7188–96. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schloss PD, Westcott SL. Assessing and Improving Methods Used in Operational Taxonomic Unit-Based Approaches for 16S rRNA Gene Sequence Analysis. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2011;77:3219–26. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02810-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Westcott SL, Schloss PD. De novo clustering methods outperform reference-based methods for assigning 16S rRNA gene sequences to operational taxonomic units. PeerJ. 2015;3:e1487. doi: 10.7717/peerj.1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yue JC, Clayton MK. A similarity measure based on species proportions. Commun Stat-Theory Methods. 2005;34:2123–31. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderson MJ. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecology. 2001;26:32–46. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kavanaugh ML, Jerman J, Finer LB. Changes in Use of Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptive Methods Among U.S. Women, 2009–2012. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:917–27. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. United States: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 33.ADOLESCENCE CO. Contraception for Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e1244–e56. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heffron R, Donnell D, Rees H, et al. Hormonal contraceptive use and risk of HIV-1 transmission: a prospective cohort analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2012;12:19–26. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70247-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Polis CB, Phillips SJ, Hillier SL, Achilles SL. Levonorgestrel in contraceptives and multipurpose prevention technologies: does this progestin increase HIV risk or interact with antiretrovirals? AIDS (London, England) 2016 doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noguchi LM, Richardson BA, Baeten JM, et al. Risk of HIV-1 acquisition among women who use different types of injectable progestin contraception in South Africa: a prospective cohort study. The lancet HIV. 2015;2:e279–e87. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(15)00058-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wawer MJ, Gray RH. Challenges in assessing associations between hormonal contraceptive use and the risks of HIV-1 acquisition and transmission. Future microbiology. 2012;7:315–8. doi: 10.2217/fmb.12.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Polis CB, Westreich D, Balkus JE, Heffron R. Assessing the effect of hormonal contraception on HIV acquisition in observational data: challenges and recommended analytic approaches. AIDS (London, England) 2013;27(Suppl 1):S35–43. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jacobson JC, Turok DK, Dermish AI, Nygaard IE, Settles ML. Vaginal microbiome changes with levonorgestrel intrauterine system placement. Contraception. 2014;90:130–5. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Macklaim JM, Gloor GB, Anukam KC, Cribby S, Reid G. At the crossroads of vaginal health and disease, the genome sequence of Lactobacillus iners AB-1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108:4688–95. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000086107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.