Supplemental digital content is available in the text.

Key Words: anxiety, depression, meta-analysis, rheumatoid arthritis, systematic review

Abstract

Background

Psychiatric comorbidities, such as depression and anxiety, are very common in persons with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and can lead to adverse outcomes. By appropriately treating these comorbidities, disease-specific outcomes and quality of life may be improved.

Objective

The aim of this study was to systematically review the literature from controlled trials of treatments for depression and anxiety in persons with RA.

Methods

We searched multiple online databases from inception until March 25, 2015, without restrictions on language, date, or location of publication. We included controlled trials conducted in persons with RA and depression or anxiety. Two independent reviewers extracted information including trial and participant characteristics. The standardized mean differences (SMDs) of depression or anxiety scores at postassessment were pooled between treatment and comparison groups, stratified by active versus inactive comparators.

Results

From 1291 unique abstracts, we included 8 RA trials of depression interventions (6 pharmacological, 1 psychological, 1 both). Pharmacological interventions for depression with inactive comparators (n = 3 trials, 143 participants) did not reduce depressive symptoms (SMD, −0.21; 95% confidence interval [CI], −1.27 to 0.85), although interventions with active comparators (n = 3 trials, 190 participants) did improve depressive symptoms (SMD, −0.79; 95% CI, −1.34 to −0.25). The single psychological trial of depression treatment in RA did not improve depressive symptoms (SMD, −0.44; 95% CI, −0.96 to 0.08). Seven of the trials had an unclear risk of bias.

Conclusions

Few trials examining interventions for depression or anxiety in adults with RA exist, and the level of evidence is low to moderate because of the risk of bias and small number of trials.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic immune-mediated arthropathy that affects more than 1.3 million Americans1,2 and more than 15 million people worldwide.3 Because the peak age at onset is in the fourth and fifth decades of life, RA affects individuals in the prime of their lives from social and work perspectives and is associated with considerable disability.4–6 Depression will affect up to 66% and anxiety up to 70% of individuals with RA,7–9 and almost 17% of persons with RA have a current major depressive disorder.10

Psychiatric comorbidity is associated with adverse outcomes in RA. In persons with RA, depression is associated with higher levels of pain and disability, lower health-related quality of life (QOL), and increased mortality.11–13 Depression is a greater predictor of work disability in early arthritis than both disease activity and response to treatment.14 Symptoms of depression and anxiety are associated with increased disease activity, a reduced response to RA symptom treatment, and a decreased likelihood of achieving RA symptom remission.15 Managing depression and anxiety may be a means of improving outcomes in persons with RA, but commonly used pharmacological treatments for depression may be less effective in persons with RA who use anti-inflammatory therapies16 or lead to potentially harmful adverse effects or exacerbations in symptoms.17

The primary objective of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to identify the existing literature pertaining to controlled trials of pharmacological and psychological interventions for depression and anxiety in persons with RA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted this systematic review using an a priori published protocol,18 according to the approach described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews. We report the findings according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) criteria.19,20

Populations, Interventions, Comparators, Settings, and Study Designs

As symptoms of depression and anxiety are very common, a threshold at which treatment may be initiated must be established, to ensure that only those who could benefit from treatment are exposed to the potential risks of therapies and to ensure that symptoms were severe enough that treatment could have an effect. Therefore, we included trials conducted in persons with RA who were depressed and/or anxious to ensure that effects were assessed in the population in which the intervention would later be applied. Rheumatoid arthritis was defined according to the criteria reported in each article. Eligible trials were controlled clinical trials (i.e., randomized controlled trials [RCTs], controlled before and after trials) conducted in any clinical setting. Diagnoses of depression or anxiety could be identified based on a clinical interview or self-report using a screening tool. There were no other prespecified criteria regarding the definition of depression or anxiety, and we examined the methods used by individual papers to identify the study populations, including the instruments used. We excluded trials if the entire sample was younger than 18 years to reduce heterogeneity.

Outcome Measures

We identified 1 primary research question: “What is the efficacy of pharmacological and psychological treatments for depression or anxiety in persons with RA?” Based on recommendations from primary care providers and individuals living with RA, we included the following secondary outcomes: (1) difference in fatigue scores at postassessment between the treatment and comparison groups, (2) difference in QOL scores at postassessment between the treatment and comparison groups, (3) difference in pain scores at postassessment between the treatment and comparison groups, and (4) the proportion of participants achieving 50% reduction or greater in depressive or anxious symptoms from baseline to postassessment between the treatment and control. In all cases, postassessment was the longest reported follow-up.

The tolerability of pharmacotherapy for depression or anxiety in RA was examined according to the dose and duration of the treatment, dropout rates, and any reported adverse effects.

Search Strategy

Our search strategies (see lists, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/RHU/A65 which detail the searches) were developed with the help of a medical librarian (M.F.) and experts in rheumatic disease (C.A.H., C.A.P.) and psychiatric disorders (S.B.P., J.W., L.G., K.M.F., J.S., J.B.). We identified RCTs and related systematic reviews using the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and the following databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES Full Text, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, CINAHL, Web of Science, and Scopus. To identify completed or ongoing trials, we searched Clinicaltrials.gov and the World Health Organization trial register. To identify additional citations, we searched the reference lists of related systematic reviews and of the included trials. There were no date or language limits placed on the searches. Databases were searched from inception date to March 25, 2015. The Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy was used in MEDLINE, and variations of this filter, or other validated filters, were used for other databases.

Study Selection Process

EPPI-Reviewer21 was utilized for the 2-phase title and abstract review by 2 independent reviewers (K.M.F. and R.A.M.). Titles and abstracts were reviewed in the first phase to determine if they were conducted in individuals with RA and who had depression or anxiety. In the second phase, these abstracts were determined to be clinical trials or not. Subsequently, the same reviewers also independently reviewed full-text articles in detail to ensure all inclusion criteria were met, and disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Data Extraction and Management

Data collection was completed by 2 independent reviewers using a data collection tool developed by the author team and implemented in EPPI-Reviewer. We extracted information on study design, inclusion criteria for the study population including demographic or disease characteristics (e.g., age, sex, disease subtype, race/ethnicity), methods for identifying psychiatric comorbidity (e.g., diagnostic interview, self-report questionnaire) including the tools used, interventions used, items related to the risk of bias assessment (see below), and any efficacy or safety outcomes. We sought translation for the non-English articles.

Risk of Bias Assessment and Grading the Evidence

The internal validity of the trials was independently evaluated by 2 reviewers using the Cochrane Collaboration’s Risk of Bias tool.22 This tool evaluates risk of bias in 6 domains: sequence generation; allocation concealment; masking/blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessors; incomplete outcome data; selective outcome reporting; and other sources of bias. Each domain is rated as having either a low risk of bias, unclear risk of bias, or high risk of bias. The overall assessment is based on responses to individual domains; the overall score was rated as having a high risk of bias if 1 or more individual domains is assessed as having a high risk of bias. Only if all components are rated as having a low risk of bias is the overall risk rated as low. Risk of bias for all other studies was rated as unclear. Disagreements on the bias assessment were resolved by discussion. The approach described by the GRADE working group was used to determine the strength of the evidence: low, moderate, or high.23

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Descriptive statistics, including mean, median, SD, interquartile range, and frequencies (reported as a percent), were used to summarize the study findings. Because the tools used to measure depression differed between trials, we chose the standardized mean difference (SMD) as the outcome measure. We calculated the SMD using depression or anxiety scores on any depression or anxiety tool at postassessment between the treatment and comparison groups. The size of the effect was measured in SD units. Small, medium, and large effects are represented by SMDs of 0.20, 0.50, and 0.80, respectively.24 In the context of these analyses, a negative SMD indicates an improvement of symptoms in favor of the intervention (except in the instance of QOL, where a positive SMD indicates improvement). Because the proportion achieving a 50% reduction in symptoms was a categorical outcome, an odds ratio with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) was calculated to compare groups.

Summary effect measures were generated using Review Manager (RevMan 5.3).25 Analyses are presented overall and stratified by the type of comparison group used: active (i.e., another form of psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy) or inactive (placebo, wait-list control, usual care). For the sole 3-arm trial identified, we included only 1 comparison (cognitive behavioral therapy [CBT] vs. sertraline) in the meta-analysis.26 Heterogeneity was quantified using the I2 statistic, and its significance determined by the Q P value. I2 is calculated directly from the Q statistic; I2 of 0% indicates the absence of observed heterogeneity, whereas values of 25%, 50%, and 75% translate to low, medium, and high heterogeneity, respectively.27 All pooled estimates were calculated using a random-effects model with the accompanying 95% CI. Metaregression was not conducted because of the small number of eligible studies (i.e., <10).28 R v3.1.129 was used to assess publication bias using funnel plots, Begg rank test,30 or Egger’s regression test.31

RESULTS

Results of the Search

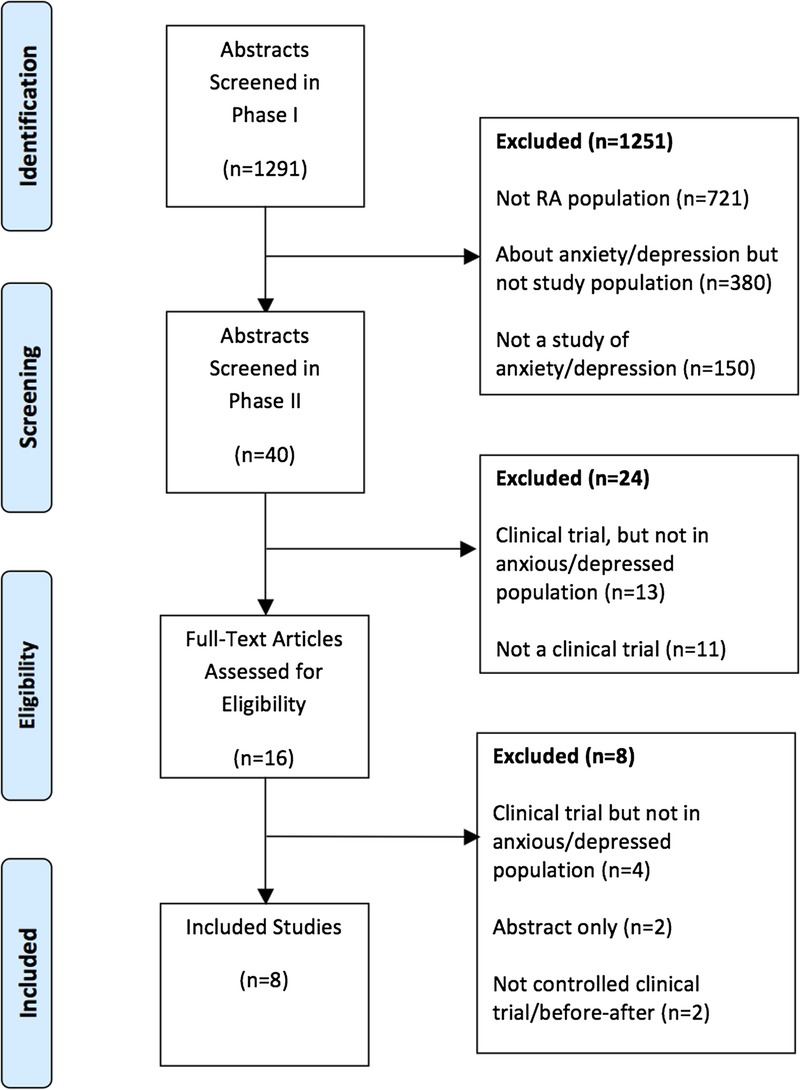

We initially screened 1291 unique abstracts and excluded 1251 in the first phase. The majority (58%) were excluded because they did not report on a population with RA (721/1251), whereas a further 380 (30%) did not report on a group with depression or anxiety, and finally, 150 (12%) did not study depression or anxiety (Fig. 1, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/RHU/A66). After the second phase, where 24 more abstracts were excluded (13/24 were not conducted in persons with depression or anxiety, and 11/24 were not clinical trials), the full texts of 16 articles were reviewed, of which 8 met all inclusion criteria (Table). The age restriction exclusion criteria (no studies including those <18 years old) did not result in the exclusion of any studies.

FIGURE 1.

Study flow diagram.

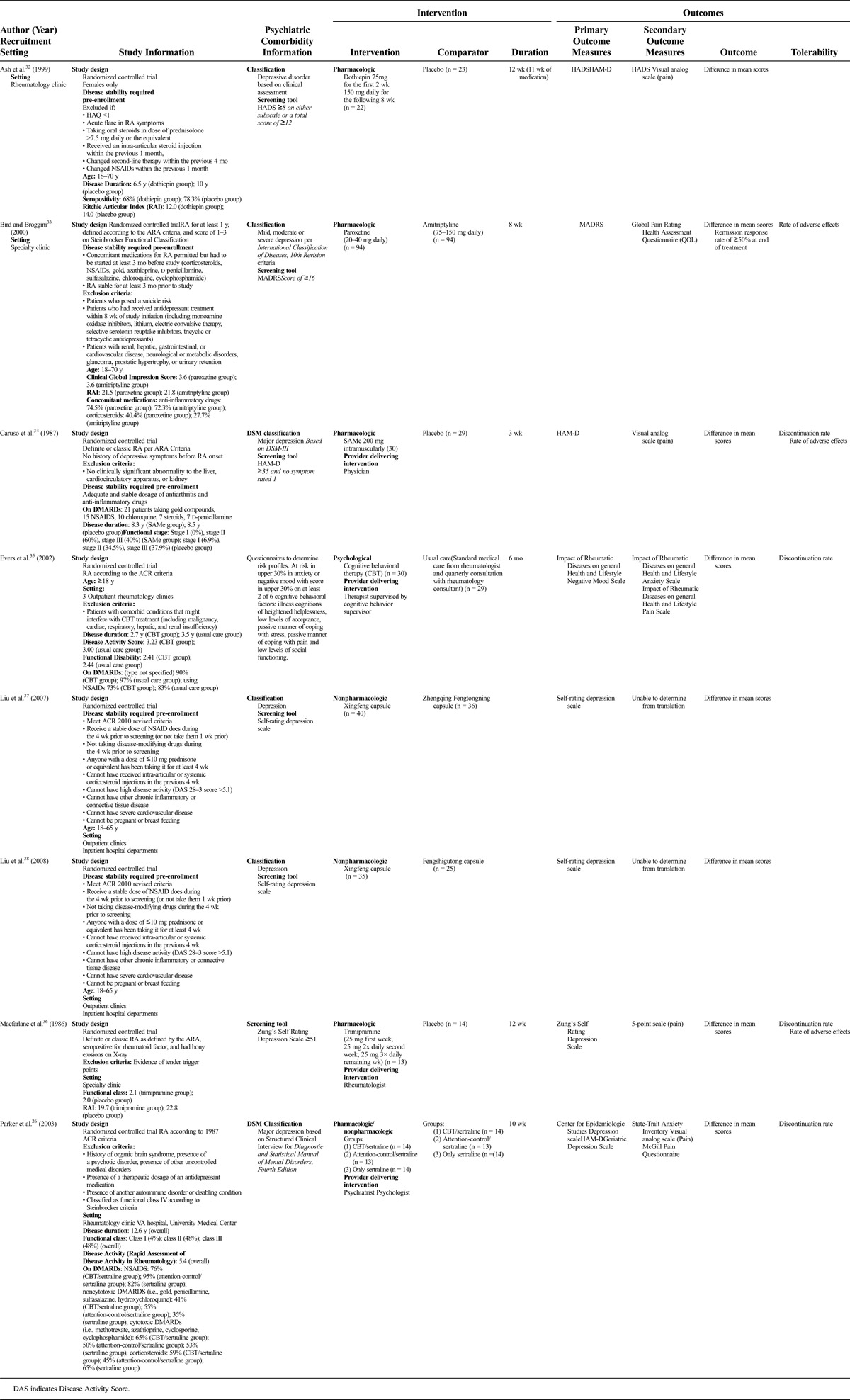

TABLE.

Included Studies

Description of Trials

All trials were RCTs that investigated treatments for depression (i.e., none investigated anxiety as the primary outcome) and were published between 1986 and 2008 in Europe (n = 4),32–35 North America (n = 2),26,36 or Asia (n = 2).37,38 The number of participants in the included trials ranged from 36 to 188 (mean, 74.8 [SD, 56.3]). Most trials (n = 6) assessed the effect of pharmacotherapy,32–34,36–38 one investigated a psychological intervention,35 and another trial used a combined pharmacological and psychological approach.26 All trials investigated the effect of the intervention on symptoms of depression as the primary outcome, and 3 assessed anxiety as a secondary outcome.26,32,35 Eight different instruments were used to measure depression in the included trials (Table). Five of the 6 studies26,32,35,37,38 published after the 1987 release of the American College of Rheumatology diagnostic criteria39 used it as such. The 2 studies34,36 published prior to/in 1987 used the 1958 American Rheumatism Association (ARA) diagnostic criteria,40 and the final study33 used the 1982 criteria from the ARA.41

Interventions and Assessments

The duration of treatment in the included trials ranged from 3 to 24 weeks (mean, 11.5 [SD, 7.0] weeks). Three of the 6 pharmacological trials compared the medication with placebo,32,34,36 one compared the effects of 2 medications,33 and 2 others compared the effects of 2 Chinese herbs.37,38 The examined medications were dothiepin, S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe), trimipramine, paroxetine versus amitriptyline, Xingfeng capsule versus Zhengqing Fengtongning capsule, and Xingfeng capsule versus Fengshigutong capsule. The psychological intervention compared individualized CBT with usual care,35 and the combined pharmacological/psychological trial examined the use of sertraline alone as compared with sertraline combined with either CBT or attention-control therapy.26

The most commonly used tool to assess depression as an outcome was the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D), used in 3 of 8 trials.26,32,34 Anxiety was assessed as a secondary outcome in 3 trials, using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS),32 Impact of Rheumatic Diseases on General Health and Lifestyle (IRGL) anxiety scale,35 and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory.26 All trials examined the effect of the intervention on pain, and QOL was assessed in 3 trials.

Most RA trials (n = 5) used a single tool to determine trial eligibility, including the Self-rating Depression Scale (n = 2), the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition26 (n = 1), Zung’s Self-rating Depression Scale36 (n = 1), or IRGL questionnaire (n = 1).35 The remaining 3 RA trials used multiple methods to assess trial eligibility; 2 trials used a clinician assessment and either the HADS32 or the HAM-D,34 whereas the study by Bird and Broggini33 used International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision codes and the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS).

Other depression tools used to assess outcomes were the HADS, MADRS, IRGL depression scale, Zung’s Self-rating Depression Scale, the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, the Geriatric Depression Scale, and the Self-rating Depression Scale.

Risk of Bias Assessment

Seven of the RA trials had an unclear risk of bias, whereas the final RA trial had a high risk of bias due to failures of blinding (see Figure and Table, Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/RHU/A67 and 4, http://links.lww.com/RHU/A68 for risk of bias assessment).

Primary Outcomes

Depression

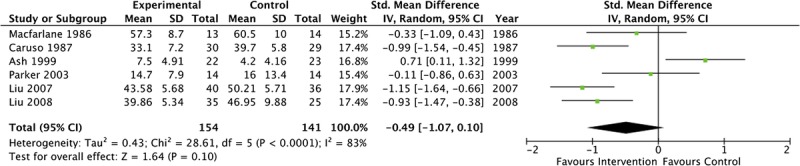

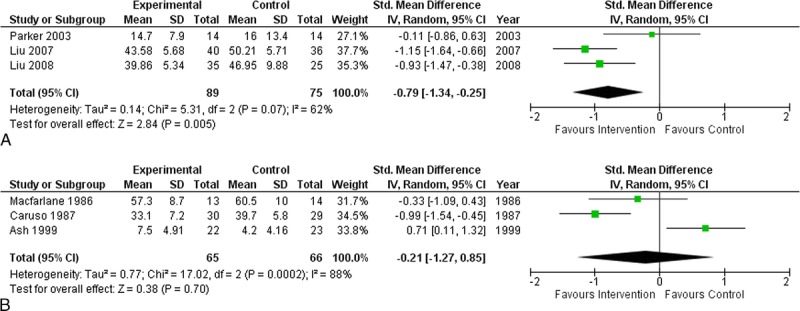

Overall, interventions for depression in RA (n = 6 trials, 295 participants) did not result in a reduction in depressive symptoms (SMD, −0.49 [95% CI, −1.07 to 0.10]) (Fig. 2). There was significant heterogeneity between estimates: I2 = 83%, Q P < 0.0001. When pharmacological trials were stratified by whether the comparator was an active treatment (such as an antidepressant medication) or inactive comparison (placebo), interventions with an active treatment comparison (n = 3 trials, 164 participants) were associated with a reduction in depressive symptoms (SMD, −0.79 [95% CI, −1.34 to −0.25]) (Fig. 3A). There was no improvement in depressive symptoms for those pharmacological trials using an inactive comparator (n = 3 trials, 131 participants) (SMD, −0.21 [95% CI, −1.27 to 0.85]) (Fig. 3B). Stratification by treatment comparator did not reduce the amount of heterogeneity present for inactive comparators (I2 = 88%, Q P < 0.0001), although it did for trials with active comparators (I2 = 62%, Q P < 0.0001). When analyzed separately, the 2 trials using a Chinese herbal supplement were effective in reducing symptoms of depression (SMD, −1.05 [95% CI, −1.41 to −0.69]). The trial by Ash et al.32 may have included persons with subthreshold depression (resulting in less room for improvement); the analysis was repeated without this trial, and following this depressive symptoms showed improvement (SMD, −0.78 [95% CI, −1.14 to −0.42]).

FIGURE 2.

Overall forest plot of pharmacological treatments for symptoms of depression.

FIGURE 3.

A, Forest plot of pharmacological treatments with active comparators for symptoms of depression. B, Forest plot of pharmacological treatments with inactive comparators for symptoms of depression.

The single psychological therapy trial of depression treatment in RA showed no improvement in depressive symptoms (SMD, −0.44 [95% CI, −0.96 to 0.08]).

Anxiety

Anxiety symptoms did not improve in any trial of depression treatment (pharmacological or psychological), regardless of the comparison group used: a single trial with an active comparator (SMD, 0.24 [95% CI, −0.51 to 0.98]) and 2 trials with inactive comparators (SMD, −0.11 [95% CI, −1.01 to 0.79]).

Strength of Evidence

There was a range in evidence strength in the included trials: 4 trials were moderate quality, 2 trials were high quality, 1 trial was low quality, and 1 trial was very low quality (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 5, http://links.lww.com/RHU/A69 for ratings). Overall, the body of evidence for depression interventions in RA was of moderate strength.

Secondary Outcomes

Depression

In the single RCT that reported on the proportion of patients achieving 50% reduction or greater in symptoms,33 there was no difference between the 2 active pharmacological treatments (P = 0.296).

Pain

Pain scores in RA did not improve in 3 trials of depression interventions with an active comparator (SMD, −0.05 [95% CI, −0.36 to 0.25]) or in 3 trials with an inactive comparator (SMD, −0.60 [95% CI, −1.22 to 0.03]).

Fatigue

Fatigue was not reported as an outcome in any of the trials.

Quality of Life

Quality of life in RA did not improve in 2 trials of depression interventions with an active comparator (SMD, −0.22 [95% CI, −1.03 to 0.59]) or a single depression intervention trial with an inactive comparator (SMD, 0.02 [95% CI, −0.57 to 0.60]).

Tolerability

Three RA trials reported on adverse medication effects;33,34,36 the trial comparing paroxetine to amitriptyline reported more adverse events in the amitriptyline group,33 whereas nausea was more common in the placebo group of the trimipramine trial36 (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 6, http://links.lww.com/RHU/A70 for adverse effects). The dropout rates in the treatment groups of the RA trials ranged from 0.0% to 35.0%.

Publication Bias

Significant publication bias was not detected on any primary or secondary outcomes for the included trials analyzed using both Begg and Egger tests. All funnel plots appeared symmetrical based on visual inspection.

DISCUSSION

In our systematic review of the literature, we found only 8 RCTs reporting on interventions for treating depression in RA and none reporting on interventions for anxiety in RA. Among pharmacological interventions, only those with an active comparison group were effective in reducing symptoms of depression in RA. Some trials either did not report the effects of the interventions on fatigue, pain, or QOL or did not report a statistically significant benefit in those domains. The sole study of a psychological intervention alone showed benefit for treating depression, but this did not reach statistical significance.

Most of the included trials examined the use of pharmacological interventions for treating depression; those trials using active comparators were effective in reducing symptoms of depression. No interventions for depression were effective in reducing symptoms of anxiety. Trimipramine, sertraline, and CBT are conventional treatment strategies for depression, whereas dothiepin is not available in North America, SAMe is not a first-line treatment for depression, and the specific Chinese herbal supplements are not widely available in other countries for treatment of depression. The 2 trials of Chinese herbal supplements included persons with low disease activity and those not treated with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs); therefore, these study populations may not be representative of the typical RA patient. The pooled estimate of these trials should be interpreted with caution, as most do not utilize treatment methods that are currently in wide use; the evidence to support pharmacotherapy for depression treatment in RA is therefore limited. There is a dearth of studies exploring the effects of controlled interventions for anxiety in persons with RA, although anxiety has numerous negative effects in persons with RA, including greater fatigue11 and increased disease activity.15

It is necessary to explore the use of these treatments for depression and anxiety in RA specifically, as affected persons may respond differently to treatment or experience disease-specific adverse effects (or more severe adverse effects). Psychotropic medications may exacerbate already elevated levels of fatigue.42 There may also be interactions between and treatments commonly used for depression in RA and DMARDs or other anti-inflammatory therapies. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants in combination with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) commonly used in RA may impair platelet function, increasing the risk of gastrointestinal and intracranial bleeding.43,44 Some commonly used SSRIs (i.e., escitalopram, citalopram) may also confer an increased risk of bleeding when used in combination with 5-aminosalicylic acid.45 A post hoc analysis of a large clinical trial revealed that persons using NSAIDs were less likely to achieve remission on SSRI therapy, compared with those not using NSAIDs, possibly by altering cytokine and other regulatory protein concentrations.16 One study showed less frequent mood and anxiety disorders in patients on tumor necrosis factor inhibitors compared with those on nonbiological or no DMARDs.46 This effect has not been studied with other biologic DMARDs but may reflect the greater effectiveness of these newer drugs, with demonstrated greater improvement in disease activity and QOL. In 2 of the 3 studies published since the introduction of biologic DMARDs (ranging from 2003 to 2008), participants were ineligible for inclusion if they were on DMARDs, and in the other study, no participants were on biologic DMARDs. Given the increasingly widespread use of biologic DMARDs, future intervention studies will need to consider the potential for such disease-treatment interactions.

The trials included in this review used 8 different scales to measure symptoms of depression in RA, most using the HAM-D. The validity of these depression scales has not been assessed in a sample with RA, although many have been validated in the general population. A recent systematic review of the prevalence of depression in RA recommended validating the commonly used depression tools and specifically assessing the cutoff points to define depression.10 It is imperative that depression and anxiety screening tools be validated in disease-specific settings to ensure scale performance is adequate; investigate potential confounding effects, including those of somatic symptoms; and assess the optimal scoring criteria.

Based on the GRADE system, the strength of the evidence from RA trials was moderate. All but 1 RA trial had an unclear risk of bias; the remaining RA trial was rated as a high risk of bias due to a lack of blinding. The overall strength of the evidence was lower, and risk of bias higher, in psychological trials. In psychotherapy interventions, the ability to adequately blind participants, outcome assessors, and investigators is limited because of the nature of the intervention; blinding may not be necessary, however, and there are proposed methods for how to minimize bias related to this complex issue.47 The RA trials using active comparators were published more recently and had a larger number of participants than those using inactive comparators. In addition, 2 of the 3 trials with active comparators included participants with low disease activity, differing somewhat for the trials without active comparators. These and other differences in the patient populations may also account for the differences observed and may account for finding benefit in trials with active comparators and not in those with inactive comparators. Significant statistical heterogeneity was present between pooled estimates of pharmacotherapy, anxiety, and QOL. This reduces the confidence in our findings, and the estimates should be interpreted cautiously.

As depression and anxiety affect treatment responses to RA-specific therapies14 and adversely affect mortality and QOL,11–13 it is essential to adequately and appropriately treat these comorbidities. Our findings highlight paucity of information to support clinicians treating depression and anxiety in RA and underscore the urgent need for further intervention trials in the area of psychiatric comorbidity in RA to inform clinical care. Furthermore, as depression and anxiety are chronic health conditions, it is important for future trials to be conducted with extended follow-up periods to determine effectiveness over the long term. We convened advisory groups to identify outcomes aside from the psychiatric ones that are important to patients and practitioners (pain, fatigue, and QOL). Despite their perceived importance, it is unclear what interventions might have the greatest impact on these domains. Drugs used to treat depression and anxiety may have pharmacodynamic effects on the underlying chronic inflammatory disease, which might be best captured with other outcomes. Similarly, psychotherapy in depression and anxiety may have different outcomes in persons with immune diseases than in persons without them. It is possible the distress caused by the chronic disease itself or the ongoing inflammatory state may render the psychiatric comorbidity more difficult to treat. This needs to be studied.

The next trials in the area of psychiatric comorbidity in RA should include measures of outcomes in the psychiatric comorbidity and the immune disease under study. It is critical to understand the evolution of the underlying immune disease while the psychiatric illness is treated. To fully understand if there are specific features of RA that are associated with a greater burden of depression and anxiety, to determine the optimal instruments that best identify these conditions in RA, and to determine if there are relevant biomarkers, prospective cohort studies should be undertaken so that future clinical trials can be purposefully planned.

Supplementary Material

Morning Calm – Waiting for the ferry in Port Townsend, WA

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Michelle Fiander, MLIS (Fiander Consulting), and Tania Gottschalk, MEd, MSc, BA (librarian, University of Manitoba), who provided assistance regarding the development of the search strategies for this review. They also Dr. Jerry Parker for providing additional information and data from his original publications to allow meta-analyses to be conducted.

The authors acknowledge the members of the CIHR team on “Defining the Burden and Managing the Effects of Psychiatric Comorbidity in Chronic Immunoinflammatory Disease”: Dr. Ruth Ann Marrie, MD, PhD (University of Manitoba), Dr. Charles Bernstein, MD (University of Manitoba), Dr. Lindsay Berrigan, PhD (St. Francis Xavier University), Dr. James Bolton, MD (University of Manitoba), Dr. John Fisk, PhD (Dalhousie University), Dr. Lesley Graff, PhD (University of Manitoba), Dr. Carol Hitchon, MD, MSc (University of Manitoba), Dr. Alan Katz, MB, ChB (University of Manitoba), Dr. Lisa Lix, PhD (University of Manitoba), Dr. James Marriot, MD, MSc (University of Manitoba), Dr. Scott Patten, MD, PhD (University of Calgary), Dr. Jitender Sareen, MD (University of Manitoba), Dr. John Walker, PhD (University of Manitoba), Dr. Ryan Zarychanski, MD, MSc (University of Manitoba), Dr. Alexander Singer, MD (University of Manitoba), and Dr. Christine Peschken, MD, MSc (University of Manitoba).

Footnotes

All authors have made substantial contributions to this work. K.M.F., J.R.W., C.N.B., L.A.G., and R.A.M. designed the study; K.M.F. and R.A.M. participated in the acquisition and analysis of the data, and all authors interpreted the resultant data. K.M.F., C.N.B., and R.A.M. drafted the manuscript, and all authors participated in the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. K.M.F. performed the statistical analyses. C.N.B., J.R.W., L.A.G., C.A.H., and R.A.M. obtained funding for the present study.

R.A.M. had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

This study was funded in part by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, a Don Paty Career Development Award from the MS Society of Canada (to R.A.M.), the Bingham Chair in Gastroenterology (to C.N.B.), and a Manitoba Research Chair from Research Manitoba (to R.A.M., J.S.).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

The funding organizations did not have any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.jclinrheum.com).

Contributor Information

Collaborators: for the CIHR Team “Defining the Burden and Managing the Effects of Psychiatric Comorbidity in Chronic Immunoinflammatory Disease”

REFERENCES

- 1.Health Canada. Arthritis in Canada: An Ongoing Challenge. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Health Canada; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:15–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, et al. The global burden of rheumatoid arthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1316–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eberhardt K, Larsson BM, Nived K, et al. Work disability in rheumatoid arthritis—development over 15 years and evaluation of predictive factors over time. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:481–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiles NJ, Dunn G, Barrett EM, et al. One year followup variables predict disability 5 years after presentation with inflammatory polyarthritis with greater accuracy than at baseline. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:2360–2366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pollard L, Choy EH, Scott DL. The consequences of rheumatoid arthritis: quality of life measures in the individual patient. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23(5 Suppl 39):S43–S52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Isik A, Koca SS, Ozturk A, et al. Anxiety and depression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:872–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lok EY, Mok CC, Cheng CW, et al. Prevalence and determinants of psychiatric disorders in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Psychosomatics. 2010;51:338–338 e338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.VanDyke MM, Parker JC, Smarr KL, et al. Anxiety in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:408–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matcham F, Rayner L, Steer S, et al. The prevalence of depression in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2013;52:2136–2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mok C, Lok E, Cheung E. Concurrent psychiatric disorders are associated with significantly poorer quality of life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2012;41:253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rupp I, Boshuizen HC, Jacobi CE, et al. Comorbidity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: effect on health-related quality of life. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:58–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van den Hoek J, Boshuizen HC, Roorda LD, et al. Association of somatic comorbidities and comorbid depression with mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a 14-year prospective cohort study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68:1055–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Callhoff J, Albrecht K, Schett G, et al. Depression is a stronger predictor of the risk to consider work disability in early arthritis than disease activity or response to therapy. RMD Open. 2015;1:e000020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matcham F, Norton S, Scott DL, et al. Symptoms of depression and anxiety predict treatment response and long-term physical health outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis: secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55:268–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warner-Schmidt JL, Vanover KE, Chen EY, et al. Antidepressant effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are attenuated by antiinflammatory drugs in mice and humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:9262–9267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peretti S, Judge R, Hindmarch I. Safety and tolerability considerations: tricyclic antidepressants vs. selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2000;403:17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fiest K, Marrie R, Abou-Setta A, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for depression and anxiety in persons with rheumatoid arthritis. 2015. Available at: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42015023772. Accessed February 10, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Chandler J, Churchill R, Higgins J, et al. Methodological Standards for the Conduct of New Cochrane Intervention Reviews, Version 2.3. 2013. Available at: http://www.editorial-unit.cochrane.org/mecir. Accessed March 30, 2016.

- 20.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–269, W264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas J, Brunton J, Graziosi S. EPPI-Reviwer 4: Software for Research Synthesis. EPPI-Centre Software. London: Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collaboration TC. Review Manager (RevMan). Copenhagen, Denmark: The Nordic Cochrane Centre; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parker JC, Smarr KL, Slaughter JR, et al. Management of depression in rheumatoid arthritis: a combined pharmacologic and cognitive-behavioral approach. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:766–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration; Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.R, R—Sock it to Me. The R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2014.

- 30.Begg C. Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. 1994;50:1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Egger M, Smith G. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ash G, Dickens CM, Creed FH, et al. The effects of dothiepin on subjects with rheumatoid arthritis and depression. Rheumatology (Oxford). 1999;38:959–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bird H, Broggini M. Paroxetine versus amitriptyline for treatment of depression associated with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, double blind, parallel group study. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:2791–2797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caruso I, Fumagalli M, Boccassini L, et al. Treatment of depression in rheumatoid arthritic patients. A comparison of S-adenosylmethionine (Samyr) and placebo in a double-blind study. Clin Trials J. 1987;24:305–310. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Evers AW, Kraaimaat FW, van Riel PL, et al. Tailored cognitive-behavioral therapy in early rheumatoid arthritis for patients at risk: a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2002;100:141–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Macfarlane JG, Jalali S, Grace EM. Trimipramine in rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized double-blind trial in relieving pain and joint tenderness. Curr Med Res Opin. 1986;10:89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu J, Yang M, Fan H. Xinfeng capsule for rheumatoid arthritis and depression and serum cortisol. Chin J Inform Trad Chin Med. 2007;14:7–9. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu J, Yu X, Zong R, et al. Effects of Xingfeng capsule on rheumatoid arthritis in active phase and depressed mood. J Fujian Univ Trad Chin Med. 2008;18:33–37. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ropes MW, Bennett GA, Cobb S, et al. 1958 Revision of diagnostic criteria for rheumatoid arthritis. Bull Rheum Dis. 1958;9:175–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.American Rheumatism Association. Dictionary of the Rheumatic Diseases, Volume I: Signs and Symptoms. New York: Contact Associates International; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferguson J. SSRI antidepressant medications: adverse effects and tolerability. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;3:22–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lexi-Comp Online. NSAID (nonselective)/antidepressants (tricyclic, tertiary amine). Lexi-Comp Online Interaction Monograph. Hudson, Ohio: Lexi-Comp, Inc; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lexi-Comp Online. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors/NSAID (nonselective). Lexi-Comp Online Interaction Monograph. Hudson, Ohio: Lexi-Comp, Inc; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lexi-Comp Online. Salicylates/agents with antiplatelet properties. Lexi-Comp Online Interaction Monograph. Hudson, Ohio: Lexi-Comp, Inc; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uguz F, Akman C, Kucuksarac S, et al. Anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy is associated with less frequent mood and anxiety disorders in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;63:50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boutron I, Guittet L, Estellat C, et al. Reporting methods of blinding in randomized trials assessing nonpharmacological treatments. PLoS Med. 2007;4:0370–0380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.