Abstract

Objectives

To investigate factors predicting the onset of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) after primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI) for patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).

Background

Apelin-12 plays an essential role in cardiovascular homoeostasis. However, current knowledge of its predictive prognostic value is limited.

Methods

464 patients with STEMI (63.0±11.9 years, 355 men) who underwent successful pPCI were enrolled and followed for 2.5 years. Multivariate cox regression analysis and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis were performed to determine the factors predicting MACEs.

Results

118 patients (25.4%) experienced MACEs in the follow-up period. Multivariate cox regression analysis found low apelin-12 (HR=0.132, 95% CI 0.060 to 0.292, P<0.001), low left ventricular ejection fraction (HR=0.965, 95% CI 0.941 to 0.991, P=0.007), low estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) (HR=0.985, 95% CI 0.977 to 0.993, P<0.001), Killip’s classification>I (HR=0.610, 95% CI 0.408 to 0.912, P=0.016) and pathological Q-wave (HR=1.536, 95% CI 1.058 to 2.230, P=0.024) were independent predictors of MACEs in the 2.5 year follow-up period. Low apelin-12 also predicted poorer in-hospital prognosis and MACEs in the 2.5 years follow-up period compared with Δapelin-12 (P=0.0115) and eGFR (P=0.0071) among patients with eGFR>90 mL/min×1.73 m2. Further analysis showed Δapelin-12 <20% was associated with MACEs in patients whose apelin-12 was below 0.76 ng/mL (P=0.0075) on admission.

Conclusions

Patients with STEMI receiving pPCI with lower apelin-12 are more likely to suffer MACEs in hospital and 2.5 years postprocedure, particularly in those with normal eGFR levels.

Keywords: adult cardiology, ischaemic heart disease, clinical trials

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Only patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) receiving successful primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI) and defined Δapelin-12 with apelin-12 elevation per cent 72 hours after pPCI compared with apelin-12 level immediately prior to pPCI were enrolled.

The prognosis value of apelin-12 in predicting short-term (during hospitalisation) and long-term (2.5 years) major adverse cardiovascular events, respectively, was analysed among patients with estimated glomerular filtration rate exceeding and below 90 mL/min×1.73m2.

The relatively small cohort size may affect the statistical results; therefore, a larger-scale study is warranted.

The basic level of apelin prior to STEMI onset is difficult to measure; therefore, the degree of reduction in apelin is unknown.

This study focuses only on apelin-12, and the analysis of other forms of apelin is suggested.

Introduction

ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) following successful primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI) is the leading cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide in major adverse coronary events (MACEs) due to mechanical complications, acute heart failure and cardiac shock after successful procedure.1 Structural and functional alterations lead to progressive worsening of cardiac performance. The prognosis of STEMI following pPCI is influenced by several clinical, biochemical and echocardiographic factors. Novel, more reliable biomarkers are urgently needed to precisely identify patients at high risk for adverse clinical outcomes in the follow-up period after pPCI and to aid in the development of individualised prevention programme.2 3

Apelin, a 77-amino acid peptide is the endogenous ligand for the human orphan G protein-coupled receptor (APJ) and is secreted by white adipose tissue. It is expressed in various cardiovascular tissues, including endothelial cells, coronary vessels, vascular smooth muscle cells and cardiomyocytes.4 The apelin–APJ system plays a role in cardiovascular homoeostasis.5 Apelin-12 may employ its cardioprotective profile via the complex mechanism of improving hypertension, insulin resistance, obesity and cardiovascular risk factors.6–8 However, the use of serum apelin-12 level on admission in providing additional prognostic information among patients with STEMI receiving pPCI remains unknown. There is limited evidence examining the involvement of apelin in STEMI and some research suggests it has no prognostic value,9–11 and one study found an inverse correlation between the level of apelin-12 and prognosis.12 These results highlight the need for additional research.

This study aims to determine the ability of plasma apelin-12 levels to predict short-term and long-term MACEs in patients with STEMI following successful pPCI. Furthermore, the combined use of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is examined.

Methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria and definition of MACEs

Patients were enrolled in the study if they presented with the onset of symptoms of STEMI at the First People’s Hospital of Taizhou, Zhejiang, China between January 2010 and October 2014. STEMI symptoms included: persistent chest pain (>30 min), prolonged ECG changes (including ischaemic ST-segment elevation in two or more contiguous leads and/or depression) and significantly increased serum myocardial enzyme and troponin concentrations. Written informed consent was obtained, and the Research Ethics Committee of The First People’s Hospital of Taizhou approved the study.

Exclusion criteria included non-STEMI; severe vascular heart disease; balloon angioplasty alone; rescue PCI; conservative treatment without PCI; previous onset of ventricular fibrillation; cardiogenic shock; untreated third or advanced degree of atrioventricular block; estimated life expectancy <12 months; secondary hypertension; endocrine diseases such as thyroid dysfunction or adrenal cortical dysfunction; history of cerebrovascular attack (within 1 year) or cerebrovascular attack with a significant residual neurological deficit; a history of chronic hepatitis or cirrhosis; severe renal insufficiency needing dialysis; known contraindication to statins, heparin, aspirin, clopidogrel, contrast or glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor (GPI); recent serious infection, connective tissue disease; malignancy; active severe bleeding; significant gastrointestinal or genitourinary bleeding; major surgery or trauma within 6 weeks and incomplete clinical data.

Important definitions

A MACE is defined as the composite of cardiac death, recurrent target vessel myocardial infarction (RMI); clinically driven target lesion revascularisation (TLR); cardiogenic shock or demonstrated congestive heart failure. The eGFR was estimated using the simplified Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula.13 Δapelin-12 was defined as the level of apelin-12 elevation 72 hours after pPCI compared with apelin-12 level immediately before pPCI.

Therapy process

A total of 464 patients underwent successful pPCI all of whom were diagnosed with STEMI and admitted to emergency room within 12 hours from onset. All patients received 300 mg oral aspirin and clopidogrel as well as standard heparin (initial 10 000 IU and boost during surgery), patients with high thrombotic burden use the GPI (uniformly tirofiban in our centre), which was determined by our interventional physician. Ultrasound scans were taken within 5 days after PCI (median 4.2 days). The parameters of two-dimensional echocardiography and Doppler were measured using standard methods (ie, using biplane Simpson’s method for measuring left ventricular volumes and ejection fraction). Volumes were expressed as indices by normalising with body surface area.

All the patients received 30-month follow-up after pPCI until MACEs. A small number of patients suffered MACEs requiring hospitalisation. Patients were organised into MACEs group and non-MACEs group and independent predictors of poor prognosis were identified. The following biochemical indicators were measured: blood (including haemoglobin, neutrophil per cent, haemoglobin and platelet), coagulation, D-dimer, renal and hepatic function, ∆apelin-12, peak myocardial enzyme, lipid level and fast blood glucose on the second day. Patients were further stratified into two subgroups according to the median value of apelin-12 level on admission and into three further subgroups according to tertiles of eGFR.

Apelin-12 ELISA detection

Serum was isolated by centrifugation within 1 hour at 2500 g for 10 min and stored at −80°C. Serum concentrations of apelin-12 were assayed using commercially available enzyme immunoassay kits (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Belmont, California, USA). The protocol was as follows: add 50 µL/well of standard, sample or positive control, 25 µL of primary antibody and 25 µL of biotinylated peptide; incubate at room temperature (20–23°C) for 2 hours; wash immunoplate four times with 350 µL/well of 1×assay buffer; add 100 µL/well of Streptavidin horse radish peroxidase-solution and incubate at room temperature for 1 hour. Wash immunoplate four times with 350 µL/well of 1×assay buffer. Add 100 µL/well of 3,3′, 5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine substrate solution and incubate at room temperature for 1 hour. Terminate reaction with 100 µL/well of 2N HCl. The detection limit was 0.1 mg/L, with 1.26% and 5.4% intra-assay and interassay coefficients of variation, respectively. The measurements were performed in triplicates.

Statistical strategy

Continuous data were presented as mean ± SD or medians with interquartile ranges, whereas categorical data were presented as a percentage, unless otherwise denoted. Univariate cox analysis and log-rank test were used for qualitative and quantitative variables to determine whether there is significant difference between the MACE and non-MACE groups. Variables with P<0.1 in the above analysis were selected for the multivariate cox proportional hazard analysis. The adjusted HR and 95% CI were calculated. The log-rank test was used to compare Kaplan-Meier curves of MACE-free survival in the two groups, divided by the median apelin-12. Finally, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to identify the appropriate cut-off value of potential predictive indicators. The cut-off point was the maximum sum of sensitivity and specificity. The ROC curves were conducted with the Medcalc V.12.3.0.0. All statistical tests were two tailed, performed using SPSS V.17.0, and a P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics of patients in individual groups

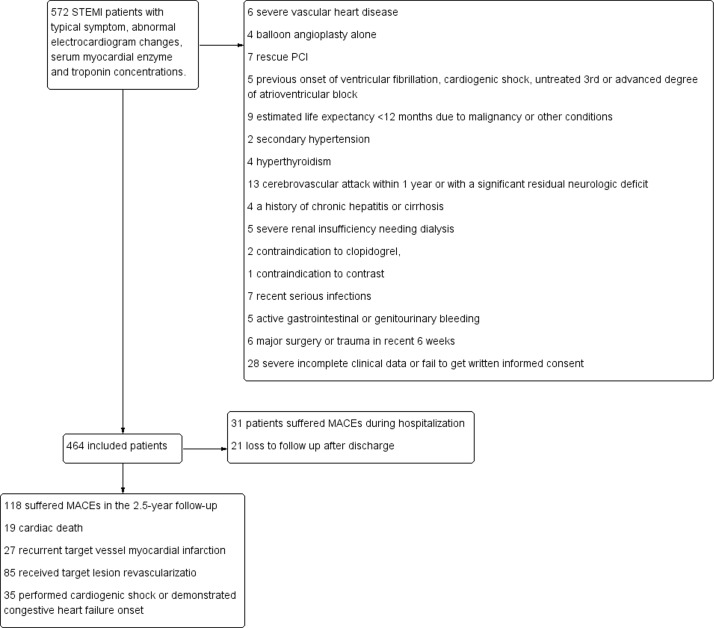

Of the 464 enrolled patients, 118 (25.4%) had MACEs in the 2.5-year follow-up. Nineteen (4.1%) patients suffered cardiac death, while 27 (5.8%) suffered RMI; 85 (18.3%) received TLR due to RMI or progressive stenosis. Thirty-five (7.5%) performed cardiogenic shock or demonstrated congestive heart failure onset. Among the MACEs group, 31 (6.7%) patients reached end point during hospitalisation. Twenty-one (4.5%) patients lost to follow-up after discharge (figure 1). Basic clinical characteristics, laboratory examinations, ECG results, angiographic and procedural characteristics are depicted in table 1.

Figure 1.

Patients selecting process and results reported. MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Table 1.

Basic clinical characteristics, laboratory examinations, ECG results, angiographic and procedural characteristic

| MACEs (n=118) | Non-MACEs (n=346) | P Value | |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Age, years | 67.0±12.2 | 61.7±11.6 | 0.252 |

| Female, n (%) | 33 (28.0) | 76 (22.0) | 0.184 |

| Heart rate, beats per min | 79.5±19.5 | 76.1±16.6 | 0.118 |

| SBP, mm Hg | 132.2±26.6 | 131.6±25.0 | 0.277 |

| Anterior wall MI, n (%) | 72 (61.0) | 159 (46.0) | 0.005* |

| Killip’s classification>I, n (%) | 41 (34.7) | 71 (20.5) | 0.002* |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 41 (34.7) | 109 (31.5) | 0.515 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 72 (61.0) | 193 (55.8) | 0.321 |

| Previous MI, n (%) | 19 (16.1) | 36 (10.4) | 0.098 |

| Lab examination | |||

| Apelin-12, ng/mL | 0.69 (0.53–0.87) | 0.79 (0.63–1.03) | <0.001* |

| Δapelin-12 (%) | 13.9 (5.6–17.6) | 14.7 (5.3–22.3) | 0.092 |

| WBC×109/L | 10.6±3.86 | 9.86±3.58 | 0.161 |

| Neutrophil (%) | 76.8±12.6 | 74.9±12.4 | 0.064 |

| Haemoglobin, g/L | 139.4±16.7 | 145.3±17.1 | 0.546 |

| Platelet×109/L | 240.2±60.1 | 227.8±57.2 | 0.264 |

| Albumin, g/L | 37.9±3.9 | 38.0±3.8 | 0.424 |

| TC, mmol/L | 5.87±0.99 | 5.57±1.17 | 0.469 |

| TG, mmol/L | 1.06±0.65 | 1.12±0.90 | 0.261 |

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 1.25±0.28 | 1.18±0.27 | 0.982 |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 3.07±0.72 | 3.03±0.73 | 0.744 |

| FBG, mmol/L | 7.67±2.68 | 7.66±2.48 | 0.207 |

| BUN, mmol/L | 6.78±1.88 | 6.72±2.14 | 0.387 |

| Creatinine, mmol/L | 76.3±15.6 | 74.1±21.7 | 0.392 |

| Uric acid, mmol/L | 333.3±80.7 | 338.5±72.9 | 0.153 |

| eGFR mL/min*1.73 m2 | 89.7±25.8 | 100.6±25.9 | 0.067 |

| D-Dimer, mg/L | 0.7 (0.2–1.6) | 1.0 (0.2–1.7) | 0.247 |

| Peak CK-MB, U/L | 131.5 (51.6–208.5) | 103.0 (39.3–193.4) | 0.252 |

| Peak cTnI, ng/mL | 21.5 (9.3–32.4) | 12.6 (3.0–28.8) | 0.014* |

| Treatment | |||

| ACEIs/ARBs, n (%) | 94 (79.7) | 294 (85.0) | 0.178 |

| b-blocker, n (%) | 65 (55.1) | 211 (61.0) | 0.260 |

| CCBs, n (%) | 29 (24.6) | 101 (29.2) | 0.335 |

| Statins, n (%) | 97 (82.2) | 288 (83.2) | 0.796 |

| Diuretics, n (%) | 19 (16.1) | 55 (15.9) | 0.958 |

| tirofiban, n (%) | 15 (12.7) | 52 (15.0) | 0.536 |

| Echocardiogram and ECG | |||

| LAD, mm | 38.5±5.3 | 37.0±5.7 | 0.311 |

| LVEDD, mm | 52.0±6.4 | 49.9±6.1 | 0.273 |

| LVEF, % | 47.3±9.4 | 51.9±7.3 | 0.010* |

| Pathological Q-wave, n (%) | 70 (59.3) | 153 (44.2) | 0.005* |

| GENSINI | 85.0 (48.8–100.1) | 66.9 (37.2–101.7) | 0.129 |

| Culprit vessels, n (%) | |||

| LAD | 64 (54.2) | 169 (48.8) | 0.557 |

| LCX | 18 (15.3) | 54 (15.6) | |

| RCA | 36 (30.5) | 123 (35.5) | |

| Stent number | 1.33±0.55 | 1.39±0.57 | 0.524 |

Data are n/N (%) or mean ±SD or median (25th–75th percentile).

*P<0.05.

ACEIs, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CCBs, calcium channel blockers; CK-MB, creatine kinase MB; cTnI, cardiac troponin I; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FBG, fasting blood glucose; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein; LAD, left atrial diameter; LCX, left circumflex coronary artery; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; LVEDD, left ventricular and diastolic diameter; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MACEs, major adverse cardiovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction; RCA, right coronary artery; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyeride; WBC, white blood cells.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of predictor of MACEs

Significant differences were found between the two groups in peak cardiac troponin I (cTnI) (21.5 (9.3–32.4) vs 12.6 (3.0–28.8), P=0.014) and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (47.3%±9.4% vs 51.9%±7.3%, P=0.010). Consistent with the hypothesis, patients who suffered from MACEs had lower apelin-12 on admission (0.69 (0.53–0.87) vs 0.79 (0.63–1.03), P<0.001). Anterior wall MI, pathological Q-wave and higher Killip’s classification were found more in the MACEs group compared with survivals (P=0.005, 0.005 and 0.002, respectively). Differences in Δapelin-12 (13.9 (5.6–17.6) vs 14.7 (5.3–22.3), P=0.092), neutrophil per cent (76.8±12.6 vs 74.9±12.4, P=0.064), eGFR (89.7±25.8 vs 100.6±25.9, P=0.067) and previous MI proportion (16.1% vs 10.4%, P=0.098) were approaching significance between the two groups.

Through the multivariate cox regression analysis, low apelin-12 (HR=0.132, 95% CI 0.060 to 0.292, P<0.001), low eGFR (HR=0.985, 95% CI 0.977 to 0.993, P<0.001), low LVEF (HR=0.965, 95% CI 0.941 to 0.991, P=0.007) and pathological Q-wave (HR=1.536, 95% CI 1.058 to 2.230, P=0.024) were independent predictors of MACEs within 2.5 years after pPCI, along with Killip’s classification>I (HR=0.610, 95% CI 0.408 to 0.912, P=0.016). Anterior wall MI was moderately predictive of MACEs within 2.5 years (HR=1.421, 95% CI 0.970 to 2.082, P=0.071) (table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate cox regression analysis for predictor of MACEs

| Variables | P value | OR | 95% CI |

| Anterior wall MI | 0.071 | 1.421 | 0.970 to 2.082 |

| Previous MI | 0.708 | 1.107 | 0.650 to 1.884 |

| Apelin-12 | <0.001* | 0.132 | 0.060 to 0.292 |

| Δapelin-12 (%) | 0.411 | 0.991 | 0.970 to 1.012 |

| Neutrophil (%) | 0.186 | 1.011 | 0.995 to 1.027 |

| eGFR | <0.001* | 0.985 | 0.977 to 0.993 |

| cTnI | 0.203 | 1.017 | 0.991 to 1.044 |

| LVEF | 0.007* | 0.965 | 0.941 to 0.991 |

| Pathological Q-wave | 0.024* | 1.536 | 1.058 to 2.230 |

| Killip’s classification>I | 0.016 | 0.610 | 0.408 to 0.912 |

*Statistically significant value (<0.05).

cTnI, cardiac troponin I; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MACEs, major adverse cardiovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction.

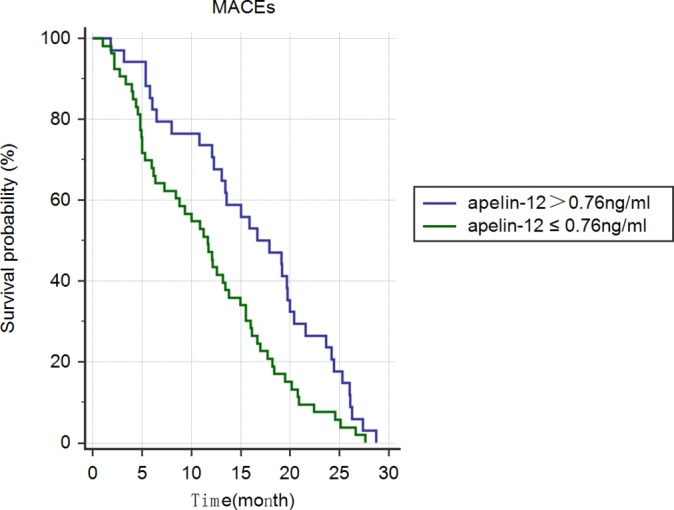

Survival analysis

Kaplan-Meier curves in patients with higher (>0.76 ng/mL, n=229) and lower (<0.76 ng/mL, n=235) apelin-12 during 2.5-year follow-up (without MACEs during hospitalisation) is shown in figure 2. Significant differences in event-free survival were noted between patients with differing apelin-12 on admission (P=0.018).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves in patients with STEMI with individual levels of apelin-12 during 2.5 years of follow-up (without MACEs during hospitalisation). MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

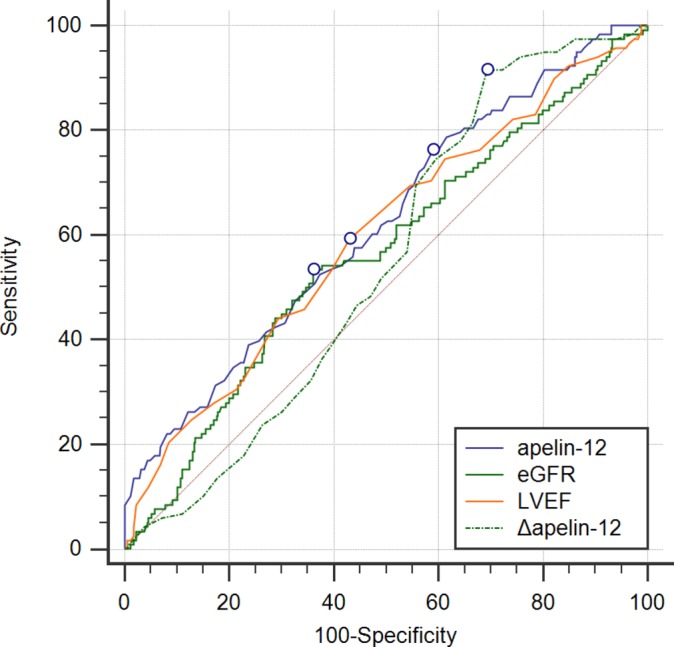

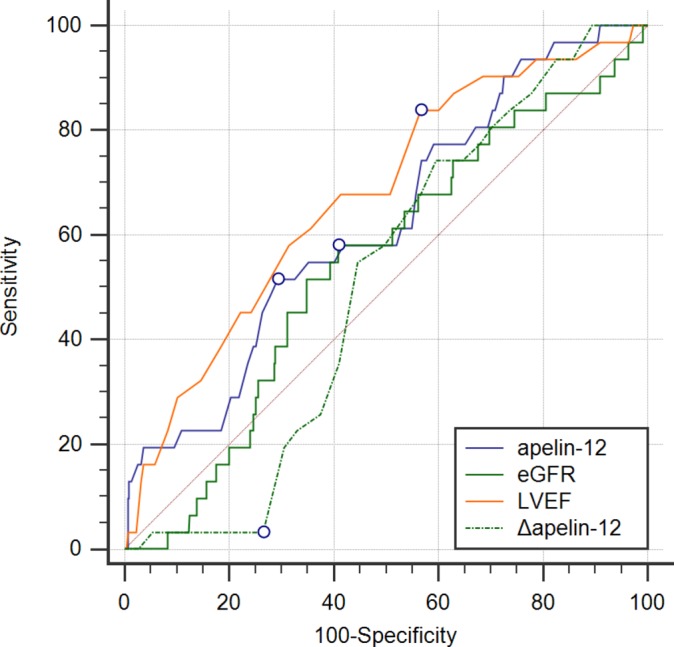

ROC analysis of predictor of MACEs

ROC analysis failed to find the area under curve (AUC) of any indicator for 2.5-year MACEs exceeding 0.7, although the P value for apelin-12, eGFR and LVEF alone was 0.0001, 0.0369 and 0.0015, respectively, while the AUC of Δapelin-12 for 2.5-year MACEs was 0.547 (95% CI 0.500 to 0.593, P=0.0906, figure 3). When only in-hospital MACEs were observed, there was no evidence of predictive value except for LVEF<52% (AUC=0.674, 95% CI 0.629 to 0.716, P=0.0005) and apelin-12 ≤0.64 ng/mL (AUC=0.623, 95% CI 0.577 to 0.667, P=0.0169, figure 4 and table 3). ROC analysis ofΔapelin-12 found a higher AUC with a cut-off point of 20% only for those with apelin-12 on admission ≤0.76 ng/mL (P=0.0075, table 3).

Figure 3.

Receiver operating characteristic curve of apelin-12, eGFR, LVEF and Δapelin-12 for predicting 2.5 year MACEs after pPCI among patients with STEMI. eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MACEs, major adverse cardiovascular events; pPCI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Figure 4.

Receiver operating characteristic curve of apelin-12, eGFR, LVEF and Δapelin-12 for predicting in-hospital MACEs after pPCI among patients with STEMI. eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MACEs, major adverse cardiovascular events; pPCI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Table 3.

ROC analysis for in-hospital and 2.5-year MACEs

| Parameters | AUC | 95% CI | P Value | Threshold | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % |

| 2.5-year MACEs | ||||||

| Δapelin-12 | 0.547 | 0.500 to 0.593 | 0.0906 | 20% | 91.53 | 30.64 |

| apelin-12 | 0.619 | 0.573 to 0.663 | 0.0001* | 0.87 | 75.36 | 42.03 |

| eGFR | 0.565 | 0.518 to 0.611 | 0.0369* | 86.13 | 53.39 | 63.87 |

| LVEF | 0.597 | 0.551 to 0.642 | 0.0015* | 50% | 59.32 | 56.94 |

| Apelin-12>0.76 ng/mL | ||||||

| Δapelin-12 | 0.530 | 0.454 to 0.605 | 0.4767 | 17% | 92.31 | 39.81 |

| Apelin-12≤0.76 ng/mL | ||||||

| Δapelin-12 | 0.613 | 0.547 to 0.675 | 0.0075* | 20% | 100.00 | 30.77 |

| In-hospital MACEs | ||||||

| Δapelin-12 | 0.507 | 0.460 to 0.553 | 0.8711 | 20% | 3.23 | 73.44 |

| apelin-12 | 0.623 | 0.577 to 0.667 | 0.0169* | 0.64 | 51.61 | 70.67 |

| eGFR | 0.543 | 0.497 to 0.589 | 0.4021 | 86.98 | 58.06 | 59.12 |

| LVEF | 0.674 | 0.629 to 0.716 | 0.0005* | 52% | 83.87 | 43.42 |

*Statistically significant value (P<0.05).

AUC, area under curves; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MACEs, major adverse cardiovascular events; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

When patients were further subdivided according to eGFR, it was found that 224 patients with eGFR were over 90 mL/min×1.73 m2. Among these patients, apelin-12 had a predictive advantage for MACEs compared with Δapelin-12 (P=0.0115) and eGFR (P=0.0071). Moreover, LVEF was only predictive in patients with eGFR>90 mL/min×1.73 m2 (AUC=0.628, 95% CI 0.564 to 0.689, P=0.0039, table 4), in other words, among patients with eGFR over 90 mL/min×1.73 m2, apelin-12 perform the most ideal prognostic factor.

Table 4.

ROC analysis for 2.5-year MACEs among patients with separate level of renal function

| Parameters | AUC | 95% CI | P value | Threshold | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % |

| eGFR>90 mL/min×1.73 m2 (n=244) | ||||||

| Δapelin-12 | 0.524 | 0.459 to 0.588 | 0.5556 | 20% | 90.57 | 29.84 |

| apelin-12 | 0.664 | 0.601 to 0.723 | 0.0001* | 0.65 | 66.04 | 58.12 |

| eGFR | 0.508 | 0.443 to 0.572 | 0.8634 | 91.67 | 100 | 7.33 |

| LVEF | 0.628 | 0.564 to 0.689 | 0.0039* | 50% | 62.26 | 61.78 |

| eGFR<90 mL/min×1.73 m2 (n=220) | ||||||

| Δapelin-12 | 0.566 | 0.498 to 0.633 | 0.0885 | 20% | 92.31 | 31.61 |

| apelin-12 | 0.654 | 0.587 to 0.716 | 0.0001* | 0.89 | 67.69 | 60.65 |

| eGFR | 0.562 | 0.494 to 0.629 | 0.1186 | 86.13 | 96.92 | 19.35 |

| LVEF | 0.561 | 0.492 to 0.627 | 0.1651 | 51% | 63.08 | 48.39 |

*Statistically significant value compared with apelin-12 (P<0.05).

AUC, area under curves; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MACEs, major adverse cardiovascular events; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

Discussion

The clinical outcomes in patients with STEMI receiving pPCI are closely associated with the pre-PCI apelin-12 concentration, particularly among those with normal renal function. In further subgroup analysis, the change of apelin during hospitalisation was found to predict long-term prognosis among patients with low apelin level on admission (apelin-12 ≤0.76 ng/mL).

Apelin may then play a role in assessing risk stratification among patients with STEMI given its role in the pathophysiology of both heart failure and ischaemia/reperfusion injury.14 Apelin has been found to increase contractility and reduce peripheral resistance via endothelial nitric oxide (NO)-dependent signalling15 in failing myocardial cells to slow the pathological progress of heart failure.16 Apelin expression has been found to decline in decompensated states, whereas it is maintained or augmented in stable chronic heart failure.17

In patients with stable angina, plasma apelin was negatively associated with coronary artery stenosis severity independent of other cardiovascular risk factors.18 Weir and colleagues demonstrated plasma apelin level is reduced immediately after acute myocardial infarction but increases markedly after revascularisation. Despite this, it remains depressed at 24 weeks.19 A potential explanation of lower levels of apelin following STEMI include: (1) the demand of apelin among patients with STEMI increases; therefore, more apelin is consumed immediately after MI episodes; (2) product plunging due to MI. A recent study demonstrated the flow-mediated adjustment of the apelin/APJ system in human endothelial cells and found apelin-12 expression is induced by shear stress independently of its ligand, particularly during reperfusion.20 Further, hypoxia-inducible factor-mediated pathways participate in the apelin upregulation in myocardium, pulmonary circulation and skeletal muscles following systemic hypoxic exposure or myocardial injury.21 Therefore, the apelin–APJ system may alleviate the myocardial reperfusion mediated oxidative stress and apoptosis by increasing superoxide dismutase degradation, thereby decreasing the generation of reactive oxygen species, along with upregulating endothelial constitutive nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) levels and activating ERK1/2 phosphorylation signalling.22 The above results may be responsible for the poor short-term outcomes and long-term prognosis observed in patients with low levels of apelin.

Apelin can provide myocardial protection against ischaemic damage by decreasing permeability of microvascular endothelial cells via upregulating the expression of Tie-2 and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2),23 and improving neovascularisation via recruiting circulating Aplnr +cells during early-phase myocardial repair.24 The Apelin–APJ system promotes angiogenesis and provides nutrients and oxygen to the ischaemic area in MI animal models.25 Apelin gene therapy by myocardial injection ameliorates cardiac repair, improves cardiac metabolism via activating Sirt3 and upregulating VEGF/VEGFR2 expression in post-MI mice.26 27 Conversely, apelin downregulation exacerbates ischaemia–reperfusion injury and myocardial infarction adverse remodelling.25 A recently published study proved apelin 12 is able to protect prothrombotic effects of other adipokine such as apelin-13.28 Apelin protects against angiotensin II-induced cardiovascular fibrosis and decreases plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 production.29 The use rate of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and β-blockers was similar among patients with different prognosis in the present study, eliminating the drug-derived influence on angiotensin activity. Myeloid cell-derived leucine-rich α2-glycoprotein attenuates adverse cardiac remodelling after MI via upregulating the expression of apelin receptor.30 Direct anti-inflammatory31 and antiatherogenic properties32 are also reported as mechanisms of atherosclerotic lesions and aortic aneurysms prevention by apelin. Stress-induced apoptosis in serious cardiovascular diseases is inhibited by cardiac apelin expression elevation.33 TIMP3 maintains metabolic flexibility via apelin during cardiac stress seizure.34 Taken together, the above cardiovascular profile suggests a beneficial effect of apelin on atherosclerosis and makes apelin–APJ system a promising therapeutic target in acute coronary syndrome.35

Liu and colleagues36 have demonstrated the effect of serum apelin-12 in predicting 1 year outcomes following pPCI in patients with STEMI. Topuz and colleagues37 found lower levels of serum apelin-12 predicts higher incidence of in-hospital MACEs after multivariate regression analysis and is more likely in no-reflow versus normal flow group. This is a result of NO-dependent vasodilatation caused by apelin-12 in clinical studies38 as well as in animal models.39 Abnormal level of apelin and a series of adipokines observed in patients with acute MI resulted in a high incidence of MACEs during 3-year follow-up.40 Low apelin appears to correlate with carotid plaque vulnerability in patients with carotid stenosis. Atorvastatin-induced apelin modification may beneficially affect carotid plaque stability.41

We hypothesise the potential explanation of the subgroup analysis according to different renal function is that patients with relatively normal level of eGFR fail to perform enough discrepancy to distinguish high-risk patients, to these patients, our novel index apelin-12 show its superiority in predicting MACEs.

This study is not without limitations. The study cohort was relatively small. which may affect the statistical results. A larger-scale study is warranted to further assess the risk of long-term MACEs after pPCI in patients with STEMI. The base level of apelin prior to STEMI onset is difficult to obtain, therefore the degree of apelin reduction is unknown. Finally, this study only focused on apelin-12, analysis on other forms of apelin is recommended.

Conclusion

In conclusion, patients with STEMI receiving pPCI with lower levels of apelin-12 are more likely to have poor short-term and long-term prognosis after adjusting for other clinical parameters. Furthermore, apelin-12 may be beneficial in predicting MACEs among patients with eGFR>90 mL/min×1.73 m2.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: LY, TZ, HW, WX, XM, HL, YC and XW conceived and designed the study. XM, HL and YC collected the statistics. LY, TZ and HW performed the statistical analysis. LY wrote the paper. WX and XW reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Research Ethics Committee of The First People’s Hospital of Taizhou.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the doi:10.5061/dryad.pf56m.

References

- 1. Kilic S, Ottervanger JP, Dambrink JH, et al. . The effect of thrombus aspiration during primary percutaneous coronary intervention on clinical outcome in daily clinical practice. Thromb Haemost 2014;111:165–71. 10.1160/TH13-05-0433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Steg PG, James SK, Atar D, et al. . ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2569–619. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pedersen F, Butrymovich V, Kelbæk H, et al. . Short- and long-term cause of death in patients treated with primary PCI for STEMI. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:2101–8. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.08.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chandrasekaran B, Dar O, McDonagh T. The role of apelin in cardiovascular function and heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2008;10:725–32. 10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yi L, Hou X, Zhou J, et al. . HIF-1α genetic variants and protein expression confer the susceptibility and prognosis of gliomas. Neuromolecular Med 2014;16:578–86. 10.1007/s12017-014-8310-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sonmez A, Celebi G, Erdem G, et al. . Plasma apelin and ADMA levels in patients with essential hypertension. Clin Exp Hypertens 2010;32:179–83. 10.3109/10641960903254505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boal F, Roumegoux J, Alfarano C, et al. . Apelin regulates FoxO3 translocation to mediate cardioprotective responses to myocardial injury and obesity. Sci Rep 2015;5:16104 10.1038/srep16104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Leal VO, Lobo JC, Stockler-Pinto MB, et al. . Apelin: a peptide involved in cardiovascular risk in hemodialysis patients? Ren Fail 2012;34:577–81. 10.3109/0886022X.2012.668490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lakomkin SV, Tereshchenko SN, Sychev AV, et al. . Biomarkers in heart failure: apelin level is not associated With presence and severity of the disease. Kardiologiia 2015;55:37–41. 10.18565/cardio.2015.2.37-41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cosansu K, Cakmak HA, Ikitimur B, et al. . Apelin in ST segment elevation and non-ST segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: a novel finding. Kardiol Pol 2014;72:239–45. 10.5603/KP.a2013.0251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kuklinska AM, Sobkowicz B, Sawicki R, et al. . Apelin: a novel marker for the patients with first ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Heart Vessels 2010;25:363–7. 10.1007/s00380-009-1217-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sans-Roselló J, Casals G, Rossello X, et al. . Prognostic value of plasma apelin concentrations at admission in patients with ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction. Clin Biochem 2017;50:279–84. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2016.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Manjunath G, Sarnak MJ, Levey AS. Prediction equations to estimate glomerular filtration rate: an update. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2001;10:785–92. 10.1097/00041552-200111000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tycinska AM, Lisowska A, Musial WJ, et al. . Apelin in acute myocardial infarction and heart failure induced by ischemia. Clin Chim Acta 2012;413:406–10. 10.1016/j.cca.2011.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Scimia MC, Hurtado C, Ray S, et al. . APJ acts as a dual receptor in cardiac hypertrophy. Nature 2012;488:394–8. 10.1038/nature11263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chong KS, Gardner RS, Morton JJ, et al. . Plasma concentrations of the novel peptide apelin are decreased in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2006;8:355–60. 10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Japp AG, Newby DE. The apelin-APJ system in heart failure: pathophysiologic relevance and therapeutic potential. Biochem Pharmacol 2008;75:1882–92. 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kadoglou NP, Lampropoulos S, Kapelouzou A, et al. . Serum levels of apelin and ghrelin in patients with acute coronary syndromes and established coronary artery disease--KOZANI STUDY. Transl Res 2010;155:238–46. 10.1016/j.trsl.2010.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Weir RA, Chong KS, Dalzell JR, et al. . Plasma apelin concentration is depressed following acute myocardial infarction in man. Eur J Heart Fail 2009;11:551–8. 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Busch R, Strohbach A, Pennewitz M, et al. . Regulation of the endothelial apelin/APJ system by hemodynamic fluid flow. Cell Signal 2015;27:1286–96. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2015.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ronkainen VP, Ronkainen JJ, Hänninen SL, et al. . Hypoxia inducible factor regulates the cardiac expression and secretion of apelin. Faseb J 2007;21:1821–30. 10.1096/fj.06-7294com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zeng XJ, Zhang LK, Wang HX, et al. . Apelin protects heart against ischemia/reperfusion injury in rat. Peptides 2009;30:1144–52. 10.1016/j.peptides.2009.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhang BH, Guo CX, Wang HX, et al. . Cardioprotective effects of adipokine apelin on myocardial infarction. Heart Vessels 2014;29:679–89. 10.1007/s00380-013-0425-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tempel D, de Boer M, van Deel ED, et al. . Apelin enhances cardiac neovascularization after myocardial infarction by recruiting aplnr+ circulating cells. Circ Res 2012;111:585–98. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.262097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang W, McKinnie SM, Patel VB, et al. . Loss of Apelin exacerbates myocardial infarction adverse remodeling and ischemia-reperfusion injury: therapeutic potential of synthetic Apelin analogues. J Am Heart Assoc 2013;2:e000249 10.1161/JAHA.113.000249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hou X, Zeng H, He X, et al. . Sirt3 is essential for apelin-induced angiogenesis in post-myocardial infarction of diabetes. J Cell Mol Med 2015;19:53–61. 10.1111/jcmm.12453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li L, Zeng H, Hou X, et al. . Myocardial injection of apelin-overexpressing bone marrow cells improves cardiac repair via upregulation of Sirt3 after myocardial infarction. PLoS One 2013;8:e71041 10.1371/journal.pone.0071041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cirillo P, Ziviello F, Pellegrino G, et al. . The adipokine apelin-13 induces expression of prothrombotic tissue factor. Thromb Haemost 2015;113:113:363–372. 10.1160/TH14-05-0451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Siddiquee K, Hampton J, Khan S, et al. . Apelin protects against angiotensin II-induced cardiovascular fibrosis and decreases plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 production. J Hypertens 2011;29:724–31. 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32834347de [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kumagai S, Nakayama H, Fujimoto M, et al. . Myeloid cell-derived LRG attenuates adverse cardiac remodelling after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res 2016;109:272–82. 10.1093/cvr/cvv273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. El-Shehaby AM, El-Khatib MM, Battah AA, et al. . Apelin: a potential link between inflammation and cardiovascular disease in end stage renal disease patients. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 2010;70:421–7. 10.3109/00365513.2010.504281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yu XH, Tang ZB, Liu LJ, et al. . Apelin and its receptor APJ in cardiovascular diseases. Clin Chim Acta 2014;428:1–8. 10.1016/j.cca.2013.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ustunel I, Acar N, Gemici B, et al. . The effects of water immersion and restraint stress on the expressions of apelin, apelin receptor (APJR) and apoptosis rate in the rat heart. Acta Histochem 2014;116:675–81. 10.1016/j.acthis.2013.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stöhr R, Kappel BA, Carnevale D, et al. . TIMP3 interplays with apelin to regulate cardiovascular metabolism in hypercholesterolemic mice. Mol Metab 2015;4:741–52. 10.1016/j.molmet.2015.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pisarenko OI, Serebryakova LI, Studneva IM, et al. . Effects of structural analogues of apelin-12 in acute myocardial infarction in rats. J Pharmacol Pharmacother 2013;4:198–203. 10.4103/0976-500X.114600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liu HT, Chen M, Yu J, et al. . Serum apelin level predicts the major adverse cardiac events in patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction receiving percutaneous coronary intervention. Medicine 2015;94:e449 10.1097/MD.0000000000000449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Topuz M, Oz F, Akkus O, et al. . Plasma apelin-12 levels may predict in-hospital major adverse cardiac events in ST-elevation myocardial infarction and the relationship between apelin-12 and the neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio in patients undergoing primary coronary intervention. Perfusion 2017;32:206–13. 10.1177/0267659116676335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Japp AG, Cruden NL, Barnes G, et al. . Acute cardiovascular effects of apelin in humans: potential role in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation 2010;121:1818–27. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.911339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhang M, Mahoney E, Zuo T, et al. . Protein kinase A activation enhances β-catenin transcriptional activity through nuclear localization to PML bodies. PLoS One 2014;9:e109523 10.1371/journal.pone.0109523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Grzywocz P, Mizia-Stec K, Wybraniec M, et al. . Adipokines and endothelial dysfunction in acute myocardial infarction and the risk of recurrent cardiovascular events. J Cardiovasc Med 2015;16:37–44. 10.2459/JCM.0000000000000042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kadoglou NP, Sailer N, Moumtzouoglou A, et al. . Adipokines: a novel link between adiposity and carotid plaque vulnerability. Eur J Clin Invest 2012;42:1278–86. 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2012.02728.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.