Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Abstract

The authors describe the first 11 academic years (2005–2006 through 2016–2017) of a longitudinal, small-group faculty development program for strengthening humanistic teaching and role modeling at 30 U.S. and Canadian medical schools that continues today. During the yearlong program, small groups of participating faculty met twice monthly with a local facilitator for exercises in humanistic teaching, role modeling, and related topics that combined narrative reflection with skills training using experiential learning techniques. The program focused on the professional development of its participants. Thirty schools participated; 993 faculty, including some residents, completed the program.

In evaluations, participating faculty at 13 of the schools scored significantly more positively as rated by learners on all dimensions of medical humanism than did matched controls. Qualitative analyses from several cohorts suggest many participants had progressed to more advanced stages of professional identity formation after completing the program. Strong engagement and attendance by faculty participants as well as the multimodal evaluation suggest that the program may serve as a model for others. Recently, most schools adopting the program have offered the curriculum annually to two or more groups of faculty participants to create sufficient numbers of trained faculty to positively influence humanistic teaching at the institution.

The authors discuss the program’s learning theory, outline its curriculum, reflect on the program’s accomplishments and plans for the future, and state how faculty trained in such programs could lead institutional initiatives and foster positive change in humanistic professional development at all levels of medical education.

Today’s doctors must demonstrate competence not only in scientific knowledge and diagnostic abilities but also in the interpersonal skills to care for patients with compassion and understanding. For clinician–educators to effectively foster those skills, then, necessarily involves advanced levels of personal and professional development. However, despite numerous recommendations for more humanistic medicine by experts and official bodies going back many decades,1–5 there is general agreement that medical education has failed to reach its humanistic goals.6–8 The profession, in general, falls short of its compact with society to both comfort and heal, and we, as teachers, fall short in preparing our trainees for their professional lives as physicians.

Yet effective methods for learning skills and attitudes related to humanistic care have been known, although only slowly adopted, since the 1980s.9 In this article, we describe how we and others9–11 incorporated these methods to create a multi-institutional intensive faculty development program; we also give an overview of experience with the program from its beginning in 2005–2006 through 2016–2017. The program marries individual professional development with learning by small-group community building to strengthen skills in promoting and teaching medical humanism.9–11 We defined medical humanism as the ability to form, maintain, and appropriately terminate relationships that are compassionate, respectful, and honest and that are sensitive to the autonomy, values, and cultural backgrounds of patients and their families.12–14 Our overall goal was to create a context in which humanistic professionalism would flourish and be internalized by faculty teachers who, in turn, could positively influence their colleagues, residents, and students.

Our points of departure in developing the program were the assumptions that (1) physicians’ professional identities continue to develop throughout adult life15–22; and (2) growth in medical humanism, often inhibited in residency training by unsavory aspects of the hidden curriculum—including isolation, overwork, and poor role models—could be restored and reinforced in the setting of a small-group learning community.23–26 We also reasoned that a truly robust intervention would have observable effects, and we evaluated our efforts both qualitatively and quantitatively. Some of us began to develop the curriculum in 1999,10,27 the program was fully established in 2005–2006, and as of 2017, it has been implemented successfully at 30 U.S. and Canadian medical schools, where 993 faculty, including some residents, have completed it. All of us who are authors of this article continue to be involved as program facilitators. Evidence from our multi-institutional studies suggests that our faculty development curriculum is effective, feasible, and generalizable, and that it represents an advance in medical education research and implementation, because most previous studies focused on individual institutions.9–11 Below, we describe our program and its potential as a model for others who seek to strengthen the humanistic side of medical education.

Program Organization, Participants, and Goals

Following the first offering at the five original schools in 2005–2006, additional schools applied for admission to subsequent cohorts of the program when grant funding became available. Eight additional schools were selected by a committee of the original facilitators in 2009, followed by nine new schools and one repeat school selected in 2013. Grants in 2014 and 2016 funded schools that had previously participated in the program. (See Supplemental Digital Appendix 1 at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A487 for a complete list of the schools, facilitators, and participants by year.)

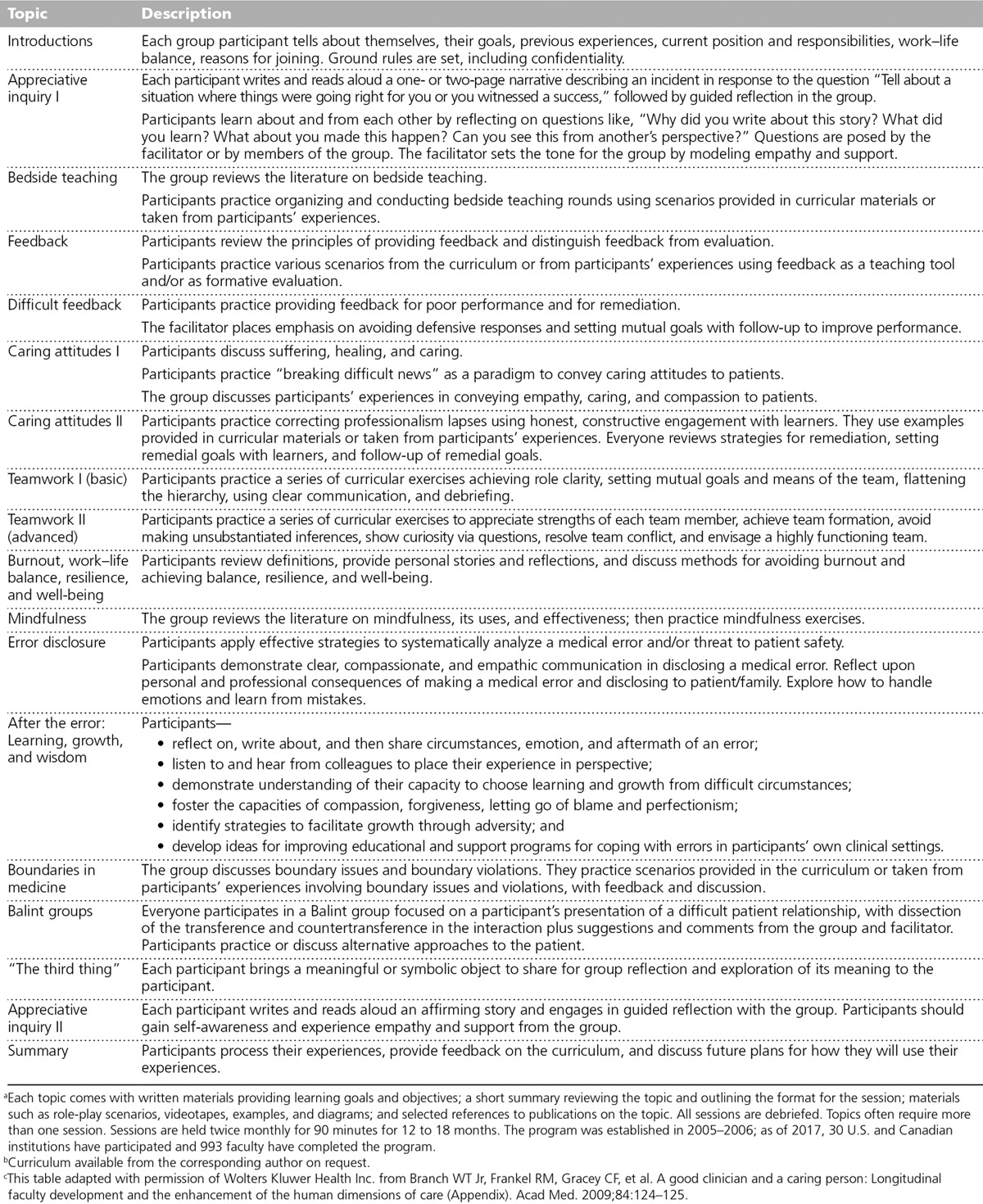

When selecting each institution’s local facilitator, the strength of the candidates as small-group teachers was considered an important qualification. Local facilitators at each institution selected 8 to 12 clinical faculty from all applicants who volunteered, were supported by their department chairs, and were respected clinical teachers willing to commit to the program for its duration. The curriculum (see Table 1) was provided by the principal investigator (W.T.B.) to each local facilitator. The small groups, composed of the faculty and facilitator, met twice monthly for 12 to 18 months. Grant-supported local facilitators were coached by the principal investigator on monthly conference calls while the program was under way. The cost of the program was the time spent by the facilitator (somewhat less than 10% of salary) and by the participating faculty at each school (small percentages of their salaries).

Table 1.

Detailed Descriptions of the Curricular Topics of the Faculty Development Program in Humanisma,b,c

Local facilitators who were grant supported and/or participating in one of the evaluations (24 schools) were required to follow the curriculum. Six other schools, chosen neither for grant funding nor participating in an evaluation, were allowed to use the curriculum if advised by the principal investigator. These “voluntary” schools had flexibility in how they organized the curriculum, but all schools offering the program met the requirement for being small-group based and longitudinal. Two voluntary schools used the curriculum for large-scale faculty development related to medical student education, and two other voluntary schools trained groups of residents in addition to faculty.

Educational Theory and Practice

From our previous experiences in designing faculty development programs, we knew that changes in skills and humanistic values would likely also require attention to professional growth and its relationship to stages of identity formation in young faculty. Kegan’s stages of identity formation provided us with an ideal conceptual framework to incorporate both humanistic attitudes and professional growth as aspects of professional identity formation.15,22

In our earliest qualitative studies of faculty who enrolled in the program, we found elements of Kegan’s stage 3, the Interpersonal, or Socialized, Mind—in which one becomes a team player, subordinates self-interest, aligns with role models, and seeks direction—and stage 4, the Institutional, or Self-authoring, Mind—in which one follows one’s own compass, enters into relationships, applies self-chosen internalized standards, controls desires and passions, is self-reflective, and learns to lead and drive agendas. As participants completed the program, we looked for evidence of progression, including some participants approaching Kegan’s stage 5, the Self-transforming Mind, in which one is a leader who is value originating and history making, identifies problems, can entertain multiple perspectives, and is interdependent.15,22 Each stage involves both social and personal development as the developing clinician–educator engages in a community of practice and internalizes that community’s professional and moral values. Thus, the overarching goal that our program adopted was for each participating faculty member to progress toward the higher stages of professional identity formation and development. We chose this goal because we believed that combining individual professional development with learning by small-group community building would strengthen the skills needed to promote and teach medical humanism.

Our groups employed longitudinal reflective and experiential learning that allowed for supportive group processes to emerge and be sustained over time.9–11 Learning of this sort can create a powerful synergy for reflection on actions that often lead to transformations in attitudes, skills, and behaviors and their incorporation into professional identity.9

The teaching methods employed were narrative reflective writing exercises, personal awareness explorations, experiential skills-building exercises incorporating feedback and coaching, short didactic presentations, and case discussions. The small groups at each school began with introductions, followed by reflective writing exercises, where narratives were read aloud and discussed. A typical exercise might involve responding to the prompt, “Please take 5 minutes to write about a time when you were in training and were treated humanistically by a faculty teacher.” Writing exercises were based on appreciative inquiry, an organizational culture-change strategy that focuses on what is going well and gives life to an organization rather than focusing on what’s wrong with an organization and how to fix it.28 We chose this positive approach for narrative reflection to share the strengths of each group member with others and build a sense of community around positive themes on which the curriculum would later elaborate. Narrative reflective writing triggers memories and meanings that lead to self-discovery or, conversely, enhances perspectives on the actions of others.29–35 Group support and validation aid in processing the experiences and the learning brought forth by reflective writing.9

Following the narrative writing sessions, a series of experiential skills-building exercises were developed to give participants opportunities to practice teaching and role modeling humanism in a safe, supportive, and reflective atmosphere. This learning environment encouraged individuals to take risks and move beyond their previous levels of skill, comfort, and confidence, and established a norm in which receiving and giving coaching and feedback for improvement, rather than evaluating performance, were encouraged and desired. Engagement in this experiential learning tied meaning and self-identity to skilled communication and practical moral actions related to teaching and role modeling medical humanism in clinical settings.9 The synergistic nature of reflective and experiential learning, experienced together over time, solidified change and strengthened participants’ commitments to humanistic values.9 This approach to learning has been shown to promote identity formation and growth.29,35

Curriculum

Table 1 lists the current curricular content with detailed descriptions of the sessions devoted to each topic. Some topics required two or more sessions to complete. After we had offered the program at the five original schools, new facilitators suggested and added sessions on physician resilience and well-being, mindfulness, error disclosure, boundary issues, and teamwork without fundamentally altering the core curriculum and its design (see more about curricular design in the first footnote of Table 1). The new sessions were added to enhance humanistic teaching by encouraging participants to be reflective and mindful and to find satisfaction in their work.36,37 (The curriculum is available from the corresponding author on request.)

Evaluations

Description of the evaluations

The main evaluation goal was to learn medical students’ and residents’ assessments of participating faculty as humanistic teachers and role models. Participating faculty and matched controls had served as these learners’ teachers for two or more weeks on a clinical service. Because at the time we could find no measurement instruments in this domain, we created and validated a 10-item questionnaire, the Humanistic Teaching Practices Effectiveness Questionnaire,38 which was completed by learners who did not know whether their teacher was a participant or a control. The 10-item questionnaire rates faculty as humanistic teachers and role models as well as rating their humanistic behaviors.10,11

We initially performed two prospective cohort studies. Participants in the program were compared by their learners against one or more control faculty members matched for age, gender, specialty, and teaching skills as rated on standard evaluations. The first, pilot study, carried out at the 5 original institutions, compared 34 participants with 47 controls; 300 learners made the assessments.10 The second confirmatory study, done at 8 different institutions, compared 52 participants with 94 controls; 542 learners made the assessments.11 Program participants who dropped out (25% and 5%, respectively) were not included. Both studies showed overall statistically significant superiority for the program participants versus the controls (P < .05). As secondary outcomes, we examined overall responses to each of the 10 items, and the outcomes of the study at each of the institutions. Overall responses were statistically significant in a positive direction for the participants on the majority of the 10 items.10,11 Although our two studies were not powered to reach statistical significance for single institutions, participants were significantly superior to controls at 7 of 13 institutions, and at 11 of 13 institutions participants were favored over controls.10,11

A tertiary outcome was longitudinal engagement of the participants in the curriculum. After the pilot study at 5 schools, participants at 17 grant-supported schools had dropout rates of 5% to 10%, with 80% or better attendance at all sessions. Attendance fell below this standard at 1 school, attributed to uneven facilitation. We interpret these generally high rates of attendance and low dropout rates as indicators of engagement, feasibility, perceived benefit, and need by the participating faculty.

Qualitative studies have provided a more textured understanding of the participants’ experiences and offered a meaning-based method for understanding and judging the success of the program from the “inside out.” Descriptions of faculty members’ actions, attitudes, and values embedded in their narratives were used as indicators of professional identity formation.15 Our initial qualitative study uncovered detailed insights into the educational processes at work using narrative reflection. For example, we observed statements of group support and group norms, suggesting that the group itself served as a type of “sense-making” forum where participating faculty could decode the effects of the hidden curriculum on their professional identity formation.39 Group members adopted norms in the beginning sessions focused on having empathy for patients and teaching empathy to learners. Later, as they advanced in their careers and assumed leadership roles, their narratives and reflective discussions addressed helping one another maintain resilience and integrity in the face of stress and competing values.39

A second qualitative study employed narrative analysis as a framework40 and focused on a particular type of story that was highly humanistic and also transformed and humanized the narrator in a meaningful way in the process.40 We hypothesized that, much like folk tales, the function of these stories was to memorialize high-point experiences that anchor the tellers to their own and their community’s humanistic values.41,42 We called these specially marked stories formation narratives because they followed a sequence of transformative learning that parallels the stages of professional identity formation. Of note, we found three times the number of formation narratives at the end of our program than at its beginning,40 perhaps supporting our hypothesis that participants were progressing as they described and reflectively discussed with their group their experiences of key moments in professional formation around humanism.

Summary of the evaluations

On the quantitative side, our outcome data, based on a validated learner-completed measure, consistently favored the participants over the controls. Some or even all of our results could reflect a selection bias if the individuals chosen to participate in this program had been more humanistic than the controls at baseline. We believe this is unlikely to have accounted for all of the difference because the participants were similar to the controls in standard teaching skills and demographic variables.

On the qualitative side, changes over time in narrative content suggest a progression of participants from lower to higher stages of professional development using Kegan’s framework. More specifically, many program completers progressed from stages 3 and 4 toward stage 5 in terms of being value originating and history making after having completed the program.15,40 The participants in these studies described the “lived experiences” that led them to internalize humanistic values,39,40 and did so by sharing and learning in their community.39 Combining the quantitative and qualitative assessments of the program leads to the reasonable conclusion that our multi-institutional longitudinal faculty development program facilitated the professional development in humanism of its participants.

Expansion and Continuation

We have now successfully offered and completed the physicians’ program to grant-supported cohorts of 5 to 10 schools four times since 2005, with a fifth interprofessional cohort of eight previously funded schools now under way. The total number of schools completing the program one or more times to date includes 22 grant-supported schools and 8 additional schools that were not grant supported, which use the program with our advice but without supervision unless participating in an evaluation. Initially, we had studied our program as a one-time offering, which would provide a school with highly developed humanistic teachers whose influence would spread among their colleagues and learners and would positively influence the hidden curriculum. Since 1 school, which was in the second cohort of 8 schools, began offering the program to new groups of faculty on an annual basis and has now done so eight times, we recognized that schools would have various needs, and many, if not most, would benefit from developing larger numbers of humanistic teachers. Thus, we began actively encouraging schools in our most recent cohorts to offer the program more than once, depending on their needs.

Schools, their facilitators, and numbers of faculty completing the program each year are listed in Supplemental Digital Appendix 1 (see http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A487). All eight schools in our newly initiated interprofessional cohort will offer the program at least twice.43 Follow-up with local facilitators suggested that schools choosing not to continue did so for lack of sufficient funds or because a higher priority was given to other faculty development programs, some of which incorporated elements of our program.

Reflection on Future Plans

We think that our humanistic faculty development program is an important step toward creating the desired learning climate in medical education because our program enables young faculty to progress toward realizing their full potential as teachers and leaders. Experience with our program demonstrates the feasibility and acceptability to faculty of providing this highly intensive, longitudinal type of faculty development. But we view training the faculty as an initial step in setting the stage for humanistic educational programs that can transform the learning climate within medical schools and teaching hospitals. Based on the success of our program and similarly designed ones,9–11,44–47 we believe that the same humanistic educational approaches will also succeed if applied widely on a larger scale for medical students and residents. Medical educators at an expanding number of schools have previously or are now successfully applying longitudinal small-group teaching within learning communities.44–47

As we reflect, we envisage many outcomes remaining to study. Our unpublished follow-up of program completers after one year shows, as we had hoped, much more involvement in creating and leading educational programs by our graduates than by the controls. We plan to study the longer-term accomplishments and career trajectories of the large numbers of graduates of our program as those data become available. We also desire to study humanistic behaviors in learners exposed to our graduates; however, this has proved difficult. A small unpublished study of humanistic attitudes on teams of learners who had been exposed to our program completers failed to reach statistical significance, we think, because of numerous crossovers and additional influences on the study’s participants that diluted the sensitivity of our instrument. Others have used surveys to study long-term outcomes of their single-institution humanistic programs without uniformly reporting significant results, perhaps for the same reasons.48,49 These experiences denote the difficulties of broad outcomes studies of learners exposed to humanistic programs but influenced by many other factors. A more promising avenue for research may be the accumulation of results from small randomized trials focusing on one or a few well-defined components of medical humanism, analogous to successful trials that showed teaching communication skills to be effective.50–53

We also foresee applying our experience in multi-institutional research to medical student and residency education. If funding and institutional cooperation in curricular design were available, we could focus on large-scale studies of important specific measurable educational outcomes, such as the impact of training using our methods on giving difficult news, patient-centered shared decision making, and motivational interviewing; mastery in these areas provides paradigmatic humanistic skills and attitudes widely applicable to clinical practice. Studies using blinded skills ratings of standardized patient interviews and validated questionnaires plus patient outcomes, including patient satisfaction, are timely and feasible, given current knowledge of educational theory and praxis. In the meantime, qualitative studies have much to offer, and we are currently exploring the application of qualitative methods to issues related to teamwork, collaboration, leadership, well-being, resilience, and organizational culture in interprofessional groups completing our program.43,54

We suggest that the strong growth potential in the development cycles of young faculty in the health professions should be matched by institutional commitments to provide the necessary tools and learning climate that can assist those faculty in reaching their full potential. We believe that a core group of faculty trained in programs such as ours could lead institutional initiatives and bring about positive change in humanistic professional development at all levels of medical education. Given the challenges of today’s rapidly changing practice and teaching environments, finding creative and effective ways of reaching this goal is more important than ever.

Acknowledgments:

In Table 1, the activities listed in the description of “After the error: learning, growth, and wisdom,” were developed by Margaret Plews-Ogan, MD, Justine E. Owens, PhD, and Natalie B. May, PhD.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Funding/Support: The authors wish to thank the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations, the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, and the Arnold P. Gold Foundation for generous support.

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: Reported as not applicable. No original results are reported; all research cited was approved or exempted by the institutional review boards of the participating institutions.

Previous presentations: Research findings cited in this article were presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM) national meeting, Los Angeles, California, April 26–29, 2007; International Conference on Communication in Healthcare (ICCH), Miami, Florida, October 4–8, 2009; ICCH, Chicago, Illinois, October 16–19, 2011; SGIM national meeting, Phoenix, Arizona, May 4–7, 2011; and ICCH, New Orleans, Louisiana, October 25–28, 2015.

Supplemental digital content for this article is available at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A487.

References

- 1.Rogers WR, Barnard D. Nourishing the Humanistic in Medicine: Interactions With the Social Sciences. 1979Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Improving Medical Education: Enhancing the Social and Behavioral Science Content of Medical School Curricula. 2004Washington, DC: National Academy Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ABIM Foundation; ACP-ASIM Foundation; European Federation of Internal Medicine. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: A physician charter. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:243–246.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Functions and Structure of a Medical School: Standards for Accreditation of Medical Education Programs Leading to the MD Degree. 2003Washington, DC: Liaison Committee on Medical Education. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Irby DM, Cooke M, O’Brien BC. Calls for reform of medical education by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching: 1910 and 2010. Acad Med. 2010;85:220–227.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coulehan J, Williams PC. Vanquishing virtue: The impact of medical education. Acad Med. 2001;76:598–605.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hojat M, Vergare MJ, Maxwell K, et al. The devil is in the third year: A longitudinal study of erosion of empathy in medical school. Acad Med. 2009;84:1182–1191.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martimianakis MA, Michalec B, Lam J, Cartmill C, Taylor JS, Hafferty FW. Humanism, the hidden curriculum, and educational reform: A scoping review and thematic analysis. Acad Med. 2015;90(11 suppl):S5–S13.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Branch WT. Teaching professional and humanistic values: Suggestion for a practical and theoretical model. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98:162–167.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Branch WT, Jr, Frankel R, Gracey CF, et al. A good clinician and a caring person: Longitudinal faculty development and the enhancement of the human dimensions of care. Acad Med. 2009;84:117–125.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Branch WT, Jr, Chou CL, Farber NJ, et al. Faculty development to enhance humanistic teaching and role modeling: A collaborative study at eight institutions. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:1250–1255.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arnold P Gold Foundation. The Arnold P. Gold Foundation. http://www.gold-foundation.org. Accessed September 18, 2017.

- 13.Weissmann PF, Branch WT, Gracey CF, Haidet P, Frankel RM. Role modeling humanistic behavior: Learning bedside manner from the experts. Acad Med. 2006;81:661–667.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chou CM, Kellom K, Shea JA. Attitudes and habits of highly humanistic physicians. Acad Med. 2014;89:1252–1258.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kegan R. The Evolving Self: Problem and Process in Human Development. 1982Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forsythe GB. Identity development in professional education. Acad Med. 2005;80(10 suppl):S112–S117.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rabow MW, Remen RN, Parmelee DX, Inui TS. Professional formation: Extending medicine’s lineage of service into the next century. Acad Med. 2010;85:310–317.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldie J. The formation of professional identity in medical students: Considerations for educators. Med Teach. 2012;34:e641–e648.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jarvis-Selinger S, Pratt DD, Regehr G. Competency is not enough: Integrating identity formation into the medical education discourse. Acad Med. 2012;87:1185–1190.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holden M, Buck E, Clark M, Szauter K, Trumble J. Professional identity formation in medical education: The convergence of multiple domains. HEC Forum. 2012;24:245–255.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Snell L, Steinert Y. Reframing medical education to support professional identity formation. Acad Med. 2014;89:1446–1451.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Snell L, Steinert Y. A schematic representation of the professional identity formation and socialization of medical students and residents: A guide for medical educators. Acad Med. 2015;90:718–725.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hafler JP, Ownby AR, Thompson BM, et al. Decoding the learning environment of medical education: A hidden curriculum perspective for faculty development. Acad Med. 2011;86:440–444.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hundert EM, Hafferty F, Christakis D. Characteristics of the informal curriculum and trainees’ ethical choices. Acad Med. 1996;71:624–642.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hafferty FW, Gaufberg EH, O’Donnell JF. The role of the hidden curriculum in “on doctoring” courses. AMA J Ethics. 2015;17:130–139.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaufberg EH, Batalden M, Sands R, Bell SK. The hidden curriculum: What can we learn from third-year medical student narrative reflections? Acad Med. 2010;85:1709–1716.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Branch WT, Jr, Kern D, Haidet P, et al. The patient–physician relationship. Teaching the human dimensions of care in clinical settings. JAMA. 2001;286:1067–1074.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cooperrider D, Whitney D. Appreciative Inquiry: A Positive Revolution in Change. 2005San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brookfield S. Mezirow J. Using critical incidents to explore learners’ assumptions. In: Fostering Critical Reflection in Adulthood: A Guide to Transformative and Emancipatory Learning. 1990:San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 177–193.. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sprinthall NA. Rest JR. Counseling and social role taking: Promoting moral and ego development. In: Moral Development in the Professions: Psychology and Applied Ethics. 1994:Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 55–100.. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Branch WT., Jr Use of critical incident reports in medical education. A perspective. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:1063–1067.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DasGupta S, Charon R. Personal illness narratives: Using reflective writing to teach empathy. Acad Med. 2004;79:351–356.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bolton G. Reflective Practice: Writing and Professional Development. 2001:London, UK: Paul Chapman Publishing/Sage; 117–118.. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Charon R. Narrative and medicine. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:862–864.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mezirow J. Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning. 1991San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zwack J, Schweitzer J. If every fifth physician is affected by burnout, what about the other four? Resilience strategies of experienced physicians. Acad Med. 2013;88:382–389.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Epstein RM, Krasner MS. Physician resilience: What it means, why it matters, and how to promote it. Acad Med. 2013;88:301–303.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Logio LS, Monahan P, Stump TE, Branch WT, Jr, Frankel RM, Inui TS. Exploring the psychometric properties of the humanistic teaching practices effectiveness questionnaire, an instrument to measure the humanistic qualities of medical teachers. Acad Med. 2011;86:1019–1025.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Higgins S, Bernstein L, Manning K, et al. Through the looking glass: How reflective learning influences the development of young faculty members. Teach Learn Med. 2011;23:238–243.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Branch WT, Jr, Frankel R. Not all stories of professional identity formation are equal: An analysis of formation narratives of highly humanistic physicians. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99:1394–1399.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Polanyi L. Telling the American Story: A Structural and Cultural Analysis of Conversational Storytelling. 1979Norwood, NJ: Albex. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lord AB. The Singer of Tales. 1960Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Manning K, Abraham C, Kim JS, et al. Preparing the ground for interprofessional education: Getting to know each other. J Humanit Rehabil. 2016;June. https://scholarblogs.emory.edu/journalofhumanitiesinrehabilitation/2016/06/20/preparing-the-ground-for-interprofessional-education-getting-to-know-each-other/. Accessed September 18, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Branch WT, Arky RA, Woo B, Stoeckle JD, Levy DB, Taylor WC. Teaching medicine as a human experience: A patient–doctor relationship course for faculty and first-year medical students. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:482–489.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Branch WT, Pels RJ, Harper G, et al. A new educational approach for supporting the professional development of third-year medical students. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:691–694.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gaufberg E, Shtasel D, Hirsh D, Ogur B, Bor D. The Harvard Medical School Cambridge Integrated Clerkship: Challenges of longitudinal integrated training. Clin Teach. 2008;5:78–82.. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith SD, Dunham L, Dekhtyar M, et al. Medical student perceptions of the learning environment: Learning communities are associated with a more positive learning environment in a multi-institutional medical school study. Acad Med. 2016;91:1263–1269.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peters AS, Greenberger-Rosovsky R, Crowder C, Block SD, Moore GT. Long-term outcomes of the New Pathway Program at Harvard Medical School: A randomized controlled trial. Acad Med. 2000;75:470–479.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Knight AM, Cole KA, Kern DE, Barker LR, Kolodner K, Wright SM. Long-term follow-up of a longitudinal faculty development program in teaching skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:721–725.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fallowfield L, Jenkins V, Farewell V, Saul J, Duffy A, Eves R. Efficacy of a Cancer Research UK communication skills training model for oncologists: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:650–656.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maguire P, Booth K, Elliott C, Jones B. Helping health professionals involved in cancer care acquire key interviewing skills—The impact of workshops. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:1486–1489.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith S, Hanson JL, Tewksbury LR, et al. Teaching patient communication skills to medical students: A review of randomized controlled trials. Eval Health Prof. 2007;30:3–21.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith RC, Lyles JS, Mettler J, et al. The effectiveness of intensive training for residents in interviewing. A randomized, controlled study. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:118–126.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Montgomery A, Panagopoulou E, Kehoe I, Valkanos E. Connecting organisational culture and quality of care in the hospital: Is job burnout the missing link? J Health Organ Manag. 2011;25:108–123.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]